Abstract

Objective:

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) appears to have a role in lipid metabolism. Recently, we showed that GIP in combination with hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia increases triglyceride uptake in abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue in lean humans. It has been suggested that increased GIP secretion in obesity will promote lipid deposition in adipose tissue. In light of the current attempts to employ GIP antagonists in the treatment and prevention of human obesity, the present experiments were performed in order to elucidate whether the adipose tissue lipid metabolism would be enhanced or blunted during a GIP, hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic (HI–HG) clamp in obese subjects with either normal glucose tolerance (NGT) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT).

Design:

Sixteen obese (BMI>30 kg m−2) subjects were divided into two groups, based on their plasma glucose response to an oral glucose challenge: (i) NGT and (ii) IGT. Abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue lipid metabolism was studied by conducting measurements of arteriovenous concentrations of metabolites and regional adipose tissue blood flow (ATBF) during GIP (1.5 pmol kg−1 min−1) in combination with a HI–HG clamp.

Results:

In both groups, ATBF responses were significantly lower than what we have found previously in healthy, lean subjects (P<0.0001). The flow response was significantly lower in the IGT group than in the NGT group (P=0.03). It was not possible to show any increase in the lipid deposition in adipose tissue under the applied experimental conditions and likewise the circulating triglyceride (TAG) concentrations remained constant.

Conclusion:

The applied GIP, HI–HG clamp did not induce any changes in TAG uptake in adipose tissue in obese subjects. This may be due to a blunted increase in ATBF. These experiments therefore suggest that GIP does not have a major role in postprandial lipid metabolism in obese subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) is a 42-amino-acid polypeptide produced by enteroendocrine K-cells in response to oral ingestion of glucose or fat.1, 2, 3 In addition to its insulinotropic effect, GIP may have other physiological effects. It has been suggested to have a role in the postprandial lipid metabolism via promotion of the deposition of circulating triglycerides (TAGs) in adipose tissue.4, 5 In addition, it has been suggested that increased GIP secretion in obesity will promote further lipid deposition in adipose tissue and thus aggravate the above state.6 Furthermore, antagonizing GIP action has been proposed as a therapeutic strategy for obesity based on the observations in GIP receptor knockout mice and in mice with high-fat-induced obesity treated with a GIP antagonist.7, 8 No human in vivo data are available demonstrating any effect of such GIP antagonists on body weight.

In a recent study, we assessed the effects of GIP on abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue in vivo in healthy, lean, male subjects.4 We found that GIP per se does not have effects on human subcutaneous adipose tissue in lean healthy subjects. However, when combined with hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia, adipose tissue hydrolysis of TAG, glucose and fatty acid uptake and fatty acid re-esterification increased. These findings thus suggest that GIP in combination with insulin has a role in the postprandial lipid metabolism in lean subjects. These metabolic effects were accompanied by a significant vasodilatation in adipose tissue. However, neither GIP alone nor insulin and hyperglycemia had any vascular effects in adipose tissue, but when GIP was infused in combination with insulin and hyperglycemia a pronounced vasodilatation in adipose tissue was induced in these experiments. It has been shown that the postprandial vasodilatation taking place in adipose tissue has a role in the hydrolysis of circulating TAG by enhancing the substrate supply to the capillary-bound lipoprotein lipase.9 Therefore, these effects seem beneficial, as efficient fat deposition in the subcutaneous depots protects other tissues from prolonged exposure to high levels of lipids postprandially.

On the other hand, it has been shown that the postprandial vasodilatation in adipose tissue is blunted in obese subjects.10 Therefore, in this perspective, postprandial lipid deposition in adipose tissue is rendered more difficult in obese subjects. As the concentrations of active GIP in lean and obese subjects are comparable postprandially,11 we hypothesize that adipose tissue may be GIP and insulin resistant with respect to postprandial lipid metabolism in obese subjects. Therefore, the aim of the present experiments was to study the effects of a GIP, hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic (HI–HG) clamp on abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue metabolism in obese subjects and to investigate whether the degree of insulin resistance has a role in the GIP metabolic effects in adipose tissue in obese subjects.

