Abstract

Stable nitroxides (nitroxyl radicals) have many essential and unique applications in chemistry, biology and medicine. However, the factors influencing their stability are still under investigation, and this hinders the design and development of new nitroxides. Nitroxides with tertiary alkyl groups are generally stable but obviously highly encumbered. In contrast, α-hydrogen-substituted nitroxides are generally inherently unstable and rapidly decompose. Herein, a novel, concept for the design of stable cyclic α-hydrogen nitroxides is described, and a proof-of-concept in the form of the facile synthesis and characterization of two diverse series of stable α-hydrogen nitroxides is presented. The stability of these unique α-hydrogen nitroxides is attributed to a combination of steric and stereoelectronic effects by which disproportionation is kinetically precluded. These stabilizing effects are achieved by the use of a nitroxide co-planar substituent in the γ-position of the backbone of the nitroxide. This premise is supported by a computational study, which provides insight into the disproportionation pathways of α-hydrogen nitroxides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persistent nitroxides have intriguing structural and chemical properties1,2,3 and possess a multitude of highly important applications, such as oxidation catalysts4,5,6,7, reagents in living polymerization reactions8, spin probes in biology9, radical traps in mechanistic investigations, spin trapping agents, medicinal agents10,11 and in materials chemistry12. Designing and preparing stable nitroxides, as well as predicting their properties, remains an important challenge that must be met through a combination of computational methods and creativity12. Most research has been conducted on the archetypical nitroxide TEMPO ((2,2,6,6-tetramethyl piperidin-1-yl)oxyl, Fig. 1) and structurally related compounds. Given these factors, the development of new classes of nitroxides is an enticing and a superbly challenging goal13.

(a,b) Avoiding the optimal 90° dihedral angle for hydrogen atom abstraction (as in b versus a). (c) Impedement of the disproportionation of 15 to nitrone 16 and hydroxylamine 17 through predominance of a conformer in which the R4 of two opposing radicals would sterically repulse each other and in which incipient A(1,3) strain would kinetically disfavour nitrone formation. These three kinetically stabilizing effects are proposed to be enhanced by placing a sterically hindered R5 substituent on the backbone of structure 15 that will dispose the R4 group out of the naphthalene/N–O plane, thus forcing the α-hydrogen atom closer to the plane of the N–O. See text for discussion.

TEMPO (3) is a shelf-stable compound and is the catalyst of choice in industry14 as well as in academia for the oxidation of primary alcohols to aldehydes1,2,3,4,5,6,7. It has many applications in evaluating radical formation in biological tissues15,16 and is also the trapping agent of choice in mechanistic investigations of chemical processes when a radical intermediate is suspected17,18. Conjugates of TEMPO and other nitroxides are also being evaluated for various medicinal uses10,11. Despite its popularity, it suffers from several shortcomings. For example, it often fails to catalyse the oxidation of secondary or hindered alcohols to carbonyl compounds and is a poor catalyst for polymerization of non-styrenic monomers. This is, at least in part, due to the four methyl groups adjacent to the reactive locus: the nitroxyl moiety. Since most known cyclic nitroxides conserve the four methyl groups flanking the radical function, the preparation of cyclic nitroxides with other substitution patterns would be highly desirable. In addition, chiral nitroxides would be desirable both for catalytic as well as biological applications.

One avenue of investigation for developing more active and tuneable systems would be to reduce the steric hindrance by replacing one or more of the methyl groups with a hydrogen atom. However, α-hydrogen-substituted nitroxyl compounds are notoriously and inherently unstable, and undergo fast disproportionation in which two radicals react to give one molecule of nitrone and one of hydroxylamine (Fig. 2)19. The magnitude of this challenge was succinctly described in a 2009 review: ‘…nitroxides are prepared by the oxidation of secondary amines that contain no hydrogen atoms on the α-carbons… If the amines carry α-hydrogens, the oxidation products are nitrones, not free-radical nitroxides…’1.

Given their instability, which imposes severe structural design limitations, it is not surprising that examples of α-hydrogen nitroxides are extremely rare. This is especially evident when compared to the development of, for example, amine and phosphine ligands for transition metal catalysis of which many thousands have been developed20. In fact, we are aware of only two successful designs of α-hydrogen nitroxides that have been reported before this work.

More than 40 years ago, Rassat and Dupeyere21 described the first example of bridged bicyclic α-hydrogen nitroxyls, namely 4 and AZADO (5; Fig. 1). These compounds proved to be exceptionally stable. Their stability is believed to be derived from the inability to form a nitrone C=N double bond to the bridgehead—an elegant application of Bredt’s rule22. AZADO (5) has recently been shown to be a powerful oxidation catalyst and is now commercially available because of the efforts of Iwabuchi and co-workers23,24,25, who also reported a number of other nitroxides inspired by the same design concept. Unfortunately, the bridged bicyclic design is not universally applicable. For example, compound 6 reported by Rychnovsky and co-workers26 decomposes rapidly, possibly via C–N bond scission.

The only other reported structural family are a group of acyclic α-hydrogen nitroxides first described in 1996 (refs 27, 28) typified here by the polymerization catalysts TIPNO (7) and SG1 (8)29,30. Many examples conforming to this design have been prepared and successfully applied in living polymerization reactions8; however, we are unaware of any examples of them being used in oxidation chemistry.

