Abstract

Karez, an ancient engineering marvel, utilizes gravity to transport underground water to the surface without external power. Typically, a karez comprises numerous shafts (vertical wells), and traditional mapping methods are both time-consuming and labor-intensive. To address these challenges, this study developed an integrated detection-screening framework for karez mapping. The karez shafts were detected by using high spatial resolution satellite imagery and deep learning architectures (Faster-RCNN, SSD, YoloV3, and MMDetection). Subsequently, a directed fan-shaped buffering method, combined with hierarchical clustering, was introduced to filter out misidentified shaft-like structures. Results showed that the MMDetection outperformed other models, achieving a mean average precision (mAP50-95) of 0.833. Field validation confirmed that the screening methods eliminated 90.20% of false shaft detections. This study has obtained the largest number of karez shafts to date in the study area, while providing a transferable technical framework for global applications in cultural heritage documentation and arid land water management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A karez is an underground tunnel with a gentle gradient that leads groundwater from the higher terrain to the lower-lying fields solely through the force of gravity without any biological or mechanical assistance1 (Fig. 1). It is a traditional earthen water management system that many scholars believe originated in ancient Persia (modern-day Iran)2,3, and can be found in many countries around the world, stretching from Japan, across Central Asia, Europe, North Africa, and further into Central and South America4. The karez is known by various names, including qanat or kariz in Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan5, khettara in Morocco4,6,7,8, galeria in Mexico9, falaj/aflaj in the United Arab Emirates and Oman10,11,12, foggara/fujihara in North Africa and the Levant13,14,15, puquios in Peru16, surangam in India17, and karez or kanerjing in China5. As seen in Fig. 1, this traditional hydraulic infrastructure typically comprises five key components, namely the vertical shafts, underground channels, an outlet, open channels, and a pool. Karez are being conserved very well in many countries and offering stable sources of water for irrigation and various other purposes. Iran, for instance, has the world’s largest karez network, with approximately 32,164 active systems discharging a total of about 9 billion cubic meters annually18. As a typical example of human-environment interaction in arid zones, the karez system embodies both an exceptional hydraulic engineering legacy and, more profoundly, a living cultural heritage that encodes centuries of indigenous ecological knowledge. Serving as a fertile oasis and a pivotal trade hub along the northern Silk Road, Turpan farmers in China also rely on karez water for their agricultural and daily activities. However, escalating water demands and the introduction of more efficient water acquisition technologies, such as electric pumping wells, have posed significant challenges to the maintenance of karez systems, leading to their decline in many countries19,20.

Even though facing the threat of abandonment, as an eco-friendly technology, the karez showed invaluable historical, cultural, and social significance in various aspects of modern society21. Therefore, it is imperative to thoroughly study the environmental and social impacts of karez systems in recent years by employing state-of-the-art techniques. Among these methods, geoengineering approaches, particularly the integration of remote sensing and geographic information system (GIS) techniques, have shown remarkable potential for assessing environmental impacts and developing plans for the restoration and safety of karez systems5. For instance, Megdiche-Kharrat et al. conducted a study on land use and the dynamics of vegetation cover in Wilayat Nizwa, Oman, using remote sensing images, and explained the utilization patterns of karez systems in the region to a certain extent22. The investigation of land use and land cover (LULC) changes on karez systems remains an active research frontier, as demonstrated by Al-Kindi et al., who assessed the impact of LULC changes on karez systems in northern Oman over a span of 36 years, yielding new understanding about the cascading effects of LULC changes on groundwater resources while establishing an evidence base for sustainable land management decisions in arid regions23. Equally concerning findings emerged from recent studies in Iran’s Mashhad plain, where researchers documented an alarming 94.41% loss of karez shafts over just six decades, primarily driven by uncontrolled agricultural expansion and urban development, highlighting the urgent need for innovative conservation approaches20. On the methodological front, Barbaix et al. made significant contributions by developing a comprehensive framework for analyzing diverse historical sources specific to karez landscapes in Turpan, systematically cataloging various archival materials along with detailed explanations of their processing methodologies24. Furthermore, Lou et al. quantitatively reevaluated the function of karez using remote sensing technology, concluding that the decline in karez usage weakens ecological stability and increases the ecosystem’s vulnerability to external factors25. In another study, Al-Kindi and Janizadeh leveraged LiDAR, Sentinel-2, and GIS data to derive variables related to LULC, as well as hydrological, topographical, and geological factors26. They employed various machine learning methods to model groundwater potential and emphasized the critical importance of evaluating existing groundwater datasets, facilities, and spatial datasets in designing systems capable of mapping karez based on geospatial and machine learning techniques. Together, these significant scientific advancements powerfully underscore the necessity for continued interdisciplinary research and the innovative application of modern technologies to effectively preserve and revitalize these ancient yet increasingly vulnerable water management systems.

Despite recent efforts and regulations introduced in many countries aimed at water conservation, groundwater table levels have been steadily declining and have recently reached historic lows27,28. This trend has led to a rapid decline in the functionality and number of karez systems21. The systematic identification and quantification of karez are crucial for prioritizing and validating mitigation measures, as well as for establishing accurate karez inventories. Governments and organizations often rely on limited information to implement remedial actions due to significant shortcomings in current detection methods and inventory systems. With advancements in remote sensing technology, spaceborne sensors have achieved sub-meter level spatial resolution in recent decades, resulting in image quality comparable to that of airborne images29. Satellite-based karez detection generally relies on identifying shape features of karez on the ground surface using visible band RGB images. However, manual detection of karez shafts from satellite images is a time-consuming and labor-intensive task due to the large number of shafts within each karez system.

