Abstract

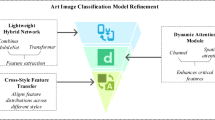

The preservation of cultural artifacts is vital for maintaining historical continuity, particularly for traditional Chinese paintings that often suffer from decay and damage over time. Existing inpainting methods struggle to simultaneously recover complex brushwork structures, maintain visual coherence, and preserve consistency across multiple resolutions. To address these challenges, we present the Twin Cascade Spatial Multi-scale Attention Filtering (TCSMAF) method, which adopts a symmetric multi-scale dual-branch architecture to capture complex structures and semantic details through parallel processing. A Spatial Kernel Module is proposed to enhance spatial perception by coordinating hierarchical features with spatial coordinate encoding. Moreover, a Multi-scale Spatial and Channel Attention module that adopts progressive convolution kernel sizes is introduced to improve texture reconstruction by leveraging features across different scales and channels. These technical innovations significantly advance digital inpainting methodologies, providing a robust framework specifically designed to handle the intricate textures and details of damaged paintings. The dataset and code are available at https://github.com/LPDLG/TCSMAF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional Chinese paintings and murals are not only significant carriers of Chinese civilization but also invaluable treasures of world cultural heritage. Through a unique artistic language, they document the historical transformations, social customs, and spiritual beliefs of the Chinese nation, holding an important place in the history of world art. Encompassing diverse media such as silk and paper, and employing a rich variety of techniques including meticulous gongbi and expressive xieyi styles, these works embody exquisite brushwork and profound cultural connotations. They serve as essential tangible materials for the study of Chinese history, philosophy, aesthetics, and social development. However, over the course of time, natural weathering, environmental changes, and human activities have led to common deterioration phenomena such as fading, cracking, flaking, and scratching, placing the original artistic brilliance and historical information at risk of irreversible loss. Representative sites such as the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, for example, exhibit severe problems of flaking, discoloration, and surface damage due to their long history. These artworks not only possess great cultural heritage value in the fields of art history and archaeology but also offer new opportunities for the permanent preservation and broad dissemination of China’s outstanding traditional culture. Protecting and restoring these precious works is thus not only essential for the continuation of the artworks themselves but also a vital measure for preserving national cultural memory and safeguarding humanity’s shared cultural heritage. With the development of deep learning, digital inpainting methods are beginning to appear in heritage conservation. Pathak et al.1 employed Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) to learn deep semantic information from images, successfully achieving large-scale image inpainting. Since then, have used more sophisticated networks or learning methods to generate high-fidelity images, including style transfer2, Transformer3, context attention4, fourier convolution5, and extended convolution6.

In addition, Deng et al.7 utilized fast fourier transform convolution8 to enhance the expression of key image features and filter noise to restore the missing structures in murals. Compared to mural inpainting, there has been relatively less research on the inpainting of traditional Chinese paintings. Xu et al.9 applied edge detection algorithms and employed a foreground-background layering inpainting method to restore ‘Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains’ extending research in this field.

Figure 1 presents three traditional Chinese paintings and murals restored by artificial intelligence: the Jade Emperor from the ‘Audience with the Supreme Deity’ fresco, a ‘Dunhuang Mogao-cave mural’, and the ‘Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains hand-scroll’. Despite advancements in generating realistic content, applying existing image inpainting methods to restore the nuances of historical artworks remains a significant challenge.

-

1.

Existing methods are unable to recover the complex structure and semantic-level understanding. As reported in RePaint10, diffusion-based pipelines tend to lose high-frequency brush details when the damaged area becomes extensive, yielding completions that are structurally plausible yet semantically implausible.

-

2.

Some inpainting methods may generate unrealistic details for the missing areas, causing the restored image to appear visually incoherent and inconsistent. Guo et al.11 observe that kernel-prediction networks often hallucinate modern textures absent from the original artwork, producing noticeable stylistic clashes.

-

3.

Existing methods cannot achieve the same repair effect on multi-resolution images. Sun et al.12 demonstrate that state-of-the-art GANs exhibit a marked drop in perceptual fidelity when the same defect is evaluated at different resolutions, a scale-sensitivity that manual restorers routinely overcome through adaptive repainting.

To solve these problems, we propose a Twin Cascade Spatial Multi-scale Attention Filtering Inpainting of Traditional Chinese Painting, termed TCSMAF. Our contributions are as follows:

-

1.

The symmetric cascade architecture (CSDB) is proposed to enable mutually refining branches across three scales. One branch dynamically generates location-adaptive filters, while the other applies them stage by stage. This design expands the receptive field and effectively balances large-area structure reasoning with parameter efficiency. CSDB provides a strong foundation for future enhancements, such as coordinate injection and attention re-weighting.

-

2.

The Spatial Kernel Module (SKM) is proposed to integrate pixel-level coordinate encoding into filter generation. It concatenates normalized (X, Y) maps with intermediate features, thereby providing location priors for missing regions. This design gives every 3 × 3 kernel spatial awareness, improving the restoration of missing image regions. SKM transforms the traditional brush-position rule into an end-to-end, data-driven prior, advancing heritage inpainting towards greater intelligence.

-

3.

The Multi-Scale Spatial and Channel Attention (MSCA) is proposed to preserve ink-wash hierarchies across different scales. It employs progressively sized convolutions combined with a joint spatial-channel attention block. After kernel application, MSCA re-weights both the “where" and the “what", effectively distinguishing high-frequency brush details from low-frequency color washes. MSCA can also serve as a plug-and-play upgrade for any U-Net decoder, providing a flexible solution for image inpainting tasks.