Materials and methods

Subjects

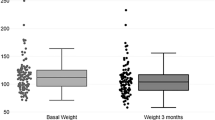

We studied 16 obese (BMI>30 kg m−2) males. Based on their plasma glucose response to an oral glucose challenge, subjects were classified as having normal glucose tolerance (NGT; that is, fasting glucose<6.1 mM and 2-h glucose<7.8 mM, n=8) and impaired glucose tolerance (that is, fasting glucose<7 mM and 2-h glucose between 7.8 and 11.1 mM, n=8) according to the American Diabetes Association criteria.12 Anthropometric characteristics of the two groups appear in Table 1 and did not differ significantly. Percentage of fat (% fat mass) was measured using a total-body dual-energy X-ray (DXA) scan. A standard examination includes total body and regional measurements of the trunk, arms and legs, and the amount of fat is automatically generated in the total-body dual-energy X-ray body composition report. The subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue thickness was measured on the total-body dual-energy X-ray scan. This was done manually at the horizontal level with the largest subcutaneous thickness between the upper iliac crest and the umbilicus. The delineation of the subcutaneous tissue and the underlying abdominal muscle was defined as a clear shift in the gray scale on the scan.

All subjects signed a consent declaration after having received written and oral information about the study protocol. The scientific ethics committee in Copenhagen Municipality approved the protocol and the study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration II.

Experimental design

Each subject underwent a hyperinsulinemic (7 mU m−2 min−1) and a hyperglycemic (7 mM) clamp keeping plasma glucose and insulin concentrations to the levels seen after ingestion of a carbohydrate-rich meal, with continuous infusion of GIP (1.5 pmol kg−1 min−1) during 180 min.

Protocol

The subjects were instructed to abstain from drinking alcohol during the 48 h before the study. On the day of the experiment, subjects arrived at the department at 0900 hours, having used non-strenuous transportation and after having fasted for at least 12 h. The investigations were performed with the subjects in supine position in a room kept at 24 °C. After catheterizations as described below, baseline measurements (time=30, 15 and 0 min) were commenced. Thereafter, a continuous infusion of GIP in combination with a HI–HG clamp was initiated at time=0.

Catheterizations

One catheter (BD Venflon, PRO, Becton Dickinson, Singapore) was inserted into the antecubital vein for the infusion of GIP, glucose and insulin. The subjects were then catheterized in a subcutaneous vein on the anterior abdominal wall and in a radial artery.

A vein draining the subcutaneous, abdominal adipose tissue on the anterior abdominal wall was catheterized antegradely as previously described13 during ultrasound/color-Doppler imaging of the vein. A 22-g 10-cm polyurethane catheter (Arrow International, Reading, PA, USA) was inserted using the Seldinger technique. The tip of the catheter was positioned above the inguinal ligament in order to minimize the risk of withdrawing blood from the femoral vein. After insertion, the catheter was kept patent throughout the experiment by continuous infusion of saline at a rate of 40 ml h−1. Another catheter was inserted percutaneously into the radial artery of the nondominant arm under local analgesia (1 ml 1% lidocaine) with an Artflon (Becton Dickinson, Temse, Belgium). The catheter was kept patent with regular flushing with saline.

GIP infusion and HI–HG clamp

GIP

Synthetic human GIP (1–42) (Polypeptide Laboratories, Wolfenbüttel, Germany) was dissolved in sterilized water containing 2% human serum albumin (human albumin, CSL Behring, Marburg, Germany) and subjected to sterile filtration. Vial content was tested for sterility and bacterial endotoxins (Ph. Eur. 2.6.14, Method C: turbidimetric kinetic method). The peptide was demonstrated to be >97% pure and identical to the natural human peptide by high-performance liquid chromatography, mass and sequence analysis.

HI–HG clamp

Insulin (Actrapid Human; Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark) was infused at a continuous rate of 7 mU m−2 min−1, which resulted in physiological postprandial plasma insulin levels. Variable glucose infusion was used to clamp blood glucose at hyperglycemia corresponding to the levels found after a mixed meal (6.5–7.5 mM) for the duration of the experiments.

Measurements

Adipose tissue blood flow

Adipose tissue blood flow measurements were performed continuously for the duration of the experiment by recording washout of 133Xenon, which was injected in gaseous form in the adipose tissue. This technique has previously been validated in our laboratory.13 About 1 MBq gaseous 133Xenon (The Hevesy Laboratory, Risoe National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark) mixed in ∼ 0.1 ml of atmospheric air was injected into the para-umbilical area of the subcutaneous adipose tissue. The washout rate of 133Xenon was measured by a scintillation-counting device (Mediscint, Oakfield Instruments, Oxford, UK).

