Abstract

The accurate recording of high-quality underwater cultural heritage images is crucial for archeological research. However, underwater images frequently suffer from color distortion and reduced clarity, which compromises image quality. Existing underwater image enhancement methods often lead to either over-enhancement or under-enhancement, thereby obscuring artifact details and hindering archeological research. This study proposes a method for enhancing quality and restoring color in underwater cultural heritage images, based on an underwater physical imaging model. First, a different background light estimation algorithm based on brightness segmentation (DBE-BS) is developed to enable adaptive multi-region background light estimation, thereby mitigating the impact of uneven lighting on the image. Next, the depth-saturation fusion transmission (DSFT) map estimation algorithm integrates depth information with the inverse saturation map, improving transmission map accuracy. Finally, the Depth-integrated Color Compensation Model (DICC) is introduced to optimize color correction using image depth data, enhancing the image’s visual quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To protect valuable underwater cultural heritage, the use of digital imaging technology to document underwater artifacts and sites is essential. High-quality image records not only preserve detailed site information but also enable the analysis of material composition, degradation products, and alteration markers of cultural artifacts, thus supporting non-invasive research methods such as 3D visualization. However, due to light attenuation and scattering during underwater propagation, captured images often suffer from severe color distortion and poor visibility, which significantly hinders further analysis and identification of cultural heritage. As a result, numerous scholars have conducted extensive research in color correction and image clarity enhancement, employing various approaches.

Non-physical underwater image enhancement methods typically adjust pixel values to improve degraded images, without considering the underlying principles of underwater image formation. Common techniques include color channel compensation and white balance. Ancuti et al. restored lost colors by subtracting local means from each color channel1, while Berman et al. addressed color distortion by estimating the attenuation ratio between blue-red and blue-green channels2. These methods can recover color but struggle with complex underwater environments, where varying depth and structures may cause over-correction or distortion. Building on the limitations of the previous method, the ERH approach was proposed to improve color, sharpness, and contrast, while reducing brightness discrepancies in overlapping areas3. In addition, other methods enhance contrast using dual-histogram thresholding and multi-scale fusion strategies, followed by sharpening4. While these techniques are effective for global adjustments, they may overlook small details in rich-texture artifacts, limiting the restoration of true characteristics. The ACCE method introduces adaptive color contrast enhancement to suppress high-frequency noise while enhancing low-frequency contrast5. Similarly, many methods also combine multi-technique fusion to improve image quality by integrating multiple enhancements6,7. However, all these methods rely on fixed enhancement approaches, making them less adaptable to diverse underwater environments, where variations in depth or sediment composition can affect color and texture accuracy.

Additionally, Retinex, a widely used non-physical model for underwater image enhancement in recent years, is based on the principles of the human visual system and aims to simulate how the human eye perceives illumination and color. Researchers have conducted numerous studies based on this theory. There is a method that combines the Retinex model with Gradient Domain Guided Image Filtering (GGF) to enhance image structure while reducing noise and other artificial artifacts8. There is also a CCMSR-Net network designed based on Retinex to improve the quality of underwater images9. However, the Retinex method is better suited to relatively uniform image structures and often struggles with the complex textures and fine structures present in underwater cultural heritage sites. This limitation arises because Retinex lacks specificity in local color and brightness enhancement, which can lead to blurring of texture and structural details, thereby weakening the restoration of site details. Additionally, the shadow removal process in Retinex may cause the loss of heritage details, compromising the precise recognition of artifact surface features.

Existing non-physical underwater model image enhancement methods are generally simple and computationally efficient. However, they lack the flexibility to handle complex underwater scenes effectively, often relying on scene simplicity and specific assumptions. This can result in over-enhancement or under-enhancement issues, and these limitations are especially pronounced in processing underwater cultural heritage images. Underwater cultural heritage environments are often complex and variable, with differing levels of water turbidity, uneven lighting, and depth changes—all of which impact image clarity and color accuracy. Non-physical model methods struggle to adapt to subtle variations in the surface structures of heritage sites, leading to a loss of image detail and compromising the accurate identification of artifact morphology and characteristics.

