Abstract

Temperature changes during the chemical corrosion of stone cultural relics affect the condensation and evaporation of water and chemical reactions between soluble substances and corrosive solutions. This ultimately leads to changes in the internal structure and composition of the artifacts, which in turn lead to changes in the microstrain of cultural relics. To obtain in-situ real-time information on changes in the temperature and microstrain of stone cultural relics during chemical corrosion damage, a fiber Bragg grating (FBG) detection system was developed. The detection principle for the temperature and microstrain of sandstone was provided. Thermal field emission scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and mercury intrusion porosimetry were used to characterize the surface morphology, composition, and pore structure of the sandstone samples, respectively. The temperature and microstrain changes of the sandstone samples under deionized water with different acidic/alkaline and salt solutions and at different temperatures were examined online in situ using the FBG measurement system. The results indicate that the dissolution of sandstone in the acidic solution (H2SO4 and NaHSO4) resulted in an exothermic chemical reaction as well as the dissolution of sandstone in the neutral salt solution (Na2SO4) and alkaline solution (NaOH and Na2CO3) led to material conversion and exothermic chemical reaction; the deionization reaction belongs to the dissolution reaction. The NaHSO4 solution caused the most serious corrosive disease on the sandstone surface. When the temperature of the NaHSO4 solution was 60 °C, the temperature and microstrain of the sandstone reached 63.9 °C and 253.6 με, respectively. The results of this study can support the research of revealing the corrosion mechanism of sandstone in different environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stone cultural relics are a nonrenewable and precious cultural resource as well as the historical root of inheriting and promoting an excellent traditional culture [1]. However, owing to the influence of changing global climate and environment, acidic and alkaline gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere. The interaction of these harmful gases with water molecules produces corrosive acids and alkaline compounds, causing chemical corrosion damage to stone cultural relics [2]. To effectively prevent the chemical corrosion disease on stone cultural relics, accurate detection of changes in parameter of the stone cultural relics disease to analyze its disease mechanism is highly essential [3].

The current technology available for the online detection of stone cultural relic disease parameters primarily includes infrared spectroscopy, ultrasonic detection methods, ground-penetrating radar, scratch detection techniques, and three-dimensional (3D) laser scanning. Among them, infrared spectroscopy is primarily used for ancient wall paintings and statue surface coatings and can realize the qualitative and quantitative detection of the composition of substances in stone samples [4,5,6]. Ultrasonic detection methods are mainly used for stone monuments, stone carvings, and grottoes and can characterize the internal mechanical properties and defect distribution of cultural relics [7,8,9]. Ground-penetrating radar is predominantly used for internal fissures of ancient city walls, internal structures, and water content detection in archaeological exploration and can realize real-time display of images and high-resolution detection of cultural relics [10,11,12]. Various scratch detection techniques are developed for the detection of the characteristics of scratches in different cultural relics [13]. 3D laser scanning is mainly used for large immovable stone cultural relics, such as Longmen Grottoes, Leshan Buddha, and other large stone Buddha statues, and can achieve the accurate extraction of cultural relics of color, material, surface morphology, spatial structure, and other information [14,15,16]. However, the aforementioned detection techniques have hardly been used for in-situ real-time detection of parameter changes in the body of cultural relics.

Accurately detecting the changes in temperature and microstrain in the ontological disease process of stone cultural relics is key to revealing the influence of the composition and temperature of corrosive solutions on the corrosion rate of stone artifacts [17]. This is because temperature changes during the chemical corrosion of stone cultural relics affect the condensation and evaporation of water, expansion and contraction, and chemical reactions between soluble substances and acid and alkali gases (acid and alkali compounds) [18, 19]. This ultimately leads to changes in the internal structure and composition of the artifacts, which in turn lead to changes in the microstrain of cultural relics [20]. Therefore, accurate in situ detection of temperature and microstrain changes in cultural relics is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms behind the deterioration of stone cultural relics.

Fiber Bragg grating (FBG) is utilized for temperature and microstrain detection and has found widespread applications in infrastructure, environmental protection, and life sciences [21,22,23,24]. FBG offers several advantages, including rapid response speed, long-distance transmission, microstructure, in situ monitoring, and quasi-distributed measurement [25,26,27,28]. However, there are limited reports on its application for detecting temperature and microstrain of stone cultural relics during chemical corrosion processes. In our previous work, although FBG sensors were developed for in-situ monitoring of temperature and microstrain in sandstone during oxalic acid corrosion processes, the temperature range was limited to 20–25 °C [29]. Meanwhile, although FBG sensors have been used for in-situ monitoring of temperature and microstrain of stone cultural relics subjected to corrosion at different temperatures (− 10–60 °C), the corrosion liquids were limited to deionized water and NaOH solution. Specifically, in situ monitoring of temperature and microstrain changes in corrosion process of stone cultural relics by neutral, strongly acidic and alkaline, and acidic and alkaline salt solutions under the action of high and low temperatures has not been reported. In addition, the surface morphology, material composition and pore structure of sandstone after high and low temperature corrosion by different corrosion liquids are rarely reported. Another important fact is that stone cultural relics in the field are facing the risk of acid, alkali and salinization corrosion because the discharge of chemical pollutants by metallurgical, petrochemical, papermaking, oil refining, and other enterprises alters the composition and pH of water [30]. Therefore, to reveal the corrosion mechanism of different corrosion liquids on stone cultural relics at high and low temperatures, it is necessary to use the FBG to construct an FBG sensor system for the in-situ real-time detection of temperature and microstrain in stone cultural relics. Furthermore, changes in morphology, composition, and pore structure of stone cultural relics should be investigated when the stones were subjected to corrosion by different neutral, acidic, and alkaline corrosive solutions with high and low temperatures.

