Abstract

The unearthed oracle bone fragments containing inscriptions often suffer from vagueness, absence, damage, etc., which significantly obstructs the interpretation of oracle bone inscriptions.While GANs have been applied to the oracle bone inscriptions restoration (OBIR), their performance often degrades in intricate regions due to instability during training (e.g. model collapse).Thus, we propose a new Structure Aware Diffusion Model (SADM) for the OBIR task, which aims to generate more accurate inscriptions. Specifically, we first introduce a progressive Gaussian mask to simulate damage on character rubbings. Subsequently, we propose an Oracle Bone Sampling algorithm (OBS) to progressively recover the oracle bone inscriptions. Then, we develop an adaptive dynamic adjustment mechanism to perceive the hierarchical structure of the reconstructed image. Finally, experiments on several public datasets prove the method’s effectiveness. Our method achieves 41.3% lower FID on OBC306 (64 × 64) compared to the Cold Diffusion model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oracle bone inscriptions, which reflect the social phenomenon in the Shang Dynasty, are the earliest known mature writing system in China, inscribed on turtle shells and animal bones primarily for divination and record keeping. It has a history of more than 3000 years. It is not only an important heritage of Chinese civilization but also a precious material for studying the ancient social culture of the world. Most oracle bones have been buried underground for thousands of years and are easily broken by soil erosion and weathering1. According to statistics, there are currently about 160,000 pieces of oracle bone script, including about 4500 different oracle bone inscriptions. More than 1600 inscriptions have been deciphered (about one-third), and two-thirds are still unsolved mysteries2. The fragmented nature of the oracle bones, which has resulted in incomplete textual data due to physical deterioration, poses significant challenges to scholars in deciphering their inscriptions. Consequently, developing systematic methodologies for the reconstruction of damaged or missing oracle bone inscription fragments has emerged as a critical area of interdisciplinary research that spans paleography, archaeological conservation, and cultural heritage restoration studies.

The current restoration technology of bone inscriptions in the oracle can be divided into traditional reconstruction methods and modern technical methods. The former relies on manual restoration and expert knowledge, which is time-consuming and subject to subjective influences2. Most modern methods are based on simple interpolation3 or local inpainting4, making it difficult to handle complex missing areas and lacking intelligent adaptive inpainting capabilities.

Due to the development of deep learning and large model technology, GANs5 and diffusion models6 have demonstrated powerful modeling capabilities through large-scale data learning, enabling them to effectively inpaint missing regions in images. Conditional GAN7 introduces mask or context information to improve semantic consistency. Subsequent advances, Pix2Pix and CycleGAN have extended the application of inpainting to unpaired data, while high-resolution inpainting methods, such as StyleGAN, have further improved detail preservation8,9,10,11,12. Nevertheless, these methods still face several limitations, including a propensity for model collapse during the training stage, and blurred inpainted details in the inpainted results. In contrast, diffusion models, employing a progressive denoising mechanism, exhibit superior performance in detail reconstruction and stability. However, diffusion models at different stages still have many limitations in image generation tasks. The early DDPM11 and DDIM6 improve the speed through deterministic sampling, but they tend to generate blurring artifacts when attempting to repair fine cracks in oracle bone inscriptions. Latent Diffusion models (such as LDM and Stable Diffusion13) improve the computational efficiency, but the hidden space compression often leads to the loss of high-frequency details and the image texture blur. Although fine control methods such as ControlNet improve the consistency of the structure, there is a risk of overfitting easily leading to a single style14. For the latest high-speed model HART hybrid architecture, due to the difficulty of coordination between autoregressive and diffusion modules, the logical fracture easily occurs in complex scene generation15. However, Cold Diffusion16 trains the reconstruction information reconstruction network by minimizing the respective loss function, thereby demonstrating strong repair capabilities for severely degraded images.

Diverging from general image reconstruction tasks, Oracle Bone Inscription Restoration (OBIR) necessitates the processing of rubbings with distinctive inscriptions (as shown in Fig. 1). These rubbings are generated through a specialized rice paper rubbing technique, which meticulously preserves the morphological intricacies of the original inscriptions while concurrently capturing the historical artifacts, such as cracked textures and natural corrosion, embossed on the oracle bone surface. These inscriptions define two key aspects of oracle bone inscription reconstruction: 1) the OBIR task is highly specific, focusing exclusively on text structure and strokes while ignoring background texture; and 2) the repair logic must accommodate the dual information properties inherent in rubbings (e.g. information recording and artistic expression). However, the existing general image reconstruction techniques, which often rely on noise robustness, exhibit limitations in this specific scenario.

Based on the above observation, we propose a novel Structure-Aware Diffusion Model (SADM) for oracle bone inscription generation. First, we preprocess multiple oracle bone datasets by retaining textual rubbings (images) and applying deterministic transformations (e.g., Gaussian mask). Then, we propose an Oracle Bone Sampling (OBS) algorithm to recover the oracle bone inscriptions in the rubbings progressively. Subsequently, we integrate a composite loss function comprising perceptual loss, absolute error loss, and structural similarity loss (SSIM loss), coupled with an adaptive dynamic adjustment mechanism to adaptively adjust the weights of various loss functions during the training phase. Finally, the evaluation indicators FID, SSIM, and RMSE are used to evaluate the model.

Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

We propose a novel Structure-Aware Diffusion Model (SADM) to generate oracle bone inscriptions, thereby facilitating the restoration of incomplete inscriptions on oracle bone fragments. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first application of diffusion models for the restoration of oracle bone inscriptions.