Traditional Chinese painting is an important component of China’s cultural heritage, carrying profound historical information and unique artistic value. Ancient paintings were often created on lightweight materials such as silk, paper, and hemp cloth, encompassing various techniques including meticulous gongbi and freehand xieyi styles. Their subjects span landscapes, flowers and birds, and human figures, reflecting the craftsmanship of ancient painters and the aesthetic concepts of their era. Murals, on the other hand, were painted directly onto the surfaces of buildings such as temples, grottoes, palaces, and tombs, blending harmoniously with the architectural space. They typically employ grand narrative compositions and vivid colors to depict religious beliefs, historical events, mythological tales, and scenes of everyday life. Both serve as tangible evidence in the history of Chinese art and are valuable historical materials for studying the politics, economy, religion, and cultural exchanges of ancient society. However, due to prolonged exposure to complex natural environments and human activities, ancient paintings and murals commonly exhibit various forms of degradation such as fading, flaking, cracking, and mildew, leading to the continual loss of their original artistic brilliance and historical information.

The traditional restoration of ancient paintings and murals is carried out manually, a highly complex and rigorous scientific task that relies on the restorer’s extensive experience and refined skills13. In ancient painting restoration, restorers usually work directly on the original artifact, performing steps such as cleaning, paper mending, color retouching, and full-color restoration. While this can achieve an immediate “restoration to its former state”, it inevitably risks diminishing the original patina and historical ambience in subtle ways14. Even for highly experienced practitioners, localized color retouching may weaken the antique aesthetic due to different aging rates of pigments15. Excessive consolidation or operational errors during processes such as edge joining and paper patching may cause localized stress imbalance in the paper, resulting in secondary damage16. When the damaged area is large or the fiber orientation is complex, differences in thickness and laid line patterns between the patched paper and the original can become more pronounced, leading to rapid accumulation of color and texture discrepancies, and significantly reducing the overall visual coherence17. In cases of silk-based polychrome paintings with thick mineral pigment layers and severe cracking, experience-based retouching is more prone to cumulative color mismatches, further degrading the visual texture18.

In mural restoration, the process generally includes consolidation, cleaning, reattachment of detached layers, and filling and coloring of missing areas. For example, in the case of pigment layer flaking, restorers may use specially formulated adhesives for fixation. For areas of image loss, techniques such as ‘filling without painting’ or ‘virtual restoration’ with recognizable lines and light colors are applied to maintain historical authenticity19. However, these physical restoration methods are irreversible, and the process may inadvertently introduce the personal style of the restorer, making it difficult to fully reproduce the original artistic essence20. Moreover, for murals with large-scale or severe damage, physical restoration is often powerless. Figure 2 displays three artificially restored traditional Chinese paintings and murals: Herdboy Tending Cattle, Herdboy Leading Water Buffalo, and the Song-dynasty silk scroll Portraits of Confucius’ Disciples.

With the development of digital technologies, non-contact digital restoration has become an important supplementary and alternative approach. Early digital restoration relied mainly on manual cloning and stamp tools operated by experts21. While avoiding direct intervention on the artifact itself, this approach is inefficient, highly subjective, and heavily dependent on the artistic skills of the operator. Subsequently, texture synthesis-based algorithms, such as PatchMatch22, were introduced into the field of image inpainting. These methods fill missing regions by searching for best-matching patches from intact areas of the image. Although they perform reasonably well on repetitive textures, they often produce structural disorder and semantic mismatches when dealing with culturally significant artworks like traditional Chinese murals, which are characterized by complex structures and abstract content, thus failing to meet the requirements for high-fidelity restoration. This has driven the ongoing development and application of scalable, high-fidelity digital restoration techniques.

Although manual restoration retains irreplaceable value in terms of microscopic bonding and material authenticity, it still faces fundamental limitations such as low efficiency, poor repeatability, and difficulty in objective quantification when dealing with large-scale losses, complex textures, and multiple forms of degradation. These limitations have fueled research and application of scalable, high-fidelity digital restoration technologies.

In the field of cultural heritage image restoration, how to maximize the preservation of the original artistic value of a work has always been a central challenge. In recent years, deep learning methods have achieved remarkable progress in image inpainting. Early restoration approaches, such as Context Encoders1 and DeepFill23, leveraged Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)24 to learn the deep feature distribution of images, thereby generating semantically plausible content to fill missing regions. These methods have been successful in natural image restoration and have inspired subsequent studies targeting the restoration of artworks. For example, Shi et al.12 developed the Ref-ZSSR network based on GANs, which exploits the global information within the painting itself to restore damaged ancient artworks. However, the training process of GANs is often accompanied by mode collapse and instability, and the generated texture details may sometimes exhibit artifacts, making it difficult to fully capture the delicate brushstrokes and material texture characteristic of Chinese ancient paintings.

Additionally, the Vision Transformer (ViT) has shown superior performance in handling large datasets, further expanding its application in image inpainting3. Some works25 have also achieved good results. Fourier convolution, which leverages frequency-domain of inpainting information6. Dilated convolution5, aimed at expanding the receptive field without increased computational cost also improve inpainting quality. Moreover, context attention mechanism plays an important role in image inpainting. Zhang et al.4 proposed a method that better captures both global and local information.