Image enhancement methods based on physical underwater models simulate the propagation and attenuation of light in underwater environments, offering more accurate color restoration and contrast enhancement. These methods leverage an understanding of optical properties like scattering and absorption to address common color distortions and blurring in underwater images. Ge et al. used an adaptive attention-based method to calculate transmission rates for key channels10, while Song et al. employed a new underwater dark channel prior to refine transmission maps11. However, these methods often assume a uniform environment, limiting their effectiveness in the complex and variable lighting conditions of underwater cultural heritage sites. For transmission maps, some methods perform dehazing using dual transmission maps, while others refine transmission maps through grayscale morphological closing and a new light attenuation prior12,13. While these methods improve color restoration, they struggle to fully capture subtle color gradations in heritage images due to their focus on enhancing specific channels. Some methods use depth and illumination maps to improve image restoration, but depth estimation errors and static priors can lead to inaccuracies in complex environments with multiple light sources and uneven depth layers14,15. Adaptive strategies are also used to address light source effects and enhance texture details16,17. However, global contrast adjustments may overlook small-scale variations in texture and detail, particularly in heritage sites. These methods face challenges in underwater cultural heritage environments due to complex depth layers, multi-angle lighting, and interference from sediment and microbial particles. These factors can introduce noise, leading to inaccuracies in depth estimation and diminishing the restoration of fine details.

In recent years, deep learning methods have demonstrated impressive performance in underwater image enhancement, primarily due to their powerful feature learning capabilities. Several of these methods also consider the unique characteristics of underwater imaging. The enhanced Swin-Convs transformer block (RSCTB) strengthens local attention and spatial processing to better handle image degradation caused by uneven medium distribution18. Cong et al. proposed a two-stream interactive enhancement subnetwork (TSIE-subnet), using CNN-based methods to learn physical parameters and enhance images end-to-end19. Peng et al. developed the U-shape Transformer, combining multi-scale feature fusion and global feature modeling to enhance underwater image quality20. The CycleGAN model integrates a physical model to enhance the generalization of traditional GANs in real-world underwater environments21. Gao et al. decomposed the restoration process into global restoration and local compensation, correcting color deviations and improving contrast while preserving details22. Huang et al. applied contrastive semi-supervised learning to enhance unlabeled data, improving restoration accuracy and generalization23. Chen et al. proposed a wavelet and diffusion model (WF-Diff) that enhances detail and visual quality through frequency domain information interaction24. While these deep learning methods excel in color correction and global contrast enhancement, they often struggle to restore complex textures and fine details due to their reliance on specific training data. Their adaptability to the diverse optical characteristics of underwater cultural heritage sites remains limited, posing challenges for archeological research that demands accurate color preservation and stable detail restoration for cultural relics.

Physical model-based methods can more accurately address color cast and contrast issues by simulating the physical processes of underwater light propagation and scattering. However, they are often computationally intensive and highly sensitive to environmental parameters, necessitating precise environmental information for effective image restoration. Deep learning methods leverage their powerful data-driven capabilities to extract effective features in complex and variable environments, significantly enhancing image quality. However, these models require substantial training data, demand high computational resources, and face challenges in generalization and interpretability. This study employs a brightness segmentation-based background light estimation algorithm and a depth-saturation fusion transmission map estimation algorithm to yield more accurate background light values and transmission maps. Furthermore, a color compensation model that incorporates depth information is applied to achieve effective color correction. This method resolves issues related to uneven lighting, color distortion, and blurred details, thereby enhancing the image’s clarity, contrast, and color accuracy. These optimizations result in a more realistic and natural visual effect, making the approach particularly well-suited for the documentation and restoration of underwater cultural heritage.

Methods

Methods outline

This paper presents an underwater image enhancement model consisting of three components: the Difference Background Light Estimation Algorithm based on Brightness Segmentation (DBE-BS), the Depth-Saturation Fusion Transmission (DSFT) Map Estimation Algorithm, and the Depth-Integrated Color Compensation Model (DICC). The DBE-BS and DSFT Map Estimation components are first applied to generate a preliminary enhanced image, followed by the application of the DICC component to produce the final enhanced image. The detailed process is shown in Fig. 1. First, the image is segmented based on brightness, and background light estimation is performed on each segmented region using a difference method. Then, the DSFT Map Estimation Algorithm integrates depth information with the inverse saturation map, generating a more accurate transmission map based on the relationship between depth and transmission rate. Finally, the DICC is applied during color channel compensation, using image depth data to optimize color correction and enhance the image’s visual quality.

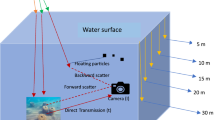

Underwater image formation model

The underwater image formation model decomposes underwater images into three main components: direct, forward scattering, and backward scattering, as shown in Eq. (\(1\)):

where \({E}_{T}\) represents the total irradiance, \({E}_{d}\) is the direct irradiance, \({E}_{f}\) is the forward scattering irradiance, and \({E}_{b}\) is the backward scattering irradiance.

