Abstract

Optical diodes are fundamental elements for optical computing and information processing. Attempts to realize such non-reciprocal propagation of light by breaking the time-reversal symmetry include using indirect interband photonic transitions, the magneto-optical effect, optical nonlinearity or photonic crystals. Alternatively, asymmetric reciprocal transmission of light has been proposed in photonic metamaterial structures for either circularly or linearly polarized waves. Here we employ the recent concept of gradient index metamaterials to demonstrate a waveguide with asymmetric propagation of light, independent of polarization. The device blocks both transverse electric and magnetic polarized modes in one direction but transmits them in the other for a broadband spectrum. Unlike previous works using chiral properties of metamaterials, our device is based on the principle of momentum symmetry breaking at interfaces with phase discontinuities. Experiments in the microwave region verify our findings, which may pave the way to feasible passive optical diodes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrical diodes with p-n junctions are fundamental elements for integrated circuits. Similarly, devices with optical diode effect are fundamental elements for information processing in optical integration systems. Great efforts have been made to realize such ‘optical diodes’ with non-reciprocal propagation of light by breaking the time-reversal symmetry, such as indirect interband photonic transition1,2, magneto-optic effect3,4,5,6,7, optical nonlinearity8,9,10 or photonic crystals11. In addition, numerous reciprocal structures are designed as alternatives to achieve asymmetric propagation of light by employing metamaterials12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 for either circularly polarized waves or linearly polarized waves.

Recently, the concept of phase discontinuity21,22 and metasurfaces has been used to manipulate the propagation of light and change the conventional laws of reflection and refraction. The basic idea is that abrupt phase shifts are introduced at the interface between two media, which are a function of position. Such a configuration will break the momentum symmetry and provide an additional tangential momentum to match the momentum conservation, thereby changing the propagation of light at the interface. This allows for the design of optical components with ultrathin thickness to achieve functionalities that go beyond traditional approaches23,24. In fact, the strong interaction between light and metasurfaces has also provided new ways to control polarization so that metasurface lenses can function differently for different polarizations, including dipolar lenses and polarization-dependent directional couplers24,25,26,27,28,29. Recent approaches exploit the polarization of incident light to generate asymmetric propagation of light28,30. However, it will be more useful to obtain asymmetric propagation independent of polarization.

Here we utilize the metasurface concept and employ gradient index metamaterials23 (GIMs) to design a simple waveguide structure to realize asymmetric propagations of light. We first combine two metasurfaces into a waveguide structure and heuristically explain the asymmetric propagation from the view of geometric optics. We also find that if we sacrifice the thickness, the metasurfaces will become GIMs. We numerically find that such a device can work in a broad band of spectrum and is not limited to different polarizations of light. By several steps of reduction, we fabricate a prototype for microwave frequencies. The measurements verify asymmetric propagation and agree with the simulations very well.

Results

Concept of asymmetric propagation for a point source

We start our configuration with the schematic diagram in Fig. 1, that is, a waveguide structure with three layers of media. In the middle is air of width w, which is sandwiched by two slabs of GIMs of width d. The outer boundaries are the perfect electric conductor (PEC) walls. The index profile of the GIMs are both,

(a) Schematic diagram of a one-dimensional waveguide structure with two layers of GIMs of width d (the gradually changing blue regions). The core medium in the waveguide is air. An excited point source is located inside the waveguide. The waveguide is bounded by perfect electric conductor walls. (b) The simulated Ez field distribution for a TE polarized line source (denoted by a red point) inside the waveguide without the GIMs. (c) The simulated Ez field distribution for a TE source when the GIMs are attached, showing the asymmetric propagation. Ez in (b) and (c) is in units of V m−1. (d) The simulated Hz field distribution for a TM polarized line source (denoted by a tiny circle) inside the waveguide without the GIMs. (e) The simulated Hz field distribution for a TM source when the GIMs are attached, showing the asymmetric propagation. Hz in (d) and (e) is in units of A m−1. The black arrows represent the power flow of time-averaged Poynting vectors.

