Abstract

Norcantharidin (NCTD) was shown in our previous studies to attenuate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in rat models with diabetic nephropathy (DN). The aim of this study was to determine the effects of NCTD on the expression of extracellular matrix (ECM) and TGF-β1 in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose and on calcineurin (CaN)/NFAT pathway. Whether or not the antifibrotic effect of NCTD on renal interstitium was dependent on its inhibition of CaN pathway was also investigated. Experimental concentrations of NCTD were verified by cytotoxic test and MTT assay. HK-2 cells were transfected with CaN small interference RNA (siRNA). The mRNA and protein expressions of FN, ColIV, TGF-β1, and CaN in HK-2 cells were detected by real-time PCR and western blot. The CaN/NFAT pathway was examined by indirect immunofluorescence and western blot. Our study revealed that NCTD concentrations over 5 mg/l had overt cytotoxicity on HK-2 cells. Meanwhile, both 2.5 and 5 mg/l NCTD inhibited HK-2 cell proliferation (P<0.05). NCTD inhibited the upregulation of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 of HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose (P<0.05), and also significantly downregulated the expression of CaN mRNA and protein in HK-2 cells (P<0.05). In addition, not only was the nuclear translocation of NFATc inhibited, but its protein level in the nucleus was also reduced. Following CaN siRNA transfection, CaN mRNA and protein expression were significantly decreased. In contrast, the protein levels of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 increased in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose (P<0.05). However, NCTD treatment downregulated their expression. These results indicated that NCTD could decrease the expression of ECM and TGF-β1 in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose, downregulate CaN expression, and block the CaN/NFAT signaling pathway. However, the effect of NCTD on inhibition of the expression of ECM and TGF-β1 was not associated with its inhibition of the CaN/NFAT pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) has become one of the major causes of end-stage renal failure. For a long time, glomerulosclerosis was regarded as the main pathological lesion of DN. Recently, studies had reported that tubulointerstitial fibrosis could occur during the early stages of DN and directly trigger the deterioration of renal function independent of diabetic glomerulopathy.1, 2 However, clinical data have shown that active control of blood glucose and cholesterol levels, reduction in proteinuria by blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and amelioration of insulin resistance do not effectively inhibit tubulointerstitial fibrosis associated with DN.3 To date, there are no ideal agents that can reverse tubulointerstitial fibrosis and slow the decline in renal function in DN.

Norcantharidin (NCTD) is the demethylated analog of cantharidin and it also possesses anticancer activity and stimulates the bone marrow. However, the nephrotoxicity associated with NCTD treatment is absent.4 It has been confirmed in our previous studies that NCTD was capable of attenuating renal interstitial fibrosis in rat models with protein overload nephropathy,5 obstructive nephropathy (data not shown), and DN.6 Based on in vitro studies, we found that NCTD could block the transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)-mediated renal tubular epithelial cell transdifferentiation (data not shown). These findings suggest that NCTD may have antifibrotic properties. However, there is currently no thorough understanding of the molecular mechanism of how NCTD contributes to inhibition of tubulointerstitial fibrosis associated with DN.

NCTD was also reported to be an inhibitor of protein phosphatase.7 Baba et al8 found that NCTD could inhibit the activity of calcineurin (CaN). CaN is a calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase that participates in a number of cellular processes and Ca2+-dependent signal transduction pathways. Gooch et al9, 10, 11 demonstrated that CaN expression was increased in the diabetic kidney and played an important role in the progression of glomerulosclerosis in DN. In addition, inhibition of CaN by cyclosporine (CsA) could reduce glomerular hypertrophy and block extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation, such as fibronectin (FN), collagen IV (ColIV), and so on, in glomuruli. CaN is primarily expressed in the epithelial cells of proximal tubules,12, 13 which have a major role in tubulointerstitial fibrosis of DN. However, the role of CaN in tubulointerstitial fibrosis of DN is not clear.

Our previous study had found that NCTD could decrease the CaN expression in tubules of rat models with DN.6 The aim of the present study was to verify the effects of NCTD on high glucose-induced ECM and TGF-β1 in human kidney proximal tubular epithelial (HK-2) cells, confirm the role of NCTD in CaN pathway of tubular cells induced by high glucose, and determine whether the molecular mechanism by which NCTD inhibits renal interstitial fibrosis by high glucose correlates with blockade of CaN pathway in tubular epithelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The following materials were used: HK-2 cells (ATCC, USA); NCTD (Beijing Shuang He Biotechnological Limited Company, China); Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and Opti-MEM I medium (Gibco, USA); Trypsin and D-Glucose (Sigma, USA); fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hangzhou Si Jiqing Company, China); Lipofectamine 2000 and SYBR GreenER Qpcr SuperMix (Invitrogen, USA); Hoechest 33258 (Jing Mei Biotechnological Limited Company, China); Rabbit anti-human FN, TGF-β1, CaN, and NFATc polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA); Rabbit anti-human ColIV polyclonal antibody (Abcam, UK); RIPA Lysis buffer (Beijing Ding Guo Biotechnology, China); Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction kit (Bi Yuntian Biotechnology, China); RevertAidTM First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, USA); and ECL detection kits and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, USA).