Computer vision, a field that leverages machine learning techniques to train computers to see, interpret and understand the world around them, has demonstrated significant potential for automatic object detection30. Recent advances in object detection have demonstrated significant potential for cultural heritage preservation, such as identification and assessment of structural damages on heritage sites31,32, recognition and classification of architectural components33, as well as the extraction and analysis of symbolic elements from rock art imagery34. For instance, leveraging high-resolution imaging technology, Tang et al. conducted a detailed study on the Shanhaiguan Ancient City Wall in Qinhuangdao City, China, successfully identifying physical weathering patterns and visitor-induced scratches35. This research not only contributed to the development of an intelligent health monitoring tool for heritage buildings but also underscored the practical utility of computer vision in preserving architectural heritage. In a recent advancement, Shen et al. achieved a higher precision in detecting elements of ancient murals through the implementation of a lightweight multi-scale feature fusion network combined with a semantic enhancement model36. Moreover, the integration of computer vision with remote sensing data and advanced machine learning methods has emerged as a transformative approach in cultural heritage preservation, particularly in the detection and documentation of heritage sites37,38. This interdisciplinary fusion not only enhances the accuracy and efficiency of heritage preservation efforts but also opens new avenues for the systematic analysis and protection of cultural artifacts and historical landscapes.

These technological advances are equally applicable to karez detection using high spatial resolution satellite imagery and machine learning methods. Previous studies have demonstrated this potential, including Soroush et al., who employed CORONA images and deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to detect karez shafts in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, achieving a precision of 0.6239, and Li et al. used Google Earth data to train the YoloV5 model for extracting karez shafts in Turpan, China, and identified 82,493 shafts after post-processing40. In their subsequent study, Li et al. utilized CORONA images from 1970 to visually interpret the karez system and compared it with the karez system in 2020 to analyze spatial distribution variations and the impact of LULC changes on karez41. More recently, Buławka et al. used the black and white HEXAGON (KH-9) high-resolution spy satellite images from the 1970s and YoloV9 model to detect karez in selected areas of Afghanistan, Iran and Morocco, and developed a post-processing approach to eliminate most false detections with a higher precision42.

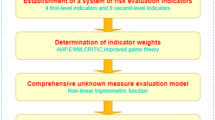

Yet, there has been a growing interest in developing karez detection and screening methods with broad field verifications. Although the karez system is widely distributed globally, numerous regions, including Turpan, which boasts the highest number of karez in China, still lack a comprehensive database of these ancient water systems. The mapping methods need to be continuously improved due to the variations of karez distribution in different regions. Therefore, to address this issue in a more tractable manner, this study focuses on the karez systems in China’s Turpan Basin. The study endeavors to establish a detection-screening workflow, with the overarching aim of constructing a comprehensive and detailed karez database. It delves into an in-depth evaluation of multiple deep learning-based object detection algorithms, meticulously comparing their performance to determine the most effective approach for accurately detecting karez shafts. Subsequently, a screening workflow is devised, integrating directed fan-shaped buffering and clustering techniques. These innovative techniques are specifically designed to filter out false positives (erroneously identified shafts), thereby enhancing the precision and reliability of the detection process. The workflow introduced in this study has the potential to be adapted for use in other regions, fostering the creation of more robust local and global karez databases.

Methods

The main workflow for karez mapping is illustrated in Fig. 2. Initially, remote sensing data of the study area were downloaded and pre-processed. Subsequently, a portion of the karez shafts was annotated for training deep learning models, and the karez shafts in the whole area were detected by using the best model. Following this, the detected shafts undergo a screening process employing various methods. After screening, the shafts were clustered to identify those belonging to individual karez systems. Ultimately, the shafts were sorted, and karez lines were generated.

Study area

In China, the karez is predominantly found in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, particularly in the Turpan Basin, which lies at the southern base of the Tianshan Mountain range (Fig. 3). Turpan is a renowned closed basin characterized by an extremely arid climate. The basin’s terrain exhibits substantial altitude variations, with the surrounding mountains reaching a maximum height of 5445 m at Tianshan Mountain and the basin’s lowest point, Ayding Lake, sitting at 154 m below sea level. These altitude differences significantly influence the basin’s climate and water distribution. Given the large elevation drop, the abundant meltwater from the mountains, and the arid conditions, the excavation of karez became essential for irrigation and other water needs. The historical record of the karez extends back to the Han Dynasty in China18. Notably, the karez in Turpan were recognized as one of the World Heritage Irrigation Structures on September 3, 202443. According to Kobori19, there were 1237 karez systems in Turpan in 1957, which declined to 829 in 1980, with a combined length of approximately 2360 km. During the Third National Cultural Heritage Survey conducted between 2007 and 2011, 1108 karez were archived as cultural heritage in Turpan, which consists 71.95% of total in China44.

Data collection and preprocessing

Bing Virtual Earth images with a spatial resolution of 0.50 m were downloaded using QGIS software version 3.38.0. This resolution allowed for clear identification of most karez shafts. The selection of the study area was based on the distribution of human activities and the presence of an oasis. Training deep learning models and performing object detection on large image datasets requires substantial computation resources. To streamline downloading, the study area was divided into 65 blocks, each measuring 30 km by 16 km, as shown in Fig. 3d. Subsequently, each of these blocks was further subdivided into nine equal smaller blocks to facilitate the detection of karez shafts using a deep learning model.

The Copernicus DEM data, featuring a spatial resolution of 90 m, was downloaded from the Copernicus website (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/) to generate slope and aspect angle data. However, some regions were identified as flat areas with the 90 m resolution DEM data. To address this, the DEM data was resampled to 500 m resolution, allowing for the accurate derivation of aspect angle in those previously problematic areas.

Preparation of training data

The blocks numbered 32, 42, and 59 in Fig. 3d were selected for labeling karez shafts due to their representative characteristics. The shafts located in various environments were labeled utilizing the ArcGIS Pro 3.1.5 software, resulting in a total of 5825 karez shafts being marked with circular symbols, as depicted in Fig. 4. The PASCAL Visual Object Classes method within ArcGIS Pro was utilized to generate the training data. The output tile size was set to 256 pixels, with strides of 128 pixels in both the X and Y directions. No rotation angles were applied for image data augmentation. Consequently, a total of 8395 images were created, each with dimensions of 3 * 256 * 256, where three represents the red, green, and blue channels, and 256 denotes the size in both the X and Y directions. Furthermore, one image with 10 km by 5.33 km from the block of 35 was selected to test the models, in which 1607 shafts were labeled.

