Abstract

Three undated, unidentified and decontextualised Qurʾānic fragments on parchment from the collection of the University of Münster were analysed applying a cross-disciplinary approach, in an attempt to identify their writing materials, re-establish their integrity and original historical context. The results from palaeographic, philological and historical analysis of the fragments enabled us to reconstruct a possible stratigraphy for the objects and revealed the presence of later scribal interventions in the form of re-inking and one correction. Material analysis, particularly XRF spectroscopy, was then used to identify the inks employed for writing. Specifically, Cu/Fe ratios were used as fingerprints to distinguish variants of iron-gall ink, and revealed: a primary ink, for writing the initial text and a secondary ink, which could be attributed to later scribal interventions. The combined results allowed us to place the fragments in their original historical context, facilitating their attribution to the same Umayyad Qurʾān.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of Qurʾānic manuscripts from the early centuries of Islam is largely contingent upon the identification of individual fragments scattered across various collections throughout the world. Scholars working on these manuscripts usually rely on clues offered by different disciplines like palaeography, codicology and philology in order to bring together the membra disjecta of an original historical artefact1,2,3. This identification primarily depends on the material features of the fragments, which can be utilised to understand their original structure as quires and codices, thereby reconstructing the socio-historical context of ‘orphaned objects’— according to terminology used to describe archaeological findings that are sold as fragmentary objects and are missing information about their context—and re-establishing their integrity4. This can be challenging, however, if the fragments are few and isolated pieces, particularly in the absence of specific features facilitating their identification. To establish the relationship between the individual fragments and to reconstruct the historical context of the original, missing artefact, it can be beneficial to adopt a cross-disciplinary approach that adds material analysis to the workflow.

A vast majority of the extant early Qurʾānic fragments were written on parchment, using iron-gall inks5,6. While the use of non-destructive techniques for identification and classification of iron-gall inks is well reported in other manuscript cultures, its application to studying objects from early Islamic centuries is a venue for further research still to be fully explored7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Here, the fingerprint model of XRF analysis, which groups together inks of similar elemental compositions, can be combined with palaeographic and philological studies to aid in the identification of groups or clusters of fragments that likely came from the same manuscript. Furthermore, additional material analysis can help in addressing questions related to the provenance and life cycle of the manuscript.

This work is an initial attempt at utilising material analysis to understand and study the link between three undated, unidentified and decontextualised Qurʾānic fragments and place them in their cultural and historical context. The analytical protocol developed by the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC, University of Hamburg) and Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und -prüfung (BAM) for the non-destructive characterisation of inks was adopted for the investigation15,16. The main research questions shaping our analysis in this article have been the identification of the writing materials of the three fragments, the restoration of their integrity, and the reconstruction of their historical context through the establishment of the possible stratigraphy of the object. Our aim is to demonstrate the potential of material analysis to serve as an interdisciplinary bridge, connecting lost fragments and paving the way towards their reassembly.

Methods

Historical and Visual analysis

Provenance history

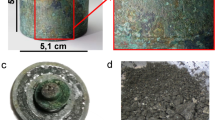

The three isolated Qurʾānic fragments analysed here are orphaned objects, part of the collection of the Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies at the University of Münster and are known under the shelf mark Hs. 15 (a, b and c) (Fig. 1). The fragments, acquired in the 1970s by the German diplomat Dr. Norbert Heinrich Holl from the antiquarian book dealer L’Orientaliste in Cairo, were donated in stages to the Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies, starting from 2018. It is our understanding that Dr. Holl acted in good faith when he bought and exported the fragments, although the export documentation is not complete nowadays, generating questions about the acquisition process in light of the Egyptian ratification of the UNESCO 1970 convention (1973) and the Egyptian law no.215 regulating antiquities in private hands (1952). Both previous and present owners cooperated during our investigation concerning the provenance of the fragments by sharing pictures and documentary evidence. The University did not conceal any pieces of information regarding the provenance of the fragments, which are published on the website of the Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies (https://www.uni-muenster.de/ArabistikIslam/sammlung/aegypten/koranblaetter_kufi.html). Additional information concerning the fragments’ provenance will be the subject of a separate publication, focusing on the history of the manuscript to which they once belonged.

Description of the fragments and conservation history

The Münster fragments are the remains of three Qurʾānic leaves on parchment and measure, respectively, height × width, 13 × 34 cm, 14 × 37.5 cm and 23 × 38.5 cm, with a text area of 11 × 30 cm, 10 × 31 cm and 17 × 31 cm. The original leaves, however, were bigger and in vertical format based on the layout and missing text, measuring approximately 45 × 38.5 cm, with a text area of about 36 × 30–31 cm, likely structured into eighteen lines. The three fragments sport non-consecutive sections of the Qurʾānic text, namely Q.5:8-10 (flesh side) and Q.5:12-13 (hair side) in Hs. 15a, Q.10:98-100 (flesh side) and Q.10:104-106 (hair side) in Hs. 15b and Q.12:81-84 (hair side) and Q.12:88-90 (flesh side) in Hs. 15c. Hs. 15b shows further traces of fragmentation of the parchment material. Two tiny pieces of parchment, once belonging to the missing ll.6-7 (with Q.10:106:8-9 and Q.10:106:13), have been used to fill the missing material at ll. 4-5. This precise restoration was intended to reinstate the leaf’s integrity, suggesting that the fragile parchment was likely falling into pieces.

