Abstract

Intelligent material recognition in traditional Chinese painting images is vital for digital cultural heritage preservation. However, existing methods struggle with limited samples and weak feature representation. This paper proposes a new classification framework based on the prototypical network with a ResNet18 backbone. To enhance sensitivity to fine-grained details, a cropping-based augmentation strategy is introduced during inference. Additionally, a multitask learning scheme is employed to improve generalization and enrich global representations, where the auxiliary task of dynasty classification is trained jointly with the main task of material classification. Furthermore, an ensemble voting strategy is applied to refine the final predictions. Experiments on a self-constructed dataset demonstrate the robustness of the entire strategy under few-shot scenarios, achieving 80% accuracy with merely 30 samples and outperforming comparative methods. Moreover, this work provides practical value for the development of intelligent tools to support the digital preservation of traditional Chinese art.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artworks constitute a significant component of cultural heritage, embodying the wisdom and creativity of human civilization. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of digital technology, research focusing on the digitization and intelligent analysis of art collections has gradually emerged as a popular area of study. This encompasses various research domains such as digital artwork recognition1, style transfer2, AI-based creation3, and technical authentication4. However, in certain specialized areas, the recognition of digital art images still lacks efficient and practical solutions. For instance, research on the materials and techniques of traditional Chinese painting images remains insufficient, posing significant challenges to the preservation and presentation of related digital content. Therefore, this paper focuses on the methodology for material classification of traditional Chinese painting images.

Traditional Chinese paintings are typically created on delicate materials such as paper, silk, and silk fabric, necessitating strict environmental controls, including precise regulation of humidity and temperature5. Prolonged exposure during display can lead to deterioration, such as thinning and brittleness, resulting in irreversible damage. As a result, the digital preservation of traditional Chinese paintings and the development of corresponding digital art galleries have become urgent priorities. However, this transition introduces technical challenges. Traditional image classification methods depend on specialized appraisers for manual identification, complicating the digital archiving process. With the ongoing integration of culture and technology, applying artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to the intelligent identification of traditional Chinese painting images has emerged as a key area of research6,7,8. Studies in this field hold the potential to improve retrieval and recognition technologies, facilitate the digital dissemination and preservation of traditional Chinese culture, and enhance the artistic experience for a broader audience. Research on Chinese painting image classification predominantly focuses on content recognition9,10,11 and artist attribution12,13,14, with comparatively fewer studies addressing material classification. The materials used in these paintings, which serve as both foundation and medium, profoundly affect the appearance of ink and pigments, making material classification essential to understanding and appreciating traditional Chinese painting. Therefore, this paper investigates the classification of materials in traditional Chinese painting images, aiming to provide a systematic framework for digital art collection, exhibition, and appreciation.

Research on the classification of traditional Chinese painting images is divided into two main categories: traditional feature extraction combined with machine learning classification methods and deep learning techniques. While the application of classification technologies specific to traditional Chinese painting remains relatively limited, recent developments in general image classification methods, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)15, Transfer Learning16, and Few-Shot Learning17, have provided valuable technical tools and inspired new approaches in this domain. However, due to the unique characteristics of traditional Chinese paintings—including fine brushwork, diverse material substrates (e.g., paper, silk), and embedded cultural symbolism—direct application of these general methods often results in suboptimal performance. These models tend to struggle with capturing domain-specific features, especially in low-data settings or when material classification is required. Therefore, further adaptation is needed to bridge this gap and develop classification methods tailored to the distinct artistic and material properties of Chinese paintings.

Early image classification methods in computer vision typically employed feature extraction combined with machine learning techniques. The commonly used bottom-level features for the classification of Chinese painting images include texture features18,19, shape features20, and so on. Jiang et al.6 enhanced edge histogram extraction by using the Sobel operator and combining it with autocorrelation texture features, successfully distinguishing between Gongbi (traditional Chinese realistic painting) and Xieyi (freehand style) using a Support Vector Machine (SVM). Wang et al.21 employed a supervised sparse feature selection method to identify key features that distinguish the painting styles of different artists, thereby establishing a connection between artistic styles and the underlying features of Chinese paintings. Sheng et al.22 utilized a three-layer wavelet transform to extract texture features and employed decision trees, traditional fully-connected neural networks trained via backpropagation (BP), and SVM to automatically classify artists. Sheng et al.23 further improved classification accuracy by incorporating both local and global features through edge detection algorithms and window functions, as well as optimizing a BP neural network via windowing and entropy balancing. Sun et al.12 extracted the painting strokes and calculated stroke length, curvature, and density as the stroke feature. They further refined stroke, color, and texture features using a Monte Carlo convex hull model, achieving 95% precision and 93% recall with an SVM classifier.

