Abstract

The maintenance of quiescence in T cells plays a pivotal role in averting undesired immune reactions and fostering immune homeostasis. Upon receiving external signals of cognate antigen and costimulatory molecules, T cells escape a quiescent state and rapidly proliferate within an exceedingly short timeframe. Nevertheless, for the majority of their lifespan, T cells remain inactive before stimulation, yet they are highly poised to future activation, implicating the presence of dynamic and intricate regulatory processes in a seemingly dormant state. While numerous extrinsic cues have been identified to induce T cell activation from a quiescence currently, intrinsic mechanisms governing T cell quiescence have received limited attention. Here we provide a comprehensive overview of multiple factors involved in T cell quiescence and their molecular mechanisms mainly in the context of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Given the intricate interplay between the control of T cell quiescence and a variety of diseases including autoimmunity, exhaustion and even tumor control, a thorough understanding of current insights into T cell quiescence affords us a valuable opportunity to advance our comprehension of T cell biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of cells in adult mammalian are quiescent, defined as a state of reversible growth arrest. In the quiescent state, cells exit from normal cell cycle and remain in a nonproliferative state in G0 phase1. In addition to being devoid of cell division, smaller cell size, low metabolic activity and global suppression of RNA and protein synthesis are common hallmarks characterized in cellular quiescence2. However, quiescent cells are capable of resuming cell cycling upon certain stimuli from the extracellular environment while they retain their minimalistic characteristics1,3. Such reversibility confers a distinct feature from other types of nondividing cell, such as senescent or terminally differentiated cells, which are unable to proliferate permanently3. Unlike the terminological implication, it is now clear that quiescent cells are not inert but rather actively maintain their quiescent state by consistently expressing regulatory factors, which not only prevent proliferation and terminal differentiation but also prepare the cells for reentry into cell cycle1,3. These regulatory events commonly involve the inhibition of key regulators in cell cycle initiation, including cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) or, alternatively, the induction of CDK inhibitors or retinoblastoma protein (Rb), which inhibits E2F, a transcriptional activator for cell cycle and division1,3. Of note, the concept of cellular quiescence has also been described in T lymphocytes (T cells), essential players in adaptive immune system. Naive and memory T cells in a resting state also actively maintain cellular quiescence but timely exit from a quiescent state and undergo proliferation and differentiation to optimize their functional effectiveness upon proper activating cues, such as cognate antigen engagement with T cell receptor (TCR)4,5. By contrast, aberrant regulation of cellular quiescence in T cells is closely related to pathological outcomes. Failure of quiescence exit leads to poor responsiveness to pathogens, as seen in immunodeficiency, whereas uncontrolled escape from a quiescence state results in autoimmune disorders by excessive activation of T lymphocytes4. Therefore, given the critical role of T cell quiescence in immune homeostasis, it will be worthwhile to understand T cell biology in the context of cellular quiescence. The maintenance of quiescence in T cells is sophisticatedly regulated by a variety of factors including metabolic changes, extrinsic factors and intrinsic regulators4,6. Although several features of T cell quiescence and its metabolic regulation have been previously reviewed4, the intrinsic regulation of quiescence has been poorly described. In this Review Article, we summarize the molecular mechanisms of intrinsic regulators specifically focusing on transcription factors and proteins regulating post-transcriptional regulations involved in maintaining T cell quiescence and highlight recent findings that elucidate the role of intrinsic regulation of this process.

Overview of T cell quiescence

T lymphocytes originated from lymphoid progenitors, which are hematopoietic stem cells committed to lymphoid lineage7. Immature T lymphocytes, referred to as thymocytes, undergo developmental stages in the thymus, progressing from CD4−CD8− double-negative to CD4+CD8+ double-positive and, finally, to CD4+ or CD8+ single-positive thymocytes8. T cell quiescence starts to build up in the transition from CD4+CD8+ double positive to CD4+ or CD8+ single positive and is fully established when T cells exit from the thymus as naive T cells4,9. Mature naive T cells circulate in the periphery via blood and lymphatic vessels, homing to secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) where they receive essential survival signals and remain their quiescent state10. These quiescent naive T cells are metabolically and physiologically suppressed yet poised for activation upon recognition of a cognate antigen along with costimulatory signals and cytokines4,11.

Extrinsic regulation of T cell quiescence

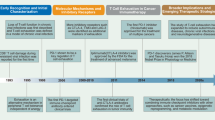

Under normal conditions lacking activating stimuli, T cell quiescence is maintained by intrinsic programs along with extrinsic cues, including the cytokine interleukin 7 (IL-7) (ref. 12), tonic TCR signaling13 and other regulatory signals from the lymphoid niche, fostering long-term survival and proper positioning of naive T cells (Fig. 1). The maintenance of peripheral naive T cell pool in a quiescent state relies on signals from IL-7, which is essential for T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation14. IL-7, constitutively provided by stromal cells in peripheral lymphoid organs, primarily influences T cells through their expression of the IL-7 receptor (IL-7R), particularly the IL-7 α-chain (IL-7Rα; CD127)15. Numerous studies have reported that the survival of mature and memory T cells is profoundly compromised by IL-7 deficiency or blockade16,17. Signaling through JAK3-STAT5 pathway downstream of IL-7R induces the antiapoptotic molecule Bcl-2 (ref. 14) and enhances the protein stability of CDK inhibitor p27Kip1, preventing cell cycle entry18. This function of IL-7 is closely linked to the microenvironment of lymph nodes and the spleen, where quiescent T cells express CD62L (L-selectin) and C–C chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7), facilitating their migration and localization within peripheral lymphoid organs. CD62L, also known as L-selectin, promotes T cell adhesion to high endothelial venules and aids in homing to lymph nodes. CCR7, a chemokine receptor for CCL19 and CCL21, guides T cells from the cortex to the medulla of the thymus and to the T cell zones in lymph nodes during migration. Upon entering the lymph node microenvironment, fibroblastic reticular cells provide essential survival signals, including IL-7, to maintain T cell quiescence and homeostasis19. Moreover, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) serves a critical function in T cell egress by binding to sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), which is abundant in the outer region of the thymus; its deficiency results in T cell lymphopenia in peripheral lymphoid organs20. S1P promotes naive T cell survival by supporting energy provision for T cell migration through mitochondrial regulation21. Tonic TCR stimulation occurs when TCR engages with self-peptide-bearing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules presented by antigen-presenting cells in SLOs13,22. Unlike strong TCR signaling induced by cognate antigens, which leads to quiescence exit and T cell activation, tonic TCR stimulation activates several intrinsic regulators, such as FOXO1, that sustains T cell quiescence by promoting IL-7R expression, essential for IL-7 signaling13.