These examples, bicyclic and acylic, constitute compelling examples of chemical knowledge-based design overcoming the natural tendency of α-hydrogen nitroxides to decompose. It would be desirable to develop a design that would allow the preparation of monocyclic α-hydrogen nitroxides, both from the basic scientific as well as a practical point of view. One stumbling block to designing new α-hydrogen nitroxides is that there are a few proposed decomposition pathways and there is no consensus as to which one is operative. Ingold and co-workers31 first proposed that α-hydrogen nitroxyls decompose by hydrogen abstraction (that is, disproportionation) to give the isolable nitrones 13 and hydroxylamine 14 (Fig. 2, pathway a). An alternative proposal by Braslau and co-workers19 is that an initial single electron transfer (SET) step takes place to afford an oxoammonium ion 11 and a hydroxylamine anion 12 (Fig. 2, pathway b). The SET may involve the initial formation of a head-to-tail nitroxide dimer 10. Subsequent proton transfer, from 11 to 12, would lead to the observed products (Fig. 2)19. A third possibility31 involving a rearrangement of 10 was ruled out by Braslau and co-workers19 based, inter alia, on thermodynamic and stereochemical considerations. It is not clear which of these mechanisms is operative, and the decomposition mechanism may depend on the structure of the nitroxide in question (see detailed discussion below).

It should be noted that, while oxoammonium cations such as 11 are important species inferred in many catalytic oxidative processes, only a few oxoammonium salts, mainly of TEMPO derivatives, have been isolated as discrete stable materials1,2,3. For fully alkyl-substituted radicals such as 3, it has been shown that decomposition of the oxoammonium salt occurs predominantly via β-deprotonation by a base1,32. For 3, the equilibrium between two nitroxides and the oxoammonium ion and hydroxylamine can also be catalysed by acid1,32. Other fully α-substituted nitroxides with highly sterically demanding flanking groups may also undergo C–N bond scission19.

Herein, a novel design concept based on a combination of stereoelectronic and steric guidelines is presented. A proof-of-concept is provided; it is shown that the design is applicable to two different systems (1 and 2, Fig. 1), and two different examples for each class are given. To the best of our knowledge, this paper constitutes the first example of a stable α-hydrogen piperidin-1-yl-oxy and pyrrolidin-1-yl-oxy nitroxides that are not bicyclic. A computational study that underpins the design principles outlined herein, which may be of broad general interest for the understanding of nitroxides, is also reported.

Results

Design concept

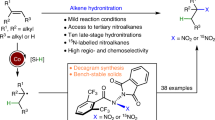

A nitroxyl design along the lines of 15 (Fig. 3) was envisioned that would achieve stability by incorporating a stabilizing substituent R5 on a planar rigid (aromatic) radical backbone. This would lead to an increased activation barrier for disproportionation through a combination of three synergistic effects: (i) The R5 substituent would push the R4 substituent out of the backbone/N–O plane. This would place the R4 substituent in 15 right in the path of approach of a second molecule of 15, sterically inhibiting hydrogen atom abstraction. (ii) Forcing the R4 substituent out of the backbone/N–O plane would lead to compression of the H–C–N–O angle. Angle compression below the optimal 90° angle for hydrogen atom abstraction would increase the energy barrier for hydrogen atom abstraction and nitrone formation. This is due to poor overlap between the C–H σ-bond being broken and the singly-occupied molecular orbital localized on the N–O bond that will be part of the nitrone double bond being formed33; similar considerations have been put forth to explain the stability of the acyclic radicals of the TIPNO (7)/SG1 (8) family based on conformational stabilities27,34,35. (iii) During nitrone formation the R4 substituent would move into the plane of the R5 substituent. This would lead to incipient allylic strain, which would further increase the kinetic barrier to disproportionation irrespective of the mechanism. This conjecture was inspired by the observation that naphthalenes substituted in the 1 and 8 positions with sterically hindered alkyl groups are deformed out of plane, with concomitant loss of aromaticity, due to allylic strain36,37,38,39.

By combining these three diverse and mutually enforcing elements into our design, it was hoped that sufficient kinetic stability of the resulting nitroxides would be achieved to make them stable at ambient temperature. These considerations led to the proposed isoindole structure 1 with a single α-hydrogen and iso-azaphenalene 2 with two α,α′-hydrogen atoms (Fig. 1). It is important to note that simple α-hydrogen nitroxides that do not conform to this design are inherently unstable; for instance, oxidation of piperidine N-oxides with single substituents on C(2) or C(4) results in nitrones40,41,42,43.

In order for any nitroxide design to be attractive from a practical point of view, it is essential that the nitroxide be prepared in high yield and in few synthetic steps. Flexible syntheses of both target structures 1 and 2 have been developed. These syntheses potentially afford access to a wide range of compounds of structures with different substituents (Figs 4 and 5). The syntheses described herein are amenable to gram scale assembly of the nitroxide scaffolds and are highly stereoselective.

Conditions for preparing 29a, R1=Mes, R2=H: mesityl aldehyde (2.5 equiv.), H2N–R2=NH4OAc (1.2 equiv.), EtOH, reflux 2 days, 70% yield, >17:1 d.r. Conditions for preparing 29b, R1=Ph, R2=2,4-dimethoxybenzylamine: 1.1 equiv. 2,4-dimethoxybenzylamine (1.5 equiv.), 6 equiv. benzaldehyde, 2 days, and then toluene sulphonic acid (1 equiv.), dichloromethane, 1 day, 95% yield, >17:1 d.r.