In contrast to traditional machine learning methods, which rely on handcrafted feature extraction, deep learning approaches typically operate directly on raw pixels, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering24. By learning high-level features from the data, deep learning models, especially CNNs, have significantly improved performance in tasks such as image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. Sun et al.25 introduced a mixed-sparsity CNN method to automatically extract stroke features from Chinese ink wash paintings for author classification. On a dataset of 180 traditional paintings by six renowned Chinese artists, their method achieved a precision of 95% and a recall of 93%. Sheng et al.26 applied superpixel segmentation to divide traditional Chinese painting images into stable artistic units, then used a CNN model to extract high-level semantic features, combining them with SVM to identify ten painters. Zhou27 enhanced a basic CNN architecture by integrating Inception modules to extract multi-scale features and adding residual connections to leverage low-level features, along with batch normalization and overlapping pooling to prevent overfitting, ultimately improving classification accuracy by 2.6% compared to the basic CNN architecture. Yu et al.28 proposed a novel method for artist attribution in digital painting classification, utilizing a multi-scale pyramid representation to incorporate both global and local features, with a CNN model trained to classify at each pyramid level.

Due to traditional Chinese painting image classification belonging to a specialized field, the availability of accurately labeled samples is limited. Few-shot learning, which can achieve high performance by learning from a small number of samples in new tasks, provides a viable solution for data-scarce scenarios29. Xiao30 improved classification performance by using transfer learning, pre-training the model on natural images similar to painting categories, and applying semi-supervised learning to leverage both labeled and unlabeled data. Chen31 adopted a meta-learning relational network model, pre-trained on mini-ImageNet, and tested its adaptability on the Dunhuang mural dataset with only 5% of the original samples, achieving results comparable to those obtained using the full training dataset. Li et al.32 proposed a graph neural network (GNN)-based method for Dongba paintings, constructing a multi-resolution spatial pyramid to capture key details and combining edge-labeled graphs with attention mechanisms to enhance node connections. Xu et al.33 further advanced Dongba painting classification by integrating spatial information and distribution relationships using a bidirectional GNN, improving accuracy by optimizing feature associations between support and query sets. Ding et al.34 proposed a semi-supervised learning (SSL) method for traditional Chinese painting image classification, utilizing the self-attention-based MobileVit model as the backbone and introducing a data augmentation technique, Random Brushwork Augment to incorporate brushwork patterns, achieving an accuracy of 88.27% on the test dataset, even with only 10 labels, each representing a single class.

Multitask Learning is a machine learning approach that aims to enhance the performance of multiple related tasks by utilizing shared information across them35. This method has been effectively applied in various domains, including cultural heritage image classification. Dorozynski36 proposed a multitask learning method for silk fabric classification in cultural heritage images using a CNN-based classifier (SilkNet) with a ResNet-152 backbone. It predicts attributes like time period and origin, addressing class imbalance with a focal loss function and auxiliary feature clustering. Bianco et al.37 proposed a deep multibranch and multitask neural network for the classification of artist, style, and genre in paintings. This approach uniquely leverages both coarse and fine-grained structural features of paintings by utilizing intelligently extracted painting crops at different resolutions, which are selected through a Spatial Transformer Network (STN).

Traditional feature extraction combined with machine learning requires complex feature engineering, and due to the significant differences between traditional Chinese paintings and natural images, existing feature extraction methods struggle to effectively capture the complex and unique material characteristics of these artworks. While deep learning methods can automatically learn high-level features, they typically require large amounts of training data. However, precise labeling of materials in traditional Chinese paintings demands specialized expertise, and the rarity of certain materials results in small datasets with imbalanced class distributions. These challenges make current methods insufficient for capturing the intricate material features of traditional Chinese paintings, highlighting the need for a new approach that can address the limitations of data scarcity, while effectively capturing the unique material properties inherent to these artworks.

While several recent studies have explored Chinese painting classification using CNN-based models25,26,27,28 and semi-supervised learning methods32,33,34, the majority of these works primarily target content recognition (e.g., subject matter) or artist attribution, rather than addressing material classification, which is essential for conservation and digital archiving.

For example, Sheng et al.26 applied superpixel segmentation and a CNN-SVM pipeline to classify painters based on stylistic regions. Zhou27 enhanced CNN architectures to improve artist attribution accuracy. However, both methods rely on global image features and do not explicitly model substrate materials such as paper, silk, or silk fabric, which are critical for material-level differentiation.

GNN-based approaches32,33, though innovative, were developed for Dongba or symbolic paintings that differ significantly from traditional Chinese paintings in visual structure and material usage. Ding et al.34 proposed a semi-supervised model with brushwork-focused data augmentation, yet their emphasis remains on stroke characteristics rather than underlying materials.

Moreover, approaches such as transfer learning30 and semi-supervised learning31,34 have been introduced to alleviate the challenge of limited labeled data. However, these methods typically assume global representations and are tuned for style- or category-based classification, making them less effective in capturing fine-grained, local texture differences needed for material classification—particularly in the presence of data imbalance or rare material types.

To address these challenges, two key enhancements to the Prototypical Network38 are proposed with the aim of improving model performance in material classification of traditional Chinese paintings with limited samples. Prototypical Network is a metric-based few-shot learning method that classifies query samples by computing their distances to class prototypes derived from the support set. Compared to conventional CNN classifiers or fully supervised methods used in previous works25,26,27,28,30, it is particularly suited for data-scarce scenarios, as it reduces overfitting by leveraging class-level representations instead of training high-capacity classifiers. Prior studies have demonstrated the superior performance of Prototypical Networks in low-resource settings, such as in paleontological fossil recognition39, and in medical image classification40. These advantages align with our problem setting, where material distinctions are subtle and labeled data is limited. These improvements focus on enhancing input diversity through image transformations such as cropping and scaling, and on adapting the classification algorithm to the unique characteristics of the material of traditional Chinese paintings.