After their donation to the University, the three fragments were removed from their original glass-frame encasing. Two of the three fragments (Hs. 15a and 15b) underwent conservation treatments once in the custody of the Institute and were consolidated using conservation-grade tissue paper: Hs. 15a, which showed significant signs of ink corrosion, was completely laminated with tissue paper while only the margins of Hs. 15b, which appeared to be in a better condition, were strengthened with the same tissue paper. It is possible that these two fragments also underwent additional wet chemical treatments, particularly Hs. 15a. Unfortunately, further information about the restoration history and type of conservation treatment could not be retrieved. Hs. 15c was donated separately and was displayed in a glass frame for several years; it was removed out of its original encasing just a few months prior to our investigation and was not subjected to any conservation treatment during this time. We are not in possession of any additional information concerning repairs, treatments and conservation condition of the fragments while they were in the hands of Dr. Holl.

Comparison with other Umayyad Qurʾāns

The script style and layout of the leaves are characteristic of Umayyad Qurʾānic codices, copies of the sacred text produced under the Umayyad dynasty from 644 to 750 CE17,18,19. Other examples of Umayyad Qurʾāns are the manuscript Dublin, CBL Is 1404, produced during the first decades of the eighth century, probably in some official context, and kept in the Egyptian delta until the beginning of the twentieth century and the manuscript Sanaa, DaM 20-33.1, likely produced in the last decades of the Umayyad rule17. Made by professional copyists to be used in mosques, these copies of monumental size were designed to be set on large reading stands or cradles18. For example, in its current disbound state and its 201 leaves of about 47 × 38 cm, CBL Is 1404 weighs approximately 7 kg20,21. When compared with other Umayyad Qurʾāns, the Münster fragments are peculiar, as they are characterised by the absence of coloured round dots marking vowels, while featuring only tiny oblique strokes in brown ink used as consonantal diacritics to distinguish some homograph letters. Additionally, four to five tiny oblique strokes in brown ink arranged in a column are used to mark the end of a single verse.

Reinking and correction

While the ink appears faded on the flesh side of all the Münster fragments, two specific features are clearly visible on Hs. 15a and 15b, respectively. The script on the recto of Hs. 15a (flesh side) has been reinked, and the degraded areas show the piercing and loss of writing support corresponding to the reinked letters (see Fig. 2). L. 4 of Hs. 15b verso has been corrected: there are signs of erasure in the expression li-l‑dīni ḥanīfan wa‑lā takūnanna ‘[Set thy face] to the religion, a man of pure faith, and be thou not [of the idolaters]’ (Q.10:105:4-7)22. Erasure of letters (e.g. the descender of the final letter nūn below the initial letter ḥāʾ and what seems to be a diacritical stroke above the letter dāl but is a larger letter dāl in the first layer of the script), the absence of the regular distance between letters and letter-blocks observed in the rest of the fragments, and a more condensed script suggest that the first layer of the text read li-l‑dīni wa‑lā takūnanna, while the missing word ḥanīfan was added later (see Fig. 3). Hs. 15c shows some traces of interventions, like the punctual retracing of some letters or strokes; therefore, localised reinking cannot be excluded.

Top: Reinking of the script on Hs. 15a recto (l. 3): [ā]manū wa‑ʿami[lū], ‘[those that] believe, and do deeds’ (Q.5:9:4-5). Bottom: Loss of material on Hs. 15a verso (l. 3: fa‑qad ḍalla, ‘surely he has gone astray [from the right way]’ in Q.5:12:42-43) exhibiting holes with the mirrored shape of the reinked letters on the recto.

The stratigraphy of the object with erasures and corrections, faded ink and reinking is a crucial element in reconstructing the history of the artefact and in determining the socio-historical context in which it was produced and used. Establishing a relative chronology of the correction layers is of particular importance, since the missing word ḥanīf is one of the central Qurʾānic concepts with relevant cultic dimensions together with dīn and islām23. As the brown ink of the correction is seemingly identical to the brown ink used in the first production process, it was impossible to understand whether the word was immediately added during the first production process by the same scribe—which seems more plausible due to the importance of the missing word—or it was amended after a certain period of time.

Digital microscopy

The first step of the analytical protocol consists of an initial screening of the inks using the Dino-lite USB microscope AD413T-I2V within the magnification range 10x-200x. The microscope was mounted on an external white light source, and the images of the ink strokes were acquired under built-in white (visible), ultraviolet (395 nm) and near infrared (940 nm) illuminations.

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF)

Point analysis was carried out using Bruker/XG Lab Elio with a Rh X-ray tube, with a 25 mm2 large-area silicon drift detector (SDD) and an interaction spot of 1 mm. The measurements were conducted at 40 kV voltage, 80 μA current, with a measurement time of 120 s per spot. For this, the fragments were placed on a Melinex tile laid on top of foam support (around 3–4 cm thick), with a cavity centred under the area of measurement, creating an XRF-blank substrate. The spectra obtained were then deconvoluted and fitted using M6 Jet Stream software (ver 1.6.893.0), and the net intensity counts for each element were used for further processing. For each point of interest on the ink, a corresponding point on the parchment was measured to facilitate comparison. The different types of inks used were classified on the basis of the fingerprint model24,25,26,27,28. The intensity counts for elements present in the ink were calculated by subtracting the intensity contribution of the writing substrate (parchment) from that of the ink. The resulting net intensity values were then used to calculate the Cu/Fe ratio used to differentiate the inks.

Spatial maps of specific regions of interest (ROIs) were acquired using Bruker M6 Jetstream with a Rh X-ray tube, with a 50 mm2 Xflash SDD detector, and an adjustable measuring spot ranging from 50 to 650 µm. The measurements were conducted at 50 kV voltage and 600 μA current, with a spot size of 50 µm, an acquisition time of 15–20 ms per pixel and a pixel (step) size of 50–100 μm. The fragments were placed on top of a Melinex tile, which was then positioned on a table-like stage, between two movable acrylic plates, ‘suspending’ the fragments in open space. The spectra were deconvoluted using the M6 Jet Stream software and the data are presented as heat maps showing relative intensities of elements.

