Abstract

As a World Cultural Heritage site, researching the building materials of the Wudang Mountain is crucial for conservation and restoration. This study applied multi-analytical approaches to examine the plastering of the Huilong Taoist Temple, revealing significant differences in raw materials and techniques between two layers wall plastering. The surface layer uses magnesium lime, lateritic soil, ocher, and paper mulberry bast fiber, while the base layer lacks ocher but has more lime. Coarse materials form the base, with finer materials used for the surface. The comparatively good condition of the wall of the Huilong Temple is benefited by the scientific recipe of the raw materials and the rigorous plastering process. This study not only enriches the understanding of the raw materials and techniques used in the plastering of ancient Chinese royal buildings, but also provides a scientific reference for the conservation and restoration of the ancient building complex in the Wudang Mountain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

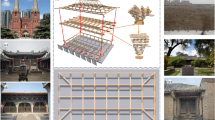

The Huilong Taoist Temple is one of the famous temples in the Wudang Mountain, Shiyan City, Hubei Province, China (Fig. 1). The ancient Taoist building complex in the Wudang Mountain was built by the royal family in the Yongle period of the Ming Dynasty (AD1403-1424). The buildings were given tremendous status in Taoism by the royal family in the Ming Dynasty. In 1994, the ancient building complex including the Huilong Taoist Temple in the Wudang Mountain was listed as a World Cultural Heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The World Heritage Committee gave an excellent appraisal of the ancient building complex and claimed that represents the highest level of Chinese art and architecture in the past millennia1. However, the Huilong Taoist Temple has experienced varying degrees of natural and human damages for hundreds of years.

From April to August 2019, the Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology carried out archeological excavations at the Huilong Taoist Temple site. The site consists of a three south-facing courtyard and one west-facing courtyard. The remaining structures include main halls, gates, courtyard walls, courtyard bridge, pools, Taoist towers, and paths. The exterior walls of the palace and the courtyards remained reddish-brown (Fig. 2). The reddish-brown represents the stateliness, wealth and noble status of the emperors and the royal family in ancient China, such as the Imperial Palace of Beijing and the Imperial Palace of Shenyang.

In ancient construction, plastering was a method of using mortar put on the wall or floor of a building for leveling, moisture-proof and decoration. The appearance of plastering technology of China can be traced back to the Yangshao period (ca. 6000 BP)2. The raw materials of the plastering in prehistoric times were clay materials with calcium oxide (CaO) or calcium carbonate (CaCO3)3. Plastering appeared widely in the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of China in the mid to late Neolithic Age, and providing an essential carrier for the rise of secco4. A large number of secco that painted on the white plastering layer had been excavated at the Shimao site of the Erlitou period (ca.1750-1520BC) in Shaanxi Province, China5. Plastering was gradually used in palaces, temples, graves and other buildings during the Qin and Han dynasties.

The original plastering process generally used organic-tempered daub as the base layer, and then put a white plastering layer over the base. It was recorded in Yingzaofashi (Technical Treatise on Architecture and Craftsmanship in the Song Dynasty) that there are four steps to painting plastering layers on the wall in ancient China. The first step is to use coarse earthen plasters to fill the hollows on the surface of the brick wall, and then use earthen plasters with relatively fine particle size to level the surface of the coarse layer, and waiting for it to dry. After smoothing with fine earthen plasters, it was finally covered with a layer of pigmented plasters6. The red plastering was used more widely in the ancient Chinese architectures, especially during the Ming and Qing dynasties. In this period, cinnabar is added to the surface plastering as a colorant in the red wall buildings7.

