Abstract

The wood of Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck exhibits significant degradation due to the intertidal burial environment. The shipwreck wood mainly consists of Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) and Chinese cypress (Cupressus funebris), with different degradation characteristics. Chinese fir (BD: 0.19–0.33 g/cm³; MWC: 184.8–463.5%), used in load-bearing structures, displayed mild to severe degradation, while cypress (BD: 0.24–0.38 g/cm³; MWC: 171.7–280.6%) applied to joint components exhibited milder degradation. Both species showed substantial holocellulose loss (28–65% of sound wood). FTIR and XRD analyses revealed that both wood species had undergone hemicellulose degradation and cellulose crystallinity reduction, resulting in cell wall delamination and mechanical strength reduction, while residual lignin maintained structural stability, showing a polysaccharide degradation-lignin support pattern. EDS and XRD analyses revealed the presence of inorganic fillers (SiO2, CaCO3, and FeS2) in wood, with iron content ranging from 0.1–13%. These findings provide valuable scientific references for the conservation of the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck wood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

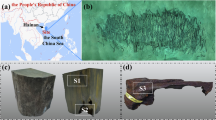

Wenzhou Shuomen ancient Port Site (28°01′34″-28°01′36″ N, 120°38′06″-120°39′30″ E) is located along Wangjiang East Road in Lucheng District, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province. As the largest and most complete port site from the Song and Yuan dynasties discovered to date, it is renowned for its unique “port-city-waterway” integrated spatial layout, which substantiates Wenzhou’s historical status as a “millennium commercial port ”1.

Archaeological excavations have revealed the remains of a barbican, city gates, and ancient docks, along with three ancient shipwrecks designated as No.1, 2, and 3. The Wenzhou No.1 Shipwreck, preserved in two sections measuring 4.7 and 6.4 m in length, features a pointed bow approximately 2 m wide and a midsection with a maximum residual width of 4.5 m. Components such as the keel, bottom cabin, bulkheads, deck, and mast are relatively well-preserved, making the ship’s structure clearly discernible. Identified as a typical Northern Song Dynasty Fuchuan style ship—renowned for its robust hull and high cargo capacity, this shipwreck offers tangible evidence of the advanced shipbuilding techniques practiced in the Song dynasties.

The wooden components of the Wenzhou No.1 Shipwreck, as waterlogged archaeological wood (WAW) in an intertidal burial environment, have undergone significant deterioration due to long-term microbial degradation and seawater erosion. Research shows that when WAW is exposed to air, its preservation state shifts from anaerobic to aerobic conditions, accelerating cellulose hydrolysis and microbial erosion, leading to rapid wood degradation2. Particularly for wood containing iron sulfide compounds, the oxidation of these compounds can cause wood acidification and the formation of crystalline growth pressure, exacerbating the disintegration of the wood cell wall structure3. These degradation factors pose a serious threat to the long-term preservation of wooden shipwrecks. Therefore, scientifically assessing the preservation status of the wood, and formulating targeted conservation strategies are critical for safeguarding wooden shipwrecks.

Currently, maximum water content (MWC) and basic density (BD) are widely used to assess the physical degradation degree of archaeological wood4. Studies have shown that the degree of wood degradation is positively correlated with the MWC and negatively correlated with the BD. According to the MWC, the degradation degree of WAW can be classified into three levels: MWC < 185% is Level I, indicating mild degradation; 185% ≤ MWC ≤ 400% is Level II, indicating moderate degradation; and MWC > 400% is Level III, indicating severe degradation5. It is important to note that these classification were primarily developed based on softwood analyses, and their applicability to hardwood species requires further validation.

Furthermore, researchers can combine techniques including wet chemical analysis, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to systematically characterize the degradation characteristics of archaeological wood at the molecular and microstructural levels6,7. However, degradation characteristics vary significantly with burial environment and wood species. For example, wood from the Nanhai No.1 shipwreck experiences degradation of hemicellulose and cellulose, accompanied by the deposition of sulfide compounds, mainly due to marine environmental erosion8,9. The ebony from the No.2 shipwreck site on the northwestern slope of the South China Sea primarily undergoes hemicellulose degradation, which can be attributed to its anatomical structure and the high-pressure environment of the deep sea10. Additionally, wood remains in the chariot pit of the Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huang show more significant lignin degradation, likely caused by the penetration of corrosion products from copper components11.

The Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck represents the wooden shipwreck discovered within a muddy sedimentary layer of an intertidal zone in China. To ensure the systematic conservation of the hull, the wood species used in this ship were first identified. Subsequently, the physical degradation degree of the wood was evaluated using MWC and BD. Wet chemical methods, combined with FTIR and XRD, were employed to analyze the chemical degradation characteristics of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), XRD, and inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) were used to determine the types and contents of inorganic sediments in the wood, thereby comprehensively assessing the degradation characteristics of the shipwreck wood. The research findings not only provide valuable scientific references for the conservation of the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck but also offer insights into the preservation of archaeological wood in intertidal environments.

Methods

Wood sampling and preparation

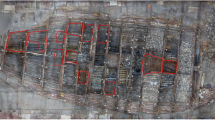

Based on the cultural relic value, component position, component type, and sampling feasibility, ten sampling points were selected on the hull and sequentially numbered from 1 to 10. Among these, point 10 corresponds to the keel, located at the bottom of the hull and thus not shown in Fig. 1. The distribution of the remaining sampling points is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Before wood sampling, all silt adhering to the wood surface was removed using deionized water. Subsequently, wood samples were extracted from the designated sampling points using a scalpel. The samples were prepared to approximate dimensions of 20 × 20 × 10 mm.