µ-XRF mapping shows the visualisation of elemental composition of the material in the form of spatial distribution maps. This method also allows us to assess the homogeneity of the writing materials and acts as a reliable way to identify possible different scribal activities29. In this case, the total area that could be considered for a single mapping acquisition was also impacted by the natural movement of the skin, as well as wrinkles and an overall wavy surface. These surface features made it difficult to maintain a constant distance from the instrument optics for mapping acquisitions of larger ROI, thus we opted to acquire smaller maps and point measurements. Point analysis provides a rapid way to characterise inks compared to mapping and is particularly useful when the investigations are performed with time and spatial constraints. When working with inhomogeneous materials, relying only on point analysis can sometimes generate ambiguous data points that, in extreme cases, can result in incorrect conclusions. Additionally, since XRF is a penetrative technique, spots for point analysis should be chosen carefully to avoid any interference with text from the other side of the studied fragment. Therefore, in this work, we utilised a combination of both approaches to provide a more comprehensive picture.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

Measurements were performed using a Bruker Alpha II FTIR spectrometer in external reflection mode (ER-FTIR), with a measuring spot size of ~4 mm. The spectra were acquired in the range 4000–400 cm−1 with a total of 16 scans per measurement, with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. The Kramers-Kronig (KK) transformation was applied to the resulting reflectance spectrum using the instrument’s software (OPUS) to facilitate the assignation of peak positions according to available literature30,31,32. The spectra were finally evaluated and plotted using Origin Pro 2025.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra for the inks were acquired using a Renishaw inVia Raman spectrometer. The infrared laser (300 mW, 785 nm) was used for the acquisition of the spectra, recorded under a microscope with a 100× long distance objective, at laser power 2% (~2.2 mW), with an accumulation of 50 scans of 1 s each. The spectra obtained were subjected to baseline correction and further evaluated using Origin Pro 2025.

Results

Inks

The preliminary screening with digital microscopy suggested the use of iron-gall ink types throughout the fragments, since the images acquired under infrared light show a decrease in opacity of the strokes33.

The elemental composition of the inks was then determined using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, using both point and mapping modes. The application of these techniques on specific ROIs was guided by the research questions formulated during the palaeographic, philological and historical analysis of the fragments using a cross-disciplinary approach. Special focus was placed on identifying the ink used to carry out the reinking in Hs. 15a and the correction inserted in Hs. 15b, while for Hs. 15c, ROIs were chosen on sections showing potential scribal interventions.

Starting with the ink used for the text without later interventions, XRF analysis indicates the presence of iron (Fe; Kα- 6.41, Kβ-7.05) as the main element in the ink of all three fragments, confirming the use of iron-gall ink (Fig. 4a). Additionally, variable amounts of copper (Cu; Kα- 8.05, Kβ-8.9) were found to be present in the ink, followed by lower amounts of manganese (Mn; Kα-5.90) and zinc (Zn; Kα-8.63), allowing us to classify this ink as a vitriolic iron-gall ink. Besides these elements, contributions from potassium (K; Kα-3.31) could also be seen in the ink and can be attributed to the presence of tannins. The distribution of the minor elements in all the analysed spots is presented in Fig. 4b, displayed as net intensity. Among the vitriolic elements, the amount of manganese and zinc present in the ink was significantly lower than that of copper, probably present as minor impurities, distributed inhomogeneously. The resulting Mn/Fe and Zn/Fe ratio consequently engendered higher margins of error due to the low values. Therefore, to avoid potential mistakes in the classification, we decided to primarily focus on copper and iron.

a XRF spectra of the main ink used for the writing of the three fragments and the corresponding region on parchment (dotted lines). b Distribution of elements (other than iron) present in the inks (primary and secondary) across the three fragments. Notice the low net intensity values for Manganese and Zinc.

The elemental distribution of iron and copper in the ink is presented as heat maps (Figs. 5–8) with warmer colours corresponding to a higher elemental density. The correlation of these two elements with the inked areas is clear. The colour distribution of iron and copper shows localised dense concentrations of the elements in the same areas, likely corresponding to the points where the scribe refilled the stylus with ink, as these variations occur within the same word or letter, often along the edge of the strokes29. The overall intensity of the heatmap is also influenced by the state of preservation of the three fragments, with flaking and fading ink areas resulting in a ‘cooler’ representation of iron and copper on the heatmap (example Fig. 6, white box). Additionally, the difference in the absorption dynamics of the flesh and the hair side also appeared to affect the final results: heat maps for the hair side of the parchment (Hs. 15c recto, Fig. 5) show better contrast and correlation to the text compared to the flesh side (Hs. 15c verso, Fig. 6), where the heat maps include significant contributions from the other side.

While copper usually appears to follow the same distribution of iron, its absence can be noted clearly in the sections of text corresponding to the correction on Hs. 15b verso and, less clearly, to the reinked letters in Hs. 15a recto.

