Key Points

-

Viral host jumps can lead to major public health threats. The most recent pandemics were caused by viruses that were transmitted from animal reservoirs to humans, such as influenza A viruses and severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus. Adaptation of the virus to the new host is often cited as the cause of such emergence.

-

Distinguishing the genetic changes that are due to adaptation from those that are due to random events is hard in any biological context; virus host jumps are no exception. We present four different mechanisms by which viruses may emerge in a new host. Although all four mechanisms could produce the same genetic pattern in new hosts, only two are due to adaptation. We illustrate which data need to be collected to distinguish between the four mechanisms.

-

Future risk of viral host jumps to humans could be assessed by genetic surveillance of viruses in reservoir hosts, but only when genetic adaptation is required for a host jump and when precursors of this adaptation can be detected.

-

Bioinformatic analyses of surveillance data are key stepping stones for identifying putative genetic markers of viral adaptation from enormous pools of genetic data. Confirmation of which of these putative markers are due to adaptation requires experimental validation by using reverse genetics and host models from reservoir and new host species, and corroborating results with epidemiological and ecological data.

-

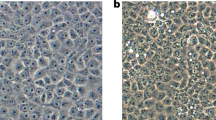

Our review of the current literature on four well-studied viral host jumps shows that research on host-jump processes unfolds in four broad stages: virus sample collection and genetic analysis; experiments in vitro or in cell culture; in vivo experiments in model hosts; and in vivo experiments in natural hosts. We evaluate the issues in using these types of data for validating adaptive hypotheses, and identify opportunities to collect further data that would enable better discrimination among emergence mechanisms.

-

A detailed understanding of viral host jumps and the assessment of future risk requires multidisciplinary research efforts with input from field ecologists, microbiologists, immunologists, epidemiologists, bioinformaticians and evolutionary biologists, and the use of use of diverse approaches (field sampling, laboratory experiments, data analysis and mathematical modelling).

Abstract

Adaptation is often thought to affect the likelihood that a virus will be able to successfully emerge in a new host species. If so, surveillance for genetic markers of adaptation could help to predict the risk of disease emergence. However, adaptation is difficult to distinguish conclusively from the other processes that generate genetic change. In this Review we survey the research on the host jumps of influenza A, severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus, canine parvovirus and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus to illustrate the insights that can arise from combining genetic surveillance with microbiological experimentation in the context of epidemiological data. We argue that using a multidisciplinary approach for surveillance will provide a better understanding of when adaptations are required for host jumps and thus when predictive genetic markers may be present.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

12 October 2010

In the sentence "For example, H5N influenza transmission from avian species to humans has caused 498 cases (294 deaths) in 15 countries worldwide since 2003, but no sustained chains of human–human transmission have been observed66" H5N was corrected to H5N1.

References

Calisher, C. H., Childs, J. E., Field, H. E., Holmes, K. V. & Schountz, T. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 531–545 (2006).

Guberti, V. & Newman, S. C. Guidelines on wild bird surveillance for highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus. J. Wildl. Dis. 43, 29–34 (2007).

Taubenberger, J. K. & Morens, D. M. 1918 influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 15–22 (2006). Review of the 1918 influenza pandemic claiming that an understanding of the historical, epidemiological and biological aspects of the 1918 influenza as well as extensive sampling and sequencing of influenza A strains from animals are necessary to understand the nature of influenza pandemics.

Taubenberger, J. K. et al. Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes. Nature 437, 889–893 (2005).

Smith, G. J. et al. Dating the emergence of pandemic influenza viruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11709–11712 (2009).

Gibbs, M. J. & Gibbs, A. J. Was the 1918 pandemic caused by a bird flu? Nature 440, E8 (2006).

Daszak, P., Cunningham, A. A. & Hyatt, A. D. Wildlife ecology - emerging infectious diseases of wildlife - threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 287, 443–449 (2000).

