Abstract

This study constructs a quantitative analysis toolkit for heritage site selection by integrating Monte Carlo simulation, spatial density analysis, kernel density estimation, and partial correlation analysis. Taking the Ming Dynasty Yansui defense district as an empirical case, based on vectorized historical spatial data and geographical simulation statistics, the “Geographical Environment-oriented Cognitive Framework for the Great Wall Site Selection” is proposed. The framework deconstructs the intricate relationships between the Great Wall and its geographical environment into three analytical dimensions—spatial representation, environmental preference, and defense features. It explains the spatial distribution characteristics of the Great Wall heritage under different geographical environments in the ecologically fragile Loess Plateau, and its differentiated siting preferences and synergistic evolution with topographic factors. The research provides scientific support for predicting Great Wall sites, conservation planning, and resource management, offering methodological references for studying the spatial locations and environmental variables of linear cultural heritage and settlement systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Great Wall refers to the large-scale military engineering works constructed during various periods of ancient China to defend against invasions by northern nomadic tribes. It is one of the most significant symbols of Chinese culture, representing not only a unique historical and cultural heritage but also serving as a historical witness to the long-term confrontation, ethnic exchanges, and integration between the agrarian civilization of central China and the nomadic civilization of the northern regions. The Ming Dynasty marked the final peak period of the construction of the Great Wall in China, during which its defensive structures and engineering techniques reached their most advanced and sophisticated stage. Research on the Ming Great Wall has evolved from historical geography, cross-validation of historical documentary evidence and archeological excavations to involve multiple disciplines and fields, with its scope and depth continually expanding. As a defensive fortification, the construction of the Great Wall Military Defense System (GWMDS) showed evidence of systematic planning and functionality1, with its defense strategy reflected in the selection of site locations. Over the years of offensive and defensive warfare, the adjustment and modification of its site locations were influenced by multiple factors, including the geographical environment2, warfare conditions3, and regional social dynamics4. Among these factors, natural topography played a crucial role in shaping the siting and spatial distribution of the Great Wall5, reflecting, to some extent, the ancient people’s preferences for and adaptation to environmental resources and topographical features.

Previous studies have established the complex interaction between the siting of various heritage types of the GWMDS and natural topography, focusing mainly on qualitative distribution patterns, such as strategic positioning on rugged topography, control of key routes, access to water sources, and communication lines. Based on the topographic strategic value, fortifications were strategically placed with varying density. With the deep integration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and modern surveying technologies, spatial analysis has achieved numerous practical results in the field of archeology6,7,8, particularly in settlement archeology research. Examples include studies on settlement morphology and landscape environment9,10, archeological site simulation and prediction11,12, human-land relationships, and the spatiotemporal evolution of settlements13.

The quantitative thinking and related spatial analysis methods represented by GIS have also been gradually applied to the study of linear cultural heritage sites such as the Great Wall14. By integrating environmental data, archeological site information, and historical archives, GIS can construct multi-level spatial databases encompassing geographic coordinates, imagery, and documentary records, laying the foundation for digital protection and monitoring of cultural heritage15, and historical landscape reconstruction16,17. GIS geographic modeling plays a crucial role in analyzing the spatial processes of linear heritage: in geographical environment analysis, nearest neighbor analysis18 and kernel density estimation methods19 are commonly used to reveal the coupling patterns between linear heritage spatial distribution and environmental factors such as topography and hydrographic systems20. At the site domain level, methods such as fractal dimension21, Thiessen polygons22, and Least-cost Path analysis23, are employed to quantify the spatiotemporal evolution of settlements24, and their environmental adaptation25. Consequently, historical human activity trajectories and resource circulation pathways are reconstructed26. At the viewshed level, three-dimensional viewshed analysis further expands the landscape archeology perspective, evolving from early static visibility judgments based on Digital Elevation Models (DEM) to now comparing visual coverage areas, constructing information transmission paths from individual buildings to groups, and subsequently evaluating the operational efficiency of communication systems27,28,29. These achievements have laid an important foundation for understanding the spatial patterns of linear heritage.

However, existing research has largely focused on first-order geographical attributes of site locations—utilizing simple statistical models and GIS spatial analysis tools to explore the independent distribution patterns of specific sites through single-factor topographic indicators such as elevation, slope, and distance to hydrographic system. While these studies can preliminarily reflect heritage site selection tendencies, they overlook more complex spatial dimensions—failing to position site clusters within their regional geographical context. This has led to insufficient quantitative research on second-order attributes (the relative relationships between site spatial distribution and natural topographic features)30, causing existing “heritage-function-environment” analyses to remain primarily at the level of locational description and functional speculation. This limitation makes it difficult to effectively differentiate between the boundaries of endogenous drivers of heritage functional requirements and the exogenous shaping of topographic constraints. Such restrictions in research perspective not only weaken the explanatory capacity of topographic factors in heritage site selection but also, to some extent, constrain our accurate understanding of site selection patterns for linear heritage like the Great Wall and the precise characterization of heritage spatial distribution features.

Against this backdrop, Monte Carlo simulation, as a numerical computation method based on probability and statistical theory, has become an ideal tool for exploring the complex relationship between the siting of the Great Wall and its geographical environment, given its unique advantages in simulating complex geographical systems. This method generates numerous random numbers from probability distributions to simulate complex systems or processes and estimates system performance or outcomes through statistical analysis of these numbers31. It has been gradually applied in fields such as geophysics32 and environmental archeology33, and other domains for simulating complex physical processes34,35, prediction and risk assessment36.

In environmental archeology, particularly in archeological site location analysis, Monte Carlo simulation demonstrates substantial potential. Based on the null hypothesis of Complete Spatial Randomness (CSR)37,38, there is no statistically significant difference between the observed and random modes of the sites. To validate this premise, the conventional approach to Monte Carlo Hypothesis Testing involves constructing an envelope through reasonable confidence intervals. If observations fall within the envelope’s confidence interval, the pattern is considered spatially random39,40. Observations exceeding the upper limit suggest a clustered spatial distribution, while those below the lower limit indicate a uniform distribution pattern. On this basis, combined with Point Pattern Analysis (PPA)41,42, Monte Carlo simulation can investigate the spatial patterns43,44, interdependencies45, and landscape preferences46 of archeological sites relative to natural landscape elements. This approach provides ideas for revealing complex issues such as behavioral patterns and human activity regularities underlying spatial locations or environmental variables.

In research exploring the relationship between Great Wall site selection and geographical environment, Monte Carlo simulation can model features of the geographical environment into a series of comparable equivalent topographic point datasets while retaining and quantifying their spatial characteristics. This makes direct analysis and comparison of cross-type data possible. When combined with spatial analysis methods such as kernel density estimation and partial correlation analysis, this approach enables further interactive analysis between heritage sites and the geographical environment. This methodology helps quantify the influence of topographic features on site selection, as well as the differentiated roles of these features in different geographical regions, providing new perspectives and methods for studying the GWMDS site selection.