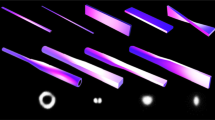

where x0 is the starting point of the waveguide structure, k0 is the wave vector in free space and κ is a crucial momentum parameter for designing the novel properties of waveguide23. First, let us look at what happens if we put a line source inside the waveguide. For a transverse electric (TE) mode, a line current source is applied. An asymmetric propagation is visually exhibited in Fig. 1b,c. In Fig. 1b, we show that without the GIMs, the electromagnetic (EM) wave radiates in both directions, whereas with the GIMs attached, the EM wave mainly propagates along the +x direction, as shown in Fig. 1c. To show the effect more clearly, we also plot the power flow of Poynting vectors (time-averaged, S=c/(8π)Re[E × H*]) accordingly. We find that the power flows in both directions if the GIMs are absent, whereas for the current structure with GIMs, the power flowing along the − x direction will be suppressed at a position and come back to join the power flowing along the +x direction. In the simulations, the parameters are set as follows: w is 22.5 mm; κ is 0.2k0; the length of the waveguide L is 240 mm, the starting point of the waveguide x0 is −120 mm; the width of GIMs d is 1.5 mm the working wavelength λ is 37.5 mm (the working frequency is 8 GHz); and the range of index profile is from 1 to 17. Similar phenomenon happens for a transverse magnetic (TM) mode, as shown in Fig. 1d,e. The point source is a numerical setup with Hz=1 (A/m) at a tiny circular boundary (see the black circles in Fig. 1d,e). Figure 1d is the case without GIMs, whereas Fig. 1e is that with GIMs. Moreover, the power propagates only to the +x direction.

By carefully inspecting the field patterns of Fig. 1c,e, it is clearly seen that the EM wave radiating from the source propagates along the − x direction for a distance, before it is blocked at some position and comes back in the +x direction (a U-turn behaviour). For the EM wave radiating in the +x direction, it will be split into two surface-like waves propagating along the interfaces between GIMs and air, which is also well demonstrated by the plotted power flow of Poynting vectors.

Another interesting finding is the interference between the EM wave coming back from the − x direction after the ‘U-turn’ and the EM wave originally radiating along the +x direction. Hence, one may observe that at some frequencies, where the EM wave from the two directions neutralizes each other, almost all the energy is localized inside the device and transmission at the right port of the waveguide is nearly zero, whereas at some frequencies, they can give rise to constructive interference. In order to demonstrate such an interference effect, we calculate the power transmission at both ports of the waveguide. The frequency dependences are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1a,b. Here all the chosen parameters of the structure are the same as those in Fig. 1. From the transmission curves for both TE and TM modes, it is clear that wave propagating along the − x direction is suppressed and only a little energy leaks out at the left port (see the red line), whereas for the right port, the power transmission oscillates for different frequencies (see the green line), which is stemmed from the interference effect between two components—one from the waves radiating along the +x direction and the other from those radiating along the − x direction with U-turn behaviours. At some particular frequencies, for example at 9.74 GHz for TE mode or 10 GHz for TM mode, the power transmission reaches almost zero. The above two components cancel out each other completely and almost all the energy is localized inside the waveguide. To better visualize the effect, we plot the amplitude of the electric field for TE mode at 9.74 GHz in Supplementary Fig. S1c, and the amplitude of the magnetic field for TM mode at 10 GHz in Supplementary Fig. S1d. The amplitudes at both ports for the two modes are very weak, and most of the energy is localized inside the structure.

It is noted that the above working frequency is not below the cutoff frequency of TE modes (which is fc=c/(2(w+2d))=5.88 GHz for the waveguide structure without GIMs and 2 GHz for the waveguide structure with GIMs replaced by a dielectric of refractive index 17). Therefore, the reason why the waves stop at some position and come back to the +x direction is not because of the stop band of the waveguide structure. In fact, we know that for TM modes, there is no cutoff frequency for the same structure, which again shows that the above asymmetric propagation comes from unknown reasons yet to be further explored.

