Abstract

The visual identity of Chinese intangible cultural heritage (ICH) relies on structured composition and symbolic color traditions. We present Colorful Heritage, a structure- and color-aware generative framework for stylizing ICH visual forms with cultural fidelity. Our method integrates: (1) a structure-guided stylization module encoding principles such as axial symmetry; (2) a color-aware embedding mechanism for symbolic palette modeling; and (3) a disentangled two-stage training strategy to separate content from style. To support evaluation and future research, we introduce ICHStyleBench, a benchmark of 10 ICH styles—including paper cutting, clay sculpture, and embroidery—annotated with layout and color attributes. Both quantitative analysis and expert evaluations confirm that our method achieves superior performance in semantic integrity, visual symbolism, and compositional structure preservation, with scores of 84.6 in content preservation, 81.2 in style alignment, 0.502 in CLIP-S, and a user preference rate of 34.5%, significantly higher than all baselines. This work provides a computational contribution to the digital preservation and revitalization of intangible cultural heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) constitutes a vital dimension of the global cultural heritage ecosystem. Encompassing oral traditions, traditional craftsmanship, ritual practices, and performing arts, ICH represents cultural expressions transmitted across generations and deeply embedded within community life1,2. These practices are often inseparable from specific spaces, social rituals, and tangible artifacts that give them contextual meaning. Characterized as a—living heritage,—ICH is sustained through oral transmission, everyday enactment, and intergenerational interaction3,4. It embodies human creativity, experiential knowledge, and collective memory, serving as a dynamic link between the past and the present. However, amid accelerating urbanization and shifting sociocultural structures, many ICH practices are facing increasing threats—ranging from intergenerational discontinuity and contextual displacement to the erosion and distortion of traditional forms5,6. The significance of ICH extends far beyond preservation or museum display. It plays an irreplaceable role in shaping cultural identity, fostering creativity, and reinforcing social cohesion7,8. As a shared cultural resource, ICH also carries the contemporary mandate of promoting intercultural understanding, sustaining historical continuity, and advancing cultural innovation. In this context, digital revitalization and creative reinterpretation have emerged as critical strategies for safeguarding ICH9—enabling its transmission, accessibility, and meaningful renewal in the digital era.

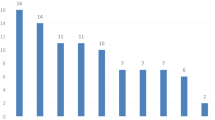

Within China’s official classification of ICH, the styles of traditional art and traditional skills occupy a prominent position due to their strong visual expressiveness, distinctive compositional norms, and dense symbolic encoding10. As of 2025, 426 items in these styles have been recognized at the national level—accounting for approximately 27% of all registered ICH entries—and include practices, such as woodblock New Year pictures, paper cutting, embroidery, clay figurines, lantern art, and bamboo weaving. A total of 1230 national-level representative inheritors have been identified, supporting an institutional safeguarding system and a regionally distributed transmission network. These visual traditions are rich in cultural semantics and stylistic diversity. For example, Miao paper-cutting and textile patterns integrate religious belief with layered chromatic motifs; regional variations of New Year pictures exhibit striking differences—Zhuxian Town emphasizes compositional rhythm, Tantou favors abstraction and saturation, while Yangliuqing and Taohuawu are known for fine brushwork and ornate detail11.

Beyond surface appearance, Chinese ICH visual forms encode meaning through layout and color. Axial or bilateral symmetry and framed, center-axis compositions are widely used in woodblock New Year pictures and palace lantern designs to convey ritual order, balance, and auspicious harmony. Paper cutting often organizes figures along vertical or radial axes to signal narrative hierarchy (central deities, guarding animals, or ancestral motifs), while embroidery composes paired or mirrored motifs to express blessing and protection. Color choices are likewise symbolic rather than merely aesthetic: for example, vermilion is associated with festivity and auspiciousness in celebratory prints and paper cuttings; golden/yellow signifies dignity and authority in ceremonial objects; and indigo/blue is linked to serenity and protection in textiles and folk ornaments. Because these cultural semantics are carried by compositional structure (where things are placed) and chromatic coding (how they are colored), faithful stylization requires models that explicitly reason about layout priors and symbolic palettes, rather than optimizing only for generic perceptual similarity. Similarly, cloth tiger figurines across regions embody the interplay between local iconography, spiritual systems, and practical function. Yet, despite their visual richness, these styles present inherent modeling challenges: they lack standardized structural templates, display significant interregional variation, and encode semantic meaning through highly context-dependent visual cues. General-purpose AI models struggle to learn and reproduce such complex traditions through conventional classification or low-level feature matching alone12. To address this, we construct a structured image dataset focused on traditional art-related ICH items, annotated across multiple dimensions, such as regional origin, composition layout, theme, and symbolic color usage. This resource facilitates more interpretable style learning and culturally faithful generation, laying the groundwork for semantic perception, structural control, and the digital revitalization of visual ICH. Rather than replacing human-centered creative practice, our framework offers a computational perspective to support documentation, interpretation, and inclusive cultural representation in generative systems.

While the transmission of ICH fundamentally relies on human creativity and intergenerational practice, computational approaches can serve as complementary tools for cultural analysis and visual encoding. Rather than aiming to replace artisanal expression, generative models can aid in the systematic study and digital revitalization of heritage esthetics, particularly when traditional knowledge risks fragmentation due to modernization and demographic shifts.

In response to the dual challenges of structural complexity and intergenerational disruption in image-based ICH preservation, generative AI and computational modeling have emerged as promising tools for cultural expression, reinterpretation, and sustainable transmission13. Recent studies have demonstrated that techniques such as semantic feature extraction, image clustering, and style-guided generation can transform unstructured ICH visual data into structured knowledge representations, paving the way for controllable and interpretable generative models. For instance, in the study of Guizhou batik ICH, researchers constructed hierarchical visual knowledge graphs using clustering and edge feature extraction to enable automatic motif classification and semantic-aware generation14. In another line of work, Peking Opera facial makeup styles were synthesized through an extended StyleGAN2 framework equipped with co-training and conditional control modules, enabling multi-style fusion and culturally coherent generation15. These examples illustrate the growing feasibility of applying generative models to ICH visual reconstruction. More importantly, they highlight the need for stylization systems that go beyond surface-level transfer—embedding structural reasoning, symbolic color representation, and cultural context into the generative process. Accordingly, designing a generative framework that can incorporate the compositional logic and chromatic symbolism inherent in ICH imagery, while maintaining cultural sensitivity, has become a central challenge in the digital transformation of intangible heritage. While our framework centers on visual semantics, related heritage studies, such as Li et al.16, underscore that visual motifs often encode deeper kinship-based, ritualistic, and spiritual meanings. These insights highlight the broader cultural functions of visual forms and point to opportunities for future extensions beyond visual stylization.

