Abstract

This study applies the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) framework to evaluate fire safety risks in 36 historic buildings in Nan’an District, Chongqing, a mountainous urban area with complex geographical and environmental challenges. The research highlights the interplay between geographical clustering, environmental factors and fire safety infrastructure, revealing the tension between preserving the authenticity of heritage buildings and implementing modern fire safety measures. By integrating with field surveys, the study identifies and prioritises critical vulnerability factors. The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the AHP framework in systematically quantifying fire risks and providing actionable insights for decision-making. Recommendations are proposed to enhance fire safety, including tailored infrastructure improvements, strengthened management practices, and the integration of unobtrusive fire suppression technologies. This research contributes to the advancement of risk assessment methodologies in heritage conservation and offers a foundation for extending the AHP framework to other risk types or regional contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fire poses a significant threat to architectural heritage, particularly due to the construction techniques and materials used in different historical periods, which often lack modern fire-resistant properties. The vulnerability of heritage structures is evident from incidents such as the 2018 fire at Brazil’s National Museum, the 2019 Notre-Dame Cathedral fire and the 2022 destruction of Wan’an Bridge in China. These events highlight the need for comprehensive fire risk assessments tailored, especially for the vulnerabilities, to heritage buildings.

The architectural heritage of the 20th century, especially in China and East Asia, presents unique fire safety challenges due to the combination of traditional wooden elements with modern materials such as steel and concrete. These buildings often feature flammable materials, open spaces that facilitate fire spread, and outdated electrical systems. Compared with traditional architecture, buildings in China trend to be in a larger dimension and with integrated functions by entering 20th century, which enables more flexible revitalisation to them in contemporary era. This evolution and revitalisation practices provide further challenges to secure their fire safety. Furthermore, the absence of formal fire safety codes during this period exacerbates fire risks, necessitating assessments that respect the structures’ historical integrity while ensuring their safety1,2,3.

Mountainous heritage sites are facing heightened fire safety challenges due to the limit of their locations. The complex topography and isolation hinder emergency response, while ageing infrastructure and combustible building materials further increase fire vulnerabilities. As climate change intensifies wildfire frequency, protecting these culturally significant assets has become increasingly urgent4,5,6. However, existing fire safety regulations often fail to account for the unique characteristics of 20th-century architectural heritage, underscoring the need for tailored assessment methodologies2,7,8,9,10.

Research on fire safety in heritage buildings highlights the importance of balancing historical authenticity with effective risk mitigation. Tsui and Chow7 emphasise the necessity of performance-based fire safety approaches that integrate preservation priorities, while Kincaid8 discusses the conflicts between fire safety requirements and conservation principles. Garcia-Castillo, Paya-Zaforteza2 advocate for specialised fire vulnerability assessments that address the unique vulnerabilities of heritage structures, particularly in mountainous areas. Zhang and Wei6 further highlight the need for adaptive fire protection strategies that account for limited accessibility, water scarcity, and environmental factors such as wildfires and lightning strikes. In response to these challenges, UNESCO’s Fire Risk Management Guide5 recommends lightning protection systems and accessible emergency routes.

Various fire risk assessment methods have been applied to heritage buildings, including the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Cultural Property Risk Analysis Model (CPRAM), Fire Risk Assessment Method for Heritage Buildings and Risk Awareness Profiling Tool (RAPT). Among these, AHP stands out for its ability to systematically prioritise fire risks by decomposing complex problems into hierarchical sub-problems. This structured approach ensures a balanced consideration of structural vulnerabilities, historical significance and potential fire hazards11,12,13. Naziris, Lagaros14 further demonstrated the effectiveness of AHP in assessing fire safety for cultural heritage structures, applying a resource allocation model to optimise fire protection measures at the Mount Athos monastery of Simonos Petra.

Lamat, Kumar12 demonstrated the effectiveness of AHP in evaluating wildfire risks using remote sensing data, while Cucco, Di Ruocco9 applied a performance-based fire prevention model to heritage buildings in Italy. Zhang and Wei6 designed a three-dimensional disaster prevention system for Chongqing integrates fire safety planning into the urban fabric, offering insights into adapting fire protection strategies to steep terrains. Additionally, digital technologies such as high-resolution satellite imagery, fire simulation software and evacuation simulators have enhanced fire vulnerability assessments by providing detailed insights into localised fire dynamics and evacuation scenarios15,16,17,18,19,20.

This study aims to assess fire vulnerability in 20th-century architectural heritage in Nan’an District, Chongqing, using the AHP framework. It will identify fire hazards and vulnerability factors specific to these structures, analysing how architectural design, material composition and structural characteristics influence fire safety. By defining, weighting and ranking key indicators, the study will prioritise vulnerabilities, compare fire risk levels across different buildings and identify high-risk structures. The innovative application of the AHP framework in this context, which has received limited attention, provides a structured approach to balance fire safety and conservation. The findings will offer practical recommendations for enhancing fire safety while preserving historical integrity, supporting heritage managers, local authorities, and stakeholders in implementing effective fire resilience strategies.

Methods

Study Area and Cases

Nan’an District is located in the southern part of Chongqing, a major municipality in southwest China. Positioned along the southern bank of the Yangtze River, the district serves as a vital connection between the city’s urban core and its surrounding regions. As part of Chongqing’s central urban area, Nan’an District enjoys a strategic geographical location, benefiting from its proximity to the city’s commercial hubs and cultural landmarks. Known for its unique topography, with rolling hills and riverfront areas, the district represents a blend of historical charm and modern development, making it an integral part of Chongqing’s urban landscape.

The district’s transformation from a rural area to an urban centre was notably influenced by the opening of Chongqing as a treaty port in 1891, which facilitated increased trade and interaction with foreign entities. This period saw the construction of various buildings that combined Western architectural styles with local design, serving functions such as customs houses, foreign firms, military camps, and churches. These structures were typically situated in areas like Longmenhao, which became prominent gathering places for foreign businesspeople and were among the earliest to be exposed to Western culture21. During the early 20th century, Nan’an District continued to develop as a vital conduit between Chongqing’s urban core and its peripheral regions, facilitating both economic and cultural exchanges22. The district further developed its importance during Chongqing’s tenure as a provisional capital during the World War II further formulate Nan’an’s historical and cultural significance in modern political and diplomatic activities.