Blood samples and analysis

Blood samples were drawn at time points of -30, -15 and 0 min, and thereafter every 30 min until discontinuation of the infusion. Plasma glucose concentrations were measured every 5–10 min for clamp adjustments.

Blood samples were drawn simultaneously from the two catheters for measurements of TAG, glycerol, free fatty acids (FFA) and glucose. In addition, blood was collected from the artery for measurements of GIP and insulin.

Blood samples were collected into ice-chilled tubes (Vacuetta, Greiner Labortechnic, Kremsmünster, Austria). Tubes for intact GIP contained EDTA and a specific DPP-4 inhibitor (valine-pyrrolidide; 0.1 μmoll−1, final concentration; a gift from Drs RD Carr and LB Christiansen, Novo Nordisk A/S Bagsværd, Denmark), and the tube for insulin contained heparin. Tubes for glucose, TAG, FFA and glycerol contained EDTA. All samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 5000 g at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Intact GIP was measured as described in Deacon et al.14 The assay is specific for the intact N-terminus of GIP, the presence of which is required for biological activity of the peptide.

Plasma glucose (Glucose/HK, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), TAG (Triglyceride GPO-PAP, Roche Diagnostics), FFA (NEFA C kit, Wako Chemicals, Neuss, Germany) and glycerol (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) were measured by enzymatic methods modified to run on a Hitachi 912 automatic analyzer (Boehringer).

Plasma insulin and C-peptide concentrations were measured by ELISA-immunoassay (DRG Instruments, GmbH, Germany).

Plasma glucose was measured bedside during the clamp experiments using the Radiometer ABL 725 blood gas analyzer (Radiometer Corp., Copenhagen, Denmark).

Calculations and statistical analysis

The adipose tissue blood flow was calculated from the mean washout rate constant determined in 30-min periods corresponding to the time points when blood samples were drawn. ATBF was then calculated according to the equation ATBF=−k × λ × 100. A tissue/blood partition coefficient (λ) for Xenon of 10 ml g−1 was used.15, 16, 17

Subcutaneous adipose tissue metabolic net fluxes were calculated by multiplication of the arterial–venous or venous–arterial concentration differences of the metabolite and the appropriate flow value (whole blood for calculation of glycerol and glucose fluxes18 and plasma flow for calculation of fatty acid and TAG fluxes).

All results are presented as mean±s.e.m. Areas under the curve (AUC) were calculated using the trapezoidal rule and are presented as the incremental values (baseline levels subtracted). The significance in changes in ATBF, arterial hormone and metabolite concentrations with time between the groups was tested using two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures. Significant differences in AUC-ATBF and metabolite fluxes within the group were evaluated by paired t test. Differences in metabolite fluxes between the groups were evaluated by two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures. A significance level of 0.05 was chosen.

The Statistical Analysis Software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical calculations.

Results

Arterial hormone and metabolite concentrations

Intact GIP concentrations reached physiological postprandial levels after approximately 30 min at 39.5±1.2 pM in subjects with NGT and 36.7±4.3 pM in subjects with IGT (P=NS, Figure 1a).

Insulin concentrations increased rapidly during the first 30 min from 92±4 and 120±1 pM, respectively (P<0.01), at baseline to a mean plateau level of 357±17 and 381±13 pM, respectively (P=NS, Figure 1b). C-peptide concentrations increased from 738±6.5 and 910±19.4 pM, respectively, in the NGT and IGT groups (P=0.02), at baseline to a mean plateau level of 1678±50 and 1731±26 pM, respectively (P=NS).

In both groups, glucose levels increased from 5.30±0.03 and 5.70±0.02 mM, respectively, at baseline toward target levels during the first 60 min and remained virtually constant and similar during 60–180 min (7.0±0.1 mM in subjects with NGT and 7.3±0.06 mM in subjects with IGT, P=NS, Figure 1c).

There was a significant difference between the total amounts of glucose infused during the experiment between the two groups (57.4±3.3 g in subjects with NGT and 41.6±5.2 g in subjects with IGT, P<0.05). During steady-state conditions 90–180 min after the commencement of the clamp, the glucose infusion rates were significantly different in the two groups (3.3±0.3 mg kg−1 min−1 in subjects with NGT and 2.4±0.2 mg kg−1 min−1 in subjects with IGT, P=0.03).

