Abstract

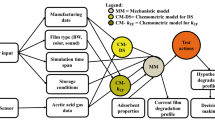

Cinematographic film materials with a base material on cellulose acetate and its derivates are known for becoming brittle and fragile due to various inhomogeneous material ageing processes during long-term storage. Physical phenomena have a significant influence on the ageing behaviour of cinematographic film materials stored over long time on a film roll, with a certain tension and pressure. Storage conditions, such as temperature and humidity and heavy variations thereof, as well as the different pressure distributions inside a film pack, strongly influence evaporation of plasticizers and other volatile substances. Nanoindentation was performed with naturally aged samples on different parts of the film roll to study these effects in depth. This knowledge provides new insight into the aging mechanisms of cellulose acetate substrates, providing details of the differences in loss and distribution of plasticizers and thus different material properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage artefacts, such as cinematographic film materials based on cellulose acetate (CA) and its derivatives, are suffering from chemical deterioration processes, which on one hand can be summarized as the 'vinegar syndrome', well described in literature (e.g.1,2,3 and several others). On the other hand, a second effect, which may occur independently from the vinegar syndrome with several kinds of flexibilized plastics, is plasticizer loss. Flexibilized plastics often tend to lose the plasticizer through evaporation, migration, extraction or accumulation of the plasticizer on the surface. These processes, as well as oxidative degradation in the polymer/plasticizer system as described in refs. 4,5,6,7 lead to a gradual embrittlement of the material. A typical problem in heavily aged CA-based materials, such as those often found in film and audiovisual archives, is the combination of vinegar syndrome and plasticizer loss: deacetylation of CA accelerates the migration of plasticizers through the accompanying chain scission. The plasticizer migration thus takes place alongside with the deacetylation of CA. However, the relative speed, significance, and impact of this process have so far not yet been sufficiently researched, especially for photographic and audio-visual media8. Plasticizer loss significantly diminishes the mechanical properties of cultural heritage objects, which in the case of cinematographic film materials or magnetic tapes based on CA and its derivatives, can lead to their brittleness, shrinkage, and hardening. In the worst case, the medium cannot be handled or digitized anymore, resulting in material breakdown up to total loss. The role and function of plasticizers in audio-visual media have been basically described in ref. 9. The general mechanisms of plasticiser loss due to evaporation and migration have been studied already very early4,6,10,11, but only occasionally regarding cultural heritage artefacts in museums and collections5,6,12,13.

For decades, spectroscopy methods, such as Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) spectroscopy, or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), have been used to study the aging of cellulose acetate successfully. In ref. 1 the artificial and natural degradation of cellulose triacetate (CTA), base motion picture film material, has been studied using viscometry and infrared spectroscopy analysis. In refs. 14,15 the degradation of CTA by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and molecular modelling was investigated. However, the authors do not consider the effect of additives to CTA support.

Spectroscopic methods, such as infrared spectroscopy (FTIR and ATR), are well suitable for chemically characterizing the top surfaces of film materials. But due the fact that ATR spectroscopy is a surface sensitive technique, probing reaches only to a depth of ca. 1–3 μm into the sample when choosing a diamond crystal with a typical spectral range between 7000 and 350 cm−1. In transmission FTIR, sample thickness typically needs to be quite thin, around 10–50 µm, to allow sufficient infrared light to pass through. Therefore, when using transmission FTIR method, either the gelatine (image) layer or the anti-curl layer must be removed, as otherwise the total thickness of a cinematographic film is too high for transmission studies (in the range between ca. 120–200 µm, such as for photographic plan film 170–200 μm, roll film: 90–100 μm, cinema film: 115–130 μm16). Previous studies using ATR spectroscopy also reported on the inability of the technique to detect the film base, particularly if both sides of the film were coated in a layer containing gelatine15,17. Nevertheless, using spectroscopic methods, punctual plasticiser concentration can be measured and analysed, but the method does not give an indication concerning overall elasticity (stiffness) of the material.

As audio-visual media, such as magnetic tapes and cinematographic film materials are machine readable documents, the content can only be accessed if the material is played back with an appropriate device, e.g. a projector, film scanner or a tape machine. Therefore, the material must have minimum mechanical properties to allow high signal quality in order to prevent physical material damage. While for cinema projection these values are standardized18, a film scanner typically can work with minimum film tension in the range of 20 grams /0.2 Newton. Assessing mechanical behaviour, especially of audio-visual media with a base material of CA and its derivatives, has recently been studied in ref. 5 by correlating the results of uniaxial tensile strain at failure and flexural modulus determined with 3-point bending with thermogravimetric weight loss curves for artificially aged samples. The results of this study show the relation between brittle behaviour and the plasticizer content, which was monitored using thermogravimetric analysis and FTIR spectroscopy. It was also outlined that for archival film, the distribution of internal stress in the wound roll is key to enabling safe handling of film material, which makes the hardening capacity a measure of a material’s physical stability. The results also highlighted the possibility of applying micro-analytical techniques for condition monitoring of artifacts.