Nan’an District is characterised by a diverse collection of 20th-century heritage buildings that reflect the historical and architectural evolution of the region. The selected 36 buildings for this study are representative historic buildings and structures in Nan’an District, which itself serves as a representative mountainous urban area. The selection includes scheduled architectural Heritage Sites (文物保护单位) classified as Representative 20th Century Monuments and Buildings (近现代重要史迹及代表性建筑) in the district, with a few listed or normal historic buildings as supplement. These buildings studied in this research are distributed across various locations in Nan’an District, including riverfront plains, mountain slopes and hillside terraces. This distribution ensures a representative sample of the region’s diverse topography. Furthermore, these buildings exhibit a variety of architectural styles, materials, construction techniques and functions, making them a comprehensive representation of modern historic buildings in mountainous areas. The details about the surveyed heritage buildings of this research are listed in Table 1. These heritage buildings can be categorised into four primary types according to their material and structure: masonry, timber, concrete and brick-concrete. Among these, brick-concrete buildings dominate, reflecting a transitional phase in construction practices as the region embraced more durable materials in the 20th century. Masonry buildings, often utilising stone or brick, illustrate traditional construction techniques, while timber structures highlight the continued use of traditional materials in specific contexts, such as temples or older residences. Concrete structures represent a shift towards modern construction methods, emphasising the evolving architectural landscape of the region. In terms of material composition, most buildings utilise a combination of brick and concrete, reflecting the adaptive use of materials during this era. These mixed-material buildings serve as key examples of architectural evolution in Nan’an District, bridging traditional methods and modern innovations.

Functionally, the heritage buildings encompass a diverse range of uses (Fig. 1), including residential villas (e.g., the Villa of General Post Office), institutional buildings (e.g., the former campus of Chunghua University), diplomatic sites (e.g., former embassies), military facilities (e.g., Former French Navy Barracks), industrial or commercial workshops (e.g., Héjì Duīdiàn) and cultural or religious landmarks (e.g., temples like Ciyun Temple). This functional diversity underscores the historical significance of the district while adding complexity to preservation and fire vulnerability assessment, as each building type presents distinct vulnerabilities based on its original purpose and materials. By understanding the specific characteristics of each building type, conservation strategies can be tailored to address the unique vulnerabilities associated with each structure.

The heritage buildings surveyed in this study encompass a diverse range of uses, including residential villas (Villa of General Post Office), institutional buildings (Former Temporary Campus of Chunghua University), diplomatic sites (Former Site of Soviet Embassy), military facilities (Former French Navy Barracks), industrial or commercial workshops (Héjì Duīdiàn) and cultural or religious landmarks (Ciyun Temple).

The location of these historic buildings is distributed across distinct terrain-based clusters (Fig. 2), each with unique environmental conditions that influence their preservation needs. The riverfront plain clusters, such as Longmenhao, Mishi Jie, Danzishi and Cuiyun Temple, are situated on flat terrain along the Yangtze River. These areas historically benefited from easy trade access. The mountain slope clusters, including Chongqing Historic Sites Museum of Resistance against Japan (CHSMRJ) and Nanshan Botainic Garden, are located on steep, forested slopes. Buildings here are adapted to rugged terrain, offering strategic views but dealing with significant accessibility challenges and heightened maintenance demands due to the steep, natural landscape. Lastly, the hillside terrace clusters, located in areas like Huangjiaoya and Chongqing Image, are positioned on moderate slopes that allow for terraced architecture, balancing scenic views with manageable elevation. However, hillside clusters still encounter issues related to soil stability and erosion. These classifications—riverfront plains, mountain slopes and hillside terraces—highlight the diverse environmental factors impacting Nan’an’s heritage sites, each requiring tailored conservation and fire safety strategies to address their specific challenges.

The central panel shows the general distribution of the surveyed heritage sites, and the panels on the both sides shows the distribution of the sites in the clusters. Upper left: Danzishi and Ciyun Temple; upper right: CHSMRJ; middle left: Mishi Jie and Longmenhao; middle right: Nanshan Botanic Garden; lower left: Chongqing Image; lower right: Huangjiaoya.

The district’s architectural diversity and topographical variations present unique challenges for fire safety in architectural heritage. Unlike flat terrains, buildings in mountainous areas require three-dimensional fire prevention strategies to address elevation differences and accessibility issues. For instance, research on Chongqing’s hillside buildings emphasises the need for adaptive fire protection designs that consider the city’s topography, advocating for a tri-level, networked urban fire protection plan integrating land, water, and air resources6. Additionally, the design of fire safety facilities must harmonise with the overall aesthetic of historical districts to preserve their cultural integrity. Studies on Chongqing’s mountain cities highlight the importance of integrating fire prevention measures with the ecological and intensive design tactics of the region, ensuring that safety enhancements do not detract from the area’s historical character23.

Additionally, the locations of these heritage buildings span both urban and semi-urban settings, presenting a spectrum of accessibility challenges that impact emergency response times and the effectiveness of fire safety interventions. Some buildings are situated close to firefighting resources, while others are more remote, illustrating how location influences the practicality of fire safety measures. Moreover, the fire safety infrastructure across these buildings varies significantly. While some structures have been retrofitted with modern fire suppression systems, others lack such updates due to the challenges in adapting historic structures to contemporary standards. This variability underscores the need to assess current fire safety provisions in heritage sites and identify areas for improvement. Existing research has underscored the importance of assessing and enhancing current provisions24.

Together, these factors make Nan’an District an ideal case for exploring the complex interplay of building type, location, and fire safety measures, ultimately informing more nuanced and effective conservation strategies for 20th-century heritage buildings.

AHP-based assessment framework

The AHP-based framework developed in this study systematically identifies vulnerability factors in heritage buildings, particularly within the mountainous terrain of Nan’an District. This approach integrates regulatory guidelines, academic research, and the district’s unique topographical challenges.

