Abstract

Cave 55 of Mogao Grottoes, which was excavated in the early Northern Song Dynasty and renovated during Western Xia, has murals richly adorned with gold foil. A systematic analysis was carried out on the gilding materials and techniques in Cave 55, including optical microscope observation (OM), scanning electron microscope with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), X-ray diffractometer (XRD), confocal Raman microscopy (CRM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), pyrolysis with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS). Analysis revealed significant differences in the materials used for gilding application between the murals of the Northern Song Dynasty and those of the Western Xia and the gold foil used in the Mogao Grottoes during the Cao Family Guiyi Circuit period likely originated from tribute and rewards given by the Central Plains Dynasty. The findings can serve as a reference for gilding research of other caves at Mogao Grottoes and grottoes along the Silk Road.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

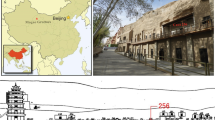

The Mogao Grottoes (莫高窟), inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1987, is located 25 km southeast of Dunhuang City (敦煌市), Gansu Province, China1. Dunhuang, situated at the westernmost tip of the Hexi Corridor (河西走廊), was a crucial hub on the ancient Silk Road. The Mogao Grottoes comprises 492 decorated Buddhist caves, over 2000 polychrome sculptures, and approximately 45,000 m2 of splendid murals, excavated into a vertical cliff about 1680 m long east of Mingsha Mountain (鸣沙山) from the 4th to the 14th century2,3. The Mogao Grottoes are the largest and best-preserved Buddhist grotto temple site in the world4. It serves as an important witness to cultural exchange and integration between China and the West, providing visual information on politics, economy, history, religion, architecture, science, and technology across different periods. Cave 55, which is one of the best-preserved Buddhist grottoes from the Northern Song Dynasty (宋, 960-1127 CE), is located in the middle of the south district of the Mogao Grottoes (Fig. 1). The cave has an inverted funnel-shaped roof, consisting of entrance corridor and a main chamber with 10 polychrome sculptures on the central Buddhist altar and a background screen connecting the top of the cave in the west. During the Western Xia period (西夏, 1038-1227 CE), the murals in the entrance corridor and some murals under the east, south, and north walls of the main chamber were repainted.

a Nine-Storey Pagoda: the landmark building of the Mogao Grottoes. b Section and floor plan of Cave 55: The upper image shows a longitudinal section, while the lower image presents the floor plan, highlighting the spatial organization. Scale bar: 0–2 m. c Interior scene of Cave 55: it showcases key features such as the caisson ceiling, ceiling slope, entrance corridor, background screen, and main chamber with polychrome sculptural artifacts. d Local orthophoto of the southern area of Mogao Grottoes: it illustrates the geographical context and precise location of Cave 55 within the broader site.

According to the inscription of the fourth donor on the bottom mural of the south wall of the entrance corridor, scholars have determined that the grotto was constructed between 962 and 964 CE, dedicated to commemorating the deeds of Cao Yuanzhong (曹元忠), the fourth commander general of the Cao family Guiyi Circuit (曹氏归义军, 914-1036 CE)5. The Cao family Guiyi Circuit (914-1036 CE) refers to the period during which Cao Yijin (曹议金) and his descendants controlled Guazhou (瓜州) and Shazhou (沙州), spanning from the Five Dynasties (五代, 907-960 CE) to the early Northern Song Dynasty. The Cao family Guiyi Circuit was a distinctive local regime in Dunhuang’s history. During this period, the Cao family military governor and their family members, serving as the primary sponsors, initiated a new and unprecedented pattern in the construction of Dunhuang grottos, represented by the building of large grottoes. Through the efforts of Cao Yijin, Cao Yuande (曹元德), and Cao Yuanshen (曹元深), the political situation under Cao Yuanzhong stabilized, and Buddhist activities flourished. Cave 55 represents the grotto construction activities of the supreme rulers under the dual influence of politics and religion. It is an important resource for the study of Dunhuang grotto art, polychrome sculpture art, and mural techniques.

The murals of Mogao Grottoes are famous for their vibrant colors, and gold is used to add splendor when colors are insufficient. Gold foil decorations are found on murals from the Sixteen Kingdoms period (十六国, 304-439 CE) to the Yuan Dynasty (元, 1271-1368 CE). Similarly, polychrome sculptures are often embellished with gold, accentuating their gravity and magnificence. Currently, few studies focus on gilding in the Mogao Grottoes. There is a lack of comprehensive examination of the gilding techniques and materials employed across various periods, as well as scientific analysis of the techniques and materials. The murals and polychrome sculptures in Cave 55 are predominantly adorned with gold foil, making them invaluable resources for studying the gilding techniques of the Northern Song Dynasty and Western Xia.

The ancient texts Tiangong Kaiwu (《天工开物》) and Huishi Suoyan (《绘事琐言》) document the techniques for producing gold foil. During the Ming Dynasty (明, 1368-1644 CE) and Qing dynasties (清代, 1636-1912 CE), gold foil was further classified into various types6. In the Song Dynasty work Yingzao Fashi (《营造法式》), five methods of applying gold in architectural paintings are described. However, no systematic framework was established for these methods, presumably because of the multiple bans on gold usage imposed during the Northern Song Dynasty. Corresponding textual research and studies have been undertaken on these five gold application techniques7. With the development of modern technology, numerous advanced analytical methods have been widely applied in cultural relics and heritage research. These methods deepen our understanding of the historical information pertaining to the craftsmanship and materials of cultural relics and provide crucial scientific evidence for their conservation and restoration. In studying gilding techniques used in murals, painted sculptures, and architectural paintings, various analytical methods are employed, including optical microscopy (OM)8, X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF)9,10, X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD)11, scanning electron microscope with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)12,13, pyrolysis with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS)14, Raman spectroscopy (RS)12, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)15,16, liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization combined with mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS)17, ultraviolet fluorescence microscopy18, and imaging spectroscopy (IS)19, etc.

