Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to examine whether childhood cardiorespiratory fitness attenuates or modifies the long-term cardiometabolic risks associated with childhood obesity.

Design and Methods:

The study consisted of a 20-year follow-up of 1792 adults who participated in the 1985 Australian Schools Health and Fitness Survey when they were 7–15 years of age. Baseline measures included a 1.6-km run to assess cardiorespiratory fitness and waist circumference to assess abdominal adiposity. At follow-up, participants attended study clinics where indicators of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) (waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose and lipids) were measured and cardiorespiratory fitness was reassessed using a submaximal graded exercise test.

Results:

Both high waist circumference and low cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood were significant independent predictors of MetS in early adulthood. The mutually adjusted relative risk of adult MetS was 3.00 (95% confidence interval: 1.85–4.89) for children in the highest (vs lowest) third of waist circumference and 0.64 (95% confidence interval: 0.43–0.96) for children with high (vs low) cardiorespiratory fitness. No significant interaction between waist circumference and fitness was observed, with higher levels of childhood fitness associated with lower risks of adult MetS among those with either low or high childhood waist circumference values. Participants who had both high waist circumference and low cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood were 8.5 times more likely to have MetS in adulthood than those who had low waist circumference and high cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood. Regardless of childhood obesity status, participants with low childhood fitness who increased their relative fitness by adulthood had a substantially lower prevalence of MetS than those who remained low fit.

Conclusions:

Childhood waist circumference and cardiorespiratory fitness are both strongly associated with cardiometabolic health in later life. Higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness substantially reduce the risk of adult MetS, even among those with abdominal obesity in childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the 1980s, there has been a marked increase in the proportion of children living in developed countries who are overweight or obese.1 Although there is evidence that these rates may have plateaued in some countries,2 the current high prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity has substantial public health implications given that childhood obesity is associated with adverse metabolic health profiles in childhood and adolescence3, 4 and these adverse risk profiles persist into adulthood.5, 6, 7 Once established, excess adiposity in childhood is difficult to reverse as most obese children will continue to be overweight or obese in early adulthood.8, 9 Accordingly, an important public health priority is to identify behaviors or treatments that can reduce both the short- and long-term metabolic health risks that result from childhood obesity.

Among adults, higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness have been observed to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality among normal weight, overweight and obese individuals.10, 11, 12, 13 In fact, compared with normal weight adults with low cardiorespiratory fitness, obese but aerobically fit adults have been reported in some studies to have a similar, or lower, risk for metabolic syndrome (MetS),14 type 2 diabetes15 and major cardiovascular disease events.16 The joint influences of fitness and fatness on cardiometabolic health indicators in youth have also been explored, with studies generally reporting weaker beneficial effects for cardiorespiratory fitness in comparison with the deleterious effects of excess fatness.17, 18, 19, 20 However, studies conducted to date among youth have been predominantly cross-sectional in design21, 22 or longitudinal studies limited by small sample size19, 23 and/or a short follow-up period.24, 25

Given the above noted limitations, the extent to which improved cardiorespiratory fitness can attenuate or modify the long-term health risks associated with excess childhood adiposity remains unclear. The potential for sex and age to modify the long-term influence of childhood cardiorespiratory fitness and childhood adiposity on adult health outcomes also remains inadequately explored. The current study sought to examine these issues using data from a 20-year follow-up of an Australian cohort with cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition and cardiometabolic health measures taken both in childhood and adulthood.