Regulatory standards for built heritage form the foundation of the framework. A pilot guideline25 for fire safety design published by National Cultural Heritage Administration in 2015 categorises vulnerability factors to fire into four: fire hazards, building fire prevention, fire service capabilities, and fire safety facilities26. Among these, building fire prevention includes building dimensions, materials and fire resistance, fire compartments, fire separation distances, and evacuation conditions. Fire service capabilities mainly encompass the condition of fire stations and equipment, existence of fire control rooms, and accessibility to fire service. The status of fire service facilities includes water supply, fire extinguishing systems, and automatic alarm systems. Fire hazards mainly refer to flammable materials and the use of fire and electrical applicants. Some local standards emphasised the importance of fire safety planning27. Shanghai’s Technical Standard for Fire Protection of Heritage Buildings and Historic Buildings further optimised evaluation indicators for the fire safety status and considered the general condition and historical fire incidents of historic buildings on the basis of the national guideline.

Academic research further refines the framework, but the category could be various. Studies on traditional village fire vulnerability evaluation models group indicators into building characteristics, fire hazards, and fire protection measures28. Research on historic districts identifies major evaluation dimensions, including building characteristics, internal fire hazards, usage activities, and surrounding environmental hazards29. There is also research summarised into six categories: surrounding environment, building material, fire hazard, fire safety facility, fire service capability, management for fire safety30.

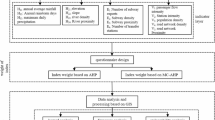

Regarding to the realistic condition of the built heritages in Nan’an District and previous relevant studies, a purposed fire safety factor framework for AHP assessment is formulated as Fig. 3, which contains 23 items and is categorised into 3 tiers. This comprehensive approach ensures that the diverse factors influencing fire safety in heritage contexts are adequately addressed, with particular attention to the unique challenges presented by Nan’an District’s mountainous geography. The weights for each factor is acquired from an expert survey, and will be explained in later sections.

Particularly, the framework incorporates strategies to address elevation differences and accessibility challenges, given Nan’an District’s mountainous terrain. Research on fire safety in mountainous heritage sites highlights the need for adaptive fire protection designs that consider topographical factors, advocating for a tri-level, networked urban fire protection plan integrating land, water, and air resources7. A critical aspect of fire vulnerability assessment in such terrain is the consideration of fire station accessibility. The framework acknowledges that the effective distance to the fire station is not merely a straight-line measurement but rather the actual circuitous path that fire engines must traverse to reach the site. This accounts for winding roads, slope inclines, and potential obstructions that significantly affect response time. Additionally, the width of access routes outside the built heritage site is a crucial factor, as it determines whether fire engines and emergency vehicles can effectively navigate the area. The challenges posed by narrow, steep, or unpaved roads in mountainous regions further highlight the necessity of incorporating these spatial constraints into vulnerability evaluation. Furthermore, the framework considers the distinction between fire stations located within the heritage site and those situated externally. In some cases, fire stations inside the site may provide quicker response times, yet external stations might struggle to access certain mountainous locations due to terrain barriers, road connectivity limitations, or the presence of heritage structures that restrict movement. These factors underscore the importance of context-specific fire vulnerability assessment models that integrate topographical analysis alongside conventional fire safety parameters.

Data collection and analysis

To ensure a comprehensive and scientifically sound assessment of fire vulnerabilities in heritage buildings, this study utilised a combination of archival data, field surveys, and expert opinions. These diverse data sources were systematically integrated within the AHP framework to facilitate an in-depth analysis.

A field survey on the built heritages listed in Table 1 was conducted from 14 to 16 August 2024 by two experts in built heritage with substantial experience in fire safety evaluations. The survey focused on assessing the condition of predefined fire safety factors, including building materials, fire compartments, evacuation conditions, and firefighting infrastructure. These conditions were recorded using a structured grading form (Table 2), where each grade corresponded to a specific score. In practical assessments, many indicators inherently possess fuzziness and uncertainty, making it difficult to fully refine and absolutised evaluation criteria. The concept of the ‘fuzzy set’ is adopted to the grading form, with continuous-value indicators corresponding to specific indicator ranges for each evaluation level. The grading system allowed for a quantitative evaluation of fire safety conditions, enabling a standardised comparison across multiple heritage sites.

To develop a comprehensive fire vulnerability evaluation framework, this study conducted a survey among 13 professionals specialising in fire safety and built heritage conservation from authoritative institutes (eg. top universities, academies, professional organisations and design institutes). These experts selected based on their extensive qualifications – at least three years of relevant working experience or a PhD in the field – were tasked with assessing the relative importance of various fire safety factors. The survey employed the pairwise comparison method, a core component of the AHP framework, which required the experts to compare fire safety factors in pairs. The results were used to calculate weighted importance scores, ensuring a robust foundation for the framework.

The evaluation framework, grounded in methodologies from previous studies on building fire vulnerability assessment31, is organised into four hierarchical levels. The first level represents the overarching goal: building fire vulnerability assessment. The second level comprises six Tier 1 factors in Fig. 3: surrounding environment, building material, fire hazard, fire safety facility, fire service capability, and management for architectural heritage. These Tier 1 factors are further refined into more specific sub-factors in the third and fourth levels, providing a detailed structure for evaluation.

Each indicator within the framework influences the indicators at the preceding level. For example, the use of open flames contributes to the fire hazard, which subsequently impacts the overall building fire vulnerability level. To ensure a systematic and consistent evaluation, fire safety researchers scored each indicator at every level based on its relative importance to the indicators above it. The scoring criteria, detailed in Table 3, integrate expert insights and hierarchical analysis to establish a scientifically rigorous and practical tool for assessing fire vulnerabilities in heritage buildings.

The data collected from the field survey and expert opinions were integrated into the AHP framework for analysis. The field survey scores provided a quantitative basis for evaluating the current conditions of fire safety factors, while the expert survey results informed the weighting of these factors within the hierarchical structure. Consistency checks were performed on the pairwise comparisons to ensure the reliability of the expert judgments. The final analysis involved synthesising the scores and weights to rank the overall fire vulnerability levels and identify critical areas requiring immediate attention.

