Abstract

Melanosomes are highly specialized organelles responsible for melanin synthesis, storage and transport in melanocytes, playing a central role in pigmentation and skin homeostasis. Although melanosome biogenesis and trafficking have been well characterized, emerging evidence emphasizes the importance of melanosome degradation in regulating pigment levels. Among the degradation pathways, melanophagy—a selective form of autophagy targeting melanosomes—has recently emerged as an important mechanism for the turnover of damaged, immature, or excess melanosomes. Here we highlight current insights into melanophagy mechanisms, including molecular regulators and signaling pathways. We also discuss the potential of modulating melanophagy as a novel cosmetic or therapeutic approach for managing hyperpigmentation, offering an alternative to traditional strategies focused solely on inhibiting melanin synthesis. By emphasizing the role of organelle clearance, melanophagy provides a new paradigm in the regulation of skin pigmentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The skin is the largest organ of the body and acts as a protective barrier against environmental stress, pathogens and water loss. It also contributes to immune defense, temperature regulation and sensory functions. Structurally, the skin consists of three layers: the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis1. The epidermis is mainly composed of keratinocytes, with melanocytes and Langerhans cells playing roles in pigmentation and immune response, respectively. The underlying dermis contains fibroblasts, blood vessels and extracellular matrix proteins that provide strength and elasticity. The hypodermis, composed of fat and connective tissue, offers insulation and energy storage.

Melanosomes are highly specialized, lysosome-related organelles, approximately 500 nm in diameter, which reside in melanocytes2. These pigment granules were first noted in the 1800s but were identified as distinct organelles only in the mid-twentieth century3,4. In 1963, Seiji and colleagues proposed that these structures were unique to pigment-producing cells and introduced the term ‘melanosome’ to describe intracellular granules that harbor tyrosinase activity—key sites for melanin biosynthesis and storage5,6,7 (Fig. 1).

This timeline highlights pivotal advances in the study of melanosomes, from the initial morphological description of pigment cells in the 1840s to discoveries related to melanosome biogenesis, maturation and transport. Advances in the 2010s have shed light on the regulation of melanosome homeostasis. More recently, studies have begun to explore the role of melanophagy in the context of pigmentary disorders.

Further refined EM-based studies elaborated on the ultrastructural transitions underlying melanosome development, offering deeper insights into the molecular and cellular mechanisms governing organelle maturation and pigment deposition6,8. During the 1980s, tyrosinase was extensively characterized as the central melanogenic enzyme regulating melanin synthesis in mammals9,10, and later, studies of melanosomal matrix proteins such as premelanosome protein (PMEL/Pmel17) revealed their roles in fibril formation and melanin deposition11. Recent studies on Rab and SNARE proteins have revealed key vesicular pathways involved in melanosome transport and transfer to keratinocytes, with increasing evidence pointing to a role for extracellular vesicles in this process12,13,14. As the primary determinant of pigmentation in skin, hair and eyes, melanin plays a photoprotective role by shielding cells from ultraviolet (UV) irradiation and mechanical stress15,16. Although melanosomes share certain biogenetic and trafficking features with lysosomes, they follow a distinct, melanocyte-specific maturation process involving coordinated steps of vesicle trafficking, enzyme loading and eventual transfer to keratinocytes2,17. This process is tightly regulated by over a hundred molecular factors, and dysregulation in these pathways contributes to pigmentation disorders such as albinism18, hyperpigmentation and melanoma16,19.

In addition to biogenesis and distribution, melanosome homeostasis relies on melanophagy, first described in detail around 2011 as a form of selective autophagy targeting melanosomes20. Autophagy–lysosome fusion has been shown to drive melanosome degradation and regulate pigment levels, highlighting its physiological importance21. In addition, receptors such as optineurin (OPTN) selectively target melanosomes, underscoring the need for precise control of melanin content22,23. Dysregulated melanophagy has been implicated in vitiligo, hyperpigmentation and age-related pigmentary changes and may also affect melanoma progression by helping tumor cells adapt to stress24. Growing evidence suggests that melanophagy is regulated by upstream factors, particularly those involving stress-responsive signaling cascades and selective autophagy receptors that mediate melanosome-specific recognition. Among these, nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2 (NRF2) has been implicated in promoting melanophagy under oxidative stress, suggesting a protective role in maintaining melanocyte homeostasis25. Recently, microRNAs have also been extensively studied in relation to autophagy and melanogenesis; however, their direct involvement in the selective degradation of melanosomes remains unclear and warrants further investigation26,27,28. Most recently, our group and others have reported additional melanophagy molecular regulatory pathways, including ring finger and CHY zinc finger domain-containing 1 (RCHY1)22 and itchy E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (ITCH)23 (Fig. 2).

This figure illustrates the current understanding and conceptual models of melanophagy regulation. Ubiquitin-dependent melanophagy involves two distinct signaling pathways. a In response to β-mangostin, the E3 ubiquitin ligase RCHY1 catalyzes the K63-linked polyubiquitination of melanosomal proteins, enabling recognition by the autophagic receptor OPTN. OPTN subsequently recruits TBK1, which phosphorylates OPTN at Ser187, promoting autophagosome engagement and melanophagic flux. b Upon TCTE treatment, PTK2 is activated via phosphorylation at Tyr397 and enhances the activity of E3 ligase ITCH. The activated ITCH ubiquitinates MLANA, which is then recognized by OPTN, facilitating lysosomal degradation of melanosomes. c The ubiquitin-independent melanophagy remains hypothetical. This model proposes that melanosomal membrane proteins containing LIR motifs may directly interact with autophagy machinery, bypassing ubiquitination and receptor mediation. Although such mechanisms are established in other forms of organelle-selective autophagy, they remain unconfirmed in melanophagy and warrant future investigation.