Cell Culture

HK-2 cells were grown in six-well plates using low glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2 in air. Cell culture media was changed every 48 to 72 h. These cells were subcultured at 80% confluence using 0.05% trypsin with 0.02% EDTA. The experiment was then performed on cells following a 24-h incubation in DMEM medium without FBS.

Cytotoxicity Effect of NCTD on HK-2 Cells as Measured by the Trypan Blue Dye Exclusion Test

HK-2 cells were inoculated in 24-well culture plates with DMEM medium containing 30 mmol/l glucose and NCTD (0, 0.5, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 mg/l), using three wells for each concentration of NCTD and then with 10% FBS for another 24 h. At the end of the time period, cells were washed twice with PBS and trypsinized with 0.05% trypsin with 0.02% EDTA. Cell suspensions were centrifuged, and the supernatant was discarded. Single-cell suspension was prepared and then diluted to 1 × 106 cells/ml by mixing with 0.4% Trypan blue. The mixture was incubated for 3 min at room temperature and observed in a blood counting chamber. The unstained (viable) and stained (nonviable) cells were counted separately in five random visual fields. The percentages of viable cells were calculated as follows:

Effects of NCTD on HK-2 Cell Proliferation as Measured by the MTT Assay

HK-2 cells were diluted to 1 × 104 cells/ml by mixing with DMEM plus 10% FBS. The mixture was cultured in 96-well culture plates, with 100 μl in each well, at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere to a subfusion state and then synchronously cultured in DMEM serum-free medium for 24 h. Cells were further incubated in DMEM plus 10% FBS containing 30 mmol/l glucose with NCTD (0, 0.5, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40.0 mg/l) for 24, 48, and 72 h; three wells were used for each concentration of NCTD. After the experimental periods, 20 μl of methylthiazoletetrazolium (MTT; 5 mg/ml) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for another 4 h at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2 in air. The supernatant was then discarded and 150 μl of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well to dissolve blue formazan crystals; the optical density (OD) was measured with a microplate reader (SpectraMax 340, Molecular Devices, Japan) at a wavelength of 490 nm. The arithmetic mean of the OD of each group of wells was calculated, and the OD of the cells in normal glucose group was assigned a relative value of 100.

The Effects of NCTD on FN, ColIV, TGF-β1, and CaN mRNA Expression in HK-2 Cells as Measured by Real-Time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

HK-2 cells were divided into four groups: the NG group with cells cultured in DMEM containing normal glucose (5.5 mmol/l D-Glucose); the HG group with cells cultured in DMEM supplemented with high glucose (30 mmol/l D-Glucose); the M group with cells cultured in 30 mM D-mannose; and the HG plus NCTD group where cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 30 mmol/l D-Glucose after pretreatment with NCTD (5 mg/l) for 15 min.

The measurements of FN, ColIV, TGF-β1, and CaN mRNA expression affected by NCTD were assessed with real-time RT-PCR. SYBR Green, a fluorescent dye that binds only to double-stranded DNA, was used as the fluorescent probe system, and fluorescence was emitted proportionally to the amount of cDNA that was amplified by RT-PCR. PCR thermal cycling parameters consisted of one cycle of 2 min at 50 °C and 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 60 s at 60 °C, and 60 s at 72 °C, and one cycle of 10 min at 72 °C. Housekeeping gene β-actin served as the reference and was co-amplified with FN, ColIV, TGF-β1, and CaN. Controls consisting of water were chosen as negative control replacing template. The relative amount of target mRNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. All the oligonucleotide primers were designed by Shanghai Ying Jun Limited Company (Table 1).

