Abstract

Historic districts play an important role in urban planning and protection. While previous research on soundscapes has focused on acoustic comfort or preferences in these districts, the aspect of authenticity has been somewhat overlooked. Therefore, this study proposes a methodology for constructing soundscapes that enhance the authenticity of such districts. Using the grounded theory approach, we identified four key components for enhancing authenticity via soundscapes: the aim of soundscape design, physical and cultural characteristics of soundscapes, the effects of soundscapes, and the influence of spatial characteristics on soundscapes. A theoretical framework was developed to illustrate the enhancement of authenticity in historic districts via soundscapes. To verify the applicability and advancement of the proposed framework, it was compared with methodologies and steps obtained from previous soundscape research in historic districts. This study underscores the significance of soundscape design in creating authenticity in historic districts, thereby contributing to the development of soundscape design in historic districts and offering sustainable solutions for the protection and renewal of urban cultural heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historic districts, a product of local character, culture, and tradition anchored in urban memory, can undergo cultural evolution and urban growth while also playing a significant role in fostering urban renewal and enhancing public spaces [1, 2]. Authenticity is a cultural or natural significance which is transcends national boundaries and is of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity. It may be understood as the ability of a property to convey its significance over time [3]. It is an important evaluation dimension of the historic districts, which was mentioned for the first time in the Venetian Charter. To protect authenticity, cultural heritage should not be rebuilt or moved [4]. Subsequently, due to the diversity of architectural heritage protection, the Nara document made a supplementary explanation, highlighting that the authenticity of heritage buildings should be flexibly protected in terms of the construction age, cultural and natural characteristics, and time changes [5, 6].

Existing research on the authenticity of historic districts primarily focuses on tangible value, namely the visual level, and neglects the protection of intangible value, such as auditory levels. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation defined eight features which contribute to the authenticity of a heritage site, including (1) form and design, (2) use and function, (3) location and setting, (4) traditions, techniques, and management system, (5) materials and substance, (6) language and other forms of intangible heritage, (7) spirit and feeling, and (8) other internal and external factors [3]. These features show that authenticity encompasses both the tangible and intangible values of heritage buildings. Authenticity facilitates emotional and spiritual explorations in the present, through a connection to the past, which means that people can be detached from everyday life [7, 8]. It is projected by imagination, expectations, preferences, beliefs, and strengths [9,10,11]. The content of soundscape creation is the same as authenticity, containing an understanding of people’s actions, feelings, and lifestyles in settings that resonate with their era. Therefore, soundscape design has the potential to safeguard authenticity. In the context of soundscape construction, this study investigates a novel technique to enhance the authenticity of historic districts.

UNESCO World emphasizes that the protection of historic districts is not limited to the care of material cultural heritage, but also extends to the preservation of intangible cultural heritage, such as the display of oral traditions, performances, social customs, and sounds [12,13,14]. The evolution of a soundscape carries significant value for social and cultural heritage, representing shifts in politics, economy, society, and urban spaces [15]. In historic districts, soundscapes serve as vital indicators of authenticity and cultural identity, offering insights into bygone eras and living quarters [16, 17]. However, conservation efforts have traditionally favoured visual aspects over auditory environments [18]. The relationship between historical values and soundscapes remains poorly understood [19].

In the nascent stages of soundscape research in historic districts, emphasis was placed on sound preservation as a significant component of cultural heritage protection [20, 21]. It is important to distinguish between desirable sounds that should be preserved or promoted, and those that ought to be eliminated; further, it is also important to be aware of the reasoning behind distinctions. A historic district can be recognized and given a sense of coherence by connecting its past, present, and future with soundscape data [22]. Notably, a range of sound characteristics has emerged in such areas owing to social and cultural changes at their core [23]. Historic districts should preserve auditory manifestations of social communication and cultural heritage, such as dialectal conversations and traditional vending calls [24]. Further, unique sound sources not only represent a historic district but also improve soundscape assessment [25]. Five categories of sound sources can be identified by examining the acoustic environments of old urban areas from three perspectives: sound, space, and spectrum. Among these, traditional sounds are recognized as sound signs with ‘local characteristics’, meriting designation as cultural heritage assets [26]. The spatiotemporal dynamics of soundscapes comprise sound sources, soundscape quality and satisfaction, as well as spatial landscape characteristics; together, these dynamics offer a framework for investigating the temporal and spatial dependences of soundscape [27]. Previous studies have examined the types of sound sources that can enrich historical environments from a soundscape protection standpoint, aiming to strengthen identity and refine soundscape perception evaluation. However, the connection between these efforts and the assessment of authenticity remains to be elucidated.

Another aspect of soundscape research in historic districts is the evaluation of sound environment perception in these districts. Previous researchers have assessed the acoustic environments of historic districts by focusing on factors such as acoustic comfort, satisfaction, and preference, determining which sounds should be preserved or minimised. Various sound sources affect different aspects of visitor experience and soundscape perception, with positive soundscape impressions significantly enhancing visitor satisfaction [28]. Studies on memorial sites have shown that the most common sounds come from birds, water, and visitors, with tourist noise detracting from the soundscape quality. In contrast, natural sounds, especially those of water, are beneficial for the acoustic environment [29]. Creating a favourable acoustic environment involves choosing sound sources thoughtfully and engaging multiple senses to deepen visitors’ comprehension of historical sites [30]. The complementarity of sounds is crucial for designing soundscapes [31], with urban historical areas showing a positive correlation between acoustic satisfaction and the subjective assessment of cultural identity. This assessment depends on a balanced integration of human and natural sounds [32]. Local landscape spatial patterns could have more effect on soundscape perception than that of on-site landscape composition [36]. The spatial perception of streets, including their closure and openness, can be modified by sound, highlighting the need for a systematic approach to improve the authenticity of soundscapes [33]. However, despite extensive research on enhancing comfort and satisfaction in historic districts, a definitive method for enhancing authenticity via soundscapes is yet to be established. The effectiveness of sound sources varies across historic districts, with overall soundscape satisfaction decreasing as space, building density, road grade, and urban density increase [34]. The architecture of historic districts, such as towering walls and covered entrances, can influence noise levels and the perception of space, indicating that the selection and placement of sounds depend on the type of space [35]. Given the complexity and diversity of spaces in historic districts, the effect of the relationship between sound and space on the historical significance of a district remains to be determined.

