Abstract

Ancient stone inscriptions are vital sources of traditional knowledge and historical heritage. However, because of the unrestricted stroke writings, age-related deterioration, and variability, their digital recognition is still difficult. Modern OCR technologies are inadequate for the accurate recognition of Tamil inscriptions. A Dynamic Profiling Bound (DPB) approach is proposed for character localization, achieving a high localization rate of 98.25% across varied inscription image conditions, including noise, deterioration, and compact writing. Using these localized characters, SignaryNet, a fine-tuned deep convolutional neural network (CNN), is developed to recognize 100 classes of ancient Tamil and Grantha characters based on Unicode mappings. SignaryNet outperforms the baseline Classic-CNN, achieving 98.61% validation and 96.81% prediction accuracy versus C-CNN’s 83.33% and 84.74%. The method proves effective on benchmark datasets and supports the digital preservation of heritage inscriptions, such as those on the Brihadisvara temple walls, facilitating their storage in accessible digital archives for historical research and conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stone inscriptions, which are old artefacts inscribed on ancient temple walls, pillars, caverns, rocks, and the like, are the most reliable source of historical data since they are everlasting. The proposed work is based on stone inscriptions from South Indian temples originating in the 11th century. These stone inscriptions have been severely damaged and devastated by time and the environment, making it difficult to recognize the text. Epigraphic preservation techniques are ineffective in preserving this valuable resource, and manual skill is also needed. The development of image processing and computing technologies may be applied in this situation, allowing for the digitization and processing of the content of the stone inscriptions. An effective signary localization technique needs to be created to obtain the historical information contained in stone inscriptions. The process of segmenting the individual characters in an inscription image is known as signary localization. The recognition approach may be used for the correctly localized character as a sub-image. The localization process includes several sequential steps, including line localization for segmenting line images, character localization for segmenting individual character images, over-segment reduction, touching, and broken character localization, etc. The inscription image is noisy due to the background’s unevenness in the stone, and eroded parts cause discontinuities in strokes. Localizing the characters is the greatest obstacle. An over-segmentation issue is caused by the inscriptions’ unrestricted writing style as well as intricate patterns like clustered, stacked (compound characters that integrate two or three characters into one character), overlapped writings, and compound characters. Writings that are skewed and have uneven legibility make localization more difficult. Additionally, the slanted writing in rural scripts makes line localization difficult. Existing methods are ineffective for these images of stone inscription scripts. To address the issues raised above, an improvised technique must be developed. The difficulty of recognizing signary in present systems derives from the need to comprehend characters.

Images of the characters from several inscriptions in the Great Chola Temple area mainly Brihadisvara temple (Big Temple) revealing the King’s culture, passion and history in stone inscriptions as written in an article by Subramanian1, were gathered for identification. Rajarajesvaram, also known as Brihadisvara Temple, is a heritage monument situated on the south bank of the Cauvery River, not far from Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, and India, which uses the architectural style of Chola. As one of the “Great Living Chola Temples” on the UNESCO World Heritage Convention list, the temple was constructed between earlier 11th century periods by Rajaraja I, the Chola king2. The description about inscriptions of Rajaraja Chola I is detailed in ref. 3. The monument’s lighting is intended to draw attention to the sculptural forms that embellish every nook and cranny of the temple, in addition to the stone’s natural hue. Inscriptions can be found on the pillars, walls, and entrance of the central shrine. The temple walls have numerous inscriptions in Tamil that give a brief history of the king who gave his approval. Most of them talk about presents given to the temple or its staff, and occasionally they even mention city dwellers. Digital inscription acquisition saves epigraphers time since the technology digitally enhances raw stone inscriptions to provide character clarity. Since the writings on the stone image are different from those in contemporary Tamil, reading its contents is necessary. It is also difficult to digitally recognize because of the broken and damaged inscriptions.

The proposed Dynamic Profiling Bound (DPB) approach for signary localization is an exceptional segmentation or localization method for localized images from the inscriptions. This approach utilizes trace profiling to locate lines, employs a dynamic bounding box algorithm based on profile data, and applies dynamic vertical trace profiling to identify signary. Without omitting or misaligning the constituents of the character strokes in the sequence of script continuation, the suggested model localizes the character images successively. On the inscription images, state-of-the-art methods of segmentation are also used, and performance is evaluated in terms of Signary Localization Rate (SLR) or segmentation rate to contrast with the proposed. By including morphological erosion and dilation, concerns like over- and under-segmentation were also addressed, and the outcome was improved localization. The technique also addresses other bounded box issues like overlapping, space-constrained, and deteriorating characters. After that, the model is developed, and single-character images are trained using a deep neural network, such as a Classic Convolutional Neural Network (C-CNN). Then it is refined for the inscription signary recognition by adding, dropping, and hyper-parameter fine-tuning the model known as a novel SignaryNet, and then the training is done. The modern Tamil version of the characters is returned when the signary is identified by mapping to the appropriate Unicode.

Some of the similar works in the Tamil inscriptions were addressed with the issues and challenges faced in them. The Ashokan Brahmi Character dataset from Indoskript manuscripts from the Brahmi and Kharosthi database of 3500 images was used for OCR using CNN for Ashokan Brahmi inscriptions. As demonstrated in ref. 4, data augmentation was performed on up to 227,000 images. For inscription pre-processing, Otsu thresholding, median blur, nonlinear digital filtering, and adaptive thresholding are used. Although projection profiling techniques like the vertical and horizontal projection profiles are used, the results are not thoroughly examined. The problem of not distinguishing between words and characters is still present. An OCR method that used image recognition-based classification for old Tamil inscriptions5 made use of Tesseract text-to-speech for written Tamil literature, Otsu for binarization, and 2D CNN transfer learning and data augmentation. The work claims that there were difficulties with the segmentation process, where errors led to incorrect recognition. Additionally, during the augmentation phase, book scanning and pre-processing failed to segment effectively. The accuracy of segmentation differed among samples. 91% comes from printed Tamil literature, 68% from text-to-voice, and 70% from handwritten modern Tamil. CNN image slicer and an OCR scanner are used to scan old Tamil script. Thirty samples are examined. According to the work, there is no solution for the sparse dataset. The scripts on the inscription are irregular, lack equal spacing, and have an uneven surface, making it difficult and incorrect to identify ancient Tamil characters. For digital erosion minimization, high resolution is required, and its accuracy rate is 77.7%.

An image-based character recognition documentation system6 was developed that employs Tesseract and modern ICR and OCR methods to interpret temple inscriptions in ancient Tamil. The dataset from the previous century is limited, has little information, and has no spaces between words. 400 images are scanned using the powdered limestone on the temple walls. Bilateral filtering, erosion, histogram equalization, median blur, and Otsu thresholding are all employed. Each unique character inside the digital inscriptions has its bounding box adjusted for correctness, which includes physical intervention for misaligned and unclear characters. CNN is utilized when there is a paucity of data and incorrect output categorization. There are only ten tested photos, and they yield 80.8%. The approach highlights morphological characters, multi-character compounds, single characters, and curves over neighbouring characters in addition to segmentation problems. The proposed work resolves the problems raised by the existing works.

Character segmentation has been the subject of extensive research, and this work is still ongoing. They were segmented using contour-based convex hull bounding box segmentation7, which uses polygon lines to outline the region where the characters’ curves were detected before drawing the bounding box. The Tamil Palm Leaf Inscription dataset is used, and the characters are recognized using GLCM features with a recognition accuracy of 85.3%. Due to the prevalence of curves in the Tamil language, it overcomes the limitations of edge detection approaches; nonetheless, it is ineffective in precisely segmenting the connected components.