Some conservation researchers have carried out scientific study on the ancient plastering technology based on historical records. Ergenç et al. provided a systematic exposition on how to characterize ancient mortars and plasters. By reviewing previous studies, they summarized the theories, methods, and significance of researching these two building materials8. These physicochemical analyses mostly focus on the plasters in ancient wall painting. For example, some research teams studying ancient building materials have analyzed the plaster layers of wall paintings in Northwest China, focusing on the raw materials and the effects of different materials on the performance of the plaster layers. The results show that the raw materials for the plaster layers in some grottoes in Northwest China are natural sedimentary soils from nearby rivers, and no artificial addition of lime was added. The artificial addition of sand, plant fibers, and lime can affect the water absorption properties, strength, and other properties of the plaster layers9,10. The aforementioned research teams have conducted systematic simulation experiments and scientific analyses on the raw materials, degradation mechanisms, and conservation and restoration of plasters in wall painting. However, most of the plaster materials studied are applied to ancient wall painting, and scientific research on plaster materials directly used for the walls of ancient high-grade buildings is relatively rare. Based on Gongchengzuofa (Code of Conduct for Building and Construction of the Qing Dynasty), the protection workers of the Palace Museum pointed out that the red plastering of the Taihe Palace was made of lateritic soil, white plaster, hemp fiber, sticky rice and alum11.

There is very limited analytical research on the material and technology of ancient Chinese plastering, which is not conducive to the conservation and restoring of the existing ancient buildings. Past researches showed that there were differences in time and region in the raw materials and techniques of plastering. Raw materials used, the thickness of plastering layer, the technique of plastering layer, the tools used in operation, and the environmental conditions of plastering layer are the main factors which may affect the properties of plastering. Specifically, to ensure the durability and resistance of the plaster layer, one should choose aggregates and corresponding binders with appropriate mechanical and permeability properties. The plastering should gradually use finer aggregates in external layers to ensure adhesion with each other and hydrophobicity of each layer. Currently, the plastering on the walls of the Huilong Taoist Temple has suffered from spalling and is gradually being lost due to prolonged exposure to rain and snow erosion and freeze-thaw cycles. This can affect the structural integrity of the brick and stone walls, causing cracks and corrosion and mold growth within the walls12,13,14. The systematic physical and chemical analysis can interpret the reasons for the differences in the matching of raw materials and the formulation of the process sequence by ancient artisans, and also reflect the current performance state of plastering. Most ancient buildings will deteriorate due to natural or human factors, and the materials needed for restoration should have mechanical and physical-chemical properties similar to the raw materials of the ancient buildings15. An accurate characterization of the ancient buildings can contribute to the understanding of history and architectural function of the building, as well as to their conservation and restoration16,17. The understanding of the composition and performance of ancient plastering are essential to repair and renovate the existing ancient buildings and develop new compatible materials18.

This study aimed to understand the characteristics of the plastering from the Huilong Taoist Temple. It could also contribute to the understanding of the other imperial buildings in the Ming and Qing dynasties. The results provide a theoretical reference for the conservation and restoration of the Huilong Taoist Temple.

Methods

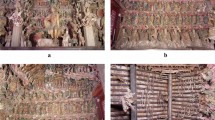

According to the observation of the palace buildings remains at the excavation site, the color of the exterior walls is reddish-brown and similar to the color of the walls of the Imperial Palace in Beijing. Some plastering blocks on the verge of falling off the walls from different rooms at the site were collected for experimental analysis. Based on a macro-observation, it showed that most of the plastering samples were reddish-brown and a few were white on the surface (Fig. 3).

According to local survey, the white layer of the plastering samples is lime pasted by modern people, which the original plastering surface was reddish-brown. By observing the plastering cross-section, the plastering includes two layers, the surface layer is dark reddish-brown with 5 mm of thickness, and the base layer is light reddish-brown with 10 mm of thickness (Fig. 3). The number of fibers is unevenly distributed in both surface and base layers.

Five plastering samples were selected for scientific analyses, and the detailed descriptions of sample are shown in Table 1.

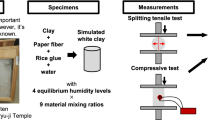

Grain size analysis was performed on a Malvern Mastersizer 2000 laser grain size analyzer. In this test, ultra-pure water was used as dispersant, and the refractive index of dispersant was adjusted to 1.33. The test was repeated three times for each group of samples and the average value was taken.

