Abstract

China is the birthplace of silk weaving, possessing a rich heritage of silk artifacts. Textile patterns exhibit unique artistic value and carry profound historical and cultural significance. Through automated segmentation of the patterns, we can provide technical support for the preservation, inheritance, and innovative application of cultural heritage. Edges are critical for image segmentation. Hyperspectral images enable precise identification of material and dye variations via continuous narrow-band spectral resolution, overcoming the limitations of RGB images in low-contrast edge detection. However, the redundant bands adversely affect results. To address the issue, we propose the edge-oriented multi-objective optimization of the band selection (EOMOBS) algorithm. Furthermore, to overcome texture noise interference, insufficient spectral information utilization, edge breaks, and poor parameter adaptability in existing methods, we propose an improved Canny operator for the selected bands. When applied to textile pattern segmentation, the method achieves 93.74% PA and 73.19% IoU, significantly outperforming sixteen alternative methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China is the first country in the world to have invented silk weaving. From the legendary Lei Zu raising silkworms to various weaving techniques. Among them, traditional silk textile categories such as damask, gauze, silk, satin, brocade, embroidery, and sheer textile are both interrelated and distinctive, forming a systematic craftsmanship system that has been passed down to this day. The patterns on these textiles are not only decorative elements but also important material carriers of the political systems, cultural beliefs, religious concepts, and folk traditions of specific historical periods1. Digitalized traditional patterns not only provide scholars and artists with important materials and data resources for research and creation. Scholars can use digitalized pattern data to conduct studies on artistic styles, historical evolution, and other aspects, thereby promoting artistic research and academic exchanges. Zhang et al. created a database of Qing Dynasty embroidery patterns to analyze their co-occurrence features1. These patterns also serve as a crucial source of design inspiration, offering designers rich cultural connotations and creative materials. With digitalized pattern data, designers can carry out innovative designs, integrate traditional patterns with modern design, and create works with contemporary characteristics. Li et al. established an information database to provide reference and assistance for foreign designers in need2. Additionally, digitalized traditional patterns support and drive the development of the cultural industry: by utilizing digitalized pattern data, a wide variety of cultural products can be developed, boosting the prosperity and growth of the cultural industry3. In summary, the digital construction of traditional patterns holds significant importance and necessity in cultural inheritance, artistic research, design innovation, and cultural industry development. Through the digital extraction of textile patterns, a database of traditional textile patterns can be constructed to achieve cultural inheritance, protection, and reconstruction, and to deeply integrate with modern culture to give it new vitality.

Hyperspectral imaging is an analytical technique that captures both spatial and spectral reflectance data of objects optically. To date, hyperspectral imaging technology is one of the most secure detection technologies, because it is not limited to the detection object and the detection environment. Hyperspectral imaging does not touch or damage the object being examined. Therefore, hyperspectral imaging analysis technology has been widely applied to the research in the field of cultural heritage protection, including the identification of painting pigments4, the discrimination of the age of cultural relics5, the digital restoration of ancient paintings6, the excavation of implicit information in paintings7, and other aspects. Pattern segmentation constitutes a critical technical component in the digital preservation of cultural heritage8. However, for textiles with patterns and backgrounds of similar colors, RGB images relying solely on three broad bands often fail to effectively distinguish regions with similar colors but different materials or dyes, resulting in segmentation difficulties. In contrast, hyperspectral images (HSI) leverage their fine spectral resolution from continuous narrow bands to accurately identify characteristic spectral differences between various materials and dyes, thereby overcoming the technical limitations of RGB images in segmenting patterns with similar spectral features and enabling precise extraction of low-contrast textile patterns.

Although abundant spectral bands of HSI provide rich information for pattern segmentation of textiles, the existence of redundant bands affects the final decision. Moreover, high-dimensional hyperspectral data causes the Hughes phenomenon or the curse of dimensionality, making the analysis more difficult9. Specifically, the use of full-band modeling analysis not only increases the computing cost and leads to poor real-time performance but also causes problems such as high complexity, poor stability, and overfitting. Feature extraction and feature selection are considered two efficient ways to solve the above problems10. Feature extraction maps the raw high-dimensional data into low-dimensional data after a series of feature transformations. However, this method can sometimes disrupt the physical integrity of the original data, potentially leading to information loss critical for segmentation tasks11. Feature selection, also known as band selection (BS) in HSI, aims to find a band subset that contains several of the most representative bands from the full bands12. BS retains the attributes of the original data and prevents the damage of physical information, which facilitates interpretation and practical application13.

However, out of hundreds of bands, only a few bands have significant pattern/background variability due to the phenomena of “same material, different spectra” and “same spectra, different material” in some bands. Therefore, selecting effective spectral bands is crucial for pattern segmentation tasks. Existing BS methods can be divided into three groups: supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised14. Since it is difficult to get the labels of hyperspectral images, unsupervised band selection is more practical. Up to now, a lot of unsupervised band selection methods have been proposed. Many unsupervised BS methods reformulate as a single-objective optimization problem, focusing either on preserving essential information or minimizing redundancy. It is difficult for single-evaluation-criterion methods to comprehensively evaluate bands from multiple perspectives. In contrast, the multi-objective optimization (MO) BS methods can evaluate the bands separately from different perspectives to obtain an optimal solution that balances all the objectives simultaneously.

The problem of hyperspectral band selection is indeed challenging due to the high dimensionality and the complex, often nonlinear, interactions between the spectral bands. As the number of available bands grows, the number of possible combinations increases exponentially, making the search space vast and computationally expensive. Additionally, with the increase in the number of MO problems’ objectives, the solution of the compromised state becomes more and more complex. In the process of solving MO problems, researchers found that swarm optimization algorithms can search in parallel and deal with a set of possible solutions simultaneously. When the components of a set of Pareto solutions cannot be improved at the same time, it can approach the Pareto front (PF) and solve multi-objective complicated problems. The non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II)15 proposed is one of the most efficient algorithms in solving multi-objective optimization problems. NSGA-II solved the main issues of NSGA and introduced an improved version with the O(MN2) computational complexity.

Current research on image segmentation primarily includes threshold16, clustering17, watershed18, morphological19, edge detection20, superpixel21, region22,23, graph-based24, and neural network25 methods. In computer vision, image boundaries can be defined as abrupt changes in brightness, color, or texture between adjacent regions26. Edges serve as the most crucial basis for image segmentation, and edge detection algorithms, as classical segmentation methods, offer the advantages of high computational efficiency, simple principles, and easy implementation. These methods obtain object contours through detected edges to accomplish segmentation. Therefore, effective edge detection algorithms are particularly valuable for image segmentation. Generally, most edge detection methods for color or HSI can be categorized into monochromatic approaches and vector-valued techniques. Monochromatic methods apply grayscale edge detectors to individual bands and then combine all edge maps through summation, thresholding, or logical operations27. Alternatively, HSI may be reduced to one or more dimensions to apply traditional grayscale or color edge detectors28. These approaches may lead to information loss and frequently generate false edges through simple combinations. Unlike monochromatic methods, vector-valued techniques treat each pixel as a spectral vector and employ vector operations for edge detection. Generally, vector-valued methods outperform monochromatic approaches as they account for spectral correlations between bands.