Preparation of stable α-hydrogen nitroxyl radicals

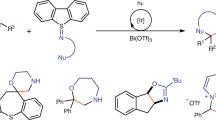

The challenge of synthesizing isoindole structure 1 bearing a single α-hydrogen atom was addressed first (Fig. 4)44. The entire scaffold was assembled in a single synthetic step through the [3+2] cycloaddition of commercially available naphthoquinone 18 with imines 19 (R=mesityl (mes) or naphthyl (naph))45,46. It was found that the initial bisnaphthol product 21a,b is rapidly oxidized to the quinone 22a,b when exposed to air during workup. Quinones 22a and 22b were isolated in 28% and 63% yield, respectively, on a gram scale. It was hypothesized that appending TIPS (tri-iso-propylsilyl) groups to the hydroquinone oxygen atoms, affording OTIPS group, would provide sufficient bulk for stability. To this end, reduction of the quinones with Na2S2O4 followed by treatment of the unpurified hydroquinones with TIPSCl and Hünig’s base led to the stable silylated products 23a and 23b in 51% and 81% yields, respectively. Oxidation using meta-chloroperbenzoic acid (mCPBA) afforded the hydroxylamines 24a and 24b as mixtures with the corresponding nitroxides 25a and 25b respectively. The relative configuration of 24a was determined by X-ray crystallography (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Further oxidation of the hydroxylamine/nitroxide mixtures to the pure radicals using silver oxide or other oxidizing reagents led to decomposition only. However, simply exposing the mixtures to air led to quantitative formation of the desired nitroxides 25a and 25b. These radicals were characterized by electron spin resonance (ESR; Supplementary Fig. 2a,b), infrared and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS). Both radicals are highly stable, remaining unchanged in benzene solution for 2 months without any reduction in ESR signal amplitudes, nor any sign of decomposition products. The radicals can be isolated as solids by simple evaporation of the solvent and kept as solids for at least 2 months. This constitutes a proof-of-principle of our design concept. The ESR spectra have the expected splitting of the N–O system (aN=15.2 G for 25a and aN=13.9 G for 25b, Supplementary Fig. 2a,b) with additional splitting by the adjacent C–H group (aH=21.8 G for 25a and aH=16.3 G for 25b), consistent with simulated spectra. In contrast to the marked stability of 25a and 25b, oxidation of 22a with mCPBA leads to the formation of a nitroxide that decomposes within minutes (see Supplementary Fig. 17 for the ESR of this radical). Thus, the electronic nature of the naphthyl and the steric requirements of the naphthyl R4 substituent in 1 (Fig. 1) are important for stability.

In order to test the generality of the design concept, the study was extended to a second design based on the same principles, but imposing an even greater challenge by having two α-hydrogen atoms—one on either side of the nitroxyl function. This led to the iso-azaphenalene family 2 (Fig. 1)47. This attractive structural backbone can be efficiently assembled in a single synthetic step (Fig. 5). Betti-type reaction of 2,7-naphthalene diol (26) with ammonium acetate or 2,4-dimethoxybenzylamine and variety of aryl aldehydes 28 afforded condensates 29 in excellent yields and with high stereoselectivities (>17:1)48. The aldehyde may be benzaldehyde or derivatives bearing electron-withdrawing or -donating substituents (see Supplementary Methods). Subsequent triflation of 29a (R1=mesityl) proceeded in 94% yield. Stille coupling of the triflate with tetramethyltin gave 30a in 95% yield. Phenyl-substituted 29b (R1=phenyl) was converted into the triflate in 95% yield and methylated in 95% yield. Removal of the 2,4-dimethoxybenzyl protecting group using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) proceeded in 86% yield to give the free amine 30b.

Oxidation of amines 30ab to hydroxylamines 31 ab was carried out using mCPBA. In both cases, the reaction was complete within minutes, yet the stability of the products was remarkably dissimilar. The less sterically congested hydroxylamine 31b was isolated in 40% yield and decomposed after purification to give the nitrone. In contrast, the mesityl derivative 31a was isolated in 70% yield after flash chromatography and proved to be completely stable for more than 9 months as a solid. Both hydroxylamines contained minor amounts of the corresponding nitroxide, observed by ESR. The stable mesityl derivative 31a was characterized by X-ray crystallography (Supplementary Fig. 1) revealing the trans relationship of the two R1 substituents.

Treatment of the hydroxylamine 31b with silver oxide did not result in the isolation of the corresponding radical. Presumably, the transient radical immediately disproportionated. In stark contrast, oxidation of 31a led to the formation of stable nitroxide 32. This radical was isolated in 76% yield after purification by standard flash chromatography with no special precautions and was characterized by HR-MS and ESR. The ESR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 2c) corroborates the structure with splitting of the N–O system (aN=14.5 G) with additional splitting by the two adjacent C–H groups (a2H=17.5 G), consistent with a simulated spectrum. In a benzene solution exposed to air, it has a half-life of 3 days. However, ~2% of the radical still remained in solution (as detected by ESR) after 2 months. In the solid state, the yellow radical is stable for at least 9 months at −15 °C exposed to air without any detectable degradation. The compound possesses slight solvatochromism, appearing orange in some solutions, similar to TEMPO (3).

A TIPS substituted iso-azaphenalene radical 35 was also prepared in this study. Silylation of 29a proceeded smoothly to afford 33 (Fig. 5). Oxidation with mCPBA led to the stable hydroxylamine 34 in 95% yield. Oxidation of 34 with silver oxide gave the free nitroxide 35. The nitroxide was characterized by ESR (Supplementary Fig. 2d), infrared and HR-MS. X-ray diffraction studies of single crystals of 34 showed that the unit cell contained two different structures differing only by the conformation of the TIPS groups (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Interestingly, this is also reflected in the ESR spectrum of 35 (Supplementary Fig. 2d) that clearly shows two radicals, indicating that interconversion is slow on the ESR timescale. The overlapping spectra were deconvoluted using simulated ESR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 16). Partial coalescence of the ESR spectra could be observed by heating the radical to 80 °C in toluene. On cooling to room temperature, the signals again separated, and resolved further by cooling to −20 °C (Supplementary Fig. 16). Nitroxide 35 is stable for at least 9 months as a solid.

