Abstract

A refined 3D numerical model was constructed to reflect the intricate topography, geological structures, and support conditions of the Yuanjue Cave in the Dazu Rock Carvings. The study identifies the main factors influencing the stability of the roof, the deformation and failure modes and key areas, and the current stage of the cave’s stability was determined. The results show that the development of cavity depth acts as the trigger for roof deformation and failure, while the breakage of strip stones is the primary controlling factor. The overall deformation and failure mode of the roof is a combination of bending and torsion, with the key failure area located at the left front of the cave entrance. The current state of deformation in the cave’s roof indicates it is in the mid-term accelerated change stage. These findings offer a reference for the stability analysis of other similarly complex caves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cave temples, as valuable cultural heritage, embody unique historical, cultural, artistic, and social value. However, as large and immovable stone artifacts, caves have been subjected to long-term impacts from both natural factors and human activities. As a result, many caves have experienced varying degrees of instability and damage, which have progressively worsened over time1,2,3. Therefore, conducting in-depth studies on the mechanisms of cave deformation and failure, as well as assessing their current stability status, is of critical importance for the preservation of these significant cultural assets.

With the rapid development of computer technology, numerical simulation methods have been widely applied in the study of cave chamber stability. Due to their ability to effectively reflect and simulate the three-dimensional morphology of caves, numerical simulations have gradually become an indispensable tool for solving stability issues in caves with complex engineering structures and boundary conditions. For example, Gao et al.4 established a 3D numerical model of the Longyou Cave group to assess the stability of the surrounding rock mass. Wang5 used numerical simulation methods to explore the development patterns of rock mass stability in the Baizikli Grottoes under different evaluation conditions. Lu6 constructed a finite element model of the Yungang Grottoes’ pillars to analyze their stability during the excavation phase. Li7 used finite difference software to model the Jinta Temple Grottoes and identified areas of greatest stress concentration. Zhang8 employed numerical simulations to evaluate the rock safety of caves No. 1 and No. 2 at the Yungang Grottoes. Similarly, Li et al.9 used numerical simulations to examine the stability of caves No. 5–13 at the Yungang Grottoes under weathering effects and identified potential areas of instability in the rock mass. Additionally, Chen and Guo et al.10,11,12 applied numerical simulation methods to study the stability of the Mogao Grottoes under tourist loads and seismic loads.

Despite numerous studies, there are still limitations in the numerical simulation work on cave stability. Most studies rely on built-in geometries provided by numerical simulation software, constructing finite element models through simple geometric transformations13,14. This method is suitable for relatively simple models, but it is difficult to apply to caves with complex morphologies. As a result, in current numerical analyses of cave stability often involve simplifying the cave’s geometry into regular shapes during model construction, which inevitably introduces discrepancies between simulation results and actual conditions. To ensure the reliability of numerical analysis, it is essential to make the constructed models as consistent with reality as possible.

In recent years, with the rapid development of 3D laser scanning and digital photogrammetry, cultural heritage preservation has entered a digital and information-driven era15,16. Reverse modeling based on 3D laser scanning point cloud data can generate accurate geometric information, providing a reliable foundation for numerical simulations17,18,19. For example, Andrey V et al.20 used 3D laser scanning technology to establish a 3D model of the Shabolovka tower in Moscow. Li et al.21 used 3D laser scanning to establish a finite element model of the painted sculptures in the Mogao Grottoes, studying their dynamic response to seismic forces. Rolin et al.22 used 3D laser scanning to obtain point cloud data of the spire of the Cathedral of Senlis, France, and constructed its finite element model through parametric modeling. Lin et al.23 obtained a complete and real model of the Great Wild Goose Pagoda through a method of multi-scan point cloud hierarchical registration for 3D reconstruction. Although reverse modeling based on 3D laser scanning point cloud data has been successfully applied to complex artifacts, its application in cave stability research remains relatively limited. Therefore, using 3D laser scanning technology to achieve refined modeling of complex caves holds great significance for advancing the study of cave stability.

Moreover, in most existing studies, cave chambers were directly excavated from the original rock mass and are in close contact with the surrounding rock without any infill. However, the roof of Yuanjue Cave in the Dazu Rock Carvings is supported by a combination of the original rock mass and infilled strip stones, making its boundary support conditions more complex compared to other caves. Additionally, the cave chambers studied so far are generally densely excavated, with smaller spans and depths for individual chambers. For example, in the aforementioned study of the Mogao Grottoes, the maximum span was 4.4 m, and the maximum depth was 6.6 m; in the study of the Baizikli Grottoes, the maximum span and depth were both 6 m. In contrast, Yuanjue Cave has a span of 9.55 m and a depth of 12.13 m. From a structural mechanics perspective, larger spans and depths create more unfavorable conditions for the roof’s stress and deformation.

In light of this, this study focuses on Yuanjue Cave of the Dazu Rock Carvings. Using point cloud data obtained through 3D laser scanning, a refined 3D numerical model was constructed to accurately represent the cave’s complex morphology, geological structures, and support conditions. By combining numerical simulations with field monitoring data analysis, the study systematically investigates the stress-deformation characteristics of the cave’s roof and the factors influencing its stability. The deformation and failure modes of the roof, as well as the key areas, were identified, and the current stability state of Yuanjue Cave was assessed. The findings provide scientific evidence for future reinforcement of the cave’s roof and offer an important reference for stability studies of other similarly complex cave systems.

