Abstract

This paper proposes a Multimodal Prototype Fusion Network (MPFN) to address challenges in paper-cut image classification, including artistic abstraction, imbalanced data, and unseen category adaptation. The framework introduces two variants: AMPFN, which dynamically fuses multimodal prototypes via cross-modal attention and residual learning, and IMPFN, a training-free model for rapid deployment. Leveraging CLIP for feature extraction, AMPFN achieves 90.71% accuracy (16-shot) on seen classes, while IMPFN attains 84.98% accuracy (16-shot) on unseen classes without training. Evaluations on paper-cut datasets and public benchmarks (PACS, ArtDL, CUB-200-2011) demonstrate superiority over existing methods. The approach mitigates data imbalance through n-shot prototypes and reduces computational costs via pre-trained features, proving robust in fine-grained and abstract art classification. This work offers a scalable solution for cultural heritage digitization and multimodal art analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intangible cultural heritage (ICH) serves to complement the tangible cultural heritage, and together they constitute the richness of human culture. In China, intangible cultural heritage represents the collective wisdom and creativity of the diverse cultures of the Chinese nation. It is the intangible cultural essence that has been nurtured by all ethnic groups in specific human and natural environments and handed down to the present day. In recent years, the advent of computers, big data and the Internet has led to the emergence of non-heritage culture as a significant area of focus for the promotion of local culture and economic development. The rapid digitisation of ICH has resulted in the generation of a substantial volume of digital data, including images and videos. The effective processing of such data represents a significant research focus in the current era.

Paper-cutting is a traditional art form that has a long history in Chinese folklore and is imbued with a strong cultural heritage and historical legacy. It is inevitable that digital innovation will play a role in the future development of paper-cutting art. Technological innovation will enable the art of paper-cutting to adapt more rapidly to the requirements of modern society and to reflect aesthetic concepts in a more timely manner, thus accelerating its development and further promoting its influence in China and internationally.

In the domain of non-heritage culture, paper-cutting is predominantly represented in the form of intricate and voluminous imagery. Presently, the accumulation of paper-cutting images is predominantly conducted manually, which necessitates a considerable investment of human resources, time, and financial resources. The majority of extant paper-cutting databases are organised according to the author of the work, which presents a challenge when attempting to retrieve a specific piece of paper-cutting. As shown in Fig. 1, there are many categories of paper-cutting images with different images, and when a paper-cutting learner wants to copy something in a certain category, it is the fastest and most effective way to find paper-cutting works of the same category in the paper-cutting dataset for learning. This requires that we need to do the task of categorising and labelling the images in the paper-cutting database so that they can be easily searched by paper-cutting learners. Consequently, the utilisation of image classification technology to facilitate the efficient classification and generalisation of paper-cut images represents a key area of current research.

The dispersed nature of the number of artworks and the subjective nature of their content have resulted in a paucity of research into the classification of art images. The advent of digital technologies has led to the creation of a multitude of intricate artworks, underscoring the necessity for the development of effective classification algorithms. The most commonly used image classification methods are based on deep learning, such as Convolutional Neural Networks, and in particular ResNet1 networks that employ a residual block structure. This structure alleviate the gradient explosion and gradient vanishing problems and permits the construction of deeper network structures. Another recently popular approach is the Vision Transformer (VIT), which was proposed by Dosovitskiy and represents the first instance of the Transformer model being applied to image classification. VIT achieves this by segmenting the image into small chunks and encoding them as sequences, before performing the classification task using the Transformer encoder. This has proven to be an effective approach, as evidenced by its ability to surpass traditional CNN network models on multiple datasets.

Additionally, The Visual Language Grand Model offers new avenues for image classification tasks, typically employing a convolutional neural network (CNN) or a vision transformer (VIT) as an image feature extraction network and a transformer as a text feature extraction network. This approach has been trained on a large number of datasets and has achieved excellent results on various image classification datasets. Nevertheless, the effective deployment of this approach in downstream tasks remains a topic for further investigation.

In order to resolve the issue of classifying paper cutout images using the aforementioned method, it is necessary to consider a number of factors.: (1) The artistic abstraction and uniqueness of paper-cut works result in suboptimal outcomes when deep learning methods are employed to process image features for classification. (2) The distribution of existing paper-cut datasets is uneven, with a considerable range in the number of categories, from hundreds to only a few dozen. In comparison to the conventional small-sample classification, which is characterised by a restricted number of categories, the paper-cut dataset presents the challenge of encompassing a multitude of categories, with some comprising only a limited number of samples. It thus follows that the conventional methods of small-sample learning are ill-suited to addressing the classification challenges of paper-cut images. (3) The classification of paper-cut images is a challenging task due to the subjective nature of this artistic form. The creativity involved in paper-cutting often results in the generation of new categories that the model has not encountered, and it is therefore essential to consider the model’s ability to accommodate these unseen categories.

Few—shot learning and large vision—language models can effectively address the challenges faced in paper—cut classification. Where metric learning is a commonly used method in few-shot learning. The application of metric learning to small-sample image classification tasks entails the mapping of an image into a feature representation space, with the objective of determining its class membership by comparing the distance or similarity between the input image and the class prototype. The most commonly employed similarity computation methods include the Euclidean distance2, the Mahalanobis distance3, and the cosine similarity4. For instance, Matching Networks5 utilise the cosine similarity function for classification purposes, whereas Prototype Networks6 typically utilize the Euclidean distance metric to measure the relationship between the input image and the class prototype, focusing on the degree of their alignment or similarity. Furthermore, depending on the requirements of the specific task at hand, alternative distance or similarity measures, such as Manhattan7, bulldozer8, Minkowski9, or Chebyshev10 distances, can be employed.

