Abstract

Within contemporary tourism contexts, classical-garden spatial narratives have become decoupled from visitor behaviours, underscoring the need to elucidate mechanisms for engagement. This study investigates the Du Fu Thatched Cottage in Xishu Gardens as a case study, integrating panoramic imaging, semantic segmentation and machine learning to quantify five visual-spatial metrics: naturalness, commemorativeness, complexity, scale and colour. Visitor dwell time and visit frequency were recorded via a panoramic roaming platform. The results reveal that the spatiotemporal distributions of visual attributes and visitor dwell and movement behaviours synergistically align along the central axis. These distributions exhibit positive correlations, with commemorative element visibility and water-body coverage showing the strongest associations and manifesting multidimensional threshold effects within the commemorative dimension. By examining both dwell and movement behaviours, this study uncovers synergistic mechanisms underlying heritage-space interactions and offers actionable recommendations for the sustainable conservation and management of classical gardens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chinese Classical Gardens, often described as ‘green fossils’ that embody the essence of Chinese culture, constitute a non-renewable, irreplaceable heritage resource1. However, the rapid rise of mass tourism has created a pronounced disjunction between the gardens’ commemorative narratives and visitors’ on-site behaviour, giving rise to a 'human-activity mismatch' that threatens the long-standing ideal of harmony between people and nature. This disconnect weakens interpretive value, threatens sustainable use and presents a critical challenge in international cultural-landscape conservation. The Xishu Gardens illustrate this rupture most acutely, with the once-effective experience of 'wandering in a painted scene' not resonating with contemporary tourists2,3,4. Bridging this gap first requires a macro-scale understanding of how spatial form shapes visitor movement, thereby paving the way for micro-level perceptual studies and, ultimately, achieving sustained human–garden harmony and shared flourishing.

Landscape and tourism behaviour can be conceptualised on two complementary yet temporally progressive scales: a macro spatio-temporal displacement scale and micro instantaneous-perception scale. The macro scale depicts how individuals occupy and migrate through space, whereas the micro scale captures sensory orientation and cognitive processing. At the macro level, behavioural responses to environmental stimuli can be simplified into a 'dwell-move' framework5,6, characterised by two states: movements, i.e. continuous decisions and preferences, and dwelling, i.e. spontaneous pauses or stays7,8. These two states constitute the most immediate manifestations of perceptual behaviour. Empirical work has been conducted in cities9, streets10, protected areas11,12, scenic destinations13,14,15,16,17 and museums18 to identify9, assess10,11,15,17, predict12,18,19 and optimise18,20 movement behaviour. Regardless of scale, both displacement and perceptual behaviour are ultimately driven by the integration and feedback of multisensory information, including vision, audition, olfaction, tactility and vestibular-proprioception. Grahn and Stigsdotter21, drawing from environmental psychology and restorative theory, proposed the perceived sensory dimensions (PSD) framework to evaluate sensory experiences in outdoor environments. Building on PSD, Qi et al.22,23 expanded the openness dimension into visual scale and introduced four spatial-quality metrics: naturality, complexity, consistency and visual scale. Inspired by biological visual processing, Cao et al.24 developed a landscape-perception metric system encompassing colour attributes, landscape elements, spatial form and landscape imagery, further underscoring the primacy of vision. Shen et al.25 proposed spatial characteristics for Chinese Classical Gardens, emphasising openness, complexity and theatricality. Li et al.26 highlighted that spatial design features, such as visibility, complexity and aesthetic experience, significantly impact short-term dwelling behaviour. Collectively, these studies indicate that the sensory dimension framework is highly relevant for analysing Chinese Classical Gardens, particularly in terms of naturality, complexity and visual scales.

Current research on classical gardens suffers from methodological bottlenecks in both the spatial and behavioural dimensions, obscuring the coupling between eye-level perception and visitor movement. These deficiencies are evident in two respects:

First, the spatial dimension. Quantitative analysis of spatial characteristics in Chinese Classical Gardens is crucial for predicting visitor perceptual behaviours. However, the diverse elements, complex forms and variable spaces of Xishu Gardens27 pose greater challenges for measurement compared to modern gardens. Researchers have attempted to overcome this limitation by adopting high-resolution techniques, including terrestrial laser scanning, digital photogrammetry and panoramic imaging, to establish parallel two- and three-dimensional frameworks (Table 1). Nevertheless, most studies still rely on overhead space-syntax metrics of global connectivity that cannot detect soft or semi-transparent components such as vegetation clusters or framed vistas. Consequently, the micro-cues that mediate human–scene interaction are systematically overlooked and existing indicator systems fail to account for intrinsic heritage qualities, notably commemorative value.

Second, the behavioural dimension. Standard tools for tracking displacement, such as field surveys and online studies, perform poorly in heritage contexts. Field campaigns that synchronise handheld GPS trajectories with perceptual questionnaires do provide high-resolution itineraries, but they are easily confounded by time of day, weather and crowd density (CD), making it impossible to isolate the guiding role of visual features on move–dwell behaviour28. Online investigations that mine public data through crowdsourcing suffer from limited coverage, discontinuity, positional error and sample heterogeneity, whereas laboratory experiments using photographs, videos, or virtual reality (VR) scenes, although free from onsite disturbance, typically focus on a handful of key nodes, undermining spatio-temporal continuity and comparability29. These technical obstacles are compounded by strict conservation regulations and restricted site access, which further hamper variable control and continuous data collection. Accordingly, a research paradigm that delivers spatio-temporal integrity from common sources and fits the realities of heritage environments is needed to enable a systematic examination of the entire visual-feature—behavioural-mechanism chain.

Overall, spatial data and behavioural data remain heterogeneous in origin, and a unified data framework has yet to be established. Taking Song et al.30 as an example, the authors attempted to fuse panoramic imagery with social-media check-in data, providing preliminary evidence for multi-source integration; however, differences in acquisition periods and positional accuracy still pose technical challenges to precise alignment. Such heterogeneity not only weakens the closed loop between spatial metrics and perceptual-behavioural validation but also undermines the reproducibility and comparability of research findings. Moreover, compared with the topics listed in Table 1, current studies on perception and behaviour in classical gardens pay insufficient attention to the dynamic coupling of dwelling and movement, and a systematic explanatory model for the dual dwell-move behaviour, especially displacement, remains to be developed.