This research aims to reveal the corrosion mechanism of sandstone in acid, alkali and salt environments, first, sandstone samples were prepared and a simulation system for the chemical corrosion of stone relics was constructed. Second, FBGs were used to construct a real-time in situ detection system for sandstone samples. Third, a theoretical model for measuring the changes in stone relics was developed, and temperature and microstrain calibrations of the sensors were performed. Fourth, the morphology and composition of the sandstone samples were characterized using thermal-field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and pressure pumping (MIP). Finally, the FBG detection system was used to detect the temperature and surface microstrain changes of sandstone samples under different corrosion fluids and corrosion temperatures in situ online, and the acid–base corrosion mechanism and rule of the sandstone samples were analyzed.

Sample preparation and test methods

Experimental materials

The chemicals used in the experiment included H2SO4 (1 mol/L), NaOH (4% w/v), NaHSO4 (0.1 mol/L), Na2CO3 (1 mol/L), Na2SO4 and (1 mol/L), which were purchased from Aladdin, China. The FBGs were purchased from Beijing Tongwei Co., Ltd. The fiberoptic cladding of the FBGs was made of acrylate, which had a 3-dB bandwidth of 0.24 nm. The fiberoptic cladding diameter, core diameter, and grating area length of the FBGs were 125 μm, 10 μm, and 10 mm, respectively.

Preparation of sandstone samples

Sandstone samples that replaced the stone cultural relics were purchased from Shandong Yuze Stone Co. (China). According to the XPS analysis (Fig. S1), the main components of the sandstone were quartz (silicon dioxide) and feldspar (a mineral containing magnesium, sodium, calcium, potassium, and aluminum). The sandstone samples were cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm. To completely remove impurities such as soil and salts attached to the surface of the sandstone samples, the samples were cleaned in an ultrasonic cleaner (ultrasonic power of 240 W and ultrasonic frequency of 40 kHz) for 60 min before etching. The etched sandstones were dried in a constant-temperature drying oven (110 °C) for 6 h and then cooled and preserved in a zip-lock bag for spare parts.

Corrosion solution preparation

To reveal the influence of corrosion temperature on the corrosion of sandstone, refrigerators, and electrically heated constant-temperature drying ovens were used to simulate the natural environment. The corrosive environment of sandstone samples was processed by freezing, thawing, and high temperature; the corrosive environment of sandstone temperature varied from − 10 °C to 60 °C. Furthermore, to reveal the influence of the corrosion solution composition and pH on sandstone corrosion, acidic corrosion solutions with a pH of 3 and 5 were prepared using deionized water and H2SO4. Alkaline corrosion solutions with a pH of 9, 11, and 13 were prepared using deionized water and NaOH. Acid salt corrosion solutions with a pH of 3 and 5 were prepared using deionized water and NaHSO4. Alkaline salt corrosion solutions with a pH of 9 and 11 were prepared using deionized water and Na2CO3. A neutral salt corrosion solution (pH = 7) was prepared using deionized water and Na2SO4.

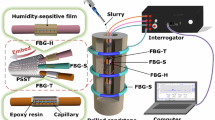

Preparation of FBG temperature and microstrain sensors

The purchased FBGs were used as the temperature and microstrain sensors, respectively. In situ decoding of temperature, to ensure that both ends of FBG are in a freely extended state, the two ends of the FBG were tightly attached to the sandstone using benzalkonium chloride stickers and degreased cotton (Fig. 1a). The fixed-temperature FBG was used to respond only to changes in sandstone temperature and was not affected by the microstrain generated by sandstone deformation because both ends of the fiber grating are in a state of free extension. Therefore, they were named FBG temperature sensors. In situ decoding of microstrain, the FBG sensors were fixed on the sandstone surface as follows: First, a ring-shaped optical fiber with the FBGs was wound on the surface of sandstone samples. The optical fiber connection was then fixed using a nylon tie. Finally, an ultraviolet shadowless adhesive was coated on the connection to ensure that the optical fiber connection did not slip off. They were named FBG strain sensors because both ends of the FBG are firmly fixed to the rock surface, these FBG respond to both rock strain and cultural changes. The height difference between the microstrain–temperature FBG sensors was approximately 23 mm (FBG_S3 was appropriately 32 mm away from the bottom of the sandstone), as shown in Fig. 1b.

In situ detection of temperature and microstrain of sandstone samples

The detection system primarily consisted of three microstrain–temperature FBG sensors, an FBG temperature sensor, a fiber grating demodulator (TV125-100), containers, a corrosive solution, a refrigerator, and an electrically heated constant-temperature drying box (Fig. 1). The light source bandwidth, wavelength resolution, and sampling time interval of the demodulator were 1500–1600 nm, 1 pm, and 1 s, respectively.

For the sandstone corrosion process, the sandstone was placed in a closed polypropylene reaction vessel. The level of the corrosion liquid in the vessel was 120 mm, which means that the sandstone sample was completely immersed in the corrosion solution. The freezing and warming experiments were realized using a refrigerator (− 10–0 °C) and an electrically heated thermostatic drying oven (0–60 °C). The freezing time was 12 h, and the temperature of the electrically heated thermostatic drying oven was warmed up at intervals of 10 °C; the temperature was warmed up to the specified temperature each time and was maintained at that temperature for 5 h. In the experiments, the drift of the wavelength outputs of three FBG microstrain-temperature sensors was detected by using the fiber grating demodulator.

Morphology and composition characterization methods of sandstone samples

The surface morphologies of the sandstone samples with thickness of 1 mm were characterized using a Gemini300 thermal field emission scanning electron microscope and a matching Oxford X-MAX energy spectrum analysis system. XRD analysis was performed using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer with a tube current of 40 mA, tube voltage of 40 kV, Cu target wavelength of 1.5406 Å, Co target wavelength of 1.79026 Å, and scanning speed of 2°/min. XPS analysis was conducted using a ThermoFisher Nexsa photoelectron spectrometer with Mo target Kα radiation. The binding energy of the sample was calibrated with the carbon peak C1s (284.6 eV) serving as the internal standard. The pore size distribution of the sandstone samples was analyzed using a high-performance fully automated mercury piezometer (mercury intrusion porosimetry [MIP]; AutoPore V9620). The volume of the sandstone samples for XRD, XPS, and MIP was 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm.