The arterial concentrations of the metabolites are given in Figure 2. In both groups, the TAG concentrations were similar and virtually constant throughout the study (Figure 2a). Baseline FFA concentrations were significantly lower in the NGT group compared with the IGT group (P<0.01, Figure 2b). There was a tendency of lower baseline glycerol concentration in the NGT group when compared with the IGT group (P=0.09, Figure 2c). FFA and glycerol concentrations decreased significantly within the first 90 min of the clamp and remained decreased during the rest of the experiment in both groups. The FFA and glycerol concentrations were significantly higher in the IGT group compared with the NGT group in the period 90–180 min after commencement of the clamp (P<0.001 and P<0.001, Figures 2b and c, respectively).

Adipose tissue blood flow

At baseline, ATBF was similar in the two groups, ∼2.5 ml per 100 g per min on average (Table 1). In the IGT group, ATBF remained virtually unchanged throughout the study (Figure 3a). In the NGT group, ATBF increased transiently, reaching a maximum of about twice the baseline level at 60 min (P=0.03, Figure 3a) and then began to decrease to reach the basal level again after 150 min. The integrated net increase in blood flow in the period 30–180 min amounted to 267±97 ml per 100 g per 150 min in the NGT group and to 127±32 ml per 100 g per 150 min in the IGT group (P=0.02, Figure 3b). In the steady period 90–180 min, the integrated ATBF response was 123±29 ml per 100 g per 90 min in the NGT group and 88±24 ml per 100 g per 90 min in the IGT group (P<0.01, Figure 3c).

Abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue blood flow during the GIP and HI–HG clamp experiment in NGT (solid square) and IGT (open square) groups (a). *P<0.05, reflecting the differences with respect to baseline. The integrated net increase in blood flow in the period 30–180 min (b) and in the steady period 90–180 min after commencement of infusions (c). Data are mean±s.e.m.

Net fluxes of TAG, FFA, glycerol and glucose

Figure 4 shows net fluxes of TAG, FFA, glycerol and glucose in adipose tissue under baseline and during steady-state conditions 90–180 min after the commencement of the clamp. In both groups, it was not possible to demonstrate any significant TAG uptake in adipose tissue, neither in the baseline period nor during the clamp period, probably due to the limited number of experimental subjects in relation to the sensitivity of the TAG analysis (Figures 4a and b). FFA and glycerol output decreased significantly in both groups (P<0.001, Figures 4c and d). FFA output was significantly lower in the subjects with NGT compared with subjects with IGT (P=0.01). In neither group was there a significant change in glucose uptake (Figures 4g and h); however, there was a tendency of increased glucose uptake in the NGT group (P=0.1, Figure 4g). FFA/glycerol ratio was decreased in both groups (P<0.0001 and P<0.001, Figures 4i and j, respectively) during the clamp, however, to a lesser extent in the IGT group, and was significantly higher 90–180 min after the commencement of the clamp compared with the NGT group (P<0.001).

Average net fluxes of TAG, FFA, glycerol and glucose in abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue during the pre-infusion baseline period and in the steady-state period from 90 to 180 min after commencement of infusions in the NGT group (a, c, e, g) and in the IGT group (b, d, f, h). Average adipose tissue FFA/glycerol output ratio during the pre-infusion baseline period and in the steady-state period from 90 to 180 min in the NGT group (i) and in the IGT group (j). Data are mean±s.e.m.

Discussion

The major finding in the present study is that GIP in combination with a HI–HG clamp did not result in lipid deposition in adipose tissue in obese subjects. This is in contrast to what we have previously demonstrated in normal-weight, healthy subjects under similar experimental conditions. A small but significant vasodilatation took place in adipose tissue in the present subjects with normal glucose tolerance, whereas it was nearly absent in the subjects with decreased glucose tolerance. The vasodilatation was only transient in the present study as compared to the prolonged and sustained vasodilatation we found in our previous study.4 In that study we found that ATBF increased about fourfolds during GIP and insulin infusion. In contrast we found a twofold increase in the present subjects with NGT and no increase in the subjects with IGT.

