Abstract

This study addresses growing environmental and health concerns in conservation-restoration by exploring a sustainable method for varnish removal. It investigates the use of nebulized Agar hydrocolloid to formulate surfactant-free oil-in-water emulsions, even with green solvents like dibasic ester (DBE), which are difficult to mix with water. Agar gel loaded with DBE was nebulized to produce rigid, surfactant-free agar spray emulsions (ASE) for varnish removal. The study evaluated jet properties, emulsion stability, varnish removal efficiency, and possible adverse effects, comparing the nebulized method with traditional high-speed mixing techniques. Results showed nebulization affected droplet size distribution and improved emulsion stability. The green spray emulsion effectively removed dammar varnish from an oil painting without visible degradation, as shown by microscopic observations, SEM-EDS, and FTIR analyses. This biodegradable, non-toxic, surfactant-free emulsion offers a cost-effective, eco-friendly, and promising alternative for modern conservation practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing the sustainability of conservation treatments while minimizing toxicity is a key challenge in developing greener restoration products. Recent efforts have been focused on replacing toxic organic solvents, commonly used for varnish and overpaint removal, with more environmentally friendly alternatives. Over the past decade, significant efforts have been made to replace organic solvents with aqueous systems whenever possible, by tailoring water chemistry, specifically ionic strength and conductivity, to optimize cleaning performance. When water solution is insufficient, emulsions combining water and oil phases (O/W) and micro emulsion have been explored1,2. These emulsions are more ecological and efficient systems made up of a high percentage of water (75–99%) and a reduced organic content (>0.5–15%). Today, thanks to green chemistry, the interest has been addressed to new green solvents, as alternative to common solvents3,4,5. However, the selection of the most suitable solvent depends on its chemical properties and safety, ensuring both effectiveness and protection of the artwork.

The formation of an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion requires a stabilizing component, such as a low molecular weight surfactant or solid particles, to effectively blend the aqueous and hydrophobic phases6,7. To ensure emulsion and microemulsion stability, surfactant concentrations typically range from 5–10% (w/w), but can exceed 25%, and in some formulations, even surpass 50%. However, formulations containing more than 10% surfactant often necessitate prolonged and complex rinsing steps, increasing the risk of non-volatile residues remaining on the surface of treated artifacts8,9,10.

However, O/W emulsion does not fully address the main issue with solvent use in conservation. The invasiveness of solvents, their retention in substrates, and potential interaction with underlying materials are only some of the potential issues related to the use of organic solvents for the removal of aged varnish layers from painted surfaces. Additionally, many green solvents have low evaporation rates, low flammability, and require a specific application through a 3D matrix, in order to support the gradual release of the liquid phase to the painting.

The use of gelled systems, recently introduced in conservation practice, rapresents one of the most successful strategies for conservation treatment, offering a reliable approach for both surface cleaning and varnish removal, aimed at achieving highly effective and non-invasive results6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

Biopolymers, composed of long chains of carbon atoms, hydrophobic, with hydrophilic functional groups (alcoholic, ketone or carboxylic) are in fact amphipathic molecules, with emulsifying and dispersing properties. By replacing low-molecular-weight surfactants with biopolymers, i.e., agar gel network, it is possible to create polymeric emulsions without any surfactants addition. Additionally, due to their larger molecular size, biopolymers have significantly lower sub-surface diffusion capacity compared to low-molecular-weight surfactants21. Biopolymers offer the advantage of forming a 3D network through inter-molecular interactions between polymer chains, such as hydrophobic, electrostatic, van der Waals, or hydrogen bonds in physical gels, or covalent bonds in chemical gels22. Physical gels typically have reversible, weak bonds, though some hydrogels can form stronger, more stable bonds, such as lamellar microcrystals, double or triple helices. Under certain conditions, these strong physical bonds can be nearly permanent, making some physical hydrogels comparable to chemical gels23,24,25.

At the start of the new millennium, the conservation community recognized the value of Agar, thermo-reversible agarose-based hydrogels, as one of the safest methods for treating water-sensitive painted and unpainted surfaces22,26,27.

Agar has two different constituents: agarose and agaropectin. Agarose is a neutral linear polysaccharide composed of three linked β-D-galactose and four linked 3,6-anhydro-α-L-galactose. Agaropectin is an acid polysaccharide containing sulfate groups, pyruvic acid, and D-glucuronic acid conjugated to agarobiose.

Agarose gel networks consist of double helices formed by left-handed threefold helices, stabilized by water molecules inside the cavity. Exterior hydroxyl groups promote the aggregation of up to 10⁴ helices into suprafibers25. The macro-reticulate structure can retain large amounts of both bound and free water molecules28. The key advantage of agar gels in rigid emulsions is their ability to localize solvent release at the gel-substrate interface, minimizing the release of non-volatile components, promoting soiling capture within the gel. Their rigid structure reduces the risk of releasing unwanted residues, requiring minimal rinsing, and offers low cost, environmental benefits, and versatility in application.

The use of the hydrogel loaded with solvent has been widely adopted by conservators over the last decade29,30,31. While it is often assumed that dilution with water reduces solvent efficacy, by analogy with the behaviour of acids, evidence suggests otherwise. Cremonesi notes that the addition of water to polar (water-miscible) solvents can actually enhance their efficacy, particularly on the ionization of organic substances such as proteins, animal glues, and salts, which are often intrinsic components of organic artifacts2.