Dobson, A. & Foufopoulos, J. Emerging infectious pathogens of wildlife. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B Biol. Sci. 356, 1001–1012 (2001).

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993 (2008).

Plowright, R. K., Sokolow, S. H., Gorman, M. E., Daszak, P. & Foley, J. E. Causal inference in disease ecology: investigating ecological drivers of disease emergence. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6, 420–429 (2008).

Woolhouse, M. E. J. & Gowtage-Sequeria, S. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerging Infect. Dis. 11, 1842–1847 (2005).

Williams, G. C. in A Critique of Some Current Evolutionary Thought (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1966).

Gould, S. J. & Lewontin, R. C. The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist programme. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 205, 581–598 (1979).

Nielsen, R. Adaptionism-30 years after Gould and Lewontin. Evolution 63, 2487–2490 (2009). Comment on the difficulties that evolutionary biologists confront when measuring adaptation, emphasizing how these challenges have changed with the increased availability of vast amounts of genetic data and how the data can improve our understanding of evolutionary processes.

Orr, H. A. Fitness and its role in evolutionary genetics. Nature Rev. Genet. 10, 531–539 (2009).

Woolhouse, M. & Antia, R. in Evolution in Health and Disease, 2nd Edition (eds Stearns, S. C. & Koella, J. C.) (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007).

Matthews, L. & Woolhouse, M. New approaches to quantifying the spread of infection. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 3, 529–536 (2005). Review of advances in epidemiological modelling that address disease emergence conditions in the early stages and in small populations.

Messier, W. & Stewart, C. B. Episodic adaptive evolution of primate lysozymes. Nature 385, 151–154 (1997).

Wood, T. E., Burke, J. M. & Rieseberg, L. H. Parallel genotypic adaptation: when evolution repeats itself. Genetica 123, 157–170 (2005). Review of parallel and convergent evolution as signatures of adaptation, drawing from experimentally evolved cases.

Dunham, E. J. et al. Different evolutionary trajectories of European avian-like and classical swine H1N1 influenza A viruses. J. Virol. 83, 5485–5494 (2009).

Liu, W. et al. Molecular epidemiology of SARS-associated coronavirus, Beijing. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1420–1424 (2005). Report of SARS-CoV genetic sequences isolated from patients in Beijing, showing convergent patterns of evolution with viruses isolated in Guangdong province.

Chinese, S. M. E. C. Molecular evolution of the SARS coronavirus during the course of the SARS epidemic in China. Science 303, 1666–1669 (2004).

Zhao, G. P. SARS molecular epidemiology: a Chinese fairy tale of controlling an emerging zoonotic disease in the genomics era. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 362, 1063–1081 (2007). Summarizes the evidence that SARS-CoV emergence was driven by viral adaptation and illustrates how the globally coordinated response to the SARS outbreak was so successful and what methodological insight was gained for future public health emergencies.

Sheahan, T., Rockx, B., Donaldson, E., Corti, D. & Baric, R. Pathways of cross-species transmission of synthetically reconstructed zoonotic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 82, 8721–8732 (2008). Experimental studies of SARS-CoV emergence in which genes from reservoir and new hosts, and from viruses isolated from both hosts, are mixed in chimaeric constructs to test the specificity of particular interactions and the evolutionary potential of the virus.

Song, H. D. et al. Cross-host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2430–2435 (2005).

Li, F. Structural analysis of major species barriers between humans and palm civets for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. J. Virol. 82, 6984–6991 (2008).

Allen, J. E., Gardner, S. N., Vitalis, E. A. & Slezak, T. R. Conserved amino acid markers from past influenza pandemic strains. BMC Microbiol. 9, 77 (2009).

Chen, G. W. et al. Genomic signatures of human versus avian influenza A viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1353–1360 (2006).

Finkelstein, D. B. et al. Persistent host markers in pandemic and H5N1 influenza viruses. J. Virol. 81, 10292–10299 (2007).

