Abstract

Targeted ablation of Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) in the mouse epidermis results in severe abnormalities in dermal vasculature reminiscent of petechia induced in human skin by anticoagulants or certain genetic disorders. Lack of Arnt leads to downregulation of Egln3/Phd3 hydroxylase and concomitant hypoxia-independent stabilization of hypoxia-induced factor 1α (Hif1α) along with compensatory induction of Arnt2. Ectopic induction of Arnt2 results in its heterodimerization with stabilized Hif1α and is associated with activation of genes coding for secreted proteins implicated in control of angiogenesis, coagulation, vasodilation and blood vessel permeability such as S100a8/S100a9, S100a10, Serpine1, Defb3, Socs3, Cxcl1 and Thbd. Since ARNT and ARNT2 heterodimers with HIF1α are known to have different (yet overlapping) downstream targets our findings suggest that loss of Arnt in the epidermis activates an aberrant paracrine regulatory pathway responsible for dermal vascular phenotype in K14-Arnt KO mice. This assumption is supported by a significant decline of von Willebrand factor in dermal vasculature of these mice where Arnt level remains normal. Given the essential role of ARNT in the adaptive response to environmental stress and striking similarity between skin vascular phenotype in K14-Arnt KO mice and specific vascular features of tumour stroma and psoriatic skin, we believe that further characterization of Arnt-dependent epidermal–dermal signalling may provide insight into the role of macro- and micro-environmental factors in control of skin vasculature and in pathogenesis of environmentally modulated skin disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Modulation of dermal vasculature is essential for mammalian adaptation to environmental stress and for pivotal aspects of skin physiology, such as thermoregulation, wound healing, hair and tumour growth, inflammation and immunity. Defects of blood vessel permeability and their abnormal growth are characteristic of a number of human skin disorders and pathological conditions including psoriasis, rosacea, sun burns, benign and malignant tumours, pressure ulcers, hair loss, diabetic skin changes, etc.1, 2, 3, 4 Specific alterations in dermal vasculature are also characteristic for aging skin.5, 6

The last decade provided a considerable insight into mechanisms that control skin angiogenesis driven by local (intratissuenal) hypoxia and by humoral factors.3, 7, 8 But dermal vasculature is also responsive to external stressors such as UV light or changing oxygen tension9, 10 with an obvious, yet poorly defined, role of the epidermis as an interface in these communications. Given that keratinocyte-conditioned culture medium stimulates angiogenesis, it was proposed that epidermis-derived factors can modulate dermal vascular growth in vivo.11 The role of epidermal signalling in control of dermal vasculature was later substantiated by the studies of VEGF secretion by psoriatic epidermis in humans12, 13 and in mouse models overexpressing Vegf and hypoxia-induced factor 1α (Hif1α).14, 15 Recently, it was shown that epidermal HIF1 activity has a central role in systemic adaptation to environmental oxygen levels by shunting the blood away from the dermis and redirecting it toward internal organs.10 This suggests that epidermal keratinocytes are able to sense the ambient oxygen and transmit the relevant signals down to dermal vasculature. Nevertheless, the nature of this signalling pathway remains unclear with available data limited to the role of epidermis-secreted VEGF in promotion of dermal angiogenesis. The role of the epidermis in modulating other aspects of dermal vascular physiology such as clotting, vasodilatation, permeability and maintenance of vessel wall integrity is still unknown.

HIF1, the key transcriptional regulator of hypoxia response and vascular homeostasis, represents a heterodimer of two PAS proteins–HIF1α and Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT or HIF1β). Under normoxic conditions, Hif1α is hydroxylated (with oxygen as a co-substrate) on two key proline residues in its oxygen-dependent degradation domain by specific prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) encoded by EGLN genes. This allows recognition of HIF1α by the von Hippel–Lindau tumour-suppressor protein (pVHL) and its subsequent rapid degradation by a pVHL-mediated ubiquitin–proteasome pathway.16, 17 In hypoxic tissues including growing tumours and healing wounds, EGLN-driven hydroxylation of HIF1α is compromised thus eventually leading to its stabilization, translocation to the nucleus and dimerization with ARNT.17, 18 The resulting HIF1 complex transactivates various glycolytic enzymes, VEGF, PDGF, FGF, nitric oxide synthase, haeme oxygenase, tyrosine hydroxylase and some other genes by binding to the consensus sequence 5′-ACGTGCT-3′ (hypoxia response element or HRE) in their promoters.19 Thus, the HIF1α/ARNT heterodimer represents a global regulator of hypoxia gene expression and controls major aspects of adaptive response to hypoxia, such as anaerobic metabolism, erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, vasodilatation and breathing.19, 20, 21, 22

The conventional concept of the hypoxic response is based on the assumption that HIF1α, as an oxygen-regulated subunit, determines the overall activity of the HIF1 heterodimer while Arnt represents a constitutively stable, ubiquitously expressed subunit.23 However, this view is gradually shifting towards greater appreciation of the regulatory role of ARNT in transcriptional control.24 Our previous studies have shown that in both mouse and human skin, patterns of ARNT expression are subject to significant spatial, developmental and adaptive changes25, 26 suggesting that local variations in Arnt level may have a significant role in the control of transcriptional activity in the epidermis. Yet, the functions of ARNT in the skin including its potential role in epidermal communication with dermal vasculature remain largely unknown.

Here, we show that targeted K14-driven ablation of Arnt in the mouse epidermis results in massive and chaotic growth of malformed and leaky dermal blood vessels bearing many features of tumour-associated stromal vasculature and leading to intradermal haemorrhage. Our results further highlight the role of the epidermis in maintenance of dermal vasculature and outline molecular components of a novel ARNT-dependent paracrine signalling pathway linking together epidermal HIF activity and dermal vascular homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, Tissue Collection and Immunohistochemistry

The generation of Arntflox/floxK14-Cre+ (ArntΔ/Δ) mice was described previously.25 Genotyping for K14-Cre+ and Arntflox/flox alleles was performed according to existing protocols.27, 28 Normal C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA).

Genetically altered and control (wild type) newborn mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation immediately after birth. Skin samples were embedded in Tissue-Tek medium (MILES; Elkhart, IN, USA) and frozen at −80 °C, or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin. Alternatively, skin samples were processed for mRNA/protein isolation or establishment of primary mouse keratinocyte (PMK) cell culture. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines issued by the IACUC of Columbia University.

For immunofluorescence, cold acetone-fixed (5 min) 8 μm-thick cryostat sections were pre-soaked in TBS buffer and blocked with 10% normal goat or donkey serum (DAKO; Carpinteria, CA, USA) depending on the origin of secondary antibodies. After the overnight incubation (RT) with primary antibodies (Supplementary Table S1), the sections were exposed to fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies, counterstained (if necessary) with Hoechst 33342 dye (10 μg/ml) (Sigma; St Louis, MO, USA) and mounted with Vectashield H-1000 (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA, USA). For double immunofluorescence, the sections were successively incubated with two primary antibodies originating from different host species followed by treatment with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorophores emitting at different wave-lengths. For ABC (avidin–biotin complex) immunohistochemistry, frozen sections were pre-treated with MeOH/H2O2 in order to block endogenous peroxidase, incubated with primary and secondary antibodies as described above and processed for signal detection using ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) along with haematoxylin counterstaining. Paraffin sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized in xylene and gradual alcohols and boiled in a microwave for 10 min in antigen unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories) for antigen retrieving. Their further processing was performed as described above. Incubation of skin sections without secondary antibodies was used as a negative control. Photo-documentation was performed using Zeiss Axioscope 2 microscope and the Axiovision image analysis system (Zeiss; Thornwood, NJ, USA).