Detection principle of the temperature and microstrain of sandstone samples

When the FBG was fixed to the surface of the sandstone sample using a ring (Fig. 1) and immersed in different water chemical environments, the sandstone underwent expansion and contraction, the fiberoptic ring was subjected to radial stress, and the FBG was stretched. The Bragg wavelengths of the FBGs red-shifted under axial strain. Simultaneously, the sandstone sample reacted chemically with the corrosive solution and the temperature changed, causing the FBG resonance center wavelength to drift. Therefore, the FBGs fixed on the sandstone surface using a ring structure were influenced by the binary parameters of temperature and microstrain. In the sandstone corrosion process, to realize the accurate detection of the temperature and microstrain binary parameters of the sandstone acid and alkali corrosion processes, it is necessary to additionally set up an FBG that is not affected by the expansion of the sandstone as a temperature compensation unit (Fig. 1). A temperature compensation FBG was used to eliminate the interference of temperature on the measurement of the microstrain of the sandstone and obtain the temperature change of the body of the sandstone.

To eliminate the interference generated by the temperature on the sandstone’s microstrain measurements, an FBG with free growth was used as the temperature compensation unit (Fig. 1). The functional relationship between the wavelength drift (∆λB,T) of the resonance center and temperature variation (∆T) is described as,

where KT,1 is the temperature-sensitivity coefficient of the FBG temperature-compensation unit. When the FBG is jointly affected by the microstrain and temperature, the relationship between the wavelength drift (∆λB) of the FBG and the changes of ∆T and strain change ∆ε is expressed as,

where KS denotes the strain sensitivity coefficient, KT,2 is the temperature-sensitivity coefficient of the FBG fixed to a ring on the sandstone surface. From Eqs. 1 and 2, the following matrix was obtained:

The sensitivity coefficients KT,1, KT,2, and KS of the FBGs to the temperature and microstrain can be experimentally determined. In this study, the sensitivity coefficients KS of the ring-fixed FBG to microstrain, the temperature sensitivity coefficient KT,2, and the temperature sensitivity coefficients of the temperature-compensated unit KT,1 were 1.23 pm/με, 9.52 pm/°C, and 9.42 pm/°C, respectively. By incorporating these coefficients into Eq. 3, the following matrix is obtained:

To obtain further information about the temperature and microstrain changes during the corrosion process of the sandstone, matrix 4 was further inverted as follows:

Matrix 5 shows that the FBG demodulator (Fig. 1) can be used to detect the variations in the FBG resonant center wavelength fixed on the sandstone surface as well as those in the FBG resonant center wavelength of the temperature compensation unit. This indicates that the FBGs used in this study can accurately measure the temperature and microstrain binary of sandstone bodies.

Results and discussion

Morphology and composition characterization of sandstone

To determine the effect of the corrosion solution on the structure and material composition of the sandstone samples after corrosion, the sandstone samples were first immersed in deionized water (pH = 7), Na2SO4 solution (pH = 7), NaHSO4 solution (pH = 3 and 5), Na2CO3 solution (pH = 9 and 11), H2SO4 solution (pH = 3, 5), and NaOH solution (pH = 9, 11, and 13). First, the corrosion reaction was performed in a freeze–thaw corrosion reaction for 7 days (maintained in a refrigerator environment from – 10 to 0 °C for 12 h, maintained at room temperature at 20 °C for 12 h, and finally operated according to this cycle for 7 days). Second, the corroded samples were dried in a vacuum drying oven, and the surface morphology and composition were characterized using SEM-coupled point EDS (Fig. 2); the compositional proportions of the different elements in the sandstone samples are given in Table S1. Third, its composition was analyzed using XRD mineralogical analysis (Fig. 3). Finally, the pore size distribution was analyzed using the mercuric pressure (Fig. 4).

Morphology and elemental changes of sandstone samples. a Camera photos of sandstone samples and the sandstone after being subjected to different corrosive solutions; b SEM and EDS images of sandstone samples before corrosion; c–h SEM and EDS images of sandstone samples subjected to 7-day freeze–thaw cyclic corrosion with (c) deionized water, (d) Na2SO4, (e) NaHSO4, (f) Na2CO3, (g) H2SO4, and (h) NaOH solutions

In Fig. 2a, the first row from left to right shows the physical photographs of the sandstone samples and the sandstone samples subjected to Na2SO4, NaHSO4, and Na2CO3, respectively. The second row from left to right shows the physical photographs of the sandstone samples and the sandstone samples subjected to deionized water, H2SO4, and NaOH solutions, respectively. Figure 2b shows that sandstone samples that did not undergo corrosion damage had a densely layered structure. The sandstone samples primarily contained Al, Si, Ca, Na, K, Mg, C, and O, indicating that the sandstone samples were aluminosilicate minerals containing SiO2 and Ca, Na, and K as well as trace elements such as Mg. Figure 2c shows that, when the sandstone samples were subjected to deionized water erosion, the sandstone laminations became loose owing to the dissolution of soluble materials within the sandstone while being treated with freeze–thaw cycles, resulting in the sandstone laminations becoming loose. Figure 2d shows that, when the sandstone samples were corroded by the Na2SO4 salt solution, the original layered structure was maintained. However, the structure became fuzzy, and the sandstone samples adhered to the surfaces of the corrosion products. The EDS results showed that the new S elements (8.34 atom%) and the relative percentage of Na elements (12.75 atom%) increased, which was attributed to the soluble material in the sandstone samples reacted with the Na2SO4 to generate crystalline salts such as CaSO4 [31]. Figure 2e shows that, when the sandstone samples were corroded by the NaHSO4 salt solution, the lamellar structure almost disappeared. This can be attributed to the strong acidity of NaHSO4, which chemically dissolved with the soluble materials in the sandstone, and the pore structure collapsed and clogged after being subjected to freeze–thaw cycles (contraction and expansion). The EDS characterization results showed that, after the sandstone samples were corroded by NaHSO4, no S was detected in the samples, and the relative percentages of Mg, Al, and K were decreased (Table S1). These facts further confirm that the soluble materials in the sandstone samples were chemically soluble in NaHSO4 rather than being transformed into sediments by chemical reactions.