Miotto, O., Heiny, A. T., Tan, T. W., August, J. T. & Brusic, V. Identification of human-to-human transmissibility factors in PB2 proteins of influenza A by large-scale mutual information analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, S18 (2008).

Furuse, Y., Suzuki, A., Kamigaki, T. & Oshitani, H. Evolution of the M gene of the influenza A virus in different host species: large-scale sequence analysis. Virol. J. 6, 67 (2009).

Hoelzer, K., Shackelton, L. A., Parrish, C. R. & Holmes, E. C. Phylogenetic analysis reveals the emergence, evolution and dispersal of carnivore parvoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 2280–2289 (2008).

Tamuri, A. U., Dos Reis, M., Hay, A. J. & Goldstein, R. A. Identifying changes in selective constraints: host shifts in influenza. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000564 (2009).

Tang, X. et al. Differential stepwise evolution of SARS coronavirus functional proteins in different host species. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 52 (2009).

Kosakovsky Pond, S. L., Poon, A. F., Leigh Brown, A. J. & Frost, S. D. A maximum likelihood method for detecting directional evolution in protein sequences and its application to influenza A virus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1809–1824 (2008). Summarizes current nucleotide-based bioinformatic methods for identifying adaptation in genetic sequences; develops a protein-based method that circumvents these issues and applies it to identify sites under directional selection in influenza A viruses.

Novella, I. S., Zarate, S., Metzgar, D. & Ebendick-Corpus, B. E. Positive selection of synonymous mutations in vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 1415–1421 (2004).

Pepin, K. M., Domsic, J. & McKenna, R. Genomic evolution in a virus under specific selection for host recognition. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8, 825–834 (2008).

Aragones, L., Guix, S., Ribes, E., Bosch, A. & Pinto, R. M. Fine-tuning translation kinetics selection as the driving force of codon usage bias in the hepatitis a virus capsid. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000797 (2010).

Bahir, I., Fromer, M., Prat, Y. & Linial, M. Viral adaptation to host: a proteome-based analysis of codon usage and amino acid preferences. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, 311 (2009).

van Hemert, F. J., Berkhout, B. & Lukashov, V. V. Host-related nucleotide composition and codon usage as driving forces in the recent evolution of the Astroviridae. Virology 361, 447–454 (2007).

Brower-Sinning, R. et al. The role of RNA folding free energy in the evolution of the polymerase genes of the influenza A virus. Genome Biol. 10, R18 (2009).

Nozawa, M., Suzuki, Y. & Nei, M. Reliabilities of identifying positive selection by the branch-site and the site-prediction methods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6700–6705 (2009).

Hueffer, K., Govindasamy, L., Agbandje-McKenna, M. & Parrish, C. R. Combinations of two capsid regions controlling canine host range determine canine transferrin receptor binding by canine and feline parvoviruses. J. Virol. 77, 10099–10105 (2003).

Sanjuan, R. Mutational fitness effects in RNA and single-stranded DNA viruses: common patterns revealed by site-directed mutagenesis studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365, 1975–1982 (2010).

da Silva, J., Coetzer, M., Nedellec, R., Pastore, C. & Mosier, D. E. Fitness epistasis and constraints on adaptation in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protein region. Genetics 185, 293–303 (2010). Examines genetic interactions and potential evolutionary pathways for HIV adaptation to CXC-chemokine receptor 4 by engineering amino acid mutations alone and in combination and measuring their effects on viral fitness.

Parrish, C. R. et al. Cross-species virus transmission and the emergence of new epidemic diseases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 457–470 (2008). Review of ecological factors and viral adaptations that can lead to cross-species transmission or host jumps.

Wang, L. F. & Eaton, B. T. in Wildlife and Emerging Zoonotic Diseases: The Biology, Circumstances and Consequences of Cross-Species Transmission. 325–344 (Springer-Verlag Berlin, Berlin, 2007).

