Abstract

The Tomb of King Muryeong and the Royal Tombs in Gongju, constructed during the Woongjin period (475–538 AD) of the Baekje Kingdom in ancient Korea, are UNESCO World Heritage sites. Tomb No. 5 deteriorated rapidly after being opened to the public without systematic conservation, leading to environmental and structural instability. To address this, long-term monitoring (2011–2022) assessed the impact of installing airtight windows. Results showed a partial reduction in environmental influences but minimal improvement in airtightness. Micro-movements of the tomb walls were linked to seasonal changes, external air, rainfall, and soil moisture. Heat transmission through materials also caused seasonal variations in internal wall separations. Despite improvements, the lintel stone continued subsiding, requiring further conservation. This study underscores the importance of precise and continuous monitoring for the long-term conservation of Tomb No. 5 and highlights the need for systematic conservation strategies to protect historic tombs from environmental and structural deterioration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

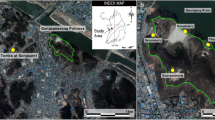

The Tomb of King Muryeong and the Royal Tombs in Gongju, located in South Chungcheong Province, comprise the tombs of kings and royal family members who reigned during the Woongjin period (475 to 538 AD) of the Baekje Kingdom in ancient Korea. Following its excavation, the research subject was designated as a national historical site in 1963 because of its historical and scholarly value, and was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2015.

It is believed that initially there were more than 20 tombs at this site, however, today only 7 tombs, including Tomb No. 5, No. 6, and King Muryeong, are preserved1. While Tombs No. 5 and No. 6, along with the Tomb of King Muryeong, are located relatively close to one another, their structural characteristics differ in some aspects. Specifically, Tomb No. 6 and King Muryeong were constructed using bricks, whereas Tomb No. 5 was built with gneiss (Fig. 1).

Structurally, Tomb No. 5 features an internal space arranged in a linear layout, resulting in a shorter and simpler distance from the entrance to the burial chamber compared to Tomb No. 6 and the Tomb of King Muryeong(Fig. 2). Additionally, the vertical height of the burial mound of Tomb No. 5 measures 2.28 m, which is significantly shorter than that of the Tomb of King Muryeong (3.77 m) and No. 6 (3.40 m).

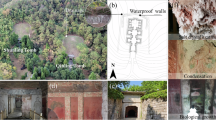

Following the excavation of the Tomb of King Muryeong, comprehensive restoration and repairs were carried out at the Royal Tombs of Gongju in 1971, and the study subject was publicly opened in 1973. During this period, the interior of the tombs underwent rapid environmental changes, leading to various damages. In particular, the increased soil moisture content of the upper burial mound during periods of heavy rainfall caused significant cracking and detachment of structural members. Additionally, direct water leakage into the tomb resulted in widespread efflorescence throughout the walls (Fig. 3)2,3,4,5,6,7. Consequently, the need for conservation scientific research and precise measurement monitoring were recognized, and a comprehensive detailed investigation was conducted in 1997, after which the study subject was permanently closed8,9.

A Cracks and break of stone properties. (B) Leakage and detachment of stone. (C) Efflorescence on the stone surface caused by water leakage. D, E Steel windows prior to environmental improvement. F, G PVC airtight windows after environmental improvement. This figure was created by the authors using original data and Adobe Illustrator CS6. No third-party copyrighted materials were used.

Recent advancements in sensor and monitoring technologies have enabled precise and continuous monitoring of architectural cultural heritage, including ancient tombs. Numerous studies have investigated the microclimate and structural movement of walls in such heritage structures, contributing significantly to their conservation10,11,12,13,14,15,16. These efforts aim to ensure the stable conservation and management of cultural heritage while preventing potential damage within the tombs17,18,19,20,21,22.

One prominent example of such applications is the Leaning Tower of Pisa in Italy, where sensors have been installed to analyze the relationship between temperature variations and structural movements. Similarly, in the UK, monitoring of Big Ben revealed structural movements influenced by anthropogenic factors23,24,25,26. For underground architectural structures similar to the research subject, studies on the Lascaux Cave in France have analyzed its microclimate characteristics to explore optimal conservation environments. Additionally, in Japan, environmental monitoring has been applied to the Takamatsutsuka Tumulus to ensure the stable conservation of tomb murals27,28.