During circulation, multiple factors contribute to the maintenance of quiescence in naive T cells. Trafficking molecules (S1P1, CD62L and CCR7) guide T cell circulation, leading T cells to encounter diverse factors involved in the maintenance of quiescence. S1P, abundant in blood, directs egress of T cells from lymphoid organs and promote the survival of quiescent T cells via its receptor S1P1. Tonic TCR stimulation occurs in lymphoid organs by the engagement of self-peptide bearing MHC molecules and facilitate T cell quiescence. High level of IL-7 in periphery also supports the survival of T cells and prevent quiescence exit through IL-7R. Intrinsic regulators programmed in quiescent T cells coordinate these extrinsic signals for optimal maintenance of quiescence. DP, CD4+CD8+ double positive; SP, CD4+ or CD8+ single positive.

Metabolic regulation of T cell quiescence

Naive T cells remain in a quiescent, nonproliferative state until they encounter proliferative TCR stimulation. During this period, they maintain long-term survival while continuously circulating between SLOs and the bloodstream in preparation for potential antigenic challenges. To adapt to conditions of limited energy availability, naive T cells exhibit low metabolic activity23. Rather than relying on glycolysis, they primarily utilize oxidative phosphorylation through pyruvate and fatty acid oxidation that supports their longevity under energy-restricted conditions24. TCR stimulation and CD28 costimulatory signals induce a dramatic metabolic reprogramming, followed by enhanced anabolic processes including the synthesis of mRNA, lipids and proteins to support cell growth and extensive proliferation25. To rapidly meet the increased energetic and biosynthetic demands, activated T cells shift their metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and glutaminolysis. Specifically, glycolysis facilitates the rapid generation of ATP through the conversion of glucose to pyruvate. Increased expression of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) promotes the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, regenerating NAD⁺ from NADH and thereby sustaining high glycolytic flux. Concurrently, glutamine is metabolized through glutaminolysis, yielding glutamate and α-ketoglutarate, which results in anaplerotic reaction replenishing intermediates of TCA cycle, which supports the biosynthesis of amino acids, lipids and nucleotides, including purines and pyrimidines26.

Following T cell activation, the expression of nutrient transporter proteins such as GLUT1, SLC1A5 and SLC7A5 is markedly upregulated, facilitating increased uptake of extracellular glucose and glutamine4. Concurrently, the expression of key metabolic enzymes involved in glycolysis and glutaminolysis is also enhanced. These metabolic adaptations are largely driven by activation of the PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway, which acts in concert with Src family kinases, promoting the activity of CDKs, leading to cell proliferation through reentry into cell cycle27. mTORC1 plays a diverse role in the exit from quiescence by regulating ribosomal biogenesis through activation of p70S6K and suppression of translational repressors such as 4E-BP, thereby promoting overall protein synthesis28. Furthermore, mTORC1 induces c-Myc expression, a positive regulator of interphase CDKs and cyclin expression29. Myc drives the metabolic shift in T cells from FAO and oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and glutaminolysis, promoting effector T cell growth and activation. While mTORC1 enhances Myc synthesis via eIF4E, in turn, Myc upregulates amino acid transporters to boost glutamine uptake, reinforcing mTORC1 signaling in a feedback loop that accelerates T cell prolife ration and activation23. Furthermore, mTORC1 promotes localization of SREBP1/2 into the nucleus, which transcriptionally activates proteins mediating cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis30. These axes collectively lead to cell growth and enhancement of cellular metabolism, supporting the robust growth and proliferation of activated T cells.

In naive T cells, tight regulation of the PI3K–Akt–mTORC1 checkpoint is essential to prevent excessive metabolic activation, spontaneous T cell activation and the potential development of autoimmunity. Key negative regulators of this pathway include PTEN and TSC proteins. PTEN antagonizes PI3K activity by converting phosphatidylinositol3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) to phosphatidylinositol4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), serving as a negative regulator of AKT signaling31. In CD4⁺ T cells, PTEN deficiency does not necessarily result in spontaneous activation; however, it lowers the TCR signaling threshold, allowing robust AKT activation even in the absence of CD28 costimulation32. TSC2 functions as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for the small GTPase RHEB, which directly activates mTORC1 (ref. 33). In the absence of TSC2, naive T cells exhibit constitutive activation of mTORC1, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of downstream targets S6K and 4E-BP1. These cells tend to be hyperactivated, highly glycolytic phenotype even without full activation and fail to efficiently transition into memory T cells34. In the absence of TSC1, which stabilizes TSC2, T cells become hypersensitive to TCR stimulation, leading to rapid and aberrant activation, premature cell cycle entry, elevated reactive oxygen species production and increased expression of proapoptotic factors such as BIM, ultimately resulting in increased cell death35.

Thus, T cells maintain their quiescent state via negative regulator of their critical metabolic checkpoints, which is critical for appropriate and timely activation. In this context, transcription factor FOXO1 is target of AKT-mediated phosphorylation and thereby degradation, which regulating the aforementioned expression of genes extrinsic factors for T cell quiescence including IL-7Rα, CCR7 and CD62L36. Therefore, both extrinsic signals and intrinsic regulators are intricately interconnected to maintain the quiescence and long-term survival of naive T cells.

Intrinsic regulation of T cell quiescence mediated by transcription factors

Although diverse extrinsic stimuli and metabolic regulators have been known to control quiescence in T cells, these are intertwined with many intrinsic factors to optimally maintain T cell quiescence. Both extrinsic cues inducing quiescence or the absence of activating stimuli enable T cells to continuously express specific gene programs associated with intrinsic regulators. Currently, several intrinsic factors have been reported that are specialized for maintaining T cell quiescence. Most of these factors are multifunctional, and their control extends beyond the maintenance of naive T cells. Among these intrinsic regulators, transcription factors play a central role in mastering T cell quiescence downstream of extrinsic and intrinsic signaling. Hereby, we introduce the transcription factors KLF2, FOXO1, FOXP1 and BACH2 as pivotal in maintaining T cell quiescence.

KLF2, a regulator of T cell trafficking for quiescence maintenance

Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2), also known as lung Krüppel-like factor (LKLF), is a zinc-finger transcription factor of KLF family which is the first transcription factor identified as being involved in the quiescence of T lymphocytes37. Its expression is generally observed in mature thymocytes including naive and memory T cells but diminishes upon TCR stimulation38. KLF2 is expressed during the maturation of single-positive T cells in the thymus, and KLF2-deficient T cells were found to be highly apoptotic38. Given that the absence of KLF2 is embryonically lethal, early studies of KLF2 utilized a chimeric RAG2−/−KLF2−/− mouse model, in which KLF2−/− embryonic stem cells were injected into Rag2−/− blastocysts. This allowed the chimera to possess KLF2−/− lymphocytes without developmental defects38. A reduced number of peripheral T cells was observed in chimeric RAG-2−/−KLF2−/− mice, and KLF2-deficient T cells displayed activated phenotype along with nonproliferative features38. Subsequently, several studies involving overexpression of KLF2 in Jurkat T cells demonstrated that KLF2-induced Jurkat T cells exhibited a quiescent phenotype. In addition, these studies suggested a functional pathway through which KLF2 induces p21WAF1/CIP1, a CDK inhibitor, and negatively regulates Myc, a multifunctional transcription factor involved in cell growth and division37,39,40 (Fig. 2d). Mechanistically, Myc promotes CDK2 activity by inducing transcription of cdc25a and repressing Gadd45 (refs. 41,42), a growth inhibitory gene. Therefore, its suppression by KLF2 likely contributes to maintaining a quiescent state. In addition, overexpression in tumor cell lines, such as NSCLC43 and breast cancer44, suppresses their proliferation and mediates cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase, thereby underscoring its role as a tumor suppressor.