The direct irradiance can be expressed by Eq. (2):

where \({E}_{d}\left(x\right)\) is the direct irradiance at a point \(x\) on the image plane, \(J\left(x\right)\) is the radiance of the object, and \(t\left(x\right)\) is the transmission rate, representing the attenuation of light as it propagates through the underwater medium. \(t\left(x\right)\) can be expressed by Eq. (3):

where \(d\left(x\right)\) is the distance between the camera’s photosensitive element and the object, and \(\eta\) is the attenuation coefficient, indicating the underwater medium’s capacity to absorb light.

The backward scattering irradiance (backward scattering) can be expressed as in Eq. (4):

where \({E}_{b}\left(x\right)\) is the backward scattering irradiance and \({B}_{\infty }\left(x\right)\) is the color vector of the backward scattering light.

Scattering irradiance (forward scattering) can be expressed as in Eq. (5) 25:

where \({E}_{f}\left(x\right)\) is the forward scattering irradiance, and * denotes the convolution with the point spread function \(g\left(x,\lambda \right)\).

Because the distance between the camera and the target is relatively short, forward scattering is ignored, while backscattering remains the primary cause of haze and blurring. The resulting underwater imaging model is:

where \(I\left(x\right)\) is the final imaging model, including direct irradiance and backward scattering irradiance.

As shown in Eq. (6), the transmission rate \(t\left(x\right)\) and the background light value \({B}_{\infty }\left(x\right)\) are the key parameters for determining \(J\left(x\right)\). The DBE-BS method is used to calculate the background light value \({B}_{\infty }\left(x\right)\), and the DSFT method is used to calculate the transmission rate \(t\left(x\right)\).

Difference background light estimation algorithm based on brightness segmentation

The Difference Background Light Estimation Method Based on Brightness Segmentation (DBE-BS) dynamically determines brightness intervals through histogram analysis, followed by difference-based background light estimation for each interval. The image’s grayscale histogram and cumulative distribution function (CDF) are calculated, and the brightness segmentation threshold H is determined using the CDF. The segmentation threshold is defined by Eq. (7):

where CDF is the cumulative distribution function, representing the cumulative number of pixels with grayscale values less than or equal to a certain value. \(k\) is a set of ratios ranging from 0 to 1, representing various percentile positions in the cumulative distribution. \(\frac{1}{N}\) denotes the proportion of the segmented region. By selecting a range of proportional values \(k\) from 0 to 1, the corresponding grayscale values are identified through reverse lookup in the CDF, thereby determining the brightness segmentation threshold \(\text{H}\). This percentile-based approach enables flexible determination of different brightness intervals, adapting to varying lighting conditions in the image and providing an accurate segmentation basis for the subsequent background light estimation.

After completing the image segmentation, the background light for each segmented part is estimated using the difference algorithm, as shown in Eq. (8).

The number of segments \(N\) is adaptively adjusted according to the complexity of the image brightness distribution. The number of segments is determined by the brightness standard deviation \({\sigma }_{L}\), as represented in Eq. (8):

where \({N}_{\min }\) denotes the minimum number of segments, \(\alpha\) is the adaptive factor, and \({\sigma }_{L}\) represents the standard deviation of brightness.

After completing the image segmentation, background light estimation is performed on each segmented region using the difference method, as illustrated in Eq. (9).

where \(M\left(x\right)\) represents the intensity difference between the average of the green channel \(S\left(x\cdot {D}_{G}\right)\) and the blue channel \(S\left(x\cdot {D}_{B}\right)\) and the red channel \(S\left(x\cdot {D}_{R}\right)\). \(S(x\cdot {D}_{R/G/B})\) denotes the intensity of the image in the red, green, and blue channels, respectively. \({wG},{wB},{wR}\) denote the weight factors for each color channel. Based on the results from each underwater archeological data collection, the average brightness for each channel is calculated, and the weight factors are set proportionally.

The background light is estimated by averaging the most significant intensity differences based on \(M\left(x\right)\), as shown in Eq. (10):

where \({B}_{\infty }\) represents the estimated background light intensity, S is the total number of pixels, and \(\psi\) is the percentage parameter. \(L\left({x}_{i}\right)\) represents the value of pixel \({x}_{i}\). Based on the calculation results of \(M\left(x\right)\), a total pixel count of \({S}_{\psi }\) is selected.

Depth-saturation fusion transmission map estimation algorithm

To effectively integrate the inverse saturation map with the depth map, this paper adopts a method based on pixel weight adjustment, which utilizes depth information to influence the saturation representation of the inverse saturation map.

To obtain the transmission map, we use the inverse relationship between the transmission map and the depth map, as shown in Eq. (11):

where \(t\left(x,\lambda \right)\) represents the transmission rate at position \(x\) and wavelength \(\lambda\), \(\eta\) is the attenuation coefficient, and \(d\left(x\right)\) is the distance from the camera to the object.