Measurement monitoring of the study subject initially began in 1996 with the installation of a tilt sensor to monitor movement. In 2011, the monitoring system was expanded with the addition of humidity and temperature sensors inside the tombs, followed by the installation of additional tilt sensors in 20134,5,29,30. Furthermore, in 2016, the existing steel airtight windows (Fig. 1C, D) located at the entrances of each space within the tombs were replaced to enhance the stability of the conservation environment5,6,7. The new airtight windows were constructed from PVC, a durable and highly airtight plastic material designed to withstand high-humidity environments (Fig. 1F, G). They were implemented as outward-opening structures to improve sealing and insulation performance.

In this study, data were continuously collected using a precise monitoring system established to analyze the current status and changes inside the Tomb No. 5 after environmental improvement. In addition, by comparative analysis with previous research data, changes in the microscopic conservation environment according to environmental improvement were reviewed, and whether the micro-movement stability of the wall was improved was evaluated. The factors affecting the research subject were identified through a comparative review with various environmental factors.

The findings of this study will serve as baseline data for the long-term conservation management of the study subject and will be utilized to analyze future changes. Furthermore, these findings will contribute to a methodological approach applicable to the conservation management of similar ancient tomb heritage sites.

Methods

Recently, numerous studies have installed measurement sensors (tiltmeters, displacement meters, accelerometers) to observe displacements in masonry cultural heritage, examining structural deformations and natural frequencies31,32. Moreover, monitoring systems incorporating IoT technology have been developed to detect real-time changes33,34. Studies have also employed environmental monitoring systems to measure temperature and humidity, assessing the conservation environment and evaluating correlations with structural monitoring results35,36.

In this study, a monitoring system optimized for Tomb No. 5 in the Royal Tombs of Gongju was designed and implemented to collect long-term data on the microclimate and micro-movement characteristics of the tomb. Particular attention was paid to distinguishing between the periods before and after the Installation of Airtight windows (I.A.) to evaluate changes in the conservation environment and influencing factors. Additionally, an Automatic Weather System (AWS) was installed outside the tomb to collect external environmental data. For real-time remote monitoring, data measured inside the tomb were stored in a data logger (Campbell Scientific CR-1000, USA) and transmitted to the laboratory server via a CDMA modem for analysis.

Initially, data on the microclimate inside the tombs prior to the Environmental Improvement (E.I.) was analyzed using selected clean data collected from July 2011 to November 2015, while the characteristics of wall movement were analyzed using data collected from December 2013 to November 2015. After the E.I., the monitoring results from a reliable period spanning April 2016 to December 2022, approximately six years, were reviewed.

Environmental monitoring was conducted using temperature and humidity sensors (Vaisala HMP155, FIN), with 4 sensors installed inside Tomb No. 5. The AWS, which measured temperature, humidity, wind direction, wind speed, rainfall, and soil moisture, utilized the same temperature and humidity sensors as those inside the tombs. Additionally, a wind direction and speed meter (RM Young 05103, USA), a rain gauge (Seoul Electric RG50, KOR), and a soil moisture meter (Campbell CS616, USA) were used (Fig. 4).

Movement monitoring utilized a single-axis tilt sensor (Jewell Instruments, Model 84053 Ceramic Sensor, USA) and a displacement meter (Tokyo Sokki Kenkyujo PI-5, JP). Furthermore, a sagging displacement meter (Novotechnik TR-0050, USA) was installed on the lintel stone of Tomb No. 5 to analyze sagging movement. Currently, there are eight movement monitoring sensors installed in Tomb No. 5 (Fig. 4).

To ensure the consistency of measurement data, a real-time remote monitoring system was implemented for regular data collection and review. Immediate actions were taken in response to any sensor errors or malfunctions. Quarterly on-site inspections were conducted to maintain sensor accuracy, and sensor replacements and maintenance tasks were carried out in collaboration with expert engineers involved in the initial setup of the monitoring system. This approach ensured both reliability and professionalism throughout the process.

Results

Environmental monitoring

The microclimate characteristics within the Tomb No. 5 have been studied several times, and it has been established that the internal environment of the tombs exhibits a more stable temperature distribution compared to the external environment30. This study specifically focuses on examining the patterns of microclimate changes that have not been analyzed since prior research. Furthermore, since the relative humidity inside the tombs consistently approaches 100%, the analysis was primarily concentrated on variations in temperature across different areas, excluding humidity.