The summarized molecular mechanisms of intrinsic regulators in T cell quiescence. The regulation of T cell trafficking molecules (a) and IL-7R (b), suppression of T cell activation (c), cell cycling inhibition (d) and downregulation of global mRNA abundance (e). In a, FOXO1 and KLF2 induce the transcription of T cell trafficking molecules (CD62L, S1P1 and CCR7), which are essential for proper migratory function of naive and memory T cells to maintain a quiescent state. In b, FOXO1 promotes IL-7 signaling by inducing IL-7R expression. FOXP1 inhibits IL-7R expression by antagonizing FOXO1, ultimately prevents excessive IL-7R signaling. Thus, the duration of IL-7R signaling is balanced by both FOXO1 and FOXP1. In c, TCR-mediated activating signals are suppressed by FOXP1 activity. FOXP1 directly inhibits Erk and induce the transcription of Pik3ip1, an inhibitor of PI3K. The expression of genes targeted by AP-1, an important transcription factor for effector function of activated T cells, is competitively blocked by BACH2 which share same binding sites of AP-1. Also, BACH2, induced by FOXO1 inhibits Prdm1 expression. In d, FOXP1 blocks the expression of E2F, a key molecule for cell cycle progression. FOXO1 upregulates Klf2 expression, and KLF2 and TOB1 also induce CDK inhibitors, P21 and P27, which prevent cell cycling by inhibiting CDK activity. In e, the global abundance of mRNA is downregulated by BTG1/2 expressed in a quiescent T cell. BTG1/2 bind to PABP on poly(A) tail of mRNA and recruit CNOT deadenylase complex. The interaction between BTG1/2 and CNOT complex enhance deadenylase activity, resulting in mRNA degradation by shortening poly(A) tail. PI3K, phosphoinositide-3-kinase; IL-2, interleukin 2.

However, the effects of KLF2 on cell cycle regulation, observed through overexpression in activated T cells or Jurkat cell line, have been challenged by more physiologically relevant and sophisticated experiments. One of these experiments demonstrates that overexpression at physiological levels results in the deceleration of the proliferative expansion, rather than quiescence mediated by regulation of Myc and p21WAF1/CIP1(ref. 45), while defining the primary role of KLF2 as regulating molecules involved in the trafficking of naive T cells45,46,47,48. As thymocytes complete their maturation in the thymus, single positive CD4+ or CD8+ T cells egress from the thymus and home to SLOs with assists of several T cell trafficking molecules45,46,49. Carlson and colleagues first reported impaired expression of T cell trafficking molecules—S1P1, CD62L, CCR7 and β7 integrin—in RAG-2−/−KLF2−/− mice50. This view is further supported by studies using overexpression and Cre-mediated knockout systems47,51,52, which demonstrate that KLF2 directly induces the transcription of CD62L and S1P1 (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, another study has shown that KLF2 is required to suppress the expression of various chemokine receptors associated with T cell migration during inflammatory responses, including CXCR3 (refs. 45,46,47), where abrogation of migratory receptors leads to the abnormal distribution of T cells across SLOs and peripheral tissues47. Moreover, KLF2-deficient T cells showed increased levels of cytokine production (IL-4, IFN-γ and TNF) whether through direct or indirect regulation by KLF2 (ref. 52). Taken together, the findings show that KLF2-deficient T cells promote an autoimmune phenotype such as increased serum IgE level and lymphopenia47,50,52. The broad role of KLF2 in immune responses is mediated through its direct regulation of molecules related to T cell chemotaxis, such as CD62L and S1P1. Nevertheless, the role of KLF2 in contexts beyond its control of T cell trafficking and needs to be further studied.

FOXO1, an integrator of transcriptional networks in T cells

FOXO proteins, which belong to the forkhead box (FOX) family, are comprised of four subfamily members in mammals: FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4 and FOXO6 (ref. 53). FOXO proteins can directly regulates target gene expression using winged helix forkhead DNA-binding sites that interacts with the consensus motif 5′-TTGTTTAC-3′ (ref. 53). In addition, FOXO proteins cooperate with other binding partners—C/EBPβ, STATs, Smads, p300 and various nuclear receptors54—implying a diverse range of roles for FOXO-mediated regulation. The activity of FOXO is controlled by phosphorylation, which determines its cellular localization and degradation53. For instance, PI3K–Akt signaling can phosphorylate FOXO proteins, hindering their ability to bind DNA and inducing their translocation from nucleus to cytoplasm53. Among FOXO subfamily members, the expression of FOXO1 is specifically induced during T cell maturation55 and is known to contribute T cell quiescence while FOXO3 and FOXO4 are also expressed in T cells. Similar to the function of KLF2, FOXO1 can regulate T cell trafficking molecules, as first reported in a study where FOXO1 overexpression in Jurkat T cells resulted in the high expression of CD62L, S1P1 and CCR7, whereas T cells from FOXO1-deficient mice showed impaired expression of these molecules56. Intriguingly, FOXO1 can directly binds to the Klf2 promoter to regulate its expression56, which regulates genes involved in T cell trafficking as discussed in the previous section (Fig. 2d). The fact that FOXO1 could upregulate their expression even when KLF2 is partially knockdown56, and its ability to directly bind to the genomic loci of Sell and Ccr7(ref. 57)(Fig. 2a) indicates that FOXO1 may regulate their expression directly, although their expression is primarily regulated by KLF2-dependent manner45.