Therefore, determining the accuracy of \(d\left(x\right)\) is crucial. To obtain an accurate depth map of the image, this paper uses a monocular depth estimation model for depth estimation26. This is accomplished through a two-stage framework. In the first stage, a base model is trained using labeled data to generate an initial depth estimate. The model is then used to generate pseudo-depth labels for a large set of unlabeled images. In the second stage, the labeled data and pseudo-labeled data are combined to train the optimized target model, which produces the depth map. Using Eq. (14), the transmission rate can be calculated.

The attenuation coefficient is used as an adjustable threshold to fine-tune the transmission map. The resulting transmission map requires smoothing, which is achieved using guided filtering. The standard form of guided filtering is:

where \({q}_{i}\) is the filtered transmission map, \({I}_{i}\) is the guidance map, and \({a}_{k}\) and \({b}_{k}\) are coefficients determined by minimizing the following energy function within the window \({\omega }_{k}\) (Eq. 13):

where \({t}_{i}\) is the original transmission map value within the window, and \(\epsilon\) is a smoothness parameter that controls the degree of overfitting. The coefficients \({a}_{k}\) and \({b}_{k}\) are typically solved as shown in Eqs. (14) and (15):

where \({\mu }_{k}\) and \({\sigma }_{k}^{2}\) are the mean and variance of the guidance image \(I\) within the window \({\omega }_{k}\), and \({\bar{t}}_{k}\) is the mean of the transmission map t within the window. Through this approach, guided filtering not only smooths the transmission map but also maintains the sharpness of key edges, which is crucial for the final image restoration.

Additionally, to reduce the impact of artificial light sources on the transmission rate estimation, the issue is addressed using the inverse saturation map. The formula for calculating saturation is:

where \({I}_{c}\left(x\right)\) represents the intensity value of a pixel in the RGB color channel c.

Due to the different attenuation rates of red, green, and blue light in underwater scenes—where red light attenuates faster and blue and green light attenuate less—the saturation is usually higher in underwater scenes without artificial light sources. The inverse saturation map (RMS) is introduced to identify areas affected by artificial light sources and is defined as:

The inverse saturation map \({Sa}{t}_{{rev}}\left(x\right)\) is aligned with the depth map \(D(x)\) at the pixel level and is of the same size. The weight \(w(x)\) is calculated based on the depth value, assuming that the greater the depth, the smaller the impact on the transmission rate. The weight can be defined as:

where \(\alpha\) is an adjustment factor that regulates the sensitivity of depth influence, and \(\max (D)\) is the maximum value in the depth map, ensuring the weight remains within a reasonable range. This weight is used to adjust the values in the inverse saturation map, generating the fused image \({S}_{{fused}}(x)\):

where \(\lambda\) is a coefficient between 0 and 1, used to adjust the intensity of the inverse saturation map.

At this stage, the influence of the inverse saturation map is relatively reduced in deeper regions, while it remains higher in shallower regions. By calculating the transmission rate for each pixel, the transmission map is obtained. Combining this with the method for obtaining background light, a preliminary enhanced underwater cultural heritage image is achieved based on the principles of underwater image formation.

Depth-integrated color compensation model

As light propagates through water, it undergoes attenuation due to absorption and scattering effects, with the degree of attenuation varying across different wavelengths. Shorter wavelengths attenuate more slowly, while longer wavelengths experience faster attenuation. DICC integrates depth information with color compensation methods, and this integration is achieved through the design of a specific model. A model \(E\left(x\right)\) was developed to adjust the color compensation intensity based on the image’s depth map, allowing it to meet the specific requirements of different regions within the image.

where \(D\left(x\right)\) represents the depth value of pixel \(x\). \({D}_{{\rm{thresh}}}\) is the depth threshold used to distinguish depth regions that require different levels of compensation. \(k\) is a parameter that controls the slope of the function, determining the sensitivity of the compensation intensity variation.

In DICC, the settings for the depth threshold \({D}_{{\rm{thresh}}}\) and the parameter \(k\) are determined based on the specific application requirements and image characteristics. The depth threshold \({D}_{{\rm{thresh}}}\) is chosen according to the distribution of depth regions in the image. For example, it can be used to distinguish the foreground from the background or to highlight specific depth ranges. The appropriate threshold can be determined by analyzing the image’s depth histogram or the scene’s needs. In a foreground-background separation scenario, \({D}_{{\rm{thresh}}}\) can be set as the depth that separates the foreground from the background. For cases requiring emphasis on specific depth ranges, the average depth value of the target region can be selected. The parameter \(k\) governs the sensitivity of the compensation intensity to changes in depth. Its selection depends on the desired smoothness of the visual effect. For a more pronounced transition to emphasize depth contrast, a larger \(k\) value is used, while a smaller \(k\) value is chosen for a smoother compensation transition.