Moreover, recent studies have shown that polar organic solvents with high diffusion coefficients, such as acetone and ethanol, when mixed with water, can play an important role in the crystallization process of zinc soaps by facilitating the transport of relatively high concentrations of water deep into oil paint layers32.

When working on organic artworks, the agar-water system should be combined with water-immiscible solvents to ensure better control over solvent action. However, achieving a stable, monodisperse o/w emulsion in agar without surfactants represents a challenge. During gel preparation, creaming and coalescence can disrupt solvent droplet distribution, compromising emulsion stability before the gel solidifies. Recently, Agar spray has been proposed as an innovative cleaning method in which agar, in its sol state, has been atomized using a heated paint applicator. This process enables the rapid application of a homogeneous, ultra-fine layer over large surfaces. The technique, originally developed by Giordano has been thoroughly characterized27,33,34,35

Thanks to its unique properties, agar spray is a promising candidate for this pioneering study, which explores its potential to create a surfactant-free, rigid oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion, even with solvents that are typically difficult to mix with water.

The principal aim of this research was to determine whether the rapid dispersion achieved through spraying, combined with the immediate formation of gel microparticles in the air, can stabilize the emulsion throughout the treatment period, without the micellar aggregation commonly seen in emulsions containing surfactants.

To ensure both the safety and effectiveness of applying the emulsion onto organic surfaces via spray, it was crucial to select a solvent that met specific requirements. In particular, the solvent needs to be immiscible with water, possess a high boiling point and flash point, and not promote the release of volatile organic compounds (VOC-free). These characteristics are essential for minimizing flammability risks and ensuring safe handling during application.

The surfactant-free microemulsion evaluated was based on a mixture of agar, water and Di-Basic Esters (DBE), solvent recently introduced to the field of art conservation as a potential green option for natural resin varnish removal36.

DBE is the acronym for Di-Basic Esters, a family of solvents obtained from the methylation of acids produced by fruit fermentation. It is a mixture of 1,4-dimethylsuccinate, 1,5-dimethylglutarate, 1,6 Dimethyladipate, it is classified VOC-free, completely biodegradable and is obtained at 55% from renewable sources, immiscible with water, with a low boiling point and compatible with the pH of conservation materials.

From a safety point of view, it is an exceptional not irritable solvent. It is not flammable and there are no risk symbols on its label. Moreover, as an ester, DBE is inherently difficult to gel, making it an ideal candidate for this research. Table 1 summarizes the main properties of DBE in comparison with other solvents traditionally employed for natural varnish removal, including safety profiles and solubility characteristics.

In this study, the green rigid spray emulsion (ASE-DBE) was tested on a surviving section of real oil paint characterized by a superficial layer of Dammar varnish.

Varnish removal was evaluated by assigning scores based on predefined criteria considering the results of the removal tests, a practice widely adopted in the profession and recently enriched to evaluate and compare varnish removal methods15,37,38. This evaluation method is easy to apply and can be visualized using radar charts for clearer result interpretation.

Additionally, this study evaluated the rheological properties, morphology, and long-term stability of the agar spray emulsions (ASE) containing the oil phase. The impact force and adhesion strength of the spray gel were evaluated and compared with the force required to make a preformed gel adhere to the surface, as well as the adhesive force exerted by the rigid gel applied on the surface through brush in a semi-fluid form. Another important aspect was the evaluation of potential adverse effects of the spray procedure compared to the traditional application of the gel, i.e., the possible interaction with pigments contained in the painting layer as well as the probable release of gel residues.

Methods

Materials

The agar used in this study is AgarArt®, supplied by C.T.S. (M.W.: 100,000–150,000 g/mol). It is a fine, ivory-coloured powder derived from algae of the Rhodophyceae family, specifically the Gelidium and Gracilaria species. According to the product datasheet, AgarArt® in solution has a gelation temperature between 38–42 °C and a sol transition temperature between 85–90 °C. Citric acid and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Di-Basic Esters (EC number. 906-170-0) were provided by C.T.S.

Surviving seventeenth-century painting section for varnish removal tests

Varnish removal tests were performed on a surviving section from a seventeenth-century Italian oil on canvas, a heavily damaged painting donated by a private collector for research purposes, measuring approximately 30 × 35 cm. The painting was unlined, with a coarse, simple tabby weave canvas support and red pigmented ground layer. The painted layers were executed with oil technique, with certain passages having fairly thick impasto. A layer of heavily yellowed varnish covered the painted layers. This varnish was present in multiple passages. Layers stratigraphy and chemical composition were documented through cross-section analysis and FTIR spectroscopy in ATR mode. The paint technique (the presence of original oil-based painted layers, and a surface bulk dammar-based varnish) was revealed through cross-section analyses and FTIR spectroscopy analyses in ATR mode (available online in supplementary file). For the experimental, a surviving section of a historical painting was chosen over mock-up due to the availability of a suitable test painting, being difficult preparing mock-up that are truly representative of aged oil paintings.

