Abstract

Micro lime, hydrated lime (Ca (OH)2) with particle sizes of 1-3μ dispersed in isopropanol, can be used to reinforce deteriorated earthen structures. The consolidation effect depends on the amount of moisture present in the structure or in the ambient air. This study investigates the influence of different levels of relative humidity (RH) on the consolidation effect of micro lime on earthen structures, the chemical processes responsible for the consolidation and the physical changes to the structure. The aim is to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying chemical reactions and to identify a potential limit to the applicability of this consolidation method in low RH environments. The fact that many of these sites are located in arid climates greatly influences the practical application of micro lime in the conservation of historical earthen structures. To characterize the consolidation effect of micro lime, unconfined compressive strength and exposure to wet and dry cycles were used. The properties of the reaction products and the bonding between soil particles and micro lime were investigated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). At RH levels of 25%, 45%, 65% and 90%, the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and the modulus of deformation at 50% strength (E50) of the micro lime-reinforced specimens demonstrated an increase with humidity. This led to a significant improvement in their ability to resist the effects of dry–wet cycles. Results from thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) indicate that micro lime interacts with the soil matrix via carbonation, with the reaction rate increasing with humidity. At 25% RH, vaterite was produced and residual free lime was observed, whereas at humidity levels of 45% and above, the reaction yielded vaterite and aragonite. The lime treatment did not significantly alter the pore structure of the soil specimens. The total porosity of the specimens was only slightly reduced, with the main effect of the lime treatment being a reduction in the number of large pores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earth, implying soil, mud or clay, is one of the world's oldest building materials, and techniques for building with earth are extremely varied, ranging from mud huts to adobe and rammed earth structures. According to UNESCO's World Heritage List, over 10 per cent of the World Heritage properties are comprised of structures partially or wholly constructed with earth [1]. In China, almost thirty per cent of the inscribed sites incorporate earthen structures. A significant proportion of these sites are situated in the arid and semi-arid regions of northwestern China [2, 3]. Earthen structures are susceptible to damage and deterioration due to a number of natural factors, including wind, rain, soluble salts, temperature, earthquakes and human destructive activities [4, 5]. Repeated wetting and drying cycles of earthen structures can cause changes in the properties of earthen structures, leading to deformation [6]. The repeated cycles of salt crystallisation and dissolution caused by wind, rain, groundwater and the drying and wetting process result in the loss of strength, weathering and crumbing of earthen structures [7, 8]. The combined effect of freezing and thawing and soluble salts is also a factor that causes structural damage to earthen structures [9].

The conservation of these deteriorating historical earthen structures is a central issue in the preservation of China's cultural heritage. A variety of consolidants have been employed for strengthening earthen structures and surface protection. These have demonstrated the ability to offset the deterioration of soil structures and preserving the structural integrity of historic earthen structures in situ [10]. However, it is imperative that these conservation materials not only improve the mechanical properties and durability of the soils, but are also compatible with the original materials [11,12,13]. Significant differences in mechanical properties between reinforced and unreinforced soils can result in damage at the bond interface under stress, strain, or changes in temperature and humidity. In addition, the physical properties of the consolidated structures, including the depth of penetration, permeability and breathability, are crucial in evaluating the compatibility of a consolidation material [14].

Lime, a traditional building material, is known to effectively modify the mechanical properties and microstructure of soils [15, 16]. However, when used as a consolidant, there are several challenges to be overcome. These include the low solubility of lime in water, a slow reaction rate with CO2, and limited penetration depth [17,18,19]. Furthermore, the high volume of water introduced into the structure when using lime water for consolidation can exacerbate damage to historical earthen structures and facilitate the migration of soluble salts. Nano-lime suspensions, comprising of nano- or microscale lime particles suspended in ethanol or isopropanol, have been developed to effectively address the aforementioned issues [20, 21]. They have been successfully employed to protect a range of weathered historical surfaces, including stone, plaster, and mortar [22,23,24]. In addition to the benefits of nano-lime previously outlined, micro lime is locally available in China, making it a more sustainable and cost-effective option. Micro lime has been demonstrated to be effective in strengthening soil structures in grouting applications under high humidity conditions. Furthermore, the application of dilute micro-lime dispersions prior to grouting has been demonstrated to stabilise the internal surfaces of the voids in the historic substrates. Nevertheless, the authors propose that achieving such favourable outcomes may not be feasible in low humidity conditions [25]. When lime is added to soil, the calcium ions initially undergo cation exchange with metal ions on the surface of the clay minerals. In this cation exchange process lime dissociates into Ca2+ and OH−, the calcium ions replacing monovalent ions like Na+, Li+, etc., which are adsorbed to the clay mineral surface [26]. The diffuse hydrous double layer surrounding the clay particles is modified by the calcium ion exchange process. This alters the density of the electrical charge around the clay particles, attracting them closer together to form flocs. It is only after this exchange process is complete that lime participates in other reactions [27, 28]. In the presence of water, following the complete fixation of lime, some clay minerals dissolve in the highly alkaline environment (pH > 12) and react with calcium hydroxide (Ca (OH)2) in a pozzolanic reaction to form calcium silicate/calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C–S–H/C–A–S–H), which increases the strength and durability of the soil structure [29, 30]. In addition, during the pozzolanic reaction between lime and clay minerals, calcium hydroxide can react with carbon dioxide in the air, resulting in a carbonation process. This process results in the formation of calcium carbonate (calcite) and the release of water, which further enhances the soil’s strength [31, 32]. Lime in soil can undergo two types of reaction: carbonation and pozzolanic reaction. Both reactions require the presence of water. As the micro lime dispersion does not contain water, its reaction with the soil is limited to the soil moisture content and the ambient humidity [33,34,35,36]. This study compares the effectiveness of micro lime in consolidating earthen structures under high and low relative humidity conditions to determine its limitations. This is of particular relevance to the numerous earthen heritage sites in the arid climates of northwestern China, where the findings may reveal potential limitations of the consolidation method in relation to the climate conditions during application. The study also investigates the chemical reactions that cause the consolidation effect. Instrumental analysis is used to identify reaction products and observe changes in soil properties.