The traditional Canny edge detection method, renowned for its low BER, high localization accuracy, and effective suppression of false edge points29, is widely used in image processing. However, as it is only applicable to single-channel grayscale images, it fails to utilize the multi-channel spectral information in hyperspectral images effectively. Additionally, the traditional Canny algorithm requires manual threshold setting, hindering adaptive edge detection. To address this, we propose an improved Canny algorithm for hyperspectral images. After band selection, the improved Canny algorithm is used for edge detection in textile hyperspectral images for pattern segmentation. The main contributions of this article can be concluded as follows:

-

(1)

We propose a band selection algorithm for HSIs, which is called edge-oriented MO of band selection (EOMOBS), which specifically focuses on edge detection. This model simultaneously involves two factors, including information and redundancy, which can better describe the characteristics of the bands in HSI. Edge-oriented evaluation mechanism is constructed to select the final solution from the Pareto front, so the selected band subset is more conducive to edge detection.

-

(2)

We propose an improved Canny algorithm for edge detection in textile HSIs. The method fuses information from multiple channels from EOMOBS through vector calculation and automatically selects optimal high and low thresholds according to image characteristics, offering better adaptability than the traditional Canny operator. When applied to textile pattern segmentation, it achieves excellent segmentation results.

Methods

This section describes the process of multi-objective optimization to select a hyperspectral band subset for pattern segmentation, as shown in Fig. 1. Firstly, HSIs of textiles are collected. Secondly, a multi-objective model for band selection is constructed, which involves two objectives in terms of information content and redundancy. Thirdly, the NSGA II algorithm is used to optimize the MO problem, and a group of Pareto solutions is obtained. Then, an evaluation mechanism based on edge-oriented is developed to identify the optimal solution from the Pareto solutions for the edge detection task. The Edge-Oriented Evaluation Mechanism is crucial as it leverages the Fisher score in an unsupervised way, defining scatter matrices to model edge compactness and edge-background separability. This enables quantitative assessment of band subsets’ suitability for edge detection, ensuring the selected subset optimizes subsequent edge extraction. Finally, the improved Canny algorithm was proposed for HSI edge detection, whose edge detection process proceeds as follows: first, it applies bilateral filtering to reduce noise in hyperspectral images while preserving edge details, and is then followed by histogram equalization on the smoothed images to enhance contrast. Next, it performs spectral-vector gradient calculation, fusing the multi-channel spectral information of hyperspectral images via vector computation to generate gradient maps. Then, it performs Interpolation-based non-maximum suppression (NMS) on the gradient magnitude to thin edges into a single-pixel width. Subsequently, it adopts Otsu-adaptive thresholding, automatically calculating optimal high and low thresholds based on the gray-level distribution of the NMS map. The NMS map then undergoes dual-threshold detection and edge linking to obtain the edge map. To fill edge depressions and clarify pattern contours, morphological dilation is applied to the edge map. Based on this, noise and incomplete patterns are automatically filtered out according to the area, length, and width of each connected component, yielding a more precise outline of the complete pattern target. Finally, an α channel (transparency channel) is added to the original RGB channels, rendering the background transparent to effectively segment the foreground pattern region.

The two core novel aspects of our work can be concluded as follows. First, we propose a hyperspectral image band selection algorithm named Edge-oriented Multi-objective Optimization of Band Selection (EOMOBS). Unlike existing band selection methods that often focus solely on information or redundancy, EOMOBS simultaneously integrates both factors to better characterize HSI bands, and innovatively constructs an edge-oriented evaluation mechanism to screen the optimal solution from the Pareto front, ensuring the selected band subset is more favorable for subsequent edge detection. Second, we develop an improved Canny algorithm for textile HSI edge detection: this method fuses multi-channel information from EOMOBS via vector calculation and automatically determines optimal high/low thresholds based on image intrinsic characteristics, addressing the poor adaptability of traditional Canny operators, which rely on manual threshold tuning, and achieving superior performance in textile pattern segmentation. In the following text, the main modules of the proposed method will be sequentially introduced.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

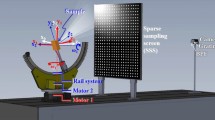

The hyperspectral images were acquired using a hyperspectral imaging system, which consists of a Specim IQ hyperspectral camera (Specim Ltd., Oulu, Finland), two 300 W halogen lamp illumination units, and a computer. The hyperspectral camera captures images with a spectral range of 400–1000 nm, a spectral sampling interval of 2.89 nm (totaling 204 bands), and an image size of 512 × 512 pixels. The hyperspectral camera can simultaneously capture both HSI and RGB images. The distance between the lens and the textile surface was fixed at 600 mm. The raw data obtained from the hyperspectral imaging system are radiance images, which cannot be directly used for spectral analysis. Additionally, variations in environmental parameters and interference from dark current noise introduce noise into the data. Therefore, preprocessing such as radiometric correction and denoising is required. The radiometric correction formula is as follows:

where R represents the radiometrically corrected data, Rrow is the original hyperspectral data of the textile, Rdark is the dark current data obtained by turning off the lights and blocking the light, Rwhite is the data from the standard reflectance panel, and ρ is the reflectance of the standard panel, which has a reflectance of 99%.

MO band selection

MO band selection model

BS is intended to select a subset of bands that are informative and with low redundancy. Therefore, we first establish an MO model for edge detection, which contains two subobjectives to select a band subset with rich information and low inner redundancy. It is defined as follows:

Here, K is the number of bands in the selected subset x. f1(x) and f2(x) are used to evaluate the information content and redundancy, respectively. Specifically, H(xi) represents the information entropy of the ith band of the selected subset. JSS(xi, xj) indicates the JSS similarity of the ith band and jth band, which not only measures the spectral similarity but also accounts for the dispersion of the spatial distribution of the selected bands. The two subobjectives are detailed as follows.