To examine the patterns of microclimate changes in Tomb No. 5 due to E.I., data collected before and after the I.A. were analyzed. Prior to the E.I. (2014 to 2015), the temperature in the burial chamber ranged from 11.7 to 17.8 °C during winter, which was higher than the external air temperature (−12.4 to 11.7 °C), while in summer, the temperature in the burial chamber (15.6 to 20.5 °C) was lower than the external air temperature (15.1 to 33.8 °C). After the I.A. (2016 to 2022), the monthly average temperatures in Tomb No. 5 ranged from a minimum of 13.0 °C to a maximum of 22.2 °C, showing an increase compared to the pre-installation range of 11.9 °C to 21.3 °C.

These characteristics were consistently observed in 2022 as well (Fig. 5). Based on this analysis, the stabilization of the conservation environment in Tomb No. 5 following the I.A. remains uncertain. To address this, further evaluation was conducted by comparing various environmental factors.

Effect of external air

Summarizing the effects of external air before the E.I., Tomb No. 5 (2011 to 2012) exhibited higher temperature ranges in the burial chamber (11.7 °C to 17.8 °C) compared to the external air (−12.4 °C to 11.7 °C) during winter, and lower temperature ranges in the burial chamber (15.6 °C to 20.5 °C) than the external air (15.1 °C to 33.8 °C) during summer. In spring and fall, a tendency for the internal and external temperatures to intersect was observed.

Inside the tomb, the temperature difference (ΔT) and standard deviation (SD) were significantly larger in winter (ΔT: 4.9 °C, SD: 1.6) and summer (ΔT: 6.1 °C, SD: 1.8) compared to spring (ΔT: 3.5 °C, SD: 0.9) and fall (ΔT: 3.3 °C, SD: 0.9), indicating greater instability. This suggests that convection between the tomb interior and external air was more active during winter and summer30. To ensure a continuous evaluation of these influences, additional analysis was conducted using data from 2022, which corresponds to the post-E.I. period.

As a result, in 2022, the maximum temperature in Tomb No. 5 increased by at least 1.9 °C and up to 2.2 °C compared to the period before the E.I. (2014 to 2015), and the minimum temperature was confirmed to be higher overall. The SD decreased by 0.1 °C during the summer, while in the fall and winter, it remained similar or showed a slight increase. However, in the spring, the SD increased by 0.2 °C compared to before the E.I., while the SD of the external air was lower than before the improvements, indicating that the conservation environment has not improved after the I.A. (Table 1).

To examine the relationship between the internal environment and the wind, days with strong wind influence were analyzed before and after the I.A. Tomb No. 5, with its entrance located to the south, was analyzed during periods when southerly winds were predominant. To unify meteorological conditions while excluding wind, data without rainfall were used. Before the E.I., Tomb No. 5 exhibited unstable temperature distributions on days with strong winds, and it was observed that the SD inside the burial chamber increased on days with high wind speeds30. This is believed to be a result of an increased amount of external air entering the tomb due to the influence of the wind.

To assess the changes in the conservation environment after the E.I., wind data from 2022 was analyzed. The results showed that the SD at the entrance of Tomb No. 5 on days with low wind speeds was 0.02 higher, while the exhibition room and burial chamber showed no difference. This indicates that the airtight windows reduced the impact of wind. Furthermore, it is interpreted that after the improvements, other environmental factors had a greater influence on the interior conditions than the wind (Table 2).

Influencing by rainfall

One of the major factors disrupting the conservation environment of the research subject is rainfall and the leakage caused by rainfall. In this study, to examine the impact of rainfall, the microclimate inside the tomb was analyzed based on measurements taken during three days without rainfall and three days with heavy rainfall. Before the E.I., data could not be collected due to the absence of AWS, but multiple traces of leakage caused by rainfall were reported in all areas of Tomb No. 55,13. The analysis after the E.I. was conducted over three days in 2016, during which approximately 199 mm of rain fell, and over another three days in 2022, during which a total of 236 mm of rain was recorded.

In 2016, leakage occurred in all spaces of Tomb No. 5 during rainfall, and the SD increased in all spaces compared to normal conditions. This instability in the internal environment is interpreted as the disruption of the conservation environment caused by leakage (Table 3). During the rainy season in 2022, the SD in the burial chamber and exhibition room of Tomb No. 5 increased by 0.01 and 0.04, respectively, while it decreased by 0.01 in the entrance (Table 3). Direct leakage occurred in the burial chamber and exhibition room, disrupting the conservation environment. In contrast, the amount of leakage in the entrance was minimal, resulting in less significant changes in the conservation environment compared to other spaces.

