Abstract

The building glazed tiles in ancient China are well known for their rich colors. Blue-glazed objects are especially valued for their rarity. However, little research has been conducted on them. In this study, we observed, tested, and analyzed nine blue building glazed tiles excavated at the archaeological sites at Yuanmingyuan Park (Summer Palace). The nine studied samples were found to be lead-glazed pottery with cobalt glaze material, and the firing temperature of the body was about 1000 °C. More importantly, the glaze showed high K and As, relatively high Ni and Ba, and small amounts of Bi and U. The results matched the characteristics of smalt imported from Europe. This research found a high content of Mn, indicating that the blue glaze was mixed with Chinese cobalt ore. Our research found that mixed cobalt material continued to be used in ceramics production in the Qing Dynasty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Yuanmingyuan, now called Yuanmingyuan Park (Summer Palace), was built during the Qing Dynasty’s Yongzheng (AD 1722–1735) period until the late Qing Dynasty. It became an important royal garden in the Qianlong (AD 1736–1796) period. Recently, the Beijing Institute of Archaeology implemented archaeological excavation work at Yuanmingyuan Park (Summer Palace), excavating numerous building tiles, especially coloured glazed building components.

Yellow, green, and turquoise glazes, which were used in royal palaces in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, have been extensively studied1. Some studies focused on production techniques1,2, coloration mechanisms1, and raw material sources [1.2], whereas others identified the glaze formula and the body origin based on court archives and craftsmanship standards from the Ming and Qing Dynasties2. Kang Baoqiang analysis turquoise glaze tiles from the Palace Museum and reveals the raw materials and manufacture. The glaze tiles of the turquoise glaze from the Forbidden City is considered to be in the SiO2- PbO -K2O system1. Kang Baoqiang studied the origin and production era of yellow glazed tiles excavated at the Shenwumen Gate of the Forbidden City. Similarities in terms of tile bodies’ mineral phases found in the Gate of Divine Prowess tiles and Qing Dynasty samples, also from the Forbidden City suggest that the former may also come from Mentougou Beijing2. Kang Baoqiang analysed the composition of yellow glazed tiles from the Yongzheng Qianlong Jiaqing periods AD 1723–1820), It is believed that the PbO content in the glaze tends to decrease and the SiO2 content tends to increase3. Some investigated the discoloration mechanism of building glaze unearthed at the archaeological sites in Yuanmingyuan Park and found they experienced a second high-firing4.

Blue building glazes that use cobalt as the coloration material are rarely seen in excavations, and few studies have examined them. Blue building glaze tiles be excavated in Yuanmingyuan Park (Summer Palace) and the Temple of Heaven. The source of the cobalt in these glazes is disputed. This research identified the composition and materials used in blue building glazed components from archaeological excavation sites at Yuanmingyuan Park5, especially the coloration materials and their source.

Methods

Samples

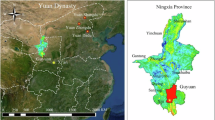

The samples used in this research were unearthed at the archaeological excavation sites in Yuanmingyuan Park, such as the Haiyantang (海晏堂) site, Yuanying Temple (远瀛观), the Birds Cage (养雀笼)6 site, and the Grand Palace Gate (大宫门) site. Nine samples were examined, including tube tiles, plate tiles, fish-scale tiles, and decorative components (Fig. 1). The scale bar represents 5 cm. The composition, firing temperature, and microstructure of their body plan to determine the firing process and the blue-glazed components’ raw materials were analyzed. The name of the laboratory is an abbreviation of the excavation site.

Microscope

A high-depth-of-field microscope is used for microscopic observation of the glaze and the body. Microscopes are commonly used to observe the glaze, the body and the glaze-glaze joints to obtain information on the thickness, colour and condition of the glaze layers and the composition of the body. The body microscope used this time is the VHX-5000 super depth-of-field 3D video microscope from Keens.

ED-XRF

The composition of the glaze and body was analyzed using an energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (ED-XRF), model XGT-7000, made by Horiba. The analysis conditions were as follows: Rh target, x-ray tube with a voltage of 30 kV and a current of 0.062 mA, and a signal acquisition time of 100 s, spot diameter 1.2 mm. The measurement is done from the glazed surface. All the surfaces of the testing area were cleaned with ethyl alcohol. The thickness of the glaze is between 200 μm and 400 μm, the body is more than 1000 μm. The spectrum analysis adopted the fundamental parameters method using a single reference material.