For Indian document images, a multilingual character segmentation and recognition scheme is suggested8. In this study, the overlapping and joined characters are segmented using projection profiles and graph distance theory, and a preliminary segmentation path is constructed using a Gaussian low pass filter profile with smoothening. Proprietary Devanagari, CPAR, CVLSD, Proprietary Latin, and Chars74k datasets are used. The K-nearest neighbour (KNN) classifier is used, which gives an accuracy of 87.42%, and the SVM classifier is used to assess these data overall for high accuracy. Although this method at least avoids over-segmentation in cases where ligatures and connections between, inside, and some connected characters are present, it is effective only for document images with strong foreground–background discriminating.

For the character recognition system for Tulu palm leaf manuscripts studied as in ref. 9, a region of interest (ROI) selection based on connected component analysis (CCA) is raised along with Deep CNN with an accuracy of 88.07%. This suggestion requires a manual implementation to choose the stacked characters. Using a convolutional neural network on Android is suggested to recognize handwritten characters as in ref. 10. This work identifies the connected components before the labelled elements are segmented for the cursively written words using the vertical projection approach. Additional small disjoint connection steps include vertical cursive word projection, over-segment elimination, and small disjoint connection steps. This work uses 1000 random words with 85.74% recognition accuracy. However, the approach would not be appropriate for the inscription images since it does not solve the overlapping character segmentation for strokes and slanted line segmentation.

The HP India 2013 laboratory dataset, which consists of 100 Tamil characters, is used to suggest a structure representation-based method for recognizing handwritten Tamil characters11. Normalization, skeletonization, noise reduction, and binarization are carried out. Features are extracted and predicted using the PM-Quad tree (82.4%) for locational analysis, the z-ordering approach (88.3%) for shape ordering, and stripping tree-based sequential reconstruction for forms. SVM provides an accuracy of 90.3%. Complex structures, curve variation, and shape similarity are discussed. There is no mention of other characters. There is no use of deep learning or character extraction techniques. It is only appropriate for handwritten characters and only addresses distinct vowels and consonants that are not vowel consonant characters.

High-speed vehicle number recognition and detection using the bound box approach12 is proposed for edge processing both vertically and horizontally based on the bound box and detecting the license plate detection region. The car images are captured and pre-processed, and the images of the big blobs are clipped. The license plate region is located using a Sobel edge detector operator, median filtering, dilation, erosion, and flood fill. Pixels corresponding to images are found by comparing the bound box with predetermined templates of the alphanumeric database, which contains a numeric index for all sub-images using correlation coefficients, mapping with box values, and characters compared with letter pixel values. This offers a 93% accuracy rate and eliminates unnecessary related objects.

Devanagari character segmentation is carried out using an approach that combines polynomial-based thresholding with adaptive thresholding13. The polynomial thresholding line fitting delivers the minimum distance using the least-square distance from the original line, and it gives the minimum value with its index when the input block size fluctuates. The smaller dataset is used with Devanagari shades of grey from the ISI collection. Nevertheless, there was no discussion of how to separate structures that overlap, slant, or are uncontrolled.

In the skewed line segmentation technique for cursive script OCR, widely studied as in ref. 14, for line segmentation, noiseless, skew-free character images are used. It makes use of a method for detecting headers, which are the first few characters of a line. A ligature segmentation technique is used to precisely divide the ligatures into smaller ones and arrange them in sequential order. The Urdu dataset, which is very small that has 687 handwritten character images and 495 printed images. Out of 687 lines, 674 lines are detected correctly, with a segmentation accuracy of 96%. The suggested strategy is successful for printed text but has not been investigated for inscription images. The inability to effectively split dots and diacritics is a drawback to this effort.

Using the HP-Lab-India datasets from 2017 and 2013, which comprise 125 characters and two distinct handwritten manuscripts, gathered from Tamil Nadu residents, a statistical algorithmic approach for Tamil handwritten character detection is provided15. The characters are separated into nine equal zones for feature extraction (upper, middle, and lower zones), and structural features are extracted using a directional algorithmic technique. 16 locational features, including 153 potential features, 170 forms, and four quads, make up the zone. Deep learning and character extraction techniques are not applied and are only appropriate for handwritten characters.

Text lines in Kannada manuscripts written by hand have been segmented using a segmentation method suggested in ref. 16. Additionally, it utilized horizontal projection profiling for the computation of local maxima, constrained seam carving, seam computation, coordinate values, and ROI extraction. With Vijayanagara dynasty manuscripts, this method has a line segmentation accuracy of 81.89%, and with Wadiyar dynasty manuscripts, it has an accuracy of 87% with KNN and 92% with support vector machine (SVM). The Horver method of touching character segmentation was proposed17. The Tamil Heritage Foundation (THF) provided the manuscripts on palm leaves for the authors to use. To determine a character’s weight, the Horver technique with DLA recognizes touching characters with horizontal touching, vertical touching, and multi-touching characters with a touching point. It has a 90.63% accuracy rate and a 92.43% recognition rate. However, this can be done after using proper segmentation methods for extracting characters.

Character segmentation, feature extraction, block-by-block transformation, Niblack, morph operations, and 2D Log-Gabor feature extraction were used to recognize Malayalam characters18. Finding and recognizing the local maxima and minima of the histogram’s peaks and dilation using disk and line structuring elements, area opening, bound box position, and horizontal and vertical projections with connected component analysis are all part of the segmentation technique. In any case, the division of lines and characters is not detailed. For feature extraction, rotation-invariant LBP is employed. Recall is 90.95%, precision is 92.86%, and segmentation F1 score is 93.05%. For a 95.45% recognition rate, Staked ResNet CNN and LSTM are utilized. These techniques do not work with inscription images.

Manuscript character recognition19 for electronic Beowulf old English manuscript photos with 404 characters and resampling 1–3 of the manuscript dataset using an Image Data generator. Additionally, the MNIST dataset has been employed. Numerous models, including CNN, SVM, KNN, decision trees, Random Forest, XG Boost, VGG16, Mobile Net, and ResNet50, have been examined in this work. With 22 classes and 352 characters for training and testing, the accuracy for resampling 1 (a tiny dataset) is 88.67% and resampling 2 is 90.91%.

Character recognition in Tamil using CNN has a test accuracy of 99.39% training accuracy, 89% validation accuracy, and 97.7% test accuracy after dropouts, despite the model exhibiting overfitting. CNN was proposed20 using handwritten Tamil character recognition (HTCR) for the dataset HP Labs India (hpl-tamil-iso-char) that isolated characters of 156 classes and 82,929 images. It is proposed to use CNN21 for Kannada handwriting character identification for handwritten vowels, consonants, and numerals. The dataset of character 74,000 contains 50 classes, including 16 vowels, 34 consonants, and numbers from 0 to 9. Since each class had 25 images, augmentation was used. Each class had 350 images. Following transfer learning, training correctness is 91.9% and validation correctness is 93.06%, with training correctness being 89% and validation correctness being 86.92%. The dataset is small, and no segmentation is done in this work.

Using a Chinese scene text dataset, a multi-segmentation network-based street view text spotting at the character level for smarter autonomous driving22 was presented. Chinese store sign pictures from the ICDAR 2013, ICDAR 2015, MSRA TD 500, SCUT, RCTW, ReCTS, and Shopsign databases were used. Point of Interest and multi-segmentation network for character-level scene text detection (MSTD) and ResNet attention mechanism are used for character-level and line-level instance localization and scene text detection for Chinese scene text datasets. The overall F score of the datasets is 92% and the correctness is 92.98%, SCUT is 92.4%, CTW is 95%, RCTW is 92.3%, and ReCTS is 94.9%. For the line-level F score, ICDAR13 is 90%, ICDAR15 is 84%, MSRA is 84%, and Shop sign is 70.1%. The overall accuracy of character recognition is 92.53%.