Impact of enter and exit

According to prior research before the E.I., it was reported that the internal temperature of the tomb temporarily increased due to the influence of carbon dioxide, water vapor, and body heat generated by human entry4,30. Before the installation of the airtight windows, there was no data available on the environmental changes in Tomb No. 5 caused by human entry due to device errors. Instead, the results from the nearby Tomb No. 6 and the Tomb of King Muryeong, which share similar environmental conditions, were referenced.

In Tomb No. 6, the temperature in the burial chamber increased by 1.1 °C when three people stayed for 20 min, and by 1.9 °C when they stayed for 90 min, indicating that the temperature rose proportionally with the time spent inside. Similarly, in the Tomb of King Muryeong, the temperature increased by 1.3 °C when three people stayed for 50 min, and by 1.0 °C when the same number of people stayed for 20 min. These results indicate that, when the number of people remains the same, the internal temperature of the tomb increases proportionally with the duration of stay (Table 4).

After the E.I., Tomb No. 5 was analyzed for two days in 2022 when people entered the tomb. The highest temperature increase of 1.7 °C was recorded on July 8, when the largest number of people stayed inside. Similarly, Tomb No. 6 was analyzed for two days when people entered, showing that the temperature changed proportionally with the number of people and the time spent inside (Table 4). In the Tomb of King Muryeong, on November 17, 2022, when two people entered for about 25 min to check the sensors, the temperature increased by 1.5 °C, showing a similar trend to the other tombs (Table 4). Such human entry raises the dew point temperature, which can cause condensation on wall surfaces that are cooler than the ambient air temperature. Therefore, entry into the tombs should be strictly limited, even for research purposes, to ensure conservation.

After the E.I., Tomb No. 5 was analyzed for two days in 2022 when people entered the tomb (July 8 and October 20). On July 8, when the largest number of people stayed inside, the highest temperature increase of 1.7 °C was recorded, showing the greatest change. The temperature was observed to change proportionally with the number of people and the duration of their stay (Table 4). Such human entry raises the dew point temperature, which can cause condensation on wall surfaces that are cooler than the ambient air temperature. Therefore, even for research purposes, entry into the tomb should be strictly limited to ensure conservation.

Structural variations by rainfall

Prior to the E.I., several studies had been conducted on the wall movement and influencing factors of the study subject2,4. However, subsequent continuous research has not been reported, indicating the need for further studies on wall movement. This study additionally examines the changes in wall movement after the E.I., focusing on the influence of environmental factors that had not been previously reported.

When rainfall occurs outside the tomb, in addition to disrupting the conservation environment, rainwater infiltrates the soil within the burial mound, increasing the soil moisture content. This leads to changes in earth pressure, which can cause movement in the internal walls. Therefore, rainfall and soil moisture data were collected along with movement monitoring, and these were examined in relation to the wall movement characteristics.

Prior to the E.I., Tomb No. 5 did not exhibit any noticeable abnormal movement during rainfall (Fig. 6). However, after the E.I., abnormal movement was observed in the 5-T2 tiltmeter of Tomb No. 5 during a period of decreasing soil moisture following heavy rainfall in July 2016. The displacement recorded at this time was ~0.38°, the largest change observed among the tiltmeter installed in Tomb No. 5 (Fig. 7). Additionally, in the 5-D1 displacement meter on the eastern wall, abnormal movement was detected in 2020 during the rainy season, with a displacement increase of 1.14 mm. This is interpreted as actual separation occurring in the tomb wall due to heavy rainfall exceeding 109 mm (July 13, 2020). Although stable conditions have been observed again since 2022, further monitoring is required to assess the progression of this displacement (Fig. 7).

The displacement of the walls inside Tomb No. 5 increased following rainfall after the E.I. This is interpreted as the result of increased upper load due to rising soil moisture content and changes in external forces during the soil drying process, which had a greater impact than the reduced effects of strong winds and pressure changes following the I.A. Rainfall and increased soil moisture are therefore considered environmental factors that contribute to abnormal wall movement. Consequently, scientific research on the upper mound, where actual leakage occurs, and on the waterproofing layer is essential. Conservation treatment should also be implemented for damaged areas of the waterproofing layer, along with further research in the future.

Microscale movement by human entry

When researchers entered the study subject, the internal temperature temporarily increased, and this temperature change was proportional to the number of people and the duration of their stay. Therefore, to understand the movement characteristics of the walls caused by entry, changes in wall movement were analyzed based on the times when people entered.

Prior to the E.I., changes in movement due to entry were observed in Tomb No. 6 and the Tomb of King Muryeong(Fig. 8). Although data on the movement of Tomb No. 5 could not be obtained due to sensor errors, it is presumed that similar characteristics would have been observed as in Tomb No. 6 and the Tomb of King Muryeong.