Methods

Background of the study object

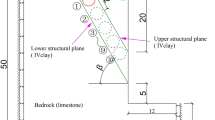

The Dazu Rock Carvings are located in Dazu District, Chongqing, and represent the pinnacle of world cave art from the 9th to the 13th centuries. Known as the “final monument in the history of cave art,” the carvings were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List on December 1, 1999. Yuanjue Cave is the largest cave sculpture in the Dazu Rock Carvings. Inside the cave, the stone carvings are intricately detailed and exquisitely shaped, with a delicate and flowing appearance, as shown in Fig. 1. The spatial shape of Yuanjue Cave is nearly rectangular. The entrance passage is approximately 6.5 m long, 1.6–2.4 m wide, and 3.8–4.4 m high. Inside the cave, the maximum height is 6.02 m, the maximum width is 9.55 m, and the depth is 12.13 m. The profile of the cave’s dimensions is shown in Fig. 2.

The self-weight reaction of the rock mass in the roof of Yuanjue Cave is primarily supported by two components: the strip stones beneath the roof and the original rock mass. The roof boundary is divided into the “original rock boundary” formed by the original rock mass and the “strip stone boundary” formed by the supporting stones. The “original rock boundary” is consolidated with the surrounding rock of the same strata, occupying about half of the roof’s boundary. The “strip stone boundary” consists of intact load-bearing stones and fractured broken stones, which occupy the other half of the roof’s boundary, as shown in Fig. 3.

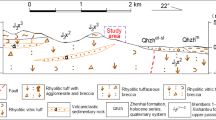

Due to the topographical feature of three exposed surfaces in Yuanjue Cave, numerous unloading fractures have developed in the surrounding rock mass. Through field surveys and 3D scanning, as well as an analysis of the spatial positions and orientations of the fractures, a total of 13 fractures were identified around Yuanjue Cave, labeled as J-01, J-07, J-10, J-14, L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, L6, L7, L8, and L9. Most of these fractures are primarily distributed within the sculpture strata, with only the L6 fracture located in the roof strata, cutting through the southwestern corner of the entire roof of Yuanjue Cave. The planar distribution of the fractures is shown in Fig. 4.

Yuanjue Cave in the Dazu Rock Carvings is situated in a fluvial-lacustrine sedimentary environment, where the rock layers are primarily exposed in horizontal formations, with alternating layers of packsand and mudstone. Through engineering drilling and laboratory testing, the surrounding rock of Yuanjue Cave has been divided into 15 layers, as shown in Fig. 5. Due to the unique stratigraphic structure of Yuanjue Cave, there is a layer of lower strength stratum beneath the entrance of the cave. After long-term differential weathering, this layer has weathered and eroded at a faster rate than the layers above and below it. As a result, a cavity with a certain depth has formed at this layer, as shown in Fig. 6.

Over the centuries, under the continuous influence of natural forces and various deterioration factors, the strip stones beneath the roof of Yuanjue Cave have gradually broken down, and the rock mass at the bottom of the roof has experienced ongoing peeling. This has posed a significant threat to the safety and stability of Yuanjue Cave. Field inspections of the strip stones beneath the roof of Yuanjue Cave revealed that some of the strip stones have developed compressive fractures. These fractured strip stones are mainly concentrated in the front section of the cave chamber, with a trend of further development towards the rear. The characteristics and distribution of the fractured strip stones are shown in Fig. 7. After the excavation of Yuanjue Cave, stress redistribution occurred within the rock mass. Under the influence of additional loading and long-term weathering, varying degrees of peeling damage have developed at the bottom of the roof, as shown in Fig. 8.

Numerical simulation

Numerical simulation is an effective tool for addressing complex deformation and failure problems in geotechnical engineering, and the accuracy of the model is crucial for the reliability of the results. To ensure the precision of numerical analysis, the constructed model must closely match the actual conditions. Therefore, in light of the limitations of existing studies and the unique characteristics of Yuanjue Cave in the Dazu Rock Carvings, this numerical simulation of deformation and failure mechanisms focuses on addressing the following issues:

(1) To address the current issue of low model refinement, which fails to reflect the true morphology of the cave, this study utilized point cloud data from 3D laser scanning of the excavation area. The refined 3D geological model of Yuanjue Cave in the Dazu Rock Carvings was constructed using software such as Autodesk ReCap, 3DReshaper, Geomagic Studio, Rhino, and Flac3D. This model not only restores the actual morphology of Yuanjue Cave as accurately as possible but also captures the three-sided exposed topographical characteristics of the surrounding rock mass.

(2) Given the complex stratigraphy of Yuanjue Cave and the highly developed surrounding fractures, the model stratigraphy was divided into groups in Rhino software based on the elevation of each layer, following preliminary stratigraphic surveys and fracture investigations. The fractures were then segmented in Rhino according to their planar positions and stratigraphic locations. The specific modeling process is shown in Fig. 9.

(3) To address the complex support conditions of Yuanjue Cave’s roof, field investigations were conducted to determine the geometry and spatial position of the infilled strip stones between the roof and the underlying bedrock. Based on the results of these investigations, the strip stones were grouped and modeled according to specific lengths, thereby simulating the effect of the support strip stones on the stability of Yuanjue Cave’s roof. Due to the relatively fewer strip stones on the right side of the cave entrance, they were modeled as a single group with a length of approximately 1 m. The left side of the entrance is filled with strip stones (Fig. 7), which were grouped in segments of 0.5 m in length. From the entrance to the back of the cave, a total of 26 groups were formed, covering approximately 13 m in length. Similarly, considering the cavity development beneath the entrance of Yuanjue Cave, based on field investigations, a 10 m wide and 1.3 m thick area at the cavity level was selected, and the cavity was divided into seven groups with a depth increment of 0.5 m.