SEM

The glaze was analyzed using an SEM4000 field emission scanning electron microscope developed by CIQTEK and the Oxford energy spectrometer. The samples were tested using a backscattered electron detector and photographed with an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. Testing of glaze on resin-embedded samples using SEM.

Horizontal differential thermal dilatometer

The thermal expansion curves of the samples were measured using a horizontal differential thermal dilatometer (TA DIL 806). The sample dimensions for thermal expansion measurement were 10.0 mm × 5.0 mm × 5.0 mm. The test temperature ranged from ambient to 1100°C with an increasing speed of 7 K/min and an oxidative test atmosphere7. With regard to porcelain biscuits heated in a reducing atmosphere, its sintering temperature is lower than that of heating in an oxidising atmosphere, therefore, the choice of oxidising atmosphere8. YDGM166 analyzed only for body firing temperature.

Results

Chemical composition of the body

Table 1 shows the results of the nine samples. The results showed that the Al2O3 content in all nine samples is over 23%, with the majority being higher than 27%. This is a typical characteristic of sedimentary kaolinite9. Wanshuzaji (宛署杂记)10, written by Shen Bang in the Ming Dynasty, recorded that Ganzi soil, a coal-based kaolinite, a kind of sedimentary kaolin clay with a high impurity content, was the main material used in glazed tiles’ body. Kaolin contains varying amounts of potassium oxide, sodium oxide, iron oxide and magnesium oxide, depending on its origin. It was one of the most important raw materials used for ceramics in northern China since the Song dynasty (AD960–1279).

This finding indicated that the bodies of glazed components are made of Ganzi soil. This aligns with the historical records and is in accord with the other results regarding the Forbidden City and Yuanmingyuan2,11. It also indicates that the raw materials of the imperial palaces’ glazed tile during the Ming and Qing Dynasties may all come from Duizihuai Mountain, which is now called Mentougou Liuliqu, in Beijing12. Duan Hongying analyzed raw materials from Mentougou (Duizihuai Mountain) and glazed tiles’ body excavated from the Forbidden City. Comparison of the data from that article with the data measured by the author suggests that the raw material comes from the Mentougou Liuliqu11. The data in this study are similar to the raw materials taken from Mentougou for each constituent, Yuanmingyuan and the Forbidden City, as a royal building and glazed tiles of similar period of time and therefore presumably of the same origin of raw materials.

Body firing temperature

This study used re-sintering expansion to measure the samples’ firing temperature. The studied samples are YDGM166, YDGM129, and YYQL60. The results indicated that the firing temperature of these three samples was between 1000 °C and 1050 °C. Mullite was not detected by stereomicroscope, according to the low firing temperature measured by thermal expansion, and cannot be called porcelain. Through the use of a high-depth-of-field microscope (Fig.2), the glaze layer thickness ranges from 100 to 200 μm.

Table 2 shows the results of the nine samples. According to the results of the ED-XRF test, the blue glaze was high in lead. However, its lead content was significantly lower than that of the yellow building-glazed components. Comparing the yellow glazed components of the Yongzheng and Qianlong periods, it can be seen that the lead oxide content of the yellow components is between 59% and 66%. Simultaneously, the nine samples contained high K and Si, and their glaze layers belonged to the SiO2-PbO-K2O glass system. This K and Si content is much higher than those of yellow building glazed components. The high K and Si also appeared in the turquoise building glazed components. The potassium oxide of yellow glazed tiles is under 1% and the silicon oxide is between 21% and 30%. The potassium oxide of blue glazed tiles is between 7% and 12% and the silicon oxide is between 43% and 53%. The manufacturing process and composition of this glazed surface were investigated in a study of turquoise building fragments from the Yuan Dynasty unearthed in the Forbidden City1. Our research accepts this result, positing the perspective that the blue glaze was made into glass before glazing.