In the realm of mural restoration, the emergence of denoising diffusion models26 has inaugurated a new paradigm for high-quality image synthesis and inpainting. By simulating a progressive “ordered-disordered-ordered” denoising process, these models are capable of generating images that are both highly detailed and perceptually convincing. Nagar et al.27 first adapted diffusion models to the restoration of mural artworks, effectively addressing diverse degradations such as noise, blur, and fading. Inspired by this line of work, subsequent studies focusing on traditional Chinese art have flourished. For instance, Lyu et al.28 introduced the CLDiff model, which leverages diffusion-based techniques for super-resolution of Chinese landscape paintings. through an integrated attention mechanism, CLDiff successfully reconstructs high-resolution images exhibiting clear ink-wash textures.Zhu et al.29 proposed leveraging diffusion knowledge for generative image compression with fractal frequency-aware band learning, which highlights the potential of frequency-domain enhancement in restoration tasks. Similarly, Lu et al.30 introduced a diffusion-based bit-depth expansion approach, demonstrating how diffusion processes can effectively recover information lost due to quantization. These studies suggest that diffusion frameworks may complement spatial filtering and coordinate injection strategies, offering promising directions for heritage image restoration that require both global coherence and high-frequency detail preservation.

Despite the remarkable achievements of the aforementioned generative approaches in restoring ancient paintings and murals, they typically treat structure, content, and style as an entangled whole during learning, thereby lacking explicit disentangled control over these distinct attributes. When confronted with Chinese murals characterized by highly variable styles and unique compositions, existing models are prone to style drift or structural distortion, struggling to simultaneously preserve structural fidelity and stylistic consistency. Moreover, only a limited number of methods have focused on refining spatial feature extraction to better capture complex semantic information and delicate artistic details. To address these challenges, we propose a filtering-based restoration framework enhanced with a multi-scale convolutional kernel architecture, aiming to strengthen feature extraction capabilities.

Currently, image inpainting methods typically rely on searching for similar information to restore missing content. However, this method overly relies on low-level features and cannot synthesize similar patches that do not exist in the known image context.

Some studies have attempted to adopt filtering methods to restore image information, such as denoising31, deblurring32, and rain removal33. These methods have achieved significant results in specific visual tasks, especially in reducing image noise and artifacts. Guo et al.11 were the first to apply deep filtering prediction to natural image inpainting tasks, effectively improving local artifacts in images and enhancing inpainting quality. Moreover, Li et al.34 employ dual-stream network made strides in restoring semantic integrity and fine details.

Although these methods have shown promise, filtering-based approaches still struggle to fully capture complex spatial and channel-wise dependencies within images. To address this limitation, we introduce a multi-scale spatial-channel attention mechanism. This approach effectively integrates both local and global information, thereby improving the synthesis of missing content and enhancing overall inpainting quality.

Methods

Overall framework

As shown in Fig. 3, Twin Cascade Spatial Attention Filtering Inpainting completes the inpainting process by obtaining the input data through the filter kernel prediction branch and the filter operation branch at the same time35.

The filter kernel prediction branch uses a U-Net structure36 to predict filter parameters for missing regions. Combining the outputs of the upper CNN encoder with feedback from the lower CNN encoder to generate filter features, which are then fused with the spatial encoding of predicted features to enhance the ability to understand missing pixel locations and overall image layout. Additionally, a multi-scale spatial and channel fusion attention mechanism is introduced to address the loss of feature channels and spatial information caused by downsampling. Attention weights are extracted from the input features to improve the focus on key areas, expanding feature coverage and enhancing inpainting and spatial filtering.

The filter kernel operation branch uses the U-net structure network to encode the hierarchical features of the image at different scales layer by layer. The spatial filter kernel of different scales predicted from the upper layer for stage inpainting several times. Then, the inpainting result is sent back to the upper layer for a new round of filtering kernel prediction, and the missing area is restored repeatedly.

Spatial Kernel module

The method of predictive filtering is to estimate the missing or damaged pixels by using the numerical information of the neighborhood pixels. It then predicts the value of the missing pixels, and reconstructs the image.

where \(\widehat{{I}_{q}}\) represents the pixel of the missing region. Kw belongs to the filter kernel. Kw ∈ RK×K representing the size of K. ω represents the learnable filter kernel parameter. Ip represents the adjacent pixel of the missing region.

The predictive filtering method uses a deep convolutional network to learn appropriate parameters, dynamically adjusting the filter kernel:

where K represents the variable filter kernel. \(\widetilde{I}\) represents the damaged image. Fθ represents the filter prediction network. θ represents the learnable parameter.

In order to recover these high-frequency details, TCSMAF extracts image features of different levels layer by layer by setting four CNN encoders. Including convolutional, normalization, and activation layers in the lower branches, it feeds back to the kernel prediction branch. The resulting missing image is input into both branches of the network at the same time. The network gradually learns the complex and abstract feature representation. Specifically, for a given image of a traditional painting that is obscured \(\widetilde{I}\).

where I, Im ∈ RH×W×C represent the original image and the mask image, respectively. \(\widetilde{I}\) represents the obscured image.

The lower branch accepts the missing image as \(\widetilde{I}\), and the image features are mapped from RGB space to feature space by the lower CNN encoder, and the output features Fi are obtained. The Avgpool layer to downsample the feature map size to preserve the important features. Then, Fi is feed into the filter kernel prediction branch.

where \({E}_{D}^{i}\in {R}^{\frac{H}{2i}\times \frac{W}{2i}\times \frac{C}{2i}}\) represents encoding characteristics of the underlying output. φi( ⋅ ) represents the i stage coding operation of the lower layer. Avgpool( ⋅ ) represents a global averaging pooling operation.

At the same time, the filter kernel prediction branch takes the features obtained from the lower layer \({E}_{D}^{i}\) and output characteristics of the self-encoder \({E}_{U}^{i}\). After splicing, the output filter features \({E}_{F}^{i}\) are then obtained by an upper layer encoder and fed into the SKM to generate the spatial filter kernel for that stage, which can be represented as:

where Ki represents the spatial filtering kernel for stage i. ξi( ⋅ ) represents the coding operation of the spatial filter prediction branch. δSKM( ⋅ ) represents a spatial coding operation. Finally, the next branch uses the obtained spatial filter kernel to perform filtering operations to complete this phase of the inpainting, this process can be represented as:

where Ee represents the output of the last encoding of the next branch. ↓ represents the downsampling through the global average pooling layer. Ee is the coded feature obtained from the generative branch through multiple spatial filtering operations, which is finally decoded by the decoder to get the final inpainting result.