Preparation of agar spray emulsions surfactant free for the evaluation of their microscopic, morphological and functional properties

The physical, microscopic, rheological characterization and the evaluation of functional properties of Agar-based emulsions (ASE-DBE) were performed by comparing two different methods of emulsion dispersion:

-

i.

a traditional high-shear mixing approach; ii) a spray nebulization method.

For this purpose, AgarArt® sol was prepared at 3% (w/v) concentration by dissolving the powder in deionized water, followed by microwave heating until boiling in a covered beaker to reduce evaporation. After complete gelation, the agar was re-melted to enhance network homogeneity and water retention capacity.

Before cooling, the hot sol was loaded with 10% DBE (≥99% purity) and then dispersed by two routes:

-

1.

In the first method, the DBE was rapidly emulsified using a mechanical whisk (high-shear mixing). A portion of the resulting surfactant-free emulsion was cast into Petri Dishes to form rigid gels 2 mm thick.

-

2.

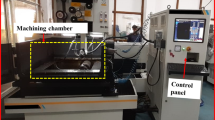

In the second method, the same DBE-enriched agar sol was transferred into the reservoir of a WAGNER W 450 spray gun and atomized directly onto Petri Dishes (Fig. 1) to form spray rigid gels 2 mm thick. This device, equipped with the Wood & Metal Extra Standard nozzle and HVLP (High Volume Low Pressure) technology, ensured fine and uniform droplet formation while maintaining the sol’s fluidity through a heated airflow (45 °C)39.

To ensure consistency and minimize experimental variability, all tests were conducted using 1000 mL batches of AgarArt® sol, ensuring that each sample originated from the same preparation. The WAGNER W 450 spray gun, equipped with the Wood & Metal Extra Standard nozzle optimized for solvent-based formulations, was employed consistently throughout the entire experimental campaign to ensure methodological uniformity.

Although the DBE used (≥99% pure) is not classified as hazardous under GHS/CLP regulations and does not require specific hazard labelling, standard laboratory safety procedures were strictly followed. Personal protective equipment (PPE), including nitrile gloves, safety goggles, and laboratory coats, was worn throughout the experiments. All procedures were carried out in a well-ventilated environment to minimize potential inhalation exposure, especially during the spraying phase. Direct eye contact and prolonged skin exposure were avoided, and appropriate hygiene measures were implemented after handling. These safety measures were maintained consistently across all phases of the research.

Preparation, application, removal and clearance of Agar Spray emulsions (ASE) on the oil-based painting

The treatments on the oil-based painting were performed by Agar gels at 3% (w/v) concentration prepared as follows: agar powder was dissolved in a buffered aqueous solution at pH 6. This pH-matching strategy was employed to maintain constant pH values and work in non-ionizing conditions, in order to avoid unwanted chemical interactions with the substrate during varnish removal process1,2.

The hot agar sol was enriched with three different concentrations (5, 10 and 15%) of di-basic ester (DBE) solvent and applied on the surface via two procedures:

-

1.

“Direct spray application”, where the emulsion was atomized directly onto the painted surface.

-

2.

“Indirect transfer”, where the emulsion was first sprayed onto a plastic sheet and then left onto the surface, mimicking traditional rigid gel application for 2 minutes.

The spray was delivered using the same WAGNER W450 previously described, from a fixed distance of 40 cm, applying the gel for 2 minutes on a defined test area (3 cm in diameter). The agar sol temperature prior to spraying was dependent on the room’s and surviving section surfaces’ temperature, and relative humidity following recommendations by Giordano40.

All phases of the treatment, preparation, application, removal, and final clearance, are summarized in Table 2. The clearance was always performed using pre-formed rigid gels to avoid any potential bias introduced by a second sprayed layer, which could interfere with the interpretation of varnish removal effectiveness. Based on these results, the most effective formulation, was subsequently applied to a larger area measuring 8 × 10 cm, in order to evaluate its performance under conditions more representative of a real conservation treatment. The exclusion of a control group using pure DBE or conventional surfactant-based emulsions in this study was attributable to the slow evaporation rate of pure DBE, due to its high boiling point (196–225 °C) and very low vapour pressure (0.06 Torr at 20 °C), which makes it unsuitable for free-form application. Moreover, the aim of this pilot study was to explore an alternative to traditional varnish removal systems, focusing on minimizing the need for rinsing and mechanical intervention.

Optical microscopy

The morphological characteristics of the Agar Spray Emulsion were studied with an optical microscope (NeXcope NE710, TiEsseLab), equipped with a digital camera. The images were then analyzed by microscope software, Capture V2.4, in order to obtain the oil droplet size distribution.

Digital microscopy

Varnish removal from mock-up samples, along with the materials employed in the process, including swabs, emulsions, gels, and cloths, was documented using high-resolution digital microscopy. Imaging was performed with a Dino-Lite digital microscope (30× magnification), featuring a high-resolution camera and a precision digitizing adapter. Image acquisition and analysis were conducted using ImageJ, a Java-based software widely used for scientific image processing.

Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

Agar spray emulsions (ASE) used for varnish removal from a surviving section of a seventeenth-century Italian oil painting on canvas (originally coated with dammar varnish) were analysed using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iZ10 spectrometer equipped with a diamond ATR crystal and a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector. Spectra were collected over the 3600–600 cm⁻¹ range at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, averaging 32 scans per sample. Five replicate measurements were performed. Data processing was carried out with Omnic 9 software, including manual baseline correction and removal of the CO₂ band (2400–2350 cm⁻¹). ATR-FTIR analyses were first performed on agar spray emulsion before and after its application on a seventeenth-century oil painting on canvas, in order to evaluate the efficacy of the treatment in terms of varnish removal. Moreover, the spectra of the used emulsions were compared with reference spectra from an unvarnished area of the seventeenth-century Italian oil painting, varnish dammar, and agar powder (AgarArt®). This comparison was aimed at detecting any possible residues or interactions between the ASE and the original pictorial layer.

Scanning Electron Microscopy analyses (SEM-EDS)

Scanning electron microscopy observations were performed on the following samples: (a) on painting sample before and after the varnish removal with agar spray emulsion; (b) on agar spray gel before and after its application on the painting. These comparisons were performed in order to evaluate the efficacy in the varnish removal. Moreover, SEM-EDS analyses were also carried out with the aim to evaluate any possible interaction with pigments.

The analyses were performed by FEI Quanta 600 instrument, accelerate voltage 30 KV, work distance 10 mm, both in the secondary electrons mode (SE) and backscattered mode (BSE).

Rheological measurements

Rheological tests were performed by means of a Discovery HR-1 Rheometer, TA Instruments equipped with a solvent trap, used to avoid the solvent evaporation during all the tests. The temperature was set at 25 ± 0.2 °C. All the experiments were carried out with a parallel-plate geometry (40 mm diameter); the gap was set at 2 mm. Following M. Bertasa et al. protocol, the agar samples were prepared as cylinders of 2 mm and analyzed after one hour from the preparation21. Subsequently, the viscoelastic features were investigated by frequency sweep tests with an angular frequency and a constant strain amplitude of 10 rad s-1 and 1%, respectively.

Evaluation of pressure on the painting surface

The impact force of the methods was measured using an experimental setup comprising a Bose Biodynamic 3100 system with an anchored sheet connected to a load cell (Fig. 2). Data acquisition was carried out using Bose WinTest 7 software. The measuring device was positioned at a fixed distance of 40 cm and aligned with the sprayer nozzle. The selected nozzle configuration provided the highest spray impact, with a maximum flow rate of 230 ml/min. A mock-up with characteristics analogous to the original painting fragment was prepared following the methodology described by Husby et al.15.

Tests were conducted on a circular reference surface with an area of 1.26 × 10⁻³ m² (diameter = 4 cm). For comparison, the force applied by an operator’s thumb to spread a pre-formed 2 mm thick agar film on the same reference surface was also recorded. Although fingertip pressure is not a standardized application method, it was selected based on practical observations in conservation workshops, where small agar gel patches are sometimes gently adjusted or repositioned manually. This gesture was chosen to represent a minimal mechanical intervention, serving as a low-threshold reference for comparison with the spray impact. The aim was not to replicate a formal application procedure, but to capture a common, intuitive action—particularly relevant in borderline cases where mechanical stress on sensitive surfaces can be critical. At least three measurements were taken for each condition.

Adhesive strength

The test was based on the measure of the force versus time during the manual detachment of a 2 mm thick agar gel layer from a reference surface. An experimental setup was used, consisting of Bose Biodynamic 3100 instrumentation and Bose WinTest 7 software for data acquisition, along with a WAGNER W450 Detail sprayer, which has a constant pressure and a maximum flow rate of 230 ml/min. The procedure began by anchoring the reference surface to a load cell, then positioning the measuring device at a fixed distance (40 cm) and aligning it with the sprayer nozzle. Agar gel was either sprayed or manually applied by brush to the reference surface, forming a layer of approximately 2 mm thickness. The reference surfaces were prepared either 10 ×10 cm squared canvas and rounded (diameter of 5 cm) oil painted canvases, with similar characteristics to 17th century oil painting. The force required to strip the polymerized agar gel was then measured. At least three measurements were performed for each sample.

Varnish removal: evaluation of method parameters and rating criteria

Five evaluation parameters were chosen and defined to help assess and compare the selected application and concentration of ASE for varnish removal. Each parameter was rated on a scale from 1–5 (worst–best) where larger stars represent more promising systems (Table 3). Results from the five evaluation parameters (Table 3) were represented in star diagrams made in Excel using the ‘radar chart’ function. Digital microscopy was performed on samples and on the gel prior and after treatment using a Dino-Lite AM7013MT microscope, 5 megapixels (2592 × 1944), set at 30× magnification, using ring light illumination. Images were processed using Dino Capture software. The effectiveness of a varnish removal method was evaluated by measuring the time spent and the level of mechanical action applied to achieve an optimal and uniform treatment (assessed visually). Exposure time was recorded in minutes and rated from slowest to fastest, while mechanical action was categorized and rated from ‘none’ to significant.