-

To enhance the training of the restoration network, we propose an Oracle Bone Sampling (OBS) algorithm to progressively recover the oracle bone inscriptions. Moreover, we develop an adaptive dynamic adjustment mechanism to perceive the hierarchical structure of the reconstructed image throughout the different training phases.

-

We processed four publicly available datasets, employing a single dataset for training and reserving the other three for testing. The experimental results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed SADM method.

Methods

Diffusion model and oracle bone inscription restoration

The diffusion model originates from the diffusion process in physics. Its core gradually adds noise to the data, and progressively it reverses to reconstruct the data. This idea was first proposed by Sohl-Dickstein et al. in 2015; it was designed to generate realistic images and data through a reverse diffusion process17. In contrast to traditional methods, diffusion models overcome the inherent limitations of GANs18, including training instability and model collapse. By employing a gradual reverse denoising process, these models more accurately approximate the true data distribution, consistently generating higher-quality and more stable outputs. So far, diffusion models have made significant progress in many fields, especially in multimodal generation tasks19,20,21. Among them, SNIPS19 introduces a random diffusion sampling framework for solving the linear inverse problem under Gaussian noise, which is suitable for low-level visual reconstruction tasks such as image deblurring and super-resolution. HFS-SDE21 introduced the diffusion model into medical imaging, and accelerated the MRI reconstruction process by introducing a two-manifold constraint, effectively improving the sampling speed and reconstruction accuracy; GSD20 focuses on the application of diffusion models in steganalysis generation, it achieves the unity of high-quality image generation and data embedding. At the same time, they have been extended to solve problems such as image reconstruction19,22,23. In image reconstruction tasks, diffusion models demonstrate powerful generation and flexible modeling capabilities, providing technical support for image digital preservation. As a basic diffusion model, DDPM11 generates high-quality images through gradual denoising and is widely used in scenarios such as image restoration and image24. However, its sampling process is lengthy, resulting in low reconstruction efficiency. To improve reconstruction efficiency, DDIM transforms the diffusion process into a deterministic mapping, which reduces the number of sampling steps while maintaining high reconstruction quality. Compared with DDPM, its generation diversity is reduced6. Latent diffusion models (such as LDM and stable diffusion) effectively reduce the computational cost but are suitable for tasks such as image editing and image translation13. Under multimodal conditions, models such as DALL.E 2 and Imagen have achieved fine generation from text to image, supporting image reconstruction and synthesis guided by natural language, but they rely heavily on large-scale, high-quality image-text pairing data, and there are still errors in complex semantic understanding25,26. ControlNet performs well in image structure control and can complete accurate image completion and reconstruction tasks. However, it is easy to produce style convergence problems in diverse expressions due to over-control. Cold Diffusion16 avoids noise disturbances by explicitly modeling the image degradation process as a deterministic mapping. It is particularly suitable for tasks such as image deblurring, denoising, and reconstruction of missing areas. It shows better stability and recovery effects when processing severely degraded images.

Oracle bone inscription restoration refers to the process of repairing oracle bone inscriptions that are blurred, missing, or damaged due to age or improper preservation. Traditional image restoration methods include texture synthesis, edge-driven, and sparse representation methods. Criminisi et al.27 proposed texture synthesis image restoration, which fills in missing parts by matching undamaged areas. Song et al.3 proposed an edge-driven method with edge information to reconstruct stroke contours. Aharo et al.28 proposed a sparse representation to extract local features using dictionary learning, but the limited coverage ability can easily lead to missing strokes or artifact enhancement. However, some studies have tried to integrate multi-feature optimization, mathematical morphology optimization, and fractal geometry interpolation for improvement4. However, accurate stroke reconstruction remains challenging due to three fundamental limitations: the fine-grained semantic segmentation required to distinguish textual strokes from natural cracks and background artifacts, the topological complexity of preserving glyph structures during inpainting, and the inherent scarcity of high-quality training data from extant oracle bone specimens. Recently, deep learning has promoted the rapid development of image generation and restoration technology. GAN29 and its variants, such as Pix2Pix and CycleGAN, are widely used in image restoration and reconstruction. Although they have strong structural modeling capabilities, the generated images are prone to artifacts7,8,12. VAE introduces latent space modeling and supports controllable generation, but the generated images are often blurred. The introduction of VQ-VAE alleviates this problem and lays the foundation for subsequent multimodal models such as DALL.E30. The context encoder uses context features to reconstruct missing areas, but the generated results often have unnatural phenomena at edge transitions31. DeepFill introduces an attention mechanism to enhance the modeling capabilities of complex structures, but it may still generate semantically inconsistent content in the case of large-scale missing areas32. Later, the rise of diffusion models promoted the development of image generation. DDPM11 achieved high-fidelity reconstruction, but the sampling process was slow; DDIM6 improved sampling efficiency but reduced diversity. Multimodal diffusion models based on this, such as DALL.E, Imagen, and DALL.E 2, combined with CLIP encoder, enhanced the semantic consistency of text-to-image generation, but their initial resolution were limited26,33. Stable Diffusion employs latent—space modeling to reduce computational overhead and facilitate high—resolution image generation; however, the inherent compression of latent representations can result in loss of fine detail13. ControlNet enables precise editing and inpainting under structural priors such as edges and poses, yet its reliance on multi—modal guidance makes it sensitive to the distribution of training data and susceptible to overfitting, while offering limited utility when only corrupted text images are available14. RePaint demonstrates strong semantic completion performance in complex missing regions, but its unconditional Gaussian—noise diffusion framework exhibits suboptimal detail consistency and inference efficiency34. Because oracle bone script degradation is predominantly non—Gaussian and structurally localized, these approaches are ill—suited for this domain. To address these challenges, we introduce a structure—aware diffusion model based on deterministic degradation that more accurately simulates real—world damage and enables superior restoration of oracle bone script details.