A balanced understanding of melanosome homeostasis is important for developing better treatments for pigmentation-related conditions. Whereas traditional approaches have focused on blocking melanin production, regulating melanophagy offers a new way to manage pigment levels without interfering with other functions of melanocytes. Thus, in this Review, we highlight recent findings on how melanosomes are degraded, with a focus on melanophagy.

Melanosome biogenesis and maturation

Melanosomes are distinct organelles involved in the production and sequestration of melanin in melanocytes. Melanosome biogenesis and maturation are fundamental to pigmentation and photoprotection. The melanosome biogenesis process is tightly regulated, integrating endosomal trafficking, protein fibrillogenesis and enzymatic melanogenesis to ensure the efficient production, storage and transfer of melanin29.

Molecular mechanism for melanosome biogenesis

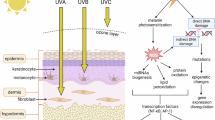

Melanogenesis, defined as the synthesis of melanin by melanocytes, is mainly driven by UV irradiation. This stimulation involves the generation of DNA photoproducts and the release of local signaling molecules. Among the various factors, α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), secreted by keratinocytes, serves as a key inducer of melanogenesis30. α-MSH binds to the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) on melanocytes, leading to the activation of cAMP-dependent signaling pathways. This signaling cascade ultimately enhances the expression of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), a master regulator of melanocyte survival, proliferation and melanin production30. MITF transcriptionally regulates a broad spectrum of target genes essential for melanocyte function. For example, MITF drives the expression of melanosomal structural and enzymatic components, including tyrosinase, tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP1), TYRP2, MLANA/MART1 and PMEL31.

The stem cell factor (SCF)–KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase (c-KIT) signaling axis is a key regulator of melanogenesis, primarily through the activation of the MAPK and PI3K pathways. The ligand-induced c-KIT autophosphorylation triggers p38 and ERK signaling, promoting CREB activation and modulating MITF levels via Ser73 phosphorylation32,33. Moreover, SCF–c-KIT signaling stabilizes β-catenin through PI3K-mediated GSK3β inhibition, a process further supported by Wnt signaling via Frizzled-1 and Dishevelled, enhancing MITF-driven transcription34.

In addition to its role in pigmentation, MITF regulates genes involved in cell cycle and survival, such as CDK2, CDKN2A and BCL231. It also controls melanocyte migration via the MET proto-oncogene and supports melanosome transport by modulating RAB27A expression35.

Morphological and functional maturation of melanosomes

Melanosomes originate from the endosomal system and mature through four stages, classified by ultrastructure and melanin content: unpigmented premelanosomes (stages I and II) and pigmented melanosomes (stages III and IV)36,37.

Stage I melanosomes arise from early endosomes and are characterized by a vacuolar appearance with a clathrin coat and limited intraluminal vesicles38. In stage II, melanosomes elongate and develop organized fibrillar structures primarily composed of PMEL, which provide a scaffold for melanin deposition39,40. Melanin synthesis begins in stage III, as enzymes such as tyrosinase, TYRP1 and TYRP2 catalyze the conversion of L-tyrosine to eumelanin or pheomelanin, depending on the context41. These enzymes localize to the melanosomal membrane and lumen, where additional regulators such as SLC45A2 and GRP143 modulate pH and organelle integrity42,43. In stage IV, dense melanin accumulation obscures internal structures, producing fully melanized, mature melanosomes44. Mature melanosomes are subsequently transported to the dendritic tips of melanocytes and transferred to keratinocytes, where they serve as photoprotective organelles by shielding nuclear DNA from UV damage29.

Melanosome degradation

In addition to melanosome biogenesis and maturation, the regulated degradation of melanosomes is essential for maintaining melanosomal homeostasis. The accumulation of dysfunctional or surplus melanosomes can compromise cellular integrity and adversely affect melanocyte function. Melanophagy—the selective autophagic degradation of melanosomes via the autophagy–lysosome system—serves as the primary mechanism for organelle turnover21,45. By contrast, the ubiquitin–proteasome system primarily targets individual melanosomal proteins such as MITF or tyrosinase for degradation46,47. Although both systems rely on ubiquitin tagging, melanophagy uniquely facilitates the removal of entire or parts of organelles, highlighting its indispensable role in melanosomal quality control and piment regulation.

Organelle-selective autophagy

Autophagy is a tightly controlled process that enables cells to adapt to stress, remove damaged components and maintain organelle integrity. It begins with recruitment of ATG proteins to form a phagophore, a double-membraned structure that encloses cytoplasmic material. This matures into an autophagosome, which fuses with a lysosome to form an autolysosome, where contents are degraded and recycled48.

Autophagosome formation is initiated by the ULK complex (ULK1/2, ATG13, FIP200 and ATG101), which is suppressed by the mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase complex 1 (mTORC1) in nutrient-rich conditions and activated during starvation49. Downstream, the class III PI3K complex promotes phagophore nucleation50. Elongation involves two conjugation systems: the ATG12–ATG5–ATG16L1 complex and ATG8 lipidation (for example, LC3 and GABARAP), catalyzed by ATG4, ATG7 and ATG351. ATG9 supplies membranes for expansion52.

Unlike nonselective autophagy, which randomly engulfs cytoplasmic material, selective autophagy is mediated by cargo recognition mechanisms involving autophagic receptors that bridge specific substrates to the core autophagic machinery53. Key autophagic receptors, including sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) and OPTN, recognize ubiquitinated cargo and facilitate its recruitment to autophagosomes through direct interactions with lipidated LC3 proteins on autophagic membrane54.