Research on the soundscape of historical districts can be divided into quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative research methods, such as scale tools, electroencephalogram (EEG), and emotion recognition software, are more suitable to quantify and reflect individuals’ emotional identification with soundscapes in real time, which are used for spatial classification or to examine general trends in large populations [36,37,38,39]. Quantitative data, such as the grounded theory, qualitative content analysis, and social network analysis, are more appropriate for explorative research aimed at theory generation [40]. and are more effective for small groups or an in-depth analysis of certain sites. Grounded theory is a research method that emphasises the generalisation of theories from actual observed data and the construction of theories through systematic data collection and analysis [41]. It adopts inductive and bottom-up reasoning to build models or theories by collecting and analysing relevant data. Thus, it aligns with the holistic approach of soundscapes in its emphasis on understanding the human experience in context, which helps to understand the actual experience of the soundscape in the actual district environment [42]. Therefore, the research method of grounded theory was chosen for this study.

While soundscape design is significant for the revitalisation and preservation of historic districts, its precise role in augmenting authenticity remains unclear. Therefore, this study investigated a novel technique for enhancing authenticity in historic districts via soundscape construction. This research aimed to investigate the specifics of soundscape construction, clarify its aims, provide methods for sound selection and control, explore the effects of soundscapes, and discuss the influence of spatial characteristics on the soundscape. By employing grounded theory as an experimental technique, this research addresses the gaps in existing literature, contributing to the conservation and revitalisation of historic districts by redefining soundscape research parameters.

Methods

Experimental design

Five historic districts were mentioned in the interview experiment, namely Beijing Dashilan Historic District, Shanghai Bund Historic District, Harbin Laodaowai Historic District, Wuhan Jianghan Road Historic District, and Guangzhou Shamian Historic District. The district profiles are provided in Appendix 2. The districts involved have simultaneously commercial, residential and historical cultural functions. Participant selection criteria was established before the experiment. We targeted participants with a comprehensive professional background, including architecture, acoustics, and urban planning, to ensure professionalism of the experimental results. Simultaneously, to ensure a balance of interests, managers, commercial operators, residents, and tourists within the historic district were included as participants. The participants also had different educational backgrounds and age ranges [43, 44]. The exclusion criteria also followed a set of principles; Since the main content of the study was related to the construction of soundscapes in historic districts, the participants had to have strong perception abilities. One person was therefore excluded due to a hearing impairment. In addition, the participants’ level of comprehension was also important, and their logical thinking and expression abilities may determine the scientific results of the experiment. Consequently, we also excluded one participant who expressed themselves in a confusing way. The specific inclusion and exclusion processes are described in Fig. 2 and in Sect. Experimental process (Step 1), During the experiment, semi-structured narrative interviews were conducted to gather data [45]. Participant information was collected and coded for analysis from December 2022 to January 2023.

To avoid the influence of fatigue on the experimental results, the interviews were conducted indoors and participants were seated. It was stated before the experiment that if the respondents felt tired, they could stop at any time, however, this did not occur. Given that interviews lasting more than one hour are more likely to cause fatigue, we set the interviews to last between 40 and 60 min [46].

As Table 1 shows, the study included 25 respondents of varying ages (from 19 to 60 years). The participants were divided into three age groups: young adults aged 18–29, middle-aged adults aged 30–59, and older adults over 60. The average age of the participants was 30.3 years. The gender distribution was balanced at 12 males and 13 females, and participants were evenly distributed across educational levels. As suggested above, normal perceptual abilities (vision and hearing) were required for the experiment. Meanwhile, since the study focused on urban historic districts, the participants were all urban residents, while rural residents were excluded.

Interviews were deemed complete when participants had no additional information to provide. Theoretical saturation was reached when information from group discussions became repetitive, with no new categories or insights emerging from further sampling. This point was reached with 10 men and 9 women. Subsequently, 6 additional interviews (3 men and 3 women) were conducted to test theoretical saturation, marking the end of the interview phase [47].

The data collection methods included audio recordings and instant transcriptions, with preparatory analysis involving speech-to-text conversion, anonymisation, coding, and summarisation.

Experimental process

The interview questions were set by the research team for the research objectives, therefore, they were not replicated from previous studies. In terms of the logical structure of the interview questions, we referred to previous research and primarily used guiding and progressive questions [41]. The experimental procedure encompassed six steps, detailed in Fig. 1.

Step 1 involved the set of criteria for selecting participants. The integration phase of the participants focused on the sociological characteristics and background. Participants were excluded based on whether their perceptual abilities were normal, their participation attitudes were positive, their understandings were correct, and their logical thinking and expression skills were good.

Step 2 included the interview process. The formulation of discussion questions was aligned with the research purpose. The questions focused on three main types of problems. The first set comprised introductory problems, designed to clarify the respondent’s initial perception of authenticity, such as, ‘Imagine a scenario where you are about to travel to a historic district. What would you like it to feel like? How would you rate the trip?’ The second set included exploratory questions aimed at understanding the current state of authenticity, such as ‘What sounds enhance or diminish the authenticity?’ and ‘What things or actions in the district made your experience more historical? Does this matter have a big impact?’ The third set of questions delved into continuity, exploring the creation of authenticity via soundscape design, with follow-up prompts such as ‘Please be more specific’, ‘Can you give examples?’ to aid the participants in recalling detailed experiences.

Step 3 involved the data analysis. In the open coding stage, the recording was carefully converted into text, the full text was translated and read, and the key words were initially screened. In the axial coding stage, the same content was obtained, the data was simplified, and the code was combined. In the selection coding stage, the core category was selected and the theory was formed, compared, and verified.

Step 4 was designed to explore the logical relationships between the codes to make connections. Based on the coding results obtained in the process of data analysis, the main content of soundscape construction was proposed, the rules were found and summarized, the connection between the contents was established, the theory was finally formed, and the theoretical framework for enhancing authenticity through soundscape design was developed.

All interviews, conducted with participant consent, were recorded and transcribed, yielding transcripts totalling approximately 26,000 words. The audio recording and audio transcription software used in the interview were all qualified for information security and were encrypted during the whole process. Interview data were used only for this study.

The whole interview process was conducted in Chinese, the interview is outlined in Appendix 1. Considering the extensibility of the research, the entire process was translated into English, including the full interview record, coding process, team discussion process, and theory formation. To ensure the validity and accuracy of the translation, bilingual verification and participant feedback were carried out [48, 49]. The specific operation was as follows: (1) After the translation was completed, it was first verified by bilingual experts to ensure that the translated content was true to the original text and reduce misunderstandings or omissions in the translation; and (2) The translated content was then presented to the participant at the time of data processing to ensure that their views and responses were not misunderstood or misinterpreted during the translation process.