In the 2022 data after the E.I., wall movement due to human entry was observed inside Tomb No. 5. These changes were more clearly detected in the displacement meters than in the tiltmeter. The internal wall movement caused by human entry showed movements within ~0.01° and 0.001 mm, and after leaving, the walls stabilized and mostly returned to a steady state (Fig. 8). Additionally, the displacement caused by abnormal movement was very small, suggesting that it is unlikely to cause structural problems within the tomb. The displacement resulting from artificial factors is believed to be influenced by various simultaneous factors, including micro-vibrations caused by human movement and changes in temperature and humidity resulting from respiration.

Such artificial environmental changes affect not only the conservation environment of the study subject but also the micro-movements of the walls. Therefore, even for the purposes of investigation and management, minimizing the duration of stay inside the tombs is deemed desirable for long-term conservation.

Discussion

In 2016, airtight windows were installed inside Tomb No. 5 in the Royal Tombs in Gongju to minimize external influences. As a result, distinct temperature characteristics were observed in each space separated by the airtight windows, with more stable temperature distributions and lower SD as one moved from the entrance toward the burial chamber. However, in Tomb No. 5, no significant differences were observed after the I.A., and the improvement in airtightness was relatively minimal.

This is presumed to be related to the structural characteristics of Tomb No. 5, as it has a shorter distance from the entrance to the burial chamber compared to nearby tombs and the thinnest burial mound (No. 5; 2.28 m, No. 6; 3.40 m, King Muryeong; 3.77 m) making it more directly influenced by external environmental factors. As a result, it is interpreted to have a relatively less stable conservation environment (Fig. 3).

As a result of examining the environmental factors affecting the interior of the study subject, the inflow of outside air continued to affect the interior of Tomb No. 5 even after the I.A., showing only minimal improvement in airtightness.

Wind is a major factor that significantly influences the inflow of outside air into the study subjects. Before the E.I., the impact of wind was clear. However, after the improvements, the study subject exhibited instability on days with less wind, and the changes caused by wind were significantly reduced. This indicates that the airtightness of the interior improved following the E.I.

Changes in rainfall and soil moisture content are among the most influential factors affecting the interior of the tomb. After the E.I., the SD of temperature in the exhibition room of Tomb No. 5 increased during rainfall, indicating that the burial chamber continues to be more affected by rainfall even after the I.A. However, rainfall is more directly influenced by the condition of the burial mound and the waterproofing layer rather than the I.A. Therefore, the impact of rainfall should be further examined after conservation treatment or reconstruction of the waterproofing layer.

The impact of entry was proportional to the number of people and the duration of their stay, and these environmental changes stabilized as the temperature dropped immediately after leaving the room. Entry into the study subject was limited to specific conditions, such as internal investigations after its permanent closure, and over 11 years of monitoring (2011 to 2022), it did not significantly affect the conservation environment. However, entry increases the internal air temperature, creating a temperature difference with the walls, which can potentially lead to condensation on their surfaces. Such condensation has been observed during regular inspections. To minimize these effects, entry should be strictly limited, the number of people and duration minimized, and protective clothing and masks should be worn to reduce the effects of body heat and moisture caused by respiration.

As a result of examining four environmental factors, it was found that most factors influenced the internal environment of Tomb No. 5 before the E.I., with minimal improvement in the conservation environment observed after the I.A. (Table 5). Furthermore, environmental factors do not act independently but rather interact in a complex manner, collectively disturbing the conservation environment of the study subject. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of multiple factors, rather than focusing on individual factors, and continuous monitoring should be carried out in parallel.

After the E.I., changes in wall movement and influencing factors were analyzed, indicating that changes in rainfall and soil moisture content are the primary factors causing micro-movements and abnormal movement in the walls. While no significant displacements due to rainfall were observed before the E.I., relatively large displacements in the walls of Tomb No. 5 were observed in 2022, after the E.I.

Most abnormal movements returned to their original positions rather than resulting in permanent deformation after the E.I. Additionally, some displacements were observed during periods of increasing and decreasing soil moisture content. However, no significant trends or permanent deformations were detected by the sensors, except for the displacement meter in Tomb No. 5. Despite these observations, changes in rainfall and soil moisture content remain the most influential factors affecting the study subject (Table 5). To eliminate the root cause, in addition to the I.A., conservation treatments and reinstallation of the waterproofing layer inside the burial mounds are necessary, and the subsequent improvement in stability should be evaluated.