Selective autophagy encompasses a range of pathways targeting specific cellular components, such as mitophagy, lysophagy and pexophagy53. Among various forms of organelle-selective autophagy, mitophagy has been the most extensively characterized. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying mitophagy provides valuable insights into the regulation of other types of organelle-selective autophagy. Selective autophagy can be categorized into ubiquitin-dependent and ubiquitin-independent pathways, based on the mechanism of cargo recognition. In the ubiquitin-dependent pathways, substrates are tagged with ubiquitin and subsequently recognized by autophagic receptors such as SQSTM1, which bind both ubiquitin and LC3, thus tethering the cargo to autophagosomes53,55. In particular, ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy is predominantly regulated by the PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)–parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (PRKN) signaling axis, which orchestrates the selective recognition and clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria56. Upon mitochondrial depolarization, PINK1 accumulates on the outer membrane of impaired mitochondria, where it recruits and directly phosphorylates PRKN at Ser65, leading to its activation. The activated PRKN subsequently ubiquitinates outer mitochondrial membrane proteins such as MFN2, VDAC and TOMM2057. These ubiquitin signals are then recognized by LC3-interacting region (LIR)-containing autophagic receptors that facilitate mitochondrial sequestration into autophagosomes58. However, ubiquitin-independent mitophagy relied on receptors such as BNIP3, NIX and FKBP8, which directly bind to LC3 without ubiquitin tagging59. Together, these parallel mechanisms ensure specificity and adaptability in targeting diverse organelles for autophagic degradation.

Melanophagy

Melanophagy removes dysfunctional melanosomes, including immature, excess or damaged ones, in both melanocytes and keratinocytes, thereby maintaining organelle quality and pigmentation balance. When melanophagy is impaired, melanosomes accumulate abnormally, leading to pigmentation disorders such as hyperpigmentation21,45.

Melanophagy in keratinocytes

Mature melanosomes are transferred from melanocytes to surrounding keratinocytes through dendritic processes. Within keratinocytes, melanophagy plays a role in regulating epidermal pigmentation. Consistently, recent studies have revealed that the autophagic capacity of keratinocytes notably contributes to skin color variation among different ethnicities21,60. For instance, keratinocytes derived from lighter skin types display greater autophagic activity and show enhanced responsiveness to melanosome-induced autophagy compared with those from darker skin types21. This difference in autophagic potential affects the rate of melanosome degradation, ultimately determining the amount of melanin retained in the epidermis. Although these findings provide intriguing insights, they are based primarily on in vitro studies with limited donor samples. Further research involving broader populations and in vivo validation is needed to validate and expand these observations.

Further supporting evidence links autophagy to pigment regulation in keratinocytes. Functional inhibition of autophagy—either pharmacologically or via the silencing of ATGs—leads to the accumulation of melanosomes in keratinocytes, whereas the activation of autophagy reduces melanin content, as shown in both ex vivo and in vitro human skin models29. Various agents such as 5-methyl-3-tetradecylidene-dihydro-furan-2-one (DMF02)25, liensinine, neferine61, pentasodium tetracarboxymethyl palmitoyl 21 dipeptide 12 (PTPD-12)60 and even radiofrequency stimulation62 have been identified to enhance melanophagy and thereby exert antipigmenting effects in keratinocytes (Table 1). Moreover, epidermal autophagic activity has been shown to decline with aging, which impairs melanosome clearance and results in melanin accumulation—contributing to the development of hyperpigmented lesions such as senile lentigo63.

Melanophagy in melanocytes

Melanophagy also occurs within melanocytes and serves as a critical mechanism for maintaining intracellular melanin homeostasis. Several keratinocyte-derived factors, such as α-MSH, are secreted in response to UV irradiation or environmental stress and stimulate melanocyte proliferation and melanogenic enzyme expression, including tyrosinase30. Notably, recent studies have elucidated a link between tyrosinase inhibition and the activation of melanophagy. Resveratrol exhibits both the direct enzymatic inhibition of tyrosinase and the indirect transcriptional repression of melanogenic regulators including tyrosinase, TYRP1, TYRP2 and MITF in α-MSH-stimulated melanocytes64,65,66.

Furthermore, disruption of melanosome transport can lead to their accumulation in melanocytes, triggering autophagic degradation. For example, 3-O-glyceryl-2-O-hexyl ascorbate (VC-HG) has been shown to suppress melanogenesis by activating autophagy (Table 1). It disrupts melanosome transport through the downregulation of motor proteins, such as myosin Va and kinesin, leading to melanosome accumulation and subsequent degradation via autophagy67,68. These findings collectively suggest that the attenuation of melanogenesis may act as a trigger for melanophagy.

Taken together, these observations underscore distinct cell type-specific regulatory mechanisms of melanophagic flux. Keratinocytes appear inherently more active in melanosome clearance—modulated by skin phototype and aging—whereas melanocytes regulate melanophagy in response to melanin synthesis status and organelle dynamics. These differences reflect the complex interplay between pigment production and degradation pathways, suggesting that interventions targeting melanophagy should consider the unique regulatory context and clearance capacities of each cell type.

Although melanophagy is essential for melanosome homeostasis, its dysregulation has been also implicated in hypopigmentary disorders24. In vitiligo, impaired autophagy—linked to defective NRF2–SQSTM1 signaling and reduced ATG expression—renders melanocytes more susceptible to oxidative stress and apoptosis69. Conversely, excessive autophagy may also contribute to melanocyte loss in stable lesions. In tuberous sclerosis complex, mTOR hyperactivation disrupts autophagic balance and reduces melanogenesis70. These findings suggest that both insufficient and excessive melanophagy, depending on disease context, may contribute to melanocyte dysfunction and pigmentary loss.