Another method that has been used in the heritage sciences19 to quickly evaluate the mechanical behaviour of plastic is the Shore A hardness20,21. Using a Durometer, the Shore A hardness has been used to measure the hardness of polymeric materials (~6 mm thick). Shore hardness uses a scale of 0–100 to qualify the hardness of plastic materials22. Previous studies have correlated an increase in Shore A hardness with a reduction in flexibility23. However, Shore A indents are quite large, almost 1 mm in diameter, with indent depths in the range of 1–2.5 mm. These large-scale measurements may not be satisfactory for thin cinematographic films which are less than 1 mm thick, as outlined above. The elastic zone under an indent is quite large, and why the need for a 6 mm thick sample for valid results. Recently, the plastic and elastic zones under a 300 nm radius indentation tip were simulated with finite elements for indents made into a 2 µm thick Mo film on silicon24. From comparisons with experiments, the elastic zone was found to be 15 times larger than the plastic zone. The resulting elastic modulus measurements were closer to the silicon substrate than the Mo film. Such a result illustrates that the total thickness of the sample, indented with any method, is an influencing factor and requires consideration. If Shore A hardness measurements are taken on samples less than 6 mm thick, as the standard states is the minimum thickness, the measurement is erroneous.

Flexibility can also be termed stiffness in the field of materials science and can be quantified with the elastic modulus, E, of a material. In the field of materials science, the mechanical behaviour of materials can be measured using a variety of indentation methods that range in scale from the macro to the nano regimes. Taking up these approaches, we propose nanoindentation as a highly suitable method to quantify the elastic properties and hardness of the CA substrates, enabling probing into the depths between hundreds of nanometres to several micrometres. Moreover, nanoindentation can be applied on prepared cross-sections to map the mechanical properties through the full thickness of the CA substrate without having adverse effects from the gelatine layer or the need to remove layers to achieve deeper depths. This way the local mechanical properties of the CA layer can be obtained with a micrometre spatial resolution through the thickness, providing an overview of the changes in CA stiffness not only as a function of external loading (e.g. position on the film roll or tightness of the wounding), but also as a function of the position within the film.

Over that last 30 years, nanoindentation, also called depth sensing indentation (DSI), has gained in popularity as a versatile method to measure mechanical properties of materials. Furthermore, it is a sophisticated method to measure local hardness and elastic modulus with micrometre resolution. The technique is also considered non-destructive since the area of deformed materials is in the range of 1–2 µm2 from the indenting surface depending on the indentation parameters25,26,27. DSI records the actual load and displacement of a diamond tip when it is pressed into a material. The load-displacement (P-δ) curve is a fingerprint of the material behaviour as it describes the initially elastic-plastic material response during loading of the tip as well as the elastic response from the unloading of the tip. In 1992, Oliver and Pharr28,29 determined that when the shape of the diamond tip is well-known through a simple calibration routine, the unloading portion of the load-displacement curve can be used to measure the elastic modulus of the material and the size of the remaining indent imprint can be used to measure the hardness. Additionally, new indentation mapping techniques allow the use of many indents in a fast pace to describe the mechanical properties of hardness and elastic modulus spatially in order to better visualize how material behaviour may be affected locally30. Such a technique allows mapping of cross-sections of CA films with good resolution as well as providing more data for statistics. Nanoindentation has also be utilized in the heritage sciences for various applications31,32,33.

For polymeric materials, the elastic modulus can be more sensitive to small changes due to chemistry or environmental effects and is a better indication of a materials stiffness, thus, flexibility. The general definition of elastic modulus is the measure of a material’s resistance to being deformed elastically and hardness is defined as a material’s resistance to localized plastic deformation. Therefore, hardness, the amount of localized plastic deformation measured with Shore A, is not the material property that should be measured to determine if CA in cinematographic films is still flexible enough for being processed in a machine, for example, for playback, viewing, digitization, etc. Additionally, the size of Shore A indent is too large to resolve any changes through the substrate thickness due to degradation mechanisms. Hardness should not be confused with ductility, which is defined as the amount of plastic deformation that has been sustained at fracture34. Hardness tests do not generally induce fracture, especially in polymeric materials. Elastic modulus is also more sensitive to changes in chemistry in materials, including polymers, and, as previously stated, directly related to the stiffness of a material, thus flexibility necessary for playback.