According to the CIELAB color model, a local mean is subtracted from each opponent channel, estimated using a Gaussian filter with a large spatial support. This is expressed by Eq. (21).

where each pixel x calculates the compensated opponent color channels \({I}_{a* }^{c}\) and \({I}_{b* }^{c}\). Here, \({I}_{a* }\) and \({I}_{b* }\) represent the initial opponent color channels. \(G{I}_{a* }\) and \(G{I}_{b* }\) are their Gaussian-filtered versions. \(\kappa\) is the compensation intensity parameter, which controls the degree of compensation. The correction levels of the two opponent channels are adjusted using the parameters \(\kappa\) and \(\lambda\).

By processing the preliminarily enhanced image using the DICC method, the color channels are compensated while optimizing color correction with image depth data. This improves the visual quality and restores the original colors of the underwater image.

Results

Sources of archeological data

The primary data for this study comes from four sources, as shown in Fig. 2. The first set of data is from the wreck site of the Jingyuan, an armored cruiser of the Beiyang Fleet during the late Qing Dynasty, which sank on September 17, 1894. The wreck was discovered in 2014, and underwater archeological work was conducted in 2018, during which numerous images were collected, including those of the ship’s nameplate. The site is located in the Yellow Sea near the coast, at an average depth of 10 meters. The seabed consists of silty sand, which is easily disturbed, creating suspended particles and increasing water turbidity, resulting in poor visibility at the bottom, often less than 0.5 meters throughout the year. The second set of data comes from images of an underwater trench in the Xisha Islands. The Xisha Islands consist of 40 islands and reefs, covering a sea area of over 500,000 square kilometers. There are currently 136 underwater cultural heritage sites identified in the South China Sea, with over 110 concentrated in the Xisha Islands. The images in this set were generally collected from shallow locations and exhibit color cast issues. The site of the ancient city of Junzhou is located within the waters of the Danjiangkou Reservoir in Shiyan City, Hubei Province. It was formerly the historical city of Junzhou. The existing underwater remains include key architectural components such as the foundation of Canglang Pavilion, stone inscriptions, and ancient bridges. The water depth at the site ranges from 35 to 42 meters. The wreck site of the Zhiyuan warship is located in the sea southwest of Dandong City, Liaoning Province, at a depth of approximately 18 to 20 meters.

This experiment processed a total of 382 images from both groups. For uniform processing and ease of analysis, all images were resized to a resolution of 1024×1024 before subsequent data processing.

Experimental design

To validate the contribution of each module in the proposed underwater image enhancement method to the final image quality, an ablation experiment was conducted. This experiment combined the DBE-BS, DSFT, and DICC modules to assess each module’s contribution to the image enhancement effects, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The performance evaluation experiment involves a qualitative and quantitative comparison of the resulting images under different environments. Four methods were selected for comparison with the proposed method: Retinex27, UW-CycleGAN21, UDCP28, and UWCNN29. This comparison visually demonstrates the impact of different underwater image processing algorithms on image quality.

At the same time, evaluation metrics are employed to objectively and comprehensively assess the performance of the images. These evaluation metrics include the Patch-based Contrast Quality Index (PCQI) is used to measure the visual quality of underwater images in terms of contrast, color richness, and haziness30. The Underwater Color Image Quality Evaluation Metric (UCIQE) is used to assess the overall visual quality of underwater color images in terms of color, contrast, and brightness31. The Underwater Image Quality Measure (UIQM) is used to evaluate the visual quality of underwater images in terms of colorfulness, sharpness, and contrast32. The Average Gradient (AG) metric is used to evaluate the overall sharpness of an image by measuring the intensity variation between adjacent pixels, reflecting the level of detail and texture clarity. The specific formulas are as follows:

where \({f}_{c}(\Delta I)\) is a function based on the average intensity difference \(\Delta I\), \({f}_{s}(\Delta s)\) is a function based on the signal strength variation \(\Delta s\), and \({f}_{o}(\theta )\) is a function based on the angle \(\theta\) between the signal structures. By scoring local blocks across the entire image and synthesizing these scores into an overall quality score, the overall image quality can be evaluated. The advantage of this method is that it not only provides an overall image quality score, but also ensures that a higher score indicates better image quality.