Now, let us try to understand the interesting physics behind this concept. Recently, the concept of phase discontinuity is introduced to control the propagations of EM wave using metasurface consisting of sub-wavelength metal antennas or GIMs21,22,23. If d<<λ and d<<w, we can regard the two slabs of GIMs here as metasurfaces23. In the above cases, λ=20d, w=15d The index profile of equation (1) provides an approximate linear function of phase shifts: ϕ(x)=ϕ0+κ(x−x0), where ϕ0 is the initial phase. The EM wave propagates through the GIMs and is reflected by the PEC walls and finally propagates across the interface, causing a gradient phase shift along the x direction. Such a gradient phase shift along the interface leads to an additional linear momentum,

for each part of the EM wave across the upper or lower metasurface. Here the direction of κ is set along the – x direction. First, we would like to visualize the physics for the asymmetric propagation of light within the metasurface waveguide using a geometric optics approach (Fig. 1a). The EM waves (now rays) coming from the point source first radiate in both directions. For the +x direction, after the rays impinge the upper PEC wall, they will not propagate according to the conventional reflection law  (as shown by red dashed line) but propagate according to the generalized reflection law

(as shown by red dashed line) but propagate according to the generalized reflection law  (as shown by red solid line) because the additional momentum should be taken into account to maintain momentum conservation21. Here we define the +x direction to be positive for wave vectors. Thus, we can see that the reflected angle becomes larger than the incident angle. After the reflected rays propagate and impinge the lower PEC wall, the reflected angle becomes even larger. Consequently, we can predict that after several times of reflection, the rays (or waves) propagating along the +x direction will be converted into surface waves propagating along the interfaces between metasurfaces and air when

(as shown by red solid line) because the additional momentum should be taken into account to maintain momentum conservation21. Here we define the +x direction to be positive for wave vectors. Thus, we can see that the reflected angle becomes larger than the incident angle. After the reflected rays propagate and impinge the lower PEC wall, the reflected angle becomes even larger. Consequently, we can predict that after several times of reflection, the rays (or waves) propagating along the +x direction will be converted into surface waves propagating along the interfaces between metasurfaces and air when  (N is positive integer presenting the reflection time). However, it is completely different for rays propagating along the − x direction. When they impinge the upper PEC wall, the reflected rays will not propagate according to the conventional reflection law

(N is positive integer presenting the reflection time). However, it is completely different for rays propagating along the − x direction. When they impinge the upper PEC wall, the reflected rays will not propagate according to the conventional reflection law  (as shown by black dashed line) but will propagate according to the generalized reflection law

(as shown by black dashed line) but will propagate according to the generalized reflection law  (as shown by black solid line). In this way, the reflected angle becomes smaller than the incident angle. After several times of reflection, the reflected angle becomes smaller and smaller. Hence, as long as N is large enough, the sign of

(as shown by black solid line). In this way, the reflected angle becomes smaller than the incident angle. After several times of reflection, the reflected angle becomes smaller and smaller. Hence, as long as N is large enough, the sign of  will be changed from ‘−’ to ‘+’. It means that the rays (or waves) propagating along the − x direction come back. Thus, following the same physics of rays (or waves) propagating along the +x direction, the rays (or waves) coming back are finally converted into surface waves, thereby interfering with those originally propagating along the +x direction. Therefore, the total effect of EM wave inside the waveguide with metasurfaces is that it can only propagate along one direction.

will be changed from ‘−’ to ‘+’. It means that the rays (or waves) propagating along the − x direction come back. Thus, following the same physics of rays (or waves) propagating along the +x direction, the rays (or waves) coming back are finally converted into surface waves, thereby interfering with those originally propagating along the +x direction. Therefore, the total effect of EM wave inside the waveguide with metasurfaces is that it can only propagate along one direction.

Physics of asymmetric propagation using dispersion analysis

The above explanation provides a simple physics picture behind this asymmetric transmission phenomenon. However, in order to explain the underlying physics in a quantitative manner, we would next examine the physics using the wave optics approach. The asymmetric propagation behaviour of the waveguide can be best described by its waveguide modes and the associated dispersion relation. We numerically calculate the power transmission at one port (the output port) when the EM wave is incident from the other port (the input port) in the x direction. For TE mode, the first mode is coupled into the waveguide, whereas for TM mode, the zeroth mode is coupled into the waveguide. In Fig. 2a, the black curve shows the power transmission at different frequencies for the waveguide without GIMs. When the GIMs are added, high transmission (~80% of above one, denoted by the green curve) can be achieved if the input energy of the EM wave from the left port is the same. The difference from unity is mainly stemmed from the mismatched impedances at the interfaces between the waveguide and the wave coupler instead of material loss. However, for the incident EM wave from the right port, it is clearly seen that the calculated transmission (shown by the red curve) is very low for a broadband of frequencies from 7 to 13 GHz, which demonstrates significantly asymmetric transmission with difference over 20 dB in the two directions. For the same device, the asymmetric transmission also happens for TM mode, as shown in Fig. 2b. For the incident EM wave from right, the calculated transmission is also nearly zero (denoted by the red curve), whereas for the incident EM wave from left, the power transmission (denoted by the dashed green curve) almost reaches that of the waveguide without GIMs (denoted by the black curve). The reason for this is that for TM mode there is no cutoff frequency, and the zeroth mode supported in the waveguide is mainly in the x direction; therefore, the power of the zeroth mode can be perfectly coupled into the left port of the waveguide, leading to high transmission as the case without GIMs.