Figure 2f shows that, when the sandstone samples were corroded by the Na2CO3 salt solution, the sandstone maintained its original texture structure but salt crystals were attached. The EDS characterization showed a significant increase in the percentage content of Ca (2.50 atom%), indicating that the sandstone reacted with the Na2CO3 salt solution and may have generated CaCO3. Figure 2g shows that, when the sandstone samples were corroded by the H2SO4 solution, the original texture of the sandstone disappeared, and new pores were created. The sandstone placed in the H2SO4 solution underwent a strong chemical dissolution reaction. The percentage contents of Mg, Al, Si, and K in the EDS characterization decreased in the same proportion relative to those shown in Fig. 2b and Table S1, and an increase in a new element of S was observed (0.12 atom%), further confirming that the sandstone underwent a dissolution and corrosion chemical reaction with H2SO4. Figure 2h shows that, when the sandstone samples were corroded by the NaOH solution, the original texture of the sandstone was destroyed, and the original pores collapsed owing to the action of freeze–thaw cycles and were blocked by the corrosion products. These findings indicate that, under the action of strong alkali, the soluble salts in the sandstone and NaOH solution underwent a strong chemical reaction of material conversion to generate sediments. Furthermore, after the sandstone underwent corrosion in the NaOH solution, the percentages of all elements changed (Table S1). This further indicates that, owing to the action of NaOH, salt minerals were converted into sediments.

Figure 3a shows that, after 7 days of freeze–thaw cycle corrosion of sandstone samples in deionized water, the relative percentages of KAlSi3O8 and SiO2 increased and NaAlSi3O8 was detected on the sandstone surface. These results further confirmed that the sandstone dissolved in deionized water and that a small amount of corrosion products (metallic aluminosilicates) adhered to the surface of the sandstone under the action of freeze–thaw cycles. Figure 3b shows that, after 7 days of freeze–thaw cyclic corrosion of sandstone samples in the Na2SO4 neutral salt solution, the relative percentage of SiO2 increased (CaAl2Si2O8 increment was the most obvious) and CaSO4 was detected on the sandstone surface. These results confirmed that the sandstone underwent a material transformation reaction under the action of Na2SO4. Water-insoluble CaAl2Si2O8 and CaSO4 crystallized on the sandstone surface after the sandstone was subjected to freeze–thaw cyclic treatment and affected the internal pore structure of the sandstone (Fig. 2d). Figure 3c shows that, after 7 days of freeze–thaw cyclic corrosion of sandstone samples in the NaHSO4 acidic salt solution, the relative percentages of potassium feldspar and NaAlSi3O8 decreased and increased, respectively, and no S-bearing crystalline salt was observed. This confirmed that the sandstone reacted with NaHSO4 only via dissolution chemical corrosion.

Figure 3d shows an increase in the relative percentage of CaCO3 after 7 d of freeze–thaw cyclic corrosion of sandstone samples in Na2CO3 alkaline salt solution. The results prove that the sandstone underwent a chemical reaction of material exchange with Na2CO3; thus, the intrinsic structure of the sandstone was not significantly altered (Fig. 2f). Figure 3e shows that after seven days of freeze–thaw cyclic corrosion of sandstone samples in H2SO4 solution, the percentage content of various aluminosilicate minerals decreases and the percentage content of SiO2 increases. This confirms that the sandstone underwent a chemical reaction of material dissolution with H2SO4, and a new pore-like structure was formed under the freeze–thaw cyclic treatment (Fig. 2g). Figure 3f shows that CaMg(AlSiO4)2 and NaAlSi2O6 were generated after 7 days of freeze–thaw cyclic corrosion of the sandstone samples in NaOH solution. This proves that the sandstone undergoes a chemical reaction of material transformation with NaOH, which leads to the disappearance of the sandstone laminar structure and becomes sparse under the freeze–thaw cyclic treatment (Fig. 2h).

Figure 4a shows that, after 7 days of H2SO4 solution corrosion, the small pore size diameter at the largest distribution in the sandstone samples increased, that was, from 26 to 33 nm. The medium size diameter at the peak distribution in the sandstone samples increased slightly, that was, from 221 to 227 nm. However, the large pores became larger (increased from 18 386 to 29 846 nm and 61 509 nm) but the ratio decreased. These are because of the strong dissolution reaction of sandstone under the action of a strong acid, which leads to the increase of the pore diameter inside the sandstone. However, the reduction in the percentage of large pores is because some of the pores collapsed under the action of shrinkage and expansion during the freezing and thawing cycles. Figure 4b shows that, after 7 days of NaOH solution corrosion, although the overall change in the percentage of small pores in the sandstone was not significant, the small pore size diameters at the largest distribution in the sandstone samples increased slightly, those were, from 19 to 33 nm and from 33 to 70 nm, respectively. Importantly, the percentage of large pores was significantly reduced or even disappeared, as shown in 5 932 nm and 180 034 nm. These are because the sandstone and strong alkali underwent material transformation, and the new material generated filled the pores under the freeze–thaw cycling treatment and even led to an overall small shrinkage of the sandstone. Comprehensive Figs. 2, 3, 4 show that corrosive dissolution reactions occur in deionized water and acidic environments, resulting in the formation of large pores in the sandstone; however, chemical reactions of material transformation (sediment generation) occurred in alkaline and neutral salt environments, resulting in a reduced formation of sandstone pores.