Western Blot Analysis for the Effects of NCTD on FN, ColIV, TGF-β1, and CaN Protein Expression of HK-2 Cells

Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer and protease inhibitor PMSF at 4 °C. Lysate was collected and clarified by centrifugation of 12 000 r.p.m. for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were used for the experiments. Nuclear protein was extracted using a nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method. To denature the extracted protein and expose the domain that can be typically recognized by antibodies, a loading buffer with the anionic denaturing detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was used. The mixture was boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Protein was loaded on SDS polyacrylamide gel, electrophoresed, and transferred to a PVDF membrane using a transfer buffer (2.9 g glycine, 5.8 g Tris, 0.37 g SDS, and 200 ml methanol). The membrane was blocked by using 2% BSA to prevent nonspecific background binding of the antibody and incubated for 2 h at room temperature under agitation. Immunoblots were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies, including rabbit anti-human FN, ColIV, TGF-β, CaN, and NFATc (1:1000), respectively. After washing several times, the membranes were incubated under agitation for 1 h at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody IgG. Detection of specific protein bands was accomplished with chemiluminescence by using the ECL detection kits and recorded on radiograph film. Optimally exposed autoradiographs were digitally scanned and analyzed using Kodak high-sensitivity imaging systems. The intensity of the identified bands was quantified by densitometry. Results were normalized to β-actin and expressed as arbitrary densitometry units.

Indirect Immunofluorescence for the Effects of NCTD on Distribution of NFAT Protein in HK-2 Cells

Cells grown on coverslips were washed by PBS twice, fixed in 4% PBS for 20 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with Triton X-100/PBS for 10 min at room temperature; this was followed by quick rinsing in PBS (pH 7.4) three times at 5 min each time. After blocking in 5% BSA and 1% Triton X-100/PBS for 30 min at room temperature, cells were incubated with a 1:100 dilution of rabbit anti-human NFATc polyclonal antibody under agitation for 1 h at room temperature, and washed in PBS (pH 7.4) three times at 5 min each time. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with FITC-labeled secondary antibody directed against mouse IgG in a dilution of 1:100 for 30 min and with Hoechest 33258 200 μl for 15 min at room temperature. After rinsing by PBS three times at 10 min each time under agitation, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies in the absence of primary antibody to demonstrate background staining. Slides were mounted and viewed using a fluorescent microscope.

CaN Small Interference RNA (siRNA) Transfected to HK-2 Cells

Synthetic double-strand siRNA targets the CaN coding region. Its sequence was as follows: CaN siRNA sense 5′-CCAUACUGGCUUCCAAAUUTT-3′ and CaN siRNA antisense 5′-AAUUUGGAAGCCAGUAUGGTT-3′. Cells were transfected with green fluorescent-labeled siRNA in Opti-MEM I Reduced-Serum Medium using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufactures’ instructions. CaN siRNA oligomer 24 μg was diluted in 250 μl of Opti-MEM I Reduced-Serum Medium without serum and mixed gently. Lipofectamine 2000 24 μl was diluted in 250 μl Opti-MEM I Reduced-Serum Medium, mixed gently, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. After 5-min incubation, the diluted oligomer and Lipofectamine 2000 were combined, mixed gently, and incubated for 20 min at room temperature to allow for complex formation. The oligomer−Lipofectamine 2000 complex was added to each well containing cells and medium and was mixed gently by rocking the plate back and forth. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator for 5 h, after which the cells were cultured in complete medium for 24 h.

The HK-2 cells were then divided into five groups: NG, HG, HG plus CaN siRNA, HG plus CaN siRNA plus NCTD, and HG plus NCTD. In the HG plus CaN siRNA group, HK-2 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with high glucose 24 h after transfection with green fluorescent-labeled CaN siRNA. In the HG plus CaN siRNA plus NCTD group, HK-2 cells were pretreated with NCTD (5 mg/l) for 15 min after transfection with green fluorescent-labeled CaN for 24 h, followed by culture in DMEM supplemented with 30 mmol/l D-Glucose.

Statistical Methods

Data are expressed as means±s.d. Groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's test. All analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). All P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Cytotoxic Effects of NCTD on HK-2 Cells Stimulated by High Glucose

A Trypan blue dye exclusion test revealed that after NCTD intervention, HK-2 cell mortality was <5% when NCTD concentration was ≤5 mg/l, whereas overt cytotoxicity was detected when NCTD concentration was >5 mg/l (Figure 1).

Effects of NCTD on the Proliferation of HK-2 Cells Stimulated by High Glucose

An MTT assay revealed that the OD of HK-2 cells in the HG group was higher than that of the NG group (P<0.05) after 48 and 72 h; however, a gradual dose-dependent decrease in OD was seen after the NCTD intervention. The OD of HK-2 cells in HG with 2.5 or 5 mg/l of NCTD was lower than that in HG without NCTD treatment (P<0.05), which indicated that 2.5 and 5 mg/l of NCTD could inhibit the proliferation of HK-2 cell induced by high glucose (P<0.05). Inhibition was stronger with 5 mg/l of NCTD. Meanwhile, the effect of other concentrations of NCTD on cell proliferation stimulated by HG for 24 h was not significant (Figure 2).