Materials and methods

Data for these analyses were collected as part of the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health (CDAH) study, a 20-year follow-up of 8498 children aged 7–15 years who participated in the Australian Schools Health and Fitness Survey (ASHFS) in 1985. Sampling procedures and methods of data collection for ASHFS have been described elsewhere.26 Follow-up of ASHFS participants was performed from May 2004 to May 2006 when participants were aged 26–36 years; 6840 (81%) were able to be located and 5170 (61%) subsequently enrolled and provided follow-up data. Of those, 2410 attended one of 34 study clinics around Australia for physical measurements and blood sampling. Clinics were located to maximize the proportion of participants living within a 10 km radius, of which 55% attended. The CDAH study was approved by the Southern Tasmanian Medical Research Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

These analyses were restricted to the 1792 participants who were not pregnant at follow-up, provided a fasting blood sample at the follow-up clinic and had waist circumference and cardiorespiratory fitness measured at both time points. Participants were similar to the baseline sample according to sex (49.8 vs 47.7% female, P=0.11) but participants had a lower body mass index (18.0 vs 18.3 kg m−2, P<0.001), waist circumference (63.2 vs 63.7 cm, P=0.02) and 1.6 km run time (9.2 vs 9.5 min, P<0.001) and were more likely to have lived in a higher socioeconomic area (29.8 vs 21.9% in highest category, P<0.001) in childhood. However, the increase in body mass index from child to adulthood was similar between participants in this analysis and the 2968 non-participants who reported height and weight at follow-up enrollment (mean increase in body mass index 7.0 vs 6.8 kg m−2, P=0.25).

Body composition measures

Height was measured at both time points without shoes to the nearest 0.1 cm using a KaWe height tape (KaWe Kirchner & Wilhelm, Asperg, Germany) or rigid metric measuring tape and plastic set square at baseline and a portable stadiometer at follow-up. Weight was measured in light clothing without shoes at both time points: to the nearest 0.5 kg at baseline using a beam or medical spring scale and to the nearest 0.1 kg at follow-up using a digital Heine portable scale (Heine, Dover, NH, USA). Body mass index was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm at the level of the umbilicus at baseline and at the narrowest point between the lower costal border and iliac crest at follow-up using a constant tension tape.

Cardiorespiratory fitness measures

Cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood was estimated by a 1.6 km (1 mile) run over a level, marked course with children advised on appropriate pacing and motivated to give maximum effort. The time to complete a 1.6-km run has been shown to be strongly correlated with Vo2max (−0.85 to −0.73) and has been commonly used as a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood.27 To facilitate comparisons with the fitness levels of contemporary children, run times were used to estimate Vo2max based on the widely used equation by Cureton et al.28 At follow-up, cardiorespiratory fitness was estimated based on physical work capacity at a heart rate of 170 beats per minute (PWC-170) using a standardized protocol29 on a Monark cycle ergometer. As PWC-170 is a function of muscle mass, values were expressed relative to lean body mass, estimated as the product of body mass and (100−percent body fat). Percent body fat was calculated from body density using the equation specified by Siri30 with body density estimated by entering the sum of tricep, bicep, subscapular and iliac crest skin-fold thicknesses into the sex-specific equations of Durnin and Womersley.31

Clinical measures at follow-up

Blood pressure was measured after 5 min of quiet sitting using an OMRON HEM907 Digital Automatic Blood Pressure Monitor (Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with the mean of three readings used for analysis. Blood samples (32 ml) were collected after an overnight fast and assays conducted to enzymatically measure fasting glucose, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides using an Olympus AU5400 automated analyzer (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). Fasting plasma insulin was measured by both microparticle enzyme (AxSYM; Abbot Laboratories, Abbot Park, IL, USA) and electrochemiluminescence immunoassays (Elecsys Modular Analytics E170, Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Switzerland) with inter-assay standardization. The homeostasis model assessment estimated insulin resistance, the product of fasting insulin (mU ml−1) and fasting glucose (mmol l−1) divided by 22.5, was used to estimate insulin sensitivity and insulin resistance, defined as a homeostasis model assessment estimated insulin resistance index at or above the 90th sex-specific percentile.