Presently, Prototype Networks6 are widely employed due to their simplicity and ease of network use. As shown in Fig. 2, the prototype network considers that there is a class prototype for each category in the embedding space, \({c}_{1},{c}_{2},{c}_{3}\) in the figure represent the class prototype of the three categories. When a new sample is input, its feature \(X\) in the embedding space is obtained by the embedding function, and the distance (similarity) between \(X\) and \({c}_{1},{c}_{2},{c}_{3}\) is calculated to determine which category the sample belongs to, and the closer it is to the class prototype, the more it is considered to belong to that class prototype.

To enhance the performance of the prototype network, a number of researchers have made improvements to prototype networks. For example, Liu et al.11 proposed a method for correcting class prototype, while Fort et al.12 developed a Gaussian Prototypical Networks, which incorporates confidence intervals around class prototype to enhance the quality of individual data points. Ji et al.13 introduced a classification method based on an attentional mechanism and distance scaling strategy, aiming to enhance the network’s ability to explore diverse classes of information. Relational Networks14 are also a form of metric learning that does not utilise fixed class prototype. Instead, they employ convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to compute the similarity relationship between the target image and the training samples, thereby facilitating the completion of the classification task.

The primary focus of metric learning is on addressing intra- and inter-class boundary issues. The dissimilarities between datasets have a direct impact on these distances, which, in turn, influence the classification outcomes. Mocanu et al.15 put forth a normalised maximum threshold loss function with the objective of minimising intra-class distances and maximising inter-class distances. The imbalance of inter-class differences present in different classification tasks may result in the generation of biased models. Sun et al.16 proposed dynamic metric learning, with the objective of learning a scalable metric space that would accommodate visual concepts across multiple semantic scales. Cheng et al.17 sought to maximise intra-class similarity and minimise inter-class similarity by re-weighting each similarity.

The application of existing metric learning techniques is typically confined to small-sample classification tasks. However, the high computational resource requirements and time-consuming nature of these techniques present significant limitations. The dataset is notable for its extensive number of classes and the disparate distribution of instances across these classes. The prototype network in metric learning performs classification by solving for class prototype, which serves to mitigate the long-tail effect resulting from an uneven data distribution. However, the original prototype network has fixed class prototype, poor flexibility, and is mainly composed of image feature mapping with limited feature representation capability, thus offering considerable scope for improvement.

In this paper, we address these limitations by proposing enhancements to the prototype networks to increase their adaptability and feature representation capability. Our modifications are designed to better account for the characteristics of our dataset, ultimately improving the classification performance of metric learning models.

Whereas, large vision-language models have exhibited remarkably excellent performance in feature extraction and generalization capabilities. The advent of deep learning has ushered in a new era of significant advancements in computer vision, particularly in areas such as image classification, target detection, and semantic segmentation. Nevertheless, these outcomes frequently depend on the utilisation of a substantial number of datasets, each necessitating the training of a network. This inevitably results in a significant increase in the financial expenditure associated with practical applications. In this context, visual linguistic macromodelling has emerged as a prominent area of research.

By learning a substantial corpus of image-text pairs from the Internet, the trained visual language big models, such as CLIP, ALIGN (A Large-scale ImaGe and Noisy-text embedding)18, and other similar models demonstrate the potential for zero-shot learning on downstream datasets. The fundamental concept underlying these visual language models is the mapping of text and image features into a unified space, facilitating intermodal fusion and computation. The advent of the Transformer19 has been a significant catalyst for this field, initially deployed in the domain of natural language processing and subsequently extending its reach to image analysis through the emergence of the Vision Transformer (VIT)20. This has led to the development of unified processing methods for diverse image and text modalities, paving the way for the advancement of visual language macromodels. For example, the CLIP model employs a Vision Transformer as its feature extraction network. The CLIP model is comprised of two primary components: an image encoder and a text encoder. The image encoder employs two distinct approaches: one is based on the convolutional neural network framework of ResNet50, while the other is based on the VIT feature extraction network. Both of these approaches solely focus on feature extraction, and they are both based on the VIT feature extraction network. These approaches do not engage in classification. The text encoder employs the Transformer as a feature extractor for textual data. The two aforementioned components facilitate the mapping of textual and visual data into a unified vector space, thereby enabling the model to calculate the similarity between an image and a text directly, without the necessity for additional intermediate representations. The specific structure is illustrated in Fig. 3.

The subsequent research yielded numerous enhancements based on the visual language big model. In terms of cue learning, Context Optimization (CoOp), proposed by Zhou et al.21, fine-tunes the CLIP22 by learning textual cues. Condetional Context Optimization (CoCoOp), proposed by Yang et al.23, improves the model’s generalisation ability by using conditional textual cues on top of CoOp. Multi-modal Prompt Learning (MaPLe), proposed by Khattak et al.24, The optimisation of the visual and linguistic branching of the CLIP is achieved through the utilisation of a multimodal cueing framework. Unsupervised Prompt Learning (UPL)25 employs an unsupervised supervised cue learning approach to fine-tune the CLIP, while Prompting with Self-regulating Constraints (PromptSRC)26 improves cue learning through the introduction of an additional loss function. Prompt with Text (ProText)27 combines the features of cue learning and integrated learning to learn cues for LLMs using only textual data, thereby enhancing the generalisation ability of the CLIP.

The visual language macromodels of today demonstrate robust feature extraction and generalisation capabilities, largely attributable to the comprehensive nature of the training dataset. However, the considerable complexity and variability of image types demanded by different industry requirements present significant challenges for the deployment of visual language big models in downstream tasks. The training of models for current research purposes, such as cue learning, requires a significant amount of computational resources. This is necessary for the adaptation of the models to be able to perform the required downstream tasks. Consequently, one of the current difficulties is how to rapidly and effectively deploy visual language grand models in downstream tasks.

This paper presents a multimodal prototype fusion network based on the prototype network in metric learning. The network employs a CLIP pre-trained model as the feature extraction module. The incorporation of textual features into the prototype-like computation of the prototype network enables the multimodal fusion method to enhance the expressive capacity of the prototype-like. In the context of specific datasets, the Adaptive Multimodal Prototype Fusion Network (AMPFN) is employed to facilitate dynamic adjustments to the class prototype, thereby enhancing the efficacy of the classification process. In contrast, the Instant Multimodal Prototype Fusion Network does not necessitate training in order to effectively harness the capabilities of CLIP pre-trained models in downstream tasks.