Based on these observations, this paper takes the Great Wall of Yansui defense district in the Ming Dynasty as an empirical case, innovatively introduces the Monte Carlo simulation method, and integrates it with various parameter measurement and model analysis methods. By establishing a “Geographical Environment-oriented Cognitive Framework for the Great Wall Site Selection (GEC-GWS framework)”, this study compares the statistical characteristics between topography at heritage sites and their surrounding geographical environment, to reveal topographic preferences in site selection decisions. Then it deeply analyzes how topographic factors interact with the siting decisions of the Great Wall heritage, providing methodological support for exploring the underlying rules behind the Great Wall siting and precisely characterizing its spatial distribution patterns. Specifically, the study focuses on: (1) analyzing the spatial distribution characteristics of various heritage resources within the Great Wall in Yansui defense district systematically; (2) investigating the environmental preferences and quantitative patterns of various heritage distribution under the synergistic effects of single and combined topographic factors; and (3) revealing the relationships between different geographical environment and the military defense efficiency of the GWMDS, as well as the underlying military defense mechanisms.

Methods

Through integrating multi-source data and quantitative models, this study establishes a “Geographical Environment-oriented Cognitive Framework for the Great Wall Site Selection (GEC-GWS framework)” (Fig.1). This framework deconstructs the intricate associations between the Great Wall and its geographical environment into three analytical dimensions——spatial representation, environmental preference, and defense features—to elucidate interactions among the GWMDS heritage spatial distribution, military defensive functions, and the geographical environment. Within this framework, the spatial representation dimension reveals the spatial distribution patterns of various Great Wall heritage types. The environmental preference dimension examines how topographic factors (e.g., slope, elevation) influence site selection for different types of military heritage. The defense features dimension, based on the geographical environment of each defense region, analyzes the differentiated layout logic of the Great Wall heritage by comparing the relationships between topographic features and defensive requirements across different defense regions.

To support the GEC-GWS framework, a spatial analysis toolkit based on Monte Carlo simulation is constructed, with its technical core enabling cross-dimensional data spatial comparability through geographical environment point-set modeling. Specifically, Monte Carlo simulation is utilized to discretize the geographical environment and the major frontier wall of the Yansui defense district into point sets. This approach effectively captures the topographic features and provides a data foundation for conducting correlation analysis between the geographical environment and heritage sites. Building on this, a quantitative analysis toolkit is developed, including spatial density analysis, kernel density estimation, and partial correlation analysis. These methods form a progressive analytical framework advancing from the spatial characteristics of the GWMDS to topographic feature preference analysis.

Within this analytical framework, the geographical environment is defined as a spatial field formed by the combined effects of the natural terrain and the militarized heritage system. This includes not only topographic factors such as elevation, slope, and aspect that directly influence the construction of defensive works, but also the dynamic shaping of defensive layouts through military functional adjustments. Topographic factors, as a subset of the geographical environment, focus on the physical attributes of surface morphology and serve as key mediating factors in analyzing site selection decisions. This study conducts a statistical analysis on four topographic factors between the Great Wall heritage site selection and a Monte Carlo simulation-based geographical environment, quantifying the differential action mechanisms of single and combined topographic factors in site-selection decision-making. This analysis provides a new perspective and systematized analytical tools for interpreting the spatial wisdom embedded in the Great Wall heritage.

Research area and research object

Research area

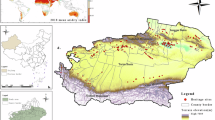

The research area is the defense district of Yansui in the Ming Dynasty (Fig. 2.), located in northern Shaanxi Province, China, spanning the cities of Yulin and Yan’an from north to south. It passes through seven counties or districts: Fugu County, Shenmu County, Yuyang District, Hengshan District, Jingbian County, Wuqi County, and Dingbian County. As one of “the Nine Military Districts of the Frontier” in the Ming Dynasty, the Great Wall of Yansui defense district was a pioneer and model in the construction of the Ming Great Wall47. Yansui defense district is located at the southeastern edge of the Mu Us Desert (Ordos Desert) and the transition zone of the Loess Plateau. This area is mainly characterized by the landforms of the Loess Plateau and sandy grasslands, with diverse medium and small-scale geomorphological types. The natural landscape of the area is highly complex48. The climate is classified as semi-arid continental monsoon, with dry and cold characteristics, severe soil erosion, and a fragile ecological environment.

The entire Great Wall of Yansui defense district is divided into three-routes' defense zones49: the Eastern Route (Shenmu Dao), the Central Route (Yulin Dao), and the Western Route (Jingbian Dao), which roughly correspond to the three kinds of micro-natural topographic features along the Great Wall50. The Eastern Route is mainly distributed in the loess hilly and gully area, with landform sloping from northwest to southeast, and an elevation between 1,000 and 1,200 meters, dominated by loess ridges. Due to water erosion, the surface of the land is characterized by numerous gullies and valleys, while the valley areas are low-lying and flat, with the Huangfu River, Qingshui River, and Gushan River providing convenient irrigation. The Central Route is mostly distributed in the dune and grassland area, which is an essential part of the Mu Us Desert. Sandy land constitutes the main regional type of this area, often forming continuous dunes under wind action, with grasslands and terraces interspersed between dune areas and river valleys. The Western Route is primarily composed of the loess high plain lake basin on the northern side and the Baiyu Mountain ridge-like low mountain and hilly area on the southern side. The northern loess high plain region has a dry climate, severe wind erosion, minimal relief due to the lack of water incision, and generally flat terrain, with an elevation between 1,300 and 1,500 meters. The high plain is often dotted with lakes, marshes, or salt flats. The southern side consists of Baiyu Mountain ridge-like low hills, with peaks mostly above 1,500 meters, featuring interwoven ridges and valleys (Fig. 3).

a Elevation distribution map showing altitude variations across the Yansui defense district; b Aspect analysis map illustrating slope orientation and directional characteristics throughout the region; c Slope gradient analysis map depicting terrain steepness; d River network map displaying the distribution and connectivity of rivers and waterways within the district.

Research object

The research object is various Great Wall heritages of Yansui defense district in the Ming Dynasty, located within the present-day areas of Yulin and Yan’an cities in China. The heritage consists of the major frontier wall and secondary frontier wall, defense towers (named “Dun tai” in the Ming Dynasty), passes, and forts. The major frontier wall is an artificial structure, initially built in the 10th year of Ming Chenghua (1474 AD), and was repaired during Ming Zhengde (1506–1521 AD) and Jiajing (1521–1567 AD) periods, with major reconstructions carried out during Ming Longqing (1567–1572 AD) and early Wanli periods (1573–1620 AD). The “secondary frontier wall” harnessed the Loess Plateau’s natural landform by integrating into it, creating a natural defensive barrier. It is located to the south of the major frontier wall and was constructed in the 9th year of Ming Chenghua (1473 AD), with little remaining today. Due to the construction location and functions, defense towers can be classified into two types: one is the watchtower positioned on the major frontier wall, serving defensive and alert functions, which includes enemy towers built on the wall and horseface-shaped bastions attached to one side of the wall; the other type is the beacon tower scattered along the wall, responsible for observing and monitoring the area outside the Great Wall and transmitting information. The passes are located along the defensive line of the wall and serve as primary defensive strongholds during military conflicts. Forts include battalion forts and “Zhai” forts, which are both defensive settlements. Battalion forts were built every 30–50 “li” (a traditional Chinese unit of length, “1 li” is approximates 587.88 meters in Ming Dynasty) to the south of the Great Wall, serving as essential sites for troop stationing, responsible for guarding several “li” of the Great Wall and its defense towers. “Zhai” forts are slightly smaller in scale than battalion forts but also serve as important military garrison locations. There is also a central town in Yansui defense district, serving as the command center of the defense system, located in the central defense zone to coordinate battle deployments and troop movements, ensuring the coordinated operation and strategic responsiveness of the overall defense system.