The aim of this study is to demonstrate that nanoindentation can be used as a tool in heritage science, specifically on the aging of cinematographic films. CA, a common substrate found in cinematographic films, ages to the point where the substrate becomes too stiff and brittle to allow viewing. The aging of CA is a multistep and inhomogeneous process through the substrate thickness (cross-section) that can be confirmed with nanoindentation methods. By tracking the elastic modulus of the substrate, the aging process can be studied in-depth and efforts to rejuvenate CA will benefit from the higher resolution mechanical property measurement method. Therefore, the research question that is the focus is: Using a small set of samples, can nanoindentation be applied on cross-sections of CA aged films and initial trends be observed to establish nanoindentation as a method to further study vinegar syndrome and/or the loss of plasticizer theories with quantitative mechanical property measurements of hardness and elastic modulus.

Methods

Description of the cinematographic films studied

The samples (hereby named A1–A3, detailed in Table 1) used for this study were chosen according to their physical condition (elasticity, signs of brittleness) and stage of deterioration, respectively vinegar syndrome. Detailed storage conditions of the samples are unknown, but according to their origin (private collections), it can be assumed that they were stored under access conditions (ca. 20°C, 40% RH) in their original containers (non-ventilated, light-proof metal film cans). The severity of the vinegar syndrome was measured by following the well establishes approach of measurement by means of AD strips, developed by the image permanence institute35. The material was also classified by optical and manual inspection of experienced film archivists. Additionally, samples A2 and A3 were examined by several methods following Nunes et al.19, as they were molecularly characterized by µFTIR or ATR-FTIR regarding the identification of the plasticizer Triphenyl phosphate (TPP), and the correspondent conservation state was accessed by the determination of their degree of substitution (DS). As hydrolysis is the fundamental degradation mechanism for CA materials, the conservation condition of the cinematographic film supports (substrates) may be correlated to their degree of substitution. In their study, the authors propose the use of the cellulose triacetate DS interval 2.9–3 as the ‘original’ DS for the samples that presented values ranging from DS 2.69 to 2.83. The lower DS in relation to the ‘original’ DS is indicative of degradation19. The measurements and chemical characterization of the samples chosen have been performed within the context of the European Union Horizon 2020 research project NEMOSINE: Innovative packaging solutions for storage and conservation of 20th century cultural heritage of artefacts based on cellulose derivatives, 2028–2020.

Cross-section preparation and Shore A hardness procedure

In order to properly indent the cinematographic films, cross-sections of the samples were made. Samples were cut from the film roll perpendicular to the rolling direction and clamped between two pre-made epoxy plates (Fig. 1a, b). The plates were held in place with polymer spring clamps and an additional metal clamp was added to add weight and prevent the sample from floating during the curing of the embedding epoxy resin. After properly curing the epoxy, a water-free grinding and polishing method was developed and used. First, the embedded cross-sectional samples were ground down to 1200 grit SiC sanding paper using a 3:1 ethanol—glycerine solution. The grinding step was followed by three polishing steps using gradually finer polishing suspensions (Struers) on an automatic polishing system with a 20 N load for durations of 3 min and 2 min, respectively, for diamond suspensions of 3 µm and 1 µm. The final polishing step used 0.5 µm Al2O3 suspension with Ethandiol for 3 minutes using a 20 N load on the automatic polishing machine. Between each step, water was briefly used to remove grinding or polishing residuals and then rinsed with 2-isopropanol (min 99.5%) for synthesis and dried under ventilation. From this careful preparation procedure, four cross-sections were prepared: A1 (slightly aged), A2 (aged), A3—Middle (highly aged), and A3—End (highly aged). Samples with A3 were taken more from the middle of roll or near the end of the roll (Fig. 1c) to illustrate possible differences along the position of the roll.

An initial characterization of the samples with a method used by archivists19, Shore A was applied. Often this method would be used to assess aging of films in storage. Shore A hardness measurement was performed on all of the cinematographic films and the embedding epoxy resin using a durometer. Five Shore A hardness indents were made on stacks of cinematographic films (~6 mm thick) and on the embedded cross-sections. Stacks of the films were used because a single layer would be significantly influenced by the underlying surface materials. Also, the ISO and ASTM standards state that the sample mush be 6 mm thick for a valid measurement. The embedding resin (~1.5 cm thick) was tested to have a reference value.

