Abstract

Salt weathering poses a major threat to porous sandstone in cultural heritage. Iron-tartrate complexes have been proposed to modify NaCl crystallization behavior and prevent clumping. However, their efficacy in stone conservation has remained unverified. This study presents the first systematic validation of iron-tartrate complexes as environmentally friendly inhibitors for the preservation of sandstone heritage. Through a multi-method experimental approach, potassium ferricyanide (FCN), ferrous meso-tartrate (Fe(II)-mTA), and ferric meso-tartrate (Fe(III)-mTA) are shown to markedly modify NaCl crystal habit, enhance material durability, and triple salt extraction efficiency, with negligible impact on pores below 10 µm. Molecular dynamics simulations further indicate that inhibitor adsorption energy on NaCl {100} and {111} crystal surfaces followed the order of FCN > Fe(III)-mTA > Fe(II)-mTA, which is consistent with the experimental findings. This work establishes iron-tartrate complexes as an effective and sustainable strategy for protecting sandstone heritage against salt damage, with the recognition that its performance is substrate-dependent and requires further long-term validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salt crystallization in building materials is one of the most common causes of the deterioration of historic architecture1,2. As the most abundant salt on Earth, sodium chloride (NaCl) is commonly found in silicate-based cultural heritage materials, including ancient buildings, stone sculptures, and other archeological sites3. Its presence stems mainly from environmental inputs and anthropogenic impacts. Environmental NaCl is derived from multiple pathways, such as atmospheric transmission4, flood or seawater intrusion, and in-situ geochemical processes5. Anthropogenic NaCl is primarily introduced through inappropriate repairs6, including the use of salt-containing cleaning agents or reinforcing materials. Furthermore, certain sandstone lithologies contain albite (NaAlSi3O8), which dissolves and releases sodium ions under the changing hydrogeochemical disturbance, and combines with chloride ions in the external environment to form NaCl deposits7.

Research has identified the crystallization pressure generated by crystal growth on the pore walls of porous materials as a major factor in rock deterioration8,9. When the ambient relative humidity falls below the critical threshold of 76%, NaCl solutions within the pores become supersaturated and crystallize. Higher temperatures promote a greater degree of supersaturation, leading to increased crystallization pressure10. In high-porosity stones, NaCl tends to crystallize within larger internal pores, whereas in low-porosity stones, it occurs predominantly at or near the surface. For sandstone, the pore size range of 0.1–10 µm represents a high-risk zone for crystallization damage. Furthermore, pore geometry effects make smaller pores more prone to maintaining solution supersaturation11. This promotes the formation of NaCl crystals that develop elevated crystallization pressures12. Even within macroporous systems, confined crystal growth can generate substantial pressure13,14.

Under dry conditions, NaCl solutions within stone preferentially deposit at evaporation fronts, resulting in surface salt crust (efflorescence) or subcutaneous salt frost (subflorescence). Temperature and humidity fluctuations drive repeated NaCl dissolution-crystallization cycles within the pore network. The phase transitions during crystallization induce irreversible volume expansion of the rock matrix. Studies have shown that although the crystallization pressure of NaCl (~27 MPa) is lower than that of Na2SO4 (which can reach up to 70 MPa)12, the mechanical stress generated by NaCl crystallization still far exceeds the tensile strength of sandstone (~5 MPa). The presence of NaCl can lower the phase transition temperature of Na2SO4 and reduce its solubility. This synergy significantly amplifies the destructive effect of Na2SO4, which can expand in volume by up to 416% during crystallization15. Furthermore, salt weathering may also produce diseases such as granular disintegration, laminated exfoliation, sanding and honeycombing16, leading to irreversible loss of architectural details and historical value in ancient architectural relics.

Despite extensive research efforts, no rapid, effective and technically feasible solutions have yet been found to fully mitigate salt crystallization damage in architectural substrates. This challenge is particularly acute when eliminating salt sources and/or controlling microclimatic environments is generally not feasible. Poultice desalination remains one of the most traditional and widely employed salt damage mitigation methods17,18, despite its well-documented inefficiency and inconsistent performance. Recently, considerable attention has focused on inhibitors due to their “targeted regulation” properties19,20,21. These agents can alter the crystal growth process and crystallization habits by preferentially adsorbing on specific NaCl crystallographic planes, thereby hindering or delaying salt crystallization within porous stone. Sodium and potassium ferrocyanides (Na4Fe(CN)6 and K4Fe(CN)6) exhibit particularly strong adsorption properties. At ultralow concentrations (a few parts per million)22,23, they induce the transformation of NaCl crystals from cubic to dendritic structures while exhibiting minimal adhesion to porous stone surfaces24. Consequently, ferrocyanides have been extensively applied in building materials25,26,27. However, they are not easily degraded and pose strong environmental risks28. It has been noted that the process may lead to the formation of the blue discoloration (Prussian blue) in treated surface29, which is detrimental to their application.