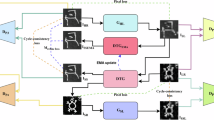

SADM framework

In this work, we propose a SADM for the restoration of oracle bone inscriptions (as shown in Fig. 2). Specifically, in the forward degradation process, given the absence of annotated partial oracle bone rubbings in existing datasets, we introduce a progressive Gaussian mask to simulate authentic damage patterns on complete inscription rubbings. In the reverse denoising process, we adopt the information reconstruction network to gradually restore oracle bone inscriptions. In which we propose an oracle bone image reconstruction sampling algorithm (OBS) to progressively recover the oracle bone inscriptions in the rubbings. Then, we develop an adaptive dynamic adjustment system to perceive the hierarchical structure of the reconstructed image. Finally, the experiments are conducted on multiple preprocessed public datasets to verify the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The complete inscription rubbing is denoted as O0, the random mask generator (M) performs random occlusion, and other previous degradation operations to obtain the degraded image and real noise. At the t − 1 step, Ot−1 = M ⊙ O0, M represents the random binary occlusion mask, and ⊙ represents element-by-element multiplication. Next, the information reconstruction network generates an initial prediction, producing the restored image Ot and estimating the noise \(\hat{\epsilon }\) at the current step t. The model is then trained using the total loss Ltotal. To address the varying importance of different loss functions across training phases, we introduce an adaptive loss balancing mechanism, which incorporates error compensation for gradient stabilization to dynamically adjust the contribution of each loss component during training. Finally, the repaired oracle image \({\hat{{\rm{O}}}}_{0}\) is output.

Deterministic degradation process

Given the original oracle image \({{\rm{O}}}_{0}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\), the degradation operation simulates the situation of local information loss in the image. Specifically, we first construct a two-dimensional Gaussian curve with variance α and discretize it into an n × n array. Then, the Gaussian curve is normalized to obtain a mask Zα with a center close to 0 and an edge close to 1. During the degradation process, the parameter \({\{{\alpha }_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{T}\) (where T is the number of degradation steps) is gradually increased to generate a mask sequence \({Z}_{{\alpha }_{i}}\). The degradation process is expressed as follows:

where x and y represent the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the pixel in the image, the coordinates of the degenerate center point are xc and yc, \({Z}_{{\alpha }_{i}}(x,y)\) represents the value of the mask, which indicates the weight of whether this position is blocked. ⊙ represents element-by-element multiplication. The degraded distribution \(D\left({O}_{0},t\right)\) changes continuously with t, and \(D\left({O}_{0},0\right)={O}_{0}\). In the standard diffusion framework, D is degraded by adding Gaussian noise proportional to t. Due to the sparse structure of oracle bone inscriptions, randomization is introduced when generating the mask to cover the information of different parts. The degree of deterioration varies with t, which improves the model’s robust reconstruction ability for local missing information.

OBS algorithm

In the reconstruction of oracle bone script images, it is necessary to first select the degradation operator D and the training information reconstruction model R, and then combine the two to use the diffusion method11 to reconstruct severely degraded oracle bone script images. For slight degradation("t ≈ 0”), the image can be reconstructed by directly applying R, but under greater degradation, the traditional method is prone to blurring.

In contrast, the standard sampling method (Algorithm 1) adopts an iterative denoising strategy to gradually reduce noise to improve the stability of the reconstruction. However, this method is less effective when dealing with smooth or differentiable degradation.

Algorithm 1

Standard Sampling

Require: A degraded sample xt

for s = t, t − 1, …, 1 do

\({\hat{x}}_{0}\leftarrow R({x}_{s},s)\)

\({x}_{s-1}=D({\hat{x}}_{0},s-1)\)

end for

return x0

Algorithm 2

Oracle Bone Inscription Reconstruction Sampling

Require: A degraded sample Ot

for s = t, t − 1, …, 1 do

\({\hat{O}}_{0}\leftarrow R({O}_{s},s)\)

\({O}_{s-1}=\beta \left({O}_{s}-D({\hat{O}}_{0},s)\right)+\left(1-\beta \right)D({\hat{O}}_{0},s-1)\)

end for

To enhance the reconstruction quality of oracle bone images, we introduce an Oracle Bone Sampling (OBS) algorithm (Algorithm 2). When β = 0, the sampling method is the same as Algorithm 1. When β = 0.5, the sampling method is the same as Cold Diffusion16. If R does not perfectly invert D, we should expect Algorithm 1 to incur errors, and Algorithm 2 becomes immune to errors in R. However, since the recovery quality of the diffusion model varies at different stages of reverse sampling, we need to add a parameter β to adjust the sampling image. In this work, we set β = 0.2, which enables the recovery model to achieve higher-quality results.

Information reconstruction network

In the restoration of oracle bone inscriptions task, the reconstruction operator is denoted by R, which can reverse the degradation operation D, as follows:

The information reconstruction network is represented as Rθ. The deteriorated image Ot at degradation step t is input to Rθ, and the reconstructed image \({\hat{{\rm{O}}}}_{0}\) is output. The residual hole convolution module is introduced in the encoder model to alleviate the gradient disappearance problem. It guarantees that deep-level features are adequately communicated and improves feature expression, hence expanding the receptive field. The entire information reconstruction network is also combined with time embedding coding to adapt to the reconstruction needs of different degradation levels.