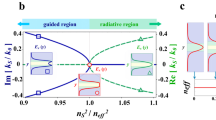

(a,b) The calculated power transmission for TE and TM modes. The black curves are for the waveguide system without the GIMs. The green curves are for the system with the GIMs and with an input from the left port. The red curves are for the system with the GIMs and with an input from the right port. The power transmission is calculated by integrating the Poynting vector along the cross-section of the output port. The width of the waveguide couplers set beside is the same as the width of the core medium of the waveguide, 22.5 mm. (c,d) The simulated Ez field distribution for the EM wave incident from left and right at 8 GHz, respectively. Ez in c and d is in units of V m−1. The dashed blue line denotes the position where the wave stops. The arrows in c and d show the propagation directions and the U-turn behaviours of the waves. (e) The dispersion relations for TE mode but with the GIMs replaced by five kinds of dielectrics, whose refractive indices are related to five different positions of the GIMs. From left to right, the plots correspond to refractive indices 1, 8, 11, 14 and 17. The black dashed lines are the light lines. The red dashed lines indicate the working frequency of (c) at which different waveguide modes are indicated by the arrows and numbered by capital letters with a number relating to the bands. The inset in the middle panel is a magnified plot for a band region indicated by a dashed circle. (f) The mode profiles of the electric field Ez for the corresponding waveguide modes as shown in (e) at the working frequency. The unit of Ez is V m−1. The unit cell is l =25.5 mm.

To show the asymmetric transmission more vividly, the field patterns for TE mode are calculated and plotted in Fig. 2c,d at the frequency 8 GHz. Figure 2c is the field pattern for the wave incident from left, whereas Fig. 2d is that for wave from right. For TM mode, similar effect happens (see Supplementary Fig. S4 and Supplementary Note S2).

In fact, the band structures of the proposed device reveal the above asymmetric propagation effect more accurately than that from geometric optics. The geometric optics only gives a heuristic description. We notice that the band structures of the waveguide with GIMs are difficult to figure out. However, if we replace the GIMs with a kind of dielectric with a constant refractive index, the dispersion relations of the waveguide can be calculated analytically (for details, see Supplementary Note 1). Therefore, we calculate five dispersion relations for five kinds of dielectrics attached to the waveguide and plot them in Fig. 2e. Their refractive indices are related to five different positions of the GIMs, which are 1, 8, 11, 14 and 17. In particular, n=1 and n=17 are related to the left and right ports of the waveguide, respectively; n=11 is related to the approximate position (see the vertical blue dashed line in Fig. 2d) where the incident EM wave (of frequency 8 GHz) from right is blocked.

Now we come to explain the phenomena using the above dispersion relations. In Fig. 2c, when the EM wave is incident from the left port and reaches the interface between the wave coupler and the waveguide, it will be coupled as the first mode (m=1) as shown in the first plot in Fig. 2e. After that, it will be gradually converted into surface waves because the branch of the first mode goes below the light line when the refractive indices of the dielectrics increase (see in plots 2–5 in Fig. 2e). For the incident wave from the right port, when it reaches the interface between the wave coupler and the waveguide, it will first be coupled as the third mode (m=3), as shown in the fifth plot in Fig. 2e. Afterwards, the EM wave propagates and keeps the third mode unchanged until it is blocked at the position where the refractive index is about 11. When we look at the dispersion relation at this position, as shown in the third plot in Fig. 2e, we find that the working frequency is just related to the bottom of the third mode. Therefore, the EM wave is either changed into the first/second mode and continues to propagate in the – x direction (as shown in the first and second plots in Fig. 2e, there is no real solution for the fourth mode) or is reflected and propagates in the +x direction as the same mode (the third mode). If we examine the electrical field pattern carefully, we will find that most of the waves are reflected. Only a little energy is changed into the first/second mode and it leaks out to the – x direction. For example, we plot the same field pattern but with a colour bar of a much smaller range in Supplementary Fig. S3b, where we find only a little energy leaking out, mainly as the first mode (m=1). However, compared with the amplitude of the incident field, the leaked wave can be almost neglected. For instance, when we plot the electric field along the middle plane (the horizontal dashed line in Supplementary Fig. S3a) of the waveguide in Supplementary Fig. S3c, the oscillations of the leaked wave at the left part is much smaller than those of the incident wave at the right part of the waveguide structure (about 1/30 if we magnify the part near the stopping position as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3d). In this way, the EM wave from the right port is blocked at the position where n=11 and shows an U-turn behaviour later.

