Abstract

The Great Wall is currently facing a significant amount of erosion damage that are rapidly causing its decay and destruction. Among these, erosion damage caused by saltwater intrusion, are the most devastating, as they undermine the foundation of the wall, leading to rapid collapse and disappearance. This study utilizes low-altitude oblique photography technology with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to construct a digital method route for rapid survey and precise quantification of the damage. We conducted a comprehensive survey of erosion damage along the Ming Great Wall in Gansu, China. A three-dimensional point cloud model was utilized to quantitatively assess the morphological characteristics of the erosion damage. Additionally, the distribution patterns of saline erosion were examined through a combination of field sampling and physicochemical experimental analysis. Our findings indicate that the spatial distribution of erosion damage exhibits an aggregative characteristic and is closely related to natural geographical elements. There are regional differences in the morphological characteristics of erosion, with high concentrations of erosion height and depth data in different sections. The degree of saltwater intrusion and the distribution of soluble salt content vary in different parts of the wall, showing a regular pattern of higher levels on the south side, decreasing from bottom to top. The paper conducts a basic survey of the spatial distribution and patterns of erosion damage, which decrease from a macroscopic distribution to key sections, and produces a risk map of erosion damage based on the survey results, providing reference and scientific support for the protection and restoration of the Great Wall.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

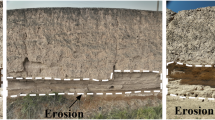

The Great Wall, the largest linear heritage in China, has received widespread attention from the international community since it was inscribed as a World Cultural Heritage site in 1987. Over time, the Great Wall has been experiencing a process of rapid decay and destruction due to human activities and changes in the surrounding natural environment. During the construction of the Great Wall, the selection of wall materials and construction methods were determined based on the local natural environment, material availability, and topography. The main wall materials include earth, bricks, and stones1 (Fig. 1). Among the various construction materials, rammed earth walls are mainly found in the northwest region of China, with a large distribution range accounting for over half of the total length of the Ming Great Wall. The construction method involves sieving natural soil, which includes mixed sand and other substances, to obtain cohesive pure clay. Wooden templates are then fixed along the direction of the wall using ropes, and the clay is filled into the molds and compacted to form the wall. At the same time, rammed earth walls are highly vulnerable to erosion from wind, water, salt, and freeze-thaw cycles due to the fragility of their construction materials. Therefore, urgent protection measures are needed2.

Currently, research on the damage of the Great Wall mainly focuses on studying the types3 and characteristics of erosion and exploring the mechanisms behind them4. Rammed earth walls are exposed to various environmental conditions throughout the year, including erosion from sandstorms in spring and autumn, damage from heavy rainfall and high-temperature radiation in summer, and the impact of low temperatures and snow accumulation in winter. As a result, severe damage such as flaking, alkali erosion, cracks, and erosion occur in many sections of the Great Wall5,6. Among the various damage that affect rammed earth walls, erosion at the bottom of the wall is the most destructive type, as it leads to the formation of large voids at the base of the wall, reducing its overall resistance to overturning and resulting in instability and large-scale collapse of the wall. According to relevant studies on erosion mechanisms, salinity erosion is the main cause of erosion damage7,8. As rammed earth walls are mostly distributed in arid and semi-arid regions, under conditions of low rainfall and rapid evaporation, salt accumulates rapidly at the base of the walls, forming a salt-affected zone. The repeated salt expansion in the salt-affected zone damages the structure and strength of the rammed earth, leading to the development of erosion damage9. Scholars have conducted simulation experiments to study the distribution and migration of soluble salts in rammed earth specimens10, revealing that soluble salts continuously migrate towards the surface of the rammed earth with the movement of water, eventually accumulating on the soil surface. This micro-level observation sheds light on the coupled degradation mechanism of moisture-salt in rammed earth heritage sites11,12,13. Based on the comprehensive image monitoring of the Ming Great Wall in Gansu, China, conducted by the research team from 2019 to 2024, a comparison of photographs taken from the same location before and after five years (Fig. 2) clearly shows that the Great Wall is collapsing and disappearing at an alarming rate. Therefore, urgent measures are needed for the protection of the Great Wall. At the same time, conducting a survey on the distribution patterns of damage is a fundamental task for the protection of the Great Wall. Through this survey, the distribution patterns and characteristics of erosion can be clarified, providing a scientific basis for the protection and restoration of the Great Wall.

Existing research has covered various types of erosion in rammed earth sites and proposed a relatively mature classification system for these damage. The exploration of erosion damage mechanisms has provided important insights for this paper. However, there are still some gaps in the investigation of erosion spatial distribution and patterns.

Firstly, there is a lack of comprehensive surveys on the distribution of damage along the entire length of the Great Wall, and the current understanding of erosion distribution is still unclear. Although the Chinese government initiated a large-scale survey of the Great Wall resources in 2007, the depth of the survey was limited to the spatial distribution of resource points, photographic records of appearances, and drawings of plans and elevations, which do not involve the types of wall damage and the distribution of the erosion. Each kilometer of the Great Wall only takes 15 photos of the current situation, which is difficult to clearly express the preservation status of the heritage. The lack of targeted investigation of damage makes the cultural relics protection units lack of overall control of the current situation of the Great Wall erosion, and the macro-level distribution map of damage is still missing, making it difficult to allocate limited resources for protection and restoration in an optimized manner.

Secondly, there is a lack of quantitative assessment and classification of erosion damage characteristics. Previous studies have attempted to establish erosion assessment systems. For example, Yao Xue et al.14 introduced the gray correlation degree analysis method to assess the degree of damage and risk of rammed earth sites in Shaanxi. Kai Cui et al.15 used the Fuzzy-AHP method to establish an assessment system for erosion and peeling of rammed earth sites, and calculated the development degree of erosion and peeling16. However, due to the lack of accurate three-dimensional model data describing the current state of the sites, it is difficult to accurately quantify and analyze the extent of erosion. For example, the paper mentions that the erosion height of the Qinghai section of the Great Wall is concentrated between 550–1000 cm17,18, but it is unclear which section of the wall has the highest erosion height and the specific erosion amount in different sections. Additionally, the paper simplifies the description of erosion morphology by categorizing it into three ideal types: arch-shaped column, rectangular column, and semi-arch-shaped column. However, this simplified description is not accurate enough and still belongs to a semi-quantitative analysis19. In 2013, China issued the “Technical Regulations for Damage Assessment of Movable Cultural Relics—Porcelain Relics (WW/T 0056—2014),” which provided basic standards for the scientific analysis and assessment of the preservation condition of movable cultural relics. However, there are no relevant national regulations for the quantitative assessment and classification of damage in immovable cultural relics. Therefore, conducting a quantitative statistical analysis of disease conditions through physical surveys and the quantification of the hole erosion situation by using the indicators of morphological characteristics can provide methodological support and reference for the evaluation of immovable cultural relics, and help promote the development of assessment standards for damage in large-scale linear heritage sites.