This paper aims to investigate the gilding decorations in the murals of Cave 55, Mogao Grottoes. Multiple analytical methods, including OM, SEM-EDS, XRD, confocal Raman microscopy (CRM), FTIR, Py-GC/MS were used to systematically reveal the materials and techniques of gilding. Based on the analytical results and ancient literature, comparative studies were conducted on the gilding techniques utilized in murals from the Northern Song Dynasty and Western Xia, as well as investigations into the origins of the gold foils. The research findings can serve as a reference for studying gold leaf application in other caves of Mogao Grottoes and grotto temples along the Silk Road. They provide scientific support for the future conservation of gilding decoration and contribute to the inheritance and promotion of traditional gilding techniques.

Methods

Samples

There are three types of gilding decorations in Cave 55: gilding on plane mural, gilding on raised line, and gilding on relief. As detailed in Table 1, GF-1 to GF-6 are gold foil samples, while C55-1 to C55-6 are gilding samples using different techniques from the Northern Song Dynasty and Western Xia. The specific sampling locations and surface microscope images of each sample are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. C55-1 shows that the surface of the gold leaf is incomplete, with a gray raised line exposed below; C55-2 displays black and brownish-red below the gold foil; C55-3 exhibits red pigment below the gold foil; C55-4 has an obvious gold foil texture with green underneath; C55-5 and C55-6 present a darker appearance in the gilding area, with gray raised lines visible below the gold foil. Based on the preliminary morphological characteristics observed through optical microscopy, subsequent analyses adopted a multi-instrument approach to determine the layer information and substance composition of each layer. Material analysis includes both inorganic and organic materials utilized in the gilding of Cave 55.

The figure displays a series of images illustrating the sampling locations on the original artifacts (left column) and corresponding surface microscope images (right column, labeled GF-1 to GF-6) of collected gold foil samples. In the left column, red arrows indicate the precise locations from which gold foil samples were extracted. The background shows the intricate artwork and context of the Mogao Grottoes murals. The right column presents high-magnification microscope images of each gold foil sample, showcasing their surface texture, morphology, and any visible features. A scale bar of 200.00 µm is provided for each microscope image to indicate the size and level of detail.

The figure displays a series of images illustrating the sampling locations on the original artifacts (left column) and corresponding surface microscope images (right column, labeled C55-1 to C55-6) of collected blocky samples. In the left column, red arrows indicate the precise locations from which blocky samples were extracted. The background shows the intricate artwork and context of the Mogao Grottoes murals. The right column presents high-magnification microscope images of each blocky sample, showcasing their surface texture, morphology, and any visible features. Each microscope image includes a scale bar (either 200.00 µm or 500.00 µm) to indicate the magnification level and the size of the observed features.

Analysis methods

Optical microscope observation (OM): The samples were observed using a Keyence VHX-600E digital-microscope with a VH-Z20R objective, allowing magnification from 20× to 200×. After obtaining the surface morphological characteristics, the samples were embedded using EpoThinTM2 epoxy resin and curing agent from Struers. Once the resin was completely cured, the samples were ground and polished until the cross-section surface was specular smooth. The sample cross-sections were observed using a Leica-DMLP polarizing microscope, equipped with a 10x eyepiece, a field of view (FOV) ranging from 22 mm to 25 mm, and illuminated by a 12 V 100 W halogen lamp for transmitted and reflected light.

Scanning electron microscope with energy dispersive spectroscopy analysis (SEM-EDS): (1) SEM-EDS analysis for the blocky gilded samples of cross-sections was conducted using a JEOL JSM-6610LV SEM equipped with an INCA X-ACT energy dispersive spectrum. The SEM images were taken in a low vacuum environment, in back scattering mode, with a working distance of 12 cm and a scanning voltage of 15 kV. (2) A Thermo Fisher Scientific Helios G4 UC scanning electron microscope focused ion dual beam system coupled with an Oxford instruments X-MaX 80 energy dispersive spectrometer was used to analyze the microstructure, thickness, and relative concentration of major elements in gold foil samples. Analysis was conducted in a low vacuum environment, with a working distance is 4 mm–8 mm. Clear microscopic photos were obtained under a voltage of 5 kV and current of 0.4 nA. Energy spectrum analysis was carried out under a voltage of 20 kV and current of 0.8 nA.

X-ray diffractometer analysis (XRD): A Rigaku Dmax/2500 diffractometer was used to analyze the phase composition of pigment samples and soil samples. The testing conditions were as follows: tube voltage of 40 KV, tube current of 100 mA, using continuous scanning with a scan range of 5–70°.

Confocal Raman microscopy (CRM): The confocal Raman microscopy (Renishaw inVia plus), equipped with the DM2500M microscope produced by Leica Microsystems, was used to qualitatively analyze the mineral composition of different layers of gilded sample cross-sections. It used 785 nm semiconductor laser sources, with an information collection time of 10 seconds, a cumulative acquisition time of 3 times, and a spectral recording range of 2000–100 cm−1.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis (FTIR): The Agilent 4300 portable infrared spectrometer was used on-site to collect spectral information from the gilding areas, equipped with a DTGS detector and a testing range of 4000–650 cm−1. The Thermo Scientific Nicolet iN10 MX micro-infrared spectrometer was used in the laboratory, featuring a liquid nitrogen-cooled MCT/A detector and a testing range of 4000–675 cm−1. The spectral resolution was set at 4 cm−1, with 64 scans performed.

Pyrolysis with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis (Py-GC/MS): The Py-GC/MS consists of a Frontier Lab EGA/PY3030D pyrolyzer coupled with an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph and an Agilent 7890B mass spectrometer. The gas chromatograph column is an HP-5MS (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) capillary column. Pyrolysis conditions were as follows: the pyrolysis temperature of the sample was set at 600 °C, with a pyrolysis time of 0.2 min, and the interface temperature between the injector and the chromatograph was maintained at 300 °C. During the experiment, approximately 0.2 mg of the sample was placed in a stainless steel sample pool and then tested in a quartz liner specifically designed for pyrolysis. Gas chromatograph conditions included an initial column temperature of 60 °C held for 5 min, followed by an increase to 200 °C at a rate of 7 °C/min and held for 2 min, then further increased to 220 °C at a rate of 2.5 °C/min and held for 5 min. The helium gas flow rate was set at 1 mL/min, with a split ratio of 50:1. Mass spectrometry conditions involved using an electron impact ionization source and a single quadrupole mass detector to acquire mass spectrometry spectra. The scan speed was set at 1 scan/s, with a scan range of 50–710 m/z, and the scan time was 1 h. NIST 07 database was used for identifying compounds.