In the oracle image reconstruction information task, using simple pixel-level metric (i.e. absolute error loss) cannot effectively capture the fine strokes, complex texture structure, and overall morphology in the oracle bone image. The SSIM loss possesses structure-preserving capabilities and texture-enhancing properties, it can effectively distinguish between cracks and inscription strokes in oracle bone inscriptions while maintaining the spatial relationships among the strokes. The perceptual loss effectively preserves critical features including inscription morphology and stroke trajectory patterns. Therefore, the loss function combines absolute error loss (L1), structural similarity loss (SSIM), and perceptual loss to optimize pixel accuracy.

L1 loss is used to calculate the pixel-level absolute error between the generated image and the real image, it guarantees pixel-level reconstruction accuracy. The overall expression is as shown in Eq. (4), where N represents the total number of pixels in the image, Irecon(i) andIog(i) represents the value of the i-th pixel of the generated image and the real image, respectively.

SSIM loss is introduced to evaluate the visual similarity of images. It comprehensively considers information such as image brightness, contrast, and structure35. It can enhance the spatial consistency of oracle bone script strokes and reduce misalignment or morphological distortion, as shown in Eq. (5), where μx and μy are the average brightness of images x and y respectively. σx and σy are the standard deviations of images x and y respectively. σxy is the covariance of images x and y. C1 and C2 are constants used to stabilize the calculation to avoid the situation where the denominator is zero. Minimizing SSIM loss can enhance the model’s learning of image structure information, making the generated oracle bone script closer to the original image in detail and improving overall recognizability, as shown in Eq. (6).

Perceptual loss is different from L1 and SSIM losses. It uses the pre-trained VGG network to extract high-level features and calculates the difference between the generated image and the real image in the feature space36. It combines global structure, texture, and semantic information to make the generated image closer to the real image in visual perception, avoid stroke distortion, and ensure overall glyph compliance with paleographic standards. The overall expression is as shown in Eq. (7), where Φl( ⋅ ) indicates that the feature map of the lth layer of the pre-trained VGG network selects the intermediate layer of VGG16 for calculation. Nl is the total number of pixels in the feature map of the l − th layer, that is, Nl = Hl × Wl × Cl, Hl and Wl are the height and width of the feature map of the lth layer, respectively. Cl is the number of channels of the convolutional layer. \({\Phi }_{l}{({I}_{{\rm{recon}}})}_{i}\) and \({\Phi }_{l}{({I}_{{\rm{og}}})}_{i}\) respectively represent the value of the i − th feature pixel in the lth layer (feature activation).

The dynamic loss adjustment strategy is shown in Eq. (8). By setting the dynamic hyperparameters λL1, λSSIM, λperceptual, the weights of different loss terms are controlled to ensure that the model can be reasonably optimized at different levels.

In the early stage of training, the image generated by the model is blurry. This is because the model mainly learns the pixel distribution at this time. The L1 loss needs to be enhanced to ensure convergence at the pixel level. In the later stage of training, the model can reconstruct the basic structure well. To increase the image’s structural similarity and high-level semantic consistency, the L1 loss weight should be decreased while the SSIM and perceptual losses should be reinforced. To achieve this process, the training progress p is first normalized to the interval [0,1]. The p-value decreases with increasing training time. The training will be completed sooner as it approaches 1. Scur represents the current number of training steps, and Stotal represents the total number of training steps. On this basis, the weight of each loss is dynamically adjusted according to the training progress p. The specific equation is as follows:

among them, the weight of L1 loss λL1 is progressively decreased during the training process, linearly decreasing from the initial value λL1 to \({\lambda }_{L1}^{decay}p\). It ensures that the pixel-level loss is dominant in the early stage of training to avoid model instability brought on by an excessive gradient. Later on in the training process, structural and perceptual information receive more attention. The weight of SSIM loss λSSIM gradually increases to enhance the ability of structural preservation and make the generated oracle bone script more realistic. Similarly, the perceptual loss λperceptual uses a rising method. Early on, the value of \({\lambda }_{perceptual}^{init}p\) is small. Its weights are progressively increased throughout training, which encourages the model to focus more on high-level semantic information and enhances the overall visual quality of the output.

Results

This experiment was conducted on a workstation equipped with 2 NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs, with a total number of steps of 100,000, a batch size of 64, and an initial learning rate set to 2 × 10−5. To improve training efficiency and accelerate model convergence, we used the Adam optimizer, combined with momentum optimization and an adaptive learning rate strategy, and reduced video memory usage by accumulating gradients every 2 steps. The model uses a dynamic loss system to jointly optimize the image restoration effect to ensure a stable and efficient training process. The experiment fixed the kernel_std parameter value, which governs the standard deviation of Gaussian masking. A higher standard deviation results in increased mask “blur” and consequently expands the area covered by the generated mask. The size of the masked area can be controlled by modifying the image size. We set the image size to 32 × 32, 64 × 64, and 128 × 128 respectively. The smaller the image, the larger the coverage area.

Performance evaluation uses three indicators to comprehensively evaluate the model. The Frechet Inception Distance Score (FID) is used to measure the distribution difference between the generated image and the real image16. The lower the FID value, the closer the generated image is to the real image in terms of visual quality and distribution. The Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) is used to evaluate the similarity between the generated image and the original image in terms of structure, texture, and brightness. The closer the value is to 1, the higher the structural consistency of the image. The root mean square error (RMSE) is used to quantify the pixel-level difference between the generated image and the original image. The lower the value, the higher the image reconstruction accuracy.

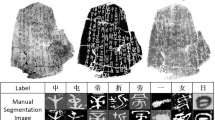

Data preprocessing

In this experiment, we have compiled four public oracle bone image datasets, including the Oracle Bone Script Multimodal dataset (we abbreviate it as OBSM)37, the Oracle Bone Script Detection dataset (we abbreviate it as Testsingle)38, the Oracle Bone Script Rubbing OBC306 dataset39, and the HandWriting Oracle Bone Character (HWOBC) dataset40 (as shown in Fig. 3). Our data processing is mainly divided into two parts: dataset construction and definition and annotation of missing parts.