Keratinocyte Culture

PMKs were isolated from the skin of previously genotyped 2-day old mouse female newborns as previously described.25 After filtration and centrifugation at 200 g for 5 min, keratinocytes were re-suspended in low Ca2+ (0.05 mM) keratinocyte SFM (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with EGF (5 ng/ml), BPE (50 μg/ml) and 100μg/ml gentamicin, plated in 60-mm collagen-coated dishes at 5 × 104 cells per cm2 and cultured in a humidified incubator at 32 °C and 5.0% CO2. After 24 h, keratinocytes were washed with fresh medium to remove unattached cells. To induce differentiation, the cells were switched to the medium containing 1.2 mM Ca2+. At 80% confluence, the cells were released with 0.05% trypsin and processed for further analysis.

Immunocytochemistry

PMKs were plated onto two-well Permanox microchamber slides at 5 × 104 cells per cm2 in a low Ca2+ (0.05 mM) KC-SFM and allowed to proliferate in a humidified incubator at 32 °C and 5.0% CO2. At 80% confluency, cells were fed with medium containing 1.2 mM Ca2+. After 24 h, cells were harvested, fixed with acetone for 2 min at −20 °C, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton for 5 min and blocked for 30 min with 0.3% BSA in PBS. Cells were washed 3 × 5 min with PBS and then processed for immunofluorescence as described above using primary Hif1α-specific and secondary Alexa 594 goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Supplementary Table S1). Cells were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen).

The proportion of keratinocytes with exclusively cytoplasmic or nuclear Hif1α localization (immunofluorescence) was estimated in control and Arnt-null cell cultures based on three independent assessments of corresponding slides using a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope.

Protein Isolation (Nuclear and Cytosolic Fractions) and Western Blotting

For western blotting (WB), protein cell lysates obtained from mouse epidermis (newborns) as described earlier25 were collected in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing 1 mM NaVO3, 1 mM DTT, 1 × protease inhibitor and 1 mM PMSF. Samples were passed through an 18G needle, and spun at 10 000 r.p.m., 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was removed and stored at −80 °C until further use. The pellet was washed twice in detergent-free buffer (as above) and dissolved in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 25% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 200 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF and 1 mM Na3VO4. The solution was incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged for 20 min at 15 000 r.p.m. The supernatant (nuclear fraction) was stored until analysis at −80 °C. Protein concentration was estimated using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories; Richmond, CA, USA).

Equal amounts of protein (20–50 μg) were added to Laemmli sample buffer (5% SDS, 25% glycerol, 125 mM Tris, few grains of bromophenol blue, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0) and subjected to electrophoresis using an Invitrogen Novex mini-cell system with NuPage pre-cast 4–12% gradient gels (NP0323; Invitrogen). Following transfer to nitrocellulose, samples were subjected to protein immunoblotting with primary antibodies at appropriate dilutions (Supplementary Table S1). Blots were analysed using the Versadoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA).

RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Newborn mouse epidermis and dermis were harvested as described earlier.25 Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed for 50 min at 50 °C using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) in the presence of oligo dT primer. In all, 1 μg of total RNA was converted into cDNA in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. RT-PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems 7300 Fast Real-Time PCR System with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, CA, USA) and primers (Supplementary Table S2) designed using Primer-3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/). The PCR reaction with alternating 15 s at 95 °C and 60 s at 60 °C lasted 40 cycles. The ABI sequence detection software (version 1.6.3) and Microsoft Excel were used to quantify cDNA content in the samples. The data were normalized to β-actin expressed as a housekeeping gene.

GeneChip Microarray

To identify genes responsive to Arnt deficiency, we compared gene expression profiles in the epidermis of Arnt-null and control mice. For that, six replicates for each condition were used and each of the 12 probes was obtained by pooling together RNA isolated from the epidermis of two mouse female newborns. RNA samples were stored in RNAlater-ICE frozen tissue transition solution (Ambion; Austin, TX, USA) at −80 °C until further use. Isolation of total RNA, probe preparation, labelling and characterization were performed with strict conformity with Affymetrix protocols. For hybridization we used GeneChip Mouse Genome 430A 2.0 Array (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA, USA) containing approximately 14 000 well-characterized mouse genes. The genes differentially expressed between control and Arnt-null mouse epidermis were detected using t-statistics followed by F-test implemented in Bioconductor R package multtest. The differentially expressed genes were considered to have adjusted P-value below 0.01 and the log2 expression ratios outside the −1 to 1 interval. For validation of chip experiments, we used quantitative RT-PCR analysis. A list of differentially expressed genes related to blood vessel growth/clotting control is provided in Table 1 (downregulation) and Table 2 (upregulation). The full list of genes differentially expressed in Arnt-null mouse epidermis was published previously.25

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Assay

Co-IP was performed as described previously29 with some modifications. In short, Arnt-null and Arntflox/floxK14Cre– (control) mouse epidermal keratinocytes at 60–80% confluency were treated with 200 μM of hypoxia-mimetic CoCl2 for 4 h at 37 °C in order to promote Hif1α stabilization. After cell harvesting, equal amounts of cytosolic or nuclear protein lysates were incubated on ice together with 1 μl of monoclonal anti-HIF1α antibody (Supplementary Table S1) in IP buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 5 mM DTT, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM Na3VO4), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics; Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 2 h with agitation. Protein A/G beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Rockford, IL, USA) in IP buffer (10 μl) were added and incubated overnight. The beads were then precipitated by centrifugation for 1 min at 10 000 g at 4 °C. The immune complexes on the beads were washed three times with washing buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail). The samples were run on SDS-PAGE and the blots were probed using polyclonal rabbit anti-Arnt2 antibody (Supplementary Table S1) as described above.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

PMK were grown to 80% confluency on three 60 mm Petri dishes and subjected to chromatin isolation and immunoprecipitation using the ChIP IT Express Enzymatic Magnetic Kit (53009, Active Motif; Carlsbad, CA, USA). ChIP was performed by incubating 10 μg of sheared chromatin with 3 μg of Arnt antibody (sc-8076, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Precipitated DNA was analysed by qPCR relative to a 1:2 dilution standard curve of input DNA. Reactions were run on a Biorad MJ Mini Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad; Herfordshire, UK) using Quantifast SYBR green qPCR kit (204054, Qiagen; Sussex, UK). Primers used are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

RESULTS

Epidermal Arnt Deficiency in Newborn Mice Results in Severe Defects in Dermal Vasculature

Analysis of the skin of ArntΔ/Δ newborn mice using a dissecting stereomicroscope revealed that their trunk is covered by multiple tiny haemorrhagic spots (Figure 1a, black arrows). These spots were not visible macroscopically, but provided Arnt-null skin a bluish appearance contrasting with pinkish skin of control littermates. In some ArntΔ/Δ newborns, body regions subjected to prominent mechanical stress (paws, throat and groin) showed noticeable intra- or even per-cutaneous bleeding (Figures 1c and e). The capillaries and blood vessels in the dermis of ArntΔ/Δ newborns were significantly increased in size and density (Figures 1f and g) possibly also contributing to the darker appearance of their skin. Multiple vessels were seen not only in reticular but also in papillary dermis and even at the epidermal–dermal junction (Figure 1f, arrows). Some vessels were dramatically enlarged and had very thin and sometimes discontinuous or leaky walls (Figure 1f, dashed oval). In contrast, in the skin of control littermates, dermal vasculature was mainly represented by small capillaries located in the reticular dermis and infrequent blood vessels with a prominent cellular lining (Figures 1h and i, arrowheads).

