Abstract

Place names, as cultural heritage, include significant regional, geographic, and socio-historical information. Understanding their spatiotemporal distribution is critical for elucidating human-land interactions. This study employs ArcGIS software, integrating historical maps and local chronicles, to analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of toponymic cultural heritage (TCH) of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin, since the eighteenth century. Our analysis reveals: (1) Spatially, TCH exhibits highest density in the alluvial plain, concentrating within a 0–2 km buffer zone of rivers, reflecting intense water-centric human activity. (2) Quantitatively, TCH experienced an initial slow accumulation followed by rapid growth. (3) TCH can be categorized into natural and humanistic landscape classifications. Natural TCH is influenced by elevation and hydrography, while humanistic TCH is shaped by water resource utilization strategies, regional development, and demographic shifts. Preserving this TCH offers substantial cultural resources and a theoretical foundation for local knowledge transmission, fostering social identity, and promoting sustainable development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage encompasses objects and cultural forms created by humans and transmitted across generations, including language, customs, traditions, monuments, sites, and works of art, which embody the lifestyle of a society or a social group1. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognizes cultural heritage in both tangible and intangible forms. Place names, defined as the proper nouns assigned by humans to specific natural or cultural geographical entities at particular locations2, were officially recognized as intangible cultural heritage at the 24th session of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) in 20073. Toponymic cultural heritage (TCH) represents a valuable resource of regional, geographical, civilizational, historical, and cultural information, providing insights into both the local geographical environment and the cultural landscape of specific historical era4,5. Settlements, as centers of production and social activities, embody a comprehensive adaptation to the surrounding natural environment, shaped by culture traditions, socio-economic realities, and cultural landscapes6. The study of TCH of settlements offers interdisciplinary insights into human-environment relationships and has generated a substantial body of research7,8,9,10,11,12.

The utilization of TCH is increasingly recognized globally as a strategy for fostering the cultural industry growth and safeguarding cultural heritage. Several nations, including the United States13, the United Kingdom14, Ireland15, Italy16, and China17, have established dedicated place name research institutions to investigate and preserve this valuable cultural asset. Current research on the TCH integrates traditional toponymic perspectives, including linguistic origin18, semantics19, classification20, and the role of place names in shaping identity21,22,23. Related areas, such as place name politics, are also explored24,25,26,27. Recently, scholars have broadened their investigations to encompass new perspectives. This includes focusing on specific types of the TCH, such as those related to water-related place names7, Biantun place names28, and cultural administrative place names29. These studies highlight the influence of the natural environment, social history, and cultural traditions on the composition and evolution of TCH. While studies have examined spatial distribution in place names research30,31, investigations into that of TCH remain limited10. Understanding the complex relationship between natural, socio-economic, historical, and cultural determinants and the resulting spatiotemporal distribution of TCH requires comprehensive research. Analyzing the spatiotemporal dynamics of TCH and identifying their driving factors is fundamental for the long-term preservation of regional cultural landscapes and for the creation of effective strategies for heritage conservation and management.

Water-related settlement place names often derive from associations with water sources, are characterized by referring to components such as rivers, lakes, fluvial landforms, water conservancy projects, water management techniques, and hydraulic infrastructures. Current research on this topic is largely concentrated in humid regions32,33, focusing on the origins, etymology, evolution, typology, and spatiotemporal distribution of TCH34,35. Arid areas, characterized by low precipitation and water scarcity, highlight water as a critical determinant of human survival and development. As a distinct form of cultural heritage in arid environments, the spatial distribution and evolution of water-related settlement place names offer insights into how human populations create a habitable space in the water-scarce environment. Moreover, they illuminate the cultural, social, and historical dimensions reflected in these place names across different temporal and spatial scales. Consequently, exploring the spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of TCH of water-related settlement place names in arid regions is significant10. This research provides an empirical contribution to international place name studies and advances the refinement of research on specific place name types at a specific regional scale.

Located in the heart of Eurasia, Xinjiang is a representative arid region that is characterized by annual precipitation averaging below 200 mm in most areas36. Since the eighteenth century, the Chinese government has initiated substantial irrigation projects in the northern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains, in order to drive significant agricultural expansion37. This large-scale land conversion, centered on water management and agricultural practices, fostered the appearance of TCH of water-related settlement place names in the northern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains. Consequently, the northern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains are a critical area for investigating the TCH of water-related settlement place names, particularly given the long history of human adaptation to scarce water resources. These TCHs persist today, representing significant cultural resources that deserve to be protected and further studied.

The Manas River Basin, a representative arid ecosystem situated on the northern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang and bordering the southern Gurbantunggut Desert, is a typical area for research on the TCH of water-related settlement place names. Driven by Xinjiang’s policy guideline “reclaiming land and guarding the border areas”, agricultural economic development has been rapid in the Manas River Basin, contributing substantially to the modern Tianshan North Slope Economic Zone38. However, this development raises concerns regarding water resource management and the sustainable preservation of the basin’s ecological and cultural heritage.

Pastures land use was extensive in the Manas River Basin before the eighteenth century. The Qing Dynasty’s implementation of land reclamation and cultivation policies during the eighteenth century fundamentally altered the land use pattern39. Following the continuation of these policies, the Manas River Basin evolved into a crucial agricultural center on the northern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains by the 1940s40. Large-scale agricultural reclamation significantly altered the landscape and demographics of the Manas River Basin. Cultivated land area increased from 140.5 km2 in 1909 to 241.7 km2 in 1944, indicating an average annual expansion of 2.9 km2 41. Simultaneously, the population grew dramatically, expanding from 16,042 in 1909 to 56,216 in 1944, corresponding to an average annual growth rate of 3.65%37. In 1954, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) identified the Manas River Basin as a strategic development zone. This decision promoted rapid expansion of the basin’s agricultural economy, leading to its establishment as a globally recognized center for cotton production since the 1960s42. Despite limited water resources, the irrigation system of the Manas River and its tributaries have fostered a unique TCH in the area. Therefore, this study aimed to:

-

(1)

Develop a classification framework for the TCH of water-related settlement place names, grounded in the distinctive features of the TCH.

-

(2)

Investigate the spatiotemporal distribution of different categories of place-name cultural heritage. This inquiry will utilize ArcGIS spatial analysis and a cross-sectional methodological approach, integrating natural environmental factors of the Manas River Basin with historical information (from the eighteenth century to present) concerning economic activities, demographic trends, and water resource utilization. The aim is to ascertain the principal drivers shaping the emergence, evolution, and spatial and temporal patterns of the TCH.

-

(3)

Recommend pragmatic strategies for the conservation and sustainable management of the TCH in arid regions, approached from a heritage protection standpoint.

By exploring these questions, this research advances the understanding of the TCH in arid regions. The insights gained regarding the spatial distribution and influencing factors of such heritage offer a valuable foundation for future research endeavors. Moreover, the study’s findings have direct practical implications, enabling policymakers to design and implement more effective strategies for the preservation and sustainable utilization of the TCH resources.