However, despite the lack of details, it seems apparent that FOXO1 may facilitate proper migratory function of T cells in a KLF2-independent manner in other immune contexts, where FOXO1 regulates Sell and Ccr7 expression without substantial changes in Klf2 expression58. Notably, various studies have demonstrated that the expression of IL-7Rα in steady state T cells is directly regulated by FOXO1, as evidenced by the use of a conditional knockout system targeting the Foxo1 gene in T cells36,59. As shown in these studies, FOXO1 deficiency in T cells results in the decreased expression of IL-7Rα at both the mRNA and protein levels36,59. Regulation of IL-7Rα by FOXO1 was associated with direct binding to the evolutionary conserved noncoding region located 3.7 kb upstream of Il7r gene translation start site, which indicates that IL-7R is one of the targets of FOXO1 (refs. 36,59). In addition to regulating IL-7Rα, the absence of FOXO1 was associated with an increased number of activated populations of CD44+CD62L− in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as more differentiated T cells expressing cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17 or IL-10 (ref. 59). Consistently, chimeric mice reconstituted with FOXO1-deficient bone marrow spontaneously developed severe colitis, accompanied by a higher proportion of effector T cell populations59, further supporting the role of FOXO1 in control of T cell tolerance and homeostasis. Furthermore, the integrative role of FOXO1 has been proposed in a study utilizing a FOXO1-AAA mutant, which is continuously expressed in T cells to enable FOXO1 to maintain its activity, which normally diminishes after T cell activation60. Prolonged expression of FOXO1 resulted in imbalanced cell growth and proliferation, which was associated with the suppression of newly defined targets by FOXO1, including Myc, ribosome biogenesis and cholesterol biosynthesis60. Moreover, FOXO1 decreased mTORC activity, indicating the important role of FOXO1 in the cell intrinsic coordination of growth and proliferation. A recent study of naive and memory CD8+ T cells has also suggested that FOXO1 inhibits AP-1 family transcription factor, which is responsible for the upregulation of genes involved in effector functions such as Ifng (Fig. 2c). This inhibition occurs directly by FOXO1 binding to the genomic loci of AP-1 transcription factor family, or indirectly by inducing BACH2 in naive and memory CD8+ T cells57. BACH2, which will be further elaborated upon in a subsequent paragraph, additionally suppresses the activity of AP-1 transcription factors by occupying their enhancer regions. Furthermore, the study has revealed a correlation between FOXO1 and cellular senescence, which resembles cellular quiescence but represents a permanent arrest in the G0 phase57. In the absence of FOXO1, memory T cells not only displayed excessive activation but also exhibited a senescent phenotype57. Of note, the expression of FOXO1 was diminished in old (18–24 months) mice compared with young controls, along with TCF1, an essential regulator in memory T cell maintenance, which suggests that FOXO1 also contributes to maintaining reversibility during a quiescent state by balancing between quiescence and senescence57.

FOXP1, a balancer for IL-7 and TCR signaling in T cells

Forkhead box protein P1 (FOXP1), a member of large FOX transcription factor family, is expressed in various cell types and is an essential transcription factor for B lymphocytes development61,62. In the context of T lymphocytes, it has also been reported that the conditional loss of FOXP1 in CD4+CD8+ double-positive thymocytes resulted in single-positive thymocytes becoming more sensitive, accompanied by increased cytokine production and apoptosis63, indicating that FOXP1 plays a critical role in the development of quiescent naive T cells. In a study utilizing inducible deletion of Foxp1, mature naive T cells deficient in FOXP1 exhibited effector phenotypes and demonstrated increased proliferation, which was dependent on IL-7 (ref. 64). The study has demonstrated that FOXP1 negatively regulates the expression of IL-7R by antagonizing FOXO1 activity. FOXP1 binds to forkhead-binding site of Il7r gene enhancer region, which is also targeted by FOXO1, thus antagonizing FOXO1’s activity64. Although FOXO1 promotes T cell quiescence by enhancing the survival and homeostatic proliferation through the upregulation of IL-7R, thereby enhancing IL-7 signaling, the role of FOXP1 in T cell quiescence appears paradoxical given that it downregulates IL-7R. Prolonged signaling through IL-7R induces rather proliferation of naive T cells and enhances IFN-γ production, leading to cytokine-induced cell death, which was observed in a study with naive CD8+ T cells continuously expressing IL-7R12. For the maintenance of quiescent T cells, IL-7 signaling should be intermittent, and this should occur in conjunction with tonic TCR signaling12. Therefore, the proper balance in the regulation of IL-7R by FOXP1 and FOXO1 is critical for the homeostasis of quiescent T cell pool through the fine-tuning of IL-7 signaling (Fig. 2b). In addition to control of IL-7R, several studies have further defined the role of FOXP1 in T cell quiescence that regulates a variety of signaling pathways associated with T cell activation, differentiation, growth and proliferation.

The MEK/ERK pathway is one of the critical signaling pathways involved in TCR stimulus, leading to the T cell activation. In the absence of FOXP1, CD8+ T cells exhibited enhanced ERK phosphorylation upon TCR stimulation, highlighting the role of FOXP1 in limiting the activity of ERK and its downstream pathway64. Actually, MEK/ERK pathway inhibits the transcription of Klf2 after TCR engagement45, which suggests another regulation network among transcription factors related to quiescence. FOXP1 also downregulates the PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway by directly inducing the expression of PI3K interacting protein 1 (Pik3ip1)65, a negative regulator of upstream of PI3K, which in turn leads to decreased Akt phosphorylation, leading to the suppression of T cell activation65,66 (Fig. 2c). Moreover, FOXP1 negatively modulates cell cycle progression through the downregulation of E2F transcription factor and cell cycle gene expression65. Its inducible deletion in naive CD8+ T cells cultured with IL-7 leads to the increased mRNA levels of E2f1, E2f3 and Cdk1, as well as markedly enhanced IL-7-driven homeostatic proliferation. This regulation of cell cycle occurs independently of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb)65, a well-known tumor suppressor that inhibits E2F function, suggesting that FOXP1 controls E2F at the transcriptional level to ensure T cell quiescence (Fig. 2d).

In summary, FOXP1 regulates quiescence by inhibiting key TCR signaling pathways and through genes associated with cell cycle progression. The role of FOXP1 in memory T cell and other immune contexts, as well as the relevance of its function in maintaining quiescence, remains to be further elucidated.