Results

Morphology of Agar gel and stability over time

The Agar-spray network containing the oil phase was observed by an optical microscope. The system clearly showed the presence of the oil droplets. As shown in Fig. 3, a decrease in emulsion stability was observed as time increases. In fact, the initial stability and the homogeneous dispersion of oil droplets within Agar medium observed from t = 0 (time of emulsion preparation) to t = 15 min, was lost at t = 30 min. At this time, it was observed a slight separation between the two phases, which became more evident, with the aggregation of the oil phase at t = 2 hours. Nevertheless, it is relevant to record a great stability of the Agar-spray system until t = 15 minutes, which is particularly noteworthy considering that the application time during treatment procedures does not exceed 2 minutes34. Regarding the oil droplet size distribution, a radius ranging between 2 and 10 μm can be observed (Fig. 4). The majority of droplets ranged between 2 and 5 μm, but we can find both smaller and bigger ones, even if at lower frequencies. This data gives us information about a complex system presenting a variety of droplets dimensions.

The emulsion into the common Agar gel after the same times from the preparation (t = 0, t = 15 min, t = 30 min t = 2 hours) was also observed through the optical microscope (Fig. 5). The Fig. 5 showed how in the common Agar gel there was a more rapid aggregation of the oil phase, with larger droplets size if compared to the Agar-spray system.

Frequency sweep experiments

Rheological experiments of both G’ and G” were investigated to evaluate the viscoelastic moduli of the Agar systems, both sprayed and not, containing the oil phase (DBE). In particular, it has been studied the rheological moduli time-dependence of the Agar spray immediately after nebulization and Agar gels after 40 minutes from the preparation. Frequency-sweep test was performed at constant angular frequency and amplitude. As shown in Fig. 6a, the three following regions are detected for the Agar rigid gel: (1) at low step time the gel has a liquid-like behaviour, with G’ < G”; (2) it is registered a crossover point (t = 768 s) between the rheological moduli which marks the transition from liquid-like to solid-like behaviour; (3) the Agar network formation occurs (G’ > G”), with a strong gel behaviour confirmed by the almost time-independency of both moduli. While, if we observe Fig. 6b, Agar-spray starts acting as a gel from t = 0, with G’ > G”, indicating that the system possesses clear gel characteristics for the whole measurement. These results are in agreement with the fact that the atomized agar sol–gel transition process takes place in the air at high-pressure systems and by rapid air-cooling, already impacting the surface in a gel form.

Evaluation of pressure on the painting surface

The pressure induced by agar spray jet on the painting surface was evaluated and compared with a manual pressure exerted by a human operator applying a pre-formed 2 mm-thick agar gel with their thumb over the same surface. The impact of a multidrop spray on a painting surface was inherently more complex than that of a single droplet, due to the interactions among droplets of varying sizes and velocities, and the dynamic hydrodynamic conditions that arise during application. The principal aim was to verify the entity of spray impact on the painting.

To assess the distribution and magnitude of the spray’s impact force, preliminary tests were conducted using the WAGNER W450 sprayer positioned at a fixed distance of 40 cm from the target surface. At this distance, the spray pattern produced an impacted area of approximately 100 cm², with mass deposition concentrated on a central circular area of about 1.3 × 10⁻³ m². Accordingly, for consistency, force measurements were standardized on a circular reference surface of 1.26 × 10⁻³ m² (diameter: 4 cm). In both spray and manual applications, at least three repetitions were performed. The average values of the force and the corresponding standard deviation were considered. The final pressure was calculated considering the force measured over the area of the test.

The calculated pressure for the spray application, based on an average force of 0.26 ± 0.03 N measured over the 1.26 × 10⁻³ m² area, was approximately 206 Pa. In contrast, the average force measured for manual gel application was higher (2.39 ± 0.63 N) and corresponded to a pressure of about 3983 Pa calculated on an average thumb contact area of 6 * 10⁻⁴ m². These results confirm that the pressure generated by the spray is significantly lower, more consistent and more homogeneous than that exerted during manual spreading.

Adhesive strength

The adhesive strength induced by the spray agar gel, as well as by agar applied through a brush on the reference surface, was evaluated. Representative force versus time data were recorded. The average maximum strength detected for the sprayed agar gel was 0.15 ± 0.06 N. For the agar gel applied by brush, the average maximum strength was 0.50 ± 0.16 N.

The results suggested that the detachment of the agar gel applied by spraying was softer than that of the brushed gel, potentially reducing the risk of damaging the painted surface. As expected, the force measured in the second condition revealed higher variability due to the imprecision of manual application of agar by brush. Although some variability in the data was observed due to manual handling, the overall trend was clear: spraying the agar gel led to gentler detachment. Further refinement of the manual process could help reduce data variability and improve consistency. (The entire dataset used in this study is provided in the supplementary file available online).

ASE applications for varnish removal test: direct application

The Agar Spray Emulsions (ASE) tested in this study were prepared as described in Table 2 using different concentrations (5%, 10%, and 15%) of DBE as the dispersed phase. The emulsions were applied directly via nebulization onto the surface of a surviving fragment of a seventeenth-century Italian oil painting coated with natural dammar varnish.

Microscopic examination of the treated surfaces revealed clear differences in treatment performance depending on the DBE concentration. ASE1 (5% DBE) was easy to remove after application but demonstrated limited varnish removal effectiveness. It solubilized and absorbed only the uppermost layer of varnish, leaving a tacky residue on the surface. This sticky layer complicated further removal and required excessive mechanical action with cotton swabs, which in turn led to pigment pickup.

