Abstract

World Heritage Sites (WHSs) have enormous charm and Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), thereby attracting many visitors and exerting pressure on heritage protection and conservation to some degree. The current investigation uses the stimulus‒organism‒response (S-O-R) model, chooses the World Natural Heritage Site of Mount Sanqingshan National Park as a case study, utilises structural equation modelling as a technical method and relies on 565 visitors’ experience perception samples to investigate tourists’ perceived behavioural intentions towards WHS conservation. The following relational outcomes are attained. (1) As stimulus factors, tourism involvement, service quality and OUV attractiveness positively influence tourists’ perceived value perceptions, place attachment and satisfaction, although the assumption that OUV attractiveness to tourist satisfaction is not supported; (2) in terms of organic transformation, tourists’ value perceptions and satisfaction are important for heritage protection, while the assumption of place attachment for WHS protection is not tenable; (3) a framework for the impact mechanism of tourism heritage protection according to the S-O-R model is established, which generally shows that tourists’ perceptions and emotional attitudes have positive impacts on WHS protection intentions; and (4) relevant measurements to improve WHS protection and tourism management are proposed to support the sustainable development and heritage conservation of WHSs. This research broadens the horizon of WHS conservation and has meaningful practical significance and theoretical value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research background

World Heritage Sites (WHSs) have been recognised worldwide as the most valuable cultural resources and natural marvels to humanity; WHSs focus on the classical creativity of our ancestors and the masterpieces of nature’s alchemy. They are irreplaceable treasures and have Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) for all humanity. Therefore, it is necessary to protect and inherit their lofty values, which is also the essential premise of the ‘Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage’1,2. Moreover, the majority of WHSs are hotspots for tourism and local economic growth; have important cultural, civilizational, scientific, aesthetic, historical, social and economic value; and help to rapidly develop the tourist industry. As of August 2024, there are 1223 WHSs worldwide, spread across 169 countries and regions. With 59 WHSs, China is undoubtedly an important country in terms of such sites; coupled with the country’s large population and strong tourism demand, tourism development in China’s WHSs is also very rapid, resulting in enormous pressure on and even threats to these sites, which can cause certain difficulties in the protection of World Natural Heritage Sites (WNHSs)3,4,5. Therefore, is it a blessing or a curse for developing countries in Asia to have sites listed as WHS? Mount Sanqingshan National Park (MSNP) successfully applied for WHS status in 2008, and the number of tourists soared from 580,000 in 2002 to 28.98 million in 2023, which undoubtedly put enormous pressure on the sustainable development of MSNP. Well-developed WHSs often face challenges such as overcrowding, capacity overload, inadequate tourism facilities and poor service quality, which pose significant challenges to the protection of OUV and the healthy development of WHSs4,6. Such challenges also seriously affect the quality of the tourist experience and satisfaction and reduce OUV attractiveness, which is not conducive to the healthy development of the tourism industry or the protection of WHSs7. Tourists, as important stakeholders in tourism activities at WHSs, significantly influence the protection and sustainable development of WHSs through their attitudes, behaviours and quality of experience. Visitors are beneficiaries, contributors to heritage protection and supervisors of heritage protection. Therefore, inspecting the effects of visitors’ experience perceptions on their behavioural intentions to safeguard WHSs is highly valuable.

Tourists are inherently associated with heritage conservation and sustainable development at WHSs, as Kempiak et al. found when they investigated the complex associations among tourism conflict events, tourist motivation, experience perceptions and the development of tourism at WHSs8. Scholars have examined tourists’ attitudes and behavioural intentions at WHSs from various perspectives, including tourism involvement, tourism congestion, tourism capacity, OUV attractiveness, place attachment and satisfaction7,9,10,11,12,13. With regard to OUV, an important value system and significant positioning have been highlighted and manifested14. From a brand marketing viewpoint, the popularity of WHSs can attract travellers and create a local identity, and tourists’ appreciation plays an important role in destination loyalty8,14. The attractiveness of WHSs has a certain influence on destination attachment, which contributes to the interpretation of OUV and increases tourists’ satisfaction15,16,17. In addition, scholars have conducted research from the perspectives of tourist value perception, place identity, the tourist experience, tourism services, environmentally friendly attitudes and heritage conservation, analysing tourists’ multidimensional perceptions of WHSs13,17,18,19.

Moreover, the charm of OUV, with its strong appeal, has a definite influence on visitors’ satisfaction, heritage conservation and sustainable development of WHSs2,20. The relevant research conclusions have indicated that the uniqueness, attractiveness and aesthetic, cultural, educational, scientific, ecological, and other values of WHSs further highlight the core position of OUV21,22. The attractiveness of OUV has a crucial effect on tourists’ destination loyalty, value perception, destination attachment, environmental awareness behaviour and heritage protection attitude behaviour11,13,15,23. Tourism service quality has an effect on visitors’ experience, satisfaction, and destination attractiveness perceptions. When tourists feel that a site is worth the money and the trip, it will stimulate positive emotions and generate destination identity, which is conducive to disseminating OUV, responsible environmental behaviour and sustainable development throughout WHSs24,25. Travel journeys comprise an experiential and emotional pursuit, and a good-quality tourism experience promotes heritage preservation26. If overcrowding and excessive tourism lead to a deterioration in tourists’ experience quality and reduced destination attractiveness, then these factors are not conducive to the protection and healthy development of WHSs9,27.

In view of the characteristics of WHSs that require long-term protection, scholars have focused on the correlations among WHS conservation and tourism growth in view of tourists’ perceptions, governmental behaviours, managerial plans, local involvement and other stakeholders28,29. Many visitors constitute the majority of heritage tourist actions and have a direct impact on the ecological environment, community psychology, service facilities and social capacity of WHSs. The comprehensive attractiveness of WHSs has a certain influence on visitors’ place loyalty and thus contributes to WHS protection and sustainable development15,30. Relevant findings have examined the associations among tourists’ value perceptions, experience quality, satisfaction and responsible behaviour towards the environment and WHS conservation23,31,32. However, tourists are not only the main actors of ecological protection, a low-carbon economy and good tourism but also important stakeholders of various negative impacts of tourism. WHS tourism is considered an exclusive approach undertaken by tourists with elevated senses, which can encourage tourists to actively protect heritage. When WHS tourists experience such tourism, how do their value perceptions, local attachment and emotional state affect their attitudes or behaviours towards WHS conservation? How do these influencing factors transform and affect the underlying mechanisms of WHS conservation? These issues are the focus of the current article.

The intentions of environmentally responsible behaviour and heritage conservation behaviour mostly concern the theory of planned behaviour (TPB)30,33, the value-belief-norm (VBN) model34, sense of place15, perceived tourist value19,35, the tourist experience and resource protection theory36 and the stimulus‒organism‒response (S-O-R) model13,37,38. According to our literature review, visitors’ intentions to preserve WHSs are less studied through the S-O-R framework. The purpose of the S-O-R model is to explain how a person changes his or her private condition under the stimulation of external environmental factors to respond to behavioural intentions37. The inner state is a mediator of external stimulation and the final response, and the stimulation can activate cognitive and emotional conditions so that the individual can settle whether to accept approach behaviour or avoidance performance39. Stimulating factors incorporate subjective and psychosocial inspiration, which triggers the individual’s cognitive and emotional state and leads to the individual’s behavioural inclinations and psychological consequences40. The S-O-R model has been extensively and efficiently applied in the areas of marketing consumption, tourist satisfaction, ecological conservation, etc., and represents a significant logical outline for explaining the behavioural process of people13,38,39,41,42. This study is based on the tourism experience of tourists at a certain WNHS via S-O-R theory. The stimulating factors include tourism involvement, OUV attraction and service quality-related dimensions, while the organism factors include perceived value, place attachment and tourist satisfaction, all of which encourage visitors to generate resultant intrinsic responses and intentional outcomes of heritage protection. In the following chapters, we use the S-O-R model to summarise the pertinent measurements, present the investigation assumptions, conduct research design and data collection, discuss the results, and propose countermeasures and suggestions.