The interior of the study subject is a sealed space, maintaining a consistently controlled environment. However, when people enter, temporary changes occur, leading to slight movements in the walls. These micro-movements are presumed to result from the increase in internal air temperature caused by body heat and vibrations generated by human movement. While these changes are very minor, they have been identified as factors influencing wall movements.

Although no significant deterioration in wall stability due to human entry has been observed since the implementation of monitoring, the occurrence of such movements indicates the potential for cumulative risks over an extended period. Therefore, all entry into the tomb, except for investigative purposes, should be strictly restricted. In unavoidable cases, protective clothing must be worn, and the duration of stay should be minimized.

After the E.I., the displacement meters inside the study subjects showed a clear sinusoidal pattern the seasons, except for some instances of abnormal movement. The distances between internal members increased in summer and decreased in winter, with these increases and decreases intersecting in spring and autumn (Fig. 9A). This movement of the walls was also observed before the installation of the airtight windows.

A The pattern of increase and decrease in separation distance. B Position transducer installed in Tomb No. 5. C Sagging movement of the lintel stone in Tomb No. 5. This figure was created by the authors using original data, Adobe Illustrator CS6, and Microsoft Excel. No third-party copyrighted materials were used.

Generally, elastic materials such as those used in tomb construction expand at high temperatures and contract at low temperatures37. When this principle is applied to the interior of the study subject, the distance between members should show an inverse relationship with the internal temperature. However, actual monitoring results reveal outcomes contrary to this assumption (Fig. 9A). These results differ from the typical physical movement of elastic materials.

In addition, the dromos of Tomb No. 5 has developed cracks because of subsidence, leading to structural problems throughout the tomb. Accordingly, a sagging displacement meter was installed in the dromos to monitor changes in movement (Fig. 9B). The results show that the lintel stone in Tomb No. 5 continuously exhibits sagging movement regardless of the season or E.I. (Fig. 9C). This movement is one of the main factors contributing to the structural instability of the tomb.

Regardless of the E.I., conservation science considerations and structural issues have been identified within the study subject. Firstly, the seasonal distance between the members of the study subject shows results opposite to those of typical elastic materials. This movement is interpreted as being because of the differential thermal properties acting between the materials inside the burial mound and the construction materials of the tomb. The specific heat capacities of the materials that make up the mound (soil: 0.20 kcal/kg°C, gneiss: 0.22 kcal/kg°C) show minimal differences among them5,38,39. This means that the amount of thermal energy each material gains when the same amount of heat is applied is nearly identical. Thus, there are only differences in the rate and timing of heat transfer between the upper mound and the walls due to heat accumulation, but other differences are minimal.

The difference in expansion rates due to the heat transfer from solar radiation between the soil and the walls was interpreted in relation to the movement characteristics observed in the study subject. The soil inside the mound, being located outside the walls, is directly affected by solar radiation energy. As a result, in summer, the thermal expansion of the materials inside the mound occurs first, pushing the inner members towards the interior of the chamber due to earth pressure. This process increases the distance between members. Conversely, in winter, the soil contracts and returns to its original position, reducing the distance between components. The tomb walls exhibit this physical process repeatedly over time, showing patterns opposite to those of typical elastic materials (Fig. 10A), which we interpret as a reasoned assumption based on long-term observed behavior and the physical context of the tomb environment.

A Schematic diagram of the internal materials of the burial mound and the installation status of the displacement meter. B Heat transfer inside the tomb during summer and increased separation distance caused by the expansion of internal materials. C Heat transfer inside the tomb during winter and decreased separation distance caused by the contraction of internal materials. D Rusty and damaged steel support. E, F Additional steel support installation and completed installation status. This figure was created by the authors using original data and Adobe Illustrator CS6. No third-party copyrighted materials were used.

Continuous sagging occurred in the lintel stone of Tomb No. 5, as clearly confirmed by the sagging displacement sensor. Although three vertical supports are installed in the lintel, one of the iron support is rusted and deformed because of corrosion (Fig. 10B). Consequently, it is presumed that it does not provide sufficient support. To restore the supporting power and address the structural issue, additional stainless steel support was installed in November 2023 (Fig. 10C, D). To quantitatively assess the resolution of the structural issue of the lintel stone following the installation of the supports (Fig. 10E, F), continuous monitoring is necessary to determine whether structural stability has improved.