For the fragment Hs. 15a, the phenomenon of ink corrosion can be ascribed to the text written on just one side of the parchment (recto, flesh side; see Fig. 2), suggesting the use of a different, corrosive ink for the reinking. XRF scans, displayed as heat maps in Fig. 7, show the presence of iron in this ink, while contributions from copper, although faint, can be attributed to the text written on the verso, suggesting the use of an iron-gall ink with no significant impurities or even of a non-vitriolic iron-gall ink for the reinking. Non-vitriolic iron-gall inks were known to Arabic scribes, as recipes mentioning inks made from iron filings, nails, or solid pieces of iron are recorded at least from the 13th c. CE. However, the typology was used in Egypt before, as it was detected in Coptic manuscripts already from the 7th c. CE34,35. While the presence of sulphur can be associated only with vitriolic inks, this element is difficult to evaluate due to the detection limits of the used equipment; therefore, to avoid ambiguous definitions, we are referring to this ink as ‘iron-gall with no significant impurities’. The same elemental profile can be observed for the text corresponding to the correction on Hs. 15b verso: while the signals from iron remain relatively strong in the heat maps for both inks, the copper is absent from the ink used for the correction (Fig. 8).

For the fragment Hs. 15c, the lack of prominent visual signs suggesting correction or reinking, along with clear signals from copper (although low in intensity) in the ROI, makes it difficult to determine whether the fragment was indeed punctually reinked with the same iron-gall ink with no significant impurities on a less damaged iron-gall ink with copper, with the map thus showing the contribution from both ink layers. To summarise, the XRF results allow us to ascertain the presence of at least two types of ink: a vitriolic iron-gall ink, with copper as the primary impurity, that will henceforth be referred to as ‘primary’ ink, and an iron-gall ink with no significant impurities, termed ‘secondary’ ink.

In order to assess the similarities between the primary and secondary inks from the three individual fragments, we decided to utilise the fingerprint model for the characterisation of inks. Suitable spots for measurement were identified to reflect the least amount of interference from the other side, while also aligning with the observations from the philological, codicological and historical analysis. Although the contribution of potassium from tannins was found to be common for both primary and secondary inks, its ratio did not facilitate the classification of the inks into the two groups. Therefore, we focused on the ratio of copper to iron.

The results from the measurements are shown as Cu/Fe ratios in Fig. 9, plotted as a box and whisker plot, represented as primary and secondary ink.

For secondary inks, the data points corresponding to reinking (Hs. 15a) and correction (Hs. 15b) appear to overlap perfectly with each other, showing a low Cu/Fe ratio, confirming that the secondary inks used for reinking and corrections are the same. Data points corresponding to regions showing potential scribal interventions from fragment Hs. 15c were also found to have a comparable Cu/Fe ratio. Within this group, however, a separation can be seen in the Cu/Fe ratio of the three fragments: Hs. 15a collectively appears to show a slightly higher Cu/Fe value than Hs. 15b, while the values for Hs. 15c appear more dispersed, and, like Hs. 15b, the ratio appears to be slightly higher. We can perhaps attribute that to the nature of the scribal intervention; a correction would likely only be done after removing the old ink, while for reinking, it is possible that some remnants of the old ink were still left, therefore contributing to the amount of copper detected in our secondary ink. This is particularly evident for the outlier observed in the case of Hs. 15a, where the slightly higher Cu/Fe ratio could be attributed to the detection of copper belonging to the primary ink (Fig. 9, highlighted area). This appears to be the case also for the outliers observed from the fragment Hs. 15c, suggesting a localised reinking. It is possible that the primary ink in Hs. 15c was in a better condition than Hs. 15b when the process of reinking was carried out and could explain the variations observed in the Cu/Fe ratios for this fragment, as well as the detection of copper in the spatial maps.

In the case of primary inks, data points showing no visible signs of scribal interventions from the three fragments were chosen for examination. The resulting distribution suggests a similarity in the composition of the primary ink, albeit less clearly than secondary inks. Data points corresponding to Hs. 15a appear to have a slightly lower Cu/Fe ratio corresponding to Hs. 15b and Hs. 15c, which appear to be more dispersed. The most likely reasons for these variations could be one or a combination of the following: (a) different batch of inks with slightly different ratio (not unlikely, as the fragments are not continuous textually); (b) the use of brass inkwells that could alter the ratio of the ink (adding Cu and Zn ions) during the passing of time; (c) disparity of conservation treatments of the three fragments. Alternatively, the data points could also simply be outliers, due to the large number of measurements, results of measurement uncertainty or analytical error.

The results from XRF point measurements were correlated to the results from μ-XRF spatial scans and complemented with palaeographic and philological observations to confirm the validity of the groupings. They show that the same secondary ink was used for reinking in the fragment Hs. 15a and for inserting the correction in Hs. 15b, as well as for potentially reinking sections of text in Hs. 15c. The composition of the primary ink for all three fragments was found to be comparable, thereby linking the three fragments to each other, and supporting their attribution to the same Umayyad codex.

The inks were further characterised using Infrared and Raman spectroscopy. Raman spectra for iron-gall inks have been the subject of several studies in recent years, and the widely popular non-destructive technique has seen rapid development in the field of Heritage Science36,37,38,39,40. However, a major drawback of this technique, when applied to inks on organic support, has been the interference caused by fluorescence. We encountered a high degree of interference due to fluorescence on the ink measurements, particularly for fragments Hs. 15a and Hs. 15b, which had undergone prior conservation treatment. Nevertheless, the spectra obtained could be characterised as that of iron-gall ink (Fig. 10), with peaks at 1485 cm−1, 1404 cm−1, 1336 cm−1, 1312 cm−1, 1290 cm−1, 753 cm−1, 608 cm−1 and a broad peak at 557 cm−1. Unfortunately, further information about the nature of the tannins could not be extracted from the spectra, making differentiation of the ink types impossible. The same could be said about the results obtained from Infrared spectroscopy, using the external reflection mode (ER-FTIR) (Fig. 10). Following the reported band assignments for iron-gall inks, the FTIR spectra showed peaks at around 1681cm−1, 1648 cm−1, 1540 cm−1, 1329 cm−1, 1052 cm−1 and 783 cm−1 corresponding to gallic acid in all the inks, as well as band attributed to gum arabic, at ~1376 cm−1 41,42.