Molecular mechanisms of melanophagy

Melanophagy is primarily regulated through a ubiquitin-dependent mechanism, in which melanosomal proteins are tagged with ubiquitin and recognized by selective autophagic receptors. By contrast, a potential ubiquitin-independent pathway—such as the direct interaction between LC3 and melanosomal membrane proteins—has not yet been investigated. Accordingly, this Review focuses on the current understanding of ubiquitin-mediated regulation of melanophagy, with particular emphasis on the roles of E3 ubiquitin ligases and autophagic receptors that coordinate melanosome degradation.

RCHY1–OPTN signaling in β-mangostin-induced melanophagy

Recent insights have revealed a ubiquitin-dependent melanophagy pathway mediated by the E3 ligase RCHY1, selective autophagic receptor OPTN and TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which collectively regulate β-mangostin-induced melanosome degradation22,71 (Fig. 2a and Table 1). β-mangostin promotes K63-linked polyubiquitination of melanosomal proteins via RCHY1, enabling their recognition by OPTN. OPTN subsequently recruits TBK1 to melanosomes, leading to TBK1-mediated phosphorylation of OPTN at Ser187, a step for autophagosome engagement and melanophagic flux. Loss-of-function of RCHY1, OPTN or TBK1 disrupts β-mangostin-induced melanosome degradation, implicating the central role of this signaling axis in melanosomal homeostasis. Conversely, the activation of this pathway significantly downregulates melanogenic proteins such as tyrosinase and PMEL17, effects reversible by autophagy inhibitors or ATG5 depletion. Although this pathway highlights the importance of ubiquitin-mediated signaling in melanophagy, the specific melanosomal membrane substrates targeted for RCHY1-mediated ubiquitination remain to be elucidated. Together, these findings position the RCHY1–OPTN axis as a key regulator of ubiquitin-tagged melanosome clearance22.

PTK2–ITCH–MLANA–OPTN axis in TCTE-induced melanophagy

In a recent study, a ubiquitin-dependent pathway, orchestrated by the PTK2–ITCH–MLANA–OPTN regulatory axis, has been suggested as a pivotal regulator of melanophagy23 (Fig. 2b and Table 1). Treatment with an antimelanogenic agent 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamate thymol ester (TCTE) primes protein tyrosine kinase 2 (PTK2) to phosphorylate the E3 ubiquitin ligase ITCH, thereby enhancing its ubiquitin-conjugating activity. The phosphorylated ITCH then ubiquitinates MLANA, a melanosomal membrane protein, tagging it for recognition by the autophagic receptor OPTN. OPTN directs the tagged melanosomes into autophagosomes, which fuse with lysosomes for the degradation of melanosomes. The inhibition or genetic ablation of PTK2 or ITCH impairs the efficiency of MLANA ubiquitination, disrupts OPTN-mediated cargo recognition and consequently reduces the overall melanophagic flux, resulting in melanosome accumulation and potential aberrant pigmentation. These findings reinforce the essential role of the PTK2–ITCH–MLANA–OPTN pathway in regulating melanophagy and maintaining pigment homeostasis.

Melanophagy-inducing agents

A growing body of evidence suggests both established and putative small molecules can induce melanophagy, contributing to pigmentation regulation. These compounds act through a variety of mechanisms, including the direct modulation of melanophagy-specific signaling or general enhancement of autophagic activity. For clarity, we divide these agents into two categories based on the strength of mechanistic evidence supporting their role in melanophagy (Table 1).

Melanophagy inducers

Several natural products and small molecules have been identified as direct inducers of melanophagy with experimental evidence supporting their role in melanosome degradation via the autophagic pathways (Table 1).

Our group previously reported that compounds such as resveratrol65, 3′-hydroxydaidzein (3′-ODI)72 and ARP10173 inhibit α-MSH-induced melanin synthesis and promote the autophagic clearance of melanosomes by downregulating key melanogenic regulators. Ultrastructural studies with electron microscopy have corroborated these effects by demonstrating the sequestration of melanosomes within autophagosomes, indicating the role of lysosomal degradation in their depigmenting effects. Recent advances have identified melanophagy-inducing agents through functional screening approaches using fluorescent reporters of autophagic flux. For instance, TCTE (also known as Melasolv)45, ursolic acid74, nalfurafine hydrochloride75, teneligliptin hydrobromide and retagliptin phosphate76 significantly reduce melanin content by enhancing melanophagic flux (Table 1). Their effects are abolished upon autophagy inhibition or ATG5 depletion. In addition, β-mangostin, a natural xanthone chemical, also suppresses melanogenesis by reducing the protein levels of tyrosinase and TYRP1 without affecting their transcription, probably through posttranslational regulation71 (Table 1). These findings underscore the biological importance of melanophagy in pigmentation regulation.

Melanophagy-inducing putative candidates

A second group of compounds has been reported to enhance autophagy and exert depigmenting effects, although direct evidence for melanosome selective degradation via melanophagy remains limited. These agents primarily target upstream regulators of autophagic flux and pigmentation rather than melanophagy-specific pathways (Table 1).

According to this notion, compounds such as isoliquiritigenin77, pterostilbene78, imperatorin79 and hinokitiol80 stimulate autophagic activity and exhibit notable skin-lightening effects by inhibiting the PI3K–AKT–mTOR signaling cascade, a key negative regulator of autophagy. Similarly, 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) enhances autophagic flux through the activation of the AMPK–ULK1 pathway, resulting in decreased melanin accumulation in melanocytes81. These findings suggest that energy-sensing and nutrient-related pathways may play a role in autophagy-mediated pigment turnover (Table 1).