Materials and methods

Materials

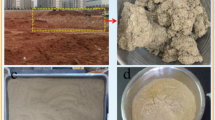

This study utilized natural clay soil from the vicinity of the Yungang Grottoes, situated in the Datong region of Shanxi Province, China. The soil was first crushed and then sieved through a 0.5 mm mesh to remove impurities, such as plant roots. In accordance with the 'Standard for geotechnical testing methods' GBT 50123-2019 [37], the basic physical properties of the soil were determined and are presented in Table 1.

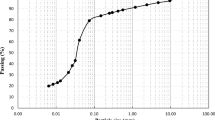

The particle size distribution of the soil was determined using a BT-9300ST Laser Particle Size Analyzer, with a soil sample of approximately 1.2 mg. The composition of the soil was determined to consist of 20.64% clay, 74.3% silt and 5.06% sand particles (Fig. 1). The soil can be classified as a silty clay soil according to the 'Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering' JTG3430-2020 [38].

The mineral composition of the clay was analysed using an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D8 ADVANCE) at the Beijing Beida Zhihui Microstructure Testing Centre. The reference intensity ratio (RIR) method [39] was employed for the quantitative analysis of the clay. This method has been widely applied for the quantification of clay minerals in soil and rocks, utilising pure α-Al2O3 (which is highly stable and widely available) as an internal standard. Oriented samples were prepared in accordance with the standardised procedure outlined in the “Analysis method for clay minerals ordinary non-clay minerals in sedimentary rocks by the X-ray diffraction” SY/T 5163-2018 [40]. The crushed and dried sample was dispersed in deionised water. Following filtration through a 270 mesh (53 μm) sieve, 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added to the beaker in order to remove organic matter. Subsequently, 2% hydrochloric acid (HCl) was added in order to remove any carbonate minerals present. The sample was then repeatedly washed with deionised water. Based on Stokes’ law, an appropriate settling time was calculated, after which the upper layer of the solution was extracted and centrifuged to obtain a clay mineral sample with a particle size of less than 2 μm. A natural oriented slide (N slide) was prepared using a scraping method, and analysed following air drying. Subsequently, the slide was saturated with ethylene glycol (EG) steam for 12 h, after which the EG-saturated slide (EG slide) was analysed. The EG slide was then subjected to a constant temperature of 500 ℃ to obtain a high-temperature slide (T slide), which was then analysed following cooling. The distinction between kaolinite and chlorite can be made by analysing the high-temperature slide (T slide), as well as by the presence of peaks at 3.58 and 3.53 angstroms. The identification of the illite–smectite mixed layer minerals is mainly reliant on the expansion of the EG slide and the contraction of the T slide. The analysis revealed that non-clay minerals constituted 80% of the soil, primarily composed of quartz, feldspar, calcite, and amphibole. Clay minerals constituted the remaining 20%, including illite, illite–smectite mixed layer minerals, and trace amounts of kaolinite and chlorite (as detailed in Table 2).

The study used micro lime dispersions, specifically the Bioline® series designated as NML-10, NML-15 and NML-25, which were supplied by the Shanghai Desaibao Building Materials Company, Ltd. [41]. The designation represents 10 g/L, 15 g/L, and 25 g/L micro lime, respectively dispersed in isopropanol. The particle size distribution of the micro lime was determined using a Malvern Mastersizer Hydro 2000MU particle size analyser. The lime particles ranged in size from 0.04 μm to 2.6 μm, with an volume average size of 0.14 μm (Fig. 2).

Preparation of the test specimens

The natural soil was crushed and sieved (using a 0.5 mm sieve) to remove plant roots and stems. In the context of earthen construction, such as rammed earth and adobe bricks, natural clay soil is typically mixed with sand. To simulate such a structure, the specimens were prepared from a mixture of soil and sand with a ratio of 2.5:1 (clay soil to sand). This ratio exhibited satisfactory working properties, allowing the creation of consistent specimen cubes upon the addition of water, determined by the plastic limit test results of the mixture. The added water resulted in a moisture content of 16% in the mixture. The mixture was then sealed and left to stand for 24 h, covered with plastic sheeting. Standard moulds (5 × 5 × 5 cm) were then filled with the mixture, and a static compaction method, namely a manual hydraulic press, was used to compact the mixed sand and soil. A static pressure of 10 kPa on the mould plunger for 1 min has been demonstrated to produce the desired compaction, resulting in stable specimen with a similar density, but not too dense to show clear before-and-after effects of the consolidation intervention. In accordance with the standards set forth in GBT 50123-2019 [37], three samples were subjected to testing for dry density via the ring knife method, resulting in an average dry density of 1.71 g/cm3, with a standard deviation of 0.05. The soil specimens were dried at a room temperature of approximately 25 °C and 60% RH for a period of 1 week prior to reinforcement.

Experimental humidity and reinforcement protocol setup

The experimental low humidity levels were based on the environmental humidity characteristics of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, China, which represents an earthen heritage site located in an arid desert climate. The average monthly humidity at the Mogao Grottoes is below 30%, with a maximum of 59% [42]. The experimental humidity levels were set to RH25%, RH45%, RH65%, and RH90% to enable comparison of lime stabilisation on clay between high, medium and low RH conditions. To achieve the desired experimental humidity settings, specially designed constant temperature and humidity chambers were employed.

For each humidity group, 36 specimens were consolidated using one of the three different concentrations of micro lime dispersion and then cured in a climate chamber with constant humidity for either 7 or 28 days before testing. The specimens were consolidated by evenly dripping 25 mL of micro lime concentrations of 10 g/L, 15 g/L, and 25 g/L onto each of their six surfaces, ensuring even penetration. Subsequently, all samples were placed in the climate chamber with the constant RH of their respective test group. The procedure was repeated on the following day, and then a third time on the third day. The specimens were then subjected to a curing period of 7 and 28 days, respectively, under constant temperature conditions (30 ℃) and humidity conditions of their respective test group. The sample numbers were designated as RHX-Y–Z, where X denotes the humidity level, Y denotes the curing time, and Z denotes the micro lime concentration.

Experimental methods

The depth of penetration of the micro lime dispersions was evaluated after uniformly dripping them on all surfaces, and prior to the specimens being placed in a constant humidity environment for curing. The samples were cut once the isopropanol had evaporated. Subsequently, phenolphthalein reagent was applied, and the area of micro lime penetration was indicated by magenta staining. The depth of penetration was quantified by measuring the distance from the edge of the sample to the visible limit of the magenta staining.