The applicability and generality of the design concept have thus been demonstrated by the preparation of two different families of nitroxides (1 and 2) and two stable examples of each family (25a, 25b, 32 and 35). We have shown that OTIPS and methyl groups on the radical backbone stabilize the isoindoline and iso-azaphenalene nitroxides. In contrast, the nitroxide derived by oxidation of quinone 22b decomposes rapidly as do other piperidine hydroxylamines upon oxidation40,41,42,43. The design principles outlined in the introduction were then evaluated, taking advantage of the power of computational studies of the nitroxides already demonstrated to be stable12,49,50.

Computational study into the stability of the nitroxides

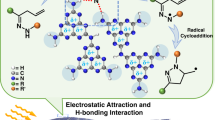

The principal decomposition pathway of α-hydrogen nitroxides is disproportionation to give one molecule of nitrone 13 and one of hydroxylamine 14 as shown in Fig. 2. Three different mechanisms of disproportionation have been proposed, namely: (i) direct hydrogen atom abstraction by one radical from the other to give the products in a single step (Fig. 2, pathway a)31, (ii) head-to-tail dimer formation (10), SET to give one molecule of oxoammonium cation 11 and one of hydroxylamine anion 12 and subsequent proton transfer to give the products (Fig. 2, pathway b)19 and (iii) formation of a head-to-head (O–O) dimer 10 followed by a concerted rearrangement in a second step to give 13 and 14 (ref. 31). The third mechanism has been rejected based on thermodynamical and stereochemical arguments19. However, the other two mechanisms are still under consideration. Indeed, it is possible that different nitroxides may decompose by different mechanisms depending, inter alia, on substituent effects, much like the mechanism of nucleophilic substitution changes from SN2 to SN1 on going from methyl iodide to tert-butyl iodide.

All density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed at the SMD(acetonitrile)-RIJCOSX-DSD-PBEB95/def2-TZVP//DF-PBED3BJ/def2-SVP level of theory (Supplementary Methods, Computational Methods section). On performing the calculations, certain assumptions were made in order to evaluate computationally pliable systems at as high a level of theory as practically possible. The TIPS groups, while hydrolytically stable, result in a large number of degrees of freedom, as noted in the X-ray crystallography of 34 and ESR spectrum of 35 (vide supra), making calculations very demanding. Consequently, it was assumed that calculations on models in which the TIPS groups in radicals 25a and 35 are replaced by the simpler trimethylsilyl (TMS) groups, as in 36 and 37 (Fig. 6), would only have a minor impact on calculated energies and properties but would significantly reduce computational time. The validity of this assumption can be seen in that the overall driving force for the disproportionation of 35 and 37 are within 1 kcal mol−1 of each other (Table 1, column 2). For comparison, the disproportionation of the hypothetical iso-azaphenalene 38 (Fig. 6) of family 2 was also studied. Compound 38 should be unstable based on the experimental observation that the phenyl-substituted 31b spontaneously decomposes. Compound 38 would have a much smaller tendency for incipient allylic strain when transitioning into the corresponding nitrone 13/16 (Fig. 3), less steric hindrance and higher conformational flexibility, thus being able to achieve the orbital overlap required for hydrogen abstraction (Fig. 2, pathway a and Fig. 3a). In contrast, it was not expected to have a dramatically different ability to undergo SET (Fig. 2, pathway b) compared with the other radicals studied.

Importantly, in all cases, the disproportionation is energetically favourable (Table 1, column 2). This shows clearly that the stability of the nitroxides is due to kinetic factors. In contrast, the SET from the radicals to give the oxoammonium 11 and hydroxylamine anion 12 (Fig. 2, pathway b) are all strongly endergonic (Table 1, column 3). Therefore, it is reasonable to rule out the SET pathway, leaving the hydrogen-atom-transfer mechanism (Fig. 2, pathway a) as the most likely mechanism. Further support may be obtained from the plots of the Mulliken charges (Supplementary Figs 3–5) on the fragments during the hydrogen-transfer processes (vide infra). The charge on the hydrogen atom being transferred remains fairly constant at ~0.2e−, while there is not any significant charge accumulation on either fragment.

The direct hydrogen abstraction mechanism (Fig. 2, pathway a) is associated with a large reaction barrier for the stable radicals (Table 1, column 5). The structures of the 32 and 36 radical pair precomplexes, where the oxygen atom of one radical is pointing towards the α-hydrogen of the second, were first optimized (see Table 1, column 4 for energies of formation). The hydrogen-transfer transition states could not be found for these nitroxides, likely because of the flatness of the potential energy surface at the level of theory used for geometry optimizations and because of the strong exergonicity of the disproportionation reaction. Therefore, relaxed scans along the hydrogen abstraction reaction coordinate were performed, fitting the points around the maximum to a third-order polynomial, giving barriers, approximating the transition states, of ΔG‡298≈44.5 and 38.4 kcal mol−1, respectively (Fig. 7 and Table 1, Column 5); these values account for the endergonic formation of the initial radical dimers (Table 1, column 4). Note that the value of 38.4 kcal mol−1 is for the truncated radical 36 where the TIPS of 25a (Fig. 4) is replaced by the smaller TMS (Fig. 6). One would expect that inclusion of TIPS instead of TMS would substantially increase the barrier. In contrast, the related relaxed scan for hypothetical radical 38 revealed a barrier of only ΔG‡298≈6.6 kcal mol−1, indicating that this reaction should proceed very rapidly; in fact, optimization of the radical pair precomplex did not lead to the analogous radical pair but rather hydrogen-bonded nitrone and hydroxylamine products.