Hypotheses construction

Stimulus

Tourist involvement

Involvement is an imperceptible condition of incentive or attention, which is a certain correlation that an individual somewhat observes. It is considered a psychological state of an individual, and its intensity depends on the degree of correlation between an individual and his or her own needs, values and goals, which mainly include ego involvement, leisure involvement, tourist involvement and activity involvement. According to the concept of involvement, tourists’ involvement is considered a psychological state of incentive, activation and attention that is activated by the tourist destination and associated tourism products43. When leisure and consumer behaviour are studied, it is generally assumed that involvement is a multidimensional concept and that tourism involvement is divided into three dimensions, namely, attractiveness, self-expression and centrality44. The tourism involvement scale is generally composed of the dimensions of enjoyment, self-representation, importance, emblem, risk possibility and outcomes45. In the scope of tourist recreation, the influential psychosocial attachment gages include the Assessment of Leisure and Recreation Involvement, the Personal Involvement Inventory, the Consumer Involvement Profile, the Enduring Involvement Scale, etc45. Tourism involvement has received attention in many aspects of tourism research, including the effects of tourist involvement on satisfaction, environmental protection and local attachment. Relevant scholars have studied the composition of the tourist involvement scale46, the relationship between tourism involvement and visitors’ experience47, and the interaction between tourism involvement and tourism motivation48, especially the interaction mechanism between tourism involvement and destination brand attractiveness value co-creation49. Enduring tourist involvement has significant effects on tourist service quality and tourists’ experience and is correlated with involvement, authenticity, destination brand, tourism memory, perceived tourism value and satisfaction50,51,52. Relevant articles have examined the interactions among tourism involvement, the tourist experience and place attachment in the context of the destination lifestyle, and the relevant results have been verified53. Tourism involvement has an important effect on tourist satisfaction and improving environmental protection behaviour, which has been demonstrated in ecotourism and heritage conservation12,54.

OUV attractiveness

WHSs have an important impact on cultural or natural beauty, are composed of national or regional cultural or natural sacred land and have OUV for all humanity, all of which serve as reasons why they were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List1. OUV represents the most intuitive expression of attractiveness to tourism development at WHSs and the most direct driving force of tourism growth2,20, which is the core value of WHSs in terms of tourist motivation and emotional experience55. Destination attractiveness refers to the important representation that the destination meets personal needs, including core and secondary attractions, which are the main driving forces for tourists to travel56. By measuring tourists’ perceptions of OUV, aesthetic, ecological, cultural, social and economic values of WHSs can improve heritage conservation14. The OUV of WHSs and tourists’ views on such OUV are assessed, with the results mainly covering the importance, uniqueness, influence, values and attraction of the sites’ OUV57. Scholars have investigated the uniqueness of destinations, tourist attraction settings and the comprehensive impact of destination attraction on tourists and demonstrated that destination attractiveness plays a key role in tourists’ satisfaction, especially through the ability of the shared value creation of WHSs to attract tourists better13,21,22. The ‘extraordinary’ or ‘wonderful’ symbolic features of WHSs greatly attract tourists, which is also a common achievement that goes beyond actual monument protection58. When the protection of a site’s OUV is inadequate, then its interpretation level is poor, its intercultural communication is difficult and conflict among the worldwide and native backgrounds leads to a reduction in tourists’ perceived value, which impacts tourists’ experience and satisfaction quality59,60,61. Research shows that OUV attraction has a crucial influence on tourists’ loyalty to tourist value perception, destination attachment, environmental awareness behaviour and the attitude-behaviour of heritage protection11,15,23. Research shows that embodied insights into a destination’s attraction can enhance local attachment, tourism appreciation and environmentally responsible behaviour; change tourists’ attitudes; and increase tourist satisfaction62,63. As the core charm of WHSs, OUV influences visitors’ experience quality, local affection and tourist satisfaction. Moreover, tourist satisfaction, interaction and revisits also increase the attractiveness of travel destinations8,14,15,64,65.

Service quality

The service quality (GM) model of the consumer-oriented management decision-making concept views service quality as the subjective assessment of customers’ service expectations and perceived comparison and ultimately determines the level of satisfaction66. Customer value theory posits that consumer value is an in-depth assessment of product effectiveness according to the reward state67. The performance measurement-based American Customer Satisfaction Index is applied to estimate service quality and consumer experience68. The hierarchical service quality model includes communication, physical setting and outcome features and assesses the quality of each sub dimension according to authenticity, sympathy and empathic concern69. The SERVQUAL concept is composed of five dimensions and 22 measurement indicators, including ten crucial factors such as communication, ability, politeness, credibility, reliability, responsiveness, security and customer understanding67. Service quality refers to the evaluation that tourists relish at tourism destinations. When the level of service quality is high, visitors are more eager to invest sojourn, wealth and vigour. Therefore, people who have a positive attitude towards service quality should develop a strong sense of value by comparing their benefits or sacrifices when consuming products and services25,70. Service quality has a key effect on tourist satisfaction, maintainability, the retention rate, image and the attractiveness of a destination. The environmental atmosphere, accessibility, convenience and comfort of a destination’s related tourism facilities are connected with the experience and evaluation of service quality and overall tourist satisfaction52,71. The most immediate expression of tourists’ quality experience is the functional experience of tourists, which mainly includes interactions among the visitors’ incentive and behaviour, the attractiveness of the destination, the tourist service amenities and the destination managerial level72. When visitors discover value for money, they develop optimistic feelings, local identities and even attachments, thereby increasing tourist satisfaction12,18,19. Improving the quality of tourist services can incentivize visitors’ consciousness of environmental conservation at destinations, thereby stimulating them to undertake environmentally friendly actions. In accordance with the SERVQUAL and HISTOQUAL outlines of the service quality evaluation system, which combine the individualities of cultural and historical tourism, the HERITQUAL model is proposed for measuring destination service quality, including stress, bearing ability and capital construction, connectivity facilities and local engagement73. Related studies have shown that the accessibility of scenic destinations, the effectiveness of interpretation systems, the psychological needs of tourist areas, and the level of emotional experience realisation are important factors affecting tourists’ place attachment, environmental stewardship behaviour and satisfaction, which may alter tourists’ behavioural orientation to heritage sites, further heritage protection and the sustainable development of WHSs15,74,75.

Organisms

Perceived value

The perception of tourism value is usually defined as evaluating tourism products, such as tourist experiences, product value and tourist satisfaction. This value determines whether tourists find consumption worthwhile and how satisfied they are overall after engaging in tourism76. When tourists feel that their expectations are met, they develop optimistic and positive emotions towards the destination and are advantageous to destination attachment12,24. Perceived tourism value is the amount of tourist incentive and perceived tourists’ experiences77. Tourism perceived value can be divided into functional, emotional, social and novel values, which have a certain influence on visitors’ satisfaction, environmental behaviour and other aspects18. Tourism motivation and tourist involvement are used as antecedent variables to examine visitors’ experience quality, which can include functional, social and episodic values64. Related findings have shown that symbolic, experiential and functional perceptions of consumer value influence visitors’ destination attachment, satisfaction and heritage protection behaviours19. In terms of perceived tourism value, the perceived quality of tourism resources is the most significant factor influencing visitors’ engagement in environmental protection, followed by tourist service quality and the tourism activity experience. In particular, the level of tourist satisfaction has certain impacts on increasing tourist value and environmentally conscious behaviours. Thus, perceived value is an important predictive representation of tourist behaviour78. The results show that visitors’ perception values may improve their inner state and alter their behavioural intentions in terms of the correlations among experience quality, satisfaction and tourist behavioural choice at WHSs13,75. Findings related to the classical Chinese Suzhou Gardens indicate that tourists’ perceived value and incentives significantly influence WHS conservation15. Using the Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic Area as a WNHS, a previous study showed that a good visitor experience results in the exclusive sense and significance of tourist destinations, thereby helping visitors establish destination attachment, which is favourable for protecting WHSs and showing heritage value23. In summary, tourists’ perceived value has a certain influence on heritage conservation and environmental protection intentions5.