Results

Gold foil analysis

Table 2 presents the compositional analysis and thickness measurements of gold foils. Samples GF-1 and GF-2, extracted from the Northern Song Dynasty murals, display gold (Au) content of 89.73% and 97.40%, with silver (Ag) content of 10.27% and 2.60%, and thicknesses of 0.99 μm and 1.43 μm, respectively. In contrast, samples GF-3 and GF-4 from the Western Xia murals show no detectable Ag, indicating they are pure gold, with thicknesses of 2.31 μm and 2.43 μm, respectively. This suggests that the gold foils used in the Western Xia murals are of higher purity and greater thickness.

During the investigation, it was observed that the gold foils used in the main chamber of the Northern Song Dynasty murals were mostly rectangular, highly regular, and uniformly sized (Fig. 4a–c). Using a vernier caliper, the average size of the gold foils was measured to be approximately 4.14 cm × 2.87 cm. Officially, the gold foils used in the Ming Dynasty were “three cun and six fen (三寸六分) “. In the Qing Dynasty craftsmanship regulations, the gold foils were mainly “three cun and three fen” and “three cun”, while those sold in the market also included “one cun and one fen”6. Current enterprise standards for the gold foil industry also have corresponding regulations on the sizes of gold foils. For instance, the enterprise standards of Nanjing Jinxian (南京金线) Gold Foil Factory specify four standard sizes for gold foils: 10.90 cm × 10.90 cm, 9.33 cm × 9.33 cm, 8.33 cm × 8.33 cm, and 8.00 cm × 8.00 cm.

The figure consists of two main sections: upper Section (SEM Images): Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images of gold foil samples labeled GF-1 to GF-4. These high-magnification images reveal the microstructural details, layering, and surface characteristics of the gold foils. Each image includes a scale bar of 5.00 µm to provide a reference for the size of observed features. lower Section (Mural Appearance): Photographs showing the appearance of gold foils on specific parts of Northern Song Dynasty murals: a relief-sculpted bell, b relief-sculpted coiled dragon, and c relief-sculpted canopy. These images illustrate the shapes of the gold foils and their application methods, highlighting their visual impact and contextual positioning within the murals.

Gilding in Northern Song Dynasty

The layered structure of sample C55-1, as shown in Fig. 5a, b, which consists of six layers from the surface to the bottom: the gold foil layer (L1, <2.0 μm), the red layer (L2, 5.5–8.4 μm), the raised-line layer (L3, 620.4–752.9 μm), the black layer (L4, 5.5–43.8 μm), the green layer (L5, 25.1–62.5 μm), and the white ground layer (L6, 48.6–96.8 μm). The red layer (L2) primarily contains elements such as Fe, Si, Al, C, and O. Raman spectroscopic peaks of the red layer appear at 221.2 cm−1, 288.5 cm−1, 405.9 cm−1, 495.6 cm−1, 610.7 cm−1, 1341.1 cm−1, 1560.9 cm−1, and 1870.9 cm−1 (Fig. 5c). Peaks at 221.2 cm−1, 288.5 cm−1, 405.9 cm−1, 495.6 cm−1, and 610.7 cm−1 correspond to the characteristic Raman spectroscopic peaks of hematite (Fe2O3). The signals at 221.2 cm−1 and 495.6 cm−1 arise from the stretching vibrations of Fe-O bond, while signals at 288.5 cm−1, 405.9 cm−1, and 610.7 cm−1 are attributed to the bending vibrations of Fe-O bond20,21. The raised-line layer (L3) contains elements such as Al, Mg, Si, Ca, K, Na, C, and O. XRD analysis (Fig. 5d) indicates that it primarily contains quartz (32.5%), albite (30.3%), and microcline (19.8%), followed by dolomite (9.5%), muscovite (4.0%), and gypsum (3.9%). The black layer (L4) is primarily composed of C, with O, Si, Ca, and Mg as secondary components. This layer appears the darkest in BSE images, suggesting it may be black ink. Prior to gilding, black inscriptions were written first, serving as a draft or underlayer. The green layer(L5), which serves as the dominant hue in the cave, primarily contains the elements Cu and Cl. Raman spectroscopic peaks of the green pigment are observed at 347.3 cm−1, 460.4 cm−1, 504.3 cm−1, 634.3 cm−1, 816.6 cm−1, 908.2 cm−1, 965.3 cm−1, 1300.8 cm−1, and 1591.7 cm−1 (Fig. 5c). Peaks at 504.3 cm−1, 816.6 cm−1, 908.2 cm−1, and 965.3 cm−1 match the characteristic Raman spectroscopic peaks of atacamite (Cu2(OH)3Cl)21,22. The white ground layer (L6) contains elements such as Si, Mg, Ca, K, and O. Both the murals of the Northern Song Dynasty and those of the Western Xia in Cave 55 utilize white pigments as the ground layer, which primarily consist of Ca and Fe. XRD analysis reveals that the main mineral phases are quartz, muscovite, talc, calcite, gypsum, and kaolinite23.

a OM image of C55-1: optical microscope image showcasing the distinct layers within sample C55-1. Yellow arrows and numbers (1-6) indicate different layers or features for identification. b BSE image of C55-1: back-scattered electron microscope image providing a different perspective on the microstructure of the layers in sample C55-1. c Raman spectroscopy of red layer (L2) and green layer (L5): Raman spectra obtained from the red layer (L2) and green layer (L5) of the sample. The spectra reveal characteristic peaks that can be used to identify the chemical composition and molecular structure of these layers. The peaks marked in red are the characteristic Raman peaks of the substance. d XRD pattern of raised-line layer (L3): X-ray diffraction pattern of the raised-line layer (L3). The peaks in the pattern correspond to different crystalline phases, with the legend indicating the possible mineral phases (Quartz, Albite, Microcline, Dolomite, Muscovite-3T, Gypsum) present in this layer.