Nanoindentation was performed on the Bruker TS 77 Select nanoindentation system equipped with a 350 nm radius three-sided pyramid Berkovich diamond tip, shown in Fig. 2a. The tip area function, necessary to calculate the reduced elastic modulus, Er, and the hardness, H, was evaluated with 50 indents made into fused silica (Er = 69.9 GPa) from loads varying between 100 µN and 10,000 µN. Once the area function was determined, three different indentation experiments were performed. First, 25 indents (5 × 5 matrix with indents spaced 10 µm apart) were made into the embedding epoxy resin with a constant load on 2000 µN. These indents were made to have a reference for the epoxy resin for further comparison. A second set of indents with same maximal load was placed in the middle of the cross-sections of the cinematographic films to show the average values of the film (2 × 10 matrix, 10 µm indent spacing). Indents were made in the middle of the cross-sections again to have a reference of mechanical behaviour that is not affected by possible edge effects and to ensure differences can be measured due to the different amounts of aging. One larger matrix was performed across the film cross-sections to create a map of the measured hardness, H, and reduced elastic modulus, Er. The map (1000 µN maximum load) was 5 rows of 50 indents spaced 5 µm apart (250 total indents). For the A3 samples, additional maps were made due to the presence of delaminations, or cracks, in the CA substrate. The number of indents made is statistically relevant to provide quantitative trends about the aging of each sample studied. All samples were oriented to have the film (gelatine) side on the right of the cross-section. During the previous storage in the rolls, for A1 and A2, the film side was towards the inside of the roll, while on the A3 samples, the film side was at the outside of the roll.

After nanoindentation, the samples were examined with confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM), Olympus 4100 OLS LEXT system. All indents could be identified in all samples and in the A3R and A3M samples, delaminations running parallel to the gelatine film in the CA were observed, and will be discussed later.

Nanoindentation mechanics

From the load-displacement curves generated from each indent (Fig. 2b), the initial unloading slope is used to determine the reduced elastic modulus, Er. Oliver and Pharr28 determined that the initial unloading slope of the load-displacement curve could be described by a power law function. From the values determined from the power law fit and the calibrated tip area function, the reduced elastic modulus, Er, is measured:

where S is the stiffness (slope of initial unloading curve, dP/dδ, see Fig. 2b) and Ac is the contact area of the indent determined using the area function calibration of the tip. The reduced elastic modulus is influenced by the stiffness of the diamond tip and can be corrected with (Eq. 2):

with Ei,s the elastic modulus of the indenter tip (i) or specimen (s), and νi,s the Poisson’s ratio of the indenter tip (i) or specimen (s). For diamond, Ei and νi are well known (1170 GPa and 0.17, respectively28) and ν for many materials is assumed to be in the range of 0.25 to 0.3334. Since the Poisson’s ratio of polymers can vary significantly, it is best to compare the Er values rather than correct the Er values into Es values. Equation 3 is used to measure the hardness of a material:

with Pmax the maximum applied load during the indent. For more details about the mechanics behind nanoindentation, the reader is referred to the following references 27,28,29.

Results

Shore A hardness

All of the aged CA samples and the epoxy resin had an average value of 94–95. No difference between the three samples (A1-3) or the epoxy polymer resin was observed using Shore A hardness. Therefore, the method is not sensitive enough to distinguish the clear differences in aging and nanoindentation should be applied to gain further, more quantitative data on the mechanical behaviour of the aged CA films.

Nanoindentation

The initial comparison of the resulting hardness and reduced elastic modulus of the indents made in the embedding epoxy resin and the middle of the substrates (Table 2) illustrates why the reduced elastic modulus is more useful value to consider. If hardness values were to be used, there would be very little difference between the epoxy resin and the CA substrate. The epoxy resin has an average hardness over all four samples of 0.27 ± 0.01 GPa, while the hardness range of the cinematographic substrates is only slightly less, being between 0.21 and 0.25 GPa, see Table 2. These small values can only be resolved when nanoindentation methods are used. Additionally, Shore hardness could not distinguish such small differences between the two materials (epoxy and CA) nor the different aging stages, thus, DSI methods, such as nanoindentation, are advantageous. The reduced elastic modulus values from the different samples are consistent for the epoxy resin (4.3 ± 0.05 GPa) and vary for the different aging stages of the cinematographic substrates. It is noteworthy that the values of the CA substrates are significantly higher than the epoxy resin and this result allows for an in-depth examination of the aging. The increase in reduced elastic modulus also indicates that the chemistry of the CA is changing over time and that change increases the stiffness (decreases the flexibility) of the cinematographic samples.