In order to address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a novel multimodal prototype fusion network for the classification of paper cut images. The model is based on the concept of a prototype network in metric learning. It introduces text feature prototypical on the basis of image feature prototypical and adjusts and fuses the feature prototypical through the embedding of the image in the metric space using Cross Fusion MultiHead Attention-Net dynamically. This process ultimately yields the feature prototypical of each class. Subsequently, the classification of paper cut images is accomplished through the utilisation of the cosine similarity relationship between the features of the input image and the class prototype. In this context, the feature extraction module employs the CLIP model, which is capable of extracting pertinent features with greater efficiency. Furthermore, the utilisation of n-shots to determine the number of samples for calculating the class prototype can mitigate the impact of an uneven distribution of the number. The principal contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

In order to enhance the efficiency of the classification of paper-cut images and to improve the adaptability of the prototype network, this paper proposes the implementation of a multimodal prototype fusion network, comprising an Adaptive Multimodal Prototype Fusion Network (AMPFN) and an Instant Multimodal Prototype Fusion Network (IMPFN). The objective is to enhance the expressive capacity of the prototype by incorporating textual semantic features, thereby improving the classification efficacy of the model.

-

The CLIP is employed as a feature extractor in an adaptive multimodal prototype fusion network for the base class paper cutout dataset. This network adjusts the textual prototype and image prototype features and performs modal fusion through the features of the input images to obtain the final class prototype, thereby enhancing the expression and adaptation of the prototype. The instant multimodal prototype fusion network directly incorporates text and image prototype features through modal fusion, thereby obtaining the final class prototype. This process does not necessitate training and can be readily applied to classification tasks, including the classification of previously unseen categories.

-

The method proposed in this paper not only achieves good results on seen categories, but also shows excellent performance on the classification task of unseen categories. By utilising the CLIP pre-trained model, we save computational resources and reduce the economic cost, thus improving the effectiveness and usefulness of the model in practical applications. It offers an effective technical support system and a comprehensive theoretical framework for the classification and summarisation of paper-cutting datasets.In addition, the method provides technical support for classification tasks of other types of art images in ICH work. On PACS, ArtDL and CUB-200-2011 datasets, the model in this paper performs better compared to other classification models, which is also informative for the application of CLIP model in downstream classification tasks.

Methods

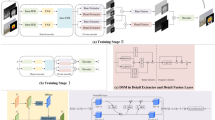

In order to address the issue of insufficient expressiveness of unimodal paper cut image-like prototypes, we propose MPFN, which is based on a model that is divided into three parts: feature extraction, model fusion and similarity computation. This section begins with an overview of the model’s overall structure and the central CFMA-Net module. It then provides a comprehensive account of the underlying principles and processes involved in feature extraction. Secondly, MPFNs are categorised as either AMPFNs or IMPFNs, depending on the specific modal fusion methodology employed. In the case of AMPFNs, the modal fusion process utilises the CFMA-Net module, which has been proposed in this paper. In order to optimise the parameters of the model, a training process is required, which consists of two distinct phases: model training and testing. This approach is applicable to the classification of paper clippings within the basic categories. In contrast, IMPFN directly fuses the features of the image and text prototypes without any training process.

Multimodal prototype fusion network

The proposed MPFN comprises three principal components, as illustrated in Fig. 4. (a) Feature extraction: The paper-cut dataset and the associated text information are subjected to feature extraction through the CLIP pre-selected concatenation model, thereby obtaining the image and text prototype features. (b) Feature fusion: The experimental paper-cut images are passed through CLIP Image Encoder, which generates feature vectors in the embedding space. The input of CFMA-Net is then adjusted by means of Cross MultiHead Attention, with the residual structure introduced in order to obtain Feature1 and Feature3. The image prototypical and text prototypical are subjected to cross multihead attention adjustments to obtain feature 3. Subsequently, the class prototype is derived through the fusion of Feature1, Feature2 and Feature3. (c) Similarity calculation: The image feature and class prototype are calculated using cosine similarity to determine the similarity relationship, and the seat prediction with the highest similarity value is output.

The model comprises three parts: a Feature extraction: The paper cut dataset and the textual information are embedded as raw CFMA-Net via the CLIP Encoder. b Feature fusion: The input to CFMA-Net is comprised of paper cut images, which are encoded using a CLIP encoder. Modal fusion is completed by CFMA-Net using techniques such as cross-multiple attention and residuals, and the resulting output is Class prototype. c Similarity calculation: The similarity relationship between the input paper cutout image and Class prototype is calculated to get the predicted category.

Feature extraction

This abstract is concerned with the feature extraction components of the model. In this paper, the image encoder and text encoder in the CLIP pre-training model are employed as feature extractors for images and text, respectively. Subsequently, the solving process and methods of Image Prototypical and Text Prototypical are described in detail.

Image prototypical

The solution process of Image Prototypical is illustrated in Fig. 5. Initially, n paper cut images are selected from each category of paper cut dataset. Subsequently, the feature vectors in the embedding space are extracted by Image Encoder in CLIP. Subsequently, the feature vectors of the images within the same category are integrated and averaged to obtain the prototypical features of the category. These prototypical features are then integrated to obtain the Image Prototypical. In practice, different numbers of images can be selected according to the distribution of the number of categories in the paper-cut dataset to solve the Image Prototypical.