Microstructural observation and species identification

The sample was processed into 5 × 5 × 5 mm wood blocks, freeze-dried, and subsequently sectioned into transverse, radial, and tangential slices (15–20 μm thickness) using a sliding microtome (SM2010R, Leica, Germany). The sections were then stained, dehydrated, and observed under an optical microscope to analyze the microscopic structural and identify the wood species.

For further analysis, a separate wood block was planed flat, freeze-dried, and mounted on the specimen stage with conductive adhesive. The sample was gold-sputter-coated to enhance conductivity and observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; ZEISS Sigma 360, Germany) equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) to characterize microstructure and morphology.

Physical degradation characteristics (MWC and BD)

To determine the MWC and BD, wood blocks were cut from each sample. Before testing, the samples were cleansed with distilled water. The calculation of MWC for each wood block is detailed in Eq. 1.

The BD is calculated using Eq. 2.

Where m is the mass of the waterlogged archaeological wood, m0 is the mass of the oven-dry wood, and vb is the volume of the waterlogged archaeological wood.

Determination of holocellulose, lignin, and ash contents

The relative content of holocellulose, lignin, and ash of the wood samples was determined using wet chemical analysis. Samples were milled to a particle size of 60–100 mesh. Holocellulose content was determined via NaClO₂ delignification followed by acid hydrolysis, while lignin content was measured using the Klason method. Ash content was measured by combustion at 575 °C to constant weight, with all these methods described by Wang et al.12.

Chemical and structural degradation characteristics analysis

The chemical composition of the wood samples was analyzed using an FTIR spectrometer (IS10, Nicolet, USA). Samples were ground to 120 mesh, dried at 60 °C to constant weight, and mixed with KBr (1:100 mass ratio). The mixture was pressed into transparent films and scanned over 4000–400 cm⁻¹. Three replicate measurements per sample were averaged for spectral analysis.

The cellulose crystalline structure and inorganic phase composition were characterized using an XRD diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany). Samples were milled to 80 mesh, dried at 60 °C to constant weight, and analyzed under the following conditions: Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), 40 kV, 40 mA, 1.5°/min scan speed, 0.05° step size, and 2θ range of 5°–45°.

For cellulose characterization, three replicate scans per sample were averaged, and the crystallinity index (CrI) was calculated using the Segal method (Eq. 3)10

Where I200 represents the maximum diffraction intensity of cellulose at the (200) crystal plane, and Iam is the scattering intensity of the background diffraction from the amorphous region of cellulose near 2θ at 18°.

Concurrently, the XRD spectra were analyzed for inorganic components. Diffraction patterns were matched against the PDF database to identify crystalline minerals based on peak positions (2θ) and relative intensities.

Determination of sulfur and iron content

Wood samples were ground into 200 mesh, and 10 mg of the powder was accurately weighed into a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) digestion vessel. A digestion solution consisting of 0.75 mL concentrated nitric acid and 0.25 mL hydrochloric acid was added to the vessel. After thorough mixing, the sample was subjected to microwave-assisted digestion using a system programmed to heat to 260 °C. Following digestion, the solution was cooled to room temperature and quantitatively diluted to a final volume of 20 mL with 3% (v/v) nitric acid solution. The solution was then filtered through syringe filters, and the sulfur and iron contents were determined using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES)12. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate, and the average values were reported as the final results.

Results

Wood Species Identification

To characterize the wood species used in the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck, species identification of ten wood samples was conducted through optical microscopic analysis of wood anatomical features, as shown in Table 1. The results indicate that the hull was constructed using Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) and Chinese cypress (Cupressus funebris).

In Chinese fir, the earlywood tracheids in the transverse section exhibit irregular polygonal shapes, while the latewood tracheids are rectangular to polygonal. The axial parenchyma is diffuse or arranged in tangential bands (Fig. 2a). In the tangential section, the wood rays are predominantly uniseriate, occasionally biseriate (Fig. 2b). In the radial section, the bordered pits on the axial tracheids are mostly uniseriate, and the cross-field pitting is of the Chinese fir type (Fig. 2c)13.

Microscopic images showing the anatomical features of Chinese fir and Chinese cypress : a Chinese fir transverse section; b Chinese fir radial section; c Chinese fir tangential section; d Cypress transverse section; e Cypress radial section; f Cypress tangential section. All images are stained and observed under an optical microscope.

In Chinese cypress, the earlywood tracheids in the transverse section are nearly circular to polygonal, and the axial parenchyma is diffuse or in clustered aggregates, often containing dark resin contents (Fig. 2d). In the tangential section, the wood rays are uniseriate (Fig. 2e). In the radial section, the bordered pits on the axial tracheids are mostly uniseriate, and the cross-field pitting is of the cypress type (Fig. 2f)13.