Methods

Study area overview

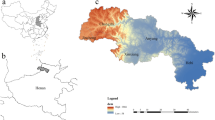

Situated at the northern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains and the southern periphery of the Junggar Basin, the Manas River Basin exhibits a steep topographic gradient (Fig. 1). This gradient manifests as a significant altitudinal decline from southeast to northwest, spanning elevations from 256 m to 5242.5 m, resulting in an average vertical drop of 17.84 meters per kilometer. The basin can be divided into five distinct geomorphological zones: (1) the southern Tianshan mountainous zone, characterized by elevations ranging from 3500 to 5000 m; (2) the low to mid-altitude mountainous regions, elevations ranging from 500 to 2500 m, defined by east-west trending ridges, steep valleys, well-developed terraces, and a dense vegetation cover. This unique combination of topographic and vegetative attributes these regions optimal for mountain pastures; (3) the piedmont plain, composed of coalesced alluvial fans, notable for substantial spring discharge and abundant water resources; (4) alluvial floodplains, characterized by broad riverbeds and flat terrain; (5) the northern desert region, dominated by extensive aeolian sand dunes and relict lacustrine depressions. The basin is endowed with a relatively well-developed surface water system, evidenced by the presence of six major fluvial systems (Taxi River, Manas River, Ningjia River, Jingou River, Shawan River, and Bayingou River). The confluences of alluvial fans from these rivers have engendered four major spring source areas—the Shihezi Spring Water Area, Ulan Wusuwei Lake, Jingou River Spring Water Valley, and Daquan Yejia Lake—collectively forming a substantial spring-fed hydrogeological zone within the basin.

The Manas River Basin represents a typical agricultural region within an arid environment, where agricultural productivity is fundamentally constrained by water resource availability43. Subsequent to the Qing government’s large-scale agriculture exploitation, commencing in 1761 (the 26th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign), the Manas River Basin had become an important destination for immigrants. This continuous immigration facilitated the gradual formation of an immigrant society, predominantly composed of agriculturalists and resulted in the widespread adoption of new Chinese place names. These place names have come to dominate the local toponymy. Characterized by their simplicity and directness, these place names often provide valuable insights into the region’s environmental characteristics. Agricultural immigrants have profoundly transformed the landscape through the development of extensive irrigation infrastructures. Furthermore, significant modifications to the basin’s fluvial channels were implemented during the twentieth century via the construction of water conservancy projects44. These anthropogenic alterations, enabling agricultural expansion within the basin, have likely exerted substantial impacts on the natural hydrological regime and the TCH of water-related settlement place names. Constraints in water resources necessitated cooperative and location-based water allocation system among immigrant communities in the Manas River Basin. The confluence of extensive historical land reclamation, intricate riverine geomorphology, and a well-developed immigrant culture has fostered a distinctive TCH of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin.

Data sources and processing

Data pertaining to water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin were primarily derived from place name gazetteers compiled during the First National Place Name Census of the People’s Republic of China (1983): Place Name Atlas of Manasi County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region45, Place Name Atlas of Shawan County46, Place Name Atlas of Shihezi City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region47, and Place Name Atlas of Kelamayi City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region48. To supply information regarding abandoned settlements, historical documents, including Annotation of Western Regions49, Xinjiang Atlas50, and Xinjiang Local Records Manuscript51, were consulted. Settlement place names recorded in the place name gazetteers were systematically tabulated and categorized according to contemporary administrative division, founding date, etymological origin, and frequency. Subsequently, geographic coordinates (longitude and latitude) for each place name were extracted utilizing Google Earth, and all attribute data from the atlases were imported into ArcGIS 10.2 to construct a database of 356 place names. The 30 m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences data cloud platform (https://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed on 12 July 2024)). The 30 m resolution Land use data were derived from China’s annual land cover data from 1990 to 2019 (accessed on 20 April 2025)52.

Research idea

To analyze the spatial distribution and spatiotemporal evolution of cultural heritage within water-related settlements in the study area, this research utilizes kernel density estimation (KDE) and buffer analysis53. Specifically, KDE is employed to visualize the spatial distribution patterns of distinct temporal-cultural heritage types associated with settlement places and to evaluate the concentration trends in settlement distributions. Furthermore, ArcGIS buffer analysis is used to investigate the relationship between the spatial distributions of the TCH associated with settlements and river systems. Finally, KDE is applied to analyze the historical evolution of TCH of water-related settlement place names across four different periods: 1761–1863 (corresponding to the period of large-scale exploitation of the Manas River Basin commencing in 1761 and terminating with the outbreak of a major war in the whole Xinjiang in 1863), 1864–1911 (representing the war period, the post-war recovery period and subsequent regional development), 1912–1953 (encompassing the period of the Republic of China and the early years of the People’s Republic of China), 1954–1983 (spanning from the establishment of the XPCC in 1954 to the First National Place Name Census of the People’s Republic of China in 1983).

Kernel density estimation

Kernel density estimation (KDE), a non-parametric spatial statistical approach, is employed to estimate the probability density function of point-referenced spatial data. KDE provides a robust measure of spatial point concentration and enables the identification of significant variations in the distribution patterns of cultural heritage sites across different regions. The kernel density estimator is defined by the following formula:

in this formula, K(x) represents the kernel density value; n is the number of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin; d (d > 0) denotes the search radius; a signifies the weight value; and x − xi represents the distance between location x and sample location x − xi. A higher K(x) value indicates a greater density of water-related settlement place names, reflecting a higher degree of spatial clustering.

Buffer analysis

Buffer analysis, a fundamental spatial analysis method, creates a polygon layer representing a zone of specified width around a spatial feature (point, line, or polygon). This allows for quantifying the influence of that feature on its surroundings. In this study, buffer zones around rivers (linear features) are generated to investigate the spatial association between rivers and the distribution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. This approach enables the assessment of the proximity of settlements to rivers and provides insights into the potential influence of water resources on settlement location.

Results

Statistics and classification of water-related settlement place names

Water resources are a critical determinant in arid regions, exerting a profound influence on human settlement patterns and the formation of cultural landscapes. This dependence is substantiated by the prevalent occurrence of water-related settlement place names. The formation, development, and evolution of toponyms are shaped by the dynamic interaction between the characteristics of the local aquatic environment and the imprint of human activities. As such, hydronyms often encapsulate and reflect salient features of the surrounding water environment. The proximity of settlements to specific hydrological features, such as rivers and river bends, often results in corresponding water-related settlement place names, thereby reflecting the spatial relationship between human settlements and the local water environment. While place names frequently mirror elements of the natural geographical environment, including topography and hydrological characteristics, their formation is not solely determined by these factors. Hydronyms associated with artificial water infrastructure, such as canals, bridges, reservoirs, and dams, further demonstrate the influence of the social environment, revealing a rich tapestry of social and cultural characteristics interwoven with the management and utilization of water resources. In the Manas River Basin, 439 different Chinese characters were included in the 356 water-related settlement place names. These 356 water-related settlement place names could be categorized into natural and humanistic landscape toponyms. Toponyms within the natural landscape classification directly reflect the attributes of surface water features and surrounding geomorphological landforms. They can be further subdivided into two sub-classifications: toponyms relating to landforms and those relating to hydrological features. Toponyms within the humanistic landscape classification originate from the interaction and changes between humans and natural water resources, and no secondary classification is made here (Table 1).

