Abstract

Open tombs in humid regions are highly susceptible to mural deterioration driven by microclimate fluctuations, especially salt crystallization, condensation, and microbial growth. However, the effectiveness of environmental control strategies in such settings remains insufficiently studied. This study evaluates a buffer space-based environmental control system installed at Qinling Tomb, a 10th-century tomb in southern China. The system comprises three doors and two rooms, one equipped with air conditioning and a dehumidifier, regulating air exchange and incoming air properties. Compared to 2021 (pre-intervention), zones with the largest microclimatic fluctuations showed significant reductions in 2022—60% at 3.0 m in the front chamber for temperature, and 43% at 0.1 m in the back chamber for relative humidity. Moreover, the coverage of surface salt crystallization in winter and condensation in summer was reduced by ~80%. This approach provides a scalable, adaptable solution for preserving open tombs and other vulnerable heritage sites exposed to similar risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Murals in tombs are invaluable cultural heritage, offering direct insight into ancient burial customs, social structures, and beliefs1,2. While sealed underground tombs originally maintained stable microclimates conducive to mural preservation, archaeological excavation and subsequent public access have disrupted these conditions3,4,5. Tombs in humid regions are subject to intense rainfall and persistent humidity, which exacerbate mural deterioration and introduce complex environmental conservation challenges. Abundant water and salt migration from surrounding soils induce cycles of salt crystallization and dissolution, which mechanically stress and deteriorate mural substrates6,7,8. High ambient humidity promotes condensation within the tomb, resulting in liquid water formation on mural surfaces and within materials9,10,11, which critically facilitates fungal spore germination and microbial colonization12,13,14,15,16. Collectively, these factors contribute to accelerated deterioration processes in tombs, underscoring the critical role of effective environmental control and conservation strategies.

In recent years, environmental regulation has been increasingly applied to subterranean tombs across diverse climatic regions in response to emerging conservation challenges. In arid regions such as Egypt, high temperatures and low humidity generally contribute to the long-term preservation of tombs. However, increased tourist influx leads to elevated humidity, CO₂ concentrations, and dust accumulation, all of which accelerate deterioration. To mitigate these effects, visitor control and enhanced ventilation have mitigated humidity spikes in tombs like the Tomb of Nefertari Merytmut (QV66)17 and the Tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt18, where relative humidity is maintained at ~60%, with daily fluctuations limited to 20%. However, tombs in humid climates face more complex conservation challenges due to abundant precipitation and pronounced seasonal fluctuations. To stabilize environmental conditions, various preservation strategies have been employed, such as site sealing and mechanical climate control19,20,21. These measures have relatively reduced environmental fluctuations, however, attempts to maintain a temperature of 18 °C and relative humidity of 90% with air conditioning in Tomb No. 6 (Songsan-ri, Gongju, Republic of Korea) led to conditions that influenced the murals22,23. These cases highlight the need to tailor environmental control to the specific material responses of heritage sites, especially in humid climates where balancing microclimate stability with material tolerance is critical.

Open tombs accessible to the public face additional challenges. Public access intensifies hygrothermal fluctuations due to unregulated air exchange and visitor-generated heat and CO₂24,25,26. Artificial lighting used for display can promote biofilm growth on mural surface, affecting the microclimate and increasing deterioration risks27,28. Current research on open tomb conservation remains limited, often focusing on emergency restoration materials29,30, whose long-term effectiveness is uncertain31. This highlights the urgent need for preventive conservation strategies based on environmental control, especially in humid regions, where a systematic framework addressing hygrothermal dynamics, salt migration, and public access is lacking.

This study investigates open tomb conservation in humid climates using the Southern Tang Dynasty tombs in China as case studies (Fig. 1). Building on our previous work on mural disease-environment correlations32 and hygrothermal modeling, an environmental control strategy is proposed that combines an automated door system combined with a hygrothermal buffering entrance zone. Through a two-year in situ experiment at Qinling Tomb (one of the tombs of the Southern Tang Dynasty)—including one year of baseline monitoring and one year of intervention—we analyze the effectiveness of the system in reducing microclimatic fluctuations, salt crystallization, and condensation. The findings provide a scientific basis for targeted environmental control strategies in open tombs, supporting both conservation and public exhibition.

Methods

Research site

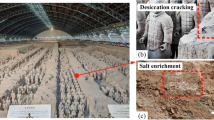

Southern Tang Dynasty (937–975 AD), founded by Emperor Li Bian and based in Jinling (present-day Nanjing, China), left behind notable imperial tombs, among which Qinling Tomb stands as the largest and most representative. Qinling Tomb is a south-facing subterranean structure consisting of three main chambers and ten side chambers (Fig. 1a, b). Inheriting the burial traditions of the Sui and Tang dynasties, it was constructed using masonry that imitates timber structures, including columns, beams, and arches. It is also adorned with colorful murals, warrior statues, and intricate double-dragon motifs, vividly reflecting the ritual codes and artistic style of Southern Tang Dynasty (Fig. 1c, d).