Using the above 3D modeling scheme, a refined 3D geological model of Yuanjue Cave was constructed, incorporating the complex stratigraphy and fracture distribution, as shown in Fig. 10. Based on this model, a refined 3D geological model including the strip stone blocks and cavity was constructed according to the grouping scheme of the strip stones and cavity. The grouping of the cavity and strip stones is illustrated in Fig. 11. The overall model dimensions are 58.05 m × 47.33 m × 31.51 m, with a total of 1,719,093 elements. The model contains five artificially cut boundaries, with the bottom boundary subjected to fixed constraints and the side boundaries subjected to normal constraints. After the constraint boundary of the model is established, the linear elastic model is firstly adopted to carry out self-balancing under the gravity field condition. Then, the calculation is carried out in the elastoplastic phase of the Mohr-Coulomb model.

Previous research has shown that the surrounding rock mass of Yuanjue Cave is generally stable, and the stability of the cave mainly depends on the stability of its roof24,25. The strip stones as a support structure for the roof has an important influence on the stability of the roof26. Additionally, based on field investigations, the cavity beneath the entrance of Yuanjue Cave may also affect the stability of the roof. Therefore, considering the local fractures in the supporting strip stones of the roof and the gradual development of the cavity beneath the cave, the bearing and failure conditions of the strip stones were generalized into two forms: intact load-bearing strip stones and broken strip stones that no longer provide support. The null model in the FLAC3D numerical analysis software was used to simulate the state of broken strip stones and cavity depth development. For the simulation of cavity depth development, the cavity is gradually set as a null model from the inside out to simulate the increasing depth of the cavity. Since each group of cavities is 0.5 m, the depth of the cavity increases by 0.5 m with each simulation. The development of the cavity is illustrated in Fig. 12. For the simulation of broken strip stones: The broken strip stones are set as void models to simulate the gradual development of the broken strip stone length. Since each group of strip stones is 0.5 m, the broken strip stone length extends by 0.5 m with each simulation. The development of broken strip stones is illustrated in Fig. 13.

During the numerical simulation process, vertical displacements at four corner measurement points above the roof of Yuanjue Cave, as well as the distribution of maximum principal stress in the roof, were monitored. Two additional measurement points were set on either side of the L6 fracture to monitor the trend in the width of the fracture. The locations of all monitoring points are shown in Fig. 14.

The lithological parameters of this simulation are determined by taking rock samples from on-site drilling. The execution of the rock mechanics tests are carried out by the YZW100 mechanical testing system, according to the standard for test methods of engineering rock mass (GB/T 50266-2013). Considering the impact of drilling on the cultural relics, sampling was carried out at three locations surrounding the Yuanjue Cave, at a certain distance from each other (sampling locations are indicated in Fig. 4). The specific stratigraphic parameters are shown in Table 1.

Field monitoring

Stress monitoring equipment (BGK-4800) was installed on the temporary support columns inside Yuanjue Cave to monitor changes in the contact pressure between the support columns and the roof. By comparing the support force data from different locations, the deformation of the cave roof was analyzed. A total of nine measurement points (Y1 to Y9) were set up for support force monitoring. Additionally, an automatic laser distance measurement system (the testing accuracy is 0.1 mm and the testing distance is 600 mm) was installed on the temporary supports of the roof to monitor peeling of the roof’s inner surface. By comparing the peeling data from different parts of the roof’s inner surface, the uneven stress distribution at the bottom of the roof was analyzed. A total of eight measurement points (W1 to W8) were set up for peeling monitoring. The specific locations and field arrangements of these measurement points are shown in Fig. 15. For ease of description and comparison, the measurement points were grouped according to their spatial relationships as follows:

(1) Measurement points on the left side of Yuanjue Cave: Y2, Y6, Y3, Y8; W1, W2, W3, W4.

(2) Measurement points along the central axis of Yuanjue Cave: Y1, Y7; W5, W6, W7.

(3) Measurement points on the right side of Yuanjue Cave: Y4, Y5, Y9; W8.

Results

Impact of cavity depth on roof deformation and failure

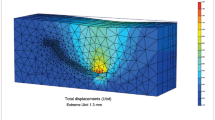

The cloud and vector diagrams of vertical displacement in the rock mass at the entrance area of Yuanjue Cave under different cavity depths are shown in Fig. 16. Based on the numerical simulation results, the displacement curves of roof measurement points Y6 and Y9 at the front side of the roof as a function of cavity depth were plotted, as well as the vertical displacement difference between the front measurement points (Y6, Y9) and the rear measurement points (Y8, Y10), as shown in Figs. 17 and 18, respectively.

(1) As shown in Fig. 16, as the cavity depth increases, the extent of its influence on rock mass deformation in the entrance area of Yuanjue Cave gradually expands, and the settlement of the rock mass above the cave entrance significantly increases.

(2) Fig. 17 shows that with increasing cavity depth, the vertical displacement of measurement points Y6 and Y9 on both sides of the cave entrance also increases continuously, and their rate of change gradually increases with the depth of the cavity. However, the overall values remain relatively small.