Spatial encoding fusion

In order to enhance the ability to know the spatial structure37, the input predictive filter features are spatially encoded using the SKM module to obtain the coordinate information of the missing pixels. In this way to provide spatial a priori information for the predicted filtering, so that the network pays more attention to the relative position of the missing region in the picture during the convolution operation, thus better capturing the spatial structure and local features in the image. Specifically, the SKM module first receives a filtering feature E output from the upper layer, which is encoded to obtain the coordinate information of the generated X, Y directions, which can be expressed as:

where Xi ∈ RB×H×1×1, Yi ∈ RB×1×W×1 indicated that the i stage is encoded in the X and Y directions, respectively, to obtain the coordinate information. \({E}_{({h}_{dim},{w}_{dim})}\) indicates the filter feature map of the i prediction input.

Secondly, the feature filtering features are spliced with the coordinate information in the X, Y directions and the coordinate information is fused using a single layer convolution. Finally, the key feature regions are activated using the ReLU function to obtain the spatial filtering kernel \({\widehat{K}}_{i}\). This process can be expressed as:

where \({E}_{F}^{i}\) represents the predictive filter features. Conv( ⋅ ) and ReLU( ⋅ ) represent the 3 × 3 convolution operation and activation layer, respectively. \({\widehat{K}}_{i}\) represents the spatial filter kernel obtained by the second predictive filter.

Multi-scale spatial and channel attention

We propose a Multi-scale Spatial and Channel Attention (MSCA) module to enhance the downsampled image feature matrix Eh×c×w. The MSCA module processes the features through four parallel branches. Each branch extracts key features Fi using convolution with a different-sized kernel βi×i( ⋅ ), where i varies to achieve multi-scale feature extraction. After convolution, the Spatial Channel Attention (SCA) mechanism optimizes these features, resulting in enhanced outputs \({\mathop{F}\limits^{\sim}}_{i}\). The formula is as follows:

where εSCA( ⋅ ) represents the processing through the SCA module.

The SCA module processes the image features E obtained through convolution to produce new image features \({\mathop{F}\limits^{\sim}}_{i}\). Specifically, the input image features are first further extracted through convolution operations. Secondly, the result βK×K( ⋅ ) is element-wise multiplied with the original convolution output. Finally, the resulting features \(\check{F}\) are then element-wise multiplied with the previously obtained new features, ultimately yielding the optimized image features \({\mathop{F}\limits^{\sim}}_{i}\). This process can be expressed as:

where φSAM represents the features by the SAM module. ζCAM represents the features by the CAM module. E represents the image features.

The CAM module performs Maxpooling and Avgpooling operations on the input features. After that, be fed into the SharedMLP module. Two new features are operated addition ⊕ and then activated by the Sigmoid activation function. The process can be expressed as:

where Sig( ⋅ ) represents the Sigmoid activation. θ( ⋅ ) represents the fully connected operation of SharedMLP. Max( ⋅ ) and Avg( ⋅ ) represent the max pooling and average pooling operations, respectively. F1 represents the image features.

The SAM module convolutes the input image features and then activates by the Sigmoid function.

where \(\widehat{F}\) represents the image features processed by the CAM module.

Loss function

To ensure the accuracy and fidelity of the inpainting results while preserving the original appearance of the artwork, we use the L1 loss L1, perceptual loss38Lper, adversarial loss24Ladv, and style loss39Lstyle to guide inpainting. The optimisation objective of the whole network is the weighted combination of the above losses can be expressed as:

where λ1, λper, λadv and λstyle. The hyperparameters were set separately during the experiment as λ1 = 1, β = 1, λper= 250, λadv= 0.1.

Datasets

To enhance image inpainting, we use natural images as auxiliary training data due to the scarcity of mural resources. We employ five datasets:

MaskCLP obtained from relevant cooperative research institutions, contains 8273 Chinese hanging/hand scrolls dated from the Five Dynasties to the Qing dynasty, comprising 4032 gongbi and 3241 xieyi works with an average resolution of 1080 × 1920 pixels. Missing-region masks are generated through a conservator-AI collaborative pipeline: professional restorers first outline real cracks and flakes on a 1000-image subset; an auxiliary segmentation model, trained on these labels, predicts potential damage for the remainder. The resulting 12,000 irregular masks are verified by the same experts. The collection is stratified by dynasty and brush style, and divided into 7446 training, 1000 validation, and 827 testing images, all cropped to 256 × 256, ensuring heterogeneity and representativeness.

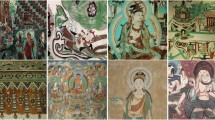

MuralVerse is a dataset that we have proposed, capturing the diverse artistic heritage of China through a collection of murals, comprising 1396 extended and cropped images of Dunhuang murals, 2335 images of Gansu murals, 2950 images of Hebei murals, and 1482 images of Inner Mongolia murals, as illustrated in Fig. 5. All images are cropped to a resolution of 256 × 256 and divided into training, validation, and test sets in a ratio of 8:1:1. The images in this dataset were sourced from collaborating institutions and curated digital art repositories. Professional artists were invited to meticulously categorize the murals, considering variations in style, dynastic provenance, and chromatic characteristics to ensure a comprehensive representation of stylistic diversity. The selected paintings underwent rigorous screening and classification to guarantee both the heterogeneity and representativeness of the dataset.

