Abstract

White and black wares hold a significant historical position in Chinese art and ceramics due to their distinctive decorative techniques. This study comparatively analyzed representative white and black wares from Pacun (Yuzhou City) and Xin’an kilns (Luoyang City) in Henan Province. The chemical composition of the bodies and glazes present no obvious difference, except for slightly higher TiO₂ and Fe2O3 contents in the Xin’an glazes than those in Pacun glazes. All bodies conform to the characteristics of high aluminum and low silicon of clay in the Chinese northern region. The color generation of the black decoration of both types of wares could be attributed to a joint action of Mn ions and hematite crystals, in which the Fe ions may be substituted by other ions. Besides, similar firing temperatures were used for the wares from Pacun and Xin’an kilns, which range from 1200 to 1250 °C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

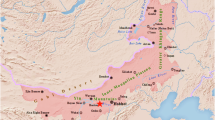

White and black wares have occupied a prominent position in the history of Chinese art and ceramics, owing to its distinctive national style, regional features, and unique decorative techniques1. They appeared during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), flourished during the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234 CE) and declined during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1356 CE). Spanning approximately five centuries from the Northern Song through Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, these wares were extensively produced across northern China, forming the largest network of folk kilns in the region, primarily encompassing the Pengcheng and Guantai kilns in Hebei Province, along with the Hebiji, Dangyangyu, Pacun, and Xin’an kilns in Henan Province (Fig. 1). These manufacturing hubs, functioning as both trade nodes and technological incubators, fostered cross-cultural artistic dialog between ceramic traditions spanning from East Asia (notably Japan and Korea) to West Asia2. Among them, the Pacun and Xin’an kilns have attracted significant academic attention as representative archeological sites in the central-western Henan Province. Pacun kilns are located in Yuzhou City (Henan Province, China)1. Xin’an kilns are located near the western capital of the Song Dynasty—Luoyang City3. Due to the proximity of Xin’an County to Yuzhou City (Fig. 1), many scholars believed that the Xin’an productions were influenced to some extent by the Pacun kilns3.

At present, research on white and black wares mainly focuses on studying chemical and mineral composition to understand the color generation and manufacturing technology. Li et al. 4 summarized the chemical composition of bodies of white and black wares from the Cizhou kilns, Hebijji kilns, Pacun kilns, and Dangyangyu kilns and found that the bodies of Cizhou kilns are composed of one or two kinds of clay with poor quality. Chen et al.5,6 also analyzed the raw materials of bodies, glazes and black decors of the wares excavated from Cizhou kilns and found that the composition of the bodies is basically as similar as that of the three sections of the soils in Laoyayu and Linshui (Handan city). The glazes were probably made from a mixture of white glaze soil, fetal mud and plant ash and the color resembles specklestone or limonite. Besides, Chen et al.5,6 indicated that the Fe2O3 content and flux oxides in the bodies of wares from Hebiji kilns were significantly higher than those of Cizhou wares, and the firing temperature of the formers ranged from 1130 to 1170 °C. Wang et al. 7 conducted a study on the white and black wares produced in Huozhou kilns (Linfen City, Shanxi Province) and found that the chemical composition of bodies aligns with other typical northern productions. The black decoration is predominantly influenced by the size, quantity, and concentration of brown Ti-doped hematite crystals, along with the thickness of the glaze layer and the presence of other crystals7. Xu et al. 8 studied the chemical composition and microstructure of white and black wares from Jizhou kilns and found that the bodies and glazes were manufactured with local clay. Moveover, the wood ash containing sericite might be also used for the glazing preparation. Black or reddish-brown patterns could be attributed to the hematite particles or a mixture of hematite and metastable ε-Fe2O3 crystals precipitated on the glaze surfaces, respectively. However, previous studies mainly focus on Cizhou, Hebiji and Jizhou kilns, few research on the chemical and structure of the bodies, glazes and decorations of the wares from famous Pacun and Xin’an kilns. Only decorative styles and art forms of Pacun and Xin’an wares were analyzed and reported2,9.