For details, we plot the waveguide modes at the five positions to demonstrate the evolution of modes in Fig. 2f. Comparing the simulations in Fig. 2c,d and the mode profiles in Fig. 2f, we can clearly observe that, when EM wave is incident from the left, it is coupled to the first mode A1. When it reaches the position where the index is 8, it is still the first mode B1. Then it will be gradually converted into surface wave with the first mode, as shown in C1. The second mode C2, however, is not excited out here. After this position, the modes are unchanged, keeping the first modes with surface waves, as shown in Fig. 2c. We do not show the mode profiles D1 and E1 at positions with indices 14 and 17, as we cannot see the cross points of the first modes from the current dispersions (the wave vectors are too large here). For the right incident EM wave, however, the modes are all third modes, as shown by E3 and D3. Therefore, the evolution of the waveguide modes for EM wave coupled from left and from right is now very clear to us—that is, A1–B1–C1–D1–E1 and E3–D3, respectively. The results are consistent with the field pattern in Fig. 2c,d.

For TM mode, similar physics can also be found from the dispersion relations, resulting in the asymmetric transmission of light (see Supplementary Note 2).

In fact, the only necessary condition for asymmetry propagation is that we have two slabs of GIMs as the cladding layers of the waveguide, whose refractive index increases along the x direction and the change happens at least in a distance larger than a wavelength. This allows us to make a more general and robust version. If we replace the metasurfaces with GIMs in the above heuristic geometric model, we will find that the phase shift is no longer a linear function of x, as the EM wave inside the GIMs is not a plane wave along the y direction and its wave vector is changed gradually as propagating. In other words, the refractive index profile should not be necessarily a linear function of x but just a monotonously increasing function of x.

Microwave implementation of asymmetric propagation

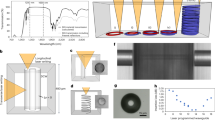

The proposed device here can work in principle from microwave frequencies all the way to optical frequencies as long as the materials with required refractive index profile can be fabricated. It is noted that in the above discussions, the materials with the special refractive index profile is a bit challenging to realize using the current metamaterial techniques. In addition, materials with high permeability at optical frequencies would violate the Landau–Lifshitz permeability argument31. Fortunately, we could design a reduced version alternatively by increasing the width of the metasurfaces, and setting μ(x)=1, ε(x)=(1+κ(x−x0)/2k0d)2. We numerically find that the asymmetric transmission still happens for the reduced version (see Supplementary Note 3). Figure 3a–c is a picture of the fabricated sample, in which the parameters of the reduced device are set as follows: w=22.5 mm, d=7.2 mm, L=212.4 mm, κ=0.2k0 and x0=0, with the permittivity ranging from 1 to 16 and μ=1. The GIM regions are actually discretized into four parts, each with different substrate materials, whose ε is 2.2, 3.5, 7.5 and 16, respectively, and corresponding to the regions I, II, III and IV in Fig. 3a. By drilling holes with different sizes, we can obtain the above required refractive index profile along the x direction (see Supplementary Note 4).

(a) The fabricated sample (top view). The unit cell of the fabricated metamaterial is magnified as well. (b,c), The configurations for the TE modes to be coupled from left and right, respectively. (d,e), The simulated and scanned electric field patterns (|Ez|) at 8 GHz corresponding to the configurations in (b). (f,g) The simulated and scanned electric field patterns (|Ez|) at 8 GHz corresponding to the configurations in (c). |Ez| in d–g are dimensionless with each normalized to its maximum value. The arrows in d–g show the propagation directions and the U-turn behaviours of the waves. (h) The power transmission at different frequencies for different configurations. The solid lines are numerical results, whereas the data points are measured results. The curve in green and the green data points are for wave incidence from the left, whereas those in red are for wave incidence from the right. The curve in black and the black data points are for the configuration without GIMs.