Parchment

Infrared spectroscopy was also employed for the analysis of the parchment. The reflectance spectra were subjected to KK transformation and shown as absorbance (Fig. 11). The peaks at ~1660 cm−1 and ~1540 cm−1 correspond to amide I and amide II, and a peak at ~1235 cm−1, corresponding to amide III. Absorption bands corresponding to C-H stretching and bending vibrations could also be observed in all the spectra. The difference in the peak positions for Hs. 15a recto (flesh side) can be attributed to a prior consolidation treatment using conservation tissue paper (peaks corresponding to cellulose at 960 cm−1, 1095 cm−1, 1160 cm−1, 1179 cm−1, 1205 cm−1, 1242 cm−1, 1339 cm−1, 1460 cm−1, 1556 cm−1, 1644 cm−1, 2900 cm−1)43. The peak at 869 cm−1 (in absorbance), present only on the flesh side, can be attributed to carbonates, possibly calcite. Other characteristic peaks corresponding to calcite could not be identified, due to both the overlap of bands with the proteins and the peak distortions resulting from the external reflectance mode. The presence of carbonates exclusively on one side of parchment hints towards a surface treatment of lime or chalk for the preparation of the flesh side only, possibly to make its surface more homogenous and similar to the hair side. The examination of the writing support, as expected, provided no further information about the similarity between the three fragments.

Discussion

Both the palaeographical, philological and material analysis support the hypothesis that the three fragments were originally part of the same manuscript. In particular, the results obtained with XRF spectroscopy showed that all three fragments were written with a vitriolic iron-gall ink of a similar composition.

Comparing the palaeographic features and the layout of the fragments with other existing Umayyad Qurʾāns showed that they match with an original larger codex on parchment, of which the most substantial part is nowadays kept in the manuscript collection of Dār al-Kutub in Cairo, as MS Rasid 113 (henceforth, the Cairo codex) and is accessible through the digitised images from the Bergsträsser archives within the framework of Corpus Coranicum project (https://corpuscoranicum.de/en/manuscripts/1335/page/0r). The codex was written in the Umayyad script style at least by three scribes, and, contrary to what is usually observed in other Umayyad codices, is characterised by the absence of coloured round dots used to mark vowels and the absence of decorative illuminated bands to mark the end of a surah—as observed in Table 17 in Moritz and the images from the Bergsträsser archives. Although the three Münster fragments are small, they provide enough material for comparison with the Dār al-Kutub leaves, as they display the same letter shapes observed on the leaves that once preceded fragment Hs. 15b. The Bergsträsser archive images cover Q.10 from vv.3-12 and 17-51, while fragment Hs. 15b preserves the end of the same surah. Notable identical letter shapes include the final qāf with its rightward descender, the final or isolated yāʾ with a triangular shape, and the final mīm whose tail forms part of the elongated body of the letter. The fragments and the Cairo leaves share further palaeographic features, such as the distinctive combination of letters—for example, the final lām and hāʾ in allāh descending along a continuous oblique line; mīm and final nūn connected by the mīm’s body ending in the nūn’s descender; the lām-alif ligature with a semi-circular alif—but also the strokes arranged in columns marking the end of single verses and the horizontal lines used as end-of-line fillers. The Cairo codex has a colophon—reproduced by Moritz in 1905—referring to the endowment to ‘the old mosque of Fusṭāṭ’, the ancient urban foundation of Cairo, which implies it was donated to the Mosque of ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ (d. 664), after the foundation of the ‘new mosque’ of Ibn Tūlūn in 876-9 CE44,45. The three Münster fragments were likely already detached from the original artefact when Gotthelf Bergsträsser (1866-1933) photographed the codex in the 1920s or 1930s46,47. In fact, they do not figure amongst the 471 pictures of the manuscript, catalogued as qāf 3, maṣāḥif 387 in the Bergsträsser archives. Other fragments and leaves had likely already been detached from this originally larger codex, which consisted of 332 leaves, on the basis of the 1893 Catalogue48. As mentioned, a thorough investigation of this manuscript’s provenance history will be the subject of a separate publication.

Back to the XRF results on the Münster fragments, a second ink was observed, likely corresponding to a later scribal intervention. It was identified as a variant of iron-gall ink, with no significant impurities present. This variant of iron-gall ink is not uncommon in the Arabic world, and has previously been detected in other manuscripts from the same time period, coexisting with vitriolic iron-gall ink16. In the Münster fragment, the secondary ink was likely used for a specific purpose: to reink sections of faded text (on Hs. 15a and perhaps on localised spots on Hs. 15c) and to insert a correction (on Hs. 15b). This result is particularly important as—at a first visual examination—the ink used to insert the correction appeared to be identical to the primary ink, an observation contradicted by material analysis.