Chinese fir exhibits a unique combination of low density and high strength, making it suitable for manufacturing load-bearing components, such as bottom planks, bulkheads, and keels. This optimal strength-to-weight ratio allows for lightweight construction while meeting structural stiffness and strength requirements. In contrast, cypress contains abundant phenolic tyloses within its axial parenchyma, which can block microbial penetration and disrupt metabolic activity, thereby providing inherent antimicrobial properties. Combined with its high mechanical strength and impact resistance, cypress was commonly used for critical structural joints, including the bow, stern, and seam-reinforcing planks. This species-specific material selection reflects the ancient Chinese shipbuilding logic of ‘material-function compatibility’, as supported by the anatomical characteristics of the wood and their structural roles in the hull.

Beyond material-function compatibility, ancient shipbuilders also prioritized resource availability and procurement efficiency. From a biogeographical perspective, Chinese fir and cypress are found in mixed forests in the coastal hilly regions of Zhejiang and Fujian (27°–28°N), closely aligning with the location of Wenzhou Shuomen ancient Port. The Ming Dynasty text Tiangong Kaiwu: Boats and Carts14 records, “Shipbuilding materials in Fujian and Guangdong are sourced from camphor and fir, while in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, pine and cypress are used together.” This description matches the combination of fir and cypress used in the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck, providing empirical evidence for the ancient shipbuilding logic of “adapting to local conditions and sourcing materials nearby”.

Physical degradation characteristics

Since the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck was constructed using Chinese fir and Chinese cypress, the degradation state of wood samples from this shipwreck can be quantitatively assessed through two key degradation indicators: MWC and BD (Table 1). Chinese fir specimens displayed a wide degradation range, with MWC values spanning 184.8 to 463.5% and BD values between 0.19 and 0.33 g/cm³, encompassing mild, moderate, and severe degradation levels. In comparison, Chinese cypress specimens exhibited better preservation, with MWC limited to 171.7–280.6% and BD maintained at 0.24–0.38 g/cm³, predominantly within the mild to moderate degradation range. Compared to reference values for sound wood (Chinese fir: 0.33 g/cm³; Chinese cypress: 0.38 g/cm³), the BD reductions reached 22–57% for Chinese fir and 31–56% for Chinese cypress, confirming significant degradation of their components.

The most severe degradation was observed in the Chinese fir stern plate (sampling point 6), where the BD decreased to 0.19 g/cm³ (42.2% of sound wood reference value) accompanied by an exceptionally high MWC of 463.5%, suggesting nearly complete cell wall collapse. This condition represents a typical case of severe degradation in marine archaeological wood. In contrast, the most degraded Chinese cypress sample (sampling point 1) maintained significantly better structural integrity, with MWC and BD values of 280.6% and 0.24 g/cm³, respectively, outperforming many Chinese fir specimens. This differential degradation behavior can be attributed to cypress’s inherent material properties, including higher concentrations of phenolic extractives that provide natural resistance against microbial attack, combined with its naturally higher density (0.38 g/cm³ in sound wood versus 0.33 g/cm³ for Chinese fir), which reduces water permeability and enhances structural stability in marine environments.

The study revealed a significant negative correlation between MWC and BD values. This relationship can be explained by the degradation mechanism where reduced wood density leads to increased porosity, which in turn enhances water retention capacity. The elevated moisture content further accelerates structural breakdown through both chemical hydrolysis and biological activity, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of progressive deterioration.

Morphological analysis

Microscopic morphological observations (Fig. 3) of typical samples of Chinese fir (Sample 2) and Chinese cypress (Sample 8) revealed distinct degradation features between early and late wood cells in the two species.

For Chinese fir, the early wood tracheids showed remarkable delamination between cell wall layers and cell lumen deformation (Fig. 3a). Wood chemistry studies indicate that hemicellulose, which acts as a matrix component between microfibrils, undergoes degradation, leading to the loss of adhesion between the S2 layers of the cell wall13. This suggests that the delamination observed in the earlywood cell walls of Chinese fir is likely attributable to hemicellulose degradation. Additionally, the relatively thin walls of earlywood tracheids make the cavities highly susceptible to collapse and deformation during dehydration.

In contrast, the latewood cells of Chinese fir exhibited better preservation, largely retaining their original shape. Delamination between layers was rare, although occasional holes caused by microbial degradation were observed on the cell walls (Fig. 3b). This can be attributed to the thicker cell walls and higher lignin content of latewood tracheids, which collectively provide enhanced mechanical stability and biological resistance.

Chinese cypress specimens showed similar but less pronounced degradation features. While earlywood cell walls displayed cell wall delamination and microbial pitting (Fig. 3c), and some latewood cells exhibited minor delamination (Fig. 3d), both earlywood and latewood cells remarkably retained their original cellular morphology. This superior structural stability suggests that cypress maintains better integrity of its primary cell wall components during waterlogging, potentially due to the antimicrobial properties of tyloses and inherent differences in cell wall composition compared to Chinese fir.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showing the microstructural characteristics of WAW: a Earlywood tracheids in Chinese fir, with red arrow indicating cell wall delamination. b Latewood tracheids in Chinese fir, where yellow arrows point to cell wall pores and red arrow denotes cell wall delamination. c Earlywood tracheids in Chinese cypress, with red arrows showing cell wall delamination and yellow arrow indicating microbial pitting. d Latewood tracheids in Chinese cypress, with red arrow highlighting cell wall delamination.