A closer look at the measured hardness values using the indents made over the cross-sections is shown in Fig. 3 for all four cinematographic samples. The hardness values are plotted as a function of position along the X-coordinate of the indentation matrix with the cinematographic film being approximately in the centre of all graphs. In Fig. 3, each data point is one indent (250 total indents). Jumps or drops in the data generally correspond to the interfaces between the epoxy resin and sample or the gelatine layer as well as delaminations observed in the A3 samples (to be discussed later). There is not much difference in the hardness values measured for the A1 sample between the epoxy resin and sample (Fig. 3a). There is a hardness decrease near the middle of the substrate that matches the values shown in Table 2, that were also made in the middle of the sample. With more aging, A2 demonstrates hardness values that are lower than the epoxy resin and gradually decrease towards the film side (inside roll) of the substrate (Fig. 3b). With the highest amount of aging (Fig. 3c, d), the A3 samples also have a lower hardness than the epoxy resin as well as some gradients similar to A1 (lower in the middle of the sample). The average hardness value in the middle of the substrates is again similar to the values in Table 2 for A2 and A3-End. Interestingly, the hardness measured at the centre of A3-Middle is higher than Table 2, but is still lower than the epoxy measured at the same time (see indents between 0–50 µm and 200–250 µm Fig. 3c).

Hardness as a function of X-coordinate indents made across the cinematographic substrates a A1, b A2, c A3-Middle, d A3-End. The cinematographic substrates are approximately between 50-200 µm and oriented with the film side (gelatine) on the right of all graphs. Green X-shapes represent the indents into the CA substrate, blue circles are indents in the epoxy resin, and indents hitting the delaminations or edges are red hollow circles. Indenting across the substrates found gradients of hardness as well as the more highly aged samples have lower hardness values (Colour online).

From the same load-displacement curves that were used to evaluate the hardness, the reduced elastic modulus was also calculated. Figure 4 contains the reduced elastic modulus values as function of X-coordinate for the indents made over the sample cross-sections for the 250 indents made across the CA substrates. Since all maps were created across the whole CA substrate thickness and including the resin, for the better distinguishing between each material and more detailed analysis, colour and data point-shape distinction was used - green x-shapes represent the indents into the substrate and blue circles are indents into the embedding epoxy resin. Indents into the delaminated areas were excluded from the evaluation and are represented by the hollow red circles. Starting with the least aged A1 sample (Fig. 4a), a similar gradient in the substrate is observed as with hardness. The middle of the substrate has the lowest measured reduced elastic modulus at about 5.5 GPa. With more aging, the A2 sample does not have a large as a difference between the epoxy resin and the CA substrate, however, the same decreasing gradient toward the film side (inside roll) is visible (Fig. 4b). The A3-Middle sample (Fig. 4c) has several values that are quite high (approximately 7 GPa) near the first interface to the CA substrate, with the majority of the substrate having a small decreasing gradient towards the film side (outside roll). Recall that in the hardness results a decrease near the centre was observed (Fig. 3c) rather than a steady gradient. The average value of the reduced elastic modulus is about 5.6 GPa. At the end of the A3 roll (Fig. 4d) the highest reduced elastic modulus values were measured (~6.1 GPa). The A3-End sample also has additional drops in the data and these reflect delaminations observed throughout the prepared cross-section. The density of the delaminations was quite large and they could not be avoided. Similar delaminations were also observed in the A3-Middle sample, but not to the same extent, allowing delamination free measurements. The reduced elastic modulus values increase with increased aging and the increased elastic modulus could be the cause for the appearance of the delaminations and will be discussed later. The decrease of the reduced elastic modulus is more advanced towards the film side and the inside versus the outside of the roll does not appear to play a significant effect on reduced elastic modulus trends.

Reduced elastic modulus as a function of X-coordinate indents made across the cinematographic substrates a A1, b A2, c A3-middle, d A3-end. The cinematographic substrates are approximately between 50 and 200 µm and oriented with the film side (gelatine) on the right of all graphs. In general, the reduced elastic modulus increases with more aging. Green X-shapes represent the indents into the CA substrate, blue circles are indents in the epoxy resin, and indents hitting the delaminations or edges are red hollow circles (Colour online).