MetS status was determined using the 2009 consensus definition proposed by the International Diabetes Federation, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and other international organizations.32 Specifically, participants were classified as having MetS when three or more of the following conditions were met: waist circumference ⩾102 cm (men) or ⩾88 cm (women); raised blood pressure (systolic ⩾130 mm Hg or diastolic ⩾85 mm Hg or treatment of diagnosed hypertension); high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <1.0 mmol l−1 (<40 mg dl−1) in men or <1.29 mmol l−1 (<50 mg dl−1) in women or treatment for this lipid abnormality; triglycerides ⩾1.70 mmol l−1 (⩾150 mg dl−1) or drug treatment for elevated triglycerides; and fasting plasma glucose ⩾5.6 mmol l−1 (⩾ 100 mg dl−1) or treatment for elevated blood glucose.

Covariate measures

Smoking and alcohol intake in adulthood were ascertained using self-completed questionnaires. Residential postcode at baseline was used to derive area-level socioeconomic status based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage derived from the 1981 population census, with the study participants classified into quartiles. Additional details have been published elsewhere.8

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of participants included in this analysis were compared with other participants using the t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables (results presented earlier). Mean and standard deviation values or, for skewed variables, median and interquartile values were calculated for measures of body composition and fitness in childhood and adulthood and for adult cardiometabolic risk factors.

For the primary analyses, waist circumference and cardiorespiratory fitness values were converted to age- and sex-specific percentiles based on the analysis sample (necessary for interpretation of change in percentile scores). A categorical waist circumference variable was created based on tertile cutpoints. To allow comparison with prior studies, categories of childhood cardiorespiratory fitness were created based on those used in the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study (that is, <20th percentile (low), 20–59th percentile (moderate) and ⩾60th percentile (high)).

Analyses were initially conducted separately by sex and childhood age (7–11 years vs 12–15 years; roughly corresponding to pubertal status) to explore potential differences across these plausible effect modifiers. As no significant differences across strata were observed, we present results for the sample as a whole with stratified results presented in the online-only supplement. Independent and mutually adjusted predictive associations between childhood waist circumference and cardiorespiratory fitness measures with MetS in adulthood were quantified using log binomial regression models adjusted for sex, childhood age and duration of follow-up. The combined effect of childhood waist circumference and fitness on adult risk of MetS was evaluated by quantifying adult metabolic risk across joint waist circumference and cardiorespiratory fitness categories. Additional adjustment for adult alcohol consumption and smoking status led to minimal (<5%) changes in coefficient values and were not included in the final models.

Following an approach we have previously used,33 we created an indicator of changes in cardiorespiratory fitness status over the course of the study. Specifically, participants who were in the lowest fitness tertile in both childhood and adulthood were classified as having ‘persistent low fitness’, those who moved from a moderate or high tertile in childhood to the low fitness tertile in adulthood were classified as having ‘decreasing fitness’, those who moved from the lowest tertile in childhood to a moderate or high fitness tertile in adulthood were classified as having ‘increasing fitness’, and those who were in the moderate or high fitness tertile at both times were classified as having ‘persistent fitness’. This indicator was used to evaluate the association between cardiorespiratory fitness change and adult MetS by childhood central obesity status. SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analytic procedures.

Results

Childhood and adult body composition and adult cardiometabolic measures are described for the analysis sample in Table 1. The mean (s.d.) length of follow-up was 19.9 (0.6) years and the mean (s.d.) age at follow-up was 31.0 (2.6) years. As expected, the overall prevalence of MetS was relatively low in this population-based sample of young adults but higher in males than females (10.1 vs 4.0%).

Compared with those who were in the lowest third, having a childhood waist circumference in the highest third was associated with an approximate threefold increased risk of adult MetS, even after adjusting for childhood cardiorespiratory fitness (Table 2). In contrast, a higher childhood fitness level was associated with a 54% reduced risk of adult MetS compared with those with low childhood fitness but was attenuated to a 36% reduction in risk after adjusting for childhood waist circumference. When examined separately by sex, associations between childhood waist circumference and MetS were stronger among females than males, but these differences were not statistically significant (P=0.25 for interaction; Supplementary Table S1 in online supplement). Associations between childhood cardiorespiratory fitness level and MetS were more similar between males and females (P=0.78 for interaction), while a comparison of associations across strata of childhood age (7–11 years vs 12–15 years) also failed to detect any substantial differences (Supplementary Table S2 in online supplement).