We employ the OBSM dataset for training and use the other datasets for testing. In building the training dataset, we generate single-inscription images from the OBSM dataset using inscription coordinate information. Each glyph is extracted individually to serve as an independent training sample, enabling the model to focus on inscription reconstruction. To ensure the quality and effectiveness of the training data, we filter out images with large areas of white pixels after generating single inscriptions. As a result, we constructed a dataset consisting of 74,178 images. Specifically, 10% of these samples were randomly designated as a validation set, which was used during training for performance monitoring and hyperparameter tuning. This internal validation split ensures effective model optimization while reserving the remaining datasets exclusively for independent testing.

The four public datasets have their own characteristics in terms of source, style, and task adaptability. The OBSM dataset consists of high-quality rubbing images, with clear glyph structures and supporting coordinate information, and is suitable for generating standardized training samples. The Testsingle dataset comes from high-resolution scanned oracle bone publications, and it is close to the real fragment environment. After manual annotation and cropping, it retains complex interference factors such as real cracks, blur, and damage. It is used to test the model’s reconstruction ability in complex degradation scenarios. The OBC306 dataset is a large-scale public oracle bone script glyph database, covering 306 character categories, with diverse glyphs and rich variants. It is suitable for generalization ability evaluation. The HWOBC dataset is artificial handwritten glyph data, which is handwritten by experts and is used to test the model’s adaptability to style changes.

The test datasets consist of the processed Testsingle, OBC306, and HWOBC datasets, which contain 51,687, 28,706, and 11,643 images, respectively, covering oracle bone inscriptions of different forms and styles and are suitable for evaluating the generalization ability of the model. The test datasets also generate single-word images through coordinate information during preprocessing to ensure that the model can face the reconstruction challenge of single-word images during testing. At the same time, in order to increase the diversity of data and improve the robustness of the model, we perform a variety of enhancement operations on the training data, such as rotation, scaling, and contrast adjustment. Through enhancement operations, the model can better adapt to different image transformations and improve its generalization ability.

For an experimental image size of 128 × 128, the computational load is substantial. Consequently, during testing, we randomly selected 3,200, 2000, and 3900 images from the Testsingle, OBC306, and HWOBC datasets, respectively. Multiple test groups are run simultaneously, and the average results are taken. The primary sample type consists of single oracle bone inscription rubbing images, which display distinct glyphs and detailed textures.To further verify the stability and statistical significance of the proposed method, we report the mean and standard deviation of various evaluation metrics across multiple test groups. In addition, a paired t-test was conducted to assess whether the differences between the improved method and the baseline are statistically significant.

In the oracle image restoration task, we defined the missing parts for each image and used masks to represent these missing areas. Specifically, the missing parts simulate the damage or occlusion phenomenon in the image. In order to perform effective restoration, we use Gaussian masks to annotate the missing parts of the image. The mask is a binary matrix of the same size as the input image, where the area with a value of 1 represents the unoccluded part of the image, and the area with a value of 0 represents the missing or removed part. For each oracle image, we generate task-specific masks, such as random removal or targeted occlusion, and control the missing area size. These masks guide the model to restore the images, ensuring the reconstruction of the missing content based on the visible parts.

Experimental results and analysis

To evaluate the restoration effect of the model, we tested the FID, SSIM, and RMSE indicators on three public datasets. Among them, the lower the FID score, the smaller the distribution difference between the generated image and the real image, and the better the restoration effect; the SSIM value is close to 1, which means that the generated image and the original image have high similarity in structure and texture; the lower the RMSE value, the smaller the pixel-level difference between the generated image and the real image. We employ Cold Diffusion16 as our baseline model, which is based solely on the L1 loss function. In contrast, our proposed SADM model incorporates a dynamic loss system. To ensure a fair comparison of performance metrics, we computed the three evaluation indicators for the degraded images and subsequently evaluated the reconstruction results obtained through standard sampling and our proposed SADM sampling method. The experimental results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

From Table 1 and Table 2, we can see that for the degraded images, the FID, SSIM, and RMSE values obtained by the baseline model and the SADM model are comparable, indicating that the reconstructions are based on similar levels of image degradation. As shown in Table 1, Table 2, the standard reconstruction significantly improves the performance metrics compared to the degraded images, with the OBS reconstruction yielding particularly impressive results. For instance, the FID score for the 32 × 32 image using standard sampling is 43.095, whereas it is reduced to 14.086 after applying the OBS sampling method.

Furthermore, for the same 32 × 32 image, the FID scores are 14.086 for Cold Diffusion with OBS reconstruction and 8.517 for the SADM model. This demonstrates that the proposed SADM model exhibits superior local reconstruction capabilities on all three test datasets compared to the baseline model, particularly in scenarios involving smaller masked simulated defect areas. When the image size is 64 × 64, the SADM model achieves a 36.06%, 41.27%, and 7.2% reduction in FID values compared to the baseline model Cold Diffusion in the OBS Sample results of the Testsingle, OBC306, and HWOBC dataset, respectively. Under the 128 × 128 resolution setting, we conducted five independent tests on the Testsingle, OBC306, and HWOBC datasets. We computed the mean and standard deviation of FID, SSIM, and RMSE, and applied paired t-tests to evaluate the significance of differences between the improved and original methods. As shown in Table 3, the improved method consistently achieved significantly lower FID scores across all datasets (p < 0.0001), and also yielded significant improvements in SSIM and RMSE on the OBC306 and HWOBC datasets (p < 0.05), demonstrating its effectiveness in high-resolution image reconstruction. These results further underscore the outstanding reconstruction accuracy achieved by the SADM model.