The phenomenon of reinking suggests a significant gap in time between the primary and secondary writing processes, since the fading of the primary ink on the flesh side of fragment Hs. 15a would have occurred gradually, likely within a span of several years or even decades. The fading of the ink is likely caused by the difference in the adherence of ink to the flesh side compared to the hair side, along with the tendency of iron-gall ink to change colour over time49,50,51. The presence of similar secondary inks in the reinking and the correction implies that the latter occurred at the same time as the reinking, as it seems unlikely that inks with the same composition would have been used in two separate, chronologically distant production stages. Thus, both reinking and correction belong to the same second layer in the life cycle of the object. The practice of selectively reinking faded text is well known in medieval Arabic literature as jandara, rewriting or filling in the blanks in a faded text to make it readable in a way that faithfully reconstructs the script as closely as possible to the original one52. The practice of reinking Qurʾānic text, along with other interventions aimed at preserving the integrity of the manuscript, was considered a pious act in Islam and was therefore highly valued. In this specific case, since reinking would only have been carried out once the text appeared faded, the use of the same secondary ink for both reinking and correction suggests that the missing word ḥanīf in Q.10:105:4-7 went unnoticed for a while, at least for a few decades. The word ḥanīf is a fundamental term with an important cultic dimension denoting a ‘cultic worshipper’, a person who worships God through rites such as cultic prayer, sacrifice and pilgrimage23. As it is rather improbable that the missing word went unnoticed and was only inserted when the manuscript was restored to fill the blanks of the faded text, it is likely that the text was not read nor checked during the time that passed between its production and the fading of its text.

This observation contrasts with the importance of the book project produced under the Umayyads (i.e. monumental size, professional copyists and use in a mosque). When compared with other Umayyad Qurʾāns, we notice that the iconographic motifs of the Umayyad visual culture have not been added to complete the layout of the page of the codex53. The absence of vowel-dots and decorative ornaments is striking, too. Given that such an investment of time and money for an expensive and prestigious project was not followed by a (proof-)reading of the text, the most plausible explanation would be that the project was abandoned, and the leaves were left unused for some time53. The beginning and consecutive abandonment of the project, therefore, could have happened during the last decades of the Umayyad rule, around 720–730 to 750 CE, a period during which Umayyad unity began to unravel. Then, the reinking and correction likely occurred only when the historical artefact was endowed to the mosque of ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ in Fusṭāṭ after 876-9 CE and its text was inspected.

The combination of non-destructive material analysis and historical-philological analysis enabled us to identify a stratigraphy in the object and to formulate a chronology for the production of the manuscript. However, dating of early Qurʾānic manuscripts has been subjected to several scholarly discussions since the last century. This includes the much-debated use of radiocarbon analysis in the past decades for dating Qurʾānic fragments on parchment, often resulting in contradictory interpretation10,54,55,56. At the beginning of this case study, radiocarbon analysis of three pieces of parchment taken from Hs. 15c, was requested by the Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies at the University of Münster and performed by Irka Hajdas at the ETH Laboratory in Zurich (Fig. 12). As Hs. 15c was, to the best of our knowledge, the only fragment of the three to not have undergone any conservation treatment, it was considered to be the most suitable for C14 analysis. Our initial hypothesis, which suggests the period around 720–730 to 750 CE for the writing of the text of the whole Cairo codex, is included within the timeframe (666 to 774 CE with a 95.4% confidence range) resulting from C14 analysis of the parchment of one of the three fragments and exactly corresponds to one of the two proposed time windows (723–774 CE). Therefore, a combination of different approaches—philological, codicological, ink analysis and radiocarbon analysis—allowed us to place these fragments in their historical time period.

To summarise, the Münster fragments are the remains of three leaves that belonged to the same historical artefact, endowed to the mosque of ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ in Fusṭāṭ before 876-9 CE and now preserved almost completely at the Dār al-Kutub in Cairo. Other leaves, now dispersed across various collections, have been identified during this research through online images. However, at the time of submitting this article, we were unable to consult either the scattered leaves or the codex preserved in Cairo in their original form. The study of their provenance forms part of ongoing research.

With the complementary strategy of scientific analysis and philological-historical observations, we were able to re-establish the connection between the three fragments and between these orphaned objects and their original codex. This cross-disciplinary approach that merges archaeometry and historical-philological analysis, which we call archaeometric philology13, enabled the understanding of the layers in the life cycle of the object. The results from scanning μ-XRF spectroscopy proved to be the determining factor in identifying the composition of the two inks, and, when combined with XRF spot analysis, allowed us to distinguish the two production stages. Thanks to this identification, we could place the fragments into their original historical context, thereby dating them. The exceptionality of the unfinished Umayyad codex, of which the three Münster fragments were a part, has been explained by applying archaeometric philology. The methodology showed its potential in future applications to understand the history of fragments and fragmented codices.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the University of Hamburg repository: [https://doi.org/10.25592/uhhfdm.17564].

References

Hilali, A. & Burge, S. R. The Making of Religious Texts in Islam: The Fragment and the Whole (Gerlach Press, 2019).

Déroche, F. La Transmission Écrite Du Coran Dans Les Débuts de l’Islam: Le Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus Vol. 5 (Brill, 2009).

Déroche, F. Inks and page setting in early Qurʾānic manuscripts. in From codicology to technology: Islamic manuscripts and their place in scholarship (eds Brinkmann, S. & Wiesmüller, B.) (Frank & Timme, 2012).

Leventhal, R. M. & Daniels, B. I. Orphaned objects, ethical standards, and the acquisition of antiquities. DePaul J. Art. Technol. Intellect. Prop. Law 23, 339 (2012).

Khan, Y. & Lewincamp, S. Characterisation and analysis of early Quran fragments at the library of Congress. In Contributions To The Symposium On The Care and Conservation of Middle Eastern Manuscripts (Sloggett R. Ed) 55–65 (University of Melbourne, 2008).

Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script (Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 2005).

Oubelkacem, Y. et al. Parchments and coloring materials in two IXth century manuscripts: on-site non-invasive multi-techniques investigation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 247, 119093 (2021).

Roger, P., Malika, S. & Déroche, F. Les matériaux de la couleur dans les manuscrits arabes de l’Occident musulman. Recherches sur la collection de la Bibliothèque générale et archives de Rabat et de la Bibliothèque nationale de France (note d’information). Comptes Rendus Séances Acad. Inscr. Belles Lett. 148, 799–830 (2004).