Adipose tissue is highly regulated by the nervous system, by the rate of blood flow through the tissue, and by a complex mixture of hormones and fats that are delivered with the blood.9 The adipose tissue is extremely dynamic and regulated on a minute-to-minute basis, and this can only be studied in the living body, which is one of the major strengths of this study. Using catheters, blood samples were taken from the arteries leading to the abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue and from the veins draining the tissue. Another strength of this study is that we compare two groups of overweight subjects who are matched with respect to upper-body fat distribution. The only significant difference between the groups is their glucose tolerance. It can be argued that a weakness of this study is the lack of a lean, healthy control group. However, we find that our previous study in such subjects justifies the omission of a control group in the present study. It could also be argued that the effect of hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia per se should have been studied in the present subjects. However, as it is well established that insulin per se does not have any vascular effects in adipose tissue, as we and others previously have demonstrated,4, 19, 20 we find that such an experiment would not add significance to the present findings.

In our previous study, a significant increase in TAG hydrolysis, glucose uptake and FFA re-esterification took place during the GIP and insulin clamp.4 These changes resulted in an increased TAG deposition in the subcutaneous adipose tissue. The increase in TAG deposition is primarily brought about by the large increase in abdominal subcutaneous ATBF and thereby increased supply of TAG to the capillary-bound lipoprotein lipase (LPL).21

We did not find similar metabolic changes in the present study. In addition, no changes were seen in arterial TAG concentrations during the experiment. The lack of effects on these parameters is very likely explained by the reduced/absent effects on ATBF. The absence of increase in ATBF implies a constant substrate supply to the capillary-bound LPL in adipose tissue and therefore no increase in the hydrolytic rate of TAG, as the activity of lipoprotein lipase is primarily limited by its substrate supply.21 The postprandial increase in ATBF helps to ensure optimization of the supply and thereby has an important role in minimizing the postprandial excursions of lipids early in the postprandial state.4, 9 Recent data indicate that the postprandial increase in blood flow in adipose tissue is partly or totally due to capillary recruitment. This capillary recruitment expands the endothelial surface area.22 In this way, increased ATBF will not only increase the TAG supply to the lipoprotein lipase but also expose more lipoprotein lipase to its substrate. Pasarica et al.6 recently showed decreased capillary density and reduced expression of angiogenic factors in abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue in overweight/obese subjects. These findings suggest that obese subjects in the fasting state, because of capillary refraction, might already have recruited the available capillaries and are therefore unable to recruit further. In a recent study it has been demonstrated that the microvasculature in adipose tissue is being remodeled in obesity.23 This remodeling results in a decreased capillary density and an increased amount of larger microvessels. However, whether the vascular effects of GIP in subcutaneous adipose tissue are due to increased microvascular volume changes or increased transit time in adipose tissue remains to be elucidated.

In the present study the applied insulin infusion rate demanded a glucose infusion rate during steady state of about the half of that demanded in our previous study with healthy subjects (NGT group 3.3 mg kg−1 min−1, IGT group 2.4 mg kg−1 min−1 and healthy subjects 5.8 mg kg−1 min−1, P<0.05). Therefore, it cannot be excluded that a similar vascular response in adipose tissue might be elicited in insulin-resistant subjects if a higher insulin infusion rate had been applied. This possibility has to be elucidated in future studies.

We applied the same formulation of synthetic GIP and the same infusion rate per kg body mass in the present study as we did in our previous study in healthy, lean subjects. This infusion rate raised GIP plasma levels to the physiological range in obese subjects.11 Therefore, it is unlikely that the reduced/absent effects of GIP in the present study are due to the inappropriately low dosing of the GIP. On the other hand, it cannot be excluded that higher infusion rates of GIP and insulin can elicit significant metabolic and vascular responses in adipose tissue in obese subjects. This possibility has to be studied in additional experiments.