As an environmentally benign alternative, iron-tartrate complexes have been considered as NaCl crystallization inhibitors. Structural analyses of these complexes reveal molecular interactions with specific crystallographic planes of NaCl that effectively suppress crystal growth30,31. Experimental evidence further indicates that Fe(II)-tartrate complex can elevate the supersaturation level of NaCl solutions to approximately 5.5%31. However, a critical gap remains in applying these solution-phase findings to porous stone. Their efficacy under variable environmental conditions and long-term stability are key concerns. Moreover, the performance of different iron valence states in addressing these issues is entirely unexplored.

To address this, this study provides the first evaluation of ferrous meso-tartrate (Fe(II)-mTA) and ferric meso-tartrate (Fe(III)-mTA) as sustainable inhibitors for sandstone heritage. This work is particularly relevant to conserving Chinese sandstone heritage, including Sichuan sculptures and Shanxi grottos, where salt weathering poses a persistent threat32,33. A systematic comparison with potassium ferricyanide (FCN) was conducted, focusing on their adsorption mechanisms, crystallization inhibition performance, and effects on sandstone microstructure. The investigation specifically aims to assess the potential of these iron-tartrate systems to meet key conservation challenges, including their functional stability and compatibility with stone substrates under testing conditions that simulate real-world variability. The outcomes aim to establish practical, conservation-compatible strategies for mitigating salt damage in historic sandstone.

Methods

Materials

Potassium ferrocyanide trihydrate (99%), iron(II) sulfate heptahydrate (99%), iron(III) chloride (99%), meso-tartaric acid monohydrate (90%), sodium hydroxide (96%), and NaCl (99.5%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. All chemical reagents were used without further purification. The well-established inhibitor FCN was used as a reference. The other two inhibitors, Fe(II)-mTA and Fe(III)-mTA, were synthesized following a previously reported method31.

Preparation of sandstone samples

The sandstone was a red variety sourced from Sichuan, China, with a mineral composition primarily of quartz and albite (combined content >80%). The stones were cut into 5-cm cubes, ground on all surfaces, and cleaned with deionized water. Subsequently, the samples were dried in an oven at 60 °C until constant weight was achieved. After cooling naturally to room temperature, they were randomly divided into two groups: one for a salt erosion-freeze-thaw coupling test, and the other for a salt absorption-desalination test. Three randomly selected sandstone samples were tested, with average porosity, dry density, and grain density values of 15.14%, 2.16 g cm–3, and 2.54 g cm–3, respectively.

Salt crystallization test

A 10% (w/w) NaCl solution was prepared. Various concentrations of FCN (0.01% to 0.1% w/w) were individually added to NaCl solution to monitor crystallization kinetics and crystal morphology for determining the optimal FCN concentration. For each test, 0.1 mL of the filtered solution was deposited onto a glass slide, the crystallization process and NaCl crystal formation during droplet evaporation were observed using video microscope under controlled conditions (20 °C, 45% RH). The optimal inhibitor concentration was determined based on these observations. The same experimental protocol was applied to evaluate Fe(II)-mTA and Fe(III)-mTA at concentration ranges of 0.01–0.1% and 0.05–0.5%, respectively. The pH values of NaCl solutions were adjusted to 4–5 for Fe(II)-mTA and 6.3 for Fe(III)-mTA systems to ensure optimal inhibitory performance. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure repeatability. The entire experimental procedure, including the salt crystallization test, is illustrated in Fig. 1.

a Salt crystallization test. The left image depicts the crystallization process of a 10% NaCl solution under a digital microscope with varying inhibitor concentrations. The right image displays a representative result, showing the crystalline morphology obtained with 0.05% Fe(II)-mTA inhibitor. b Salt erosion–freeze–thaw test. This panel outlines the three-step cyclic procedure (repeated 6 times). The left image shows sandstone samples immersed in a saturated NaCl solution with different inhibitors for 12-h of salt erosion. The middle image represents the subsequent 4-h freezing phase at –26 °C. The right image illustrates the final 4-h drying phase at 105 °C. c Salt absorption–desalination test. This panel contains two main processes. The left section illustrates the salt absorption phase: sandstone samples (sealed on all sides) were placed on a nano-sponge within a 10% NaCl solution, with the liquid level just covering the sponge. The image above the horizontal arrow displays the samples after salt absorption and subsequent drying at 60 °C to constant weight. The right schematic shows the desalination phase: after each desalination step, samples were air-dried for 16 h before the next desalination cycle. The process was repeated 6 times, Following the sixth desalination, the samples were dried at 60 °C to constant weight.