Excavated in the 1950s and opened to the public in the 1980s, the tomb was fitted with an antique-style wooden door and has remained open daily from 08:00 to 17:00 (Fig. 1e). To mitigate the water seepage in the tomb, conservation interventions were carried out in stages: an impermeable concrete dome over the tomb, waterproof curtain walls around the back chamber, and drainage around the mound (Fig. 1a, b). While these measures effectively mitigated groundwater infiltration, they failed to prevent microclimatic fluctuations within the tomb. Nanjing is classified as a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) according to the Köppen system, with hot, humid summers and mild winters. These climatic characteristics result in significant seasonal and diurnal variations in temperature and relative humidity inside the tomb. These conditions contribute to ongoing deterioration risks, including salt crystallization, condensation, and microbial growth on mural surfaces (Fig. 1f).

Qinling Tomb was constructed using diverse materials: the back chamber is made of stone, while the other chambers use blue bricks. All chambers were originally coated with white or red earthen plaster layers (Fig. 1d). Analysis shows that the white earthen plaster layer consists mainly of calcite, while the red layer contains both calcite and hematite, with quartz and albite in both. Wall paintings mostly use red (Hg/Pb, composed of minium and cinnabar) and green (Cu, composed of malachite) mineral pigments. Salt in the tomb mainly appears as needle-like and powdery substances. White needle-like crystals such as those on the east wall of the front chamber, exhibit rod- and needle-shaped microstructures, composed of Na, S, and O. These crystals are identified as sodium sulfate (Fig. 2ad). White powdery salts (e.g., the salt on the west wall in the front chamber) show rod-, needle-, and strip-like microstructures with Ca, S, and O, and are identified as calcium sulfate (Fig. 2e–h). Given the low solubility and limited climatic sensitivity of calcium sulfate (gypsum), this study focuses on sodium sulfate. In addition, microbial sampling and sequencing conducted in Qinling Tomb in 2020 identified phyla including Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidota, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteria, Planctomycetota, and Firmicutes. Among these, Cyanobacteria (29%–37.6%), Proteobacteria (21.2%–34.7%), and Actinobacteria (5.2%–20.3%) were the most dominant33.

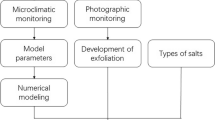

Comparative experimental design and data analysis

To support the in-situ environmental control research on the Two Tombs of the Southern Tang Dynasty, this study first conducted a comprehensive environmental survey to establish the relationship between hygrothermal fluctuations and mural distribution patterns. Temperature and relative humidity were measured at multiple locations and heights inside the tomb (Table 1 and Fig. 3), with points labeled by chamber and height (e.g., F3.0 indicates 3.0 m height in the front chamber). Salt crystallization and condensation were documented through regular photography and mapped seasonally using AutoCAD software to clarify their correlation with the indoor environment32. The baseline survey showed that seasonal salt crystallization and condensation in the tomb were strongly associated with air exchange through the entrance: during summer, humid air infiltrated the tomb, causing condensation on the walls with lower surface temperatures, while in winter, dry air reduced relative humidity and promoted salt crystallization. Based on heat and moisture coupled transfer theory34, a heat–air–moisture (HAM) model was developed to simulate the effects of different control strategies, including reduced ventilation, entrance temperature and humidity control, and full tomb enclosure35. The simulations indicated that fully closing the entrance door would be the most effective way to minimize both salt crystallization and condensation inside the tomb, as the indoor microclimate remained close to the annual mean temperature with high relative humidity. This provided a basis for designing the in-situ control system and comparative monitoring.

In subsequent experiments, the effectiveness of the environmental control measures will be assessed by comparing hygrothermal conditions and deterioration patterns before and after the intervention. Given that sodium sulfate is the dominant soluble salt and its phase transitions are sensitive to hygrothermal changes, a thermodynamic phase diagram was used as an indicative reference to evaluate crystallization risk6. However, it should be noted that the calculated number of cycles does not represent the actual phase transitions occurring in the material.

Environmental control strategy and system setup

To mitigate salt crystallization and condensation risks within Qinling Tomb, an environmental control system was installed at its entrance. Hygrothermal monitoring and deterioration mapping were carried out from 2021 to 2022. Data collected under natural conditions in 2021 served as the control group, while data from 2022 under regulated conditions served as the experimental group.