The X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry spectra of the powders of each layer were obtained using ZSX primus wavelength dispersive scanning X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, it is produced by Rigaku Corporation, X-ray diameter is 100μm, rhodium target, maximum power > 4 kW.

The X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) measurements on each layer were performed on a Smartlab 9KW diffractometer, with the scanning range of 10–90° 2θ. The scan speed is 60°/min, and the scan step size is 0.1°.

Infrared spectroscopic analysis was performed on a NEXUS-870 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer from Nicolet instrument company of the United States. The spectral resolution is 0.2 cm−1, and the measurement range of 4000–400 cm−1. Transmittance repeatability is better than 99.9%, absorbance repeatability is better than 0.005 A.

Simultaneous thermal analysis was performed on a PerkinElmer STA-8000 synchronous thermal analyzer. The experimental atmosphere was nitrogen, starting at 25 °C and heating to 1000 °C at 10 °C/min.

The fiber analysis was observed under the XWY-VI fiber analyzer. The fiber sample (HLG-1F) was pinched out from the plastering layer with tweezers and ultrasonically cleaned with distilled water. After the fibers were cleaned, they were dried at 40 °C for 24 h in the drying oven before being taken out for experiment. Then, placing an appropriate number of fibers on the glass slide, drop a small amount of Herzberg stain, disperse the fiber sample evenly with an anatomic needle, and observe under the fiber analyzer.

Results

Grain size analysis

The results of the grain size analysis (Fig. 4) showed that the D50 value (Median Grain Size), D90 value (90th-Percentile Grain Size) and the mean particle size of the surface layers are both significantly less than the base layer in all samples, which indicates the grain size of the raw materials used in the surface layers are finer and more compact.

Studies have shown that the plastering of surface layers was thinner than the base layers because the plastering of surface layers require faster carbonation and a smaller mechanical shrinkage range to avoid surface cracks, so all the surface layers samples are in this way19. The density of the plastering layer would be improved by finer materials that could also decrease the capillary water absorption of surface layer, thereby inhibiting the later weathering effect. Fine materials can create a glazed and flat surface, satisfying the esthetic effect, and inhibiting the generation of the bacterial colonies and other microorganisms on the wall15,19. The base plastering layers of the Huilong Taoist Temple are sightly thicker, so they could provide greater support strength as base layers20. The base plastering with coarse raw materials has a relatively strong skeleton structure and mechanical resistance, thus improving the stability and compressive strength of the base plastering19. The rough texture of base plastering could increase its adhesion to the surface layer and improve the anchoring ability of base layer to brick wall.

Chemical composition analysis

The result of XRF analysis revealed that the chemical composition of the plaster samples is primarily composed of CaO, Fe2O3, MgO, SiO2, and Al2O3, with minor amounts of Na2O, K2O, and SO3 (Table 2). The content of CaO, Fe2O3, and MgO in the surface layer of the plastering differs significantly from that in the base layer. The CaO and MgO content in the surface layer is much lower than in the base layer, while the Fe2O3 content is much higher. This suggests that the different raw materials or the different ratios of materials were used in the surface layer and the base layer, resulting in significant differences in the chemical composition between the two layers.

XRD analysis

From the XRD results, the mineralogical composition of the plastering samples was obtained, including calcite, quartz, hematite, feldspar, clay minerals and gypsum (Fig. 5). In the phase diagram, the diffraction peaks of hematite in the surface layer are significantly stronger than those in the base layer, which corresponds to the higher Fe2O3 content in the surface layer compared to the base layer.