Reluga, T., Meza, R., Walton, D. B. & Galvani, A. P. Reservoir interactions and disease emergence. Theoretical Population Biology 72, 400–408 (2007).

Pepin, K. M., Samuel, M. A. & Wichman, H. A. Variable pleiotropic effects from mutations at the same locus hamper prediction of fitness from a fitness component. Genetics 172, 2047–2056 (2006).

Gilchrist, M. A. & Sasaki, A. Modeling host-parasite coevolution: a nested approach based on mechanistic models. J. Theor. Biol. 218, 289–308 (2002).

Grenfell, B. T. et al. Unifying the epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of pathogens. Science 303, 327–332 (2004).

Volkov, I., Pepin, K. M., Lloyd-Smith, J. O., Banavar, J. R. & Grenfell, B. T. Synthesizing within-host and population-level selective pressures on viral populations: the impact of adaptive immunity on viral immune escape. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 1311–1318 (2010).

Coombs, D., Gilchrist, M. A. & Ball, C. L. Evaluating the importance of within- and between-host selection pressures on the evolution of chronic pathogens. Theor. Popul. Biol. 72, 576–591 (2007).

Gilchrist, M. A. & Coombs, D. Evolution of virulence: interdependence, constraints, and selection using nested models. Theor. Popul. Biol. 69, 145–153 (2006).

Diekmann, O., Heesterbeek, J. A. & Metz, J. A. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 28, 365–382 (1990).

Roberts, M. G. The pluses and minuses of R0 . J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 949–961 (2007).

Day, T. Virulence evolution and the timing of disease life-history events. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 113–118 (2003).

Gilchrist, M. A., Coombs, D. & Perelson, A. S. Optimizing within-host viral fitness: infected cell lifespan and virion production rate. J. Theor. Biol. 229, 281–288 (2004).

Anderson, R. M. & May, R. M. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1991).

Lloyd-Smith, J. O. et al. Epidemic dynamics at the human-animal interface. Science 326, 1362–1367 (2009). A comprehensive review of the population dynamics of zoonotic infections.

Antia, R., Regoes, R. R., Koella, J. C. & Bergstrom, C. T. The role of evolution in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nature 426, 658–661 (2003). Modelling study examining whether host jumps occur by adaptive mutation in the new host.

Arinaminpathy, N. & McLean, A. R. Evolution and emergence of novel human infections. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 3937–3943 (2009). Discusses epidemiological signs of pathogen adaptation to a new host. Uses a mathematical model that includes within-host evolution and transmission to explore how epidemiological data can be used to monitor the risk of emergence.

Farrington, C. P., Kanaan, M. N. & Gay, N. J. Branching process models for surveillance of infectious diseases controlled by mass vaccination. Biostatistics 4, 279–295 (2003).

Lloyd-Smith, J. O., Schreiber, S. J., Kopp, P. E. & Getz, W. M. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359 (2005).

World Health Organization. Communicable disease profile for Democratic Republic of the Congo (WHO, Kinshasa, 2005).

[No authors listed]. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A/(H5N1) reported to WHO. WHO [online], (2010).

Dufour, A. in Waterborne Zoonoses: Identification, Causes and Control. (eds Cotruvo, J. A. et al.) (IWA Publishing, London, 2004).

Aaskov, J., Buzacott, K., Thu, H. M., Lowry, K. & Holmes, E. C. Long-term transmission of defective RNA viruses in humans and Aedes mosquitoes. Science 311, 236–2238 (2006).

Benmayor, R., Hodgson, D. J., Perron, G. G. & Buckling, A. Host mixing and disease emergence. Curr. Biol. 19, 764–767 (2009).

Holmes, E. C. & Grenfell, B. T. Discovering the phylodynamics of RNA viruses. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000505 (2009). Opinion on the importance of linking ecological, epidemiological and evolutionary data for studying viral evolution.