As an open tomb, air exchange through the entrance was a major driver of temperature and humidity fluctuations within the tomb. While full tomb enclosure was the most effective way to reduce salt crystallization and condensation risks35, complete isolation from the external environment was not feasible due to the need for public access. To reconcile conservation requirements with accessibility, a buffering system was developed to regulate both the intensity of air exchange and the air hygrothermal properties of incoming air in the buffer zone. The system adopted a hybrid passive-active strategy: passive control was achieved through door operation and spatial configuration, while active regulation targeted the buffer zone air and was implemented using an air conditioner and dehumidifier. To minimize construction-related impacts on the tomb, a lightweight steel framework with a modular design was adopted for easy on-site assembly and disassembly (Fig. 4a).

The environmental control system was specifically designed to mitigate the influence of external climatic fluctuations, thereby stabilizing the tomb’s internal microclimate and reducing deterioration risks such as salt crystallization and condensation. The structure consisted of two primary chambers and three access doors, and was constructed from corrugated color steel panels and glass curtain walls. The buffer zone measured 6.3 m (length) × 3.3 m (width) × 3.2 m (height). Serving as a transitional interface, the buffer space enabled controlled air exchange and facilitated targeted temperature and humidity control. A sectional diagram of the buffer space is shown in Fig. 4b.

Room 1 serves as the entry zone, allowing visitors passage while buffering the tomb from direct external climatic influences (Fig. 4b). It mitigates temperature and humidity fluctuations caused by visitors entering the tomb. Room 2, adjacent to the tomb (Fig. 4b), is equipped with an air conditioner (Xiaomi KFR-35GW/N1A3; 3500 W cooling, 4000 W heating, 650 m³/h airflow) and a dehumidifier (Deye DYD-N20A3; 20 L/day capacity) to precondition the incoming air. The buffering space includes three doors (D1, D2, and D3). D1, managed by the tomb administration, remains open daily from 08:00 to 17:00. D2 and D3 are sensor-operated and manually adjustable to control airflow. D2 limits external climatic intrusion, while D3 modulates inlet air volume based on internal and external hygrothermal conditions.

Winter environmental control strategy

In December 2021, an environmental control system was installed at the entrance of Qinling Tomb. The experiment began the same month, testing the effects of airflow by setting doors D2 and D3 to open for durations ranging from 0 to 24 h. By early March 2022, as temperature and humidity gradients between the tomb and external environment declined, both doors D2 and D3 were kept fully open to promote natural equilibrium.

Summer environmental control strategy

Due to persistent condensation observed since May 2021, an adaptive control strategy was implemented in May 2022. During the daytime, D2 and D3 remained closed to limit heat and moisture ingress. To enhance environmental stability, air conditioning was introduced. From May 15 onwards, the air conditioner operated nightly while D3 remained open, continuing until early July when localized surface condensation reappeared.

In peak summer, intensified measures were adopted to manage pronounced hygrothermal fluctuations. In July, the continuous opening of D3 during visitor hours promoted air exchange, increasing the risk of hot, humid intrusion and subsequent condensation on tomb walls. To counter this, Room 2 was actively dehumidified to stabilize internal conditions and reduce moisture influx. Additionally, three different control scenarios (Table 2) were tested to evaluate the effectiveness of buffer space configurations under summer conditions. Comparative analysis of temperature, humidity, and condensation patterns under different scenarios offered insights for optimizing seasonal environmental control strategies.

Results

Seasonal variations in temperature, humidity, and deterioration distribution

Figure 5a shows the monthly average temperature and relative humidity in Qinling Tomb from October 2020 to December 2022. Before environmental control (2021), temperature showed clear seasonal fluctuations—higher in summer (June–August) and lower in winter (December–February). The most pronounced fluctuation occurred at 3.0 m in the front chamber (F3.0), ranging from 8.9 °C to 28.6 °C (Δ T = 19.7 °C). Following the implementation of control measures in 2022, the temperature range significantly decreased, resulting in a more stable overall temperature. The temperature range at F3.0 significantly narrowed to 12.8 °C–19.9 °C (Δ T = 7.1 °C), marking a 64% reduction compared to 2021. Moreover, summer temperatures became more uniform, aligning closely with the annual outdoor average of 17.0 °C. Regarding relative humidity, values remained consistently high from May to September 2021, often nearing 100.0%. The greatest fluctuation occurred at 0.1 m in the back chamber (B0.1), ranging from 29.6% to 100.0% (Δ RH = 70.4%). In 2022, relative humidity became more stable and remained consistently above 90%. The annual range at B0.1 decreased to 59.7%–100.0% (Δ RH = 40.3%), accompanied by a notable increase in average humidity.