(a–e) Petechia- and telangiectasia-like vasculopathy in the skin of ArntΔ/Δ mouse pups. Skin surface of Arntflox/flox:K14Cre+ newborn mice had multiple tiny haemorrhagic spots (a, black arrows) absent in the skin of control littermates (b). In some ArntΔ/Δ newborns, body regions subjected to mechanical stress (paws, throat and groin) showed noticeable per-cutaneous bleeding (c) never observed in control animals (d). Scanning electron microscopy of the skin surface in ArntΔ/Δ newborns showed erythrocytes (white arrows) deep in the micro-cracks of the corny layer (e). (f–i) Skin histology (H&E) in ArntΔ/Δ and control mouse newborns. Sections of dorsal (f, h) and ventral (g, i) skin are shown. The skin of ArntΔ/Δ (f, g) pups is excessively and irregularly vascularized. Numerous blood vessels of varying sizes are seen not only in reticular but also in papillary dermis and at epidermal–dermal junction (f, arrows). Dysmorphic, highly dilated vessels are very common for the dermis of ArntΔ/Δ pups (f, dashed oval). In contrast, in the skin of control littermates (h, i), vasculature is represented by small capillaries located in reticular dermis (h, arrowhead) and infrequent blood vessels with prominent epithelial lining (arrowhead in i) which was often malformed in ArntΔ/Δ skin (f, g). The more advanced development of hair follicles on panels (f and h) is due to the origin of corresponding samples from the dorsal side of newborn body. Scale bars: 60 μm. (j–l) CD31 (vascular endothelium marker) and Lyve1 (lymphatic endothelium marker) expression in the skin of ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns. Immunofluorescence for CD31 (frozen sections) confirmed massive impregnation of the dermis of ArntΔ/Δ newborns with blood vessels of various sizes (j) including highly dilated malformed vessels (j, dashed line) while lymphatic system, as shown by Lyve1 staining, remained generally intact (k). In the skin of ArntΔ/Δ newborns, some dermal blood vessels were extensively stained for both Lyve1 and CD31 (arrows in j and k and dashed ovals in l). Subcutaneous Lyve1-positive lymphatic vessels in ArntΔ/Δ skin were always negative for CD31 (c, arrowheads). Highly abnormal and dilated vessels characteristic for ArntΔ/Δ mouse skin were always negative for Lyve1 (l, arrow). Scale bars: 60 μm.

Immunofluorescence for CD31 (Pecam-1, the marker for vascular endothelial cells) confirmed massive impregnation of the dermis of ArntΔ/Δ newborns with blood vessels of various sizes (Figure 1j). In control mouse skin, CD31-positivity was localized mostly to the upper reticular dermis while in ArntΔ/Δ newborns CD31-positive blood vessels were distributed all over the dermis from the panniculus carnosus to the basal membrane. Staining for Lyve1 (hyaluronic acid receptor, the marker for lymphatic endothelial cells30) showed that the dermal lymphatic system in ArntΔ/Δ newborns remained generally intact (Figure 1k). Nevertheless, in the skin of control littermates overlapping Lyve1 and CD31 positivity was never seen, whilst in ArntΔ/Δ newborns some vessels stained extensively for both markers (Figure 1, arrows in j and k and dashed ovals in l). Of note, subcutaneous Lyve1-positive lymphatic vessels in ArntΔ/Δ newborns were always negative for CD31 (Figure 1l, arrowheads) indicating that vascular defects do not spread beyond the dermis. Highly abnormal and dilated vessels characteristic for ArntΔ/Δ skin never expressed Lyve1 (Figure 1j, dashed line) thus excluding their developmental association with the lymphatic system.

Depletion of Arnt in Mouse Epidermis Results in Loss of Egln3/Phd3 and Partial Hypoxia-Independent Stabilization of Hif1α

Microarray profiling of epidermal keratinocytes isolated from the skin of ArntΔ/Δ newborn female mice revealed a significant decline (up to 9.6 × compared with control) in the expression of the Egln3 gene coding for prolyl hydroxylase 3 (Phd3) (Table 1). Egln3 was the only prolyl hydroxylase gene differentially expressed in Arnt-deficient mouse epidermis. Downregulation of Egln3/Phd3 in ArntΔ/Δ epidermis was further confirmed by qPCR (Figure 2a) and by WB (Figure 2b).

Downregulation of Egln3 and partial stabilization of Hif1α protein in the epidermis of ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns. Expression of Egln3/Phd3 is significantly suppressed in ArntΔ/Δ mouse epidermis at both mRNA (a, qPCR, performed twice in duplicate; P<0.01) and protein (b, WB, performed twice) levels. As shown by WB and its quantification (c), Hif1α protein level was increased in cytosolic and nuclear fractions of ArntΔ/Δ epidermis about 37% and 17%, respectively, compared to the control epidermis. All blots are representative of samples taken on two occasions in duplicate. Immunocytochemistry using Hif1α-specific antibodies revealed that in culture of control Cre-negative keratinocytes (Arntflox/flox:K14Cre−) with a normal level of Arnt expression about 14.5% of cells are Hif1α-positive (d-3). The fraction of Hif1α-positive cells is doubled (up to 27%) in heterozygous ArntΔ/flox:K14Cre+ cells (d-2; about 50% of normal Arnt level) and tripled (47%) in ArntΔ/Δ:K14Cre+ keratinocytes with complete cessation of Arnt activity (d-1). These differences were highly statistically significant (P<0.01) between all three experimental groups.

Corresponding with the decline of Egln3, WB revealed a significant increase in Hif1α protein in ArntΔ/Δ epidermis (up to 37% in the cytosolic and 17.7% in the nuclear fraction) as compared with the control (Figure 2c). At the same time, qPCR and microarray revealed no changes in Hif1α mRNA.

Immunocytochemistry showed that in control cultures of PMK with a normal level of Arnt (Arntflox/floxK14Cre−) only 14.5% of cells were Hif1α-positive. The fraction of Hif1α-positive cells was almost doubled (reaching 27%) in heterozygous ArntΔ/wtK14Cre+ cells (about 50% of normal Arnt level) and tripled (47%) in ArntΔ/Δ:K14Cre+ keratinocytes with complete cessation of Arnt (Figure 2d). All these findings suggest at least partial stabilization of Hif1α protein in Arnt-deficient keratinocytes and led us to investigate whether Hif1α is able to accumulate in the nucleus and alter gene expression in the absence of Arnt.

Lack of Arnt Does Not Prevent Nuclear Accumulation of Hif1α in ArntΔ/Δ Mouse Keratinocytes

It was previously shown that HIF1α and ARNT tend to leak from the nucleus back to cytoplasm in the absence of either subunit,31 suggesting that heterodimerization is essential for stable association of these proteins with the nuclear compartment. Thus, depletion of Arnt in mouse keratinocytes would potentially lead to depletion of Hif1α nuclear fraction. Using immuno-cytochemistry, we assessed the number of cells with nuclear or cytoplasmic Hif1α localization in ArntΔ/Δ and control PMKs at low (proliferation) and high (differentiation) Ca2+. As expected, in proliferating keratinocytes depletion of Arnt resulted in the prominent decrease in the fraction of cells with exclusively nuclear Hif1α (Figure 3, low Ca2+). High Ca2+ conditions noticeably stimulated nuclear accumulation of Hif1α in control keratinocytes with normal Arnt level. Surprisingly, in Arnt-null cells the switch to high Ca2+ resulted in an even more prominent increase in the number of cells with nuclear Hif1α positivity as compared with differentiating control keratinocytes (Figure 3, high Ca2+).

Sub-cellular localization of Hif1α protein in control and ArntΔ/Δ PMK cultured at low (proliferation) and high Ca2+ (differentiation). The bars show the percentage of control and Arnt-null keratinocytes with exclusively cytoplasmic or nuclear Hif1α localization relative to the total number of Hif1α-positive cells as revealed by immunocytochemistry. In undifferentiated cells (Low Ca2+), Arnt deficiency results in prominent and highly significant (**) decrease in the fraction of cells with nuclear Hif1α localization while the fraction of cells with cytoplasmic Hif1α localization remained almost the same. High Ca2+ conditions (differentiation) induced nuclear accumulation of Hif1α in control keratinocytes. Arnt deficiency encouraged Ca2+-induced nuclear accumulation of Hif1α (High Ca2+). Thus, at low Ca2+, Arnt deficiency restrains nuclear accumulation of Hif1α while at high Ca2+ conditions absence of Arnt promotes accumulation of Hif1α in the nucleus suggesting increased binding of Hif1α to an alternative dimerization partner. One * denotes changes with 0.01<P<0.05 while ** denote highly significant changes with P<0.01.