In this equation, \({\sigma }_{c}\) denotes the standard deviation of chroma, \({{\rm{con}}}_{l}\) represents the brightness contrast, \({\mu }_{s}\) indicates the average saturation, and \({c}_{1},{c}_{2},{c}_{3}\) are the weighting coefficients. The quality of underwater images is evaluated by calculating these three primary components. A higher UCIQE value signifies improved restoration or enhancement of the image.

where \({c}_{1}\), \({c}_{2}\) and \({c}_{3}\) are the weighting coefficients corresponding to each component. Using UIQM, the quality of underwater images can be evaluated without a reference image. This method is particularly suitable for underwater image processing scenarios where ideal images are usually unattainable. It linearly combines the measurements of three underwater image attributes: colorfulness (UICM), sharpness (UISM), and contrast (UIConM). A higher UIQM value indicates better image quality.

Results of ablation experiments

The results of the ablation experiment, which present the average values of UIQM, UCIQE, and PCQI for each module, are shown in Table 1. The proposed method (DBE-BS + DSFT + DICC) achieved the best performance across all metrics, indicating that the synergistic effect of the modules enhanced the clarity, contrast, and color accuracy of the images. The combination without DICC (DBE-BS + DSFT) closely approached the complete method in terms of clarity and contrast but exhibited a decrease in color naturalness, highlighting the critical role of the color compensation module (DICC) in enhancing the color performance of the images. The imaging model utilized a general dark channel method for image enhancement. While it provided some improvements in clarity and contrast, its overall performance fell short compared to other combinations, particularly in color naturalness. This indicates that the imaging model lacks the fine-tuning achieved by DBE-BS and DSFT, as well as the color optimization offered by DICC. The combination using only DICC demonstrated some enhancement in color naturalness, but the effects on clarity and contrast were limited. These results suggest that the DBE-BS, DSFT, and DICC modules each emphasize different aspects and complement one another. The superior performance of the complete method confirms the effectiveness and necessity of the proposed approach. Figure 3 displays some of the image processing results.

Qualitative comparison of enhancing image quality and color restoration

Representative images from three sets of data were selected for display, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The first set of data comes from the Jingyuan Shipwreck site.

As shown in the original image in Fig. 4, the Jingyuan Shipwreck site images reveal the characters “Jing” and “Yuan” on the ship. Due to the turbidity of the underwater environment and the influence of artificial light sources, light scattering has occurred, significantly reducing image details and contrast. Colors are also noticeably affected. Overexposure is observed on both the left and right sides of the image, near the artificial light source. After processing with various image enhancement methods, it was found that the UWCNN method caused complete loss of image details. The Retinex method performed poorly in the underwater environment, failing to significantly improve image clarity. The UDCP method resulted in over-enhancement of colors in some areas of the image. The UW-CycleGAN method also exhibited issues of over-enhancement, leading to color distortion. In contrast, the method proposed in this paper effectively improves the clarity of the text areas, enhances image details and contrast, and excels in color restoration by specifically optimizing for the underwater environment, thus avoiding the issue of over-enhancement.

In Fig. 5, which shows images of the underwater trench in the Xisha Islands, the characteristics of light absorption and scattering in the underwater environment resulted in significant color cast issues, giving the images a noticeable cyan-green tint. This color cast problem severely affected the images’ true rendering and visibility. After processing with various image enhancement methods, it was found that each method had its limitations. The UWCNN method overcompensates for red, resulting in significant oversaturation of red components in the image. The UDCP method overcompensates for green, resulting in an excessive number of green components. The Retinex method, while enhancing the image, over-enhances the dark areas, causing underexposure and detail loss in these regions. The UW-CycleGAN method has an issue of overexposing the bright areas, leading to a loss of detail. In contrast, the method proposed in this paper performs well in both enhancement and color cast correction, effectively addressing the color cast issue in underwater images and improving their visual quality.

In Fig. 6, the original images are affected by factors such as turbidity, uneven lighting, and spectral absorption of seawater, resulting in overall low contrast, blurriness, and color casts toward green or yellow. Some areas even exhibit significant lighting imbalance and information occlusion. The Underwater Retinex method shows a noticeable improvement in brightness but suffers from an overall grayish tone and insufficient detail enhancement. The UDCP method improves image sharpness but causes over-saturation in some regions, compromising visual realism. The UWCNN method results in severe loss of detail, with blurred salient target regions. The UW-CycleGAN method introduces noticeable color distortion, rendering the images overly reddish and dark, with inadequate contrast for target structures. In contrast, the method proposed in this study achieves performs well in image sharpness, contrast, and color restoration.

Quantitative comparison of enhancing image quality and color restoration

For evaluation metrics, the UIQM, UCIQE, PCQI and AG values were calculated for five selected images. The results are shown in Table 2.