Gabriel, G. et al. The viral polymerase mediates adaptation of an avian influenza virus to a mammalian host. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18590–18595 (2005). Compares two viral strains, one adapted in birds and one in mice, and identifies specific mutations in the viral polymerase of influenza A strains that enhance polymerase activity and increase virulence in mammalian hosts.

Shinya, K., Watanabe, S., Ito, T., Kasai, N. & Kawaoka, Y. Adaptation of an H7N7 equine influenza A virus in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 88, 547–535 (2007).

Herfst, S. et al. Introduction of virulence markers in PB2 of pandemic swine-origin influenza virus does not result in enhanced virulence or transmission. J. Virol. 84, 3752–3758 (2010). Engineers putative markers of influenza A virulence into a prototype strain of swine flu influenza (S-OIV). Measures replication in cell culture, virulence in mice and ferrets and aerosol transmission in ferrets and finds that the markers of influenza A virulence do not increase virulence in the swine flu strain.

Zhu, H. C. et al. Substitution of lysine at 627 position in PB2 protein does not change virulence of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus in mice. Virology 401, 1–5 (2010).

Pepin, K. M. & Wichman, H. A. Variable epistatic effects between mutations at host recognition sites in phiX174 bacteriophage. Evolution 61, 1710–1724 (2007).

Cuevas, J. M., Moya, A. & Sanjuan, R. A genetic background with low mutational robustness is associated with increased adaptability to a novel host in an RNA virus. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 2041–2048 (2009).

Webby, R., Hoffmann, E. & Webster, R. Molecular constraints to interspecies transmission of viral pathogens. Nature Med. 10, S77–S81 (2004).

Szretter, K. J. et al. Early control of H5N1 influenza virus replication by the type I interferon response in mice. J. Virol. 83, 5825–5834 (2009).

Pulliam, J. R. & Dushoff, J. Ability to replicate in the cytoplasm predicts zoonotic transmission of livestock viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 199, 565–568 (2009). Statistical analysis of molecular viral traits that correlate with zoonotic emergence.

Sorrell, E. M., Wan, H., Araya, Y., Song, H. & Perez, D. R. Minimal molecular constraints for respiratory droplet transmission of an avian-human H9N2 influenza A virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7565–7570 (2009). Investigates the genetic basis of transmission from avian to mammalian hosts. They construct a reassorted avian–human influenza strain (H9N2–H3N2) and adapt this virus to ferrets. They find that the virus gained aerosol transmission ability in ferrets by few genetic changes that also altered the antigenic profile .

Yassine, H. M., Al-Natour, M. Q., Lee, C. W. & Saif, Y. M. Interspecies and intraspecies transmission of triple reassortant H3N2 influenza A viruses. Virol. J. 4, 129 (2007). Study of the cross-species transmission potential of four reassorted strains of influenza A virus originating from different host species (turkey and swine). They identify a putative marker of cross-species transmission and measure replication and transmission among turkeys, chickens and ducks.

Kim, M. C. et al. Pathogenicity and transmission studies of H7N7 avian influenza virus isolated from feces of magpie origin in chickens and magpie. Vet. Microbiol. 141, 268–274 (2010).

Duffy, S., Turner, P. E. & Burch, C. L. Pleiotropic costs of niche expansion in the RNA bacteriophage Phi 6. Genetics 172, 751–757 (2006).

Remold, S. K., Rambaut, A. & Turner, P. E. Evolutionary genomics of host adaptation in vesicular stomatitis virus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1138–1147 (2008).

Smith-Tsurkan, S. D., Wilke, C. O. & Novella, I. S. Incongruent fitness landscapes, not trade-offs, dominate the adaptation of VSV to novel host types. J. Gen. Virol. 9, 1484–1493 (2010).

Ciota, A. T. et al. Experimental passage of St. Louis encephalitis virus in vivo in mosquitoes and chickens reveals evolutionarily significant virus characteristics. PLoS One 4, e7876 (2009).