Place attachment

Sense of place is involved in the properties of the sites themselves, personal emotions and individuals’ attachment to the place through experiences, memories and behavioural intentions. It mainly includes place identity and dependence, where place identity is a functional bond among the person and the place and place dependence is emotional attachment79,80. Sense of place is divided into place dependence, influence, identification and attachment. Previous findings suggest that the measurement of these factors significantly affects place satisfaction and environmental performance81. One’s view of place includes physiological and psychological aspects and is perceived, comprehended and envisaged in narratives82. The tourist journey is a significant process during which people observe and sense settings; thus, settings serve as an important point of interaction for people, especially places with significant symbolic meaning to tourists. Previous scholars have studied the place attachment series chain and the creation process of tourists’ destination affection29,83. Prior research findings suggest that tourists’ attachment to a site considerably affects their attitudes and behaviours regarding resource conservation and heritage protection at WHSs15,23. People’s psychological influence on the environment can motivate them to behave responsibly towards the environment. Local connectedness is a leading variable in pro-environmental conservation and heritage preservation and may trigger travellers’ intentions to protect heritage positively38. Local identity is a significant foundation for the environmental conservation of destinations and positively influences individuals’ appreciation of a destination38,63,84. The generalisability of the psychometric model allows for the evaluation of place attachment efficacy and demonstration of not only visitors having a sounder understanding of the target but also heritage tourism generating positive psychological consequences85. Prior research findings indicate that destination attachment is a significant antecedent variable of environmentally friendly conservation and preservation, altering tourists’ emotional experience and promoting heritage protection38,59,60,86. Overall, place attachment plays a crucial role in satisfaction and subsequently affects tourists’ experience quality by increasing and motivating tourist revisit rates, encouraging understanding, protecting OUV and promoting the inheritance of cultural and heritage values; thus, it has significant implications for the protection and sustainable tourism development of WHSs62,87.

Tourist satisfaction

Satisfaction expresses a person’s level of satisfaction with and psychological state regarding a product or service experience. If a person’s actual feelings meet or exceed expectations, then he or she will be satisfied and vice versa10,88,89. Visitors’ satisfaction is the outcome of the interplay among visitors’ experiences at the destination and their initial expectations of the destination. It is the most commonly used means by which to evaluate the quality of leisure and recreational experiences, including the demand model, marginal utility theory and the cognitive dissonance framework90,91. Tourist satisfaction is an optimistic state or affection according to tourists’ expectations and actual experiences92. The theory of value harmony in consumer behaviour states that visitors’ satisfaction involves functional harmony and visual harmony. The former is involved in harmony among tourists’ expectations and perceptions, whereas the latter is involved in harmony with visitors’ self-perception and place image93. Especially since the beginning of the 21st century, the tourism-focused notion of tourism management has become widespread and more attention has been given to research on destination satisfaction. Satisfaction is the basis for evaluating tourist attractions, tourism products and tourism services. It is generally tested via perceived overall performance and expectancy models, which are compared with the quality of preferred tourist leisure and posttrip experiences, which may affect destination selection, product consumption during a trip and the decision to visit again88,92. Destination image has a substantial influence on visitor satisfaction; e.g., an optimistic impression can lead to greater visitor satisfaction, thereby increasing destination loyalty and having the opportunity to promote economic growth10,94. The essential components of the satisfaction configuration include correlations, output‒input expectations and a sense of justice, all of which play crucial roles in forecasting attitude-behaviour, community participation and environmental behaviour in regard to protecting WHSs and supporting tourism development95,96,97. With the emergence of ecological tourism and inheritance tourism, research on tourist satisfaction has provided a new perspective on environmental carrying capacity. The basic assumption is that as the number of tourists increases, congestion also increases, leading to a decrease in tourist satisfaction98. The research community has examined the comprehensive impact of visitors’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction, including the tourism scale and team familiarity, various kinds of services, the efficiency of interpretation systems, the quality of the tourism experience and destination crowding99,100. When overall visitors’ experience quality exceeds expectations, it has a positive influence on satisfaction and increases both tourists’ loyalty and revisit rates, which is more conducive to interpreting the value of WHSs and promoting economic growth in tourism10,94. From a systemic perspective, satisfaction covers the entire process of tourist travel, which has a positive influence on visitors’ experience quality, perceived value, motivation realisation, etc., and contributes to elucidating OUV and the sustainable development of WHSs99,100,101.

Response

Heritage conservation

The attitudes and behaviours of tourists towards the environment and heritage conservation are key influencing factors for heritage protection and sustainable tourism development. Tourists’ responsible behaviour towards the environment is a starting point of WHS protection, which refers to the behaviour of tourists that minimises their influence on co-friendly settings and improves the sustainable development of tourism destination resources. It is also considered responsible for environmental behaviour and is an important symbol of heritage safety102. The relevant research findings indicate that tourist attractions, emotional imagery, perceived tourism value and leisure involvement are key factors affecting green tourism behaviour. Therefore, by explaining and promoting OUV, we can inspire tourists to safeguard natural-cultural WHSs more effectively and engage in responsible behaviour12. By explaining and promoting the value of WHSs, heritage education is a significant means by which to comprehend and defend WHSs and stimulate the interest of stakeholders such as tourists, communities, governments and nongovernmental organisations, especially the general public and tourists, with the aim of promoting positive environmental behaviours and better protecting WHSs103. The relevant results explain the functions of environmental wisdom and sensibility in heritage conservation, as well as a correlation between environmental conservation and viable growth16,63. The main draw of OUV and its secondary attractive forces, such as visitors’ service amenities and native neighbourhoods, have a certain impact on local connectedness, tourist perception value and tourists’ attitudes-behaviours towards destination conservation3,23. Research has shown that conservation commitments, local attachment and entertainment participation influence visitors’ responsible environmental stewardship84. Improving service quality can improve visitors’ experience quality, increase their satisfaction and stimulate their environmental awareness12. In terms of environmental behaviour theory, the VBN model34, the TPB33 and the S-O-R framework13,37 are significant theoretical guidelines. In particular, the S-O-R model is a suitable framework for identifying environmental intentions and WHS protection mechanisms42 since tourism activities are a part of the emotional experience process, and the emotional state has a crucial influence on the intentions of tourist behaviour35. As a result, we adopt the S-O-R framework to examine the intention and mechanism of tourist heritage protection.

Conceptual model

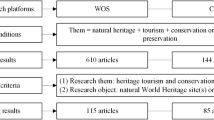

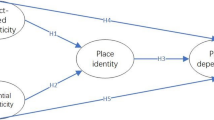

On the basis of these reviews and discussions, we suggest relevant assumptions and construct a theoretical outline in the following (Fig. 1).

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

H1a. Tourist involvement has a positive effect on perceived tourism value.

H1b. Tourist involvement has a positive effect on place attachment.

H1c. Tourist involvement has a positive effect on satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

H2a. OUV attractiveness has a positive effect on perceived tourism value.

H2b. OUV attractiveness has a positive effect on place attachment.

H2c. OUV attractiveness has a positive effect on satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

H3a. Service quality has a positive effect on perceived tourism value.

H3b. Service quality has a positive effect on place attachment.

H3c. Service quality has a positive effect on satisfaction.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Perceived tourism value has a positive effect on WHS conservation.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Place attachment has a positive effect on WHS conservation.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Tourist satisfaction has a positive effect on WHS conservation.