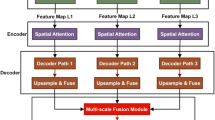

Deep learning models for karez shaft detection

Object detection, a cornerstone task in computer vision, involves recognizing and locating diverse objects within visual data, thereby empowering machines to interpret and comprehend their surroundings45. Various object detection algorithms exist, and for the purpose of karez shaft detection, the deep learning library of ArcGIS Pro 3.1.5 was used. Specifically, the Faster R-CNN, SSD (Single Shot Multibox Detector), YOLOv3 (You Only Look Once version 3), and MMDetection (OpenMMLab Detection Toolbox) were implemented, each equipped with different backbone models. For Faster R-CNN, SSD, and MMDetection, ResNet34 and ResNet50 were used as the backbone models, while DarkNet53 was employed for YOLOv3. The parameters of these deep learning models were detailed in Table 1.

Faster R-CNN is an object detection model that builds upon Fast R-CNN by incorporating a Region Proposal Network (RPN) in conjunction with the CNN model46. The RPN shares convolutional features with the detection network across the entire image, thereby facilitating region proposals at minimal computational cost. As a fully convolutional network, the RPN simultaneously predicts object boundaries and foreground probability scores at each spatial position. Trained end-to-end, the RPN generates high-quality region proposals that Fast R-CNN subsequently utilizes for detection. Notably, Faster R-CNN and its RPN component were instrumental in achieving 1st-place wins in several tracks of the ILSVRC and COCO 2015 competitions.

SSD is an advanced object detection method that employs a single-stage detection network to efficiently and accurately detect objects in images. This network integrates predictions from multiscale features, enabling it to capture diverse spatial resolutions and contextual information47. Unlike two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN, which involve a separate region proposal stage followed by classification and bounding box refinement, SSD performs detection in a single pass, making it computationally more efficient and faster.

The YOLOv3 algorithm, introduced by Redmon and Farhadi in 2018, initially divides an image into a grid48. Each grid cell is tasked with predicting a certain number of bounding boxes (also known as anchor boxes) around objects that closely match predefined classes, assigning a high confidence score to these predictions. Each bounding box has a respective confidence score of how accurately it assumes that prediction should be. Importantly, each bounding box is designated for a single object. These bounding boxes are generated through clustering the dimensions of the ground truth boxes from the training dataset, allowing YOLOv3 to identify the most common object shapes and sizes. Unlike systems such as R-CNN and Fast R-CNN, YOLOv3 can simultaneously perform classification and bounding box regression. This dual capability ensures that YOLOv3 provides both efficient and precise predictions for the detected bounding boxes.

MMDetection is an object detection toolbox that encompasses a comprehensive collection of object detection and instance segmentation algorithms, along with pertinent components and modules. It distinguished itself by winning the detection track of the COCO Challenge 201849, showcasing its effectiveness and robustness in the field of computer vision.

After training, the model with the highest precision was selected to detect karez shafts across the entire study area. Table 2 presents the parameters employed for detecting karez shafts using the optimal model. The training of the data and the detection of karez shafts were performed on a graphic workstation equipped with a 13th Gen Intel® Core™ i9-13900KF processor clocked at 3.00 GHz, 128 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU.

Precision (P), recall (R), f1-score, mean average precision at IoU = 0.50 (mAP50), and mean average precision at IoU = [0.50, 0.55, …, 0.95] (mAP50-95) were used to evaluate the models on test data using the “compute accuracy for object detection” function of ArcGIS Pro.

Post-processing of detected shafts

The initially detected karez shafts were square-shaped. For further processing, these polygons were converted into point features, ensuring that the center of each square was recorded as a single shaft. Given the presence of some incorrectly detected or missing shafts, it is essential to employ screening methods to achieve more accurate data. In this study, five steps of screening were used to eliminate incorrectly detected shafts, as outlined below:

The first step is the deletion of points too close together (<5 m) to avoid duplication. The downloaded image patches were overlapped to a certain extent to avoid missing shafts, and generally, the shafts should not be positioned too close to each other. Therefore, any shafts found within a distance of less than 5 m from another shaft were deleted to eliminate duplication. This procedure was performed using the ArcGIS Pro software.

Next step is the deletion of points on larger slopes. Based on experience, shafts located on slopes steeper than 20° were removed. The slopes were calculated using the Copernicus DEM with a spatial resolution of 90 m

In the third step, the directed fan-shaped buffer method was conducted. Typically, the karez shafts distribute linearly and extend predominantly from higher terrain to lower terrain. To accommodate this, aspect angles of the terrain were derived using the Copernicus DEM with a spatial resolution of 500 m. For each karez shaft, fan-shaped buffer zones were created, encompassing a fan angle range of aspect ±45° (Fig. 5). Recognizing that some karez lines do not strictly adhere to the aspect angle, slight adjustments were made to the angle for certain areas (this adjustment was controlled in ±20°). The largest shaft distance was selected as the buffer distance in different patches. Subsequently, only the intersected buffer zones were selected, and shafts located outside these zones were removed. This step can effectively screen out the isolated points that did not align with the direction of the karez lines and out of the largest shaft distance. This process was executed within the Python environment of ArcGIS Pro.

Subsequently, small clusters were screened out based on a larger distance threshold. Utilizing the single-linkage clustering method, clusters were formed with a distance threshold set at 0.001°. Then, clusters containing three or fewer points were removed. This process was facilitated using the SciPy open-source Python library.

Finally, manual adjustments were applied. Despite the preceding steps, some erroneous points remained. Therefore, regions of interest were delineated based on expert experience, specifically excluding mountainous areas and other regions where karez are unlikely to be found. Following this, a manual screening process was conducted to eliminate points that were not linear or highly irregular, combined with satellite images. This step was executed using ArcGIS Pro software.