-

(1)

Cropping enhancement: to comprehensively capture the intricate details of traditional Chinese paintings, we apply a cropping enhancement strategy to both support set and query images. Each image is partitioned into multiple non-overlapping or partially overlapping regions of size 224 × 224 pixels. This design allows the model to focus on fine-grained local features, such as brushstroke textures and paper/silk details, which are often difficult to learn from global images alone. For each region, a ResNet41 is subsequently employed to extract feature vectors. The prototype vectors of each material class are calculated by averaging the feature embeddings of cropped support samples. During inference, the cropped query patches are compared to these prototypes using Euclidean distance. The predictions of all patches from a query image are then aggregated using a majority voting strategy, yielding the final classification result. Notably, only cropped image patches are used for training and inference, without incorporating global full-resolution images. This design ensures consistency between training and testing phases, and encourages the model to fully leverage local visual cues for classification.

-

(2)

Multitask learning optimization: a multitask learning (MTL) approach, which jointly trains the material classification task with an auxiliary task, is introduced to enhance the model’s performance in a data-scarce setting. MTL enables the network to learn more generalized and transferable representations by leveraging related supervisory signals42,43. In this work, we considered three potential auxiliary tasks: dynasty classification, content classification, and technique classification. After comparative evaluation, we selected dynasty classification as the only auxiliary task. This decision was based on three factors: (1) the label quality and class balance of dynasty labels are superior to the other two tasks; (2) dynastic periods strongly correlate with material usage in traditional Chinese painting (e.g., the prevalence of silk in earlier dynasties); and (3) using multiple auxiliary tasks simultaneously introduced noise and gradient conflicts, degrading model performance. The overall loss is computed as a weighted sum of the material and auxiliary task losses, with a higher weight assigned to the primary task to ensure focused optimization. This design allows the auxiliary task to guide feature learning without dominating the training process.

Methods

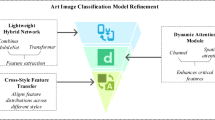

The proposed method is designed to classify traditional Chinese painting images based on their material type, utilizing a multitask learning approach. The inputs to the algorithm consist of traditional Chinese painting images, each labeled with both a main task (material classification) label and an auxiliary task label. The output of the method is the material classification of each image. The algorithm involves two tasks: the main task of material classification and an auxiliary task (one of the dynasty, content, or technique classification task). The approach employs a prototypical network with a ResNet18 backbone for feature extraction and utilizes both cropping and zooming modules to enhance the input data and increase the number of training samples. A weighted joint loss function is used to optimize the model’s performance by balancing the contributions from both the main and auxiliary tasks.

The proposed method consists of three components: the cropping enhancement module, the prototypical feature extraction module, and the multitask module.

The algorithm process is as follows: a support set \(S\) is created by randomly selecting \(K\) images from silk painting, paper painting, and murals in the training set. Similarly, \(K\) images from each category are randomly chosen from the remaining samples (i.e., the samples not selected for the support set) to form the query set \(Q\). The training samples are also labeled for auxiliary tasks, and the selection of support and query sets ensures a relatively balanced number of samples in each category for these tasks. Specifically, when selecting support set samples for the main task, we ensure that for each category, a certain number of samples (e.g., 5) are chosen. These selected samples are then roughly evenly distributed across the auxiliary tasks, ensuring a balanced sample allocation across tasks, even when multiple tasks are trained simultaneously. The algorithm is then divided into two tasks: the main task, which is material classification, and one auxiliary classification task. In the material classification task, images are processed through a cropping module, where each image is cropped into \(n\) local region images to extract local features. In the auxiliary classification task, images are processed through a zoom module, where each image is first randomly cropped to 80% of its original size and then resized to match the model’s input dimensions. For each original image, \(n\) such variants are generated and used for training, effectively increasing the number of training examples by a factor of \(n\). Both the material classification and auxiliary classification tasks share a ResNet18 network as the backbone for feature extraction. Although both tasks use images derived from the same original input, they employ different augmentation strategies to better suit their respective learning objectives. In the material classification task, support set images are enhanced using a cropping module, which divides each image into multiple fixed-size patches. This enables the model to focus on fine-grained local features—such as brushstroke texture and substrate patterns—that are critical for distinguishing between different painting materials. Conversely, in the auxiliary classification task (e.g., dynasty classification), support set images are processed using a zoom module, which scales the image to preserve its global layout and stylistic elements. This is because attributes like painting composition, style uniformity, and era-specific motifs are better captured in the full image context. In the training phase, both support set and query set samples are involved in calculating classification loss. The support set is used to compute the prototype vectors for each class, while the query set samples are used to compute the loss based on the distance between the query sample’s features and the prototype vectors. Query set samples undergo cropping and zooming, and after feature extraction, the Euclidean distance between their features and class prototypes is calculated. These distances are converted into probability distributions using the softmax function and compared with true labels to compute the cross-entropy loss. Both tasks generate individual loss values, which are combined in a weighted manner to form the total loss function. The weights for the main task and auxiliary task are set manually such that their sum is equal to 1, and these weights are tuned during the experiments to find the optimal balance between the tasks. The feature extraction network is then updated and optimized via backpropagation. In the testing phase, the test images are processed through the cropping module to generate multiple region images. Each region image is fed through the trained network to extract features and calculate the Euclidean distance to each material category’s prototype vector. The softmax function is then used to obtain the classification result for each cropped region. Finally, the classification results of multiple cropped regions are aggregated using a majority voting mechanism, where the predicted class with the most votes is selected as the final material classification result. The network framework is shown in Fig. 1 below.