In the study, a series of techniques including optical microscopy (OM), X-ray fluorescence (XRF), scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), micro-Raman spectroscopy (μ-RS) and dilatometer (DIL) were exploited to study the chemical composition, microstructure and firing temperatures of white and black wares from Pacun and Xin’an kilns. Based on the results, the raw material characteristics of the bodies, glazes and black decorations, the color generation of black decorations, and the firing temperature of the wares were discussed.

Methods

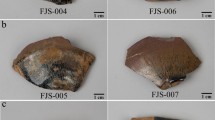

In total, 45 pieces of white and black fragments (19 pieces from the Pacun kilns and 26 pieces from the Xin’an kilns) were selected and could be dated to the Song and Jin Dynasties (960-1234 CE) according to the archeological layer. Figure 2 present six representative samples. Table 1 illustrates characteristics of the exterior appearances of the wares. The magnified observations (Supplementary Fig. 1) present an obvious contrast between the black decorations and the surrounding transparent glaze.

The samples were cut by diamond soil and prepared as cross-sections. The details were described elsewhere7. The glaze surfaces were removed by sanding and polishing to avoid any effect of the transparent glazes on black decorations. Then, the uncovered black decors could be directly analyzed by SEM-EDS and μ-RS.

Analytical methods

Optical microscopy (KEYENCE VHX7000, Japan) was used to observe the decorative patterns in the glaze surfaces and the cross-sections using a circular light source. The observations show that the cross-section mainly contains four layers, namely the glaze, black decoration, white slip, and body (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The elemental compositions of the glaze surfaces and bodies were measured using a HORIBA XGT-7200V energy-dispersive XRF with an X-ray beam diameter of 1.2 mm, energy power of 30 kV and acquisition time of 120 s. Three points were analyzed for each body, glaze, and black decoration to assess the homogeneity of the different areas. In addition, a 19 × 19 mm area was selected on the glaze surface for the XRF-mapping analyses to investigate the elemental distribution. The testing conditions were as same as those used for point scanning, with a resolution of 128 dpi.

Prior to the SEM-EDS analyses, the surfaces of the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold to enhance their conductivity. The morphology and elemental composition of the crystals in the glaze were investigated using the backscattered electron mode of a scanning electron microscope(FEI Verios 460) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer analysis system. The beam diameter was approximately 0.2 μm.

Micro-Raman investigations were performed using a Renishaw inVia spectrometer. Raman excitation was provided by a cw 532-nm solid state laser. The laser spot size was around 2–3 μm diameter. A laser power of 1.31 mW at x100 magnification was employed to optimize the signal background ratio and avoid any thermal influence. The spectra were recorded in the 100–1600 cm–1 range. Raman spectral data were compared with the RRuff Raman standard spectral database (website: https://rruff.info/).

The DIL402PC thermal expansion instrument was used to analyze the linear expansion or contraction process of the samples during the re-firing process at different firing temperatures. The size of the sample was prepared as 25 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm. The heating rate was 10 K/min. The blowing gas Nitrogen was used at a flow rate of 50 mL/min.