Arnt Deficiency Promotes Ectopic Expression of Arnt2 and its Dimerization with Hif1α

WB revealed a weak Arnt2 positivity in the nuclear fraction and its total absence in the cytoplasmic fraction of normal (control) epidermal mouse keratinocytes. Nevertheless, depletion of Arnt resulted in the appearance of Arnt2 in the cytoplasm and in its robust increase in the nuclear protein fraction (Figure 4a). In contrast to Arnt2, positive signal for other Arnt homologues—Arntl and Arntl2—was observed neither in normal nor in Arnt-deficient mouse epidermis (not shown).

Arnt deficiency promotes ectopic expression of Arnt2 and its dimerization with Hif1α. Arnt2 level is significantly increased in cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions of ArntΔ/Δ epidermal keratinocytes as compared to control cells (a). The blots represent results obtained on two occasions in duplicate. (b, c) Immunoprecipitation of Hif1α protein complexes from cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of control (wt) and Arnt-null mouse epidermis and their probing using rabbit anti-Arnt2 antibody (co-IP, performed twice) showed that Arnt deficiency leads to a significant (P<0.01) increase in the level of Hif1α–Arnt2 interaction (b) WB; (c) WB quantification. (d) The level of Arnt binding to promoter regions of Arnt2, Egln3 and Actb (negative control) genes as compared to Vegfa gene promoter (conventional Arnt-binding target). The difference between Egln3 and Actb was insignificant while Arnt2 promoter revealed highly significant (**P=0.002) association with Arnt protein. (e) Potential Arnt-binding sites (XRE and HRE) in promoter regions of mouse Vegfa, Egln3 and Arnt2 genes with localization of primers used for ChIP assay (black bars).

Given the partial stabilization of Hif1α in ArntΔ/Δ cells and its significant accumulation in the nuclei of differentiating keratinocytes, a concomitant induction of Arnt2 may potentially lead to increased heterodimerization of these proteins. To check this possibility, we applied co-IP assay to cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of control and Arnt-null mouse epidermis using Hif1α and Arnt2 antibodies. Our results showed that Arnt deficiency leads to a significant increase in the level of Hif1α/Arnt2 co-precipitation (Figures 4b and c).

To explore how Arnt controls expression of Egln3 and Arnt2, we checked whether Arnt protein binds to their promoters. For that, we performed a ChIP assay (Figure 4d) and analysed promoter regions of mouse Egln3 and Arnt2 genes for potential Arnt-binding sites (xenobiotic and hypoxia response elements) using Genomatix Software Suite (http://www.genomatix.de). While the promoter of Vegfa, a conventional HIF1 target, has multiple clustering HRE/XRE motifs, both Egln3 and Arnt2 promoters possess only one potential Arnt-binding site, although close to the transcription start site (Figure 4e). ChIP assay revealed a significant (P<0.001) level of Arnt protein binding to the Arnt2 promoter (about 18% of that for Vegfa) while Egln3 promoter showed no significant association with Arnt protein as compared with negative control—Actb (β-actin) gene promoter (Figure 4d).

Microarray Analysis of Arnt-Deficient Mouse Epidermis Revealed Significant Upregulation of Genes with Potential Role in Control of Angiogenesis, Clotting and Vascular Integrity

As shown by Table 2, a substantial number of genes known to have a role in vascular homeostasis and control of coagulation were significantly induced in ArntΔ/Δ mouse epidermis. In contrast, the list of downregulated genes relevant to vascular function is short and characterized by relatively low fold changes (Table 1) with the only exception being Egln3, which controls Hif1α stability and thus may have an indirect impact on vasculature. Among upregulated genes (Table 2), defensin b3 (Defb3), serpine1 (coding for PAI-1), chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 1 (Cxcl1), thrombomodulin (Thbd), alpha B crystallin (Cryab), metallothionein 1 (Mt1), Adam8 and S100a genes are of particular interest since they are coding for proteins having essential role in control of coagulation, blood vessel permeability, angiogenesis and vascular remodelling.

Suppression of Arnt in the Epidermis Results in Downregulation of vWf in Dermal Compartment of Mouse Skin

Immunohistochemistry for von Willebrand factor (vWf) revealed its significant diminution or even complete absence in the cellular lining of dermal vessels in ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns (Figure 5a–c) as compared with control littermates (Figure 5d and e). Depletion of vWF expression was noted not only in heavily malformed blood vessels (Figure 5a, dashed line) but also in relatively small vessels, which retained their apparently normal morphology (Figure 5b, arrows). Interestingly, in contrast to dermal vessels (Figure 5c, arrow), subcutaneous vasculature (Figure 5c, arrowhead) and blood vessels in K14-negative organs and tissues (eg, lungs, Figure 5f) of ArntΔ/Δ:K14Cre+ pups showed a normal level of vWf expression.

Expression of von Willebrand factor in ArntΔ/Δ (a–c, f) and wt (d, e) mouse skin (a–e) and lungs (f). vWf immuno-reactivity is not detectable in dilated blood vessels of Arnt-deficient skin (a, dashed line; b, c, arrows). Dashed line on (a) indicates enormously dilated and malformed blood vessel with atrophic wall. In contrast, blood vessels in ventral and dorsal skin of control littermates have highly vWf-positive wall (d, e). Multiple vWf-positive capillaries are seen on (e). Although intradermal blood vessels in Arnt-null (ArntΔ/Δ) newborns are vWf-negative (c, arrow), subcutaneous vessels show normal level of vWf immunoreactivity (c, arrowhead); dotted line denotes dermal-subcutis border. Blood vessels in K14-negative tissues (eg, lungs) of ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns had normal level of vWf-positivity (f). Scale bars: 30 μm.

DISCUSSION

Dermal Vascular Phenotype in ArntΔ/Δ Mice Suggests Activation of a Paracrine Epidermal–Dermal Signalling Pathway

Targeted ablation of Arnt in mouse epidermis using K14-driven Cre recombination results not only in a striking epidermal phenotype as we have shown before,25 but also in severe abnormalities in dermal vasculature such as hypervascularization, clotting defects, blood vessel fragility, dilatation and possible leakiness. All these abnormalities eventually lead to intradermal haemorrhage and even percutaneous bleeding (Figures 1a–e). These findings resemble the previously described placental haemorrhage and developmental vascular defects seen in the liver of Arnt-deficient mouse models.32, 33, 34 Nevertheless, in contrast to these studies, we observed vascular defects in the dermis—a tissue maintaining a normal level of Arnt in K14-Arnt KO mice25 and just being adjacent to Arnt-deficient epidermis. These findings are in favour of active epidermal–dermal communication and suggest the existence of secretory Arnt-dependent epidermal signalling pathway targeting dermal vasculature (Figure 6).

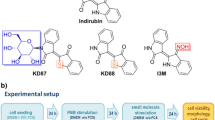

Schematic representation of proposed epidermal–dermal signalling pathway induced in mouse skin by Arnt deficiency. Ablation of Arnt results in downregulation of Egln3 and compensatory activation of Arnt2. This leads to partial stabilization of Hif1α protein and its eventual heterodimerization with unconventional partner—Arnt2 (which is not normally active in the epidermis). Formation of a new transcription factor Hif1α/Arnt2 presumably results in ectopic activation of a number of genes coding for proteins with anticoagulant/angiogenic potential. Secretion of these proteins to the dermis results in deregulation of dermal targets (eg, vWf) and eventual shifts in homeostasis of dermal vasculature.