Accordingly, this study categorizes the research objects (Fig. 4) into five types—the major frontier wall, watchtowers, beacon towers, passes, and forts—based on their relative position to the major frontier Wall, scale, and function, while also referencing historical records49,51, national standards52,53, and academic research54. The study conducts an in-depth investigation of their spatial distribution characteristics both across the entire region and within the eastern, central, and western military defense zones. By combining quantitative analysis of topographic factors influencing various Great Wall heritage sites selection, this research aims to reveal the spatial distribution of heritage across different military defense zones and the environmental driving factors behind the construction of the GWMDS.

Research objects - current photographs of the Great Wall heritage sites (Photo source: Shaanxi Ming Great Wall Resource Survey Project Team, historical map source51:).

Data collection and processing

The research data comprise three main components (Table 1): information on the Ming Great Wall heritage in the Yansui defense district, topographic data, and boundary data. Based on data from the Shaanxi Academy of Archeology (Shaanxi Ming Great Wall Resource Survey Project Team)2, original textual records were processed using spatial information filtering and geocoding techniques and converted into standardized topographic vector data. Through systematic extraction and classification, a comprehensive spatial database of the Great Wall heritage was developed, including 375 linear segments of the frontier walls and 1612 point features—specifically, 560 beacon towers, 908 watchtowers, 68 passes, and 76 forts.

The digital elevation model (DEM) for the Yansui defense district, with a 30-meter spatial resolution, was obtained from ASTER GDEM (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer Global Digital Elevation Model). River vector data were sourced from the OpenStreetMap platform and supplemented by visual interpretation of high-resolution remote sensing imagery. To ensure data accuracy and historical fidelity, cross-validation was conducted using multiple sources, including historical water system maps of the Ming Dynasty Yansui defense district and hydrographic system maps of Shaanxi Province55. This approach accurately reflects the topographical features of the Ming Dynasty Yansui defense district. The administrative boundaries of the Yansui defense district were primarily determined with reference to the “Historical Map of Shaanxi in the 10th Year of Wanli (1582 AD)” from the “Historical Atlas of China”56, and georeferenced using GIS tools. To account for the spatial extent of various Great Wall heritages and potential accuracy limitations of historical maps, the research area was defined by extending the historical map boundaries outward by 10 kilometers.

Random point generation based on a Monte Carlo simulation

This study aims to examine the spatial distribution of different types of heritage sites in relation to the topographic characteristics of their geographic environment. However, the heterogeneity in data structure among the major frontier wall (linear continuous features), the geographical environment (surface continuous features), and discrete heritage points makes kernel density estimation methods unsuitable. Additionally, the lack of statistical equivalence among multi-source spatial elements presents further challenges. Therefore, leveraging the advantages of Monte Carlo simulation, the research produced two geographically meaningful random point sets—random points representing the geographical environment (RP) and random points along the major frontier wall (RPW), both with a sample size of 1500.

RP is a set of randomly generated points within the Yansui defense district, representing the region’s general geographical environment. Statistical analysis of topographic factors at these points reveals the natural distribution patterns of elevation, slope, aspect, and the nearest distance to the hydrographic system in the area. In contrast, RPW consists of randomly generated points along the major frontier wall, capturing the specific topographic characteristics where the Wall is located and reflecting the terrain preferences in the Wall’s site selection. By generating RP and RPW, this study standardized both the areal geographical background and the linear Wall structures into point datasets, unifying different spatial data types. This transformation, achieved through Monte Carlo simulation, removes morphological differences among heterogeneous topographic elements and provides a consistent point-based data foundation for subsequent comparative topographic analysis and quantitative research on heritage-environment relationships.

To ensure comparability with the heritage points (n = 1612), the sample size for random points representing the geographical environment of the Yansui defense district was set to 1500. Unlike traditional random sampling based on a single assumed sample size, this study undertook systematic pilot studies to ascertain the statistically optimal sample size. (Fig. 5). Multiple sample sizes were tested, and for each, 1000 Monte Carlo simulations were performed to generate confidence interval envelope lines for kernel density estimation (KDE). The process involved randomly generating points within the district, extracting topography values for each point, and calculating probability density distributions using Gaussian KDE. By repeating these steps 1000 times, the statistical distribution of density values at each location was obtained. The 95% confidence interval envelope was defined by the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles, indicating the range within which 95% of simulation results fell, while the median line represented the median density value at each location. The width of the confidence interval reflected estimation uncertainty, with narrower intervals indicating more stable and reliable results. Experimental results showed that when the sample size reached 1500, the standard deviation of the KDE curves for topography parameters stabilized, indicating a reliable level of statistical confidence. Moreover, 1500 was also the predetermined target sample size chosen to ensure comparability with the heritage points. Based on both considerations—the statistical stability demonstrated in repeated experiments and the need for data comparability—1500 was determined to be an appropriate and optimal sample size, balancing efficiency and avoiding oversampling.

The GEC-GWS spatial analysis toolkit

Based on the Monte Carlo simulation results, a multi-level spatial analysis toolkit was developed within the Geographical Environment-oriented Cognitive Framework for the Great Wall Site Selection (GEC-GWS framework) to quantitatively assess the spatial relationship between topographic features and defensive heritage site selection. The toolkit includes three main components: spatial density analysis, single-variable kernel density estimation comparison, and multivariate partial correlation analysis. The spatial density tool visualizes the distribution of heritage sites and highlights spatial heterogeneity. The single-variable kernel density comparison tool quantifies clustering patterns and density gradients of heritage points in relation to topographic variables, thereby revealing site selection preferences. The multivariate partial correlation tool examines how the interactions among multiple topographic factors influence the Great Wall heritage site selection, clarifying the synergistic mechanisms underlying military heritage siting decisions. The specific analytical procedures are as follows (Fig. 6):

Spatial distribution characteristics of various Great Wall Heritages: spatial density analysis

Density estimation methods were used to visualize and analyze the spatial distribution and clustering patterns of Ming Dynasty Great Wall heritage sites in Yansui defense district, revealing the overall distribution of various heritage elements. Kernel density analysis was applied to four categories of point features—beacon towers, watchtowers, passes, and forts—while line density analysis was used for the major frontier wall. The overall density distribution of point elements was then obtained by overlaying the kernel density layers for all categories. The formulas for calculating kernel density and line density are shown in Eqs. (1) and (2), where \(K\) is the density function, \(D\) represents the density value, \(h\) is the search bandwidth set to one kilometer, \({W}_{i}\) is the weight value for each point feature, \(d(x,y,{x}_{i},{y}_{i})\) denotes the distance between the location \((x,y)\) and the point feature at \(({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\), \(n\) is the total number of point features, \({L}_{i}\) represents the length of line segment \(i\) passing through the search radius, \(d(x,y,{l}_{i})\) is the distance from location \((x,y)\) to line segment \({l}_{i}\), \(m\) is the total number of line segments, and \(A\) is the total area of the search region57,58.