To identify the source and form of K in the nine samples’ cobalt blue glaze, a scanning electron microscope was used to observe the join of the body and the glaze and to measure the composition of the body, body–glaze join, and glaze surface. Because the thin glaze surfaces of these samples are difficult to measure, we selected three samples (HYT029, YYQL061, YYYG018) whose glazed surfaces are relatively thick.

From the electron image of the glazed tile is mainly glaze and body, in order to find Smalt’s particles, respectively, the body glaze and body–glaze join of composition testing (Fig 3–5). The composition test results ‘in Table 3 revealed that the content of K in the body of the three samples is low. Combined with the XRF test results, this shows that the content of K is 3% ~5% in the raw materials of the three samples’ bodies. This is significantly lower than that in the glaze join, whose K content is 7%~20%; that is, the K content in each sample is uneven. The K content is lower in the body than in the glaze surface, and that in the glaze surface is lower than in the body–glaze join. One of the reasons for the higher content of potassium oxide is produced by the reaction of the tile and glaze13, but the content of potassium oxide in both the glaze and the body–glaze join is higher than that in the body, so it is believed that the potassium oxide in the glaze comes from the glaze added during the production of the glaze. The samples also showed higher Co and lower Mn in the body–glaze join. These particles can be identified as residual pigment particles because the firing temperature was not sufficiently high14. The addition of lead oxide to the glaze lowers the firing temperature of the glaze Table 4.

a SEM image of the glaze–body join in sample HYT029 at 1000× magnification, showing the overall morphology of the glaze–body join. Blue lines indicate the boundaries of the glaze layer, the body–glaze junction, and the body. b SEM image of a selected region from HYT029 at 2000× magnification. c SEM image of a cross-section from test area. SEM scanning electron microscopy.

a SEM image of the glaze–body join in sample YYQL061 at 1000× magnification, showing the bonding relationship between the glaze and body. b SEM image of the same region in sample YYQL061 at 2000× magnification, revealing finer microstructural features. c SEM image of the cross-section from the test area. SEM scanning electron microscopy.

a SEM image at 150× magnification showing a broad view of the glaze–body join. Blue lines indicate the boundaries of the glaze layer, the body–glaze junction, and the body, clearly outlining the layered structure. b SEM image of region at 500× magnification, providing a closer look at the microstructural features of the join. c SEM image of a cross-section from the test area. SEM scanning electron microscopy.

Discussion

The Mn and Co content in the nine samples was compared to the exact content of blue and white porcelain in the Qianlong and Yongzheng periods, blue and white porcelain unearthed at the royal kiln factory in the Kangxi and Yongzheng period9,15, and blue and white porcelain unearthed at the Nandaku (南大库) site of the Forbidden City16 (Fig. 6). As shown in the Fig. 6, the slopes of the nine samples differ from those of the blue and white porcelain samples. The nine samples have low Mn and high Co. The MnO content is 0.34%~2.16%, and the CoO content is 1.33%~0.64%. From Figs. 7 and 8, we can see that glazed tiles are characterized by high cobalt and high manganese.

China’s local cobalt material is a kind of manganese ore associated with cobalt. As shown in the Fig. 6, blue and white porcelain samples of the Qing Dynasty used local cobalt material, and the MnO and CoO content is 0.3–3% and 0.1–0.5%, respectively. The samples from Yuanmingyuan Park are complex. The data indicate that the cobalt material used on the surface of the blue building glazed component from Yuanmingyuan Park was not a typical local cobalt material. From the box plots of Mn0 and CoO for the four types of cobalt materials, the cobalt materials on glazed tiles have a distinctly high Co.

Another characteristic of the nine samples is that the glaze has high Ni and As. The composition is not the same as that of local cobalt materials, which do not have As and Ni. It is similar to the cobalt ores in Europe17,18, which have As and Ni. The Ni-Co diagram (Fig. 3) shows that the content of Ni is positively correlated with Co. Figure 4 also indicates a positive correlation between Bi and Co. Finally, according to chemical compositions (wt%) of the glaze tiles’ glaze, it can be seen that some of the glazes contain Bi and U consistent with the composition of cobalt ores mined in Europe that are symbiotic with Bi2(CO3)O219.