The layered structure of sample C55-2 comprises six layers from the surface to the bottom (Fig. 6a, b): the gold foil layer (L1, <2.0 μm), the red layer (L2, 4.9–7.1 μm), the white layer (L3, 45.6–66.1 μm), the raised-line layer (L4, with the thickest part at 427.9 μm), the white ground layer (L5, 39.8–50.8 μm), and the plaster layer (L6). There is partial overlap of the gold foil, and its surface is covered with residues from the plaster layers of the Western Xia mural. The red layer (L2) contains elements such as Fe, Si, Ca, C, K, and O. Signal peaks at 224.8 cm−1, 291.5 cm−1, 409.6 cm−1, and 611.9 cm−1 in the Raman spectrum (Fig. 6c) correspond to the characteristic peaks of hematite. The white layer (L3) contains elements such as Si, Mg, Ca, Al, K, C, and O. The strongest peak in the Raman spectrum of the white pigment appears at 1083.1 cm−1 (Fig. 6c), matching the characteristic peak of calcium carbonate (CaCO3)24. The raised-line layer (L4) contains elements such as Si, Al, Ca, Mg, K, Fe, C, and O. XRD analysis (Fig. 6d) reveals that it primarily consists of albite (33.4%), sanidine (22.5%), and quartz (21.2%), followed by muscovite (13.0%) and dolomite (9.9%). The white ground layer (L5) contains elements such as Si, Mg, Ca, Al, C, K, and O. The result of Raman spectroscopy analysis is the same as that of the white layer (L3), indicating calcium carbonate. The plaster layer (L6) contains elements such as Si, Al, Ca, Mg, K, Fe, C, and O. XRD analysis (Fig. 6d) indicates that the plaster layer comprises quartz (17.5%), calcite (27.7%), albite (23.9%), muscovite (6.2%), clinochlore (8.0%), dolomite (4.7%), gypsum (3.8%), and talc (8.2%). This composition is similar to that of the plaster layers of other murals in the Mogao Caves and the deposited soil in the Dangquan River25.

a OM image of C55-2: optical microscopy image showing the macroscopic layered structure of sample C55-2. Yellow arrows and numbers (1-6) indicate different layers or features for identification, with a yellow dashed box highlighting a region of interest for further magnification or analysis. b BSE image of C55-2: back-scattered electron microscope image providing a different perspective on the microstructure of the layers in sample C55-2. c Raman spectroscopy of red layer (L2) and white layer (L3): Raman spectra acquired from the red layer (L2) and white layer (L3). The spectra reveal characteristic peaks that can be used to identify the chemical composition and molecular structure of these layers. The peaks marked in red are the characteristic Raman peaks of the substance. d XRD pattern of raised-line layer (L4) and plaster layer (L6): X-ray diffraction patterns obtained from the raised-line layer (L4, orange line) and plaster layer (L6, green line). The patterns show diffraction peaks corresponding to various crystalline phases, with the legend listing potential mineral phases (quartz, albite, dolomite, etc.) identified in these layers.

The layered structure of sample C55-3 consists of five layers from the surface to the bottom (Fig. 7a, b): the gold foil layer (L1, <2.0 μm), the red layer (L2, 2.8–5.6 μm), the yellow layer (L3, 9.8–22.7 μm), the red layer (L4, 8.3–42.3 μm), and the white ground layer (L5, 44.8–81.1 μm). The red layer (L2) located beneath the gold foil primarily comprises elements such as Fe, Si, Al, C, and O. The Raman spectrum of the red layer exhibits characteristic peaks corresponding to hematite at 223.9 cm−1, 289.9 cm−1, 410.7 cm−1, and 610.3 cm−1. The yellow layer (L3) primarily comprises the elements As and S, followed by C, O, and Si. The strongest signal in the Raman spectrum of the yellow layer is observed at 349.7 cm−1, with a secondary peak at 303.5 cm−1. Additionally, there is a distinct medium-intensity signal at 284.1 cm−1, and a characteristic signal at 376.0 cm−1 (Fig. 7c), which are consistent with the Raman spectral characteristic peaks of orpiment (As₂S₃)26,27. These signals belong to the stretching vibrations of As-S bond. The red layer (L4) primarily contains Hg elements, with the strongest peak in the Raman spectrum at 246.4 cm−1, the second strongest peak at 349.1 cm−1, and medium-intensity peaks at 282.8 cm−1 and 301.7 cm−1. Additionally, signal peaks are observed at 128.6 cm−1, 145.7 cm−1, and 194.7 cm−1 (Fig. 7d). The peaks at 246.4 cm−1, 282.8 cm−1, and 349.1 cm−1 are the main Raman vibrational characteristic peaks of cinnabar (HgS)12,26. This red pigment layer is likely the color used for the Buddha’s cassock. The white ground layer(L5) contains elements such as Mg, Si, Ca, Al, C, and O, and its main component is calcium carbonate.

a OM image of C55-3: optical microscopy image revealing the distinct color-coded layers within sample C55-3. Yellow arrows and numbers (1-5) indicate different layers or features for identification. b BSE image of C55-3: back-scattered electron microscope image providing a different perspective on the microstructure of the layers in sample C55-3. c Raman spectroscopy of yellow layer (L3): Raman spectrum obtained from the yellow layer (L3). The spectra reveal characteristic peaks that can be used to identify the chemical composition and molecular structure of these layers. The peaks marked in red are the characteristic Raman peaks of the substance. d Raman spectroscopy of red layer (L4): Raman spectrum acquired from the red layer (L4). The spectra reveal characteristic peaks that can be used to identify the chemical composition and molecular structure of these layers. The peaks marked in red are the characteristic Raman peaks of the substance.