Comparison of reconstruction results of models

To further demonstrate the recovery performance of our method on oracle bone inscriptions, we visualized the reconstructed images of various samples. Firstly, we present the reconstruction effects of different models under varying masked areas (as shown in Fig. 4). Subsequently, we provide the test result images for different datasets (as shown in Fig. 5). Finally, we display the reconstruction effect images of the same oracle bone inscription under different mask conditions (as shown in Fig. 6).

The restoration effects of three different image specifications on different inscriptions (eg. (a) and (b). GT represents the ground truth, DI represents the degraded and incomplete oracle bone script, and RI represents the restored oracle bone inscriptions. The restoration effect of the oracle bone inscription image with a size of 32 × 32 (top line), 64 × 64 (second line), and 128 × 128 (bottom line).

From Fig. 4, it can be observed that as the masked area decreases, the model’s inpainting accuracy significantly improves. When the masked area is large, although the inpainting effect is weaker, the model still possesses reconstruction capability and demonstrates a certain level of inpainting accuracy. This observation is consistent with the conclusions drawn from the aforementioned quantitative analysis.

From Fig. 5, the model can repair different datasets. Its accuracy is higher on the topology dataset, likely because it was only trained on rubbings. This significantly implies that even without handwritten training data, the model can still effectively restore the handwritten fonts of HWOBC.

From Fig. 6, it can be observed that the proposed algorithm can successfully reconstruct oracle bone inscriptions regardless of the size of the masked areas. Specifically, with a 64 × 64 pixel mask, corresponding to moderate masking, the reconstructed inscriptions appear smoother. This suggests that the algorithm achieves the best restoration effect for oracle bone script inscriptions that are approximately half damaged.

Ablation study

In this section, we first conduct ablation experiments on different loss functions and dynamic loss strategies, followed by an analysis of parameter β. For the experiments, oracle bone inscription rubbings with a resolution of 64 × 64 are selected as test samples to evaluate the impact of the aforementioned factors on the restoration effect.

For the ablation experiments on different loss functions, we first gradually introduce various loss functions, compare their performance in oracle bone inscription image restoration, and analyze how different loss functions affect the image restoration effect, especially in terms of pixel-level accuracy and the rationality of inscription morphology.

In the ablation experiment, we first used L1 loss and L1+0.01 perceptual loss for training respectively, and evaluated their performance on multiple datasets. From the experimental results, the introduction of perceptual loss will affect the overall oracle bone inscription image reconstruction quality. In the Testsingle and OBC306 datasets, the FID, RMSE, and SSIM of L1 combined with perceptual loss did not show significant improvements. However, in the HWOBC dataset, the FID of the standard sampling reconstruction method was reduced by 1.81, indicating that perceptual loss may help the reconstruction of high-level features on this dataset. From these three indicators, the introduction of perceptual loss has a limited impact on the overall deblurring effect. The reason for the analysis may be that the current perceptual loss weight is low (0.01), which failed to affect the FID result during the optimization process. To further improve model performance, we can increase the weight of the perceptual loss and combine it with SSIM loss or other loss functions. This will enhance the model’s ability to reconstruct structural information.

Then, comparing L1 + perceptual loss with L1 + perceptual loss + SSIM loss, it was found that the addition of SSIM loss improves the overall quality of oracle bone inscription reconstruction. This improvement was evident in the reduced FID, improved SSIM, and reduced RMSE. Specifically, in the Testsingle dataset, the FID of L1 + 0.01 perceptual loss + 0.2 SSIM loss decreased by 29.2%(from 5.47 to 3.87). In the OBC306 dataset, it decreased by 39.6% (from 4.88 to 2.95), demonstrating the positive impact of SSIM loss on the perceptual quality of the reconstructed images. Across all datasets, the SSIM index improved, indicating that SSIM loss contributes to enhancing the structural similarity of the images and making the reconstructed oracle bone inscriptions more akin to the original images. In the HWOBC dataset, while the FID decreased by 11.7% (from 33.41 to 29.49), despite a slight increase in RMSE, potentially linked to the handwritten nature of the dataset’s inscriptions, the addition of SSIM loss significantly improved the FID score. This confirms that SSIM loss plays a beneficial role in preserving structural information within the images.

The dynamic loss adjustment strategy is introduced to further improve the reconstruction ability of the model (as shown in Fig. 7 and Table 6). During the training process, the weight of each loss function is adjusted according to the training progress of the experiment, so that the model can adaptively balance the influence of different losses at different stages. This mechanism is introduced to balance the impact of specific loss functions during training, preventing instability or overfitting and improving reconstruction accuracy for oracle bone inscription images.

The experimental results in Tables 4, 5 show that the dynamic loss adjustment strategy significantly improves the image reconstruction quality on the Testsingle and OBC306 datasets, reducing the FID of the Testsingle and OBC306 datasets by 14.26% and 13.12%, respectively. It indicates that the perceptual difference between the generated image and the original image is further reduced. As training weight increases, both perceptual loss and SSIM loss contribute to a clearer restored image. However, this also results in a slight increase in RMSE. Despite this, the overall RMSE level remains low, suggesting that this strategy enhances overall visual quality without significantly impacting local pixel errors. In the HWOB dataset, the FID and RMSE of the strategy increased slightly, which may be due to the fact that the images in this dataset are handwritten datasets and have characteristic differences from the pre-trained rubbing datasets, resulting in a certain deviation in the dynamic loss adjustment when weighing detail retention and overall perceptual quality. In addition, from the perspective of FID improvement, the FID of sample reconstruction of the Testsingle and OBC306 datasets increased by 65.87 and 70.67, respectively, which is better than the fixed loss weight scheme. Overall, the dynamic loss adjustment strategy performs better than the fixed loss scheme in the Testsingle and OBC306 datasets, significantly improving the quality of the reconstructed images, but its adaptability in the HWOBC dataset still needs to be optimized to better balance local details and overall visual quality.