Panoramic images with a 360° perspective enhance the accuracy and interactivity of spatial perception, facilitating a controlled connection between the physical environment and behavioural responses. They effectively address data scarcity, measurement challenges and spatiotemporal heterogeneity, thus providing a more convenient and computationally efficient alternative31. Panoramic images are widely used in urban studies and are often combined with semantic segmentation to achieve pixel-level spatial analysis32,33. Furthermore, with the growing adoption of Web 3D panoramic technology, virtual displays have become prevalent in digital museums, including the British Museum, Louvre and Forbidden City34,35. These technologies offer several advantages, such as realistic reproduction, a unified experience, broad coverage and enhanced accessibility36,37. Using panoramic imagery and semantic segmentation, Song et al.30 innovatively proposed a human-scale 'space—perception—behaviour' model for Suzhou gardens and confirmed that the Sky View Index significantly influences crowding behaviour, demonstrating the feasibility of panoramic techniques for behavioural studies in classical gardens. Accordingly, the comprehensive use of panoramic imagery and technology can create a bridge between physical and virtual spaces, offering a feasible solution to address spatiotemporal heterogeneity.

In summary, the present study identifies three pivotal research gaps: (1) existing visual index systems skew heavily toward geometric dimensions and seldom capture the cultural semantics intrinsic to the heritage fabric; (2) a unified, source-consistent quantitative pathway capable of simultaneously recording spatial features and displacement behaviour is lacking; and (3) the coupling mechanisms linking visual attributes to the dual processes of dwelling and movement are insufficiently elucidated. Against this backdrop, using the Dufu Thatched Cottage as a case study, this study constructed a unified visual data chain, integrating high-fidelity panoramic twins, semantic segmentation and deep learning. Specifically, the aims were to:

-

1.

Develop a framework to quantitatively determine visual features of heritage spaces and visitor displacement behaviours.

-

2.

Investigate the influence of visual landscape attributes on the dwelling and movement patterns of visitors and the associated mechanisms.

-

3.

Identify patterns within the axial narrative space that reveal the synergy between landscape characteristics and dwell-move behaviour.

Centred on visual information, the present study establishes an integrated 'visual-attributes–displacement-behaviour' analytical framework, providing empirical support for heritage conservation and route optimisation in classical gardens.

Methods

This study selected the Du Fu Thatched Cottage (DFTC) within Xishu Gardens, a nationally protected cultural heritage site and a 4A-rated tourist attraction, as the research subject based on criteria such as cultural heritage protection status, historical value, spatial layout, commemorative themes and prominence. The DFTC is located on Caotang Street, Qingyang District, Chengdu and covers ~24 ha. This historic garden has a long history, having attained its current extent through multiple phases of renovation and expansion. Historical documents confirm that from the Qing dynasty onward, the site featured a layout in which an ancestral hall served as the focal point and structures were arranged along a central axis38. The axial ensemble centred on the Temple of the Ministry of Works has been preserved and continues to serve as the principal commemorative narrative feature. Field investigations by Xu2,38 underscored the axis’s predominant commemorative significance. With reference to that delineation, the present study defines the heritage core zone of the DFTC to encompass the Temple of the Ministry of Works, Caotang Temple, Thatched Cottage Scenic Area, Plum Garden and Flower Path area (Fig. 1).

This study focused on heritage spaces and dwell and movement behaviour, analysing the influence of landscape spaces on pausing and movement behaviours (Fig. 2). The research process comprised three components: data collection, extraction and analysis. Data extraction involved taking spatial measurements using semantic segmentation and behaviour quantification through panoramic web platforms.

Data collection

The primary dataset for this study consisted of panoramic images and behavioural data, enabling a point-to-point match between physical spatial data and dwell and movement behaviour data. The panoramic images (7680 × 3840 pixels) were collected using an Insta360 Pro2 device (Arashi Vision Inc., Shenzhen, China) equipped with six fisheye lenses capable of capturing 720° high-definition panoramic views.

Data were collected on 26 April 2024 between 08:00 and 10:00 at the DFTC during a spring non-holiday morning, capturing 88 images under minimal visitor presence near opening hours. This timing was selected to (1) align with the spring imagery of Du Fu’s poetry (e.g. ‘A timely rain knows its season; it happens when spring begins’ in Happy Rain on a Spring Night)39, (2) take advantage of stable vegetation and optimal lighting for high-definition imaging, and (3) avoid peak visitor periods to record authentic behavioural patterns. Collection points were set every 3–10 m at a capture height of 150 cm, and precise coordinates were recorded using GPS (Fig. 1). Post-processing was completed using Insta360 Stitcher software, employing optical flow.

This study collected the dwell times and visit frequencies of the participants at each point, as well as demographic information and immediate evaluation data, using a self-developed panoramic cloud-based touring platform (URL provided in the supplementary material). Dwell time serves as a measure of pausing behaviour, with longer dwell times indicating greater attraction to a location. Visit frequency indicates movement inclination, with higher frequencies suggesting stronger attraction for movement behaviour at that point. A threshold of more than one second was set with event logging to record entry and exit times at each viewpoint, calculating the dwell time in seconds. Each time participants entered a new panoramic viewpoint, their location data were continuously recorded and uploaded to the server at regular intervals.

Spatial measurement based on semantic segmentation

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the semantic-segmentation workflow comprised three stages: manual annotation, segment anything model (SAM)-based prediction and optimisation.

The commemorative aspects of the Xishu Garden are primarily represented by architectural and garden ornaments, including sculptures, inscribed plaques, couplets, epigraphs and cultural relics, all of which hold significant historical and cultural value3,40 To capture these characteristics more accurately, this study introduced a category of commemorative elements while maintaining a clear semantic classification. An 11-category semantic classification system was established as shown in Table 2.

The study utilises SAM to refine the semantic segmentation of panoramic images and produce high-precision visual grids for behavioural analysis. SAM maintains over one billion pre-generated masks, supports zero-shot inference and provides global feature extraction, interactive usability, and high-resolution compatibility41. Given that existing public datasets scarcely include classical garden scenes with historic architecture and commemorative elements, SAM’s training-free capability effectively addresses the shortage of large, annotated corpora. To address the requirements of classical garden environments, an annotation schema of 11 semantic classes was developed. Trained landscape architecture students performed initial labelling and two domain experts subsequently reviewed all annotations to ensure consistency and accuracy. From these labels, masks and positive–negative sample points were generated; the SAM Vision Transformer (ViT-H) model then produced segmentation predictions, which were further refined using morphological operations in OpenCV. The eroded masks and SAM predictions were merged through intersection-over-union operations to produce precise segmentation regions, as illustrated in (Fig. 3b). Using manual annotations as ground truth, the optimised model achieved an average mIoU of 0.813, an increase of 0.187 compared to the initial output. The bare-soil and people classes showed the greatest gains from morphological edge correction, with mIoU values increasing to 0.588 and 0.421, respectively. Following segmentation, OpenCV, NumPy, scikit-image and pandas were used to batch-compute and extract landscape feature metrics across the large-scale mask grids.