Data analysis

Triangulation, a staple in qualitative research, enhances study credibility [50]. From the perspective of researcher triangulation, two researchers with backgrounds in architecture and soundscape studies, both proficient in qualitative research methods yet from slightly different social backgrounds, undertook the data analysis. A panel of experts subsequently reviewed their results to ensure that the coding was impartial and accurate. Additionally, saturation testing and a gender group difference analysis were carried out to ensure the objectivity and relevance of the research results.

The participant speeches yielded a wealth of qualitative data for this study. Key expressions from the participants were identified and marked as codes in an iterative coding process. These initial codes were then aggregated into second-level codes, which were subsequently grouped into categories that aligned with the final research topics. The analysis proceeded through the following steps:

-

(1)

Open Coding: The process began with a thorough reading of the translated text materials from the recordings, with special attention placed on the content that discussed key issues. This comprehensive review of the raw material facilitated an understanding of the primary content, leading to the analysis and initial coding of the text.

-

(2)

Axial Coding: Following the initial coding, the data were further summarised and abstracted according to content similarity. This step involved consolidating several related initial codes to secondary codes, simplifying the data into more manageable segments with similar or related meanings.

-

(3)

Selective Coding: The next step was to identify links between secondary codes and to group related generalisations of these codes into various thematic categories based on their content.

To ensure objectivity and consistency of the coding, the coding manual standardization method and coder discussion method were adopted [41]. The process was as follows: (1) Prior to the data processing phase, a detailed coding manual was developed to clarify the definition, classification criteria, and operating procedures of coding. All coders were required to code strictly in accordance with the coding manual; (2) regular coder discussions were organised to communicate differences and problems in the process, to modify and improve the coding scheme. A panel of experts subsequently reviewed their results to ensure that the coding was impartial and accurate.

Using these coding steps, the interview texts were meticulously summarised, organised, and analysed, resulting in 624 basic labels (a1), 385 conceptual labels (aa1), 52 classification labels (A1), and four main classification labels (AA1). The results of these coding analyses are shown in Table 2.

Results

Following the grounded theory experiment, a statistical analysis based on the frequency of content mentions was conducted. Figure 2 reveals four primary categories: ‘The aim of soundscape design’ (AA1), ‘Physical and cultural characteristics of the soundscape’ (AA2), ‘The effects of the soundscape’ (AA3), and ‘The influence of spatial characteristics on the soundscape’ (AA4). ‘The aim of soundscape design’ (AA1) focuses on establishing principles and guidelines for future design efforts, and ‘Physical and cultural characteristics of the soundscape’ (AA2) primarily addresses sounds that must be protected or eliminated. ‘The effects of the soundscape’ (AA3) balanced discussions on emotional changes and methods for recreating historical soundscapes. In exploring the connection between sound and space, or the construction of atmosphere in ‘The influence of spatial characteristics on the soundscape’ (AA4), participants noted the effect of scale, enclosure, openness, and spatial function on sound settings, which will be further analysed in this section.

The aim of soundscape design

The aim of soundscape design comprehensively encompasses three pivotal aspects: (1) defining soundscape content, (2) enhancing the transformation of time, and (3) increasing interaction with sound. This section presents a detailed analysis of these aspects.

Defining soundscape content

As the three dimensions of soundscape content, the original sound, soundscape memory, and cultural characteristics are very important. A frequency analysis of the corpus, as shown in Fig. 3, indicates that terms describing original sound, such as 'vicissitudinous, heavy, primitive, tedious, and dull', appear most frequently. The valuation of soundscape memory involves recall, association, and reflection on the district, adding depth to aesthetic evaluation and is related to signals. This includes acquiring new knowledge, generating memory points, and feeling regional characteristics (a472, a459, a194). Descriptions such as 'old, melancholy, slow, thick, and cold' were noted. The evaluation of cultural symbols is also important where descriptive terms included 'prosperous, elegant, peaceful, mysterious, and inclusive'. The intentional perception of sounds plays a significant role. For example, interviewee 17 highlighted ‘Hawking is very important and can greatly reflect regional characteristics. People’s understanding of history is different, and it is easy to transport everyone to the period through hawking’ (a639). In particular, sounds related to business activities facilitate meaningful connections.

Enhancing the transformation of time in soundscape

Authenticity is the awareness of temporal transformation. To achieve this, the soundscape must first accurately represent the age of the buildings within the historic district. ‘The unique characteristics of the historic district can be reflected in the life scene, and the life of different places will no longer make people feel the same, and tourists will also understand the history and characteristics from these.’ Moreover, the soundscape should mark important temporal milestones in the district’s development. This is reflected by the ideas that ‘History and time are very related, and the sound will make people feel the passage of time’ and that ‘The sound is constantly changing, and the district is constantly evolving.’ By carefully curating sound content, tourists can experience a harmonious blend of temporal awareness and auditory perception (a17, a240, a329).

Increasing interaction with sound

The authenticity evoked by the soundscape extends beyond mere perception; it also encompasses participation. The daily life and customs of local inhabitants are important in conveying the cultural characteristics, and safeguarding these ambient sounds helps visitors connect with the regional characteristics. Soundscape design should not only present relevant content but also enhance multi-sensory experiences via interactive devices, engaging senses such as sight, hearing, touch, and smell. By facilitating personal engagement in activities that embody local traditions via sound interaction, visitors can immerse themselves fully in the experience. The essence of visiting a historic district lies in the visitor’s experience, defined by their interest in the activities and the emotional responses they evoke [51]. Accordingly, an interviewee stated that they wanted to ‘suddenly travel through time and back to that moment.’ Tourists seek a direct experience of authenticity via their travel experiences focused on culture and heritage (a81, a216, a572).