First, we scanned the electric field patterns for two cases (the simulated patterns are shown together). One is for a TE mode coupled from the left port (see Fig. 3b), and the field patterns are plotted in Fig. 3d (simulation) and 3e (measurement). The wave propagates to the +x direction and is smoothly transferred into surface waves. The other is for a TE mode coupled from the right port (see Fig. 3c), and the field patterns are plotted in Fig. 3f (simulation) and 3g (measurement). The EM wave stops at some position after propagating to the − x direction and comes back again to the +x direction before being converted into surface waves. Both the above two cases are obtained at the frequency 8 GHz and show the asymmetric propagation of EM waves very clearly as proposed in the above theoretical sections. During the measurements, we have to add the wave-absorbing materials at the right port to eliminate the scattering caused by the impedance mismatching at the interfaces of the GIM regions and air. Then, we measured the power transmission for the above two TE modes incident and coupled in the ±x direction at different frequencies, as shown in Fig. 3h. The transmission curve for the wave coupled from the left is denoted by the green triangular experiment data points. The transmission is close to the waveguide structure without GIMs (the black plus-sign experiment data points). The transmission curve for the wave coupled from the right is denoted by the red star experiment data points, which is reduced to about −15 dB from 7 to 11 GHz. We also plot the related transmission curves from numerical simulations (denoted by solid lines in the same colours correspondingly) for comparison. We note that it is difficult to measure the power transmission directly using a point detector. Instead, we measure |Ez|2 (similar to those in Fig. 3d–g) and integrate it along the cross-section of the output port. Such a value is proportional to the energy. By normalizing it to the input power, we can obtain the power transmission curves for different configurations. When we scanned the field patterns, a 1-mm air gap between the samples and the upper aluminium plate is left for the detector to insert. Such a gap results in some energy leaking during the measurement. That is why the fields in the GIM regions are enhanced, causing some inconsistencies with the simulated ones. However, the asymmetry propagation is still well demonstrated from the field patterns. For the measurements of the transmission curves, we close the gap and measure the electric fields at the ports, therefore showing higher accuracy and more consistency with the simulated results. The asymmetry propagation happens for a very broadband of spectrums.

Discussion

We have proposed and fabricated a simple waveguide device with asymmetric propagation effect. The structure is simple to fabricate as only dielectrics are needed and works well for a broadband of frequencies. Most importantly, the device shows very good performance of asymmetric transmission for both TE and TM modes, which can be extended to three-dimensional photonic structure (see Supplementary Note 5). Although only the experiment at the microwave region is shown in this Article, we expect our device can be realized at THz or even optical frequencies in future, considering the recent progress of invisibility cloaks32,33,34. However, we note that the asymmetric transmission assisted with mode conversion demonstrated here is different from the asymmetric transmission of the same mode along a waveguide arising from non-reciprocity.

Methods

Theory and simulation

The field patterns in Figs 1b–e, 2c,d,f and 3d,f are obtained using the finite element solver COMSOL Multiphysics. The power transmission in Fig. 2a,b (and a part in Fig. 3h) is also numerically calculated using COMSOL Multiphysics. The power transmission is calculated by integrating the Poynting vectors along the cross-section near the output port of the waveguide, and normalized to the incident power. In all calculations, the scattering boundaries are set for both sides of the waveguide.

Sample fabrication

The materials in regions I, II, III and IV are fabricated by drilling different sizes of holes in four pieces of different dielectric plates35, whose permittivities are 2.2, 3.5, 7.5 and 16, respectively. The detailed sizes of the holes in each part are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Experimental setup