It should be noted that there is some scatter present in the results, mostly for the A3 samples. This scatter is a result of the indents being taken from a larger area mapping and plotted just as a function of one coordinate. In fact, if there are some irregularities (e.g. delaminations as in A3-End sample), some of the indents end at the edge of such places, but omitting one dimension shows them only as a scatter of the data. Therefore, a full visualization of the resulting H and Er as a function of the two coordinates (material property maps) shows more insight into the small changes in the stiffness of the samples.

While visualizing the indentation as 2D graphs allows for direct comparisons and some general trends to be observed, depicting the indentation data as maps provides another perspective, as mentioned in a note above Fig. 4. Figures 5–8 illustrate an image of the 250 indents made over each CA cross-section with reduced elastic modulus and hardness maps for all four samples under investigation. Again, the same data as in Figs. 3, 4 are shown in the Figs. 5–8, but in a spatial view. The colour scales are similar, but not exactly the same in all the maps. Recall that all of the cross-sections were arranged with the film (gelatine) side to be on the right and for A1 and A2 the film and the inside of the roll are the same, but for the A3 samples, the film side is the outside of the roll. At first, look on the different maps in Figs. 5–8, one recognizes that the reduced elastic modulus maps provide more local details compared to the hardness maps and that with more aging (A3 samples—Figs. 7, 8) delaminations are properly accounted for in the maps. Additionally, the aging of the cinematographic films is inhomogeneous, both through the thickness of the substrate as well as along the width of the substrate (20 µm the map covers). In Fig. 6a, fine straight lines in the CLSM laser intensity image indicated by arrows could be the start of delaminations. The reduced elastic modulus values around these fine lines vary more than further away, however, more work is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Discussion

As clearly presented in the Results section, with more aging the material mechanical properties, especially the reduced elastic modulus, change in the CA substrate. The change in mechanical behaviour is believed to be caused by the loss of plasticizer the well-known vinegar syndrome5,6. The differences in the reduced elastic modulus and hardness are not only observed from the inside to the outside of the roll, but also within the roll itself (compare A3-Middle and A3-End). The data from the maps (Figs. 5–8) provide evidence that the reduced elastic modulus changes with aging and that across the substrate, the aging is initially inhomogeneous (A1 and A2). What is clearly observed is that during the early stages of aging, the reduced elastic modulus values vary slightly across the thickness of the CA substrate. This stage could be the best time to start further preservation activities, such as de-shrinking and rejuvenation procedures methods, as described in refs. 7,9,36. They include procedures such as exposing a shrunken roll of film to a special atmosphere of either high humidity or a combination of various chemicals, e.g. solvents and plasticizers in a closed metal container or in a reduced pressure container in a warm place7. In refs. 9,36 a method to rejuvenate the material in the liquid phase is described, which also reduces the acidity content of the material by washing out acetic acid and replacing it with plasticizers. Such treatments ideally should be followed by copying or digitization, to avoid or at least slow down further aging phenomena of the material. At a later stage of aging, such as in samples A3-Middle and A3-End, the reduced elastic modulus values have increased at least 1–2 GPa through the thickness of the substrate (observed as the colour change in the maps). This increase is also believed to be a leading cause of the formation of the delaminations in the substrate. The loss of plasticizer leads to a higher elastic modulus, which in turn leads to a higher stiffness of the CA substrate. The higher the stiffness, the lower the flexibility (increased brittleness) and increased likelihood of substrate fracture through crack formation. Additionally, there is a clear gradient of the reduced elastic modulus values in Fig. 4 with a decrease of the Er values towards the right side of the cross-section—side with the gelatine layer. It is possible that the thin gelatine layer provides sort of a protection for the CA substrate, slowing down the aging process, while on the side exposed to the air the aging proceeds much faster (indicated by increased elastic modulus). Moreover, the A3-Middle is a sample taken from the middle of the film roll and A3-End at the end of the roll meaning that there is more exposure at end than in the middle of the roll. What is also observed in Fig. 8 are the delaminations in the substrate. These delaminations could also be called cracks and most likely form due to the loss of plasticizer. When and how the delaminations form is still under investigation. At this point the authors do not want to speculate on the initiation and propagation of the delaminations. The reduced elastic modulus varies significantly due to the loss of plasticizer, and this most likely occurs inhomogeneously over the entire roll depending on position and exposure time.