Information Entropy

For the studies concerning BS, Information Entropy is commonly used to describe the information richness. Let \({\left\{{b}_{l}\right\}}_{l = 1}^{L}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times L}\) represent an HSI with L bands, where each band bl has N pixels. Thus, the entropy of a band can be calculated by

Here, each band bl is regarded as a set of random variables x ∈ Xl with the sample space defined on the entire image. p(x) stands for the probability density function and can be obtained by

where h(x) represents the number of pixels taking the value at x. In general, the higher the entropy of a band, the richer the information it may contain. In addition, since the entropy is usually insensitive to noise, it is more robust in processing the noise-polluted data.

JSS similarity

In addition, since the range of each band of the hyperspectral image is narrowed and the spectrum is the same kind of wave in a certain range, there is a remarkable feature that high similarity exists among adjacent bands (see Fig. 2). Reducing the intra-correlation of the selected bands is another essential goal for BS. The commonly used measures of similarity between bands include spectral angle, Euclidean distance, and Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, which generally expand the bands into 1-D vectors and mine the linear correlations between them from the spectral dimension, with limited attention to the complex nonlinear properties.

In MOBS, the correlation between two bands was measured both in the spectral and spatial dimensions, which can be simply conceptualized as

Here, Sspectral and Sspatial represent the spectral similarity and spatial similarity, respectively, and are defined as

Specifically, the spectral similarity of the bands, bi and bj, is derived from their spectral distance. The more similar they are in the spectrum, the larger the \({S}^{spectral}({b}_{i},{b}_{j})\) is, and takes values between 0 and 1. The computation of spatial similarity is predicated on the assumption that the bands of HSIs are arranged in order of imaging wavelength, where bands in close spatial proximity should exhibit similar feature representation capabilities. Therefore, the distribution of BS results should be as sparse as possible. In (7), the band indices, Ibi and Ibj, are used to reflect the location information of bands. The closer the locations of bi and bj spatially, the larger the Sspatial(bi, bj) is. Besides, σ and ω are the kernel parameters that are set as \(\sigma =\frac{1}{L}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{l = 1}^{L}\parallel {b}_{i}-{b}_{l}\parallel\) and \(\psi =\frac{1}{L}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{l = 1}^{L}\left\vert {I}_{{b}_{i}}-{I}_{{b}_{l}}\right\vert\), respectively. This scheme of JSS relations has been previously used for hyperspectral spectral-spatial hypergraph construction30, demonstrating its effectiveness in evaluating band similarity. By minimizing the f2(x) in (2), a subset of bands with lower spectral similarity and the sparser spatial distribution can be obtained.

Edge-oriented evaluation mechanism

According to different application requirements, the optimal solution selection methods of PF are different. At present, the optimal solution is usually selected by trial-and-error31, decision-maker (DM)32, clustering33, and the knee-point-based selection method34. Most of these methods are based on classification performance, so the selected band subset is suitable for classification tasks, but not for edge detection tasks.

The Fisher score is one of the most widely used supervised FS methods based on the Fisher theory35. In general, Fisher score uses the ratio of between-class scatter (which evaluates the separability of different classes) and within-class scatter (which models the compactness within each class) to measure the discrimination of the given feature according to the available labeled samples. In this article, an unsupervised trace ratio criterion is defined in the context of the Fisher score with edges. For HSI, the pixels within edges are considered to belong to the same class; the pixels within the background are considered to belong to another class.

Let p1 denote an edge pixel and p0 denote a background pixel, where \({p}_{k}=\left\{{x}_{1}^{(k)},{x}_{2}^{(k)},\ldots ,{x}_{{n}_{1}}^{(k)}\right\},\quad (k=0,1)\). Here, \({x}_{i}^{(k)}\) denotes the i th pixel in pk, and nk is the number of pixels in pk. To model the compactness within the edge and evaluate the separability between edge and background, the within-edge scatter matrix SWEP and the between-edge and background scatter matrix SBEP can be written as follows:

where m is the mean vector of edge pixels and background pixels; mk is the mean vector of the kth pixel. The typical Fisher score is designed in the form of an unsupervised trace ratio criterion with edge. An edge-oriented evaluation mechanism is designed for optimal result selection in this article. The EOMOBS algorithm evaluation mechanism can be defined as follows:

where trace() denotes the trace of a matrix.

NSGA-II MOBS algorithm and solution

To effectively detect the target, this article adopts the virtual dimensionality (VD) method36 to determine the number of bands without supervision. VD is a method for determining the number of bands based on the different features of the spectrum in hyperspectral data under the Neyman-Pearson detection theory. It can be seen that for different data, the number of selected bands nBS by the VD method will change with the target signatures. Hyperspectral data records a scene from the observed area with a number of spectral signatures. For the development of hyperspectral data, the VD method is effective and suitable. Therefore, this article uses the VD method to determine the number of selected bands.

The detailed process of the EOMOBS algorithm is as follows.

Step 1: Initialization.

Use the VD method to determine the number of selected bands. Set the initial parameters, such as the number of iterations, the number of populations, and algorithm parameters.

A permutation encoding method based on integer numbers is adopted, and each chromosome represents a feasible solution to the problem to be optimized. Each chromosome is encoded as a permutation of integers, where each integer corresponds to a unique band index in the HSI. The total number of bands is N. A chromosome is represented as [b1, b2, . . . , bK], where K is the number of selected bands and bi denotes the index of the i-th selected band, where 1 ≤ bi ≤ N. This ensures that each chromosome represents a feasible subset of bands without duplication. Initialize the population Pt. Calculate the values of the proposed objective functions of all individuals in the population Pt. NSGA-II uses nondominated sorting for fitness assignments. All individuals not dominated by any other individuals are assigned the front number 1. All individuals dominated by individuals in front number 1 are assigned front number 2, and so on, to determine the Pareto grade of the individual.

Step 2: Evolution Produces the Next Generation of Population.

Selection is made using a tournament between two individuals. The individual with the lowest front number is selected if the two individuals are from different fronts. In order to ensure population diversity and make the population evolve towards a better direction, the crowding degree is introduced into the algorithm, which represents the density of other individuals around a certain individual in the same non-dominated level. The individual with the highest crowding distance13 is selected if they are from the same front, i.e., a higher fitness is assigned to individuals located on a sparsely populated part of the front. In every iteration, the N existing individuals (parents) generate N new individuals (offspring). Both parents and offspring compete with each other for inclusion in the next iteration.

Step 3: Genetic Operation of Crossover and Mutation.

According to the adaptive crossover rate and mutation rate, the genetic operation of crossover and mutation is carried out for the new population.

Crossover operation:

The selected bands are not repeated, so no duplicate numbers are allowed in a chromosome. Partially mapped crossover (PMX) is one of the most popular and effective crossovers for order-based GAs to deal with combinatorial optimization problems. In view of the operation, PMX can be regarded as a modification of two-point crossover, but additionally uses a mapping relationship to legalize offspring that have duplicate numbers.