Line generation for karez segments

Data clustering organizes objects into groups based on their similarity. Among the hierarchical clustering methods, the method stands out by offering multiple, layered partitions. It employs divisive and agglomerative approaches to split or merge clusters, respectively, based on measures of dissimilarity or similarity that are tailored to accommodate diverse data sets and applications50. Hierarchical clustering is widely utilized in cluster analysis for data mining due to its ability to facilitate the visualization of similar objects grouped into clusters. In each iteration of hierarchical clustering, specific objects or clusters are linked together based on a criterion referred to as the “Linkage Criteria”. Single-linkage clustering is particularly advantageous when aiming to gain insights into the fine granularity of the data. It performs effectively when clusters naturally exhibit a chain-like or non-compact structure51,52. The fundamental principles of this method are outlined in the paper by Manning and Schutze51.

To identify the shafts belonging to the same karez system, the single-linkage clustering method of the hierarchical clustering approach was employed. The clustering analysis was executed using the SciPy open-source Python library. Due to variations in the distances between shafts across different regions, different maximum distance thresholds were used for clustering shafts in various blocks. However, some karez shafts were undetected either because they had been destroyed or because they were not sufficiently distinctive compared to their surroundings, resulting in shafts belonging to the same karez segment being mistakenly clustered into several separate parts. Conversely, some shafts belonging to different karez were too close to each other and were inadvertently clustered as part of the same karez. In such instances, the automatic clustering method alone was insufficient to yield accurate clusters. Therefore, manual adjustments were necessary to correct these clusters. Ultimately, the clusters from different patches were merged and assigned the same cluster IDs.

After clustering, the shafts are sorted utilizing the “sort” tool in ArcGIS Pro. The X coordinates are generated specifically for shafts where the karez lines are oriented in an east-west direction and are subsequently employed for the sorting process. Ultimately, the “Points to Line” tool was utilized to generate the lines for karez segments.

Field verification

A comprehensive field verification campaign was conducted from 28th October 2024 to 10th April 2025 as an integral component of the fourth National Cultural Heritage survey. The investigation encompassed all identified karez shafts within the study area through systematic ground-truthing procedures. Four specialized survey teams were deployed, with each team consisting of four qualified members. All members were equipped with mobile devices running the Omap (Ovi Interactive Map) application (Beijing Yuansheng Huawang Software Co., Beijing, China), enabling real-time visualization of detected shaft locations and navigation to target sites via satellite imagery. To ensure complete documentation of the extensive karez networks, each team was equipped with a DJI Mavic 3 drone system (DJI Innovations Science and Technology Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China) for aerial photography, particularly crucial for shafts extending several kilometers in length. Every identified shaft underwent rigorous field verification, with precise location data collected and detailed distribution maps produced based on direct field observations.

Results

Model performances

Table 3 presents the performance of various deep learning models based on the training data. As indicated, when employing ResNet50 as the backbone model, the MMDetection exhibited the best performance with a precision of 0.812, surpassing other models. Among the backbone models, ResNet50 demonstrated superior performance compared to ResNet34. Additionally, the SSD had the shortest training time, with each epoch taking only 4–7 min. Despite setting the maximum number of epochs to 200, most models were terminated early due to a lack of further improvement. Table 4 shows the performance of various deep learning models based on the test data. As seen, the MMDetection with the ResNet50 as backbone model showed the best performance with an overall precision (mAP50-95) of 0.833.

Karez shaft detection with the best model

The MMDetection, utilizing ResNet50 as its backbone model, was chosen for detecting karez shafts due to its superior performance among other models. As illustrated in Fig. 6, model performance varied significantly across different confidence thresholds. Lower thresholds yielded higher overall precision but resulted in more misidentified shafts (false positives, Fig. 6a). Conversely, higher thresholds improved detection precision but increased false negatives (lost detection), leading to significant shaft under-detection (Fig. 6b). To optimize this trade-off between false positives (requiring extensive post-processing) and false negatives (resulting in missed detections), this study chose the confidence threshold of 0.35.

Consequently, a total of 284,500 shafts were identified with a confidence threshold of 0.35 (Fig. 7). Blocks in which lacking linear clustering of points were excluded from further processing. After applying the directed fan-shaped buffer method for screening, 186,848 shafts remained. Following the removal of clusters containing fewer than three points, the number of shafts was reduced to 149,932. Subsequently, regions of interest were delineated based on expert experience and the distribution patterns of the shafts. Shafts located outside these defined regions were then excluded, leaving 107,510 points. These screening methods eliminated 90.20% of false shaft detections. Lastly, a manual screening process was conducted, further narrowing down the number of shafts to 88,288 (blue points in Fig. 7).

Cluster results and karez segment line generation

By combining automatic clustering with manual adjustments, a total of 3984 clusters were successfully obtained, which were subsequently used to generate karez segment lines (as shown in Fig. 8). These karez segment lines covered a total length of 2527.24 km, with the longest individual karez segment measuring 7.79 km and an average length of 0.63 km. For better visualization, the karez detection area was divided into nine rectangles, and detailed enlargements of these parts are provided in Figs. 9 and 10. Notably, some previously unrecorded karez, such as those in block four and the northwest parts of block nine (depicted in Figs. 9 and 10), were discovered and subsequently verified through field surveys.

After the field verification survey, 99.3% of the shafts that were identified and screened in this study proved to be real karez shafts, as others were shaft-like objects with linear distribution. However, more than ten thousand karez shafts could not be identified from satellite images, even manually. It is mostly because they were covered by cement structures or similar soil for mitigation and safety purposes, particularly in residential areas, and some were under vegetation such as trees. Furthermore, some shafts have been eroded and disappeared in recent years, and the shafts could not be found even in the survey.

Discussion

There are two primary factors that hinder the performance of the deep learning model: misidentified shafts and missing shafts. The best-performing model attained an overall precision of 0.833, which suggests cautious predictions but also indicates some missed detections. Since some karez shafts are not readily apparent in aerial images, the detection confidence coefficients for these were lower. However, they can be distinguished based on the distribution patterns of neighboring shafts, as they are linearly distributed. Consequently, a lower confidence threshold (0.35) was set to obtain more complete data. As a result, more karez shafts were detected, but this also led to an increase in misidentified shaft-like objects. The following sections delve further into the specifics of these misidentified and missed karez shafts.