Downregulation of Egln3/Phd3 and Stabilization of Hif1a in ArntΔ/Δ Mouse Epidermal Keratinocytes

The Egln3 gene (EGL nine homolog 3) codes for prolyl hydroxylase domain 3 (Phd3) enzyme, which together with other members of the family (Egln2/Phd1 and Egln1/Phd2) drives hydroxylation of Hif1α and Hif2α35 thus having the key role in oxygen-dependent maintenance of HIF1/2 activity. Previously, it was reported that in heart and placenta Egln3 is expressed at much higher level than Egln1 and Egln2.36 The exclusive dependence of Egln3 on Arnt activity shown here (Egln1 and Egln2 appeared to be not responsive to Arnt deficiency in mouse epidermis) suggest a chief role of Egln3 in Hif-α turnover not only in the heart and placenta36 but in the epidermis as well.

Although driving oxygen-dependent Hif-α ubiquitination, Egln3 itself is a subject of proteasomal degradation mediated by ubiquitin ligase Siah2.37 Of note, the gene coding for Siah2 is significantly upregulated in Arnt-null mouse keratinocytes (Table 2) thus adding more complexity to HIF1 regulatory loop in the epidermis.

On the basis of these findings, we propose that downregulation of Egln3 represents the main factor of hypoxia-independent partial stabilization of Hif1α protein in Arnt-deficient mouse epidermal keratinocytes. Interestingly, conditional knockout of Egln1 (but not Egln2 or Egln3) leads to increased hypoxia-independent accumulation of Hif1α, hyperactive angiogenesis, angiectasia (blood vessel dilation) and high perfusion of blood vessels in mouse liver.38 This vascular phenotype is remarkably similar to dermal vascular changes in ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns, which nevertheless are associated with sharp downregulation of Egln3 but not Egln1. Prevalent expression of the Egln3 isoform in the epidermis (Weir et al., unpublished) suggests that the role Egln1 has in the liver is fulfilled by Egln3 in the skin thus providing another evidence for functional tissue specificity of different Egln/Phd proteins. Interestingly, increased accumulation of Hif1α and a burst of angiogenesis in the liver of Egln1 KO mice were not accompanied by anticipated increase in expression of Vegf-α,38 similarly to our observations in the skin of ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns.

Impairment of the mechanism of Hif1α proteasomal degradation in ArntΔ/Δ keratinocytes is confirmed by significant increase in Hif1α protein level and the number of Hif1α-positive cells while the level of Hif1α mRNA remains comparable to control both in vivo and in vitro (microarray and qPCR results). Non-inflammatory hypervascularization of papillary dermis in ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns is reminiscent of the phenotype in mice with K14-driven overexpression of human HIF1α with a deleted oxygen-dependent degradation domain.15 This analogy further confirms that hypoxia-independent stabilization of Hif1α in Arnt-deficient epidermis is functionally linked to dermal vascular phenotype in ArntΔ/Δmouse newborns.

Compensatory Upregulation of Arnt2 and Hif1α/Arnt2 Dimerization in ArntΔ/Δ Mouse Epidermis

High Ca2+ conditions stimulate Hif1α accumulation in the nuclei of ArntΔ/Δ keratinocytes. Since dimerization is essential for Hif1α retention in the nucleus,31 this finding suggests that in the absence of Arnt Hif1α dimerizes with an alternative partner. Previously, dimerization of Hif1α with three still poorly characterized Arnt homologues—Arnt2, Arntl (Bmal1, MOP3 or Arnt3), and Arntl2 (Bmal2 or MOP9)—was reported.39, 40, 41, 42 Nevertheless, the functional significance of these dimerization events is as yet unclear. The above Arnt homologues were found exclusively in neural tissues and kidney with the only exception of Arntl, which has been also identified in cultured human keratinocytes43 and in full-thickness human skin punch biopsies44 at mRNA level. Given that Arntl is expressed in the epidermis and can induce Serpine1 (PAI-1),45 a gene that was highly upregulated in Arnt-null keratinocytes,25 we initially assumed that Arntl may serve as a potential alternative dimerization partner for Hif1α in ArntΔ/Δ keratinocytes. However, we failed to detect any positive signal for Arntl and Arntl2 proteins in both normal and ArntΔ/Δ mouse epidermis. Instead, we found a very high level of Arnt2 protein in Arnt-null epidermis (Figure 4a). In control mouse epidermis, Arnt2 positivity was barely detected suggesting its negligible role in normal skin and further supporting our previous findings in mouse and human keratinocytes in vitro.26

HIF activity maintained by Arnt/Hif1α and Arnt/Hif2α heterodimerization has a crucial role in control of basic physiological processes in the cell.46, 47, 48 Therefore, the existence of a backup mechanism compensating for Arnt deficiency should be beneficial for any tissue and especially for the epidermis given its constant exposure to environmental stressors acting through Arnt-dependent pathways. Our results identify ectopic induction of Arnt2 as an epidermis-specific mechanism compensating for compromised Arnt activity. The potential role of Arnt2/Hif1α dimerization in the maintenance of steady-state HIF activity in Arnt-deficient epidermis is further supported by sustained expression of several conventional Hif1 targets in ArntΔ/Δ mouse keratinocytes (Table 2).

Of interest, compensatory induction of Arnt2 in ArntΔ/Δ keratinocytes was not sufficient to restore the expression of Egln3 (as well as some other conventional HIF1 targets) thus supporting the view that functions of Arnt and Arnt2 while overlapping are not identical. Previously, it was shown that while being able to mediate the hypoxic response as effectively as Arnt, Arnt2 is nearly incapable of interacting with ligand-activated AhR.42 On the other hand, Arnt2 has some unique functions uncharacteristic for Arnt,49 which is indirectly supported by prenatal lethality of Arnt2 knockout mice.50 Our data suggest that conventional Hif1 target genes downregulated in ArntΔ/Δ keratinocytes (ie, Egln3, Higd1a or Aldoc; Table 1) may be specifically controlled by Arnt (since compensatory upregulation of Arnt2 was not sufficient to maintain their level) while Hif1 targets with unchanged expression (eg, Glut1, Pdk1 and Vegf genes) may be equally responsive to transcriptional activation by Hif1α/Arnt and Hif1α/Arnt2 heterodimers. Conventional Hif1 targets upregulated in Arnt-deficient epidermis (eg, Serpine1, Socs3, Zfp36 or Id1; Table 2) may be more responsive to transactivation by Hif1α/Arnt2. Thus, taking into account the difference in Arnt and Arnt2 functions, we assume that induction of Arnt2, hypoxia-independent stabilization of Hif1α, and eventual Hif1α/Arnt2 dimerization in Arnt-null keratinocytes may result in activation of an ectopic regulatory pathway (Figure 6) leading to epidermal defects25, 51 and dermal vascular pathology, as shown here.

The upregulation of Arnt2 in ArntΔ/Δ mouse keratinocytes suggest that in normal epidermis expression of Arnt2 may be blocked by Arnt. Our results showed that the Arnt protein binds to the Arnt2 promoter with relatively high efficiency (in contrast to Egln3 promoter; Figure 4d) thus further supporting the role of Arnt in control of Arnt2 expression, but the exact mechanism(s) maintaining the balance between Arnt and Arnt2 in the epidermis remain to be elucidated.