Thirdly, there is a lack of analysis and exploration of the micro-level distribution patterns of salt erosion. Existing studies have focused on individual samples and have limited data20. Laboratory simulation experiments have laid the foundation for understanding the mechanisms of salinity erosion21. However, due to the different orientations of the Great Wall, the deterioration of the wall surface is different in different orientations and angles, and most of the existing studies have used the indoor sample testing method to explore the difference law of erosion deterioration, but it is difficult to achieve the accurate description of the real environmental situation of erosion deterioration by the single-factor analysis in the ideal conditions. Therefore, there is an urgent need to carry out the erosion investigation of the Great Wall in the field, to corroborate the deterioration of the Great Wall in the real scene with the cause mechanism of the erosion, to grasp the distribution law of the deterioration and erosion state, to explore the correlation between patterns and natural geographical factors such as orientation and temperature, and summarize the spatial regularities of salt erosion.

In recent years, the use of digital technology for surveying and recording cultural heritage has become an international trend. From 2002 to 2009, the Hadrian’s Wall project conducted comprehensive mapping, verification, and compilation of over 3000 records of the wall and its buffer zone. In 2009, the English Heritage Commission implemented an annual aerial survey project to search for, record, and monitor heritage sites. New technologies such as “laser scanning,” “motion structure digital photogrammetry,” and “field digital acquisition systems” are increasingly being used in heritage protection and monitoring. However, the Great Wall in China has a wide coverage, with a total length of 8851.8 kilometers for the Ming Great Wall alone, spanning 156 counties in ten provinces (districts, municipalities) including Liaoning, Hebei, Tianjin, Beijing, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai. The heritage sites and remaining facilities are numerous. Therefore, conducting a comprehensive survey of damage along the Great Wall is challenging, and traditional methods of cultural heritage investigation are unable to achieve full coverage of data along the entire length. Finding an efficient and rapid method for damage surveys is a current challenge. Low-altitude aerial photogrammetry with UAV has advantages such as high surveying accuracy, fast speed, and wide coverage, which brings new technological methods for collecting basic information on Great Wall damage. The use of UAV can adapt to the large scale, complex morphology, and difficult accessibility of cultural heritage mapping, as well as withstand various complex field environments such as mountains, valleys, hills, and deserts. It can accomplish tasks that are difficult for traditional human methods, greatly advancing the digital protection of cultural heritage. Scholars have already used low-altitude aerial photogrammetry with UAV for data collection and 3D modeling of various heritage sites, such as the ancient city of Pompeii22 in Italy, Roman Forum in Benevento23, Wat Maha That, Thailand24, Cahokia’s Grand Plaza25, and so on. However, compared to the scale of the Great Wall, there has been no research on such a large-scale linear heritage site, and the data accuracy of existing studies is insufficient to meet the fine requirements of damage investigation.

Therefore, this paper utilizes UAV low-altitude aerial photogrammetry technology to establish a digital method route for rapid survey and precise quantification of erosion damage. The paper investigates the distribution of salinity erosion damage in the entire Gansu Province, China and summarizes the relevant patterns. The research includes the following contents:

(1) Comprehensive survey of salinity erosion damage spatial distribution along the entire Great Wall. The spatial distribution of salinity erosion damage is captured through the survey, and geographical spatial analysis methods are used to analyze the spatial clustering degree and distribution types of salinity erosion damage. The paper explores the coupling relationship between erosion distribution and factors such as elevation, land use types, and soil types, in order to achieve an overall and comprehensive understanding of salinity erosion damage in Gansu.

(2) Quantitative analysis of salinity erosion damage morphology in typical sections. High-precision 3D point cloud models are used to quantify the degradation level of salinity erosion damage in typical sections through the fitting of morphological features. Four indicators, including erosion height, erosion depth, erosion area, and morphology erosion rate, are used for comparative analysis in different sections. Through a quantitative analysis, the paper aims to assess and classify the erosion conditions of the Great Wall in individual sections.

(3) Exploration of micro-scale distribution patterns of salinity erosion. By sampling and testing the earth wall, the paper analyzes the soluble salt content, soluble salt ion composition, and mineral composition of the soil samples to investigate the distribution patterns of salts in the wall. This includes the distribution patterns of soluble salt content on the north and south sides of the wall and the variation of soluble salt content from the bottom eroded area to the top of the wall, providing insights into the degradation mechanism of salinity erosion damage.

Through a digital survey of erosion damage, the paper comprehensively grasps the spatial distribution of erosion damage. It also creates spatial distribution maps and damage risk warning maps specifically for salinity erosion damage for the first time. The paper combines morphological feature quantification and analysis of salinity erosion patterns to establish a foundational data base for “damage diagnosis” and provide a scientific reference, with an aim to further promote the development of preservation and repair work for immovable cultural heritage.

Methods and materials

Study area

The research area of this study is Gansu Province, China, focusing on the wall of the Ming Great Wall (Fig. 3). Gansu is located in the northwest of China and has a complex and diverse topography, mainly consisting of deserts and semi-deserts. It has a climate characterized by scarce and unevenly distributed precipitation, with low rainfall, strong winds, and high evaporation. The unique geographical location and environmental conditions of Gansu have a significant impact on the development of damage of the Ming Great Wall, making the study of salinity erosion erosion characteristics in this region more typical and representative. The Ming Great Wall in Gansu stretches for 1738 kilometers, ranking first in length among all sections of the Great Wall in China. The wall is mainly constructed with rammed earth, and the preservation condition of the heritage resources is good, with minimal disturbance from human-induced factors. This provides a natural case and a realistic basis for studying salinity erosion damage.

Methodology

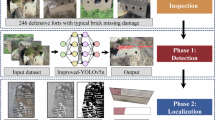

The study utilizes UAV low-altitude aerial photogrammetry technology to investigate salinity erosion damage in Gansu. It involves three main steps: (1) Field survey for obtaining basic damage data. UAV low-altitude aerial photogrammetry is used to capture images of the damage and generate 3D point cloud models. This enables a physical survey of damage along the entire length of the Great Wall in Gansu and the establishment of a basic damage database. (2) Quantitative analysis of the spatial distribution and morphological characteristics of damage. ArcGIS spatial analysis is employed to analyze the macro-level spatial distribution patterns of damage. Morphological features in typical sections are fitted and quantified using four indicators: erosion height, erosion depth, erosion area, and morphology erosion rate. This quantitative analysis allows for the assessment and classification of damage morphology in specific sections. (3) Sampling and experimental analysis. Soil samples are collected from the rammed earth walls for testing the soluble salt content, soluble salt ion composition, and mineral composition. This micro-level analysis reveals the distribution patterns of salts in the walls and contributes to understanding the mechanisms of salinity erosion. The specific research framework is shown in Fig. 4.