Methodology

Case site

MSNP is located in Jiangxi Province, China, covering 229.5 km2 with a maximum elevation of 1819.9 m. It is an AAAAA National Tourist Destination, a World Geological Park and a World Natural Heritage Site; it has won other distinctions and is also a famous Taoist shrine that has experienced cultural infiltration for thousands of years (Fig. 2). In 2008, the MSNP was acknowledged by UNESCO as having OUV, with unique granite pillars and peaks, lifelike granite moulding stones, rich ecological vegetation and a changing climate all coming together to create a unique landscape that presents fascinating natural beauty; thus, the site was declared a World Natural Heritage Site. Stating ‘揽胜遍五岳, 绝景在三清 (It is better than the five famous mountains in China and the most beautiful scenery is in Sanqingshan)’, Su Shi, who was a great poet during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 A.D.), highly praised this mountain. After WHS status was awarded, the tourism industry developed rapidly. In 2002, the person-time rate of tourists was 580,000 and the tourism revenue was 210 million CNY. However, by 2023, the person-time rate of tourists at the MSNP had soared to 28.98 million, with 26.62 billion CNY in tourist revenue. Moreover, issues such as tourist overload and excessive tourism, which have certain negative impacts on the tourist experience and heritage protection, especially the viable growth and healthier development of WHSs, have also been faced.

Questionnaire design

The first part of the questionnaire covers the basic demographic characteristics of tourists, travel organisation, travel motivation and other information. The second part of the questionnaire includes seven dimensions—tourism involvement, OUV attractiveness, service quality, perceived tourism value, place attachment, tourist satisfaction and WHS conservation—and contains 29 measurement items, which are derived from literature reviews and field investigations conducted on the case study by the research team, as shown in Table 1. The measurement items of tourism involvement include tourist interest, attractiveness, active learning and tourist status12,43,45,46,51. The measures of OUV attractiveness include the MSNP’s natural beauty, rich vegetation ecology and unpredictable canyon clouds; these factors are drawn from relevant research literature, WHSs’ listed rules concerning OUV and the preferences of tourists, who are important to the MSNP, especially considering the combination of OUV’s global macro narrative and tourists’ perceived localisation background3,14,63,104. The service quality metrics include tourism service elements, tourism service facilities and destination management of WHSs, which are mainly drawn from relevant literature and online comments from platforms such as Xiaohongshu and Ctrip, as well as preliminary research on destinations64,74,75,105. Measures of perceived value include representations of tourist value and the implementation of tourist motivation, which are mainly drawn from the relevant literature and early field surveys regarding the MSNP18,64,75,106. Measuring place attachment includes recognising deep feelings and memorable tourism experiences attached to the MSNP, which are derived mainly from the relevant literature15,81,85,107,108. Tourist satisfaction survey items include satisfaction and willingness to not only visit the MSNP again but also recommend that others visit; these factors are drawn mainly from the relevant literature88,92,101. The measurement items for heritage protection include attitudes and behavioural intentions regarding participation in WHS protection activities, compliance with heritage management regulations and preventing damage to heritage sites by others, which are mainly drawn from the relevant literature15,102,109 and the relevant provisions of the WHS convention1. The scores for each record are determined via a Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’.

Sampling and data analysis

Under the supervision of three professional researchers, nine bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral students who had undergone questionnaire distribution training conducted data collection on domestic tourists who had visited the MSNP recently and were thus selected as the subjects. The surveys were conducted mainly at the MSNP’s Jinsha and Waishuangxi cableways, as well as at the tourist centre and the gate square of the scenic spot. To promote the efficacy and quality of the questionnaire, stalls were erected at major exits, signs were posted advertising the questionnaire and small gifts were given to the participants. A total of 600 questionnaires were given out via convenience sampling. The low-quality samples that did not meet the requirements of the questionnaire were eliminated, and a total of 565 useable surveys were restored, for an effectual incidence rate of 94.2%. We conducted relevant interviews on tourism management, heritage protection, environmental capacity and service quality, community participation and other aspects of WHSs to discover a better, more exhaustive understanding of the relevant situation of the MSNP as a WNHS.

Structural equation modelling, which is widely used in the social sciences, was used for confirmatory factor analysis and SPSS 18.0 and AMOS 19.0 were applied for sample processing (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). When analysing sample data, it is necessary to confirm the reliability, validity and normality of the sample and decide whether the testing model violates the estimation hypothesis.

Results

Among the 565 tourists sampled, 53.9% were female, and 46.1% were male. A total of 68.0% of the tourists were younger than 30 years old, and 27.6% were between 30 and 40 years of age. Approximately 36.2% of the respondents reported a monthly per capita income of less than 1500 CNY, while 48.8% reported a monthly income of between 1500 and 5000 CNY. A total of 42.6% of the tourists had high school or college degrees, while 38.4% had a university degree or higher. The proportion of employees from enterprises and institutions was 35.3%, and that of students was 38.2%, which was associated with a sharp increase in the proportion of tourists from MSNP during the summer holidays. Among those travelling under travel agency itineraries (32.6%) and those travelling with friends and relatives (40.3%), the respondents’ main motivations for travelling was to enjoy the natural beauty (72.3%) and engage in a leisure-based vacation (18%); these factors comprised the overall composition of visitors and tourists at the MSNP.

Reliability and validity

At the significance level of 0.001, the Cronbach’s α value of the entire sample was 0.952, which was greater than 0.9, indicating that the internal reliability of the sample was good; the reliability coefficient of each measurement was greater than 0.8 (Cronbach’s α values ranging between 0.826 and 0.895), indicating that the reliability of each dimension was acceptable. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of the total questionnaires was 0.952, which was greater than 0.9, indicating that the structural validity of the sample was effective; the KMO value of content validity (0.745–0.881) was greater than 0.7, indicating that the designed questionnaire well represented the content to be gaged. The average variance extracted (AVE) value of each dimension (0.513–0.713) was greater than 0.5, which generally indicates that the observed variable is able to gage the potential variable to which it belongs. The composite reliability (CR) value (0.817–0.895) was greater than 0.8, indicating that the model’s validity was suitable, as shown in Table 2.

The discriminative validity of the samples was verified; the relevant findings are shown in Table 3. To judge discriminant validity in advance, chi square difference testing was applied. When the chi square difference between models attains a no significant difference, there is no discriminant validity among the constructs, which suggests that H0: Φ=1 cannot be rejected110. The chi square difference Δχ2 between the restricted and unrestricted models was greater than 3.85 (df = 1, p < 0.001), indicating that it reached a significant level111. The testing outcomes in Table 3, in which the chi square difference of each paired dimension is shown to be 184.624, 408.505, 223.559 and 220.617, indicate that there is discriminative validity among the samples shown in Table 4.

Through the mathematical testing of samples, related outcomes demonstrated that reliability and validity were suitable for confirmatory factor analysis.

Descriptive statistics

The mean value of each dimension indicates the degree of willingness of the subjects; the mean values on a five-point Likert scale range from 1.0 to 2.4 for disapproval, 2.5–3.4 for neutrality, and 3.5–5.0 for approval112. The mean values of the tourist involvement, OUV attractiveness and service quality dimensions were 4.20, 4.39 and 3.93, respectively, suggesting that the stimulus factors met with approval; in particular, OUV attraction was very high, indicating that the MSNP has a high level of charm for a WHS. The average scores of the perceived value, place attachment and tourist satisfaction dimensions were 4.22, 4.00 and 3.80, respectively, implying that the organism constructs had a relatively high degree of approval. The heritage conservation score was 4.16, indicating that the majority of visitors reported a robust desire to protect WHS destinations.