Holocellulose, lignin, and ash contents

The primary chemical components of wood include cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Cellulose, as the main structural component, forms linear macromolecules through β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, which aggregate into crystalline microfibrils. These microfibrils exhibit axial orientation within the cell wall, conferring mechanical strength to wood13. Hemicellulose, a short-chain polysaccharide, fills the spaces between cellulose microfibrils, enhancing inter-fiber adhesion and stability13. Cellulose and hemicellulose together are referred to as holocellulose, which constitutes the skeletal material of wood. Lignin, an amorphous phenolic polymer, forms a three-dimensional network that crosslinks polysaccharides through covalent bonding, enhancing structural rigidity and decay resistance13. These components collectively form the hierarchical architecture of the wood cell wall. Ash, derived from mineral nutrients absorbed by living trees, represents the inorganic residue remaining after combustion, mainly consisting of metal oxides, such as potassium, calcium, and magnesium, along with small amounts of silicon and phosphorus compounds13. In sound wood, the relative content of holocellulose typically ranges from 65 to 75%, lignin from 25 to 29%, and ash from 0.3 to 0.5%4,13,15.

Wet chemical analysis can quantitatively determine the relative content of major chemical components in wood, such as holocellulose and lignin, providing critical data for assessing the degradation state of archaeological wood4,12. Figure 4 illustrates the content of major chemical components in wood samples from the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck. The holocellulose content of Chinese fir samples ranges from 28 to 62%, while the lignin content ranges from 17 to 41%. Notably, the ash content is significantly elevated, ranging from 1.4 to 59%. For Chinese cypress samples, holocellulose spanned 30–65%, lignin varied between 19–33% (26 ± 6%), and ash content was 4.6–19%, significantly lower than Chinese fir.

Distribution of holocellulose, lignin, and ash contents, with holocellulose-to-lignin ratio (H/L) indicated for each sample: a Chinese fir samples: red bars represent holocellulose content, blue bars represent lignin content, orange bars represent ash content, and "H/L" denotes the holocellulose-to-lignin ratio. b Chinese cypress samples: same color coding applies (red = holocellulose, blue = lignin, orange = ash), with "H/L" indicating the holocellulose-to-lignin ratio.

Compared to sound wood, both Chinese fir and Chinese cypress exhibit varying degrees of reduction in holocellulose content, indicating that holocellulose in both species has undergone degradation. However, the holocellulose content of cypress samples is higher than that of Chinese fir, suggesting a lower degree of degradation in cypress, which is consistent with the evaluation results of MWC and BD presented earlier. Meanwhile, the ash content of the shipwreck wood samples is significantly higher compared to sound wood, likely due to the infiltration of inorganic sediments into the wood12.

The lignin content in some Chinese fir and Chinese cypress samples is lower than that of sound wood, while in others, it is higher. This variation reflects methodological constraints, when organic components such as holocellulose are lost due to degradation, or when ash content increases due to mineral infiltration from the burial environment, the relative content of lignin deviates from the actual degradation state due to changes in the original composition ratios of the wood12. Specifically, the “relative content” nature of lignin analysis means that preferential loss of holocellulose can artificially inflate lignin percentages, even if absolute lignin content decreases. Conversely, mineral accumulation dilutes organic matter, skewing the lignin-to-holocellulose ratio. These factors highlight that lignin fluctuations in degraded wood often reflect compositional rebalancing rather than true lignin stability or decay.

Therefore, the holocellulose to lignin ratio (H/L) is widely used as a correction index to evaluate degradation degree, mitigating the interference of ash content. In sound wood, H/L values typically exceed 2 and decrease progressively with increasing degradation16.

For Chinese fir samples, H/L values ranged from 1.12 to 2.47. Samples 2, 6, and 7 (H/L < 2) exhibited severe degradation, whereas samples 4, 5, and 10 (H/L > 2) showed values close to sound wood, indicating mild degradation. This correlated well with basic density results.

Chinese cypress samples displayed H/L values from 1.36 to 3.35. Samples 1 and 3 had H/L < 2, while sample 9 had an H/L value significantly higher than sound wood, identifying it as the best preserved specimen.

A significant negative correlation was observed between H/L and MWC, confirming the degradation pattern: the more severe the degradation, the greater the loss of holocellulose, the higher the porosity, the higher the maximum moisture content, and the lower the H/L value. This multi-parametric relationship provides quantitative support for developing tiered conservation strategies in WAW preservation.

Chemical and structural degradation characteristics

Wet chemical analysis preliminarily indicated varying degrees of holocellulose degradation in the WAW samples. To further characterize this degradation, FTIR and XRD were used to analyze the structural changes in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. The infrared spectra of the archaeological and sound wood samples are shown in Fig. 5.

These spectra characterize structural changes in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin between sound and archaeological wood samples: a Chinese fir: The “control” curve represents the spectrum of sound (undegraded) Chinese fir, while other curves correspond to spectra of archaeological Chinese fir samples (labeled as samples 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10). b Chinese cypress: The “control” curve denotes the spectrum of sound Chinese cypress, and other curves correspond to spectra of archaeological Chinese cypress samples (labeled as samples 1, 3, 8, 9). Absorbance (arbitrary units, a.u.) is plotted against wavenumber (cm⁻¹), with key characteristic peaks marked to identify functional groups of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin.