Semantic classification, as detailed in Table 1, reveals that 198 water-related settlement place names are rooted in natural landscape features, representing 55.61% of the total. This contrasts with the 44.39% reflecting anthropogenic influences, suggesting a greater historical emphasis on natural features in place naming practices. Within the natural landscape category, place names referencing hydrological characteristics, are the most prevalent, followed by those derived from riverine landforms. These water-related settlement place names collectively illustrate the salient natural water environment characteristics of the Manas River Basin, reflecting a historical understanding and cognitive representation of features such as river morphology and hydrological processes. The prominence of terms related to rivers, for instance, underscores the reliance of communities on this vital water source in this arid region.

Within the settlement place names related to river landform, the terms “river bend”, “gully”, “marsh”, and “groove” are frequently employed, collectively accounting for 78 instances, representing 21.91% of the total water-related settlement place names. The toponymic element “Wan” (湾) typically describes a concave bend in a river or channel, resulting from differential erosion and sediment deposition processes on the outer and inner banks, respectively. In other instances, “Wan” is combined with “Keng” (坑) to denote a localized depression containing water. For example, Erdaowan (二道湾) Village’s toponym alludes to its geographical position east of the second river bend, formed by the Jingou River. Furthermore, Shangkengwan (上坑湾) Village’s toponym references a notable water feature, a year-round, water-filled river bend situated between Shangkengwan and the adjacent settlement, Xiakengwan (下坑湾). The toponymic element “Gou” (沟) commonly signifies a channelized geomorphological feature shaped by concentrated water flow, often resulting from perennial streams, spring discharge, or the occurrence of periodic flood. Shuigou (水沟) Village, for instance, derives its name from a natural watercourse, a gully formed by the confluence of spring waters draining from the adjacent mountainous terrain. “Wa” (洼) denotes a low-elevation area characterized by saturated pedological conditions and frequent inundation. An illustrative example is Yawakeng (鸭洼坑) Village, whose toponym reflects the presence of a topographic depression that historically provided a seasonal habitat for migratory waterfowl during vernal and autumnal migrations. “Tan” (滩) signifies a wetland environment characterized by saturated soils and the presence of hydrophytic vegetation. For example, Caotanhu (草滩湖) Village derives its name from the proximate reed-dominated grasslands. “Cao” (槽) is defined as a linear depression, typically U-shaped in cross-section, with relatively steep banks flanking a lower-lying channel bed. Jiacaozi (夹槽子) Village exemplified this. Its name originates from its position within a paleo-flood channel situated along the geomorphological transition between undulating hills and level plain.

Settlement place names associated with hydrological features frequently incorporate terms such as “Quan” (泉), “He” (河), and “Hu” (湖), reflecting characteristics of the hydrological landscape. This subset comprises 120 toponyms, accounting for 33.7% of the total water-related settlement place names identified within this study. The term “Quan,” within the context of the Manas River Basin, typically designates an area of concentrated groundwater discharge where coalesced alluvial fans facilitate subsurface flow. Zhongquan (中泉) Village’s toponym underscores the significance of this resource, its designation reflecting the settlement’s central location relative to three major spring outlets. “He” (河) in this context refers to the principal fluvial systems within the basin, such as the Taxi River, Manas River, and Jingou River. For example, Jinhepan (金河畔) Village derives its toponymy from its location on the bank of the former Jingou River channel. “Hu” (湖) in this study includes both the Shihezi Mushroom Lake Reservoir, representing human alteration of the landscape through impoundment within an existing inter-alluvial fan depression the natural reed-dominated lake system in the lower Taxi River watershed. The toponyms of Huxi (湖西) Village and Huxinyi (湖心驿) Village serve as evidence of this interplay, the former indicating proximity to the existing reservoir, and the latter reflecting the relict presence of a desiccated wetland.

Beyond the influence of natural water environment factors, anthropogenic activities also exert a considerable impact on the water-related settlement place names. As presented in Table 1, a total of 158 water-related settlement place names classified as reflecting human influence were identified, constituting 44.39% of the total sample. Specifically, place names derived from canals, bridges, and water diversion systems offer valuable insights into the technological systems and historical water management practices that have shaped the cultural landscape of the region. These hydronyms typically encapsulate information regarding social organization, economic activities, and technological innovations related to the exploitation and regulation of water resources.

Water-related settlement place names in the humanistic landscape classification, commonly incorporate elements such as “Qu” (渠), “Qiao” (桥), “Gong” (工), “Ping” (坪), and “Jing” (井), reflecting human adaptation and utilization of aquatic environments. Among them, the toponymic element “Qu” denotes a channel or artificial waterway, an attribute reflected in the name Erdaoqu (二道渠) Village, which originates from a branch canal excavated in the vicinity. Similarly, “Qiao” indicates the presence of a bridge near a settlement; the toponym Banqiao (板桥) Village, for example, commemorates the construction of a wooden bridge across a local river, facilitating access between Laoshawan (老沙湾) Township and Manas County. “Gong” (工) is associated with irrigation canals. For instance, Tougong (头工) Village is named for its proximity to the primary irrigation canal constructed by Qing Dynasty troops stationed in Manas. The term “Ping” (坪), conversely, denotes the act of water diversion; Sanchaping (三岔坪) Village, for example, derives its toponym from its location at the confluence of three diverging branch canals: Dongqu (东渠), Xiqu (西渠), and Chenjiaqu (陈家渠).

In summary, the statistical analysis and semantic classification of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin, as summarized in Table 1, reveal a predominance of names rooted in natural features, indicative of the basin’s complex topography and well-developed hydrological network fed by glacial meltwater and snowmelt. Concurrently, the presence of hydronyms reflecting human influences underscores the rich cultural connotations embedded within the landscape. Specifically, terms denoting canals, dams, and reservoirs suggest that agricultural reclamation efforts by immigrants, primarily from the Shaanxi and Gansu provinces, were characterized by strong social cohesion, wherein shared origins and cooperative labor, facilitated by traditional village-based organizational structures, facilitated the construction of water infrastructures and the establishment of new settlements. Ultimately, the TCH of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin serves as a powerful testament to the intricate relationship between human settlement patterns and environmental constraints in an arid landscape. These place names collectively illustrate how immigrant communities adeptly leveraged geographical knowledge and hydrological resources to establish viable and interconnected societies54.

Spatial distribution characteristics of TCH of water-related settlement place names

Kernel density analysis was employed to investigate the spatial distribution characteristics of 356 water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin. Results indicate the density of 0.014 place names per square kilometer, revealing a spatially heterogeneous distribution pattern characterized by a pronounced concentration in the central region and a sparse distribution along the northern and southern peripheries (Fig. 2a). This concentration aligns with the location of the Manas River alluvial fan, which provides fertile agricultural land and a reliable source of irrigation water. Conversely, the sparse distribution in the northern and southern peripheries corresponds to mountainous and desert regions with limited agricultural potential and lower population densities. Figure 2a visually demonstrates this density gradient, with darker shading in the center indicating a higher concentration of water-related settlement place names.