Recent advances in diffusion-based text-to-image generation17,18 and fine-tuning techniques, such as DreamBooth19, LoRA20, and Textual Inversion21 have enabled the efficient adaptation of pretrained models to user-specific styles or concepts. In particular, LoRA-based methods22,23,24 have shown effectiveness in style transfer by injecting low-rank learnable weights into selected attention layers. However, most existing approaches target generic or Western art domains and overlook the compositional complexity and symbolic color semantics inherent in non-Western cultural traditions.

Recent works, such as ZipLoRA22 and B-LoRA24 have explored LoRA factor placement and modular merging for style disentanglement. Nevertheless, they tend to optimize for perceptual similarity and do not incorporate culturally grounded priors, such as layout symmetry or symbolic color usage. Similarly, tuning-free approaches using adapters25,26 accelerate inference but offer limited interpretability and cultural control. While prior cultural stylization works27,28 contribute valuable datasets or color harmony tools, they typically do not embed symbolic structure within the generative process.

Existing generative approaches, although effective for Western or general art domains, remain limited in capturing the compositional and chromatic logic characteristic of non-Western cultural imagery. Most style transfer and diffusion-based frameworks focus on aesthetic resemblance or perceptual alignment, without considering structural regularities, such as axial symmetry, hierarchical framing, or ritual balance that govern traditional Chinese art forms. Likewise, color modeling in these methods is largely data-driven, neglecting the hierarchical symbolism embedded in traditional palettes—where hues, such as vermilion, indigo, and gold, convey spiritual and social meanings beyond visual harmony. These limitations constrain the interpretability and cultural fidelity of ICH stylization when applied, underscoring the need for a framework that integrates culturally grounded priors into both structural and chromatic dimensions.

In contrast, we introduce Colorful Heritage, a structure- and color-aware stylization framework that explicitly models cultural semantics through structure-aware LoRA training and symbolic color injection. This design is informed by both the technical landscape of efficient adaptation and the domain-specific requirements of ICH image synthesis. Our method integrates three core modules: First, we develop a structure-guided LoRA module that integrates traditional layout priors, such as symmetry, radial flow, and diagonal alignment, into the adaptation process. This design ensures that the generated images not only adopt the surface textures of traditional art but also embody their spatial logic and compositional harmony, a crucial yet often overlooked aspect of cultural authenticity. Second, we introduce a color-aware stylization module that encodes color distributions derived from symbolic palettes, such as vermilion, indigo, and gold, into compact chromatic tokens. These tokens are injected during generation to steer the model toward stylistically consistent and semantically meaningful color usage, significantly improving the chromatic fidelity and expressiveness of stylized outputs. Third, we propose a semantic disentanglement training strategy, which employs a two-stage LoRA adaptation scheme guided by style prompts and cultural tags. This strategy enables clean separation between content and style representations, thereby reducing content leakage and enhancing controllability across diverse cultural styles. It also facilitates modular reuse of learned components, allowing efficient generalization to new styles with minimal supervision. Unlike prior LoRA-based diffusion approaches that primarily focus on general aesthetic decomposition and perceptual alignment, our framework introduces a culturally grounded modeling perspective. By embedding symbolic color semantics and compositional layout logic as learnable modules, we enable semantically controllable and culturally faithful generation tailored to the unique visual characteristics of ICH. Although built upon standard diffusion architectures, our formulation contributes a new abstraction layer that incorporates cultural reasoning into the generative process.

In addition, we curate ICHStyleBench, a benchmark dataset featuring various representative styles from Chinese ICH—including woodblock New Year pictures, clay sculpture, and traditional tie-dye—as well as different styles of cultural and creative product images used as content. Each style entry is annotated with detailed metadata, including compositional structure, thematic origin, symbolic color motifs, and culturally grounded visual descriptors. Comprehensive evaluations—both qualitative and quantitative—demonstrate that Colorful Heritage not only surpasses state-of-the-art stylization models22,24,25 in terms of structural and chromatic alignment, but also offers interpretability, visual quality, and cultural coherence valuable for the digital preservation and creative reuse of intangible visual heritage. Moreover, the visual forms used in ICH stylization are often historically embedded in broader social and transregional dynamics. For instance, export-oriented decorative arts in the Qing dynasty reflect influences from maritime trade, consumer tastes, and cross-cultural symbolism29. While our current focus remains on visual style modeling (layout and symbolic color), future work may benefit from integrating such socio-historical insights to enhance interpretive fidelity.

Methods

Our method, Colorful Heritage, is designed to generate culturally faithful stylizations that retain the structural layout and color characteristics of the exemplar, specific to Chinese ICH. This section presents the overall architecture and the core technical components. We begin by introducing the latent diffusion backbone and the LoRA-based adaptation strategy. Then, we describe three key modules that form the foundation of our framework: structure-guided stylization, color-aware stylization, and a two-stage semantic disentanglement strategy. These components collectively enable our framework to achieve semantically grounded, structurally aligned, and chromatically coherent stylizations tailored to ICH visual forms.

Latent diffusion for stylization

Latent diffusion models (LDMs)17 have emerged as a powerful paradigm for efficient image generation and stylization. Instead of operating in the high-dimensional pixel space, LDMs learn to denoise in a compressed latent space obtained via an autoencoder. Given an image x, the encoder \({\mathcal{E}}\) maps it to a latent representation \({z}_{0}={\mathcal{E}}(x)\), and a decoder reconstructs the image as \({\mathcal{D}}({z}_{0})\approx x\). A Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM)30 is trained to learn the reverse denoising process in this latent space, which is computationally more efficient and has become standard in stylization tasks25,31,32.

A key design choice in diffusion training is the form of the supervision objective. Let zt denote the noisy latent obtained by perturbing z0 with Gaussian noise at timestep t. The model may be trained to predict either the noise ϵ added to the latent or the original clean latent z0. This yields two common objective formulations:

where ϵθ is the noise prediction network, and \({\tilde{z}}_{0}\) is reconstructed from ϵθ(zt, t) using the reverse diffusion equation. While \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{\epsilon }\) is widely used due to its stability and visual diversity, it tends to emphasize low-level noise details and may neglect high-level structure, often resulting in style inconsistency and content distortion.

To better preserve the global layout and semantic fidelity—especially important for culturally structured stylization—we adopt \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{x}_{0}}\) as our supervision objective. It directly encourages the recovery of clean content structure and improves alignment between content and style, all without modifying the architecture of the diffusion model.