Salt erosion-freeze-thaw coupling (SEFTC) test

The SEFTC test was performed on sandstone specimens according to the reported method32. Saturated NaCl solution was prepared in four containers. The inhibitors FCN, Fe(II)-mTA, and Fe(III)-mTA were added to three of the containers at concentrations of 0.05%, 0.05%, and 0.1% (w/w), respectively. The fourth container (without inhibitor) served as the control. Specimens were immersed in the solutions for 12 h, and the residual solution was then wiped from their surfaces. Afterwards, the specimens were frozen at –26 °C for 4 h, followed by heating in a 105 °C oven for another 4 h. Finally, the specimens were cooled to room temperature, and the surface changes were observed. This cycle was repeated until the untreated control samples showed obvious damage, for a total of six cycles across all specimens.

The salt absorption test

The salt absorption test was carried out according to literature30. All lateral surfaces of the cleaned specimens were sealed with resin to ensure unidirectional vertical ion migration and controllable axial capillary absorption. After the resin was completely cured, the specimen mass was recorded as m1.

In-situ capillary transport simulation:

-

A nano-porous sponge was placed in a shallow-bottom container;

-

A 10% NaCl solution was continuously supplied to maintain sponge saturation;

-

Specimens were positioned on the sponge to allow bottom-to-top salt solution migration through capillary action.

After the upper surface was completely wetted, the salt was allowed to grow and precipitate within pore networks of specimens. Specimens were then transferred to a 60 °C oven and dried to constant weight (recorded as m2). The absorbed NaCl mass was calculated as (m2 − m1).

The desalination test

The desalination of salt-laden specimens was performed using inhibitor-containing poultices, following a procedure reported by our research group34. The experimental design was developed to evaluate the persistent desalination effect of a single inhibitor application. Aqueous solutions of FCN, Fe(II)-mTA, and Fe(III)-mTA were prepared at concentrations detailed in Table 1. Xuan paper pulp (XPP) was mixed into these solutions to prepare three distinct inhibitor-containing poultices, and a control poultice composed solely of XPP and deionized water.

Four sample groups were prepared: three test groups with inhibitor-treated poultices and one control group, each with five replicates. The bottom surfaces of all specimens were sealed with removable tape. Uniform poultices (2 mm thickness) were applied to the top surfaces and covered with perforated plastic film to control moisture evaporation. Specimens were transferred to a climatic chamber (20 °C, 45% RH) for 4 h. Subsequently, the plastic films and poultices were carefully removed, and the specimens were air-dried for 16 h. This 20-h process constituted one complete desalination cycle.

The experimental design used an inhibitor-treated poultice for the first cycle only. Pure water poultices were used for the subsequent five cycles. This approach offers two significant advantages: (i) it effectively assesses whether a single inhibitor treatment can provide sustained desalination for sandstone, maintaining its efficacy during subsequent pure-water cycles; (ii) it helps prevent excessive supersaturation and the consequent high crystallization pressure, thereby avoiding damage to the sandstone matrix. This persistence evaluation method has previously been applied in desalination studies on Chinese sandstones35.

To ensure comparable desalination effects, equal masses of poultice, aqueous inhibitor solution, and deionized water were used for each specimen. After each application, the poultice and any exfoliated surface particles were collected, mixed with deionized water, and analyzed through electrical conductivity measurements of leachate to quantify soluble salt content. The residual particulates were separated, dried, and assessed to determine desalination efficiency. After six desalination cycles, all specimens, including the controls, were oven-dried at 60 °C until a constant mass (recorded as md) was achieved. This moderate temperature was selected specifically to minimize the risk of thermal damage to the stone specimens during the final drying stage.

The desalination efficiency of sandstone specimens was assessed by the amount of salt precipitated in the XPP and the specimens mass loss in each treatment. The amount of precipitated salt in each XPP was determined by conductivity measurements. The mass of weathered material was quantified from particles dislodged during treatment. Desalination efficiency (w) was determined according to Eq. 1:

where (m2−md) is the total mass of salt lost after desalination, and a is the total mass of particles separated from the sample during the desalination process.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) measurements

For each specimen, five measurements were conducted along each of the three orthogonal axes (x, y, z) with transducers positioned on opposite surfaces. The corresponding directional P-wave velocities were calculated according to Formula (2):

where d is the transducer spacing distance (m), and t is the ultrasonic wave propagation time (s). The mean UPV per specimen was derived from the averaged measurements.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