The following is a definition of the paper-cut dataset for the sake of clarity. The paper-cut image dataset is divided into three subsets: a training set, a validation set, and a test set. In this paper, these subsets are denoted as follows:

where \({x}_{i},{x}_{j},{x}_{k}\) represents the ith, jth, and kth images of the training set, validation set, and test machine, respectively. Similarly, \({y}_{i},{y}_{j},{y}_{k}\) denote the corresponding category labels. The symbols \({N}_{train},{N}_{val},{N}_{test}\) indicate the number of samples in the training, validation, and test sets, respectively. Finally, \(C\) denotes the collection of labels for all categories in the experimental dataset. It should be noted that the sample classification method presented in this paper is in accordance with the traditional classification method of deep learning samples, as opposed to the classification method typically employed for small sample data. Consequently, the categories (labels) represented in \({S}_{train},{S}_{val},{S}_{test}\) are identical, with the exception of the number of image samples, which varies. Furthermore, the datasets selected for the feature extraction stage are all drawn from \({S}_{train}\) In the event that images are employed during the initial computation of class prototype, they will not be reused in the subsequent training stage.

This stage is a traditional prototype network feature extraction approach. In this paper, we utilise an embedding function, \({f}_{I-\varnothing }:{R}^{D}- > {R}^{M}\), which maps image features into a metric space (\({R}^{D}\)). This function is applied to the image\({x}_{i}\), which is represented in the \({R}^{D}\) space. The resulting value is used to calculate the image class prototype, \({{Img}}_{i}\) for each category. The calculation formula as Eq. (4):

where \({N}_{shots}\) denotes the number of samples required to compute class prototype, and \({I}_{i}\) denotes the image prototype feature corresponding to the ith category, while \({S}^{shots}\) represents the set of samples chosen for this purpose. In contrast to the conventional prototype network, this paper employs the image encoder of the CLIP pre-trained model as the feature extractor. This approach eliminates the necessity for training and enables direct utilisation for feature extraction.

Text prototypical

In the categorisation task, each category is represented by a piece of textual information. In order to enhance the adaptation to the paper-cut dataset, the prompt text for the paper-cut category, ‘This is a paper-cut image of a [Class]’, has been designed with reference to the phrase model provided by CLIP, as shown in Fig. 6. The aforementioned prompt text is employed for the generation of textual information pertaining to each category. Subsequently, the Text Encoder in CLIP is employed as a feature extractor, with the extracted features serving as text feature prototypes for the category in question. These prototypes are then integrated to generate the Text Prototypical for the entire category.

At this stage, an embedding function is employed for the purpose of mapping the textual information into the embedding space, represented by the function \({f}_{T-\varnothing }:{T}^{D}- > {T}^{M}\). In this context, \({T}^{D}\) denotes the set of original text information pertaining to a given category, whereas \({T}^{M}\) denotes the set of vector features representing the aforementioned text information within the embedding space. The calculation formula as Eq. (5):

where \({y}_{i}\) denotes the textual cue corresponding to the ith paper cut category and \({T}_{i}\) denotes the textual prototype feature corresponding to the ith category.

Adaptive multimodal prototype fusion network

In the case of AMPFN, the feature fusion method selected was CFMA-Net. The fundamental component of the module is illustrated in Fig. 3b. This summary provides a comprehensive account of the underlying principles of CFMA-Net, followed by an exposition of the training and testing procedures employed for the model.

Cross fusion multihead attention network

The principal function of CFMA-Net is to adaptively de-adapt the class prototype based on the input paper cutout image. First, the textual prototype features and visual prototype features undergo initial feature fusion through cross-attention and scaled residuals to obtain the preliminary class prototype \({F}_{p}\). The formulate as follows:

where \({P}_{I}=\{{I}_{i}|i=[1,n]\}\) denotes Image Prototypical, and \({P}_{T}=\{{T}_{i}|i=[1,n]\}\) denotes Text Prototypical. while \(\alpha\)(where \(\alpha \in (0,1)\)) is the residual scaling coefficient. Subsequently, the preliminary class prototype \({F}_{P}\) is refined by leveraging the input image features, yielding the final class prototype \(P\).

where P denotes Class prototype, and \(\beta\) (where\(\beta \in (0,1)\)) is the residual scaling coefficient, while \(I\) denotes feature vector of the input image.

Training process

The model training process is illustrated in Fig. 7. The input image is extracted from Image Features by the image encoder of CLIP, and then the class prototype is obtained by CMFA-Net. The similarity matrix is calculated by determining the degree of similarity between the image features and the class prototype. The highest similarity score in each column is identified, and the corresponding category is used as the prediction result. Subsequently, the loss function is calculated with the true values through the cross-entropy loss function. Thereafter, the parameters of CMFA-Net are updated by backpropagation.

Subsequently, the input image is subjected to feature extraction, after which it is assigned its own dynamic class prototype through the utilisation of CMFA-Net. Subsequently, the similarity relation is calculated with the class prototype to derive the predicted categories. Thereafter, the loss function is calculated with the real categories to update the parameters of CMFA-Net.

In this, the similarity matrix is calculated by using the cosine similarity function as Eq. (8) and Eq.(9):

where \(Sim(i)\) is the maximum value of the similarity calculated between the image and text features, a predicted class for the image is ultimately obtained.Subsequently, the loss function is calculated using the prediction (\({y{\prime} }_{i},(i\in [1,N])\)) and the true category (\({y}_{i},(i\in [1,N])\)) in order to update the model parameters.

The loss function chosen is the cross-entropy loss function as in Eq. (10):

Model testing

The models that have undergone training during the training phase are employed for the purpose of evaluating the classification task with respect to the paper cut test set. The data in the test set \({S}_{test}\) is employed for feature extraction utilising the image encoder of the CLIP pre-trained model to obtain the image feature. Subsequently, it is utilised to derive the class prototype through CFMA-Net, and the similarity relationship is calculated between the image feature and the class prototype. The prediction result is determined by identifying the class prototype with the largest value of similarity. The specific steps are illustrated in Fig. 8.

The image of the paper cut is subjected to processing in the Image Encoder of CLIP, resulting in the generation of a feature vector within the embedding space. Subsequently, the class prototype is obtained by CFMA-Net, after which the similarity relation is calculated between the feature vector of the input image and the class prototype in order to obtain the prediction result.