Gilding in Western Xia

The layered structure of sample C55-4 consists of five layers from the surface to the bottom (Fig. 8a, b): the gold foil layer (L1, å 2.0 μm), the red layer (L2, actually red granules, 4.3–11.6 μm), the green layer (L3, 5.5–16.7 μm), the white ground layer (L4, 59.5–78.9 μm), the plaster layer (L5). The gold foil layer (L1) exhibits an overlapping structure, beneath which there are a few red granules (L2) primarily composed of element Pb (Fig. 8c), along with other elements such as Al, Ca, and O, presumed to be minium (Pb3O4)28. In the OM and BSE images, it can be observed that there appear to be thick, homogeneous layers of organic material between L1 and L2. However, microscopic ultraviolet observation reveals no fluorescence effect in this area. This phenomenon may be attributed to a distinct separation between the gold foil layer and the pigment layer, with resin-like materials filling the interface during the preparation of the cross-sectional sample. The green layer (L3) contains elements Cu, Cl, Pb, Ca, and O. According to XRD analysis (Fig. 8d), the green pigment is atacamite, with quartz and calcium carbonate. The white ground layer (L4) comprises elements such as Si, Mg, Al, Ca, and O, with calcium carbonate being the main color-presenting substance. The plaster layer (L5) contains elements such as Si, Al, Ca, Mg, and O.

a OM image of C55-4: Optical microscope image displaying the distinct layers within sample C55-4. The yellow arrows and numbers (1-5) mark specific layers or features, and the inset shows a UV image highlighting a particular area of interest. b BSE image of C55-4: back-scattered electron microscope image providing a different perspective on the microstructure of the layers in sample C55-4. c EDS of red layer (L2): Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy results for the red layer (L2). The spectrum indicates the presence of elements such as carbon (C), oxygen (O), aluminum (Al), calcium (Ca), and lead (Pb). The main element is Pb, and it is marked in red. d XRD pattern of green layer (L3): X-ray diffraction pattern for the green layer (L3). The pattern reveals the crystalline phases present in this layer, including calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), quartz (SiO₂), and atacamite (Cu2(OH)3Cl).

The layered structure and analytical results of samples C55-5 and C55-6 are identical. Therefore, only sample C55-5 will be described here. The layered structure of sample C55-5 consists of six layers from the surface to the bottom (Fig. 9a, b): the gold foil layer (L1, å 2.0 μm), the reddish-brown layer (L2, 7.7–9.5 μm), the white layer (L3, 8.2–11.1 μm), the raised-line layer (L4, with the thickest part being 566.4 μm), the white ground layer (L5, 74.2–85.7 μm), and the plaster layer (L6). Beneath certain sections of the gold foil, there are layers that are reddish brown and white. The white layer (L3) primarily contains elements such as Pb, Al, C, and O. The Raman spectrum of the white pigment exhibits absorption peaks at 130.2 cm−1, 232.3 cm−1, 307.8 cm−1, 397.0 cm−1, 546.2 cm−1, 804.5 cm−1, and 1048.3 cm−1 (Fig. 9c). Among these, the signal peaks at 130.2 cm−1, 397.0 cm−1, and 1048.3 cm−1 correspond to the characteristic Raman peaks of hydrocerussite (2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2). The signal at 1048.3 cm−1 originates from the v1 vibrational mode of hydrocerussite20. The reddish-brown layer (L2) primarily contains elements Pb, Al, C, and O. XRD analysis of the reddish-brown pigment (Fig. 9d) identified lead dioxide (PbO2) as the main component, with no diffraction peaks of minium (Pb3O4) observed. Under certain conditions, 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2 can produce PbO2. During the transition from red (Pb3O4) to black (PbO2), 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2 may exist as an intermediate product. However, 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2 was not detected on the actual mural. The cross-sectional image of sample C55-5 reveals distinct red and white layers, suggesting that the lead dioxide present here is a discoloration product of minium. The raised-line layer (L4) contains elements such as Si, Al, Mg, Ca, K, Na, and O. XRD analysis (Fig. 9d) indicates it is primarily composed of albite (29.6%), quartz (27.6%), and microcline (23.1%), with dolomite (9.7%), gypsum (5.2%), and muscovite (4.8%) present in smaller amounts. The white ground layer (L5) contains elements such as Si, Mg, Ca, Al, C, and O, and its main component is calcium carbonate. The plaster layer (L6) contains elements such as Si, Al, Ca, Mg, and O. XRD analysis indicates that the plaster layer comprises quartz, muscovite, clinochlore, calcite, albite, dolomite, and so on.

a OM image of C55-5: Optical microscope image illustrating the distinct layers within sample C55-5. The yellow arrow and numbers (1-6) indicate specific layers or features, with a yellow dashed box highlighting a region of interest for further magnification or analysis. b BSE image of C55-5: back-scattered electron microscope image providing a different perspective on the microstructure of the layers in sample C55-5. c Raman spectroscopy of white layer (L3): Raman spectrum obtained from the white layer (L3). The spectra reveal characteristic peaks that can be used to identify the chemical composition and molecular structure of these layers. The peaks marked in red are the characteristic Raman peaks of the substance. d XRD pattern of reddish-brown layer (L2) and raised-line layer (L4): X-ray diffraction patterns for the reddish-brown layer (L2, red line) and the raised-line layer (L4, yellow line). The patterns reveal the crystalline phases present in each layer, with the legend indicating possible mineral phases such as quartz, albite, microcline, dolomite, muscovite, gypsum, and lead dioxide.