The process consists of support and query set creation, data enhancement via cropping (for the material task) and zooming (for the auxiliary task), ResNet18-based feature extraction, prototype representation calculation, and final classification through a voting mechanism. The inference phase follows the same pipeline without auxiliary supervision, where the final prediction is based on the distance between query samples and learned prototypes.

Prototypical network

In this work, we adopt the Prototypical Network as the baseline architecture due to its effectiveness in few-shot learning tasks. In our implementation, a ResNet18 backbone is used to extract feature embeddings from input images. For each classification episode, a support set is constructed, and the prototype for each category is computed as the mean vector of the feature embeddings of all support images belonging to that class. The classification of each query sample is then performed by calculating its Euclidean distance to each prototype in the embedding space, and assigning the label of the nearest prototype. The final prediction for a query image is based on the prototype closest to it in terms of Euclidean distance. The calculation formula for the prototype \({P}_{c}\) is as follows:

where \({S}_{c}\) represents the samples in the support set for the category \(c\), \({N}_{c}\) represents the number of samples in \({S}_{c}\), \({x}_{i}\) represents the input images, \({y}_{i}\) represents the class labels for the support set samples, and \({f}_{\theta }\) represents the feature extraction module that maps image features to the embedding space.

In the classification process, the model calculates the Euclidean distance between the query sample and each category prototype. The distance calculation formula is as follows:

where \({x}_{\mathrm{query}}\) represents a query sample, and \({f}_{\theta }({x}_{\mathrm{query}})\) represents the feature representation of \({x}_{\mathrm{query}}\). Ultimately, the query sample is classified as belonging to the category with the smallest distance. The implementation formula is as follows:

where \({c}^{\ast }\) represents the category with the smallest distance. Through this process, the model effectively classifies data by learning meaningful class prototypes—computed as the mean embeddings of support set samples—and continuously updating the feature extraction network parameters during training iterations. This enables the model to produce more discriminative embeddings and improves classification accuracy even with limited labeled data.

Cropping enhancement algorithm

The cropping enhancement algorithm is designed to capture detailed local information from traditional Chinese painting images, which often contain rich textures and intricate features. By sampling from multiple regions of an image, this algorithm improves the model’s ability to detect edges and fine details that might be overlooked when analyzing only a single crop. The input to this module is the original painting image, and the output is a set of cropped patches that provide a more comprehensive representation of the image’s local features.

The cropping enhancement algorithm proceeds as follows. First, the cropping size is set to 224 pixels. The width and height of the original image are then obtained. The number of cropped blocks along the width and height directions is calculated as follows:

where \({\rm{croppingsize}}\) refers to the size of each cropped region, \(W\) represents the width of the original image, \(H\) represents the height of the original image, \(m\) and \(n\) represents the number of cropped blocks in the width and height directions, respectively. \(\lfloor \rfloor\) denotes the floor operation, ensuring that m and n are natural numbers (i.e., positive integers). To prevent the loss of edge information, an additional crop is applied to the last row and column along both the width and height directions. The total number of cropped blocks can be calculated as follows:

where \(s\) represents the total number of cropped blocks. When \(s\) is less than the specified number \({n}_{\mathrm{crop}}\), \(\mathrm{cropping}\,\mathrm{size}\) will be halved, and the previous steps will be repeated until the \(s\ge {n}_{\mathrm{crop}}\) is met. This ensures that sufficient cropped patches are generated to capture the necessary details. After determining the total number of cropped blocks, each block is sequentially numbered from 1 to \(s\), following a top-to-bottom, left-to-right order. Then, \({n}_{\mathrm{crop}}\) numbers are randomly selected with replacement from this set, denoted as \(\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\ldots ,{x}_{{n}_{\mathrm{crop}}}\}\), and the corresponding cropped blocks are extracted from the original image. As a result, duplicate cropped blocks may appear in the sampled set. However, since the total number of cropped blocks is relatively large, the probability of excessive repetition is low, and this does not negatively affect training performance. If \(\mathrm{cropping}\,\mathrm{size}\) was halved in the previous step, resulting in blocks that are not 224 × 224, these blocks will be enlarged to ensure all input blocks have a consistent size of 224 × 224 before feeding them into the model.