In accordance with the experimental methodology proposed by Ying et al. [43]. The specimens were subjected to dry–wet cycles following 28 days of curing under varying humidity conditions and treatment with varying concentrations of micro lime dispersions. The weight of each specimen was recorded, and photographs were taken to document their morphology. The specimens were placed on a permeable stone which had been saturated with distilled water, allowing capillary action to wet the specimens. The specimens were then dried in a constant temperature oven set at 30 °C and the weight of each specimen was recorded again after drying. This process was repeated ten times over a ten-day period, with each cycle consisting of a single wet-dry cycle. Photographs were taken to document the morphological characteristics of the specimens.

The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of all specimens, consolidated with the three concentrations of micro lime dispersion, was tested after curing for 7 and 28 days. The test was conducted using a universal testing machine (MTS-Model E44) at a constant rate of 0.02 mm/s. The UCS was determined by measuring the peak stress, and the average value was calculated from the strengths of three samples. The calculation of the modulus of deformation at 50% strength (E50) involved dividing 50% of the peak stress by the corresponding strain [44].

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was employed to qualitatively analyse the mineral composition of the reinforced samples. The FT-IR analysis was conducted within the spectral range of 400–4000 cm−1 using an iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The powdered samples were prepared from fragments of the reinforced specimens, which were removed following the uniaxial compression testing.

The qualitative analysis of the reaction products of micro lime in soil by FT-IR was employed to inform the quantitatively analyses of the reaction products, conducted via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). Samples were obtained from the reinforced specimens, which had been cured for 7 and 28 days under varying humidity conditions. This was achieved by removing fragments from their surface and grinding them to powder. TGA testing was conducted using a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC3 instrument. Approximately 30 mg of the powdered sample were placed in an aluminium crucible and analysed under a nitrogen atmosphere. The measurement programme was set to a temperature range of 25 °C to 1000 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

The porosity and pore size distribution of the specimens before and after the consolidation treatment were investigated by Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) [20, 45]. Samples for MIP measurements were extracted from both the surface and interior of the consolidated specimen groups (RH25-28-25, RH25-28-10, RH90-28-25), and a blank control group, resulting in twelve sample cubes with a side length of 1 cm. MIP is a method that is widely used for the assessment of pore size distribution in porous media [46]. This technique is based on the principles of capillary action, which govern the penetration of non-wetting liquids, such as mercury, into pores [47]. The Washburn equation is used to establish the relationship between applied pressure and pore size, assuming that all pores are cylindrical [48]:

The pore size is determined by the surface tension of mercury (0.485 N/m) and the contact angle between mercury and soil (130°). Three samples, each with a diameter of approximately 4 mm, were extracted from the consolidated groups and coated with gold for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using SU8l cold field emission scanning electronic display.

Results

Penetration depth

Figure 3 shows the depth of penetration of the micro lime dispersions in the soil specimens. The specimens were bisected through the centre and phenolphthalein was applied to the cross sections. A magenta colour indication is evident in the centre of all specimens treated with the three different micro lime concentrations. The pH values measured from samples removed from the specimens treated with lower concentrated micro lime solutions were found to be relatively close to 8.3 (8.4 and 8.46 respectively). In contrast, the pH of the samples treated with the 25 mg/L solution was found to be 10.8, which explains the observed difference in colour intensity of the indicator solution [49]. At lower lime concentrations, the magenta colour was lighter (Fig. 3a and b), yet a faint magenta hue remained evident at the centre of all specimens. This hue is very faint for specimens of the 10 g/L group (Fig. 3a) due to the lower pH described above and the colour of the soil. However, with the naked eye, a faint hue was clearly visible also in areas close to the specimen centre as indicated with red arrows. This indicates that the micro lime dispersion was able to fully penetrate the soil specimens used in this experiment, regardless of the concentration level. The penetration depth of micro lime in the specimen produced in this experiment was found to be above 2.5 cm.

Mercury intrusion analysis

Figure 4 shows the pore size distributions of both the micro lime-treated and untreated samples, taken from the surface and central parts of the soil specimens. Following a curing period of 28 days under different humidity conditions, the pore size distribution in both treated and untreated specimens exhibited three distinct peaks, corresponding to small pores (0.01–5 μm), medium pores (5–20 μm) and large pores (20 μm to 360 μm).

A statistical analysis of the mercury intrusion data from reinforced and unreinforced specimens revealed that there were three distinct pore size ranges. The results are presented in Table 3. In comparison to the control group, the pore size variation in the central part of the reinforced specimens differs from that in the surface area. In the central region, there is a reduction in macropores, an increase in mesopores, and a consistent or slightly diminished number of small pores. In contrast, the surface area of the reinforced sample exhibits a reduction in macropores, an increase in mesopores, and an increase in small pores. Table 4 presents the porosity and pore structure characteristics of both the untreated and treated specimens. The mean diameter and total pore volume of all reinforced samples exhibited a slight reduction in comparison to the unreinforced samples.

Although micro lime fills proportions of the large pores, its effect on the overall porosity of the soil is not significant. This indicates that the consolidation treatment does not significantly alter the water vapor permeability, which is an important factor for compatible consolidation treatments.

Unconfined compressive strength

Figure 5 shows the stress–strain curves of soil specimens reinforced with different concentrations of micro lime under different relative humidity conditions and subjected to either 7 or 28 days of curing. These curves are influenced by a number of factors, including relative humidity, micro lime dispersion concentration and curing time. For lime-reinforced specimen, an increase in relative humidity was found to be correlated with an increase in the peak compressive stress of the soil specimens after 7 and 28 days of curing. The variation in peak compressive stress became more pronounced with higher or lower concentrations of micro lime dispersion. For the unreinforced control group, however, this is different. When soil with a high clay content is subjected to a low humidity environment, the evaporation of water from the soil is accelerated, which results in a lower moisture content in the soil exposed to low humidity [50]. The compressive strength of soil is influenced by its moisture content. As moisture content decreases, compressive strength increases [51]. A similar trend was observed in the stress–strain curves of the control group. As humidity decreased, the peak compressive stress of the control group increased.