This multi-method approach, combining empirical observations with expert judgment, ensured a robust and balanced assessment of fire safety vulnerability tailored to the specific challenges of heritage conservation. By leveraging the AHP framework, the study systematically prioritised fire safety interventions, aligning with both scientific rigor and practical conservation needs.

Application of the AHP framework

In order to quantitatively evaluate the fire vulnerability of historical buildings in the case, it is first necessary to construct a judgment moment for pairwise comparison of building vulnerability indicators based on the results of expert surveys and construct an evaluation factor set.

First, according to the building fire vulnerability evaluation system constructed above, the evaluation factor set U is established. \(U=\,\left\{A,{B},C,D,E,F\right\}\), where U represents the building fire vulnerability level; A represents the surrounding environment; B represents the building material; C represents the fire hazard; D represents the fire safety facility; E represents the fire service capability; F represents the management for architectural heritage. Second, the weight of the evaluation index is determined. According to the 5 importance levels and their values given in Table 3, as shown in Table 4.

Based on the geometric mean axy value corresponding to the answers from 13 professionals of each factor above, a judgment matrix of the importance of Tier 1 factors is constructed. The numbers in the table represent the importance of the indicators in the horizontal rows relative to the indicators in the vertical columns, as shown in Table 5.

After determining the importance judgment matrix of factors, mathematical consistency check is implemented to confirm the correctness of the basic mathematical logic and avoid inconsistent logical relationships. The consistency of the judgment matrix is then verified by calculating the largest eigenvalue (\({\lambda }_{\max }\)), whose calculation is based on eigenvalue decomposition.

The importance judgment matrix \(A\) (Table 5) satisfies the reciprocity property, indicating that each element \({a}_{{ij}}\) and its counterpart \({a}_{{ji}}\) are reciprocal. The eigenvalues \(\lambda\) of \(A\) are obtained by solving the characteristic equation:

where \(I\) is the identity matrix of the same order as \(A\), and \(\det (\cdot )\) denotes the determinant operation. Solving this equation yields six eigenvalues: 6.0154, −0.0035, −0.0035, −0.0081, −0.00017, −0.00017. Among them, the maximum eigenvalue is 6.0154. Based on this, the consistency index (\({CI}\)) is computed using Eq. 2:

The corresponding random consistency index (\({RI}\)) for a 6 × 6 matrix is 1.24. The consistency ratio (\({CR}\)) is then calculated as:

Since the \({CR}\) value is significantly less than 0.1, the consistency of the judgment matrix is deemed acceptable, indicating that the pairwise comparisons are logically consistent, and no further adjustments are required.

Each column of each matrix is normalised according to the Eq. 432:

where the sums of the columns of the first judgment matrix for the Tier 1 factors are 6.2789, 6.1257, 5.3310, 6.2267, 5.9457 and 6.3076 respectively. After the matrix is normalised, the new matrix is shown in Table 6.

The normalised matrix is summed horizontally to obtain the eigenvectors, which are: 0.9598, 0.9807, 1.1298, 0.9678, 1.0106, 0.9514. The eigenvectors are summed to obtain the weighted vector 6. The calculated eigenvectors are normalised to obtain the weights of the six Tier 1 factors, which are: 0.1600, 0.1634, 0.1883, 0.1613, 0.1684, 0.1586.

By using the same approach, the weights for the remaining Tier 2 and 3 factors can be calculated, as the numbers shown next to the factors in Fig. 3, and the normalised weight coefficient values of all factors are obtained, as shown in Fig. 4.

With the weight coefficients for all fire safety factors determined, the on-site survey scores for the 36 heritage buildings selected as case studies were calculated. These calculations provide a comprehensive evaluation of each building’s fire safety conditions based on the six Tier 1 factors. Additionally, an overall fire safety score for each building was derived by integrating the scores from these primary factors. The exact scores for each of the 36 buildings are detailed in Table 7 below.

During the on-site survey, the scoring system was designed such that the best condition for any fire safety factor was assigned a score of 5, while the worst condition received a score of 1, as outlined in Table 3. Consequently, the scores derived from the weight coefficients for all fire safety factors are continuous values ranging between 1 and 5. A score of 1 indicates the poorest condition, 5 represents the best condition, and 3 denotes a moderate condition. This grading system ensures a nuanced and precise representation of the fire safety status of each building, facilitating a thorough comparison and prioritisation for targeted interventions.

Results

Findings

In the expert survey, the importance of various fire safety factors for built heritage in mountainous urban areas is revealed using weight coefficients. These coefficients, derived from the pairwise comparison method within the AHP framework, reflect the collective perspectives of fire safety and built heritage professionals, offering insights into their priorities for mitigating fire vulnerabilities under the unique conditions of such regions.

Among the Tier 1 factors (Fig. 3), Fire Hazard (0.1883) is significantly at the top of the experts’ priorities due to its direct influence on fire ignition and spread. The use of open flames, electrical appliances, and flammable material inside the building are seen as critical contributors to fire vulnerability. The following is Fire Service Capability (0.1684), which reflects the importance of timely and effective emergency responses. The accessibility to fire stations and the adequacy of firefighting equipment as essential for controlling fire incidents, especially in the challenging terrain of mountainous areas where logistical delays can have severe consequences (Figs. 5, 6). Building Material (0.1634) is also regarded as highly critical, as it directly relevant to the flammability of the structure (Fig. 7). The significance of using fire-resistant materials to mitigate the flammability of structural elements, partition walls, and interior furnishings is noted. Fire Safety Facility (0.1613) is another key consideration, as it encompasses the presence of automatic fire alarms, extinguishing systems, and other essential equipment. Effective safety facilities enable early detection and response, particularly in remote areas where delays in firefighting accessibility are common (Fig. 8). The This is particularly crucial in densely built heritage clusters, which are typical of mountainous urban areas. While still important, Surrounding Environment (0.1600) directly affects the potential for fire spread. It is necessary to manage external hazards, such as the presence of flammable materials and the adequacy of fire separation between buildings. Finally, Management for Architectural Heritage (0.1586) is slightly less critical compared to the factors above. Nevertheless, robust management strategies, including effective governance, property protection levels, and appropriate building utilisation, can balance fire safety with the conservation of cultural and historical values. In summary, among the Tier 1 factors experts prioritise the ones that directly influence fire ignition, spread and response capabilities, placing Fire Hazard as the most critical consideration, following with Fire Service Capability, Building Material, and Fire Safety Facility. Surrounding Environment and Management for Architectural Heritage, while also important, are viewed as supporting factors that complement the overall fire safety strategy.