The spatial distribution of water-related settlement place names derived from natural landscape features directly reflects the influence of the local natural environment. The undulating topography and dispersed hydrological network of the Manas River Basin have fostered a settlement pattern characterized by clustered communities along major river systems, particularly the Manas River, the Taxi River, and the Jingou River (Fig. 2b). Figure 2b shows this clustering clearly, with settlement locations closely aligned with the river courses.

Statistical analysis demonstrates a marked concentration of water-related settlement place names associated with river landforms in the central plain area, representing 76% of the total. The area of highest core density aligns spatially with the alluvial fan zone (Fig. 3a), suggesting a strong environmental influence on toponymic development. Place name counts and proportions are comparatively lower in the southern mountainous terrain and along the northern desert margins.

The spatial influence of rivers on toponymic development is geographically constrained. As illustrated in Fig. 4, a negative correlation exists between distance from fluvial systems and the density of water-related settlement place names, attributable to topographical and geomorphological factors. In the Manas River Basin, a discernible spatial gradient is evident in place naming conventions. Within a 0–4 km buffer zone surrounding rivers, the term “river bend” exhibits the highest prevalence. As distance from river systems increases, and terrain elevation rises, toponyms tend to incorporate descriptors such as “Gou” (沟), “Keng” (坑), and “Tan” (滩).

Related to river landforms The number of the distribution of the TCH related to river landforms in different buffer zone, Related to hydrological features the number of the distribution of the TCH related to hydrological features in different buffer zone, Related to hydraulic engineering the number of the distribution of the TCH related to hydraulic engineering in different buffer zone.

Statistical analysis reveals a significant concentration of 92 water-related settlement place names associated with hydrological features in alluvial plains, 23 within mountainous areas, and none in desert environments (Fig. 3b).

Proximity to rivers exerts a significant influence on the density of water-related settlement place names associated with hydrological features. As depicted in Fig. 4, a positive correlation is observed between fluvial proximity and the number of these toponyms. Toponymic analysis reveals distinct patterns within different proximity buffers. Within the 0–2 km buffer zone, 40 place names were identified, with a notable prevalence of terms such as “He”, “Hu”, and “Quan”. As distance from fluvial systems increases, the number of place names decreases, and the toponymic composition shifts, with “Hu” and “Quan” becoming the dominant terms. This suggests a strong association between immediate fluvial proximity and toponymic diversity, with a gradual transition towards toponyms reflecting specific hydrological features (lakes and springs) as distance increases.

The spatial distribution of water-related settlement place names reflecting human landscape modifications underscores human adaptation and resource management strategies within the Manas River Basin. Historically, seasonal fluctuations in water availability and the inherent challenges of water allocation have prompted investment in water infrastructure, notably the construction of canal systems. Consequently, the spatial expansion of settlements has been oriented along these canal systems, which remain integral to both economic activities and daily life (Fig. 2c).

Statistical analysis reveals that water-related settlement place names within the humanistic landscape classification are predominantly concentrated in the alluvial plain, accounting for 92% of such place names. Within this region, Lanzhouwan Town (兰州湾乡) and Shihezi Town (石河子乡) exhibit the highest settlement density, while Xinhu Farm (新湖农场), Liumaowan Town (柳毛湾乡), Laoshawan Town (老沙湾乡), and Sidaohezi Town (四道河子乡) demonstrate comparatively lower density (Fig. 2c). Figure 2c visualizes the spatial relationship, indicating high settlement density in the central alluvial plain region, aligning with the prevalence of human-influenced hydronyms. Lanzhouwan and Shihezi were selected for further examination due to their contrasting settlement patterns, as visualized in Fig. 2c. The establishment of water management infrastructure, particularly early canal systems, was instrumental in facilitating settlement and agricultural expansion in Lanzhouwan Town and Shihezi Town, commencing during the Qianlong period (1736–1795 A.D.). Situated on the Manas River alluvial plain, Lanzhouwan Town possesses level topography and enjoys advantageous access to both natural water sources and engineered irrigation systems, including the nearby historic Mohequ (莫合) Canal. This accessibility facilitated the establishment of the town by Han Chinese migrants primarily from Shaanxi and Gansu province. Following 1949, Shihezi Town, located in the upper-middle section of the Manas River alluvial fan within a piedmont inclined plain, underwent significant development of its irrigation infrastructure. This development, largely attributed to the XPCC in 1954, resulted in a sophisticated network comprising modern, concrete-lined open canals tapping into groundwater resources. This water was crucial for the establishment of cotton farms.

Figure 4 reveals a distance-decay relationship between the density of water-related settlement place names and distance from the river channel. The 0–2 km buffer zone exhibits the highest concentration of 40 settlement place names. This spatial pattern, largely confined to the alluvial plain, implies that initial settlement patterns were heavily dictated by ease of access to riverine water. While proximity to the river afforded advantages in terms of shallow groundwater and suitable topography for irrigation infrastructure, this concentration also suggests a limited capacity for water resource management beyond the immediate river corridor in the early stages of settlement. Beyond the 0–2 km buffer zone, a marked decrease in settlement place name density is observed, coupled with the appearance of such names in the southern mountainous regions and along the northern desert fringe. The 2–4 km buffer exhibits a reduction of over 50% (19 place names), potentially reflecting both the diminishing accessibility of fluvial water sources and an increased reliance on localized precipitation or groundwater. Continued decreases are noted in the 4–6 km (12 place names), 6–8 km (9 place names), and 8–10 km (10 place names) zones. These spatial patterns suggest an inherent trade-off: while proximity to river systems provides optimal conditions for settlement and agriculture, human expansion into more marginal environments necessitates technological innovation and the implementation of diverse water management strategies.

In summary, the TCH of spatial patterns of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin elucidates utilization and alteration of the natural environment, particularly concerning water resources. The toponymic distribution reflects both the constraints and opportunities presented by the natural environment, while the water-related settlement place names within the humanistic landscape classification clarify the intricate relationship between human actions and water resource changes within an arid context.

Temporal and spatial evolution of TCH of water-related settlement place names

Analyzing the spatial distribution and evolution characteristics of the TCH of water-related settlement place names across historical periods offers insights into the evolving spatial extent of human activities in the region from the eighteenth century to the present. Specifically, it allows us to reconstruct past settlement patterns, evaluate adaptation strategies to specific ecological niches, and assess the impact of resource utilization on landscape formation throughout different historical phases. To analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin, informed by the history of water resource development and regional development, four key temporal demarcations are established: (1) 1864, marking a widespread revolt in Xinjiang; (2) 1912, coinciding with the establishment of the Republic of China; (3) 1954, denoting the founding of the XPCC; and (4) 1983, representing the completion of the first comprehensive place name census in Xinjiang. The year 1983 exhibits the highest number of TCH of water-related settlement place names, potentially attributable to the accelerated regional development initiatives undertaken by the XPCC during that period. In contrast, the number of such TCH in other historical periods is approximately half that of 1983, a difference that may be linked to limitations in water conservancy technology and a smaller agricultural immigrant population (Fig. 5).