Influence of single factors on Great Wall heritage site selection: comparative kernel density estimation

On the ArcGIS platform, spatial joins were used to associate topography layers with heritage feature locations, precisely extracting four topographic attributes—elevation, slope, aspect, and the nearest distance to hydrographic system—for each heritage point. To ensure data quality, preprocessing steps such as validity filtering, unit standardization, and long-tail truncation were applied, preserving the essential characteristics of the data distribution. The Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) method was employed to analyze the spatial distribution characteristics of heritage elements, with its mathematical expression shown in formula (3), where \(\hat{f}(x)\) is the estimated density function, representing the estimated probability density value at any point \(x\). \(\frac{1}{{nh}}\) is the normalization factor ensuring that the integral of the density function equals 1, \(n\) is the sample size, \({h}\) is the bandwidth parameter, \(K\) employing a Gaussian kernel function, and \(\frac{x-{x}_{i}}{h}\) represents the standardization of the distance between point \(x\) and data point \({x}_{i}\)59,60\(.\)

This research established a technical framework for kernel density estimation (KDE) models through systematic parameter optimization and statistical validation. For bandwidth selection, a cross-validation approach was used, limiting the search range to [0.1, 1.0], and employing a bounded minimization algorithm (bounded minimize_scalar) to globally minimize the negative log-likelihood function. This ensured an optimal balance between model bias and variance. To quantify estimation uncertainty, 1000 bootstrap resampling iterations combined with Monte Carlo simulation were performed, generating 95% confidence intervals (α = 0.05) to assess the robustness of parameter estimates.

To improve data visualization, the display ranges of various topographic parameters were adjusted to address long-tail distributions: elevation was limited to 0.8–1.85 km to encompass 95% of samples; slope was set to the main range of 0–10°; aspect covered the full range of 0–360°; and the nearest distance to rivers was set to 0.02–30 km to reflect watershed spatial heterogeneity. These adjustments ensured full representation of the multi-scale characteristics of topographic elements. All computations were performed with Python 3.9.

The Great Wall heritage in the Yansui defense district is divided into Eastern, Central, and Western Routes based on variations in natural topography and defensive needs, which may lead to regional differences in site distribution patterns. Therefore, in addition to overall analysis, it is essential to conduct separate analyses for each route to gain more nuanced insights into how topographic factors influence site selection. Due to the sufficient sample sizes of beacon towers and watchtowers, analyses were conducted by route for these elements. Conversely, passes and fortresses, with relatively few occurrences, were only included in the overall domain analysis.

Influence of combined factors on Great Wall Heritage site selection: partial correlation analysis

In previous studies, the KDE statistical method primarily analyzed the independent effects of individual environmental factors on Great Wall site selection, without fully accounting for the spatial interactions between these factors. In contrast, partial correlation analysis can effectively control for other variables while assessing the relationship between two specific factors, thus more accurately revealing their independent correlation61. Based on this advantage, we applied partial correlation analysis to examine how combinations of topographic factors jointly influence the site selection of different types of Great Wall heritage sites.

Partial correlation analysis serves as a complementary analysis to Monte Carlo simulation and kernel density estimation methods. As shown in Eq. (4), elevation\(\,X\), slope \(Y\), aspect \(Z\), and the nearest distance to the hydrographic system \(W\) were selected as key topographic factors. Through calculating partial correlation coefficients \(r\), the research systematically analyzed the influence of the combinational relationships among these four topographic factors on the site selection of various Great Wall heritage types. \({r}_{{XY}.{ZW}}\) is the partial correlation coefficient between elevation \(X\) and slope \(Y\) after controlling for aspect \(Z\) and the nearest distance to hydrographic system \(W\); \({r}_{{XY}.Z}\) is the partial correlation coefficient between elevation \(X\) and slope \(Y\) after controlling for aspect \(Z\); \({r}_{{XW}.Z}\) is the partial correlation coefficient between elevation \(X\) and the nearest distance to hydrographic system \(W\) after controlling for aspect \(Z\); and \({r}_{{YW}.Z}\) is the partial correlation coefficient between slope \(Y\) and the nearest distance to hydrographic system \(W\) after controlling for aspect \(Z\)62\(.\)

At the same time, the geographical environment was used as a control to clarify the specific impact of different combinations of topographic factors on various Great Wall heritage site selection and spatial distribution. The analysis included statistical categories such as the major frontier walls, beacon towers, watchtowers, passes, forts, and geographical environment, covering the entire Yansui district as well as its eastern, central, and Western Routes.

Results

Spatial distribution characteristics of the Great Wall Heritage

Using the Line Density and Kernel Density tools in ArcGIS Pro, spatial density estimation analysis was conducted on the walls, beacon towers, watchtowers, passes, and forts in the Ming Yansui defense district. Kernel density distribution maps were generated for these types (Fig. 7), and the density distribution characteristics of the Yansui defense district’s military deployment were explained based on topographic features and defensive strategies.

a Kernel density map of all point-type Great Wall heritage sites showing overall distribution patterns; b Spatial density analysis of major frontier wall; c Spatial density analysis of beacon towers; d Spatial density analysis of watchtowers; e Spatial density analysis of passes; f Spatial density analysis of forts.

Overall, the Great Wall heritage in Yansui defense district extends horizontally along the direction of the major frontier Wall, exhibiting a clear segmentation characteristic. The density gradually decreases from northeast to southwest, with high-density areas concentrated along the northeastern section of the Wall, particularly in the areas of Fugu County, Shenmu County, and Yuyang Districts, which serve as the core defense zones for the eastern and Central Routes, demonstrating a high degree of clustering. In terms of strategic depth, the military heritage sites in Yansui defense district mainly extend southeastward into the hinterland along the Wuding River, forming a layered strategic system. Based on the statistical data of the neighboring distances between different heritage types (Table 2), small-scale facilities such as beacon towers, watchtowers, and passes are densely distributed in the frontline area of the Great Wall, forming the first line of defense. The average spacing of watchtowers is the smallest at 471 meters, followed by beacon towers and passes at 1695 meters and 2810 meters, respectively. In the hinterland, large forts serve as the core, with an average spacing of 7601 meters, highlighting their role as centers for military command and logistical support. Compared to the median spacing between forts, the median distance between forts and the major frontier wall is significantly lower, providing strong evidence of the close spatial relationship and strategic coordination between forts and the wall. The prominent feature of this layout is the coexistence of high-density frontline defense and strategic depth support in the hinterland, enhancing the defense effectiveness along the wall while ensuring effective control and support for the entire strategic area.

Further analysis of the distribution density of various heritage types reveals a close relationship between their individual layout and the terrain and defensive sections in which they are located. Overall, the alignment of the major frontier wall is perpendicular to major traffic routes to effectively block key transit points. The highest density areas extend from east to west, crossing Fugu County, Shenmu County, the border of Yuyang District and Hengshan District, Jingbian County, and reaching the far west of Dingbian County. These high-density areas are closely aligned with the topographic features, with higher wall density at points where the terrain shifts significantly. The distribution density of beacon towers follows a similar trend to the overall heritage density, decreasing gradually from northeast to southwest, with the average spacing increasing from the eastern to the Western Route. High-density clusters are formed in two areas: one at the border between Yuyang District and Hengshan District, and another in Jingbian County. In contrast, the kernel density distribution of watchtowers is opposite to that of beacon towers, with a significantly high-density cluster forming in the Western Route at Dingbian County. Forts are relatively evenly distributed along the three routes, but the Central Route, where the Yansui defense district central town is located, has the highest density, reflecting its role as the military garrison hub. Passes exhibit a high-density layout near the junction of the Central Route intersects with the eastern and Western Routes, enhancing the defensive capability of the central town. In conclusion, although the individual defensive sections focus on different functions, the overall GWMDS achieves a high level of balance and coordination in its layout, ensuring comprehensive coverage and effective defense along the Great Wall.