(3) As indicated in Fig. 18, the vertical displacement at the front and rear measurement points of the roof differs. With increasing cavity depth, the vertical displacement difference between the front and rear of the roof gradually increases, and their rate of change also grows with increasing cavity depth, though the overall values remain relatively small.

Impact of broken strip stones on roof deformation and failure in Yuanjue Cave

The cloud and vector diagrams of vertical displacement in the roof of Yuanjue Cave under different lengths of broken strip stones are shown in Fig. 19. Based on the numerical simulation results, the displacement curves of various roof measurement points and the width of the L6 fracture as a function of the length of broken strip stones were plotted, with Y8 and Y10 measurement points used as examples, as shown in Figs. 20 and 21.

(1) As shown in Fig. 19, as the length of the broken strip stones increases, the vertical displacement of the roof in Yuanjue Cave continues to increase, and the uneven settlement becomes progressively more severe. The inclined and bent area in the left front part of the roof expands, and the roof shows a tendency to tilt and overturn towards the left front side of the cave entrance.

(2) Figs. 20 and 21 indicate that as the length of the broken strip stones increases, the vertical displacement at the various roof measurement points and the width of the L6 fracture both increase. The increase process can be roughly divided into three stages: an initial steady change stage when the broken strip stone length is less than 4 m, a mid-term accelerated change stage when the length is between 4 m and 11 m, and a late rapid change stage when the length exceeds 11 m.

(3) Compared to the impact of cavity depth on the uneven deformation of the front part of the roof, the vertical displacement caused by broken strip stones is several orders of magnitude larger than that caused by cavity depth.

To determine the trend of uneven deformation in the roof as a function of the length of the broken strip stones, the vertical settlement differences between the left measurement points (Y6, Y8) and the right measurement points (Y9, Y10) were plotted as a function of broken strip stone length, as shown in Fig. 22.

(1) The settlement values at the left roof measurement points Y6 and Y8 are greater than those at the right points Y9 and Y10, indicating that the roof is tilting towards the left side of Yuanjue Cave (the side with the infilled strip stones). As the length of the broken strip stones increases, the settlement difference between the left and right measurement points continues to grow, and the degree of tilting intensifies.

(2) During the initial stage of strip stone breakage, the front part of the roof tilts more rapidly than the rear part. However, as the length of the broken strip stones continues to increase, the forward tilting gradually slows, while the rear tilting begins to accelerate significantly. In the early stage of strip stone breakage, the settlement difference between the left and right measurement points at the front is significantly greater than that between the rear measurement points.

The relationship between roof peeling and uneven stress deformation in Yuanjue Cave

The samples obtained from the three drilling locations were subjected to Brazilian splitting tests under both dry and saturated conditions, as shown in Fig. 23. Figure 24 shows the tensile strength of the rock mass at different depths in the Yuanjue Cave area under dry and saturated conditions (averaged from the three sampling points). To show the tensile regions and the magnitude of tensile stress at the bottom of the roof, Fig. 25 displays the distribution of maximum principal stress in the roof of Yuanjue Cave under varying lengths of broken strip stones. The negative region is caused by compression due to the contact between the roof and the strip stones, and is unrelated to the tensile region at the roof.

(1) As shown in Fig. 24, changes in moisture content significantly affect the tensile strength of the rock. The tensile strength in saturated conditions is markedly lower than that in dry conditions, and the closer the rock is to the surface, the lower the tensile strength, with the lowest value being less than 0.25 MPa.

(2) Fig. 25 shows that the bottom surface of the roof in Yuanjue Cave is under tensile stress, and as the length of the broken strip stones increases, the maximum principal stress (tensile stress) at the bottom surface of the roof also gradually increases. The maximum value has already exceeded the tensile strength of the surface rock in saturated conditions (0.25 MPa), and the region of concentrated tensile stress shifts from initially being above the cave entrance to progressively moving towards the left front side of the cave entrance.

Integrity status of Yuanjue Cave roof

The support force monitoring was conducted at a frequency of once per minute, with data collected from April 8, 2019, to June 26, 2019. The dataset includes a total of 113,760 data points from nine stress sensors. The monitoring data for the support force measurement points on the roof of Yuanjue Cave are presented in Fig. 26.

As shown in Fig. 26, the monitored support force values for the roof of Yuanjue Cave exhibit relatively small overall variations. Based on the roof area and thickness combined with the average density of the rock, the total weight of the roof is estimated to be approximately 570 tons. The sum of the maximum support forces at all measurement points is about 7.7 tons, which is less than 2% of the total weight of the roof. This indicates that the roof of Yuanjue Cave remains stable overall and that the primary support force is provided by the existing boundary conditions.

According to the data from the support force monitoring points, the monitored values showed minimal variation throughout the day. Therefore, the average daily monitoring data were calculated to create a new daily monitoring value series for each measurement point. After this processing, the support force data for the roof measurement points formed nine synchronized and continuous time series. To explore the interactions between support force variations at different roof measurement points and to assess the overall integrity and continuity of deformation in the roof of Yuanjue Cave, a correlation analysis was conducted on the nine time series formed by the support force data from each measurement point.