This study has not obtained any samples of gilding on relief from the Western Xia murals. However, we can get some information from the appearance of gilding on relief at entrance corridor. Gilding on relief was primarily used to decorate the rosette pattern and the bell motif (Fig. 10a, b). After the relief bell became detached, a small amount of gold foil was left on the mural (Fig. 10c, d). This indicates that the sequence of relief sculpture gilding was as follows: first, the relief sculpture was created; then, it was affixed to the mural surface; finally, gold foil was applied. As seen in Fig. 10e, the clay relief is irregular in shape, and fingerprint patterns are visible on the surface of the gold foil. It can be inferred that these small clay relief sculptures were manually shaped and then pressed and fixed onto the mural. As observed in Fig. 10f, the gold foil does not completely cover the clay relief sculpture, and after partial gold foil peeling, a dark red color is revealed underneath.

a–d Condition of gilding on relief: photographs showing different states of gilding on relief. These images capture the varying degrees of preservation or damage to the gold leaf applied on the relief surfaces. Red arrows in (c) and (d) highlight specific areas of interest or concern regarding the gilding. e, f OM images of clay relief: optical microscope images of clay reliefs, offering a close-up view of the surface texture, and any remaining traces of gilding or other coatings. Each image includes a scale bar of 2.00 mm to indicate the magnification level and the size of observed features.

Organic material analysis

No significant presence of organic matter was detected during the on-site infrared spectroscopy tests. However, absorption peaks were observed near 1620 cm−1, 1320 cm−1, and 780 cm−1 in the spectra of the S-1 to S-3 test areas (Fig. 11a). According to literature29 and standard spectral library data, the peaks at 1623 cm−1, 1317 cm−1, and 780 cm−1 are characteristic of calcium oxalate. The peak at 780 cm−1 is a characteristic peak in the fingerprint region of calcium oxalate, corresponding to the stretching vibration of COO-. Based on this, it is initially speculated that the test areas contain calcium oxalate. The mural plaster and pigment layers contain large amounts of calcium carbonate, calcium sulfate, etc. In a humid and warm cave environment, microorganisms such as mold proliferate using organic binding materials, and during their metabolic processes, oxalic acid is produced, gradually forming various oxalate salts.

a FTIR of S-1, S-2, S-3, GF-5, and GF-6: FTIR absorbance spectra for samples S-1, S-2, S-3, GF-5, and GF-6. The spectra display characteristic absorption bands at specific wavenumbers, the Raman characteristic peaks marked in red are associated with protein-based binding materials, while those marked in blue are related to calcium oxalate. b Py-GC/MS total ion chromatogram (TIC) of C55-2 & C55-6: TIC plots for samples C55-2 (yellow line) and C55-6 (red line). The chromatograms show the intensity of ions as a function of retention time. The fragment information at the locations marked with red numbers is related to animal glue.

In the infrared spectrum, the peak at 3400–3200 cm−1 represents the stretching vibration of the amino group (N-H) in secondary amides, which is affected by the stretching vibration peak of hydroxyl groups (O-H) at lower frequencies. The peak around 2920 cm−1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibration of CH2 in saturated hydrocarbons, while the peak around 2855 cm−1 represents the symmetric stretching vibration of CH2. The peak at approximately 1650 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of the carboxyl group (C=O), and the peak around 1550 cm−1 is due to the bending vibration of the amino group (N-H). It is generally believed that the simultaneous presence of the stretching vibration peak of the carboxyl group (around 1650 cm−1) and the bending vibration peak of the amino group (around 1550 cm−1) can serve as a basis for determining whether the sample contains protein-based binding materials30. As shown in Fig. 11a, the infrared spectrum of GF-5 and GF-6 exhibit characteristics consistent with protein-based binding materials, suggesting that protein-based binding materials were used in the adhesion of the gold foils.

Figure 11b shows the total ion chromatogram (TIC) plots of Py-GC/MS analysis for samples C55-2 and C55-6. Tables 3 and 4 present the fragment information obtained from the Py-GC/MS analysis. The benzene fragment peak, observed at a retention time of 2.248 min in sample C55-6, is a cleavage product of leucine and isoleucine. The toluene fragment peaks, detected at 3.390 min in sample C55-2 and 3.302 min in sample C55-6, are cleavage products of phenylalanine. The fragment peak at 3.148 min (both in C55-2 and C55-6) corresponds to pyrrole, which, along with its derivatives, is are cleavage product of proline and hydroxyproline. These amino acids are major components of animal glue, with hydroxyproline serving as a distinguishing amino acid between animal proteins and other protein types. The pyrolysis products of animal glue primarily include pyrroles, fatty acids, proteins, trace amounts of proline derivatives, and toluene30,31. Among the numerous characteristic pyrolysis compounds, pyrrole, diketodipyrrole, and piperazinedione can be used as marker compounds for animal glue. The fragment peak at m/z = 186, with retention times of 28.284 min in sample C55-2 and 28.344 min in sample C55-6, corresponds to diketodipyrrole, originating from the dipeptide (hydroxyproline-hydroxyproline)32,33. The fragment peak at m/z = 154, with a retention time of 30.884 min in sample C55-2, belongs to hexahydro-pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, a piperazinedione compound derived from the dipeptide (proline-glycine), exclusively found in the pyrolysis products of animal glue34. Combining these results with the infrared spectroscopy analysis, it is inferred that animal glue was used as the mordant for gilding in Cave 55.

Discussion

As observed in Table 5, the murals of the Northern Song Dynasty and the Western Xia both feature three types of gilding techniques: gilding on plane mural, gilding on raised line, gilding on relief. The layered structure of the gilding can consist of up to four layers: the gold foil layer, the “Jin Jiao (金脚 or 金胶)” layer (red or reddish-brown pigment layer mixed with gold foil mordant), the preparatory layer (yellow or white pigment layer), and the raised-line layer. However, there are differences in the materials used for each layer across different periods. The gold foil employed in Northern Song Dynasty murals was an Au-Ag alloy, whereas that in Western Xia murals was nearly pure gold and of greater thickness. The red or brownish red pigment layer, blended with animal glue, comprises the “Jin Jiao” layer. This layer not only serves as a backdrop for the gold foil but also assists in the positioning of the gold foil and subsequent inspections for any missing or imperfect areas. The red pigment beneath the gold foil layer in Northern Song Dynasty murals is hematite, while in Western Xia murals, it is a lead-containing pigment, presumably minium. The preparatory layer in Northern Song Dynasty murals is calcium carbonate or orpiment, while that in Western Xia murals is hydrocerussite. From the analysis results of samples C55-1 and C55-4, it can be seen that the preparatory layer is not a mandatory process. The raised-line layers in both Northern Song Dynasty and Western Xia murals primarily contain quartz, albite, and microcline, followed by dolomite, muscovite, and gypsum, with varying relative proportions of these materials. The plaster layer of murals in Cave 55 primarily comprises calcite, albite, and quartz, with additional traces of muscovite, clinochlore, dolomite, gypsum, and talc. Based on this, it is inferred that the materials for the raised-line layers and the plaster originate from the same sources, but undergo screening and modification to meet specific requirements for color, strength, and fluidity.