Smalt is a vitreous cobalt material that originated in Europe20. The major component of European cobalt ore is Ni-Co-As-Bi(U), which turns to Ni-Co-As-Fe after firing13. Smalt is obtained after cobalt is fired into glass and ground. It is widely used as a pigment in paintings in Europe and is also found in architectural components and pottery ware21,22,23,24,25. From Fig. 9 and Fig. 10, it is believed that nickel oxide shows a positive correlation with cobalt oxide, and it is believed that they are consistent with cobalt sources, which is further hypothesized to be smalt.

Smalt-glazed coloured pottery from 17th-century Hungary has been documented in previous studies. A microanalytical investigation of six faience ware samples excavated from Sárospatak, northeastern Hungary, was conducted using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS)26. Yun Jihyeon analyzed the chemical composition of smalt pigments used in 10 large Buddhist paintings in the Joseon Dynasty using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Through analyses, the large Buddhist paintings in the Joseon Dynasty are divided into three smalt types (Table 4). Type A is a type with high As2O3, type B is a type with high BaO, and type C is a type with high PbO27.

The high K, As, and Ni (including Bi) found in the glazes of the nine samples here suggest that imported smalt may have been used in the blue building glazes from Yuanmingyuan Park. The retention of arsenic in the glaze may be related to the addition of lead oxide.

The importation of smalt has long been recorded. The Chronicle of the East India Company’s Trade with China documented importation during the Qing Dynasty; records from 1774 and 1792 explicitly mention it. Smalt was traded from 1774 to 1792, originally for 100 Liang silver per picul for the first class and 24 taels per picul for the second class. In 1792, the price was 11 Liang per picul. According to the import volume of smalt recorded in the trade statistics from 1859 to 1902, China’s Old Customs Historical Records, large quantities of smalt were imported at ports along the coastline from Tianjin to Xiamen21. It can be posited that there must have been many methods and situations for imported smalt.

Numerous studies have found that smalt was widely used as a pigment in Qing dynasty court paintings and as a raw material in producing ceramics and colour enamels28,29,30,31,32. Smalt was found as a pigment in Jianfu Palace, Cining Palace, and Shoukang Palace in the Forbidden City33. Two different kinds of smalt, for example, were found in the Jianfu Palace paintings. A polarizing microscope was used to observe glass smalt pigment in the paintings in the Linxi Pavilion in the Forbidden City33. Furthermore, smalt was used not only in royal palaces and gardens but also in nongovernment implements3. Tsinghua University collected colour-painted wooden statues of three Qing Dynasty Buddhas, and smalt was observed in their blue pigment by microscope. These statues were not made in court, indicating that smalt was widely used during the Qing Dynasty34,35,36.

China has a long history of using cobalt materials in ceramic production, from blue and white porcelain in the Tang Dynasty to the large-scale production of blue and white porcelain in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties37. Chinese craftspeople had accumulated significant experience in the use of cobalt materials. For these reasons, smalt was used to fire ceramics, and enamel is reasonable and possible38.

There are records regarding the use of smalt in firing ceramics. Gillan, a doctor in the Macartney Embassy of the British Mission to China during the Qianlong period, recorded the use of smalt in the production of ceramics in his Observations on the State on Medicine, Surgery, and Chemistry in China:

I was told that the raw material they used in the past was local cobalt, but now a large amount of smalt (a kind of glass powder made by mixing and melting one portion of cobalt ash commercially known as zaffre and two portions of flint powder) is shipped to them from Europe.

The records and research results indicate the common use of the smalt, which was imported in large quantities in the Qing Dynasty39. It is also a definite possibility that smalt was applied to make building glaze for royal palaces in Yuanmingyuan Park. First, traditional glaze tiles were typically coated with low-temperature lead-based glazes, whereas mid- to low-temperature glazes containing potassium oxide emerged at a comparatively later stage1. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, cobalt-based colourants—aside from their well-documented use in blue-and-white porcelain—were primarily found in Jilan glazes. These glazes were lead-free and exhibited relatively low cobalt content40. Second, blue glaze tiles in the Beijing region were not identified archaeologically until the Qing Dynasty. These specimens featured glazes containing both lead oxide and potassium oxide, along with a notably high concentration of cobalt, representing the earliest known instance of such a glaze composition.

The Mn content in the nine studied samples is between 0.34% and 2.16%. They contain high Co, typical in smalt, and high Mn, which is not typical in smalt.