While comparing the subdivided factors using the homogenised weight coefficients (Fig. 4), the results indicate that experts prioritise factors related to environmental hazards and structural vulnerabilities. Inflammable and explosive materials in the environment (0.1054) and flammability of structural elements (0.0950) are ranked as the most critical. These findings highlight the experts’ concern over the heightened vulnerabilities to fire posed by materials that facilitate fire ignition and spread, particularly in the compact and clustered building layouts common in mountainous areas. Additionally, the importance assigned to material of partition wall (0.0684) and adequate fire separation from surrounding buildings (0.0546) reflect an emphasis on mitigating fire propagation, a challenge exacerbated by the constrained topography of mountainous regions. Moderately ranked factors, such as level of protection for built heritage (0.0654), types of firefighting equipment at the nearest fire station (0.0452), and distance to the nearest fire station (0.0444), underscore the experts’ focus on enhancing both active and passive fire safety measures. These findings suggest the need for tailored firefighting resources and strategic placement of emergency services to address the logistical challenges posed by steep terrains and limited accessibility. Building function (0.0611) and interior furnishing (0.0451) show the importance of proper utilisation of historic buildings. Lower-weighted factors, including ownership of property (0.0320), indicate that while these aspects are relevant, they are considered less impactful compared to systemic or environmental factors. Installation of automatic fire alarm systems (0.0235) and basic firefighting equipment installations (0.0114) are also assigned lower weights, suggesting that while these are necessary components, their contribution to overall fire safety is less significant than broader systemic measures.

In conclusion, the expert survey results underscore a consensus among professionals that environmental hazards, structural vulnerabilities, and the integration of strategic fire safety systems are of paramount importance for the fire safety of built heritage in mountainous urban areas. Experts advocate for a prioritised approach focusing on reducing combustible materials, enhancing structural fire resistance, and improving emergency response capabilities tailored to the unique challenges posed by steep and inaccessible terrains. These findings provide a valuable foundation for developing targeted, context-sensitive fire safety strategies.

Among the 36 heritage buildings analysed in this study, their geographical distribution demonstrates a clear clustering pattern, as shown in Fig. 2. This clustering is not only evident in the physical distribution of the buildings but also reflected in their calculated fire safety scores. The fire safety scores, derived using the evaluation method employed in this research, exhibit a notable tendency to cluster geographically (Fig. 9). This correlation between fire safety scores and geographical groupings is likely influenced by shared conditions within the same cluster, such as similar firefighting accessibility, rescue capabilities and management practices. For example, buildings with higher fire safety scores (indicating lower fire vulnerability levels) are primarily found within the CHSMRJ cluster. Among these, the Hansui Pavilion achieves the highest score, representing the lowest fire vulnerability. This favourable score is not only a reflection of the broader advantages provided by the cluster but is also linked to the specific architectural and structural characteristics of the Hansui Pavilion itself.

Conversely, buildings with lower fire safety scores (indicating higher fire vulnerability levels) are concentrated within the Longmenhao and Chongqing Image clusters. Notable examples include the Former Site of the Belgian Embassy and Xuelu, both of which exhibit the lowest scores among the assessed heritage buildings. This concentration of higher fire vulnerability within these clusters suggests that certain shared challenges, such as limited firefighting infrastructure, less effective management practices, or higher density of combustible materials, may contribute to the increased vulnerability of buildings in this area.

To further understand the vulnerability distribution, the average fire safety scores for each geographic cluster were calculated. This analysis highlights the overall fire safety conditions of the clusters and allows for comparisons between them (Fig. 10). The CHSMRJ cluster has the highest average vulnerability score of 3.94, indicating the lowest vulnerability among the clusters. This reflects the presence of favourable conditions such as well-maintained fire safety infrastructure, effective management practices, and architectural features that mitigate fire hazards. The Mishi Jie and Danshizi clusters follows closely with a score of 3.71 and 3.68, also suggesting a strong emphasis on fire safety measures within this area. Clusters such as Huangjiaoya (3.55), Chongqing Image (3.52), Nanshan Botanic Garden (3.50), and Ciyun Temple (3.43) exhibit moderate fire safety scores. These clusters are characterised by reasonably effective fire safety measures, although there may be some areas requiring improvement. The Longmenhao cluster has the lowest average score of 3.30, indicating the highest vulnerability among the clusters. This score suggests challenges such as inadequate firefighting infrastructure, limited access for fire services, or other vulnerabilities specific to this area.

While variations in scores are observed among individual buildings and clusters, it is significant to note that all scores exceed 3. This indicates that the fire vulnerability levels of the assessed buildings are generally moderate to low. Even the building with the lowest score, Xuelu, achieves a score of 3.03. This overall favourable fire safety condition across the 36 heritage buildings in Nan’an District can be attributed to several factors. Many of these buildings are officially designated as protected heritage sites or are situated within heritage conservation districts. This status likely ensures greater attention to fire safety measures, including improved fire management practices and the installation of protective infrastructure. Furthermore, the moderate to low vulnerability levels across the district reflect the impact of consistent conservation efforts aimed at maintaining the integrity and safety of these culturally significant buildings. Such findings underscore the importance of heritage protection policies in enhancing fire safety while preserving historical and architectural value.