BACH2, a gatekeeper of effector T cell differentiation by antagonizing AP-1

BACH2 acts as a transcriptional repressor, which belongs to the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor family. It was previously known to function in B cell somatic hypermutation and antibody class switching67, and it was suspected to have functions in T cell homeostasis because its genetic mutations lead to various autoimmune phenotypes68,69,70, such as asthma71 and multiple sclerosis72. The expression of BACH2 remains high throughout T cell maturation and in naive T cells, but it is progressively downregulated as T cells become activated—from central memory T cells to the effector phase—with the lowest levels observed in terminally differentiated T cells73. Although T cell development appears normal in germline knockouts of BACH2, a decrease in T cell numbers has been observed in the spleen and lymph nodes. This reduction is attributed to the decreased ratio and numbers of naive T cell population, which contributes to systemic inflammation74. Moreover, BACH2 deficiency in mixed bone marrow chimera mice results in the impaired central memory and memory precursor effector cells, as well as an increased population of short-lived effector cells in a virus infection model, which indicates that BACH2-knockout disrupts naive T cell homeostasis, promotes terminal differentiation and leads to the increased apoptosis73. In BACH2-deficient mice, naive T cells exhibit heightened T cell differentiation and function, marked by increased production of cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-17, along with their master transcription factors, despite the unchanged rates of proliferation during early T cell activation69,73,74. Furthermore, successive rounds of cell cycle following naive T cell activation lead to increased apoptosis in BACH2-deficient cells, accompanied by reduced antiapoptotic BCL-2 protein family, characterizing increased effector differentiation73. Disruption of quiescence in BACH2-deficient T cells stems from its control over genes related to effector lineages. For instance, the chemokine receptor CCR4, which has CCL21 as its ligand and is typically upregulated in activated T cells to facilitate recruitment to inflammatory sites, is highly expressed in naive T cells lacking BACH2 (ref. 74). Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis of activated T cells found that BACH2 binds to the genes such as Gata3, Irf4, Nfil3, Il12rb1 and Il12rb2, which are related to the effector differentiation and lineage, thereby suppress their expression69. BACH2 also binds to the Prdm1 locus to repress its expression, which encodes BLIMP-1, a major regulator of T cell effector differentiation (Fig. 2c). The ability of BACH2 to regulate effector differentiation is attributed to the attenuation of TCR-driven gene expression by AP-1 transcription factor family, which shares a common transcription factor binding motif with BACH2 (ref. 73). It allows BACH2 to occupy the same binding sites before TCR engagement, thereby limiting the access of AP-1 transcription factors and reducing their target gene expression. Within several hours of naive T cell activation, there is a increase in gene expression regulated by AP-1 transcription factor family, such as Ifng and Gp49a, as well as effector-related genes including Cd44, Ccl1, Ccl19 and Lta. In the absence of BACH2, there is an increased occupancy of JunD, a member of AP-1 transcription factor family, at the TCR-driven gene enhancer loci, resulting in enhanced expression of its target genes, thereby exhibiting an activated phenotype.

Super-enhancers are large clusters of transcriptional enhancers densely packed with transcription factors and regulatory proteins that exhibit enhanced transcriptional activity. Characterized by high H3K27Ac signals and substantial p300 occupancy, they play a crucial role in defining cellular identity75. BACH2 binds to 26% of super-enhancer regions in CD4+ T cells, repressing crucial T cell identity genes, including cytokines and their receptors. Besides controlling genes in super-enhancers, Bach2 genomic locus itself is one of the most prominent super-enhancer regions, suggesting the critical role of BACH2 in the regulation of T cell homeostasis and functions76. A recent study found that BACH2 also participates in maintaining the stemness of memory T cell population, where its deficiency was shown to impair TCF1hiTim3lo stem-like memory population77. In addition, gRNA-mediated knockout of BACH in this population led to the upregulation of PD-1 and Tim-3 as well as genes related to terminal exhaustion, such as Gzmb and Klrg1. On the contrary, overexpression of BACH2 suppresses the expression of effector-related molecules74 and reinforces the stemness property of memory population77. Overall, BACH2 helps maintain T cell quiescence by repressing the expression of TCR-driven genes and effector-signature genes.

Post-transcriptional regulation in control of T cell quiescence

Target gene expression in T cells is actively regulated by post-transcriptional mechanisms such as RNA splicing, RNA degradation and RNA modification across various cellular stages including naive states, memory formation and differentiation processes78. However, the role of post-transcriptional regulation associated with T cell quiescence has recently been emphasized. Splicing factor SRSF1 has been found to regulate quiescence by inhibiting the hyperactivity of T cells79. SRSF1 upregulates the expression of PTEN, a critical negative regulator of the PI3K–Akt pathway, which in turn represses mTORC1 activity. Consequently, this leads to the downregulation of T cell activation. In the absence of SRSF1, T cells become hyperactivated due to enhanced mTORC1 signals. In patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, a low abundance of SRSF1 and an increase in proinflammatory cytokine have been linked observed and overexpression of SRSF1 could reverse this phenotype and rescue the hyperactivated T cell state.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) mRNA methylation, one of the most abundant RNAmodifications, also plays a critical role in T cell homeostasis by modulating the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS signaling pathways in naive T cells80. In mice deficient in Mettl3 (the m6A writer), elevated levels of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins were observed. This increase was attributed to the absence of m6A-mediated degradation of SOCS mRNA, which normally facilitates its recognition and subsequent breakdown. Upregulated SOCS proteins disrupted IL-7-driven T cell differentiation and cytokine signaling, resulting in disrupted T cell expansion and homeostasis.

Recently, long noncoding RNA have also been found to modulate T cell quiescence. Long-interspersed element-1 (LINE1) has noncanonical splicing variants that are integrated into the genome by retro-transposition where its integration mediates target gene repression through PABP1. LINE1 is highly expressed in quiescent naive and memory T cells but can be expressed when T cells become exhausted, thereby limiting its effector function, a novel mechanism to restrain T cell activity81. Previously outlined were the recently discovered post-transcriptional regulators that control naive T cell quiescence and homeostasis. The subsequent discussion will be focused on BTG1 and BTG2, which have been recognized as antiproliferative proteins and recently identified as post-transcriptional regulators regulating T cell quiescence.

BTG1 and BTG2, post-transcriptional regulators of mRNA stability in quiescent T cells