In addition, the SQSTM1–KEAP1–NRF2 axis has been introduced as a key regulatory hub linking autophagy and oxidative stress responses in melanosome degradation. SQSTM1 serves as a dual-function receptor, directing polyubiquitinated KEAP1 toward autophagosomes via LC3 binding, thus relieving KEAP1-mediated repression of NRF2. Activated NRF2 subsequently translocates to the nucleus and upregulates antioxidant genes, including HO-182. Agents such as VC-HG67, coenzyme Q083, ectoine84 and ellagic acid85 have been shown to activate this pathway, contributing to autophagic activation and depigmentation (Table 1).

Although these agents engage signaling pathways that are mechanistically linked to autophagy and melanogenesis regulation, whether their effects are mediated specifically through melanophagy remains to be fully established. Further studies are warranted to determine whether these compounds promote the selective degradation of melanosomes or exert broader effects on other organelles and cellular processes.

Potential applications of melanophagy

Pigmentation homeostasis relies on a precise balance between melanosome biogenesis, maturation, transport and degradation. Notably, conventional cosmetic strategies primarily target melanin production by inhibiting enzymes such as tyrosinase and MITF. Although they are effective in suppressing melanin synthesis, these approaches frequently cause the accumulation of dysfunctional, immature stage III melanosomes, characterized by incomplete melanization and compromised cellular functions86,87. These impaired and dysfunctional melanosomes cannot properly mature or transfer to keratinocytes, necessitating their removal to avoid cellular stress and persistent pigmentation. As we discussed, melanophagy has emerged as a crucial mechanism addressing this challenge. Specifically, melanophagy degrades immature, dysfunctional or excessively produced melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes. Failure to effectively clear these melanosomes results in intracellular accumulation, disturbing pigment homeostasis and potentially exacerbating hyperpigmentation. Thus, the activation of melanophagy offers a promising approach to promote natural pigment turnover for both medical and cosmetic applications. According to this notion, recent studies highlight promising cosmetic compounds such as TCTE45 and resveratrol65, which stimulate melanophagy, reducing intracellular melanin effectively. Although these agents highlight the potential of targeting melanophagy, current evidence is largely limited to in vitro and preclinical models, and clinical validation remains lacking. Whereas melanophagy provides substrates specificity, the nonspecific activation of autophagy pathways may carry the risks, including the unintended degradation of essential organelles and disruption of cellular homeostasis. These concerns underscore the need for a deeper mechanistic understanding of melanophagy-specific regulation to enable safe and effective therapeutic strategies.

Integrating melanophagy activators with conventional melanin synthesis inhibitors may offer a dual-action strategy, simultaneously blocking pigment formation and accelerating the clearance of existing dysfunctional melanosomes. Such combined formulations could provide superior and sustained skin-brightening outcomes, addressing limitations of traditional agents that solely inhibit pigment production. Moreover, melanophagy-targeted products align with current customer trends favoring balanced, holistic skin health rather than aggressive skin-whitening strategies. To maximize both safety and efficacy, future development should prioritize delivery systems that enable skin-specific or cell type-specific activation of melanophagy pathways. Topical formulations utilizing nanocarriers, liposomes, or prodrug-based strategies may help localize activity to melanocytes or keratinocytes, thereby minimizing systemic exposure and reducing the risk of off-target effects. Advances in such precision delivery technologies will be essential for translating melanophagy from a mechanistic insight into a viable therapeutic or cosmetic modality.

Perspectives on melanophagy

Melanophagy is emerging as an essential mechanism in regulating skin pigmentation, with promising implications beyond cosmetic applications. However, several critical research questions remain. Mechanistically, current studies have focused exclusively on ubiquitin-dependent melanophagy, which involves ITCH or RCHY1. By contrast, ubiquitin-independent pathways, which are well-documented in other forms of selective autophagy such as mitophagy and ER-phagy (selective autophagy of the ER), remain uncharacterized in the context of melanosome degradation. Thus, additional studies are needed to elucidate these alternative mechanisms.

Future studies should investigate the regulation of melanophagy across different skin types and its crosstalk with other cellular degradation pathways. Understanding how stressors such as aging, inflammation and metabolic imbalance influence melanophagy may further uncover its therapeutic relevance. Clinically, melanophagy is considered as a promising target for both cosmetic enhancement and the treatment of pigmentation disorders, including vitiligo, melasma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and age-related pigmentary changes. To translate these insights into practice, the further elucidation of its molecular mechanisms, the identification of specific modulators and the development of reliable in vivo models and noninvasive monitoring tools will be essential.

Beyond pigmentation, the role of melanophagy in other pathological conditions, such as melanoma, is emerging but remains poorly understood. Whereas autophagy can both suppress tumor initiation and support tumor progression88, it is unclear whether melanophagy follows a similar context-dependent pattern. Melanosomes themselves may also exert pro- or antitumorigenic effects through their roles in redox balance and pigment metabolism. Thus, melanophagy could either enhance tumor resilience or increase the susceptibility to stress. Further investigation may uncover new therapeutic targets for tumor adaptation and resistance.

In conclusion, advancing melanophagy research may enable the development of next-generation cosmetic solutions for pigmentation control, contributing to healthier and more balanced skin.

References

Kanitakis, J. Anatomy, histology and immunohistochemistry of normal human skin. Eur. J. Dermatol 12, 390–399 (2002).

Wasmeier, C., Hume, A. N., Bolasco, G. & Seabra, M. C. Melanosomes at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3995–3999 (2008).

Westerhof, W. The discovery of the human melanocyte. Pigment Cell Res. 19, 183–193 (2006).

Birbeck, M. S., Mercer, E. H. & Barnicot, N. A. The structure and formation of pigment granules in human hair. Exp. Cell Res. 10, 505–514 (1956).