Figure 5b shows the kernel density plot of temperature in 2021 and 2022. The y-axis (density) represents the relative concentration of data near a certain value, with the area under the curve indicating the probability of values within a given range. In 2021, air temperature ranged from ~5.0 °C to 28.0 °C, exhibiting three distinct peaks corresponding to winter, transitional (spring–autumn), and summer periods. By contrast, the 2022 data were concentrated within a narrower band (13.0–20.0 °C), forming a single peak near 17.0 °C, indicating more stable thermal conditions after environmental control. Figure 5c shows the relative humidity density plot. In 2021, values were heavily skewed toward 100.0%, though significant fluctuations were observed at F3.0 and B0.1 (minimum values below 60%). In 2022, the range narrowed substantially, with increased density in the high-humidity zones, reflecting improved environmental stability.

Winter environmental control experiments

Qinling Tomb has a single entrance and notable depth and height. These characteristics lead to significant hygrothermal gradients within the tomb. In 2021, the largest annual temperature fluctuation was recorded at 3.0 m height in the front chamber (F3.0), while the greatest annual humidity variation observed at 0.1 m in the back chamber (B0.1). Therefore, F3.0 and B0.1 were selected as representative locations for assessing the effects of the environmental control.

Figure 6a–c presents the fluctuation of temperature, relative humidity, and absolute humidity in the front and back chambers from December 2021 to March 2022, alongside daily D3 door opening durations. In the initial stage, different durations of door openings were tested. Results show that with D3 closed, relative humidity remained above 90% in most zones. Upon opening D3, indoor humidity rapidly declined to near outdoor levels within 1–2 h, especially near the entrance, while changes were less pronounced deeper inside. After door closure, the temperature and humidity gradually returned to steady-state values. Daily D3 opening led to a gradual decline in both temperature and humidity, with the lowest humidity recorded in February (Fig. 8b, d). Figure 6e, f shows the temperature and relative humidity kernel density graph at F3.0 and B0.1 before (January 2021) and after environmental control (January 2022). The Y-axis represents data concentration around specific values, with the area under the curve indicating probability. The environmental control increased both temperature and humidity while reducing daily fluctuations in January. Before environmental control, temperatures ranged approximately from 9.0 to 14.0 °C, with peaks near 11.0 °C and 13.0 °C; relative humidity fluctuated widely between 30.0% and 100.0%, with low density (below 0.04) across the range. After environmental control, the temperature increased and concentrated between 14.0 and 18.0 °C, and relative humidity ranged from 70.0% and 100.0%, with significantly higher density (above 0.15) in the humidity range above 95%.

To assess the risk of salt crystallization before and after environmental control, a sodium sulfate phase diagram based on a thermodynamic model was used to analyze phase transitions. Figure 7 shows the potential risk of sodium sulfate phase transitions driven by tomb environmental fluctuations. The calculated cycles provide an indicative measure of crystallization risk rather than representing the actual number of phase transition events. Figure 7a shows that before environmental control, the temperature and relative humidity in the tomb exhibited broader distributions, leading to more frequent phase transitions, while the improved hygrothermal stability after environmental control reduced this risk. Figure 7b shows that the numbers of calculated phase transition cycles decreased by 24% at 0.1 m in the back chamber (from 184 in 2021 to 140 in 2022) and by 36% at 3.0 m in the front chamber (from 321 in 2021 to 206 in 2022). Overall, these results suggest that environmental control substantially reduced the risk of sodium sulfate phase transitions.

Figure 8 compares the distribution of salt crystallization on the west wall before and after environmental control. In January 2021, extensive salt crystallization was observed on the lower surface of the entrance, front, and middle chamber walls. In January 2022, the affected area had decreased by ~88%, with only localized deposits remaining. A detailed comparison at locations A (doorway), B, and C (west wall of the front chamber) confirms a significant reduction in crystallization extent. However, due to the repeated opening of door D3 during the environmental control period in winter, a slight increase in salt crystallization was observed in February 2022 compared to January.

Summer environmental control experiments

Figure 3 presents outdoor temperature and humidity in July 2021 and July 2022. In July 2021, the monthly average temperature was 27.1 °C (ranging: 21.5–40.2 °C) and relative humidity averaged 92.9% (ranging: 58.9–100.0%). In July 2022, these values were 29.5 °C (ranging: 22.8–42.3 °C) and 87.7% (ranging: 50.3–100.0%), respectively. The similarity in outdoor conditions between the two years indicates that interannual variation had minimal influence on experimental outcomes.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the buffer space in moderating internal temperature, humidity, and condensation, hygrothermal conditions in the back chamber were compared before and after environmental control. This chamber was selected due to severe condensation observed in 2021. The experiment applied three control conditions, each lasting seven days (Table 2). Over this period, temperature and humidity remained relatively stable, with a noticeable reduction in condensation coverage (Fig. 9).