The recent study has proposed BTG1 and BTG2 (BTG1/2) as novel regulators of T cell quiescent82. BTG1/2 are specifically expressed in quiescent T lymphocytes, both naive and memory subsets, and their expression is diminished upon activation82. BTG1/2 contribute to the active maintenance of quiescence, as BTG1/2 deficient T cells have displayed higher expression of activation markers such as such as CD25, CD44 and CD69 and more proliferative82. BTG1/2 are members of the BTG/TOB family that shares a highly conserved N-terminal BTG domain, providing a module for protein–protein interaction83. Among the members in BTG/TOB family, BTG1/2 are highly similar to each other and have unique feature of an additional eight to ten amino acids in N-terminal of the BTG domain, distinct from other members83. Through this domain, BTG1/2 interact with diverse transcription factors, facilitating their DNA binding and stimulating transcription factor activity, as reported in myoblast cells84. Notably, BTG proteins are also known for their antiproliferative activity in various cell types by modulating mRNA turnover. Several studies have revealed that BTG1/2 interact with previously mentioned deadenylase complex of CCR4-NOT (CNOT) and poly(A) tail binding protein (PABP), promoting mRNA degradation by deadenylation of poly(A) tail83,85,86. In detail, BTG1/2 bind to RRM domain of cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding proteins 1 (PABPC1) through their BTG domain, which is sufficient to induce mRNA deadenylation87. Of note, BTG1/2 present in quiescent T cells, continuously downregulate the global abundance of cytoplasmic mRNA through interaction with the PABP-CNOT7 deadenylase complex82. Indeed, CD4+ T cells from BTG1/2-double-knockout mice exhibited the longer poly(A) tails in global mRNA82. Consistent with this, the overall level of mRNA was increased along with enhanced protein expression, rendering T cells to overly sensitive to activation signal. Thus, the process by which BTG1/2 maintain T cell quiescence appears to provide quiescent T cells with advantages by harnessing premade mRNA for quick response, instead of complete shut-down of mRNA synthesis corresponding to a quiescent state82 (Fig. 2e). A recent study found out that in patients with B cell lymphoma, BTG1Q36H, the missense mutation of BTG1, was associated with a poor clinical outcome88. BTG1Q36H mutant B cells are more activated and exhibit increased proliferative burst following the germinal center reaction. Mutant B cells undergo an enhanced Myc-dependent program and upregulate mTORC1, which are important in controlling the biosynthetic preparedness of growth program. More specifically, BTG1 may targets mRNA of Myc target genes and Myc itself, suppressing its post-transcriptional regulation, which is lost and leads to enhanced polysome loading in the mutant B cell. Although further studies are needed to elucidate the same mechanism is applicable in T cells, existing research has demonstrated that BTG1/2, predominantly found in lymphoid organs and leukocytes82, may have distinct roles in the immune system compared with other members of the BTG/TOB family. Taken together, these findings offer new mechanistic insights into how T cells maintain reversibility during their quiescence by controlling post-transcriptional modifications. A recent study in exhaustion model demonstrated that chromatin accessibility at the BTG1 locus progressively increases during the establishment of exhaustion in tumors. This finding implicates BTG1 in reinforcing stress-adaptive or ‘quiescent-like’ transcriptional state in exhausted T cells, thereby suggesting that its function extends beyond the maintenance of naive T cell quiescence89.

Perspective

Cellular quiescence, once perceived as a default state, is now robustly recognized as being intricately regulated by a myriad of molecular mechanisms. Likewise, in the context of T lymphocytes, considerable studies have identified several regulatory pathways associated with T cell quiescence, encompassing intrinsic, extrinsic and metabolic aspects. Interestingly, while the quiescence of T cells shares some features commonly observed in other types of quiescent cell, regulatory factors involved in the maintenance of T cell quiescence are selectively expressed in these cells and specialized to modulate T cell functions. Moreover, T cell activation, followed by stimulus upon TCR, leads to the decreased expression of these factors or inhibition of their activity, suggesting that these regulatory systems are evolutionarily programmed to optimize T cell quiescence. Intrinsic factors play a fundamental role in the maintenance of T cell quiescence by coordinating other regulatory signals from extrinsic and metabolic pathways, a multifaceted functionality handled in this Review Article82. In addition, naive T cells are characterized by a unique and distinct chromatin landscape, including bivalent modifications and super-enhancers to remain their identity and actively maintain quiescence while preparing for activation, distinguishing them from other states in T cell population76,90. Taken together, these regulatory processes ultimately contribute to maintaining the proper threshold for T cell activation and homeostasis in naive and memory pools. However, although growing information sheds light on new insights into T cell quiescence, details linking such scattered pathways depending on surrounding microenvironments, and how these factors are involved in different contexts of T cells still need to be further elucidated.

Recent studies have elucidated the roles of these quiescent factors in the context of T cell exhaustion or tumor control. For example, BTG1, which regulates cell cycle and proliferative state of T cells, appears to be re-expressed to impose quiescent characteristics on exhausted CD8+ T cells89. BACH2 limits the potential of differentiation by inhibiting access to the activation signatures, the expression of which supports the maintenance of stem-like CD8+ T cell population77. FOXP1 and KLF2 were recently identified as hub transcription factors within regulatory network that governs differentiation of CAR-T cells, where KLF2 promotes differentiation program into the effector program, suppressing exhaustion program, while FOXP1 promotes stemness and limits the transition of stem-like T cells to the effector subset91. Overexpression of another quiescent factor, FOXO1, in CAR-T cells enhances stem-like features, characterized by increased mitochondrial activity and improved memory fitness, ultimately leading to the effective tumor control92,93. These findings demonstrate that these factors can fulfill multifaceted roles across various stages of T cell differentiation, which extends beyond simply controlling naive T cell quiescence, a point previously emphasized primarily in the context of autoimmunity (Table 1).

Maintaining a balance between quiescent versus activating states through the presence of cognate antigens and costimulatory signals is a crucial step for T cell-mediated immunity. Disruption of this balance leads to a loss of tolerance and aggressive immune responses by T cells, resulting in lymphoma, leukemia and various autoimmune disorders. Moreover, it has been suggested that molecules involved in maintaining T cell quiescence contribute to immune regulation in the tumor context. Clinical and immunological usefulness of T lymphocytes in infection clearance, vaccination, anticancer therapy and treatment of autoimmune diseases has facilitated great advances in T cell biology focused on effector function. However, more knowledge should be gained regarding quiescence in T cells. Dissecting the mechanisms underlying the maintenance of minimalism in quiescent T cells may provide fundamental clues for future applications in T cell-based therapies.

References

Marescal, O. & Cheeseman, I. M. Cellular mechanisms and regulation of quiescence. Dev. Cell 55, 259–271 (2020).

Coller, H. A., Sang, L. & Roberts, J. M. A new description of cellular quiescence. PLoS Biol. 4, e83 (2006).

Cheung, T. H. & Rando, T. A. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 329–340 (2013).

Chapman, N. M., Boothby, M. R. & Chi, H. Metabolic coordination of T cell quiescence and activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 55–70 (2020).

Smith-Garvin, J. E., Koretzky, G. A. & Jordan, M. S. T cell activation. Annu Rev. Immunol. 27, 591–619 (2009).

Lee, S. W., Lee, G. W., Kim, H. O. & Cho, J. H. Shaping heterogeneity of naive CD8+T cell pools. Immune Netw. 23, e2 (2023).

Yang, Q., Jeremiah Bell, J. & Bhandoola, A. T-cell lineage determination. Immunol. Rev. 238, 12–22 (2010).

Germain, R. N. T-cell development and the CD4–CD8 lineage decision. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 309–322 (2002).

Zhang, S. et al. Newly generated CD4+ T cells acquire metabolic quiescence after thymic egress. J. Immunol. 200, 1064–1077 (2018).

Lewis, M., Tarlton, J. F. & Cose, S. Memory versus naive T-cell migration. Immunol. Cell Biol. 86, 226–231 (2008).

Chapman, N. M. & Chi, H. Hallmarks of T-cell exit from quiescence. Cancer Immunol. Res 6, 502–508 (2018).