Mutation operation:

Each chromosome is subject to a mutation probability pm to determine whether elements on the chromosome will undergo mutation. If selected for mutation, these elements will be replaced with other valid values within the predefined range. If the mutated value duplicates an existing element on the chromosome, the conflicting element will be replaced through a matching mechanism. This mutation operator enables the chromosome to acquire values that were not originally present, thereby ensuring the mutual exclusivity of the selected bands.

To sum up, the mutation operation further increases the particle diversity, which helps to avoid falling into local optimality. Crossover operation realizes the information sharing among the high-quality individuals.

Step 4: Update the Alternative Solutions set.

After the new generation of population Pt is obtained, the fitness of all individuals is recalculated based on the objective functions. Then, the nondominated solutions in Pt + 1 are added to the alternative solutions set.

Step 5: Output a Band Subset.

The loop ends when the t reaches the maximum number of iterations MaxT. Based on the information contained in the alternative solutions set, H-band subsets can be obtained, which together form the PF of the proposed MOBS model. Using the proposed edge-oriented evaluation mechanism, a subset of the N band subsets is selected as the final output. All H band subsets in the PF are evaluated using this mechanism, and the subset with the maximum evaluation score f (Equation (10)) is selected as the final output. This subset is optimal for edge detection, as it maximizes the distinguishability between edge and background pixels.

Pattern segmentation based on improved Canny algorithm

The Canny edge detector method, proposed by John Canny in 198637, has been widely adopted due to its superior noise suppression and high detection accuracy. The traditional Canny edge detection process consists of five sequential steps: (1) Image smoothing using a Gaussian filter. (2) Computation of gradient magnitude and direction through differential operators. (3) Non-maximum suppression of gradient magnitudes to retain local maxima and refine edges. (4) Thresholding with dual thresholds: pixels exceeding the high threshold are classified as strong edges, those below the low threshold as non-edges, and intermediate values as weak edges. (5) Edge linking to connect weak edges adjacent to strong edges, producing the final edge detection results.

While the Canny algorithm has been extensively applied in image edge detection, it exhibits three significant limitations. First, its reliance on Gaussian filtering for noise reduction inevitably smoothens edges, potentially causing the loss of weak edges. In high-noise images, this approach may erroneously identify noise as edges. Second, the requirement for manually specified dual thresholds compromises the algorithm’s adaptability. Third, the Canny algorithm is fundamentally designed for single-channel grayscale images, making it incapable of effectively utilizing the rich spectral information contained in hyperspectral image data.

To deal with the limitations of the traditional Canny algorithm, we propose an improved approach that involves the bilateral filter algorithm, adopts multi-channel vector fusion, and automatically selects optimal thresholds according to image characteristics. The improved Canny algorithm used for pattern segmentation is implemented as follows:

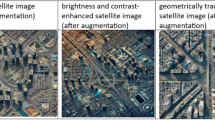

Histogram equalization

Since some textile hyperspectral images exhibit uneven grayscale distribution, histogram equalization is employed to adjust the grayscale distribution38, ensuring pixel values are uniformly distributed across the entire dynamic range (0–255). This prevents the intensity of the entire image from concentrating in a very small region, resulting in a more uniform histogram distribution and thereby enhancing details.

HSI smoothing based on the bilateral filter algorithm

The texture noise in textile images can interfere with edge detection. To reduce the impact of texture on edge detection, we employ a bilateral filter algorithm to replace the Gaussian filter. Unlike linear convolution filters, the bilateral filter utilizes both a range kernel and a spatial kernel, typically both Gaussian. The range kernel input represents intensity differences between the target pixel and its neighbors. Significant differences result in minimal weight assignment to adjacent pixels, effectively excluding them from aggregation. This mechanism prevents the mixing of pixels with large intensity variations, thereby preserving sharp edges. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where N(p) represents a k × k rectangular window centered at point p. I(p) denotes the pixel value at point p; I(q) represents the pixel value at neighboring point q; Ibf(p) indicates the filtered output pixel value at point p. Wp serves as a normalization factor. σs and σr represent distance and intensity difference scale parameters, respectively.

For comparison purposes, both filters were applied to process textile HSI at 663.81nm wavelength, as shown in (Fig. 3). The Gaussian filter effectively smoothed texture noise but simultaneously caused edge blurring. In contrast, the bilateral filter algorithm successfully removed image texture noise while better preserving the original pattern edges. Therefore, employed the bilateral filter to smooth textures for each channel of the textile HSI.

Calculation of gradient magnitude and direction based on multi-channel vector fusion.

Unlike grayscale images, where each pixel is a scalar value in [0,255], hyperspectral pixels comprise spectral reflectance values across dozens to hundreds of continuous narrow bands. Thus, each pixel can be treated as a vector of spectral reflectance. Three points, P1, P2, and P3, were selected. P1 and P2 were sampled from the cloud pattern region (foreground), while P3 was selected from the background. Their spectral curves are shown in Fig. 4.

Euclidean distances between spectral vectors in n-dimensional hyperspectral space were calculated as D12 = 0.1, D13 = 5.36, and D23 = 5.29, demonstrating that closer spectral curves yield smaller distances. Spectral similarity metrics are crucial for hyperspectral analysis and material classification. Three spectral measures were implemented: L1 distance, Euclidean distance, and Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM).

L1 distance between points p and q:

where pi and qi represent the reflectance values of pixels p and q in the i spectral band, respectively. Similarly, the Euclidean distance can be calculated as:

SAM is defined as:

Based on the above analysis, we can compute gradients between adjacent pixels using different distance metrics. The Canny algorithm employs gradient operators like the Sobel operator to convolve with grayscale images for gradient computation. The Sobel operator, known for its simple formulation and noise robustness, is widely used for gradient calculation. In grayscale images, the horizontal and vertical convolution kernels of the Sobel operator are defined as shown in Fig. 5.

Building upon the proposed gradient calculation method for adjacent pixels, we have modified the gradient computation in the Canny algorithm to directly obtain gradient images for hyperspectral data. The improved gradient calculation method is demonstrated below using a pixel matrix example. For an 8-neighborhood pixel matrix \(\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{a}_{0}&{a}_{1}&{a}_{2}\\ {a}_{3}&(i,j)&{a}_{6}\\ {a}_{7}&{a}_{8}&{a}_{9}\end{array}\right)\) centered at (i, j), \({a}_{i}=({a}_{{i}_{1}},{a}_{{i}_{2}},\cdots \,,{a}_{{i}_{n}})\),i = 0, 1,..., 7, n represents the number of spectral bands.