Multitask joint loss

The multitask joint loss module combines multiple classification tasks into a unified framework to enhance the performance of material classification. In this module, the primary task is material classification, while auxiliary task is one of the dynasty classification, technique classification, and content classification. The input to the material classification task consists of local regions extracted using the cropping enhancement method, while the auxiliary tasks use global features derived from the full image. A weighted joint loss function is employed to balance the contributions from both the primary and auxiliary tasks, with the weights tuned to achieve optimal performance. The output is the combined loss, The final output is the combined loss, which is used to train the backbone model of the Prototypical Network (ResNet18).

In the multitask learning framework, both the material classification and auxiliary tasks use inputs derived from the same original image, but with different augmentation strategies tailored to each task’s focus. Specifically, the material classification task utilizes cropped regions to emphasize local textures, while the auxiliary task uses zoomed images to preserve global layout and stylistic context. To effectively capture material information, local regions of the image are extracted using a cropping enhancement method, which serves as input for the material classification task. This approach emphasizes fine-grained texture and brushstroke details, which are essential for distinguishing between different materials. In contrast, the auxiliary tasks focus on higher-level attributes such as stylistic consistency and historical period, which depend more on global context. Therefore, \({n}_{\mathrm{crop}}\) images are randomly cropped, each covering 80% of the original painting, and the cropped images are resized to 224 × 224 pixels to serve as input for these tasks.

Both the material classification task and the auxiliary task use the cross-entropy loss function. The expression formula is as follows:

where \(L\) represents the loss value, \(N\) represents the number of samples, \(C\) represents the number of classes, \({y}_{i,c}\) represents the indicator function for the true label of sample \(i\) in class \(c\), \({\hat{y}}_{i,c}\) represents the predicted probability that \(i\) belongs to class \(c\). A weighted joint loss function is employed to balance the influence between the primary task and the auxiliary task. The weight parameter is used to control the relative importance between the material classification loss and the auxiliary task losses. The multitask joint loss is calculated as follows:

where \(w\) represents the weight parameter of the material classification task, \({L}_{\mathrm{total}}\) represents the joint loss of the multitask, \({L}_{material}\) represents the loss for the material classification task, and \({L}_{auxiliary}\) represents the loss for the auxiliary task. The parameter \(w\in [1,0]\) is used to adjust the weight between the material task and the auxiliary tasks. When \(w\) is close to 1, the model focuses more on the material classification task, with less influence from the auxiliary task losses. The final joint loss is used to optimize the ResNet18 network parameters during backpropagation. By adjusting the value of \(w\), an appropriate balance can be found between the material task and the auxiliary tasks to enhance the accuracy of material classification while effectively utilizing the information from auxiliary tasks.

Results and discussion

Data source

This experiment collected a total of 3132 images of Chinese traditional paintings, categorized into three types based on their materials: silk paintings, paper paintings, and murals. For model training and evaluation, the dataset was divided into a training set and a test set. The training set contains 150 images for each category. Additionally, for the multitask learning setup, each image in the training set was annotated with additional labels, including the content, technique, and dynasty. Specifically, for the dynasty classification task, the training set includes 30 images per class (5 classes), for the content classification task, it includes 50 images per class (3 classes), and for the painting technique task, it includes 75 images per class (2 classes). The test set consists of 912 silk paintings, 864 paper paintings, and 906 murals, with only material classification labels provided for evaluation. The specific details of the dataset and its class distributions are presented in the following three tables.

Experimental environment

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, tests on the dataset of traditional Chinese paintings were conducted. The experiments were carried out on a system equipped with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700H @2.30 GHz processor. The software environment included the PyCharm compiler, running on a Windows 11 system. The software was written in Python 3.9, and PyTorch was used as the framework for model training and evaluation.

Training strategy

All parameters of the ResNet18 backbone are trained from scratch with random initialization, without using any pre-trained weights. The model is optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, and the training proceeded for a maximum of 200 epochs.

Due to the limited size of available labeled data, we did not split an explicit validation set. Instead, a portion of the training set was used for internal monitoring of training convergence and selection of hyperparameters (e.g., cropping size), while the final evaluation results are reported only on the unseen test set. This strategy ensures a fair comparison across models without introducing overfitting risks during evaluation (Tables 1–3).

Experimental results and comparisons

To determine the optimal experimental parameters, we conducted a systematic hyperparameter tuning process. Initially, we replaced the feature extraction network in the prototypical network, excluding both the auxiliary task and cropping module, to identify the best-performing feature extractor. Next, we adjusted the crop count and the number of support set samples to determine the optimal values for both. Building on these adjustments, we explored different crop sizes to identify the best crop size. With the optimal feature extraction network, crop count, support set sample number, and crop size in place, we then changed the auxiliary task categories and adjusted the weight distribution between the main task and the auxiliary tasks. All experiments were performed on the training set, with evaluation conducted on the test set.

When the support set size \(K=5\), the feature extraction network was replaced with a 6-layer CNN (CNN6), ResNet18, ResNet34, and ResNet50 to compare their performance in the materials classification for traditional Chinese paintings. The experimental results are shown in Table 4. The prototype network with ResNet18 achieved the highest test accuracy of 69.01%, significantly outperforming the other networks. ResNet18 has a deeper network structure, allowing for more effective capture of high-level image features and providing stronger representational capacity. Compared to CNN6, ResNet34, and ResNet50, ResNet18 strikes a better balance between the number of parameters and model complexity, avoiding excessive overfitting while still extracting rich feature information. Based on these findings, ResNet18 was selected as the feature extraction network.