Kimura, M. Y. et al. IL-7 signaling must be intermittent, not continuous, during CD8+ T cell homeostasis to promote cell survival instead of cell death. Nat. Immunol. 14, 143–151 (2013).

Sprent, J. & Surh, C. D. Normal T cell homeostasis: the conversion of naive cells into memory-phenotype cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 478–484 (2011).

Ma, A., Koka, R. & Burkett, P. Diverse functions of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-7 in lymphoid homeostasis. Annu Rev. Immunol. 24, 657–679 (2006).

Mazzucchelli, R. & Durum, S. K. Interleukin-7 receptor expression: intelligent design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 144–154 (2007).

Kondrack, R. M. et al. Interleukin 7 regulates the survival and generation of memory CD4 cells. J. Exp. Med 198, 1797–1806 (2003).

Tan, J. T. et al. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 8732–8737 (2001).

Barata, J. T., Cardoso, A. A., Nadler, L. M. & Boussiotis, V. A. Interleukin-7 promotes survival and cell cycle progression of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by down-regulating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(kip1). Blood 98, 1524–1531 (2001).

Fletcher, A. L., Acton, S. E. & Knoblich, K. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 350–361 (2015).

Masopust, D. & Schenkel, J. M. The integration of T cell migration, differentiation and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 309–320 (2013).

Mendoza, A. et al. Lymphatic endothelial S1P promotes mitochondrial function and survival in naive T cells. Nature 546, 158–161 (2017).

Myers, D. R., Norlin, E., Vercoulen, Y. & Roose, J. P. Active tonic mTORC1 signals shape baseline translation in naive T cells. Cell Rep. 27, 1858–1874 e6 (2019).

Wang, R. et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity 35, 871–882 (2011).

Michalek, R. D. et al. Cutting edge: distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J. Immunol. 186, 3299–3303 (2011).

Shyer, J. A., Flavell, R. A. & Bailis, W. Metabolic signaling in T cells. Cell Res 30, 649–659 (2020).

Dai, M. et al. LDHA as a regulator of T cell fate and its mechanisms in disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 158, 114164 (2023).

Wells, A. D. & Morawski, P. A. New roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in T cell biology: linking cell division and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 261–270 (2014).

Saxton, R. A. & Sabatini, D. M. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 168, 960–976 (2017).

Yang, K. et al. T cell exit from quiescence and differentiation into Th2 cells depend on Raptor-mTORC1-mediated metabolic reprogramming. Immunity 39, 1043–1056 (2013).

Kidani, Y. et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins are essential for the metabolic programming of effector T cells and adaptive immunity. Nat. Immunol. 14, 489–499 (2013).

Burgering, B. M. & Coffer, P. J. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature 376, 599–602 (1995).

Suzuki, A. et al. T cell-specific loss of Pten leads to defects in central and peripheral tolerance. Immunity 14, 523–534 (2001).

Inoki, K., Li, Y., Xu, T. & Guan, K. L. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 17, 1829–1834 (2003).

Pollizzi, K. N. et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 selectively regulate CD8+ T cell differentiation. J. Clin. Invest 125, 2090–2108 (2015).

Yang, K., Neale, G., Green, D. R., He, W. & Chi, H. The tumor suppressor Tsc1 enforces quiescence of naive T cells to promote immune homeostasis and function. Nat. Immunol. 12, 888–897 (2011).

Kerdiles, Y. M. et al. Foxo1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7 and interleukin 7 receptor. Nat. Immunol. 10, 176–184 (2009).

Buckley, A. F., Kuo, C. T. & Leiden, J. M. Transcription factor LKLF is sufficient to program T cell quiescence via a c-Myc-dependent pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2, 698–704 (2001).

Kuo, C. T., Veselits, M. L. & Leiden, J. M. LKLF: a transcriptional regulator of single-positive T cell quiescence and survival. Science 277, 1986–1990 (1997).

Wu, J. & Lingrel, J. B. KLF2 inhibits Jurkat T leukemia cell growth via upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1. Oncogene 23, 8088–8096 (2004).

Haaland, R. E., Yu, W. & Rice, A. P. Identification of LKLF-regulated genes in quiescent CD4+ T lymphocytes. Mol. Immunol. 42, 627–641 (2005).

Dang, C. V. c-Myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 1–11 (1999).

Bush, A. et al. c-myc null cells misregulate cad and gadd45 but not other proposed c-Myc targets. Genes Dev. 12, 3797–3802 (1998).

Jiang, W. et al. Methylation of kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) associates with its expression and non-small cell lung cancer progression. Am. J. Transl. Res. 9, 2024–2037 (2017).

Zhu, K. Y. et al. The functions and prognostic value of Kruppel-like factors in breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int 22, 23 (2022).

Preston, G. C., Feijoo-Carnero, C., Schurch, N., Cowling, V. H. & Cantrell, D. A. The impact of KLF2 modulation on the transcriptional program and function of CD8 T cells. PLoS ONE 8, e77537 (2013).

Weinreich, M. A. & Hogquist, K. A. Thymic emigration: when and how T cells leave home. J. Immunol. 181, 2265–2270 (2008).

Sebzda, E., Zou, Z., Lee, J. S., Wang, T. & Kahn, M. L. Transcription factor KLF2 regulates the migration of naive T cells by restricting chemokine receptor expression patterns. Nat. Immunol. 9, 292–300 (2008).

Takada, K. et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 is required for trafficking but not quiescence in postactivated T cells. J. Immunol. 186, 775–783 (2011).

Ouyang, W. & Li, M. O. Foxo: in command of T lymphocyte homeostasis and tolerance. Trends Immunol. 32, 26–33 (2011).

Carlson, C. M. et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature 442, 299–302 (2006).

Bai, A., Hu, H., Yeung, M. & Chen, J. Kruppel-like factor 2 controls T cell trafficking by activating L-selectin (CD62L) and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 transcription. J. Immunol. 178, 7632–7639 (2007).

Weinreich, M. A. et al. KLF2 transcription-factor deficiency in T cells results in unrestrained cytokine production and upregulation of bystander chemokine receptors. Immunity 31, 122–130 (2009).

Calnan, D. R. & Brunet, A. The FoxO code. Oncogene 27, 2276–2288 (2008).

van der Vos, K. E. & Coffer, P. J. FOXO-binding partners: it takes two to tango. Oncogene 27, 2289–2299 (2008).

Leenders, H., Whiffield, S., Benoist, C. & Mathis, D. Role of the forkhead transcription family member, FKHR, in thymocyte differentiation. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 2980–2990 (2000).

Fabre, S. et al. FOXO1 regulates L-Selectin and a network of human T cell homing molecules downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Immunol. 181, 2980–2989 (2008).

Delpoux, A. et al. FOXO1 constrains activation and regulates senescence in CD8 T cells. Cell Rep. 34, 108674 (2021).