Stage I Field survey: Utilizing UAV to capture images and generate three-dimensional point cloud models along the entire length of the Great Wall in Gansu

The study utilizes UAV low-altitude aerial photogrammetry to investigate the salt erosion damage situation in Gansu. Firstly, a DJI Mavic 3E UAV (with an effective pixel of 20 million, a field of view of 84°, an equivalent focal length of 24 mm, and an aperture of f/2.8-f/11) is used to conduct ultra-low-altitude and slow-speed flights (at a speed of 2-4 m/s) along the Great Wall in Gansu. The UAV captures images from the inside, outside, and top of the wall along five flight lines at relative heights of 10 m and 15 m (Fig. 5a). Continuous high-definition image sets with a minimum overlap rate of 70% between adjacent images within the same flight line are obtained. The UAV’s real-time kinematic (RTK) technology is used to achieve centimeter-level high-precision positioning in the WGS84 coordinate system. Secondly, Using Web of Geographic Information System (Web GIS) for database platform management of collected data and image retrieval function, which facilitates image screening of key sections of the damage (Fig. 5b). In this paper, we employed a manual identification assessment screening method conducted by five experts to evaluate typical erosion damage segments. The selection was based on the following criteria: continuous hollowing exceeding one kilometer, minimal anthropogenic interference from residential areas, and wall integrity greater than three-quarters for each segment. Furthermore, the expert evaluation results were confirmed in collaboration with local heritage protection agencies to ensure the accuracy of the segment selection. Ultimately, 58 typical segments were selected, representing 85 percent of the validated results., Thirdly, conducting close-range photogrammetry in selected key sections (Fig. 5c). To minimize the influence of the wall’s curved and uneven surface, multiple flight lines at different heights are used. The UAV flies close to the wall within a distance of 2 m, starting from one end of the sampling area and flying along the wall direction. After completing one horizontal flight line, the UAV moves laterally to the side at a fixed distance to adjust the height and continues flying, meeting the requirement of an 80% overlap rate. This process is repeated until all sampling areas are covered, ensuring high data accuracy and capturing the details of erosion on the wall’s surface. Finally, a three-dimensional point cloud model is generated (Fig. 5d). The photos captured by the UAV are imported into DJI Terra software for three-dimensional reconstruction, including aerial triangulation, dense matching, and model reconstruction. This process ultimately produces a centimeter-level high-precision digital three-dimensional model of the measured wall. Through the field survey steps mentioned above, the study collected 26,000 photos, covering 1350 kilometers of existing rammed earth walls in Gansu, with a data volume of 4.1TB. This achieved a comprehensive digital survey of damage covering the entire Gansu region.

Stage II Quantitative Analysis: Geospatial Analysis and Morphological Feature Quantification

(1) ArcGIS Geospatial Analysis

ArcGIS 10.8 was used to conduct geospatial analysis on the macro-distribution of erosion damage. This includes kernel density analysis and average nearest neighbor analysis to analyze the spatial clustering and distribution types of erosion damage. From a macro perspective, the spatial distribution characteristics and patterns of the damage are summarized.

Kernel density estimation26 uses spatial smoothing techniques to process discrete point data. It estimates the density of points in the neighborhood of a given point within a unit spatial range and fits it into a smooth surface. Higher kernel density values indicate a more concentrated spatial distribution of the erosion27. Gaussian kernel function was used for the analysis, with a search radius set at 1 kilometer. The formula is as follows:

In Eq. (1), f(x) represents the estimated probability density at point x; n is the number of damage sample points; h is the bandwidth parameter, set at 1 kilometer in this case; xi represents the coordinates of the sample points.

Average nearest neighbor analysis (ANN) compares the average distance between the centers of damage sample points and their nearest neighbors with the expected average distance under the assumption of random distribution. The ratio between the two, known as the average nearest neighbor ratio (Rn), is used to determine whether the spatial distribution of the erosion is random or clustered28,29. The formula is as follows:

In Eq. (2), \(\overline{{{\rm{D}}}_{{\rm{o}}}}\) represents the average distance between damage sample points and their nearest neighbors; \({\bar{{\rm{D}}}}_{{\rm{E}}}\) represents the average distance under random distribution; represents the distance between damage sample point i and its nearest neighbor; n is the number of damage points, and A is the area of the study region. If Rn < 1, the damage distribution is considered clustered; if Rn > 1, the distribution tends to be dispersed.

(2) Morphological Feature Fitting of Key Sections

Based on a digital survey covering the entire Gansu, combined with the screening results of typical segments assessed by experts, 10 typical key sections of erosion damage were selected for morphological feature quantification analysis. Among them, 8 sections have an east-west orientation, while 2 sections have a north-south orientation (Fig. 3, Table 1). The main quantification methods are as follows: First, a high-precision 3D point cloud model of the typical sections was established using UAV close-range photogrammetry (Fig. 6a). Second, the 3D model was longitudinally sliced at intervals of 5-10 meters, based on the length of each section, to generate longitudinal profiles of the walls and extract their contour lines (Fig. 6b). Third, incomplete profiles that intersect with beacon towers, collapsed walls, tree obstructions, or accumulated debris at the bottom were filtered and removed. Fourth, the contour lines of the profiles were completed. The height of the walls was determined based on the position of the surviving parapets and the top of the continuous main walls. The wall inclination angle and width were determined based on the intact upper portion of the walls. This process resulted in the fitting of the existing walls to form complete ideal walls, with the eroded areas at the bottom marked with shadows (Fig. 6c). After these steps, a total of 183 valid profiles were obtained for the 10 sections.

The selection of indicators of morphological characteristics of erosion damage mainly combines the location of damage development and the profile characteristics of the section, including four indicators: height of hollowing, depth of hollowing, area of hollowing, and rate of morphological hollowing. The development of erosion damage generally starts from the bottom, and the deterioration of the bottom is serious, while the upper part is less likely to have the development of erosion30. Therefore, the hollowing height and depth directly reflect the erosion degree from the bottom of the wall to the upper part of the wall, which can intuitively reveal the difference between the profiles of different sections31; the hollowing area can intuitively quantify the surface concavity of the wall after salt erosion, which is an index after the joint synthesis of the hollowing height and depth; the hollowing rate is the ratio of the hollowed out area to the total wall profiled area in the single profile, which is the ratio of the hollowing area to the total wall profiled area in the wall profile, due to different wall dimensions in various sections, which is a good indicator for the development of the wall. Since the wall dimensions of each section are different, the hollowing rate index can express the erosion damage of the wall in that section more reasonably15. Based on the above indicators, the erosion of typical sections was quantitatively assessed and graded, and the specific quantification indicators and formulas are shown in Table 2.

Stage III Sampling and Experimental Analysis of Typical Sections

Soil sampling and experimental testing were conducted on the rammed earth walls of the aforementioned ten typical sections. The sampling points for each section are shown in Fig. 7. The main sampling points include the bottom of the eroded area on both sides of the wall, at one-third of the height from the ground, and at two-thirds of the height from the ground. The content of the experimental analysis mainly includes the soluble salt content, the detection of soluble salt ion components, and mineral composition analysis of the soil samples to explore the distribution patterns of salts in the walls and the degradation mechanisms of salinity erosion.