The first issue is the misidentification of karez shafts. Numerous shaft-like objects, such as graves, earth mounds, circular marshlands, borrow pits, and other circular ground features with noticeable color differences from their surroundings, were incorrectly detected as karez shafts Fig. 11). These objects were easily misclassified as karez shafts due to their similar appearance in aerial images. Identifying them manually, especially when viewed individually, even remains challenging. Generally, the shafts of a karez should form a linear pattern, and a single shaft can be accurately identified when observed alongside others, even if it is not particularly prominent. The reason for these misidentifications can also be traced back to the training data itself, where these less obvious shafts were labeled as karez shafts along with others. Unfortunately, deep learning models focus solely on identifying individual objects without considering their overall distribution. However, the goal of this study was to detect as many karez shafts as possible to build a comprehensive database. This, in part, explains why the model precision of this study was lower; the training data contained samples that were easily confused with other objects. Consequently, post-processing is essential to filter out the misidentified shafts.

The second issue concerns missing karez shafts. Some karez shafts were eroded or buried naturally, while others have been covered to prevent landfill or for safety reasons. Consequently, it is extremely challenging to distinguish them from the surrounding soil even for manual identification. Fig. 12 illustrates this spectrum of detectability: well-preserved shafts (yellow frames in Fig. 12a–c) are readily identifiable in both satellite and aerial imagery, while severely eroded examples (red frames) challenge even expert analysis. Cloud covers further compromise visibility. These limitations currently necessitate field verification to complete comprehensive inventories, though future integration of LiDAR or multi-temporal analysis could mitigate such constraints.

This study developed an innovative pipeline combining directed fan-shaped buffering with clustering techniques for false positive removal in karez shaft identification. The automated screening effectively eliminated most misidentified points (Fig. 13b), though some ambiguous cases required manual verification. Furthermore, during the clustering process, the shafts of some karez were divided into multiple clusters due to missing or undetected shafts, while others were merged because of the proximity of shafts from different karez channels (Fig. 13d). These systematic errors necessitated targeted manual correction (Fig. 13e), demonstrating both the efficacy and current limitations of automated approaches in complex archeological feature identification.

a Original detected shafts. b Shafts after being screened by the directed buffer method. c Shafts after manual screening. d Clustering by using the single-linkage hierarchical clustering method. e Clusters after manually adjusting. f Generated karez lines according to clusters. The different colors represent the different clusters.

The advantage of the directed fan-shaped buffer method is that it can screen out the shafts that do not strictly follow the linear distribution of existing studies. For instance, in their study, Li et al. used the circular buffering method for screening the shafts40. Although the method can screen out most of the misidentified shafts, it cannot distinguish some of the irregularly distributed shaft-like objects. For instance, Fig. 14a shows several shaft-like objects that were detected as karez shafts in higher confidence coefficients from the MMDetection method (Fig. 14b). If the circular buffering method were used, then all shafts would remain due to all the circular buffers being intersected with each other (Fig. 14c). If the directed fan-shaped buffer method were used, then only two groups of buffers (B and C, F, and G in Fig. 14d) were intersected and effectively screened out. Furthermore, they demonstrated that the YoloV5 model achieved a precision of 0.86 using Google Earth images, outperforming the best model of this study. However, it is worth noting that the shafts in the western part and the mountain regions in the northwestern part were not presented in their study, assuming they were not included in the shaft detection procedure. Additionally, after screening, their study identified 82,493 shafts, which is approximately 5500 fewer than the shafts obtained in this study. This study represents the first field-validated comprehensive inventory, addressing a critical gap in previous work.

Most karez are oriented from higher terrain to lower plains. However, some karez lines do not strictly adhere to the aspect angle, resulting in the direction of fan-shaped buffers not aligning with the karez line. This necessitates caution when using the directed buffer method, although it is not a frequent occurrence. In such instances, the direction of the buffer should be adjusted to align with the karez line. Furthermore, some shafts from different karez are positioned too closely to each other, while others intersect, posing challenges for clustering (as Fig. 15, even though it is not the common case). Therefore, fully automated mapping of karez shafts is challenging, and manual adjustments are essential to achieve more accurate data. Consequently, semi-automated methods should be employed for karez mapping.

The effects of fan-shaped buffer angles and distances were demonstrated in Tables 5 and 6 on test dataset: with a fixed buffer distance, a smaller angle reduced false positives (misidentified shafts) but increased false negatives (lost detections), with the best overall precision at 30° (Table 5); similarly, with a fixed buffer angle, a smaller distance decreased false positives but raised false negatives, peaking in precision at 115 m (Table 6). Table 7 compared the circular buffering method (180°, 57.5 m, equivalent to the 115 m fan-shaped buffer), which shows lower overall precision due to more false positives. Although the directed fan-shaped method yielded one additional false negative, it eliminated 42 more false positives than the circular approach.

As shown in Fig. 8, the majority of karez wells were concentrated near settlements and farms. However, there are also some karez located in mountainous regions, even in the absence of irrigation land. It is possible that these karez were only used to provide drinking water for humans and livestock. The placement of these karez in dry streambeds or ephemeral river valleys is geomorphologically similar to those in the wadis near Turpan city53. Some similar examples can be found in the northern parts of Flaming Mountain (patch number 32). The shafts are located near but almost never right on top of shallow dry stream beds, undoubtedly, to minimize any potential flood damage. These karez are often not very long, though some examples have proven to run very deep (several tens of meters). This would often imply a rather large labor investment for minimal agricultural profit since these valleys and wadis cannot accommodate large swatches of fields. This does strengthen the hypothesis that these karez might have been constructed to mostly provide drinking water. Another argument would be the location of the newly recognized mountainous karez lines. These are placed along known historical routes through the Tian Shan Mountain. Peculiarly, the use of karez to provide shepherds and herd with water during transhumance practices has been attested in oral tales and karez names as recent as the 19th century54. Consequently, it is unwise to restrict the search for karez solely to areas near agricultural regions or oases. The rather narrow location and short karez length make it easy for these systems to be missed with lower resolution data.