Baker, R. V., Birbeck, M. S., Blaschko, H., Fitzpatrick, T. B. & Seiji, M. Melanin granules and mitochondria. Nature 187, 392–394 (1960).

Seiji, M., Fitzpatrick, T. B. & Birbeck, M. S. The melanosome: a distinctive subcellular particle of mammalian melanocytes and the site of melanogenesis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 36, 243–252 (1961).

Seiji, M., Fitzpatrick, T. B., Simpson, R. T. & Birbeck, M. S. Chemical composition and terminology of specialized organelles (melanosomes and melanin granules) in mammalian melanocytes. Nature 197, 1082–1084 (1963).

Mund, M. L., Rodrigues, M. M. & Fine, B. S. Light and electron microscopic observations on the pigmented layers of the developing human eye. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 73, 167–182 (1972).

Korner, A. & Pawelek, J. Mammalian tyrosinase catalyzes three reactions in the biosynthesis of melanin. Science 217, 1163–1165 (1982).

Jimenez, M., Kameyama, K., Maloy, W. L., Tomita, Y. & Hearing, V. J. Mammalian tyrosinase: biosynthesis, processing, and modulation by melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 3830–3834 (1988).

Lee, Z. H. et al. Characterization and subcellular localization of human Pmel 17/silver, a 110-kDa (pre)melanosomal membrane protein associated with 5,6,-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) converting activity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 106, 605–610 (1996).

Raposo, G. & Marks, M. S. Melanosomes-dark organelles enlighten endosomal membrane transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 786–797 (2007).

Sitaram, A. & Marks, M. S. Mechanisms of protein delivery to melanosomes in pigment cells. Physiology 27, 85–99 (2012).

Waster, P., Eriksson, I., Vainikka, L., Rosdahl, I. & Ollinger, K. Extracellular vesicles are transferred from melanocytes to keratinocytes after UVA irradiation. Sci. Rep. 6, 27890 (2016).

D’Mello, S. A., Finlay, G. J., Baguley, B. C. & Askarian-Amiri, M. E. Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. Int J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1144 (2016).

Pavan, W. J. & Sturm, R. A. The genetics of human skin and hair pigmentation. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 20, 41–72 (2019).

Marks, M. S. & Seabra, M. C. The melanosome: membrane dynamics in black and white. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 738–748 (2001).

Chi, A. et al. Proteomic and bioinformatic characterization of the biogenesis and function of melanosomes. J. Proteome Res. 5, 3135–3144 (2006).

Fistarol, S. K. & Itin, P. H. Disorders of pigmentation. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 8, 187–201 (2010).

Ho, H. & Ganesan, A. K. The pleiotropic roles of autophagy regulators in melanogenesis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24, 595–604 (2011).

Murase, D. et al. Autophagy has a significant role in determining skin color by regulating melanosome degradation in keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 2416–2424 (2013).

Lee, K. W. et al. RCHY1 and OPTN are required for melanophagy, selective autophagy of melanosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2318039121 (2024).

Park, N. Y. et al. Deciphering melanophagy: role of the PTK2–ITCH–MLANA–OPTN cascade on melanophagy in melanocytes. Autophagy 21, 664–673 (2025).

Kovacs, D., Cardinali, G., Picardo, M. & Bastonini, E. Shining light on autophagy in skin pigmentation and pigmentary disorders. Cells 11, 2999 (2022).

Yun, C. Y. et al. Marliolide derivative induces melanosome degradation via Nrf2/p62-mediated autophagy. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3995 (2021).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Human amniotic stem cells-derived exosmal miR-181a-5p and miR-199a inhibit melanogenesis and promote melanosome degradation in skin hyperpigmentation, respectively. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12, 501 (2021).

Ma, Q. et al. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of autophagy. Cells 11, 441 (2022).

Hushcha, Y. et al. microRNAs in the regulation of melanogenesis. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6104 (2021).

Bento-Lopes, L. et al. Melanin’s journey from melanocytes to keratinocytes: uncovering the molecular mechanisms of melanin transfer and processing. Int J. Mol. Sci. 24, 11289 (2023).

Dall’Olmo, L., Papa, N., Surdo, N. C., Marigo, I. & Mocellin, S. α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH): biology, clinical relevance and implication in melanoma. J. Transl. Med. 21, 562 (2023).

Hsiao, J. J. & Fisher, D. E. The roles of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor and pigmentation in melanoma. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 563, 28–34 (2014).

Kawakami, A. & Fisher, D. E. The master role of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor in melanocyte and melanoma biology. Lab. Invest. 97, 649–656 (2017).

Kim, E. S. et al. Mitochondrial dynamics regulate melanogenesis through proteasomal degradation of MITF via ROS–ERK activation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 27, 1051–1062 (2014).

Phung, B., Sun, J., Schepsky, A., Steingrimsson, E. & Ronnstrand, L. c-KIT signaling depends on microphthalmia-associated transcription factor for effects on cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 6, e24064 (2011).

Chiaverini, C. et al. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor regulates RAB27A gene expression and controls melanosome transport. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12635–12642 (2008).

Seiji, M., Shimao, K., Birbeck, M. S. & Fitzpatrick, T. B. Subcellular localization of melanin biosynthesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 100, 497–533 (1963).

Raposo, G., Tenza, D., Murphy, D. M., Berson, J. F. & Marks, M. S. Distinct protein sorting and localization to premelanosomes, melanosomes, and lysosomes in pigmented melanocytic cells. J. Cell Biol. 152, 809–824 (2001).

Hurbain, I. et al. Electron tomography of early melanosomes: implications for melanogenesis and the generation of fibrillar amyloid sheets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19726–19731 (2008).

Berson, J. F., Harper, D. C., Tenza, D., Raposo, G. & Marks, M. S. Pmel17 initiates premelanosome morphogenesis within multivesicular bodies. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3451–3464 (2001).