Simulation analysis of Great Wall Heritage types in the entire region

Using the kernel density estimation method and drawing on the Monte Carlo simulation approach, kernel density estimation models for each type of heritage site and geographical environment were constructed within the entire district, focusing on four topographic factors: elevation, slope, aspect, and the nearest distance to the hydrographic system. The aim was to analyze the spatial distribution patterns of Great Wall heritage sites under the influence of individual topographic factors, using geographical environment as a control, and to determine the degree of influence of different factors on the siting decisions. The results showed significant density differences in the spatial distribution of each heritage type within different value ranges of the four topographic factors (Fig. 8).

The overall density of topographic features first increases and then decreases with elevation, showing a notable concentration within the 1.06–1.18 kilometers elevation range. Compared to the smooth transition of the topographic curve, the elevation density curve of the major frontier wall exhibits a significant wave feature, particularly forming multiple peaks in high-elevation areas, indicating a local concentration and preference for high-elevation layout. Notably, the slope distribution of the major frontier wall differs significantly from the topographic curve: within the 0°–1.9° slope range, the wall’s distribution density is significantly higher than the topography, showing a trend of dense clustering. When the slope increases from 1.9° to 4.0°, the wall’s distribution density shows a marked decline, forming an approximately symmetrical distribution centered around 1.9°. This preference for gentle slopes differs from the traditional concept of the Great Wall being placed on steep and dangerous terrain. Field investigations revealed that, in practice, the walls are more likely to be in areas with moderate slopes but significant topographic variation—i.e., the boundary between flat and steep areas. These areas, with marked differences in slope on either side, are conducive to both defense and construction. In terms of proximity to hydrographic systems, the wall’s distribution is largely consistent with the geographical environment.

Based on comparative analyses of beacon towers, watchtowers, and geographical environment, the kernel density estimation curve for beacon towers generally aligns with the topographic trend, with clustering occurring at slopes of 0.75°–3.80° and at approximately 0.45 kilometers from the nearest hydrographical systems. The close relationship between beacon towers and hydrographical systems underscores the decisive role of water sources in the siting of beacon towers. The kernel density estimation curve for watchtowers is largely consistent with that of the major frontier wall, showing fluctuations in density compared to beacon towers in high-elevation areas and concentrated distribution in the gentle slope range of 0.67°–2.19°, indicating a preference for strategic high ground and gentle terrain. Additionally, the major frontier wall, beacon towers, and watchtowers all show significant clustering in north-facing aspects, a commonality that aligns closely with the overall defensive strategic layout, ensuring maximum coverage of the defensive field of view and efficient allocation of defensive forces.

Forts, serving as key garrison camps, logistics hubs, and troop centers, are larger in scale and evenly distributed across different elevation zones. They prioritize locations with accessible transportation networks to control vital transit routes and ensure efficient troop deployment. Forts are concentrated in areas with slopes between 0.53° and 3.39°. This low-slope region not only facilitates the planning, construction, and farming activities around forts but also aids in the rapid movement of cavalry units. In terms of aspect, forts are predominantly located on northeast-facing semi-shaded slopes, with orientations ranging from 25° to 111°. This layout is consistent with the defensive orientation of the Great Wall, effectively ensuring comprehensive monitoring and defense of the Great Wall area. Moreover, forts are closely tied to water sources, with the nearest distance peaking at approximately 0.43 kilometers, meeting the water needs of large stationed troops. Passes tend to be located at elevations of 1.17–1.37 kilometers and slopes below 1.9°, with significantly higher distribution density compared to the geographical environment. This feature indicates a preference for placing passes in mid-to-high elevation areas. Furthermore, the distance of passes from water sources shows multiple peaks, mainly concentrated in the range of 0.16 to 4.99 kilometers, reflecting the flexibility and strategic considerations of passes in adapting to different topographic conditions regarding water resources.

Topographic characteristics analysis of heritage types in the three-route defense zones

The entire Great Wall in the Yansui defense district is divided into three routes: eastern, central, and western, spanning various natural landforms. Due to differences in topography leading to different defensive requirements, the construction locations and defense strategies are adjusted accordingly to optimize defense effectiveness. Therefore, further analysis was conducted on the major frontier wall, beacon towers, and watchtowers in the Eastern, Central, and Western routes to explore how these types are precisely sited under different geomorphological characteristics to meet the unique defensive needs of each route.

Eastern route: Loess hilly and gully area

The eastern route is primarily located in the ridge and gully area, characterized by the widespread distribution of V-shaped valleys. The segmented clustering features revealed by the kernel density estimation curves for elevation, slope, and aspect distinctly outline the unique gully-filled landscape of this area (Fig. 9). The elevation kernel density estimation curve for the geographical environment in the Eastern Route shows an increasing trend followed by a decline with rising elevation, mainly concentrated in the mid-elevation range of 1.06–1.18 kilometers. The siting of the major frontier wall and beacon towers shows a distinct preference for high-elevation areas. At elevations above 1.2 kilometers, their distribution density is significantly higher than that in the geographical environment, with the overlapping area between their 95% confidence intervals and the geographical environment nearly approaching zero. This further validates that occupying the high ground is one of the guiding principles for selecting sites for walls and beacon towers. Although watchtowers also show a tendency to prefer higher elevations, they are more broadly distributed, covering a certain proportion of mid-elevation areas, primarily clustering in the 1.14–1.24 kilometers range to ensure seamless fire coverage with other fortifications.

In terms of siting considerations for slope and aspect, Great Wall heritage sites demonstrate greater adaptability to slope gradients compared to the other two routes, showing a high degree of consistency with the geographical environment’s kernel density. All three heritage types are concentrated within a slope range of 0.8°–4.2°, while favoring northeast and northwest aspects—characteristics that closely align with the overall defensive strategy of the Eastern Route. Heritage along the Eastern Route all exhibit the characteristic of water-proximal siting: the major frontier wall and beacon towers show a high degree of clustering at 0.30 km from water systems, while watchtowers primarily concentrate in the 0.56–0.87 kilometers distance interval from hydrographic systems. This phenomenon reveals the geographical advantage of dense river valleys in the Eastern Route region and its defensive characteristics: the layout of the frontier wall, beacon towers, and watchtowers revolves tightly around river valleys to ensure control over water sources and valley passage routes. Additionally, this layout facilitates smooth inland postal and communication traffic, aligning with the need for efficient logistical and informational connectivity.

Central route: dune and grassland area

The Central Route transitions from loess ridges to desert grasslands, with slopes generally between 0° and 4°, exhibiting a vast and gentle landform (Fig. 10). This topographic characteristic allows enemy cavalry to disperse and attack on flat ground, making traditional dense defensive layouts less effective in responding to such agile attacks. Therefore, the heritage site selection in the Central Route places more emphasis on the expansiveness of the view rather than simply relying on facility density. Specifically, the total number of beacon towers and watchtowers in the Central Route (east 407, central 340, west 465) is relatively lower compared to the other two routes, which is likely due to an optimized layout strategy aimed at maximizing visibility coverage and defense efficiency. In terms of elevation distribution, the major frontier wall and beacon towers tend to be sited in high-elevation areas to occupy high ground and expand the defensive field of view, significantly enhancing monitoring and defense capabilities. The layout of watchtowers is closely related to changes in the alignment of the wall, with a notable increase in watchtowers density and a more compact layout in the high-density section of the wall at 1.11–1.23 kilometers.