Applying the findings outlined in4 accordingly, such as the thermodynamic prerequisites for plasticizer loss as well as the kinetic laws (such as the setting of vapour pressure or distribution equilibria, the importance of the diffusion coefficient, etc.), it becomes obvious that physical phenomena have a significant influence on the inhomogeneous ageing behaviour of cinematographic film materials stored over long time on a film roll, with a certain tension and pressure. Storage conditions, such as temperature and humidity and heavy variations thereof, as well as the different pressure distributions from the loosely wound beginning of a film roll to the tightly wound centre of the pack, strongly influence evaporation of plasticizers and other volatile substances, such as e.g. acetic acid during long-term storage. The interaction of all these factors and their influences on material elasticity so far have not yet been sufficiently investigated. The authors propose nanoindentation as an adequate method, to assess the stage of the CA substrate aging and the right time for the appropriate rejuvenation method. The nanoindentation itself proved to be a good method to identify the changes in the CA substrates even in the initial stages of the aging (samples A1 and A2) and the application of such method does not need a large samples nor complicated experimental setup. Additionally, the nanoindentation method can be used to further study the changes in materials similar to CA (present in the field of heritage materials) until the critical failures (as in sample A3-End) for a better understanding of the damage processes.

Brittleness and elasticity, as well as shrinkage, are main factors that prevent or even make impossible processing of cinema films based of cellulose acetate during the scanning process for digitization and long-term accessibility. The very details of changes in the mechanical behaviour of cellulose acetate caused by loss and migration of plasticizers and other volatile substances have not been satisfactorily characterized so far. We proposed the nanoindentation as a method of choice for characterization of the aging stages of cinematographic films. The cellulose acetate substrate reduced elastic modulus should stay around 5 GPa to avoid the formation of delaminations. It should be noted that a 2 GPa increase in reduced elastic modulus is only a 0.01 GPa increase in hardness when nanoindentation is used, making the reduced elastic modulus the more suitable mechanical property to assess. As was also demonstrated, Shore A hardness is simply not sensitive enough to measure the necessary mechanical properties in cinematographic films as they age. The new knowledge obtained by nanoindentation can provide deeper insight into the aging mechanisms of cellulose acetate substrates and details of the differences in loss and distribution of plasticizers and thus different elasticity coefficients within the material.

Data availability

Data used and presented will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Allen, N. S. et al. Degradation of historic cellulose triacetate cinematographic film: the vinegar syndrome. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 19, 379–387 (1987).

Adelstein, P. Z., Reilly, J. M., Nishimura, D. W. & Erbland, C. J. Stability of cellulose ester base photographic film: part III—measurement of film degradation. SMPTE J. 104, 281–291 (1995).

Edge, M., Allen, N. S., Jewitt, T. S. & Horie, C. V. Fundamental aspects of the degradation of cellulose triacetate base cinematograph film. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 25, 345–362 (1989).

Voigt, J. & Hoechst, M. Physikalisch-chemische Ursachen der Alterung von weichgemachten Kunststoffen. Mater. Corros. 18, 969–977 (1967).

Richardson, E., Truffa Giachet, M., Schilling, M. & Learner, T. Assessing the physical stability of archival cellulose acetate films by monitoring plasticizer loss. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 107, 231–236 (2014).

Liu, L., Gong, D., Bratasz, L., Zhu, Z. & Wang, C. Degradation markers and plasticizer loss of cellulose acetate films during ageing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 168, 108952 (2019).

Read, P. & Meyer, M.-P. Restoration of Motion Picture Film. (Elsevier Science, 2014).

King, R., Grau-Bové, J. & Curran, K. Plasticiser loss in heritage collections: its prevalence, cause, effect, and methods for analysis. Herit. Sci. 8, 123 (2020).

Wallaszkovits, N. Fighting the Decay: Permanent Refreshment of Acetate Media. in Sustainable Audiovisual Collections through Collaboration: Proceedings of the 2016 Joint Technical Symposium (eds. Stoeltje, R., Shively, V., Boston, G., Gaustad L. & Schüller, D.) 196–204 (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2017).

del Gaudio, I. et al. Water sorption and diffusion in cellulose acetate: the effect of plasticisers. Carbohydr. Polym. 267, 118185 (2021).

Da Ros, S. et al. Characterising plasticised cellulose acetate-based historic artefacts by NMR spectroscopy: a new approach for quantifying the degree of substitution and diethyl phthalate contents. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 183, 109420 (2021).

Shashoua, Y. Conservation of Plastics: Materials Science, Degradation and Preservation. (Butterworth-Heinemann, London, 2008).

Da Ros, S., Gili, A. & Curran, K. Equilibrium distribution of diethyl phthalate plasticiser in cellulose acetate-based materials: modelling and parameter estimation of temperature and composition effects. Sci. Total Environ. 850, 157700 (2022).