Combing with the results of the chemical composition analysis and the XRD analysis, we can make preliminary speculations about the raw materials used in the two layers of plastering. First, the large proportion of CaO (Chemical composition analysis) and calcite (XRD analysis) of the plastering, which is possibly a product of the long-term carbonation of lime (CaO + CO2 → CaCO3). Accordingly, the lime is one of raw materials of plastering. In particular, the gypsum is detected in the surface layer of sample HLG-2 but not in the base layer, therefore we inferred that the gypsum in the surface layer may have been produced by the reaction of Ca2+ with SO42−, and the SO42− from clay or lime of plastering (Ca2+ + SO42−+ 2H2O → CaSO4⋅2H2O). Based on the results of the compositional analysis, the plastering contains varying amounts of SO3, ranging from 0.26% to 2.42%. Additionally, it cannot be ruled out that the SO42− may originate from atmospheric pollutant acids, such as acid rain21,22.

The mineralogical phases, including hematite, quartz, feldspar and clay minerals, are detected both in the surface and base layers close to those of lateritic soil in southern China23. This indicates that lateritic soil may have been used in the plastering layers as the raw materials.

Infrared spectroscopic analysis

According to ancient literature, some glutinous rice and tung oil are added as organic additives when making plaster11. Attempts were therefore made to identify organic additives by infrared spectroscopic analysis. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (Fig. 5d) spectra demonstrated that the bands at 714 cm−1, 873 cm−1, 1427 cm−1, 1800 cm−1 and 2511 cm−1 were attributed to calcite, and those at 762 cm−1, 802 cm−1 and 1019 cm−1 corresponded to quartz. The absorption at 460 cm−1, 535 cm−1, 602 cm−1 and 1090 cm−1 were the peaks of the Fe2O3, the absorption at 3423 cm−1 corresponded to hydroxyl group in water, and the peaks at 1600 cm−1 and 1631 cm−1 were belonged to gypsum24. The characteristic absorption peak of C–O bond occurs in the 1000–1200 cm−1 range for carbohydrate compounds such as starch. At the same time25, the quartz also had a strong absorption peak in this region, which led to the adsorption peaks of carbohydrates were hard to be identified.

The presences of quartz in the plastering samples made it difficult to determine whether carbohydrate compounds were added to plastering by infrared spectroscopy. Similarly, no other organic additives are detected in the plastering samples such as animal blood or tung oil.

Simultaneous thermal analysis

Simultaneous thermal analysis allowed us to determine the ratio of calcite in each layer, and the source of the calcite in plastering is the lime used as the cementing material. Therefore, the proportion of lime in the raw materials could be calculated by the calcite content. In the TGA-DSC curve (Fig. 6), the endothermic peak and weight loss around 100 °C are attributed to the loss of the adsorbed water26,27. The characteristic endothermic peak (443–510 °C) appears to be due to the decomposition of calcium hydroxide (Ca (OH)2), which is created from the incomplete carbonation of lime. The endothermic peak between 630 and 800 °C is corresponded to the decomposition of calcium carbonate. According to the weight loss of calcium hydroxide and calcium carbonate in the TGA curves that could be calculated the addition of lime as raw material in the surface layer is ~26–36%, and that in the base layer is approximately 60% (Table 2).

Fiber analysis

It can be observed that fibers are added both in the surface and base layers. The FT-IR spectrum of fiber sample HLG-1F showed that the presence of lignin and cellulose compounds with bands at 1431 cm−1 and 1035 cm−1 (Fig. 7c), indicating that the fibers are plant fibers.

Observing under the fiber analyzer (Fig. 7a, b), the fibers are reddish-brown, long and tapering at both ends, with occasional branched or globular ends. The fiber morphology is naturally curved, and there are obvious transverse and segmental stripes on the fiber cell wall. There are many primary cell walls scattered in form of floccule between the fibers. The outer surface of some fiber cell walls is coated with gel coat (transparent film), which is relatively obvious at the ends of the fibers.