Arnt-Dependent Epidermal/Dermal Signalling Pathway—Possible Effectors and Targets

The proposed Arnt-dependent epidermal signalling appears to be targeted specifically at the dermal vasculature since morphological vascular defects did not spread beyond the dermis. Abnormal colocalization of CD31 and Lyve1 exclusively in the dermal vessels and not in subcutaneous vasculature of Arnt-deficient mice (Figure 1j–l) also supports this notion. Although both blood and lymphatic vessels derive from the same venous endothelial precursors, they normally remain distinct52 and can be readily differentiated based on CD31/Lyve1 staining.30 Therefore, the overlap of these markers in the dermal vessels of ArntΔ/Δ mouse pups denotes developmental or functional myoepithelial abnormality induced by epidermal Arnt-deficiency. During embryogenesis, the separation between blood and lymphatic vasculature is regulated by a number of factors such as Syk, Slp-76 (Lcp2), T-synthase, Plcg2 and Prox1.53, 54, 55, 56 A cutaneous haemorrhage, very similar to the phenotype observed in ArntΔ/Δ pups, is the most striking feature in mouse embryos lacking these proteins.57, 58, 59 Of interest, our microarray studies revealed a modest but statistically significant downregulation of Syk gene (1.35 × ) in ArntΔ/Δ mouse epidermis.

Dermal vasculopathy in ArntΔ/Δ mice is reminiscent of petechiae and telangiectasia induced in human skin by anticoagulant dicoumarol60 suggesting that Arnt-dependent epidermal signalling specifically targets dermal coagulation pathways. Microarray analysis revealed several potential effectors for this signalling (Table 2). Among them are S100a8 and S100a9 genes coding for myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14, which both are dramatically upregulated in Arnt-deficient mouse epidermis (about 46- and 21-fold, respectively). The S100a8/S100a9 heterocomplex (calprotectin) is critical for vascular response to injury61 and is implicated in neutrophil activation62 known to modulate blood vessel permeability.63 The S100a8/S100a9 complex was also shown to be secreted by keratinocytes,64 thus making it a good candidate for Arnt-dependent epidermal–dermal communication. S100a10 is also upregulated in Arnt-deficient epidermis (about 2 × ) and represents a key element of maintaining fibrinolytic balance on blood vessel surface.65 The extracellular activity of S100a10 is well-documented66 and its overexpression is linked to excessive fibrinolysis and haemorrhage67 suggesting possible implication of S100a10 in dermal vascular phenotype in ArntΔ/Δ mice. Upregulation of thrombomodulin (Thbd; 3.54 × ), a potent suppressor of coagulation through modulation of the protein C pathway and inhibition of thrombin68, 69may also contribute to haemorrhagic skin phenotype in ArntΔ/Δ mouse pups. It has also been shown that epidermal keratinocytes are able to secrete thrombomodulin both in vivo and in vitro.70, 71 Serpine1 coding for PAI-1 protein (20-fold increase in ArntΔ/Δ epidermis) is another candidate for targeting dermal vasculature. PAI-1 is known to promote angiogenesis, accelerate proliferation and decrease apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. It is also involved in vascular remodelling72 and is actively secreted by epidermal keratinocytes.73 Overexpression of PAI-1 is associated with vascular pathology in humans.74 Nevertheless, the exact role of Serpine1/PAI-1 in vasculopathy is not fully understood and remains controversial.75 Other potential candidates for Arnt-dependent epidermal–dermal signalling are defensin b3 (Defb3; 25-fold up) and chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 1 (Cxcl1; 14-fold up), which both are positive regulators of vascular permeability (also in dermal capillaries) and are secreted by keratinocytes.76, 77 Then, Egr1, Cryab, Mt1, Adam8 and Siah2, which are upregulated in ArntΔ/Δ mouse epidermis about 2–3-fold, are all known to modulate the activity of endothelial cells and promote angiogenesis.78, 79, 80, 81, 82 Suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (Socs 3; 6.35-fold up) is also of interest here because of its association with vascular invasion and sensitivity to hypoxia.83, 84 Upregulation of the above genes in Arnt-deficient mouse epidermis and secretion of corresponding proteins to the dermis may account for specific aspects of dermal blood vessel phenotype in ArntΔ/Δ mice. Validation of these results both in vivo (in ArntΔ/Δ mouse epidermis) and in vitro (in culture medium conditioned by Arnt-deficient mouse and human keratinocytes) is an essential next step in further characterization of epidermal–dermal signalling pathway revealed by our studies.

The haemorrhagic skin phenotype observed in ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns is also reminiscent of a number of human bleeding disorders such as hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia,85 platelet function disorders and von Willebrand disease.86 Von Willebrand disease is one of the most common inherited bleeding disorders characterized by the deficiency of vWf, which is a plasma protein performing two main functions in homeostasis: mediating platelet adhesion to the injured vessel wall and protecting coagulation factor VIII against proteolytic inactivation.87 Absence of positive signal for vWf in the cellular lining of dermal blood vessels in ArntΔ/Δ pups (Figure 5) suggests that vWf may represent a dermal target for Arnt-dependent epidermal–dermal signalling. This proposition is supported by the similarity between vascular phenotype in ArntΔ/Δ mouse newborns and the mouse model for von Willebrand disease.88

Altogether, our results reveal a new role for Arnt, Arnt2 and Hif1α in maintenance of skin homeostasis and outline a novel epidermal–dermal signalling pathway implicated in control of dermal vasculature and potentially linked to skin tumourigenesis, wound healing, and psoriasis (Figure 6). Mice with targeted ablation of Arnt in the epidermis may represent a useful model to study epidermal–dermal and tumour–stroma communications.

Given the role of Arnt in adaptive response to environmental stress further characterization of this pathway may shed light on the role of environmental factors in vascular functions of normal and diseased skin.

References

Detmar M . Tumor angiogenesis. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 2000;5:20–23.

Mecklenburg L, Tobin DJ, Muller-Rover S, et al. Active hair growth (anagen) is associated with angiogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 2000;114:909–916.

Bhushan M, Young HS, Brenchley PE, et al. Recent advances in cutaneous angiogenesis. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:418–425.

Rosenberger C, Solovan C, Rosenberger AD, et al. Upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factors in normal and psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:2445–2452.

Chang E, Yang J, Nagavarapu U, et al. Aging and survival of cutaneous microvasculature. J Invest Dermatol 2002;118:752–758.

Li L, Mac-Mary S, Sainthillier JM, et al. Age-related changes of the cutaneous microcirculation in vivo. Gerontology 2006;52:142–153.

Detmar M . The role of VEGF and thrombospondins in skin angiogenesis. J Dermatol Sci 2000;24 (Suppl 1):S78–S84.

Wong BJ, Minson CT . Neurokinin-1 receptor desensitization attenuates cutaneous active vasodilatation in humans. J Physiol 2006;577:1043–1051.

Yano K, Kadoya K, Kajiya K, et al. Ultraviolet B irradiation of human skin induces an angiogenic switch that is mediated by upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and by downregulation of thrombospondin-1. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:115–121.

Boutin AT, Weidemann A, Fu Z, et al. Epidermal sensing of oxygen is essential for systemic hypoxic response. Cell 2008;133:223–234.

Barnhill RL, Parkinson EK, Ryan TJ . Supernatants from cultured human epidermal keratinocytes stimulate angiogenesis. Br J Dermatol 1984;110:273–281.

Malhotra R, Stenn KS, Fernandez LA, et al. Angiogenic properties of normal and psoriatic skin associate with epidermis, not dermis. Lab Invest 1989;61:162–165.

Detmar M, Brown LF, Claffey KP, et al. Overexpression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in psoriasis. J Exp Med 1994;180:1141–1146.

Detmar M, Brown LF, Schon MP, et al. Increased microvascular density and enhanced leukocyte rolling and adhesion in the skin of VEGF transgenic mice. J Invest Dermatol 1998;111:1–6.

Elson DA, Thurston G, Huang LE, et al. Induction of hypervascularity without leakage or inflammation in transgenic mice overexpressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Genes Dev 2001;15:2520–2532.

Cockman ME, Masson N, Mole DR, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J Biol Chem 2000;275:25733–25741.