Using ROI detection and a comprehensive learning system, characters from variable-length license plates that surpass fixed-length license plates are recognized and segmented23. Using the COCO dataset from GitHub, which consists of 1913 images for training and 287 images for validation, a transfer learning technique based on Faster RCNN with Inception V2 is applied to Macau license plates. Utilized were region proposal network (RPN), ROI pooling, template matching and position predicting (TMPP), and cross class removal of character (CCRC). The accuracy and recognition rate for segmentation projection profiles, MSER, CCA, ROI, and ROI + CCRC + TMPP are 99.68% and 99.19%, respectively. The technique is not appropriate for unconstrained writing in inscription images in an unrestricted manner, but it yields good accuracy in similar characteristic license plates.

The typical pre-processing steps of noise reduction, normalization, thinning, and bounding box extraction are followed by feature extraction techniques like chain codes, gradient angles, curve estimation, profile histogram, and stroke estimation in this review work on handwritten Hindi character recognition24 using document analysis and recognition (DAR). Character, word, and curved text recognition; page segmentation; Devanagari script identification; graphical analysis of signatures, diagrams, flowcharts, and tables; and other elements are all part of DAR’s textual analysis. SVM and ensemble are used for classification. Although the segmentation approaches are not described in detail, this study provides an overview of feature extraction strategies. To segment the printed Chinese characters as in ref. 25 raises the character recognition rate to 96% and the segmentation accuracy of printed characters to 90.6%. The character is segmented and interpolated using a multi-threshold segmentation method with vertical projection. There’s also the maximum backtracking method. There were 6423 Chinese characters used. The technique works with printed characters; it is not appropriate for characters used in inscriptions.

The iterative split analysis technique26 is suggested for Telugu handwritten characters and words from application form documents to segment touching and overlapping characters at the block level in Telugu printed and handwritten documents. Both horizontal and vertical projection profiles are used to convert lines into words and sentences into characters. Then, employing correlation analysis between segmented blocks and invalid character blocks that contain touching and overlapping characters, we come to valid character blocks. In total, there were 55 symbols, 36 consonants, and 16 vowels. With an accuracy of 91.17%, the iterative split analysis technique is employed in conjunction with bounding boxes and linked component analysis. Morphological operations and projection profiles (MOPP) yield 58.09%, multiple projection profiles (MPP) yield 78.26%, and recursive cut approach analysis yields 80.08%. Convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling strategy that uses 25%, 20%, 15%, and 10% as sampling percentages and divides them into different samples across several rounds. The collection includes English and Telugu handwritten characters. For 215 lines, accuracy is 85.37% with a 25% sampling, 87.91% with a 20% sampling, 91.45% with a 15% sampling, and 95.37% with a 10% sampling. Only touching and overlapping at the word level are handled by this method, which works well for handwritten or printed materials but is slower for splitting wider blocks. The algorithm is incredibly slow and takes a long time to run.

A survey on the recognition of handwritten characters in English is conducted using datasets from the banking and healthcare industries27. Following line, word, and character segmentation, projection histogram, zoning, crossing DFT, DCT, and DWT are used to extract statistical and structural characteristics. SVM and HMM are then utilized for HCR classification. There is little vocabulary and inadequate segmentation because it is highly complex and not detailed. It is suggested to use an over-segmentation technique to recognize handwritten mathematical expressions by extracting their strokes from bitmap images28. Topological sort and recursive projection are used to standardize the stroke order. A competition on recognition of online handwritten mathematical expression (CROHME) 2019 is the dataset that was used. Noise reduction, stroke direction recognition, stroke order normalization, stroke tracing, and double-traced stroke restoration were all carried out. The results show an accuracy of 58.22%, 65.65%, and 65.22% for CROHME14, 16, and 19 datasets. This is inappropriate for the character strokes used in the inscription.

The braille character segmentation for heavily dotted braille image environments29 is suggested. Two-stage braille recognition is available. The first is a Gaussian diffusion-based braille dot identification system, and the second uses post-processing algorithms to create a braille grid to identify a braille character. Convex dots in braille images produce Gaussian heat maps, and 114 images from the public braille dataset are used to detect convex dots. A total of 88 images were there. Probabilistic diffusion process-based optical braille recognition (OBR) with UNet and BddNet, virtual braille grid creation, braille dot range detection with linked component analysis, and braille dot clustering based on horizontal and vertical distances. The F1 scores are 98.96% and 98.57% for braille dot detection and 99.56% and 99.78% for braille character recognition. The overall summary indicating the works, languages, techniques used, and their shortfalls is shown in Table 1.

Some of the benchmark datasets are also studied, and some are used in the experiments. A detailed examination of relevant benchmark works is presented. Using CNN and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, the benchmark datasets were used to identify the script in scene text images, as suggested in ref. 30. The standard dataset CVSI-201531 is used to evaluate the document analysis community. There are written images as well as video images from the news and sports. It is based on CNN and provides data in several other languages, including Arabic, Bengali, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Oriya, Punjabi, Tamil, and Telugu. It also boasts 97.25% accuracy. Each one contains 50 sample test images that were tested and taken for Tamil. The dataset SIW-13, with 16,291 multiscript texts, is used to gather the images. The model is based on CNN and has a correctness of 94.10%. It includes thirteen language scripts. The implementation is also visible in the GitHub repositories created32. The collection consists of multiscript handwritten documents, lines written in several scripts with 276 Tamil-language images each, printed lines with 301 Tamil-language images each, and multiscript printed sentences with 2118 Tamil-language images each.

The benchmark dataset for image-based text recognition is the ICDAR-2017 dataset33. For the Tamil language, there are 68,613-word images, 1255-line images were utilized for training, and 300-line images were used for testing, yielding an accuracy of 87.30%. Scene text images are processed using the multi-language end-to-end (MLe2e) dataset. 1178-line images were used for training and 643 for testing in Tamil, yielding an accuracy of 90.23%. More than 12,000 photos of Chinese scenery, street views, posters, menus, and screenshots may be found in RCTW-17, the work in ref. 34.

The MSRATD50 benchmark dataset, which contains 3000 images of text in both English and Chinese and scores 95.22%, is utilized for scene text recognition35. For segmentation, a contour-based approach is used; feeding CNN input images with the ordered features of contoured images done as in ref. 36. In addition to using CVSI2015, which has pre-segmented texts from various video sources and scene texts, SIW-13—which consists of 13 types of script languages and 16,291 images, was also used for scene text script identification. Of the SIW-13’s 16,291 images, 6500 were used for training and 500 for testing in each language. This results in an accuracy of 87.74%.

The benchmark datasets for English scene text identification and recognition of street view text recognition are included as in ref. 37, such as MSRA-TD500, which has Chinese scripts, RCTW, which has English and Chinese scene texts, and ICDAR 2003, 2015 image datasets, which provide 78.3% accuracy. ICDAR2019 provides 83.3% accuracy for multilingual scene text with 2000 images in each language and texts in 9 different languages.

Ancient Tamil Script Recognition designed as in ref. 38, has attempted to recognize stone inscriptions using a CNN deep neural network with a pre-trained VGG19 model utilizing 61 Tanjore Tamil inscription scripts and 882 segmented characters, which is a relatively tiny dataset. For character segmentation in this study, which features poorly segmented characters, the standard bound box technique was also applied. Tamil character categorization39 yields an accuracy of 95.15% and includes 2009 samples and 3k Tamil vowel characters, each with 300 images. Only vowels and handwritten characters are used in this.