In contrast, ASE3 (15% DBE) demonstrated an efficient varnish removal. However, its higher solvent content gave the gel a whitish appearance that reduced visibility during application (Fig. 7). After removal, the gel appeared yellowed, indicating extensive varnish absorption.

ASE2 (10% DBE) offered an optimal balance between varnish removal efficiency and application control. It delivered varnish removal comparable to ASE3, while maintaining superior visual clarity during treatment, as indicated by the star diagram (Fig. 8).

As highlighted by the star diagram, ASE2 emerged as the most promising system. This gel was subsequently applied to a larger area (8 × 10 cm) to assess its performance under conditions more representative of a real conservation treatment (Fig. 9). The results confirmed several practical advantages: the gel adhered well even on vertical surfaces, allowed for quick and uniform application, and remained visually clear during the process, enabling close monitoring of the varnish removal action. A detail of the efficacy of the treatment in terms of varnish removal was shown in Fig. 10.

The Fig. 10 showed the effectiveness in the varnish removal by ASE2, confirmed by UV-driven fluorescence.

ASE applications for varnish removal test: Indirect application

A key observation regarding the indirect application method was its tendency to show lower varnish removal efficacy, even when the solvent phase was larger in comparison to the direct spray application. The reduced ability of the gel to absorb the dissolved varnish significantly hampered its performance. This inefficiency forced the operator to apply more mechanical action using a cotton swab during the removal phase. Notably, when ASE2 was applied indirectly for 2 minutes, followed by removal, there was a marked tendency for pigment pickup and the appearance of scratches on the surface. This highlights the disadvantageous nature of the increased mechanical action required in indirect applications as reported in the star diagram (Fig. 11).

In contrast, the best varnish removal result with indirect applications was achieved by applying ASE3 four times, with each application lasting 2 minutes. This multiple application method allowed for a more controlled process, reducing the need for excessive mechanical action while maintaining the efficiency of varnish removal (Fig. 12). However, this approach also made the treatment process more complex and time-consuming, as the prolonged contact time with the emulsion increased the overall duration of the treatment. Despite this, the repeated application of ASE3 significantly improved the absorption of dissolved varnish, minimizing the risk of surface damage.

Spectroscopic evaluation of the effectiveness of the ASE varnish removal treatment

The varnish removal from the painting induced by ASE2 was also evaluated through FTIR and SEM-EDS analyses.

The first comparison was performed between dried agar gel before and after the the varnish removal treatment of the painting. The FTIR spectrum of agar after the varnish removal (Fig. 13) revealed a significant presence of the main peak of oxidized varnish at 1709 cm−1 (peak absent in agar before the varnish removal). This result suggested that gel matrix ASE2 effectively solubilized and captured the varnish. Further information is reported in supplementary.

Results were confirmed by SEM-EDS investigation performed both on painting samples and on the gels. In fact, the uncleaned region of the paint sample showed the typical craquelure of an oxidized varnish (Fig. 14 in SE mode, right image) and appeared mostly dark because of the presence of organic varnish (Fig. 14 in BSE mode, left image). This region is clearly different from the varnish removed one, in which the presence of heavier elements, responsible for higher luminous regions, was predominant and derived from the painting layer (Fig. 14 in BSE mode). Moreover, untreated and varnish-removed areas of the painting, as well as agar gel before and after its application on the varnish layer were also compared (Fig. 15). The results of SEM observations and EDS analyses, shown in Fig. 15, underlined a different morphology between the untreated (a) and varnish-removed region of the painting (b), and, above all a different chemical composition, as indicated by EDS spectra. In fact a consistent presence of lead was revealed in the varnish removed region originating from the white lead pigment in the painting layer (Fig. 15b). Some lead residues could be detected also in the varnish layer, probably deriving from the leaching of this element from painting layer (Fig. 15a). The analyses performed on the agar gels before (Fig. 15c) and after its application on the varnish layer (Fig. 15d) revealed a similar composition mainly made of carbon, oxygen, sodium, sulphur, chlorine and calcium. Only in some cases very rare lead particles were detected in the agar gel after the application, to the same extent as the varnish layer.

Results suggested the effectiveness of ASE2 for the removal of varnish through a delicate treatment respectful of pigments and the painting layer.

A preliminary investigation about the possible gel residues left on the surface after the treatment was performed through microscopic observations and FTIR analyses.

After treatment with ASE2 no polysaccharide residues from the agar-based emulsion were detected by ATR-FTIR analysis on the oil paint surface samples (Supplementary file: Fig. S11). High-resolution digital microscopy confirmed the absence of visible physical residues on the treated surfaces. Nonetheless, it is recognized that FTIR-based techniques have intrinsic limitations in sensitivity, which may hinder the detection of trace levels of cleaning agents. For a more thorough assessment of potential residues, complementary analytical methods with greater surface sensitivity should be considered.

Discussion

This preliminary study highlighted the significant potential of nebulized agar gel for the creation of surfactant-free rigid emulsions with DBE solvent. The system demonstrated a marked impact on solvent encapsulation after gelation, resulting in a rigid gel emulsion with a more uniform and organized structure, characterized by a higher number of smaller solvent droplets. This stable structure promoted varnish removal efficiency, making the system particularly effective in conservation applications.