Instant multimodal prototype fusion network

Figure 9 illustrates the Instant Multimodal Prototype Fusion Network. The most notable aspect of this approach is that it does not necessitate any training, and the overall process is divided into two phases: feature extraction and model application. The feature extraction process is analogous to that employed by AMPFN. This involves the extraction of features, the generation of image and text class prototype, and the formation of image and text class prototype, respectively. Subsequently, the two class prototype are merged to create the final class prototype. The module is based on the CLIP, which serves as a feature extractor. This model can be directly applied to the classification task without the need for training, through data preprocessing (solving of class prototype). The input image is subjected to feature extraction by the Image Encoder, which obtains the feature vectors of the image in the embedding space. Subsequently, the similarity is calculated with the obtained class prototype, and the category with the highest similarity score is used as the final classification result.

Once the text and image prototypical have been obtained, the two are directly fused to create class prototype. Once the image has been extracted using CLIP features, the similarity is calculated with the class prototype, thereby obtaining the classification result. This method allows for the efficient classification of previously unseen classes, thus complementing the experimental dataset.

In the context of paper cut data with previously unseen categories, only a limited amount of dataset labelling can be directly applied to the classification of image and text class prototype. This is due to the fact that the number of categories involved is relatively small. This process allows for the efficient preliminary classification of new categories, reducing the time required for data labelling and providing a sufficient training dataset for AMPFN, which enables further refinement of the model’s ability to classify seen categories.

Results

The experiments presented in this paper are divided into two distinct categories: those conducted on the paper cut dataset and those conducted on the open dataset. The objective of this paper is to enhance the efficacy of image classification in the context of paper cutout images. To this end, two experiments are conducted on the paper cutout dataset, namely, the classification of seen classes and the classification of unseen classes. Subsequently, experiments are conducted on public datasets, including PCAS28, ArtDL29 and CUB-200-2011, with the objective of verifying the robustness of the proposed method.

Experiments datasets

The paper cut dataset was primarily collected through manual means, with the network comprising 2500 sheets divided into 27 categories. The distribution of images within each category is not uniform, with a maximum of 188 sheets and a minimum of 25 sheets per category. The paper cut dataset is characterised by a high number of categories and a relatively low amount of sample data. The application of traditional deep learning in this context may result in a model exhibiting a bias towards categories with a greater quantity of data. Conversely, traditional small sample learning is typically employed in research contexts involving a limited number of categories and quantities. The utilisation of small sample learning in this case may result in the inefficient utilisation of existing image resources. In light of the aforementioned considerations, this paper opts to utilise the prototype network as the foundational network, which is capable of adapting the class prototype in accordance with the varying sample sizes to achieve optimal results. In the experiment, categories with fewer than 50 samples were augmented to 50 through operations such as flipping and rotation. In accordance with the aforementioned dataset division in the context of the small sample classification task, this paper proceeds to divide the paper cut dataset into a training set (support set) and a test set (query set). The training set comprises 14 classes, while the test set comprises 13 classes. The specific division information is presented in Table 1(The visualization only shows the original dataset distribution before augmentation).

This paper focuses on three public datasets: PACS, ArtDL and CUB-200-2011. The PACS dataset is a domain-adaptive image dataset. It encompasses four distinct domains: photographs, art paintings, cartoons, and sketches. Each domain contains seven categories. Given the artistic abstraction of the images, we have selected the art painting and sketch domains as our experimental data. ArtDL is a novel painting dataset for image classification. The majority of the paintings originate from the Renaissance period and depict scenes or figures from Christian art. The ArtDL dataset was created in 2020 by an internationally renowned research centre for art and technology, with the aim of promoting the integration of digital art and deep learning technologies. The core research questions revolve around how to utilize deep learning techniques for the classification, style transfer, and generation of digital artworks. The CUB-200-2011 dataset is a bird image dataset, encompassing 200 categories and a total of 11,788 images. The specific division is illustrated in Table 2.

Network structure and parameter settings

The modal prototype fusion network is comprised of four principal components: the feature extraction module, the CFMA-Net module, the similarity calculation module and the loss function calculation module. The feature extraction module employs the Image Encode and Text Encode functions derived from the CLIP pre-training model. The similarity calculation module employs the cosine similarity function, while the loss function utilises the cross-entropy loss function.

In order to enhance the extraction of image features, the image feature extraction network employs the Image Encode module from the CLIP pre-training model. This module primarily utilises the network architecture of ResNet and the VIT series, including ResNet50, ResNet101, and the extended ResNet50×4 and ResNet50×16. The ViT series comprises two variants: VIT-B/16 and VIT-B/32. The text feature extraction network employs the Text Encode module from the CLIP, which is based on the Transformer structure.

In order to ascertain the efficacy of disparate image feature extraction modules, experimental validation is conducted in this paper on the paper cutout dataset. The network employed is the adaptive multimodal prototype fusion network, and the similarity function is the cosine similarity calculation function. The specific results are presented in Table 3. It can be observed that the VIT-B/16 model demonstrates optimal performance in the 1-shot, 5-shot, and 16-shot experiments. Consequently, this study selects the VIT-B/16 model as the image feature extraction module for CLIP.

The selection of the similarity (distance) calculation function is also a significant factor that impacts the performance of the model. The most commonly utilised similarity (distance) calculation functions in metric learning are the Cosine Similarity function, the Euclidean Distance function and the Mahalonobis Distance function. In this paper, experimental comparisons were conducted on the paper cut image dataset using the three methods, and the specific results are presented in Table 4. It can be observed that the overall performance of the cosine similarity function is the most optimal, and thus, it has been selected as the similarity calculation algorithm in this paper.