Bissig, C., Rochin, L. & van Niel, G. PMEL amyloid fibril formation: the bright steps of pigmentation. Int J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1438 (2016).

Snyman, M., Walsdorf, R. E., Wix, S. N. & Gill, J. G. The metabolism of melanin synthesis—from melanocytes to melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 37, 438–452 (2024).

Wiriyasermkul, P., Moriyama, S. & Nagamori, S. Membrane transport proteins in melanosomes: regulation of ions for pigmentation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1862, 183318 (2020).

Bueschbell, B., Manga, P. & Schiedel, A. C. The many faces of G protein-coupled receptor 143, an atypical intracellular receptor. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 873777 (2022).

Schiaffino, M. V. Signaling pathways in melanosome biogenesis and pathology. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 1094–1104 (2010).

Park, H. J. et al. Melasolv induces melanosome autophagy to inhibit pigmentation in B16F1 cells. PLoS ONE 15, e0239019 (2020).

Ando, H., Ichihashi, M. & Hearing, V. J. Role of the ubiquitin proteasome system in regulating skin pigmentation. Int J. Mol. Sci. 10, 4428–4434 (2009).

Shi, J. et al. The ubiquitin–proteasome system in melanin metabolism. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 21, 6661–6668 (2022).

Ortega, M. A. et al. Autophagy in its (proper) context: molecular basis, biological relevance, pharmacological modulation, and lifestyle medicine. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 20, 2532–2554 (2024).

Hurley, J. H. & Young, L. N. Mechanisms of autophagy initiation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 225–244 (2017).

Mercer, T. J., Gubas, A. & Tooze, S. A. A molecular perspective of mammalian autophagosome biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 5386–5395 (2018).

Nakatogawa, H. Two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems that mediate membrane formation during autophagy. Essays Biochem. 55, 39–50 (2013).

Yamamoto, H. et al. Atg9 vesicles are an important membrane source during early steps of autophagosome formation. J. Cell Biol. 198, 219–233 (2012).

Vargas, J. N. S., Hamasaki, M., Kawabata, T., Youle, R. J. & Yoshimori, T. The mechanisms and roles of selective autophagy in mammals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 167–185 (2023).

Adriaenssens, E., Ferrari, L. & Martens, S. Orchestration of selective autophagy by cargo receptors. Curr. Biol. 32, R1357–R1371 (2022).

Khaminets, A., Behl, C. & Dikic, I. Ubiquitin-dependent and independent signals in selective autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 6–16 (2016).

Cho, D. H., Kim, J. K. & Jo, E. K. Mitophagy and innate immunity in infection. Mol. Cells 43, 10–22 (2020).

Ge, P., Dawson, V. L. & Dawson, T. M. PINK1 and Parkin mitochondrial quality control: a source of regional vulnerability in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 20 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 304 (2023).

Teresak, P. et al. Regulation of PRKN-independent mitophagy. Autophagy 18, 24–39 (2022).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Autophagy induction can regulate skin pigmentation by causing melanosome degradation in keratinocytes and melanocytes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 33, 403–415 (2020).

Geyfman, M. et al. Lotus sprout extract induces selective melanosomal autophagy and reduces pigmentation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 24, e16587 (2025).

Kim, H. M. et al. Evaluating whether radiofrequency irradiation attenuated UV-B-induced skin pigmentation by increasing melanosomal autophagy and decreasing melanin synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 10724 (2021).

Murase, D. et al. Autophagy declines with premature skin aging resulting in dynamic alterations in skin pigmentation and epidermal differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5708 (2020).

Satooka, H. & Kubo, I. Resveratrol as a kcat type inhibitor for tyrosinase: potentiated melanogenesis inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 1090–1099 (2012).

Kim, E. S. et al. Autophagy induced by resveratrol suppresses α-MSH-induced melanogenesis. Exp. Dermatol. 23, 204–206 (2014).

Lee, T. H., Seo, J. O., Baek, S. H. & Kim, S. Y. Inhibitory effects of resveratrol on melanin synthesis in ultraviolet B-induced pigmentation in Guinea pig skin. Biomol. Ther. 22, 35–40 (2014).

Katsuyama, Y., Taira, N., Yoshioka, M., Okano, Y. & Masaki, H. 3-O-glyceryl-2-O-hexyl ascorbate suppresses melanogenesis through activation of the autophagy system. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 41, 824–827 (2018).

Taira, N., Katsuyama, Y., Yoshioka, M., Okano, Y. & Masaki, H. 3-O-glyceryl-2-O-hexyl ascorbate suppresses melanogenesis by interfering with intracellular melanosome transport and suppressing tyrosinase protein synthesis. J. Cosmet. Dermatol 17, 1209–1215 (2018).

He, Y. et al. Dysregulated autophagy increased melanocyte sensitivity to H2O2-induced oxidative stress in vitiligo. Sci. Rep. 7, 42394 (2017).

Wataya-Kaneda, M. Mammalian target of rapamycin and tuberous sclerosis complex. J. Dermatol. Sci. 79, 93–100 (2015).

Lee, K. W. et al. Depigmentation of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone-treated melanoma cells by β-mangostin is mediated by selective autophagy. Exp. Dermatol. 26, 585–591 (2017).

Kim, E. S. et al. Autophagy mediates anti-melanogenic activity of 3′-ODI in B16F1 melanoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 442, 165–170 (2013).

Kim, E. S. et al. ARP101 inhibits α-MSH-stimulated melanogenesis by regulation of autophagy in melanocytes. FEBS Lett. 587, 3955–3960 (2013).