For specimens cured for seven days under lower relative humidity (RH 25%), there was no significant change in peak compressive stress across different micro lime concentrations, as shown in Fig. 5a. However, under 45% RH and 65% RH, the peak compressive stress of the consolidated specimens has increased slightly and shows an increasing trend with increasing micro lime concentration compared to the control specimen, as show in Fig. 5b, c. In the context of high humidity conditions (90% RH), the peak stress point indicates a significant increase in peak compressive stress compared to the control groups, as shown in Fig. 5d. After 28 days of curing, the specimens consolidated with different concentrations of micro lime and stored in an environment with a humidity of 45% or above showed a notable increase in maximum stress. At the same time, a reduction in peak strain was observed compared to the control group, as shown in Fig. 5b–d. Conversely, a marginal increase in compressive strength was observed when the specimens were stored at a relative humidity of 25%. The compressive strength is relatively high compared to the specimen stored at a higher relative humidity, as previously discussed. However, there is no notable impact on the compressive strength from the lime treatment.

Figure 6a, b illustrates the correlation between unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and both concentration and humidity following curing periods of 7 and 28 days under different humidity conditions. Significant differences in UCS changes were observed between high and low humidity environments were observed during the shorter 7-day curing period. Figure 6c, d presents the average compressive strength and the increase in compressive strength relative to the control group. The compressive strength of the specimens cured for 7 days at 25% RH did not exhibit a significant increase with lime concentration. The increase in compressive strength of specimens treated with all three concentrations of micro lime did not exceed 10%. In contrast, at 45% RH, the increase in compressive strength of the reinforced specimens did not exceed 10% when treated with 10 g/L and 15 g/L, but 17% when reinforced with 25 g/L. When subjected to 65% RH and 90% RH, the increase in compressive strength of the 10 g/L reinforced specimen did not exceed 10%. However, there was an increase in strength of approximately 13% and 17% when reinforced with 15 g/L and 25% and 27% when reinforced with 25 g/L. After a curing period of 28 days, specimens subjected to both high and low humidity conditions exhibited a notable increase in compressive strength. At 25% RH, the trend of UCS with increasing concentration exhibited a flattening between 15 g/L and 25 g/L, with the increase in compressive strength of the reinforced specimen being less than 20%. At 45% RH, the increase in UCS for micro lime-reinforced soil at a concentration of 10 g/L was relatively modest, registering at only 19.81%. This figure is 6.01% lower than the increase observed under RH65% conditions and 9.66% lower than that under high humidity (RH90%). As the micro lime concentration increases, this difference becomes more pronounced. For instance, at a concentration of 25 g/L, the increased difference in UCS of the specimen cured at RH25% and those cured at higher humidity levels, RH65% and RH90%, is 32.64% and 37.39%, respectively. The increase in UCS of the reinforced sample under 90% RH with its control group was 53.51% (as shown in Fig. 6d). The relationship between micro lime concentration and UCS exhibits a positive trend. As mentioned above, for the lime-reinforced specimens, an increase in humidity accelerates the increase in compressive strength. The difference between the reinforced specimens at different lime concentrations gradually increases. On the other hand, at lower humidity conditions, a longer time is required to show an increase in strength, as shown in Fig. 6c, d.

Figure 7a, b illustrates the correlation between E50, micro lime concentration, and RH following a 7-day and 28-day curing period under high and low humidity conditions. The influence of relative humidity on E50 was comparable to that on the UCS. Moreover, higher humidity levels enhanced the impact of the micro lime and hastened the evolution of E50 in specimens reinforced with different micro lime concentrations. Conversely, when relative humidity is low, it takes longer for the E50 to demonstrate significant changes with different micro lime concentrations, as shown in Fig. 7c, d.

Figure 8a–d shows the correlation between unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and the modulus of deformation at 50% strength (E50) for specimens consolidated with varying quantities of micro lime under different humidity conditions. A linear ascending trend in E50 is observed in the consolidated specimens with increasing micro lime concentrations across different humidity conditions, which corresponds to an elevation in UCS. The correlation was modelled using a linear function, resulting in R2 values ranging from 0.932 to 0.998. The observations presented in Fig. 5 indicate that the peak stress point of the stress–strain curve shifts to the upper left with the introduction of micro lime. This suggests that the incorporation of micro lime results in a gradual reduction in plasticity and an increase in brittleness of the soil with increased curing time. This finding is consistent with previous research [52]. In the presence of high relative humidity, the growth rate of UCS and E50 in the reinforced soil specimens is accelerated, resulting in a marked decrease in plasticity and an increase in brittleness. Conversely, under low humidity conditions, the growth of UCS and E50 in the reinforced soil is slower, resulting in a minimal impact on the soil's mechanical properties.

Wet-dry cycle

Figure 9 shows the cumulative mass loss percentage of the specimens, reinforced with different concentrations of micro lime and cured for 28 days under different RH conditions, after being exposed to 10 dry–wet cycles. The specimens consolidated with micro lime demonstrated significantly enhanced dry–wet cycling stability in comparison to the untreated control specimen. The control specimen developed cracks after the first cycle and disintegrated during the second wetting process. Although the micro lime-treated specimens experienced some mass loss, mainly after two to three cycles, they did not crack. The mass loss was primarily due to the detachment of particles at the bottom edge of the sample. As the humidity and lime concentration increase, the number of soil particles that separate from the matrix at the bottom gradually decreases, indicating that the reinforced specimens have better durability as humidity and lime concentration increase, as shown in Fig. 9b. Figures 10a, b illustrate the representative morphological changes observed in the RH65-15 specimen following ten dry–wet cycles. During the process of wet and dry cycles, particles at the bottom of the reinforced specimen gradually fall off, resulting in a missing part of the specimen as shown in Fig. 10b.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

In order to gain further insight into the soil–lime reaction under the given conditions in this study, FT-IR was conducted on samples from specimens of the respective testing groups that had been cured for 28 days. The resulting spectra are shown in Fig. 11. The FT-IR results indicate the presence of characteristic peaks corresponding to calcium carbonate. These findings provide evidence that the primary reaction pathway of micro lime in soil is carbonation, and that no indications for any reaction products of the pozzolanic reaction are present.

The absorption band at 3641 cm−1 is characteristic of the ν OH O–H stretching of the Ca (OH)2 [53], while the absorption bands at 1430 and 875 indicate the presence of vaterite and aragonite respectively [54, 55]. The absorption bands observed at 1430 cm−1 and 3640 cm−1 in Fig. 11a indicate a weak carbonation reaction of micro lime at 25% humidity, resulting in the formation of residual micro lime and vaterite. At a humidity of 45% or above, the absorption bands at 1430 cm−1and 875 cm−1 become more pronounced with increasing micro lime concentration, resulting in the formation of vaterite and aragonite, as illustrated in Fig. 11b–d. The results of FT-IR indicate that micro lime primarily undergoes a carbonation reaction in soil.