Effects of NCTD on cell proliferation stimulated by high glucose detected by MTT assay. It indicated that 2.5 and 5 mg/l NCTD could inhibit high-glucose-induced HK-2 cell proliferation, and inhibition was stronger with 5 mg/l NCTD. *P<0.05 compared with control group, #P<0.05 compared with NCTD-untreated group.

Based on the results of the Trypan blue dye exclusion test and the MTT assay, we chose 2.5 and/or 5 mg/l of NCTD as the experimental concentration for our later research in this study.

Effects of NCTD on FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 mRNA Expression in HK-2 Cells Stimulated by High Glucose

Compared with the NG group, upregulation of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 mRNA expression was detected at 6 h after HG stimulation, and it continued for 24 h and peaked at 48 h (P<0.05). However, compared with the HG group, downregulation of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 mRNA expression was observed 6 h after 5 mg/l NCTD intervention and persisted for 48 h (P<0.05). Meanwhile, real-time RT-PCR revealed that there was a nonsignificant difference in TGF-β1 expression between the NG and HG stimulation groups at 6 h (P>0.05). However, upregulation was detected 24 and 48 h later with HG stimulation (P<0.05). Compared with the HG group, distinct downregulation of TGF-β1 mRNA expression was first observed 24 h after 5 mg/l NCTD intervention and persisted until 48 h later (P<0.05; Figure 3).

Effect of NCTD on the expression of ECM and TGF-β1mRNA in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose. (a) Real-time PCR showed that NCTD downregulated FN mRNA expression. (b) Real-time PCR showed that NCTD downregulated ColIV mRNA expression. (c) Real-time PCR showed that NCTD downregulated TGF-β1 mRNA expression. The relative FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1mRNA expression levels according to cycle threshold (Ct) value in different groups. *P<0.05 compared with the C and M groups. #P<0.05 compared with the HG group at 6, 24, and 48 h. C, NG (5.5 mM D-glucose) group; HG, 30 mM D-glucose group; M, 30 mM D-mannose group; HG+NCTD, 30 mM D-glucose plus 5 mg/l NCTD group.

The above results indicated that HG could specifically increase FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 mRNA expression, whereas NCTD could inhibit its upregulation.

Effects of NCTD on FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 Protein Expression in HK-2 Cells Stimulated by High Glucose

Western blot testing revealed that FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 protein expression of HK2 cells with HG stimulation was insignificant when compared with that in the NG group at 6 h (P>0.05). However, evident upregulation was detected 24 and 48 h later with HG stimulation (P<0.05). When compared with the HG group, downregulation of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 protein expression was observed at 24 h after 5 mg/l NCTD intervention and persisted for 48 h (P<0.05; Figure 4).

Effect of NCTD on the expression of ECM and TGF-β1 protein in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose. (a) Western blot showed that NCTD downregulated FN protein expression. (b) Western blot showed that NCTD downregulated ColIV protein expression. (c) Western blot showed that NCTD downregulated TGF-β1 protein expression. The relative FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 protein expression levels according to protein gray value in different groups. *P<0.05 compared with the C group; #P<0.05 compared with the HG group at 6, 24, and 48 h. C, NG (5.5 mM D-glucose) group; HG, 30 mM D-glucose group; HG+NCTD, 30 mM D-glucose plus 5 mg/l NCTD group.

Effects of NCTD on CaN mRNA and Protein Expression of HK-2 Cells Stimulated by High Glucose

Real-time RT-PCR and western blot analyses revealed that 24 h after high glucose exposure, CaN mRNA and protein levels were significantly upregulated compared with the control group (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively). Treatment with NCTD downregulated the expression of CaN mRNA and protein (P<0.05) in a dose-dependent manner. A high concentration of NCTD was more effective (Figure 5).

Effect of NCTD on CaN mRNA and protein expression in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose. (a) Real-time PCR showed that NCTD inhibited CaN mRNA expression in HK-2 cells; (b) western blot showed that NCTD inhibited CaN protein expression in HK-2 cells. *P<0.05 compared with the C group; #P<0.05 compared with the HG group. C, 5.5 mM D-glucose; HG, 30 mM D-glucose; NCTD2.5, 30 mM D-glucose plus 2.5 mg/l NCTD; NCTD5, 30 mM D-glucose plus 5 mg/l NCTD.