For sequences with nonlinear relationships that do not follow a normal distribution, Spearman correlation analysis is typically used to assess their correlation27. The Spearman correlation analysis involves arranging the sequence \(X=\left\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\ldots ,{x}_{n}\right\}\) in ascending or descending order to obtain the sorted sequence \(A=\left\{{a}_{1},{a}_{2},\ldots ,{a}_{n}\right\}\). The position of each element \({x}_{i}\) in sequence \(A\) is denoted as \({r}_{i}\), referred to as the rank of element \({x}_{i}\), resulting in the rank sequence \({R}_{X}\) of sequence \(X\). Another sequence \(Y=\left\{{y}_{1},{y}_{2},\ldots ,{y}_{n}\right\}\) is processed in the same way to obtain the sorted sequence \(B=\left\{{b}_{1},{b}_{2},\ldots ,{b}_{n}\right\}\), which gives the rank sequence \({S}_{Y}\) of sequence Y. The rank difference sequence \(D=\left\{{d}_{1},{d}_{2},\ldots ,{d}_{n}\right\}\) is obtained by subtracting the corresponding ranks of the two sequences. The Spearman correlation coefficient \(\rho\) is then calculated using the Eq. (1):

where \(n\) is the number of points in the sequence, and \(\rho\) is the Spearman correlation coefficient.

The time series of support force measurement points on the roof of Yuanjue Cave are represented as \({Y}_{n}(n=1,2\ldots 9)\), to quantify and evaluate the interactions between the support force measurement points of the roof. The correlation heatmap of the time series between support force measurement points on the roof of Yuanjue Cave is shown in Fig. 27.

(1) The correlation between the support force measurement points on the roof of Yuanjue Cave is relatively strong. Except for point Y5, which has a lower correlation coefficient with the other points, the correlation coefficients between all other measurement points are greater than 0.6, with a maximum value of 0.879. This indicates that, except for point Y5, the region enclosed by the other measurement points on the roof has good overall integrity and strong deformation continuity. The lower correlation of point Y5 with the other points is due to the fact that fracture L6 on the roof separates point Y5 from the others, thereby weakening its association with the rest.

(2) Whether on the left or right side of Yuanjue Cave, a trend is observed where the correlation with the front measurement points decreases as the distance from the cave entrance increases. Additionally, the correlation between points Y7 or Y5 and Y6 also gradually decreases with increasing distance from Y6. This suggests that the continuity of deformation in the roof of Yuanjue Cave gradually strengthens from the inside to the outside and also strengthens from the right rear to the left front.

Development trend of uneven deformation in the roof of Yuanjue Cave

Analysis of the stability and overall integrity of Yuanjue Cave’s roof indicates that the roof has good integrity, strong deformation continuity, and is in a stable state. Therefore, to determine the overall stress and deformation trend of the roof, an analysis was conducted on the variation of the support force differences at different roof measurement points recorded at the same time each day. The difference curves for each measurement point were linearly fitted over time, and the slope of the fitted line was used to understand the overall change trend of the differences between measurement points, thus preliminarily determining the development trend of uneven deformation in the roof. Since the process of calculating differences between measurement points and fitting is similar for all points, only the fitting results for a subset of measurement points are presented here for brevity, as shown in Fig. 28.

As shown in Fig. 28, the variation curves of the differences in support force at each measurement point on the roof of Yuanjue Cave are relatively small and overall stable. However, based on the fitted lines, it can be observed that the difference curves exhibit a certain trend of development, and the slopes of the fitted lines for different measurement points vary, indicating that uneven deformation has occurred in the roof of Yuanjue Cave. The remaining support force measurement points were analyzed in the same way by calculating differences with other points and fitting. The fitted slopes of the differences between each measurement point (reflecting the overall development trend of uneven stress deformation) and their distance gradients (indicating the intensity of uneven stress deformation development in different regions) are presented in Table 2.

(1) Compared to the support force measurement points along the central axis and on the right side of the roof, the slopes of the difference curves for the measurement points on the left side of the roof are generally the largest. This indicates that the uneven deformation on the left side of the roof changes more significantly over time compared to the central axis and the right side. The reason is that the left side of the roof is supported by strip stones, while the right side is primarily supported by the original rock mass. When the strip stones break, they have a greater impact on the settlement and deformation of the left side of the roof. This finding is consistent with the numerical simulation results shown in Fig. 19, where the uneven deformation on the left side of the roof is significantly greater than that in the central and right parts as the supporting strip stones continue to break.

(2) The slope of the variation in the difference between the support force measurement points on the left side of the roof over time shows the following pattern: Y8 − Y6 > Y8 − Y3 > Y8 − Y2, while the slope gradient shows Y3 − Y6 > Y2 − Y6 > Y8 − Y6. This indicates that the difference in uneven deformation between the inner and outer temporary support points on the left side of the roof increases gradually from the inside to the outside over time, and the development of differential deformation also tends to intensify from the inside to the outside. The most pronounced uneven deformation occurs in the region between measurement points Y6 and Y3. This finding is consistent with the numerical simulation results in Fig. 19, which show a trend of the roof tilting towards the left front side of the entrance as the supporting stones continue to break. The region between points Y6 and Y3 also aligns closely with the key area of deformation and failure identified in the numerical simulation.

(3) The absolute value of the slope of the variation in the difference between the support force measurement points on the right side of the roof over time shows the following pattern: ∣Y5 − Y4∣ > ∣Y5 − Y9∣ > ∣Y4 − Y9∣, and the slopes of Y5 − Y4 and Y4 − Y9 have opposite signs. This indicates that the most pronounced uneven stress development occurs in the region between measurement points Y5 and Y4 on the right side of Yuanjue Cave, suggesting that the L6 fracture located between points Y4 and Y5 has expanded. This finding is consistent with the numerical simulation results shown in Fig. 21, where the width of the L6 fracture increases continuously as the length of the broken strip stones increases.