Drawing on the PSD framework and relevant studies, this study developed a comprehensive indicator system that encompasses elements, features and dimensions. Five core dimensions were identified to quantify the physical and spatial characteristics of Xishu Gardens from a viewpoint, including naturalness, commemorativeness, complexity, visual scale and colour. The specific indicators are listed in Table 3.

Online survey procedure and settings

This online experiment, conducted using a purpose-built panoramic platform, was divided into three stages: pre-experiment preparation, preliminary survey and formal experiment. All the participants were students, experts, or professionals in the fields of landscape or heritage, ensuring a high level of familiarity with and interest in the research topic. Students received instructions on the experimental process through a centralised session, whereas professionals from other fields were invited to participate remotely. The detailed steps of the experimental procedure are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Before the experiment began, the participants received an introduction to the platform’s operations and usage guidelines. The specific requirements for the experiment were as follows: participants were instructed to imagine themselves in a garden and engage in natural exploration; participants must use a high-performance desktop or laptop computer with a clear display and a stable Internet connection; exploration time must be at least 10 min to ensure a comprehensive experience of the garden; participants were required to remain focused during exploration, avoid distractions, or switch browser tabs.

During the preliminary survey stage, participants accessed the platform’s homepage, where they read the experimental instructions, provided informed consent and completed an information survey capturing socio-demographic variables, including personal information, professional background and prior experience. They then proceeded to the garden overview interface to prepare for the formal experiment.

During the formal experiment stage, participants freely explored the garden using the panoramic platform, navigated through 720° panoramic views with their mouse, and clicked directional markers to move to the next viewpoint. To ensure participants could fully explore, each viewpoint required a self-reported immediate evaluation before proceeding, which included scenic beauty and pleasure ratings. Upon reaching a designated endpoint or after the allotted time (≥10 min), participants clicked 'End Browsing' to complete the experiment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in three sequential steps. First, following data cleaning, spatial distributions of landscape attributes, dwell time and visit frequency were visualised to reveal spatial heterogeneity. Second, distributions of landscape attributes, dwell time, visit frequency and control variables (demographics and road infrastructure) were calculated and examined, with key influencing factors identified via Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing regression and Pearson correlation analyses. Third, guided by distribution-test results, explanatory predictive models were constructed to explore relationships between dwell and movement behaviour and landscape attributes.

For dwell time, Model 1 was specified as a generalised linear mixed-effects model, linking dwell time to landscape attributes, accounting for hierarchical data structure and treating visitor identity as a random effect. As dwell time is a non-negative continuous variable, the model was fitted by maximum likelihood assuming a Gamma distribution with a log link; regression coefficients quantify each attribute’s effect on log-transformed dwell time. For visit-frequency data, a generalised linear model with a negative binomial response distribution was fitted by maximum likelihood. Landscape attributes remained the primary focus; demographic controls (respondent characteristics, disciplinary background, prior experience, self-assessment and momentary affect) and infrastructural controls (road level, entrance step depth and node degree) were included and variance inflation factors were calculated to assess multicollinearity. All analyses were implemented in R Studio (version 4.4.1).

Results

Descriptive statistics

User data were pre-processed to filter out low-frequency users who visited fewer than five sites and outlier records with single-visit durations exceeding 600 s. The final dataset comprised 349 users and 12,652 records. The average age of the participants was 23 years and males comprised 36% of the sample. Of all participants, 88.4% held a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 70% were local residents. Students made up 64% of the sample. The number of participants who had previously visited the DFTC was roughly equal to that of those who had not (Supplementary material Table 1).

Descriptive statistics were conducted on the landscape feature data and four key variables of dwell and movement behaviour: single visit duration, total user visit duration, average visit duration per site, and visit frequency per site. The results show that the average single-visit duration was 14 s, which aligns with the natural viewing rhythm. The average visit duration per user was 724 s. The average visit duration per site ranged from 10.36 to 55.67 s, while the average visit frequency per site was 145. Overall, significant variations in dwell and movement behaviour were observed in terms of dwell time and visit frequency.

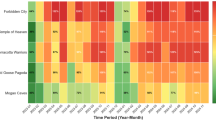

Second, trend and correlation analyses were conducted for the dwell time and visit frequency. Figure 5 shows that dwell time and visit frequency were correlated with landscape features. Specifically, the pairs quantitative diversity of commemorative elements—categorical diversity of commemorative elements (CDCE), fractal dimension (FD)—shape compactness (SC), contrast (C)—sky openness (SO), greenery visual ratio (GVR)—brightness (B) and beautiful—significance exhibited particularly strong positive correlations, whereas spatial enclosure (SpE)—SO and GVR—road level (level) exhibited particularly strong negative correlations.

a Pearson correlations between dwell time and the variables, b Pearson correlations between visit frequency and the variables. Note: The heat map displays Pearson’s correlation analysis, where the colours range from red (indicating a positive correlation) to blue (indicating a negative correlation), with white representing a weak correlation. Non significant correlations are marked with an 'X'. Significance: pleasure evaluation, beautiful: scenic beauty evaluation.

Spatial patterns of landscape characteristics

Figure 6 illustrates the spatial distribution of the four landscape feature dimensions, revealing significant differences and distinctive characteristics:

a Greenery visual ratio, b water body proportion, c bare soil proportion, d visual proportion of commemorative elements, e quantitative diversity of commemorative elements, f categorical diversity of commemorative elements, g Shannon entropy, h shape compactness, i fractal dimension, j crowd density, k sky openness and l spatial enclosure, m brightness, n contrast and o saturation.

The analysis of naturalness in the DFTC showed distinct spatial variations in the GVR, water body proportion (WBP) and bare soil proportion (BSP). The GVR was the highest in the central and northern areas (0.6) and lower at the edges (0.2–0.4), displaying a symmetrical distribution along the central axis. The WBP was the highest in the eastern and parts of the northern regions (0.05–0.075), while the southern and western areas had almost no WBP. The BSP was generally low, with a maximum of 0.06, primarily in the central and northern areas. The overall low exposure BSP may be due to the data collection occurring in spring when the vegetation is lush.

Commemorative elements in the DFTC are concentrated in the middle-to-rear section of the central axis, where their visual proportion and quantity are the highest. This emphasises the central axis as the core of the landscape and underscores the significance of this area within the heritage site. While the QDCE was concentrated here, the CDCE was relatively uniform across space, indicating a balanced spatial distribution of different historical and cultural elements without distinct clustering of specific types.