Results

Chemical composition analysis

Table 2 shows the average chemical composition of the bodies of the samples, the details shown as Supplementary Table 1, 2. The contents of Al2O3 and SiO2 in the Pacun bodies are around 24.8 wt% and 65.4 wt%, respectively, while in Xin’an bodies, around 22.3 wt% and 67.7 wt%, respectively. Both types of the bodies present similar Na2O (~1.1 wt%), MgO (~0.7 wt%), K2O ( ~ 2.1 wt%), and CaO (~1.0 wt%) concentrations. The colorant elements are mainly Fe2O3 and TiO2, with the content of around 4.0 wt% and 1.1 wt%, respectively. The scatter plots were displayed to further comparatively analyse the samples. Supplementary Fig. 3a shows that the Al2O3 content of the bodies of the Pacun kilns is slightly higher but the SiO2 content is lower than those of Xin’an kilns, exhibiting the characteristic of “high aluminum and low silicon” of Chinese northern clay. The K2O-CaO content is concentrated within 1–3 wt% and 0.2–1.6 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 3b), respectively, and the flux contents are not significantly different. Supplementary Fig. 3c presents that the colorant elements TiO2-Fe2O3 contents in the Pacun bodies are slightly higher than those of the Xin’an bodies, consistent with the darker bodies of the Pacun wares observed by OM (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Table 3 shows the average chemical composition of the glazes of the samples from Pacun and Xin’an kilns. The details were illustrated as Supplementary Table 3, 4. The contents of Al2O3 and SiO2 in the glazes are around 11.7 wt% and 71.3 wt%, respectively. The Na2O content is around 2.0 wt%, and MgO is 1.4 wt% in both. K2O content of around 4.3 wt%, CaO content of around 7.2 wt%, and MnO2 content of around 0.1 wt% were detected. The TiO2 content ranges from 0.2 wt% to 0.5 wt%. The Fe2O3 content ranges from 1.3 wt% to 1.6 wt%. The Al2O3-SiO2 and K2O-CaO content distribution overlapped between the two kilns (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). Meanwhile, the TiO₂ and Fe2O3 contents in the Xin’an samples are generally higher than those in the Pacun samples (Supplementary Fig. 3f), in agreement with the darker glaze of the Pacun wares observed by OM (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Comparative analyses were conducted on the chemical composition of white and black wares glazed from the other northern kilns, as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3a–c. Table 3 and Fig. 3 display that the contents of Al2O3 and SiO2 in the glazes of Pacun and Xin’an kilns range from 9.1 to 13.6 wt% and 66.4 to 74.9 wt%, respectively, while the contents in Cizhou and Hebiji glazes vary from 16.65 to 20.0 wt% and 63.4 to 72.3 wt%, respectively. Besides, the contents of K2O and CaO in the glazes of Pacun and Xin’an kilns range from 2.3 to 6.2 wt% and 3.1 to 13.7 wt%, respectively, while their contents in Cizhou and Hebiji kilns vary from 2.3 to 3.9 wt% and 2.6 to 5.5 wt%, respectively. The colorant elements TiO2 and Fe2O3 amounts in the glazes of Pacun and Xin’an kilns range from 0.2 to 0.7 wt% and 0.9 to 3.1 wt%, respectively, while their contents in Cizhou and Hebiji kilns vary from 0.22 to 0.34 wt% and 0.31 to 1.9 wt%, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3b).

Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3h–i compared the chemical composition of the glazes and black decorations of the Pacun and Xin’an samples. The average contents of colorant elements TiO2, MnO2, and Fe2O3 in the glazes of Pacun samples are around 0.2 wt%, 0.1 wt%, and 1.3 wt%, respectively. The contents of TiO2, MnO2, and Fe2O3 in the black decorations of Pacun wares are around 0.3 wt%, 0.3 wt%, and 8 wt%, respectively. The average contents of TiO2, MnO2, and Fe2O3 in the glazes of Xin’an wares are around 0.5 wt%, 0.1 wt%, and 1.6 wt%, respectively. The contents of TiO2, MnO2, and Fe2O3 in the black decorations of Pacun samples are 0.6 wt%, 0.2 wt%, and 5.8 wt%, respectively.