Figure 7 shows the changes in the weights of L1 loss, SSIM loss, perceptual loss, and the total loss function during training under different oracle image specifications. As the training progresses, the weights of each item gradually change and the total loss gradually stabilizes, indicating that the performance of the model gradually improves during the optimization process. The convergence of the loss function indicates that the model is gradually becoming more effective in the oracle image restoration task.

In order to explore the influence of parameter β on the ODS sampling effect, we designed the changes of FID, SSIM, and RMSE indicators when taking different β parameter values, and measured the β value when the optimal sampling was performed. The experimental results are shown in Table 7, and the visualization results are shown in Fig. 8. When β is 0.5, the sampling method is the same as Cold Diffusion16 In the context of oracle bone image reconstruction, the range of β between 0.2 and 0.3 yields the most favorable results. This is evidenced by lower FID and RMSE values, along with a higher SSIM value, which collectively suggest increased similarity between generated and real images, reduced prediction errors, and enhanced structural similarity, thereby indicating its suitability for our experimental task.

Evaluating the model’s generalization to handwritten style

To assess the model’s zero-shot generalization to handwritten styles, we conducted experiments at 64 × 64 resolution using the OBSM dataset as the training set and HWOBC as the test set. Three training settings were compared: OB-RubbingNet (rubbing data only), OB-HandNet (handwritten data only), and OB-FusionNet (a combination of both). As shown in Table 8, OB-HandNet achieved the best performance on the target domain (FID = 7.76, RMSE = 0.087, SSIM = 0.932). OB-FusionNet significantly improved generalization over OB-RubbingNet (FID: 27.703 → 9.389; RMSE: 0.111 → 0.087), and alleviated RMSE spikes under dynamic loss. These results highlight the model’s adaptability to style variations. Although augmenting the training set with handwritten characters improved results on the HWOBC dataset, it degraded performance on rubbing-related tasks. Since oracle bone inscription restoration primarily targets inscriptions on rubbings (not handwritten forms), the original SADM (i.e., OB-RubbingNet) model delivers optimal restoration performance for rubbings.

The restoration examples from real rubbings

Moreover, we have applied our method to restore incomplete oracle bone inscriptions sourced from genuine rubbing fragments. Figures 9 and 10 illustrate representative restoration results for samples exhibiting less than 20% damage and those with 45–60% damage, respectively. A critical preprocessing step involves embedding the damaged oracle bone fragments into a black background (P-BI) to spatially extend the pixel regions, addressing the inherent limitation of diffusion models, which do not natively perform pixel expansion during the denoising process. Following this embedding, deterministic degradation (DI) was applied, and restoration was guided using the Oracle Bone Sampling (OBS) strategy integrated into our model to obtain the final restored images (RI). As shown in Fig. 9, the reconstructed results demonstrate the model’s high fidelity in restoring lightly damaged inscriptions. In Fig. 9, the first five cases correspond to samples with severe structural loss, and the resulting RI outputs highlight the model’s capacity to reconstruct significant missing regions. The lower four cases in Fig. 10 further validate the model’s robustness against substantial noise, showcasing its ability to recover the structural integrity of oracle bone characters under adverse visual conditions.

The failed restoration examples of some incomplete oracle bones

Although the proposed method shows excellent reconstruction performance on most samples, there are still cases of repair failure on some special samples. A typical example is shown in Fig. 11. Specifically, when the image is severely occluded, it is difficult for the model to accurately infer the structural information of the missing area, such as in the third line; when the noise interference in the image is strong, it will significantly affect the model’s understanding of the overall structure of the oracle bone inscriptions.

While the SADM method cannot achieve accurate restoration, it can perform local denoising, as seen in the fourth and fifth lines. However, as demonstrated by the first line, some samples feature complex fracture structures with severe information missing, leading to generated results with issues like missing strokes, structural misalignment, or overall blurriness. Despite these structural integrity deviations, the reconstruction results still offer valuable reference information for experts and scholars working with oracle bone inscriptions. These failures may stem from the limited representation of complex structural samples in the training data, hindering the model’s generalization under extreme conditions.

Discussion

In this work, we propose a structure-aware diffusion model to reconstruct oracle bone inscriptions, addressing challenges such as vagueness, fragmentation, and missing content in unearthed fragments. This is the first application of diffusion models for the restoration of oracle bone inscriptions. The FID, SSIM, and RMSE evaluations all show that the proposed method can effectively restore the details of the oracle bone inscriptions. At the same time, this study also recognizes that there are some directions for the current model to be optimized: in terms of style transfer, since the training mainly relies on the images of oracle bone inscriptions, the adaptability of the model to oracle bone inscriptions with multiple writing variants and styles needs to be improved; in terms of context information utilization, The current single-character damage repair is our initial exploration of oracle fragment restoration. In future work, we will continue to conduct more in-depth research based on the multi-character sequences. In summary, the structure-aware diffusion model proposed in this study has achieved remarkable results in the reconstruction of single-word details of oracle bone inscriptions, providing a new method for the field.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code will be available as open source.

References

Liu, J. et al. Obi-cmf: Self-supervised learning with contrastive masked frequency modeling for oracle bone inscription recognition. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 55 (2025).