Interpretation of findings

The results of the assessment of the 36 case studies reveal a strong correlation between vulnerability levels and location, with buildings within the same cluster exhibiting similar levels of vulnerability. The most disadvantaged area in terms of fire safety is the Longmenhao clusters, which consist of modern historical buildings that have undergone restoration and redevelopment (from 2018 to 2014). As authenticity in conservation was advocated, efforts to preserve the original structures, materials, and surrounding environments led to the minimisation of large-scale interventions. Consequently, the fire safety measures, such as the provision of fire access roads and indoor fire protection systems, do not fully comply with modern fire safety standards. Currently, with the area open for commercial use, the increasing foot traffic significantly heightens fire safety risks.

In comparison, the Chongqing Image cluster, another group of 20th-century buildings, is in a somewhat better situation. This area was developed earlier in 2016, with the historical buildings relocated from various parts of Chongqing. Prior to relocation, the site’s fire safety infrastructure was meticulously designed, and the terrain features fewer significant elevation changes than in Mishi Jie. During the relocation process, structural improvements were made, with some brick-timber structures being replaced by reinforced concrete, which allowed for better integration of indoor fire protection systems. Despite the extensive use of these buildings as kitchens, hotels, and restaurants, the vulnerabilities to fire in Chongqing Image are less severe compared to Longmenhao. However, this cluster demonstrates significant internal variation, as it includes both the lowest-scoring building, Xuelu, and one of the highest-scoring buildings, Wenchang Temple. This disparity is likely influenced by differences in building function and material composition, with commercial spaces carrying higher fire loads while religious or well-maintained heritage sites benefiting from stricter fire management measures. These cases clearly illustrate the inherent tension between preserving the authenticity of historic buildings and meeting fire safety requirements.

The CHSMRJ and Nanshan Botanic Garden clusters share a similar context, being located within urban parks. Their primary function is as public museums, rather than commercial spaces. Among these, the anti-war heritage sites have gained increasing prominence in recent years as key elements of Chongqing’s urban heritage conservation efforts. Many of these sites are currently undergoing or have recently undergone restoration, and visitor numbers have been steadily rising (Fig. 11). To mitigate fire vulnerabilities associated with increased usage, measures such as the installation of fire extinguishers and fire alarm systems could be implemented. In contrast, the Nanshan Botanic Garden remains largely unopened, with most buildings, such as the Former Site of the Spanish Legation (Fig. 12), still in a closed-off state and concealed within the forested area. While the electrical load is minimal in these buildings, their fire safety management is notably weaker.

In addition to the clustered buildings with distinctive regional characteristics, there are also scattered heritage buildings, such as the Former French Navy Barracks and Ciyun Temple. The Former French Navy Barracks and Ciyun Temple are located along the riverside, while the Former Residence of Li Kui’an is situated in an ancient town. The fire vulnerabilities in these sites vary based on their architectural features. For instance, Ciyun Temple, functioning as a religious site (Fig. 13), also accommodates residential, dining, and public-facing activities, leading to understandably higher fire loads.

It is important to highlight that, even when two clusters exhibit similar overall fire safety scores, their specific conditions and contributing factors can differ significantly (Fig. 14). For example, the clusters of Chongqing Image and Nanshan Botanic Garden have very close overall scores, with a difference of only 0.02, the smallest margin observed among all pairwise comparisons in this study. Despite this similarity in their aggregated scores, the underlying factors driving their performance reveal stark contrasts. Nanshan Botanic Garden performs well in Surrounding Environment, benefiting from low-density development, natural separation between buildings, and minimal human activity, which reduce ignition vulnerabilities. However, it performs poorly in the Fire Safety Facility category, indicating potential deficiencies in critical systems such as fire extinguishing equipment, alarm systems, or fire suppression mechanisms. These weaknesses highlight the need for targeted improvements to strengthen its fire safety infrastructure. Conversely, Chongqing Image exhibits an entirely different profile. This cluster is satisfactory in the Fire Safety Facility category, which suggests the presence of adequate firefighting systems and routine-maintained fire safety equipment. However, it underperforms in the Surrounding Environment category, potentially due to challenges such as inadequate fire separation distances, clustering of buildings, or the presence of inflammable materials in the immediate vicinity (Figs. 15, 16). Such environmental vulnerabilities may offset the advantages provided by its strong fire safety infrastructure, emphasising the need for a holistic approach to fire vulnerability mitigation that considers both structural preparedness and external hazard reduction.

Methodological Insights

The application of the AHP framework to fire vulnerability assessment has demonstrated notable strengths, aligning well with the expectations of this study. One of the key advantages of this approach lies in its ability to provide a structured and systematic method for evaluating complex, multi-dimensional factors. By breaking down the fire vulnerability assessment into hierarchical tiers, the AHP framework enables the quantification of diverse variables, such as environmental conditions, building materials, fire safety facilities, and management practices. This systematic structure facilitates a clear understanding of how each factor contributes to the overall fire vulnerability, allowing for more informed decision-making.

Another strength of the AHP framework is its capacity for prioritisation. Through pairwise comparisons and weighted scoring, the method identifies the most critical factors influencing fire safety vulnerability s. This backward analytical approach not only highlights key problem areas but also offers actionable insights into where interventions are most urgently needed. For instance, in this study, the framework was instrumental in pinpointing fire hazards and fire service accessibility as the highest priority areas, guiding targeted recommendations for improving fire safety in heritage clusters.

Despite its strengths, the application of the AHP framework is not without limitations. The reliability of the results is heavily dependent on the accuracy and consistency of expert judgments, which may be influenced by subjective biases or limited expertise in certain aspects of fire safety. Additionally, while the framework provides a robust quantitative analysis, it may not fully capture qualitative aspects of fire vulnerability, such as the cultural or historical significance of heritage buildings, which often require more nuanced consideration. Furthermore, the method’s reliance on pairwise comparisons can become cumbersome when dealing with a large number of factors, potentially impacting its scalability for broader applications. For example, if too many factors are considered simultaneously, the survey questionnaire required to evaluate these factors would need to be extensive and highly detailed. This increased complexity can make the questionnaire difficult to navigate, leading to confusion among respondents and reducing the clarity of their answers. Consequently, the accuracy and reliability of the collected response may be compromised, ultimately affecting the validity of the assessment results. The contrast on subdivided fire safety score according to six primary-tier factors among clusters with similar overall score underscores the complexity of fire vulnerability assessment in heritage clusters. Similar overall scores can mask significant disparities in specific fire safety dimensions, necessitating a nuanced approach to interpreting and addressing fire vulnerability.