In this paper, all experiments are evaluated using classification accuracy, with the results of three experiments averaged to provide a comparison. Our method’s trainable parameters are approximately 0.78 M. The batch size is set to 16. The training epoch is 100. Furthermore, in regard to the configuration of parameters, Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) is selected as the optimiser. The learning rate is determined through experimentation and set to 1e–5. During training, the image size is proportionally adjusted to 224 × 224. The normalization process adheres to the same requirements as CLIP for images, with the mean and standard deviation values for the RGB channels being: (0.48145466, 0.4578275, 0.40821073) and (0.26862954, 0.26130258, 0.27577711), respectively.

Paper-cut image classification experiment

The experiments utilising paper-cut images are primarily categorised into two distinct groups: those pertaining to the classification of the observed category and those pertaining to the classification of the unobserved category. The model that is to be trained is that which has been trained on the observed category dataset and is then applied directly to the unobserved category. In this paper, we select two algorithms for comparison: one based on metric learning and the other based on the CLIP model. To ensure fairness, we also choose the Image_Encode module in CLIP for the image feature extraction module in metric learning.

In order to address the issue of data imbalance and the limited number of samples in some categories, this study employs a data sampling approach, whereby a small number of data points are selected from each category for experimentation. The term “n-shot” refers to the selection of n images from each category for computing class prototype and training the network. These images are excluded from the training of the model’s computational class prototype. The experimental results are presented below.

Regarding the classification of base classes, the specific experimental results are shown in Table 5. The results indicate that AMPFN demonstrates the optimal performance in 1-shot, 5-shot, and 16-shot scenarios, and the accuracy increases as the number of samples increases. This is because the AMPFN and IMPFN proposed in this paper exhibit a certain degree of dependence on the quantity of the dataset. The larger the number of experimental data, the stronger the representation ability of the class prototype, and thus the better the classification effect.

Regarding the classification of unseen classes, the specific experimental effects are presented in Table 6. In the 1-shot, 5-shot, and 16-shot scenarios, IMPFN shows the most excellent performance. This suggests that when applied to unseen classes, AMPFN has a poorer performance compared to IMPFN, while IMPFN has a broader applicability. The performance of IMPFN on seen classes is similar to that of AMPFN. Moreover, IMPFN does not require training. It only needs to obtain the class prototype through prior conditions and can then be applied to classification tasks.

A detailed examination of the experimental outcomes reveals that the two multimodal cue learning approaches based on the CLIP pre-training model of Coop and CoCoop, due to the high level of abstraction inherent in paper-cut images, which differs from the conventional image content format, exhibits a comparatively weaker correlation with the corresponding text content. This, in turn, results in a suboptimal outcome with regard to the classification based on the text-image similarity. Similarly, the CLIP Zero-Shot approach encounters the same issue, and it also has a fixed upper performance limit. Furthermore, the cost of fine-tuning is prohibitively high, and the improvement effect is limited for datasets with poor classification performance. CLIP+Linear can be regarded as a traditional deep learning model that solely relies on image content for classification. It is highly dependent on the amount of data and exhibits a robust performance in classifying seen classes but a suboptimal performance in migrating unseen classes. The Prototypical Network and Matching Network, however, only select image features as the solution object of the class prototype, which results in an inadequate representation of the class prototype and, consequently, an adverse effect on the classification outcome.

The experimental results demonstrated that, with regard to the paper cutout dataset, AMPFN exhibited superior performance for the seen classes, while IMPFN demonstrated enhanced efficacy for the unseen classes. Furthermore, the model has a reduced number of parameters, necessitates less computational resources, and can be rapidly reproduced on the majority of devices. The superiority of the model proposed in this paper for classifying abstract data images such as paper cuttings is verified through experimentation, which proves that the method proposed in this paper is feasible.

Public dataset image classification experiments

In order to further verify the generalisation of the method presented in this paper, experiments were conducted using the public datasets PACS (art painting and sketch) and ArtDL. These experiments employed a 5-shot and 16-shot classification approach, with the datasets divided into two categories: classification on Base Classes and Unseen Classes. The results of the experiments are presented below.

An analysis of Table 7 indicates that for the PACS dataset, the abstract nature of image content, combined with a limited number of categories and significant inter-class differences, allows the CLIP Zero-shot method to achieve high accuracy without training. However, under the 5-shot and 16-shot conditions, the AMPFN method demonstrates superior performance after model training. Compared to the Prototypical Network, which solely utilizes image features for class prototypes, both AMPFN and IMPFN show significant improvements in accuracy. This highlights that the use of multimodal prototypes enhances the expressiveness of class prototypes, thereby improving classification performance.

Analysis of the experimental data in Table 8 shows that in the ArtDL dataset, the abstract nature of artistic content and the strong modality differences between images and text categories (which are named after persons) negatively affect CLIP Zero-shot performance. While Coop and CoCoop enhance model performance through prompt learning to optimize text inputs, their improvements are limited. AMPFN achieves the best results in both 5-shot and 16-shot conditions, even surpassing Coop’s 16-shot performance in the 5-shot scenario. IMPFN also demonstrates high performance. This indicates that MPFN excels in handling datasets with abstract content and significant image-text differences. The complexity of such datasets demands stronger model generalization and feature expression. By innovatively integrating multimodal information to enhance class prototype expressiveness, the MPFN series achieves remarkable performance improvements in classification tasks. These results validate the applicability and effectiveness of our method for challenging datasets and support its potential for real-world applications.

Public dataset generalization from base to new classes

An analysis of the experimental results in Table 9 shows that, for the PACS (art painting) dataset, AMPFN and IMPFN achieved the best performance in the 5-shot and 16-shot settings, respectively. For the PACS (sketch) dataset, IMPFN performed best in both settings. These results demonstrate that the AMPFN and IMPFN proposed in this paper maintain a certain advantage in generalizing to unseen classes. Additionally, PACS validation on new classes involves only three categories with significant inter-class differences, making classification relatively easier, yet the results still highlight the superior performance of MPFN.

From the experimental results in Table 10, it can be seen that AMPFN achieved the best performance in both 5-shot and 16-shot settings for the new classes in the ArtDL dataset. This further highlights the high performance of the MPFN series in classifying abstract art datasets. Overall, these results validate the effectiveness of our proposed methods in handling challenging classification tasks.