Kim, M. V., Ouyang, W., Liao, W., Zhang, M. Q. & Li, M. O. The transcription factor Foxo1 controls central-memory CD8+ T cell responses to infection. Immunity 39, 286–297 (2013).

Ouyang, W., Beckett, O., Flavell, R. A. & Li, M. O. An essential role of the Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 in control of T cell homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity 30, 358–371 (2009).

Newton, R. H. et al. Maintenance of CD4 T cell fitness through regulation of Foxo1. Nat. Immunol. 19, 838–848 (2018).

Li, C. & Tucker, P. W. DNA-binding properties and secondary structural model of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/fork head domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 11583–11587 (1993).

Wang, B. et al. Foxp1 regulates cardiac outflow tract, endocardial cushion morphogenesis and myocyte proliferation and maturation. Development 131, 4477–4487 (2004).

Feng, X. et al. Foxp1 is an essential transcriptional regulator for the generation of quiescent naive T cells during thymocyte development. Blood 115, 510–518 (2010).

Feng, X. et al. Transcription factor Foxp1 exerts essential cell-intrinsic regulation of the quiescence of naive T cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 544–550 (2011).

Wei, H. et al. Cutting edge: Foxp1 controls naive CD8+T cell quiescence by simultaneously repressing key pathways in cellular metabolism and cell cycle progression. J. Immunol. 196, 3537–3541 (2016).

DeFrances, M. C., Debelius, D. R., Cheng, J. & Kane, L. P. Inhibition of T-cell activation by PIK3IP1. Eur. J. Immunol. 42, 2754–2759 (2012).

Muto, A. et al. The transcriptional programme of antibody class switching involves the repressor Bach2. Nature 429, 566–571 (2004).

Franke, A. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet 42, 1118–1125 (2010).

Roychoudhuri, R. et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize Treg-mediated immune homeostasis. Nature 498, 506–510 (2013).

Afzali, B. et al. BACH2 immunodeficiency illustrates an association between super-enhancers and haploinsufficiency. Nat. Immunol. 18, 813–823 (2017).

Ferreira, M. A. et al. Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13.5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet 378, 1006–1014 (2011).

International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics C. et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature 476, 214–219 (2011).

Roychoudhuri, R. et al. BACH2 regulates CD8+T cell differentiation by controlling access of AP-1 factors to enhancers. Nat. Immunol. 17, 851–860 (2016).

Tsukumo, S. et al. Bach2 maintains T cells in a naive state by suppressing effector memory-related genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 10735–10740 (2013).

Hnisz, D. et al. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155, 934–947 (2013).

Vahedi, G. et al. Super-enhancers delineate disease-associated regulatory nodes in T cells. Nature 520, 558–562 (2015).

Yao, C. et al. BACH2 enforces the transcriptional and epigenetic programs of stem-like CD8+T cells. Nat. Immunol. 22, 370–380 (2021).

Choi, J. O., Ham, J. H. & Hwang, S. S. RNA metabolism in T lymphocytes. Immune Netw. 22, e39 (2022).

Katsuyama, T., Li, H., Comte, D., Tsokos, G. C. & Moulton, V. R. Splicing factor SRSF1 controls T cell hyperactivity and systemic autoimmunity. J. Clin. Invest 129, 5411–5423 (2019).

Li, H. B. et al. m6A mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature 548, 338–342 (2017).

Marasca, F. et al. LINE1 are spliced in non-canonical transcript variants to regulate T cell quiescence and exhaustion. Nat. Genet 54, 180–193 (2022).

Hwang, S. S. et al. mRNA destabilization by BTG1 and BTG2 maintains T cell quiescence. Science 367, 1255–1260 (2020).

Winkler, G. S. The mammalian anti-proliferative BTG/Tob protein family. J. Cell Physiol. 222, 66–72 (2010).

Busson, M. et al. Coactivation of nuclear receptors and myogenic factors induces the major BTG1 influence on muscle differentiation. Oncogene 24, 1698–1710 (2005).

Rouault, J. P. et al. Interaction of BTG1 and p53-regulated BTG2 gene products with mCaf1, the murine homolog of a component of the yeast CCR4 transcriptional regulatory complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 22563–22569 (1998).

Mauxion, F., Faux, C. & Seraphin, B. The BTG2 protein is a general activator of mRNA deadenylation. EMBO J. 27, 1039–1048 (2008).

Stupfler, B., Birck, C., Seraphin, B. & Mauxion, F. BTG2 bridges PABPC1 RNA-binding domains and CAF1 deadenylase to control cell proliferation. Nat. Commun. 7, 10811 (2016).

Mlynarczyk, C. et al. BTG1 mutation yields supercompetitive B cells primed for malignant transformation. Science 379, eabj7412 (2023).

Giles, J. R. et al. Shared and distinct biological circuits in effector, memory and exhausted CD8+T cells revealed by temporal single-cell transcriptomics and epigenetics. Nat. Immunol. 23, 1600–1613 (2022).

Cuddapah, S., Barski, A. & Zhao, K. Epigenomics of T cell activation, differentiation, and memory. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 22, 341–347 (2010).

Zhu, Z. et al. FOXP1 and KLF2 reciprocally regulate checkpoints of stem-like to effector transition in CAR T cells. Nat. Immunol. 25, 117–128 (2024).

Chan, J. D. et al. FOXO1 enhances CAR T cell stemness, metabolic fitness and efficacy. Nature 629, 201–210 (2024).

Doan, A. E. et al. FOXO1 is a master regulator of memory programming in CAR T cells. Nature 629, 211–218 (2024).

Singh, M. K. et al. KLF2 enhancer variant rs4808485 increases lupus risk by modulating inflammasome machinery and cellular homoeostasis. Ann Rheum Dis 83, 879–888 (2024).

Yamada, S. et al. Forkhead box P1 overexpression and its clinicopathologic significance in peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Hum. Pathol. 43, 1322–1327 (2012).

Ren, J. et al. Foxp1 is critical for the maintenance of regulatory T-cell homeostasis and suppressive function. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000270 (2019).

Delage, L. et al. BTG1 inactivation drives lymphomagenesis and promotes lymphoma dissemination through activation of BCAR1. Blood 141, 1209–1220 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the New Faculty Startup Fund from Seoul National University (grant no. SNU-20230041), the Suh Kyungbae Foundation (grant no. SUHF-22010039), the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (grant nos. NRF-2021R1A2C2093640/RS-2021-NR059640, RS-2024-00403897, RS-2024-00398456, and RS-2025-15373099), and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant nos. HI22C0043/RS-2022-KH124476 to S.S.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, J.O., Seo, Y. & Hwang, S.S. Guardians of silence: transcriptional networks in T cell quiescence. Exp Mol Med 57, 1663–1672 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01516-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01516-y