In conclusion, the AHP framework is a highly effective tool for fire vulnerability assessment, offering a clear, quantifiable, and prioritised understanding of vulnerabilities. Its ability to pinpoint critical issues and guide decision-making makes it a valuable method for heritage conservation contexts.

Recommendations for conservation

The findings of this study highlight the tension between preserving the authenticity of heritage buildings and reducing fire risks. Addressing this challenge requires stakeholders, including local authorities and heritage conservation bodies, to adopt comprehensive and balanced approaches to fire safety improvements.

Firstly, mountainous heritage buildings require a three-dimensional protection strategy that extends beyond the preservation of the building itself to include its surrounding environment. This broader perspective is essential, as the integration of fire safety measures into the surrounding context enhances protection without compromising the heritage’s aesthetic and historical value. Stakeholders should prioritise infrastructure improvements that align with the heritage’s authenticity while effectively mitigating fire vulnerabilities and further fire risk.

Enhancing fire safety infrastructure is a critical priority, especially when the heritage building serves as a restaurant, where the fire load increases significantly. Local authorities should ensure the availability of adequate firefighting water sources and equipment close to heritage buildings. This could involve the installation of strategically placed fire hydrants, water tanks, and portable firefighting systems. These facilities are particularly vital in mountainous areas, where access can be challenging during emergencies. However, such infrastructure must be designed to blend harmoniously with the architectural and historical features of the site, avoiding any detrimental visual or physical impact. For example, setting watery landscape elements at the patios or around the buildings is a simple and feasible approach (Fig. 17).

Strengthening fire safety management practices is equally important. Heritage conservation bodies should conduct regular fire vulnerability assessments and implement comprehensive fire management plans. These plans should include routine inspections of fire safety equipment, clear emergency response protocols, and fire safety training for on-site personnel. Additionally, local communities and visitors should be engaged through fire safety awareness programmes, fostering a shared responsibility for reducing fire risks.

Balancing the authenticity of heritage buildings with modern safety requirements is another critical consideration. Improving the fire safety of heritage buildings does not mean to transform them into the spatial scale, fire protection requirements and material usage to completely meet the fire safety requirements for contemporary buildings, but rather at maintain their historic environment by improving the fire safety. Stakeholders should explore innovative solutions that preserve the historical and architectural integrity of heritage sites. For example, unobtrusive fire suppression technologies, such as concealed sprinkler systems or automatic fire alarms, can significantly reduce fire risks without compromising the heritage’s visual and structural authenticity.

Finally, collaborative efforts between stakeholders are essential to developing tailored fire safety solutions. Local authorities, heritage managers, and fire safety professionals must work together to address site-specific challenges, such as steep terrains and narrow access routes, which are common in mountainous areas. This cooperation ensures that firefighting strategies and equipment are customised to meet the unique needs of each heritage site.

Stakeholders need achieve a balance between heritage conservation and fire safety, safeguarding not only the physical structures but also the cultural and historical significance of these invaluable assets. This holistic approach ensures the protection and longevity of heritage buildings for future generations.

Discussion

This study applied the AHP framework to evaluate fire vulnerabilities in heritage buildings within Nan’an District, a mountainous urban area. The research provided a systematic and quantifiable method for assessing fire safety, addressing the complexities inherent in preserving architectural authenticity while ensuring fire risk mitigation. By integrating expert evaluations and field surveys, the study identified key vulnerability factors, prioritised interventions, and highlighted the interplay between geographical clustering, environmental conditions, and fire safety measures.

The findings emphasised the significant impact of factors such as fire hazards, fire service capability, and fire safety facilities. Clusters such as CHSMRJ and Mishi Jie demonstrated the tension between maintaining the authenticity of heritage buildings and implementing modern fire safety infrastructure. Additionally, the study revealed what site-specific conditions, including terrain and accessibility, influence fire safety outcomes, underscoring the need for tailored strategies for heritage clusters in mountainous areas.

One of the key contributions of this research is the demonstration of the AHP framework’s ability to systematically identify and prioritise fire vulnerabilities, offering a practical tool for decision-making in heritage conservation. The study also provided insights into the challenges of balancing preservation with modern safety requirements, particularly in the context of dense, historically significant urban environments. These findings can serve as a reference for policymakers, heritage managers, and fire safety professionals in developing integrated fire risk management strategies.

While this study focused on fire safety in Nan’an District, it opens up opportunities for further research. Future studies could explore the application of the AHP framework to other types of vulnerabilities, such as structural stability or climate-related hazards, to provide a more comprehensive approach to heritage protection. Additionally, extending this framework to other regions with varying geographical and cultural contexts would test its adaptability and contribute to a broader understanding of heritage risk management.

In conclusion, this research highlights the importance of a balanced, context-sensitive approach to fire safety in heritage buildings, particularly in complex urban and mountainous settings. By advancing the use of quantitative methodologies like the AHP framework, it lays the groundwork for more effective and sustainable heritage conservation practices.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- AHP:

-

analytic hierarchy process

- CPRAM:

-

cultural property risk analysis model

- RAPT:

-

risk awareness profiling tool

- CHSMRJ:

-

Chongqing Historic Sites Museum of Resistance against Japan

- PBD:

-

performance-based design

- BIM:

-

building information model

References

Approaches for the conservation of twentieth-century architectural heritage: Madrid Document 2011, (2011).

Garcia-Castillo, E., Paya-Zaforteza, I. & Hospitaler, A. Fire in heritage and historic buildings, a major challenge for the 21st century. Dev. Built Environ. 13, 100102 (2023).

Zhang, S. The Preservation of 20th-Century Architectural Heritage in China: Evolution and Prospects. Built Herit. 2, 4–16 (2018).