LoRA-based adaptation

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)20 has emerged as a powerful tool for efficiently adapting large models to new tasks. In the context of diffusion stylization, LoRA modules are typically injected into transformer blocks within the U-Net33 to capture task-specific variations while keeping the base model frozen. Prior works22,23,24 show that style and content can be decoupled by optimizing separate LoRA branches. However, most of these approaches use ϵ-prediction as the loss function and do not leverage cultural priors in structure or color.

In contrast, our method utilizes x0-based supervision to improve structural coherence, and introduces layout-guided and color-aware LoRA modules for enhanced cultural stylization. Additionally, we propose a two-stage training strategy to further disentangle content and style representations.

Algorithm 1

Two-stage semantic disentanglement for stylization

Require: Content image Ic, Style image Is, Structure label ls, Color palette \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{s}\)

Ensure: Content LoRA θc, Style LoRA θs

1: Stage I: Train Content LoRA

2: Encode Ic: \({z}_{0}^{c}={\mathcal{E}}({I}_{c})\)

3: for each training step do

4: Sample timestep t, noise \(\epsilon \sim {\mathcal{N}}(0,I)\)

5: \({z}_{t}^{c}=\sqrt{{\bar{\alpha }}_{t}}{z}_{0}^{c}+\sqrt{1-{\bar{\alpha }}_{t}}\cdot \epsilon\)

6: Predict noise \({\epsilon }_{\theta }({z}_{t}^{c},t)\)

7: Update θc using \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{content}}}={\left\Vert {z}_{0}^{c}-{\tilde{z}}_{0}({z}_{t}^{c},t)\right\Vert }_{2}^{2}\)

8: end for

9: Stage II: Train Style LoRA (freeze θc)

10: Encode structure token estruct = Embedstruct(ls)

11: Encode color token \({e}_{{\rm{color}}}={{\rm{Embed}}}_{{\rm{color}}}({{\mathcal{C}}}_{s})\)

12: Encode Is: \({z}_{0}^{s}={\mathcal{E}}({I}_{s})\)

13 for each training step do

14: Sample timestep t, noise ϵ, compute \({z}_{t}^{s}\)

15: Predict noise with estruct, ecolor

16: Update θs using \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{style}}}={\left\Vert {z}_{0}^{s}-{\tilde{z}}_{0}({z}_{t}^{s},t;{e}_{{\rm{struct}}},{e}_{{\rm{color}}})\right\Vert }_{2}^{2}\)

17: end for

Algorithm 2

Stylization inference with content and style LoRA

Require: Content image Ic, Structure label ls, Color palette \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{s}\)

Require: Trained LoRA weights θc, θs; guidance weights λcontent, λstyle

Ensure: Stylized output image \(\hat{x}\)

1: Encode Ic into latent space: \({z}_{0}^{c}={\mathcal{E}}({I}_{c})\)

2: Sample timestep t and noise ϵ

3: Generate noisy latent: \({z}_{t}^{c}=\sqrt{{\bar{\alpha }}_{t}}{z}_{0}^{c}+\sqrt{1-{\bar{\alpha }}_{t}}\cdot \epsilon\)

4: Load content LoRA θc and style LoRA θs into frozen base model

5: Embed structure token: estruct = Embedstruct(ls)

6: Embed color token: \({e}_{{\rm{color}}}={{\rm{Embed}}}_{{\rm{color}}}({{\mathcal{C}}}_{s})\)

7: Predict:

8: Compose guided prediction:

9: Run reverse DDIM to obtain stylized latent \({\hat{z}}_{0}\)

10: Decode stylized image: \(\hat{x}={\mathcal{D}}({\hat{z}}_{0})\)

Structure-guided stylization

A key visual characteristic of Chinese ICH lies in its symbolic spatial composition. Common layout forms, such as axial symmetry (e.g., door gods), radial patterns (e.g., palace lanterns), and diagonal balance (e.g., calligraphy scrolls) reflect deep-rooted esthetic principles. However, existing diffusion-based stylization methods22,25 primarily focus on low-level texture or color patterns and often fail to reproduce such spatial regularities, resulting in outputs that appear stylistically inconsistent or compositionally chaotic. Beyond axial symmetry, our structure prior is defined over a compact taxonomy that covers radial, diagonal, and balanced asymmetry layouts commonly observed in ICH (e.g., rosette-like palace lanterns for radial, slanted scroll compositions for diagonal, and embroidery motifs for balanced asymmetry). These categories are detected either by lightweight symmetry cues (reflection, rotational energy in polar coordinates) and principal-orientation histograms or by manual tags when curatorial metadata is available.

To address this, we introduce a structure-guided stylization module that injects explicit layout priors into the LoRA adaptation process. By incorporating structure tokens derived from geometric attributes of the style image, we guide the model to produce stylized results that respect traditional spatial logic while preserving content alignment. This design explicitly injects non-axial priors (radial/diagonal/balanced asymmetry) into LoRA adaptation rather than relying on texture-only cues.

We manually annotate each style image with a discrete layout label \(l\in {\mathcal{L}}\), where \({\mathcal{L}}\) includes common compositional styles, such as axial symmetry, radial symmetry, diagonal layout, and asymmetric freeform. These labels can also be inferred using image symmetry detectors or low-level structural heuristics.

Each layout label l is mapped to a learnable structure token \({e}_{{\rm{struct}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\), which serves as a conditioning vector during LoRA training. Specifically, we inject this token into the cross-attention layers of the U-Net via a lightweight embedding layer:

and modify the attention computation as:

where Wbias is a linear projection that transforms the structure token into an attention bias term. This allows the model to incorporate spatial composition priors directly into the generation process.

During style LoRA training (see Section 2), we condition the model on both the style image and its associated structure token. The training objective for structure-aware stylization becomes:

where \({z}_{0}^{s}\) and \({z}_{t}^{s}\) are the clean and noisy latents of the style image, and estruct guides the model to reconstruct \({z}_{0}^{s}\) with spatial awareness. The trained LoRA thereby learns to encode not only appearance features but also structural esthetics.

At inference time, users can optionally select or interpolate between structure tokens to control the spatial characteristics of stylization. This provides intuitive and culture-aligned controllability, enabling stylized results that adhere to traditional layout conventions.

While both our method and B-LoRA24 leverage external conditioning to guide LoRA adaptation, the nature of the conditioning signals is fundamentally different. B-LoRA conditions on textual style descriptions during fine-tuning but does not explicitly encode or supervise visual structure. In contrast, our structure-aware module extracts layout features, such as axial symmetry and motif alignment, from the reference image, and embeds these as learnable structure tokens that condition a dedicated LoRA branch. This visual tokenization introduces direct compositional priors into the generation process, enabling finer preservation of culturally specific spatial structures that are difficult to convey through text alone.