Then we employ the Sobel operator to compute the gradient magnitude and direction at pixel (i,j). (16) and (17) represent gradients along the x-axis and y-axis, respectively, while (18) and (19) denote the edge gradient magnitude and direction:

NMS based on interpolation

The traditional Canny operator’s NMS approximates gradient directions to 0∘, 90∘, 45∘, or 135∘. However, actual edge gradients may not align with these fixed directions. The NMS based on the interpolation method39 utilizes gradient magnitude interpolation to calculate adjacent pixel values, as illustrated in Fig. 6. For each pixel, Equation (18) provides the gradient magnitude G, and Equation (19) provides the gradient direction θ. Equation (20) then uses these outputs to obtain the gradient G of the center pixel and its 8 neighboring pixels. For a given pixel point (x0, y0) with gradient direction θ the extension of this direction intersects the 3 × 3 neighborhood window at points P1 and P2, where d represents the distance from P1 to (x0 − 1, y0 + 1). G(x0 − 1, y0 + 1), G(x0, y0 + 1) and \({G}_{{p}_{1}}\) denote the gradient magnitudes at points (x0 − 1, y0 + 1), (x0, y0 + 1), and P1 respectively. The gradient magnitude \({G}_{{p}_{1}}\) at P1 can be computed using linear interpolation as:

Similarly, the gradient magnitude at point P2 in the opposite direction can be calculated. By comparing the gradient magnitudes at the center point G(x0, y0) with those at \({G}_{{p}_{1}}\) and \({G}_{{p}_{2}}\) along the gradient direction, NMS is performed. This process ensures that only the pixel points with maximum gradient magnitude along the gradient direction are preserved, thereby refining the edges.

Threshold adaptive setting based on the Otsu threshold method

In traditional Canny algorithms, the selection of high and low thresholds requires manual adjustment through experimental results, significantly reducing the algorithm’s adaptability and efficiency. This paper employs the Otsu algorithm to adaptively determine the optimal threshold for hyperspectral images. Also known as the maximum inter-class variance method, the Otsu algorithm divides an image into foreground and background based on the distribution of grayscale values. It calculates the inter-class variance between background and foreground under different thresholds. The threshold corresponding to the maximum inter-class variance is selected as the Otsu threshold. For an image with M × N pixels, let N0 represent pixels with grayscale values below threshold T (mean grayscale u0), and N1 represent pixels with grayscale values above T (mean grayscale u1). The proportions of these two-pixel groups in the entire image are:

The total mean grayscale of the image is denoted as μ, and the inter-class variance is expressed as g:

The threshold T corresponding to the maximum inter-class variance g is selected as the high threshold, which best separates foreground (edge pixels) and background pixels. The high threshold obtained through the above steps is used to set the low threshold at 0.4 times its value40. Pixels with gradients exceeding the high threshold after non-maximum suppression are marked as edge pixels. Those with gradients between the high and low thresholds are classified as weak edge pixels, while pixels with gradients below the low threshold are considered non-edge points.

Pixels with gradients exceeding the high threshold after non-maximum suppression are marked as edge pixels. Those with gradients between the high and low thresholds are classified as weak edge pixels, while pixels with gradients below the low threshold are considered non-edge points.

Pattern segmentation

To address edge depressions in the edge-detected image, resolve discontinuities in fractured regions, and enhance pattern contour clarity, morphological dilation is applied to the edge image. Dilation, a fundamental morphological operation, is widely used for noise suppression, region segmentation, and connectivity restoration in image processing. Dilation is an operation to obtain the local maximum, and we do morphological inflation according to \(A\oplus B=\{z| {(B)}_{z}\cap A\ne {{\emptyset}}\}\), which is presented in Fig. 7a. Where A is an image, B is a 3 × 3 rectangular solid core, and its anchor point is in the center, indicating that A is inflated by B. The grey pixels are the dilated pixels that are considered as part of the output image (in fact, they are black). In Fig. 7b, it can be observed that before dilation, certain edges are fragmented and fail to form a connected region. For example, the auspicious cloud pattern edge emphasized by the red box shows this fragmentation. After dilation, these broken edges become connected, thus creating a single connected region for the auspicious cloud pattern edge. Such connectivity is highly significant because it enables the successful extraction of the auspicious cloud pattern in subsequent segmentation procedures, thereby ensuring the pattern’s integrity for accurate identification.

To automatically filter out noise and incomplete patterns, we calculate the area, length, width, and position of each connected component. We first draw a distribution map of the areas of all connected regions in the image. By analyzing this distribution, we initially set the area threshold to 200 pixels to remove connected regions with extremely small areas from the image to filter out noise. This threshold is determined to effectively remove noise while ensuring that complete patterns remain unfiltered. For individual images where this threshold may not be optimal, we adjust it by observing the noise filtering results and referring to the specific area characteristics of patterns in each image. Incomplete patterns with local missing parts have low reusability, so they are filtered out. Since most patterns located at the edges of the image are incomplete, we additionally eliminate patterns at the image edges to filter out incomplete ones. As shown in Fig. 8, it is evident that noise and incomplete patterns have been effectively removed, leaving clear and complete pattern edges.

Finally, an α channel (transparency channel) is added to the original RGB channels. We render the background transparent and convert the foreground pattern regions within the connected components into non-transparent areas, thereby effectively segmenting the foreground pattern regions. The segmentation framework is illustrated in Fig. 9.

Evaluation Metrics

For this pattern segmentation task, we employ PA, IoU scores, Precision, Recall, F1 score41 to quantitatively assess segmentation quality. Pixel accuracy (PA) is the ratio of properly classified pixels divided by the total number of pixels. For K + 1 classes (K foreground classes and the background), pixel accuracy is defined as:

where pij is the number of pixels of class i predicted as belonging to class j.

Intersection over Union (IoU) - Also known as the Jaccard Index, is a measure to describe the extent of overlap of the predicted segmentation mask with the ground truth. It is defined as the intersection area between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth, divided by the area of the union between the predicted segmentation mask and the ground truth:

where TP stands for the true positive fraction, FP refers to the false-positive fraction and FN refers to the false-negative fraction. A and B denote the ground truth and the predicted segmentation, respectively; they go between 0 and 1.