When the support set size \(K=5\), experiments were conducted with various crop counts: 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10. For the crop count \({n}_{\mathrm{crop}}=0\), no cropping was performed, and the image was directly resized to 224 × 224 pixels. The experimental results are shown in Table 5. After incorporating the cropping enhancement and ensemble classification strategy, the model’s performance improved significantly across various cropping counts compared to the baseline without cropping. Specifically, when one crop was used, the accuracy was nearly 10% higher than the baseline. Among the various crop counts tested, the model achieved the highest accuracy of 81.76% when \({n}_{\mathrm{crop}}=5\). As the crop count increased from 1 to 5, classification accuracy improved, as the model was able to capture a greater variety of local features. However, beyond five crops, the performance began to decline. This suggests that while increasing the crop count helps in capturing diverse local features, excessive cropping may introduce redundant information. This redundancy can lead to overfitting, where the model focuses on specific details that do not generalize well to new data, resulting in diminished performance. Thus, an optimal crop count of 5 was chosen for subsequent experiments.

Based on the optimal crop count of 5, additional experiments were conducted with varying numbers of support set samples, specifically setting the support set size \(K\) to 3, 5, 7, and 10. The results of these experiments are presented in Table 6. When the number of support set samples is 5, the traditional Chinese painting material classification task achieves the best performance.

With the support set sample size set to 5 and the number of crops set to 5, we systematically adjusted the crop size, testing sizes of 128 × 128, 224 × 224, 256 × 256, and 448 × 448. The results are presented in Table 7, showing that the best performance for the traditional Chinese painting material classification task was achieved when the crop size was set to 224 × 224.

The auxiliary task types and their respective weights were then fine-tuned within the multitask learning framework, using the optimal parameters identified earlier. The experiment tested the following combinations: jointly training the material classification task with dynasty classification, content classification, and technique classification. By adjusting the loss weights between the main and auxiliary tasks, the impact of each auxiliary task on material classification performance was assessed, helping to identify the optimal multitask learning strategy. The results, shown in Table 8, indicate that jointly training the material classification task with dynasty classification and setting the main task weight to 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, or 0.8 all improved performance compared to training the material task alone. The model achieved its best performance with a main task weight of 0.8, reaching an accuracy of 86.69% on the test set. This suggests that assigning a higher weight to the material task during joint training enhances performance, likely due to a strong correlation between dynasty and material classification in Chinese paintings. A higher weight emphasizes the material task, enabling the model to utilize the available data better and improve accuracy. When the weight of the main task is set to less than 0.5, regardless of the auxiliary task with which it is jointly trained, the accuracy of Chinese painting material classification drops noticeably. However, when the main task weight exceeded 0.8, performance declined, likely because the model overly focused on the material task and neglected useful information from the auxiliary task, negatively affecting overall performance. In contrast, adjusting the material task weight during joint training with content or technique classification tasks did not improve performance, possibly due to weaker correlations between these tasks and the material classification task, limiting the model’s ability to leverage auxiliary information effectively.

To validate the effectiveness of the two proposed improvements, we conducted a series of ablation experiments under the optimal parameters: a support set sample size of 5, 5 crops per image, and a dynasty classification task as the auxiliary task, with a main task weight of 0.8.

-

(1)

Effectiveness of the cropping module: in the first ablation experiment, we removed the cropping module and directly input the images into the prototypical network to assess its impact on performance.

-

(2)

Effectiveness of multitask learning: in the second ablation experiment, we removed the multitask module and trained only the material classification task to test the contribution of multitask learning.

The results of the ablation experiments are presented in Table 9.

As shown in Table 9, removing either the cropping or multitask module results in a noticeable decline in the model’s performance, with accuracy dropping to 78.6% and 81.8%, respectively. The performance further decreases when both modules are removed, reaching an accuracy of 69.0%. This demonstrates that both the cropping and multitask modules contribute significantly to improving the model’s performance. Combining these two enhancements achieves the best results, showing that their synergy is essential for optimizing the classification task.

To assess the stability of the ResNet model training and validate the advantages of the proposed algorithm in few-shot scenarios, we conducted a series of comparative experiments. The number of training samples per class was varied (10, 20, 30, 50, 80, 100, 150, and 200), and the same test set was used for evaluation. Each experiment was repeated five times to ensure result stability and evaluate the variability of the model’s performance. The accuracy mean and standard deviation were computed for each sample size. The results are presented in Table 10, which shows the mean accuracy and standard deviation for different training sample sizes.

Comparison with traditional machine learning algorithms

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, our network model was compared with several machine learning models, including Random Forest (RF)44, SVM45, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)46, LightBoost47, XGBoost48, and RusBoost49. Features extracted from the pre-trained CLIP50 model were used as inputs for all these algorithms. As shown in Fig. 2, the proposed algorithm achieves nearly 80% classification accuracy with minimal training samples, significantly outperforming the other models.