Figure 9 shows temperature, relative humidity, and absolute humidity at F3.0 and B0.1 in July 2021 (before environmental control) and July 2022 (after environmental control). Temperature fluctuations were significantly reduced after environmental control (Fig. 9a). At F3.0, the temperature fluctuation range decreased from 21.5–28.6 °C (ΔT = 7.1 °C) in 2021 to 17.2–19.3 °C (Δ T = 2.1 °C) in 2022. At B0.1, the fluctuation range decreased from 19.9–22.5 °C (Δ T = 2.6 °C) to 16.6 °C–17.1 °C (Δ T = 0.5 °C). Relative humidity remained near 100% in both years, though occasional daytime temperature increases reduced relative humidity at F3.0 to 89.8% before environmental control (Fig. 9b). Figure 9c shows that the mean absolute humidity in July declined from 18.7 g/kg to 12.8 g/kg, and the maximum daily fluctuation dropped from 5.3 g/kg to 1.5 g/kg. Absolute humidity had smaller values and lower variability after environmental control, consistent with temperature stabilization.

Figure 10 compares the condensation distribution in July 2021 and 2022. Before environmental control, condensation was widespread—covering the ceilings and upper walls of the entrance, front, and middle chambers, as well as all walls of the back chamber. In July 2022, condensation was largely eliminated and limited to small areas on the back chamber walls. The total condensation coverage decreased by ~78%. Furthermore, in 2021, condensation persisted from May to October, whereas in 2022, it was restricted to July–August, indicating improved moisture control following the implementation of environmental control.

Discussion

The conservation of tomb murals, especially those in accessible tombs, is significantly challenged by environmental fluctuations that induce mold growth, flaking, and other deterioration processes. The microclimate in tombs is largely controlled by air exchange through the entrance and heat-moisture transfer from surrounding rock or soil36,37. In large underground spaces, environmental stability generally increases with distance from the entrance8,38. At Qinling Tomb, door openings were the dominant factor driving fluctuations in temperature and humidity (Fig. 6), confirming that airflow at the entrance was the principal source of environmental instability. To address this, an automated door system and a temperature–humidity-controlled buffer space were implemented. These measures effectively reduced air exchange and minimized hygrothermal fluctuations in the tomb (Fig. 5), demonstrating the critical role of buffer spaces in stabilizing tomb microclimates.

Moisture is widely recognized as a primary agent of deterioration in porous materials39. Repeated wet-dry cycles induced by environmental fluctuations reduce fracture toughness40,41, and condensation, a key source of moisture, triggers fungal spore germination and growth12,13,14. In Qinling Tomb, condensation was mainly observed on ceiling and back chamber surfaces during summer. This phenomenon is primarily caused by the ingress of hot, humid outdoor air, which condenses upon contact with the cooler interior wall surfaces32. To reduce moisture ingress, the door openings were reduced to limit air exchange with the external air. Simultaneously, air conditioning and dehumidifiers in the buffer space cooled and dried the incoming air, thereby reducing its absolute humidity. As a result, the condensation coverage decreased by 78% following the implementation of regulatory measures (Fig. 10). The low interior air temperature maintained relative humidity levels near 100%, despite a reduction in absolute humidity following the intervention. Since condensation correlates linearly with water vapor content difference, the lower absolute humidity difference limited the phase transition from vapor to liquid42. In winter, localized condensation was observed on the ceiling in the entrance chamber, consistent with patterns observed in the Gaya tomb (Goa-ri, Goryeong-gun, Republic of Korea)43. This was attributed to increased absolute humidity and the presence of thermal bridges at the entrance. To further reduce this risk, supplementary measures such as heated glass doors44 or improved insulation should be considered.