Precision/ Recall/ F1 score can be defined for each class, as well as at the aggregate level, as follows:

Usually, one is interested in a combined version of precision and recall rates; the F1 score is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

Results

Datasets

So far, there is no benchmark for textile pattern edge detection and segmentation of HSI in close-range settings. Furthermore, visual comparison without statistical measures is not adequate to make an objective judgment of which result is better. Therefore, we created a hyperspectral image pattern segmentation dataset (HSI-Pattern). This hyperspectral imaging system acquires both hyperspectral and RGB images simultaneously. This is the first benchmark dataset for textile pattern edge detection and segmentation of HSI. While the dataset currently includes 30 images, it is deliberately designed to cover diverse traditional textile elements. First, it covers a range of common materials, including brocade, satin, damask, gauze, silk, fine silk, light silk, velvet, and cotton, among others. These materials span both protein-based and plant-based fibers, and they also have distinct textures. Second, it covers several major categories of cultural patterns, including plant patterns, animal patterns, character patterns, and artifact patterns. The plant patterns include peony, orchid, chrysanthemum and pomegranate, and more. The animal patterns include crane, butterfly and phoenix, and more. The character patterns are the Chinese characters for “fortune” and “longevity”. The artifact patterns include the “Eight Treasures” motif, which is a representative decorative pattern rooted in Buddhist culture. These patterns represent Chinese typical design styles in textile heritage, with varying complexity and color contrasts. Third, it involves four traditional crafting techniques: embroidery, brocade weaving, Zhang velvet, and kesi. Embroidery has stitched details. Brocade weaving has raised textures. Zhang velvet is a pile-weaving technique for velvet. Kesi is a weft-faced tapestry technique. Each of these techniques adds unique spectral and structural features to HSI data. To ensure annotation reliability, the ground truth patterns segmentation was labeled by three users, with the best one selected for the final experiments.

Bands selection result

In this section, a comparative experiment between the proposed multi-objective optimization NSGA-II and the Single-objective optimization GA is given. The fitness functions of the GA are set as f1 and f2, respectively. It is worth noting that we set the same basic parameters on the considered data sets. Table 1 shows the parameter settings of GA and NSGA-II. For the NSGA-II and the GA, three BS trials were carried out owing to the stochastic nature of the GA. One can observe from Fig. 10 that the bands selected by the GA(f1) on the three HSI-Pattern data samples are more concentrated on the three trials. On the contrary, the bands selected by the NSGA-II and GA(f2) are more evenly distributed across the range of all bands. From Table 2, one can see from the result of this experiment that the proposed NSGA-II approach selects band subsets more informative than the GA(f2) approach. In addition, the proposed NSGA-II achieves higher pixel accuracy (PA) than the GA on the three HSI-Pattern data samples. The comparison shows the improved effectiveness of the proposed NSGA-II approach.

Pattern segmentation result

First, to comprehensively validate the effectiveness and superiority of our algorithmic improvements for the Canny operator, we conducted two rounds of complementary ablation experiments targeting different verification objectives. We first performed a preliminary ablation study based on the original traditional Canny operator: in each experimental group of this preliminary study, we only replaced one of our proposed improved steps with the original method of traditional Canny edge detection, while keeping all other steps consistent with the original operator, aiming to verify whether each individual improved step could independently bring performance gains compared to the traditional approach.

The experimental results of the preliminary ablation study are presented in Fig. 11 and Table 3. It can be visually observed that, compared with the edge detection result of the original Canny operator, each experimental group with only one improved step added has obvious optimization. All experimental groups with a single improved step achieve higher values in evaluation metrics compared with the original Canny operator.

On the basis of this preliminary verification, we then carried out ablation experiments in the integrated system. We took our fully improved algorithm as the baseline, and in each comparative method, only one of the improved steps was replaced with the original method of traditional Canny edge detection, while the other steps remained using our improved methods. This design, which builds on the preliminary validation of individual step effectiveness, allowed us to further clarify the specific performance impact of each individual improvement direction in the integrated algorithm system.

Performance of different filter measures

Edge detection on hyperspectral images filtered by Gaussian and bilateral filters yielded results shown in Fig. 12a and b. In Fig. 12a, edge loss occurred; for instance, the lines of the upright crane’s legs were severely missing. In contrast, Fig. 12b showed more complete edges. Table 4 demonstrates the quantitative results on the HSI-Pattern dataset. The quantitative results further show that the bilateral filters of the proposed method improve the edge detection performance (IoU by 27.85%, PA by 13.09%, Precision by 2.71%, Recall by 41.53%, and F1-score by 22.35%).

Performance of single-channel HSI, multi-channel HSI, and RGB edge detection measures

Typically, the Canny operator detects edges in RGB images after converting them to single-channel grayscale. We applied two methods: conventional grayscale conversion and a vector-based color image method. The results are shown in Fig. 12d and e, respectively. Additionally, edge detection results for a single-channel grayscale image at 663.81 nm wavelength and the vector method using all channels in HIS are presented in Fig. 12c and f, while Fig. 12a shows the result of our proposed HSI Band Selection method. Evidently, the results of the single-channel method and the two RGB methods exhibit significant edge loss at the lower left corner. HSI, with its high spectral resolution and richer information, can detect more complete edges compared to RGB. It is worth noting that our Band Selection method achieves a higher PA and IoU (93.74% and 73.19%) with only selected bands than the vector method using all 204 bands (92.00% and 73.09%). It is expected due to the curse of dimensionality problem.

Performance of different similarity measures

Results using L1 distance, Euclidean distance, and SAM are shown in Fig. 12a, g, and h. The L1 distance method produced edges that better conformed to the actual patterns. The Euclidean distance method generated more noise in the lower-left corner with poorer edge continuity. While the SAM method maintained better edge continuity, it introduced significant noise and false edges in the lower-left region, causing pattern connections and segmentation failures. It also outperformed the Euclidean distance and SAM methods in the quantitative results.

Performance of different NMS measures

Figure 12a shows that our interpolation-based NMS significantly improves edge continuity over traditional NMS (Fig. 12i). By preserving continuous gradient directions, it effectively resolves the edge breakage issue of the traditional Canny operator, leading to improved precision.

Performance of manual and Otsu adaptive thresholding

The selection of thresholds significantly affects the results of Canny edge detection. When manually setting thresholds, for example, setting them to 40 and 100 as in Fig. 12j, it frequently leads to substantial edge loss or redundancy. In contrast, our automatic thresholding method, as demonstrated in Fig. 12a, obviates the need for manual parameter adjustment. It not only enhances the efficiency of the algorithm but also achieves superior edge detection results without any noticeable reduction in performance.

In summary, the design of our final improved algorithm is based on two rounds of ablation experiments with complementary logic. The combination of the two rounds of experiments makes the design of the improved algorithm more systematic and rigorous. Overall, the method balances performance and speed: it boosts accuracy without significantly increasing runtime.