From the experimental results, it is evident that different image processing methods show significant differences across various evaluation metrics. For the first image’s evaluation metrics, the Retinex method performs well in terms of Underwater Image Quality Measure (UIQM), indicating its effectiveness in enhancing image details and overall quality. However, it does not perform well in the Underwater Color Image Quality Evaluation Metric (UCIQE) and the Perceptual Contrast Quality Index (PCQI), indicating shortcomings in color restoration and contrast enhancement. For the fourth and fifth images, the UW-CycleGAN method performs well in UCIQE and PCQI, reflecting its advantages in color enhancement and perceptual contrast. However, other metrics, such as UIQM is poor, indicating significant limitations in overall image quality and detail recovery, and it fails to comprehensively improve image quality. The method proposed in this paper excels across all metrics.

Figure 7 presents the results of the significance analysis. The findings reveal that other methods exhibit significant deficiencies across various metrics, typically characterized by lower average values and greater variability, making it challenging to achieve consistent performance across different images. In contrast, the proposed method reached the highest average values for all key metrics (UIQM, UCIQE, PCQI, AG), outperforming other methods while demonstrating a smaller standard deviation, indicating greater stability. This indicates that the proposed method excels in image quality enhancement, and color enhancement, enabling consistent and high-quality underwater image enhancement across various images, thus surpassing other methods in clarity and color restoration.

Discussion

Compared to existing image enhancement methods, the approach proposed in this paper demonstrates more reliable performance in underwater environments. Among the comparison methods, the UWCNN method can enhance the image, but excessive enhancement in certain regions leads to a loss of image details and fails to effectively restore the clarity of underwater images. The Retinex method, due to the complexity of underwater lighting conditions, does not significantly improve image clarity and still suffers from insufficient exposure in darker areas. The UDCP method causes color distortion due to over-enhancement in some regions and fails to effectively restore the image’s natural color tone. The UW-CycleGAN method results in overexposure in bright areas, leading to the loss of certain details.

In contrast, the method proposed in this paper optimizes the image enhancement process by incorporating several key modules. The DBE-BS and DSFT modules effectively mitigate the issue of excessive enhancement in underwater images, preserving more image details. The DSFT algorithm, which integrates depth information, prevents the over-enhancement observed in the UWCNN method, improving image clarity. For color restoration, the DICC algorithm addresses the potential distortion issues during color enhancement in the UDCP method, ensuring the naturalness and authenticity of the image’s color tone. Furthermore, by considering the complex lighting conditions of the underwater environment, the proposed method successfully avoids the underexposure and overexposure in bright areas that are present in the Retinex and UW-CycleGAN methods, thus further improving the overall image quality.

Despite this, the method proposed in this paper still faces some challenges and opportunities for improvement. The data were collected at depths ranging from 0 to 42 meters. Within this depth range, light attenuation is moderate, and water quality remains relatively stable. The current results clearly demonstrate the method’s enhancement effects within this depth range. Validation for deeper depths, more complex water quality, and lighting conditions (such as low light and strong scattering) has not been addressed in this study due to the lack of corresponding data. In future work, we plan to expand the scope of data collection and include more complex underwater environments to further validate and optimize the method’s applicability and performance.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ancuti, C. O., Ancuti, C., De Vleeschouwer, C. & Sbert, M. Color Channel Compensation (3C): A fundamental pre-processing step for image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process 29, 2653–2665 (2020).

Berman, D., Levy, D., Avidan, S. & Treibitz, T. Underwater single image color restoration using haze-lines and a new quantitative dataset. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 43, 2822–2837 (2020).

Song, H., Chang, L., Chen, Z. & Ren, P. Enhancement-Registration-Homogenization (ERH): A comprehensive underwater visual reconstruction paradigm. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 6953–6967 (2022).

Zhang, W., Wang, Y. & Li, C. Underwater image enhancement by attenuated color channel correction and detail preserved contrast enhancement. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 47, 718–735 (2022).

Li, X., Hou, G., Li, K. & Pan, Z. Enhancing underwater image via adaptive color and contrast enhancement, and denoising. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 111, 104759 (2022).

Wang, H., Sun, S. & Ren, P. Meta underwater camera: A smart protocol for underwater image enhancement. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 195, 462–481 (2023).

Wang, H., Sun, S. & Ren, P. Underwater color disparities: cues for enhancing underwater images toward natural color consistencies. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 34, 738–753 (2024).

Zhuang, P. & Ding, X. Underwater image enhancement using an edge-preserving filtering Retinex algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 79, 17257–17277 (2020).