CelebA released by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, this public benchmark provides over 180,000 celebrity faces annotated with 40 binary attributes (ethnicity, age group, expression, etc.). Images are center-cropped to 256 × 256 and split into 162,770 training and 19,962 testing samples. We adopt the official partition without modification.

Places240 is a large-scale scene repository that we utilize, released by MIT, containing 1.8 million RGB images across 365 scene categories. The official split provides 1.62 million training and 180,000 testing images, all center-cropped to 256 × 256. We use the provided partitions for pre-training and general scene evaluation, with model tuning based on training performance.

Painter By Numbers41 released by Kaggle in 2016, this public benchmark contains 103,093 high-resolution paintings accompanied by painter and genre annotations. The official split provides 79,433 training and 23,660 testing images, all center-cropped to 256 × 256 pixels, which we adopt without modification. No separate validation set was constructed, and hyperparameters were tuned solely according to training performance.

Ethics statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available and has received the necessary approval for use. All images, videos, and associated personal information are published in accordance with the licensing terms of the dataset, and the researchers have adhered to the terms provided by the dataset’s publisher. Since the dataset is publicly accessible and includes content with the required authorization, we confirm that the individuals involved have provided consent at the time of dataset publication.

Implementation details

The TCSMAF network was completed on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU with a training time of 74 hours and a total of 500,000 iterations. During training, the learning rate is set to 0.0001, the batch size is 12. The Adam optimizer42 is used to train the model, with the parameters β1 = 0.1 and β2 = 0.9.

Evaluation metrics

We follows the most common evaluation settings in image inpainting tasks, using Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR)43, Structural Similarity Index (SSIM)44, L1 distance, and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS)45 to assess the quality of image inpainting. PSNR measures pixel-wise fidelity, where higher is better; SSIM evaluates luminance, contrast and structural similarity, where higher is better; L1 distance records the mean absolute error, where lower is better; LPIPS computes deep-feature distance and aligns with human perception, where lower is better.

Results

Comparison on MaskCLP

Compared with other methods, our TCSMAF model achieves the best results for damaged images with masks at three different ratios. The comparative results are presented in Table 1, where four evaluation metrics are provided for six models, compared to the original image. Figure 4 presents a visual comparison of various methods on the MaskCLP dataset, displaying both full images and magnified local details. The selected samples represent some of the most challenging cases in traditional Chinese painting restoration. For instance, in the first image, the mountain area exhibits mask-induced breaks in the axe-split texture strokes and the loss of mineral-green pigment patches, revealing a blank background. In the fourth image, the crab-claw branch tips are entirely removed by the mask, leaving a white band devoid of any information. These cases simulate realistic damage patterns commonly encountered in digital inpainting tasks, such as artificially masked pigment exfoliation and silk-fiber loss. TCSMAF successfully reconstructs stroke continuity and ink-wash gradients, whereas other methods either over-smooth the texture or introduce visible seams.

a Input: original heritage image with missing areas; b Mask: 20−30% region to be inpainted. c Ours: TCSMAF result showing restored brush continuity and natural colour transition. d AOT-GAN: overall tone preserved but local strokes appear blurred. e CoordFill: geometric structure recovered yet ink layers lack subtle gradation. f HAN: global coherence maintained, however, high-frequency details are smoothed. g MISF: large structure reasonable, yet fine filaments are discontinuous. h PConv: severe edge shift and hue deviation visible. The figures below (a1–h1) are the corresponding partially enlarged details.

HAN leverages a hybrid attention mechanism to maintain overall structural coherence, yet its sharpness diminishes at high-frequency details, and subtle color deviations render the chromatic distribution less natural. MISF excels in recovering large-scale structures via multi-scale information fusion, yet its restorations often appear coarse at the detail level, lacking the delicate layering of the original painting and exhibiting insufficient texture generalization. CoordFill demonstrates robust preservation of geometric structures. However, it is prone to generating repetitive texture patches or interrupted strokes in regions characterized by irregular artistic brushwork or gradual color transitions, thereby severing the restored region from its surroundings. AOT-GAN preserves global tone and overall consistency through contextual aggregation, yet it over-smooths local details, attenuating high-frequency information and yielding textures of insufficient clarity.

In contrast, the visual results produced by TCSMAF exhibit superior overall quality. In missing regions, the model generates continuous and natural brushstrokes, with local lines seamlessly connected. Transitions in color and luminance maintain the original tonal consistency and subtle gradients, avoiding abrupt color blocks or abrupt lighting discontinuities. Even in areas densely populated with high-frequency textures, zoomed-in details reveal crisp lines and rich textural layers that closely align with the visual characteristics of the original artwork. These visual comparisons convincingly demonstrate that TCSMAF surpasses existing methods in structural preservation, detail fidelity, and color consistency, thereby better reproducing the artistic texture and perceptual authenticity of traditional paintings.

Comparison on MuralVerse

To validate the applicability of our model to traditional mural restoration, we conducted a visual evaluation on the four distinct mural styles within the MuralVerse dataset, Temple murals, Thangka, Burial, and Cave. The results are presented in Fig. 5. This dataset comprises numerous ancient images characterized by intricate textures, delicate linework, and unique chromatic gradients, thereby imposing stringent demands on the restoration model’s ability to preserve fine details and faithfully reproduce color transitions.

TCSMAF demonstrates a high degree of fidelity in reconstructing complex garments, ornamental patterns, and border details. In the thangka examples, the golden filaments and motifs on the robes remain continuous and sharp, exhibiting well-defined color stratification. In temple murals, transitions between adjacent color blocks are rendered naturally, effectively avoiding abrupt chromatic discontinuities. Even in tomb and cave murals where the original images are severely damaged, the model is capable of synthesizing textures that harmonize with the prevailing style, thereby enhancing the overall visual coherence.