Color-aware stylization

Color in Chinese ICH carries deep cultural and symbolic meaning. Specific colors, such as vermilion, gold, or indigo, are not merely aesthetic choices but reflect philosophical and societal values. Existing stylization methods often treat color as a byproduct of texture matching or CNN feature alignment, without explicit control or understanding of its semantic role. This often leads to inaccurate or overly diluted color usage, which undermines the cultural integrity of the generated image.

To address this, we propose a color-aware stylization module that explicitly encodes and injects symbolic color priors into the generation process. By guiding LoRA adaptation with chromatic tokens extracted from the style image, our method promotes faithful and semantically aligned color transfer. To ensure that the extracted colors correspond to culturally meaningful symbolism rather than purely statistical distributions, we construct a curated symbolic lexicon derived from authoritative ICH documentation and ethnographic literature. Each dominant hue detected in CIELAB space is mapped to this lexicon (e.g., vermilion for auspiciousness, indigo for calmness, gold for prosperity), conditioned on project metadata, such as motif type and ritual context. Ambiguous hues are cross-checked by domain experts to confirm their symbolic roles. We further verify the validity of these mappings through motif-color co-occurrence analysis (e.g., vermilion co-appearing with New Year motifs and gold with ceremonial ornaments). This procedure ensures that the color tokens capture not only perceptual similarity but also culturally encoded semantic meaning.

For each style image Is, we extract a palette of K dominant colors using k-means clustering in the CIELAB color space, which better reflects perceptual differences than RGB. The result is a color palette \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{s}=\{{c}_{1},{c}_{2},...,{c}_{K}\}\), where each \({c}_{k}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) represents a cluster centroid. While k-means offers a computationally efficient way to extract representative color clusters, it assumes spherical cluster distributions and may not fully capture the perceptual harmony and symbolic alignment of traditional palettes. We acknowledge this limitation and regard our current strategy as a practical approximation; more perceptually grounded palette modeling (e.g., CIEDE2000-aware or learning-based color grouping) remains an important direction for future refinement.

The extracted color palette is embedded into a learnable token vector:

which is injected into the cross-attention layers of the U-Net. Similar to the structure token, this token biases attention computations to steer generation toward the target chromatic distribution.

During LoRA training on the style image, we incorporate the chromatic token ecolor into the network and supervise the model to reconstruct the style latent \({z}_{0}^{s}\) under color guidance. The color-aware loss is defined as:

This objective ensures that the model learns a strong association between symbolic color and style features, enabling more vivid and semantically faithful stylizations.

At inference time, users can manipulate the influence of color by adjusting a guidance coefficient λcolor, following a classifier-free guidance formulation:

where ϵbase is the output of the model without color token, and ϵcolor is the output conditioned on ecolor. This allows for fine-grained control over the intensity of color transfer, providing flexibility to balance stylistic richness with content fidelity.

Two-stage semantic disentanglement

In many LoRA-based stylization methods22,24, content and style representations are learned simultaneously, often resulting in entangled features where the model fails to distinguish what to preserve (structure, semantics) and what to stylize (texture, color, layout). This entanglement is especially problematic in culturally complex styles, where symbolic structure and semantics are tightly coupled. To overcome this, we propose a two-stage semantic disentanglement strategy that sequentially optimizes content and style LoRA modules, thereby improving clarity, interpretability, and controllability in stylization.

In the first stage, we train a content LoRA module that focuses solely on preserving the semantic structure of the content image, independent of any style influence. The training objective is based on the x0-prediction loss defined over the content image Ic:

where \({z}_{0}^{c}={\mathcal{E}}({I}_{c})\) is the latent of the content image and \({z}_{t}^{c}\) is its noisy version. In this stage, no style or layout tokens are used, ensuring the content LoRA captures only structural and semantic priors of the original image.

After training the content LoRA, we freeze its parameters and train a separate style LoRA conditioned on structure and color tokens. Given a style image Is and its associated tokens estruct, ecolor, the training objective is defined as:

This enables the style LoRA to focus purely on stylistic elements, such as layout and color, while relying on the content LoRA for semantic reconstruction. The separation enhances clarity in the learned representations and avoids unintended content distortion.

To make the two-stage separation operational and robust, we specify the objectives and their weights explicitly. Stage 1 (content LoRA) emphasizes semantic and structural fidelity of the content image with three complementary signals: (i) an x0-reconstruction objective as the backbone supervision, (ii) a perceptual feature consistency loss computed on CLIP/VGG activations to preserve high-level semantics, and (iii) a lightweight edge/SSIM-aware term to stabilize geometric contours. The relative weights are set to 1.0 (reconstruction), 0.5 (perceptual), and 0.1 (edge) after a small validation sweep on 20 held-out content-style pairs. This stage uses no layout or color tokens, ensuring the content adapter learns structure/semantics only.

Stage 2 (style LoRA) focuses on culturally meaningful style adherence under frozen content LoRA. We combine: (i) the same x0-reconstruction objective (weight 1.0) to maintain training stability, (ii) a style similarity term based on Gram statistics over VGG activations (0.5) to capture texture and brushwork, (iii) a color alignment term in CIELAB that matches the generated image to the symbolic palette statistics extracted from the reference (0.3), and (iv) a layout-consistency term (0.2) that encourages attention patterns consistent with the structure token (e.g., axial, radial, and diagonal). Together, these losses steer the style adapter toward symbolic color usage and compositional faithfulness while avoiding overwriting content structure learned in Stage 1.

Weights were selected via a coarse grid search (±50% around the above values) on a 20-pair validation subset, optimizing for a composite score averaging ContentPres, StyleAlign, CLIP-S, and expert preference. We observed monotone trends: increasing the color term improves StyleAlign and expert judgments on symbolic palettes but can slightly reduce ContentPres beyond weight 0.4; increasing the layout term improves StyleAlign and ContentPres up to weight 0.25, after which gains saturate. Default inference coefficients are λcontent = 0.6 and λstyle = 0.8, with structure/color token guidance strengths set to 0.8/0.7, respectively. The model remains stable within a broad neighborhood of these settings, indicating that the disentanglement, rather than precise tuning, is the primary driver of gains.

At inference time, both content and style LoRA modules are loaded into the base model and applied simultaneously. The structure and color tokens serve as guidance signals to the style LoRA, while the content LoRA ensures faithful semantic preservation. Optionally, users can modulate the relative strength of each branch using coefficients λcontent and λstyle:

This provides intuitive control over the trade-off between fidelity and stylization, making the framework adaptable to various use cases. An overview of the two-stage training and inference process is illustrated in Figs. 1, 2. The detailed training and inference algorithms are provided in Alg. 1 and 2.