Vieira, M. et al. Organic red colorants in Islamic manuscripts (12th-15th c.) produced in al-Andalus, part 1. Dyes Pigments 166, 451–459 (2019).

Youssef-Grob, E. M. Radiocarbon (14C) Dating of Early Islamic Documents: Background and Prospects. in Qurʾān Quotations Preserved on Papyrus Documents, 7th-10th Centuries: And the Problem of Carbon Dating Early Qurʾāns (eds Kaplony, A. & Marx, M.) 139–187. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004376977 (Brill, 2019).

Arias, T. E., Montes, A. L., Bueno, A. G., Benito, A. D. & García, R. B. A Study about colourants in the arabic manuscript collection of the Sacromonte Abbey, Granada, Spain. A new methodology for chemical analysis. Restaur. Int. J. Preserv. Libr. Arch. Mater. 29, 76–106 (2008).

Díaz Hidalgo, R. J. et al. The making of black inks in an Arabic treatise by al-Qalalūsī dated from the 13th c.: reproduction and characterisation of iron-gall ink recipes. Herit. Sci. 11, 7 (2023).

Marotta, G., Fedeli, A., Sathiyamani, S. & Colini, C. Archaeometric philology for the study of deteriorated and overlapping layers of ink: the colour code of an early Qur’anic fragment. Eur. Phys. J. 140, 446 (2025).

Sathiyamani, S., Tillier, M., Vanthieghem, N. & Colini, C. Leafing through time: Ink Analysis of the oldest Qur’ān on Papyrus. Metrol. Archeol. Cult. Herit. 1, 851–855 (2023).

Rabin, I. et al. Identification and classification of historical writing inks in spectroscopy: a methodological overview. Comp. Orient. Manuscr. Stud. Newsl. 3, 26–30 (2012).

Colini, C., Shevchuk, I., Huskin, K. A., Rabin, I. & Hahn, O. A New Standard Protocol for Identification of Writing Media. in Exploring Written Artefacts Vol. 25 (ed. Quezner, J. B.) 161–182 (De Gruyter, 2021).

Déroche, F. Qur’ans of the Umayyads: A First Overview (Brill, 2013).

Blair, S. Islamic Calligraphy (Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

Marsham, A. The Umayyad World (Routledge, 2020).

Rose-Beers, K. ‘Reading with Conservators: the language of book archaeology.’ In By the Pen and What They Write: Writing in Islamic Art and Culture (The Biennial Hamad bin Khalifa Symposium on Islamic Art) (eds Blair, S. & Bloom, J. M.) (Yale University Press, 2017).

Rose-Beers, K. ‘Preparing to conserve an early Qur’an manuscript in the collections of Sir Alfred Chester Beatty: Exploring the materiality of the early Islamic book’. in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 17 (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2021).

Arberry, A. J. The Koran Interpreted (Oxford University Press, 1964).

Goudarzi, M. Unearthing Abraham’s Altar: the cultic dimensions of dīn, islām, and ḥanīf in the Qurʾan. J. East. Stud. 82, 77–102 (2023).

Volpi, F. et al. Unveiling materials and origin of reused medieval music parchments by portable XRF and ER-FTIR. Microchem. J. 205, 111224 (2024).

Hahn, O., Wolff, T., Feistel, H.-O., Rabin, I. & Beit-Arié, M. The Erfurt Hebrew Giant Bible and the experimental XRF analysis of ink and plummet composition. Galim 51, 16–29 (2007).

Bosch, S., Colini, C., Hahn, O., Janke, A. & Shevchuk, I. The Atri fragment revisited I: multispectral imaging and ink identification. Manuscr. Cult. 2018, 141–156 (2018).

Hahn, O. Analyses of iron gall and carbon inks by means of X-ray fluorescence analysis: a non-destructive approach in the field of archaeometry and conservation science. Restaurator 31, 41–64 (2010).

Malzer, W., Hahn, O. & Kanngiesser, B. A fingerprint model for inhomogeneous ink–paper layer systems measured with micro-x-ray fluorescence analysis. X-Ray Spectrom. 33, 229–233 (2004).

Nehring, G., Gordon, N. & Rabin, I. Distinguishing between seemingly identical inks using scanning µXRF and heat maps. J. Cult. Herit. 57, 142–148 (2022).

Zaffino, C., Guglielmi, V., Faraone, S., Vinaccia, A. & Bruni, S. Exploiting external reflection FTIR spectroscopy for the in-situ identification of pigments and binders in illuminated manuscripts. Brochantite and posnjakite as a case study. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 136, 1076–1085 (2015).

Nodari, L. & Ricciardi, P. Non-invasive identification of paint binders in illuminated manuscripts by ER-FTIR spectroscopy: a systematic study of the influence of different pigments on the binders’ characteristic spectral features. Herit. Sci. 7, 7 (2019).

Estupiñán Méndez, D. & Allscher, T. Advantages of external reflection and transflection over ATR in the rapid material characterization of negatives and films via FTIR spectroscopy. Polymers 14, 808 (2022).

Mrusek, R., Fuchs, R. & Oltrogge, D. Spektrale Fenster zur Vergangenheit Ein neues Reflektographieverfahren zur Untersuchung von Buchmalerei und historischem Schriftgut. Sci. Nat. 2, 68–79 (1995).

Colini, C. “I tried it and it is really good”: replicating Recipes of Arabic black inks. in Traces of Ink (ed. Raggetti, L.) 131–153 (Brill, 2021).

Ghigo, T., Bonnerot, O., Buzi, P., Krutzsch, M. & Hahn, O. An attempt at a systematic study of inks from Coptic manuscripts. Manuscr. Cult. 157–164 (2018).