The fourth National Cultural Heritage survey, running from November 2023 to June 2026, serves as the foundation for China’s heritage policy-making and conservation work. This nationwide initiative provides essential data to guide both legislative decisions and practical preservation efforts across the country’s cultural sector55. Building a comprehensive heritage database is crucial for enabling thorough analysis and developing effective preservation strategies. The karez systems represent the most extensive heritage features in the Turpan Basin. They display remarkably complex distribution patterns compared to other heritage types. A single karez may consist of dozens to hundreds of shafts with multiple branches, often covering large geographical areas. Therefore, the mapping results from this study have proven invaluable, providing accurate location data that significantly improves field survey efficiency and contributes to building a more complete karez database. Although many karez have been abandoned due to various factors including natural disasters, frequent collapses with high maintenance costs, and changes in settlement and grazing patterns, they still hold immense value, containing important cultural, historical, geological and ecological information21,25,56,57. They also provide insights into environmental changes in surrounding regions. For example, some karez were abandoned during construction when no water was found, while others were discontinued when they could no longer provide a reliable water supply. These types of karez typically lack associated residential areas. Other karez were used exclusively as water sources for humans and livestock in grazing areas, where only sheepfolds were constructed. Moreover, the spatial and temporal distribution of karez offers valuable evidence for analyzing ancient settlement patterns. A complete karez database enables informed decisions about which systems should be preserved as cultural heritage and which can be abandoned. Such databases also support the protection and reconstruction of hydraulic infrastructure, helping to optimize water resource utilization and improve water supply efficiency58. Finally, the comprehensive karez dataset has multiple practical applications in modern planning. Some abandoned karez without historical significance have been repurposed, as observed in this study’s survey, serving new functions like surface water diversion in some areas or urban sewage drainage in others59. This demonstrates the continued relevance and adaptability of these ancient systems.

Remote sensing and deep learning methods have demonstrated considerable potential in archeological prospecting. Despite the confusing appearance of karez shafts in aerial images and their irregular distribution characteristics, these methods, combined with screening and clustering techniques, can effectively map karez shafts. Compared to other studies, the approach of this study detected the karez shafts over a broader area and generated more comprehensive karez lines. However, while this study has identified the most extensive collection of karez shafts in the study area to date, several methodological limitations warrant careful consideration. First, despite achieving unprecedented detection rates, certain shafts remain challenging to identify through current methods. This is particularly true for shafts that are partially collapsed, heavily vegetated, or located in complex terrain, where RGB imagery alone proves insufficient for reliable detection. The spectral limitations of visible light data often fail to capture subtle surface anomalies characteristic of degraded shafts. The potential advantages of multispectral imagery and LiDAR for karez detection should be incorporated in future studies, although they were constrained by several factors in this study. The different objects can be easily detected by different spectral bands, such as vegetation60, water61, or soil composition62. For example, the additional inclusion of NIR reflectance images enhances the classification ability of models, particularly when the presence of vegetation and biogenic materials63. However, the minimal spectral contrast between karez shafts and surrounding arid landscapes limited the effectiveness of multispectral data. Furthermore, by creating precise 3D models, LiDAR data can be used to extract detailed information about heritages64. However, available LiDAR datasets lacked sufficient resolution to reliably detect the narrow shaft diameters characteristic of karez systems (shaft diameters of 1–2 m). While high-resolution airborne LiDAR and multispectral data could offer improvements for targeted investigations, their prohibitive costs and limited coverage make them impractical for large-scale applications. These constraints reinforce the rationale for prioritizing high-resolution RGB imagery as the most viable option for regional-scale mapping of karez systems, though future work could explore targeted fusion of these complementary data sources in critical areas, such as where the karez shafts were partially buried, obscured, or eroded.

The temporal constraints imposed by the fourth National Cultural Heritage survey necessitated the use of ArcGIS Pro’s built-in deep learning libraries, which, while effective, represent a conservative approach to model implementation. These pre-packaged solutions lack the flexibility to incorporate emerging architectural innovations such as transformer-based networks65 or hybrid convolutional-attention mechanisms66 that have shown promise in similar tasks. As the field of deep learning evolves, future work should explore cutting-edge frameworks like vision transformers or diffusion models67, which may better capture the complex spatial patterns of karez systems. This would particularly benefit the detection of partially obscured shafts where traditional CNNs struggle. Furthermore, the training data collection methodology of this study, though rigorous, could be enhanced through more systematic approaches. Current training samples were necessarily limited by the urgent survey timeline, potentially introducing certain biases. A more robust future approach might employ random sampling across different geomorphological units and preservation conditions. The development of standardized methods for archeological feature labeling in remote sensing data would significantly improve model generalizability.

The screening method which introduced in this study, while advancing automated processing, still requires manual intervention at multiple stages. This is primarily due to the inherent irregularity in karez shaft spatial distributions, varying preservation states across different geological substrates, and occasional false positives from modern linear features like pits along roads or electric power poles. Subsequent research should focus on developing fully automated solutions, potentially through advanced spatial statistics for linear feature clustering and context-aware screening algorithms that incorporate topographical features, historical settlement data, and geological constraints. Integration with GIS-based hydrological modeling tools68 may help distinguish true karez shafts from other linear features based on their characteristic alignment with groundwater flow paths. Additionally, the current approach does not fully leverage temporal data that could provide crucial contextual information. Historical imagery analysis could help differentiate active from abandoned shafts based on temporal persistence patterns, while multi-temporal InSAR data might reveal subtle subsidence features associated with underground karez tunnels. The incorporation of such temporal dimensions could significantly reduce false positive rates.

Finally, while the methods in this study have proven effective in the study area, their transferability to other regions with different geological and climatic conditions remains untested. Future work should validate the approach across diverse arid region environments to develop truly robust, generalizable methods for this ancient groundwater infrastructure mapping. This cross-regional validation would not only test methodological robustness but could also yield comparative insights into different civilizations’ adaptations to arid environments. This, in turn, will contribute to a better understanding, preservation, and sustainable management of these ancient water systems, safeguarding their historical and cultural significance for future generations.

Data availability

The training data and scripts will be made available on request.

References

Abudu, S. et al. A karez system’s dilemma: a cultural heritage on a shelf or still a viable technique for water resiliency in arid regions, in Socio-Environmental Dynamics along the Historical Silk Road (eds Yang, L.E. et al.) 507–525 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

English, P. W. The Origin and Spread of Qanats in the Old World. 12 (1968).