All optimization work was performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)36. The adsorption energy (Eads) was calculated via the Kohn-Sham density functional theory (DFT)37,38 using projector-augmented wave (PAW) potentials39, with a cut off energy of 400 eV and the exchange-correlation function of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE)40. All calculations were performed at 27 °C without consideration of solvation effects. The {111} and {100} surfaces of NaCl were modeled using a supercell that accommodates the entire system, avoiding periodic interactions. In addition, given the larger lattice constants of NaCl {100} and NaCl {111}, a 1 × 1 × 1 gamma-centered k-point sampling grid was sufficient. The convergence criteria for electronic SCF iteration energy and ion step iteration force were 1.0 × 10−6 and 0.02 eV, respectively. The Eads was calculated by the following formula:

where Ecomp is the total energy of NaCl crystal surface-adsorbate molecule complex, Eslab is the surface energy of NaCl {100} crystal face, and Ea is the total energy of the FCN, Fe(II)-mTA, and Fe(III)-mTA compounds. Furthermore, the molecular structure of Fe(II)-mTA was established based on literature31, while the Fe(III)-mTA was constructed according to literature28.

Instruments

The crystallization behavior and morphology of NaCl, along with the surface roughness of sandstone specimens, were observed and recorded using a VHX-2000 video microscope (VM).

Contact angles of NaCl solutions (with or without inhibitors) on glass substrates were measured with a LAUDA Scientific Surface Analyser (LSA 100).

Microstructural analysis was performed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-IT800, JEOL Ltd., Japan).

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained on a Rigaku D/Max-2500 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å) at 40 kV and 15 mA, with a 2θ range of 10–80° and a step size of 5° min–1.

The specimen integrity before and after desalination treatment was evaluated through CTS-65 non-metallic ultrasonic testing instrument.

Colorimetric changes in sandstone specimens were recorded using a portable integrating sphere spectrophotometer (X-rite Ci64, USA).

Pore size distributions in specimens (measured 1 cm below the upper surface) were conducted by mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP, Micromeritics AutoPore V 9600), covering pore diameters of 0.005−350 μm.

Chloride ion concentrations at varying depths were quantified using ion chromatography (Dionex Aquion RFIC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Results

Concentration-dependent crystal morphology modifications in salt crystallization test

FCN. Starting from a concentration of 0.01%, FCN showed a slight inhibitory effect on crystallization of NaCl, but this effect was not obvious. At 0.02%, dendritic rather than cubic crystals precipitate when the solution begins to crystallize. As the FCN concentration increased, the dendritic crystals of NaCl became increasingly dense, suggesting progressive coverage of NaCl surface by FCN molecules. This dendritic growth implies that FCN preferentially adsorbs to high-energy crystal faces, altering the equilibrium morphology41. When FCN concentration exceeded 0.07%, the solution exhibited intensified boiling behavior. Based on NaCl crystallization time and crystal morphology, optimal FCN concentration was determined to be 0.05% (Fig. 2a).

a Crystalline morphology of a 10% NaCl solution containing 0.05% FCN under a digital microscope. b Crystalline morphology of a 10% NaCl solution containing 0.05% Fe(II)-mTA under a digital microscope. c Crystalline morphology of a 10% NaCl solution containing 0.1% Fe(III)-mTA under a digital microscope. d A magnified view of the area marked by the orange square in (c), which clearly reveals the step-like growth pattern on NaCl crystals.

Fe(II)-mTA and Fe(III)-mTA. Starting from 0.03%, Fe(II)-mTA was found to exhibit inhibitory effects on NaCl crystallization, inducing dendritic crystal morphologies similar to those observed with FCN (Fig. 2b). Quantitative analysis identified 0.05% as its optimal inhibitory concentration. In contrast, Fe(III)-mTA demonstrated only marginal inhibition below 0.05%, with slight enhancement at 0.05% and substantial inhibition at 0.1% (Fig. 2c). This concentration-dependent behavior established 0.1% as the optimal concentration for Fe(III)-mTA, consistent with the positive concentration-efficacy correlation. The suitable pH and optimal concentrations of three inhibitors in 10% NaCl solutions were presented in Table 1.

Contact angle analysis

Contact angles (CA) of NaCl droplets on glass substrates with or without inhibitors listed in Table 1. The addition of inhibitors influences the CA of NaCl droplets, consequently affecting their wetting behavior on glass substrates. CA measurements revealed consistent increases for both 10% and saturated NaCl solutions:

-

(i)

FCN elevated CA by 6.0° (from 25.7° to 31.7°) for the 10% solution and by 2.7° (from 35.8° to 38.5°) for the saturated solution;

-

(ii)

Fe(II)-mTA produced increases of 5.0° (from 25.7° to 30.7°) and 8.5° (from 35.8° to 44.3°), respectively;

-

(iii)

Fe(III)-mTA resulted in increases of 7.8° (from 25.7° to 33.5°) and 7.1° (from 35.8° to 42.9°).