(1) Determination of soil salinity: Electrical conductivity

Based on the principle of electrical conductivity in salinity soil solutions32,33, a LD soil salinity meter (model YP-WSY) was used to determine the salt content in the site soil by testing the electrical conductivity of the soil-water mixed solution. A 25 g dried soil sample was dissolved in 100 ml of pure water and stirred vigorously for 5 min. After the solution stabilized, the electrical conductivity was tested three times and averaged. The formula is as follows:

In Eq. (3), total Dissolved Solids (TDS) refers to the concentration of soluble salts in the soil leachate, measured in mg/L;K is the calibration coefficient, with a value of 0.55 based on instrument specifications; Electrical Conductivity (EC) represents the conductivity of the soil leachate, measured in µS/cm.

(2) Determination of soil salt ions: Ion Chromatography

The ion chromatographic (IC) method34 was used to detect the cation and anion components of soluble salts in the soil samples. In the laboratory, the dried soil samples were soaked in deionized water at a water-to-soil ratio of 10:1 and agitated on an ultrasonic oscillator for 40 minutes. The supernatant was filtered using a syringe filter (pore size 0.22 µm) and analyzed using a Dionex ion chromatograph (ICS-2000, USA). The formula is as follows:

In Eq. (4), Q represents the ion content in the soil, in mg/g; C is the ion content of the sample measured with 50 mL of deionized water, in mg; G is the mass of the rammed earth wall sample collected from the site, in g.

(3) Determination of salt crystals: X-ray Diffraction

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)35 was used to analyze the mineral composition and content of the soil in the eroded area at the bottom of the rammed earth site. The soil sample was ground to a particle size of 320 mesh (approximately 40 µm) and analyzed using the SmartLab-9kW X-ray diffractometer from Rigaku, Japan. The experimental conditions included a Cu target (λ = 0.15406 nm), a Ni filter, a tube voltage of 40 kV, a tube current of 100 mA, continuous scanning, with the angle range of 3-70° (2θ), a step size of 0.02° (2θ), and a scan speed of 8°/min.

Data collection

The Great Wall resource data is based on the survey and statistical results of the Great Wall resources by the Chinese National Cultural Heritage Administration (http://www.greatwallheritage.com, accessed on May 20, 2024). The research mainly relies on the self-built “Ming Great Wall Image and Realistic 3D Database” by the research team, which is based on continuous low-altitude UAV surveys to obtain centimeter-level images and 3D point cloud data. The basic geographic information data includes Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data from the Geographic Spatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn/search, accessed on April 24, 2024), with an accuracy of 30 m; land use data from the National Cryosphere Desert Data Centre (http://www.ncdc.ac.cn, accessed on March 25, 2024), with an accuracy of 10 m; and soil type data from the Nanjing Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://vdb3.soil.csdb.cn, accessed on May 20, 2024), with an accuracy of 1 km36.

Results

Spatial distribution characteristics of erosion damage

Based on the UAV low-altitude photogrammetry survey of erosion damage in Gansu Province, point features were used to mark the sections of the Great Wall with salinity erosion damage. The marking principle mainly corresponds to the division of different sections of the wall in the survey of Great Wall heritage resources. Since some sections have continuous erosion damage, for every additional 1 km of continuous erosion length, an additional marking point was added. The investigation results of erosion damage in Gansu Province are shown in Fig. 8.

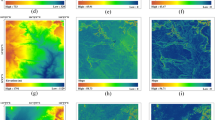

The kernel density analysis tool in ArcGIS was used to analyze the damage points. According to the results shown in Fig. 9a, the overall distribution of erosion erosion in the study area exhibits a “dispersed large-scale, clustered small-scale” spatial pattern. Most erosion are concentrated in several core areas, while the vast areas between the core areas have scattered erosion points. By overlaying the kernel density analysis results with the administrative divisions of counties and cities in Gansu Province, it can be observed that the erosion damage are concentrated in Shandan County and Gaotai County in Zhangye City, Yongchang County in Jinchang City, Liangzhou District and Gulang County in Wuwei City, Changcheng District in Jiayuguan City, and Suzhou District in Jiuquan City. Among them, Shandan County has the highest number of erosion points, the most dense distribution, and the most typical damage characteristics. The average nearest neighbor tool was used to analyze the spatial distribution type of the erosion, and the calculated average distance between erosion sample points and their nearest neighbors was 6978.960 m, with an expected average distance of 15931.750 m. The average nearest neighbor ratio (Rn) was 0.438. Since Rn<1 and the z-value was -21.285, it indicates that the damage sample points in the study area are clustered within a certain range. Therefore, the spatial distribution type of erosion damage in Gansu Province is considered to be clustered.

The spatial distribution characteristics of erosion damage are the result of the combined effects of multiple factors. In the following analysis, the damage distribution points were overlaid with raster data in ArcGIS, focusing on elevation, land use types, and soil types, to explore the coupling relationship between erosion distribution and different factors. According to the results shown in Fig. 9b, the elevation range of erosion distribution is between 1301.75 m and 2592.5 m, with 83.8% of erosion points distributed at an altitude above 1500 m, indicating a high-altitude distribution. Using the raster calculator, the land use type of the erosion points was calculated. According to the results shown in Fig. 9c, 67.5% of the erosion points are located in farmland, and 21.3% are in Rangeland. When overlaying the erosion points with soil type data, the results shown in Fig. 9d indicate that 57.1% of the erosion points are located in salinity soils, including inland salinity soils, salinized desert soils, salinized meadow soils, alkalized desert soils, and alkalized salinity soils. 19.7% of the soils are calcareous soils, rich in lime and calcium carbonate, and 17.9% are oasis gray soils, rich in minerals such as feldspar, pyroxene, and biotite. In summary, the distribution characteristics of erosion damage are closely related to natural geographic factors, mainly occurring in high-altitude areas, with a predominance of farmland and bare land, and the soils in these areas are often affected by salinization.

Quantitative analysis of erosion damage morphology

The study used the quantitative methods for erosion damage morphology described in section 2.2.2 to quantify four indicators: erosion height, erosion depth, erosion area, and morphological erosion rate for 10 typical sections. The extracted profile samples for each section are shown in Fig. 10, with Fig. 10a are presenting an east-west orientation and Fig. 10b representing a north-south orientation of the Great Wall. The statistical results of the quantified indicators are shown in Fig. 11.

a erosion height, Erosion Height / m. Sample of a typical section. b erosion depth, Erosion depth / m. Sample of a typical section. c erosion-eliminated area, Erosion-eliminated area / m2. Sample of a typical section. d morphological erosion. Morphological erosion rate / %. Sample of a typical section.