Furthermore, we compare the proposed image segmentation method with various representative HSI approaches in the HSI-Pattern dataset, including Unet42, PSPNet43, DeepLabv3+44, and a HSI boundary detection method45. In addition, we compare our method with three RGB edge detection methods, including TEED46, PiDiNet47, and DexiNed48. Table 5 demonstrates the quantitative results. From the results, the proposed method performs best in all five metrics. Specifically, the proposed method significantly outperforms the next best DeepLabv3+ method in the IoU and PA metrics by nearly 5%; it achieves the best performance in the Precision of 75.78%. In addition, the proposed method’s Recall reaches 95.54% and F1-score reaches 84.52%, which is better than several other methods. Therefore, from the quantitative results, the proposed method achieves the best performance. One can observe that the proposed method needs some time to search for the optimal subset of bands in an iterative fashion. Nevertheless, our method can select a subset of bands to detect edges that result in more accurate segmentation performance compared with other methods. We compare this time with the typical time scales of the overall textile hyperspectral imaging processing workflow. In a textile digitalization pipeline, the time required for HSI data acquisition is approximately one and a half minutes, far longer than the time. Thus, the computational time of our algorithm does not become a bottleneck in the entire workflow. Furthermore, we believe that with the improvement of computing power and the wide use of high-performance computing, the execution time of the proposed method is not a critical issue.

A qualitative comparison was made among our proposed vector-based HSI edge detection method, the image boundary detection method45, and two top-performing alternatives: TEED, and DeepLabv3+, as shown in Fig. 13. Figure 13 contains samples with diverse inherent contrast characteristics. In high-contrast cases, such as the vivid peony patterns in the second row, our edge detection results maintain sharp boundaries. Both our method and method45 achieved satisfactory results, which attained segmentation PA exceeding 98%. However, DeepLabv3+ failed to distinguish the peony floral patterns from the background, resulting in significant misclassification. When processing images where the pattern and background colors are similar and edges are less distinct—such as the eight treasures patterns on dark backgrounds—the method45 missed certain pattern edges, leading to segmentation failure. Our method successfully captures fine edges. Such performance confirms the robustness of our method in low-contrast scenarios. Therefore, from the qualitative image results, the proposed method can detect pattern edges effectively under different backgrounds, which is superior to the other seven methods.

Discussion

We propose a band selection algorithm for HSIs, which is called edge-oriented MO of band selection (EOMOBS). This model simultaneously involves two factors, including information and redundancy, which can better describe the characteristics of the bands in HSI. The edge-oriented evaluation mechanism is constructed to select the final solution from the Pareto front, so the selected band subset is more conducive to edge detection. After band selection, the improved Canny algorithm is used for edge detection in textile hyperspectral images for pattern segmentation. The method fuses information from multiple channels from EOMOBS through vector calculation and automatically selects optimal high and low thresholds according to image characteristics, offering better adaptability than the traditional Canny operator. Compared with seven edge detection methods on HSIs and two methods for RGB, our method demonstrates better edge detection performance. When applied to textile pattern segmentation with low contrast and noise, it achieves 93.74% PA and 73.19% IoU, outperforming the other seven methods, including Unet and DeepLabv3+.

Traditional textile patterns, as an important part of cultural heritage, carry rich historical and cultural connotations. The accurate segmentation of these patterns is crucial for the digital preservation and in-depth study of cultural heritage. Our algorithm enables the precise extraction of low-contrast and noisy textile patterns, which provides the necessary technical support for constructing a comprehensive database of traditional textile patterns. Moreover, the successful application of this algorithm in textile pattern segmentation paves the way for similar digital research on other types of cultural heritage. Cultural heritage artifacts beyond textiles often share key HSI characteristics with textile data. Typical examples of these artifacts include ancient murals, painted pottery, and paintings with pigmented patterns. First, they contain delicate, meaningful boundaries that require precise detection. For instance, the edge of a figure in a mural and the contour of a decorative motif on pottery both fall into this category of boundaries. Second, their hyperspectral data may include redundant bands. Third, they are susceptible to noise from aging; common aging-related noise includes pigment fading and surface cracks. All these aspects are challenges that our framework is designed to address. This demonstrates the potential of HSI-based segmentation techniques in promoting the digitalization process of cultural heritage.

Data availability

Relevant researchers may acquire the data and materials that substantiate the conclusions of this study by contacting the corresponding author if they are required for scientific research.

References

Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., Qi, L., Zhang, J. & Zhang, T. Research on the co-occurrence feature mining of the Qing dynasty embroidery patterns based on temporal multilayer networks. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 228 (2025).

Li, H., Liu, W. & Li, X. Construction of basic-element database for traditional Chinese culture in industrial design. Procedia Comput. Sci. 91, 1011–1017 (2016).

Meng, K. et al. Database construction and remodeling method on traditional Yi nationality patterns of China with the Gan model. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 181 (2025).

Kleynhans, T., Schmidt Patterson, C. M., Dooley, K. A., Messinger, D. W. & Delaney, J. K. An alternative approach to mapping pigments in paintings with hyperspectral reflectance image cubes using artificial intelligence. Herit. Sci. 8, 1–16 (2020).

Zhao, H. et al. Dating of Jingdezhen blue and white porcelain based on transfer learning and imaging spectroscopy techniques. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 68 (2025).

Zeng, Z. et al. Virtual restoration of ancient tomb murals based on hyperspectral imaging. Tech. Rep. 1 (2024).

Herens, E., Defeyt, C., Walter, P. & Strivay, D. Discovery of a woman portrait behind la violoniste by Kees van Dongen through hyperspectral imaging. Herit. Sci. 5, 1–8 (2017).

Zheng, Q. et al. Extraction method of Yuan blue and white porcelain pattern based on multi-scale retinex and histogram multi-peak threshold segmentation. Herit. Sci. 12, 211 (2024).

Yao, Q., Zhou, Y., Tang, C., Xiang, W. & Zheng, G. End-to-end hyperspectral image change detection based on band selection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–14 (2024).

Ou, X., Wu, M., Tu, B., Zhang, G. & Li, W. Multi-objective unsupervised band selection method for hyperspectral images classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 1952–1965 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. A novel framework combining band selection algorithm and improved 3d prototypical network for tree species classification using airborne hyperspectral images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 219, 108813 (2024).

Zhang, L., Wei, Y., Liu, J., Wu, J. & An, D. A hyperspectral band selection method based on sparse band attention network for maize seed variety identification. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122273 (2024).

Fu, B., Sun, X., Cui, C., Zhang, J. & Shang, X. Structure-preserved and weakly redundant band selection for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 17, 12490–12504 (2024).

Yong, Z., Chun-lin, H., Xian-fang, S. & Xiao-yan, S. A multi-strategy integrated multi-objective artificial bee colony for unsupervised band selection of hyperspectral images. Swarm Evolut. Comput. 60, 100806 (2021).