Physical and cultural characteristics of the soundscape

Sound physical speciality

Starting with sound characteristics, we analysed the frequency heat of descriptions related to interviews. The interview involves the contents of ‘the loudness of sound, the speed of sound, the sharpness of sound, the articulation of sound’, which correspond to the scope of soundscape research ‘strength, tempo, pitch, and fidelity’. Figure 4 illustrates the frequency and number of occurrences in each content categories. For example, sounds with low strength tend to evoke authenticity: a strong tone may disrupt the overall atmosphere and persist longer than a softer tone. Soft tones are preferable for keynote sounds, while a fraction of soundmark can accommodate stronger tones. Slower sounds contribute to a historical atmosphere, whereas modern music, with its rapid tempo, can interrupt authenticity. Along these lines, one interviewee stated, ‘The sounds associated with the elderly are slow, so the life of an elderly person feels historical to me’ (a165). In historic districts, the soundscape is typically characterised by low-pitched sounds: ‘Some of the low-pitched sounds are more historical’ (a457). The low level of ambient noise enables discrete sounds to be distinctly heard, creating a high-fidelity (hi-fi) soundscape, with minimal sound overlap and a clear spatial relationship between the foreground and background sounds. A quiet background in a hi-fi soundscape enables sounds to be heard from a distance, contrasting with a low-fidelity (lo-fi) soundscape, where sound perspective is reduced. As cities develop, the signal-to-noise ratio decreases, resulting in more lo-fi soundscapes. Historic districts should prioritise high-fidelity sounds with low overlap, enabling clear identification of type, content, and source.

Sound and cultural connotations

Figure 5 suggests that the types of sounds that meet the targets of soundscape authenticity vary: human sounds and some social sounds can approach original sound, mechanical sounds and some social sounds can trigger soundscape memory, and some indicator sounds can reinforce cultural symbols. Morphological principles guide the clustering of morphologically or functionally similar sounds in a temporal or geographical sequence to delineate their changes or evolutionary trends as clearly as possible. Changes in materials from wood to plastic or in transportation from walking to cars, where sound events acquire symbolic significance, can serve as acoustic symbols and signals. In designing the soundscape of a historical district, reflecting on material and tool changes can highlight cultural shifts.

Changes in materials are predominantly reflected by mechanical sounds, whereas changes in tools are mostly reflected by human and social sounds (a126, a274, a364). Certain human and social sounds are apt for background sounds, whereas mechanical sounds tend to serve as signal sounds. Indicator sounds, acting as soundmark, are particularly effective in highlighting the historical characteristics (a33, a371). The processes of production and processing within the district symbolise the evolution of tools over time, transitioning from manual to mechanical methods. ‘Sounds should contribute to memory points and information points, showing the process of making and processing food and objects following the era.’ ‘The display of sound is very important in the production process. The feeling and information of a finished product are limited, and the sound will provide more information points.’ The medium through which sounds are communicated also plays a significant role in conveying authenticity. Along these lines, ‘The sound of selling is very important, in addition to the positioning of the object itself, the tone, mode, content, language family. The medium of communication is particularly important, and simple and direct loudspeakers are not suitable’ (a116, a531).

The effects of the soundscape

Using soundscapes to increase emotional change

In the development of a soundscape, the focus should also be on the richness and completeness of emotional changes. Visitors to historic districts seek to undergo personal emotional shifts during their exploration, which can strengthen their historical memory and solidify their connection to the district. Interviewee 17 stated, ‘The complete process of emotional change, such as depression-happiness-contemplation, makes me feel the historical atmosphere.’ While visual elements are often deemed dominant in generating historical sensations, the soundscape holds a ‘veto’. Incongruent sounds, such as those from machinery or fast-paced music, can disrupt the emotional experience. The creation of an immersive environment requires a holistic approach, engaging sight, hearing, smell, and touch in harmony. For example, ‘In the process of performance, visual aspects (dressing, performance mode, location fit), auditory aspects (music content, genre, tune, style), olfactory aspects, some old and worn materials give off the smell, damp, rotten feeling’ (a186, a340, a371, a428).

Using soundscapes to recreate historical scenes

In the design of the overall tour route, the introduction of specific situational points through changes in sound can effectively recreate the historical soundscape, encompassing daily life scenes of indigenous people, folk activities, and performances. These points serve a functional role, drawing visitors and guiding them through different zones of the district. The connection between visual features and sound environments is key to comprehensively understanding historic districts [52]. Interviewee 23 suggested, ‘Adding some guiding sounds, for example, sounds can be used as the guidance of functional differences (eating, playing and watching) or the guidance of cultural display, so that the whole tour process will be smoother and more coherent’ (a171). The concept of place in this context is not static but dynamically formed by various factors, including the inhabitants, meaningful architecture, participatory perception, and shared spaces. This dynamic interaction between people and place enhances the historical atmosphere, deepening visitors’ memories and impressions of the district and enriching authenticity (a423, a566, a602). For example, the traditional lifestyles and daily routines of indigenous people can evoke feelings of nostalgia and desolation, further enhancing the authenticity. In terms of soundscape design, distant settings can evoke a sense of the past more effectively: ‘The sound of the performance starts to have positive feedback from a distance’ and ‘The activities will create a magnetic field, and these magnetic fields will enhance the historical character’ (a126, a375, a604).

The influence of spatial characteristics on the soundscape

Influence of spatial morphological features on soundscape design

The spatial characteristics of the environment—such as the enclosure or openness, shape and size of spaces, materials and shapes of surfaces, topography, arrangement of buildings, and distribution of landscape elements such as flora—play a crucial role in sound propagation. Local landscape spatial patterns could be more influential on soundscape perception than on-site landscape composition [53]. These factors influence sound absorption, reflection, diffraction, or transmission, thereby affecting the perception of the authenticity of soundscape. Discussions also highlighted that ‘The sound setting is related to the scale of the street; on a large-scale street, the sound can be more complex; smaller streets should be quieter.’ Furthermore, the aspect ratio of street spaces affects the choice and application of sound sources; ‘A narrow alley has a strong sense of pressure on both sides of the building. Sound reflects this spatial feeling and gives me authenticity.’ Similarly, the perception of authenticity varies significantly between open and private spaces, underscoring the importance of thoughtful sound type selection based on the spatial characteristics of street environments (a63, a79, a142).

During an interview experiment, we discovered that the natural (gender) attributes of respondents significantly affect their experience of soundscape [54]. Figure 6 shows the respondents’ perception of the relationship between space and sound settings, differentiated by gender. As shown in Fig. 6a, respondents generally agreed that spatial morphological features, such as scale, enclosure, and openness, influence sound settings, with building scale being the most discussed aspect. Gender differences revealed that men were more focused on the relationship between scale and sound, whereas women were more concerned about how openness relates to sound.

Influence of spatial functional features on soundscape design

In the design of soundscapes, sound must complement the atmosphere of the material space. Sound selection and setting should align with the current functional zoning of the district, accentuating the differences between commercial, residential, and cultural areas through the sound environment. For example, ‘The commercial street is prosperous, showing the historical atmosphere; the residential branch is quiet and reflects people’s daily life’ (a148, a379, a527).