Coffey, L. L. et al. Arbovirus evolution in vivo is constrained by host alternation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6970–6975 (2008). Compares the adaptive potentials of epizootic and endemic strains of VEEV by experimental evolution under three passage conditions: only mice, only mosquitoes and alternating between the two, and finds that viruses passaged on alternating host types do not show increased fitness.

Vasilakis, N. et al. Mosquitoes put the brake on arbovirus evolution: experimental evolution reveals slower mutation accumulation in mosquito than vertebrate cells. Plos Pathog. 5, e1000467 (2009).

Weaver, S. C., Brault, A. C., Kang, W. & Holland, J. J. Genetic and fitness changes accompanying adaptation of an arbovirus to vertebrate and invertebrate cells. J. Virol. 73, 4316–4326 (1999).

Itoh, Y. et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature 460, 1021–1025 (2009).

Perkins, L. E. & Swayne, D. E. Comparative susceptibility of selected avian and mammalian species to a Hong Kong-origin H5N1 high-pathogenicity avian influenza virus. Avian Dis. 47, 956–967 (2003).

Manzoor, R. et al. PB2 protein of a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus strain A/chicken/Yamaguchi/7/2004 (H5N1) determines its replication potential in pigs. J. Virol. 83, 1572–1578 (2009).

[No authors listed]. Preliminary review of D222G amino acid substitution in the haemagglutinin of pandemic influenza A (H221N1) 2009 viruses. Wkly Epidemiol. Rec. 85, 21–22 (2010).

Kilander, A., Rykkvin, R., Dudman, S. G. & Hungnes, O. Observed association between the HA1 mutation D222G in the 2009 pandemic influenza A(H221N1) virus and severe clinical outcome, Norway 2009–2010. Euro Surveill. 15, 19498 (2010).

Shinya, K. et al. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature 440, 435–436 (2006).

Brown, J. D., Stallknecht, D. E., Beck, J. R., Suarez, D. L. & Swayne, D. E. Susceptibility of North American ducks and gulls to H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1663–1670 (2006).

Keawcharoen, J. et al. Wild ducks as long-distance vectors of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Emerging Infect. Dis. 14, 600–607 (2008).

Brault, A. C., Powers, A. M., Holmes, E. C., Woelk, C. H. & Weaver, S. C. Positively charged amino acid substitutions in the e2 envelope glycoprotein are associated with the emergence of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 76, 1718–1730 (2002).

Greene, I. P. et al. Envelope glycoprotein mutations mediate equine amplification and virulence of epizootic Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 79, 9128–9133 (2005).

Anishchenko, M. et al. Venezuelan encephalitis emergence mediated by a phylogenetically predicted viral mutation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4994–4999 (2006).

Bull, J. J. & Molineux, I. J. Predicting evolution from genomics: experimental evolution of bacteriophage T7. Heredity 100, 453–463 (2008).

Elena, S. F. & Lenski, R. E. Evolution experiments with microorganisms: the dynamics and genetic bases of adaptation. Nature Rev. Genet. 4, 457–469 (2003).

Elena, S. F. & Sanjuan, R. Virus evolution: Insights from an experimental approach. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38, 27–52 (2007).

Crill, W. D., Wichman, H. A. & Bull., J. J. Evolutionary reversals during viral adaptation to alternating hosts. Genetics 154, 27–37 (2000).

Wichman, H. A., Badgett, M. R., Scott, L. A., Boulianne, C. M. & Bull., J. J. Different trajectories of parallel evolution during viral adaptation. Science 285, 422–424 (1999).

Wichman, H. A., Scott, L. A., Yarber, C. D. & Bull., J. J. Experimental evolution recapitulates natural evolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355, 1677–1684 (2000).

Brown, E. G., Liu, H., Kit, L. C., Baird, S. & Nesrallah, M. Pattern of mutation in the genome of influenza A virus on adaptation to increased virulence in the mouse lung: identification of functional themes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6883–6888 (2001).