Overall, there are significant differences in the various erosion indicators among the sample areas. Based on the length of the boxplots in Fig. 11, the data for erosion height and depth are relatively concentrated for different sections, while the data for erosion area and morphological erosion rate are more dispersed, indicating that the area and rate of erosion are influenced by other factors, resulting in significant differences in the data. The symmetry between the upper and lower halves of the boxplots for the four indicators is poor, indicating uneven distribution of the data with fluctuations within a certain range. The differences in erosion characteristics between east-west and north-south oriented sections of the Great Wall are not significant, except for the noticeable lower erosion height in the north-south oriented sections. The orientation of the wall has no significant impact on the erosion volume in the other indicators.

According to the quantification results for erosion height shown in Fig. 11a, the data samples with erosion heights ranging from 1.14 m to 1.42 m have the highest frequency. Among the ten samples, the ESLB section has the highest average erosion height, followed by SLB, while the two north-south oriented sections (CF and HYH) have smaller average erosion heights, with CF having the smallest average erosion height. The maximum erosion height among the samples is 1.78 m, and the minimum is 0.34 m. Based on the results shown in Fig. 11b, some samples such as SH and FCB exhibit a wide distribution, indicating a large range of erosion depths, while QSB and CF have more concentrated erosion depths, indicating less external disturbances in those sections. In terms of specific values, LB has the highest average erosion depth at 0.64 m, while JA, HYH, ESLB, and QSB have similar erosion depths ranging from 0.4 m to 0.45 m, and FCB and CF have the smallest erosion depths at 0.22 m. According to the results shown in Fig. 11 c, the erosion area of each sample exhibits significant variability. The SLB sample has the largest average erosion area at 1.21 square meters, while QSB and JA have the smallest areas at 0.35 and 0.29 square meters, respectively. The erosion areas of the ESLB and CF samples are similar at 0.49 square meters. Figure 11d shows the morphological erosion rate for different sections. The SLB sample has the highest morphological erosion rate at 12.83%, while the LFZ sample has the lowest rate at only 2.05%. The high morphological erosion rates of SLB and ESLB, which are geographically adjacent, indicate a significant impact of similar natural environments on the erosion process in that region.

In conclusion, the different ranges of the four indicators among the samples indicate regional differences in erosion characteristics. The distribution and range of erosion area and erosion rate indicate variations in erosion intensity and characteristics due to disturbances from other factors such as topography and climate. Quantitative analysis of erosion morphology in different sections allows for statistical assessment of erosion conditions and understanding of the characteristics of erosion in each section, laying the foundation for grading assessment of the diseases. Based on the magnitude of the erosion rate, the risk levels of the ten sample sections can be evaluated, with higher erosion rates indicating a greater likelihood of overall collapse due to erosion diseases, resulting in higher risks. The risk levels from high to low are: SLB > ESLB > SH > HYH > CX > JA > QSB > CF > FCB > LFZ.

Distribution pattern of salinity erosion

The occurrence of erosion damage is mainly due to the rapid accumulation of salts at the root of the site under conditions of low rainfall and rapid evaporation37. To investigate the spatial distribution pattern of salinity erosion in erosion damage, soil samples were taken from rammed earth walls, and the soluble salt content was measured using the conductivity method to reveal the distribution pattern of salts during the formation and development of erosion damage and the process of salinity erosion deterioration.

Figure 12 illustrates the differences in soluble salt content due to different orientations of the erosion areas. The soluble salt content in the erosion areas at the bottom of six typical sections was measured, with the first four sections oriented east-west and the last two sections oriented north-south. According to the results shown in Fig. 12a–d, the soluble salt content in the southern erosion areas of the four east-west oriented sections is higher than that in the northern areas. The highest value in the southern areas is 3324.2 mg/L, significantly higher than the highest value of 653.95 mg/L in the northern areas in the CX, while the lowest value in the northern areas is 2024 mg/L, significantly higher than the lowest value of 653.95 mg/L in the southern areas in the CX. Particularly in the CX, ESLB, and SH sections, the salt content in the southern erosion areas is generally 3-5 times higher than that in the northern areas and can even be up to 10 times higher. In the CF and HYH sections, which are oriented north-south, as shown in Fig. 12e, f, the differences in soluble salt content between the western and eastern sides of the walls are small, with alternating values and no apparent regularity. Figure 13 compares the range, central tendency, and dispersion of salt content in the erosion areas of the east-west and north-south orientations using boxplots. The results show that the soil salt content in the southern and northern erosion areas is concentrated, and the horizontal lines of the boxplots are relatively symmetrical, indicating a relatively even distribution of the data. At the same time, the mean and quartiles of the data in the southern erosion areas are higher than those in the northern areas, indicating generally higher soil salt content in the southern areas. The data for the erosion areas on the eastern and western sides of the walls have more outliers, and the height of the box is larger, indicating a wider range of soil salt content and greater variability. In summary, the orientation of the erosion areas affects the spatial distribution of soluble salt content, with the southern side of the walls having significantly higher salt content than the northern side, while the differences in salt content between the eastern and western sides are small.

Figure 14 presents the soluble salt content and its variation along individual wall profiles from the bottom erosion area to the top of the wall. The results show that in the eight key sections, the soluble salt content is highest in the bottom erosion area, followed by the area one-third from the ground, and lowest in the area two-thirds from the ground, indicating a gradual decrease in soluble salt content from the bottom to the top of the wall. This pattern is similar on both the southern and northern sides of the walls. In terms of specific values, the soluble salt content in the bottom erosion area is 7-10 times higher than that one-third from the ground, especially in the ESLB section, where the salt content in the bottom erosion area is 26.8 times higher than that at the top of the wall, indicating a sharp decrease in soluble salt content from the erosion area to the top. While the soluble salt content in the area two-thirds from the ground generally decreases compared to that one-third from the ground, the change is not drastic, usually ranging from 3–5 times, with the largest difference observed in the LFZ section, where it is 6.7 times. In summary, in each section of the Great Wall, soluble salts are unevenly distributed within the walls, mainly concentrated at the roots of the walls, with the highest soluble salt content in the bottom erosion area and a gradual decrease in content as you move up the wall.

Experimental testing was conducted on the soil soluble salt content, anion and cation composition, and mineral composition of the bottom erosion area of the SH section of the Great Wall using ion chromatography (IC) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The results showed that the main anions in the soluble salts were SO42- and Cl-, with a small amount of HCO3-. Among them, the SO42- content was the highest, three times higher than the Cl-. The main cations in the soluble salts were Na+ and Ca2+, followed by K+, with Na+ having the highest content, 25 times higher than Ca2+. The XRD results and the content of the main mineral components of the soil samples are shown in Fig. 15. he main components of the soil samples were quartz, which had good stability, and clay minerals such as illite, clinochlore, calcite, and kaolinite. Illite and kaolinite have strong water absorption properties and expand significantly when in contact with moisture. In addition, the soil samples contained certain amounts of Na2SO4 and NaCl, indicating that the walls in this section were affected by salinization.