The band at 1002 cm−1 is attributed to asymmetrical stretching vibrations of the Si–O group. The bands at 796 cm−1 and 525 cm−1 are attributed to the bending Si–O vibration in quartz and clay minerals, respectively [53].

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The findings of the FT-IR analysis demonstrated that micro lime primarily undergoes carbonation reactions in soil. Thermogravimetric analysis was employed to quantify changes in calcium carbonate content, thereby characterising the rate of the micro lime carbonation reaction under varying humidity levels.

Figure 12a–d presents the TGA and DTG curves of specimens treated with different concentrations of micro lime and subjected to the different relative humidity conditions. The DTG curves reveal three distinct endothermic temperature ranges, approximately 0–120 °C, 200–390 °C, and 600–800 °C. These temperature ranges are associated with specific processes: the release of free water in soils, the release of interlayer water in soils, the dehydration of Ca-hydrates, and the decarbonation of CaCO3 (calcium carbonate) [56,57,58,59]. The temperature range of 200–390 °C is also associated with the decomposition of organic matter [60]. The weight loss observed between 350 °C and 400 °C is typically attributed to the decomposition of Ca (OH)2. At a humidity level of 25%, a small flat peak is observed within this temperature range, indicating the presence of Ca (OH)2. This finding is consistent with the results obtained from the FT-IR analysis. Although the FT-IR results did not indicate the presence of calcium hydrates, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) revealed a gentle peak in the range of 200–390 °C, which became more pronounced with increasing humidity. Three thermogravimetric tests were conducted on all experimental and control specimens, which were maintained at 90% RH for 1 month. The mean mass loss within this temperature range was determined. The results, depicted in Fig. 13a, demonstrate that under high humidity conditions, the mass loss in the control group within this temperature range aligns closely with the highest value observed in the high humidity (90% RH) experimental group. Furthermore, the mass loss value decreases as humidity decreases. This indicates that the observed mass loss is likely due to the water absorption of clay minerals, thereby excluding the possibility of the presence of calcium hydrates. In order to quantify the amount of calcium carbonate, the mass loss of both the experimental and the control groups in the temperature range of 600–800 °C was statistically analysed. The results, presented in Fig. 13b, indicate that the total content of reaction products increased with increasing curing age, micro lime concentration, and relative humidity.

The CaCO3 content of specimens cured under 25%, 45%, and 65% RH conditions was found to be significantly influenced by both the micro lime concentration and curing age. Nevertheless, at 90% RH, the CaCO3 content was not significantly affected by curing age. In conditions of 90% RH, no significant differences were identified between the two curing times with regard to calcium carbonate content. This indicates that the micro lime undergoes a rapid chemical reaction, with the reaction being completed within seven days. As the humidity decreases, the difference in calcium carbonate content between the two curing cycles also decreases, indicating that as the humidity decreases, the time required for the carbonation reaction gradually increases. While a reduction in RH can result in longer reaction times, there is still a considerable increase in calcium carbonate content compared to the control group after 28 days of curing at both 45% RH and 65% RH. However, at 25% RH, the increase in calcium carbonate is relatively low in comparison to the other humidity levels. The results of the thermogravimetric analysis demonstrates that the relative humidity conditions exert a significant influence on the carbonation reaction rate of micro lime in soil with carbon dioxide.

SEM

Figure 14 shows the microstructure and morphology of the reaction products in specimens consolidated with 25 g/L micro lime after 28 days of curing at RH conditions of 25%, 45%, 65% and 90%, and the control group. In the low humidity (25%) test group, minerals with spherical, plate-like, and botryoidal shapes were observed as shown in (Fig. 14d). The spherical minerals were identified as vaterite, the plate-like minerals as free residual lime particles, and the botryoidal shapes as ammonium calcium carbonate [61,62,63,64]. The SEM images of the test group under conditions of 45% humidity or higher revealed the presence of aragonite and vaterite. Furthermore, the reaction products of micro lime particles were observed to be interlocked and aggregated (Fig. 14f, h, j). In contrast, at low humidity, the reaction products aggregated into aggregates of varying sizes and were loosely stacked together (Fig. 14d). The red areas indicated in Figs. 14c are indicative of the reaction products of micro lime present within the gaps of soil particles. Alternatively, they are aggregated at the edges of pores (Fig. 14i). Figure 14f illustrates a mixed aggregate of aragonite and vaterite adhering to soil particles and accumulating in gaps between the particles. Lanzón et al. [24] propose that micro lime particles adhere to the soil matrix due to surface defects or differential suction, filling pores, cracks, and interfacial transition zones. The reaction products of micro lime can effectively reinforce degraded porous materials by bonding particles or filling pores [65].

Discussion

The micro lime dispersion was observed to effectively penetrate the soil specimens produced in this study. The mechanical properties of the lime-treated soil specimens were found to be significantly affected by relative humidity, as evidenced by the UCS and E50 of the specimens treated with various concentrations of micro lime and cured at different humidity levels. As humidity levels rise, the strength differential between specimens reinforced with varying concentrations of micro lime becomes increasingly pronounced. This results in a reduction of the curing time required for strength improvement. Additionally, the resistance of micro lime-strengthened soil specimens to water-induced damage during dry–wet cycling is significantly enhanced. At low RH, the strength and resistance of the specimens increased only slightly compared to the control group without micro lime. However, their resistance to wet-dry cycles still shows improvement.

Depending on the required strength gain in relation to site specific conditions, the consolidation effect may vary between locations due to variations in clay minerals present. Variations in the reactivity of the soil are related to amount and type of clay minerals present. In general, for the reaction between lime and clay it is known that the amount of lime required to stabilize a clayey soil is related to the proportion of clay minerals present and the cation exchange capacity of a soil [27]. This means the reaction between lime and clay can vary depending on differences in clay minerals present. Differences in the properties of micro-lime mixed with different types of clay soils to test water free lime-mud infection grouts for the consolidation of earthen plasters showed, that formulations with different the amount of lime did not impact the workability of the wet grouts, but resulted in significant differences in their strength and adhesion after curing [25].