The observed fiber characteristics are compared with the Papermaking Raw Materials of China An Atlas of Micrographs and the Characteristics of Fibers28, and it can be identified that the fibers used in plastering are bast fiber of paper mulberry (The scientific name is Broussonetia papyrifera). Paper mulberry has a long history and culture in China. It was recorded in Qiminyaoshu (Encyclopedia of Ancient Chinese Agriculture) that the bast fiber of paper mulberry is one of the raw materials used by Cai Lun in papermaking29. The bast fiber of paper mulberry is a high-quality raw material for papermaking and textile, with significant advantages of being spindly, white, flexible, high strength, and good quality30.

Discussion

By integrating the results from multi-analytical approaches, the raw materials of the plastering layers can be largely determined, and some features about the manufacturing process can also be obtained. In the chemical compositional analysis and the XRD analysis, the presence of calcite, hematite, and clay minerals indicates that the raw materials for the plastering layers included lime and lateritic soil, with the addition of fibers.

Many historical texts recorded that the lateritic soil as a building material in the ancient Chinese society. For example, in Xiangyanjieyi (The Dialects that recorded dialects and colloquialisms of Beijing and Tianjin in the Qing Dynasty), it recorded that “if cinnabar is not available, it can be replaced with lateritic soil”31. In the Gongchengzuofa (Code of Conduct for Building and Construction of the Qing Dynasty), it said that “the red plastering is made of a certain amount of lime and lateritic soil”32. The European architecture artisans also used lateritic soil as a coloration material for the red plastering in the 16th century33. It is worth noting that the Fe2O3 content in the lateritic soil of China is generally around 10%34, which is consistent with the Fe content detected in the base layers. The volcano-sedimentary metamorphosed rocks in the Wudang Mountains Block are prone to weathering easily, and forming lateritic soil horizons with good cementitious properties, which provides a closer source for the collection of lateritic soil.

The proportion of Fe2O3 (30–53%) in the surface layer is significantly higher than the base layer (9–16%), but the Fe2O3 content of laterite soil is only 10%. Therefore, this suggests that the iron-containing materials in the surface layer are not just laterite soil. In reviewing the literature, it was recorded in Yingzaofashi (Technical Treatise on Architecture and Craftsmanship in the Song Dynasty) that “the raw materials for making red plastering are lime, ocher and lateritic soil”6. The main component in the ocher is Fe2O3 and its Fe content is generally around 50%, and the main phase of ocher is hematite in the XRD analysis35,36, so the ocher may have been added to the raw materials of the surface layer besides lime and lateritic soil. The use of lateritic soil and ocher is the reason that the surface layers are dark reddish-brown and its Fe content is more than 50%.

Taken together with the results of the multi-analytical approaches, the raw materials of the base layer should be lime, lateritic soil and fibers, and the added proportion of lime to the base layer is higher than that added to the surface layer. The relatively large amount of lime in the base layer could carbonize into calcite and then have produced reaction with laterite soil and formed a poorly soluble salt with higher cementation, which can further strengthen the cohesive force of base plastering and provide a stable base structure and better resistance to it37,38,39,40,41.

According to our analyses, lateritic soil, ocher, lime and fibers are the raw materials of surface plastering, and the amount of lime is comparatively lower than the others.

When making surface plastering, the amount of lime added to the raw material is reduced, so that the relative proportion of laterite and ocher is higher, thus creating a bright reddish-brown wall, showing the royal grace, solemn style and temperament.

In addition, we found that the magnesium content of the plastering layer is between 7.03 and 22.12%, while the magnesium content in both laterite and ocher is less than 2%42. Some studies have found that the magnesium oxide content in magnesium lime is usually greater than 5%, and magnesium lime is widely used for the ancient buildings in China, and the magnesium lime in ancient China was made from dolomite43. Therefore, it is speculated that the lime in raw materials of plastering from the Huilong Taoist Temple is likely to be magnesium lime.

The fiber analysis results showed that the fibers added to the plastering layer are bast fiber of paper mulberry. A certain amount and length of fibers added to the plastering can form a restraining network structure, improve the adhesion of the plastering, and add fibers to enhance the fatigue resistance, crack resistance, impact resistance and bending strength of the plastering layer44,45,46. In contrast, more fibers are added in the base layer than the surface layer, which can improve the adhesion and strength of the base layer.