Fine-grained image classification

The aforementioned experiments serve to validate the efficacy of our model in the context of common datasets. Furthermore, the subjective and abstract nature of paper-cut image works gives rise to the additional issue of inter-class variability in paper-cut images. As illustrated in Fig. 10, the variability of paper-cut images between cats and dogs is minimal in both sets (a) and (b), with the shapes exhibiting notable similarity. This has implications for the classification of paper-cut images. As the number of people engaged with paper-cutting increases, it is likely that there will be a corresponding rise in the number of paper-cutting works produced. This will, in turn, give rise to the need to consider the problem of further detailed classification of paper-cutting images. To illustrate, if the two images of birds in Fig. 10 were to be classified in a more refined manner, the images in group (a) would be classified as belonging to swallows, while the images in group (b) would be classified as belonging to pigeons. This necessitates the consideration of the fine-grained image classification issue, given the considerable inter-class similarity.

The number of datasets utilising paper cutting for this problem is limited, therefore the publicly available dataset CUB_200_2011 was selected for evaluation purposes. This dataset represents the current benchmark for fine-grained classification and recognition research, comprising 200 classes of bird images with minimal inter-class distinctions. The results of the experiments are presented in Tables 11, 12.

Analyzing the experimental results in Tables 11, 12, we observe that IMPFN and AMPFN achieve the best performance under 5-shot and 16-shot conditions respectively for seen categories. Similarly, IMPFN and AMPFN demonstrate optimal performance under 5-shot and 16-shot conditions for unseen categories. Notably, CLIP Zero-shot exhibits relatively poor performance compared to the Prototypical Network, which achieves satisfactory results. This suggests that in the CUB_200_2011 dataset, there exists a significant discrepancy between image features and category textual descriptions for CLIP models, where class prototypes are substantially influenced by image features. Remarkably, the Coop method attains 80.56% accuracy under 16-shot conditions for seen categories, merely 0.02% lower than the top-performing AMPFN. This indicates that through model training, textual class prototypes can be effectively aligned with image features. The superior performance of both Coop and Prototypical Network demonstrates the exceptional feature representation capabilities inherent in both textual and visual class prototypes. Our proposed MPFN series, which integrates these dual modalities, achieves state-of-the-art experimental results and demonstrates enhanced performance. The outstanding performance on the CUB_200_2011 dataset validates our model’s robust capability in handling challenges involving high inter-class similarity.

The MPFN series model proposed in this paper demonstrated superior performance in experiments on the abstract PACS and ArtDL datasets. Additionally, it showed strong ability to handle high inter-class similarity on the fine-grained classification dataset CUB_200_2011. These experiments validate the effectiveness and superiority of the MPFN series. In conclusion, for datasets that are more unique and abstract, such as paper cuttings, AMPFN is more effective on seen classes, while IMPFN is more suitable for unseen classes. AMPFN requires data for model training, while IMPFN requires no training and can be directly applied to downstream classification tasks after obtaining class prototype by a priori conditions, which is highly applicable. In comparison to the CLIP-based zero-shot approach, IMPFN demonstrates enhanced model performance and classification efficacy with an increase in the quantity of data, establishing a benchmark for the deployment of CLIP models in downstream tasks.

Ablation study

The proposed AMPFN in this paper primarily consists of three modules: the fusion module for image and textual class prototypes, the fusion module for input images and preliminary class prototypes, and the residual module. To evaluate the effectiveness of each module, experimental studies were conducted on the Paper-Cut dataset. The experimental results, presented in Table 13, are based on three module combinations: Scenario 1: Without the residual structure. Scenario 2: Without fusing input images with preliminary class prototypes. Scenario 3: Using all modules in combination.

An analysis of the experimental results in Table 13 shows that in Scenario 1, the residual structure is crucial for enhancing model performance by alleviating gradient vanishing and enabling more effective learning of deep features. A comparison between Scenario 2 and Scenario 3 reveals that fusing input images with preliminary class prototypes significantly boosts performance, likely due to the complementary information between image features and class prototypes. Finally, the results of Scenario 3 demonstrate that combining all modules achieves the best performance, highlighting the rational design of the AMPFN model and the synergistic collaboration of its modules in enhancing classification capabilities.

In this paper, a proportional residual connection strategy is employed during feature fusion. The residual proportion is treated as a trainable hyperparameter, allowing its magnitude to be adjusted during model training. However, different initializations of the residual proportion can impact the final model performance. Therefore, this paper discusses the initialization of the residual proportion and conducts experimental analyses, with the results presented in Table 14. This approach is crucial for performance enhancement, as it helps mitigate gradient vanishing and enables more effective learning of deep features. The experimental results demonstrate the impact of varying residual proportion initializations on model outcomes.

Analysis of the experimental results shows that a residual proportion of 0.2 allows the model to achieve the highest accuracy on the paper-cut dataset. Adjusting the residual proportion significantly impacts model performance, especially with limited samples. Thus, selecting an appropriate residual proportion is crucial for enhancing model performance in practical applications.

Discussion

This paper proposes a multimodal prototype fusion network classification model (MPFN) for the problem of classifying paper-cut images. The model is divided into two types according to the situation: an adaptive multimodal prototype fusion network (AMPFN) and an immediate multimodal prototype fusion network (IMPFN). Both enhance the representation of prototypical by introducing textual semantic features. However, there is a distinction between the two models in terms of their approach to feature integration. The AMPFN employs the feature information of the input image to dynamically adaptively adjust and fuse image-like and text-like prototypical during training, thereby obtaining the final class prototype. In contrast, the IMPFN directly performs modal fusion of text-like prototypical and image-like prototypical without training, thereby obtaining the final class prototype. The experimental results demonstrate that the AMPFN model exhibits superior performance in classifying seen classes, while the IMPFN model demonstrates superior performance in classifying unseen classes. The proposed model demonstrates robust classification capabilities across a range of tasks on the paper cut dataset. Consequently, in practical applications, IMPFN can be employed to perform preliminary classification of novel paper-cut image categories with a limited amount of labelled data, thereby facilitating sufficient experimental data for AMPFN to enhance its classification performance.