Measurement model

To examine the hypothetical correlations among potential variables, it is necessary to test and analyse the structural model. First, the absolute value of the skewness of the observed variable was found to be 0.599–1.823, which was lower than the threshold of 2.58. The absolute value of kurtosis was found to be 0.170–5.216, which was lower than the threshold of 8; thus, the sample was considered to conform to a multivariate distribution. Second, common method bias of the testing sample was involved in the artificial covariance among the predictive and standard variables triggered by the same data source, measurement setting, project background and properties of the project itself. Harman single-factor testing was used for factor exploratory analysis, and the cumulative contribution rate of the first factor was found to be 19.98%, indicating that common method bias was acceptable113. Furthermore, when analysing the fitness index of the overall model, Hair suggested that one should first test whether the parameters of the model violate the estimation, including whether there is a negative error variance and whether the standardised parameter coefficient is less than or equivalent to one114. On the basis of such computation, the measured value of the error variance was found to range from 0.019 to 0.055, and the standardised parameter coefficient ranged from 0.614 to 0.864, which was less than 1, indicating that the model did not violate the estimation and met the goodness-of-fit requirements. The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the parameters of the conceptual framework, and the relevant fit index did not reach the ideal value; thus, the model needed to be further modified. Because some potential variables in the measurement model can be correlated and there is also a certain connection between tourism involvement and OUV attractiveness in theory, the model was modified. The fit indices of the structural model were found to be relatively suitable (X2/df=2.738, GFI = 0.889, RMSEA = 0.056, IFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.934, CFI = 0.941, NFI = 0.922, PGFI = 0.738, PNFI = 0.810, PCFI = 0.837)115,116, as shown in Table 5.

Structural model

The validation results of the relevant assumptions and structural models are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 6.

Discussion

The relevant outcomes are presented in Fig. 3 and Table 6. All of the research hypotheses were supported except for the hypotheses H2c and H5. The specific discussion presented below is conducted based on the S-O-R model and presents research theories and practical implications, as well as research limitations and prospects.

Analysis findings

Analysis of the role of the stimulus

The stimulus includes three dimensions, i.e., tourist involvement, OUV attractiveness and service quality; three general hypotheses, i.e., H1, H2 and H3; and nine proposed secondary hypotheses.

H1, a second-level hypotheses on perceived tourist value, place attachment and tourist satisfaction, which are all supported by tourist participation, indicates that tourist participation has a certain influence on visitors’ motivation realisation, value perception of WHSs and visitors’ satisfaction.

H1a is based on the assumption that the positive impact of tourist involvement on visitors’ value perceptions is consistent with relevant research findings49,64, which indicate that proactive tourism involvement facilitates the acquisition of tourists’ value and the realisation of tourist motivation. H1b suggests that tourism involvement has a positive influence on local attachment, which is coherent with relevant findings53; fully comprehending the emotional and functional impact of tourism integration on tourists’ destinations highlights the significant position of tourist involvement in determining tourists’ place identity and dependence. H1c suggests that tourism involvement has a significant influence on visitors’ satisfaction, which has been verified by other relevant results48,50,52; this indicates that proactive involvement in and a better understanding of tourist destinations enhance tourists’ experience perception and satisfaction. Overall, a proactive attitude towards tourism involvement leads to more positive place identity and attachment among tourists. Although tourism is a temporary behaviour that generates fleeting attachment, it plays a crucial role in improving visitors’ experience quality and satisfaction and thereby has a certain influence on destination environmental protection and heritage preservation12,54.

H2, i.e., the hypothesis that OUV attraction affects perceived tourism value and place attachment is confirmed, suggesting that tourism integration has a positive influence on the perception of the value of WHSs and place affection, and that the hypothesis of satisfaction is not supported.

H2a suggests that OUV attractiveness is the core of WHSs, and tourists’ perceptions of OUV play a key role in realising visitors’ motivation and performance, which can stimulate tourists’ greater sense of tourism achievement2,11,13,15,20,23. H2b suggests that the attractiveness of OUV has a certain influence on destination attachment, implying the important effect of OUV on place identity and tourists’ attachment to the destination11,13,14,15,23,65. Therefore, when shaping correlations amid visitors and WHSs, we should pay special attention to strengthening the close connection between OUV and the region. On the one hand, we should emphasise the international perspective of OUV; on the other hand, we should strengthen the local transformation and connection of OUV. H2c, which is based on the assumption that OUV attractiveness has a certain influence on tourist satisfaction, was not supported in this study; this outcome may be related to the inadequate representation of OUV value, inadequate explanation, and even the gap between the global and local perspectives of OUV59,60,61. In particular, the large number of tourists during the survey period caused a certain degree of crowding, and the large cloud and fog in MSNP during the relevant time period caused the magnificent landscape to be covered, which may be the reason why the hypothesis of this study was not passed.

H3, which is based on the assumption that service quality has a certain influence on perceived tourism value, place attachment and visitor satisfaction, is fully supported. As a crucial opportunity for and medium through which tourists perceive WHSs, H3 also highlights the significance of tourists’ expectations and values of service quality at WHSs.

H3a suggests that service quality has a significant influence on perceived tourism value, indicating that good service quality plays a crucial role in improving experience quality, increasing tourist motivation, and increasing satisfaction, thereby improving and promoting tourists’ environmental behaviour and heritage conservation intentions25,70,72. H3b suggests that service quality has a certain influence on place attachment, indicating that tourism service quality plays a crucial role in shaping the correlation between tourists and settings, which is consistent with relevant research results12,18,19. H3c suggests that service quality has a certain influence on visitors’ satisfaction, which aligns with relevant conclusions117. Service quality incorporates many features, such as accommodations, meals, travel, shopping and entertainment, which are important factors affecting tourist satisfaction evaluation and experience quality. Therefore, improving service quality is the cornerstone of tourist satisfaction, which fully demonstrates the importance and necessity of ensuring tourist service quality in heritage tourism destinations.

Explaining the organic transformation effect

There are three factors examined herein, namely, perceived value, place attachment and tourist satisfaction. Hypotheses H4 and H6 are supported, suggesting that tourists’ perceptions of values and visitors’ satisfaction have a certain influence on heritage conservation. In addition to not supporting Hypothesis H5, this finding suggests that the assumption of place attachment to WHS protection is not evident in this study.

H4 suggests that perceived tourism value has a remarkable influence on WHS conservation, indicating that the realisation of good tourism motivation and a sense of tourism gain can promote heritage protection and the inheritance of heritage values, which is consistent with relevant research conclusions5,13,19,78. Therefore, enhancing tourists’ perceptions of tourism value and gains plays a crucial role in promoting heritage site conservation and environmentally friendly behaviour.

H5, i.e., the assumption that ‘place attachment has a positive effect on WHS conservation’ was not supported, indicates that the emotional state of the correlations amid visitors and destinations, man and place does not influence WHS protection, which is an important impact of destination commitment; this is related to the short stay time of tourists (85.0% of tourists do not stay overnight in MSNP) and the motivation of most tourists (72.1% of tourists take sightseeing as the purpose), indicating that there is a certain causal relationship between the weak connection among tourists and tourist destinations, which is also due to the environmental background of tourists’ attachment to the destination13,118; this further underlines the importance of heritage identity for heritage protection and the sustainable development of WHSs15,23,29.

H6 suggests that tourist satisfaction has a certain influence on WHS conservation, which is consistent with the relevant findings95,96,97,99,100,101. The comprehensive satisfaction status of tourists is an important indicator of heritage protection, fully demonstrating the importance of tourist satisfaction. Tourist satisfaction not only provides economic benefits but also has important value and significance for WHS protection, inheritance, utilisation and heathier development of heritage tourism destinations.

Exploring the response to heritage protection

We can see that under the S-O-R model, stimulating factors of tourists, such as tourism involvement, OUV attractiveness and service quality, play crucial roles and tourists’ perceived value, place attachment and tourist satisfaction are organically transformed by tourists, forming a comprehensive response to their attitudes and behaviours towards WHS protection3,12,13,23,35,42. This fully demonstrates the noticeable position of visitors as stakeholders in the protection of WHSs, especially the importance of tourists’ positive travel experiences, the fulfilment of travel motivations, positive human–land relationships and satisfaction with heritage protection; it was also the purpose of ‘World Heritage Convention for the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage’5.