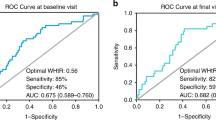

When participants were categorized based on both childhood waist circumference and fitness level, adult MetS risk generally increased with lower cardiorespiratory fitness or higher waist circumference such that those with the lowest fitness level and highest waist circumference in childhood were over eight times more likely to have adult MetS compared with those in the high fit/low waist circumference group (Figure 1). However, no significant multiplicative interaction between childhood cardiorespiratory fitness and waist circumference was observed in this cohort in relation to adult MetS risk (P=0.61). That is, the risks associated with elevated childhood waist circumference were relatively consistent regardless of childhood fitness level and vice versa.

Relative risk (RR) of adult MetS across categories of childhood waist circumference and fitness. Adjusted for age, sex and length of follow-up. Reference group is lowest waist circumference/highest fitness group. aChildhood fitness categories are <20th percentile (low), 20–59th percentile (moderate), and ⩾60th percentile (high).

The risk of meeting each component criteria of MetS was also examined across joint categories of childhood waist circumference and cardiorespiratory fitness level (Table 3). These results clearly indicate that children with higher waist circumference and lower fitness have a much higher risk of having an elevated waist circumference in adulthood and that it is this relationship which accounts for much of the association between these childhood measures and adult MetS risk. Nonetheless, participants in the high waist circumference/low fitness category in childhood were at significantly higher risk for meeting each of the component MetS criteria in adulthood except for elevated glucose level. In addition, these participants were also more likely to be classified as insulin resistant, an indicator closely associated with MetS but not a criterion used to define MetS in the current study.

Figure 2 shows the proportion of participants with MetS in adulthood across categories of child to adult cardiorespiratory fitness change stratified by central adiposity status in childhood. Regardless of childhood central adiposity status, risk of MetS was highest among those in the persistent low fitness and decreasing fitness groups. However, the absolute reductions in MetS risk were substantially larger among those with high central adiposity in childhood (20.5% absolute reduction across persistent low to persistent high fitness groups) compared with those who were not overweight (5.4% absolute reduction across fitness groups). Conversely, the absolute increase in MetS risk associated with having high central adiposity in childhood was much greater among those who were persistently low fit (16.3% absolute increase) compared with those who were persistently high fit (1.2% absolute increase).

Discussion

Elevated adiposity in childhood has been associated with adverse cardiometabolic profiles and outcomes in adulthood in this5 and other cohorts.6, 7, 34 This analysis sought to determine the extent to which cardiorespiratory fitness levels in childhood and adulthood counteract or modify these risks. In a nationwide sample of Australians followed over a 20-year period, we observed childhood cardiorespiratory fitness levels to strongly influence adult MetS risk; with individuals in higher fitness categories having substantially lower MetS risk across most levels of childhood waist circumference. However, higher childhood fitness was not observed to modify the relative risks associated with higher abdominal adiposity, which increased MetS risk independently of cardiorespiratory fitness status.

Although the magnitude of adult MetS risk associated with high waist circumference and low cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood was substantial, most of this risk appears to be imparted via higher adult waist circumference. This is perhaps not unexpected given the robust correlation between child and adult waist circumference previously reported for this cohort (0.45 for both males and females).5 Nonetheless, lower waist circumference and higher fitness were associated with improved profiles for other components of the MetS as well as a reduced risk for insulin resistance, a key metabolic characteristic associated with MetS and future risk of type 2 diabetes.35 Although these results support the importance of childhood cardiorespiratory fitness in predicting cardiometabolic health in adulthood, we observed that adult fitness level was also an important determinant of adult cardiometabolic health. For example, among participants with low fitness in childhood, those who increased their relative fitness level by adulthood had a markedly lower prevalence of MetS than those who remained low fit, which was true regardless of central obesity status in childhood.