The absorption peaks at 1155, 1050–1055, and 1365 cm⁻¹ correspond to the C-O-C vibration of cellulose and hemicellulose, the C-O stretching of secondary alcohols, and C-H deformation, respectively11,17. Compared to sound Chinese fir, all Chinese fir samples except sample 4 exhibited significantly weakened or absent absorption peaks at 1155 and 1365 cm⁻¹, while the peak at 1050–1055 cm⁻¹ shifted from a multiplet to a singlet (Fig. 5a). This suggests cleavage of glycosidic bonds (C-O-C) in cellulose and hemicellulose and disruption of C-H functional groups, with the secondary alcohol structure being converted into other oxygen-containing groups due to polysaccharide chain degradation.

Compared to sound cypress, the absorption peaks at 1155 cm−1 were absent in samples 1 and 9, the peak at 1365 cm−1 was weakened, and the peak at 1050–1055 cm−1 merged into a single peak (Fig. 5b). This suggests severe degradation of the C-O-C bonds in cellulose and hemicellulose, partial degradation of the C-H groups, and the decomposition of secondary alcohol C-O bonds into other sediments in samples 1 and 9. In contrast, the absorption peaks at these positions in samples 3 and 8 showed no significant changes, indicating better preservation of cellulose and hemicellulose in these samples.

The absorption peak at 1730 cm−1 corresponds to the C=O stretching vibration of acetyl groups in hemicellulose, which is a characteristic absorption feature of hemicellulose17,18. Compared to sound wood, this peak was absent in both Chinese fir and cypress samples (Fig. 5a, b), indicating complete degradation of the side-chain acetyl groups. As a matrix polysaccharide filling the spaces between microfibrils, hemicellulose is most abundant at the interface between the S1 and S2 layers of the cell wall. Its degradation leads to a reduction in interlayer bonding strength, causing delamination of the cell wall17,18. Additionally, hemicellulose is one of the primary contributors to wood toughness, its degradation significantly reduces wood toughness, explaining the prevalent brittle failure characteristics observed in waterlogged archaeological wood19.

The characteristic absorption peaks of lignin at 1510 and 1264 cm−1, corresponding to aromatic ring vibration and guaiacyl C-O vibration, respectively10,20. Compared to sound Chinese fir, archaeological Chinese fir samples exhibited minimal changes in peak intensities at these wave numbers (Fig. 5a), indicating limited lignin degradation. This is attributed to lignin’s three-dimensional network structure composed of phenylpropane units, which confers higher stability against enzymatic attack and ring-opening reactions compared to cellulose and hemicellulose10. In Chinese cypress samples, peak intensities remained unchanged in samples 3 and 8 but weakened in samples 1 and 9 (Fig. 5b), suggesting moderate lignin degradation in the latter. Typically, lignin is enriched in the compound middle lamella and cell corners, where it acts as an adhesive between adjacent cells13. Due to its relative stability, the compound middle lamella and cell corners of archaeological wood cell walls are generally well-preserved, maintaining the basic morphological stability of the wood10.

Cellulose is the major contributor to wood strength and rigidity, and its degradation directly affects the remaining mechanical properties of WAW. Cellulose is composed of crystalline and amorphous regions, and a higher proportion of the crystalline region generally corresponds to greater wood strength. The crystallinity index is commonly used to reflect the proportion of the crystalline region in cellulose13.

The crystallinity of cellulose in archaeological wood and sound wood is shown in Fig. 6. Sound Chinese fir and cypress exhibit the typical cellulose I diffraction pattern, with three characteristic peaks located at 2θ values of 16.5°, 22.1°, and 34.7°, corresponding to the (101), (002), and (040) crystal planes, respectively17. Based on the crystallinity calculation formula, the crystallinity of sound Chinese fir is 49.5%, while that of sound Chinese cypress is 32.7%.

These spectra assess changes in the crystalline region of cellulose, with the crystallinity index (CrI) indicated for each sample: a Chinese fir: The “control” curve represents the XRD spectrum of sound (undegraded) Chinese fir, while other curves correspond to archaeological Chinese fir samples (labeled as samples 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10). Characteristic cellulose diffraction peaks [(101), (002), (040) crystal planes] and CrI values are marked. b Chinese cypress: The “control” curve denotes the XRD spectrum of sound Chinese cypress, and other curves correspond to archaeological Chinese cypress samples (labeled as samples 1, 3, 8, 9). Characteristic cellulose diffraction peaks [(101), (002), (040) crystal planes] and CrI values are shown. Intensity is plotted in arbitrary units (a.u.) against 2θ (°).

Compared to sound Chinese fir, the (101) diffraction peak almost disappeared in samples 4, 5, 6, 7, and 10, and the intensity of the (002) diffraction peak decreased (Fig. 6a). The crystallinity of these samples decreased to varying degrees compared to sound wood, indicating partial degradation of the cellulose crystalline region, although some crystalline regions remained intact. In sample 2, both the (101) and (002) diffraction peaks were nearly absent (Fig. 6a), suggesting complete degradation of the cellulose crystalline region, with the remaining cellulose primarily in an amorphous state. This significantly compromises the wood’s strength and dimensional stability.

Compared to sound cypress, the intensity of the (101) and (002) diffraction peaks in samples 3 and 8 (Fig. 6b) exhibited less pronounced reduction, indicating moderate degradation of the cellulose crystalline region and relatively high residual mechanical strength in the wood. In samples 1 and 9, the (002) and (101) diffraction peaks almost disappeared (Fig. 6b), suggesting almost complete degradation of the cellulose crystalline region, resulting in poor strength and dimensional stability of the wood. These findings are consistent with the degradation patterns observed in the FTIR analysis.