Noori, R. et al. Anthropogenic depletion of Iran’s aquifers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2024221118 (2021).

Hayes-Rich, E. et al. Searching for hidden waters: the effectiveness of remote sensing in assessing the distribution and status of a traditional, earthen irrigation system (khettara) in Morocco. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 51, 104175 (2023).

Ebrahimi, A. et al. Kariz (Ancient Aqueduct) system: a review on geoengineering and environmental studies. Environ. Earth Sci. 80, 236 (2021).

Faiz, M. E. & Ruf, T. An introduction to the khettara in Morocco: two contrasting cases. in Water and Sustainability in Arid Regions: Bridging the Gap Between Physical and Social Sciences, (eds. Schneier-Madanes G., Courel, M.-F.) 151–163 (Springer, 2010).

Beraaouz, M. et al. Khettaras in the Tafilalet oasis (Morocco): contribution to the promotion of tourism and sustainable development. Built Herit. 6, 24 (2022).

Lightfoot, D. R. Moroccan khettara: traditional irrigation and progressive desiccation. Geoforum 27, 261–273 (1996).

Palerm-Viqueira, J. Las galerías filtrantes o Qanats en México: introducción y tipología de técnicas. Agric. Soc. y. Desarro. 1, 133–145 (2004).

Al-Marshoudi, A. S. & Sulong. J. The Aflaj Systems in the Sultanate of Oman: its traditional-engineer construction and operation. In Proc. AWAM International Conference on Civil Engineering 2022 (Springer Nature, 2024).

Remmington, G. Transforming tradition: the aflaj and changing role of traditional knowledge systems for collective water management. J. Arid Environ. 151, 134–140 (2018).

Alsharhan, A. S. & Rizk, Z. E. Aflaj Systems: history and factors affecting recharge and discharge, in Water Resources and Integrated Management of the United Arab Emirates (eds Alsharhan A. S. & Rizk, Z. E.) 257–280 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Boutadara, Y., Remini, B. & Benmamar, S. The foggaras of Bouda (Algeria): from drought to flood. Appl. Water Sci. 8, 162 (2018).

Kendouci, M. A. et al. The impact of traditional irrigation (Foggara) and modern (drip, pivot) on the resource non-renewable groundwater in the Algerian Sahara. Energy Procedia 36, 154–162 (2013).

Boualem, R., Bachir, A. M. S. & Rabah, K. The foggara: a traditional system of irrigation in arid regions. Geosci. Eng. 60, 30–37 (2014).

Lasaponara, R., J. Lancho, R. & Masini, N. Puquios: the Nasca response to water shortage, in The Ancient Nasca World: New Insights from Science and Archaeology (eds Lasaponara, R., Masini, N., Orefici, G.) 279–327 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Joji, V. S., Gayen, A. & Saha, D. Harvesting of water by tunnelling: a case study from lateritic terrains of Western Ghats, India. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 130, 202 (2021).

Mostafaeipour, A. Historical background, productivity and technical issues of qanats. Water Hist. 2, 61–80 (2010).

Kobori, I. Notes from the Turpan Basin: pioneering research on the karez. in Water and Sustainability in Arid Regions: Bridging the Gap Between Physical and Social Sciences (eds. Schneier-Madanes G., Courel, M.-F.) 139–149 (Springer, 2010).

Maghrebi, M. et al. Anthropogenic decline of ancient, sustainable water systems: qanats. Groundwater 61, 139–146 (2023).

Abudu, S. et al. Vitality of ancient karez systems in arid lands: a case study in Turpan region of China. Water Hist. 3, 213–225 (2011).

Megdiche-Kharrat, F., Ragala, R. & Moussa, M. Mapping land use and dynamics of vegetation cover in Southeastern Arabia using remote sensing: the study case of Wilayat Nizwa (Oman) from 1987 to 2016. Arab. J. Geosci. 12, 450 (2019).

Al-Kindi, K. M. et al. Assessing the impact of land use and land cover changes on Aflaj Systems over a 36-year period. Remote Sens. 15, 1787 (2023).

Barbaix, S. et al. The use of historical sources in a multi-layered methodology for karez research in Turpan, China. Water Hist. 12, 281–297 (2020).

Lou, H. et al. Quantitative reevaluation of the function of Karez using remote sensing technology. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112249 (2024).

Al-Kindi, K. M. & Janizadeh, S. Machine learning and hyperparameters algorithms for identifying groundwater Aflaj potential mapping in semi-arid ecosystems using LiDAR, Sentinel-2, GIS data, and analysis. Remote Sens. 14, 5425 (2022).

Noori, R. et al. Decline in Iran’s groundwater recharge. Nat. Commun. 14, 6674 (2023).

Maghrebi, M., Noori, R. & AghaKouchak, A. Iran: renovated irrigation network deepens water crisis. Nature 618, 238 (2023).

Gui, S. et al. Remote sensing object detection in the deep learning era—a review. Remote Sens. 16, 327 (2024).

Chai, J. et al. Deep learning in computer vision: a critical review of emerging techniques and application scenarios. Mach. Learn. Appl. 6, 100134 (2021).

Pathak, R. et al. An object detection approach for detecting damages in heritage sites using 3-D point clouds and 2-D visual data. J. Cult. Herit. 48, 74–82 (2021).

Chu, Y.-C. et al. Automated wall moisture detection in heritage sites based on convolutional neural network (CNN) for infrared imagery. Appl. Sci. 15, 6495 (2025).

Gao, C. et al. Applying optimized YOLOv8 for heritage conservation: enhanced object detection in Jiangnan traditional private gardens. Herit. Sci. 12, 31 (2024).

Huo, D., Yang, S. & Hou, M. Using the improved YOLOv7-Seg model to segment symbols from rock art images. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 16 (2025).

Tang, H. et al. Application of object detection algorithm for efficient damages identification of the conservation of heritage buildings. Archaeol. Prospect. 31, 233–247 (2024).