Discussion

Salinity erosion damage deterioration mechanism

Salinity erosion is the main cause of bottom erosion in rammed earth walls, as indicated by the experimental testing of soluble salt content, ion composition, and mineral composition in the bottom erosion area of the Great Wall. Combined with studies on the structural damage of salt-affected soils in geotechnical engineering38, it can be concluded that salinity erosion is the main cause of bottom erosion in the walls. The types of soluble salts in the rammed earth walls in Gansu Province are similar to those in other archeological sites in northwest China. For example, studies by Yang39 and Lin40 on the salt content of sites such as Suoyangcheng, Jiaohe Ancient City, Beiting, Xixia Mausoleum, and Shuidonggou showed that the main soluble salts in these sites were NaCl and Na2SO4, with Na2SO4 content equal to or higher than NaCl. The XRD results showed that the soil mineral composition included quartz, illite, calcite, and kaolinite. The weathering of soil minerals promotes the formation of salts, especially in situations where the soil is insufficiently hydrated, the concentration effect may lead to the precipitation and formation of salts41. For example, the formation of Na+ and K+ ions from the weathering of feldspar minerals provides the basis for the formation of soluble salts. The dissolution of calcite cement leads to the formation of gypsum, and the dissolution of dolomite cement leads to the formation of efflorescent salts42. In the investigation of the SH section, white salt crystals were clearly visible in the erosion area at the bottom of the wall, forming a salt-affected zone (Fig. 16).

Salinity erosion in rammed earth walls is mainly caused by the transport, crystallization, and dissolution of soluble salts. In the northwest region, due to rainfall and evaporation, fluctuating groundwater levels repeatedly wet and dry the soil at the bottom of the site43, and the fluctuation of capillary water often accompanies the transport of soluble salt ions44. The combined action of water and salt leads to the development of a large number of erosion damage in the site. Moreover, temperature and humidity changes can cause the repeated dissolution and crystallization of soluble salts. The bottom erosion area of the rammed earth walls contains a large amount of Na2SO4, and related research results have shown that temperature significantly affects the solubility of Na2SO445. When the temperature is below 32.5°C, Na2SO4 crystallizes as Na2SO4·10H2046. Microscopic observations indicate that the volume after crystallization is 3.1 times larger than before47, causing microstructural cracking and damage to the site soil, reducing its mechanical properties48. Although the volume of NaCl does not significantly increase after crystallization, the presence of NaCl reduces the solubility of Na2SO449, thereby exacerbating the damage to the site soil and accelerating its deterioration. In summary, the salt in the rammed earth walls exhibits characteristics of crystallization expansion, dissolution shrinkage, and crystallization expansion. Under changes in moisture content and temperature, salt crystallizes and dissolves, leading to the continuous loosening of the site soil structure and the formation of erosion damage.

There are differences in soluble salt content between the southern and northern sides of the rammed earth walls, with more severe bottom erosion development on the southern side. By measuring the temperature changes in the bottom erosion areas of the southern and northern sides of the walls (Fig. 17) and considering the differences in salt content, it can be observed that the southern side of the rammed earth walls is sun-facing and receives longer sunlight exposure, resulting in greater temperature fluctuations on the wall surface and a stronger coupling effect between dry-wet cycles and salt accumulation. This leads to higher levels of soil deterioration and accelerated damage. In contrast, the northern side is mainly in the shade, with smaller temperature fluctuations, lower salt content in the erosion area, a gentle coupling effect between dry-wet cycles and salt accumulation, and relatively slower deterioration processes. The soluble salt content is highest in the bottom erosion area of the rammed earth walls, followed by the area one-third from the ground, and lowest in the area two-thirds from the ground. This pattern is similar on both the southern and northern sides of the walls. During the dry-wet cycles, salts accumulate and gradually move from the erosion area to the surface and bottom of the walls. The upward movement of salts is facilitated by capillary action. Additionally, this spatial distribution pattern of soluble salts indicates that under the climatic conditions of concentrated rainfall and rapid evaporation in arid areas, dissolved salts rapidly accumulate in the roots of the site, forming a salt-affected zone.

Erosion damage survey and risk assessment based on digitization

The study conducted a survey of erosion damage in Gansu Province using digital technology and low-altitude drone photogrammetry. 3D point cloud models were established for key sections to quantify their morphological characteristics. This approach enables the classification and risk assessment of erosion damage from a macroscopic distribution to key sections. Based on the survey results, a risk map of erosion damage was created, providing a reference for the development of grading standards for the damage in immovable cultural relics.

Figure 18a shows the classification of erosion damage risks at the county level based on the number of erosion damage points in different county-level administrative divisions. Among them, Shandan County in Zhangye City has the highest number of erosion damage points and the highest risk level, followed by Yongchang County. The macroscopic erosion damage risk map not only provides risk warnings for government agencies but also serves as a basic data foundation for heritage protection by cultural relic protection units, helping them identify practical areas for protection and restoration projects. In addition, the erosion damage risk map can be extended to include development intensity classification maps and priority protection distribution maps, enabling comprehensive and regional assessments of erosion damage risks along the Great Wall. Figure 18b shows the erosion damage classification of different segments within a single section based on the fitting of erosion damage morphological characteristics. Taking the JA section as an example, the three-dimensional point cloud model was sliced at intervals of 5 m to calculate the morphological erosion rate, enabling the classification of erosion damage severity with a 5 m accuracy for a single section. The study achieved a graded assessment of erosion damage status from a macroscopic provincial level to a single section, with complete and comprehensive data coverage and high accuracy in erosion damage risk classification. Subsequent regular and timely digital surveys of erosion damage can enable real-time monitoring and timely risk warnings, providing technical support for the rational protection and dynamic monitoring of the Great Wall.

Innovations and Limitations

Innovations

Firstly, at the methodological level, the study utilized low-altitude drone photogrammetry technology to establish a digital method route for rapid survey and precise quantification of erosion damage, enabling efficient, comprehensive, and rapid damage surveys. The use of a Web GIS database platform for data management and 3D point clouds delivered visualized results. The digital method route developed in this study can be applied to various surveys of damage in immovable cultural relics, establishing a comprehensive database of damage information. Secondly, through the survey of erosion damage in the provincial area, the study fills the gap in the unclear macroscopic spatial distribution of damage and reveals the coupling relationship between the distribution of erosion diseases and natural geographic factors such as elevation, land use type, and soil type. Thirdly, the study achieved precise quantification of the morphological characteristics of erosion damage using 3D point cloud models, providing a reference for the development of grading standards for damage in immovable cultural heritage. Fourthly, the study revealed the distribution pattern of salinity erosion, clarifying the correlation between salt distribution and natural factors such as orientation and temperature, which were mutually verified with the deterioration process of salinity erosion damage. The study also created a risk map of erosion damage for risk warning, providing support for the protection and restoration of the Great Wall and offering a more scientific reference for the development of repair measures and protection strategies for cultural relics.