Comparison with advanced convolutional neural network algorithms

The proposed algorithm was compared with state-of-the-art CNN algorithms for Chinese painting classification, including CNN201751, CNN201952, and CNN202127. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the proposed algorithm consistently outperformed existing CNN-based models across all sample sizes. This indicates that CNN-based algorithms generally require larger datasets to achieve optimal performance, while the proposed method demonstrates significant advantages under small-sample conditions.

Comparison with small-sample Chinese painting classification methods

The proposed algorithm was compared with several typical small-sample Chinese painting classification algorithms, including AL53, a semi-supervised learning method that leverages actively selected informative samples to address data scarcity, and the method proposed by Xiao30. As shown in Fig. 4, the proposed algorithm significantly outperformed other small-sample algorithms when the number of samples per category was below 75. Even when the sample size exceeded 100, the proposed algorithm still slightly outperformed the AL series algorithms. These results demonstrate that the proposed method effectively improves classification accuracy in scenarios with extremely limited samples and continues to maintain high performance as the number of samples increases, highlighting its advantages in small-sample Chinese painting classification.

Discussion

This study presents a novel approach to tackling sample scarcity and limited feature representation in the classification of materials in traditional Chinese painting images. Leveraging a prototypical network framework based on ResNet18, the model integrates cropping enhancement, ensemble voting, and auxiliary task joint training. Cropping and voting techniques aim to capture intricate material details, refining the predictive process, while auxiliary tasks offer additional contextual insights relevant to material classification.

Experiments conducted on a self-constructed dataset validate the effectiveness of the model, particularly when the auxiliary task is dynasty classification and the loss weight for the material classification task is set to 0.8, resulting in optimal performance that surpasses existing advanced methods. The main findings of the study are as follows:

-

(1)

For the task of Chinese painting image classification with limited data, the proposed prototypical network framework effectively leverages CNN feature extraction to maximize the use of limited training samples, improving classification performance. By structuring support and query sets, the method identifies optimal feature representations, facilitating knowledge acquisition from the images.

-

(2)

The cropping enhancement method is beneficial for the learning of material-related detailed features from different regions of the picture. These features are potentially hidden in the foreground or background of the image. Therefore, the use of ensemble voting allows for a comprehensive analysis of the prediction results from these regions, resulting in optimal output.

-

(3)

The distinct production techniques of various dynasties, which are often reflected in painting images, provide an advantageous context for material classification. The multitask learning approach capitalizes on dynasty information to boost model performance, enhancing the accuracy of material classification.

In summary, this research offers an effective solution for the material classification of Chinese painting images under sample constraints, demonstrating the strong feature extraction capability of the prototypical network. Additionally, this study provides a small-sample learning framework that can be applied to other image classification tasks related to Chinese paintings. Future efforts could focus on further refining region-specific cropping and enhancing feature extraction networks, along with incorporating auxiliary task designs to improve both model accuracy and adaptability. This study is of significant importance for the identification and preservation of cultural heritage, providing technical support for the development of related digital system tools.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Tan, W. R. et al. Ceci n’est pas une pipe: a deep convolutional network for fine-art paintings classification. In Proc. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP) 3703–3707 (IEEE, 2016).

Jing, Y. et al. Neural style transfer: a review. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph 26, 3365–3385 (2019).

Cetinic, E. & She, J. Understanding and creating art with AI: review and outlook. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. TOMM 18, 1–22 (2022).

Dobbs, T. et al. Contemporary art authentication with large-scale classification. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 7, 162 (2023).

Zhang, X., Berghe, I. V. & Wyeth, P. Heat and moisture promoted deterioration of raw silk estimated by amino acid analysis. J. Cult. Herit. 12, 408–411 (2011).

Jiang, S. et al. An effective method to detect and categorize digitized traditional Chinese paintings. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 27, 734–746 (2006).

Liong, S. T. et al. Automatic traditional Chinese painting classification: a benchmarking analysis. Comput. Intell. 36, 1183–1199 (2020).

Sheng, J. & Li, Y. Classification of traditional Chinese paintings using a modified embedding algorithm. J. Electron Imaging 28, 023013–023013 (2019).

Meng, Q. et al. The classification of traditional Chinese painting based on CNN. In Cloud Computing and Security: 4th International Conference (ICCCS 2018) 232–241 (Springer, 2018).

Li, D. & Zhang, Y. Multi-instance learning algorithm based on LSTM for Chinese painting image classification. IEEE Access 8, 179336–179345 (2020).

Yang, D., Ye, X. & Guo, B. Application of multitask joint sparse representation algorithm in Chinese painting image classification. Complexity 2021, 5546338 (2021).

Sun, M. et al. Monte Carlo convex hull model for classification of traditional Chinese paintings. Neurocomputing 171, 788–797 (2016).

Jiang, W. et al. MTFFNet: a multi-task feature fusion framework for Chinese painting classification. Cogn. Comput. 13, 1287–1296 (2021).

Geng, J. et al. MCCFNet: multi-channel color fusion network for cognitive classification of traditional chinese paintings. Cogn. Comput. 15, 2050–2061 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. A survey of convolutional neural networks: analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 6999–7019 (2021).