The maximum observed change of 8.5° represents a minor modification. Consequently, the inhibitors exhibited negligible effects on both surface tension and droplet wetting behavior.

XRD and SEM analyses on the NaCl crystals in salt crystallization test

Figure 3a shows the XRD patterns of NaCl containing 0.05% FCN inhibitor, where the intensity ratios of (200), (111), (220), and (420) Bragg peaks varied significantly. The enhanced intensity of the dodecahedral {110} faces, along with a moderate increase in the (111), (222), and (420) peaks, suggests the presence of octahedral {111} and tetrahedral {210} facets42. The addition of FCN increased the supersaturation level of NaCl solution, [Fe(CN)6]4− ions in solution effectively inhibited Na+ migration toward developing NaCl crystal clusters through specific adsorption mechanisms42,43,44, resulting in spiral dislocations in NaCl crystallization (Fig. 4a). As supersaturation increased, the growing NaCl crystal surface was continuously covered by inhibitor molecules, and the growth habit of the crystals shifted from cubes to dendrites. (Fig. 4b)45. XRD and SEM analyses indicated morphological changes consistent with the literature42.

a Spiral dislocation observed during the crystallization of NaCl with 0.05% FCN. b Dendritic crystal growth of NaCl in the presence of 0.05% FCN. c Spiral dislocation morphology on a NaCl crystal formed with 0.05% Fe(II)-mTA. d Deformed octahedral morphology of NaCl crystal grown with 0.05% Fe(II)-mTA. e Distorted polyhedral morphology of NaCl crystal obtained with 0.1% Fe(III)-mTA. f Dislocation on the {100} crystal face of NaCl grown with 0.1% Fe(III)-mTA.

The XRD patterns of NaCl containing 0.05% Fe (II)-mTA showed an obvious decrease in the peak intensity of the (200) face (Fig. 3b), while the peak intensities of (110), (222) and (210) faces increased. Due to the inhibition of NaCl {100} face, spiral dislocation morphology was observed on the {110} crystal face in SEM (Fig. 4c), along with deformed octahedral structures formed by the growth of the {111} face (Fig. 4d). These observations are consistent with the XRD results. Figure 3c shows that the XRD pattern of NaCl containing 0.1% Fe(III)-mTA was similar to those observed with Fe(II)-mTA, indicating inhibited growth of the {100} cubic facet, and enhanced growth of the dodecahedral {110} and octahedral {111} facets. These observations are consistent with the SEM results (Fig. 4e). Figure 4f displays the dislocation morphology of NaCl {100} crystal surfaces, showing characteristic surface step growth blockage17.

The SEFTC test in sandstone specimens

Six replicate SEFTC tests were performed on sandstone specimens to evaluate their deterioration resistance and phase transformation behavior in inhibitor-containing brine systems (Fig. 5). After the third cycle, the untreated specimens (without inhibitor) exhibited extensive surface pulverization, while the FCN-treated specimens developed numerous non-adherent dendritic NaCl crystals. Both Fe(II)-mTA and Fe(III)-mTA treated specimens showed fewer dendrites than FCN-treated ones, with Fe(II)-mTA specimens having slightly fewer than those treated with Fe(III)-mTA. Following five cycles, the untreated specimens displayed severe weathering with edge/corner loss. In contrast, the FCN-treated specimens maintained dendritic precipitation on their surfaces without visible chalking. Specimens treated with Fe(II)-mTA displayed noticeable surface chalking, whereas those treated with Fe(III)-mTA showed only slight chalking. After six cycles, the untreated specimens retained only their central core, while the FCN-treated specimens demonstrated minor surface delamination with peripheral detachment. The Fe(II)-mTA treated specimens maintained structural integrity without visible detachment, but surface microfractures developed due to crystallization-induced stress within pore networks. The Fe(III)-mTA treated specimens exhibited obvious powdery detachment on surfaces and edges. Overall, all inhibitor-treated specimens showed significantly less weathering than the untreated, confirming their effectiveness in improving the sandstone’s resistance to salt-induced deterioration.

a Deterioration of a sandstone specimen after exposure to the 3rd, 5th, and 6th cycles in a saturated NaCl solution. b Deterioration of a sandstone specimen after exposure to the 3rd, 5th, and 6th cycles in a saturated NaCl solution containing 0.05% FCN. c Deterioration of a sandstone specimen after exposure to the 3rd, 5th, and 6th cycles in a saturated NaCl solution containing 0.05% Fe(II)-mTA. d Deterioration of a sandstone specimen after exposure to the 3rd, 5th, and 6th cycles in a saturated NaCl solution containing 0.1% Fe(III)-mTA.