Combined FTIR and XRD analyses reveal that hemicellulose, due to its low polymerization degree and susceptibility to enzymatic hydrolysis, is the primary target of microbial degradation. As a matrix component filling the gaps between cellulose microfibrils, hemicellulose degradation significantly reduces interlayer bonding strength in the cell wall, leading to delamination. Additionally, as a major contributor to wood toughness, hemicellulose loss impairs the wood’s toughness significantly. The degradation of the cellulose crystalline region further weakens wood rigidity and load-bearing capacity. In contrast, lignin, owing to its three-dimensional network structure, exhibits higher stability. Its enrichment in the compound middle lamella allows lignin to continue functioning as an adhesive between cells, maintaining cell contours and the macroscopic morphology of the wood.

This differential degradation pattern between polysaccharides and lignin suggests a “polysaccharide degradation-lignin support” pattern in the studied Chinese fir and cypress from intertidal waterlogged environments, ultimately resulting in the retention of the wood’s macroscopic structure but a decline in its mechanical properties.

Inorganic sediments and contents

During the microscopic morphological observation of the wood, two types of foreign sediments were identified within the cell lumens and pores: particles sediments (Fig. 7a-c) and blocky sediments (Fig. 7d).

Particles sediments were primarily concentrated in the cell corners (Fig. 7a) and on the cell wall surfaces (Fig. 7b, c). Taking sample 8 as an example, EDS analysis revealed that the main components were Fe, S, Ca, Si, and Al (Table 2). The spherical particles in the cell corners (Fig. 7a) were predominantly composed of S (74.33 at%), Fe (8.58 at%), and Ca (15.79 at%) (Table 2), which are inferred to be iron-sulfur compounds formed in the marine environment9. The irregular particles on the cell wall surfaces (Fig. 7b) were mainly composed of Fe (86–90 at%), and considering the presence of iron nails and other iron components in the ship’s structure, these particles are inferred to be iron oxides, i.e., corrosion products of iron. The flattened particles on the cell wall surfaces (Fig. 7c) were rich in Ca, S, and Al (Table 2), with S primarily originating from seawater, and Ca and Al likely derived from the soil environment.

Blocky sediments (Fig. 7d) were predominantly distributed in latewood cell lumens and rays. EDS analysis indicated the presence of S (40.31 at%), Ca (42.03 at%), Fe (10.46 at%), and Si (7.20 at%). The morphology, combined with residual fungal hyphae observed in cell lumens, suggests these are likely silt deposits derived from marine sediment infiltration.

The phase composition of foreign sediments in the archaeological wood is presented in Table 3. The detected sediments primarily include SiO₂, CaCO₃, CaSO₄·2H₂O, FeS₂, and Al₂SiO₅. Based on the wood’s burial environment, these are inferred to originate mainly from silt infiltration and enrichment. Al₂SiO₅ may also derive from mineral migration and deposition in surrounding sediments. The presence of calcium compounds (CaCO₃ and CaSO₄·2H₂O) aligns with historical records of waterproof adhesives used in shipbuilding, suggesting they may be residual mineral components from artificial treatments21.

Additionally, the formation of FeS₂ is primarily associated with the marine environment and iron components on the ship. In aerobic environments, ironware and nails on the ship are oxidized to ferric oxides or hydroxides. When oxygen is depleted, microorganisms metabolically convert ferric iron to water-soluble ferrous iron, facilitating its penetration into the wood. Seawater is rich in sulfate, which is reduced to sulfide by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) during metabolism. The resulting hydrogen sulfide gas infiltrates the wood, leading to the accumulation of sulfur, and HS⁻ reacts with Fe²⁺ to form iron sulfides3,22,23.

The enrichment of these inorganic sediments in the wood is closely related to persistent microbial corrosion, in addition to the natural porous structure of wood. SEM observations identified residual fungal hyphae in some wood cell lumens; such microorganisms secrete cellulases and hemicellulases, preferentially targeting polysaccharides in cell walls (particularly hemicellulose), leading to the loss of interlayer adhesion and the formation of numerous microvoids and channels. Meanwhile, sulfate-reducing bacteria in seawater, as key functional microorganisms, not only participate in the aforementioned sulfur metabolism (reducing sulfate to sulfide) but also produce metabolites such as organic acids, which further accelerate cellulose hydrolysis and cell wall degradation. This microbially mediated dual effect, directly degrading wood components to increase porosity and promoting chemical corrosion via metabolites, significantly enhances the penetration efficiency and deposition capacity of inorganic sediments (e.g., Fe²⁺, sulfides, siliceous particles) within the wood24.

Among the sediments, FeS₂ is a critical threat to long-term wood preservation. This compound readily oxidizes in aerobic conditions, generating acidic byproducts like sulfuric acid. These acids can acidify the wood matrix, accelerating cellulose and hemicellulose degradation and causing sustained damage to the ship’s wooden structure22. Compounding this, microorganisms further drive wood deterioration through their corrosive activity; they not only directly break down cell wall components but may also interact with iron-sulfur compounds to intensify the degradation process. Thus, in subsequent conservation treatments, prioritizing the removal of iron-sulfur compounds and the inhibition of microorganisms and mold is essential.