The current findings add to a robust body of observational research related to the independent and joint effects of cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity on cardiometabolic health outcomes.14, 16, 36, 37 Few prior studies, however, have examined associations between cardiorespiratory fitness in early life and cardiometabolic health outcomes in adulthood and the extent to which fitness levels can attenuate the long-term adverse effects of elevated adiposity. For example, the majority of studies that explore associations between childhood adiposity and fitness with metabolic health indicators have been cross-sectional20, 38, 39 or have had relatively short follow-up periods.24, 40, 41 Among those studies that have examined associations between fitness during childhood or adolescence and cardiometabolic outcomes over longer time periods, results have been mixed. The CARDIA study42 observed that low cardiorespiratory fitness at age 18 was associated with an approximate fourfold increased risk of MetS over 7 years of follow-up in comparison with those who were high fit at baseline. However, this association was observed only among those non-obese at baseline. The Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study observed relatively weak associations between cardiorespiratory fitness at age 13–16 years and cardiometabolic risk factor profiles at age 32 with significant inverse associations only reported for sum of skinfolds, waist circumference and total cholesterol.43 Both of the above studies used graded maximal treadmill tests to exhaustion to measure cardiorespiratory fitness.

Few studies have compared associations between childhood cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity with cardiometabolic risk factor profiles in adulthood. Most comparable with the current study was a follow-up of a small sample in the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study19 who were followed from adolescence to an average age of 30 years. In this study, adolescent adiposity, but not treadmill-measured cardiorespiratory fitness, was related to cardiovascular risk factors in adulthood. However, adolescent fitness was found to be predictive of adult adiposity, as we observed in the current study.

It is important to note that the current findings are based on the distribution of waist circumference and fitness levels among Australian children in 1985. Thirty years later, evidence suggests that levels of total and central adiposity in childhood have increased globally,44, 45 while cardiorespiratory fitness levels have decreased.46 Compared with children of similar age in this study, a representative sample of children living in New South Wales, Australia in 2010 had 85th percentile waist circumference values that were 2.0 cm and 4.4 cm higher among 7–8- and 13–14-year-old boys, respectively. Among girls, 85th percentile values were 0.7–3.5 cm higher in 2010 for these same age groups. These secular trends suggest that the observed cardiometabolic risks associated with higher waist circumference values may underestimate the risks faced by contemporary populations of children who have more extreme levels of abdominal adiposity. In contrast, pediatric cardiorespiratory fitness test performance is estimated to have decreased at an average annual rate of 0.56% in Australasia and 0.46% worldwide from 1970 to 2000.46 Indeed, based on their estimated Vo2max, only 2.1% of males and 10.3% of females aged 10–15 years in this study cohort would be classified as below the ‘healthy fitness zone’ cutpoints for aerobic capacity on the US Fitnessgram assessment. This is dramatically lower than the recently published rates for similarly aged US children, where 38–46% of males and 49–59% of females fell below the healthy fitness zone (percentages varied by age).47 Therefore, fewer contemporary children may achieve the level of cardiorespiratory fitness needed to derive long-term cardiometabolic benefits or to partially offset the negative effects of higher abdominal adiposity.

Despite several key strengths of the current study, there are a number of limitations that should be considered when interpreting these findings. One limitation is the large proportion of participants with baseline data who were lost to follow-up and not included in these analyses. Primary reasons for non-inclusion consist of the inability to contact 19% of the baseline participants and non-attendance at one of the 34 study clinics held throughout the country (32% of baseline). While participants significantly differed from non-participants in terms of baseline body composition (lower), fitness (higher) and socioeconomic status (higher), these differences were small in magnitude and the change in body composition over the study follow-up period was similar between the participants included in this analysis and those unable to attend a study clinic. The effect of this loss to follow-up on observed associations would depend upon the association between childhood fitness and adiposity with adult MetS status among those lost to follow-up. To the extent that the association between these factors differed among non-participants and participants, the observed associations would deviate from the true cardiometabolic risks associated with abdominal adiposity and low cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood.