As shown in Fig. 6b, respondents discussed how spatial functional features, such as residential, historical, and commercial aspects, affect soundscape design. Gender differences showed that men were more interested in commercial functions, whereas women paid greater attention to residential and historical sound environments. The spatial arrangement of sound sources plays a crucial role in auditory perception and the overall quality of the soundscape. People are not merely occupants of the space but also its interpreters and creators, engaging with and contributing to the soundscape through their presence and actions.

Discussion

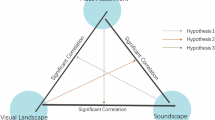

Historic district soundscape design theoretical construction

As shown in Fig. 7, in the process of theoretical construction of the grounded theory, it was established that soundscape design methods are successively carried out under the guidance of ‘The aim of soundscape design’ (AA1). ‘Physical and cultural characteristics of the soundscape’ (AA2), ‘The effects of the soundscape’ (AA3), and ‘The influence of spatial characteristics on the soundscape’ (AA4) are presented in sequence.

‘The aim of soundscape design’ outlined the fundamental guidelines and principles for creating soundscapes that emphasize and highlight the essence of cultural heritage. This includes defining soundscape content, enhancing time transitions in the soundscape, and increasing interaction with sound. It is the principle for subsequent steps.

The process of sound selection and control primarily includes defining the characteristic sound spectrum of the district, aligning sound types and meanings, protecting sounds that reflect historical and cultural characteristics, removing incompatible sounds, and establishing specific selection and control standards. These are summarized as ‘Physical and cultural characteristics of the soundscape’.

Emotional changes and recreating historical scenes include emphasising the integrity and richness of emotional changes, designing special situations to enhance historical memory through multi-sensory cooperation, and planning the emotional journey throughout the tour to guide visitors’ emotional experiences in the historic district. These are integrated into ‘The effects of the soundscape’.

‘The influence of spatial characteristics on the soundscape’ is essentially the impact of different spatial features and spatial functional features on sound settings, so as to create a unique historical atmosphere for different spaces.

Historic district soundscape design framework

In previous studies, historic district preservation in previous studies encompasses a four-step process, beginning with a resource assessment that entails a thorough evaluation of historical and cultural resources and assessing the heritage value within the planning framework to determine which historical buildings and cultural resources require protection [55]. This lays the groundwork with essential cultural heritage information [56]. This is followed by a feasibility assessment that examines social, economic, and policy dimensions to ensure the viability of the project across various levels [57], and incorporates a comprehensive project review [58]. The third step involves judging spatial characteristics and assessing factors, such as scale, shape, enclosure, and openness, to inform subsequent protection and renewal efforts [59]. The final step, monitoring and adjustment, involves regular evaluation and modification of the project to respond to environmental changes within the historic district and wider area [60].

Building on the in-depth conclusions drawn from the third part of the experiment, as shown in Fig. 8, previous protection methods for historic districts have been augmented with four additional steps related to soundscape design. Since the ‘The aim of soundscape design’ needs to be assessed based on district resources, it is taken as Step 2 and then a feasibility assessment is done as Step 3. Step 4 ‘Physical and cultural characteristics of the soundscape’ follows. Step 6 ‘The effects of the soundscape’ and Step 7 ‘The influence of spatial characteristics on the soundscape’ need to be combined with the spatial characteristics of district. Therefore, Step 5 completes the judgment of spatial features. Finally, Step 8 ‘Monitoring and adjustment’ is carried out. This results in a methodological framework aimed at effectively constructing authenticity within the soundscape of historic districts.

Finally, it is important to verify the validity of the framework proposed in this study. A control group experiment that does not use the study results can be designed to verify the rationality of the aim of soundscape construction in Step 2 through virtual reality simulation [61]. The immersive soundscape perception evaluation experiment based on psychology and physiology was adopted to verify the effectiveness of sound selection and control in Step 4 [62]. The rationality of the Step 6 was verified by an interactive soundscape design method [63]. The coordination of sound and different spaces was verified by acoustic environment simulation, and the effectiveness of the Step 7 was judged [64]. This comprehensive framework was devised to guide the systematic planning of soundscapes in historic districts, ensuring the construction of soundscapes with a deep authenticity that meets contemporary societal and cultural needs.

Comparison with other soundscape research in historic districts

As shown in Table 3, the methodological framework for designing soundscapes within historical districts varies, reflecting differing research focuses and design goals. Common construction steps include summarising the development of the historic district, cataloguing changes in sound sources, optimising the selection of sound sources, identifying space types, adjusting sound settings, and coordinating audio-visual effects.

Previous research primarily targeted the deepening of urban memory [29, 65], alignment of historical spaces with sound [26, 66], and preserving audio-visual unity as objectives for soundscape construction in historic districts [30]. In contrast, the method presented in this research places a distinct emphasis on enhancing historical awareness. Traditional soundscape design in historic districts often prioritises sound markers, expectations of the soundscape, sound preferences, and the comfort of acoustic environment perception [28]. For example, background sounds and distinct sound sources contribute to sensations of enjoyment and eventfulness [67]. Natural sounds play an important role in shaping the soundscape perception and visual landscapes [68]. This study posits that each sound within a historic district serves a specific function, conveying original sound, historical memory, and cultural characteristics which are important for fostering authenticity in these areas.

The relationship between sound and space is important for creating authenticity [52, 69]. While continuous emotion measurement methods have been used to assess the influence of sound sources on emotional responses within sound sequences [70], enhancing authenticity transcends merely positive emotional experiences. It involves provoking a spectrum of emotional responses through strategic sound settings in historic districts. Indicators such as the proportionality and intricacy of decorations, cultural atmosphere, and appeal of traditional residences and public buildings affect variations in visual behaviour towards architectural heritage [71]. The results of this study show that the scale, enclosure, and openness of a district have significant effects on the authenticity of its soundscape. Regarding the selection of practical methods, a variety of approaches, including field research, software analysis, questionnaire surveys, narrative interviews [40], the creation of soundscape maps [72], interactive soundscape creation [28], and the formulation of soundscape prediction models have been identified as effective means to explore how space influences sound settings [73].

By following the method proposed in this study, historic districts can craft auditory ‘places’ that stir special memories, fostering a distinct atmosphere and emotional resonance associated with historical spaces.