We found a difference in ATBF response between the obese subjects with NGT and IGT. However, the transient increase in ATBF in the obese subjects with NGT did not affect the adipose tissue metabolism as seen in lean subjects. As neither GIP nor insulin per se regulates ATBF, the blunted effect of GIP and insulin in obese subjects could be due to a decreased sensitivity to one or both of these hormones. In humans, a major proportion of the postprandial enhancement of ATBF is under β-adrenergic regulation,24 which is elicited by central, partly insulin-mediated activation of sympathetic nerve activity. It has been demonstrated that the magnitude of the postprandial ATBF response correlates to insulin sensitivity.25 In obese subjects, the sympathetic regulation of ATBF might be changed because of the repeated activation of the autonomic nervous system by constant hyperinsulinemia. This may cause a blunted systemic sympathetic response or a local change in receptor distribution in the adipose tissue mediating a greater α-tone, thus favoring vasoconstriction. It has been shown that the α2-receptor activity is increased in adipose tissue in obese subjects.26

In lean, healthy subjects, the intracellular enzyme hormone-sensitive lipase is very rapidly suppressed by insulin postprandially. However, in obese subjects the hormone-sensitive lipase becomes insensitive to insulin and adipose tissue lipolysis continues despite increased plasma insulin concentrations.9 In the present study the adipose tissue glycerol release levels reveal that the lipolytic activity is inhibited to the same extent in the obese subjects with NGT as in the obese subjects with IGT. The FFA released from this remaining lipolytic activity can either be re-esterified in situ or released into the circulation. The ratio of glycerol to FFA release was used to estimate the extent of in situ FFA re-esterification. A ratio of about 3 indicates that the fatty acid released from the intracellular lipolysis is released into the circulation, whereas a ratio of ∼0 indicates that the released fatty acids are re-esterificated and stored as TAG again.27 In both groups the in situ FFA re-esterification increased, as judged from the FFA/glycerol release ratio. Pre-infusion FFA/glycerol ratios were ∼2.4; however, they decreased to a lesser extent in the IGT group and were significantly higher 90–180 min after commencement of the clamp compared with the ratio found in the subjects with NGT (Figure 4). Therefore, the in situ re-esterification of fatty acids was significantly reduced in the IGT subjects. This is probably due to the inability to increase the glucose metabolism in the adipocytes sufficiently under the clamp conditions applied. As adipose tissue does not have much glycerol kinase activity, glucose is necessary for the glycerol formation needed for fatty acid re-esterification in adipose tissue.27 The combination of impaired inhibition of lipolysis and low ability to re-esterify results in surplus release of fatty acids from the adipose tissue compared with the metabolic demand.

The perspectives of the present findings are therefore that blunted ATBF response due to GIP/insulin resistance in hypertrophic adipose tissue results in decreased deposition/retention of TAG in the tissue postprandially. This will promote prolonged postprandial lipidemia, and excess lipid deposition in other tissues such as the liver and skeletal muscle; the latter has been demonstrated to lead to further insulin resistance in the muscles.

References

Falko JM, Crockett SE, Cataland S, Mazzaferri EL . Gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) stimulated by fat ingestion in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1975; 41: 260–265.

Kuzio M, Dryburgh JR, Malloy KM, Brown JC . Radioimmunoassay for gastric inhibitory polypeptide. Gastroenterology 1974; 66: 357–364.

Ross SA, Dupre J . Effects of ingestion of triglyceride or galactose on secretion of gastric inhibitory polypeptide and on responses to intravenous glucose in normal and diabetic subjects. Diabetes 1978; 27: 327–333.

Asmar M, Simonsen L, Madsbad S, Stallknecht B, Holst JJ, Bulow J . Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide may enhance fatty acid re-esterification in subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue in lean humans. Diabetes 2010; 59: 2160–2163.

Asmar M, Tangaa W, Madsbad S, Hare K, Astrup A, Flint A et al. On the role of glucose-dependent insulintropic polypeptide in postprandial metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010; 298: E614–E621.

Paschetta E, Hvalryg M, Musso G . Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide: from pathophysiology to therapeutic opportunities in obesity-associated disorders. Obes Rev 2011; 12: 813–828.

McClean PL . GIP receptor antagonism reverses obesity, insulin resistance, and associated metabolic disturbances induced in mice by prolonged consumption of high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007; 293: E1746–E1755.

Miyawaki K . Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents obesity. Nat Med 2002; 8: 738–742.

Frayn KN . Adipose tissue as a buffer for daily lipid flux. Diabetologia 2002; 45: 1201–1210.

Summers LK, Samra JS, Humphreys SM, Morris RJ, Frayn KN . Subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue blood flow: variation within and between subjects and relationship to obesity. Clin Sci (Lond) 1996; 91: 679–683.