The limitation of this study is that the cue text is fixed. The potential for adapting different cue texts to suit different classification tasks is not addressed in this paper. Furthermore, IMPFN is unable to achieve zero-shot learning, as it requires samples of each category to calculate the class prototypes. The greater the number of samples, the more expressive the class prototypes become, thereby improving the classification effect. To address these issues, future work will focus on enhancing the classification performance of the model by identifying more appropriate textual cues through cue learning. Additionally, the related unsupervised classification algorithm will be employed to initially classify the unseen class of the paper cut dataset, providing samples for IMPFN to compute class prototypes.

Data availability

For information regarding the paper-cut dataset, please contact cdlin@xauat.edu.cn. The PACS datasets at the following link: https://paperswithcode.com/dataset/pacs; the ArtDL datasets at the following link: https://artdl.org/; the CUB-200-2011 datasets at the following link: https://www.vision.caltech.edu/datasets/.

References

He K., Zhang X., Ren S.& Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Las Vegas, NV, USA: 2016:770–778.

L, Wang., Y, Zhang. & J. Feng. On the Euclidean distance of images, in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 27, 1334-1339, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2005.165

De Maesschalck, R., Jouan-Rimbaud, D. & Massart, D. L. The Mahalanobis distance. Chemometrics Intell. Lab. Syst. 50, 1–18 (2000).

Salton, G., Wong, A. & Yang, C. S. A vector space model for automatic indexing. Commun. ACM 18, 613–620 (1975).

Vinyals O., Blundell C., Lillicrap T., Kavukcuoglu K.& Wierstra D. Matching networks for one shot learning. arXiv:1606.04080; 2016. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1606.04080.

J. Snell, K.& Swersky, R. Zeml Prototypical networks for few-shot learning. Proceedings of the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS). Long Beach, USA, 2017: 4077-4087.

Li, J. & Allinson, N. M. Relevance feedback in content-based image retrieval: A review. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci 7736, 185–196 (2013).

A. Andoni, K. D. Ba. & P. Indyk and D. Woodruff. Efficient sketches for earth-mover distance, with applications, 2009 50th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009,324-330, https://doi.org/10.1109/FOCS.2009.25.

Earth, A., Lochl, M. & Axhusen, K. W. Graph-theoretical analysis of the Swiss road and railway networks over time. Netw. Spat. Econ. 7, 1–19 (2007).

Xiang, S., Nie, F. & Zhang, C. Learning a Mahalanobis distance metric for data clustering and classification. Pattern Recognit. 41, 3600–3612 (2008).

Li, X. et al. BSNet: Bi - Similarity network for Few - shot Fine - grained Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process 30, 1318–1331 (2021).

Fort S. Gaussian Prototypical Networks for Few-Shot Learning on Omniglot. ArXiv abs/1708.02735, 2017(2017-08-09).

Ji, Z., Chai, X., Yu, Y., Pang, Y. & Zhang, Z. Improved prototypical networks for few-Shot learning. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 140, 81–87 (2020).

Sung F. et al. Learning to compare: Relation network for few-shot learning. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Salt Lake City, UT, USA: 2018:1199–1208.

B. Mocanu, R. Tapu & T. Zaharia. 2023. Multimodal emotion recognition using cross modal audio-video fusion with attention and deep metric learning. Image Vision Comput. 133, C (May 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2023.104676.

Sun Y. et al. Dynamic metric learning: Towards a scalable metric space to accommodate multiple semantic scales. Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Piscataway: IEEE, 2021: 5393-5402.

Sun Y. et al. Circle Loss: A unified perspective of pair similarity optimization, 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 2020, 6397-6406, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00643.

Jia C. et al. Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision [EB/OL]. ArXiv abs/2102.05918, 2021.

Vaswani A. et al. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv:1706.03762 (2017).

Dosovitskiy A. et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. ArXiv abs/2010.11929, 2020.

Zhou K., Yang J., Loy C. C., Liu Z. Learning to prompt for vision-language models. arXiv:2109.01134, (2021).

Radford A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. arXiv:2103.00020, 2021.

Zhou K., Yang J., Loy C. C.& Liu Z. Conditional prompt learning for vision - language models. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). New Orleans, LA, USA: 2022:16795–16804.

Khattak M. U., Rasheed H., Maaz M., Khan S.& Khan F. S. MaPLe: Multi-modal prompt learning. 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023, 19113-19122.

Huang T., Chu J.& Wei F. Unsupervised prompt learning for vision-language models. ArXiv abs/2204.03649, 2022.

Khattak M. U. et al. Self-regulating prompts: Foundational model adaptation without forgetting. 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2023.

Khattak M. U., Naeem M. F., Naseer M., Gool L. V.& Tombari faderico. Learning to prompt with text only supervision for vision-language models. ArXiv abs/2401.02418, (2024).

Li D., Yang Y., Song Y.& Hospedales T. M. Deeper, broader and artier domain generalization. Proc IEEE Int Conf Comput Vis (ICCV). 2017;5543–5551.

Milani, F. & Fraternali, P. A dataset and a convolutional model for iconography classification in paintings. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 14, 1–18 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shaanxi Province Key Industry Innovation Chain (Cluster) - Industrial Field Project (No. 2022ZDLGY06-04), the Nature Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2025JC-YBMS-1100) and the Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2024R055).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - review & editing; D.C. Software, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization; Y.Q. Data curation, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Chen, D. & Qin, Y. Multimodal prototype fusion network for paper-cut image classification. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 462 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02036-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02036-8

This article is cited by

-

A deep learning-based method for identifying traditional villages across cultural types

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Application of Huangling mianhua image recognition and classification system based on deep learning

Discover Computing (2025)