Based on the current degree of deterioration of the walls at the Huilong Taoist Temple, protection and restoration work is urgently needed. During the restoration process, the original proportions and particle size characteristics of the raw materials of plastering should be strictly adhered to. The plastering layers should consist of a base layer and a surface layer, with the base layer using coarser raw materials with a higher proportion of lime, and the surface layer using fine laterite soil, ocher, and a small amount of lime to ensure hydrophobicity, resistance, and smoothness of the surface layer.

According to the results of archeological investigation and comprehensive analysis, the wall plastering of the buildings is divided into two layers, namely the surface plastering and the base plastering in the Huilong Taoist Temple. The multi-layer structure of plastering increased its adhesion to brick walls, which can prevent the plastering from coming off the wall due to over thickness. It can also prevent plastering from hollowing and guarantee the thickness of plastering are consistent.

The surface layer is approximately 5 mm thick, and the dark reddish-brown plastering is made of magnesium lime, lateritic soil, ocher, and bast fiber of paper mulberry as raw materials. The addition of lateritic soil and ocher in the surface layer is relatively large, and the grain size of raw materials is fine and uniform, the above characteristics should not only improve the resistance against deterioration and waterproof property of the surface plastering but also created a smooth plane.

The base layer is about 10 mm thick, and its raw materials include magnesium lime, lateritic soil and more bast fiber of paper mulberry. The addition amount of magnesium lime in the base layer is relatively large, and the grain size of raw materials is coarser than that of the surface layer. Specifically, the surface layer contains ~20% magnesium lime, while lateritic soil and ocher account for more than 70%. In the base layer, magnesium lime comprises about 40%, and lateritic soil accounts for more than 50%. The incorporation of coarser lime along with fibers and lateritic soil can contribute to enhancing the strength and durability of the base layer, thereby better supporting the surface layer and improving its adhesion to brick walls. The characteristics of material ratio, grain size and thickness of plaster layer fully embodied the scientific nature of the ancient plastering technology, which reflected the exquisite techniques of ancient craftsmen.

This work analyzes the characteristics of the raw materials and techniques of the wall plastering of the Huilong Taoist Temple by combining historical documents. It provides scientific data to support the conservation and restoration of the ancient building complex in the Wudang Mountain. It also provides a theoretical reference for the selection of compatible materials for conservation and restoration. Future research will continue to investigate the plastering techniques used in ancient palaces, refining the specific operational procedures from raw material selection and preparation to the application of plastering on walls. Additionally, it will explore the similarities and differences in plastering techniques across different regions.

Data availability

No, I do not hace any research data outside the submiitted manuscript file.

References

Li, G., Li, Y. & Kang, Y. The Huilong Taoist Temple site in the Wudang Mountain, Shiyan City, Hubei Province, China. Pop. Archaeo logy 8, 14–15 (2019).

The Shansi Archaeological Team. Institute of Archaeology, Academic Sinica. Excavation of the neolithic sites at Tung-chuang and Hsi-Wang village in Jui-cheng County, Shanxi Province, China. Acta Archaeol. Sin. 1, 1–63+157-178 (1973).

Sun, T., Wei, G., Cheng, B. & Ren, G. Study on the production technology of Baihuimian from Suyang site. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 41, 1949–1954 (2021).

Pei, X. The Preliminary research of neolithic Baihuimian. Stories Relics 3, 3–11 (2017).

Shao, A., Fu, Q. & Sun, Z. Study on the raw materials and manufacturing technology of murals unearthed at the Shimao site in Shenmu County, Shaanxi Province, China. Archaeology 6, 109–120 (2015).

Pan G. & He J. Ying Zao Fa Shi Jie Du (in Chinese) (The interpretation of Technical Treatise on Architecture and Craftsmanship in the Song Dynasty). (Southeast University Press, 2005).