Limitations

The limitations of the study are as follows: Firstly, the study only focused on the survey of the Great Wall, without considering other affiliated facilities such as platforms, military settlements, etc. Future research will expand the scope of the study to include these structures. Secondly, the study mainly focused on the Ming Great Wall, and further research will be conducted on earlier walls, such as the Han Great Wall, using the digital survey method developed in this study. Thirdly, the study primarily investigated the salt-alkali erosion patterns based on physical surveys, focusing on the walls and their bottom erosion areas, without considering the surrounding environment, such as farmland. Due to the large uncertainty in the distribution of salt content in the surrounding environment, the pattern has not yet been clarified, and further investigations will be conducted in conjunction with the field of archeology to explore these influences in more depth.

Conclusions

The study utilized low-altitude drone photogrammetry technology to conduct a survey of erosion damage along the Ming Great Wall in Gansu Province, capturing the distribution of the damage. Geospatial analysis methods were used to analyze the macroscopic distribution patterns of the damage. Three-dimensional point cloud models were established for key sections to quantify their morphological characteristics. Experimental testing was conducted to explore the distribution patterns of salinity erosion in the formation and development processes of erosion damage. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The overall spatial distribution of erosion damage exhibits clustering characteristics, with a concentration of damage in Shandan County and Gaotai County in Zhangye City, Yongchang County in Jinchang City, Liangzhou District and Gulang County in Wuwei City, Changcheng District in Jiayuguan City, and Suzhou District in Jiuquan City. The distribution characteristics of erosion damage are closely related to natural geographic factors, mainly occurring in high-altitude areas, with a predominance of farmland and bare land, and the soils in these areas are often affected by salinization.

(2) There are significant differences in the morphological characteristics indicators of erosion damage. The data for erosion height and depth are relatively concentrated for different sections, while the data for erosion area and morphological erosion rate are more dispersed. The orientation of the erosion areas has a minor impact on the erosion volume, except for the noticeable lower erosion height in the north-south oriented sections. The risk levels of the ten sample sections, from high to low, are SLB > ESLB > SH > HYH > CX > JA > QSB > CF > FCB > LFZ.

(3) The distribution of salinity erosion is closely related to the orientation and location of the rammed earth walls. The spatial distribution of soluble salt content is affected by the orientation of the erosion areas, with higher salt content in the southern side of the walls compared to the northern side. The differences in salt content between the eastern and western sides are small. Soluble salts are unevenly distributed within the walls, mainly concentrated at the roots of the walls. The highest soluble salt content is found in the bottom erosion area, and the salt content gradually decreases from the erosion area to the top of the walls. Salinity erosion is the main cause of bottom erosion in the rammed earth walls, with NaCl and Na2SO4 exhibiting characteristics of crystallization expansion, dissolution shrinkage, and crystallization expansion. In the presence of changes in moisture content and temperature, salt crystals form and dissolve, leading to the continuous loosening of the soil structure in the site. The external forces cause the surface of the site to be continuously depressed, eventually resulting in erosion damage.

Future research directions: Establishing digital damage archives for large-scale cultural heritage using technologies such as low-altitude remote sensing and satellite remote sensing holds great promise. Digital surveys of damage have achieved comprehensive coverage of damage information from a macroscopic to microscopic scale. Additionally, computer vision using artificial intelligence can be used to retrieve, analyze, and statistically process database information. Regular and timely digital surveys of damage can enable real-time monitoring of damage conditions and timely risk warnings, providing technical support for the rational protection and dynamic monitoring of the Great Wall. This approach can be extended to other archeological excavation research projects or intervention projects in cultural heritage conservation, demonstrating high applicability and significance.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- UAV:

-

Unmanned aerial vehicles

- 3D:

-

point cloud Three-dimensional point cloud

- RTK:

-

Real-time kinematic

- Web:

-

GIS Web of geographic information system

- ANN:

-

Average nearest neighbor analysis

- TDS:

-

Total dissolved solids

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

- IC:

-

Ion chromatography

- EC:

-

Electrical conductivity

- DEM:

-

Digital elevation model

References

Relics GPBO. Report on the Protection of the Great Wall of China (2017).

Li, L., Feng, R. & Xi, J. Ecological risk assessment and protection zone identification for linear cultural heritage: a case study of the Ming Great Wall. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (2021).

Cao, Y., Bowker, M. A., Delgado-Baquerizo, M. & Xiao, B. Biocrusts protect the Great Wall of China from erosion. Sci. Adv. 9, eadk5892 (2023).

Pu, T., Chen, W., Du, Y., Li, W. & Su, N. Snowfall-related deterioration behavior of the Ming Great Wall in the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Nat. Hazards 84, 1539–50 (2016).

Haiying, Z., Zuixiong, L. & Wenfeng, H. Study on the main diseases and protection of the Great Wall sites in Gansu Province. Cult. Relics Prot. Archaeol. Sci. 1, 28–32 (2007).

Manli, S., Zuixiong, L. & Xudong, W. Classification research on site diseases in arid areas. J. Eng. Geol. 15, 772–8, 765 (2007).

Cui, K., Wu, G., Du, Y., An, X. & Wang, Z. The coupling effects of freeze-thaw cycles and salinization due to snowfall on the rammed earth used in historical freeze-thaw cycles relics in northwest China. Cold Reg Sci. Technol. 160, 288–99 (2019).

Cui, K., Zhao, X., Hu, M., Yang, C. & Xie, G. Effect of salt content on the evaporation and cracking of soil from heritage structures. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 3213703 (2021).

Kai, C., Wenwu, C. & Xudong, W. Microscopic mechanism research on wind erosion damage in saline-alkali belt of archaeological sites in arid areas. Rock and Soil Mech. 33, 1167–1672 (2012).

Yue, J., Huang, X., Zhao, L. & Wang, Z. Study on the factors affecting cracking of earthen soil under dry shrinkage and freeze–thaw conditions. Sci. Rep.-UK 12, 1816 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Conservation of Jiaohe ancient earthen site in China. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 3, 270–81 (2011).

Kai, C., Wenwu, C. & Jing, K. Deterioration effects of archaeological sites in arid and semi-arid regions under the dual effects of alternate wet and dry conditions and saline-alkali conditions. J. Cent. South Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 43, 2378–84 (2012).

Guo, Q. et al. Key issues and research progress on the deterioration processes and protection technology of earthen sites under multi-field coupling. Coatings 12, 1677 (2022).

Xue, Y. & Manli, S. Quantitative evaluation of the degree of site disease based on grey relational analysis method: a case study of individual buildings of the Ming Great Wall in northern Shaanxi. Dunhuang Res. 1, 128–134 (2016).