The functionalities of the above waveguide structure can be characterized by testing the sample of finite height inside a parallel-plate waveguide system36. The system consists of two flat conducting plates spaced 6 mm apart, whereas inside the gap the TE mode is dominant. The lower plate rests on the translational stage and is movable along two orthogonal directions. Waveguide structure is located at the lower plate. The probing coaxial detects the electric field distribution inside the gap between the sample and the upper plate via a small hole in the upper plate. In order to detect the E-field on the GIMs, a tiny hole is drilled in the upper plate of the parallel-plate waveguide system and inserted into the hole of the coaxial, which has an inner conductor (<1 mm) naked and extruded into the air gap between the sample and the upper plate. The probe (the inner conductor of the coaxial) is directing the z direction to measure the Ez component. In the measurement, we scan the region with the spatial resolution 1 mm × 2 mm and record the signal received by the probing coaxial at every spatial point with a microwave network analyser. Two machined aluminium blocks are used as the PEC boundaries and are fixed on the lower plate together with the sample, as shown in Fig. 3a. In our experiments, both the aluminium blocks and the sample are 5 mm high. To excite a TE wave in the source, a X-band coaxial-to-waveguide adapter is employed. Such an adapter is the standard microwave waveguide component, with one end being coaxial interface and the other end being rectangular waveguide interface for launching TE modes (http://www.atmmicrowave.com/wave.html). In our experiments, the adapter is fixed to the edge of the lower plate of the parallel-plate waveguide system and its top cover is removed to facilitate the movement of the lower plate with respect to the upper plate, which is big enough to cover the adapter and the GIMs during the movement.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Xu, Y. et al. Broadband asymmetric waveguiding of light without polarization limitations. Nat. Commun. 4:2561 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3561 (2013).

References

Yu, Z. F. & Fan, S. H. Complete optical isolation created by indirect interband photonic transitions. Nat. Photon. 3, 91–95 (2009).

Lira, H., Yu, Z. F., Fan, S. H. & Lipson, M. Electrically driven nonreciprocity induced by interband photonic transition on a silicon chip. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 033901 (2012).

Bi, L. et al. On-chip optical isolation in monolithically integrated non-reciprocal optical resonators. Nat. Photon. 5, 758–762 (2011).

Espinola, R. L., Izuhara, T., Tsai, M. C., Osgood, R. M. & Dötsch, J. H. Magneto-optical nonreciprocal phase shift in garnet/silicon-on-insulator waveguides. Opt. Lett. 29, 941–943 (2004).

Levy, M. Nanomagnetic route to bias-magnet-free, on-chip Faraday rotators. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 22, 254–260 (2005).

Zaman, T. R., Guo, X. & Ram, R. J. Faraday rotation in an InP waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 023514 (2007).

Dötsch, H. et al. Applications of magneto-optical waveguides in integrated optics: review. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 22, 240–253 (2005).

Soljaic, M., Luo, C. Y., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Fan, S. H. Nonlinear photonic microdevices for optical integration. Opt. Lett. 28, 637–639 (2003).

Gallo, K., Assanto, G., Parameswaran, K. R. & Fejer, M. M. All-optical diode in a periodically poled lithium niobate waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 314–316 (2001).

Fan, L. et al. An all-silicon passive optical diode. Science 335, 447–450 (2012).

Haldane, F. D. M. & Raghu, S. Possible realization of directional optical waveguides in photonic crystals with broken time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 013904 (2008).

Fedotov, V. A. et al. Asymmetric propagation of electromagnetic waves through a planar chiral structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 167401 (2006).

Fedotov, V. A., Schwanecke, A. S., Zheludev, N. I., Khardikov, V. V. & Prosvirnin, S. L. Asymmetric transmission of light and enantiomerically sensitive plasmon resonance in planar chiral nanostructures. Nano Lett. 7, 1996–1999 (2007).

Schwanecke, A. S. et al. Nanostructured metal film with asymmetric optical transmission. Nano Lett. 8, 2940–2943 (2008).

Drezet, A., Genet, C., Laluet, J. Y. & Ebbesen, T. W. Optical chirality without optical activity: how surface plasmons give a twist to light. Opt. Exp. 16, 12559–12570 (2008).

Zhukovsky, S. V., Novitsky, A. V. & Galynsky, V. M. Elliptical dichroism: operating principle of planar chiral metamaterials. Opt. Lett. 34, 1988–1990 (2009).

Singh, R. et al. Terahertz metamaterial with asymmetric transmission. Phys. Rev. B 80, 153104 (2009).

Plum, E., Fedotov, V. A. & Zheludev, N. I. Planar metamaterial with transmission and reflection that depend on the direction of incidence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 131901 (2009).

Menzel, A. et al. Asymmetric transmission of linearly polarized light at optical metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 253902 (2010).