To further investigate the distribution of coloring elements in the black decorations, three representative samples were selected and subjected to XRF mapping analyses (Fig. 4). The glaze of sample PCY-03 exhibits relatively higher Si and lower Ca concentrations compared to the black decoration, while the black decoration present obvious higher Mn and Fe amounts compared to the glaze, with their concentration decreasing from the core to the periphery (Fig. 4a). Conversely, sample PCY-09 presents a homogeneous distribution of Si and Ca in the glaze and black decoration, whereas the black decoration also contains obviously higher Mn and Fe contents compared to the glaze (Fig. 4b). Sample PCY-14 also displays a homogeneous distribution of Ca in the glaze and black decoration, but the glaze exhibits slightly Si enrichment compared to the black decoration. The colorant elements Mn and Fe in the black decoration of sample PCY-14 present similar distribution compared to samples PCY-03 and PCY-09 (Fig. 4c). The elemental distributions of Xin’an samples (Fig. 4d–f) also present that Si and Ca homogeneous distribution in the glazes and black decorations, and the black decorations are composed of obviously higher Mn and Fe concentrations compared to the glazes.

Micromorphology and structural analyses

SEM-BSE imaging and EDS analyses were performed on the particles in the decorations (Fig. 5 and Table 4). SEM observations show that the size of the particles is aound 5 μm (Fig. 5a, b). The corresponding EDS spectra (Table 4) shows that the atomic content of Fe in the particles of the two samples was around 19 atomic% (40.86 weight%), indicating that these particles could be iron-based crystals. The other atomic contents of Na, Mg, Al, Si, K, and Ca should be derived from the glassy matrix. Removing the influence of the glassy matrix, one could calculate that the particle mighty also contain a small quantity of Al and Ti ions in addition to Fe ions.

Micro-Raman measurements were further performed on these particles to identify their speciations. The main characteristic peaks (Fig. 6, curve a) of the particles in Pacun decors are located around 230 cm–1, 300 cm–1, 418 cm–1, 514 cm–1, 628 cm–1, 680 cm–1 and 1353 cm–1, corresponding to A1g, Eg, Eg, A1g, Eg, Eu (LO) and 2-Eu (LO) of hematite (α-Fe2O3), respectively10,11. Figure 6b, c presents Raman features of the paritcles in Xin’an decors similar to Fig. 6, curve a, identified as hematite crystals. Besides, these features of Xin’an samples present a significant shift towards higher wavenumbers compared to one of Pacun wares. To explore the differences between the peak positions of crystals in the glazes, the scatter diagrams of typical peak located around 300 cm–1 versus typical peak located around 620 cm–1, and versus typical peak located around 670 cm–1 were plotted, shown as Fig. 7a, b, respectively. The position of typical peaks of hematite crystals in Pacun decors are mainly concentrated at 296–309 cm–1, 615–650 cm–1 and 670–698 cm–1, respectively, while those of crystals in Xin’an decors are mainly around 292–300 cm–1, 604–620 cm–1 and 660–675 cm–1.

Optical observation of the glaze surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 4) shows that several types of crystals were found in the glaze surfaces. The corresponding Raman spectra are recorded and shown in Fig. 8. A strong band position around 462 cm–1 and three weaker bands (127 cm–1, 202 cm–1, and 358 cm–1) were found in all samples (Fig. 8a pt01, b pt01, c pt02, d pt03, e pt01 and f pt01), consistent with the typical Raman features of quartz (α–SiO2)12. Crystals in the PCY-03, CGY-08 and CGY-13 samples present the characteristic peaks located around 196 cm–1, 276 cm–1, 485 cm–1, and 508 cm–1 (Fig. 8a pt02, e pt03, f pt02) which could be attributed to anorthite7. The Raman peak position around 145 cm–1 (Fig. 8e pt01) could be identified as anatase13. The peaks locating around 144 cm–1, 237 cm–1, 443 cm–1, and 611 cm–1 (Fig. 8f pt04) could belong to rutile, while the peaks positioning around 213 cm–1, 233 cm–1, 347 cm–1, 471 cm–1, 680 cm–1 and 812 cm–1 (Fig. 8f pt03) could belong to pseudobrookite14. Interestingly, the peaks locating around 508 cm–1, 577 cm–1, 667 cm–1, and 702 cm–1 (Fig. 8b pt02) were identified as chromite (RRUFF: 110060) in the PCY-09 sample. However, chromite particles were only observed in PCY-09 galze. Besides, a strong band position around 670 cm–1 and four weaker bands (236 cm–1, 322 cm–1, 506 cm–1, and 558 cm–1) were found (Fig. 8a pt03, c pt03, and e pt04), consistent with typical Raman features of magnetite15. The Raman peaks of particles in PCY-14 and GQC-01 glazes positioning around 128 cm–1, 156 cm–1, 174 cm–1, 234 cm–1, 304 cm–1, 358 cm–1, 381 cm–1, 444 cm–1, 496 cm–1, 579 cm–1, 688 cm–1, 728 cm–1, and 1364 cm–1 (Fig. 8c pt01 and d pt02) are consisntent with Raman features of as ε-Fe2O316,17,18. The crystals found in the glazed surfaces and black decors are summarized in Table 5.