In terms of slope selection, the major frontier wall and watchtowers show a significant preference for low-slope areas, with concentrated distribution in the ranges of 0.63°–1.85° and 0.59°–1.83°, respectively, while beacon towers tend to cluster in a slightly higher slope range of 1.00°–2.12°. The slope aspects for all three types of heritage are primarily oriented towards the northwest and northeast, which aligns well with the strategic direction of the central-route’s defense. In terms of their spatial relationships with the nearest hydrographic systems, the degree of association between the three types of heritage and watercourses weakens compared to the Eastern Route, reflecting the differentiated siting strategies adopted by different military defense zones based on the characteristics of their geographical environments.

Western Route: Loess high plain and mountainous gully area

The Western Route consists of the loess high plain lake basin in the north and the Baiyu Mountain ridge-like low hill area in the south. The northern terrain is characterized by flat and expansive land, with an elevation higher than that of the other two routes (Fig. 11). The gentle terrain conditions make this zone a high-risk area for military conflicts, resulting in a significantly higher number of watchtowers compared to other zones (eastern 246, central 245, western 398). The dense distribution of watchtowers forms a network of intersecting fire, effectively curbing enemy advances. However, the number of beacon towers is not as high as expected (eastern 203, central 95, western 67). This layout likely reflects the rational utilization of the topography advantages, where the main function of beacon towers is to supplement the defense and provide early warning for watchtowers, given the unobstructed view in the flat terrain.

In terms of elevation distribution, the major frontier wall and watchtowers prefer low-elevation areas, mainly clustering in regions below 1.42 kilometers in elevation. Their distribution density exceeds the average level of the geographical environment, reflecting a strategy focused on near-ground defense. In contrast, beacon towers tend to be located on highlands with an elevation exceeding 1.57 kilometers. Their distribution density significantly increases within this elevation range, highlighting the strategic advantages of observation and early warning from high places. In addition, compared with the frontier walls and watchtowers, beacon towers have a higher selectivity for elevation. The kernel density estimation curve of beacon towers shows an obvious difference from that of the geographical environment, and their confidence intervals hardly overlap. This is because, with a limited number of beacon towers, the aim is to maximize the visual coverage by optimizing their elevation positions, thereby enhancing the efficiency and response speed of the overall early warning system.

In terms of slope distribution, the major frontier walls and watchtowers are significantly concentrated in low-slope areas, with the core point of dense distribution at a slope of 0.42°, while beacon towers are concentrated in the 1.5°–4.0° slope interval. Additionally, all three heritage types exhibit a dominant northwest orientation in aspect distribution, a characteristic that closely aligns with the defensive direction of the Western Route. The statistical trends in the nearest water system distance for the three heritage types are less pronounced compared to the other two routes, indicating that hydrographic system factors were given relatively limited consideration in their deployment.

Partial correlation analysis of topographic influencing factors

From the perspective of the combined effects of topographic factors, a comprehensive analysis of the heritage data reveals a general significant positive correlation between elevation and the nearest distance to hydrographical system, which is particularly pronounced in the Eastern Route (Fig. 12). The positive correlation coefficients of heritage sites are generally above 0.6, with the passes showing the most significant correlation at 0.8, far exceeding the geographical environment baseline of 0.5. This indicates that the siting of various heritage types in the Eastern Route is significantly influenced by elevation and hydrological conditions. Along the Great Wall from east to west, this partial correlation coefficient gradually weakens. In the Western Route, the relationship between the elevation of the geographical environment and the nearest hydrographic systems becomes statistically insignificant, whereas for frontier walls and watchtowers, this same relationship exhibits a negative partial correlation. This phenomenon may be attributed to the sparse river distribution in the Western Route, which spans different elevations and is not significantly concentrated in low-lying areas. During the siting process for watchtowers and frontier walls, relatively less consideration was given to factors related to proximity to hydrographic systems.

Secondly, there is a certain partial correlation between elevation and slope. Along the Great Wall from west to east, this partial correlation coefficient decreases gradually and shifts from positive to negative. In terms of the absolute value of these coefficients, the combined relationship between elevation and slope emerges as one of the key considerations in siting decisions for the Western Route, with both frontier wall and forts exhibiting partial correlation coefficients reaching 0.5. In the Eastern Route, other than the passes, the remaining heritage types generally exhibit a negative correlation between slope and elevation, a characteristic that aligns with the natural topographic changes in slope and elevation. In contrast, as key transit route control points, passes are often sited in steep and rugged terrain to facilitate surveillance and ambushes of the lower regions, resulting in a layout that exhibits characteristics of inverse topographic relationships.

In addition, a negative correlation is also observed between slope and the nearest distance to the hydrographical system, particularly in the siting of passes and forts in the Western Route, where the negative correlation coefficient is −0.4, which is more pronounced compared to the geographical environment. This combination reveals the influence of the unique geological and hydrological conditions of the Western Route on the siting layout of the GWMDS, which is also closely linked to the formation mechanism of the Salt Lake landscape in the Western Route. In steep mountainous areas, water often comes from snowmelt or natural rainfall, providing clear and potable water. Hence, passes and forts are often built close to water sources to ensure a stable water supply. In the flatter plains, due to geological conditions and evaporation, the salinity of water bodies tends to be higher, making it unsuitable for direct consumption. Therefore, the selection of passes and forts exhibits relatively independent layout characteristics from the hydrographic system. Water resources in the western region primarily rely on rainwater collection and storage through cisterns and ponds, as reflected in fortress names such as “Salt Yard Fort” and “Stone Pond Fort”.

The comparative analysis shows that the combination of topographic factors has a differentiated impact on the siting of different heritage types. More specifically, the siting of beacon towers demonstrates a dominant combination of factors, with a significant positive correlation between elevation and the nearest distance to the hydrographic system being the primary consideration, while the correlations among other topographic factors remain relatively weak. Passes, as strategic chokepoints, show strong partial correlations between elevation and the nearest distance to the hydrographic system, as well as slope and the nearest distance to the hydrographic system, in both the eastern and Western Routes. This correlation is particularly pronounced in the Eastern Route, far exceeding the whole and other routes’, highlighting the importance of water and topography conditions in the siting of passes in the Eastern Route. In comparison, the partial correlations of various topographic factors for frontier wall and watchtowers, across the entire region and the three routes, exhibit trends similar to those of the geographical environment, indicating their adherence to natural topographic changes and strong adaptation to the geographical environment. Forts, however, exhibit varying degrees of partial correlation between each pair of topographic attributes, indicating that their siting process considers a wider range of topographic factors and requires comprehensive decisions based on different combinations of environmental conditions.