Guan, H. et al. Deciphering oracle bone language with diffusion models. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 15,554–15,567 (2024).

Song, C., Qiao, M. & Hong, Y. Edge gradient covariance-guided oracle bone character repair algorithm (2022). In Chinese.

Xu, Z. et al. A review of image inpainting methods based on deep learning. Appl. Sci. 13, 11189 (2023).

Sun, Z.-L. et al. Text-to-chinese-painting method based on multi-domain vqgan. Ruan Jian Xue Bao/J. Softw. 34, 2116–2133 (2023). In Chinese.

Song, J., Meng, C. & Ermon, S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. In 9th International Conference on Learning Representations,ICLR 2021,Virtual Event,Austria,May 3-7,2021 (2021).

Isola, P., Zhu, J.-Y., Zhou, T. & Efros, A. A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1125–1134 (2017).

Zhu, J.-Y., Park, T., Isola, P. & Efros, A. A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2242–2251 (IEEE, 2017).

Karras, T., Aila, T., Laine, S. & Lehtinen, J. Progressive growing of gans for improved quality, stability, and variation. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2018).

Karras, T., Laine, S. & Aila, T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 4396–4405 (IEEE, 2019).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 6840–6851 (2020).

Xu, Z., Zhang, C. & Wu, Y. Digital inpainting of mural images based on dc-cyclegan. Herit. Sci. 11, 169 (2023).

Rombach, R., Blattmann, A., Lorenz, D., Esser, P. & Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 10,674–10,685 (2022).

Zhang, L., Rao, A. & Agrawala, M. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 3813–3824 (IEEE Computer Society, 2023).

Tang, H. et al. Hart: Efficient visual generation with hybrid autoregressive transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.10812 (2024).

Bansal, A. et al. Cold diffusion: Inverting arbitrary image transforms without noise. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 41,259–41,282 (2023).

Sohl-Dickstein, J., Weiss, E., Maheswaranathan, N. & Ganguli, S. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. In International conference on machine learning, 2256–2265 (pmlr, 2015).

He, C. et al. Diffusion models in low-level vision: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1–20 (2025).

Kawar, B., Vaksman, G. & Elad, M. Snips: solving noisy inverse problems stochastically. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 21,757–21,769 (2021).

Zhou, Q., Wei, P., Qian, Z., Zhang, X. & Li, S. Improved generative steganography based on diffusion model. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology (2025).

Qiao, L. et al. Fast sampling of diffusion models for accelerated mri using dual manifold constraints. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video TechnologyArticle in Press, 1–1 (2025).

Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877–1901 (2020).

Brock, A., Donahue, J. & Simonyan, K. Large scale gan training for high fidelity natural image synthesis. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2019). Published: 21 Dec 2018, Last Modified: 13 Apr 2025.

Hu, J., Yu, Y. & Zhou, Q. Guidepaint: lossless image-guided diffusion model for ancient mural image restoration. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 118 (2025).

Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C. & Chen, M. Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125 1, 3 (2022).

Saharia, C. et al. Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 36,479–36,494 (2022).

Criminisi, A., Pérez, P. & Toyama, K. Region filling and object removal by exemplar-based image inpainting. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 1200–1212 (2004).

Aharon, M., Elad, M. & Bruckstein, A. K-svd: An algorithm for designing overcomplete dictionaries for sparse representation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 54, 4311–4322 (2006).

Goodfellow, I. J. et al. Generative adversarial nets. In Ghahramani, Z., Welling, M., Cortes, C., Lawrence, N. & Weinberger, K. Q. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 27, 2672–2680 (Curran Associates, Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2014).

van den Oord, A., Vinyals, O. & Kavukcuoglu, K. Neural discrete representation learning. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 6309–6318 (2017).

Pathak, D., Krahenbuhl, P., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Efros, A. A. Context encoders: Feature learning by inpainting. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2536–2544 (2016).

Yu, J. et al. Generative image inpainting with contextual attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 5505–5514 (2018).

Ramesh, A. et al. Zero-shot text-to-image generation. In International conference on machine learning, 8821–8831 (Pmlr, 2021).

Lugmayr, A. et al. Repaint: Inpainting using denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 11,451–11,461 (2022).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Johnson, J., Alahi, A. & Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11-14, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 14, 694–711 (Springer, 2016).

Center, D. O. B. C. Oracle bone script multimodal dataset. In World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC) (Shanghai, China, 2024). In Chinese.

Guo, M. & Hu, H.Collection of Oracle Bone Inscriptions, vol. 21 (Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing, 1982). In Chinese.

Huang, S., Wang, H., Liu, Y., Shi, X. & Jin, L. Obc306: A large-scale oracle bone character recognition dataset. In 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), 681–688 (IEEE, 2019).

Li, B. et al. Hwobc-a handwriting oracle bone character recognition database. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1651, 012050 (IOP Publishing, 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China 62406105, 62072160, and 62473033, in part by the National Social Science Foundation of China 20&ZD305, in part by the Research Project of the National Language ZDA145-22, and Technology Research Project of Henan Province 242102210055, 252102321139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yue Zhang and Aoli Han wrote the main manuscript text and performed the main experiments. Shibing Wang and Jie Liu provided the datasets. Xueshan Li and Dong Liu provided the project platform and project guidance. Yigang Cen provided methodological ideas and technical guidance. All the above authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Han, A., Wang, S. et al. Generating oracle bone inscriptions based on the structure aware diffusion model. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 461 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02000-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02000-6

This article is cited by

-

OraGAN: a deep learning based model for restoring Oracle Bone Script Images

npj Heritage Science (2025)