Weiss, K., Khoshgoftaar, T. M. & Wang, D. A survey of transfer learning.J. Big Data 3, 1–40 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Generalizing from a few examples: a survey on few-shot learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 53, 1–34 (2020).

Haralick, R. M., Shanmugam, K. & Dinstein, I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. SMC-3, 610–621 (1973).

Losson, O. et al. Color texture analysis using CFA chromatic co-occurrence matrices. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 117, 747–763 (2013).

Lowe, D. G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 60, 91–110 (2004).

Wang, Z. et al. Supervised heterogeneous sparse feature selection for Chinese paintings classification. J. Comput. Aided Des. Comput. Graph 25, 1848–1855 (2013). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Sheng, J. C. Automatic categorization of traditional Chinese paintings based on wavelet transform. Comput. Sci. 41, 317–319 (2014). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Sheng, J. C. & Jiang, J. M. Recognition of Chinese artists via windowed and entropy balanced fusion in classification of their authored ink and wash paintings (IWPs). Pattern Recogn. 47, 612–622 (2014).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Sun, M. et al. Brushstroke based sparse hybrid convolutional neural networks for author classification of Chinese ink-wash paintings. In Proc. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Image (ICIP) 626–630 (IEEE, 2015).

Sheng, J. C. & Li, Y. Z. Learning artistic objects for improved classification of Chinese paintings. Int. J. Image Graph 23, 1193–1206 (2018). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Zhou, Y. Research on Chinese painting image classification method based on improved convolutional neural network model. J. Jiamusi Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 39, 112–115 (2021). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Yu, Q. & Shi, C. An image classification approach for painting using improved convolutional neural algorithm. Soft Comput. 28, 847–873 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Recent advances of few-shot learning methods and applications. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 66, 920–944 (2023).

Xiao, Z. Research on Painting Image Classification based on Convolutional Neural Network (China Jiliang University, 2020) (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Chen, H. Y. Chinese Painting Image Classification Based on Deep Learning (Hangzhou Dianzi University, 2021) (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Li, K. et al. Dongba painting few-shot classification based on graph neural network. J. Comput. Aided Des. Comput. Graph 33, 1073–1083 (2021). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Xu, Q. H. & Qian, W. H. Dongba painting few-shot classification combining spatial information and distribution relationship. J. Comput. Aided Des. Comput. Graph. 35, 1417–1428 (2023). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Ding, Y. et al. TCP-RBA: semi-supervised learning for traditional chinese painting classification with random brushwork augment. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 46, 10653–10663 (2024).

Zhang, Y. & Yang, Q. A survey on multi-task learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 34, 5586–5609 (2021).

Dorozynski, M. Addressing class imbalance for training a multi-task classifier in the context of silk heritage. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. X-1/W1-2023, 175–184 (2023).

Bianco, S. et al. Multitask painting categorization by deep multibranch neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 135, 90–101 (2019).

Snell, J., Swersky, K. & Zemel, R. Prototypical networks for few-shot learning. In Proc. Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS, 2017).

Chen, J. et al. Research on few-shot paleontological fossil identification based on improved prototype network. Geol. Rev. 69, 1967–1979 (2023) (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Khan, M. A. H. et al. Few-shot classification and anatomical localization of tissues in SPECT imaging. In Proc. 2024 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium (NSS), Medical Imaging Conference (MIC) and Room Temperature Semiconductor Detector Conference (RTSD) (IEEE, 2024).

He, K. et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. 29th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

Caruana, R. Multitask learning. Mach. Learn. 28, 41–75 (1997).

Deng, Y. et al. Feature-guided multitask change detection network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 15, 9667–9679 (2022).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273 (1995).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323, 533–536 (1986).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proc. Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS, 2017).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (ACM, 2016).

Seiffert, C. et al. RUSBoost: a hybrid approach to alleviating class imbalance. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cyber. A 40, 185–197 (2009).

Radford, A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proc. International Conference on Machine Learning 8748–8763 (PMLR, 2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Chinese painting emotion classification based on convolution neural network and SVM. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 40, 74–79 (2017). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Yang, B. et al. Chinese painting image classification based on convolution neural network. Softw. Guide 18, 5–8 (2019). (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Guo, D. Research and Application of Chinese Painting Image Classification Method Based on Semi-supervised Learning (Communication University of China, 2023) (in Chinese with an English abstract).

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. CUCZDTJ2402), the Open Research Projects of the Key Laboratory (Grant No. 2021KFKT005), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62276240).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the current work. S.Z.B., Z.L.Y., and W.S. devised the study plan and wrote the paper. S.Z.B. and Z.L.Y. designed and illustrated the algorithm. Z.L.Y. and L.J.Y. arranged the data of experiment. S.Z.B. and W.S. supervised the entire process and provided constructive advice. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, Z., Zhang, L., Liu, J. et al. Material classification method of traditional Chinese painting image based on prototypical network. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01949-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01949-8

This article is cited by

-

A fuzzy LSTM framework for the application of Chinese art painting style classification

Discover Computing (2025)