Upon closer inspection of the magnified local details, one observes that the brushstroke textures restored by TCSMAF closely match those of the original paintings. both fine linework and chromatic gradients retain commendable continuity, thus preserving the distinctive artistic ambience of the murals. Nevertheless, in regions where information loss is extreme, the model tends to produce slightly smoothed or stylistically simplified outputs; for instance, background textures may collapse into uniform color patches, and the intricacy of details is somewhat diminished. This observation indicates that further improvements are warranted for cases of extreme degradation.

Comparison on Places2

To further evaluate the model’s performance on natural scenes, Fig. 6 presents qualitative results on the Places2 dataset. This collection comprises a wide range of natural elements, such as lakes, snowfields, and mountain ranges, whose texture continuity and spatial coherence critically influence restoration quality. TCSMAF maintains remarkable global consistency when filling large missing regions. Over lake surfaces, the reconstructed reflections are highly consistent with the original image, eliminating chromatic irregularities. Snow-covered areas are restored with natural morphology and smooth luminance gradients, free from conspicuous artefacts. In scenes combining mountains and water, the model successfully completes both ridgelines and wave textures, yielding a coherent and unified composition. Upon magnification, the restored textures exhibit sharp structures and natural color transitions, devoid of abrupt color blocks or blurred boundaries. These observations confirm that TCSMAF is not only effective for artistic images with intricate structures and rich colors, but also capable of generating highly realistic results in natural-scene inpainting tasks.

Comparison on CelebA

To assess the generalization capability of our approach on facial images, Fig. 7 illustrates visual results obtained on the CelebA dataset. Facial images in this corpus typically encompass abundant fine-grained details, such as skin texture, facial contours, and hair boundaries, that are essential for perceptual authenticity and naturalness. It can be observed that TCSMAF harmoniously integrates the inpainted regions with the original structure. For instance, along the nasal bridge and periocular areas, the restored contours are smooth and seamlessly match the surrounding skin tone, exhibiting no discernible seams. In the mouth and cheek regions, the infilled details appear natural, with smooth skin-tone transitions that avoid abrupt chromatic or textural discontinuities. Zooming into local regions reveals that facial expressions remain intact and proportions are well preserved, resulting in a natural and coherent overall appearance. These visual results demonstrate that TCSMAF is capable of effectively recovering facial details and structures, producing visually compelling outcomes, and thereby offering empirical validation for cross-domain image restoration.

Comparison on painter by numbers

To further evaluate the generalization capability of TCSMAF on artistic paintings beyond traditional Chinese artworks, we conduct experiments on the Painter By Numbers dataset, which comprises 103,093 high-resolution oil paintings across diverse genres and styles. This dataset presents unique challenges due to its rich color palettes, varied brushstroke textures, and complex compositional structures, making it an ideal benchmark for testing the adaptability of inpainting models to Western artistic conventions. As shown in Fig. 8, TCSMAF effectively restores missing regions in oil paintings with high fidelity. In Impressionist works, characterized by loose, dynamic brushwork, our method reconstructs fragmented strokes while preserving the original rhythmic texture and color harmony. In portraits, fine details such as facial contours and fabric folds are seamlessly inpainted, maintaining anatomical consistency and tonal gradation. TCSMAF leverages its multi-scale attention mechanism to disentangle high-frequency brush details from low-frequency color washes. This ensures the coherent restoration of both intricate textures and broad color fields. These results validate the cross-cultural robustness of TCSMAF, bridging the gap between Eastern ink wash traditions and Western oil painting aesthetics.

User study

We selected approximately 40 art students and teachers as the participant group for our user study. The participants were informed that the evaluation criteria included the following aspects: (a) whether the generated output contained unresolved problems and how severe they were. (b) The degree to which the generated calligraphy matched artistic aesthetics. (c) Whether the generated results adhered to traditional calligraphy writing norms. (d) The creative and expressive quality of the generated output. Participants were asked to rate each criterion on a scale from 0 to 5, where 0 indicated the poorest performance and 5 represented the best. The mean scores across all participants were then calculated to determine the final performance score for each method. In this study, participants independently rated each indicator on a scale ranging from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating the lowest level and 5 the highest. The rating scores are directly proportional to the comprehensive ranking. The scoring mechanism is defined as follows:

where P is the number of participants who answered the question, fi denotes the frequency of the i-th option being selected, and wi represents the weight of the i-th option determined by its ranking.

Ablation study on the effectiveness of SKM and MSCA modules

The results of the components ablation study are shown in Table 2. It can be seen that the design of the spatial filtering kernel effectively complements the global feature information of traditional painting images and enhances the contextual reasoning ability, resulting in coherent structures and clear textures in the inpainting of complex images.

The visualization ablation results of the components are shown in Fig. 9. Initially, the corrupted image is presented, wherein the missing regions induce perceptible structural discontinuities and loss of fine details, thereby impairing the overall coherence of the scene. The corresponding mask explicitly delineates the areas requiring restoration, which frequently encompass critical structural information and high-frequency textures. Upon removing the Spatial Kernel Module (SKM), the model is still able to reconstruct the dominant structure within the missing areas. Nevertheless, the sharpness of local details deteriorates markedly, textures become overly smoothed, and color transitions exhibit slight blurring and irregularity, particularly along thin strokes and intricate motifs where fidelity is noticeably compromised. When both SKM and the Multi-scale Channel Attention module (MSCA) are ablated, the generated results suffer from a more pronounced degradation: the boundaries between restored and intact regions appear unnatural, conspicuous seams emerge at edges, local textures are excessively smoothed, and high-frequency details are almost entirely lost. In contrast, the complete TCSMAF model achieves optimal performance in structural integrity, detail fidelity, and color consistency, seamlessly and coherently filling the missing regions and yielding visual results that closely approximate the original image Fig. 10.