Desalination effectiveness

Conductivity tests showed that in the first cycle, the desalination efficiency of FCN-XPP and Fe(II)-mTA-XPP was approximately three times higher than that of the control (Fig. 6a). In contrast, Fe(III)-mTA-XPP showed a smaller improvement, yielding only twice the efficiency of the control. The actual desalination efficiencies of the four specimen groups were 52.4% (0.05% FCN), 48.6% (0.05% Fe(II)-mTA), 43.5% (0.1% Fe(III)-mTA) and 37.3% (control).

a Point-line diagram of conductivity values versus the number of desalination cycles for different poultices. The red line indicates desalination with FCN-XPP, the green line with Fe(II)-mTA-XPP, the blue line with Fe(III)-mTA-XPP, and the black line represents the control group (XPP without an inhibitor). b Point-line diagram of specimen mass loss versus the number of desalination cycles for different poultices. The red line corresponds to FCN-XPP, the green line to Fe(II)-mTA-XPP, the blue line to Fe(III)-mTA-XPP, and the black line to the control (XPP without an inhibitor).

Figure 6b presents the quantitative mass loss of specimens after each desalination treatment. Compared to the control group, specimens treated with FCN-XPP or Fe(II)-mTA-XPP exhibited lower mass loss. Specifically, the Fe(II)-mTA-XPP treated specimens showed slightly lower mass loss, while those treated with Fe(III)-mTA-XPP demonstrated only marginally higher mass loss than the control.

MD simulation

Figure 7 showed the MD simulation results of FCN, Fe(II)-mTA, and Fe(III)-mTA on NaCl {100} and {111} crystal planes. Corresponding adsorption energies are detailed in Table 2. The adsorption energy (Eads) values for all three inhibitors on both crystal faces were negative, indicating exothermic adsorption. More negative Eads values correspond to greater energy release and stronger adsorption stability. The Eads on both crystal planes followed the same order: FCN > Fe(III)-mTA > Fe(II)-mTA, with consistently higher Eads on the {111} plane than the {100} plane. The {111} surface exhibits a dense arrangement of alternating sodium and chloride ions with numerous kinks and steps, resulting in higher inhibitor Eads compared to the {100} surface. This energy hierarchy aligns with the superior inhibitory efficacy of FCN at lower concentrations. Notably, the simulated Eads values and desalination efficiencies disagree for the Fe(II)-mTA and Fe(III)-mTA inhibitors. Fe(III)-mTA exhibited a more negative Eads, but Fe(II)-mTA demonstrated a higher desalination efficiency (48.6% vs. 43.5%). This suggests that inhibitor efficacy in a complex porous medium depends on factors beyond intrinsic adsorption strength.

a Binding poses of inhibitors on the {100} surface. From left to right: FCN, Fe(II)-mTA, and Fe(III)-mTA. Atomic color code: N (blue), Na (purple), Cl (green), C (gray), Fe (yellow), O (red), H (pink). b Binding poses of inhibitors on the {111} surface. From left to right: FCN, Fe(II)-mTA, and Fe(III)-mTA. Atomic color scheme is identical to that in panel a.

Microscopic morphology of desalinated sandstones

SEM images of the desalinated specimens (Fig. 8) revealed that the FCN-XPP treated specimen exhibited a considerable number of funnel-shaped NaCl skeletal crystals and surface dendrites (Fig. 8b). The surface of the Fe(II)-mTA-XPP treated specimen displayed many funnel-shaped crystalline particles (Fig. 8c), flaky crystals (Fig. 8d), and dendritic NaCl structures (Fig. 8e). The adsorption increases the supersaturation of NaCl solution within the pores, facilitating ionic migration to the sandstone surface, where NaCl forms flaky and loose dendritic structures rather than dense cubic crystals (Fig. 8d, e). The Fe(III)-mTA-XPP treated specimen showed a polymorphic mixture of cubic, octahedral, and dodecahedral NaCl crystals on the surface (Fig. 8f), with crystal dislocations were also observed within its pores systems (Fig. 8g, h). These morphological observations further confirm that the three inhibitors significantly modified NaCl crystallization patterns and effectively suppressed crystalline deposition within the sandstone matrix.

a Control specimen without inhibitor. NaCl crystal morphology on the sample surface. b FCN-XPP treated specimen. Deformed NaCl crystals on the surface. c–e Fe(II)-mTA-XPP treated specimen. c Abundant deformed NaCl crystals on the surface. d Deformed NaCl crystals within a sample pore. e Dislocation morphology of NaCl crystals precipitated in a pore. f–h Fe(III)-mTA-XPP treated specimen. f Numerous deformed NaCl crystals on the surface. g Dislocation morphology of NaCl crystals within a pore. h Enlarged view of the area marked by the red circle in (g).