Temperature and microstrain changes during the corrosion of sandstone by neutral solutions

To study the effects of a neutral salt solution and water on the corrosion characteristics of sandstone, sandstone samples were immersed in a Na2SO4 solution with a pH of 7 and deionized water. The temperature of the solutions ranged from − 10 to 60 °C. The temperature and microstrain of the sandstone were decoded using an FBG detection system (Fig. 5). The wavelength drifts of microstrain–temperature FBGs during the corrosion of sandstone was shown in Fig. S2.

Figure 5a shows that, when the corrosive solution temperature was decreased from 20 °C to − 10 °C, the sandstone temperature was lower than − 10 °C; that is, the temperature of sandstone in the Na2SO4 solution and deionized water decreased to − 11 °C and − 17 °C, respectively. Because the freezing point of the Na2SO4 solution is − 0.9 °C lower than that of deionized water [32], the amount of icing at the interface between the sandstone and the Na2SO4 solution was lower than that between the sandstone and deionized water. Therefore, the surface temperature of sandstone in the Na2SO4 solution was higher than that in deionized water. When the solution temperature increased from − 10 to 60 °C, especially when the solution temperature reached 60 °C, the temperature of the sandstone in the deionized water was close to 60 °C. This indicates that the deionized water and soluble material in the sandstone only underwent a physical solubility reaction (no heat-absorbing or exothermic reactions occurred). However, the temperature of sandstone in the Na2SO4 solution was higher than 60 °C, and the temperature difference with sandstone in deionized water reached 5 °C, which can be attributed to the following reasons: first, the temperature transfer coefficient of the Na2SO4 solution was lower than that of deionized water, which was more conducive to the transfer of heat from the outside to the sandstone. Secondly, an exothermic chemical reaction of the soluble matter in the sandstone samples with Na2SO4 occurred (Figs. 2d and 3b).

Figure 5b shows that, when the corrosive liquid temperature was lower than 0 °C, sandstone underwent corrosion in the Na2SO4 solution and the sensor outputted a negative microstrain higher than that in deionized water (microstrain data were derived from Fig. S2 and calculated using matrix 5). Because the chemical reaction rate between the Na2SO4 solution and soluble materials inside the sandstone was considerably higher than that between deionized water and soluble materials, the internal porosity of the sandstone increased, which was conducive to more liquid entering the sandstone. When the temperature is lower than − 0.9 °C, icing occurs, resulting in volume shrinkage of the sandstone; that is, when the corrosion fluid temperature is lower than − 0.9 °C, the proportion of sandstone volume shrinkage in the Na2SO4 solution was greater than that in deionized water. Therefore, the microstrain–temperature FBG sensor outputted a greater negative strain for sandstone in the Na2SO4 solution. As the temperature of the corrosive solution increased from − 0.9 to 0 °C, the ice formed on the surface of the sandstone began to dissolve in the Na2SO4 solution. However, it continued to freeze in deionized water, resulting in further contraction of the sandstone volume in deionized water. Thus, the negative strain of the microstrain–temperature FBG output from the sandstone surface in deionized water was further increased. However, when the temperature of the corrosive solution was higher than 0 °C, as the temperature of the corrosive solution further increased (extending the corrosion time), the sandstone underwent corrosion in the Na2SO4 solution and the sensor outputted a positive strain higher than that of deionized water. Because the reaction rate of the Na2SO4 solution with the soluble matter inside the sandstone was further increased at high temperatures, the porosity inside the sandstone increased and the proportion of swelling (fluff) was higher than that of the corrosion of sandstone by deionized water. When the corrosion time was 2364 min (39.4 h) and the corrosion fluid temperature was 60 °C, the microstrain difference between the FBG produced by the Na2SO4 solution and deionized water was 18.15 με.

Temperature and microstrain changes during the corrosion of sandstone by strongly acidic and alkaline solutions

To study the effects of strong acid/alkali solutions on the corrosion characteristics of sandstone, sandstone samples were immersed in deionized water, H2SO4 and NaOH solutions for the corrosion reaction. The corrosion solution temperature changed from − 10 to 60 °C. The changes in the sandstone temperature and microstrain are shown in Fig. 6 and Fig S3.

Correlation between the sandstone body temperature (a) and microstrain (b) and corrosion time during the corrosion of sandstone is subjected to deionized water and H2SO4 and NaOH solutions. The insert of (b) is the correlation between the sandstone body microstrain and pH of strongly acidic and alkaline solutions

Figure 6a shows that, when the temperature of the corrosion solution was decreased from 20 to − 10 °C, the temperature of the sandstone in the H2SO4 solution (pH = 3) was higher than that in the NaOH solution (pH = 13). The freezing point of the NaOH solution with pH = 13 (− 0.186 °C) was lower than that of the H2SO4 solution with pH = 3 (− 0.000558 °C), which led to more icing at the interface of the sandstone and NaOH solution than that of the sandstone and H2SO4 solution. Therefore, the temperature of the sandstone in the H2SO4 solution was higher than that in the NaOH solution. Subsequently, with the extension of the corrosion time of the sandstone solution (corrosion solution temperature increased from − 10 to 60 °C), when the solution temperature reached 60 °C, the temperature of sandstone in H2SO4 and NaOH solutions was higher than 60 °C. These results indicate that H2SO4 and NaOH reacted exothermically with sandstone. In addition, when the corrosion time was 141120 s (39.2 h) and the temperature of the corrosion solution was 60 °C, the temperature difference of the sandstone after corrosion with deionized water and H2SO4 and NaOH solutions reached 5.1 °C. This is because the heat released from the dissolution reaction of soluble matter in the sandstone samples with H2SO4 was higher than that released from the material transformation reaction with NaOH and the dissolution reaction with deionized water.