a PCY–03 pt01: quartz, pt02: anorthite, pt03: magnetite, pt04: hematite. b PCY–09 pt01: quartz, chromite. c PCY–14 pt01: ε - Fe2O3, pt02: quartz, pt03: magnetite, pt04: hematite. d GQC - 01 pt01: hematite, pt02: ε - Fe2O3, pt03: quartz. e CGY - 08 pt01: anatase, pt02: quartz, pt03: anorthite, pt04: magnetite, pt05: hematite. f CGY - 13 pt01: quartz, pt02: anorthite, pt03: pseudobrookite, pt04: rutile, pt05: hematite.

Firing temperatures

Raman spectra were recorded at the glassy matrix of the samples, shown in Fig. 9. Two vibration bands appeared at 500 cm–1 and 1000 cm–1 originate from the bending and stretching modes of [SiO4]n- 19,20,21, respectively. The area ratio of the bending versus stretching modes (labeled as Ip) could serve as a crucial parameter for evaluating the firing temperature of the glazes22, which is directly correlated with the firing temperature. The Ip values of the samples were calculated and listed in Table 6. The Ip value of Pacun wares is around 1.36–2.11, while the Ip value of Xin’an wares is around 1.60-1.78. According to the replicated experiments23, the 1.29, 1.43, 1.63, 2.17 and 2.40 of Ip value could correspond to the firing temperature of around 1110 °C, 1150 °C, 1200 °C, 1250 °C and 1300 °C, respectively.

To precisely verify the firing temperature of the samples, the PCY-03 sample was selected for destructive thermal expansion analysis. This method is often used to determine the firing temperature of ceramics24,25. The thermal expansion curve was shown in Fig. 10. The final temperature of the sample heating was around 1300 °C, and no over-burning occurred. The tangent method analysis was used to determine 1275 °C as the inflection point temperature. Above 1275 °C, the reverse expansion phenomenon was observed, probably due to the decomposition of Fe2O3 above 1270 °C23. Besides, the inflection point temperature of the re-firing thermal expansion curve is usually higher than the original firing temperature, typically about 20 °C, when the Al2O3 content in the body is relatively high or the SiO2 content is relatively low26. Therefore, the actual firing temperature of the sample may be about 1250 °C, consistent with the analyses of Ip value of glassy matrix (Ip~2.11, 1250 °C).