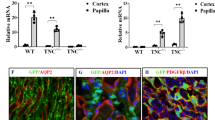

Effects of NCTD on CaN/NFATc Signaling Pathway in HK-2 Cells Stimulated by High Glucose

Indirect immunofluorescence revealed that the NFATc deposition was mainly found in the cytoplasm of HK-2 cells in the NG group. However, it was markedly decreased in the cytoplasm of the HG group and was found mainly in nucleus, where it peaked at 30 min, suggesting translocation of NFATc to the nucleus. NCTD treatment significantly attenuated the increased expression of NFATc in the nucleus. This observation may indicate that NCTD inhibits the nuclear translocation of NFATc from cytoplasm to the nucleus, induced by high glucose. Nuclear protein was extracted and normalized to histone H. Consistent with the indirect immunofluorescence studies, western blot analysis revealed an increased NFATc expression in the nucleus of the HG group compared with that in the NG group. In contrast, NCTD treatment significantly inhibited the upregulation of NFATc nuclear deposition and the downregulation of NFATc cytoplasmic deposition (Figure 6).

Effects of NCTD on NFATc nuclear translocation and protein expression in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose. (a) Immunofluorescence staining indicated that NCTD inhibited the nuclear translocation of NFATc from cytoplasm to the nucleus ( × 800). The blue-colored stain is nuclear counterstained with Hoechest 33258. (b) Western blot showed that NCTD decreased the upregulation of NFATc nuclear deposition. C, 5.5 mM D-glucose; HG, 30 mM D-glucose; HG+NCTD, 30 mM D-glucose plus 5 mg/l NCTD.

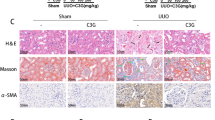

Effects of CaN siRNA on CaN mRNA and Protein Expression of HK-2 Cells Stimulated by High Glucose

Green fluorescent-labeled CaN siRNA was used to assess the transfection efficiency. Samples were mounted and visualized under an inverted microscope. More than 70% of cells contained intracellular fluorescence, suggesting successful introduction of siRNA into HK-2 cells. CaN mRNA and protein expression was significantly decreased in CaN siRNA-transfected cells, suggesting that transfected CaN siRNA efficiently inhibited the expression of CaN (Figure 7).

Effects of CaN siRNA on CaN mRNA and protein expression in HK-2 cells. (a) Track of fluorescent-labeled CaN siRNA was transfected into HK-2 cells. (A) At 24 h following transfection, HK-2 cells were fixed and visualized by optical microscopy. (B) Fluorescence microscopy. (b) Real-time PCR showed that CaN mRNA expression decreased following CaN siRNA transfected into HK-2 cells. *P<0.05 vs control group. (c) Western blot showed that CaN protein expression decreased following CaN siRNA transfected into HK-2 cells. *P<0.05 compared with control group.

Effects of NCTD on FN, ColIV, and TGF-β Protein Expression in CaN siRNA-Transfected HK-2 Cells

Elevated CaN protein expression stimulated by high glucose was significantly decreased in CaN siRNA-transfected cells, and was further reduced with NCTD treatment. Application of NCTD alone significantly reduced FN, ColIV, and TGF-β protein expression when compared with the control group. In contrast, protein levels of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β were increased in CaN siRNA-transfected cells and was downregulated by treatment with NCTD (Figure 8).

Effects of NCTD on ECM and TGF-β protein expression in CaN siRNA-transfected HK-2 cells. (a) Western blot showed that NCTD alone significantly reduced FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 protein expression. However, their protein levels were increased in CaN siRNA-transfected cells and downregulated by treatment with NCTD. (b) Relative ratios of expression intensities of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 to that of β-actin in HK-2 cells stimulated with high glucose. *P<0.05 compared with control group; #P<0.05 compared with the HG group 2; ΔP<0.05 compared with CaN siRNA-transfected HK-2 cells.

DISCUSSION

NCTD, a synthesized demethylated form of cantharidin and an active ingredient of the Chinese medicine Mylabris, is now in wide use as a routing anticancer drug against digestive tract cancer.14, 15 With few side effects, NCTD is also regarded as an attractive potential therapeutic agent in cancer chemotherapy in Western countries.4 It has been demonstrated that the mechanisms by which NCTD inhibits the growth of malignant cells correlate with the blockade of DNA synthesis, arrest of the cell cycle, and induction of P53- and Bcl-2-dependent apoptotic pathways. Mitochondrial-dependent caspase activation cascade induced by NCTD is also thought to be responsible for the regulation of cell apoptosis.16, 17 In our previous study, we reported that NCTD attenuated renal interstitial fibrosis in rat models with protein overload nephropathy,5 obstructive nephropathy (data not shown), and DN.6 Furthermore, we demonstrated the in vitro inhibition by NCTD of phosphorylation of Smad2/Smad3 induced by TGF-β and blockade of TGF/Smad pathway-mediated epithelial−mesenchymal transition (EMT) in HK-2 cells (data not shown). Therefore, we suggest that NCTD may be a prospective drug for inhibiting tubulointerstitial fibrosis in DN. However, the underlying mechanism of action remains unclear.