The macroscopic observations and roughness measurements of the central area (1 cm below the upper surface) of desalinated specimens are illustrated in Fig. 9 and summarized in Table 3. The left panel of Fig. 9 shows the surface profile, while the right panel shows the cross-sectional roughness. In the right panel, the red curve represents the arithmetic mean roughness (Ra), defined as the arithmetic average of absolute value of the distance between the measured surface profile and the reference line within the sampling length. The blue curve shows the maximum height (Ry), representing the vertical distance between the highest peak and lowest valley in the profile. Table 3 lists Rz, the ten-point average height of microscopic surface roughness. As expected, dissolution during desalination and subsequent recrystallization during drying caused some roughening of both specimen surface and near-surface layer.

Each pair of (a–d) presents, from left to right, the surface profile and the corresponding cross-sectional roughness profile from the central region of the specimen. The central cross-section is shaded yellow. The red curve shows the arithmetic average roughness (Ra), and the blue curve shows the maximum height (Ry). a) Control specimen. b FCN-treated specimen. c Fe(II)-mTA-treated specimen. d Fe(III)-mTA-treated specimen.

Macroscopic observations and profile measurements both indicate increased surface roughness in inhibitor-treated specimens after desalination, Fe(III)-mTA-treated specimens showing the smallest increase. The increase in roughness likely results from inhibitor-facilitated evaporation of saline solution within pore networks. The comparatively modest roughness increase in Fe(III)-mTA-treated specimens may correlate with their relatively lower desalination efficiency. Notably, the Rz values follow trends similar to those observed for Ra.

Colorimetric variation and UPV of desalinated sandstones

According to the principles of cultural heritage conservation, the protection and restoration of cultural heritage should not change its original appearance. Therefore, the surface color of the desalinated specimens was measured 3 months after desalination. The surface colorimetric variation (ΔE) of each specimen was the average of the five measurements listed in Table 3. Compared to the control specimen, all inhibitor-treated specimens showed smaller ΔE values after desalination, with ΔE less than 1.5, which is imperceptible to the naked eye46.

The UPV values of the desalinated specimens are shown in Table 3. The strength variation of specimens before and after desalination was minimal, likely due to the limited salt absorption cycles (only one cycle performed). In the vertical direction, the control group demonstrated poor desalination efficiency. This was likely due to localized stresses generated by randomly distributed salt crystallization within the pores, which reduced UPV values. Compared to controls, both FCN- and Fe(II)-mTA-treated specimens displayed higher UPV values, suggesting enhanced NaCl transport from pore networks to specimen surfaces. Conversely, the Fe(III)-mTA-treated group exhibited a significantly lower UPV value (4080 m s⁻¹) than the control group (4630 m s⁻¹). The reduction is likely due to the relatively larger molecular size of Fe(III)-mTA. This size causes pore blockage during migration, hinding the outward transport of salt ions and water molecules. Consequently, salts are retained within the pores. The subsequent recrystallization of these retained salts generates crystallization pressure. Ultimately, the combined effects of pore blockage and crystallization stress can induce microcracks or exacerbate pre-existing damage. Thus, the observed UPV reduction may be attributed to the following factors:

-

(i)

wave attenuation due to microcracks around residual salt crystals;

-

(ii)

partial pore obstruction caused by crystalline deposits25.

The consistent vertical-to-horizontal UPV ratio (>1) suggests anisotropic pore connectivity, likely resulting from orientation-dependent salt migration during desalination treatment.

Porosity and pore size distribution of desalinated sandstones

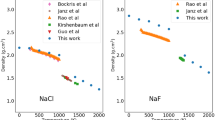

The pore size distribution and variation of desalinated specimens with and without inhibitors determined by MIP are shown in Fig. 10. The cumulative intrusion curves indicate that pore volume changes in specimens with or without modifiers show little difference for pore sizes below 10 µm. Compared to the control specimen, the FCN-desalted specimen exhibits a notable pore volume increase in both the 1–10 µm and >100 µm ranges. In contrast, the Fe(II)-mTA-desalted specimen shows a slight pore volume increase in the 10–100 µm range, while the Fe(III)-mTA-treated specimen demonstrates higher pore volumes above 10 µm. In addition, FCN has minimal effect on micropores, whereas the Fe(II)-mTA desalted specimens show the lowest porosity.

a Pore size distribution. The black curve represents the control specimen, the blue curve the FCN-treated specimen, the red curve the Fe(II)-mTA-treated specimen, and the green curve the Fe(III)-mTA-treated specimen. b Pore volume percentage across different pore radius ranges. The gray bars represent the control specimen, the blue bars the FCN-treated specimen, the orange bars the Fe(II)-mTA-treated specimen, and the green bars the Fe(III)-mTA-treated specimen.