Despite the extensive research in character segmentation and recognition, several gaps remain in the existing methodologies, especially for unconstrained palaeography languages and inscription scripts. For unclear and irregular background images, such as images of stone inscriptions, several existing techniques cannot be employed. Many of the reviewed techniques also rely on small, specific datasets or require manual interventions, limiting their scalability. However, many have trouble with characters that overlap, touch, or curve, common in languages like Tamil, Kannada, and Tulu. The problem of segmenting overlapping, slanted, and unconstrained structures has not yet been solved. The methods previously in use could not handle characters with discontinuity, multiple boundaries for a single character, and under-segmented and bounding noise strokes. Many segmentation methods have been used, including contour-based convex hull, projection profiles, connected component analysis (CCA), and deep learning models. Furthermore, the approaches are often unsuitable for inscriptions, which contain highly distorted, noisy, and poorly segmented characters, making accurate segmentation and recognition challenging. Only in document images with notable foreground/background contrasts do explicit and implicit segmentations perform better; they can only be used effectively for printed text. Additionally, the use of deep learning methods for complex, historical scripts like stone inscriptions remains underexplored, especially when compared to more standardized handwritten or printed document datasets. In some cases, the thinning method fails to accurately segment characters. Where ligatures and connections between, within, and some linked characters exist and are not addressed by existing approaches, over-segmentation (more than one character constrained in a single bound) occurs. There is a need for better handling of intricate script features and variations in stroke widths, which are common in inscriptions, as well as techniques that can work effectively on degraded, real-world script images. Addressing these challenges could significantly enhance the accuracy and applicability of character segmentation systems in preserving and recognizing historical scripts. These problems are resolved by the proposed DPB signary localization methodology. Despite significant progress in character recognition, existing OCR methods still face challenges in accurately recognizing characters from ancient inscriptions. The scarcity and imbalance of datasets for scripts like Ashokan Brahmi and old Tamil limit the effectiveness of deep learning models in achieving high generalization and robustness, especially for low-resource scripts and languages. These are addressed by the SignaryNet model.

Methods

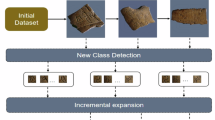

Digital acquisition of inscription images is captured using a high-quality imaging camera. These camera-captured images are post-processed, adjusted, resized, and sequentially numbered to identify script continuity. Digital image enhancement is implemented where a variety of techniques for digitally processing images include smoothing the image first and then using the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) to remove Gaussian noise. Smoothing and binarization techniques included grayscale conversion, Sauvola thresholding, and non-local means (NLM) de-noising. A novel strategy has been proposed for signary localization to address the problems with the existing localization techniques. The claimed Dynamic Profiling Bound (DPB) technique entails tracing the bound box enclosing each line-localized image while also retrieving the bound box pixel positions. Morphological operations are required for the better enhancement of broken or eroded character strokes for better recognition. Morphological thinning, thresholding, blurring, erosion, and dilation are applied to the localized line images to solve the under- and over-segmentation issues. The character width is calculated from the maximum of the pixel position points at the bound box edge, referential coordinates of an outlined box enclosing a character. The vertical projection profiling is projected based on the character width. The dynamic vertical projection profile approach performs vertical signary localization by modifying the hyperparameters. As in the line image, the signary are localized continuously. The localized characters are fed to the Classic Convolutional Neural Network (C-CNN), a deep neural model for signary recognition, which is tested and trained to predict the character sequence. To improve the performance of recognition, the neural network is designed with specifications such as adding layers, normalization, and learning parameters that are tuned for recognizing the signary of the inscriptions known as SignaryNet, and then the characters are trained. A dataset containing the character sequence and its matching Unicode is defined, and the model is optimized to estimate the precise character sequence. These recognized characters are transliterated and validated using the book South Indian Inscriptions Volume II, written by Hultzsch E.40, which is the ground truth and the inscription heritage content is digitally preserved in a digital archive. The overall flow with outcomes is shown in Fig. 1a, and Enhancement, signary localization and signary recognition in a step-by-step manner for a sample line localized image is given in Fig. 1b.

Dataset description

Images of Tamil stone inscriptions discovered on temple walls and pillars serve as the dataset for this experiment. According to Indian epigraphic statistics, the 11th century saw an abundance of stone inscriptions, many of which were found in the Great Chola temples that are now protected by UNESCO. The archaeology field has amassed a collection of these inscriptions’ remnants on special A3-sized paper called “Estampages,” still being preserved conservatively. However, a visit to the Tanjore Brihadisvara Temple must be authorized by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to take photographs digitally. With the permission and approval of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), a visit to the Tanjore Brihadisvara Temple was made to capture the images digitally. High-definition camera Canon EOS 80D with EF-S 18-135, with a lighting kit Elinchrom FXR 400 Kit Light, Kodak T210 150 cm Three Way Pan Movement, tripod for camera, and UV protection lens filter—67 mm was used to acquire the stone inscription photographs that are currently available from the area. PNG files are used to store the images since they are more accurate when training neural networks. The dataset used for this research and experimentation contains 1216 script images of 24 GB. Images from the camera would have a maximum resolution of 6000 × 3800 and a 25 MB file size. The images have been normalized to have a maximum size of 1 MB and a dimension of 1500 × 800. The images are then pre-processed using several image processing techniques to improve the quality and obtain a greater rate of localization and recognition. Each image has a maximum size of 1500 × 100 and is line-localized. 50 × 100 pixels make up each localized character image. Each script image has 90–160 characters, at most. For implementation, 18,924 distinct character images have been localized. Nine Tamil vowels, 71 Tamil consonants, five Sanskrit characters, and fifteen Grantha mixed Malayalam, Sinhalese and Brahmi characters are among the 100 classes of ancient Tamil characters that are categorized. There are 1000 images in each class. As a result, 100,000 character images are collected. Further, each character image is normalized to 64 × 64 dimensions. On average, 20% for validation, 80% for training and finally 10% of the entire character’s image data (i.e.), real-time data is used for testing in random. The dispersion of data for the process experiment is provided in Table 2.

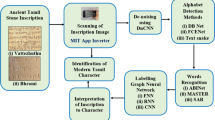

The camera acquired raw inscription images, which were then annotated by the placements of the temple’s central shrine (such as north, west, south, and east), as well as the entrance and pillars. Based on the continuation of the script’s sequence, line images are indexed. The character image dataset is labelled separately with the letter that each character in the dataset corresponds to. The character images are grouped from classes 0 to 99. The evolution of characters that are in the inscription script at different centuries and different periods of the king’s reign from the Pallava, Chola, etc., and the palaeography are given in Fig. 2. It is taken from the CILS library of the Indian Scripts Gallery, Grantha Tamil from http://library.ciil.org/Sites/Photography/GranthaTamil.html.

Digitally acquisitioned enhancement

The inscriptions are digitally acquired using a high-resolution camera during data collection with prior permission from the ASI, and the post-processing of the captured inscription images is executed before digital enhancement. Discrete wavelet transforms are used in medical image compression applications, such as ref. 41, since maintaining medical information takes up a lot of space. It is also used for MRI pictures. After wavelets are discretely sampled, the image is put through a succession of filters of low-pass and high-pass kernels to preserve components. In the same way, the images of stone inscriptions taken by the camera are wavelet decomposed. This approach produces two signals, approximation and details, from the separation of the high-frequency and low-frequency components of the image using a high-pass filter and a low-pass filter. The image is then divided into four quarter-size images using a 2D discrete wavelet transform. Discrete wavelet transform coefficients are used in wavelet-based denoising to take Gaussian noise out of the images. Image pixels can be converted into wavelets using the Mallat Wavelet Transform technique. The functions f (x) and Ψj,k(x) relate to the discrete variable x = 0,1,2,…, M−1 as given in Eq. (1). Typically, we choose to let j = 0 and set M to be a power of two, or M = 2j