Limitations

Despite the contributions of this study to enhancing authenticity in historic districts through soundscape design, its limitations must be acknowledged. First, the concept of authenticity is subjectively influenced by cultural backgrounds. This study focused only on Chinese participants, overlooking the perception of international tourists towards the authenticity of Chinese historic districts, thus limiting the applicability of its findings across cultures. Second, while this study examines the impact of spatial factors on sound settings through the lenses of gender and professional background in architecture, it does not extend its analysis to other demographic characteristics such as age and educational level This omission limits a more comprehensive understanding of demographic influences. Finally, the method of creating authenticity within historic districts from a soundscape design perspective could benefit from a broader consideration of factors such as economic development and cultural diversity. Addressing the limitations in the future could provide a more comprehensive and universally applicable framework for soundscape design in historic districts.

Conclusions

To deepen the experience in historic districts, we established a theoretical framework for soundscape design. The research defined the main contents and elements of soundscape design and outlined a series of detailed steps and considerations for constructing soundscapes. The study results can be summarised as follows:

‘The aim of soundscape design’ comprehensively encompasses three pivotal aspects: (1) defining soundscape content, (2) enhancing the transformation of time, and (3) increasing interaction with sound. Among them, as the three dimensions of soundscape content, the original sound, soundscape memory, and cultural characteristics are very important. In the future research work, soundscape perception will be introduced to enrich the dimension of authenticity of historical districts and enhance the scientific and integrity of heritage protection.

‘Physical and cultural characteristics of the soundscape’ emerged as pivotal stages in the design process. This process involved defining criteria for selecting and implementing sounds based on their characteristics and meanings. The process determined which sounds enhance the authenticity, identifying sounds worth preserving and those that should be removed or minimised. At the level of soundscape intelligence, the sound source selection can be provided in the future, as the basis of intelligent soundscape design.

‘The effects of the soundscape’ includes using soundscapes to enhance emotion changes and recreating historical scenes. It highlights the significance of emotional dynamics in intensifying the authenticity. The construction of specific scenarios was shown to deepen the perception and memory of the historical atmosphere of the district. At the level of multi-sensory interaction, it can be used as the design focus of multi-sensory interaction platform in the future.

The study also investigated the influence of the spatial, morphological, and functional characteristics of historic districts on sound settings. Additionally, it examined the effect of various demographic backgrounds on preferences towards historical soundscapes, resulting in the construction of a historical atmosphere in the soundscape. At the level of soundscape perception evaluation, a demand-driven soundscape monitoring and evaluation platform can be established in the future.

Augmenting and refining traditional visual preservation methods, the study developed a comprehensive framework for soundscape design. To validate its innovation and applicability, this new framework was compared with existing approaches to soundscape design in historic districts.

The results provide a comprehensive theoretical foundation for the advanced exploration of authenticity within soundscapes in historic districts, presenting a new perspective for soundscape research. By establishing a detailed theoretical framework, this study addresses a previously unexplored aspect of soundscape design, providing a powerful guide for future conservation and design efforts in historic districts.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Mekonnen H, Bires Z, Berhanu K. Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Herit Sci. 2022;10(1):177. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00802-6.

Zhang Y, Zhang Q. A model approach for post evaluation of adaptive reuse of architectural heritage: a case study of Beijing central axis historical buildings. Herit Sci. 2023;11(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00902-x.

Committee WH. Operational guidelines for the implementation of the World heritage Convention. 2002. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000369013

Charter V. International charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites. Venice, Italy. 1964. https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/157-the-venice-charter

Charter I. The Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention. 1994. https://www.icomos.org/en/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/386-the-nara-document-on-authenticity-1994

Del MSTT, Sedghpour BS, Tabrizi SK. The semantic conservation of architectural heritage: the missing values. Herit Sci. 2020;8(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00416-w.

Gao BW, Zhu C, Song H, Dempsey IMB. Interpreting the perceptions of authenticity in virtual reality tourism through postmodernist approach. Inf Technol Tour. 2022;24(1):31–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-022-00221-0.

Zhang T, Yin P. Testing the structural relationships of tourism authenticities. J Destin Mark Manage. 2020;18: 100485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100485.

Steiner CJ, Reisinger Y. Understanding existential authenticity. Ann Tourism Res. 2006;33(2):299–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.08.002.

Wu D, Shen C, Wang E, Hou Y, Yang J. Impact of the perceived authenticity of heritage sites on subjective well-being: a study of the mediating role of place attachment and satisfaction. Sustainability. 2019;11(21):6148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216148.

Zhang S, Chi L, Zhang T, Ju H. Spatial pattern and influencing factors of land border cultural heritage in China. Herit Sci. 2023;11(1):187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01037-9.

Zhong B, Xie H, Gao T, Qiu L, Li H, Zhang Z. The effects of spatial characteristics and visual and smell environments on the soundscape of waterfront space in mountainous cities. Forests. 2023;14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14010010.

Ba M, Li Z, Kang J. The multisensory environmental evaluations of sound and odour in urban public open spaces. Environ Plan B-Urban. 2023;50(7):1759–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083221141438.

Zuo L, Zhang J, Zhang RJ, Zhang Y, Hu M, Zhuang M, et al. The transition of soundscapes in tourist destinations from the perspective of residents’ perceptions: a case study of the Lugu Lake Scenic Spot, Southwestern China. Sustainability. 2020;12(3):1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031073.

Bozdag HT, Benabbou R, Arslan TV. A framework proposal for resilience assessment in traditional commercial centres: case of the historical bazaar of bursa as a resilient world heritage site. Herit Sci. 2022;10(1):154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00792-5.

Kang J, Aletta F, Gjestland TT, Brown LA, Botteldooren D, Schulte-Fortkamp B, et al. Ten questions on the soundscapes of the built environment. Build Environ. 2016;108:284–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.08.011.

Gomez Escobar V, Barrigon Morillas JM, Rey Gozalo G, Vaquero JM, Mendez Sierra JA, Vilchez-Gomez R, et al. Acoustical environment of the medieval centre of Caceres (Spain). Appl Acoust. 2012;73(6–7):673–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2012.01.006.

Montazerolhodjah M, Sharifnejad M, Montazerolhodjah M. Soundscape preferences of tourists in historical urban open spaces. Int J Tour Cities. 2019;5(3):465–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijtc-08-2018-0065.

Dumyahn SL, Pijanowski BC. Soundscape conservation. Landscape Ecol. 2011;26(9):1327–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-011-9635-x.

Zhu X, Oberman T, Aletta F. Defining acoustical heritage: a qualitative approach based on expert interviews. Appl Acoust. 2024;216: 109754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109754.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett B. Intangible heritage as metacultural production. Museum Int. 2014;66(1–4):163–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/muse.12070.