Cui, K., Du, Y., Zhang, Y., Wu, G. & Yu, L. An evaluation system for the development of scaling off at earthen sites in arid areas in NW China. Herit. Sci. 7, 14 (2019).

Du, Y., Chen, W., Cui, K. & Zhang, K. Study on damage assessment of earthen sites of the Ming Great Wall in Qinghai Province based on Fuzzy-AHP and AHP-topsis. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 14, 903–16 (2020).

Hongmin, T., Yucheng, S. & Kun, L. Study on the disease characteristics of the Ming Great Wall sites along the Silk Road. J. Seismol. Eng. 40, 1278–86 (2018).

Kai, C., Xiancan, C. & Wenwu, C. Study on the differential effects of erosion areas on the shady and sunny slopes of linear earth sites in the Hexi Corridor region. J. Eng. Geol. 25, 547–55 (2017).

Du, Y., Cui, K., Chen, S., Dong, W. & Chen, W. Quantitative research on the development difference of scaling off on the sunward side and nightside of earthen sites. J. Cult. Herit. 57, 107–17 (2022).

Zhang, Y. Knowledge of earthen heritage deterioration in dry areas of China: salinity effect on the formation of cracked surface crust. Herit. Sci. 11, 41 (2023).

Wang, Y., Li, J., Xia, Y., Chang, B. & Luo, X. A case study investigation-based experimental research on transport of moisture and salinity in semi-exposed relics. Herit. Sci. 12, 9 (2024).

Guidi, G. et al. A multi-resolution methodology for the 3d modeling of large and complex archeological areas. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 7, 39–55 (2009).

Bemis, S. P. et al. Ground-based and UAV-Based photogrammetry: a multi-scale, high-resolution mapping tool for structural geology and paleoseismology. J. Struct. Geol. 69, 163–78 (2014).

Manajitprasert, S., Tripathi, N. K. & Arunplod, S. Three-dimensional (3D) modeling of cultural heritage site using UAV imagery: a case study of the Pagodas in Wat Maha That, Thailand. Appl. Sci. 9, 3640 (2019).

Lambert, J. M. & Jacob Skousen, B. A critical review of UAS-based aerial photography and photogrammetry of Cahokia’s Grand Plaza. J. Archaeol. Sci.: Rep. 47, 103789 (2023).

Silverman, B. W. (ed.). Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis (Chapman and Hall, 1987).

Li, C., Qian, Y., Li, Z. & Tong, T. Identifying factors influencing the spatial distribution of minority cultural heritage in Southwest China. Herit. Sci. 12, 117 (2024).

Ma, Y., Zhang, Q. & Huang, L. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Fujian Province, China. Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 883 (2023).

Li, X. Determination of the temporal–spatial distribution patterns of ancient heritage sites in China and their influencing factors via GIS. Herit. Sci. 12, 143 (2024).

Chen, H., Chen, W., Li, X., Jia, B. & Zhang, S. The effect of SH-lime composite material on capillary water rise resistance in the Great Wall. J. Build Eng. 85, 108512 (2024).

Su, N., Yang, B., Chen, W., Xu, L. & Li, Y. Influence of prevailing wind direction on sapping quantity of rammed earth Great Wall of the Ming Dynasty. Coatings 12 (2022).

Rhoades, J. D. in Advances in Agronomy (ed. Sparks, D. L.) 201–251 (Academic Press, 1993).

Bañón, S., Álvarez, S., Bañón, D., Ortuño, M. F. & Sánchez-Blanco, M. J. Assessment of soil salinity indexes using electrical conductivity sensors. Sci. Hortic-Amsterdam 285, 110171 (2021).

Zachariadis, G. A., Lyratzi, A. I. & Stratis, J. A. Ion chromatographic method for the determination of cations of group IA and IIA in water samples, pharmaceuticals and energy drinks by non-suppressed conductometric detection. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 9, 941–7 (2011).

Singh, V. & Agrawal, H. M. Qualitative soil mineral analysis by EDXRF, XRD and AAS probes. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 81, 1796–803 (2012).

Shi, X. et al. Cross-reference system for translating between genetic soil classification of China and soil taxonomy. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 70, 78–83 (2006).

Kai, C., Xiaozheng, Z., Mingji, Z., Wenwu, C. & Wenfeng, H. Degradation and wind erosion effects of saline-alkali earth in erosion areas of arid archaeological sites (part III): capillary processes. J. Rock. Soil Mech. 44, 2043–51 (2022).

Haiying, Z., Zuixiong, L. & Wenfeng, H. Major diseases and causes of arid archaeological sites in Northwest China. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 22, 2875–2880 (2003).

Shanlong, Y., Xudong, W. & Qinglin, G. Experimental study on salt damage threshold of earth sites in Northwest China. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 54, 1–8 (2018).

Qingtao, L., Xudong, W. & Qinglin, G. Preliminary analysis of salt damage status of West Xia Mausoleum No. 3 and No. 6 in Yinchuan. Dunhuang Res. 6, 75–80 (2009).

Jinhua, W., Shaojun, Y. & Weizhong, R. Research on the Rating System for Stability Analysis of Grotto Rock Masses (China University of Geosciences Press, 2013).

Scherer, G. W. Stress from crystallization of salt. Cement Concrete Res. 34, 1613–24 (2004).

Qiangyi, Y. & Chengwei, L. Experimental study on the weathering effects of capillary water dry-wet cycles on earth site. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 8, 517–25 (2012).

Jianwei, Y. et al. Study on the improvement of hydrological properties of soil at simulated archaeological sites in Kaifeng. Eng. Sci. Technol. 52, 46–55 (2020).

Ding, X., Zhang, T., Zhang, S., Shen, Z. & Fang, T. Experimental determination and modelling of the solubilities of sodium sulfate and potassium sulfate in sub- and supercritical water. Fluid Phase Equilbr. 483, 31–51 (2019).

Khan, M. S. & Rogak, S. N. Solubility of Na2SO4, Na2CO3 and their mixture in supercritical water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 30, 359–73 (2004).

Steiger, M. Crystal growth in porous materials—II: Influence of crystal size on the crystallization pressure. J. Cryst. Growth 282, 470–81 (2005).

Price, C. A. Predicting environmental conditions to minimise salt damage at the Tower of London: a comparison of two approaches. Environ. Geol. 52, 369–74 (2007).

Jiang, G., Guo, F. & Polk, J. S. Salt transport and weathering processes in a sandstone cultural relic, North China. Carbonate Evaporite 30, 69–76 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project of National Key Research and Development Program of China- Project II: Large-scale linear cultural heritage value spatial-temporal intelligent mining and knowledge map construction (2024YFB3908902).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by T. Wang, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Li, Z. & Chen, Z. Spatial investigation and pattern exploration of salinity erosion damage of the Ming Great Wall in Gansu, China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 108 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01618-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01618-w

This article is cited by

-

Study on the subsidiary border wall and its siting layout of the Ming Great Wall

npj Heritage Science (2025)