The training process consists of two stages: Stage I (top) learns a content-preserving LoRA module from the content image alone, focusing on semantic structure reconstruction via denoising. Stage II (bottom) learns a style-specific LoRA, guided by both structure and color tokens extracted from the style image. The structure token estruct encodes spatial layout priors (e.g., symmetry, composition type), while the color token ecolor embeds symbolic color palettes. Both are injected via token embedding layers into the style LoRA training pipeline.

During inference, both the content LoRA and the style LoRA are loaded into the base diffusion model. The content image is implicitly encoded via pre-trained semantic pathways (orange modules), while the structure token estruct and color token ecolor—extracted from the style prompt and palette—are injected through dedicated embedding layers. These tokens control the layout and chromatic characteristics of the generated image, enabling culturally faithful and composition-aware stylization.

While LoRA-based adapters are effective in low-rank parameter tuning, they often struggle to preserve semantic integrity in culturally symbolic domains due to the entangled nature of feature representations. To address this, our two-stage strategy first isolates structure-related priors (e.g., symmetry and spatial layout) before separately encoding symbolic color cues. This disentanglement not only reduces semantic leakage during generation but also ensures that culturally meaningful elements, such as auspicious color motifs or ritual-based layouts, are preserved in contextually appropriate ways. Our approach thus extends LoRA’s adaptation capacity from efficiency-focused tuning to culturally grounded controllability.

ICHStyleBench

To support research in stylization grounded in Chinese aesthetic principles, we introduce ICHStyleBench, a benchmark curated for evaluating structure-and culture-aware style transfer. It includes ten representative items selected from national-level Chinese ICH entries, focusing on visual crafts, such as New Year paintings, paper cutting, clay sculpture, embroidery, and palace lanterns.

The full benchmark consists of:

-

724 style images, manually curated and annotated;

-

4,345 symbolic color tokens extracted from style exemplars;

-

Stylization pairs for evaluation were constructed from 20 style images and 20 content images, yielding a total of 200 test pairs.

ICHStyleBench aggregates items from multiple provinces and both urban and rural contexts (e.g., county-level folk workshops and municipal museums), with project provenance recorded at the city/county level. For each style image, we additionally annotate whether it originates from festival/ritual settings (e.g., Spring Festival door-god prints, Dragon Boat Festival papercuts), workshop production, or museum/archival collections. When available, seasonal context (e.g., spring festival period vs. non-festive season) is recorded to reflect the cyclical nature of ICH practice. These attributes enrich downstream evaluation by enabling analysis across region, urban-rural origin, and ritual/seasonal usage.

Note that, while we visualize only a subset of ten styles and 20 content examples for clarity, all evaluations reported in this section are conducted over the 200 stylization pairs mentioned above. These pairs are sampled from the full benchmark, which additionally contains over 4000 training instances across diverse ICH substyles (see Fig. 3). The representative ICH styles analyzed in this study are summarized in Table 1, highlighting their compositional layouts, thematic connotations, and core visual keywords. A detailed summary of dataset coverage by region, historical period, project category, and source is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

This figure illustrates the hierarchical taxonomy and metadata schema of representative intangible cultural heritage (ICH) projects in Henan, categorized by artistic form: New Year Picture, Clay Sculpture, Paper Cutting, Embroidery, and Palace Lantern. Each style entry includes detailed project provenance (region, institution, and batch year), visual features, and the number of documented samples (N). On the right, four types of annotated metadata—pattern, modeling, process, and color—are illustrated. These metadata styles are not exclusive to any specific artistic form but are shared annotation dimensions applicable across different ICH styles. For example, both paper cutting and embroidery may contain animal patterns or geometric motifs, and all styles involve color characteristics, such as main color, decorative color, or traditional symbolic palettes. This structure supports a style-aware and interpretable modeling framework.

Each style image in ICHStyleBench is annotated with three key cultural dimensions: theme origin, compositional layout (e.g., axial symmetry, radial balance), and symbolic connotation (e.g., auspiciousness, loyalty and justice, home protection). These annotations enable structured evaluation of how well stylization methods preserve high-level cultural priors.

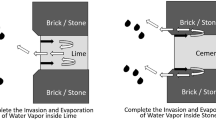

Color occupies a foundational role in traditional Chinese visual expression, often carrying deep symbolic meanings. To capture these chromatic conventions, we perform a palette-based color analysis on ten representative ICH styles from our dataset. For each style, we apply K-means clustering (guided by the elbow method) to extract five dominant colors from representative images. We then quantify the hue (H), saturation (S), and value (V) components of each cluster and visualize their relative proportions (Fig. 4). This analysis enables both perceptual and culturally-aligned evaluation of chromatic fidelity, and provides a foundation for symbolic color conditioning in our generative framework. The hierarchical relationships and color distributions among the ten representative ICH styles are visualized in Fig. 5, illustrating both the lineage and symbolic chromatic coherence within regional heritage practices.

This figure visualizes the symbolic color distribution of 10 representative traditional art ICH styles from Henan Province. For each item, we present its style, title, representative image, extracted dominant colors (Hex values), color cube representations (RGB), HSV decomposition, and the corresponding color proportion pie chart. The results are obtained via K-means clustering (optimal K = 5) on pixel values, highlighting perceptual dominance and compositional harmony. This quantification reveals the chromatic conventions and symbolic palettes embedded in various forms, such as New Year pictures, clay sculptures, paper cuts, lanterns, and embroidery.

This figure presents a radial taxonomy of ten representative ICH styles in Henan Province—such as paper cutting, palace lanterns, and embroidery—organized by their official classification. Each leaf node represents a specific sub-project, annotated with its dominant extracted color in HEX format. The hierarchical structure reflects cultural lineage, while the outer ring encodes symbolic color prevalence across different traditions. This visualization aids in analyzing both style taxonomy and chromatic symbolism within regional heritage practices.

The benchmark includes 20 content images curated from five culturally rich domains—namely, the Longmen Grottoes, Tang Dynasty court music, ancient bronzeware, Bai Juyi’s poetry, and traditional tea culture—spanning diverse semantic motifs and compositional styles to support style transfer tasks. While ICHStyleBench emphasizes visually codified crafts, it currently excludes non-visual styles such as oral traditions, performing arts, and musical heritage, which involve temporal and interactive modalities beyond static image stylization. Moreover, heritage forms with flexible or improvisational visual logic, such as freeform textile designs or abstract folk painting, are underrepresented compared to structured crafts like woodblock prints and paper cutting. These directions point to promising avenues for expanding the benchmark’s scope and cultural inclusivity in future work.