In order to verify the electronic state of the radical dimer pair, NEVPT2-CASSCF(8,8) calculations were performed for the radical pair precomplex of 38 for the structure from the relaxed scan where the C–H bond is closest to a typical C–H bond. It is reasonable to assume that the other radicals will have similar behaviour. Unfortunately, the other nitroxides are far too large to be amenable to a CASSCF treatment. These calculations show that the electronic ground state has a closed-shell singlet and the dominant configuration has all electrons paired with a weight of 84% and only small contributions from other configurations. The triplet state is 3.538 eV (3.293 eV for CASSCF) higher in energy. Thus, it is reasonable to treat the radical dimers as closed-shell singlets. If one examines the electronic structure of the precomplex, one notes that there is a hydrogen bond between the oxygen of one nitroxide and the hydrogen being abstracted on the other; the Mayer bond index between these two atoms is 0.33. In forming the hydrogen bond, 0.58 e− of charge (Mulliken partial atomic charges) is transferred from one nitroxide to the other. Nevertheless, this would be consistent with the formation of the hydrogen bond as an integral first step in hydrogen abstraction rather than SET.

A major contribution to the large barriers is unfavourable steric interactions between the two radicals in the radical pairs. Supplementary Table 1 lists the steric interaction energies (ΔEsteric) of the various radical dimers. While 38 shows a very small ΔEsteric, the radical pair of 32 and the disproportionation TS are relatively high in energy. This will have a significant impact on the reaction, making the disproportionation of 32 unfavourable. The same tendency is observed for 36. This is also apparent from the NCI plots (Supplementary Fig. 7). In the NCI plot for 32, there are significantly more weak interactions between the two fragments than in the NCI plot for 38. In addition, from the structures presented, one notes that the radical pair of 32 involves two distinct radicals, whereas the equivalent structure for 38 is an O–H⋯O hydrogen-bonded hydroxylamine–nitrone pair—the disproportionation products (Fig. 2). The equivalent radical pair could not be located for 38, likely because of the low barrier and high exergonicity for disproportionation. In the disproportionation transition state for stable radical 32 (Supplementary Fig. 8), the structure is clearly an early transition state with the C–H bond maintained and with a strongly attractive (blue) O⋯H interaction.

Figure 7 shows changes in the angles between the C–H bond being broken in the disproportionation step and the N–O bond (that is, the φ(H–C–N–O) dihedral angle). As noted above, the ideal situation for hydrogen atom abstraction would be when there is maximal overlap between the C–H bond and the N–O singly-occupied molecular orbital (Fig. 2), since one of the electrons from the C-H bond forms part of the C=N double bond in the nitrone product, the other electron coming from the N–O radical. Thus, this process would be facilitated by a ±90° dihedral angle between these two bonds. This angle (φ) is plotted against the reaction coordinate for each radical in Fig. 7. For the radical monomer of 32, the φ angles are −51° and −69°. As the dimer is formed, the N–O is pushed out of the plane of the naphthalene ring, reaching −110° when the hydrogen is abstracted (Fig. 7c). Similar tendencies are observed for the other radicals. For 38 (Fig. 7b), the φ angles are −42− and −53°. As the dimer is formed, it moves towards −90° as the hydrogen atom is abstracted. This conformationally flexible compound has the lowest barrier of the studied systems. For all the radical dimers, φ is 15–20° from the ideal energy conformer for hydrogen abstraction when the abstraction takes place (Compare Fig. 7 with Figs 2b and 5). For iso-azaphenalene 32, it appears that it is not possible for the C–H bond to move into periplanarity with the N–O orbital and thus when abstraction takes place the barrier is higher than it would be in the ideal case as found in 38 (Fig. 7c). For radical 36, the situation is less clear as φ continues to approach 90° during the hydrogen abstraction (Fig. 7a). This particular effect is likely less important for the stability of this specific radical.

In combination, these results indicate that hydrogen atom abstraction is the active disproportionation mechanism for systems 1 and 2. Ingold and co-workers31,51 in a classical study showed that the decomposition of diethylnitroxide takes place via second-order or pseudo-second-order dependence on the radical concentration, that diamagnetic dimers (presumably of type 10) are formed, and that the rate of radical decay is inversely proportional to solvent polarity (being roughly 30 times faster in iso-pentane than water). This solvent effect would appear to be inconsistent with a mechanism involving the formation of ion pair 11/12 (Fig. 2, pathway b) and could be in line with a hydrogen atom abstraction mechanism (Fig. 2, pathway a). It has been proposed that head-to-tail dimers occur on the path to product formation, specifically as a step preceding ion pair formation. Nonetheless, neither the observation of radical dimers in solution nor the low pre-exponential factors found in Ingold’s Arrhenius analysis imply that dimer 10 is an intermediate on the direct reaction pathway to the nitrone and hydroxylamine (Fig. 2, pathway b) rather than simply a competing equilibrium. Our calculations did not proceed through dimers such as 10, rather at the highest point along the reaction coordinates (Fig. 7 and Table 1), radical⋯radical dimers were observed. Obviously, more work is required to make any definite conclusions, however, based on the present calculations and the earlier observations by Ingold, it is reasonable that the hydrogen atom abstraction mechanism may be the predominant disproportionation pathway in other systems as well.