Falk, M. T. & Hagsten, E. Assessing different measures of fire risk for Cultural World Heritage Sites. Herit. Sci. 11, 189 (2023).

Yan, Z. & Mínguez García, B. Fire risk management guide: protecting cultural and natural heritage from fire. UNESCO; (2024).

Zhang, Q.-S. & Wei, H.-Y. The Characteristic Fire Protection Design of Mountainous City and Hillside Building-Illustrated by the Example of Chongqing. Procedia Eng. 11, 701–709 (2011).

Tsui, F. S. & Chow, W. K. Fire safety design for heritage buildings in Hong Kong. Fire Saf. Sci. 7, 102 (2007).

Kincaid, S. The upgrading of fire safety in historic buildings. Historic Environ.: Policy Pract. 9, 3–20 (2018).

Cucco, P., Di Ruocco, G. & La Rana, L. Proposal of an innovative model for fire prevention assessment in Cultural Heritage Protection. Research study in Italy. Int. J. disaster risk Reduct. 97, 104066 (2023).

University College London. SAFE Heritage Buildings: Sustainable Assessment of Fire Engineering London: University College London; 2022 [updated 23 September. Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/global/publications/2022/sep/safe-heritage-buildings-sustainable-assessment-fire-engineering (2022).

Wu, Y., Chen, S., Wang, D. & Zhang, Q. Fire Risk Assessment of Heritage Villages: A Case Study on Chengkan Village in China. Fire 6, 47 (2023).

Lamat, R., Kumar, M., Kundu, A. & Lal, D. Forest fire risk mapping using analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and earth observation datasets: A case study in the mountainous terrain of Northeast India. SN Appl. Sci. 3, 425 (2021).

Ramalhinho, A. R. & Macedo, M. F. Cultural heritage risk analysis models: An overview. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 10, 39–58 (2019).

Naziris, I. A., Lagaros, N. D. & Papaioannou, K. Optimized fire protection of cultural heritage structures based on the analytic hierarchy process. J. Build. Eng. 8, 292–304 (2016).

Mallinis, G., Mitsopoulos, I., Beltran, E. & Goldammer, J. G. Assessing wildfire risk in cultural heritage properties using high spatial and temporal resolution satellite imagery and spatially explicit fire simulations: The case of Holy Mount Athos, Greece. Forests 7, 46 (2016).

Naziris, I. A., Mitropoulou, C. C. & Lagaros, N. D. Innovative computational techniques for multi criteria decision making, in the context of cultural heritage structures’ fire protection: case studies. Heritage 5, 1883–1909 (2022).

Naziris, I. A., Mitropoulou, C. C. & Lagaros, N. D. Innovative computational techniques for multi-criteria decision making, in the context of cultural heritage structures’ fire protection: theory. Heritage 5, 1719–1733 (2022).

Guibaud, A., Mindeguia, J.-C., Albuerne, A., Parent, T. & Torero, J. Notre-Dame de Paris as a validation case to improve fire safety modelling in historic buildings. J. Cultural Herit. 65, 145–154 (2024).

Fafet, C. & Mulolli Zajmi, E. Qualitative fire vulnerability assessments for museums and their collections: A case study from Kosovo. Fire 4, 11 (2021).

D’Orazio, M., Canafoglia, M., Bernardini, G. & Quagliarini, E. Towards Using Digital Technologies to Balance Conservation and Fire Mitigation in Building Heritage Hosting Vulnerable Occupants: Rapid Evacuation Simulator Verification for the “Omero Museum”(Ancona, Italy). Heritage 7, 3734–3755 (2024).

Hong, L. Chongqing: Opportunities and Risks. China Q. 178, 448–466 (2004).

Zhang, H. editor Research on the Traceability of Buildings in Ma’anshan, Nan’an District, Chongqing. 2022 2nd International Conference on Modern Educational Technology and Social Sciences (ICMETSS); 2022: Atlantis Press. (2022).

Lu, F. & Jiang, M. Ecological and intensive design tactics for mountain cities in western China: Taking the main district of Chongqing as an example. Green City Planning and Practices in Asian Cities: Sustainable Development and Smart Growth in Urban Environments.:133–152 (2018).

Leung, W.-C. Fire safety management in heritage building: a case study. (2011).

Wenwu jianzhu fanghuo sheji daoze (shixing) [Fire safety design guidelines for heritage buildings (trial implementation)], (2015).

Li, M., Zhao, X. & Qian, J. Discussion on fire extinguishing design of traditional village and cultural relic building. Water Wastewater Eng. 43, 4 (2017).

Standard of fire prevention and control for traditional villages, DB52∕T 1504-2020 (2020).

Zhao, T. Research on Fire Risk Assessment Model of Traditional Village Buildings Based on FRAME Method: Capital University of Economics and Business. (2021).

Qin, R. Research on Performance Based Fire Prevention of Dense Historical Settlement using FDS Simulation: A Case Study of Xiaoxihu in Nanjing. Nanjing: Southeast University; (2021).

Sui, J. Fire Risk Assessment and Fire Protection Renovation Design of Traditional Villages in Southern Zhejiang. Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University; (2023).

Xu, J. & Liu, X. Design of Building Fire Risk Assessment Index System Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Wuhan. Univ. Technol. (Inf. Manag. Eng.). 41, 345–351 (2019).

Chang, J. & Jiang, T. Research on the Weight of Coefficient through Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Wuhan. Univ. Technol. (Inf. Manag. Eng.). 29, 4 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52408028), the Municipal Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX1377) and the Key Scientific Research Base of Urban Archaeology and Heritage Conservation (Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology), State Administration of Cultural Heritage (No. 2024CKBKF05). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tris Kee wrote the main manuscript text and designed the work. Bowen Qiu drafted the work and analysed and interpreted data. Qian Du acquired and interpreted data. Junwei Sui analysed data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kee, T., Qiu, B., Du, Q. et al. An application of AHP-based fire vulnerability assessment for 20th century mountainous built heritage. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 350 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01823-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01823-7