Qi, H., Zhou, H., Dong, J. & Dong, X. Deep color-corrected multiscale retinex network for underwater image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–13 (2024).

Ge, W., Lin, Y., Wang, Z. & Yang, T. Multi-prior underwater image restoration method via adaptive transmission. Opt. Express 30, 24295–24309 (2022).

Song, W., Wang, Y., Huang, D., Liotta, A. & Perra, C. Enhancement of underwater images with statistical model of background light and optimization of transmission map. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 66, 153–169 (2020).

Yu, H., Li, X., Lou, Q., Lei, C. & Liu, Z. Underwater image enhancement based on DCP and depth transmission map. Multimed. Tools Appl. 79, 20373–20390 (2020).

Liu, K. & Liang, Y. Enhancement of underwater optical images based on background light estimation and improved adaptive transmission fusion. Opt. Express 29, 28307–28328 (2021).

Liu, D., Zhou, J., Xie, X., Lin, Z. & Lin, Y. Underwater image restoration via background light estimation and depth map optimization. Opt. Express 30, 29099–29116 (2022).

Zhou, J., Yang, T., Chu, W. & Zhang, W. Underwater image restoration via backscatter pixel prior and color compensation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 111, 104785 (2022).

Song, Y., She, M. & Köser, K. Advanced underwater image restoration in complex illumination conditions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 209, 197–212 (2024).

Hao, Y. et al. Texture enhanced underwater image restoration via Laplacian regularization. Appl. Math. Model. 119, 68–84 (2023).

Ren, T. et al. Reinforced Swin-Convs transformer for simultaneous underwater sensing scene image enhancement and super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–16 (2022).

Cong, R. et al. PUGAN: Physical model-guided underwater image enhancement using GAN with dual-discriminators. IEEE Trans. Image Process 32, 4472–4485 (2023).

Peng, L., Zhu, C. & Bian, L. U-shape transformer for underwater image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process 32, 3066–3079 (2023).

Yan, H. et al. UW-CycleGAN: Model-driven CycleGAN for underwater image restoration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–17 (2023).

Gao, S., Wu, W., Li, H., Zhu, L. & Wang, X. Atmospheric Scattering model induced statistical characteristics estimation for underwater image restoration. IEEE Signal Process. Lett 30, 658–662 (2023).

Huang, S., Wang, K., Liu, H., Chen, J. & Li, Y. Contrastive semi-supervised learning for underwater image restoration via reliable bank. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 18145–18155 (2023).

Zhao, C., Cai, W., Dong, C. & Hu, C. Wavelet-based Fourier information interaction with frequency diffusion adjustment for underwater image restoration. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 8281–8291 (2024).

Chang, H.-H., Cheng, C.-Y. & Sung, C.-C. Single underwater image restoration based on depth estimation and transmission compensation. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 44, 1130–1149 (2019).

Yang, L. et al. Depth Anything: Unleashing the Power of Large-Scale Unlabeled Data. arXiv 2401.10891 (2024).

Fu, X. et al. A retinex-based enhancing approach for single underwater image. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Image Process. 2014, 4572–4576 (2014).

Drews, P. Jr, Do Nascimento, E., Moraes, F., Botelho, S. & Campos, M. Transmission estimation in underwater single images. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2013, 825–830 (2013).

Li, C., Anwar, S. & Porikli, F. Underwater scene prior inspired deep underwater image and video enhancement. Pattern Recognit 98, 107038 (2020).

Wang, S., Ma, K., Wang, Z. & Lin, W. A patch-structure representation method for quality assessment of contrast changed images. IEEE Signal Process. Lett 22, 2387–2390 (2015).

Miao, Y. & Sowmya, A. An underwater color image quality evaluation metric. IEEE Trans. Image Process 24, 6062–6071 (2015).

Panetta, K. & Gao, C. Human-visual-system-inspired underwater image quality measures. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 41, 541–551 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61902016), Graduate Student Innovation Projects of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture (No. PG2024121), Postgraduate Education and Teaching Quality Improvement Project of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture (No. J2023002), Engineering Research Center of Integration and Application of Digital Learning Technology, Ministry of Education (No. 1311001), Education and Teaching Research Project of China Construction Education Association (No. 2023007) and Beijing Education Science 14th Five Year Plan Project (No. CDDB24252).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Q.: conception and design of the work, data analysis, problem modeling, writing—review and editing. T.L.: data analysis, writing—original draft. J.W.: data acquisition, data curation. S.W.: conception and design of the work, methodology, problem modeling, and funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, D., Liu, T., Wang, J. et al. Underwater heritage image enhancement and color restoration integrating partitioned background light estimation and deep fusion. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 319 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01899-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01899-1