1759-1864 The number of TCH of water-related settlement place names from 1759 to 1864, 1912 the number of TCH of water-related settlement place names in 1912, 1954 the number of TCH of water-related settlement place names in 1954, 1983 the number of TCH of water-related settlement place names in 1983.

(1) From 1759 to 1863, the early stages of land reclamation witnessed the emergence of a distinct spatial arrangement of TCH of water-related settlement place names. As depicted in Fig. 6a, these TCHs are clustered in alluvial plains exhibiting elevated groundwater discharge and proximity to the Manas River and Jingou River. This spatial pattern reflects a deliberate strategy by early settlers to minimize the risk of water scarcity, given the limited water infrastructure available at the time. This is likely correlated with the immigration of a substantial agricultural workforce attracted by the availability of irrigable land. Early agricultural immigrants in the Manas River Basin preferentially settled on alluvial plains with abundant water resources and gentle slopes, suggesting an optimization strategy that balanced access to water with ease of cultivation. Hydrological factors appear to have been a primary determinant of settlement location during this period, highlighting the importance of water for agricultural production and domestic use. The relatively flat topography also likely facilitated agricultural activities, further contributing to the observed settlement patterns.

a Spatial distribution of TCH of water-related settlement place names in 1864, b spatial distribution of TCH of water-related settlement place names in 1912, c spatial distribution of TCH of water-related settlement place names in 1954, d spatial distribution of TCH of water-related settlement place names in 1983.

(2) From 1864 to 1911, the construction of water conservancy infrastructure coincided with an expansion of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. During this period, these TCHs were primarily concentrated within the alluvial plain proximate to the Manas River, exhibiting a localized trend of clustering along the middle and lower reaches (Fig. 6b). This spatial expansion is likely attributable to improvements in water resource availability and an associated increase in immigration. The increase in agricultural immigrants led to extensive water conservancy development in Manas County, establishing it as a leader in irrigation infrastructure in Xinjiang50. This expansion of irrigation networks not only enabled the establishment of TCH of water-related settlement place names in previously inaccessible areas but also likely influenced patterns of interaction and exchange between newly arrived agricultural communities and pre-existing local populations.

(3) From 1912 to 1953, this period, characterized by ongoing irrigation development, witnessed a change in the spatial arrangement of TCH of water-related settlement place names. In contrast to the prior period’s contiguous distribution, a “dual core” pattern emerged, with clusters of TCH located along the middle and upper reaches, and the middle and lower reaches of the Manas River (Fig. 6c). The construction of irrigation projects, including the Xinshun (新顺) Canal, Qingshuihezi (清水河子) Canal, and Xinsheng (新盛) Canal, facilitated the spread of the TCH of water-related settlement place names into previously underutilized areas. Consequently, the TCH emerged in the southern mountainous areas and along the northern desert fringe. This expansion underscores the influence of regional development initiatives and demographic shifts on the formation and dissemination of TCH, demonstrating the capacity for infrastructure investment to redefine historical landscapes.

(4) From 1954 to 1983, the large-scale reclamation efforts in the Manas River Basin during this period resulted in a complex spatial pattern of the TCH of water-related settlement place names, characterized by a “three cores and multiple points” configuration (Fig. 6d). The “three cores”—representing the established settlements along the middle and upper reaches of the Manas River, the settlements along the banks of its middle and lower reaches, and the newly developed Shihezi reclamation area—likely functioned as administrative and economic centers. The “multiple points,” scattered across the alluvial plains of the Taxi River, Ningjia River, Jingou River, Danangou River, and Bayingou River, probably served as smaller agricultural outposts or resource extraction sites connected to these central cores. This distinctive spatial distribution pattern is attributable to the designation of the Manas River Basin as a key agricultural reclamation demonstration area by the XPCC during this period. The subsequent influx of agricultural immigrants, supported by the construction of sophisticated water management infrastructure (diversion, storage, distribution, and irrigation), not only enabled the colonization of previously uninhabitable zones (desert and swamp lowlands, mountainous plateaus) but also triggered new cultural dynamics. We posit that this process resulted in the creation of a distinct cultural landscape, reflected in the increased density and diversity of the TCH of water-related settlement place names, as well as the syncretism of cultural practices between newly arrived settlers and established local populations.

In summary, the long-term evolution of kernel density patterns of the TCH of water-related settlement place names indicates a clear trend of spatial expansion across the Manas River Basin over the last three centuries. This expansion is particularly evident in the middle and lower reaches of the river and the Shihezi reclamation zone, reflecting the changing spatial characteristics of this TCH. Moreover, the evolution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin over the past three centuries demonstrates the profound influence of both demographic change and technological innovation on cultural landscape formation. The continuous increase in agricultural immigration and the progressive refinement of water management techniques have led to a corresponding increase in the number and richness of these cultural heritage resources, reflecting a dynamic interplay between inherited cultural traditions and ongoing cultural exchange and syncretism between immigrants and native populations.

Factors affecting the spatial distribution and evolution of TCH of water-related settlement place names

Natural factors, such as topography, hydrology, and natural resources, are crucial natural determinants in the formation of the TCH. These factors also exert a significant influence on the spatial distribution patterns observed in place name datasets.

Altitude and river systems, to some extent, determine the construction difficulty of settlements and are also important factors affecting the dissemination of TCH within the region55. In the Manas River Basin, the elevational distribution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names is notable uneven. The majority of them (48.52%) are situated between 300–399 m in altitude intervals. And a secondary peak (28.99%) occurs between 400–499 m. The scarcity of sites outside these ranges clearly shows a pattern of altitudinal clustering (Fig. 7a).

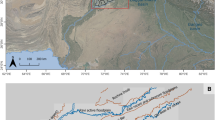

The alluvial flood plain, ranging from 270 to 399 m in elevation, is characterized by a complex network of rivers and well-developed micro-topography. This includes features like abandoned river channels, numerous gullies, and paleochannels, which form groove-shaped depressions, as well as non-dish-shaped river channels and landforms. The TCH of water-related settlement place names are a dense distribution within this area. A representative cross-section was chosen for further detailed analysis. Place names in this region are linguistically rich, predominantly featuring terms related to water, such as “He”, “Hu”, “Wan”, “Keng”, “Wa”, and “Gou”. The dominant land use type is cropland, highlighting the critical importance of water for both agricultural production and human settlement (Fig. 8).

Cross-section 1 The changes of TCH of water-related settlement place names within a radius of 1 km from the cross-section lines A–B associated with geographical feature, Cross-section 2 the changes of TCH of water-related settlement place names within a radius of 1 km from the cross-section lines C–D associated with geographical feature.

The piedmont slope plain, situated at elevations between 400 and 499 m, marks a significant hydrogeomorphic transition. Here, the shift from steep upper slopes to gentler gradients allows for groundwater to emerge, creating a phreatic overflow zone with abundant water. This hydrologically favorable environment correlates with a relatively high density of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. Cross-sectional analyses reveal a strong prevalence of hydronyms, such as “Quan”, “Hu” and “He” in the local nomenclature. The dominant land use in this zone includes both cropland and grassland (Fig. 8, Cross-section 2).