Zhu H. A Research for the surface layer on Chinese traditional architectures with illustrations in Shanxi Province (Master’s thesis, Taiyuan University of Technology, 2009).

Duygu Ergenç, Rafael Fort, Maria J. Varas−Muriel & Monica Alvarez de Buergo. Mortars and plasters—How to characterize aerial mortars and plasters. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 197 (2021).

Jia Q., Chen W. & Tong Y. Influence of material composition on physical performance of earthen plasters. Constr. Build. Mater. 417 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135219 (2024).

Jia, Q., Chen, W., Tong, Y. & Guo, Q. Physicochemical properties and microstructure of plaster layer of ancient wall paintings in Northwest China. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 18, 1683–1696 (2024).

Wang L. The selection and application of materials and techniques in the conservation and restoration of the heritage buildings-Take the hall of supreme harmony for example (Master’s thesis, China National Academy of Arts, 2013).

Groot, C., Hees, R. & Wijffel, T. Selection of plasters and renders for salt laden masonry substrates. Constr. Build. Mater. 23, 1743–1750 (2008).

Carasek, H., Japiassú, P., Cascudo, O. & Velosa, A. Bond between 19th Century lime mortars and glazed ceramic tiles. Constr. Build. Mater. 59, 85–98 (2014).

Thamboo, J. & Dhanasekar, M. Characterization of thin layer polymer cement mortared concrete masonry bond. Constr. Build. Mater. 82, 71–80 (2015).

Bartz, W. & Filar, T. Mineralogical characterization of rendering mortars from decorative details of a baroque building in Kożuchów (SW Poland). Mater. Charact. 61, 105–115 (2009).

Bardelli, F. et al. Iron speciation in ancient Attic pottery pigments: a non-destructive SR-XAS investigation. Synchrotron Radiat. 19, 782–788 (2012).

Barone, G. et al. Potentiality of non-destructive XRF analysis for the determination of Corinthian B amphorae provenance. X-ray Spectrom. 40, 333–337 (2011).

González-Sánchez, J., Fernández, J., Navarro-Blasco, Í. & Alvarez, J. Improving lime-based rendering mortars with admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 271, 121887 (2021).

Nogueira, R., Pinto, A. & Gomes, A. Design and behavior of traditional lime-based plasters and renders. Review and critical appraisal of strengths and weaknesses. Cem. Concr. Compos 89, 192–204 (2018).

Barbero-Barrera, M., Maldonado-Ramos, L., Balen, K., García-Santos, A. & Neila-González, F. Lime render layers: an overview of their properties. J. Cult. Herit. 15, 326–330 (2014).

Çavdar, A. & Yetgin, S. Investigation of mechanical and mineralogical properties of mortars subjected to sulfate. Constr. Build. Mater. 24, 2231–2242 (2010).

Lanzón, M. & García-Ruiz, P. Deterioration and damage evaluation of rendering mortars exposed to sulphuric acid. Mater. Struct. 43, 417–427 (2010).

Tan, Y. et al. Behav. lime-laterite Interact. anti-Eros. mechanism Metakaolin. Rock. Soil Mech. 42, 104–112 https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2020.0442 (2021).

Peng W. The Atlas of mineral infrared spectroscopy. (China Science Publishing, 1982).

Fang S. Studies of Chinese traditional lime mortar’s scientificity and its protection in immovable culture relic. (Master’s thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, 2013).

Genestar, C., Pons, C. & Más, A. Analytical characterisation of ancient mortars from the archaeological Roman city of Pollentia (Balearic Islands, Spain). Anal. Chim. Acta 557, 373–379 (2005).

Cayme, J. & Jr. Asor, A. Characterization of Historica Lime Mortar from the Spanish Colonial Period in the Philippines. Conserv. Sci. Cultural Herit. 16, 33–57 (2017).

Wang J. Papermaking Raw Materials of China An Atlas of Micrographs and the Characteristics of Fibers. (China Light Industry Press, 1999).