Overexpression of the ECM components (FN and ColIV) and TGF-β1 has been previously implicated in the development of the renal fibrosis of DN.18 FN, the first dimeric glycoprotein found in ECM with a molecular weight of 550 kD, contains five spherical functional domains that can bind heparin, collagen, and cell surface receptors. Because of its binding capacity, FN links ECM with the intracellular cytoskeleton and provides trestle structure for other ECM components. FN has become an important signal of ECM accumulation or even kidney sclerosis. ColIV, the most abundant matrix protein in the tubular basement membrane under physiological conditions, consists of six genetically distinct polypeptide chains (α1−α6) with a molecular weight of 180 kDa each. Collagen metabolism disorders play an important role in the pathogenesis of DN.19 TGF-β1 is considered an important etiologic factor in interstitial fibrosis by increasing the production of ECM. In addition, its upregulation is a common characteristic of renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in DN.20 In this study, we first found that the mRNA and protein expression of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 was upregulated with HG stimulation, whereas NCTD could evidently inhibit their upregulation in a time-dependent manner. Because TGF-β1 can increase ECM protein synthesis, including ColIV and FN, we suggested that NCTD might downregulate FN and ColIV expression in HK-2 cells induced by HG through inhibition of TGF-β1 expression. The results of this in vitro study further suggest that NCTD has an anti-tubulointerstitial fibrosis effect on DN. The potential pharmacological mechanism calls for further investigation to determine the therapeutic targets of NCTD for DN.

Many studies have reported that NCTD exhibits a remarkable inhibitory effect on protein phosphatases, including PP2B, PP1, and PP2A.8, 21, 22 PP2B, also known as CaN, is the only Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent Ser/Thr protein phosphatase ubiquitously expressed and is highly conserved in eukaryotes. CaN consists of two subunits: the enzymatic subunit A (CaN A) and the regulatory subunit B (CaN B).23 Binding of Ca2+ to the CaN B causes a change in CaN A conformation and subsequently unmasks its active site, leading to the activation of CaN A, followed by the removal of the phosphate group from its downstream substrate. Importantly, the critical target of CaN is the nuclear factor-activated T-cell (NFAT) family of transcription factors. Dephosphorylated NFAT protein translocates from the cytoplasma to the nucleus, where it regulates gene transcription through synergistic interaction with other transcription factors.24, 25

It has been reported that in the early stage of diabetes, CaN protein is increased in the whole cortex and glomeruli in conjunction with increased phosphatase activity.9 The CaN/NFATc pathway was thought to play an important role in TGF-β-mediated induction of glomerular hypertrophy and FN expression, which is in agreement with other literature reporting that administration of CaN inhibitor CsA blocked accumulation of both CaN protein and CaN activity and substantially reduced ECM accumulation and hypertrophy in diabetic glomeruli.10, 11 We have found that NCTD can alleviate the expression of CaN in tubules in DN.6 However, CaN is primarily expressed in the epithelium of proximal tubules.12, 13 Several studies have demonstrated that induction of CaN phosphatase activity coincides with increased CaN protein levels. In other words, increased protein levels may be a reliable indicator of phosphatase activity.11, 13 Therefore, we only examined the expression of CaN protein in HK-2 cells. According to our study, we found that NCTD treatment inhibited the increased CaN expression in HK-2 cells stimulated by high glucose. Subsequently, we further found that NCTD significantly blocked nuclear localization of the downstream substrate NFATc induced by high glucose, suggesting an inhibitory effect of NCTD on CaN/NFATc pathway in tubular cells. However, whether the antifibrotic effect of NCTD is associated with inhibition of the CaN pathway remains to be further elucidated.

Then, our experiments were performed using CaN targeting siRNA (a targeting catalytic subunit of CaN Aα isoform) to knock down CaN in mRNA and protein levels. Extracellular derangements in the tubulointerstitial compartment were observed, including elevated expression of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1. This observation suggests that inhibition of CaN by RNA interference had a profibrotic effect. We also showed that NCTD inhibited the elevated FN, ColIV, and TGF-β1 protein expression in CaN siRNA-transfected HK-2 cells. These findings demonstrate that the antifibrosis effect of NCTD was independent of the CaN pathway.

Interestingly, many studies confirmed that long-term treatment with CaN inhibitors (such as CsA, a widely used immunosuppressant in clinical medicine), caused irreversible and progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis, which was the main side effect of this regimen. Similar to the CaN inhibitors, the opposite roles that NCTD and CsA have on renal fibrosis can be explained from the following three aspects.