To formulate a conservation plan for the ship hull, it is necessary to further determine the content of sulfur and iron elements in the wood, as shown in Fig. 8. The results indicate that the sulfur content in the wood samples primarily ranges between 0.2% and 5%, with 90% of the samples exhibiting sulfur content below 2%, indicating an overall low concentration. The iron content in the wood samples varies significantly, ranging from 0.1% to 13%. The higher values correspond to the locations where iron nails were installed in the hull, suggesting that the corrosion of iron components is the primary source of iron contamination in the wood. During subsequent removal treatments for iron elements in the ship hull wood, cross-contamination must be avoided.

Discussion

Through species identification, physical property testing, microstructural observation, and chemical composition analysis, this study revealed the physical and chemical degradation characteristics of the wood from the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck. The main conclusions are as follows:

The wood species used in the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck were primarily Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) and Chinese cypress (Cupressus funebris), with Chinese fir used for load-bearing components like bottom planks, keel, and mast due to its low density and high strength-to-weight ratio, and Chinese cypress applied to critical joints like bow, stern, joint planks, for its antimicrobial properties and higher mechanical strength. This species-specific material selection exemplifies the ancient Chinese shipbuilding principle of “material-function compatibility” and reflects the Song-Yuan dynasties’ wisdom of “adapting to local conditions and sourcing materials nearby,” as corroborated by Tiangong Kaiwu.

Microstructural analysis revealed distinct degradation patterns between the two species. In Chinese fir, earlywood tracheids exhibited severe cell wall delamination and lumen deformation, attributed to hemicellulose degradation compromising the S2 layer matrix, while latewood cells, with thicker walls and higher lignin content, retained structural integrity despite localized microbial pitting. In contrast, Chinese cypress demonstrated superior morphological preservation across both earlywood and latewood, with only minor delamination, owing to its inherent resistance from phenolic extractives, tyloses, and higher native density.

Quantitative measurements confirmed these observations, with Chinese fir displayed a broad degradation range (MWC: 184.8–463.5%; BD: 0.19–0.33 g/cm³), spanning mild to severe levels. Chinese cypress, however, showed milder degradation (MWC: 171.7–280.6%; BD: 0.24–0.38 g/cm³), no samples reaching severe degradation. The negative correlation between MWC and BD underscored a self-reinforcing degradation cycle: porosity from density loss increased water retention, accelerating hydrolytic and biological breakdown.

Combined wet chemical analysis and spectroscopic characterization revealed distinct degradation pathways in Chinese fir and cypress. Both species exhibited substantial holocellulose loss (fir: 28–62%; cypress: 30–65%) compared to sound wood (65–75%), with hemicellulose—the most labile component—undergoing preferential degradation. This process was evidenced by FTIR peak disappearance at 1730 cm−1 (acetyl group cleavage) and 1155 cm−1 (glycosidic bond rupture), directly correlating with earlywood cell wall delamination observed microscopically.

Cellulose degradation further compromised mechanical properties, XRD revealed severe crystallinity reduction in fir (to 6.1–28.3% vs. sound wood’s 49.5%) and cypress (16.8–18.6% vs. 32.7%), explaining the loss of strength and dimensional stability, particularly in samples where (101)/(002) diffraction peaks nearly vanished.

Lignin demonstrated relative stability, maintaining cellular morphology through its persistent three-dimensional network in compound middle lamellae. However, methodological constraints highlighted that lignin’s “apparent” content fluctuations (fir: 17–41%; cypress: 19–33%) primarily reflected compositional rebalancing from holocellulose loss and mineral infiltration (ash up to 59% in fir), rather than absolute decay. The holocellulose-to-lignin ratio (H/L) effectively corrected these biases, with H/L < 2 confirming severe degradation, consistent with MWC-BD trends. These findings suggest a “polysaccharide degradation-lignin support” pattern in the studied Chinese fir and cypress from intertidal waterlogged environments: while hemicellulose and cellulose degradation drive porosity increases (elevating MWC) and mechanical decline, residual lignin scaffolding preserves macroscopic structure. Microstructural and elemental analyses revealed extensive infiltration of inorganic sediments in the WAW. Two types of sediments were identified: particle sediments (spherical, irregular and flattened particles) concentrated in cell corners and on cell walls, and blocky sediments occupying latewood lumens, with some distributed in rays. EDS and phase analyses demonstrated these inorganic sediments primarily consisted of SiO₂, CaCO₃, CaSO₄·2H₂O, FeS₂, and minor Al₂SiO₅. Among these, SiO2 originated from the infiltration of silt in the burial environment, CaCO3 from residues of waterproof adhesives used in shipbuilding, and FeS2 from the corrosion products of iron components on the ship, with its formation closely associated with the marine environment. Elemental quantification showed significant iron accumulation (0.1–13 wt%), strongly correlated with nail locations, while sulfur content remained comparatively low (0.2–5 wt%).

The findings of this study provide valuable scientific references for the conservation of WAW from the Wenzhou No.1 shipwreck, with broader implications for WAW preservation in intertidal environments. Recommended conservation strategies include structural reinforcement using polymer consolidants, targeted treatment of iron-sulfur compounds with removal agents and alkaline buffers, and application of antimicrobial agents to mitigate biological degradation. This integrated approach addresses the primary degradation mechanisms identified: structural collapse, metal-induced deterioration, and microbial attack.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations that should be noted. Firstly, the selected sampling points may not fully capture the degradation heterogeneity across the entire shipwreck, particularly in less accessible internal structures. Additionally, while the proposed conservation strategies are derived from observed degradation mechanisms, they require further validation through practical conservation trials. Furthermore, wet chemical analysis of lignin content may be biased by high ash content, and the holocellulose-to-lignin ratio (H/L) functions as a relative indicator rather than a direct measure of absolute lignin stability.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are provided within the manuscript or supplementary material files.