(4) The slope of the variation in the difference between the internal support force measurement point Y8 on the left side of the roof and the central measurement point Y5 and front measurement point Y9 on the right side is also relatively large. This indicates that, in addition to uneven deformation on the left side, there is also a trend of differential deformation development in the interior, central, and front-right sections of the roof. This finding is consistent with the numerical simulation results in Figs. 16 and 19, which show that the roof of Yuanjue Cave bends towards the front entrance under the influence of the cavity, while also tilting towards the left front side under the condition of broken strip stones.

Development trend of uneven peeling in the roof of Yuanjue Cave

The peeling monitoring was conducted at a frequency of once per hour, with data collected from November 28, 2018, to May 28, 2021. The dataset includes a total of 65,498 data points from eight laser displacement sensors. The monitoring data for peeling on the roof of Yuanjue Cave are shown in Fig. 29. To explore the correlations between changes in peeling at different roof measurement points and assess the uneven stress distribution at the bottom of the roof, a correlation heatmap was generated for the peeling measurement points using the same analysis method as for the support force measurements. The resulting heatmap is presented in Fig. 30.

(1) As shown in Fig. 29, over time, the extent of peeling at measurement points W1 and W8 gradually exceeds that of other measurement points. This indicates that the peeling development in the areas around points W1 and W8 is more severe compared to other areas.

(2) Fig. 30 shows that the correlation between the peeling measurement points on the roof of Yuanjue Cave is relatively strong, with correlation coefficients between all points greater than 0.7, reaching a maximum of 0.985.

(3) Among the measurement points on the left side of the roof, the correlation between W1 and W2, as well as between W3 and W4, is relatively high, while the correlation between W2 and W3 is lower. This is consistent with the field observation that the length of the broken strip stones extends to between W2 and W3. This suggests that the breakage of the supporting strip stones has caused uneven stress on the left side of the roof, resulting in a lower correlation between the peeling in the front and rear regions.

(4) The correlation between three pairs of measurement points along the left side and central axis of the roof (W1-W5, W2-W6, W3-W7) shows a trend where the farther the points are from the cave entrance, the lower the correlation between the lateral points. This indicates that the uneven peeling changes are more pronounced closer to the entrance, between the left side of the roof and the central axis.

Based on the overall seepage condition of Yuanjue Cave’s roof observed during the field survey (Fig. 31), the reason for the severe peeling at measurement point W8 is primarily that it is located within the seepage zone of fracture L6, where rainwater infiltration has accelerated the peeling process. Since the roof seepage is mainly concentrated in the right rear (southwest corner) of Yuanjue Cave, while other areas are affected by condensation water leading to weakened rock mechanical properties. It can be considered that the condensation environment within Yuanjue Cave is uniform. Therefore, the reason for the more severe peeling development at measurement point W1 compared to other points is attributed to uneven stress and deformation of the roof. To consider the development of uneven peeling between measurement points on the roof under the same environmental conditions, the analysis was conducted by excluding measurement point W8. Using the same analysis method as for the support force measurement points, the differences between the peeling data from each point were calculated and fitted. The fitted slopes of these differences (reflecting the overall development trend of uneven peeling) and their distance gradients (indicating the intensity of uneven peeling development in different regions) are presented in Table 3.

(1) On the left side of Yuanjue Cave’s roof, the absolute value of the slope gradient for changes in the differences between peeling measurement points over time follows the pattern: ∣W1 − W2∣ > ∣W1 − W3∣ > ∣W1 − W4∣. For the central axis measurement points, it follows the pattern: ∣W5 − W6∣ > ∣W5 − W7∣. For the left side and the central axis, the pattern is: ∣W1 − W5∣ > ∣W2 − W6∣ > ∣W3 − W7∣. Whether longitudinally or laterally, the absolute value of the slope gradient for the differences between measurement points on the left side and the central axis of the roof shows the characteristic that “the closer to the cave entrance, the greater the difference between the inner and outer areas.” This indicates that the closer to the front side of Yuanjue Cave’s entrance, the more severe the uneven development of peeling in the roof becomes. Furthermore, the closer to the front side of the entrance, the more pronounced the differential peeling development between the left side and the central part.

(2) Among the peeling measurement points on Yuanjue Cave’s roof, the slope distance gradients of the differences for points W1, W2, W5, and W6 are generally greater than those for the other points, both longitudinally and laterally. This indicates that the region enclosed by points W1, W2, W5, and W6 experiences the most intense differential peeling development, both in the longitudinal and lateral directions.

Discussion

This study investigated the deformation and failure mechanism of Yuanjue Cave’s roof by combining numerical simulations with field monitoring data analysis. The influence of broken strip stone length and cavity depth on the stress, deformation, and stability of the roof was analyzed, and the current stage of roof deformation development was determined.