The results of the FT-IR analysis indicated that micro lime undergoes carbonation in soil, whereas the anticipated pozzolanic reaction did not occur. In conditions of low humidity (25%), the reaction rate is slow, resulting in the presence of residual free lime in the soil and the formation of vaterite. At humidity levels of 45% or above, the reaction products include aragonite and vaterite. SEM images revealed the presence of ammonium calcium carbonate (ACC) under low humidity conditions and aragonite and vaternite under higher humidity conditions. Consequently, the results of the FT-IR and SEM analyses indicate that the reaction products of micro lime in soil with different humidities can be categorised as follows: under low humidity (25%), vaterite, unreacted lime (free lime), and ACC are present; whereas at 45% or higher humidity, aragonite and vaterite form. This phenomenon is similar with the findings of López Arc [64] et al. Micro lime reacts to form aragonite and vaterite, rather than directly forming calcite. Rodriguez et al. [61] propose that this is related to the alcohol adsorbed on lime particles, the carbonation process follows the Ostwald's step rule, through the sequence: ACC → vaterite → aragonite → calcite. A quantitative analysis using TGA demonstrated that the carbonation reaction rate of micro lime in soil is enhanced by higher humidity, resulting in the generation of more carbonation products. These carbonation products reinforce the soil by bonding of soil particles or filling the pores, a process also described by Hansen et al. [66]. Furthermore, a comparison of the weight loss of the control group stored under high humidity conditions with that of the experimental group samples in the TGA curve revealed that the pronounced gentle peak observed between 200 and 390 °C with increasing humidity is related to the release of absorption water within the clay minerals.

This study investigates how humidity affects the strength, resistance to wet and dry cycles, reaction types, and microstructure of micro lime reinforced soil matrices. It is important to note that the degradation of historical earthen structures is influenced by various factors, including water, soluble salts, and low winter temperatures. This study does not include on-site experiments. Further research is necessary to investigate the durability of micro lime reinforced soil against various environmental factors. Other site-specific differences in soil properties, such as varying levels of soil compaction impacting the permeability of micro lime in the soil matrix, have to be considered.

The laboratory results are relevant to the further onsite field testing of micro lime consolidation of weakened earthen heritage structures. For example, the results show that the micro lime consolidation of the soil specimen resulted in a gradual reduction in their plasticity and increased brittleness as the curing time increased. In conditions of high relative humidity, the reduction in plasticity can be considerable. These findings have significant implications for the use of lime stabilisation in historic earthen structures, particularly for more elastic earthen components such as mud plaster layers. Without a comprehensive investigation into study of the effect the impact of selected consolidation methods on the modulus of elasticity in specific site conditions and with local clay materials, there is a potential risk of subsequent damage in the form of stresses between consolidated and unconsolidated substrates.

Conclusion

Previous studies have indicated that micro lime reinforcement of earthen structures has proven effective. In order to assess the applicability of the consolidant for heritage sites in arid climates, this study investigates the impact of humidity on the effectiveness of micro lime reinforcement in compacted soil matrices. Furthermore, the underlying processes leading to consolidation were investigated through a series of instrumental analysis methods: The study validates the effectiveness of micro lime in reinforcing degraded compacted soils through the dry–wet cycle test and unconfined compressive strength testing. Furthermore, the use of TGA and FT-IR analysis, SEM imaging and MIP provides valuable insights into the reaction characteristics, bonding forms of micro lime within these simulated soil matrices, and microstructural changes. This helps to explain the impact of humidity on the strength of reinforced compacted soil matrices. It was observed that a consolidation effect was evident for all concentrations, even at 25% RH. However, the stabilisation effect was found to be lower. The findings indicate that the use of micro lime for reinforcement is limited in environments with low humidity. The extent of this limitation is contingent upon site conditions and the desired strength of the intervention. It can be concluded that, even in high humidity environments, there is insufficient water present for pozzolanic reactions to occur between micro lime dispersions and the clay soil used in this study. The research has significant value in advancing the evaluation of the applicability of micro lime for the consolidation of earthen structures under different relative humidity conditions. The study leads to the following conclusions:

-

(1)

Even at the lowest concentration of micro lime at 25% RH, an improved resistance to the effects of dry–wet cycles is still evident compared to the control group. The strength of the micro lime-consolidated specimen at 45% RH and above significantly increased with higher concentrations of micro lime and longer curing times. The presence of humidity served to accelerate the observed changes in strength, with the differences in strength between specimens with varying concentrations of micro lime becoming more pronounced. The intensity growth rate, which is defined as the rate of change in strength, ranges from 12.45% to 53.51%.

-

(2)

The relative humidity level influences the carbonation reaction of micro lime within the soil matrix. At a humidity level of 25%, micro lime undergoes a carbonation reaction, forming vaterite and ACC, while residual free lime is also found. At humidity levels of 45% or above, vaterite and aragonite are formed, which were also observed to be interlocked and aggregated. As humidity levels increase, the rate of the reaction also intensifies. This results in an increase in the quantity of reaction products, which adhere to the soil matrix and fill in the pores. This process contributes to the consolidation of the soil matrix.

-

(3)

Micro lime application has a negligible impact on the pore characteristics of degraded compacted soil. The overall reduction in porosity is minimal, with the primary effect being a decrease in the number of large pores. Additionally, an increase in the number of small pores is observed under high moisture conditions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TGA:

-

Thermogravimetric analysis

- MIP:

-

Mercury intrusion porosimetry

- SEM–EDS:

-

Scanning electron microscopy combined with energy dispersive spectroscopy

- UCS:

-

Unconfined compressive strength

- E50 :

-

Deformation modulus

- PSD:

-

Pore size distribution

- RH:

-

Relative humidity

References

Centre UWH. World Heritage Earthen Architecture Programme (WHEAP). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/earthen-architecture/.

Zhang D-X, Wang T-R, Wang X-D, Guo Q-L. Laboratory experimental study of infrared imaging technology detecting the conservation effect of ancient earthen sites (Jiaohe Ruins) in China. Eng Geol. 2012;125:66–73.

Chen W-W, Zhang Q-Y, Liu H-W, Guo Z-Q. Feasibility of protecting earthen sites by infiltration of modified polyvinyl alcohol. Constr Build Mater. 2019;204:410–8.