References

Cheng, Q. et al. Chinese glass ornaments from the port site of Shuo Gate, Zhejiang, China, 10th–13th Century CE. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 54 (2025).

Broda, M. & Hill, C. A. S. Conservation of waterlogged wood—past, present and future perspectives. Forests 12, 1193 (2021).

Fors, Y. & Sandström, M. Sulfur and iron in shipwrecks cause conservation concerns. Chem. Soc. Rev. 35, 399 (2006).

Kirsty E. H. & Kirsty E. H. P. A review of analytical methods for assessing preservation in waterlogged archaeological wood and their application in practice. Herit. Sci. 8, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00422-y (2020).

Macchioni, N., Capretti, C., Sozzi, L. & Pizzo, B. Grading the decay of waterlogged archaeological wood according to anatomical characterisation. The case of the Fiavé site (N-E Italy). Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 84, 54 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Characteristics of ancient shipwreck wood from Huaguang Jiao No.1 after desalination. Materials 16, 510 (2023).

Shen, D. et al. Study on wood preservation state of Chinese ancient shipwreck Huaguangjiao I. J. Cult. Herit. 32, 53 (2018).

Li, R. et al. Characterisation of waterlogged archaeological wood from Nanhai No.1 shipwreck by multidisciplinary diagnostic methods. J. Cult. Herit. 56, 25 (2022).

Zhang, H., Shen, D., Zhang, Z. & Ma, Q. Characterization of degradation and iron deposits of the wood of Nanhai I shipwreck. Herit. Sci. 10, 202 (2022).

Chu, S. et al. Degradation condition and microbial analysis of waterlogged archaeological wood from the second shipwreck site on the northwestern continental slope of the South China Sea. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 10 (2025).

Wang, D., Dong, W., Cao, L., Zhu, C. & Yan, J. Deterioration mechanisms of archaeological wood inside the bronze parts of excavated chariots from the Western Han dynasty. J. Cult. Herit. 62, 90 (2023).

Wang, X. & Li, N. Extraction of soluble salts and iron sulfides from the wood of the “Huaguangjiao I” shipwreck. Forests 14, 2432 (2023).

Liu, Y. & Zhao, G. Wood Resource Materials Science (China Forestry Publishing House, 2003).

Song, Y. Tiangong Kaiwu (Zhonghua Book Company, 2021 [Ming Dynasty]).

Singh, A. P., Kim, Y. S. & Chavan, R. R. Advances in Understanding Microbial Deterioration of Buried and Waterlogged Archaeological Woods: A Review. Forests 13, 394 (2022).

Łucejko, J. J., Zborowska, M., Modugno, F., Colombini, M. P. & Pradzynski, W. Analytical pyrolysis vs. classical wet chemical analysis to assess the decay of archaeological waterlogged wood. Anal. Chim. Acta. 745, 70 (2012).

Mastouri, A. et al. Biological-degradation, lignin performance and physical-chemical characteristics of historical wood in an ancient tomb. Fungal Biol. 129, 101588 (2025).

Chu, S., Lin, L. & Tian, X. Analysis of Aspergillus niger isolated from ancient palm leaf manuscripts and its deterioration mechanisms. Herit. Sci. 12, 199 (2024).

Wang, X., Luo, X., Ren, H. & Zhong, Y. Bending failure mechanism of bamboo scrimber. Constr. Build. Mater. 326, 126892 (2022).

Pizzo, B., Pecoraro, E., Alves, A., Macchioni, N. & Rodrigues, J. C. Quantitative evaluation by attenuated total reflectance infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy of the chemical composition of decayed wood preserved in waterlogged conditions. Talanta 132, 14 (2015).

Zhou, Y., Wang, K., Sun, J., Cui, Y. & Hu, D. Characterizing the sealing materials of the merchant ship Nanhai I of the Southern Song dynasty. Herit. Sci. 9, 48 (2021).

Fors, Y., Nilsson, T., Risberg, E. D., Sandström, M. & Torssander, P. Sulfur accumulation in pinewood (Pinus sylvestris) induced by bacteria in a simulated seabed environment: Implications for marine archaeological wood and fossil fuels. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 62, 336 (2008).

Fors, Y. et al. Sulfur and iron analyses of marine archaeological wood in shipwrecks from the Baltic Sea and Scandinavian waters. J. Archaeol. Sci. 7, 39 (2012).

Bjordal, G., Nilsson, T. & Daniel, G. Microbial decay of waterlogged archaeological wood found in Sweden Applicable to archaeology and conservation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1-2, 53 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Archaeological Talent Promotion Program of China (2024-276).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was prepared through contributions of all authors. X.W. and N.L. designed the experiments. X.W. carried out the experiments, conducted all data analysis, and wrote most of the manuscript. W.C. carried out the experiments. Y.L. and N.L. provided experimental samples, defined the research project. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Chen, W., Liang, Y. et al. Physical and chemical degradation characteristics of waterlogged archaeological wood from the wenzhou no.1 shipwreck. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 520 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02034-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02034-w