Theoretical and practical implications

From a theoretical viewpoint, the S-O-R conceptual framework explores responses related to tourist involvement, the attractiveness of WHSs and service quality, and their perceived value, place attachment to and satisfaction with heritage protection. The proposed conceptual framework provides a new perspective for responsible environmental behaviour and heritage protection among visitors at WHSs, thereby expanding the scope of heritage protection research. The relevant research conclusions highlight the importance of heritage education and involvement for tourists, especially the necessity of interpreting, promoting, and disseminating the OUV of heritage sites, as well as the urgency of improving the quality of destination services. These are important stimulus factors for tourists who are entering a WHS’ destination. Moreover, under the influence of the organic transformation mechanism, stimulus factors influence visitors’ value view, destination attachment and satisfaction, thus representing a positive response to WHS conservation and sustainable development. This research provides a new outline for comprehending tourist behavioural intentions in WHS conservation, which can help better analyse tourist behaviour, elucidate OUV and further the healthier development of WHSs.

From the viewpoint of heritage site management and heritage protection practices, it is important to focus on improving not only visitors’ experience quality but also the level of representation, interpretation and promotion of OUV. First, it is necessary to strengthen WHS education and popular science and intensify the degree of visitors’ involvement, which will improve tourists’ perception of tourism value and strengthen their affinity with the destination. Second, we should enhance visitors’ experience quality at WHSs, strengthen the construction of service quality, and utilise advanced science and technology such as wisdom tourism, big data and artificial intelligence to increase the level of tourist service quality and the interpretation of the unique OUV of the site. We should aim to maximise tourist satisfaction, thereby contributing to WHS conservation for future generations. Third, it is necessary to reasonably control the tourist capacity of WHSs, manage the number of visitors in popular WHSs and hot spots of WHSs, and keep tourist congestion within an acceptable range, which is beneficial for tourists to better appreciate the charm of OUV, boost their levels of affection and loyalty, and reduce their negative emotions and threats to WHS protection. Fourth, strengthening the infrastructure construction of World Heritage tourism destinations and improving the overall quality of tourism services, especially in terms of the efficiency construction that affects tourist experience and satisfaction, needs to be further strengthened, such as the service literacy of personnel in WHS management institutions, the convenience of querying heritage site related information, and the popularisation experience for special groups. Fifth, the tourism development of WHSs should focus on the participation of different stakeholders, such as safeguarding the interests of local communities, fully utilising their community capital and promoting the healthy development of society, economy and ecology, which will be more favourable for advancing tourists’ experience quality and stimulating tourists’ willingness to protect WHSs.

Limitations and prospects

While this study has achieved relevant research results, some limitations should be considered. First, according to the S-O-R model, the relevant influencing factors have been defined; however, the constructed interpretation model could be further optimised. For example, the impact of the currently popular convergent media could be included in the stimulus factors, which play a crucial role in value promotion and attractiveness interpretation in WHSs. Second, the measurement of tourists’ perceptions of OUV attraction should be associated with the degree of visitors’ WHS education and the effectiveness of interpretations and exhibitions platform of destinations to more accurately and reasonably evaluate OUV and better construct a framework for measuring and interpreting OUV. Third, the assumption of place attachment for heritage protection was not supported herein. Future studies can further explore the role of tourists’ emotional states in the relationships among people and places for heritage protection from the perspectives of heritage attachment, heritage identity and heritage responsibility. Fourth, according to the S-O-R model, it is possible to test the behavioural intentions of various stakeholders, such as residents of heritage communities, tourism employees and heritage administrative staff; identify their commonalities and discriminators; reveal influencing determinants and mechanisms; and provide a theoretical basis for formulating heritage protection policies and plans. Fifth, the selected case study location is a scenic spot in Chinese Taoist culture; thus, the main concepts of respect for nature, conformity to nature and harmony between man and land in its Taoist thought have crucial influences on visitors’ value perceptions and WHS protection intentions. This study reveals the intention of heritage conservation and friendly environmental behaviour and compares it with the relevant research findings according to the Western cultural context, making the research conclusions more convincing and universal.

Conclusions

In accordance with the theoretical S-O-R model, this study explores the responses of stimulus factors (tourism involvement, OUV attentiveness and service quality) and organic transformation (perceived tourism value, place attachment and tourist satisfaction) to heritage conservation from the viewpoint of tourists’ perceptions and proposes a new model for protecting WHSs. First, stimulus factors such as tourism involvement, OUV attractiveness and service quality are found to have significant positive influences on tourist value perception, place attachment and tourist satisfaction; however, the assumption of OUV attraction to satisfaction is not supported. Second, tourists’ value perceptions and satisfaction levels in terms of organic transformation are found to positively influence heritage protection; however, the assumption of place attachment to heritage protection is not established. Third, the constructed framework of the impact mechanism of tourist heritage protection is found to not only have certain explanatory power but also further expand the academic research horizon of tourist management, heritage protection, value interpretation and sustainable development in WHSs; this finding suggests a novel viewpoint for the planning of tourist management, the participation of different stakeholders in heritage tourism and the study of heritage protection in the global-local context with certain theoretical value, especially by linking different cultural backgrounds and types of heritage tourism destinations, in order to more accurately and reasonably promote the protection of world heritage and the sustainable development of WHSs. Fourth, this study provides practical suggestions for protecting WHSs, improving tourists’ experience quality and managing visitors at these sites. These suggestions comprise a certain response by WHSs to the 5Cs of planned objectives (credibility, conservation, capacity-building, communication, communities), particularly with respect to site credibility, conservation and capacity building, as well as WHS protection and tourism management. The suggestions made herein have practical importance.

Data availability

Data are available on request due to privacy restrictions.

Abbreviations

- WHS:

-

World Heritage Site

- WHSs:

-

World Heritage Sites

- WNHS:

-

World Natural Heritage Site

- OUV:

-

Outstanding Universal Value

- MSNP:

-

Mount Sanqingshan National Park

- UNESCO:

-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- VBN:

-

Value-Belief-Norm

- TPB:

-

Theory of Planned Behaviour

- S-O-R:

-

stimulus-organism-response

- CNY:

-

Chinese Yuan

- KMO:

-

Kaiser Meyer Olkin

- AVE:

-

average variance extracted

- 5Cs:

-

credibility, conservation, capacity-building, communication, communities

References

UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (World Heritage Committee, 2012).

Yang, Y. et al. Tourism-enhancing effect of world heritage sites: panacea or placebo? A meta-analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 75, 29–41 (2019).

Formica, S. & Uysal, M. Destination attractiveness based on supply and demand evaluations: an analytical framework. J. Travel Res. 44, 418–430 (2006).

Zhang, C., Cheng, W. & Zhang, W. Does world heritage inscription promote regional tourism? Evidence from China. Tour. Econ. 29, 929–951 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Xiong, K. & Huang, D. Natural world heritage conservation and tourism: a review. Herit. Sci. 11, 15–55 (2023).

Albaladejo, I. P. & González-Martínez, M. Congestion affecting the dynamic of tourism demand: evidence from the most popular destinations in Spain. Curr. Issues Tour. 22, 1638–1652 (2017).

Papadopoulou, N. M., Ribeiro, M. A. & Prayag, G. Psychological determinants of tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: the influence of perceived overcrowding and overtourism. J. Travel Res. 12, 1–19 (2022).

Kempiak, J., Hollywood, L., Bolan, P. & McMahon-Beattie, U. The heritage tourist: an understanding of the visitor experience at heritage attractions. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 23, 375–392 (2017).

Jacobsen, J. K. S., Iversen, N. M. & Hem, L. E. Hotspot crowding and over-tourism: antecedents of destination attractiveness. Ann. Tour. Res. 76, 53–66 (2019).

Marques, C., Silva, R. V. D. & Antova, S. Image, satisfaction, destination and product post-visit behaviours: how do they relate in emerging destinations? Tour. Manag. 85, 104293 (2021).