Liao Q. Qi Min Yao Shu Zhu Shi (in Chinese) (The interpretation of “Encyclopedia of Ancient Chinese Agriculture”). (China Agricultural Press, 1982).

Jiang, L. et al. Analyses on chemical composition fiber morphology and pulping properties of Broussonetia Papyrifera bark produced in dry-hot valley of the Jinshajiang River. J. Southwest For. Univ. 3, 71–75 (2007).

Li G. Xiang Yan Jie Yi (in Chinese) (The Dialects that recorded dialects and colloquialisms of Beijing and Tianjin in the Qing Dynasty). (Zhonghua Book Company, 1982).

Wang P. Gong Cheng Zuo Fa Zhu Shi (in Chinese) (The interpretation of “Code of Conduct for Building and Construction of the Qing Dynasty”). (China Architecture & Building Press, 1995).

Veiga, M., Silva, A., Tavares, M., Santos, A. & Lampreia, N. Characterization of renders and plasters from a 16th century Portuguese military. Structure Chronol. Durab. Restor. Build. Monum. 19, 223–238 (2014).

Cheng F. Study on characteristics and source provenance of the pleistocene red earth sediments in southern China. (PhD thesis, China University of Geosciences, 2018).

Kang L. Ingredient analysis of haematitum. (Master’s thesis, Hebei University, 2008).

Li, D. et al. Scientific and technological analysis of newly discovered ocher from Dushan Cave site in Guangxi. Quat. Sci. 43, 280–287 (2023).

Zhang, D. Principle and application of stabilization soil with lime. J. Chang’ Univ. 4, 1–12 (1987).

Cultrone, G., Sebastián, E. & Huertas, M. Forced and natural carbonation of lime-based mortars with and without additives: Mineralogical and textural changes. Cem. Concr. Res. 35, 2278–2289 (2004).

Deng, X. et al. Effect of hydrated lime on structures and properties of decorative rendering mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 256, 119485 (2020).

Rusan, R. & Tumpu, M. Effect calcium hydroxide (traditionally called slaked lime) to stabilization of laterite soil. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 1088, 012105 (2021).

Pavan, A. & Little, N. Analytical tests to evaluate pozzolanic reaction in lime stabilized soils. MethodsX 7, 100928 (2020).

Huang, Y. & Fu, B. The change properties of the chemical compositions for Laterite. J. Kunming Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.). 4, 63–66+70 (2002).

Zhou, Y. & Dai, S. Preliminary research on traditional dolomitic lime in ancient Chinese architecture. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 33, 43–50 (2021).

Cinthia, M., Rosário, V. & Jorge, D. Incorporation of natural fibres in rendering mortars for the durability of walls. Infrastructures 6, 82 (2021).

Xie, L. et al. Review of research progress on mechanical properties and water resistance of fiber-building gypsum based composites. N. Build. Mater. 48, 34–39 (2021).

Cinthia Maia, P., Rosário, V. & Jorge de, B. Rendering mortars reinforced with natural sheep’s wool fibers. Materials 12, 22 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the group of the Huilong Taoist Temple site archeologists of the Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (China) who have been working so hard at the site. Thank you to Liping Ma from the Yantai municipal museum for her work on designing and combining the figures in the paper. This study received funding from Ministry of Cultural and tourism of the People’s Republic of China. The Project number is (2013) 718, and the Grant recipient is Guofeng Wei.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Prepared: Tianqiang Sun, Guofeng Wei and Yuhu Kang. Draft and funding: Guofeng Wei. Experiment: Tianqiang Sun and Zhao An. Writing and editing: Tianqiang Sun and Guofeng Wei. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No, I declare that the authors have no competing interests as defined by Springer, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reporte in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, T., Wei, G., Kang, Y. et al. Exploring plastering techniques in ancient Chinese royal architecture at Huilong temple using multi-analytical methods. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 270 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01664-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01664-4