To disentangle the effects of spatial encoding and multi-scale attention, we perform a three-step ablation on the 20%−30% mask subset of MaskCLP. First, we remove only the Spatial Kernel Module while keeping progressive multi-scale attention intact; second, we retain coordinate encoding but replace progressive attention with a single-scale 3 × 3 convolution; third, we remove both modules simultaneously. Without SKM, edge-SSIM falls from 0.877 to 0.742, confirming that pixel-level coordinate injection is the dominant driver of edge continuity. Without MSCA, texture PSNR drops by 1.3 dB and HFEN decreases by 18%, indicating that progressive multi-scale attention is indispensable for recovering fine brush details. Removing both modules degrades performance below either single ablation, demonstrating that SKM and MSCA are orthogonal yet complementary: SKM supplies pixel-wise location priors during kernel generation, while MSCA refines cross-scale channel responses after filtering. Their insertion order can be swapped without significant metric change, verifying functional independence and providing quantitative insight into the respective drivers of performance gain.

Ablation study on convolution Kernel selection in MSCA module

The ablation results for different kernels of convolution layers are shown in Table 3. Under a 20%−30% mask ratio, the progressive convolution kernel size yields the best inpainting results. Introducing coordinate information during the progressive filtering kernel generation process directly provides spatial location information for the inference process, which enhances the ability to understand the spatial structure of the image.

Ablation study on loss function composition and weight balance

The ablation results of the loss function are presented in Table 3. Adding TV loss enhances noise reduction in the images but may result in excessive smoothing. Increasing the kernel size does not produce a monotonic PSNR gain. Instead, LPIPS deteriorates within the 20–30% mask ratio. This occurs because a larger receptive field averages the local intensity variations of ink-wash strokes, causing over-smoothed textures and perceptual drift from the original artwork. Additionally, the style loss ensures that the restored image preserves the stylistic features of the original artwork. To verify that the chosen weight ratios are balanced, we performed a short combinatorial scan. The results are summarized in Table 4. As shown in the table, the reported weights consistently achieve the highest PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS values, confirming that they lie in a stable and well-balanced region of the hyper-parameter space.

In contrast, the method we proposed combines multiple loss terms, considering both inpainting accuracy and perceptual quality, including style features and visual authenticity. This approach achieves high-quality restoration of the original artwork.

Discussion

The existing method shows unsatisfactory performance in the inpainting of traditional Chinese painting images which have a complex image structure and abstract expression. Aiming at this problem, a Twin Cascade Spatial Multi-scale Attention Filtering network is proposed. By using the spatial coding mechanism to capture the spatial relationship and structure information between pixels in the process of filtering generation, the high-fidelity image detail filling and excellent visual effect are realized.

However, it should be noted that there are still limitations and areas for further improvement. For instance, while our method has shown good performance in handling the spatial aspects, it may face challenges when dealing with extremely damaged or severely deteriorated images where a significant amount of information is missing.

Future research could explore ways to combine our spatial-based approach with other complementary techniques, such as texture synthesis or semantic understanding, to address such challenging cases more effectively.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The dataset in this study is available at https://github.com/LPDLG/TCSMAF.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pathak, D., Krahenbuhl, P., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Efros, A. A. Context encoders: Feature learning by inpainting. In Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2536–2544 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Mat: Mask-aware transformer for large hole image inpainting. In Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 10758–10768 (2022).

Dong, Q., Cao, C. & Fu, Y. Incremental transformer structure enhanced image inpainting with masking positional encoding. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 11358–11368 (2022).

Liu, H., Jiang, B., Xiao, Y. & Yang, C. Coherent semantic attention for image inpainting. In Proc. IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 4170–4179 (2019).

Zheng, H. et al. Image inpainting with cascaded modulation gan and object-aware training. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 277–296 (Springer, 2022).

Iizuka, S., Simo-Serra, E. & Ishikawa, H. Globally and locally consistent image completion. ACM Trans. Graph. 36, 1–14 (2017).

Deng, X. & Yu, Y. Ancient mural inpainting via structure information guided two-branch model. Herit. Sci. 11, 131 (2023).

Chi, L., Jiang, B. & Mu, Y. Fast Fourier convolution. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 4479–4488 (2020).

Xu, Z. et al. Hierarchical painter: Chinese landscape painting restoration with fine-grained styles. Vis. Intell. 1, 19 (2023).

Lugmayr, A., Danelljan, M., Romero, A., Timofte, R. & Van Gool, L. Repaint: Inpainting using denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 11461–11471 (2022).

Guo, Q. et al. Jpgnet: Joint predictive filtering and generative network for image inpainting. In Proc. 29th ACM International conference on multimedia, 386–394 (2021).

Sun, Z., Lei, Y. & Wu, X. Ancient paintings inpainting based on dual encoders and contextual information. Herit. Sci. 12, 266 (2024).

Zaixuan, F., Wei, T., Hai, Q. & Jinjian, Y. Implementation of grouting and salts reduction treatments of cave 85 wall paintings. In Agnew, N. (ed.) Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road, 480–487 (Getty Conservation Institute, 2010).

Wang, X. & Li, X. Application of western modern conservation principles in chinese paper relics: a case study of the restoration of the Qing dynasty couplet. J. Cult. Relics Conserv. 42, 45–52 (2023).