It was discovered through numerical simulation that changes in cavity depth have a certain impact on the stress, deformation, and stability of the roof of Yuanjue Cave. As the cavity depth increases, the rock mass above the cave entrance continues to settle, resulting in an overall forward tilting deformation of the roof (Fig. 16). The front part of the roof near the entrance settles faster than the rear part, causing bending deformation between the front and rear of the roof, and this trend becomes more pronounced with increasing cavity depth (Fig. 17). When uneven settlement deformation occurs between the front and rear of the roof, the stress on the supporting strip stones near the front side of the cave entrance increases, leading to compressive fractures occurring first in these strip stones. This finding is consistent with the field investigation, where fractured strip stones were found to be concentrated near the front of the entrance (Fig. 7). Through numerical simulation, it was also found that the breakage of the strip stones causes uneven deformation in the roof of Yuanjue Cave, leading to tilting towards the left front side of the cave (Fig. 19). As the length of the broken strip stones increases, the uneven deformation intensifies (Figs. 20 and 21). The asynchronous tilting of the front and rear measurement points of the roof results in not only bending deformation but also torsional deformation (Fig. 22). Therefore, the deformation failure mode of the roof is a combination of bending and torsion, with the key failure area located in the left front section of Yuanjue Cave. Since the supporting strip stones are in direct contact with the roof, providing structural support, their breakage directly impacts the stability of the roof. Compared to the cavity, which affects the roof stability indirectly through the rock mass around the cave entrance, the impact of broken strip stones on roof stability is much more significant. Therefore, an increase in cavity depth is merely the trigger for roof instability, whereas the breakage of supporting strip stones is the primary controlling factor for roof instability and failure. Due to its unique depositional and lithification process, the roof of Yuanjue Cave contains relatively thin bedding planes. Long-term weathering has continuously reduced the strength of the surface layers and the cementation strength between these thin layers. Sandstone, being a product of clastic particle accumulation and cementation, is sensitive to changes in strength when exposed to moisture. When water infiltrates from outside the cave or condensation occurs inside, the moisture content of the surface rock of the roof increases, further reducing its mechanical properties. As the bottom surface of the roof is under tensile stress (Fig. 25), when the tensile stress in certain areas exceeds the tensile strength of the surface rock, laminar peeling occurs under its own weight (Fig. 8). Therefore, under identical rock properties and environmental conditions, the uneven stress deformation at the bottom of the roof can reflect the area of uneven peeling. It can be concluded that as the length of the broken strip stones increases, the area prone to peeling on the roof gradually shifts from above the entrance to the left front side of the cave entrance.

The development trend of uneven settlement in the roof of Yuanjue Cave can be derived from the changes in the temporary support forces over time, as shown in Fig. 32. Compared to field monitoring, the mechanical state in numerical simulations reflects more extreme conditions. However, both exhibit the same deformation development trend under the condition of strip stones broken. Therefore, the verification of field monitoring results against numerical simulation results focuses not on absolute values but primarily on comparing deformation development trends. It can be observed that the trend of uneven settlement derived from field temporary support force monitoring data is consistent with the uneven deformation trend obtained from numerical simulations in Fig. 19, with both indicating a tilting and settlement towards the left front side of the cave entrance. The analysis of field monitoring data also confirms that the deformation and failure mode of the roof is a combination of bending and torsion, with the key area of deformation failure located at the left front side of the entrance to Yuanjue Cave. Based on the trend of peeling over time, combined with the previously analyzed relationship between roof peeling and uneven stress, the area enclosed by measurement points W1, W2, W5, and W6 is the region where uneven stress develops the fastest, as indicated by the red dashed line in Fig. 33. It can be seen that the area of the most intense uneven stress development, as derived from field peeling monitoring data analysis, is consistent with the maximum principal stress concentration area on the bottom surface of the roof obtained from the numerical simulation in Fig. 25—both are located in the left front part of Yuanjue Cave’s roof. The analysis of field peeling monitoring data also confirms that, under the same rock properties and environmental conditions, the uneven stress deformation at the bottom of the roof reflects the pattern of uneven peeling at the bottom of the roof.

The study found that the stability of the roof in Yuanjue Cave is primarily controlled by the breakage of the supporting strip stones. The development of vertical settlement of the roof and the width of the L6 fracture can be roughly divided into three stages as the length of the broken strip stones increases (Figs. 20 and 21):

①When the length of the broken strip stones is less than 4 m, the roof is in the initial steady change stage, where vertical settlement and fracture width increase slowly.

②When the length of the broken strip stones is between 4 m and 11 m, the roof enters the mid-term accelerated change stage, during which settlement and fracture width gradually increase at an accelerating rate.

③When the length of the broken strip stones exceeds 11 m, the roof reaches the late rapid change stage, characterized by a sharp acceleration in vertical settlement and fracture width.

Based on the principle of preventive protection, the length of the broken strip stones reaching 11 m can be used as a warning indicator that the roof is approaching instability, with 11 m identified as the critical length of the broken strip stones. Field investigations revealed that, under current conditions, the length of the broken strip stones is greater than 4 m but less than 11 m, with the furthest point reaching approximately 7 m, as shown in Fig. 34. Therefore, the deformation of Yuanjue Cave’s roof is currently in the mid-term accelerated change stage.