Thus, what constituted the source of gold foil in this particular era? The Dunhuang region did not produce gold and silver, but the Hexi region historically yielded gold, in areas such as Suzhou (肃州), Dongting Mountain (洞庭山), and Jinshan (金山), all within the jurisdiction of the Guiyi Circuit. There are numerous records of the use of gold and silver in the Dunhuang trade market, including coins and various utensils. Due to political instability and transportation difficulties, the Dunhuang trade market suffered from a scarcity of coins during the late Tang Dynasty (晚唐, 836-907 CE) and the Five Dynasties period. The gold and silver coins circulating in the Dunhuang market were primarily sourced from the Uighur and Western Regions, with their circulation patterns closely tied to trade networks and tributary relations, as documented in Dunhuang manuscripts such as P.2569 and P.4011. During this period, precious metal vessels made of gold and silver circulated as hard currency in the market. However, due to their limited quantity and high value, they could not fully satisfy market demand and were not conducive to small-scale trade. There was also some circulation of loose gold and silver fragments, but their proportion was small. During the Guiyi Circuit period, two forms of exchange emerged in the Dunhuang region: barter and the use of commodities such as wheat, millet, cloth, and silk as media of exchange. Dunhuang manuscripts, such as P.2049 v, S.4642, and S.6452, also document the market trade of gold and silver. The Dunhuang Guiyi Circuit was a relatively independent local political entity that had to establish a comprehensive range of handicraft industries to meet the diverse needs of the government, the people, and the temples. Ancient Dunhuang had many skilled craftsmen, and numerous records in the Dunhuang manuscripts document them. The artisanal cohort involved in cave temple gilding—comprising goldsmiths, sculptors, and painters—is documented across multiple Dunhuang manuscripts, including P.2032v, P.2049v, P.2629, P.2641, P.3490v, S.2474, S.489935.

The Dunhuang Guiyi Circuit frequently interacted with the Central Plains dynasties, seeking both political recognition and support, as well as engaging in economic and trade exchanges. The tributes presented by the Guiyi Circuit to the Central Plains court were imbued with the unique characteristics of the northwest border region, often consisting of products native to Dunhuang or the Western Regions. Multiple entries in the Song Hui Yao Ji Gao (《宋会要辑稿》), a compilation of historical records of the Song Dynasty, mention military governors such as Cao Zongshou (曹宗寿), Cao Yanlu (曹延禄), and Cao Xianshun (曹贤顺) presenting tributes to the Song court and petitioning for gifts of gold foil and Buddhist scriptures written in gold and silver letters36. In conclusion, it can be inferred that much of the gold foil used in the Mogao Grottoes during the Cao Family Guiyi Circuit period likely originated from the tributary gifts bestowed by the Central Plains dynasties in return.

In conclusion, the study focuses on the gilded murals of Cave 55 from the Cao Family Guiyi Circuit period (during the Five Dynasties and the early Song Dynasty periods) in Mogao Grottoes. Using multiple analytical methods, the study systematically investigates the materials and techniques employed in the gilding of these murals. It also conducts a comparison of the materials and techniques employed in the gilded murals of the Northern Song Dynasty and those restored during the Western Xia, and explores the origin of the gold foil. The conclusions of the study are as follows:

-

(1)

The murals of the Northern Song Dynasty and the Western Xia both feature three types of gilding techniques, with up to four layers in their layered structure. However, significant differences exist in the materials used in each layer during different periods. These variations can be attributed to changes in craftsmen and material sources brought about by the shifts in political power.

-

(2)

Much of the gold foil used in the Mogao Grottoes during the Cao Family Guiyi Circuit period likely originated from the tributes and rewards bestowed by the Central Plains dynasties.

In the future, research on gilding will be conducted on the murals and polychrome sculptures in the caves from other periods at Mogao Grottoes. Additionally, murals and polychrome sculptures with gilding decorations along the Silk Road will be the focus, aiming to explore the interactive relationships of Chinese traditional gilding decoration across different regions.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Han, P. et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness and compatibility of nanolime for the consolidation of earthen-based murals at Mogao Grottoes. J. Cul. Herit. 58, 266–273 (2022).

Yin, Y. et al. Investigation of ancient wall paintings in Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Opt. Laser Technol. 120, 105689 (2019).

Bolong, C. et al. Virtual reconstruction of the painting process and original colors of a color-changed Northern Wei Dynasty mural in Cave 254 of the Mogao Grottoes. Herit. Sci. 10, 164 (2022).

Shui, B. et al. Blue pigments in Cave 256, Mogao Grottoes: a systematic analysis of murals and statues in Five dynasties, Song Dynasty and Qing Dynasty. Herit. Sci. 10, 89 (2022).

Gao, X. Study on Cave 55 of Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang. Lanzhou: Lanzhou University. J. Perform. Construc. Facilities 32, 04018048 (2016).

Liu, M. Research on pigments for decorative polychrome painting in official handicraft regulations and precedents of Qing Dynasty. Beijing: Tsinghua University. (2019.

Li, L. Research on the color painting of Yingzao Fashi. (Nanjing: Southeast University Press. 2011).

Perez-Rodriguez, J. L. et al. Gildings from Andalusia: Materials used in different types of artworks along centuries. J. Cult. Herit. 31, 112–121 (2018).