Notably, results from the Bose Biodynamic testing machine demonstrated that the direct application of the gel at maximum power, followed by its removal, was gentler compared to traditional gel application methods. The pressure exerted by the gel was lower than that typically applied manually by conservators, indicating a more delicate treatment process. This observation reinforces the potential advantages of using nebulized gels for more controlled and less invasive varnish removal treatments. Another important finding of this study was that the performance of the indirect application method was significantly inferior to the direct method. This is likely due to the absence of mechanical impact, which in the direct method facilitates the immediate release of solvent and the rapid reabsorption of the solubilized varnish by the gel. This mechanism, resembling a suction-pad or sponge effect, enhances and accelerates varnish removal through a physical action triggered by compression. Additionally, the star diagram analysis showed that the indirect method was more complex in terms of both preparation and application, partly due to the need for repeated gel dwell times. The best results were achieved with the direct application of ASE2 (agar spray gel emulsion with 10% of DBE). In this case, the varnish was effectively removed after just 2 minutes of application, allowing for good visibility during treatment and significantly reducing the need for mechanical action. However, it is important to emphasize that, despite the low solvent content and high agar retention, further studies are needed to monitor the long-term effects of this treatment. The interaction of “green” solvents with paint surface has not yet been sufficiently investigated, and only limited research on their long-term post-treatment effects have been presented. Key aspects, such as the persistence of the solvent on the surface after application, its potential to induce oxidative phenomena of the painting film, and other long-term chemical interactions, remain poorly studied. It is important to note that while “green” solvents are non-toxic, they may cause allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, especially with repeated use or in poorly ventilated areas. Therefore, precautions should be taken during their application, despite their low toxicity being a key advantage. In conclusion, the combination of nebulized agar gel and “green” solvents represents a promising, sustainable approach to the removal of aged natural varnishes. This method offers greater efficiency, safety, and an environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and adaptable alternative to traditional varnish removal methods. The spray procedure can guarantee grater safety and the preservation of morphological properties of the painted surface, through a rapid varnish removal treatment, with a minor probability of gel residues release. For this reason, the agar spray method could be indicated also for the removal of altered surface layers of large-scale paintings, where working safely in short times represent and advantage and a priority.

However, further research on long-term effects and allergic risks will be essential to ensure its viability as a standard conservation technique.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Wolbers, R. La pulitura di superfici dipinte. Metodi acquosi. Il Prato, (2005).

Cremonesi, P. L’ ambiente acquoso per il trattamento di manufatti artistici. Il prato, Saonara (PD), (2019).

Häckl, K. & Kunz, W. Some aspects of green solvents. Comptes Rendus Chim. 21, 572–580 (2018).

Gueidão, M., Vieira, E., Bordalo R. & Moreira P. Available green conservation methodologies for the cleaning of cultural heritage: an overview. Estudos de Conservação e Restauro 22-44 Páginas. https://doi.org/10.34632/ECR.2020.10679 (2021).

Fife, G., Doutre, M. The Getty Conservation Institute, Institut royal du patrimoine artistique (2022) Greener solvents in art conservation: report from an experts meeting organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and The Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA), December 13–14, 2022. Experts Meeting. Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles.

D’Agostino, G. et al. Pickering Emulsion Gel Based on Funori Biopolymer and Halloysite Nanotubes: A New Sustainable Material for the Cleaning of Artwork Surfaces. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 6, 7679–7690 (2024).

Cavallaro, G. et al. Pickering Emulsion Gels Based on Halloysite Nanotubes and Ionic Biopolymers: Properties and Cleaning Action on Marble Surface. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 3169–3176 (2019).

Angelova, L. V., Ormsby, B. A., Townsend, J. H. & Wolber,s R. Gels in the conservation of art. Archetype Publications, London. (2017)

Byrne, A. Wolbers Cleaning Methods: Introduction. AICCM Bull. 17, 3–11 (1991).

Casini, A., Chelazzi, D. & Baglioni, P. Advanced methodologies for the cleaning of works of art. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 66, 2162–2182 (2023).

Hao, X. et al. Comparisons of the restoring and reinforcement effects of carboxymethyl chitosan-silk fibroin (Bombyx Mori/Antheraea Yamamai/Tussah) on aged historic silk. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.124, 71–79 (2019).

Egil, A. C. et al. Chitosan/calcium nanoparticles as advanced antimicrobial coating for paper documents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.215, 521–530 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Long-term antioxidant and ultraviolet light shielding gelatin films for the preservation of leather artifacts. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.s 291, 138981 (2025).

Bartoletti, A. et al. Correction to: Reviving WHAAM! a comparative evaluation of cleaning systems for the conservation treatment of Roy Lichtenstein’s iconic painting. Herit. Sci. 8, 41 (2020).

Husby, L. M., Andersen, C. K., Pedersen, N. B. & Ormsby, B. Evaluating three water-based systems and one organic solvent for the removal of dammar varnish from artificially aged oil paint samples. Herit. Sci. 11, 244 (2023).

Rosciardi, V., Chelazzi, D. & Baglioni, P. Green” biocomposite Poly (vinyl alcohol)/starch cryogels as new advanced tools for the cleaning of artifacts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 613, 697–708 (2022).