The additive Gaussian noise has an impact on the wavelet transform coefficients. Most noise in the sample is contained in the wavelet detailed components. But the image also features sharp contrasts and important details. Therefore, thresholding is used for these coefficients to filter the wavelet coefficients from the detail sub-bands, and the original image is rebuilt using these changed coefficients. To improve the spatial and spectral localization of image generation, a wavelet de-noising technique42 that incorporates wavelet transform of sparsity, multi-resolution analysis, structure, and adaptability to unsupervised learning models is used. Without losing any information, the parts can be put together to create the original. Results include 2D DWT generalization, highly accurate reconstruction, and efficient noise reduction. The wavelet thresholding technique de-noises the wavelet coefficients, and then the inverse DWT is used to modify the coefficients to provide a de-noised image with improved performance. When using soft thresholding, the coefficients whose magnitude is below the threshold are set to zero, and the nonzero coefficients are subsequently shrunk towards zero. Soft thresholding can smooth the image out. The next step is NLM de-noising. The weight of each pixel’s mean value according to how similar it is to the target pixel is filtered by Non-local means. Consider a pixel and its immediate surroundings as a window of pixels in this method, and search for comparable windows of pixels in the images. The mean of a category of pixels with comparable characteristics is then determined. Let p and q be two locations inside an image, and let Ω be the image’s area. If the weighting function is denoted by f (p, q), the integral is calculated, and the filtered value of the image at point p is represented by uf (p) and the unfiltered value by vuf(q). Normalizing factor C(p) as given in Eq. (2). In continuous analysis, the image is mapped on to a rectangular region, say \(\varOmega =\left[0,H\right]\times \left[0,W\right],\) (height × width), and in a digital image of size H × W means, \({q}_{x}=[0,W]\), and \({q}_{y}=[0,H]\).

The primary feature that makes NLM robust is that it takes into account both the geometric layout of an entire neighbourhood and the grey level in a single pixel. Before two-toning, the de-noised image must be transformed to monochrome. Grey levels typically vary between 0 and 255. Each pixel in this image merely conveys information about intensity. Sauvola thresholding43 employs the average and variability within a local area to set a unique threshold for each pixel. Even with large differences in the background, poorly illuminated papers, irregular illuminations, document degradations, and uneven lighting circumstances, it removes the problem of background noise. It works well with document images that have background non-text pixels with a grey value of 255 and foreground text pixels with a grey value close to 0. By utilizing Sauvola binarization, the Sauvola thresholding function essentially produces a two-tone image. It is an improved form of a Niblack technique that, when compared to Otsu, produces excellent results in a variety of lighting situations and against dark backgrounds. Sauvola thresholding is the method that works well in this situation since stone inscriptions are photographed in a variety of lighting situations. The mean m(x, y) and standard deviation s(x, y) of the pixel intensities in a w × w window surrounded by the pixel (x,y) are used to calculate the threshold t(x, y) in Sauvola’s binarization approach, where R is the pre-set image grey-level value and k is a control factor in the interval [0.2, 0.5] as given in Eq. (3). Figure 3 shows the raw inscription image and the enhanced image.

Line localization

For this analysis, assume that each enhanced image has a different number of engraved or carved lines (r), with every character in a line having a different height and width. Let us start with the enhanced image E. The character images in each line also vary in size because of the free-form nature of the inscriptions and the unstructured writing style. Localization is required for 145-character images, of which r is 8 (i.e., 8 carved line writings) in the sample image shown in Fig. 3. First, the horizontal projection profiling approach is applied to the enhanced image E to localize the lines from the script image. The horizontal lines are projected, and E is divided into segments of lines with length x and width y. Based on the varied lengths of the characters’ strokes, the y value may be modified and localized correspondingly. The projection lines needed for image E are (r−1) lines, which correspond to (8−1), or 7 lines when r equals 8. The horizontal line profiled image is given in Fig. 4a. Identifying the horizontal kernel of each line is used to segment or localize each line, as in Fig. 4b, where a line-localized image is obtained. Iteratively extracting the image’s row-wise lines using morphological techniques enables the detection of the horizontal kernels. The alpha and beta weighting factors are 0.5 and 1−alpha for iterations i equals 3, respectively.

Dynamic Profiling Bound (DPB) technique

Applying the existing bounded box to script images with adequate line spacing, character spacing between characters, and continuous unbroken strokes will result in a clear bounding, but images with irregular spacing, broken strokes, clustered, overlapped, and staked writing styles do not properly bound the characters, which hurts the localization rate. The Dynamic Profiling Pound (DPB) technique is proposed as a solution to these problems. DPB is applied to the line-localized image \({L}_{i}\). For each obtained box, it entails extracting the bounded box coordinates. Gaussian blur, canny edge detection, dilation, and erosion are first used, and then the contours are found and sorted to determine the bound box tracing and the extraction of coordinates.

In Eq. (4), Gaussian blur \({G}_{i}\) is represented by function \(G\left(x,y\right)\), where x and y are the distances from the origin in the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, and are the standard deviations of the Gaussian distribution. Then, the image is processed using a filter in both the horizontal axes and vertical axes to obtain the first derivative in both the horizontal axes (\({G}_{x}\)) and the vertical axes (\({G}_{y}\)), which may be used to determine the edge gradient \({{\rm{E}}{\rm{G}}}_{i}\) and direction for each pixel.

Finding the gradient’s magnitude is specified by Eq. (5). If it is true, it utilizes the more precise equation given above; otherwise, it uses Eq. (6).

Further, it is followed by numpy min and max computation of the traced points represented as min(diff) and max(diff). The coordinates are returned as ordered coordinates for detecting edges. The contours are arranged in order from left to right. As box point is computed as given in Eq. (7), if the contour area \({\rm{Ca}}\) is below the box point area \({B}_{\min }\) then it is ignored. \({B}_{\min }\) can be assumed at least to the value of 100. Only those having large sufficient contours are taken.

As a result, the bound box coordinates \({B}_{i}\), along with the bound box image \({{\rm{B}}{\rm{P}}}_{i}\) is obtained. The coordinate values of a box are displayed. The bound box image \({{\rm{B}}{\rm{P}}}_{i}\) is shown in Fig. 4c. The dynamic profiling bound technique is described in Algorithm 1 as in Fig. 5. In Algorithm 1, the axispts are the point values that are traced during contouring over the strokes. The difference is calculated between the axispts and pts assigned to zero and the values are stored in diff. The box coordinate values as an array of values represented as Bi will be the minimum and maximum values of s and diff. Profiling Bound box traced image \({{\rm{B}}{\rm{P}}}_{i}\) is obtained.

Vertical projection and signary localization

After pulling the bound box edge coordinates \({B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) for each character, bound points of a character (x4, y4), (x3, y3), (x2, y2), and (x1, y1) are acquired as these points are in a clockwise direction, and likewise for all bound boxes the equivalent points are acquired. The character width is computed for each box, such as the distance between (x1, y1) and (x4, y4) or between (x2, y2) and (x3, y3). The distances are compared, and the maximum distance is taken as character width. The distance is found initially by applying Euclidean distance as follows in Eq. (8). Here, d denotes the Euclidean distance and x1, y1, x4, y4 are the Euclidean vectors.

It is followed by maximum coordinate value calculation, which is the greatest value of the x point values may be x3 or x4. For each box, the maximum point value \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}}\) is computed. With the increment offset value b, which is 1 by default, the \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}}\) value is incremented to avoid projection over edge strokes of a character, as in Eq. (9).

The number of max coordinate values identified will be equal to the total number of characters in the line image. Hence, the number of lines projected \({\rm{N}}{\rm{u}}{\rm{m}}{\rm{b}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{r}}\,{\rm{o}}{\rm{f}}\,{L}_{p}\) will be one less than the number of \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}}\) values computed as in Eq. (10).

The vertical projection lines denoted by \({L}_{{\rm{p}}}\) are projected at each \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}}\) value over the line image, where \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}}\) consists of points from \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}1}\)…………….. \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{n}}}\), where n is the number of maximum point values, and \({{\rm{L}}}_{{\rm{p}}}\) consists of \({L}_{{\rm{p}}1}\)………. \({L}_{{\rm{p}}m}\), where m is the number of lines projected. The result is shown in Fig. 6a for the sample image.