Figure 6b shows that, when the temperature of the corrosive solution was lower than 0 °C after the sandstone was corroded by the H2SO4 solution, the sensor outputted negative microstrain, which was higher than that in deionized water and the NaOH solution (microstrain data were derived from Fig. S3 and calculated using Matrix 5). Because the chemical reaction rate between the H2SO4 solution and the soluble matter inside the sandstone was considerably higher than that between deionized water and NaOH and the soluble matter inside the sandstone, the internal porosity of the sandstone increased (Figs. 2g and 4), which was conducive to more liquid entering the sandstone. When the temperature was below 0 °C, icing occurred, and the proportion of sandstone volume shrinkage in the H2SO4 solution was larger than that in deionized water and the NaOH solution. Therefore, the negative strain of sandstone in the H2SO4 solution on the FBG output was large. When the temperature of the corrosive solution was increased from 0 °C to 60 °C, the order of the strain strength of the FBG after the corrosion of sandstone with strongly acidic and alkaline corrosive solutions of different pH was as follows: pH (3) > pH (5) > pH (7) > pH (9) > pH (11) > pH (13). The microstrain difference between the sandstone corroded by the H2SO4 solution (pH = 3) and NaOH solution (pH = 13) reached 141.72 με. The reasons for this are as follows: first, in a strongly acidic environment, the lower the pH, the stronger the corrosion and the more intense the material dissolution reaction with sandstone (Fig. 4a), resulting in a more significant swelling effect of sandstone at high temperatures (Fig. 2g) and stronger microstrain on the FBG. Second, for deionized water, only a single soluble dissolution reaction occurred, and sandstone was subjected to a high-temperature expansion effect. Third, in a strongly alkaline environment, the greater the pH, the stronger the corrosion, the more intense the material conversion reaction with sandstone, the more mineral salts generated to fill the original soluble matter inside the sandstone (Fig. 4b), and the smaller the expansion of sandstone at high temperatures.

Temperature and microstrain changes during the corrosion of sandstone by acidic and alkaline salt solutions

To investigate the effects of acidic and alkaline salt solutions on the corrosion characteristics of sandstone, sandstone samples were immersed in deionized water and NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions. The temperature of the corrosion solutions ranged from -10 °C to 60 °C. The changes in the sandstone temperature and microstrain in the sandstone samples are shown in Fig. 7 and Fig. S4.

Correlation between the sandstone body temperature (a) and microstrain (b) and corrosion time during the corrosion of sandstone is subjected to deionized water and NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions. The insert of (b) is the correlation between the sandstone body microstrain and pH of acidic and alkaline salt solutions

Figure 7a shows that, when the corrosive solution temperature was reduced from 20 to − 10 °C, the surface temperature of sandstone in NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions did not decrease to − 10 °C. Because the freezing points of NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions are considerably lower than 0 °C, the reaction of sandstone with NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions releases heat. These results indicate that the temperature of the sandstone body was higher than that of the corrosive solutions. When the temperature of the corrosive liquid was 60 °C, the temperature of sandstone in NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions was higher than 60 °C. This indicates that the reactions of NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 with sandstone are exothermic. In addition, when the sandstone was subjected to corrosion by the Na2CO3 solution (pH = 11), it caused a higher amount of temperature change than that of the deionized water and NaHSO4 solution. When the corrosion time was 141,840 s (39.4 h) and the temperature of the corrosion solution was 60 °C, the temperature difference of the sandstone reached 9.0 °C. This is because the heat released from the reaction between the soluble matter and Na2CO3 in the sandstone sample was higher than that released from the reaction between NaHSO4, deionized water, and the sandstone. The higher the pH of the Na2CO3 solution, the stronger the alkalinity, the stronger the reaction with sandstone, and the more heat released.

Figure 7b shows that, when the temperature of the corrosive solution was < 0 °C, after the sandstone was corroded by the NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions, the sensor outputted a lower negative microstrain than that in deionized water (the data of micro-dependent variables are derived from Fig. S4 and calculated using matrix 5). This is because the freezing points of NaHSO4 and Na2CO3 solutions are lower than that of deionized water. The chemical reaction with sandstone at low temperatures resulted in the dissolution of some substances, thereby reducing the microstrain of the FBG produced by the sandstone. When the temperature of acid and alkali salt solutions were respectively increased from 0 °C to 60 °C, the strain strength of FBG after the corrosion of sandstone by acid and alkali salt corrosive solutions at different pH was in the following order: pH (3) > pH (5) > pH (7) > pH (9) > pH (11). The microstrain difference of the FBG after the corrosion of sandstone by the NaHSO4 solution (pH = 3) and Na2CO3 solution (pH = 11) reached 143.36 με. This is because the lower the pH of NaHSO4 solution is, the more corrosive it is and the more violent the dissolution reaction with sandstone. This resulted in a more significant dissolution effect of the sandstone (Fig. 2e), which produced a stronger microstrain on the FBG. The higher the pH of Na2CO3 solution is, the more corrosive it is, the more the reaction with sandstone results in the generation of CaCO3 and other substances (Fig. 3d), and the smaller the expansion of the sandstone.

In addition, by comparing Figs. 5a, 6a, 7a as well as Figs. 5b, 6b, 7b, we found that, when the sandstone was corroded by deionized water (pH = 7), Na2SO4 solution (pH = 7), NaHSO4 solution (pH = 3), Na2CO3 solution (pH = 11), H2SO4 solution (pH = 3), and NaOH solution (pH = 13), there was an overall exothermic reaction of the sandstone with the acid, alkali, and salt solutions. When the temperature of the corrosive solution was 60 °C, the temperature of the sandstone after corrosion under different corrosive solutions was in the following order from high to low: Na2SO4 solution (pH = 7), Na2CO3 solution (pH = 11), H2SO4 solution (pH = 3), NaHSO4 solution (pH = 3), NaOH solution (pH = 13), and deionized water. Microstrains in descending order were NaHSO4 solution (pH = 3), H2SO4 solution (pH = 3), Na2SO4 solution (pH = 7), deionized water, Na2CO3 solution (pH = 11), and NaOH solution (pH = 13; Table 1). One can observe that after the sandstone was corroded by strong acids, strong bases, and acidic salts, the temperature and surface stress of the sandstone changed most significantly after being corroded by NaHSO4. The reason is that H2SO4 only provides H+ which react with the minerals and sulfides in the sandstone, causing them to dissolve and thus corrode the stone artifacts. NaOH only provides OH− which react with the acidic components in the sandstone to form alkaline soluble substances. However, NaHSO4 decomposes in a humid environment to produce H+, Na+, and SO42−, giving it both salt and acid functionalities. The crystallization process of sulfates generates expansion stress and releases heat, thus the NaHSO4 solution with a pH of 3 had the strongest corrosion effect on the sandstone.