Nitroxide properties and applications

In order to evaluate the potential of the new radicals in applications such as catalysis, the bond dissociation energies (BDE) and redox potentials52 of the radicals were calculated. The calculated redox potentials of 32, 35–38 obtained are similar to that calculated for TEMPO (Table 2). The ability of the radicals to serve as a catalyst in oxidation reaction might therefore be envisioned.

Indeed, nitroxides 25a, 25b, 32 and 35 are able to reversibly cycle between their reduced (hydroxylamine) and nitroxide states, as shown by their use as a co-catalyst in the aerobic copper-catalysed oxidation of benzyl alcohol using the conditions developed by Hoover and Stahl53. These conditions have been shown to involve the nitroxides alternating between these two oxidation states, and between a copper bound and a free state54. Oxidation of benzyl alcohol using nitroxides 25b, 32 and 35 is complete within 1–2 h at room temperature. For comparison, oxidation using TEMPO, performed in parallel, requires 3 h for complete conversion under the same conditions.

In contrast, nitroxide radical 25a requires heating to 55 °C and 6 h reaction time. This is because of the precipitation of a nitroxide–copper complex at room temperature. Partial dissolution of the precipitate could be observed along with a colour change from green (copper(II)) back to red–brown (copper(I)) at 55 °C. Thus, the reaction time and the temperature required for 25b results from solubility limitations and not reactivity. Less than 10% conversion takes place with CuBr/bipyridine/NMI at 55 °C for 6 h in the absence of a nitroxide.

This study demonstrates the ability of all four radicals to cycle between hydroxylamine and radical oxidation states at least 20 times (that is, with a TON of at least 20). The preliminary results presented here are useful for establishing the potential feasibility and future work on this catalytic system. The nitroxides in this study were studied with stability in mind rather than catalytic activity; however, the data shown in Table 3 indicates that high catalytic efficiencies are possible. Since the syntheses of radicals 1 and 2 (Figs 4 and 5) are highly modular, this allows for the easy preparation of a diverse family of nitroxides in terms of the R1–R5 substituents (Fig. 1). It should therefore be possible to design nitroxides of type 1 and 2 with high catalytic efficiencies. Research in this direction is already underway.

Conclusions

A new concept for the design of α-hydrogen-substituted nitroxides of two distinct structural families—1 and 2—has been developed (Fig. 1). This design is based on the ability of a substituent in the γ position of the radical (R4 in 1 and R6 in 2) to interact with the α substituent, thereby inhibiting disproportionation through a combination of steric and stereoelectronic effects. The compounds prepared are stable for months in the solid form.

The principles outlined and verified experimentally are supported by a thorough computational study. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate in silico the two prevalent mechanisms for nitroxide disproportionation. The hydrogen atom abstraction mechanism proposed by Ingold and co-workers31 was identified as being the most likely mechanism for the decomposition of nitroxides of types 1 and 2. These results may have significance for other α-hydrogen nitroxides. The nitroxides of types 1 and 2 are shown to possess BDE and redox potentials as expected for nitroxides, which indicates that they should be useful in many applications for which nitroxides are suitable. Catalytic proficiency of these compounds is demonstrated in a preliminary study.

This report constitutes a design concept for cyclic α-hydrogen nitroxides, that is, nitroxides that are not bicyclic like AZADO (5) or acyclic like TIPNO (7). The design principles outlined in this paper are likely not restricted to nitroxides 1 and 2, and may be applied to the preparation of other nitroxides. The novel nitroxides of types 1 and 2 can be prepared in a highly efficient manner and in high yields. The flexibility of the synthesis allows for simple modification of the parent structures for tailored applications. In the present paper, the catalytic activity of the novel nitroxides was demonstrated, proving their ability to cycle between radical and hydroxylamine oxidation states. Since these compounds are chiral, it is especially attractive to consider potential applications in asymmetric catalysis25,26,55 and as probes for biological studies. Indeed, multiple applications in catalysis, biology and medicine may be foreseen; however, this is beyond the scope of the present communication and will form the basis of further reports.

Methods

For general, synthetic and computational methods and characterization data see Supplementary Methods section.

For NMR spectra of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figs 18–67.

For ESR spectra of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figs 2 and 9–17.

Additional information

Accession codes. Accession codes: The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures 24a, 32 and 34 reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1037250, 975284 and 975285. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

How to cite this article: Amar, M. et al. Design concept for α-hydrogen-substituted nitroxides. Nat. Commun. 6:6070 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7070 (2015).

References

Bobbitt, J. M., Bruckner, C. & Merbouh, N. Oxoammonium- and nitroxide-catalyzed oxidations of alcohols. Org. Reactions 74, 103–424 (2009).

Tansakul, C. & Braslau, R. Nitroxides in Synthetic Radical Chemistry Vol. 2 1095–1129John Wiley & Sons Ltd. (2012).

Tebben, L. & Studer, A. Nitroxides: applications in synthesis and in polymer chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 5034–5068 (2011).

Lucio Anelli, P., Biffi, C., Montanari, F. & Quici, S. Fast and selective oxidation of primary alcohols to aldehydes or to carboxylic acids and of secondary alcohols to ketones mediated by oxoammonium salts under two-phase conditions. J. Org. Chem. 52, 2559–2562 (1987).

Wertz, S. & Studer, A. Nitroxide-catalyzed transition-metal-free aerobic oxidation processes. Green Chem. 15, 3116–3134 (2013).

Toledo, H., Pisarevsky, E., Abramovich, A. & Szpilman, A. M. Organocatalytic oxidation of aldehydes to mixed anhydrides. Chem. Commun. 49, 4367–4369 (2013).