Cesareo, R., Brunetti, A. & Ridolfi, S. Pigment layers and precious metal sheets by energy-dispersive x-ray fluorescence analysis. X Ray Spectrom. 37, 309–316 (2008).

Pessanha, S. et al. Determination of gold leaf thickness using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry: accuracy comparison using analytical methodology and Monte Carlo simulations. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 152, 6–10 (2019). 2019.

Sansonetti, A. et al. Territory and related artworks: Stuccoworks from the Lombard Lakes. J. Cult. Herit. 46, 382–398 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Studies on wall painting materials and techniques at two historic buildings in Gyantse, Tibet. Herit. Sci. 7, 40 (2019).

Wu, Q. et al. Does substrate colour affect the visual appearance of gilded medieval sculptures? Part II: SEM–EDX observations on gold leaf samples taken from medieval wooden sculptures. Herit. Sci. 8, 119 (2020).

Song, Y. et al. A technical study of the materials and manufacturing process used in the Gallery wall paintings from the Jokhang temple, Tibet. Herit. Sci. 6, 18 (2018).

Wang, N. et al. Complementary analytical methods in identifying gilding and painting techniques of ancient clay-based polychromic sculptures. Microchem. J. 114, 125–140 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Micro-Raman, XRD and THM-Py-GC/MS analysis to characterize the materials used in the Eleven-Faced Guanyin of the Du Le Temple of the Liao Dynasty, China. Microchem. J. 171, 106828 (2021).

Zhou, Z. et al. Investigation of gilding materials and techniques in wall paintings of Kizil Grottoes. Microchem. J. 154, 104548 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Investigation of gold gilding materials and techniques applied in the murals of Kizil Grottoes, Xinjiang, China. Appl. Sci. 12, 11202 (2022).

Radpour, R. et al. Identification and mapping of ancient pigments in a Roman Egyptian funerary portrait by application of reflectance and luminescence imaging spectroscopy. Herit. Sci. 10, 8 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Microchemical study of pigments and binders in polychrome relics from Maiji Mountain grottoes in Northwestern China. Microsc. Microanal. 22, 845–856 (2016).

Mei, Y. et al. Characterizing pigments, dyes, and fibers in murals from Bezeklik Cave 51 and Tuyoq Cave 2. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 251 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Degradation of emerald green: scientific studies on multi-polychrome Vairocana Statue in Dazu Rock Carvings, Chongqing, China. Herit. Sci. 8, 64 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Analysis of the mural-making materials and techniques in Mogao Cave 55. Res. Conserv. Cave Temples Earthen Sites 2, 68–77 (2023).

Zhu, T. et al. Hexi painting on Xitian Fanjing, a Qing imperial Buddhist temple in Beijing, China: technology revealed by analytical approaches (an initial report). Herit. Sci. 4, 42 (2016).

Lori, W. & Neville, A. The conservation of Cave 85 at the Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang: a collaborative project of the Getty Conservation Institute and the Dunhuang Academy (Getty Publications, 2013).

Tomasini, E. P. et al. Characterization of pigments and binders in a mural painting from the Andean church of San Andr‚s de Pachama (northernmost of Chile). Herit. Sci 6, 61 (2018).

Gebremariam, K. F., Kvittingen, L. & Nicholson, D. G. Multi-analytical investigation into painting materials and techniques: the wall paintings of Abuna Yemata Guh church. Herit. Sci. 4, 32 (2016).

Gasanova, S. et al. Giovanni Baronzio’s ‘Crucifixion’: analytical approaches and art historical considerations. Herit. Sci. 8, 99 (2020).

Shen, L. et al. Cu and As-containing pigments in Zhejiang architecture polychrome paintings: a case study of degradation products of emerald green. Herit. Sci. 11, 9 (2023).

HE, L. Analysis and Identification of Ancient Chinese Polychromy (Science Press, 2017).

Xiao, B., Wei, S. & Song, Y. Analysis and identification of protein-cement materials in murals by thermally assisted methylation-pyrolysis gas chromatography (THM-Py-GC/MS). Sci. Res. Chin. Cult. Relics 1, 70–76 (2018).

Chiavari, G. et al. Characterisation of standard tempera painting layers containing proteinaceous binders by pyrolysis (/methylation)-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Chromatographia 47, 420–426 (1998).

Chiavari, G. et al. Analysis of proteinaceous binders by in-situ pyrolysis and silylation. Chromatographia 57, 645–648 (2003).

Wei, S., Ma, Q. & Schreiner, M. Scientific investigation of the paint and adhesive materials used in the Western Han dynasty polychromy terracotta army, Qingzhou, China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39, 1628–1633 (2012).

Ma, D. Ancient Craftsman Research of Dunhuang (Cultural Relics Press, 2018).

XU, S. Song Hui yao Ji gao. (Zhonghua Book Company, 1957).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jianhua Huang from Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum for help with Raman spectrometry analysis. The authors also wish to express their gratitude for State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics (Northwest University, China). This study has been financially supported by the Funding Project for Cultural Relics Protection Science and Technology Research in Gansu Province, 2022 (No. GSWW202224), by the Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Program Project, 2024 (No. 24JRRF014), and by the Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Program Project, 2025 (No. 25JRRF001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C. performed the Dunhuang manuscripts investigation, on-site non-destructive analysis, slightly destructive sampling analysis of gilding murals in Cave 55, and wrote the first draft of this paper. W.R. and Y.Z.R. conceptualized the main research ideas of this work and guided the direction of this study. S.B.W. performed the X.R.D. analyses on plaster and raised-line samples. Z.J.L. performed Py-GC/MS on the blocky gilding samples. C.Q. and L.P. performed the OM on the gilding murals. S.Z.W. performed the SEM-EDS analyses on the blocky gilding samples.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, C., Shui, B., Zhao, J. et al. Investigation on gilding materials and techniques of murals in Cave 55 at Mogao Grottoes. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 573 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02101-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02101-2