Conclusion

In this study, a binary parameter detection system for the temperature and microstrain of chemically etched sandstone in stone relics was constructed based on FBGs. A matrix model for the accurate measurement of the temperature and microstrain of sandstone was established. Sandstone samples were prepared to replace the stone artifacts. Different corrosion solutions were prepared using deionized water, H2SO4, NaOH, NaHSO4, Na2CO3, and Na2SO4. The corrosion characteristics of sandstone were experimentally investigated using corrosive solutions at different temperatures. The FBG sensor system constructed in this study was used to perform in situ real-time detection of the temperature and microstrain change information of the corrosion process of sandstone samples. The experimental results highlighted that, when the sandstone sample was corroded by acidic solutions (H2SO4 and NaHSO4), metal ions in sandstone and acid ions underwent exothermic dissolution chemical reactions, increasing the pore size, surface temperature, and microstrain of the sandstone. Furthermore, the degree of corrosion of sandstone was enhanced by a reduction in the pH of the corrosive solution. In an alkaline environment (NaOH and Na2CO3), the sandstone underwent a chemical exothermic reaction of material conversion, and a variety of generated alkaline-earth metal-aluminosilicate minerals filled the sandstone pores owing to freeze–thaw cycling treatment, resulting in a reduction in the internal pore size of the sandstone, an increase in the surface temperature, and a lower amount of change in the microstrain than those in the acidic environment. In a neutral salt solution (Na2SO4), sandstone underwent an exothermic chemical reaction with Na2SO4 for material conversion to generate new sediments, and the sandstone can maintain its original texture structure after the corrosion reaction. Deionized water on the sandstone-only soluble material physical dissolution reaction, temperature of the rock, and temperature of the corrosive solution were used to maintain the same microstrain produced by the thermal expansion and contraction effect of the rock. Among different corrosive solutions, NaHSO4 acidic salt solution with a pH of 3 was the most serious corrosive disease on the rock, and, when the temperature of the corrosive solution was 60 °C, the temperature and microstrain of the rock reached 63.9 °C and 253.6 με, respectively. The results of this research can be used for the water chemical corrosion mechanisms and the law of stone cultural relics to provide important support and promote the development of FBG sensor technology and engineering applications. Furthermore, this research can promote the preservation of stone cultural relics through novel scientific technologies.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Holdaway S, Douglass M. A twenty-first century archaeology of stone artifacts. J Archaeol Method Theory. 2012;19:101–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-011-9103-6.

Zhang J, Deng H, Taheri A, Ke B, Liu C, Yang X. Degradation of physical and mechanical properties of sandstone subjected to freeze-thaw cycles and chemical erosion. Cold Reg Sci Technol. 2018;155:37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2018.07.007.

Sacco Perasso C, Antonelli F, Calcinai B, Casoli E, Flavia Gravina M, Ricci S. The bioerosion of submerged archeological artifacts in the Mediterranean sea: an overview. Front Mar Sci. 2022;9:888731. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.888731.

Liu Z, Yang R, Wang W, Xu W, Zhang M. Multi-analytical approach to the mural painting from an ancient tomb of Ming Dynasty in Jiyuan, China: characterization of materials and techniques. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2022;279:121419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2022.121419.

Fermo P, Colella M, Malagodi M, Fiocco G, Albano M, Marchioron S, et al. Study of a surface coating present on a renaissance piety from the Museum of Ancient Art (Castello Sforzesco, Milan). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16244-9.

Volpi F, Vagnini M, Vivani R, Malagodi M, Fiocco G. Non-invasive identification of red and yellow oxide and sulfide pigments in wall-paintings with portable ER-FTIR spectroscopy. J Cult Herit. 2023;63:158–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.07.019.

Ye L, Fang M, Pan Q, Xu X, Wu X, Yuan S. Evaluation on weathering degree of limestone artifacts considering water absorption characteristics. J Eng Sci Technol Rev. 2022. https://doi.org/10.2510/jestr.155.01.

Özer F, Söylemez M, İnce İ. Detection of deteriorations in cultural structures created by carving into low-strength rocks by the non-destructive test (NDT) method. Front Archit Res. 2023;12(4):788–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2023.03.004.

Meier T, Auras M, Fehr M, Köhn D, Cristiano L, Sobott R, et al. Investigating surficial alterations of natural stone by ultrasonic surface measurements. Sens Past: From Artifact Hist Site. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50518-3_12.

AL‐Hameedawi MM, Thabit JM, AL‐Menshed FH, Conyers L. Integrating electrical resistivity tomography and ground-penetrating radar methods to map archaeological walls near northern Ishtar gate, ancient Babylon city, Iraq. Archaeol Prospect. 2022;29(2):293–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/arp.1852.

Cornett RL, Ernenwein EG. Object-based image analysis of ground-penetrating radar data for archaic hearths. Remote Sens. 2020;12(16):2539. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12162539.

Berezowski V, Mallett X, Ellis J, Moffat I. Using ground penetrating radar and resistivity methods to locate unmarked graves: a review. Remote Sens. 2021;13(15):2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13152880.

Liu Q, Liu Y, Yan F. Scratch detection of archival films: modeling and trajectory calculation. Herit Sci. 2024;12:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01119-8.