Carr RD, Larsen MO, Jelic K, Lindgren O, Vikman J, Holst JJ et al. Secretion and dipeptidyl peptidase-4-mediated metabolism of incretin hormones after a mixed meal or glucose ingestion in obese compared to lean, nondiabetic men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 872–878.

Gavin JR, KGMM Alberti, Davidson MB, DeFronzo RA, Drash A, Gabbe SG et al. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 1183–1197.

Simonsen L, Enevoldsen LH, Bulow J . Determination of adipose tissue blood flow with local 133Xe clearance. Evaluation of a new labelling technique. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2003; 23: 320–323.

Deacon CF, Nauck MA, Meier J, Hucking K, Holst JJ . Degradation of endogenous and exogenous gastric inhibitory polypeptide in healthy and in type 2 diabetic subjects as revealed using a new assay for the intact peptide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 3575–3581.

Bulow J, Jelnes R, Astrup A, Madsen J, Vilmann P . Tissue/blood partition coefficients for xenon in various adipose tissue depots in man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1987; 47: 1–3.

Bulow J . Adipose tissue blood flow during exercise. Dan Med Bull 1983; 30: 85–100.

Simonsen L, Ryge C, Bulow J . Glucose-induced thermogenesis in splanchnic and leg tissues in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1995; 88: 543–550.

Bulow J, Madsen J . Influence of blood flow on fatty acid mobilization form lipolytically active adipose tissue. Pflugers Arch 1981; 390: 169–174.

Karpe F . Effects of insulin on adipose tissue blood flow in man. J Physiol 2002; 540: 1087–1093.

Stallknecht B . Effect of training on insulin sensitivity of glucose uptake and lipolysis in human adipose tissue. Am J Physiolog Endocrinol Metab 2000; 279: E376–E385.

Samra JS, Simpson EJ, Clark ML, Forster CD, Humphreys SM, Macdonald IA et al. Effects of epinephrine infusion on adipose tissue: interactions between blood flow and lipid metabolism. Am J Physiol 1996; 271 (Part 1): E834–E839.

Tobin L, Simonsen L, Bulow J . Real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound determination of microvascular blood volume in abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue in man. Evidence for adipose tissue capillary recruitment. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2010; 30: 447–452.

Spencer M, Unal R, Zhu B, Rasouli N, McGehee RE Jr., Peterson CA et al. Adipose tissue extracellular matrix and vascular abnormalities in obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: E1990–E1998.

Ardilouze JL, Fielding BA, Currie JM, Frayn KN, Karpe F . Nitric oxide and beta-adrenergic stimulation are major regulators of preprandial and postprandial subcutaneous adipose tissue blood flow in humans. Circulation 2004; 109: 47–52.

Karpe F . Impaired postprandial adipose tissue blood flow response is related to aspects of insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 2002; 51: 2567–2473.

Stich V . Activation of alpha(2)-adrenergic receptors impairs exercise-induced lipolysis in SCAT of obese subjects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2000; 279: R499–R504.

Van HG, Bulow J, Sacchetti M, Al MN, Lyngso D, Simonsen L . Regional fat metabolism in human splanchnic and adipose tissues; the effect of exercise. J Physiol 2002; 543 (Pt 3): 1033–1046.

Acknowledgements

The technical assistance of Jeppe Bach and Sofie Pilgaard is gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

MA designed the study, recruited the subjects, supervised the studies, collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. LS supervised the studies, reviewed and edited the manuscript. N.A. recruited the subjects, collected the data and reviewed the manuscript. JJH analyzed the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript. FD analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript. JB designed the study, supervised the studies, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asmar, M., Simonsen, L., Arngrim, N. et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide has impaired effect on abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue metabolism in obese subjects. Int J Obes 38, 259–265 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.73

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.73

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

GIP receptor agonism improves dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis independently of body weight loss in preclinical mouse model for cardio-metabolic disease

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2023)

-

Repository Describing the Anatomical, Physiological, and Biological Changes in an Obese Population to Inform Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Models

Clinical Pharmacokinetics (2022)

-

GIP(3-30)NH2 is an efficacious GIP receptor antagonist in humans: a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study

Diabetologia (2018)

-

The effect of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) variants on visceral fat accumulation in Han Chinese populations

Nutrition & Diabetes (2017)

-

The blunted effect of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue in obese subjects is partly reversed by weight loss

Nutrition & Diabetes (2016)