Discussion

The chemical compositions of the wares were compared with the northern kilns including Pengcheng (PC) and Guantai kilns (GTY) (Hebei province), Hebiji kilns (HBY), Pacun (PCY) and Xin’an kilns (XAY) (Henan province), shown as Table 2. The SiO2 content in the bodies of the Pacun and Xin’an kilns is slightly lower than the wares from the other kilns. On contrary, the Al2O3 content was slightly higher than others. The contents of Na2O, MgO, K2O, CaO and TiO2 present no significant variation. The content Fe2O3 of the two kilns is relatively higher than Hebiji and Dangyangyu kilns, possibly due to using iron-rich of body raw materials4. According to the chemical composition of the local clay in Pacun County (Supplementary Table 5)27, the raw materials of the Pacun glazes might be made from a mixture of Laozhuang soil, quartz, feldspar, limestone, or muscovite in a certain proportion. Besides, Xin’an kilns used similar raw material sources due to the small difference in chemical composition between Xin’an and Pacun glazes (Table 3 and Fig. 3a–c). The chemical composition of the black decorations at different kilns was compared, shown as Table 3. The contents of TiO2, MnO2, and Fe2O3 in the black decorations were higher than those in the glazes. According to the literature1, Pacun region produces specklestone, which is a limonite rich in Fe2O3, TiO2, and MnO25,6. One could conclude that the raw material of the black decorations could be prepared using local specklestone. Besides, Xin’an decors might use the similar pigment due to the similar chemical compositions (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3h–i). The black decoration of Fe and Mn distribution was higher than glaze in all samples (Fig. 3), which is consistent with the analyses in Table 3.

The Raman spectroscopic evidence for hematite crystals was observed in most samples. Among the position peaks of the hematite spectra, the extra strong band around 670 cm–1 could be attributed to the superposition effect of magnetite28,29,30, thermal treatment and weathering, or the disruption of lattice symmetry due to doping with Al28,31 and Ti32, which was detected by EDS analyses (Table 4). The Raman features of hematite crystals in Pacun decors present a significantly shift towards higher wavenumbers compared to crystals in Xin’an decors, possibly due to the change in lattice structure caused by the substitution of Fe in the hematite by other elements7,10,33, consistent with the EDS analyses (Fig. 7 and Table 4). Other crystals in glaze mainly include quartz, anorthite, pseudobrookite, rutile, anatase and the crystals in black decorations mainly include hematite, magnetite and ε-Fe2O3. Interestingly, numserous chromite particles were observed in the glaze of one Pacun sample (PCY-09). Ti based crystals were detected in the samples of Xin’an kilns, consistent with higher Ti amount in Xin’an glazes than Pacun glazes (Table 3). In the area of the black decoration, a large number of hematite crystals were observed, while no manganese (Mn) crystals were found. Based on the results, the color formation mechanism of the black decoration could be deduced to the main combined effect of hematite crystals and Mn ions. Besides, a few magnetite crystals were found in the black decorations of the two kilns (Table 5 and Fig. 8), which could be related to the specklestone used as the raw materials5.

The firing temperature for PCY-03 determined by the tangent method of thermal expansion analysis was 1250 °C, consistent with the Ip value based on Raman measurements, demonstrating that non-destructive massive Raman analyses of glassy matrix combined with destructive thermal expansion measurement of several representative bodies were effective approach to identify the firing temperatures of the wares. Based on the results, the wares from Pacun and Xin’an kilns present similar Ip values, indicating the firing temperature ranging from 1200 to 1250 °C.

In summary, the chemical composition of bodies the two kilns conforms to the characteristics of high aluminum and low silicon of the Chinese northern caly. The small difference in chemical composition between Xin’an and Pacun glazes indicates that both kilns might use similar raw materials to prepare the glazes. The main coloring elements of the black decorations are Mn and Fe. The color generation of the black decoration could originate from a main joint action of hematite crystals and Mn ions. Only one sample present numerous chromite crystals, giving rise to yellowish-brown color. EDS and Raman analyses indicated iron ions in hematite might be partially substituted by other ions. The Raman features of hematite particles in Pacun decors present a significant shift towards higher wavenumbers compared to those of hematite crystals in Xin’an decors. Besides, other types of crystals were found in the surfaces of samples, mainly including quartz, anorthite, pseudobrookite, rutile, and anatase in glaze, several ε-Fe2O3 and magnetite crystals in black decorations. Based on Raman analyses of glaze and thermal expansion measurement of body, the firing temperature of wares from both kilns was estimated to be various from 1200 to 1250 °C.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Fu, Y. Research on white and black wares from Pacun Kilns (扒村窑白地黑花瓷研究). Natl. Art. Mus. China J. 8, 108–115 (2006). (in Chinese).