Gao, Y., Fang, M., Nan, Y. & Su, W. World heritage site inscription and city tourism attractiveness on national holidays: new evidence with migration big data from China. Curr. Issues Tour. 26, 1956–1973 (2022).

Chiu, Y. H., Lee, W. & Chen, T. Environmentally responsible behaviour in ecotourism: antecedents and implications. Tour. Manag. 40, 321–329 (2014).

Nian, S., Li, D., Zhang, J., Lu, S. & Zhang, X. Stimulus-organism-response framework: is the perceived outstanding universal value attractiveness of tourists conducive to world heritage site conservation? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 1189 (2023).

Hazen, H. Valuing natural heritage: park visitors’ values related to world heritage sites in the USA. Curr. Issues Tour. 12, 165–181 (2009).

Su, Q. & Qian, S. Influence relationship and mechanism of tourists’ sense of place in world heritage sites: a case study of the classical gardens of Suzhou. Acta Geogr. Sin. 67, 1137–1148 (2012).

Zhang, X., Qiao, S., Yang, Y. & Zhang, Z. Exploring the impact of personalized management responses on tourists’ satisfaction: a topic matching perspective. Tour. Manag. 76, 103953 (2020).

Chen, J., Becken, S. & Stantic, B. Assessing destination satisfaction by social media: an innovative approach using importance-performance analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 93, 103371 (2022).

Williams, P. & Soutar, G. N. Value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions in an adventure tourism context. Ann. Tour. Res. 36, 413–438 (2009).

Chen, C., Leask, A. & Phou, S. Symbolic, experiential and functional consumptions of heritage tourism destinations: the case of Angkor world heritage site, Cambodia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 18, 602–611 (2016).

Gozzoli, P. C. & Gozzoli, R. B. Outstanding universal value and sustainability at Ban Chiang world heritage, Thailand. Herit. Soc. 14, 184–215 (2021).

Lew, A. A. A framework of tourist attraction research. Ann. Tour. Res. 14, 553–575 (1987).

Truong, T. L. H., Lenglet, F. & Mothe, C. Destination distinctiveness: concept, measurement, and impact on tourist satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 8, 214–231 (2018).

Tang, W., Zhang, J., Luo, H., Yang, X. & Li, D. The characteristics of natural scenery sightseers’ sense of place: a case study of Jiuzhaigou, Sichuan. Acta Geogr. Sin. 62, 599–608 (2007).

Dedeoğlu, B. B. Shaping tourists’ destination quality perception and loyalty through destination country image: the importance of involvement and perceived value. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 29, 105–117 (2019).

Xu, X., Chen, F. & Gursoy, D. Shopping destination brand equity and service quality. Tourism Rev. A-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2023-0597 (2024).

Palau-Saumell, R., Forgas-Coll, S., Sánchez-García, J. & Prats-Planagumà, L. Tourist behavior intentions and the moderator effect of knowledge of UNESCO world heritage sites. J. Travel Res. 52, 364–376 (2013).

Xue, N. I., Liu, X. S., Wan, L. C. & Hou, Y. Relaxing or challenging? How social crowding influences the effectiveness of activity-based destination advertising. Tour. Manag. 100, 1–11 (2024).

Zhang, C., Fyall, A. & Zheng, Y. Heritage and tourism conflict within world heritage sites in China: a longitudinal study. Curr. Issues Tour. 18, 110–136 (2015).

Crespi-Vallbona, M., Noguer-Juncà, E. & Coromina, L. The destination attachment cycle. The case of academic tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 21, 433–450 (2022).

Hu, H., Zhang, J., Wang, C., Yu, P. & Chu, G. What influences tourists’ intention to participate in the zero litter initiative in mountainous tourism areas: a case study of Huangshan national park, China. Sci. Total Environ. 657, 1127–1137 (2019).

Toudert, D. & Bringas-Rábago, N. L. Exploring the impact of destination attachment on the intentional behaviour of the US visitors familiarized with Baja California, Mexico. Curr. Issues Tour. 21, 805–820 (2018).

Qu, Y., Xu, F. & LYU, X. Motivational place attachment dimensions and the pro-environmental behaviour intention of mass tourists: a moderated mediation model. Curr. Issues Tour. 22, 197–217 (2019).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behav. Hum. 50(Dec), 179–211 (1991).

Stern, P. C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 56, 407–424 (2000).

Su, L. & Hsu, M. K. Service fairness, consumption emotions, satisfaction, and behavioural intentions: the experience of Chinese heritage tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 30, 786–805 (2013).

Fefer, J., De Urioste-Stone, S. M., Daigle, J. & Silka, L. Understanding the perceived effectiveness of applying the visitor experience and resource protection (verp) framework for recreation planning: a multi-case study in U.S. National parks. Qual. Rep. 23, 1561–1582 (2018).

Mehrabian, A. et al. An Approach to Environmental Psychology 30–66 (The MIT Press, 1974).

Qiu, H. et al. The effect of destination source credibility on tourist environmentally responsible behaviour: an application of stimulus-organism-response theory. J. Sustain Tour. 31, 1797–1817 (2022).

Lee, S., Ha, S. & Widdows, R. Consumer responses to high-technology products: product attributes, cognition, and emotions. J. Bus. Res 64, 1195–1200 (2011).

Slama, M. E. & Tashchian, A. Validating the s-o-r paradigm for consumer involvement with a convenience good. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 15, 36–45 (1987).

Han, M. S., Hampson, D. P., Wang, Y. & Wang, H. Consumer confidence and green purchase intention: an application of the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Retail. Consum Serv. 68, 103061 (2022).

Su, L. & Swanson, S. R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behaviour: compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tour. Manag. 60, 308–321 (2017).

Havitz, M. E. & Dimanche, F. Propositions for testing the involvement construct in recreational and tourism contexts. Leis. Sci. 12, 179–195 (1990).

Filo, K., Chen, N., King, C. & Funk, D. C. Sport tourists’ involvement with a destination: a stage-based examination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res 37, 100–124 (2011).

Hwang, S., Lee, C. & Chen, H. The relationship among tourists’ involvement, place attachment and interpretation satisfaction in Taiwan’s national parks. Tour. Manag. 26, 143–156 (2005).

Gursoy, D. & Gavcar, E. International leisure tourists’ involvement profile. Ann. Tour. Res. 30, 906–926 (2003).

Gu, Q., Qiu, H., King, B. E. & Huang, S. S. Understanding the wine tourism experience: the roles of facilitators, constraints, and involvement. J. Vacat. Mark. 26, 211–229 (2020).

Han, H. & Hyun, S. S. Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveller loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 70, 75–84 (2018).

Kim, H., Stepchenkova, S. & Babalou, V. Branding destination co-creatively: a case study of tourists’ involvement in the naming of a local attraction. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 28, 189–200 (2018).

Gao, J., Lin, S. S. & Zhang, C. Authenticity, involvement, and nostalgia: understanding visitor satisfaction with an adaptive reuse heritage site in urban China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 15, 100404 (2020).

Campos, A. C., Mendes, J., Valle, P. O. D. & Scott, N. Co-creating animal-based tourist experiences: attention, involvement and memorability. Tour. Manag. 63, 100–114 (2017).

Forgas-Coll, S., Palau-Saumell, R., Matute, J. & Tárrega, S. How do service quality, experiences and enduring involvement influence tourists’ behaviour? An empirical study in the Picasso and Miró museums in Barcelona. Int. J. Tour. Res. 19, 246–256 (2017).

Gross, M. J. & Brown, G. An empirical structural model of tourists and places: progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism. Tour. Manag. 29, 1141–1151 (2008).

Xu, S., Kim, H. J., Liang, M. & Ryu, K. Interrelationships between tourist involvement, tourist experience, and environmentally responsible behavior: a case study of Nansha wetland park, China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 35, 856–868 (2018).

Leask, A. Visitor attraction management: a critical review of research 2009–2014. Tour. Manag. 57, 334–361 (2016).