Gruber M, Simon MC . Hypoxia-inducible factors, hypoxia, and tumor angiogenesis. Curr Opin Hematol 2006;13:169–174.

Tanimoto K, Makino Y, Pereira T, et al. Mechanism of regulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. Embo J 2000;19:4298–4309.

Guillemin K, Krasnow MA . The hypoxic response: huffing and HIFing. Cell 1997;89:9–12.

Semenza GL, Wang GL . A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol 1992;12:5447–5454.

Gu YZ, Hogenesch JB, Bradfield CA . The PAS superfamily: sensors of environmental and developmental signals. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2000;40:519–561.

Goda N, Dozier SJ, Johnson RS . HIF-1 in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and tumor progression. Antioxid Redox Signal 2003;5:467–473.

Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:5510–5514.

Choi SM, Oh H, Park H . Microarray analyses of hypoxia-regulated genes in an aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt)-dependent manner. Febs J 2008;275:5618–5634.

Geng S, Mezentsev A, Kalachikov S, et al. Targeted ablation of Arnt in mouse epidermis results in profound defects in desquamation and epidermal barrier function. J Cell Sci 2006;119:4901–4912.

Weir L, Robertson D, Leigh IM, et al. Hypoxia-mediated control of HIF/ARNT machinery in epidermal keratinocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1813:60–72.

Vasioukhin V, Degenstein L, Wise B, et al. The magical touch: genome targeting in epidermal stem cells induced by tamoxifen application to mouse skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:8551–8556.

Tomita S, Sinal CJ, Yim SH, et al. Conditional disruption of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) gene leads to loss of target gene induction by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Endocrinol 2000;14:1674–1681.

Maloyan A, Eli-Berchoer L, Semenza GL, et al. HIF-1alpha-targeted pathways are activated by heat acclimation and contribute to acclimation-ischemic cross-tolerance in the heart. Physiol Genomics 2005;23:79–88.

Banerji S, Ni J, Wang SX, et al. LYVE-1, a new homologue of the CD44 glycoprotein, is a lymph-specific receptor for hyaluronan. J Cell Biol 1999;144:789–801.

Chilov D, Camenisch G, Kvietikova I, et al. Induction and nuclear translocation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1): heterodimerization with ARNT is not necessary for nuclear accumulation of HIF-1alpha. J Cell Sci 1999;112:1203–1212.

Maltepe E, Schmidt JV, Baunoch D, et al. Abnormal angiogenesis and responses to glucose and oxygen deprivation in mice lacking the protein ARNT. Nature 1997;386:403–407.

Kozak KR, Abbott B, Hankinson O . ARNT-deficient mice and placental differentiation. Dev Biol 1997;191:297–305.

Walisser JA, Bunger MK, Glover E, et al. Patent ductus venosus and dioxin resistance in mice harboring a hypomorphic Arnt allele. J Biol Chem 2004;279:16326–16331.

Fandrey J, Gorr TA, Gassmann M . Regulating cellular oxygen sensing by hydroxylation. Cardiovasc Res 2006;71:642–651.

Oehme F, Ellinghaus P, Kolkhof P, et al. Overexpression of PH-4, a novel putative proline 4-hydroxylase, modulates activity of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002;296:343–349.

Nakayama K, Frew IJ, Hagensen M, et al. Siah2 regulates stability of prolyl-hydroxylases, controls HIF1alpha abundance, and modulates physiological responses to hypoxia. Cell 2004;117:941–952.

Takeda K, Cowan A, Fong GH . Essential role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis of the adult vascular system. Circulation 2007;116:774–781.

Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, et al. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1a regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:4273–4278.

Takahata S, Sogawa K, Kobayashi A, et al. Transcriptionally active heterodimer formation of an Arnt-like PAS protein, Arnt3, with HIF-1a, HLF, and clock. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998;248:789–794.

Hogenesch JB, Gu YZ, Moran SM, et al. The basic helix-loop-helix-PAS protein MOP9 is a brain-specific heterodimeric partner of circadian and hypoxia factors. J Neurosci 2000;20:RC83.

Sekine H, Mimura J, Yamamoto M . Unique and overlapping transcriptional roles of arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) and Arnt2 in xenobiotic and hypoxic responses. J Biol Chem 2006;281:37507–37516.

Kawara S, Mydlarski R, Mamelak AJ, et al. Low-dose ultraviolet B rays alter the mRNA expression of the circadian clock genes in cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2002;119:1220–1223.

Bjarnason GA, Jordan RC, Wood PA, et al. Circadian expression of clock genes in human oral mucosa and skin: association with specific cell-cycle phases. Am J Pathol 2001;158:1793–1801.

Schoenhard JA, Smith LH, Painter CA, et al. Regulation of the PAI-1 promoter by circadian clock components: differential activation by BMAL1 and BMAL2. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2003;35:473–481.

Semenza GL . Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and the molecular physiology of oxygen homeostasis. J Lab Clin Med 1998;131:207–214.

Blancher C, Moore JW, Talks KL, et al. Relationship of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha expression to vascular endothelial growth factor induction and hypoxia survival in human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 2000;60:7106–7113.

Kaelin Jr WG . The von Hippel-Lindau protein, HIF hydroxylation, and oxygen sensing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;338:627–638.

Keith B, Adelman DM, Simon MC . Targeted mutation of the murine arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 2 (Arnt2) gene reveals partial redundancy with Arnt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:6692–6697.

Hosoya T, Oda Y, Takahashi S, et al. Defective development of secretory neurones in the hypothalamus of Arnt2-knockout mice. Genes Cells 2001;6:361–374.

Takagi S, Tojo H, Tomita S, et al. Alteration of the 4-sphingenine scaffolds of ceramides in keratinocyte-specific Arnt-deficient mice affects skin barrier function. J Clin Invest 2003;112:1372–1382.

Oliver G, Alitalo K . The lymphatic vasculature: recent progress and paradigms. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2005;21:457–483.

Wigle JT, Oliver G . Prox1 function is required for the development of the murine lymphatic system. Cell 1999;98:769–778.

Abtahian F, Guerriero A, Sebzda E, et al. Regulation of blood and lymphatic vascular separation by signaling proteins SLP-76 and Syk. Science 2003;299:247–251.

Fu J, Gerhardt H, McDaniel JM, et al. Endothelial cell O-glycan deficiency causes blood/lymphatic misconnections and consequent fatty liver disease in mice. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3725–3737.

Ichise H, Ichise T, Ohtani O, et al. Phospholipase Cgamma2 is necessary for separation of blood and lymphatic vasculature in mice. Development 2009;136:191–195.

Turner M, Mee PJ, Costello PS, et al. Perinatal lethality and blocked B-cell development in mice lacking the tyrosine kinase Syk. Nature 1995;378:298–302.

Cheng AM, Rowley B, Pao W, et al. Syk tyrosine kinase required for mouse viability and B-cell development. Nature 1995;378:303–306.

Clements JL, Lee JR, Gross B, et al. Fetal hemorrhage and platelet dysfunction in SLP-76-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 1999;103:19–25.

Nalbandian RM, Mader IJ, Barrett JL, et al. Petechiae, ecchymoses, and necrosis of skin induced by coumarin congeners: rare, occasionally lethal complication of anticoagulant therapy. Jama 1965;192:603–608.

Croce K, Gao H, Wang Y, et al. Myeloid-related protein-8/14 is critical for the biological response to vascular injury. Circulation 2009;120:427–436.

Ryckman C, Vandal K, Rouleau P, et al. Proinflammatory activities of S100: proteins S100A8, S100A9, and S100A8/A9 induce neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion. J Immunol 2003;170:3233–3242.

Wedmore CV, Williams TJ . Control of vascular permeability by polymorphonuclear leukocytes in inflammation. Nature 1981;289:646–650.