Wang, J., Geng, B. & Tu, H. Famous kiln in ancient China - Cizhou Kiln (中国古代名窑 - 磁州窑). Dou, M. & Chen, B. (eds.), pp. 82–83 (Jiangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, 2016). (in Chinese).

Zhao, Q. & Wang, D. Investigation of Ancient Porcelain Kiln Site in Xin’an County, Henan Province (河南省新安县古瓷窑遗址调查). Cult. Relics. 12, 74–81 (1974). (in Chinese).

Li, G. & Guo, Y. Fundamentals of Chinese Famous Porcelain Craftsmanship (中国名瓷工艺基础). Li, G. & Guo, Y. (eds.), pp. 108–109 & 154 (Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers, 1988). (in Chinese).

Chen, Y., Guo, Y. & Liu, L. Research on Raw Materials for Black Brown Porcelain in Cizhou Kiln (磁州窑黑褐彩瓷用原料研究). J. Ceram. 1, 29–36 (1988). (in Chinese).

Chen, Y., Guo, Y. & Zhao, Q. Preliminary Study on Black and Brown Colored Ceramics from Hebiji Kiln. (鹤壁集窑黑、褐彩陶瓷的初步研究). China Ceram. 5, 51–58 (1988). (in Chinese).

Wang, M., Faulmann, C., Wang, F., Wang, T. & Sciau, P. Microscopic study on characteristic decorative black and white porcelain produced in Shanxi province, Jin and Yuan dynasties (AD 1115 - 1368). China J. Raman Spectrosc. 55, 1236–1246 (2024).

Xu, C., Li, W. & Lu, X. Manufacturing technique for Jizhou painted porcelains in the Yuan dynasty and its influence on coloring. Ceram. Int. 50, 994–1005 (2024).

Zhang, Y. Research on Ceramic Art of Pacun Kiln in Yuzhou, Henan Province (河南禹州扒村窑陶瓷艺术研究). Zhengzhou University. (2018). (in Chinese)

Marshall, C. P., Dufresne, W. J. B. & Rufledt, C. J. Polarized Raman spectra of hematite and assignment of external modes. J. Raman Spectrosc. 51, 1522–1528 (2020).

Colomban, P. Full spectral range raman signatures related to changes in enameling technologies from the 18th to the 20th Century: guidelines, effectiveness and limitations of the Raman analysis. Materials 15, 3158 (2022).

Sato, R. K. & McMillan, P. F. An infrared and Raman study of the isotopic species of α-quartz. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 3494–3498 (1987).

Medeghini, L. et al. Micro-Raman spectroscopy and ancient ceramics: applications and problems. J. Raman Spectrosc. 45, 1244–1250 (2014).

Wang, T., Sanchez, C., Groenen, J. & Sciau, P. Polarized Raman spectroscopy: A new tool for the non-destructive analysis of cultural heritage objects. J. Raman Spectrosc. 47, 1522 (2016).

Jubb, A. M. & Allen, H. C. Vibrational spectroscopic characterization of hematite, maghemite, and magnetite thin films produced by vapor deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 2804–2812 (2010).

Lopez Sanchez, J. et al. Sol-gel synthesis and micro-Raman characterization of ε-Fe2O3 micro-and nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 18, 511–520 (2015).

Hoo, Q. Y. et al. Formation mechanism of the pinholes in brown glazed stoneware from Yaozhou kiln. Archaeometry 64, 644–654 (2021).

Li, G. et al. The earliest known artificial synthesized ε-Fe2O3 in the Deqing Kiln ceramic ware of Tang Dynasty. Heritage Sci. 11, 1–9 (2023).

Colomban, P. Polymerization degree and Raman identification of ancient glasses used for jewelry, ceramic enamels and mosaics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 323, 180–187 (2003).