Li D-D, Peng E-X, Chou Y-L, Hu X-Y. A study on stability of earthen site restoration by solidified soil containing calcined ginger nuts. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2023;19: e02506.

Richards J, Wang Y, Orr S, Viles H. Finding common ground between United Kingdom based and Chinese approaches to earthen heritage conservation. Sustainability. 2018;10:3086.

Han W-C, Gong R-M, Liu Y, Gao Y-B. Influence mechanism of salt erosion on the earthen heritage site wall in Pianguan Bastion. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17: e01388.

Gupta S, Pel L, Kopinga K. Crystallization behavior of NaCl droplet during repeated crystallization and dissolution cycles: an NMR study. J Cryst Growth. 2014;391:64–71.

Flatt RJ. Salt damage in porous materials: how high supersaturations are generated. J Cryst Growth. 2002;242:435–54.

Pu T-B, Chen W-W, Du Y-M, Li W-J, Su N. Snowfall-related deterioration behavior of the Ming Great Wall in the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Nat Hazards. 2016;84:1539–50.

Elert K, Pardo ES, Rodriguez-Navarro C. Alkaline activation as an alternative method for the consolidation of earthen architecture. J Cult Herit. 2015;16:461–9.

Wang X-D, Zhang B, Pei Q-Q, Guo Q-L, Chen W-W, Li F-J. Experimental studies on sacrificial layer in conservation of earthen sites. J Cult Herit. 2020;41:74–83.

Stazi F, Nacci A, Tittarelli F, Pasqualini E, Munafò P. An experimental study on earth plasters for earthen building protection: the effects of different admixtures and surface treatments. J Cult Herit. 2016;17:27–41.

ICOMOS CHINA. Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China .2015.

Han P-Z, Zhang H-B, Zhang R, Tan X, Zhao L-Y, Liang Y-G, Su B-M. Evaluation of the effectiveness and compatibility of nanolime for the consolidation of earthen-based murals at Mogao Grottoes. J Cult Herit. 2022;58:266–73.

Stazi F, Nacci A, Tittarelli F, Pasqualini E, Munafò P. New nanolimes for eco-friendly and customized treatments to preserve the biocalcarenites of the “Valley of Temples” of Agrigento. Constr Build Mater. 2021;306: 124811.

Greaves HM. An introduction to lime stabilisation. In: Rogers CDF, Glendinning S, Dixon N, editors. Lime stabilisation. London: Thomas Telford Publishing; 1996. p. 5–12.

Brajer I, Kalsbeek N. Limewater absorption and calcite crystal formation on a limewater-impregnated secco wall painting. Stud Conserv. 1999;44:145–56.

Zhu J-M, Zhang P-Y, Ding J-H, Dong Y, Cao Y-J, Dong W-Q, Zhao X-C, Li X-H, Camaiti M. Nano Ca (OH)2: a review on synthesis, properties and applications. J Cult Herit. 2021;50:25–42.

Lopez-Arce P, Zornoza-Indart A. Carbonation acceleration of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles: induced by yeast fermentation. Appl Phys A. 2015;120:1475–95.

Otero J, Starinieri V, Charola AE. Nanolime for the consolidation of lime mortars: a comparison of three available products. Constr Build Mater. 2018;181:394–407.

Dei L, Salvadori B. Nanotechnology in cultural heritage conservation: nanometric slaked lime saves architectonic and artistic surfaces from decay. J Cult Herit. 2006;7:110–5.

Taglieri G, Daniele V, Rosatelli G, Sfarra S, Mascolo MC, Mondelli C. Eco-compatible protective treatments on an Italian historic mortar (XIV century). J Cult Herit. 2017;25:135–41.

Pondelak A, Kramar S, Kikelj ML, Sever SA. In-situ study of the consolidation of wall paintings using commercial and newly developed consolidants. J Cult Herit. 2017;28:1–8.

Lanzón M, Stefano VD, Gaitán JCM, Cardiel IB, Gutiérrez-Carrillo ML. Characterisation of earthen walls in the Generalife (Alhambra): microstructural and physical changes induced by deposition of Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles in original and reconstructed samples. Constr Build Mater. 2020;232: 117202.

Schwantes G, Dai S-B. Research on water-free injection grouts using sieved soil and micro-lime. Int J Archit Heritage. 2017;11:933–45.

Shahzada OM, Yousuf A. Stabilisation of soils with lime: a review. J Mater Environ Sci. 2020;11(9):1538–51.

Bell FG. Lime stabilization of clay minerals and soils. Eng Geol. 1996;42:223–37.

Al-Mukhtar M, Lasledj A, Alcover J-F. Behaviour and mineralogy changes in lime-treated expansive soil at 20°C. Appl Clay Sci. 2010;50:191–8.

Karnland O, Olsson S, Nilsson U, Sellin P. Experimentally determined swelling pressures and geochemical interactions of compacted Wyoming bentonite with highly alkaline solutions. Phys Chem Earth, Parts A/B/C. 2007;32:275–86.

Das G, Razakamanantsoa A, Herrier G, Deneele D. Compressive strength and microstructure evolution of lime-treated silty soil subjected to kneading action. Transp Geotech. 2021;29: 100568.

Rodriguez-Navarro C, Vettori I, Ruiz-Agudo E. Kinetics and mechanism of calcium hydroxide conversion into calcium alkoxides: implications in heritage conservation using nanolimes. Langmuir. 2016;32:5183–94.

Das G, Razakamanantsoa A, Saussaye L, Losma F, Deneele D. Carbonation investigation on atmospherically exposed lime-treated silty soil. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17: e01222.

Gomez-Villalba LS, López-Arce P, AlvarezdeBuergo M, Fort R. Structural stability of a colloidal solution of Ca(OH)2 nanocrystals exposed to high relative humidity conditions. Appl Phys A. 2011;104:1249–54.

Gomez-Villalba LS, López-Arce P, Fort R. Nucleation of CaCO3 polymorphs from a colloidal alcoholic solution of Ca(OH)2 nanocrystals exposed to low humidity conditions. Appl Phys A. 2012;106:213–7.

Daniele V, Taglieri G. Nanolime suspensions applied on natural lithotypes: the influence of concentration and residual water content on carbonatation process and on treatment effectiveness. J Cult Herit. 2010;11:102–6.