Combining the results from numerical simulations and field monitoring analyses, the deformation and failure development process of Yuanjue Cave’s roof is as follows: First, the development of cavity depth causes the rock mass near the cave entrance to tilt forward, resulting in differential deformation between the front and rear parts of the roof (bending deformation). Subsequently, the differential deformation between the front and rear parts of the roof increases the pressure on the strip stones at the front of the cave entrance, leading to their initial failure. As the supporting capacity of the crushed strip stones at the front entrance declines significantly, the forward tilting and differential deformation of the roof intensify. Next, due to the breakage of the front strip stones, the pressure on the rear strip stones continues to increase, resulting in a gradual expansion of the crushed strip stone area towards the rear of the cave, causing the roof to tilt towards the left front side (bending and torsional combined deformation). Finally, as the crushed strip stone area continues to expand, the stability of the roof of Yuanjue Cave progressively deteriorates. The process of instability and failure development for the roof is illustrated in Fig. 35.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Yao, X. & Zhao, F. A quantitative evaluation based on an analytic hierarchy process for the deterioration degree of the Guangyuan Thousand-Buddha grotto from the Tang Dynasty in Sichuan, China. Herit. Sci. 10, 1–18 (2022).

Claudio, A. & Vincenzo, M. Structural assessments of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. J. Cultural Herit. 13, 61–69 (2012).

Wang X. D. et al. Assessing the relative stability of the Mogao Grottoes using a rock mass quality classification approach. Ancient Underground Opening and Preservation: 249-256. (2015)

Gao, Q. et al. Stability analysis of the large ancient underground rock caverns in Longyou and the selection of maximum-security routes in the caverns (in Chinese). Rock. Soil Mech. 30, 2713–2721 (2009).

Wang X. Damage mechanism and stability analysis of grottoes (in Chinese). Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology; (2020).

Lu S. M. Columns’ Stability Analysis of Cave No.9 and No.10 in Yungang Grottoes (in Chinese). Shenyang Jianzhu University; (2018).

Li J. L. The Study of Stability and Reinforcement Measures on the Rock Mass of Jinta Grottos (in Chinese). Lanzhou University; (2012).

Zhang A. H. Three-dimensional finite element study on the stability of Caves 1 and 2 in Yungang based on strength reduction method (in Chinese). China University of Geosciences; (2008).

Li, T. Q., Dong, S. Y. & Zhou, T. Q. Numerical simulation analysis of stability of Yungang Cavern’s rock mass under weathering action. J. Nat. Disasters 21, 124–130 (2012).

Guo Z. Q. Stability analysis of dense caves and risk assessment of the dangerous rock body at the Southern area of Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang (in Chinese). Lanzhou University; (2018).

Chen, W. W. et al. Evaluation of Long-Term Stability of Mogao Grottoes Caves under Enhanced Loading Conditions of Tourists (Article). J. Perform. Constructed Facilities 32, 04018048 (2018).

Guo, Z. Q. et al. Seismic responses of the densely distributed caves of the Mogao Grottoes in China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 1335–1349 (2021).

Hemeda, S. PLAXIS 3D numerical analysis of complex geotechnical problems of colossal built heritage. Herit. Sci. 12, 1–18 (2024).

Hemeda, S. Engineering failure analysis and design of support system for ancient Egyptian monuments in Valley of the Kings, Luxor, Egypt. Geoenviron. Disasters 5, 1–24 (2018).

Sha, Y. T. et al. Research on the Intelligent Display of Cultural Relics in Smart Museums Based on Intelligently Optimized Digital Images. Computational Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 7077556 (2021).

Alkadri, M. et al. Investigating Surface Fractures and Materials Behavior of Cultural Heritage Buildings Based on the Attribute Information of Point Clouds Stored in the TLS Dataset. Remote Sens. 14, 410 (2022).

Wei, P. et al. Equal Proportion Reproduction Method of Grotto Based on Point Cloud. Int. Arch. Photogramm., Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2, 1215–1219 (2019).

Liu, S. & Bin Mamat, M. J. Application of 3D laser scanning technology for mapping and accuracy assessment of the point cloud model for the Great Achievement Palace heritage building. Herit. Sci. 12, 1–17 (2024).

An, L. et al. Diffusion Transformer for point cloud registration: digital modeling of cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 12, 1–12 (2024).

Andrey, V. L. et al. Laser scanning and 3D modeling of the Shukhov hyperboloid tower in Moscow. J. Cultural Herit. 16, 551–559 (2015).

Li, L. S. et al. Dynamic characteristics and seismic responses of painted sculptures of Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes (Article). J. Cultural Herit. 22, 1040–1048 (2016).

Rolin, R. et al. From point cloud data to structural analysis through a geometrical hBIM-oriented model (Article). J. Comput. Cultural Herit. 12, 1–26 (2019).

Lin, X. H., Xue, B. & Wang, X. Q. Digital 3D Reconstruction of Ancient Chinese Great Wild Goose Pagoda by TLS Point Cloud Hierarchical Registration. J. Comput. Cultural Herit. 17, 1–16 (2024).

Meng, Z. G. et al. Numerical Modeling and Stability Analysis of Surrounding Rock of Yuanjue Cave. Geofluids 2021, 1–11 (2021).

Meng, Z. G. et al. Three-Dimensional Numerical Modeling and Roof Deformation Analysis of Yuanjue Cave Based on Point Cloud Data. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 1–13 (2020).

Men Z. G. Research on the Deformation Mechanism and Control Countermeasures of Yuanjuedong Grottoes Roof (in Chinese). China University of Mining and Technology (2021).

Russell, J. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient. Tbilisi State University (2012).

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.W. performed program design and wrote the manuscript, C.L. contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript, S.Y. contributed to data management; X.W. polished the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, C., Liu, C., Yan, S. et al. Stability study of complex caves: a case study of Yuanjue Cave in the Dazu Rock Carvings. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 183 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01730-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01730-x