The southern mountainous terrain of the Manas River Basin, with elevations exceeding 500 m, imposes considerable environmental constraints on human settlement and agricultural activities. Its steep, deeply incised valleys, significant fluvial erosion, and extensive vegetation cover collectively restrict the distribution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. Topographic analysis of cross-sections reveals a prevalence of terms such as “Gou”, “Wan” in local place names, consistent with the predominant land use of grassland (Fig. 8, Cross-section 2).

Along the northern periphery of the desert, with the 270–299 m elevation range, a central topographic depression within early lacustrine sediments is notable, alongside a relatively high-water table. This specific hydrogeological setting appears to correlate with a sparse distribution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. Analysis of cross-sectional transects indicates a recurring presence of hydronyms like “Hu”, “Keng”, and “Wa” in the local toponymy, coexisting with a mosaic of land use patterns including barren, cropland, and grassland (Fig. 8, Cross-section 2).

Cultural and historical factors exert a stabilizing influence on the spatial patterns of place names related to water-related settlements in the Manas River Basin. These place names encapsulate the dynamic relationship between evolving social structures and the physical environment.

Related to water resource utilization

Water is a vital resource for oasis sustainability56. Given that agriculture has been the dominant economic activity in the alluvial plain of the Manas River Basin since 1759, it follows that water conservancy infrastructure, particularly that supporting agricultural irrigation, is heavily concentrated within this zone. Traditional water management practices in this region involve the artificial diversion of mountain streams through the construction of dams, gullies, and canals, thereby supplying water for domestic use, agricultural irrigation, and flood control measures. This intensive water management has resulted in this region of the Manas River Basin experiencing the most significant modifications to its natural state due to human intervention. A transect analysis of the Manas River alluvial plain, specifically within a 1 km buffer, demonstrates a notable correlation: specific toponymic terms (“Qu”, “Ku”, and “Ping”) are highly prevalent in the TCH of water-related settlement place names. They are predominantly located within the 300-499 m elevation band and are concentrated within a 0-2 km buffer of the river channel. This riparian zone is predominantly characterized by farmland, highlighting the close link between water resources, settlements, and agricultural practices (Fig. 8 and Table 2). These TCHs of water-related settlement place names provide insights into the local adaptation strategies employed to harness water resources originating in mountain rivers for the establishment of artificial irrigation networks. They serve as a linguistic testament to the evolution and spatial boundaries of anthropogenic water systems in the Manas River Basin, representing a crucial element of the basin’s hydro-social history and its transformation from a natural riverine system.

Related to regional exploitation

The observed spatiotemporal patterns in the distribution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin are closely intertwined with the interplay between environmental conditions and historical economic activities. Figure 7b illustrates that the land surrounding these toponymies is predominantly utilized for agriculture (43.79% farmland) and pastoralism (52.96% grassland). Following the Qing Dynasty’s unification of Xinjiang, the government implemented policies of military garrisoning and inland migration to facilitate land reclamation and development. Crucial to the success of these reclamation efforts was the construction of extensive water conservancy infrastructure57. Consequently, the alluvial plains, characterized by abundant water resources, emerged as core areas for the concentration of cultural heritage, as evidenced by settlement place names. Over nearly two centuries of agricultural reclamation, the spatial distribution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names within the Manas River Basin progressively expanded into increasingly marginal environments. Originally confined to the alluvial fan and plain zones of the middle and upper reaches during the Qing Dynasty, settlement patterns extended to the alluvial plain region in the middle and lower reaches during the Republic of China era, and ultimately encompassed hilly and mountainous regions, the Gobi Desert, uncultivated wastelands, and even the desert margins following 1954. The cultural heritage embedded in the TCH of water-related settlement place names within the Manas River Basin is inextricably linked to regional development. The spatial trajectory of this development, in turn, shapes the temporal and spatial transformations observed in these place names.

Related to the immigrant culture formed by population migration

The cultural heritage embedded within the place names of the Manas River Basin is significantly shaped by the processes of population migration58. The arrival of new populations has directly influenced place naming conventions, leading to the adoption of new toponyms, the adaptation of existing names, and the creation of hybrid forms that reflect the amalgamation of cultural traditions. The Qing Dynasty’s policy of incentivizing inland migration to Xinjiang, commencing in the Qianlong era, resulted in a significant demographic shift within the Manas River Basin, characterized by the influx of Han Chinese migrants. This migration event facilitated the transmission of Han cultural identity, which is demonstrably reflected in the subsequent place naming conventions adopted throughout the region.

Beginning in the Qianlong period, significant agricultural immigration into Xinjiang led to marked demographic shifts within the Manas River Basin. This influx resulted in the formation of a new agrarian-based immigrant society. The subsequent practice of naming settlements after family surnames is a widespread cultural marker among immigrant groups, especially those involved in agricultural land reclamation. Within the Manas River Basin, this custom reflects both the assertion of cultural identity and the act of transforming and marking the landscape during initial settlement. Newly established areas were often named after the pioneering family, resulting in toponyms incorporating surnames such as Yang, Tian, Ye, Nie, Wan, Hu, Yuan, and Zhang, exemplified by Wangjiaqu (王家渠) Village and Zhangjiashuimo (张家水磨) Village. The use of settlement-related suffixes like “family” and place names evoking ancestral homelands, such as Shandan and Lanzhou, further reinforces the connection between place naming and immigrant cultural heritage.

The establishment of the XPCC in 1954 led to an unprecedented peak in migration, comprising both individuals mobilized for borderland development initiatives and those voluntarily joining the XPCC. The subsequent surge in immigration following 1954 directly correlated with a marked increase in the designation of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. The genesis and subsequent evolution of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin encapsulate the dynamic processes of population migration, spatial diffusion, and cultural integration. These toponyms serve as tangible evidence of the interaction and exchange among diverse cultural groups within the region.

Discussion

Our spatial statistical analysis of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin, employing kernel density estimation and buffer zone analysis in ArcGIS, reveals how natural geographic factors and socio-cultural influences interact. This analysis objectively reflects the systematic adaptation and reconstruction of human-land relationships within a defined historical period and region. Specifically, these interactions are evident in the three key aspects.

The first is the spatial heterogeneity of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. The distribution of TCH of water-related settlement place names across the Manas River Basin is spatially heterogeneous, primarily influenced by natural factors. For nearly three centuries, TCH has been largely concentrated on the alluvial plain, with lower densities in southern mountainous areas and along the arid northern desert margin. This uneven distribution highlights human selectivity regarding the natural environment and underscores the profound understanding and adaptive strategies employed by human populations in response to the prevailing natural environment. This spatial pattern demonstrates the ecological wisdom of adapting to local conditions and fostering harmonious co-existence with nature.

The second is proximity to water resources and TCH concentration. A strong spatial correlation exists between settlement proximity to rivers and the prevalence of water-centric human practices related to production and daily life. Quantitative analysis shows that the TCH of water-related settlement place names is predominantly concentrated within a 0–2 km buffer zone from riverine systems. This spatial clustering underscores the integral role of water resources in sustaining human settlements and driving economic activities within the Manas River Basin.