Mutlu, M., Akosman, A. E., Serebryannikov, A. E. & Ozbay, E. Diodelike asymmetric transmission of linearly polarizedwaves using magnetoelectric coupling and electromagnetic wave tunneling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 213905 (2012).

Yu, N. et al. Light propagation with phase discontinuities: generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science 334, 333–337 (2011).

Ni, X., Emani, N. K., Kildishev, A.,V., Boltasseva, A. & Shalaev, V. M. Broadband light bending with plasmonic nanoantennas. Science 335, 427 (2012).

Sun, S. L. et al. Gradient-index meta-surfaces as a bridge linking propagating waves and surface waves. Nat. Mater. 11, 426–431 (2012).

Francesco, A. et al. Aberration-free ultrathin flat lenses and axicons at telecom wavelengths based on plasmonic metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 12, 4932–4936 (2012).

Chen, X. et al. Dual-polarity plasmonic metalens for visible light. Nat. Commun. 3, 1198 (2012).

Kildishev, A. V. et al. Planar photonics with metasurfaces. Science 339, 1289–1289 (2013).

Yin, X. et al. Photonic spin hall effect at metasurfaces. Science 339, 1405–1407 (2013).

Lin, J. et al. Polarization-controlled tunable directional coupling of surface plasmon polaritons. Science 340, 331–334 (2013).

Huang, L. et al. Helicity dependent directional surface plasmon polariton excitation using a metasurface with interfacial phase discontinuity. Light Sci. Appl. 2, e70 (2013).

Balthasar Mueller, J. P. & Capasso, F. Strong asymmetric surface plasmon polariton emission by a dipole emitter near a metal surface. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1304.2403 (2013).

Merlin, R. Metamaterial and the Landau-Lifshitz permeability argument: large permittivity begets high-frequency magnetism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1693–1698 (2009).

Schurig, D. et al. Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies. Science 314, 977–980 (2006).

Valentine, J., Li, J., Zentgraf, T., Bartal, G. & Zhang, X. An optical cloak made of dielectrics. Nat. Mater. 8, 568–571 (2009).

Ergin, T., Stenger, N., Brenner, P., Pendry, J. B. & Wegener, M. Three-dimensional invisibility cloak at optical wavelengths. Science 328, 337–339 (2010).

Mei, Z. L., Bai, J. & Cui, T. J. Gradient index metamaterials realized by drilling hole arrays. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 43, 055404 (2010).

Justice, B. J. et al. Spatial mapping of the internal and external electromagnetic fields of negative index metamaterials. Opt. Express 14, 8694–8705 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation of China for Excellent Young Scientists (grant no. 61322504), the Foundation for the Author of National Excellent Doctoral Dissertation of China (grant no. 201217), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 11004147, 11104196 and 11104198), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant nos. BK2010211 and BK2011277), the State Key Program for Basic Research of China (grant no. 2012CB921501), the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET). J.L. would like to thank the support from the GRO program of Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology for the work and the student visit. We would like to thank Profs. T. Tyc, Z. Hang and W.X. Lu for their helpful discussions. H.C. would like to thank Winsley Yang's effort to polish the English.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X., J.L. and H.C. conceived the idea. Y.X. and J.L. performed the initial modelling. Y.X. and Y.L. performed the theoretical calculations and the numerical simulations. C.G. and B.H. fabricated the samples and performed the experimental measurements. J.L. supervised the initial stage. B.H. supervised the experimental part. H.C. supervised the whole project. Y.X. and H.C. wrote the manuscript, all the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S8, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Notes 1-5 (PDF 1854 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Gu, C., Hou, B. et al. Broadband asymmetric waveguiding of light without polarization limitations. Nat Commun 4, 2561 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3561

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3561

This article is cited by

-

Implementing fractional Fourier transform using SH0 wave computational metamaterials in space domain

Science China Technological Sciences (2021)

-

Wideband Miniaturized Design of Complementary Spoof Surface Plasmon Polaritons Waveguide Based on Interdigital Structures

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Lithography-Free Planar Band-Pass Reflective Color Filter Using A Series Connection of Cavities

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Using liner surface modes in acoustic ducts to make obstacles reflectionless

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Design and analysis of gradient index metamaterial-based cloak with wide bandwidth and physically realizable material parameters

Applied Physics A (2018)