Tan, J. & Liu, Y. A brief discussion on the restoration and conservation techniques of color-heavy silk paintings. J. Cult. Herit. 58, 123–135 (2024).

Zhang, W. & Li, H. Exploration and reflection in paper relic restoration: a case study of the Qing dynasty scroll “immortal beneath the pines". J. Conserv. Stud. 39, 88–95 (2023).

Chen, Y. & Wang, L. Discussion on the restoration methods of the painting Hongli Jian Gu Tu. Stud. Conserv. 69, 210–221 (2024).

He, Z., Zheng, D. & Chen, X. Conservation of the Cai Zhongqi Guan Cha Shuo Tie in the Nanjing Museum collection. In Proc. 7th Annual Academic Conference of the China Association for Preservation Technology of Cultural Relics, 150–154 (Science Press, 2012).

Bertalmio, M., Sapiro, G., Caselles, V. & Ballester, C. Image inpainting. In Proc. 27th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, 417–424 (2000).

Meng, X. The value of traditional and modern techniques in the conservation and restoration of paper-based cultural relics in museum collections. Cultural Relics Identification and Appreciation 42–45 (2022).

Giakoumis, I., Nikolaidis, N. & Pitas, I. Digital image processing techniques for the detection and removal of cracks in digitized paintings. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 15, 178–188 (2006).

Barnes, C., Shechtman, E., Finkelstein, A. & Goldman, D. B. Patchmatch: A randomized correspondence algorithm for structural image editing. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 28, 24 (2009).

Yu, J. et al. Generative image inpainting with contextual attention. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5505–5514 (2018).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27 (2014).

Ko, K. & Kim, C.-S. Continuously masked transformer for image inpainting. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 13169–13178 (2023).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 6840–6851 (2020).

Nagar, S., Bala, A. & Patnaik, S. A. Adaptation of the super resolution sota for art restoration in camera capture images. In 2023 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Technologies (ICETCI), 1–6 (2023).

Lyu, Q., Zhao, N., Yang, Y., Gong, Y. & Gao, J. A diffusion probabilistic model for traditional Chinese landscape painting super-resolution. Nature (2023).

Zhu, L. et al. Leveraging diffusion knowledge for generative image compression with fractal frequency-aware band learning. In Proc. 33rd ACM International Conference on Multimedia (ACM MM), 4037–4046 (2025).

Lu, R. et al. Diffusion-based bit-depth expansion. In 2024 IEEE 26th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP), 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Mildenhall, B. et al. Burst denoising with kernel prediction networks. In Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2502–2510 (2018).

Carbajal, G., Vitoria, P., Lezama, J. & Musé, P. Blind motion deblurring with pixel-wise kernel estimation via kernel prediction networks. IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging (2023).

Guo, Q. et al. Efficientderain: Learning pixel-wise dilation filtering for high-efficiency single-image deraining. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 35, 1487–1495 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Misf: Multi-level interactive siamese filtering for high-fidelity image inpainting. In Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1869–1878 (2022).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 25 (2012).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, proceedings, part III 18, 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Lempitsky, V., Vedaldi, A. & Ulyanov, D. Deep image prior. In 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 9446–9454 (IEEE, 2018).

Johnson, J., Alahi, A. & Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution 694–711 (2016).

Suvorov, R. et al. Resolution-robust large mask inpainting with Fourier convolutions. In Proc. IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 2149–2159 (2022).

Zhou, B., Lapedriza, A., Khosla, A., Oliva, A. & Torralba, A. Places: a 10 million image database for scene recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40, 1452–1464 (2017).

Kaggle. Painter by Numbers data set. (2016). https://kaggle.com/competitions/painter-by-numbers. Accessed: 2025-09-24.

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2019).

Sonka, M., Hlavac, V. & Boyle, R. Image Processing, Analysis, and Machine Vision (2014).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Zhang, R., Isola, P., Efros, A. A., Shechtman, E. & Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 586–595 (IEEE, 2018).

Yi, Z., Tang, Q., Azizi, S., Jang, D. & Xu, Z. Contextual residual aggregation for ultra high-resolution image inpainting. In Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 7508–7517 (2020).

Deng, Y., Hui, S., Meng, R., Zhou, S. & Wang, J. Hourglass attention network for image inpainting. In European conference on computer vision, 483–501 (Springer, 2022).

Liu, W. et al. Coordfill: Efficient high-resolution image inpainting via parameterized coordinate querying. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 37, 1746–1754 (2023).

Zeng, Y., Fu, J., Chao, H. & Guo, B. Aggregated contextual transformations for high-resolution image inpainting. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 29, 3266–3280 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2021).

Liu, H., Wang, Y., Qian, B., Wang, M. & Rui, Y. Structure matters: Tackling the semantic discrepancy in diffusion models for image inpainting. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2024).

Johnson, J., Alahi, A. & Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Proc. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Part II 14, 694–711 (Springer, 2016).

Sanakoyeu, A., Kotovenko, D., Lang, S. & Ommer, B. A style-aware content loss for real-time HD style transfer. In Proc. European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 698–714 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Key Project of Scientific Research Plan of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (No. 24JS052), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62471390, No. 62406247, No. 62306237), Key Laboratory of Archaeological Exploration and Cultural Heritage Conservation Technology (Northwestern Polytechnical University, No. 2024KFT03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.H: Conceptualization, software, validation, resources, data curation, formal analysis. L.K: Preparation, methodology. C.L: Preparation, methodology. X.P: Software, Investigation, Validation. S.Q: Writing–review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration. J.P: Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Q., Kong, L., Li, C. et al. TCSMAF: twin cascade spatial multi-scale attention filtering inpainting of traditional Chinese painting. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 13 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02184-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02184-x