Palla, F. et al. Innovative and Integrated Strategies: Case Studies. In: Palla F., Barresi G. (eds) Biotechnology and Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 85–100. (2017)

Casoli, A. et al. Analytical evaluation, by GC/MS, of gelatine removal from ancient papers induced by wet cleaning: A comparison between immersion treatment and application of rigid Gellan gum gel. Microchem. J. 117, 61–67 (2014).

Isca, C. et al. The use of polyamidoamines for the conservation of iron-gall inked paper. Cellulose 26, 1277–1296 (2019).

Isca, C., Fuster-López, L., Yusá-Marco, D. J. & Casoli, A. An evaluation of changes induced by wet cleaning treatments in the mechanical properties of paper artworks. Cellulose 22, 3047–3062 (2015).

Bertasa, M. et al. Agar gel strength: A correlation study between chemical composition and rheological properties. Eur. Polym. J. 123, 109442 (2020).

Caruso, M. R. et al. A review on biopolymer-based treatments for consolidation and surface protection of cultural heritage materials. J. Mater. Sci. 58, 12954–12975 (2023).

Bonelli, N. et al. Confined Aqueous Media for the Cleaning of Cultural Heritage: Innovative Gels and Amphiphile-Based Nanofluids. In: Dillmann P., Bellot-Gurlet L., Nenner I. (eds) Nanoscience and Cultural Heritage. Atlantis Press, Paris, pp 283–311 (2016).

Allen G. Comprehensive polymer science and supplements. Elsevier, New York (1996).

Guilminot, E. The use of hydrogels in the treatment of metal cultural heritage objects. Gels 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9030191 (2023).

Mecklenburg, M. F., Charola, A. E. & Koestler, R. J. New Insights into the Cleaning of Paintings: Proceedings from the Cleaning 2010 International Conference, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia and Museum Conservation Institute. Smithson. Contributions Mus. Conserv. 3, 1–243 (2013).

Giordano, A. & Cremonesi, P. New methods of applying rigid agar gels: from tiny to large-scale surface areas. Stud. Conserv. 66, 437–448 (2021).

Tuvikene, R. et al. Gel-forming structures and stages of red algal galactans of different sulfation levels. J. Appl Phycol. 20, 527–535 (2008).

Volk, A., Van Den Berg, K. J. Agar – A New Tool for the Surface Cleaning of Water Sensitive Oil Paint? In: Van Den Berg K. J. et al. (eds) Issues in Contemporary Oil Paint. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 389–406 (2014).

Gorel, F. Assessment of agar gel loaded with micro-emulsion for the cleaning of porous surfaces. ceroart. https://doi.org/10.4000/ceroart.1827 (2010).

Scott C. L. The use of agar as a solvent gel in objects conservation. 19 (2012).

Hermans, J., Helwig, K., Woutersen, S. & Keune, K. Traces of water catalyze zinc soap crystallization in solvent-exposed oil paints. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 5701–5709 (2023).

Ormsby, B., Bartoletti, A., Van Den Berg, K. J. & Stavroudis, C. Cleaning and conservation: recent successes and challenges. Herit. Sci. 12, 10 (2024).

Giordano, A., Caruso, M. R., Lazzara, G. New tool for sustainable treatments: agar spray—research and practice. Heritage Science 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00756-9 (2022).

Gel rigidi polisaccaridici per il trattamento deimanufatti artistici. In: Prato, I. L. Edizioni - Narrativa, Storia, Filosofia, Arte. https://ilprato.com/libro/gel-rigidi-polisaccaridici-per-il-trattamento-dei-manufatti-artistici/ Accessed 26 May 2025.

Macchia, A., Rivaroli, L. & Gianfreda, B. The GREEN RESCUE: a ‘green’ experimentation to clean old varnishes on oil paintings. Nat. Prod. Res. 35, 2335–2345 (2021).

Cutajar, J. D. et al. Spectral- and image-based metrics for evaluating cleaning tests on unvarnished painted surfaces. Coatings 14, 1040 (2024).

Bartoletti, A. et al. Facilitating the conservation treatment of Eva Hesse’s Addendum through practice-based research, including a comparative evaluation of novel cleaning systems. Herit. Sci. 8, 35 (2020).

User manual Wagner W 450 WallSprayer (English - 70 pages). https://www.usermanuals.au/wagner/w-450-wallsprayer/manual Accessed 26 May 2025.

Agar spray: New applications of rigid gel for the treatment of large surfaces | 1 International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. https://www.iiconservation.org/news/agar-spray-new-applications-rigid-gel-treatment-large-surfaces Accessed 26 May 2025.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Paolo Cremonesi for invaluable discussions and advice during the study and Maria Grazia Pirozzi and Giovanna Climaco for supporting in photography during experimentation. This work has received funding from the European Union – NextGenerationEU through the Italian Ministry of University and Research under PNRR – M4C2 – ECS0000002 – SAMOTHRACE. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. conceived and designed the research, she planned and carried out the experiments and part of the analyzes, A.G. and C.I. carried out the drafting of the manuscript. G.D. and B.M. performed the measurements, processed the experimental data. GL and CI aided in interpreting the results. A.G., C.I., and G.L. supervise the project. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giordano, A., D’Agostino, G., Megna, B. et al. Evaluation of agar spray for the development of a green surfactant-free rigid emulsions. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01869-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01869-7