Ahmed SH. 3D laser scanner as a tool of documentation for the heritage gardens. Eng Res J. 2022;174:370–84. https://doi.org/10.2160/erj.2022.249607.

Hnin T, Noguchi K, Yagi T. Wind resistance evaluation of existing standing buddha statue using 3D laser scanning and CFD. J Struct Eng. 2023;149(8):04023095. https://doi.org/10.1061/JSENDH.STENG-11709.

Fehér K, Török Á. Detecting short-term weathering of stone monuments by 3D laser scanning: lithology, wall orientation, material loss. J Cult Herit. 2022;58:245–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2022.10.012.

Wu H, Xie Q, Liu Y, He X, Liu Y, Peng X, et al. In-situ monitoring of temperature and micro-strain during chemical corrosion of stone cultural relics by fiber Bragg gratings, Proc. SPIE 13066, International Conference on Optoelectronic Materials and Devices (ICOMD 2023), 130660S 2024. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3025048

Wang C, Chen M, Wang Y. Surface flaking mechanism of stone components of ancient building complex in Wudang Mountain, China. Constr Build Mater. 2023;399:132611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132611.

Zhang J, Yang X, Chen B, Wang X, Hu G, Tao N, et al. Study of the freeze-thaw weathering’s influence on thermal properties of stone artifacts. Atmosphere. 2023;14(4):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos14040666.

El-Mekawy A, Awad A, Shakour A, Saleh I, Ibrahium Y, Abdel-Latif N, et al. Effect of air pollution on the deterioration of El-manial palace and museum for greater conservation of Egyptian cultural heritage. Egypt J Chem. 2021;64(1):413–23. https://doi.org/10.2160/ejchem.2020.34881.2755.

Liao Q, Zhong N, Zhu X, Huang Y, Chen R. Enhancement of hydrogen production by optimization of biofilm growth in a photobioreactor. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2015;40(14):4741–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.02.040.

Chen M, Xin X, Liu H, Wu Y, Chang H. Monitoring biohydrogen production and metabolic heat in biofilms by fiber Bragg grating sensors. Anal Chem. 2019;91(12):7842–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b01559.

Ding G, Wang F, Gao X, Jiang S. Research on deformation reconstruction based on structural curvature of CFRP propeller with fiber Bragg grating sensor network. Photo Sens. 2022;12(4):220412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13320-022-0656-7.

Zhong N, Liao Q, Zhu X, Zhao M. Fiber Bragg grating with polyimide–silica hybrid membrane for accurately monitoring cell growth and temperature in a photobioreactor. Anal Chem. 2014;86(18):9278–85. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac502417a.

Ahmad H, Alias M, Ismail M, Ismail N, Zaini M, Lim K, et al. Strain sensor based on embedded fiber Bragg grating in thermoplastic polyurethane using the 3D printing technology for improved sensitivity. Photo Sens. 2022;12(3):220302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13320-021-0646-1.

Zhong N, Chen M, Wang Z, Xin X, Li B. Photochemical device for selective detection of phenol in aqueous solutions. Lab Chip. 2018;18(11):1621–32. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8LC00317C.

Tang Y, Chen X, Zhang J, Lv D, Xiong L, Dong X. Sensitivity-enhanced hot-wire anemometer by using cladding-etched fiber Bragg grating. Photonic Sens. 2023;13:230305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13320-023-0676-y.

Mei W, Liu Z, Wang C, Wu C, Liu Y, Liu P, et al. Operando monitoring of thermal runaway in commercial lithium-ion cells via advanced lab-on-fiber technologies. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):5251. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40995-3.

Xu C, Li L, Hu R, Wu H, Kong L, Zhong N, et al. In situ detection of spatial distribution information of temperature-pH-strain of sandstone cultural relics. Npj Mater Degrad. 2024;8(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00438-w.

Chen Y, Tang L, Sun Y, Cheng Z, Gong W. Physical–mechanical properties and microstructure degradation of acid–alkali contaminated granite residual soil. Geomechan Energy Environ. 2023;36:100501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gete.2023.100501.

Caponero M, D’Amato R, Polimadei A, Terranova G. Polymer-coated FBG humidity sensors for monitoring cultural heritage stone artworks. Measurement. 2018;125:325–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2018.04.072.

Hao G, Zhang Z, Guan C, Liu G, Hao Y, Fu T. Influence of soil salinization on active layer thickness of frozen soil. Atmosphere. 2023;14(2):296. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos14020296.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (52176178, 52304321), Meishan Science and Technology Plan Project (2022ZYZF13), Key R&D Projects of Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Plan (2023YFS0455), Chongqing Natural Science Foundation Innovation and Development Joint Fund (Municipal Education Commission) Project (CSTB2022NSCQ-LZX0059), Major Scientific and Technological Research Project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJZD-M202201101), Chongqing Talent Project (CSTC0222YCJH-bgzxm0241), and Innovation Research Group of Universities in Chongqing (CXQT21035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Z. and Y.L. designed the experiments. H.W. performed the experiments. Q.X., N.Z., X.H., and Y.Z. performed the analysis of sensor performance and stone sample characterization with the support of Y.H. and Y.L.; B.W., N.Z., Q.X., and Y.L. interpreted the data. H.W., B.W., Y.L., and N.Z. prepared the manuscript. N.Z., X.H., Y.L., Y.H., Y.Z., and B.W. revised the manuscript. Y.L., N.Z., and B.W. offered the Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Xie, Q., He, Y. et al. In-situ monitoring of changes in temperature and microstrain during the chemical corrosion of stone cultural relics. Herit Sci 12, 345 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01439-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01439-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

In situ continuous decoding of temperature humidity and micro strain during sandstone fracture hole restoration

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Discrete element simulation of damage mechanisms in stone cultural relics under dynamic impact

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Investigation on surface condition surveys and study on weathering mechanism of the stone wall at the Zhouqiao bridge ruins in Kaifeng

npj Heritage Science (2025)