Before the implementation of environmental control, salt crystallization in Qinling Tomb showed clear seasonal variation, with significant accumulation in the entrance and front chambers during winter. Sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄), the dominant soluble salt in Qinling Tomb and among the most damaging to porous substrates6,45,46, undergoes crystallization that is highly sensitive to microclimatic variations, causing frequent phase transitions under fluctuating temperature and humidity47. Salt transport and accumulation on murals are primarily driven by moisture fluctuations originating from two sources: natural ventilation of humid or dry air, and capillary rise of soil moisture due to rainfall and groundwater. Nanjing is characterized by high annual precipitation and shallow groundwater levels. Due to the deep burial of Qinling Tomb, the surrounding soil maintains a high water content. During winter, the ingress of cold, dry outdoor air causes a marked decrease in indoor relative humidity, and a vapor pressure gradient forms between the walls and the interior air, driving continuous moisture evaporation from the walls. This evaporation facilitates the migration and crystallization of soluble salts on mural surfaces. Compared with January 2021, environmental control measures maintained indoor relative humidity above 90% in January 2022, reducing surface evaporation and limiting salt migration, which led to an ~80% decrease in salt crystallization coverage. Additionally, the risk of sodium sulfate phase transitions driven by temperature and humidity fluctuations was substantially reduced. This strategy aligns with established conservation strategies for earthen heritage, where maintaining high humidity delays salt crystallization and reduces cracking risks48,49.

Microbial growth presents another threat to tomb murals. Before environmental control, microbial proliferation in Qinling Tomb was primarily localized to illuminated walls and gradually increased over time32, reflecting the stimulatory effect of light on microbial activity50,51. This highlights the importance of careful consideration of lighting design and duration in heritage conservation. During environmental control, relative humidity remained above 80%, a level generally favorable for microbial growth; however, no significant spread of microbial colonization was observed, with activity still restricted to areas near light sources. Microbial proliferation depends on multiple environmental factors. While high relative humidity supports microbial viability, the presence of liquid water—particularly from surface condensation—is often essential to trigger fungal spore germination and growth12,13,14. The implemented interventions effectively reduced condensation coverage. Although the relative humidity remained high after interventions, the decrease in air temperature lowered the absolute humidity, thereby limiting water vapor condensation. The long-term behavior of microbial communities under these regulated conditions remains uncertain. Therefore, continued monitoring is crucial to detect microbial shifts, and to evaluate the sustained effectiveness of environmental control strategies.

The in-situ environmental control experiments at Qinling Tomb validate buffer space as an effective tool for reducing salt crystallization and condensation, offering practical reference for other tombs in humid climates. Seasonal environmental control strategies are proposed as follows:

-

(1)

Winter (November–March): Minimize door openings to reduce external air intrusion, stabilize the microclimate, and control salt crystallization.

-

(2)

Summer (June–August): Minimize door opening during peak temperature and humidity, and simultaneously operate air conditioning and dehumidifiers in the buffer space to cool and dry the incoming air, thereby preventing condensation.

-

(3)

Transitional seasons (April–May, September–October): Allow controlled natural ventilation when indoor and outdoor conditions are comparable.

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of buffer space interventions in stabilizing the microclimate of an open tomb in a humid region. Over two years of implementation, the system significantly reduced hygrothermal fluctuations—temperature and relative humidity ranges decreased by ~60% and 40%, respectively—while areas affected by winter salt crystallization and summer condensation declined by around 80%. To enhance performance, operational strategies should further limit door openings during extreme seasons and enable controlled ventilation during transitional periods. Thermal bridging at the entrance requires improved insulation, and microbial activity should be continuously monitored to assess potential long-term risks.

The environmental control system effectively mitigates the risks of salt crystallization and condensation in open tombs located in humid regions through a hybrid passive-active regulation approach. This approach provides practical guidance for conserving the Two Tombs of the Southern Tang Dynasty and other vulnerable heritage sites exposed to similar microclimatic risks.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Wang, Y. & Wu, X. Current progress on murals: distribution, conservation and utilization. Herit. Sci. 11, 61 (2023).

Wu, H. The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs (University of Hawaii Press, 2015).

Hagage, M., Madani, A. A., Aboelyamin, A. & Elbeih, S. F. Urban sprawl analysis of Akhmim city (Egypt) and its risk to buried heritage sites: insights from geochemistry and geospatial analysis. Herit. Sci. 11, 174 (2023).

Qu, J., Sun, M., Wang, F., Liu, K. & Chen, L. Rising damp in heritage sites under urban expansion: a comprehensive case study of the Jinsha Earthen Site. Build. Environ. 265, 111971 (2024).

Dionis, C., Cristobal, M., Álvarez, N. & Yarasca-Aybar, C. Conservation of archaeological sites in the face of urban sprawl: the case of Independencia, Peru. Built Herit. 9, 36 (2025).

Flatt, R. J. Salt damage in porous materials: how high supersaturations are generated. J. Cryst. Growth 242, 435–454 (2002).

Zhang, Y., Cui, D., Liu, S., Li, B. & Guo, H. Types and sources of salts causing exfoliation and efflorescence in stone relics at Yongling Mausoleum. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 61 (2025).