Park, H. J. et al. Ursolic acid inhibits pigmentation by increasing melanosomal autophagy in B16F1 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 531, 209–214 (2020).

Lee, H. J. et al. Nalfurafine hydrochloride, a κ-opioid receptor agonist, induces melanophagy via PKA inhibition in B16F1 cells. Cells 12, 146 (2022).

Kim, S. H. et al. Evaluation of teneligliptin and retagliptin on the clearance of melanosome by melanophagy in B16F1 cells. Cosmetics 11, 35 (2024).

Yang, Z., Zeng, B., Pan, Y., Huang, P. & Wang, C. Autophagy participates in isoliquiritigenin-induced melanin degradation in human epidermal keratinocytes through PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 97, 248–254 (2018).

Hseu, Y. C. et al. The in vitro and in vivo depigmenting activity of pterostilbene through induction of autophagy in melanocytes and inhibition of UVA-irradiated α-MSH in keratinocytes via Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathways. Redox Biol. 44, 102007 (2021).

Huang, P. et al. Imperatorin promotes melanin degradation in keratinocytes through facilitating autophagy via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 317, 70 (2024).

Tsao, Y. T. et al. Hinokitiol inhibits melanogenesis via AKT/mTOR signaling in B16F10 mouse melanoma cells. Int J. Mol. Sci. 17, 248 (2016).

Heo, H. et al. Human milk oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose promotes melanin degradation via the autophagic AMPK–ULK1 signaling axis. Sci. Rep. 12, 13983 (2022).

Komatsu, M. et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 213–223 (2010).

Yang, H. L. et al. The anti-melanogenesis, anti-photoaging, and anti-inflammation of coenzyme Q0, a major quinone derivative from Antrodia camphorata, through antioxidant Nrf2 signaling pathways in UVA/ B-irradiated keratinocytes. J. Funct. Foods 116, 106206 (2024).

Jane, W. C. et al. The in vitro and in vivo skin-whitening activity of Ectoine through enhanced autophagy in melanocytes and keratinocytes and zebrafish model. Biofactors 51, e70004 (2025).

Yang, H. L. et al. The anti-melanogenic effects of ellagic acid through induction of autophagy in melanocytes and suppression of UVA-activated α-MSH pathways via Nrf2 activation in keratinocytes. Biochem. Pharm. 185, 114454 (2021).

Fujita, H. et al. Inulavosin, a melanogenesis inhibitor, leads to mistargeting of tyrosinase to lysosomes and accelerates its degradation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 1489–1499 (2009).

Campagne, C., Ripoll, L., Gilles-Marsens, F., Raposo, G. & Delevoye, C. AP-1/KIF13A blocking peptides impair melanosome maturation and melanin synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 568 (2018).

Yun, C. W. & Lee, S. H. The roles of autophagy in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3466 (2018).

Shen, J., Jin, J., Huang, J., Guo, Y. & Qian, Q. Combining large-spot low-fluence 1064-nm and fractional 1064-nm picosecond lasers for promoting protective melanosome autophagy via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling pathway for the treatment of melasma. Exp. Dermatol 33, e15094 (2024).

Chen, S. J. et al. The anti-melanogenic effects of 3-O-ethyl ascorbic acid via Nrf2-mediated alpha-MSH inhibition in UVA-irradiated keratinocytes and autophagy induction in melanocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 173, 151–169 (2021).

Kim, A. J., Park, J. E., Cho, Y. H., Lim, D. S. & Lee, J. S. Effect of 7-methylsulfinylheptyl isothiocyanate on the inhibition of melanogenesis in B16-F1 cells. Life 11, 162 (2021).

Alam, M. B., Park, N. H., Song, B. R. & Lee, S. H. Antioxidant potential-rich betel leaves (Piper betle L.) exert depigmenting action by triggering autophagy and downregulating MITF/tyrosinase in vitro and in vivo. Antioxidants 12, 374 (2023).

Hseu, Y. C. et al. The in vitro and in vivo depigmentation activity of coenzyme Q(0), a major quinone derivative from Antrodia camphorata, through autophagy induction in human melanocytes and keratinocytes. Cell Commun. Signal. 22, 151 (2024).

Sun, L. et al. Lipopolysaccharide reduces melanin synthesis in vitiligo melanocytes by regulating autophagy. Exp. Dermatol. 31, 1579–1585 (2022).

Jeong, D. et al. Anti-melanogenic effects of ethanol extracts of the leaves and roots of Patrinia villosa (Thunb.) Juss through their inhibition of CREB and induction of ERK and autophagy. Molecules 25, 5375 (2020).

Tan, H. et al. Melanin resistance of heat-processed ginsenosides from Panax ginseng berry treated with citric acid through autophagy pathway. Bioorg. Chem. 152, 107758 (2024).

Qomaladewi, N. P., Kim, M. Y. & Cho, J. Y. Rottlerin reduces cAMP/CREB-mediated melanogenesis via regulation of autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2081 (2019).

Kim, P. S. et al. Anti-melanogenic activity of schaftoside in Rhizoma Arisaematis by increasing autophagy in B16F1 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 503, 309–315 (2018).

Cho, Y. H., Park, J. E., Lim, D. S. & Lee, J. S. Tranexamic acid inhibits melanogenesis by activating the autophagy system in cultured melanoma cells. J. Dermatol. Sci. 88, 96–102 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (grant no. RS-2024-00342057), by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (grant no. P0025489) and by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (grant nos. RS-2024-00453488 and RS-2024-00463344). This research was also supported by the ORGASIS Corporation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, N.Y., Kim, S.H., Jo, D.S. et al. Emerging perspectives on the selective autophagy of melanosomes: melanophagy. Exp Mol Med 57, 2709–2716 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01581-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01581-3