Another limitation is the lack of information regarding pubertal status at baseline, which hindered our ability to ascertain potential differences in the long-term effects of adiposity and fitness pre- and post-pubertal onset. However, to the extent that age can serve as a surrogate indicator of pubertal status, there did not appear to be significantly different associations among pre-teen and early-teen participants. In addition, we used a field test of cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood that was likely influenced by participant effort. However, the 1.6 km run is a commonly used measure in youth populations—including the Fitnessgram.48 It has also been shown to be correlated with laboratory measures of Vo2max27, 28 in similar aged participants. However, because of the limited feasibility of the 1.6 km test as a measure of fitness in population-based samples of adults, a submaximal cycle ergometer exercise test was used to estimate adult fitness. Because of these different procedures, relative (that is, percentile scores) rather than absolute changes in cardiorespiratory fitness were measured over time and limit the interpretation of the results accordingly. Further, the use of different fitness test procedures may have led to the misclassification of changes in fitness over the course of the study and would be expected to attenuate observed associations with MetS. Nonetheless, we observed strong associations between the change in cardiorespiratory fitness and adult MetS risk and these results are in general agreement with the few other studies to examine similar associations in adolescents49 and young adults.42

In conclusion, these findings suggest that increasing cardiorespiratory fitness levels among children, regardless of weight status, could reduce the absolute risk of developing MetS in young adulthood. Our results also indicate that adult cardiometabolic health may be further enhanced by maintaining or increasing one’s relative level of cardiorespiratory fitness into adulthood, especially among those with higher levels of abdominal adiposity. However, this study also provides additional evidence that central obesity in childhood confers substantial long-term risks to cardiometabolic health and that these risks cannot be fully offset by higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness.

References

Wang Y, Lobstein T . Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes 2006; 1: 11–25.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM . Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. JAMA 2010; 303: 242–249.

Weiss R, Caprio S . The metabolic consequences of childhood obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 19: 405–419.

Daniels SR . Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33 (Suppl 1): S60–S65.

Schmidt MD, Dwyer T, Magnussen CG, Venn AJ . Predictive associations between alternative measures of childhood adiposity and adult cardio-metabolic health. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011; 35: 38–45.

Mattsson N, Ronnemaa T, Juonala M, Viikari JS, Raitakari OT . Childhood predictors of the metabolic syndrome in adulthood. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Ann Med 2008; 40: 542–552.

Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1876–1885.

Venn AJ, Thomson RJ, Schmidt MD, Cleland VJ, Curry BA, Gennat HC et al. Overweight and obesity from childhood to adulthood: a follow-up of participants in the 1985 Australian Schools Health and Fitness Survey. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 458–460.

Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ . Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 474–488.

LaMonte MJ, Barlow CE, Jurca R, Kampert JB, Church TS, Blair SN . Cardiorespiratory fitness is inversely associated with the incidence of metabolic syndrome: a prospective study of men and women. Circulation 2005; 112: 505–512.

LaMonte MJ, Blair SN . Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and adiposity: contributions to disease risk. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2006; 9: 540–546.

Sui X, Hooker SP, Lee IM, Church TS, Colabianchi N, Lee CD et al. A prospective study of cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 550–555.

Wei M, Kampert JB, Barlow CE, Nichaman MZ, Gibbons LW, Paffenbarger RS Jr et al. Relationship between low cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality in normal-weight, overweight, and obese men. JAMA 1999; 282: 1547–1553.

Church TS, Finley CE, Earnest CP, Kampert JB, Gibbons LW, Blair SN . Relative associations of fitness and fatness to fibrinogen, white blood cell count, uric acid and metabolic syndrome. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002; 26: 805–813.