Keleta, L., Ibricevic, A., Bovin, N. V., Brody, S. L. & Brown, E. G. Experimental evolution of human influenza virus H3 hemagglutinin in the mouse lung identifies adaptive regions in HA1 and HA2. J. Virol. 82, 11599–11608 (2008).

Wu, R. et al. Multiple amino acid substitutions are involved in the adaptation of H9N2 avian influenza virus to mice. Vet. Microbiol. 138, 85–91 (2009).

Narasaraju, T. et al. Adaptation of human influenza H3N2 virus in a mouse pneumonitis model: insights into viral virulence, tissue tropism and host pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 11, 2–11 (2009).

Lemey, P., Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J. & Suchard, M. A. Bayesian phylogeography finds its roots. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000520 (2009).

Janies, D. A. et al. The Supramap project: linking pathogen genomes with geography to fight emergent infectious diseases. Cladistics 2010, 1–6 (2010).

Liechti, R. et al. OpenFluDB, a database for human and animal influenza virus. Database 6, baq004 (2010). Development of an application, Supramap ( http://supramap.osu.edu ), that incorporates the dynamics of pathogen epidemiology and evolution into a geographical context to test genetic markers for host-jump potential and to estimate their global transmission patterns.

Bush, R. M. Influenza as a model system for studying the cross-species transfer and evolution of the SARS coronavirus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B Biol. Sci. 359, 1067–1073 (2004).

Qu, X. X. et al. Identification of two critical amino acid residues of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for its variation in zoonotic tropism transition via a double substitution strategy. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29588–29595 (2005).

Song, M. S. et al. Ecology of H3 avian influenza viruses in Korea and assessment of their pathogenic potentials. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 949–957 (2008).

Hoelzer, K., Shackelton, L. A., Holmes, E. C. & Parrish, C. R. Within-host genetic diversity of endemic and emerging parvoviruses of dogs and cats. J. Virol. 82, 11096–11105 (2008). Investigates within-host genetic diversity produced by canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus during natural and experimental infections.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research and Policy for Infectious Diseases Dynamics (RAPIDD) programme of the Science and Technology Directorate, the Department of Homeland Security and Fogarty International Center and the National Institutes of Health. K.M.P. was also supported by National Science Foundation grant 0742373; S.L. was supported by National Science Foundation grant DEB-0520468 to P. Hudson; J.L.-S. was supported by National Science Foundation grant EF-0928690 and the De Logi Chair in Biological Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Supplementary information

Supplementary information S1 (table)

Articles used in analysis (XLS 112 kb)

Supplementary information S2 (box)

Methods used to analyse articles (PDF 394 kb)

Supplementary information S3 (figure)

Research effort on viral host jumps. (PDF 279 kb)

Supplementary information S4 (figure)

Inclusion of experiment in studies with relevant data. (PDF 279 kb)

Supplementary information S5 (figure)

Types of data used for analyses of evolutionary processes. (PDF 325 kb)

Supplementary information S6 (figure)

Replication and experimental evolution in experimental studies. (PDF 288 kb)

Supplementary information S7 (figure)

Model systems in experimental studies. (PDF 334 kb)

Glossary

- Reservoir

-

Host population in which a virus is maintained long term.

- Host jump

-

The complete process of a virus transmitting between a reservoir host and a new host followed by sustained transmission among individuals of the new host population.

- Emergence

-

The appearance of new viruses in a population, particularly the appearance and sustained transmission of viruses in a new host species (as opposed to new strains in host populations in which the virus is endemic).

- Ecological change

-

A shift in frequency, nature or outcome of host species contact caused by factors such as demography, migration, invasion or environmental change.

- Adaptation

-

Genetic change driven by natural selection.

- Genetic markers of adaptation

-

Changes in the viral genome that are indicative of adaptation to a new host species. These may include point mutation, insertion, deletion, recombination, reassortment or any combination of these.