This complexity was concentrated at pathway intersections and major landscape nodes. The areas surrounding the commemorative buildings were designed with compact symmetry, whereas regions with high FD exhibited irregular characteristics. Although complexity indicators overlap in spatial distribution, they provide unique insights into spatial design from different perspectives.

CD was highest along the central axis and in the central area (0.006). SO was concentrated along the central axis and in the southern areas (with a maximum of 0.20), whereas SpE was concentrated on both sides of the central axis and in the northern region (with a maximum of 0.6). The alternation between openness and enclosure along the central axis creates a continuous spatial sequence, imbuing the area with a strong narrative quality.

Figure 6(m–o) illustrates that the spatial distributions of B, C, and saturation (S) closely correspond to those of the complexity index, with no significant overall differences. All three metrics reach their maximum values in the distal segment of the central-axis main line—specifically at the Thatched Cottage ruins, the Red-Wall Bamboo-Shadow entrance, and along the waterfront belt. B and C distributions exhibited the highest concordance, with maximum B (145.28) and C (66.11) values occurring along the central-axis main line, followed by the waterfront zone. The mean B and C were 115.17 and 51.12, respectively. S was highest at the Thatched Cottage ruins (124.31), and indoor spaces also displayed relatively elevated S, resulting in an inverse gradient relative to B and C across certain central-axis segments. Low-value zones for all three indicators were observed in the semi-open corridors flanking the axis and adjacent interior spaces, indicating diminished chromatic stimuli in these areas. Overall, B and C jointly reinforced the visual prominence of the central-waterfront axis, whereas the localised increase in S at the Thatched Cottage ruins accentuated this node’s distinctive role within the overall colour spectrum.

Spatial patterns of dwell and movement behaviour

The spatial visualisation in Fig. 7a reveals that the central axis entrance area, waterfront area and site of the thatched cottage exhibited longer dwell times with an overall even distribution. The central axis entrance area and site of the thatched cottage were closely associated with commemorative elements, whereas the waterfront spaces were linked to water features. This suggests that points with longer dwell times were strongly correlated with these distinctive landscape features.

The spatial distribution of visit frequency revealed that high-frequency areas closely aligned with the central axis of the DFTC and exhibited a distinct pattern of fluctuation (Fig. 7b). This suggests that the central axis, as a core guiding element in garden design, plays a significant role in commemoration and spatial orientation.

Modelling results for dwell behaviour

Maximum-likelihood estimation identified the Gamma distribution as optimal for Model 1 (AIC = 34 243.94); accordingly, a Gamma model with a log link was adopted. The model explained a substantial proportion of variance (conditional R² = 0.641; marginal R² = 0.231), and diagnostic tests confirmed that all statistical assumptions were met. To address multicollinearity, predictors with variance-inflation factors (VIF) > 5 (QDCE, FD, SO, B) were excluded, thereby reducing every remaining VIF below the threshold (Supplementary material, Table 3). The analysis indicates that core landscape attributes and several socio-demographic covariates retain significant associations with dwell duration (Fig. 8).

Generalised linear mixed-effects model (gamma distribution) predictions for the association between dwell duration and each landscape feature: a GVR, b WBP, c BSP, d VPCE, e CDCE, f SE, g SC, h CD, i SpE, j C and k S. Note: The solid line represents model predictions. Red lines indicate positive effects, whereas blue lines indicate negative effects. The significance levels are denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

A one-unit increase in CD (β = 76.748, p < 0.001) produced an exponential rise in dwell time, evidencing a pronounced crowd-attraction effect. Higher WBP (β = 7.265, p < 0.001), greater commemorative visual coverage (VPCE, β = 1.812, p < 0.001), and C (β = 0.012, p < 0.001) also prolonged stays. In contrast, GVR (β = −0.312, p < 0.001), CDCE (β = –0.063, p < 0.001), SpE (β = –0.789, p < 0.001), and S (S = –0.001, p = 0.045) reduced dwell duration. Among infrastructural variables, road hierarchy (level, β = –0.070, p < 0.001) and step depth (depth, β = −0.013, p < 0.001) discouraged prolonged stopping. Familiarity exerted a marginally negative effect (familiar level, β = −0.082, p = 0.08), whereas perceived beauty was positive (beautiful, β = 0.035, p = 0.034); all other variables were non-significant. In summary, dwell behaviour was promoted by commemorative value, water features, and crowd ambience, whereas excessive greening, fragmented elements and deeper pathways suppressed stays.

Modelling results for movement behaviour

In Model 2, to mitigate over-dispersion in the count data, both Poisson and negative-binomial specifications were fitted and evaluated using AIC and BIC; the negative-binomial specification exhibited the superior fit (AIC = 1 045.09 vs. 14 626.20). Consequently, the negative-binomial distribution was selected as the response distribution, yielding Nagelkerke’s R² = 0.822 and all diagnostic tests confirmed that model assumptions were met. To eliminate multicollinearity, variables with VIF > 5, QDCE, SO, FD, B, Bachelor, Student, Manager and familiar level were removed. The remaining predictors all exhibited VIFs below the threshold (Supplementary material, Table 4).

The results show that essential landscape attributes and several control variables continue to exert significant effects on visit frequency (Fig. 9). Specifically, the influences of landscape elements and spatial-geometric metrics on visit frequency diverge markedly. WBP (β = 9.336, p = 0.044), VPCE (β = 6.947, p = 0.012) and CDCE (β = 0.261, p < 0.001) exerted positive effects. Likewise, node degree (Degree, β = 0.297, p < 0.001) exhibited a significant positive impact, suggesting that highly connected nodes encourage repeat visitation. Conversely, spatial-geometric indicators exert a pronounced inhibitory effect. Specifically, SpE (β = −2.702, p = 0.011) and SC (β = −0.009, p = 0.043) markedly reduced visit frequency. Nodes situated on higher-order or greater-depth paths similarly dampen the willingness to return (Level, β = −0.225, p = 0.032; Depth, β = −0.086, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that routes that are enclosed, convoluted, or excessively hierarchical are unfavourable for generating repeat flows.