The third is temporal acceleration and spatial expansion in the TCH of water-related settlement place name distribution. Initially, the number of these place names grew slowly, followed by a period of rapid increase. Simultaneously, their spatial distribution expanded from the alluvial plains into more marginal areas, such as the desert fringe and mountainous zones. A notable concentration shift occurred from the eastern bank of the Manas River to the western bank, where is Shihezi reclamation area.

Beyond these specific insights, this study significantly contributes to international TCH studies in the following ways. On the one hand, our research firmly establishes the significant and enduring influence of the natural environment on place names, particularly in resource-constrained regions. This fundamental principle enriches international discussions on the role of regional environmental attributes in shaping TCH and the reciprocal contribution of TCH to social resilience. The unique perspective offered by our case study of the TCH of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin provides comparative data for toponymic research in arid, semi-arid, and other environmentally sensitive areas globally. This confirms the environmental primacy in initial settlement and nomenclature59, aligning with findings from numerous international toponymic investigations7,9,12.

On the other hand, we introduce a comprehensive interdisciplinary methodological framework. This framework integrates spatial analysis (using ArcGIS) with historical data extracted from local chronicles and correlates toponymic datasets with both natural factors (e.g., elevation, hydrography, topography) and socio-cultural factors (e.g., population dynamics, hydraulic engineering, and economic development). This approach allows for both a visual representation of the TCH’s spatiotemporal distribution and evolution and a multifaceted analysis of its underlying determinants. It provides an interdisciplinary approach for global TCH studies, offering a more exhaustive elucidation of the historical processes shaping the TCH.

In addition, this study underscores the critical value of TCH for heritage conservation and its evolution through anthropogenic drivers. Through the systematic identification, organization, and analysis of water-related settlement place names in the Manas River Basin, this study emphasizes the profound significance of acknowledging and conserving this intangible cultural asset. TCH constitutes a crucial historical record of human-environment dynamics, especially in contexts of pronounced environmental change or accelerated anthropogenic development. Our quantitative analysis of spatial patterns reveals the emergence of human activities as the primary driver of toponymic evolution during the region’s accelerated socioeconomic development, reflecting the changing human-environment relationship. This highlights the inherent heritage value of these place names3,4,5, which are crucial for preserving traditional ecological knowledge, historical narratives, and adaptive survival strategies related to water management. In arid regions, this distinct form of TCH specifically illustrates the pivotal role of water in shaping local cultural practices, belief systems, and traditional knowledge. Preserving the TCH of water-related settlement place names is therefore a critical investment in safeguarding historical records, strengthening cultural identities, bolstering community adaptive capacity, fostering sustainable development, and ensuring the intergenerational transfer of essential knowledge. The empirical findings and methodological advancements of this research provide a robust scientific foundation for protecting and revitalizing TCH in geographically diverse regions facing similar challenges.

In the future, the following principles can guide the development of macro-level protection and development for TCH. We should conduct a comprehensive survey of place names, ensure community engagement throughout the process, and establish a robust place name database. Collaborative partnerships with universities and research institutions will further enhance the study of place-name cultural heritage, elucidating its critical role in civilizational continuity across historical periods. At the same time, we should actively promote community participation and empowerment in TCH preservation effors58, and strengthen policy and legal protection to effectively safeguard place names as cultural heritage59. Besides, we should design sustainable TCH tourism routes and integrate TCH into cultural tourism initiatives3.

Although this study advances understanding of the complex interplay between human activities and toponymic practices in arid environments, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, this study relies on data sources primarily derived from the First National Place Name Census of the People’s Republic of China (1983) and local chronicles dating from the Qing Dynasty onward. The absence of comprehensive data predating this period introduces a potential bias in the long-term analysis, particularly regarding the early formation and evolution of the TCH of water-related settlement place names. This bias may affect the interpretation of the spatial distribution and spatiotemporal dynamics of these settlements across the Manas River Basin. Secondly, this study acknowledges the limitations inherent in relying primarily on qualitative assessments to analyze the drivers of the TCH change. While historical documents offer rich contextual information, future investigations should explore the potential for developing quantifiable metrics to assess the relative influence of various factors, such as environmental change, demographic shifts, and economic development. Such quantitative analyses would provide a more rigorous and empirically grounded understanding of the dynamics shaping place name patterns.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Pearsall, D. M. Encyclopedia of Archaeology (Academic Press, 2007).

“Geography” Editorial Board. The Encyclopedia of China: Geography (The Encyclopedia of China Press, 1992).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. A toponymic cultural heritage protection evaluation method considering environmental effects in a context of cultural tourism integration. Curr. Issues Tour. 26, 1162–1182 (2022).

Liu, Y. T. & Li, Y. Q. Research, protection and development of the cultural heritage of place names from the perspective of cultural linguistics. Theory Mon.1, 90–102 (2023).

Liu, B. Q., Li, B. Y., Song, J. C. & Zhang, Q. H. Introduction to Geographical Name Cultural Heritage (China Social Publishing House, 2011).

Jin, Q. M. The Rural Settlement Geography in China (Jiangsu Science and Technology Press, 1989).

Wang, T. et al. Analysis on cultural landscape of rural “water related” place names in Pingba District of Plateau Lake. Econ. Geogr. 40, 231–239 (2020).

Csurgó, B., Horzsa, G., Kiss, M., Megyesi, B. & Szabolcsi, Z. Place naming and place making: the social construction of rural landscape. Land 12, 1528 (2023).

Liu, F. L. & Meng, K. Analysis of geomorphic environment elements and landscape features of cultural administrative place names. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 1684 (2021).

Jiao, M. & Lu, L. Spatiotemporal distribution of toponymic cultural heritage in Jiangsu Province and its historical and geographical influencing factors. Herit. Sci. 12, 377 (2024).

Li, C., Qian, Y. Y. & Li, Z. K. Identifying factors influencing the spatial distribution of minority cultural heritage in Southwest China. Herit. Sci. 12, 117 (2024).

Liu, Y. L., Liu, L., Xu, R., Yi, X. & Qiu, H. Spatial distribution of toponyms and formation mechanism in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China. Herit. Sci. 12, 171 (2024).

Fagundez, J. & Izco, J. Spatial analysis of heath toponymy in relation to present-day heathland distribution. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 30, 51–60 (2015).

Stewart, G. R. Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-naming in the United States (Random House, 1945).

Yin, H. Place names shall be included in the list of national cultural heritage protection. China Local Rec. 6, 15 (2005).

Sazhironggui. Investigation and study on the legal protection and countermeasures of cultural heritage of geographical name in China. Cult. Herit. 3, 34–41 (2023).

Ramonienė, M. Language planning and personal naming in Lithuania. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan 8, 422–436 (2007).

Assadorian, A. On the toponymy of the Iranian Azerbaijan. Adv. Anthropol. 7, 146–153 (2017).

Qian, S., Kang, M. J. & Weng, M. Toponym mapping: a case for distribution of ethnic groups and landscape features in Guangdong, China. J. Maps 12, 546–550 (2016).

Reszegi, K. Toponyms and spatial representations. Onomastica 64, 23–39 (2020).