Colomban, P., Maggetti, M. & d’Albis, A. Non-invasive Raman identification of crystalline and glassy phases in a 1781 Sèvres Royal Factory soft paste porcelain plate. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 38, 5228–5233 (2018).

Wang, T. et al. Micro-structural study of Yaozhou celadons (Tang to Yuan Dynasty): probing crystalline and glassy phases. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 40, 4676–4683 (2020).

Colomban, P. & Paulsen, O. Non-destructive determination of the structure and composition of glazes by Raman spectroscopy. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 88, 390–395 (2005).

Chen, P. et al. Nondestructive study of glassy matrix of celadons prepared in different firing temperatures. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 1360–1370 (2021).

Tong, Y. & Wang, C. Study on firing temperature of the Song Dynasty (960–1279AD) greenish-white porcelain in Guangxi, China by thermal expansion method. Herit. Sci. 7, 70 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Determination and interpretation of firing temperature in ancient porcelain utilizing thermal expansion analysis. Herit. Sci. 12, 282 (2024).

Ding, Y. et al. Simulation experiments on the influences of elemental composition and firing temperature of porcelain bodies on the thermal expansion method for temperature measurement (实验法探讨瓷胎元素组成和烧成温度对热膨胀法测温的影响). Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 35, 81–89 (2023). (in Chinese).

Jin, P. et al. Research on Ancient Chinese Ceramics (中国古陶瓷研究) (ed. Wang, L., Li, Z., Feng, X. & Zhu, C.) 94-108 (Forbidden City Publishing House, (in Chinese). (2003)

Froment, F., Tournié, A. & Colomban, P. Raman identification of natural red to yellow decoration: ochre and iron-containing ores. J. Raman Spectrosc. 39, 560–568 (2008).

Shebanova, O. N. & Lazor, P. Raman spectroscopic study of magnetite (FeFe2O4): a new assignment for the vibrational spectrum. J. Solid State Chem. 174, 424–430 (2003).

Bersani, D., Lottici, P. P. & Montenero, A. A micro-Raman study of iron-titanium oxides obtained by sol-gel synthesis. J. Raman Spectrosc. 30, 355 (1999).

Zoppi, A., Lofrumento, C., Castellucci, E. M. & Sciau, P. Micro-Raman spectroscopy of ancient ceramics: a non-destructive tool for revealing the technology and art. J. Raman Spectrosc. 39, 40 (2008).

Rull, F., Martinez-Frias, J. & Rodríguez-Losada, J. A. μ-Raman spectroscopy as a useful tool for improving knowledge of ancient ceramic manufacturing technologies. J. Raman Spectrosc. 38, 239–244 (2007).

Wang, A., Kuebler, K. E., Jolliff, B. L. & Haskin, L. A. Raman spectroscopy of Fe-Ti-Cr-oxides: case study of Martian meteorite EETA79001. Am. Mineral. 89, 665–675 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work has been financially supported by the China National Natural Science Foundations (Nos. 62205191, 52272019, and 52272020), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (No. GZB20230396), the Shaanxi Natural Science Basic Research Project (No. 2023WGZJ-YB-45), the Key Laboratory of Silicate Cultural Relics Conservation (Shanghai University), Ministry of Education (No. SCRC2024KF02ZD). It was performed in the framework of the research collaboration agreement (CNRS No. 186116) between the French National Center for Scientific Research and the Shaanxi University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.QY : Wrote the main manuscript text. Z. JF : acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Funding. W. F: Funding, acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Resources, Information provision. R.Z: Writing-review, editing, Funding, acquisition, Investigation. P. S : Supervision, Methodology. L.Q: Supervision, Methodology. L. HJ: Supervision, Methodology. W.T : Writing-review, editing, Funding, acquisition, Investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Participate declaration

All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Publish declaration

All authors have agreed to the publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Zhu, J., Wang, F. et al. Microstructural study of white and black wares of Pacun and Xin’an kilns (Henan Province, China). npj Herit. Sci. 13, 349 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01915-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01915-4