Wei M, Gibbons LW, Mitchell TL, Kampert JB, Lee CD, Blair SN . The association between cardiorespiratory fitness and impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus in men. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 89–96.

Wessel TR, Arant CB, Olson MB, Johnson BD, Reis SE, Sharaf BL et al. Relationship of physical fitness vs body mass index with coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events in women. JAMA 2004; 292: 1179–1187.

Boreham C, Twisk J, Murray L, Savage M, Strain JJ, Cran G . Fitness, fatness, and coronary heart disease risk in adolescents: the Northern Ireland Young Hearts Project. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001; 33: 270–274.

Eisenmann JC, Welk GJ, Wickel EE, Blair SN . Combined influence of cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index on cardiovascular disease risk factors among 8-18 year old youth: The Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study. Int J Pediatr Obes 2007; 2: 66–72.

Eisenmann JC, Wickel EE, Welk GJ, Blair SN . Relationship between adolescent fitness and fatness and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adulthood: The Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study (ACLS). Am Heart J 2005; 149: 46–53.

Silva G, Aires L, Martins C, Mota J, Oliveira J, Ribeiro JC . Cardiorespiratory fitness associates with metabolic risk independent of central adiposity. Int J Sports Med 2013; 34: 912–916.

Andersen LB, Sardinha LB, Froberg K, Riddoch CJ, Page AS, Anderssen SA . Fitness, fatness and clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in children from Denmark, Estonia and Portugal: the European Youth Heart Study. Int J Pediatr Obes 2008; 3 (Suppl 1):58–66.

Kwon S, Burns TL, Janz KF . Associations of cardiorespiratory fitness and fatness with cardiovascular risk factors among adolescents: The NHANES 1999-2002. J Phys Act Health 2010; 7: 746–753.

Carson V, Rinaldi RL, Torrance B, Maximova K, Ball GDC, Majumdar SR et al. Vigorous physical activity and longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in youth. Int J Obes 2014; 38: 16–21.

Andersen LB, Bugge A, Dencker M, Eiberg S, El-Naaman B . The association between physical activity, physical fitness and development of metabolic disorders. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011; 6: 29–34.

Janz KF, Dawson JD, Mahoney LT . Increases in physical fitness during childhood improve cardiovascular health during adolescence: the Muscatine Study. Int J Sports Med 2002; 23 (Suppl 1):S15–S21.

Dwyer T, Gibbons LE . The Australian Schools Health and Fitness Survey. Physical fitness related to blood pressure but not lipoproteins. Circulation 1994; 89: 1539–1544.

George JD, Vehrs PR, Allsen PE, Fellingham GW, Fisher GA . VO2max estimation from a submaximal 1-mile track jog for fit college-age individuals. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993; 25: 401–406.

Cureton KJ, Sloniger MA, O'Bannon JP, Black DN, McCormack WP . A generalized equation for prediction of VO2 peak from one-mile run/walk performance in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995; 27: 445–451.

Withers RT, Davies GJ, Crouch RG . A comparison of three W170 protocols. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1977; 37: 123–128.

Siri WE . The gross composition of the body. Adv Biol Med Phys 1956; 4: 239–280.

Durnin JV, Womersley J . Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr 1974; 32: 77–97.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009; 120: 1640–1645.

Dwyer T, Magnussen CG, Schmidt MD, Ukoumunne OC, Ponsonby AL, Raitakari OT et al. Decline in physical fitness from childhood to adulthood associated with increased obesity and insulin resistance in adults. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 683–687.

Park MH, Falconer C, Viner RM, Kinra S . The impact of childhood obesity on morbidity and mortality in adulthood: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2012; 13: 985–1000.

NCEP. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, elevation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA 2001; 285: 2486–2497.

Stevens J, Cai J, Evenson KR, Thomas R . Fitness and fatness as predictors of mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease in men and women in the lipid research clinics study. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 832–841.