Matthew, L., Mitchelson, Derek, H., Alderman, E. & Jeffrey, P. Branded: the economic geographies of streets named in honor of reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Soc. Sci. Q. 88, 120–145 (2007).

Creţan, R. & Philip, W. M. Popular responses to city-text changes: street naming and the politics of practicality in a post-socialist martyr city. Area 48, 92–102 (2016).

Medway, D., Warnaby, G., Gillooly, L. & Millington, S. Scalar tensions in urban toponymic inscription: the corporate (re)naming of football stadia. Urban Geogr. 40, 784–804 (2018).

McElroy, E. Data, dispossession, and Facebook: techno-imperialism and toponymy in gentrifying San Francisco. Urban Geogr. 40, 826–845 (2019).

Rose-Redwood, R., Sotoudehnia, M. & Tretter, E. “Turn your brand into a destination”: toponymic commodification and the branding of place in Dubai and Winnipeg. Urban Geogr. 40, 846–869 (2018).

Rose-Redwood, R., Vuolteenaho, J., Young, C. & Light, D. Naming rights, place branding, and the tumultuous cultural landscapes of neoliberal urbanism. Urban Geogr. 40, 747–761 (2019).

Kearns, R. A. & Lewis, N. City renaming as brand promotion: exploring neoliberal projects and community resistance in New Zealand. Urban Geogr. 40, 870–887 (2018).

Zhao, F. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristic of Biantun toponymical landscape for the evolution of Biantun culture in Yunnan, China. Sci. Rep. 11, 23791 (2021).

Liu, F. & Meng, K. Analysis of geomorphic environment elements and landscape features of cultural administrative place names. Arab J. Geosci. 14, 1684 (2021).

Ma, R. F. & Chen, J. R. The spatial pattern and influencing factors of the cultural landscape of generic place names in the Yangtze River Delta. Geogr. Res. 41, 764–776 (2022).

Ji, X. M., Cui, H. F. & Tao, Z. M. Changes in Nanjing street names from the perspective of social memory. Prog. Geogr. 38, 1692–1700 (2019).

Tang, M. L. The inventory and progress of cultural landscape study. Prog. Geogr. 19, 70–79 (2000).

Weng, Y. & Zhu, H. Urban evolution and change of aqueous toponym of riverside city: a case study of Taijiang district, Fuzhou. Trop. Geogr. 32, 141–146 + 172 (2012).

Tebes, J. Desert place-names in Numbers 33:34, Assurbanipal’s Arabian wars and the historical geography of the biblical wilderness toponymy. J. Northwest Semitic Lang. 43, 65–96 (2017).

Saparov, K., Chlachula, J. & Yeginbayeva, A. Toponymy of the ancient Sary-Arka (North-Eastern Kazakhstan). Quaest. Geogr. 37, 35–52 (2018).

Wu, Z. T., Zhang, H. J., Krause, C. M. & Cobb, N. S. Climate change and human activities: a case study in Xinjiang, China. Clim. Change 99, 457–472 (2010).

Zhang, L. Land Reclamation and Environmental Changes in the Northern Piedmont of Tianshan Mountains (1757-1949) (China Social Sciences Press, 2021).

Xu, Z. H. et al. Evaluation and simulation of the impact of land use change on ecosystem services based on a carbon flow model: a case study of the Manas River Basin of Xinjiang, China. Sci. Total Environ. 652, 117–133 (2019).

Feng, L. A Study on the Agriculture Exploitation and Ecological Environment Transition in Manasi River Basin (China Agriculture Press, 2006).

Shen, Z. Z. & Feng, L. On the agriculture in the Manasi River Valley of Xinjiang in the time of the Republic of China. Anc. Mod. Agric.3, 55–61 (2010).

Zhang, L. & Liu, J. J. Reconstruction of cropland spatial patterns of the Manas River Basin of Xinjiang in the late Qing and Republican period. Resour. Sci. 42, 1428–1437 (2020).

Mao, S. H., Li, Y. B. & Dong, H. Z. Brilliant 70 years of China Cotton: China has embarked on a development path, model and theory of cotton production with Chinese characteristics suitable for national conditions. China Cotton 46, 1–14 (2019).

Ji, Y. Urumqi Miscellaneous Poems (Zhonghua Book Company, 1985).

Liao, N. et al. Differences in and driving forces of cultivated land expansion in the Manas River Basin oasis. Xinjiang. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 29, 1008–1017 (2021).

The Place Name Committee of Manasi County. Place Name Atlas of Manasi County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Internal information) (1989).

Shawan County Committee of the Communist Party of China History Office, The Place Name Committee of Shawan County. Place Name Atlas of Shawan County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Internal information) (2008).

The Place Name Committee of Shihezi City. Place Name Atlas of Shihezi City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Internal information) (1988).

The Place Name Committee of Kelamayi City. Place Name Atlas of Kelamayi City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Internal information) (1984).

Fu, H. et al. Annotation of Western Regions (Xinjiang People’s Publishing House, 2002).

Wang, S. N. Xinjiang Atlas (Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2015).

Ma, D. Z., Huang, G. Z. & Su, F. L. Xinjiang Local Records Manuscript (Xinjiang People’s Publishing House, 2010).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2020 (1.0.0) [Data set]. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5210928 (2021).

Wang, F. H. Quantitative Method and Application Based on GIS (The Commercial Press, 2009).

Yan, D. K. Place name culture and forms of frontier migrants societies: taking the northern foot of Tianshan from the Qing dynasty to the period of the Republic of China as an example. J. Chin. Hist. Geogr. 4, 139–147 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Geospatial characterization of rural settlements and potential targets for revitalization by geoinformation technology. Sci. Rep. 12, 8399 (2022).

Zhou, G. L., He, J. K. & Chen, S. H. A Model of water resource exploitation and allocation in Xinjiang region. Sci. Agric. Sin. 5, 36–41 (1985).

Kan, Y. P. The placename landscape formed by immigration in the northern piedmont of the Tianshan Mountains in the modern times. Arid Land Geogr. 6, 869–873 (2005).

Ge, J. X. History of Immigration in China, Vol. 1 (Fuzhou People’s Press, 1997).

Alderman, D. H. Place, naming and the interpretation of cultural landscapes. in The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity (eds Graham B. & Howard P.) 195–214 (Routledge Press, 2008).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Major project of the National Social Science Fund “Research on the History of Water Resources Utilization in Northwest China” (23 & ZD255) and by Youth project of the National Social Science Fund “Research on the Mapping and Border Governance of Xinjiang in the Qing Dynasty” (19 & CZS059). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: L.Z. and S.Z.; methodology: L.Z., S.Z. and J.R.; software: S.Z.; validation: L.Z. and S.Z.; formal analysis: L.Z. and S.Z.; investigation: L.Z. and S.Z.; resources: L.Z. and S.Z.; data curation: L.Z. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation: L.Z. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing: L.Z., S.Z., and J.R.; visualization: S.Z.; supervision: L.Z., S.Z., and J.R.; project administration: L.Z.; funding acquisition: L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Zhou, S. & Ren, J. Spatiotemporal distribution of toponymic cultural heritage of water-related settlement place names in Manas River Basin. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 337 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01912-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01912-7