By identifying the vertical kernel of the profile line, signary localization, or vertical character segmentation over \({L}_{{\rm{p}}}\), is carried out. Iteratively extracting the image’s vertical lines using morphological techniques enables the detection of the vertical kernels. The weighting values alpha and beta are taken as 0.5 and 1−alpha, respectively, for iterations i. Signary are localized appropriately by altering the height h and width w hyper-parameters. A variation in image size can be used to modify the w and h parameters. The characters are localized, and the signary is represented as \({{\rm{S}}{\rm{C}}}_{i}\), where \({{\rm{S}}{\rm{C}}}_{i}\) is a group of character images \({{\rm{S}}{\rm{C}}}_{i1}\), \({{\rm{S}}{\rm{C}}}_{i2}\), and \({{\rm{S}}{\rm{C}}}_{i3}\)……\({{\rm{S}}{\rm{C}}}_{in}\) where n is the total number of character images in a line. Each localized character image has a unique index idx. The character images in \({{\rm{S}}{\rm{C}}}_{i}\) are organized and sorted in a way that is successively localized by the line image. The method maintains the order of characters in the inscription script, and the localized signary shown in Fig. 6b are obtained. The signary localization is described in Algorithm 2 as in Fig. 7. In Algorithm 2, bound points of a character \({B}_{{\rm{c}}}\) that has four coordinates, \({K}_{{\rm{v}}}\) is the kernel detection point of vertical lines, and height h and width w are hyper-parameters. Here, it is assumed as 80 and 10.

Solving the bound box issues

To address the different issues while applying the bound box for the line image, such as resulting in a single box for two or more characters or a split bound box for a single character, or superimposed bound boxes. Due to unconstrained carvings of characters in the inscription images, there appear like touching characters, wide-spaced characters (i.e.) large spacing between characters, or less spaced characters (i.e.) condensed spacing between characters and deteriorated characters. These cases are discussed below as follows:

While inscribing the stones, there might be less space to complete a script within a particular stone, hence the writings may be crammed. Some of the characters in the image are with condensed space, with touching strokes, and overlapped, which may be bounded by a single bound box during localization, which in turn reduces the performance of character recognition. This is solved by applying sequential morphological operations like thinning, Gaussian blur, thresholding, and dilation, erosion to the enhanced line-localized image. Thinning is a procedure that relies on a specific element known as the morphological kernel element j to determine its course. Binary structuring elements are utilized in this process, which is linked to a transformation. This transformation represents a general binary morphological process designed to aim at detecting specific configurations of object and non-object pixels in an image, incorporating both 1 and 0 s. The thinning process is carried out by systematically positioning the anchor point of the morphological kernel element at each pixel location throughout the image. At every position, a comparison is made between the structuring element and the corresponding image pixels. The thinning of a line image \({L}_{i}\) by a morphological kernel element j can be described as follows in Eqs. (11) and (12). It defines the thinned layer \({L}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}}\) as the result of a thinning function applied to\(({L}_{i},j)\), while Eq. (12) expresses that thinning involves subtracting a transformation from the original layer to get \({L}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}}\).

The separation of light and dark regions is accomplished by thresholding after applying a Gaussian blur as in Eq. (4) over \({L}_{{it}}\). By setting all pixels below a certain threshold to zero and all pixels within that threshold to one, thresholding converts greyscale images into binary ones. If g(x, y) is a version of f(x, y) that has been thresholded to obtain \({L}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{h}}}\) at some global threshold T as in Eq. (13),

Erosion that shrinks regions of interest and eliminates fine details or noise from a binary image is denoted by\({M}_{{\rm{e}}}\). Finally, the structural element erodes the thresholded line image. A new binary image, \(g={L}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{h}}}\theta s\), is created when a line image \({L}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{h}}}\) is eroded by a structuring element s (denoted \({L}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{h}}}\theta s\)) as in Eq. (14).

Then DPB is applied to \({M}_{e}\) as in Algorithm 1 to get the bound boxes of all the characters individually. Sample results for touching and condensed spaced characters are shown in Fig. 8a–d.

Concentrating on the deteriorated characters, and if the bound box is applied to the image, some of the unwanted strokes curvatures, and noises like dots and lines may also get bound. As some of the script writings have more gaps among characters, and if the bound box is applied to the image, a split bound box for a single character is obtained since there are some minute fissures (i.e.) broken strokes in the corresponding character. This also results in poor localization and degrades the performance of signary recognition. This is solved by applying Gaussian blurring as in Eq. (4) over the image \({L}_{i}\) followed by thresholding as in Eq. (14) and dilation. The morphological kernel probe dilates the thresholded line image. A new binary image, \({g=L}_{{ithresh}}{\rm{\theta }}s\), is created by the dilation of an image \({L}_{{ithresh}}\) by a morphological kernel element s (denoted \({L}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{h}}}\theta s\)), and the dilation of the image is denoted by \({M}_{{\rm{d}}}\) as in Eq. (15).

Dilation fills the fissures and gaps exist in the strokes of the corresponding character. Then \({M}_{{\rm{d}}}\) undergoes the DPB algorithm as in Algorithm1 and this avoids a split bound box and results in the perfect bound of a character. Samples of line images with deteriorated and wide space characters are shown in Fig. 9a–d.

Morphological transformation is depicted in Algorithm 3 for solving bound box issues as in Fig. 10. In Algorithm 3, boxcount is initialized as the total count of the \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}}\) values obtained for \({L}_{{\rm{i}}}\), countval is the parameter value of the estimated \({{\rm{M}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{t}}}\) values to be obtained for \({L}_{{\rm{i}}}\). If boxcount value is larger than countval then morphological erosion \({M}_{{\rm{e}}}\) is applied otherwise morphological dilation \({M}_{{\rm{d}}}\) is applied. Morphologically transformed images \({M}_{{\rm{i}}}\) are collectively obtained and these images in turn represent \({L}_{{\rm{i}}}\) which undergoes Algorithm 1 again.

Signary recognition with C-CNN and SignaryNet

The localized characters are grouped and binned separately according to the classes numbered from 0 to 99, verifying the characters with the 11th-century Tamil, Grantha, and Sanskrit letters mentioned. They are then size-normalized, and the less frequent character images are augmented, such as mostly Grantha and Sanskrit letters; needed this, and each class consists of 1000 character images. A sequential architecture called the Classic-CNN (C-CNN) model was created to categorize 64 × 64 grayscale images into 100 different classes. An output feature map of shape (62, 62, 16) is produced by starting with a Conv2D layer with 16 filters, a kernel size of (3, 3), ReLU activation, and an input shape of (64, 64, 1). The dimensions are then reduced to (31, 31, 16) via a MaxPooling2D layer with a pool size of (2, 2). The output of the second convolutional layer is (14, 14, 32) and is composed of 32 filters and the same (3, 3) kernel, followed by another (2, 2) max pooling. A third MaxPooling2D layer that uses 64 filters with a (3, 3) kernel and ReLU activation comes after the third Conv2D layer. A third MaxPooling2D layer reduces the output to (6, 6, 64) after the third Conv2D layer uses 64 filters with a (3, 3) kernel and ReLU activation. After that, the feature maps are flattened into a 2304-unit 1D vector. To avoid overfitting, this vector is sent to a dense layer with 512 units and ReLU activation, then a dropout layer with a dropout rate of 0.5. With 100 units and a softmax activation function, the final dense layer generates probability scores for every class. The Adam optimizer is used to construct the model, with accuracy as the evaluation metric, sparse_categorical_crossentropy as the loss function (for outputs with integer labels), and a learning rate automatically set by default.