Results

Our implementation is based on SDXL v1.033, with both the model weights and text encoders frozen. The rank of LoRA weights is set to 64. All LoRAs are trained on a single image. For the content image, we initially train for 500 steps using ϵ-prediction, then switch to x0-prediction for an additional 1000 steps. For the style image, we first obtain its content LoRA using the above training strategy, and then separately train a new style LoRA for 1000 steps using x0-prediction. The entire training process takes approximately 12 minutes on a single 4090 GPU.

We compare our method with four state-of-the-art stylization methods, including StyleID25, StyleAligned34, ZipLoRA22, and B-LoRA24. For a fair comparison, we collect 20 content images and 20 style images from different studies19,24,25,31,35. Using these images, we compose 200 pairs of content and style images for quantitative evaluation.

Qualitative evaluation

We begin by qualitatively comparing our method with several state-of-the-art stylization approaches: StyleID25, StyleAligned34, ZipLoRA22, and B-LoRA24. Figure 6 shows representative examples of stylized outputs using different style references from Chinese ICH. Each example is composed of a content image (left) and a style reference (top), with the corresponding stylized results shown below. As illustrated, StyleID and StyleAligned often struggle with content degradation or overly generic stylistic features. ZipLoRA and B-LoRA offer improved content retention but may fail to capture high-level structural cues or symbolic color harmony. In contrast, our method Colorful Heritage excels in both semantic preservation and culturally faithful style transfer, accurately replicating traditional visual elements, such as symmetrical layout, auspicious motifs, and color symbolism. This superior content fidelity is not due to differences in backbone architecture—since all models use the same SDXL configuration—but rather arises from the disentangled adaptation design: our structure and color LoRA branches introduce domain-specific inductive biases that guide the generative process in a semantically aligned manner. Layout-aware tokens constrain spatial distortion, while chromatic guidance modulates stylistic transformation without eroding the core visual semantics of the content image.

Quantitative evaluation

We conduct a comprehensive quantitative evaluation comparing Colorful Heritage with four baseline methods on 200 stylization pairs. These pairs are constructed using 20 style exemplars selected from ten traditional ICH styles and 20 diverse content images drawn from our ICHStyleBench dataset. The evaluation is carried out using four metrics.

First, Content Preservation is assessed by measuring the L2 distance between image features extracted using a pre-trained CLIP model36, reflecting the fidelity of content retention. Second, Style Alignment is quantified via Gram-based similarity computed over activations from VGG-19, indicating how well the generated image aligns with the reference style. Third, we report the CLIP-S score, calculated as the CLIPScore37 between the textual style prompt and the generated image, to capture semantic consistency in the vision-language space. Finally, we include User Preference, determined by the percentage of human evaluators who favor each method in pairwise comparisons, offering a subjective but essential measure of perceptual quality.

To further assess the cultural fidelity of stylized results in Table 2, we conducted an expert-based analysis on key symbolic elements in Chinese ICH, including semantic motifs (e.g., guardian tigers, longevity peaches), color symbolism (e.g., red signifying festivity and auspiciousness, green representing vitality, and purple evoking solemnity or divine presence), and structural patterns (e.g., axial symmetry, diagonal layout). Each method’s outputs were reviewed by cultural researchers and rated along three axes: semantic accuracy, symbolic color reproduction, and compositional faithfulness. The evaluation revealed that Colorful Heritage significantly outperforms baselines in terms of semantic and cultural alignment. For example, in styles where color is semantically encoded, such as the use of red for auspicious celebration in New Year prints, or red for loyalty in Peking Opera masks—baseline methods often fail to preserve such cultural functions, producing visually plausible but semantically inappropriate results. In contrast, our method consistently reflects the intended symbolic meanings, thanks to its structure-guided LoRA and color-aware embedding, which explicitly encode layout and chromatic constraints grounded in domain-specific cultural priors.

To complement expert assessments, we further evaluate our method using Fréchet Inception Distance (FID; lower is better) and LPIPS (lower is better) on the 200-pair test set in Table 3. Compared with the strongest baseline (B-LoRA), our method achieves lower LPIPS and FID, indicating better perceptual quality and semantic coherence (LPIPS: 0.255 vs. 0.278; FID: 37.9 vs. 42.1). We also analyze the sensitivity to the style coefficient λstyle in Eq. 11 (fixing λcontent = 0.6). As λstyle increases, StyleAlign and CLIP-S improve, while ContentPres, LPIPS, and FID show a mild degradation, reflecting the expected trade-off between fidelity and stylistic richness. We set λstyle = 0.8 as the default to balance structure preservation and symbolic color fidelity. These results verify that the proposed framework achieves superior perceptual and semantic quality compared to baseline methods and remains robust under reasonable coefficient variations.

Real-world stylization of Chinese ICH

To further demonstrate the real-world applicability of our approach, we construct a diverse set of content-style pairs rooted in Chinese ICH domains. As shown in Fig 7, each example comprises a 3D-rendered content image inspired by cultural creative products (bottom) and a style reference from authentic folk art artifacts (top). These references span various domains, including clay sculptures, woodblock New Year paintings, paper-cutting, tie-dye, and other region-specific motifs. Unlike previous stylization works—often evaluated on Western-style paintings or simplified cartoon illustrations—our method demonstrates the ability to handle styles that are structurally constrained (e.g., central axial or radial layouts), chromatically symbolic (e.g., auspicious red, tranquil indigo), and semantically embedded in cultural narratives (e.g., guardian tigers or mythic deities). Qualitatively, Colorful Heritage accurately preserves the geometric integrity and identity of content objects, faithfully projects complex visual metaphors and culturally meaningful layout patterns, and maintains color fidelity and fine-grained details in the stylized outputs.

User study

We conducted a user preference study involving 50 participants with diverse educational backgrounds, recruited through an anonymous online form. Each participant was shown a randomized subset of stylization results (total of 200 style-content pairs) and asked to select the preferred output among five anonymized methods. To assess significance, we performed a two-tailed paired t-test comparing Colorful Heritage against each baseline. All results were statistically significant with p < 0.01. To validate inter-rater agreement, we computed Fleiss’ Kappa across all responses, yielding a value of 0.68, indicating substantial agreement.