Abramovich, A., Toledo, H., Pisarevsky, E. & Szpilman, A. M. Organocatalytic oxidative dimerization of alcohols to esters. Synlett 23, 2261–2265 (2012).

Gigmes, D. & Marque, S. R. A. Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology and Materials Vol. 4, 1813–1850John Wiley & Sons Ltd. (2012).

Yan, G. P., Peng, L., Jian, S. Q., Li, L. & Bottle, S. E. Spin probes for electron paramagnetic resonance imaging. Chin. Sci. Bull. 53, 3777–3789 (2008).

Bi, W. et al. Novel TEMPO-PEG-RGDs conjugates remediate tissue damage induced by acute limb ischemia/reperfusion. J. Med. Chem. 55, 4501–4505 (2012).

Castagna, R. et al. Nitroxide radical TEMPO reduces ozone-induced chemokine IL-8 production in lung epithelial cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 23, 365–370 (2009).

Gryn'ova, G., Barakat, J. M., Blinco, J. P., Bottle, S. E. & Coote, M. L. Computational design of cyclic nitroxides as efficient redox mediators for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 7582–7593 (2012).

Hamada, S., Furuta, T., Wada, Y. & Kawabata, T. Chemoselective oxidation by electronically tuned nitroxyl radical catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 8093–8097 (2013).

Ciriminna, R. & Pagliaro, M. Industrial oxidations with organocatalyst TEMPO and its derivatives. Org. Process Res. Dev. 14, 245–251 (2010).

Ishii, K., Kubo, K., Sakurada, T., Komori, K. & Sakai, Y. Phthalocyanine-based fluorescence probes for detecting ascorbic acid: phthalocyaninatosilicon covalently linked to TEMPO radicals. Chem. Commun. 47, 4932–4934 (2011).

Pattison, D. I., Lam, M., Shinde, S. S., Anderson, R. F. & Davies, M. J. The nitroxide TEMPO is an efficient scavenger of protein radicals: cellular and kinetic studies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 1664–1674 (2012).

Paul, N. D. et al. Metalloradical approach to 2H-chromenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 1090–1096 (2014).

Amos, R. I. J., Gourlay, B. S., Schiesser, C. H., Smith, J. A. & Yates, B. F. A mechanistic study on the oxidation of hydrazides: application to the tuberculosis drug isoniazid. Chem. Commun. 1695–1697 (2008).

Nilsen, A. & Braslau, R. Nitroxide decomposition: implications toward nitroxide design for applications in living free-radical polymerization. J. Polym. Sci., A Polym. Chem 44, 697–717 (2005).

Kamer, P. C. J. & Leeuwen, P.W.N.M.v. Phosphorus(III) Ligands in Homogeneous Catalysis: Design and Synthesis John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (2012).

Dupeyre, R. M., Rassat, A. & Ronzaud, J. Nitroxides. LII. Synthesis and electron spin resonance studies of N,N'-dioxy-2,6-diazaadamantane, a symmetrical ground state triplet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96, 6559–6568 (1974).

Bredt, J. Über sterische Hinderung in Brückenringen (Bredtsche Regel) und über die meso-trans-Stellung in kondensierten Ringsystemen des Hexamethylens. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 437, 1–13 (1924).

Shibuya, M., Tomizawa, M., Suzuki, I. & Iwabuchi, Y. 2-Azaadamantane N-Oxyl (AZADO) and 1-Me-AZADO: highly efficient organocatalysts for oxidation of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 8412–8413 (2006).

Shibuya, M., Tomizawa, M., Sasano, Y. & Iwabuchi, Y. An expeditious entry to 9-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane N-Oxyl (ABNO): another highly active organocatalyst for oxidation of alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 74, 4619–4622 (2009).

Tomizawa, M., Shibuya, M. & Iwabuchi, Y. Highly enantioselective organocatalytic oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols using chirally modified AZADOs. Org. Lett. 11, 1829–1831 (2009).

Graetz, B., Rychnovsky, S., Leu, W.-H., Farmer, P. & Lin, R. C2-Symmetric nitroxides and their potential as enantioselective oxidants. Tetrahedron 16, 3584–3598 (2005).

Reznikov, V. A., Gutorov, I. A., Gatilov, Y. V., Rybalova, T. V. & Volodarsky, L. B. Stable nitroxyl radicals with a hydrogen atom at alpha-carbon atom of nitroxyl group. Russ. Chem. Bull. 45, 384–392 (1996).

Grimaldi, S. et al. Polymerisation in the presence of a beta-substituted nitroxide radical WO 96124620 (1996).

Benoit, D., Chaplinski, V., Braslau, R. & Hawker, C. J. Development of a universal alkoxyamine for "living" free radical polymerizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 3904–3920 (1999).

Benoit, D. et al. Controlled free-radical polymerization in the presence of a novel asymmetric nitroxyl radical. Polym. Prepr. (Am. Chem. Soc. Div. Polym. Chem.) 38, 729–730 (1997).

Adamic, K., Bowman, D. F. & Ingold, K. U. Self-reaction of diethylnitroxide radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 1093–1094 (1970).

Tikhonov, I. V. et al. Effect of the structure of nitroxyl radicals on the kinetics of their acid-catalyzed disproportionation. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 27, 114–120 (2014).

Breuer, E., Aurich, H. G. & Nielsen, A. Nitrones, Nitronates, and Nitroxides New York,Wiley (1989).