In summary, the findings of this study indicate that despite efforts to improve airtightness through the installation of airtight windows, the conservation environment of Tomb No. 5 showed limited improvement. Temperature fluctuations persisted, and environmental instability remained a challenge due to the tomb’s structural characteristics, particularly its short burial mound height and simple internal layout, which make it highly susceptible to external influences.

While the airtight windows helped reduce air infiltration and mitigate wind effects, they had minimal impact on internal conditions affected by rainfall and soil moisture content. The waterproof layer, originally installed to protect the tomb, has deteriorated over time, leading to leaks and localized instability. This highlights the necessity of conservation treatment and reinforcement of the waterproofing layer to prevent further degradation.

Human entry was identified as a contributing factor to micro-movements within the tomb. Although these movements were minor, their cumulative effect over time could pose a structural risk, necessitating controlled access. Additionally, seasonal displacement patterns were observed, influenced by differences in thermal transfer timing between the burial mound materials and the tomb walls.

A key concern is the continuous subsidence of the lintel stone, independent of external environmental factors, indicating structural instability. To address this issue, additional supports were installed in 2023, but their effectiveness requires ongoing monitoring. Given these findings, long-term conservation efforts must focus on continuous monitoring of environmental conditions and structural movements. The data collected will be crucial in formulating evidence-based conservation strategies to ensure the stability of Tomb No. 5 over time.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are part of an ongoing research project and are not yet publicly available. However, they may be shared by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jung, S. K. A study on the Songsan-ri tombs, Gongju based on the data during the Japanese occupation of Korea. J. Cent. Inst. Cult. Herit. 10, 249–292 (2012).

Suh, M. C. & Park, E. J. Characteristics of subsurface movement and safety of the Songsanri tomb site of the Baekje dynasty using tiltmeter system. J. Eng. Geol. 7, 191–205 (1997).

Yoon, Y. H. Sa-shin-do mural painting of No. 6 tomb in Kongju Songsanri. J. Korean Hist. Stud. 33, 479–508 (2008).

Kim, S. H., Lee, C. H. & Jo, Y. H. Behavioral characteristics and structural stability of the walls in the ancient Korean royal tombs from the sixth century Baekje kingdom. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-020-8819-6. (2020).

Choi, I. K., Yang, H. R. & Lee, C. H. Consideration of procurement system and material homogeneity for lime and clay using the tombs within the King Muryeong and the Royal Tombs in Gongju, Korea. Econ. Environ. Geol. 55, 447–463 (2022).

Choi, I. K., Yang, H. R. & Lee, C. H. A study on digital documentation of precise monitoring for microscale displacements within the Tomb of King Muryeong and the Royal Tombs in Gongju, Korea. J. Conserv. Sci. 37, 626–637 (2021).

Choi, I. K., Yang, H. R. & Lee, C. H. Stability interpretation for the Tomb of King Muryeong and the Royal Tombs in Baekje Kingdom of Ancient Korea using 3D deviation analysis and microscale behavior measurement. RILEM Bookseries 46, 195–202 (2024).

Suh, M. C. et al. In-situ status and conservational strategy of the Muryong royal tomb, the Songsanri tomb No. 5 and the Songsanri tomb No. 6 of Baekje dynasty. J. Nat. Sci. Kongju Natl. Univ. 7, 147–161 (1998).

Suh, M. C. Geotechnical consideration on the conservation of the Muryong royal tomb. J. Conserv. Sci. 8, 40–50 (1999).

Binda, L., Saisi, A. & Tiraboschi, C. Investigation procedures for the diagnosis of historic masonries. Constr. Build. Mater. 14, 199–233 (2000).

Lorenzoni, F. et al. Uncertainty quantification in structural health monitoring: applications on cultural heritage buildings. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 66, 268–281 (2016).

Saisi, A., Gentile, C. & Ruccolo, A. Pre-diagnostic prompt investigation and static monitoring of a historic bell-tower. Constr. Build. Mater. 122, 833–844 (2016).

Verstrynge, E. et al. Crack monitoring in historical masonry with distributed strain and acoustic emission sensing techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 162, 898–907 (2018).

Addabbo, T. et al. A city-scale IoT architecture for monumental structures monitoring. Measurement 131, 349–357 (2019).

Xiong, J. et al. Probing the historic thermal and humid environment in a 2000-year-old ancient underground tomb and enlightenment for cultural heritage protection and preventive conservation. Energy Build. 251, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111388 (2021).