Germinario, L. & Oguchi, C. T. Underground salt weathering of heritage stone: lithological and environmental constraints on the formation of sulfate efflorescences and crusts. J. Cult. Herit. 49, 85–93 (2021).

Shi, W. et al. Water vapor condensation prevention and risk rating evaluation based on Yang Can’s tomb. Herit. Sci. 12, 178 (2024).

Martin-Pozas, T. et al. Microclimate, airborne particles, and microbiological monitoring protocol for conservation of rock-art caves: the case of the world-heritage site La Garma cave (Spain). J. Environ. Manag. 351, 119762 (2024).

Becherini, F., Bernardi, A. & Frassoldati, E. Microclimate inside a semi-confined environment: valuation of suitability for the conservation of heritage materials. J. Cult. Herit. 11, 471–476 (2010).

Pasanen, P., Pasanen, A.-L. & Jantunen, M. Water condensation promotes fungal growth in ventilation ducts. Indoor Air 3, 106–112 (1993).

Pasanen, A. L., Kalliokoski, P., Pasanen, P., Jantunen, M. J. & Nevalainen, A. Laboratory studies on the relationship between fungal growth and atmospheric temperature and humidity. Environ. Int. 17, 225–228 (1991).

Lax, S. et al. Microbial and metabolic succession on common building materials under high humidity conditions. Nat. Commun. 10, 1767 (2019).

Gogoleva, N. et al. Microbial tapestry of the Shulgan-Tash cave (Southern Ural, Russia): influences of environmental factors on the taxonomic composition of the cave biofilms. Environ. Microbiomes 18, 82 (2023).

Li, Y., Huang, Z., Petropoulos, E., Ma, Y. & Shen, Y. Humidity governs the wall-inhabiting fungal community composition in a 1600-year tomb of Emperor Yang. Sci. Rep. 10, 8421 (2020).

Maekawa, S. in Art and Eternity: The Nefertari Wall Paintings Conservation Project, 1986-1992 (eds Corzo, M. A. & Afshar, M. Z.) 105–121 (The Getty Conservation Institute, 1993).

Wong, L. et al. Improving environmental conditions in the tomb of Tutankhamen. Stud. Conserv. 63, 307–315 (2018).

Li, Y., Ogura, D., Hokoi, S. & Ishizaki, T. Effects of emergency preservation measures following excavation of mural paintings in Takamatsuzuka Tumulus. J. Build. Phys. 36, 117–139 (2012).

Li, Y. H., Ogura, D., Hokoi, S., Wang, J. G. & Ishizaki, T. Predicting hygrothermal behavior of an underground stone chamber with 3-D modeling to restrain water-related damage to mural paintings. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 13, 499–506 (2014).

Wu, F. et al. Review of microbial deterioration and control of Takamatsuzuka Tumulus, Japan. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 31, 26–35 (2019).

Caneva, G., Isola, D., Lee, H. J. & Chung, Y. J. Biological risk for hypogea: shared data from Etruscan tombs in Italy and ancient tombs of the Baekje Dynasty in Republic of Korea. Appl. Sci. 10, 6104 (2020).

Kim, S. H. & Lee, C. H. Interpretation on internal microclimatic characteristics and thermal environment stability of the royal tombs at Songsanri in Gongju, Korea. J. Conserv. Sci. 35, 99–115 (2019).

Saiz-Jimenez, C. et al. Paleolithic art in Peril: policy and science collide at Altamira Cave. Science 334, 42–43 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Tourists visiting impact on microclimate and the risk analysis of Wei-Jin dynasty tombs, Jiayuguan, China. J. Earth Environ. 8, 347–366 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Impact of the visitor walking speed and glass barriers on airflow and bioaerosol particles distribution in the typical open tomb. Build. Environ. 225, 109649 (2022).

Havlena, Z., Kieft, T. L., Veni, G., Horrocks, R. D. & Jones, D. S. Lighting effects on the development and diversity of photosynthetic biofilm communities in Carlsbad Cavern, New Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e02695–02620 (2021).

Bruno, L. & Valle, V. Effect of white and monochromatic lights on cyanobacteria and biofilms from Roman Catacombs. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 123, 286–295 (2017).

Gu, W. et al. Polyacrylic acid-functionalized graphene@Ca(OH)2 nanocomposites for mural protection. ACS Omega 7, 12424–12429 (2022).

Fang, X. et al. Characterization, property and application of silicone acrylic emulsion as a kind of protection material for murals. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 40, 1004–1016 (2023).

Gomoiu, I. et al. The susceptibility to biodegradation of some consolidants used in the restoration of mural paintings. Appl. Sci. 12, 7229 (2022).