Witte, E. D., Allen, N. S., Edge, M. & Horie, C. V. Polymers in conservation. Stud. Conserv. 38, 67 (1993).

Walsh, B. Identification of cellulose nitrate and acetate negatives by FTIR spectroscopy. Top. Photogr. Preserv 6, 80–97 (1995).

Spalinger Zumbühl, B. Schichtaufbau von Celluloseesternegativen. Workshop Identifizierung und Handling von flexiblen Fototrägern, Memorial Conference 13 https://memoriav.ch/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/SPALINGER_Barbara_Workshop_Fachtagung.pdf (2022).

Konstantinidou, K., Strekopytov, S., Humphreys-Williams, E. & Kearney, M. Identification of cellulose nitrate X-ray film for the purpose of conservation: Organic elemental analysis. Stud. Conserv. 62, 24–32 (2017).

SMPTE RP 106, Film Tension in 35-mm Motion-Picture Systems Operating Under 0.9 m/s. Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (1995).

Nunes, S. et al. A diagnostic tool for assessing the conservation condition of cellulose nitrate and acetate in heritage collections: quantifying the degree of substitution by infrared spectroscopy. Herit. Sci. 8, 33 (2020).

ASTM D 2240 (2015). Standard Test Method for Rubber Properties—Durometer Hardness. (2015).

ISO 48-4: 2018 Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Hardness—Part 4: Indentation Hardness by Durometer Method (Shore Hardness). (2018).

Chandrasekaran, V. C. Typical rubber testing methods. in Essential Rubber Formulary 16–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-081551539-5.50008-0.(Elsevier, 2007).

Liao, Z., Hossain, M. & Yao, X. Ecoflex polymer of different Shore hardnesses: Experimental investigations and constitutive modelling. Mech. Mater. 144, 103366 (2020).

Zak, S., Trost, C. O. W., Kreiml, P. & Cordill, M. J. Accurate measurement of thin film mechanical properties using nanoindentation. J. Mater. Res 37, 1373–1389 (2022).

Long, X., Dong, R., Su, Y. & Chang, C. Critical review of nanoindentation-based numerical methods for evaluating elastoplastic material properties. Coatings 13, 1334 (2023).

Karimzadeh, A., R. Koloor, S. S., Ayatollahi, M. R., Bushroa, A. R. & Yahya, M. Y. Assessment of nano-indentation method in mechanical characterization of heterogeneous nanocomposite materials using experimental and computational approaches. Sci. Rep. 9, 15763 (2019).

Fischer-Cripps, A. C. Nanoindentation. (Springer, New York, 2004).

Oliver, W. C. & Pharr, G. M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res 7, 1564–1583 (1992).

Oliver, W. C. & Pharr, G. M. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. Mater. Res. Soc. 19, 3–20 (2004).

Rossi, E., Wheeler, J. M. & Sebastiani, M. High-speed nanoindentation mapping: A review of recent advances and applications. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 27, 101107 (2023).

Tiennot, M., Paardekam, E., Iannuzzi, D. & Hermens, E. Mapping the mechanical properties of paintings via nanoindentation: a new approach for cultural heritage studies. Sci. Rep. 10, 7924 (2020).

Wang, Z. L., Hu, M. X., Wang, Y. L., Li, X. M. & Yin, S. Micro-mechanical properties of Song Dynasty tilestones based on nanoindentation tests and homogenization approach. Herit. Sci. 12, 315 (2024).

Łukomski, M., Bridarolli, A. & Fujisawa, N. Nanoindentation of historic and artists’ paints. Appl. Sci. 12, 1018 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031018 (2022).

Callister, W. D. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 2000).

Reilly, J. M. IPI Storage Guide for Acetate Film. Image Permanence Institute (1993).

P. Liepert, L. Spoljaric-Lukacic & N. Wallaszkovits. Method for Reconditioning Data Carriers. (2011). Appl. filed 23.12.2011, published 05.07.2012. IPC: G11B 23/50 (2006.01), G03D 15/00 (2006.01). Pub. No.: WO/2012/088553.

Acknowledgements

S. Zak received funding in the framework of the FWF (Österreichishes Wissenschaftsfonds) ESPRIT program under grant number ESP 41-N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept: N.W., M.C.; Design of experiments: M.C., N.W.; Data acquisition and analysis. M.C., S.Z.; Figure preparation: M.C., S.Z.; Writing/revising of manuscript: M.C., S.Z., N.W. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cordill, M.J., Zak, S. & Wallaszkovits, N. Using nanoindentation to study the aging of cellulose acetate in cinematographic films. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 364 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01940-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01940-3