Generalised linear model (negative-binomial distribution) predictions for the association between visit frequency and each landscape feature: a GVR, b WBP, c BSP, d VPCE, e CDCE, f SE, g SC, h CD and i SpE, j C and k S. Note: The solid line represents model predictions. Red lines indicate positive effects, whereas bluelines indicate negative effects. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

At the socio-demographic level, the proportion of local residents (Province local, β = 4.620, p < 0.001) and share of previous visitors (Ever visit (Yes), β = 2.013, p = 0.034) were significantly positive, emphasising the loyalty of local groups and returnees. While the overall proportion of visitors with higher education exerts a positive influence, the master’s degree subgroup showed a negative preference (Master, β = −1.955, p = 0.038), implying differences in interest across educational backgrounds. The proportion of female visitors significantly reduced visit frequency (female, β = −3.776, p = 0.002), reflecting gender differences in visitation motivation. In contrast, the influences of GVR and CD were not significant after controlling for other variables, indicating limited independent contributions.

Overall, water features, commemorative landscapes and highly connected nodes emerge as pivotal visual-spatial factors that enhance visit frequency, whereas enclosed, compact and less accessible routes suppress visitation, thereby providing quantitative evidence for the spatial optimisation of heritage sites.

Memorial axis landscape–behaviour sequence analysis

The preceding results indicate that commemorative elements within the DFTC are strongly concentrated along the central axis; correspondingly, dwelling and movement hotspots likewise cluster around this axis and exhibit higher mean dwell times and visit frequencies. To clarify the landscape–behaviour coupling mechanism along this commemorative corridor, our previous study applied Ward’s hierarchical clustering followed by K-medoids optimisation to cluster all movement trajectories, thereby identifying the 'central-axis cluster routes'29. For these routes, landscape metrics and displacement sequences were matched node by node for comparative analysis, enabling the assessment of behavioural divergence at key intersections along the axis.

Figure 10 illustrates the behavioural distribution trends within the narrative space of the central axis, divided into four stages: introduction, development, transition and climax. Significant behavioural differences were observed between these stages. This narrative reflects the garden’s overall spatial organisation and central‐axis progression, with landscape prominence increasing steadily to a climax (Fig. 10b, c)2. Specifically, during the introduction stage, the visit frequency and dwell time were relatively high, indicating an exploratory phase for visitors. During the development stage, the behaviours stabilised. In the transition stage, there was a notable shift, with an increase in visit frequency and a decrease in dwell time. In the climax stage, visit frequency and dwell time reach high levels. Overall, dwell and movement behaviour along the central axis followed a pattern of initial increase, decline and gradual recovery.

To evaluate the guiding effect of the central axis on visitor flow, four multi-direction nodes (6, 11, 13 and 17) were selected and outbound frequencies for each direction were enumerated (Fig. 10d). Assuming a null hypothesis of equal probabilities across directions, a χ² goodness-of-fit test was conducted. The χ² statistics for all nodes far exceeded the critical value (p < 0.001), indicating that movement choices at multi-direction junctions are strongly biased rather than random. The central-axis direction accounted for an average of 57.1% across the four nodes (44.5–68.5%), with node 13 (Fig. 10d: d-3) displaying the most pronounced bias (68.5%). Additional models controlling for road hierarchy, step depth and number of available directions produced non-significant coefficients, confirming that the commemorative vista corridor guides visitor flow independently of these infrastructural factors. Even when multiple feasible paths are available, more than half of the visitors still choose to continue along the commemorative corridor, underscoring its substantial guiding influence on movement direction.

To identify the key features of spatial variation along the central axis and conduct an in-depth comparison of dwell and movement behaviour outcomes, this study performed a visual analysis of various dimensional indicators of the central axis. In Fig. 11a, natural features (GVR, WBP and BSP) exhibit significant overall fluctuations, with the GVR gradually declining until it reaches its lowest point at the climax stage, reflecting a weakening of landscape naturality. In Fig. 11b, commemorativeness (VPCE, QDCE and CDCE) exhibits an overall upward trend, with VPCE gradually increasing to a relatively high value during the introduction and development stages, declining at the transition stage and sharply rising to its peak at the climax stage, indicating a progressively advancing emotional narrative structure. Complexity (SE, SC and FD) decreased from a high value in the introduction stage, gradually increased in the development stage, reached a relatively high value at the transition stage and stabilised at the climax stage to sustain heightened visitor emotions. The visual scale (CD, SO, and SpE) exhibited pronounced fluctuations during the introduction stage and gradually stabilised in the subsequent stages. The B-C-S triad of colour metrics exhibits a staggered ‘high–low–rebound’ pattern along the spatial sequence: B and C co-dominate the prologue and transitional scenes, high S performs chromatic rendering during the development phase, whereas the climax achieves emotional closure and visual depth through a renewed rise in C accompanied by reduced B.

a Naturalness, b commemorativeness, c complexity, d visual scale and e colour. Note: Curves show the variation of each feature along the central axis; the x-axis denotes position IDs along the axis (as labelled). The ID positions follow those in Fig. 10, and the left-to-right direction corresponds to the central-axis direction. All data have been normalised and processed using Gaussian smoothing.

Commemorative, complexity and colour categories each follow a progressive trajectory, peaking predominantly in the development-transition segment and thereafter fluctuating at elevated levels; their overall rhythm closely parallels the narrative segmentation. Among these, commemorative metrics exhibit the strongest synchrony with dwell-movement behaviour and appear to be a primary factor associated with behavioural tempo. The five groups of visual-spatial metrics form an offset-alternating synergy: base colour channels underpin the prologue and epilogue; spatial morphology accumulates rapidly in the mid-section, generating a strong perceptual impact; and commemorative elements are accentuated at key nodes and, in the climax, balance visual layering with emotional experience.

Discussion

Water features had a pronounced positive impact on both dwell duration and visit frequency. First, as a key scenic element in traditional Chinese gardens, water features add cultural richness, thereby enhancing the spatial appeal and aiding in value interpretation1,4 Second, water features play a crucial role in spatial segmentation, visual guidance and pathway organisation, serving as visual focal points and spatial nodes that encourage visitor movement and interaction42. Additionally, water features contribute to physical and psychological well-being43,44, fostering favourable perceptual behaviours.

In contrast, while urban studies have suggested that green spaces have positive effects45, this study found that their influence within heritage contexts is comparatively limited, with a distinct difference in their impact on dwell duration and movement behaviour. A high green-view index correlates negatively with dwell time, implying that excessive vegetative coverage can diminish the cultural experience. This observation aligns with Zhang et al.’s31 ‘tree-openness combination’ concept and with Teixeira CFB et al.’s46 claim that vegetation configuration is more consequential than its total amount. Accordingly, the green-view index has interpretive value only when analysed alongside complementary metrics; it cannot serve as a reliable standalone indicator. Within commemorative zones of classical gardens, the restorative benefits offered by natural substrates are modulated by the site’s narrative framework47, producing an ‘optimal-moderation’ rather than a linear-accumulation pattern—an effect that elucidates the negative correlation between the green-view index and dwell time.