The goal is to evaluate the degree to which each method produces results that are (1) visually appealing, (2) faithful to the input content, and (3) aligned with the reference cultural style. We randomly sample 50 content-style pairs from our ICHStyleBench benchmark and generate stylizations using five different methods: StyleID25, StyleAligned34, ZipLoRA22, B-LoRA24, and our proposed Colorful Heritage. Rather than presenting all five stylized outputs at once, we adopt a pairwise evaluation protocol: for each pair, participants are shown the content image, style reference, and two anonymized stylized images—one from Colorful Heritage and the other from a baseline method. Each participant completes 30 such comparisons, resulting in a total of 1500 evaluations across all participants. Participants are asked to choose the most stylistically faithful and visually coherent output based on both artistic expression and content retention. For each method, we report the percentage of trials in which Colorful Heritage was preferred over that baseline. As shown in Table 2, Colorful Heritage was preferred in 34.5% of all trials—significantly outperforming B-LoRA (26.7%, p < 0.001), ZipLoRA (25.3%, p < 0.001), StyleAligned (23.1%, p < 0.001), and StyleID (21.4%, p < 0.001), based on one-sided binomial tests. The higher human preference for Colorful Heritage highlights the effectiveness of our framework in producing stylizations that are not only technically consistent but also culturally resonant.

While our user study involves a diverse pool of annotators from various cultural backgrounds, we acknowledge that individual familiarity with Chinese ICH may influence subjective perception of style transfer quality. To mitigate this, we adopt a relative ranking scheme (i.e., pairwise comparisons among stylization outputs) rather than absolute scoring. In future work, we plan to conduct more fine-grained, culturally aware evaluations by explicitly recording participants’ cultural exposure and segmenting the results accordingly.

Impact of structure token

We first analyze the impact of incorporating structural layout priors through the use of the structure token. When this module is removed, the model fails to attend to culturally specific compositions, such as axial symmetry or dynamic coiling patterns. As shown in Table 4, both style alignment and CLIP-S scores drop considerably, confirming that symbolic structure plays a crucial role in accurate visual alignment. Qualitatively, the absence of structural conditioning results in disorganized patterns and a loss of spatial harmony.

Effect of color token

Next, we remove the color token to assess the contribution of chromatic awareness. Without such guidance, the generated results often display muted hues or incorrect palette mappings, deviating from symbolic color conventions rooted in Chinese ICH (e.g., red for joy and celebration, green for life and protection, purple for spiritual or ritual authority). While content is preserved, the perceptual alignment with style images declines, as evidenced by a CLIP-S drop from 0.502 to 0.471. These results highlight the importance of incorporating cultural color cues to achieve stylistically faithful stylization.

Benefit of two-stage training

Finally, we ablate our two-stage semantic disentanglement by jointly training content and style LoRA modules in a single phase. This setting leads to entangled representations, often causing content leakage or stylization collapse. Quantitatively, all metrics degrade, with CLIP-S falling to 0.479. The improvement in the full version demonstrates that staged optimization is more effective at separating identity from style, and that freezing content LoRA allows style features to be learned in a controlled, modular fashion.

Limitations and future work

While our framework focuses on structure- and color-aware stylization of ICH visual forms, it currently does not explicitly model broader sociocultural dimensions, such as regional variation in traditional practices, evolving interpretations of symbolism across generations, or the situated meanings attached to visual motifs within specific communities. These factors significantly influence how authenticity and cultural resonance are perceived, and their absence may limit the contextual appropriateness of stylized outputs. Future work could address this by incorporating context-aware priors, conducting culturally stratified user studies, and embedding models of symbolic polysemy.

Moreover, our current focus is limited to 2D stylization. While this provides a foundational step for visual preservation and accessible dissemination, it does not yet explore how stylized ICH content can be integrated into immersive environments, such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), or 3D spatial installations. Recent work (e.g., refs. 38,39) has shown the potential of such environments to enhance cultural learning and audience engagement. Extending our approach into these interactive modalities represents a promising direction for interdisciplinary expansion, bridging computational esthetics with experiential cultural heritage preservation.

Discussion

We present Colorful Heritage, a computational framework for the digital revitalization of Chinese ICH in the visual domain. Our method integrates structure-aware and color-aware stylization modules within a two-stage disentangled training strategy, enabling faithful digital reconstruction of traditional visual expressions rooted in compositional order, symbolic color systems, and cultural meaning. By explicitly modeling axial symmetry, radial flow, and culturally encoded palettes, our framework ensures that the stylized outputs preserve both semantic integrity and aesthetic authenticity. To support heritage-centered research, we introduce ICHStyleBench, a curated benchmark featuring representative styles from Chinese ICH practices—including woodblock New Year paintings, clay sculpture, embroidery, and paper-cutting—with annotations on structure, theme, and symbolism. Through extensive experiments, we demonstrate that Colorful Heritage significantly outperforms existing stylization methods in preserving the spatial, chromatic, and semantic characteristics of ICH styles. This work highlights the potential of generative AI as a tool for preserving, interpreting, and disseminating intangible heritage. By bridging traditional cultural knowledge and modern computational methods, Colorful Heritage offers a pathway toward responsible and culturally grounded digital heritage technologies. Beyond the core contributions, this work also has broader implications for sustainable cultural development. Specifically, it can support the goals of Sustainable Cities and Communities through digital preservation and revitalization of cultural memory, Quality Education by providing accessible resources for heritage education, and Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure via AI-driven innovation in the cultural and creative sectors. These connections highlight the societal value of our research in preserving heritage while advancing responsible technological applications. While our framework is tailored for Chinese ICH stylization, the core design—separating structure and color priors and enabling token-based adaptation—can be extended to other cultural forms. For instance, Islamic tiles often exhibit symmetric geometric layouts and vivid motifs, while Mayan glyphs embody abstract structural templates. These traditions share common traits (e.g., repetitive motifs, color symbolism) with Chinese visual heritage, and our structure-color disentanglement could facilitate modeling such patterns. Future work may explore the adaptation of our framework to broader ICH domains across cultures.

While most existing stylization frameworks operate as black-box generators, Colorful Heritage enhances interpretability by disentangling structure and color representations via dedicated tokens. This design not only provides transparency into how specific cultural esthetics (e.g., symmetric layout, dominant hues) are reconstructed, but also enables human-in-the-loop manipulation and critique, fostering deeper engagement with heritage elements.

Importantly, we view stylized outputs not as replicas of historical artifacts, but as culturally grounded reinterpretations that revitalize traditional visual forms. By encoding spatial and chromatic priors derived from authentic ICH styles, our framework facilitates creative generation that aligns with traditional norms. Such outputs can serve pedagogical, archival, and design purposes—ranging from museum visualizations to participatory learning environments—thus contributing to the preservation, dissemination, and evolving relevance of ICH in the digital age.

Data Availability

The benchmark data used in this study are part of the ICHStyleBench dataset, which will be publicly released upon manuscript acceptance. It includes the curated image–style pairs and annotations introduced in the paper. The dataset access and detailed documentation will be made available through our GitHub repository: https://github.com/YDU-uva/ICHStyleBench.