Patterns and topographic interactions in Great Wall Heritage Site Selection

Based on the established GEC-GWS framework for understanding site selection of the Great Wall, this study explores the spatial layout patterns of the Great Wall heritage and the interactive effects of individual and combined topographic factors in the site selection of various types of heritage. The primary findings of Interactions between the Great Wall and the geographical environment are as follows:

Firstly, the Great Wall in Yansui exhibits a layout characterized by both high-density frontline defense and deep strategic support. Along the Great Wall, the overall heritage density gradually decreases from northeast to southwest. The layout of the major frontier wall closely follows terrain trends, running perpendicular to major traffic routes to effectively block key passageways, with distribution density significantly increasing at critical points of landform change. Beacon towers also follow a decreasing pattern from northeast to southwest, while watchtowers exhibit the opposite trend, reflecting the shaping effect of the geographical environment on heritage functions. In the depth direction, the various heritage types extend south-eastward along the Wuding River into the interior. As they approach the major frontier wall, their ranks diminish, and the distances between them decrease. This layout deeply integrates functional needs with the natural landscape, and the spatial distribution of heritage types is complementary, collectively creating a highly balanced and coordinated defense system.

Secondly, the distribution of the Great Wall heritage was influenced by the surrounding geographical environment, with elevation, slope, and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems having significant effects on site selection. The major frontier wall and watchtowers showed a localized concentration preference for high-elevation areas, while beacon towers, although also favoring high-elevation, low-slope areas, were not necessarily located at the highest point of the terrain, thus achieving broader geographical monitoring and coverage. Passes were in mid-to-high-elevation areas, while forts were often situated in places with convenient transportation and gentle terrain, both driven by strategic positioning and geopolitical advantages. Both forts and beacon towers exhibited a clear dependence on water sources, with forts generally located approximately 0.43 kilometers from the nearest water source. All heritage types showed a significant clustering toward the north, tightly integrated with the defensive strategic layout to maximize defensive visibility.

Thirdly, the segmented layout of the GWMDS was constrained by the macro-environment while also being flexibly adjusted at the micro-level according to changing defense needs. The system grasped the relationship between topography and military strategic requirements, dynamically adjusting resource allocation and defense layout to maximize the defense efficiency of the whole district and the three-route defense zones. The Eastern Route fully utilized the natural advantages of valley-dense areas, with elevation and hydrographic systems being core considerations in site selection. The Central Route transitioned from loess ridges to desert grasslands, where the expansiveness of view was the primary criterion for defense construction. In the Western Route, elevation rose significantly, and the number of watchtowers increased, reflecting adjustments in defense priorities and strategies. The site selection and construction of heritage types in different defense zones, based on the topographic characteristics of each area and the resource allocation needs of the wide defense line, exhibited significant differentiation. This differentiation fully embodied the optimization logic of spatial and resource allocation.

Fourthly, in terms of the combined effects of topographic factors, site selection for heritage in different defense zones was influenced by specific combinations of topographic factors. Among these, elevation and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems generally showed a significant partial correlation, particularly prominent in the Eastern Route, with a decreasing trend from east to west. There was also a negative correlation between slope and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems, which was most prominent in the Western Route. Meanwhile, the different heritage types, based on their functional characteristics, exhibited differentiated adaptability to combinations of topographic factors. The site selection of beacon towers was significantly influenced by the key combination of elevation and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems, while passes were influenced by the synergistic effect of elevation, slope, and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems, collectively supporting their strategic importance. In contrast, the site selection of forts was affected by more complex topographic combinations, reflecting a comprehensive assessment and trade-off of topographic factors during the site selection process.

Discussion

The Great Wall Military Defense System, as a tangible manifestation of the interaction between ancient human societies and the geographical environment, is rooted in a vast natural topographic foundation. The internal driving force behind its integration and evolution comes from a profound understanding and precise adaptation to natural topographic elements, a meticulous classification and efficient matching of heritage resource types, and a keen grasp of the temporal and spatial dynamics of invasion trends and defense needs along the three-route defense zones. Based on clarifying the spatial layout and environmental preferences of the GWMDS, this study further explores the interactions of topographic factors in site selection, aiming to elucidate how these factors contribute to enhancing military defense efficiency and optimizing strategic deployment strategies.

Firstly, in terms of spatial representation, the Great Wall heritage in Yansui defense district exhibits a layout characterized by the integration of high-density frontline defense and in-depth strategic support within its spatial pattern and density distribution. Horizontally, the overall density of the Great Wall heritage decreases from northeast to southwest. High-density sections of the major frontier wall align with topographic features, particularly at significant turning points in the topography. The distribution density of beacon towers follows the same pattern, decreasing from northeast to southwest, while the density of watchtowers shows the opposite trend. During the Ming Dynasty, beacon towers and watchtowers, were collectively known as defense towers (named “Dun tai” in the Ming Dynasty). Some of them were constructed earlier than the major frontier wall, originally as independent facilities primarily for enemy warning and communication. As the major frontier wall constructed, the differences in landform had a profound impact on the layout of the defense towers: in flat terrain, most of them were able to connect with the walls and become crucial parts of the frontier wall system63; whereas in rugged and valley-ridden areas, the connection between the towers and the walls posed difficulties, and many remained scattered and independent of the walls. Over time, their functions gradually differentiated: watchtowers (including enemy towers built on the wall and horseface-shaped bastions attached to one side of the wall) focused on monitoring both sides of the wall and coordinated defense among adjacent towers. Beacon towers, independent from the frontier wall, served as the primary signaling entities. Consequently, the topographic variations between the eastern and Western Routes had not only an impact on the connection and arrangement of the towers but also resulted in significant disparities in their density distribution, further underscoring the pivotal role of topography in shaping the differentiation of military defensive capabilities.

In the depth direction, the various types of heritage extend along the Wuding River, stretching southeast into the hinterland. The closer to the Great Wall, the shorter the distance between defense units and the lower their hierarchical levels. When invaders targeted a strategic point along the Great Wall defense line, the frontier wall, along with the densely spaced watchtowers and passes, would be the first to face the attack, effectively impeding enemy advancement. At the same time, beacon towers acted as hubs for information transmission, quickly establishing a crisscrossing alarm network. Through the “watchtower/beacon tower–pass–fort” sequence, urgent battle reports were swiftly conveyed to all defense units. Upon receiving the beacon signal, these units at all levels rapidly activated response mechanisms based on the severity of the threat and predetermined defense strategies, converging on the point of attack and its surroundings24. This hierarchical system, with clear divisions of responsibility, effectively enhanced the overall efficiency and response speed of the defense system, providing solid support and sustained reinforcement for in-depth defense. Overall, although the various heritage types had different spatial distributions reflecting functional differences and complementarity within the defense system, they collectively achieved a high degree of balanced and coordinated layout, profoundly embodying the strategic characteristics of “Defence in depth”.

Secondly, the environmental preferences of the Great Wall heritage are characterized by a strategic adaptation to geographical features alongside human-oriented optimization, a balance that guided both defensive siting and sustainable settlement practices. Environmental data and simulation validation indicate that the distribution of the Great Wall heritage was constrained by the surrounding geographical environment. These topographic factors not only met the requirements for defense layout and early warning mechanisms but also considered the needs for living, settlement, and garrison farming, ensuring the maximization of military supply and resource utilization. Among these factors, elevation, slope, and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems significantly influenced site selection.