-

1)

It has been identified that CaNA has three main isoforms, including CaNA-α, CaNA-β, and CaNA-γ. CaNA-α and CaNA-β were detected to be differentially expressed in the kidney. CaNA-α was the predominant isoform expressed in the proximal tubules and was associated with ECM synthesis and TGF-β expression,26, 27 whereas the β-isoform was expressed mostly in glomeruli. Gooch et al26 found that rats lacking α-isoform displayed renal developmental defects or fibrosis, which coincided with the side effects of CsA. Baba et al8 reported that CsA inhibited PP2B with an IC50 value of 0.75 μM; in comparison, the IC50 value of NCTD was 500 μM. Therefore, a conclusion could be drawn from this work that the different roles of NCTD and CsA in tubulointerstitial fibrosis might be dependent on the degree of inhibition. Minor inhibition plays a protective role, whereas overinhibition or CaNA-α knockout produces a stimulative effect on tubulointerstitial fibrosis.

-

2)

Akool et al28 demonstrated that CsA-induced renal interstitial fibrosis attributed to the activation of TGF-β/Smad pathway triggered by reactive oxygen species exaggerated the deposition of ECM because of an increased expression of TGF-β1. Therefore, antioxidant treatment was considered a valuable approach for the prevention of calcineurin inhibitor-induced renal fibrosis. Nevertheless, it is unknown if NCTD exerts an antifibrosis effect through blockade of oxidative stress.

-

3)

It has been reported that NCTD inhibited not only PP2B but also PP1 and PP2A.8, 22 CsA, however, forms complexes with immunophilins that exert their selective inhibitory action on PP2B. PP1, PP2A, and PP2B all belong to the PPP family of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases and participate in regulating many important physiological processes, such as glycogen metabolism, cell apoptosis, and gene transcription. Our present study showed that the antifibrotic effect of NCTD is not correlated with its role of PP2B inhibition. Further studies are needed to determine whether NCTD exerts a protective effect through its actions on PP1 or PP2A. However, the inhibition degree of NCTD is more to PP2A than to PP1 (IC50=2.69 μM vs 10.3 μM).29 Hence, we think that NCTD plays an antifibrotic role by mainly inhibiting PP2A.

In summary, NCTD could ameliorate tubulointerstitial fibrosis in DN through inhibition of the expression of ECM and TGF-β1 of tubules. It could also block the CaN/NFAT signaling pathway. However, protein levels of FN, ColIV, and TGF-β increased in CaN siRNA-transfected HK-2 cells, which were downregulated by further NCTD treatment. Results from the present study indicate that the antifibrogenic effect of NCTD on tubular interstitium in DN was independent of CaN/NFAT pathway inhibition. A better understanding of the molecular mechanism of NCTD on tubulointerstitial fibrosis may aid in the development of new pharmacologic agents for DN.

References

Bagby SP . Diabetic nephropathy and proximal tubule ROS: challenging our glomerulocentricity. Kidney Int 2007;71:1199–1202.

Singh DK, Winocour P, Farrington K . Mechanisms of disease: the hypoxic tubular hypothesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2008;4:216–226.

Balakumar P, Arora MK, Ganti SS, et al. Recent advances in pharmacotherapy for diabetic nephropathy: current perspectives and future directions. Pharmacol Res 2009;60:24–32.

Massicot F, Dutertre-Catella H, Pham-Huy C, et al. In vitro assessment of renal toxicity and inflammatory events of two protein phosphatase inhibitors cantharidin and nor-cantharidin. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2005;96:26–32.

Liu FY, LI Y, Peng YM, et al. Norcantharidin ameliorates proteinuria, associated tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis in protein overload nephropathy. Am J Nephrol 2008;28:465–477.

Li Y, Chen Q, Liu FY, et al. Norcantharidin attenuates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in rat models with diabetic nephropathy. Ren Fail 2011;33:233–241.

Bertini I, Calderone V, Fragai M, et al. Structural basis of serine/threonine phosphatase inhibition by the archetypal small molecules cantharidin and norcantharidin. J Med Chem 2009;52:4838–4843.

Baba Y, Hirukawa N, Tanohira N, et al. Structure-based design of a highly selective catalytic site-directed inhibitor of Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin). J Am Chem Soc 2003;125:9740–9749.

Gooch JL, Barnes JL, Garcia S, et al. Calcineurin is activated in diabetes and is required for glomerular hypertrophy and ECM accumulation. Am J Physiol Renal 2003;284:144–154.

Gooch JL, Gorin Y, Zhang BX, et al. Involvement of calcineurin in transforming growth factor-β mediated regulation of extracellular matrix accumulation. J Biol Chem 2004;279:15561–15570.