Martin-Pozas, T. et al. Microclimate airborne particles and microbiological monitoring protocol for conservation of rock-art caves: the case of the world-heritage site La Garma cave (Spain). J. Environ. Manage. 351, 119762 (2024).

Bourges, F. et al. Conservation of prehistoric caves and stability of their inner climate: lessons from Chauvet and other French caves. Sci. Total Environ. 493, 79–91 (2014).

Gentile, C., Guidobaldi, M. & Saisi, A. One-year dynamic monitoring of a historic tower: damage detection under changing environment. Meccanica 51, 2873–2889 (2016).

Basto, C., Pelà, L. & Chacón, R. Open-source digital technologies for low-cost monitoring of historical constructions. J. Cult. Herit. 25, 31–40 (2017).

Saisi, A., Gentile, C. & Ruccolo, A. Static and dynamic monitoring of a cultural heritage bell-tower in Monza, Italy. Procedia Eng. 199, 3356–3361 (2017).

Mesquita, E. et al. Long-term monitoring of a damaged historic structure using a wireless sensor network. Eng. Struct. 161, 108–117 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Optimization and assessment of the protective shed of the eastern Wu Tomb. Energies 13, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13071652 (2020).

Burland, J. B. & Hancock, R. J. R. Underground car park at the House of Commons, London: geotechnical aspects. Struct. Eng. 55, 87–100 (1977).

Burland, J. B. & Viggiani, C. Osservazioni sul comportamento della Torre di Pisa. Riv. Ital. Geotecnica. 28, 179–200 (1994).

Burland, J. B., Jamiolkowski, M. & Viggiani, C. Leaning Tower of Pisa: behaviour after stabilization operations. Int. J. Geoeng. Case Hist. 1, 156–169 (2009).

Standing, J. R. & Burland, J. B. Unexpected tunnelling volume losses in the Westminster area, London. Geotechnique 56, 11–26 (2006).

Salmon, F. et al. Heat transfer in rock masses: application to the Lascaux Cave (France). Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 207, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2023.124029 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Effects of emergency preservation measures following excavation of mural paintings in Takamatsuzuka Tumulus. J. Build. Phys. 36, 117–139 (2012).

Lee, M. Y., Kim, D. W. & Chung, Y. J. Conservation environmental assessment and microbial distribution of the Songsan-ri ancient tombs, Gongju, Korea. J. Conserv. Sci. 30, 169–179 (2014).

Kim, S. H. & Lee, C. H. Interpretation on internal microclimatic characteristics and thermal environment stability of the royal tombs at Songsanri in Gongju, Korea. J. Conserv. Sci. 35, 99–115 (2019).

Alaggio, R. et al. Two-years static and dynamic monitoring of the Santa Maria di Collemaggio basilica. Constr. Build. Mater. 268, 121069 (2021).

Rossi, M. & Bournas, D. Structural health monitoring and management of cultural heritage structures: a state-of-the-art review. Appl. Sci. 13, 6450 (2023).

Mitro, N., Krommyda, M. & Amditis, A. Smart Tags: IoT sensors for monitoring the micro-climate of cultural heritage monuments. Appl. Sci. 12, 2315 (2022).

Scuro, C. et al. Internet of Things (IoT) for masonry structural health monitoring (SHM): overview and examples of innovative systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 290, 123092 (2021).

Ceravolo, R. et al. Statistical correlation between environmental time series and data from long-term monitoring of buildings. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 152, 107460 (2021).

Galiano-Garrigós, A. et al. The influence of visitors on heritage conservation: the case of the Church of San Juan del Hospital, Valencia, Spain. Appl. Sci. 14, 2065 (2024).

Roje-Bonacci, T., Miščević, P. & Salvezani, D. Non-destructive monitoring methods as indicators of damage cause on Cathedral of St. Lawrence in Trogir, Croatia. J. Cult. Herit. 15, 424–431 (2014).

Park, J. M. et al. A study on thermal properties of rocks from Gyeonggi-do, Gangwon-do, Chungchung-do, Korea. Econ. Environ. Geol. 40, 761–769 (2007).

Song, S. Y. & Koo, B. K. The state of the art and architectural environmental property evaluation of earth construction material. J. Korean Sol. Energy Soc. 26, 83–91 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the research grant of the Kongju National University in 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the planning, design of this article, performed the data acquisition and data analysis, and I.K.C. wrote the manuscript and C.H.L. revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, I.K., Lee, C.H. Microscale movements of an ancient Korean Royal Tomb in Gongju based on environmental changes. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 276 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01866-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01866-w