Synergistic benefits between commemorative attributes and waterscapes were evident. WBP and VPCE exerted significant positive effects on dwell time and visit frequency, thereby confirming the 'substrate–symbol' coupling model, in which water provides a natural substrate for emotional restoration and commemorative symbols are reinforced by their reflections on the water surface6. Their combination forms a behavioural sequence—'easy to arrive, willing to stay, eager to return'—demonstrating that ecological comfort and cultural memory amplify one another rather than substitute each other.

Commemorativeness exerted multidimensional correlational effects. The coefficient for commemorative category diversity was negative for dwell time but positive for visit frequency and an increase in SE further intensified this negative effect. Our results reveal a characteristic information-load threshold: when symbol density is moderate, visitors explore a wider variety of commemorative elements; however, once categorical and background heterogeneity jointly exceed this threshold, cognitive costs surge, leading visitors to move on after a brief stay14,48. Accordingly, the relationship between commemorativeness and behaviour comprises two dimensions: in the visibility-share dimension, a greater share of commemorative elements in the visual field increases both dwell time and visit frequency; in the complexity dimension, attraction operates only within the threshold, whereas excessive complexity dilutes narrative cues and encourages movement49. Therefore, commemorative landscape design must balance symbolic richness and narrative coherence, avoiding scattered elements that undermine spatial cohesion.

In previous studies, spatial infrastructure metrics—such as road hierarchy, spatial depth and node degree—have been regarded as key determinants of visitor behaviour50,51,52; however, commemorativeness has emerged as the potential dominant correlational factor in the present study. This consensus persists—road level (β = −0.07, p < 0.001) and step depth (β = −0.013, p < 0.001) significantly reduce dwell time, while node degree (β = 0.297, p < 0.001) increases visit frequency. However, commemorativeness continues to dominate overall effects: VPCE (β = 6.947, p = 0.012) and CDCE (β = 0.261, p < 0.001) exerted positive influences on visit frequency comparable to node degree and VPCE’s effect on dwell time (β = 1.812, p < 0.001) and CDCE’s suppressive effect (β = −0.063, p < 0.001) on average exceeded those of infrastructural variables. Socio‐demographic factors influenced only visitation likelihood (e.g. lower female proportions and higher frequencies among local and repeat visitors), with negligible impact on dwell time. Thus, under comparable conditions, the commemorative dimension more effectively explains visitor motivation and immersive experiences, underscoring a 'low-cost accessibility + high emotional value' dual-drive strategy. While preserving accessibility, designers should prioritise optimising commemorative sightlines and nodal rest points to simultaneously enhance visitation efficiency and dwell quality.

Ancient Chinese architecture is characterised by successive axial courtyard layouts. Guo et al. identified that the central-axis heritage zone of Xishu Gardens exhibits a spatial sequence of 'initiation—continuation—transition—conclusion'2,49. This study further reveals that commemorativeness at the DFTC is manifested in its physical spatial form and exerts significant driving and aggregating effects on human–garden interactions. Specifically, the central axis accumulates the highest dwell times, visit frequencies and commemorative density, forming the core tour zone. A four-stage rhythm—scene-setting, development, turning, climax—emerges along the axis38. Upon entering, visitors pause; they then proceed steadily before briefly accelerating and ultimately reconverging at the commemorative climax. Stepwise increases in commemorative metrics (VPCE, QDCE, CDCE) are highly synchronised with this 'pause—move—pause' behavioural rhythm, indicating that symbol density drives emotional progression and enhances spatial stickiness. These results validate the 'contextual unfolding–symbol reinforcement' mechanism, underscoring the commemorative landscape’s central guiding role along the axis in directing visitor flow and rhythm.

Based on significant multidimensional metrics, this study proposes three plausible coupling relationships: positive core pairs, negative risk pairs and complementary pairs. First, the positive core pair (WBP × VPCE) simultaneously enhances dwell time and repeat visits, constituting a key combination for creating highly cohesive landscapes. Second, the negative risk pair (SpE × S) suppresses both behaviours and should be avoided in design. Third, the complementary pair (SpE↔C) indicates that light and shadow layering can partially mitigate the adverse effects of high enclosure. From a planning and implementation perspective, waterfront commemorative composite nodes should be prioritised as 'dual-effect cores.' In highly enclosed segments, visitor experience can be enhanced by expanding view corridors, controlling saturation levels and emphasising light–dark layering. Meanwhile, entrances and transition zones can leverage diverse element categories to attract flow, whereas core areas should emphasise a coherent narrative to prolong dwell times.

In summary, using a visual-feature model, this study identified significant correlations between visitor dwell and movement behaviours and landscape spatial characteristics. Among these variables, water features and the visible proportion of commemorative elements exhibited the strongest correlations and, alongside naturalness, commemorativeness, complexity, visual scale and colour, constituted a comprehensive five-dimensional relationship. Within the central-axis space, the pronounced visibility of commemorative elements and the axial narrative rhythm manifested as a distinct sequential order. By quantifying the visual characteristics of Xishu Gardens’ heritage spaces and visitor dwell and movement behaviours, this study provides empirical support for deep perceptual design concepts in classical gardens and offers strategic guidance for heritage management and landscape renewal. Under the principle of sustainable use, commemorative imagery and water experiences should remain visible and accessible; spatial complexity should be moderated to foster a balance between dynamism and tranquility; and heritage value should be preserved for long-term perpetuation.

Despite its theoretical and methodological contributions, this study has several limitations: First, our sample consisted primarily of students, experts and practitioners in related fields, which may not fully reflect the behavioural patterns of general visitors from diverse backgrounds and varied interests. Future research should therefore employ stratified sampling by visitor type or cultural background to enable more detailed analyses, thereby enhancing the generalisability and applicability of the results. Second, while the online experiment effectively validated the critical role of visual features in behaviour via efficient visual simulation, it did not include multisensory interactions—auditory, olfactory, or haptic stimuli—which may have resulted in underestimating dwell time. Future studies should integrate multisensory environmental simulations—balancing auditory, olfactory and haptic stimuli—while maintaining methodological feasibility, to quantify their combined effects on behaviour. Finally, virtual tours in this study were conducted using a desktop simulation system, which facilitated controlled large-scale data collection but lacked immersion and authenticity. Future research should adopt VR experimental designs to enhance situational presence and simultaneously collect eye-tracking data, directional change metrics and physiological measures. These methods will enrich micro-behavioural analyses, validate current findings and, given their correlational nature, investigate causal pathways via controlled or longitudinal studies.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Peng, Y. Analysis of Chinese Classical Gardens (China Architecture & Building Press, 1986).