Lee S, Kuk JL, Katzmarzyk PT, Blair SN, Church TS, Ross R . Cardiorespiratory fitness attenuates metabolic risk independent of abdominal subcutaneous and visceral fat in men. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 895–901.

Eisenmann JC, Welk GJ, Ihmels M, Dollman J . Fatness, fitness, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007; 39: 1251–1256.

Nyberg G, Ekelund U, Yucel-Lindberg TL, Mode RT, Marcus C . Differences in metabolic risk factors between normal weight and overweight children. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011; 6: 244–252.

Puder JJ, Schindler C, Zahner L, Kriemler S . Adiposity, fitness and metabolic risk in children: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011; 6: e297–e306.

Telford RD, Cunningham RB, Telford RM, Kerrigan J, Hickman PE, Potter JM et al. Effects of changes in adiposity and physical activity on preadolescent insulin resistance: The Australian LOOK Longitudinal Study. Plos One 2012; 7: 6.

Carnethon MR, Gidding SS, Nehgme R, Sidney S, Jacobs DR Jr, Liu K . Cardiorespiratory fitness in young adulthood and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors. JAMA 2003; 290: 3092–3100.

Twisk JW, Kemper HC, van Mechelen W . The relationship between physical fitness and physical activity during adolescence and cardiovascular disease risk factors at adult age. The Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Int J Sports Med 2002; 23 (Suppl 1): S8–14.

Dollman JT, Olds S . Secular changes in fatness and fat distribution in Australian children matched for body size. Int J Pediatr Obes 2006; 1: 109–113.

Prentice AM . The emerging epidemic of obesity in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 93–99.

Tomkinson GR, Olds TS . Secular changes in pediatric aerobic fitness test performance: The global picture. Med Sport Sci 2007; 50: 46–66.

Bai Y, Saint-Maurice PF, Welk GJ, Allums-Featherston K, Candelaria N, Anderson K . Prevalence of youth fitness in the United States: Baseline results from the NFL PLAY 60 FITNESSGRAM partnership project. J Pediatr 2015; 167: 662–668.

Plowman SA . Muscular strength, endurance, and flexibility assessments. In: Plowman SA, Meredith MD (eds), Fitnessgram/Activitygram Reference Guide 4th ed. The Cooper Institute: Dallas, TX, USA, pp 8–55.

Hasselstrom H, Hansen SE, Froberg K, Andersen LB . Physical fitness and physical activity during adolescence as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in young adulthood. Danish Youth and Sports Study. An eight-year follow-up study. Int J Sports Med 2002; 23 (Suppl 1): S27–S31.

Acknowledgements

The Childhood Determinants of Adult Health study was funded by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian National Heart Foundation, the Tasmanian Community Fund, and Veolia Environmental Services. Financial support was also provided by Sanitarium Health Food Company, ASICS Oceania, and Target Australia. Dr Schmidt was supported by a National Heart Foundation of Australia postdoctoral fellowship. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study’s project manager, Marita Dalton, all other project staff and volunteers, and the study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, M., Magnussen, C., Rees, E. et al. Childhood fitness reduces the long-term cardiometabolic risks associated with childhood obesity. Int J Obes 40, 1134–1140 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.61

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.61

This article is cited by

-

Virtual fitness buddy ecosystem: a mixed reality precision health physical activity intervention for children

npj Digital Medicine (2024)

-

The Impact of Typical School Provision of Physical Education, Physical Activity and Sports on Adolescent Physical Health: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis

Adolescent Research Review (2024)

-

Effects of Movement Behaviors on Overall Health and Appetite Control: Current Evidence and Perspectives in Children and Adolescents

Current Obesity Reports (2022)

-

The relationship between multiple perfluoroalkyl substances and cardiorespiratory fitness in male adolescents

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

-

Disparities in physical fitness of 6–11-year-old children: the 2012 NHANES National Youth Fitness Survey

BMC Public Health (2020)