As we know, smalt is made from European cobalt ore, which has low Mn as it is not the basic element of this kind of cobalt ore. We created a scatter plot for Mn and Co; the points stand for the Qing Dynasty blue and white porcelain and the nine samples (Fig. 6).

Based on the data and analysis, the nine samples have the characteristics of imported smalt and local cobalt materials. Thus, the glaze of nine samples from Yuanmingyuan Park is a mixture of imported smalt and local cobalt materials.

The Expense Record for the Construction of an Enamel Pagoda in the Ningshougong Palace.(照金塔式样成造珐琅塔一座销算底册):

配青色七斤八两, 每斤用顶元子二两,计十五两。洋青二两, 计十五两。

This document collected by the Society for the Study of Chinese Architecture, supports the above conclusions. It recorded that in the 39th year (1774) of the Qianlong period, two Liang of Dingyuanzi (顶元子) and two Liang of Yangqing (洋青) were used to build a glaze stupa. Dingyuanzi (顶元子) is a kind of Chinese cobalt material, and yangqing (洋青) is a Chinese name for imported cobalt. The glaze of the stupa was a mixture of imported and local cobalt materials. Combined with the electron microscope images and the results of compositional tests, we inferred that the glaze added smalt and the domestic cobalt material added a small amount of lead oxide. The addition of lead oxide has resulted in a reduction in arsenic loss in smalt, retaining a little.

This provides strong support for our mixture cobalt materials viewpoint38. The reason for mixing cobalt materials may be related to the diffusion principle of Co41,42. In addition to the mixed use of smalt in the paintings in the Qing Dynasty, the use of smalt mixed with purple was also found in Japanese paintings35,43,44, and even European paintings31 can still see the phenomenon of mixed use of smalt, so it can be seen that the mixed use of smalt was not an isolated phenomenon of the Qing Dynasty in China. It can be seen that smalt was not a very expensive and precious pigment in both China and Japan during this period41,43. The fact that smalt was also used on Buddhist statues in Japan31 suggests that the trade in smalt was accompanied by the exchange of techniques for using smalt45. Notably, the use of a mixture of European and Asian cobalt ores by workshops during the Qianlong reign has already been documented for the production of certain objects, and was attributed to an intention to reduce production costs, as cobalt materials imported from Europe were more expensive29. The affordability and ease of use of smalt may have been among the key reasons for its widespread import and application in the region. Together, these observations highlight the transregional circulation of materials and technological knowledge in early pigment production across Eurasia.

This study examined nine samples of blue building glaze components unearthed from Yuanmingyuan Park. Its findings are as follows. Different from the body of the building glaze component of the Ming Dynasty, which is made of clay, the body of nine samples from Yuanmingyuan Park is coal-based kaolinite. Its firing temperature is 1000 °C to 1050 °C. The high K, As, and Ni (including Bi) in the glaze indicate that the material consists of imported smalt, and its situation is that of glass powder. The content of Mn in the glaze indicates that the cobalt material is a mixture of local cobalt and imported smalt.

Mixed cobalt material has been used in blue and white porcelain since the Xuande period of the Ming Dynasty and in the middle and late Ming Dynasty. Until now, it has been unclear how it was used in China’s ceramics and porcelain during the Qing Dynasty. This study fills this gap. Our research revealed that mixed cobalt material continued to be used in porcelain in the Qing Dynasty. Our research also revealed that the imported smalt was glass powder. As the powder was easy to transport and store, smalt could be applied not only to painting decorations on Chinese buildings but also to the Chinese porcelain industry.

Data availability

References

Kang, B. et al. Research on the Yuan Dynasty materials and firing technique of turquoise-glazed tiles excavated from the Palace Museum (in Chinese). J. Gugong Stud. 1, 191–199 (2018).

Kang, B., Wang, S., Duan, H., Chen, T. & Miao, J. Preliminary research on the manufacture location and date of glazed tiles for the Forbidden City’s gate of divine prowess (Shenwu men) (in Chinese). J. Gugong Stud. 2, 234–241 (2013).

Kang, B., Li, H. & Miao, J. M. Study on the composition of the glaze of glazed tiles of the Forbidden City in the Qing Dynasty and related problems (in Chinese). Cult. Relics South. China. 2 (2013).