Xia, C. et al. Spatial and temporal changes in microclimate affect disease distribution in two ancient tombs of Southern Tang Dynasty. Heliyon 9, e18054 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Temperature and moisture gradients drive the shifts of the bacterial microbiomes in 1000-year-old mausoleums. Atmosphere 14, 14 (2023).

Matsumoto, M., Hokoi, S. & Hatano, M. Model for simulation of freezing and thawing processes in building materials. Build. Environ. 36, 733–742 (2001).

Xia, C. et al. Impact of Entrance Air Exchange on Hygrothermal Environment and Mural Deterioration Risk of an Ancient Tomb. In Proceedings of the 9th International Building Physics Conference (IBPC 2024) (ed Berardi, U.) 35–41 (Springer, 2025).

Zhang, Y. & Wang, Y. Maintenance schedule optimization based on distribution characteristics of the extreme temperature and relative humidity of Cave 87 in the Mogao Grottoes. Herit. Sci. 11, 158 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. The impact of cave opening and closure on murals hygrothermal behavior in Cave 98 of Mogao Caves, China. Build. Environ. 256, 111502 (2024).

Xiong, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal variation characteristics and influencing factors of Karst Cave microclimate environments: a case study in Shuanghe Cave, Guizhou Province, China. Atmosphere 14, 813 (2023).

Li, Y. H. & Gu, J. D. A more accurate definition of water characteristics in stone materials for an improved understanding and effective protection of cultural heritage from biodeterioration. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 166, 8 (2022).

Dehestani, A., Hosseini, M. & Beydokhti, A. T. Effect of wetting-drying cycles on mode I and mode II fracture toughness of sandstone in natural (pH=7) and acidic (pH=3) environments. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 107, 102512 (2020).

Linan, C. et al. Condensation water in heritage touristic caves: Isotopic and hydrochemical data and a new approach for its quantification through image analysis. Hydrol. Process. 35, e14083 (2021).

Wei, L., Wang, P., Chen, X. & Chen, Z. Water vapor condensation behavior on different wetting surfaces via molecular dynamics simulation. Surf. Interfaces 52, 104981 (2024).

Jeong, S. H., Lee, H. J., Lee, M. Y. & Yongjae, C. Conservation environment for mural tomb in Goa-ri, Goryeong. J. Conserv. Sci. 33, 189–201 (2017).

Zhang, B. & Lin, G. Try of “Gas Phase Humidification—Wet Protection” at Wet Environmental Soil Sites —Strategy and Engineering Practice of Wangjing Gate City Wall Site in Ningbo. Res. Conserv. Cave Temples Earthen Sites 1, 80–87 (2022).

Benavente, D., del Cura, M. A. G., García-Guinea, J., Sánchez-Moral, S. & Ordóñez, S. Role of pore structure in salt crystallisation in unsaturated porous stone. J. Cryst. Growth 260, 532–544 (2004).

Schiro, M., Ruiz-Agudo, E. & Rodriguez-Navarro, C. Damage mechanisms of porous materials due to in-pore salt crystallization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 265503 (2012).

Steiger, M. & Asmussen, S. Crystallization of sodium sulfate phases in porous materials: the phase diagram Na2SO4–H2O and the generation of stress. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 4291–4306 (2008).

Chang, B., Li, J., Li, K., Luo, X. & Gu, Z. Prevention of dry cracking of excavated earthen sites at Han Yangling Museum using ultrasonic wetting. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 19, 216–232 (2023).

Chang, B., Shen, C., Luo, X., Hu, T. & Gu, Z. Moisturizing an analogous earthen site by ultrasonic water atomization within Han Yangling Museum, China. J. Cult. Herit. 66, 294–303 (2024).

Bao, Y. et al. Innovative strategy for the conservation of a millennial mausoleum from biodeterioration through artificial light management. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 69 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Unearthing lights-induced epilithic bacteria community assembly and associated function potentials in historical relics. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 186, 105701 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by the National Key R&D Program (Grant No. 2019YFC1520700) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278013). We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Cultural Heritage Conservation and Management Office of the Two Tombs of the Southern Tang Dynasty.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C.X.: Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Writing Original Draft, Writing Review & Editing; Z.Y.K.: Investigation, Visualization; B.M.S.: Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition; H.R.X.: Formal analysis, Writing Review & Editing; B.G. M.: Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition; S. H.: Methodology, Writing Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition; Y.H. L.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, C., Kong, Z., Su, B. et al. Tomb murals conservation in humid regions: hybrid passive-active systems for salt crystallization and condensation mitigation. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 570 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02115-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02115-w