Deb, K., Pratap, A., Agarwal, S. & Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 6, 182–197 (2002).

Ghamisi, P., Couceiro, M. S., Martins, F. M. & Benediktsson, J. A. Multilevel image segmentation based on fractional-order darwinian particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 2382–2394 (2013).

Zeng, S., Wang, Z., Huang, R., Chen, L. & Feng, D. A study on multi-kernel intuitionistic fuzzy c-means clustering with multiple attributes. Neurocomputing 335, 59–71 (2019).

Tarabalka, Y., Chanussot, J. & Benediktsson, J. A. Segmentation and classification of hyperspectral images using watershed transformation. Pattern Recognit. 43, 2367–2379 (2010).

Lv, Z. Y., Zhang, P., Benediktsson, J. A. & Shi, W. Z. Morphological profiles based on differently shaped structuring elements for classification of images with very high spatial resolution. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 7, 4644–4652 (2014).

Ozturk, N. & Ozturk, S. Comparison of image segmentation methods. In 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing (IDAP), 1–4 (IEEE, Malatya, 2018).

Yu, H. et al. Multiscale superpixel-level subspace-based support vector machines for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 14, 2142–2146 (2017).

Ozturk, N. & Ozturk, S. A new image enhancement method based on segmentation. Eur. J. Sci. Technol. 975–981 (2021).

Ozturk, N. & Ozturk, S. A new effective hybrid segmentation method based on c–v and lgdf. Signal, Image, Video Process. 15, 1313–1321 (2021).

Bai, J. et al. Hyperspectral image classification based on superpixel feature subdivision and adaptive graph structure. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–15 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Spiking-lstm: A novel hyperspectral image segmentation network for sclerotinia detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 226, 109397 (2024).

Martin, D. R., Fowlkes, C. C. & Malik, J. Learning to detect natural image boundaries using local brightness, color, and texture cues. IEEE Trans. pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 26, 530–549 (2004).

Sun, G. et al. Gravitation-based edge detection in hyperspectral images. Remote Sens. 9, 592 (2017).

Lei, T., Fan, Y. & Wang, Y. Colour edge detection based on the fusion of hue component and principal component analysis. IET Image Process. 8, 44–55 (2014).

Chen, M., Yi, S., Wu, L., Yin, H. & Chen, L. Highly robust thermal infrared and visible image registration with canny and phase congruence detection. Opt. Lasers Eng. 183, 108526 (2024).

Shang, X., Cui, C. & Sun, X. Spectral-spatial hypergraph-regularized self-representation for hyperspectral band selection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 20, 1–5 (2023).

Zhang, M., Gong, M. & Chan, Y. Hyperspectral band selection based on multi-objective optimization with high information and low redundancy. Appl. Soft Comput. 70, 604–621 (2018).

Saqui, D., Saito, J. H., De Lima, D. C., Cura, L. M. D. V. & Ataky, S. T. M. Incorporated decision-maker-based multiobjective band selection for pixel classification of hyperspectral images. Adv. Electr. Compu. Eng. 19, 21–28 (2019).

Hu, P., Liu, X., Cai, Y. & Cai, Z. Band selection of hyperspectral images using multiobjective optimization-based sparse self-representation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 16, 452–456 (2018).

Wan, Y., Zhong, Y., Ma, A. & Zhang, L. Hyperspectral remote sensing image band selection via multi-objective sine cosine algorithm. In IGARSS 2019-2019 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 3796–3799 (IEEE, Yokohama, 2019).

Zhao, H., Bruzzone, L., Guan, R., Zhou, F. & Yang, C. Spectral-spatial genetic algorithm-based unsupervised band selection for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 59, 9616–9632 (2021).

Song, M., Liu, S., Xu, D. & Yu, H. Multiobjective optimization-based hyperspectral band selection for target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–22 (2022).

Canny, J. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 8, 679–698 (1986).

Ozturk, N. & Ozturk, S. Efficient and natural image fusion method for low-light images based on active contour model and adaptive gamma correction. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 48437–48456 (2024).

Xin, G., Ke, C. & Xiaoguang, H. An improved Canny edge detection algorithm for color image. In IEEE 10th International Conference on Industrial Informatics, 113–117 (IEEE, Beijing, 2012).

Xuan, L. & Hong, Z. An improved Canny edge detection algorithm. In 2017 8th IEEE international conference on software engineering and service science (ICSESS), 275–278 (IEEE, Beijing, 2017).

Minaee, S. et al. Image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 3523–3542 (2021).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention, 234–241 (Springer, Cham, 2015).

Zhao, H., Shi, J., Qi, X., Wang, X. & Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2881–2890 (IEEE, Honolulu, 2017).

Chen, L.-C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 801–818 (Springer, Munich, 2018).

Al-Khafaji, S. L., Zhou, J., Bai, X., Qian, Y. & Liew, A. W.-C. Spectral-spatial boundary detection in hyperspectral images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 499–512 (2021).

Soria, X., Li, Y., Rouhani, M. & Sappa, A. D. Tiny and efficient model for the edge detection generalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 1364–1373 (IEEE, Paris, 2023).

Su, Z. et al. Pixel difference networks for efficient edge detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 5117–5127 (IEEE, Montreal, 2021).

Soria, X., Sappa, A., Humanante, P. & Akbarinia, A. Dense extreme inception network for edge detection. Pattern Recognit. 139, 109461 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the editors and reviewers for their professional advice on revisions, which led to a significant improvement in the quality of the article. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Project for Xiong’an New Area (No. 2023XAGG0089), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62522502, 62371056), Major Science and Technology Support Program of Hebei Province (No. 252X1701D), Sponsored by Beijing Nova Program, Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KJZD20230923115202006), the Fund of State Key Laboratory of Information Photonics and Optical Communication BUPT (No. IPOC2025ZZ02), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. 530424001, 2024ZCJH13).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.Z., Z.Y., and K.X.; methodology: Y.Z. and Z.Y.; analysis: Y.Z. and Z.Y.; software: Y.Z.; data preparation: Y.Z., T.Z., L.L., Y.L, C.Q., and Z.Y.; writing-original draft preparation: Y.Z.; writing-review and editing: Y.Z., Z.Y., Y.Z., H.Z., L.C. and T.Z.; visualization: Y.Z. and Z.Y.; supervision: Z.Y., Y.Z., H.Z., T.Z., and K.X.; project administration: Z.Y., Y.Z., H.Z., T.Z., and K.X.; funding acquisition: Z.Y., Y.Z., H.Z., T.Z., and K.X. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Yu, Z. et al. Multi-objective band selection algorithm based on NSGA-II for pattern segmentation of textile hyperspectral images. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 617 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02176-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02176-x