Hu, Y. et al. Measuring destination attractiveness: a contextual approach. Ann. Tour. Res 31, 25–34 (1993).

Baral, N., Hazen, H. & Thapa, B. Visitor perceptions of world heritage value at sagarmatha (mt. Everest) national park, Nepal. J. Sustain. Tour. 25, 1494–1512 (2017).

Canale, R. R., De Simone, E., Di Maio, A. & Parenti, B. UNESCO World Heritage sites and tourism attractiveness: the case of Italian provinces. Land Use Policy 85, 114–120 (2019).

Neuts, B. & Nijkamp, P. Tourist crowding perception and acceptability in cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 2133–2153 (2012).

Zehrer, A. & Raich, F. The impact of perceived crowding on customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 29, 88–98 (2016).

Luque-Gil, A. M., Gómez-Moreno, M. L. & Peláez-Fernández, M. A. Starting to enjoy nature in mediterranean mountains: crowding perception and satisfaction. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 25, 93–103 (2018).

Reitsamer, B. F., Brunner-Sperdin, A. & Stokburger-Sauer, N. E. Destination attractiveness and destination attachment: the mediating role of tourists’ attitude. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 19, 93–101 (2016).

Cheng, T., C. Wu, H. & Huang, L. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 21, 1166–1187 (2013).

Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S. & Uysal, M. Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. J. Travel Res. 52, 253–264 (2012).

Chang, S. & Stansbie, P. Commitment theory: do behaviors enhance the perceived attractiveness of tourism destinations? Tour. Rev. 73, 448–464 (2018).

Grönroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 18, 36–44 (1984).

Zeithaml, V. A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 52, 2–22 (1988).

Claes Fornell, M. D., Johnson, E. W., Anderson, J. C. & Bryant, B. E. The American customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings. J. Mark. 60, 7–18 (1996).

Brady, M. K. & Cronin, J. J. Jr. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: a hierarchical approach. J. Mark. 65, 34–49 (2001).

Dedeog Lu, B. B., Van Niekerk, M., Weinland, J. & Celuch, K. Re-conceptualizing customer-based destination brand equity. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 11, 211–230 (2019).

Abdou, A. H., Mohamed, S. A. K., Khalil, A. A. F., Albakhit, A. I. & Alarjani, A. J. N. Modeling the relationship between perceived service quality, tourist satisfaction, and tourists’ behavioural intentions amid covid-19 pandemic: evidence of yoga tourists’ perspectives. Front. Psychol. 13, 1003650 (2022).

Wu, H. & Li, T. A study of experiential quality, perceived value, heritage image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 41, 904–944 (2017).

Zhang, W. Heritqual: a study of heritage site service quality assessment scale. J. Beijing Int. Stud. Univ. 153, 17–23 (2008).

Su, H., Cheng, K. & Huang, H. Empirical study of destination loyalty and its antecedent: the perspective of place attachment. Serv. Ind. J. 31, 2721–2739 (2011).

Chen, C. & Chen, F. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 31, 29–35 (2010).

Damanik, J. & Yusuf, M. Effects of perceived value, expectation, visitor management, and visitor satisfaction on revisit intention to Borobudur temple, Indonesia. J. Herit. Tour. 17, 174–189 (2022).

Wen, J. & Huang, S. S. The effects of fashion lifestyle, perceived value of luxury consumption, and tourist–destination identification on visit intention: a study of Chinese cigar aficionados. J. Destin Mark. Manag. 22, 100664 (2021).

Zhang, L., Yang, S., Wang, D. & Ma, E. Perceived value of, and experience with, a world heritage site in china—the case of kaiping diaolou and villages in china. J. Herit. Tour. 17, 91–106 (2022).

Tuan, Y. Space and Place: the Perspective Of Experience. (University of Minnesota Press, 1977).

Williams, R. & Patterson, M. E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 14, 29–46 (1992).

Ramkissoon, H., Smith, L. D. G. & Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 21, 434–457 (2013).

Ujang, N. & Zakariya, K. The notion of place, place meaning and identity in urban regeneration. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 170, 709–717 (2015).

Cao, L., Qu, Y. & Yang, Q. The formation process of tourist attachment to a destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 38, 100828 (2021).

Lee, T. H. How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 19, 895–915 (2011).

Williams, D. R. & Vaske, J. J. The measurement of place attachment: validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 49, 830–840 (2003).

Woosnam, K. M. et al. Social determinants of place attachment at a world heritage site. Tour. Manag. 67, 139–146 (2018).

Qu, Y., Dong, Y. & Xiang, G. Attachment-triggered attributes and destination revisit. Ann. Tour. Res. 89, 103202 (2021).

Oliver, R. L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 63, 33–44 (1999).

Woo, E., Kim, H. & Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 50, 84–97 (2015).

Pizam, A., Neumann, Y. & Reichel, A. Dimensions of tourist satisfaction with a destination area. Ann. Tour. Res. 5, 314–322 (1978).

Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B. & Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 56, 41–54 (2017).

Beard, J. G. & Ragheb, M. G. Measuring leisure satisfaction. J. Leis. Res. 12, 20–33 (1980).

Sirgy, M. J., Kruger, P. S., Lee, D. & Yu, G. B. How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? J. Travel Res. 50, 261–275 (2011).

Wang, M. & Jia, Z. Investigating the correlation between building façade design elements and tourist satisfaction—cases study of Italy and the Netherlands. Habitat Int. 144, 103001 (2024).

Alrwajfah, M. M. et al. The satisfaction of local communities in world heritage site destinations. The case of the Petra region, Jordan. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 39, 100841 (2021).

Chen, C., Huang, W. & Petrick, J. F. Holiday recovery experiences, tourism satisfaction and life satisfaction–is there a relationship? Tour. Manag. 53, 140–147 (2016).

Lee, H. Measurement of visitors’ satisfaction with public zoos in Korea using importance-performance analysis. Tour. Manag. 47, 251–260 (2015).

Park, E., Choi, B. & Lee, T. J. The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 74, 99–109 (2019).

Marinao Artigas, E., Yrigoyen, C. C., Moraga, E. T. & Villalón, C. B. Determinants of trust towards tourist destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 6, 327–334 (2017).

Su, L., Hsu, M. K. & Boostrom, R. E. From recreation to responsibility: increasing environmentally responsible behavior in tourism. J. Bus. Res. 109, 557–573 (2020).

Neal, J. D. & Gursoy, D. A multifaceted analysis of tourism satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 47, 53–62 (2008).

Lee, T. H., Jan, F. & Yang, C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 36, 454–468 (2013).

Jaafar, M., Noor, S. M. & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: a case study of the Lenggong world cultural heritage site. Tour. Manag. 48, 154–163 (2015).

Leiper, N. Tourist attraction systems. Ann. Tour. Res. 17, 367–384 (1990).

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A. & Berry, L. L. Servqual: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 69, 12–40 (1988).

Sweeney, J. C. & Soutar, G. N. Consumer perceived value: the development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 77, 203–220 (2001).

Kyle, G. T., Mowen, A. J. & Tarrant, M. Linking place preferences with place meaning: an examination of the relationship between place motivation and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 24, 439–454 (2004).

Lewicka, M. Place attachment: how far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 31, 207–230 (2011).

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J. & Hughes, K. Environmental awareness, interests and motives of botanic gardens visitors: implications for interpretive practice. Tour. Manag. 29, 439–444 (2008).

Bagozzi, R. & Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94 (1988).

Ping, R. A. What is the average variance extracted for a latent variable interaction (or quadratic)? http://home.att.net/~rpingjr/ave1.doc (2005).

Tosun, C. Host perceptions of impacts: a comparative tourism study. Ann. Tour. Res 29, 231–253 (2002).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. & William, C. Black, Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings 6th edn (Prentice-Hall, 2002).

Mulaik, S. There is a place for approximate fit in structural equation modelling. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 42, 883–891 (2007).