Thorey IS, Roth J, Regenbogen JS, et al. The Ca2+-binding proteins S100A8 and S100A9 are encoded by novel injury-regulated genes. J Biol Chem 2001;276:35818–35825.

Dassah M, Deora AB, He K, et al. The endothelial cell annexin A2 system and vascular fibrinolysis. Gen Physiol Biophys 2009;28:F20–F28.

Donato R . Intracellular and extracellular roles of S100 proteins. Microsc Res Tech 2003;60:540–551.

He KL, Deora AB, Xiong H, et al. Endothelial cell annexin A2 regulates polyubiquitination and degradation of its binding partner S100A10/p11. J Biol Chem 2008;283:19192–19200.

Hanly AM, Hayanga A, Winter DC, et al. Thrombomodulin: tumour biology and prognostic implications. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005;31:217–220.

Jackson CJ, Xue M . Activated protein C - an anticoagulant that does more than stop clots. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008;40:2692–2697.

Daimon T, Nakano M . Immunohistochemical localization of thrombomodulin in the stratified epithelium of the rat is restricted to the keratinizing epidermis. Histochem Cell Biol 1999;112:437–442.

Artuc M, Hermes B, Algermissen B, et al. Expression of prothrombin, thrombin and its receptors in human scars. Exp Dermatol 2006;15:523–529.

Balsara RD, Ploplis VA . Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1: the double-edged sword in apoptosis. Thromb Haemost 2008;100:1029–1036.

Braungart E, Magdolen V, Degitz K . Retinoic acid upregulates the plasminogen activator system in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2001;116:778–784.

Hecke A, Brooks H, Meryet-Figuiere M, et al. Successful silencing of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human vascular endothelial cells using small interfering RNA. Thromb Haemost 2006;95:857–864.

Schafer K, Konstantinides S . PAI-1 and vasculopathy: the debate continues. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:13–15.

Chen X, Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, et al. Antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensin (hBD)-3 and hBD-4 activate mast cells and increase skin vascular permeability. Eur J Immunol 2007;37:434–444.

DiStasi MR, Ley K . Opening the flood-gates: how neutrophil-endothelial interactions regulate permeability. Trends Immunol 2009;30:547–556.

Abdel-Malak NA, Mofarrahi M, Mayaki D, et al. Early growth response-1 regulates angiopoietin-1-induced endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009;29:209–216.

Kase S, He S, Sonoda S, et al. alphaB-crystallin regulation of angiogenesis by modulation of VEGF. Blood 2010;115:3398–3406.

Miyashita H, Sato Y . Metallothionein 1 is a downstream target of vascular endothelial zinc finger 1 (VEZF1) in endothelial cells and participates in the regulation of angiogenesis. Endothelium 2005;12:163–170.

Guaiquil VH, Swendeman S, Zhou W, et al. ADAM8 is a negative regulator of retinal neovascularization and of the growth of heterotopically injected tumor cells in mice. J Mol Med 2010;88:497–505.

Nakayama K, Qi J, Ronai Z . The ubiquitin ligase Siah2 and the hypoxia response. Mol Cancer Res 2009;7:443–451.

Bai L, Yu Z, Qian G, et al. SOCS3 was induced by hypoxia and suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2006;152:83–91.

Yang SF, Yeh YT, Wang SN, et al. SOCS-3 is associated with vascular invasion and overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathology 2008;40:558–563.

Braverman IM, Keh A, Jacobson BS . Ultrastructure and three-dimensional organization of the telangiectases of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Invest Dermatol 1990;95:422–427.

Mezzano D, Quiroga T, Pereira J . The level of laboratory testing required for diagnosis or exclusion of a platelet function disorder using platelet aggregation and secretion assays. Semin Thromb Hemost 2009;35:242–254.

Weiss HJ, Sussman II, Hoyer LW . Stabilization of factor VIII in plasma by the von Willebrand factor. Studies on posttransfusion and dissociated factor VIII and in patients with von Willebrand's disease. J Clin Invest 1977;60:390–404.

Denis C, Methia N, Frenette PS, et al. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:9524–9529.

Takuwa Y, Takuwa N, Sugimoto N . The Edg family G protein-coupled receptors for lysophospholipids: their signaling properties and biological activities. J Biochem 2002;131:767–771.

Yonesu K, Kawase Y, Inoue T, et al. Involvement of sphingosine-1-phosphate and S1P1 in angiogenesis: analyses using a new S1P1 antagonist of non-sphingosine-1-phosphate analog. Biochem Pharmacol 2009;77:1011–1020.

Denko N, Schindler C, Koong A, et al. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression in cervical cancer cells by the tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:480–487.

Wahl AS, Buchthal B, Rode F, et al. Hypoxic/ischemic conditions induce expression of the putative pro-death gene Clca1 via activation of extrasynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Neuroscience 2009;158:344–352.

Jian B, Wang D, Chen D, et al. Hypoxia-induced alteration of mitochondrial genes in cardiomyocytes. role of Bnip3 and Pdk1. Shock 2010;34:169–175.

Schober A, Zernecke A . Chemokines in vascular remodeling. Thromb Haemost 2007;97:730–737.

Essafi-Benkhadir K, Onesto C, Stebe E, et al. Tristetraprolin inhibits Ras-dependent tumor vascularization by inducing vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA degradation. Mol Biol Cell 2007;18:4648–4658.

Kim TW, Yim S, Choi BJ, et al. Tristetraprolin regulates the stability of HIF-1alpha mRNA during prolonged hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;391:963–968.

Van de Wouwer M, Collen D, Conway EM . Thrombomodulin-protein C-EPCR system: integrated to regulate coagulation and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:1374–1383.

Yan SF, Fujita T, Lu J, et al. Egr-1, a master switch coordinating upregulation of divergent gene families underlying ischemic stress. Nat Med 2000;6:1355–1361.

Liao H, Hyman MC, Lawrence DA, et al. Molecular regulation of the PAI-1 gene by hypoxia: contributions of Egr-1, HIF-1alpha, and C/EBPalpha. Faseb J 2006;21:935–949.

Impagnatiello MA, Weitzer S, Gannon G, et al. Mammalian sprouty-1 and -2 are membrane-anchored phosphoprotein inhibitors of growth factor signaling in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol 2001;152:1087–1098.

Zhang C, Chaturvedi D, Jaggar L, et al. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration by human sprouty 2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:533–538.

Qin H, Shao Q, Thomas T, et al. Connexin26 regulates the expression of angiogenesis-related genes in human breast tumor cells by both GJIC-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell Commun Adhes 2003;10:387–393.

Raffel GD, Chu GC, Jesneck JL, et al. Ott1 (Rbm15) is essential for placental vascular branching morphogenesis and embryonic development of the heart and spleen. Mol Cell Biol 2009;29:333–341.

Benezra R, Rafii S, Lyden D . The Id proteins and angiogenesis. Oncogene 2001;20:8334–8341.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Elaine Fuchs, Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA and Frank Gonzalez, NCI, Bethesda, MD, USA, DC, for kind donation of the K14:Cre and Arnt:flox mice respectively. This work was supported by NIH/NIAMS (K01 AR02204), Dermatology Foundation and American Skin Association Research Grants to AAP and NIH/NIAMS T32 Research Training Grant to AW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Laboratory Investigation website

A novel Arnt-dependent paracrine signalling pathway links epidermal HIF activity and dermal vascular homeostasis. Given the role of Arnt in the adaptive response and the similarity of the reported phenotype with vascular features of tumor stroma and psoriatic skin, this pathway may serve as an interface between environmental stress and skin pathology.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wondimu, A., Weir, L., Robertson, D. et al. Loss of Arnt (Hif1β) in mouse epidermis triggers dermal angiogenesis, blood vessel dilation and clotting defects. Lab Invest 92, 110–124 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2011.134

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2011.134