Kernel density estimation and partial correlation analysis showed that the statistical significance of the major frontier wall, watchtowers, and natural terrain was largely consistent, demonstrating good adaptation to the geographical environment. In the depth direction, the major frontier wall was often built along ridgelines or the highest points of mountains, with slope orientation and water sources having less impact on site selection. The wall either utilized natural escarpments as part of its structure or was situated on the more gradual slope of steep terrain. This design balanced construction convenience while effectively employing slope variations. These variations served to hinder cavalry from observing activities behind the wall and slowed their advancement, thereby allowing stationed soldiers the time needed to relay information and organize their defenses. Watchtowers tended to be located in high-elevation, gentle slope areas and were distributed more densely than the wall in areas with complex slope variations. The location of beacon towers was significantly influenced by a combination of elevation and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems. Although they also favored high-elevation, low-slope areas, beacon towers were not necessarily at the highest point of the terrain. This strategy ensured that their locations were highly consistent with the overall elevation trend, thereby achieving broader geographical monitoring and coverage. This finding corroborates existing research that suggests beacon towers tend to be distributed on the slopes flanking valley lines5.

Orientation analysis of the Great Wall heritage revealed a significant clustering toward the north, differing from the expected preference for the more habitable southern orientation. This discrepancy can be attributed to the strategic defense priority of the Great Wall layout, with site selection focused on facing the northwestern source of threats rather than solely seeking optimal sunlight. For instance, forts along the Wall were often located on slopes with gradients between 0.53° and 3.39°, and their orientations generally ranged from 25° north of east to 21° south of east. To compensate for the unfavorable orientation, some higher-elevation forts were built on relatively flat mountain tops to maximize sunlight exposure. However, despite partially mitigating orientation issues, these forts often faced limitations in expansion and frequently dealt with shortages of water and supply difficulties, leading to frequent relocations64. This phenomenon further demonstrates that under topographic constraints such as slope orientation, the GWMDS optimized site selection through human intervention to balance defense and survival needs.

The utilization of hydrographical systems was particularly significant in the eastern and central sections. Historically, roads formed along valleys created by river erosion, which were natural water collection areas and important transportation corridors connecting the major frontier wall with forts. These routes ran perpendicular or parallel to the wall, forming structural spatial units for military defense, economy, and ecology along the Great Wall65. Statistical analysis shows that the locations of beacon towers and forts were closely related to hydrographic systems, both concentrated within approximately 0.45 kilometers and 0.43 kilometers of the nearest water sources. Most rivers in the eastern section flowed from northwest to southeast, perpendicular to the Wall, with forts generally located on the northeastern slopes upstream, forming a northeast-high to southwest-low pattern. In the central section, river courses ran parallel to the major frontier wall, creating multiple small alluvial shoals at confluences. This topographic feature prompted forts and beacon towers to extend south-eastward into the interior along rivers such as the Wuding River. This extension effectively secured waterway routes while also controlling key overland routes, thereby achieving a strategic defense system that emphasized both water and land routes.

Thirdly, in the dimension of defense features, the Great Wall heritage demonstrates dynamic adjustments that respond to topographic differences and evolving defense needs. The geographical attributes of the natural environment were not only the foundation of the Great Wall’s heritage layout but also deeply influenced the attack strategies and path choices of opposing forces, thereby driving functional cooperation and dynamic adjustments within the defense system. The construction of the GWMDS aimed to effectively resist the southward incursions of northern nomadic tribes. Through historical examination of the military ecology of the Mongolian Plateau in the 15th-16th centuries, Mongolian tribes, relying on cavalry advantages, frequently employed “divided forces for combined strikes” mobile tactics, with their combat effectiveness highly dependent on the rapid advance and flanking capabilities of cavalry clusters. Given the temporal variability of regions attacked by nomadic peoples, the site selection for the Great Wall heritage needed to consider the spatiotemporal correspondence between invasion characteristics and defense requirements, efficiently integrating geographical resources across the three routes.

The Eastern Route featured complex terrain with numerous river valleys, which constituted important transportation routes for Mongolian southward movement in the early period, while also providing natural mountainous protection for the Ming military defense. Therefore, early military contention between the Ming dynasty and Mongolia basically centered around river distributions66. The construction of the Eastern Route fully utilized the natural advantage of these valley-dense areas, making elevation and hydrographic system distribution core considerations in site selection decisions. In the analysis of the combined effects of topographic factors, the generally significant partial correlation between elevation and the nearest distance to hydrographic systems along the Eastern Route also confirms this point. Compared to the central and Western Routes, eastern Great Wall heritage sites were particularly significantly influenced by hydrographic systems, with this correlation gradually decreasing from east to west. Against this strategic background, the mountainous terrain of the Eastern Route from Huangfu River to Shuangshan Fort section compelled the Ming forces to develop an elastic depth early warning system of “mountain formations controlling cavalry” by cutting off the Mongolian cavalry’s impact waves and limiting war horses’ maneuverability radius.

In the Western Route, which spans the Loess Plateau, the elevation rises significantly. The vast expansiveness of view to the north plains provided favorable conditions for rapid Mongol cavalry maneuvers, while the hilly landform of Baiyu Mountain to the south offered a concealed approach for enemy attacks. Consequently, in later periods of military confrontation, the western defense zone gradually became the main attack direction for Mongolian cavalry66. Facing complex and variable landform conditions and limited field of vision, Ming defense strategy shifted toward the selection of short-range weapons, prioritizing the construction of continuous frontier walls to restrict cavalry mobility, while increasing requirements on support and rapid response capabilities for the major frontier wall and internal defense areas. The number of watchtowers increased significantly, with closer positional relationships between them and shortened average distances, ensuring comprehensive coverage and efficient coordination of the defense network. The layout of the Western Route also became less fixed, with frequent adjustments to the locations of forts, resulting in a more dispersed distribution of defense heritage sites. Further analysis reveals that the partial correlation between elevation and slope is especially significant in the Western Route, which highlights the crucial role of the combination of elevation and slope in the process of site selection.

In response to highly mobile and unpredictable cavalry incursions, the allocation of resources across the three defense routes was constrained by the macro-environment while also being adjusted at the micro-level according to changing defense needs, demonstrating a high degree of strategic flexibility and topographic adaptability. Through dynamic optimization of the layout, the system made full use of topographic features, carefully selecting sites to balance defense and self-preservation to construct a dense defense network. This approach not only pushed the front line of conflict into advantageous positions but also ensured the stability, efficiency, and strategic initiative of the defense system.

The dialectical relationship of military geography described above drove the Great Wall defense system to form a unique resource allocation logic. Facing the uncertainty of cavalry invasions, the three-route defense zones both adhered to the macro constraints of topographic features while enhancing adaptability through micro dynamic adjustments. This composite strategy of “rigid strategic framework + flexible tactical components” enabled Ming forces to preset battlefields in geographically advantageous locations, optimizing defense through topography selection to minimize costs while maximizing combat effectiveness, ultimately constructing a frontier barrier that combined stability with strategic initiative. This dynamic interplay between geographical constraints and military strategy was historically verified in cases such as Wang Yue’s successful surprise attack on the Tatar camp at Hongyanchi in 9th year of Chenghua (1473 AD), where he leveraged mountainous terrain for concealed troop movements, and during the Jiajing period (1521–1567 AD) when various Mongolian tribes in the Hetao region had their offensive momentum delayed and obstructed by the western frontier wall. This differentiation was essentially the outcome of a strategic game between the nomadic economic raiding logic (Mongolians relying on mobility) and agricultural society’s defense expenditure constraints (Ming forces needing to balance fortification investment with garrison efficiency), highlighting the rigid shaping power that geographical environment exerted on frontier defense in the cold weapon era.