The C-CNN is then fine-tuned specifically for the signary recognition of ancient Tamil inscription characters, which is known as SignaryNet. SignaryNet is an optimized convolutional neural network (CNN), a hyperparameter-tuned deep neural network and is the most advanced image categorization model that is more than adequate to digitally recognize individual characters from the inscriptions designed for recognizing inscription characters, such as Tamil vowels ( etc.), Tamil consonants (

etc.), Tamil consonants ( etc.), Sanskrit (

etc.), Sanskrit ( etc.), the adjacent prefix suffix supporters of consonants (

etc.), the adjacent prefix suffix supporters of consonants ( etc.), and the Grantha or Brahmi characters in modern Tamil characters. It is an approach that uses deep CNN architecture for recognizing ancient Tamil characters with sequence characters employed to complete the task. The proposed design uses deep neural network layers to extract features from input character images, and signary recognition is then fed to the feature map. Here, labelled set sequences are used to train the network. The three key equations that represent its core functionality of Convolutional operation feature extraction layer and each convolution layer applies filters (kernels) to the input image to produce a feature map as in Eq. (16).

etc.), and the Grantha or Brahmi characters in modern Tamil characters. It is an approach that uses deep CNN architecture for recognizing ancient Tamil characters with sequence characters employed to complete the task. The proposed design uses deep neural network layers to extract features from input character images, and signary recognition is then fed to the feature map. Here, labelled set sequences are used to train the network. The three key equations that represent its core functionality of Convolutional operation feature extraction layer and each convolution layer applies filters (kernels) to the input image to produce a feature map as in Eq. (16).

\({F}_{i,j}^{k}\) is the output feature map at position (i, j) for filter k, I is the input image or previous layer’s output, Kk is the kth convolutional kernel of size M × N, and bk is the Bias for the kth filter. After convolution, activation \({A}_{i,j}^{k}\) is applied to introduce non-linearity, such as in Eq. (17).

The final classification is done using softmax, which outputs a probability distribution over all classes as in Eq. (18).

\({z}_{c}\) is the Output (logit) of the dense layer for class, C is the total number of character classes, \(P\left(y=c|x\right)\) is the probability that input x belongs to class c. In this case, SignaryNet is represented as a 2D convolutional network made up of layers called Conv2D and MaxPooling2D. Conv2D will analyse character image snapshots, and pooling layers will consolidate the analysis. Then this initializes a model and prepares a training dataset for a classification task. The architecture accepts input of shape (64 × 64 × 1) and begins with stacked convolutional layers: the first block comprises two Conv2D layers with 32 filters each and ReLU activation, interleaved with BatchNormalization layers and followed by a ZeroPadding2D and MaxPooling2D operation to preserve spatial resolution and reduce dimensionality. The convolution class’s yield is blended with the ReLU activation function and the same padding, conserving the spatial confines of the input image, similar to the yield image, which is the same size as the input image. Applying the zero padding as (2, 2) adds zeros to the end of the input sequence. This pattern continues through progressively deeper layers with 64 and 128 filters, each block incorporating dropout layers (rates: 0.25, 0.25, and 0.4, respectively) for regularization. After flattening, the network includes a dense layer of 256 units with ReLU activation, and an additional Dropout of 0.5 is used to handle vanishing gradients, followed by a final dense softmax layer outputting 100 classes with float32 precision. The output softmax layer receives the probabilities of output character prediction for the corresponding number of classes from the dense layers of filters together. Using mixed_float16, hybrid precision training is enabled to maximize training performance, and tf.config.optimizer.set_jit(True) activates XLA XAccelerated Linear Algebra to increase execution efficiency. With a learning rate of 0.001 and a loss function of categorical cross-entropy, the model is constructed using the Adam optimizer. Greyscale images from designated data for training and validation are prepared for processing and pre-processed by the training pipeline. Data augmentation strategies include random horizontal flipping, rotation (±10%), and zooming (±10%), applied only to the training dataset. All images are normalized by rescaling pixel values to the [0, 1] range. For model training, we incorporate early stopping with a patience of 5 epochs to prevent overfitting and learning rate reduction on plateau (factor = 0.5, patience = 2) to enable finer convergence during stagnation. The model is trained using a batch size of 64 and a maximum of 50 epochs. Final evaluation includes plotting training and validation accuracy curves, confusion matrices, and precision-recall-F1 statistics derived via classification_report. The model is saved in the Keras format (.keras), and its performance can be fine-tuned using the built-in learning rate scheduler or further extended with transfer learning by freezing initial layers and re-training on new data. Using Unicode mapping, the signary are recognized in modern Tamil. The signary is predicted as shown in Algorithm 4, as in Fig. 11.

For signary recognition as in flow of SignaryNet in Fig. 12, shows how an inscription character image is recognized to a contemporary Tamil character, which has a mapping file that contains the Unicode of the relevant character images of 0–99 classes, as seen in Fig. 13a–c.

Results

Enhancement and line localization of script images

The sample enhanced images from the dataset of the high-resolution camera captured 11th-century inscription images archived as in ref. 44, are experimented as below for line localization, signary localization, SLR computations, and also for the state-of-the-art methods comparison. The inscription images with different inscribing styles (i.e.) clear as well as glutted writing with varying numbers of lines are taken as samples and are enhanced. The inscription images are enhanced as shown in Fig. 14a are then line localized using horizontal line projection and the results are represented as in Fig. 14b localization of line images from each image is done as in Algorithm 1.

Signary localization in script images

The proposed DPB method to process signary localization for sample images has been experimented and the number of localized characters is compared with existing bound box methods. Table 3 displays the results and the SLR in Eq. (19) as discussed. The existing methods demonstrate that the localized characters are not distributed in a sequential manner and with split strokes and over-segmented characters as a result. The proposed DPB technique eliminates the over-segmentation problem by displaying evenly sized characters sequentially ordered, without split strokes. For example, in Image (1), the Existing Bound Box correctly localized 68.96% of characters, whereas the Proposed DPB significantly improved accuracy to 98.62%. Similarly, the Proposed DPB outperformed the existing bound box in the other two images, offering higher localization success rates, particularly in Image (2) (96.59% vs. 64.77%).

According to Eq. (19), the signary localization rate (SLR) or Segmentation Rate is determined by subtracting one and the number of characters that were incorrectly localized from the total number of characters that need to be localized, which is expanded in Eq. (20). Characters that are wrongly localized show evidence of being under- or over-segmented. If there are more strokes from the adjacent characters, the segmented character image is under-segmented. When two or more characters are segmented as the same character due to touching strokes or when a single character is split into numerous segments, this is known as over-segmentation. As a result, as shown in Eq. (20), the localization rate may also be calculated by subtracting one and the sum of the under-segmentation rate USR as the ratio of under-segmented characters to the total number of characters to be localized in Eq. (21) and the over-segmentation rate OSR as the ratio of over-segmented characters to the total number of characters to be localized as in Eq. (22), and SLR as in Eq. (23).

The signary localization rate is calculated for segmenting images having 1730 lines and 19,137 original characters. With 206 under-segmented and 127 over-segmented characters, we obtain 18,924 actual localized characters and 18,804 correctly localized characters, which are then plotted as shown in Fig. 15a. According to Table 4, an overall signary localization rate of 98.25% was found, and Fig. 15b illustrates the same with USR and OSR.

Some of the touching characters and overlapping strokes of the characters are detected and they are not localized individually. Some of those samples are shown as follows in Fig. 16.

Binning, augmentation and standardization

The characters are grouped through the process of binning into 100 classes based on their structural similarity, combining Tamil consonants, vowels, Sanskrit, Grantha, mixed Sinhalese, Brahmi, and Malayalam characters, which are classified as 0–99. Each image represents a different character class, ensuring that each class has a total of 1000 images to balance the dataset for character classification tasks. The process initially counts the number of images currently available for each class to determine how many more examples are needed. If there are not enough images in the dataset, it does transformations including rotation, shifts, shearing, zoom, and horizontal flipping using an ImageDataGenerator to increase data diversity and model resilience. For every underrepresented class, new images are made using existing ones until the target number is met. This process also safeguards the original images by copying them to the directory containing the improved samples. The augmentation process assists in providing a constant distribution of data across classes, which is necessary for training stable and objective models. This method is particularly useful for ancient character detection, where dataset imbalance is common. All things considered, it improves model generalization and reduces overfitting. The input dimensions of the images for the model should be standardized. At this step, every image is shrunk to a fixed resolution of 64 × 64 pixels using high-quality Lanczos resampling. This reduction step is crucial for preparing image datasets for training since a constant input size is required for batch processing and model compatibility. Additionally, scaling reduces and standardizes image resolution, which minimizes training computational costs. When dealing with extensive image datasets, this method is quite advantageous.