Shen, J. et al. An algorithm based on lightweight semantic features for ancient mural element object detection. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 70 (2025).

Anand, Dravid. T., Jayanth, J. T. Deep learning applications for identifying and detecting heritage sites. In Proc. International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT) (IEEE, 2024).

Trier, Ø. D., Reksten, J. H. & Løseth, K. Automated mapping of cultural heritage in Norway from airborne lidar data using faster R-CNN. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs.Geoinf. 95, 102241 (2021).

Soroush, M. et al. Deep learning in archaeological remote sensing: automated qanat detection in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Remote Sens. 12, 500 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Automatic mapping of karez in Turpan Basin based on Google Earth images and the YOLOv5 Model. Remote Sens. 14, 3318 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Impact analysis of land use and land cover change on karez in Turpan Basin of China. Remote Sens. 15, 2146 (2023).

Buławka, N., Orengo, H. A. & Berganzo-Besga, I. Deep learning-based detection of qanat underground water distribution systems using HEXAGON spy satellite imagery. J. Archaeol. Sci. 171, 106053 (2024).

Liqiang, H. Four Ancient Projects Added to WHIS (China Daily, accessed 6th October 2024) https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202409/04/WS66d7b55ea3108f29c1fc9ff2.html#:~:text=Conveying%20water%20from%20deep%20underground%20to%20the%20surface%20and.

Cultural Relics Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, X. Immovable Cultural Relics: Turpan District Volume (Xinjiang Fine Arts Photography Publishing House, 2015)

Amjoud, A. B. & Amrouch, M. Object detection using deep learning, CNNs and vision transformers: a review. IEEE Access 11, 35479–35516 (2023).

Ren, S. et al. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 39, 1137–1149 (2017).

Liu, W. et al. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. in Computer Vision – ECCV 2016. 2016. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Redmon, J. & Farhadi A. YOLOv3: an incremental improvement. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.02767 (2018).

Chen, K. et al. MMDetection: open MMLab detection toolbox and benchmark. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.07155 (2019).

Ran, X. et al. Comprehensive survey on hierarchical clustering algorithms and the recent developments. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 8219–8264 (2023).

Manning, C.D. & Schütze, H. Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing (The MIT Press, 1999)

Manning, C. D., Raghavan, P. & Schütze, H. Introduction to Information Retrieval (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Barbaix, S. et al. An integrated approach to modelling the interaction of the natural landscape and the karez water system in Turpan (Xinjiang, P.R.C.). Landsc. Res. 47, 1–19 (2022).

Liu, X. & Yilihan, A. Watching the Karez: A Documentary of the First Phase of the Repair and Reinforcement Project (Xinjiang People’s Publishing House, 2012).

Chen, J. A Preliminary Study of The Fourth National Cultural Heritage Survey (Hakka Cultural Heritage Vision, 2024).

Endreny, T. A. & Gokcekus, H. Ancient eco-technology of qanats for engineering a sustainable water supply in the Mediterranean Island of Cyprus. Environ. Geol. 57, 249–257 (2009).

Ebrahimi, A., Dehghan, M. J. & Ashtari, A. Contribution of gravity and Bristow methods for Karez (aqueduct) detection. J. Appl. Geophys. 161, 37–44 (2019).

Yenigun, K. et al. Ancient karez systems in Şanlıurfa, Türkiye: detection, analysis, and sustainability of historical water supply networks. Spat. Inf. Res. 33, 22 (2025).

Baghban Golpasand, M.-R., Do, N. A. & Dias, D. Impact of pre-existent Qanats on ground settlements due to mechanized tunneling. Transport. Geotech. 21, 100262 (2019).

Wang, N. et al. UAV-based remote sensing using visible and multispectral indices for the estimation of vegetation cover in an oasis of a desert. Ecol. Indic. 141, 109155 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Application of remote sensing technology in water quality monitoring: from traditional approaches to artificial intelligence. Water Res. 267, 122546 (2024).

Dindaroğlu, T. et al. Multispectral UAV and satellite images for digital soil modeling with gradient descent boosting and artificial neural network. Earth Sci. Inform. 15, 2239–2263 (2022).

Adamopoulos, E. Learning-based classification of multispectral images for deterioration mapping of historic structures. J. Build. Pathol. Rehab. 6, 41 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. 3D LiDAR and multi-technology collaboration for preservation of built heritage in China: a review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinf. 116, 103156 (2023).

Liu, Z., Zhang, Z. & Hu, W. Multi-level feature fusion and high-fidelity information transfer algorithm for mural inpainting. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 269 (2025).

Biswas, S. et al. Attention-enabled hybrid convolutional neural network for enhancing human–robot collaboration through hand gesture recognition. Comput. Electr. Eng. 123, 110020 (2025).

Zhang, Q. et al. A Mamba-based vision transformer for fine-grained image segmentation of mural figures. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 204 (2025).

Badamasi, H. A review of GIS-based hydrological models for sustainable groundwater management. in Current Directions in Water Scarcity Research (ed. Zakwan, M. et al.) (Elsevier, 2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was jointly funded by Hunan Cultural Tourism Aid Project for Xinjiang "Investigation and Research on Karez Culture", the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42201354), the Xinjiang Tianchi Doctoral Project (CN) (grant no. E335030101) and Chinese Academy of Sciences President's International Fellowship Initiative (PIFI grant nos. 2020VCA0015, 2024PVB0064).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Osman Ilniyaz: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, software, validation, visualization, writing and editing; Yong Zhang: funding, investigation, resources; Long Wang: Conceptualization, investigation, resources; Xiaohe Zhang: funding acquisition, project administration; Alishir Kurban: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, supervision; Anwar Eziz: formal analysis, review and editing; Kahar Ablimit: funding acquisition, project administration; Jean Bourgeois: methodology; Sophie Barbaix: Methodology; Tim Van de Voorde: writing-editing; Jinguo Jiang: investigation, resources; Xianbiao Xiang: validation; Yumiao Wang: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ilniyaz, O., Zhang, Y., Wang, L. et al. A detection-screening framework for karez (ancient underground irrigation system) using deep learning and geospatial analysis. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 429 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01967-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01967-6