- Viral fitness

-

Genetic contribution to future generations of the entire virus population circulating in an entire population of hosts.

- Cross-species transmission

-

Transmission of infection between different host species. This does not include subsequent transmission among hosts in the new host population. Cross-species transmission is a necessary precondition for a host jump but is not sufficient to be called a host jump.

- Convergent evolution

-

Independent occurrence of the same trait in multiple lineages (that is, same genetic change evolves as a result of a similar selective pressure).

- Adaptive fine-tuning

-

Fixation of mutations that increase fitness in situations in which fitness is already high enough for sustained transmission (that is, a change from adapted to more adapted).

- Contact-tracing data

-

Determination of the occurrence and nature of contacts between individual hosts, often used in an attempt to reconstruct the host–host transmission chain for a set of infections.

- Founder effects

-

A shift in genetic composition owing to sampling effects.

- Neutral evolution

-

Fixation of mutations that do not affect fitness.

- Positive selection

-

The force that causes an increase in the frequency of fitness-enhancing mutations.

- Selective pressures

-

Environmental conditions, either biotic or abiotic, that decrease genetic variation by excluding deleterious mutations or increasing the frequency of beneficial mutations. In viruses, these pressures operate at two main scales: within hosts (through cell receptor structure and host immune response) and between hosts (through host contact rates and population heterogeneity in immunity).

- Adaptive constraints

-

Forces that restrict upward movement between genetic coordinates on the fitness landscape.

- Trait performance

-

Functionality of individual virus life-history traits such as receptor binding, replication rate and virion packaging rate.

- Within-host fitness

-

Genetic contribution to future generations of the virus population within a host.

- Basic reproductive number

-

The average number of secondary infections caused by an infected individual in a population of completely susceptible hosts.

- Stuttering transmission

-

A short-lived chain of transmission that can arise when R0 < 1 but not ≈ 0 (that is, for R0 > 0.5 it is likely that at least one transmission event will occur). The total number of cases is determined by chance, and extinction of the outbreak is certain if the virus does not adapt, but the additional exposure to new hosts can facilitate adaptive emergence if the appropriate mutations arise.

- Longitudinal sampling

-

Sampling over time to obtain a time series of viral strains.

- Mutation–selection balance

-

Steady-state frequency of deleterious genotypes determined by the balance between their continual creation by mutation and their exclusion by selection.

- Experimental evolution

-

Measuring evolutionary change in real-time by applying evolutionary forces experimentally and observing the outcome.

- Evolutionary process

-

A factor that drives genetic change, including genetic drift, mutation, gene flow and natural selection.

- Fitness landscape

-

The relationship of genotype and reproductive success. Often depicted in three dimensional space, in which the X and Y axes are the coordinates that describe all possible genetic combinations in the genome and the height of the Z axis gives the reproductive success for a given set of genetic coordinates.

- Experimental transmission

-

Transmission of a pathogen by placing infected and uninfected animals in close proximity; this is quasi-natural transmission as it excludes the role of contact probability in transmission.

- Parallel evolution

-

Independent occurrence of the same trait in lineages that arose from a common ancestor (that is, same genetic change evolves independently from same genetic starting point as a result of a similar selective pressure). This is a special case of convergent evolution.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pepin, K., Lass, S., Pulliam, J. et al. Identifying genetic markers of adaptation for surveillance of viral host jumps. Nat Rev Microbiol 8, 802–813 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2440

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2440

This article is cited by

-

The origin and continuing adaptive evolution of chikungunya virus

Archives of Virology (2022)

-

Ecology, evolution and spillover of coronaviruses from bats

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2022)

-

Assessing circovirus gene flow in multiple spill-over events

Virus Genes (2019)

-

Computational analysis of the receptor binding specificity of novel influenza A/H7N9 viruses

BMC Genomics (2018)

-

Insight into the global evolution of Rodentia associated Morbilli-related paramyxoviruses

Scientific Reports (2017)