Dou, J. H. et al. Forming mechanism of mica iron oxide from glazed tiles in Yuanmingyuan. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 35, 492–499 (2018).

Guo, J. et al. Review of Beijing cultural relics and archaeological work in 2015 (in Chinese). Beijing Cult. Relics Mus. 1, 44–51 (2016).

Sun, M., Zhang, Z., Cao, M., Liu, J. & Zhu, A. Archaeological excavation brief of the great palace gate area of Yuanmingyuan site park (in Chinese). Beijing Cult. Relics Mus. 3, 76–87 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Determination and interpretation of firing temperature in ancient porcelain utilizing thermal expansion analysis. Herit. Sci. 12, 282 (2024).

Li, J. & Zhou, R. Effect of atmosphere on the heating behaviour of some porcelain blanks (in Chinese). J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 4, 158–165 (1959).

Li J. A History of Science and Technology in China (Ceramics). Science Press, Beijing (1998).

Shen B. Ming dynasty. Wanshu miscellany. Beijing: Beijing Press; (1961).

Duan, H. Y. et al. Research of Qing Dynasty official glazed tile bodies in Beijing (in Chinese). J Build Mater. 6, 430–434 (2012).

Dian S. (ed.). Records of colored glaze factory. Beijing: Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House; 1982.

Molera, J. et al. Interactions between clay bodies and lead glazes. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 84, 2362–2370 (2001).

Kacem, I. B. et al. Structure and properties of lead silicate glasses and melts. Chem. Geol. 446, 119–129 (2017).

Ma, R., Zhong, Y., Cui, Q. D., Jiang, J. & Xie, X. A preliminary study on the excavation of blue and white porcelain from the Imperial Kiln Factory site (in Chinese). Anc. Civil. 14, 162–182 (2020).

Li, H., Zhao, J., Kang, B. & Shi, N. Non-destructive analysis of Kangxi blue and white porcelain specimens excavated from the South Treasury of the Forbidden City (in Chinese). China Cult. Herit. Sci. Res. 03, 64–70 (2022).

Panighello, S. et al. Investigation of smalt in cross-sections of 17th-century paintings using elemental mapping by laser ablation ICP-MS. Microchem. J. 125, 105–115 (2016).

Insaurralde, C. M. & Castañeda-DM. At the core of the workshop: Novel aspects of the use of blue smalt in two paintings by Cristóbal de Villalpando. Arts. 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020025.

Zlámalová, C. Z., Gelnar, M. & Randáková, S. Smalt production in the ore mountains: Characterization of samples related to the production of blue pigment in Bohemia. Archaeometry 62, 120215 (2020).

Mühlethaler, B. & Thissen, J. Smalt In: Roy A., editor. Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, vol. 2. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art. p. 113–130 (1993).

Liu M. A study of the pigments used in the coloured paintings seen in the Qing dynasty official cultivation of artisanal works. (Ph.D. Dissertation) Tsinghua University; 2019. https://doi.org/10.27266/d.cnki.gqhau.2019.000535.

Cavallo, G. & Riccardi, M. P. Glass-based pigments in painting: Smalt blue and lead–tin yellow type II. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01453-7.

Coentro S. et al. White on blue: A study on underglaze-decorated ceramic tiles from 15th–16th-century Valencian and Sevillian productions. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102254.

Jonynaite, D., Senvaitiene, J., Beganskiene, A. & Kareiva, A. Spectroscopic analysis of blue cobalt smalt pigment. Vib. Spectrosc. 52, 158–162 (2010).

Ricciardi, P. et al. Use of standard analytical tools to detect small amounts of smalt in the presence of ultramarine as observed in 15th-century Venetian illuminated manuscripts. Herit Sci. 10, 38 (2022).

Bajnóczi, B., Nagy, G., Tóth, M., Ringer, I. & Ridovics, A. Archaeometric characterization of 17th-century tin-glazed Anabaptist (Hutterite) faience artefacts from North-East Hungary. J. Archaeol. Sci. 45, 1–14 (2014).

Kim, G. A study on smalt pigments used in large Buddhist paintings in the 18th and 19th centuries. Natl. Res. Inst. Cult. Herit. 55, 120–129 (2022).