Studer, A., Harms, K., Knoop, C., Mueller, C. & Schulte, T. New sterically hindered nitroxides for the living free radical polymerization: X-ray structure of an α-H-bearing nitroxide. Macromolecules 37, 27–34 (2004).

Grimaldi, S., Siri, D., Finet, J. P. & Tordo, P. N-tert-butyl-N-(1-dibenzylphosphono-2,2-dimethylpropyl)nitroxide.. Acta Crystallogr.Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 54, 1712–1714 (1998).

Franck, R. W. & Leser, E. G. 1,8-Di-tert-butylnaphthalenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91, 1577–1578 (1969).

Franck, R. W. & Leser, E. G. Synthesis of 1,8-di-tert-butylnaphthalenes. J. Org. Chem. 35, 3932–3939 (1970).

Anderson, J. E., Franck, R. W. & Mandella, W. L. Peri interactions in some 1,8-di-tert-butylnaphthalene compounds. Rotation and flipping of the tert-butyl groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 4608–4614 (1972).

Aikawa, H., Takahira, Y. & Yamaguchi, M. Synthesis of 1,8-di(1-adamantyl)naphthalenes as single enantiomers stable at ambient temperatures. Chem. Commun. 47, 1479–1481 (2011).

Carruthers, W., Coggins, P. & Weston, J. B. Nitrone cycloadditions: synthesis of (±)-andrachamine. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. 1, 2323–2327 (1990).

Carruthers, W., Coggins, P. & Weston, J. B. Nitrone cycloaddition: an approach to the cyclophane alkaloid (±)-lythranidine. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. 1, 611–616 (1991).

Brandi, A., Cicchi, S., Paschetta, V., Gomez Pardo, D. & Cossy, J. A new nitrone from C2 symmetric piperidine for the synthesis of hydroxylated indolizidinone. Tetrahedron Lett. 43, 9357–9359 (2002).

Moosa, B. A. & Ali, S. A. Regioselective transformation of 6/5-fused bicyclic isoxazolidines to second-generation cyclic aldonitrones. ARKIVOC 132–148 (2010).

Sysoeva, N. A., Sholle, V. D., Rozantsev, E. G. & Buchachenko, A. L. NMR spectra of nitroxyl radicals of the isoindoline series. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Khim. 20, 1716–1717 (1971).

Amornraksa, K., Grigg, R., Gunaratne, H. Q. N., Kemp, J. & Sridharan, V. X=Y-ZH systems as potential 1,3-dipoles. 8. Pyrrolidines and delta-5-Pyrrolines (3,7-Diazabicyclo 3.3.0 Octenes) from the reaction of imines of alpha-amino-acids and their esters with cyclic diploarophiles - mechanism of racemization of alpha-amino-acids and their esters in the presence of aldehydes. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. 1, 2285–2296 (1987).

Szpilman, A. M. & Carreira, E. M. Cycloaddition reactions,. in Silver in Organic Chemistry ed. Harmata M. 43–82John Wiley & Sons Inc. (2010).

Blinco, J. P., McMurtrie, J. C. & Bottle, S. E. The first example of an azaphenalene pro-fluorescent nitroxide. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 4638–4641 (2007).

Foroughifar, N., Mobinikhaledi, A. & Moghanian, H. Simple and efficient procedure for the synthesis of novel 1,3-diphenyl-2-azaphenalene derivatives via one-pot multicomponent reactions. Synth. Commun. 40, 1812–1821 (2010).

Gryn'ova, G., Ingold, K. U. & Coote, M. L. New insights into the mechanism of amine/nitroxide cycling during the hindered amine light stabilizer inhibited oxidative degradation of polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 12979–12988 (2012).

Gryn'ova, G., Lin, C. Y. & Coote, M. L. Which side-reactions compromise nitroxide mediated polymerization? Polym. Chem. 4, 3744–3754 (2013).

Ingold, K. U., Adamic, K., Bowman, D. F. & Gillan, T. Kinetic applications of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. I. Self-reactions of diethyl nitroxide radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 902–908 (1971).

Blinco, J. P. et al. Experimental and theoretical studies of the redox potentials of cyclic nitroxides. J. Org. Chem. 73, 6763–6771 (2008).

Hoover, J. M. & Stahl, S. S. Highly practical copper(I)/TEMPO catalyst system for chemoselective aerobic oxidation of primary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 16901–16910 (2011).

Ryland, B. L., McCann, S. D., Brunold, T. C. & Stahl, S. S. Mechanism of alcohol oxidation mediated by copper(II) and nitroxyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12166–12173 (2014).

Rychnovsky, S. D., McLernon, T. L. & Rajapakse, H. Enantioselective oxidation of secondary alcohols using a chiral nitroxyl (N-oxoammonium salt) catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 61, 1194–1195 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a German Israel Foundation Young Investigator Grant (grant no. I-2234-2067/2009). A.M.S. is the incumbent of the Chaya Career Development Chair.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. and S.B. designed and carried out the experiments. M.A.I. did the DFT calculations and helped to write the manuscript. H.T. participated in designing and carrying out the experiments. B.T. performed the ESR measurements. L.J.W.S., M.B. and N.F. performed the X-ray crystallography. A.M.S. invented the concepts presented here, designed the experiments, supervised the work and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-67, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 5991 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amar, M., Bar, S., Iron, M. et al. Design concept for α-hydrogen-substituted nitroxides. Nat Commun 6, 6070 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7070

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7070

This article is cited by

-

Biological Relevance of Free Radicals and Nitroxides

Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics (2017)

-

N-tert-butylmethanimine N-oxide is an efficient spin-trapping probe for EPR analysis of glutathione thiyl radical

Scientific Reports (2016)