Espina, A., Sanchez-Cortes, S. & Jurašeková, Z. Vibrational study (Raman, SERS, and IR) of plant gallnut polyphenols related to the fabrication of iron gall inks. Molecules 27, 279 (2022).

Retko, K., Legan, L., Kosel, J. & Ropret, P. Identification of iron gall inks, logwood inks, and their mixtures using Raman spectroscopy, supplemented by reflection and transmission infrared spectroscopy. Herit. Sci. 12, 212 (2024).

Lee, A. S., Mahon, P. J. & Creagh, D. C. Raman analysis of iron gall inks on parchment. Vib. Spectrosc. 41, 170–175 (2006).

Espina, A., Cañamares, M. V., Jurašeková, Z. & Sanchez-Cortes, S. Analysis of iron complexes of tannic acid and other related polyphenols as revealed by spectroscopic techniques: implications in the identification and characterization of iron gall inks in historical manuscripts. ACS Omega 7, 27937–27949 (2022).

Vassiou, E., Lazidou, D., Kampasakali, E., Pavlidou, E. & Stratis, J. Iron gall ink from historical recipes on organic substrates and their study before and after accelerated ageing with µ-RAMAN Spectroscopy and SEM-EDS. J. Cult. Herit. 66, 584–592 (2024).

Boyatzis, S. C., Velivasaki, G. & Malea, E. A study of the deterioration of aged parchment marked with laboratory iron gall inks using FTIR-ATR spectroscopy and micro hot table. Herit. Sci. 4, 13 (2016).

Kaminari, A.-A., Boyatzis, S. C. & Alexopoulou, A. Linking infrared spectra of laboratory iron gall inks based on traditional recipes with their material components. Appl Spectrosc. 72, 1511–1527 (2018).

Geminiani, L. et al. Differentiating between natural and modified cellulosic fibres using ATR-FTIR. Spectrosc. Herit. 5, 4114–4139 (2022).

Rice, D. S. The Unique Ibn Al-Bawwab Manuscript (Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt, 1983).

Moritz, B. Arabic Palaeography: A Collection of Arabic Texts from the First Century of the Hidjra till the Year 1000 (Khedivial Library, 1905).

Marx, M. The Koran according to Agfa: Gotthelf Bergsträssers Archiv der Koranhandschriften. Trajekte 19, 25–29 (2009).

Marx, M. Khedivial Library, today: Egyptian National Library and Archives: ‘qāf 3’ (Gotthelf Bergsträßer archives) [maṣāḥif 387]. in Manuscripta Coranica (ed. Marx, M.) (Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften).

Muhammad, H. Fihrist Al Kutub Al ʻarabīyah Al Maḥfūẓah Bi Al Kutubkhānah Al Khidīwīyah Vol. 1 (Dar al-Kutub wa-al-Wathaʾiq al-Qawmiyya, 1893).

Reissland, B. & Cowan, M. W. The light sensitivity of iron gall inks. Stud. Conserv. 47, 180–184 (2002).

Ferretti, A., Sabatini, F. & Degano, I. A model iron gall ink: an in-depth study of ageing processes involving gallic acid. Molecules 27, 8603 (2022).

Tse, S., Guild, S., Orlandini, V. & Trojan-Bedynski, M. Microfade testing of 19th century iron gall inks. Res. Tech. Stud. Spec. Group Postprints 2, 56–68 (2010).

Hilali, A. The Sanaa Palimpsest: The Transmission of the Qurʾan in the First Centuries AH (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Meinecke, K. Umayyad visual culture and its models. In The Umayyad World 103–129 (Routledge, 2020).

Fedeli, A. Dating early Qur’anic manuscripts: reading the objects, their texts and the results of their analysis. in Early Islam: the sectarian milieu of late antiquity (ed. Dye, G.) 113–129 (Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2023).

Marx, M. J. & Jocham, T. J. Radiocarbon (14C) Dating of Qur’an Manuscripts’. in Qurʾān Quotations Preserved on Papyrus Documents, 7th-10th Centuries: And The Problem of Carbon Dating Early Qurʾāns Vol. 2, 188 (2019).

Grohmann, A. The problem of dating early Qur’āns. Der Islam 33, 212–231 (1958).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude towards the Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies, University of Münster, particularly Dr. Monika Springberg and Henrik Hördemann for providing the fragments for scientific investigation and to Dr. Norbert Heinrich Holl for sharing the details about the history of these acquisitions. The authors would also like to thank R. B. Davidson MacLaren and Leila Amineddoleh for their valuable insights that shaped our publication. Great appreciation also goes to Dr. Irka Hajdas and ETH Zurich for sharing with us the results of the radiocarbon analysis. Finally, the authors thank our colleagues at CSMC, particularly Kyle Ann Huskin and Dr. Greg Nehring, for their valuable feedback and advice. The research for this project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC 2176 ‘Understanding Written Artefacts: Material, Interaction and Transmission in Manuscript Cultures’, project no.390893796. The research was conducted within the scope of the CSMC at Universität Hamburg. We acknowledge financial support from the Open Access Publication Fund of Universität Hamburg.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. carried out the material analysis with contributions from G.M. and C.C.; S.S. performed the data evaluation and interpretation; A.F. did the philological and historical analysis and aided in the interpretation of the data; S.S. and A.F. wrote the paper with input from G.M. and C.C.; C.C. conceptualised and supervised the project. All authors reviewed and revised the entire text and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sathiyamani, S., Fedeli, A., Marotta, G. et al. From fragments to text and ink: a scientific and historical study of an Umayyad Qur’ān. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 478 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02028-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02028-8