McCarthy, B. & Giaccai, J. (eds) Scientific Studies of Pigments in Chinese Paintings. Archetype Publications, London, in association with the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (2021).

Colomban, P., Simsek Franci, G., Gironda, M., d’Abrigeon, P. & Schumacher, A.-C. pXRF data evaluation methodology for on-site analysis of precious artifacts: Cobalt used in the blue decoration of Qing Dynasty overglazed porcelain enameled at Customs District (Guangzhou), Jingdezhen and Zaobanchu (Beijing) workshops. Heritage 5, 1752–1778 (2022).

Giannini, R., Freestone, I. C. & Shortland, A. J. European cobalt sources identified in the production of Chinese famille rose porcelain. J. Archaeol. Sci. 80, 27–36 (2017).

Montanari, R., Colomban, P., Alberghina, M. F., Schiavone, S. & Pelosi, C. European smalt in 17th-century Japan: Porcelain decoration and sacred art. Heritage 7, 3080–3094 (2024).

de Mecquenem, C. et al. A multimodal study of smalt preservation and degradation on the painting “Woman doing a Libation or Artemisia” from an anonymous painter of the Fontainebleau School. Eur. Phys. J. 138, 1–8 (2023).

Lei, Y., Cheng, X., Yang, H., Qu, W. & Wang, S. W. Study of smalt in the architectural paintings in Jian Fu Gong of the imperial palace (in Chinese). J. Palace Mus. 4, 140–156 (2010).

Teri, G. et al. A study on the materials used in the ancient architectural paintings from the Qing Dynasty Tibetan Buddhist monastery of Puren, China. Materials 16, 6404 (2023).

Xia, Y. et al. Smalt: An under-recognized pigment commonly used in historical period China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 101, 89–98 (2019).

Shen, L., Kang, Y. & Li, Q. Analytical study of polychrome clay sculptures in the five-dragon Taoist palace of Wudang, China. Coatings. 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings14050540

Jiang, X. et al. Raman analysis of cobalt blue pigment in blue and white porcelain: A reassessment. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 190, 61–67 (2018).

Colomban, P. & Simsek, K. aynakB. G. Cobalt and associated impurities in blue (and green) glass, glaze and enamel: Relationships between raw materials, processing, composition, phases and international trade. Minerals 11, 633 (2021).

Hui N (Xi Na). Analysis and research on smalt pigment in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. (MA Dissertation, Northwestern University); (2015).

Wu, J., Zhang, M. & Li, Q. Composition and chromatic characteristics of imperial Jilan glaze from the Ming and Qing dynasties (in Chinese). Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 32, 2254–2259 (2012).

Jiang, X. C. Y. et al. Revisiting the bleeding effect in historical cobalt porcelain pigments: Mechanism, influence and technical responses. J. Archaeol. Sci. 167, 105987 (2024).

Robinet, L., Spring, M. & Pagès-Camagna, S. Vibrational spectroscopy correlated with elemental analysis for the investigation of smalt pigment and its alteration in paintings. Anal. Methods 5, 4628–4636 (2013).

Ichimiya, Y., Taguchi, S. & Mizumoto, K. The use of smalt in the Japanese folk paintings, Doro-e and Megane-e (Vue d’Optique). Stud. Conserv. 2023;1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2023.2275099

van, L. et al. The role of smalt in complex pigment mixtures in Rembrandt’s Homer 1663: combining MA-XRF imaging, microanalysis, paint reconstructions and OCT. Herit Sci. 8, 90 (2020).

Montanari, R. et al. European ceramic technology in the Far East: Enamels and pigments in Japanese art from the 16th to the 20th century and their reverse influence on China. Herit. Sci. 8, 48 (2020.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 20&ZD251). Samples were kindly made available for analysis by Beijing Institute of Archaeology. We thank Xiaochenyang Jiang for her help with the preliminary research and Dr. Yujie Wu for her help with the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. Z.L. and M.C. contributed the samples and the excavation information; M.P. and H.J. wrote the paper. Z.Z. designed research; M.P. performed research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ping, M., Jin, H., Zhang, Z. et al. Application of smalt in building glazed tiles from Yuanmingyuan Park, Beijing’ in Qing dynasty. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01803-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01803-x