Tokgöz ÖG, Bilen AÖ, Kandemir Ö. Searching the industrial soundscape of the early republican era of an anatolian city: Eskisehir. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics, Aachen, Germany 2019. p. 9–13.

Calvachi-Arciniegas S, Enriquez-Hidalgo J, Montenegro-Huertas S. Sound identity as a vestige of the “Place and Non-Place” in the Historic Center of Pasto. Rev Arquit. 2023;25(1):67–82. https://doi.org/10.14718/RevArq.2023.25.4305.

Jia Y, Ma H, Kang J. Characteristics and evaluation of urban soundscapes worthy of preservation. J Environ Manage. 2020;253: 109722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109722.

Zhou Z, Ye X, Chen J, Fan X, Kang J. Effect of visual landscape factors on soundscape evaluation in old residential areas. Appl Acoust. 2023;215: 109708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109708.

Huang L, Kang J. The sound environment and soundscape preservation in historic city centres—the case study of Lhasa. Environ Plann B. 2015;42(4):652–74. https://doi.org/10.1068/b130073p.

Huang K, Kang P, Zhao Y. Quantitative research of street interface morphology in urban historic districts: a case study of west street historic district, Quanzhou. Herit Sci. 2024;12(1):226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01351-w.

Liu J, Yang L, Xiong Y, Yang Y. Effects of soundscape perception on visiting experience in a renovated historical block. Build Environ. 2019;165: 106375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106375.

Perez-Martinez G, Torija AJ, Ruiz DP. Soundscape assessment of a monumental place: a methodology based on the perception of dominant sounds. Landsc Urban Plan. 2018;169:12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.07.022.

Djimantoro MI, Martokusumo W, Poerbo HW, Sarwono RJ. The historical soundscape analysis of Fatahillah square, Jakarta. Acoustics. 2020;2(4):847–67. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics2040048.

De Pessemier T, Van Renterghem T, Vanhecke K, All A, Filipan K, Sun K, et al. Enhancing the park experience by giving visitors control over the park’s soundscape. J Amb Intel Smart En. 2022;14(2):99–118. https://doi.org/10.3233/ais-220621.

Liu A, Wang XL, Liu F, Yao C, Deng Z. Soundscape and its influence on tourist satisfaction. Serv Ind J. 2018;38(3–4):164–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2017.1382479.

Yilmaz NG, Lee PJ, Imran M, Jeong JH. Role of sounds in perception of enclosure in urban street canyons. Sustain Cities Soc. 2023;90: 104394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104394.

Zhou Z, Kang J, Jin H. Factors that influence soundscapes in historical areas. Noise Control Eng J. 2014;62(2):60–8. https://doi.org/10.3397/1/376206.

Masullo M, Bilen AO, Toma RA, Guler GA, Maffei L. The restorativeness of outdoor historical sites in urban areas: physical and perceptual correlations. Sustainability. 2021;13(10):5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105603.

Han KT. A reliable and valid self-rating measure of the restorative quality of natural environments. Landsc Urban Plan. 2003;64(4):209–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-2046(02)00241-4.

Engel MS, Fiebig A, Pfaffenbach C, Fels J. A review of the use of psychoacoustic indicators on soundscape studies. Curr Pollut Rep. 2021;7(3):359–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40726-021-00197-1.

Zeng C, Lin W, Li N, Wen Y, Wang Y, Jiang W, et al. Electroencephalography (EEG)-based neural emotional response to the vegetation density and integrated sound environment in a green space. Forests. 2021;12(10):1380. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12101380.

Fiebig A, Jordan P, Moshona CC. Assessments of acoustic environments by emotions—the application of emotion theory in soundscape. Front Psychol. 2020;11: 573041. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.573041.

Jo HI, Jeon JY. Compatibility of quantitative and qualitative data-collection protocols for urban soundscape evaluation. Sustain Cities Soc. 2021;74: 103259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103259.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL, Strutzel E. The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nurs Res. 1968;17(4):364.

Moshona CC, Fiebig A, Aletta F, Chen X, Kang J, Mitchell A, et al. A framework to characterize and classify soundscape design practices based on grounded theory. Noise Mapp. 2024;11(1):20240002. https://doi.org/10.1515/noise-2024-0002.

Ma L, Zhang X, Wang GS. The impact of enterprise social media use on employee performance: a grounded theory approach. J Enterp Inf Manag. 2022;35(2):481–503. https://doi.org/10.1108/jeim-08-2020-0331.

Muller HL. A grounded practical theory reconstruction of the communication practice of instructor-facilitated collegiate classroom discussion. J Appl Commun Res. 2014;42(3):325–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2014.911941.

Bratianu C. Toward understanding the complexity of the COVID-19 crisis: a grounded theory approach. Manag Mark. 2020;15:410–23. https://doi.org/10.2478/mmcks-2020-0024.

Nurmi N, Pakarinen S. Virtual meeting fatigue: exploring the impact of virtual meetings on cognitive performance and active versus passive fatigue. J Occup Health Psych. 2023;28(6):343–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000362.

Nelson J. Using conceptual depth criteria: addressing the challenge of reaching saturation in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2017;17(5):554–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116679873.

Lopez BG. Incorporating language brokering experiences into bilingualism research: an examination of informal translation practices. Lang Linguist Compas. 2020;14(4):e12361. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12367.

Zhou J, Mai Z, Yip V. Bidirectional cross-linguistic influence in object realization in Cantonese–English bilingual children. Biling-Lang Cogn. 2021;24(1):96–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728920000231.

Noble H, Heale R. Triangulation in research, with examples. Evid-Based Nurs. 2019;22(3):67–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103145.

Rasoolimanesh SM, Seyfi S, Rather RA, Hall CM. Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tour Rev. 2022;77(2):687–709. https://doi.org/10.1108/tr-02-2021-0086.

Li H, Lau S-K. A review of audio-visual interaction on soundscape assessment in urban built environments. Appl Acoust. 2020;166:107372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2020.107372.

Liu J, Kang J, Behm H, Luo T. Effects of landscape on soundscape perception: soundwalks in city parks. Landsc Urban Plan. 2014;123:30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.12.003.

Yu L, Kang J. Factors influencing the sound preference in urban open spaces. Appl Acoust. 2010;71(7):622–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2010.02.005.

Garcia-Hernandez M, de la Calle-Vaquero M, Yubero C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability. 2017;9(8):1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081346.

Merciu F-C, Petrisor A-I, Merciu G-L. Economic valuation of cultural heritage using the travel cost method: the historical centre of the municipality of Bucharest as a case study. Heritage. 2021;4(3):2356–76. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4030133.