Gooch JL . An emerging role for calcineurin A in the development and function of the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006;290:F769–F776.

Tumlin JA, Someren JT, Swanson CE, et al. Expression of calcineurin activity and -subunit isoforms in specific segments of the rat nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 1995;269:F558–F563.

Tumlin JA . Expression and function of calcineurin in the mammalian nephron: physiological roles, receptor signaling and ion transport. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30:884–895.

Huang Y, Liu Q, Liu K, et al. Suppression of growth of highly-metastatic human breast cancer cells by norcantharidin and its mechanisms of action. Cytotechnology 2009;59:201–208.

Hill TA, Stewart SG, Ackland SP, et al. Norcantharimides, synthesis and anticancer activity: synthesis of new norcantharidin analogues and their anticancer evaluation. Bioorg Med Chem 2007;15:6126–6134.

Chen YN, Chen JC, Yin SC, et al. Effector mechanisms of norcantharidin-induced mitotic arrest and apoptosis in human hepatoma cells. Int J Cancer 2002;100:158–165.

Kok SH, Cheng SJ, Hong CY, et al. Norcantharidin-induced apoptosis in oral cancer cells is associated with an increase of proapoptotic to antiapoptotic protein ratio. Cancer Lett 2005;217:43–52.

Kanwar YS, Wada J, Sun L, et al. Diabetic nephropathy: mechanisms of renal disease progression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:4–11.

Park J, Ryu DR, Li JJ, et al. MCP-1/CCR2 system is involved in high glucose-induced fibronectin and type IV collagen expression in cultured mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008;295:F749–F757.

Hills CE, Squires PE . TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and therapeutic intervention in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Nephrol 2010;31:68–74.

Baba Y, Hirukawa N, Sodeoka M . Optically active cantharidin analogues possessing selective inhibitory activity on Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin): implications for the binding mode. Bioorg Med Chem 2005;13:5164–5170.

Hill TA, Stewart SG, Gordon CP, et al. Norcantharidin analogues: synthesis, anticancer activity and protein phosphatase 1 and 2A inhibition. Chem Med Chem 2008;3:1878–1892.

Fraga D, Sehring IM, Kissmehl R, et al. Protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B, calcineurin) in Paramecium: partial characterization reveals that two members of the unusually large catalytic subunit family have distinct roles in calcium-dependent processes. Eukaryot Cell 2010;9:1049–1063.

Panther F, Williams T, Ritter O . Inhibition of the calcineurin-NFAT signalling cascade in the treatment of heart failure. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov 2009;4:180–186.

Rinne A, Banach K, Blatter LA . Regulation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) in vascular endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2009;47:400–410.

Gooch JL, Roberts BR, Cobbs SL, et al. Loss of the alpha-isoform of calcineurin is sufficient to induce nephrotoxicity and altered expression of transforming growth factor-beta. Transplantation 2007;83:439–447.

Reddy RN, Knotts TL, Roberts BR, et al. Calcineurin A-beta is required for hypertrophy but not matrix expansion in the diabetic kidney. J Cell Mol Med 2011;15:414–422.

Akool el-S, Doller A, Babelova A, et al. Molecular mechanisms of TGF-β receptor-triggered signaling cascades rapidly induced by the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporin A and FK506. J Immunol 2008;181:2831–2845.

Stewart SG, Hill TA, Gilbert J, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of norcantharidin analogues: towards PP1 selectivity. Bioorg Med Chem 2007;15:7301–7310.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (Grant No. 20070533062), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. 10JJ2011), and the scientific project of Research Center of Metabolic Syndrome in Central South University of China (Grant No. DY-2008-02-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Norcantharidin, an inhibitor of calcineurin, attenuates renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in rat models of diabetic nephropathy through inhibition of the expression of extracellular matrix and of TGF-β1 in tubules. However, the anti-fibrogenic effect of norcantharidin on tubular interstitium is independent of the calcineurin signaling pathway, so the mechanism is not known.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Chen, Q., Liu, FY. et al. Norcantharidin inhibits the expression of extracellular matrix and TGF-β1 in HK-2 cells induced by high glucose independent of calcineurin signal pathway. Lab Invest 91, 1706–1716 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2011.119

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2011.119

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mechanisms of norcantharidin against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis

Pharmacological Reports (2024)

-

Protein Phosphatase 2A Inhibiting β-Catenin Phosphorylation Contributes Critically to the Anti-renal Interstitial Fibrotic Effect of Norcantharidin

Inflammation (2020)

-

Norcantharidin, a protective therapeutic agent in renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2012)