Zhang Z, Zheng K, Chen L, Yuan Q. Review on accelerated carbonation of calcium-bearing minerals: carbonation behaviors, reaction kinetics, and carbonation efficiency improvement. J Build. 2024;86: 108826.

GBT 50123–2019, Standard for geotechnical testing Method.China,2019.

JTG3430-2020, Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering. China,2020.

de Woolf PM, Visser JW. Absolute Intensities - outline of a recommended practice. Powder Diffr. 1988;3:202–4.

SY/T5163-2018, Analysis method for clay minerals ordinary non-clay minerals in sedimentary rocks by the X-ray diffraction. National Energy Administration China, 2018.

Shanghai DS Building Materials Co. Ltd. Ca (OH)2 with micro and nano particles in isopropanol: Bioline NML-010/15/25, Art. No. 8301/8302 /8303.

Wang W-F, Ma Y-T, Ma X, Wu F-S, Ma X-J, An L-Z, Feng H-Y. Seasonal variations of airborne bacteria in the Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2010;64:309–15.

Ying Z, Cui Y-J, Benahmed N, Duc M. Changes of small strain shear modulus and microstructure for a lime-treated silt subjected to wetting-drying cycles. Eng Geol. 2021;293: 106334.

Horpibulsuk S, Suddeepong A, Chinkulkijniwat A, Liu MD. Strength and compressibility of lightweight cemented clays. Appl Clay Sci. 2012;69:11–21.

Otero J, Starinieri V, Charola AE. Influence of substrate pore structure and nanolime particle size on the effectiveness of nanolime treatments. Constr Build Mater. 2019;209:701–8.

Lu S-G, Malik Z, Chen D-P, Wu C-F. Porosity and pore size distribution of Ultisols and correlations to soil iron oxides. CATENA. 2014;123:79–87.

Zhang Q, Chen W, Zhang J. Wettability of earthen sites protected by PVA solution with a high degree of alcoholysis. CATENA. 2021;196: 104929.

Zhou J, Ye G, Van Breugel K. Characterization of pore structure in cement-based materials using pressurization–depressurization cycling mercury intrusion porosimetry (PDC-MIP). Cem Concr Res. 2010;40:1120–8.

Petrusevski V, Risteska K. Behaviour of phenolphthalein in strongly basic media. Chemistry. 2007;16(4):259–66.

Yang Z-M, Cheng Q, Tang C-S, Tian B-G, Zhang X-Y. Coupled effects of temperature and relative humidity on desiccation curling of a clayey soil. Eng Geol. 2023;327: 107370.

Feng D, Liang B, Sun W, He X, Yi F, Wan Y. Mechanical properties of solidified dredged soils considering the effects of compaction degree and residual moisture content. Dev Built Environ. 2023;16: 100235.

Eades JL, Grim RE. A quick test to determine lime requirements for lime stabilization. Highw Res Rec. 1966;139:61–72.

Guerrero A, Goñi S, Moragues A, Dolado JS. Microstructure and mechanical performance of belite cements from high calcium coal fly ash. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;88:1845–53.

Yang T, Ma X, Zhang B-J, Zhang H. Investigations into the function of sticky rice on the microstructures of hydrated lime putties. Constr Build Mater. 2016;102:105–12.

Yousuf M, Mollah A, Hess TR, Tsai Y-N, Cocke DL. An FTIR and XPS investigations of the effects of carbonation on the solidification/stabilization of cement based systems-Portland type V with zinc. Cem Concr Res. 1993;23:773–84.

Jia Q-Q, Chen W-W, Tong Y-M, Guo Q-G. Strength, hydration, and microstructure properties of calcined ginger nut and natural hydraulic lime based pastes for earthen plaster restoration. Constr Build Mater. 2022;323: 126606.

Al-Mukhtar M, Lasledj A, Alcover JF. Lime consumption of different clayey soils. Appl Clay Sci. 2014;95:133–45.

Robin V, Cuisinier O, Masrouri F, Javadi AA. Chemo-mechanical modelling of lime treated soils. Appl Clay Sci. 2014;95:211–9.

Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki P. Physico-chemical and mechanical characterization of hydraulic mortars containing nano-titania for restoration applications. Cem Concr Compos. 2013;36:33–41.

Chauhan R, Kumar R, Diwan PK, Sharma V. Thermogravimetric analysis and chemometric based methods for soil examination: application to soil forensics. Forensic Chem. 2020;17: 100191.

Rodriguez-Navarro C, Elert K, Ševčík R. Amorphous and crystalline calcium carbonate phases during carbonation of nanolimes: implications in heritage conservation. CrystEngComm. 2016;18:6594–607.

Brečević L, Nielsen AE. Solubility of amorphous calcium carbonate. J Cryst. 1989;98:504–10.

Rodriguez-Navarro C, Ilić T, Ruiz-Agudo E, Elert K. Carbonation mechanisms and kinetics of lime-based binders: an overview. Cem Concr Res. 2023;173: 107301.

López-Arce P, Gómez-Villalba LS, Martínez-Ramírez S, De Buergo MÁ, Fort R. Influence of relative humidity on the carbonation of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles and the formation of calcium carbonate polymorphs. Powder Techno. 2011;205:263–9.

Rodriguez-Navarro C, Suzuki A, Ruiz-Agudo E. Alcohol dispersions of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles for stone conservation. Langmuir. 2013;29:11457–70.

Hansen E, Doehne E, Fidler J, Larson J, Martin B, Matteini M, Rodriguez-Navarro C, Pardo ES, Price C, de Tagle A, et al. A review of selected inorganic consolidants and protective treatments for porous calcareous materials. Stud Conserv. 2003;48:13–25.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Ms Yue Zhang, Associate Professor at the Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Shanghai University, for providing valuable insights during the discussion of the experimental procedures.

Funding

This research was supported by Grant No. 521110134 of the National Natural Science Foundation Project for Foreign Research Scholars ( ).

).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GS conceived the research programme; GS and ZR conceived and designed the analyses. ZR performed the laboratory experiments and analyses. GS and ZR were jointly responsible for the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, R., Schwantes, G. Investigation of the effect of relative humidity on micro lime consolidation of degraded earthen structures. Herit Sci 12, 267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01361-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01361-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative analysis of physical characteristics of traditional rammed earth dwellings in Macau

npj Heritage Science (2025)