Guo, L., Xu, J., Li, J. & Zhu, Z. Digital preservation of Du Fu Thatched Cottage Memorial Garden. Sustainability 15, 1359 (2023).

Chen, H. & Yang, L. Analysis of narrative space in the Chinese classical garden based on narratology and space syntax—taking the Humble Administrator’s Garden as an example. Sustainability 15, 12232 (2023).

Wei, C., Yu, M., Liu, F., Chen, M. & Zhang, Q. Heritage value identification and evaluation of Xishu Celebrity Memorial Garden. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 39, 127–132 (2023).

Baldassare, M. Human spatial behavior. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 4, 29–56 (1978).

Riungu, G. K., Peterson, B. A., Beeco, J. A. & Brown, G. Understanding visitors’ spatial behavior: a review of spatial applications in parks. Tour. Geogr. 20, 833–857 (2018).

Lee, Y. & Kim, S. Visitors’ consistent stay behavior patterns within free-roaming scenic architectural complexes: considering impacts of temporal, spatial, and environmental factors. Landsc. Urban Plan. 207, 104021 (2021).

Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space (Island Press, 2011).

Shi, H., Huang, H., Ma, D., Chen, L. & Zhao, M. Capturing urban recreational hotspots from GPS data: a new framework in the lens of spatial heterogeneity. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 103, 101972 (2023).

Xu, G., Zhong, L., Wu, F., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Z. Impacts of micro-scale built environment features on tourists’ walking behaviors in historic streets: insights from Wudaoying Hutong, China. Buildings 12, 2248 (2022).

Dong, W., Kang, Q., Wang, G., Zhang, B. & Liu, P. Spatiotemporal behavior pattern differentiation and preference identification of tourists from the perspective of ecotourism destination based on the tourism digital footprint data. PLoS ONE 18, e0285192 (2023).

Ye, Y., Qiu, H. & Jia, Y. Understanding factors affecting tourist distribution in urban national parks based on big data and machine learning. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 150, 04024021 (2024).

Yao, Q. et al. Understanding the tourists’ spatio-temporal behavior using open GPS trajectory data: a case study of Yuanmingyuan Park (Beijing, China). Sustainability 13, 94 (2020).

Wang, L. & Huang, W. Visitors’ consistent stay behavior patterns within free-roaming scenic architectural complexes: considering impacts of temporal, spatial, and environmental factors. Front. Archit. Res. 13, 990–1008 (2024).

Xiao-Ting, H. & Bi-Hu, W. Intra-attraction tourist spatial-temporal behavior patterns. Tour. Geogr. 14, 625–645 (2012).

Liu, W. et al. Cluster analysis of microscopic spatio-temporal patterns of tourists’ movement behaviors in mountainous scenic areas using open GPS-trajectory data. Tour. Manag. 93, 104614 (2022).

Chen, H. & Yang, L. Spatio-temporal experience of tour routes in the Humble Administrator’s Garden based on isovist analysis. Sustainability 15, 12570 (2023).

Centorrino, P., Corbetta, A., Cristiani, E. & Onofri, E. Managing crowded museums: visitor flow measurement, analysis, modeling, and optimization. J. Comput. Sci. 53, 101357 (2021).

Zheng, X. et al. Two-stage greedy algorithm based on crowd sensing for tour route recommendation. Appl. Soft Comput. 153, 111260 (2024).

Zheng, W. & Liao, Z. Using a heuristic approach to design personalized tour routes for heterogeneous tourist groups. Tour. Manag. 72, 313–325 (2019).

Grahn, P. & Stigsdotter, U. K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 94, 264–275 (2010).

Qi, J. et al. Development and application of 3D spatial metrics using point clouds for landscape visual quality assessment. Landsc. Urban Plan. 228, 104585 (2022).

Zhang, X., Lin, E. S., Tan, P. Y., Qi, J. & Waykool, R. Assessment of visual landscape quality of urban green spaces using image-based metrics derived from perceived sensory dimensions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 102, 107200 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. A novel method of urban landscape perception based on biological vision process. Landsc. Urban Plan. 254, 105246 (2025).

Shen, C. & Yu, C. The virtual-real measurement of Chinese garden impression: a quantitative analysis of cognitive experience of Jiangnan gardens with virtual reality experiments. Front. Archit. Res. 13, 895–911 (2024).

Li, R. & Klippel, A. Wayfinding behaviors in complex buildings: the impact of environmental legibility and familiarity. Environ. Behav. 48, 482–510 (2016).

Liang, H. et al. The integration of terrestrial laser scanning and terrestrial and unmanned aerial vehicle digital photogrammetry for the documentation of Chinese classical gardens–a case study of Huanxiu Shanzhuang, Suzhou, China. J. Cult. Herit. 33, 222–230 (2018).

Huang, W. & Wang, L. Towards big data behavioral analysis: rethinking GPS trajectory mining approaches from geographic, semantic, and quantitative perspectives. Archit. Intell. 1, 7 (2022).

Gong, X. et al. Perceptual-preference-based touring routes in Xishu gardens using panoramic digital-twin modeling. Land 14, 932 (2025).

Song, H., Chen, J. & Li, P. Decoding the cultural heritage tourism landscape and visitor crowding behavior from the multidimensional embodied perspective: insights from Chinese classical gardens. Tour. Manag. 110, 105180 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Beyond just green: Explaining and predicting restorative potential of urban landscapes using panorama-based metrics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 247, 105044 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. An interpretable machine learning framework for measuring urban perceptions from panoramic street view images. iScience 26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106132 (2023).

Li, J. et al. An estimation method for multidimensional urban street walkability based on panoramic semantic segmentation and domain adaptation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 136, 108905 (2024).

Dang, X., Liu, W., Hong, Q., Wang, Y. & Chen, X. Digital twin applications on cultural world heritage sites in China: a state-of-the-art overview. J. Cult. Herit. 64, 228–243 (2023).

YiFei, L. & Othman, M. K. Investigating the behavioural intentions of museum visitors towards VR: a systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 108, 167 (2024).

Li, J., Zheng, X., Watanabe, I. & Ochiai, Y. A systematic review of digital transformation technologies in museum exhibition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 108, 407 (2024).

Li, Y., Yabuki, N. & Fukuda, T. Measuring visual walkability perception using panoramic street view images, virtual reality, and deep learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 86, 104140 (2022).