Code availability

A minimal reproducibility package is already publicly available at our GitHub repository: https://github.com/YDU-uva/ICHStyleBench. This includes the inference script (inference.py), a notebook demonstration (inference_demo.ipynb), pipeline scripts (pipeline_demo.py), supporting utilities (utils.py), and the required dependency list (requirements.txt), with setup instructions provided in the README. The package has been tested under Python 3.11, PyTorch 2.1, and Diffusers 0.31. The full training code, model weights, and comprehensive benchmark data will be made available upon manuscript acceptance.

References

UNESCO. Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO, 2003).

Shen, J., Liu, N., Sun, H., Li, D. & Zhang, Y. An instrument indication acquisition algorithm based on lightweight deep convolutional neural network and hybrid attention fine-grained features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–16 (2024).

Blake, J. Unesco’s 2003 convention on intangible cultural heritage: the implications of community involvement in ’safeguarding’. Law Herit. 12, 45–57 (2009).

Shen, J. et al. An anchor-free lightweight deep convolutional network for vehicle detection in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 24330–24342 (2022).

Lenzerini, F. Intangible cultural heritage: the living culture of peoples. Eur. J. Int. Law 22, 101–120 (2011).

Shen, J. et al. Finger vein recognition algorithm based on lightweight deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–13 (2021).

Kurin, R. Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage: key factors in implementing the 2003 convention. Mus. Int. 56, 61–68 (2004).

Shen, J. et al. An algorithm based on lightweight semantic features for ancient mural element object detection. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 70 (2025).

Lu, Y. & Sun, Y. Digital approaches to safeguarding intangible cultural heritage: a review. Herit. Sci. 8, 1–15 (2020).

of Culture, M. & of China, T. List of national representative intangible cultural heritage items and inheritors Available at: http://www.ihchina.cn/ (2025).

Li, H. Stylistic differences and regional characteristics of Chinese New Year pictures. Art. Des. 3, 45–52 (2021).

Wang, J. & Zhang, Y. Challenges and prospects of deep learning in the digital protection of intangible cultural heritage visual forms. J. Cult. Herit. Inform. 9, 67–81 (2022).

Gîrbacia, F. An analysis of research trends for using artificial intelligence in cultural heritage. Electronics 13, 3738 (2024).

Wu, X., Yuan, Q., Qu, P. & Su, M. Image-driven batik product knowledge graph construction. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 20 (2025).

Shen, Y., Duan, O., Xin, X., Yan, M. & Li, Z. Styled and characteristic Peking opera facial makeup synthesis with co-training and transfer conditional Stylegan2. Herit. Sci. 12, 358 (2024).

Li, W., Lv, H., Liu, Y., Chen, S. & Shi, W. An investigating on the ritual elements influencing factor of decorative art: based on Guangdong’s ancestral hall architectural murals text mining. Herit. Sci. 11, 234 (2023).

Rombach, R., Blattmann, A., Lorenz, D., Esser, P. & Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proc. CVPR (CVPR, 2022).

Saharia, C. et al. Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. In Proc. NeurIPS (NIPS, 2022).

Ruiz, N. et al. Dreambooth: fine tuning text-to-image diffusion models for subject-driven generation. In Proc. CVPR (CVPR, 2023).

Hu. E. J. et al. Lora: low-rank adaptation of large language models. Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations. ICLR(ICLR, 2022).

Gal, R. et al. An image is worth one word: personalizing text-to-image generation using textual inversion. In Proc. ICLR (ICLR, 2023).

Shah, V. et al. Ziplora: any subject in any style by effectively merging loras. In Proc. ECCV (ECCV, 2024).

Jones, M., Wang, S.-Y., Kumari, N., Bau, D. & Zhu, J.-Y. Customizing text-to-image models with a single image pair. In Proc. SIGGRAPH Asia (SIGGRAPH, 2024).

Frenkel, Y., Vinker, Y., Shamir, A. & Cohen-Or, D. Implicit style-content separation using b-lora. In Proc. ECCV (ECCV, 2024).

Wang Z.et al. Styleadapter: A unified stylized image generation model. International Journal of Computer Vision. 133, 1894–1911(2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Styleadapter: A unified stylized image generation model. Int J Comput Vision. 133, 1894–1911 (2025).

Li, Z., Zhang, S., Liu, Q., Wang, J. & Gao, W. Colormind: Aesthetic colorization of ancient paintings with deep prior and multimodal semantics. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 1362–1376 (2022).

Yang, X., Zhang, Q., Jin, X., Huang, Z. & Hua, X.-S. Dunhuang murals generation with collaborative adversarial learning. In Proc. 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 281–289 (ACM, 2020).

Ao, J., Ye, Z., Li, W. & Ji, S. Impressions of guangzhou city in Qing dynasty export paintings in the context of trade economy: a color analysis of paintings based on k-means clustering algorithm. Herit. Sci. 12, 77 (2024).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proc. NeurIPS (NIPS, 2020).

Sohn, K. et al. Styledrop: Text-to-image synthesis of any style. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 66860–66889 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Inversion-based style transfer with diffusion models. In Proc. CVPR (CVPR, 2023).

Podell, D. et al. SDXL: Improving latent diffusion models for high-resolution image synthesis. In Proc. ICLR (ICLR, 2024).

Hertz, A., Voynov, A., Fruchter, S. & Cohen-Or, D. Style aligned image generation via shared attention. In Proc. CVPR (CVPR, 2024).

Wang, H. et al. Instantstyle: free lunch towards style-preserving in text-to-image generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.02733 (2024).

Radford, A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proc. ICML (ICML, 2021).

Hessel J. et al. Clipscore: A reference-free evaluation metric for image captioning. Proceedings of the 2021 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing. 7514–7528 (2021).

Wang, J., Song, J., Zhang, Y. & Chen, H. Design of 3D display system for intangible cultural heritage based on generative adversarial network. Sci. Program. 2022, 2944750 (2022).

He, J. & Tao, H. Applied research on innovation and development of blue calico of chinese intangible cultural heritage based on artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 15, 12829 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Soft Science Research Project of Henan Province (2025, 252400410476) and the ICH Research Project (2024–2025, 24HNFY-LX053). The authors would also like to thank the local cultural institutions and heritage experts who provided guidance on symbolic color interpretation and semantic annotation design.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. conceptualized the study, led the methodology design, and wrote the main manuscript text. Y.D. implemented the core model and conducted the experiments. G.L. contributed to dataset construction and semantic annotation design. Z.J. and H.Z. prepared Fig. 1–4 and contributed to visualization and result analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, J., Du, Y., Liu, G. et al. Generating Chinese intangible cultural heritage images with structure and color awareness. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02150-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02150-7