Khalaf RW. A proposal to apply the historic urban landscape approach to reconstruction in the world heritage context. Hist Environ Policy. 2018;9(1):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2018.1424615.

Been V, Ellen IG, Gedal M, Glaeser E, McCabe BJ. Preserving history or restricting development? The heterogeneous effects of historic districts on local housing markets in New York City. J Urban Econ. 2016;92:16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2015.12.002.

Garau C, Annunziata A, Yamu C. A walkability assessment tool coupling multi-criteria analysis and space syntax: the case study of Iglesias, Italy. Eur Plan Stud. 2024;32(2):211–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1761947.

Li J, Krishnamurthy S, Roders AP, van Wesemael P. State-of-the-practice: assessing community participation within Chinese cultural World Heritage properties. Habitat Int. 2020;96: 102107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102107.

Sarwono J, Sudarsono AS, Hapsari A, Salim H, Tassia RD. The implementation of soundscape composition to identify the ideal soundscape for various activities. J Eng Technol Sci. 2022;54(1): 220107. https://doi.org/10.5614/j.eng.technol.sci.2022.54.1.7.

Jeon JY, Jo HI, Lee K. Psycho-physiological restoration with audio-visual interactions through virtual reality simulations of soundscape and landscape experiences in urban, waterfront, and green environments. Sustain Cities Soc. 2023;99: 104929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104929.

Lafay G, Rossignol M, Misdariis N, Lagrange M, Petiot JF. Investigating the perception of soundscapes through acoustic scene simulation. Behav Res Methods. 2019;51(2):532–55. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1138-0.

Medvedev O, Shepherd D, Hautus MJ. The restorative potential of soundscapes: a physiological investigation. Appl Acoust. 2015;96:20–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2015.03.004.

Xiao J, Lavia L, Kang J. Towards an agile participatory urban soundscape planning framework. J Environ Plann Man. 2018;61(4):677–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1331843.

Papadakis NM, Aletta F, Kang J, Oberman T, Mitchell A, Aroni I, et al. City, town, village: potential differences in residents soundscape perception using ISO/TS 12913-2:2018. Appl Acoust. 2023;213: 109659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109659.

Li M, Han R, Xie H, Zhang R, Guo H, Zhang Y, et al. Mandarin Chinese translation of the ISO-12913 soundscape attributes to investigate the mechanism of soundscape perception in urban open spaces. Appl Acoust. 2024;215: 109728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109728.

Guo X, Liu J, Chen Z, Hong X-C. Harmonious degree of sound sources influencing visiting experience in Kulangsu Scenic Area, China. Forests. 2023;14(1):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14010138.

Xiao J, Hilton A. An investigation of soundscape factors influencing perceptions of square dancing in urban streets: a case study in a County Level City in China. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2019;16(5):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050840.

Han Z, Kang J, Meng Q. Effect of sound sequence on soundscape emotions. Appl Acoust. 2023;207: 109371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109371.

Wu Y, Li N, Xia L, Zhang S, Liu F, Wang M. Visual attention predictive model of built colonial heritage based on visual behaviour and subjective evaluation. Hum Soc Sci Commun. 2023;10(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02399-y.

Hong JY, Jeon JY. Exploring spatial relationships among soundscape variables in urban areas: a spatial statistical modelling approach. Landsc Urban Plan. 2017;157:352–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.08.006.

Verma D, Jana A, Ramamritham K. Predicting human perception of the urban environment in a spatiotemporal urban setting using locally acquired street view images and audio clips. Build Environ. 2020;186: 107340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107340.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the interviewees for their participation and patience.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [Grant Number 52178070, 52308089, 52208101].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yiming Hu: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization. Qi Meng: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. Mengmeng Li: investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. Da Yang: investigation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Translation of the interview process

Category 类别 | Question Foci 具体问题 |

|---|---|

Introduction 介绍 | Experimental purpose, research scope, confidentiality standards, etc. 实验目的、研究范围、保密标准等 |

Background Information 背景信息 | Interview number, name, age, gender, education background 访谈号码, 姓名, 年龄, 性别, 教育背景等 |

Perception of Authenticity 原真性感知 | Imagine a scenario where you are about to travel to a historic district. What would you like it to feel like? 想象一下这样一个场景:你要去一个历史街区旅行。 你希望这个街区呈现什么状态? |

How would you rate the trip? 你会如何评价这次旅行 | |

Current State 当下现状 | What sounds enhance or diminish the authenticity? 增强活破坏原真性的声音有哪些 |

What things or actions in the district made your experience more historical? And does this matter have a big impact? 街区内的什么事物或活动领你的经历更具历史意义 这件事有很大影响吗 | |

Creation of Authenticity 原真性营造 | 1. Favourable factors of authenticity 原真性的有利因素 (1) What things or actions made your experience better? (More authentic? ) (2) Does this matter have a big impact? Does this have to happen in the district? (3) How did you feel about it? (1)哪些事情或行为使你的体验更好?(更具原真性?) (2)这件事影响大吗?这件事一定要发生在这个街区吗? (3)你对此感觉如何? |

2. Unfavourable factors of authenticity 原真性的不利因素 (1) What things and actions make your experience worse? (Less authenticity? ) (2) Does this matter have a big impact? Does this have to happen in the district? (3) How did you feel about it? (1)哪些事情或行为使你的体验更差?(不具原真性?) (2)这件事影响大吗?这件事一定要发生在这个街区吗? (3)你对此感觉如何? |

Appendix 2

Historic district | Beijing Dashilan | Shanghai Bund | Harbin Laodaowai | Wuhan Jianghan Road | Guangzhou Shamian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Location | 39° 54′ N 116°25′ E | 30° 40′ N 120° 52′ E | 44° 04′ N 125° 42′ E | 29° 58′ N 113° 41′ E | 23° 06′ N 113° 17′ E |

Area | 1.15 km2 | 1.01 km2 | 0.47 km2 | 1.27 km2 | 0.32 km2 |

Construction time | 1420 | 1844 | 1890s | 1906 | 1860 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Meng, Q., Li, M. et al. Enhancing authenticity in historic districts via soundscape design. Herit Sci 12, 396 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01515-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01515-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessing urban renewal efficiency via multi-source data and DID-based comparison between historical districts

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Study on the correlation between soundscape perception and pro-environmental behaviors in Grand Canal National Cultural Park based on the expert perspective

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Analysis of the renewal of Nanjing Confucius temple block based on fold theory

GeoJournal (2025)