Xu, J. Digital Conservation and Application of Du Fu Thatched Cottage, a Memorial Garden of Historical and Cultural Celebrities in Western Sichuan. Ph.D. dissertation (Sichuan Agricultural University, 2024).

Yu, X. & Xu, H. Ancient poetry in contemporary Chinese tourism. Tour. Manag. 54, 393–403 (2016).

Editorial Committee of Research on the Xishu Classical Garden. Research on the Xishu Classical Garden (Sichuan Publishing House of Science & Technology, 2024).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 4015–4026 (IEEE, 2023).

Kaplan, S. Aesthetics, affect, and cognition: environmental preference from an evolutionary perspective. Environ. Behav. 19, 3–32 (1987).

White, M. et al. Blue space: the importance of water for preference, affect, and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 30, 482–493 (2010).

Guo, L. et al. Multisensory health and well-being of Chinese classical gardens: insights from Humble Administrator’s Garden. Land 14, 317 (2025).

Yin, J. et al. Effects of blue space exposure in urban and natural environments on psychological and physiological responses: a within-subject experiment. Urban For. Urban Green. 87, 128066 (2023).

TTeixeira, C. F. B. Green space configuration and its impact on human behavior and urban environments. Urban Clim. 35, 100746 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Jiang, M. & Zhao, J. The restorative effects of unique green space design: comparing the restorative quality of classical Chinese gardens and modern urban parks. Forests 15, 1611 (2024).

Guan, F. et al. Modelling people’s perceived scene complexity of real-world environments using street-view panoramas and open geodata. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 186, 315–331 (2022).

Guo, L. et al. Digital preservation of classical gardens at the San Su Shrine. Herit. Sci. 12, 66 (2024).

Hillier, B. & Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space (Cambridge University Press, 1984).

Hillier, B., Penn, A., Hanson, J., Grajewski, T. & Xu, J. Natural movement: or, configuration and attraction in urban pedestrian movement. Environ. Plann. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 20, 29–66 (1993).

Lyu, Y. et al. Multi-data driven and space syntax approach to urban heritage revitalization: insights from Zhongshan Rd. Historic District, China. Ain Shams Eng. J. 16, 103473 (2025).

Peng, Y., Zhang, G., Nijhuis, S., Agugiaro, G. & Stoter, J. E. Towards a framework for point-cloud-based visual analysis of historic gardens: Jichang Garden as a case study. Urban For. Urban Green. 91, 128159 (2024).

Wang, Y., Cheng, Y., Zlatanova, S. & Chenget, S. Quantitative analysis method of the organizational characteristics and typical types of landscape spatial sequences applied with a 3D point cloud model. Land 13, 770 (2024).

Yu, R. & Ostwald, M. J. Spatio-visual experience of movement through the Yuyuan Garden: a computational analysis based on isovists and visibility graphs. Front. Archit. Res. 7, 497–509 (2018).

Lu, L. & Liu, M. Exploring a spatial-experiential structure within the Chinese literati garden: the Master of the Nets Garden as a case study. Front. Archit. Res. 12, 923–946 (2023).

Chen, Y., Gu, Y., Liu, Y. & Cao, L. Unveiling the dynamics of “scenes changing as steps move” in a Chinese classical garden: a case study of Jingxinzhai Garden. Herit. Sci. 12, 131 (2024).

Chen, X., Yu, H., Xiong, R. & Ye, Y. Construction of an analytical framework for spatial indicator of Chinese classical gardens based on space syntax and machine learning. Landsc. Archit. 31, 123–131 (2024).

Zhang, T., Liu, B., Zhu, Z. & Feng, M. The spatio-temporal perception formation mechanism of the “view changes with step movements” in the Master of the Nets Garden. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 39, 22–28 (2023).

Ki, D. & Lee, S. Analyzing the effects of Green View Index of neighborhood streets on walking time using Google Street View and deep learning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 205, 103920 (2021).

Neupane, B., Horanont, T. & Aryal, J. Deep learning-based semantic segmentation of urban features in satellite images: a review and meta-analysis. Remote Sens. 13, 808 (2021).

Brevik, E. C. et al. The interdisciplinary nature of SOIL. Soil 1, 117–129 (2015).

Fang, Y. N., Zeng, J. & Namaiti, A. Landscape visual sensitivity assessment of historic districts—a case study of Wudadao historic district in Tianjin, China. ISPRS Int. J. GeoInfo. 10, 175 (2021).

He, Q., Larkham, P. & Wu, J. Evaluating historic preservation zoning using a landscape approach. Land Use Policy 109, 105737 (2021).

Fairclough, G. Cultural Landscape, Sustainability, and Living with Change? Perspectives from Europe. in Managing Change: Sustainable Approaches to the Conservation of the Built Environment 23–46 (The Getty Conservation Institute, 2002).

Batty, M. & Longley, P. A. Fractal Cities: A Geometry of Form and Function (Academic Press, 1994).

McGarigal, K. FRAGSTATS: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Quantifying Landscape Structure, Vol. 351 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 1995).

Sreenu, G. & Durai, S. Intelligent video surveillance: a review through deep learning techniques for crowd analysis. J. Big Data 6, 1–27 (2019).

Yang, J., Zhao, L., Mcbride, J. & Gong, P. Can you see green? Assessing the visibility of urban forests in cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 91, 97–104 (2009).

Ewing, R. H. et al. Measuring Urban Design: Metrics for Livable Places, Vol. 200 (Island Press, 2013).

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to the DFTC Museum for their support. Special thanks to Manqing Yao for reviewing and proofreading the manuscript. We also acknowledge the contributions of Chenjing He, Yuanxiang Huang, Qiuyan Han, and Yujie Huang in the data collection process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Q.G. conceptualised the study, designed the methodology, collected and analysed the data, and was responsible for software development, investigation, data curation/validation, visualisation, project administration, and wrote the original draft (lead author). L.G. contributed to data collection, supervision, and secured funding for the study. Z.Y.Z. provided resources, contributed to data collection, and was involved in writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript, along with supervision. J.L. participated in data collection and supervision. D.S.Z. assisted in writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript, and provided supervision. J.X. contributed to data collection, point cloud data acquisition, and was involved in writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript. W.Y. participated in the investigation and software development. Y.J.Z. and M.J.L. both contributed to data collection and visualisation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, X., Guo, L., Zhu, Z. et al. Influence of visual landscape on dwell and movement behaviours in Du Fu Thatched Cottage. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 442 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01932-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01932-3