Signary recognition C-CNN and SignaryNet model outcomes

Each class of 1000 characters in the model, including augmented characters, contains 100 classes and hence contains 100,000 character images. There are approximately 80,000 character images in the training data, 20,000 character images in the validation data, and 10,000 character images in the testing data, which are used for prediction. The character images in the training/test set are labelled with the range 0–99 in the folders and also separately stored with the appropriate letters in classname.npy file for isolated character recognition. The class ID labels on the character images in the training/test set match the Unicode of contemporary Tamil characters in a CSV file.

The C-CNN model has a total of 1,253,756 parameters, all of which are trainable, indicating a fully parameterized architecture designed for complex classification tasks. After the convolutional layers, the output is reshaped into a 2304-dimensional linear array. The fully connected dense layer has 512 units with ReLU activation, followed by a softmax output layer with 100 units for classification. The model uses the Adam optimizer and sparse categorical cross-entropy as the loss function, but it does not include data augmentation or mixed precision. The model has undergone forty epochs of the learning phase. While the accuracy for training was 86.67%, the accuracy for validation was 83.33% and the prediction accuracy of 84.74%. The SignaryNet model is created and has been evaluated using different test data. Tamil and grantha/Sanskrit characters can be found in the test instances. The SignaryNet model architecture, as summarized as in Fig. 17a, is a deep convolutional neural network specifically tailored for high-accuracy recognition across 100 classes. It begins with two convolutional layers with 32 filters, followed by batch normalization and zero padding to preserve spatial dimensions. The model then applies max pooling and dropout (25%) for spatial reduction and regularization, which are applied after the MaxPooling layers corresponding to feature maps of sizes (32 × 32 × 32), (16 × 16 × 64), and (8 × 8 × 128). This pattern continues with 64 and 128 filters in deeper convolutional blocks, each followed by batch normalization, pooling, and increasingly aggressive dropout (up to 40%), effectively preventing overfitting and enabling robust feature extraction. Post-convolution, the model flattens the output into an 8192-dimensional vector, passing it through a fully connected dense layer with 256 units and 50% dropout, ensuring strong high-level abstraction with regularization. Finally, a softmax layer with a 100-unit map is added to the output classes. The total parameter count is ~2.26 million, with only 640 non-trainable parameters, indicating an almost fully trainable model. This balance between depth, regularization, and trainability makes SignaryNet both computationally efficient and highly effective for complex inscription signary image classification tasks. While the accuracy for training is 96.20%, the accuracy for validation is 98.61%, and the prediction of the signary is made for the single characters as shown in Fig. 17b from test data, and the prediction accuracy is 96.81%. The detailed metrics of C-CNN and SignaryNet are given in Table 5.

SignaryNet performance optimization and hyper-parameter tuning

Together with adjustment, the hyperparameter settings can greatly increase the SignaryNet model’s accuracy and resilience. Enhancing the dataset and pre-processing images can significantly improve generalization. In this instance, adding random changes such as rotation, scaling, zoom, and horizontal flip to Tamil characters will help the model better manage input variations. These augmentations are applied before normalizing the images to the range [0, 1]. To prevent stochastic behaviour from leaking into the validation phase, training = True is removed from the augmentation pipeline during .map(). Dropout is a key regularization method used to drop units at random during training to avoid overfitting. Achieving equilibrium between regularization and model capacity can be facilitated by adjusting the dropout rate. For SignaryNet, a dropout of 0.25 for hidden layers and 0.5 for dense layers is used. In a SignaryNet, the quantity and size of filters are critical. Effectively capturing local and global elements is crucial for intricate scripts, such as Tamil inscriptions. The model begins with two Conv2D layers employing ‘same’ padding to preserve spatial resolution, ReLU activation, and 32 filters of size (3 × 3). The second block doubles the filters to 64, maintaining the same structure with MaxPooling2D to reduce dimensionality and Dropout (0.25) to prevent overfitting. Due to increased feature complexity, the third block extends filters to 128 and increases dropout to 0.4 for stronger regularization. The extracted feature maps are flattened and fed into a fully connected layer containing 256 neurons, with a dropout rate of 0.5 applied to enhance regularization.

Zero padding is used after batch normalization in architectures like SignaryNet to ensure that the spatial dimensions of the feature maps are preserved before further convolution or pooling operations. After a convolutional layer, the spatial size of the feature map can shrink depending on the kernel size and stride. Zero padding ensures the output has the same height and width as the input, which is important when it is needed to retain spatial information, especially with ancient script characters that may have intricate or fine details especially ancient scripts (like Grantha or Brahmi) often have small strokes near the edges and hence, zero-padding helps prevent these edge features from getting lost in repeated convolutions. Batch normalization levels off learning, speeds up convergence, reduces internal covariate shift, and is applied immediately after convolution and before non-linearity (ReLU). After batch normalization and activation, zero padding can be applied before the next convolution to ensure proper receptive field alignment and control over output dimensions. This preserves detail and dimension while ensuring stability and performance.

By adding non-linearity to the model, the activation function enables it to recognize increasingly intricate patterns. ReLU is effective, and since it determines how quickly the model learns, the learning rate is to be adjusted. The adaptive learning rate approach, which uses optimizers like Adam to modify the learning rate during training based on the gradient, is employed in the SignaryNet model. It is initially set to a default of 0.001 and uses categorical cross-entropy. During training, optimizers regulate how the weights are changed. Adam’s adjustable learning makes it a good option. Training speed and convergence can be improved with proper weight initialization. Although it could be slower and more computationally costly, a smaller batch size might provide a finer gradient estimate for the model. Training can be accelerated with a larger batch size, but the gradient estimations may be less accurate. The initial value for medium-sized datasets is 32. Since the GPU RAM in this SignaryNet model supports 64, it is utilized. The frequency count of the model depends on the epochs. Here, 50 epochs are used to train the SignaryNet model while early stopping is in place. Training may be stopped early if the validation accuracy begins to decrease while the training accuracy increases. To monitor validation accuracy or loss, 5–10 epochs of patience can be allowed before discontinuing. Meanwhile, EarlyStopping ensured training halted once improvements plateaued, thereby saving resources and preventing overfitting. Here, the SignaryNet model makes use of a learning rate schedule such as ReduceLROnPlateau. To facilitate finer learning in later stages, two important call backs are utilized during training: ReduceLROnPlateau (factor = 0.5, patience = 2) to halve the learning rate when performance plateaus and Early Stopping (patience = 5) to stop training if validation loss doesn’t improve. To maintain a good trade-off between learning new information and fine-tuning existing knowledge, the learning rate is systematically adjusted throughout training using scheduling techniques.

A ModelCheckpoint callback is added to automatically save the model weights corresponding to the highest validation accuracy, ensuring both the preservation of the best model and maximum reproducibility. It successfully saved the best-performing model whenever validation accuracy improved. EarlyStopping conserves resources by halting the progress once improvements plateau. Learning rate scheduling worked effectively, reducing the rate smoothly without triggering early stopping prematurely, indicating the model was still improving even up to epoch 38. Additionally, the use of mixed precision training for computational efficiency and XLA (accelerated linear algebra) compilation improved computational efficiency. Despite achieving over 96% training accuracy, the tight alignment with validation accuracy indicated strong generalization and low variance.