Chloride ion concentration of desalinated sandstones

Chloride ion concentrations were measured at vertical depths of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 cm in the desalinated specimens (Table 4). The results indicated that all inhibitor-treated specimens exhibited higher surface chloride ion concentrations than the control. The FCN-treated specimen had the highest surface chloride ion accumulation, followed by the two tartrate-based inhibitors, whereas the control group had the lowest. As depth increased, the chloride ion concentration gradually decreased, with the steepest gradient observed in the FCN-treated specimen, followed by the Fe(III)-mTA and Fe(II)-mTA. These results suggest that the addition of the inhibitor promotes the evaporation and outward migration of NaCl solution within the sandstone pores, thereby enhancing surface crystallization. The variation in chloride ion concentration gradients further implies that FCN facilitates the highest salt evaporation rate. The higher salt content in the Fe(III)-mTA-treated specimens correlates with their lower desalination efficiency compared with Fe(II)-mTA-treated specimens. Furthermore, the elevated chloride ion concentrations observed at 4 cm depth across all specimens result from slower salt migration rates due to increased vertical distance from the sandstone surface.

Discussion

This study investigates the regulatory effects of two tartrates, 0.05% Fe(II)-mTA and 0.1% Fe(III)-mTA, on sodium chloride crystallization behavior and their effectiveness in the desalination treatment of saline sandstone.

VM and SEM results demonstrated that 0.05% FCN, 0.05% Fe(II)-mTA, and 0.1% Fe(III)-mTA significantly altered NaCl crystallization patterns, inducing crystal transformation of NaCl crystals from thermodynamically stable {100} facets to higher-index {110} and {111} crystallographic planes. In addition, the CA and SEFTC tests showed that the three inhibitors did not affect the wetting properties of the saline solution, while enhancing the salt-resistance durability of sandstone.

MD simulations revealed distinct adsorption energies for the three inhibitors on NaCl {100} and {111} crystallographic planes. On both crystal planes, the adsorption energy followed the order of FCN > Fe(III)-mTA > Fe(II)-mTA. This trend directly correlates with the efficiency of crystal habit modification observed via SEM and XRD. The octahedral [Fe(CN)6]4− structure of FCN fits well with the NaCl {111} surface geometry and electrostatically attracts Na+ ions. In contrast, Fe(II)-mTA binds to the {111} plane through lattice matching47,48. Fe(III)-mTA exhibits higher adsorption energy than Fe(II)-mTA, likely due to differences in their structural configurations29. The preferential adsorption retards growth of specific crystallographic planes, which disrupts natural crystal growth kinetics and promotes the emergence of unstable higher-index facets. This process ultimately induces the formation of less cohesive, dendritic crystal morphologies, as confirmed by SEM analysis. However, adsorption energy alone cannot fully explain crystal growth rates. These rates are also influenced by the relative growth speeds of different crystal faces and the supersaturation degree of solution.

The desalination efficiency followed the order of FCN > Fe(II)-mTA > Fe(III)-mTA > control. The inhibitor treatments enhanced salt migration rates in sandstone. This enhancement could be attributed to two factors: (i) reduced interfacial binding energy between NaCl crystals and sandstone pores due to crystal surface modification, and (ii) the inhibition of salt recrystallization via steric hindrance effect of adsorbed inhibitor molecules. The desalination efficiency of Fe(II)-mTA-XPP was higher than that of Fe(III)-mTA-XPP, an order inconsistent with the adsorption energy trend obtained from molecular dynamics simulations. This inconsistency may arise from several key factors. First, the overall desalination efficiency depends not only on crystallization inhibition, but also on the transport of salt ions within sandstone pores. Second, Fe(III)-mTA complexes possess a larger molecular volume than Fe(II)-mTA, which likely hinders their diffusion through the confined pore network of sandstone. Furthermore, differential interactions of two inhibitor complexes with the sandstone matrix (e.g., through hydrogen bonding or van der Waals forces) may affect their distribution and retention within the pores. These could ultimately influence their long-term efficacy over multiple desalination cycles.

Morphological analysis of desalinated sandstone showed that the inhibitor promotes the formation of dendritic precipitates. This morphology drives the evaporation front of NaCl solution toward the sandstone surface, thereby accelerating saline solution evaporation in the pore network. The Fe(II)-mTA-XPP treated sandstone had a higher UPV value, likely due to Fe(II)-mTA accelerating the pore NaCl migration. In contrast, the Fe(III)-mTA-XPP treated sandstone had a lower UPV value. The larger molecular size of Fe(III)-mTA caused pore blockage, while residual salt crystals induced crystallization stress and resultant pore damage. The change in the chloride ion concentration gradient further confirmed higher salt content in the Fe(III)-mTA-XPP treated sandstone, directly linking to its lower efficiency. In addition, MIP analysis of the desalinated sandstone further revealed that inhibitors had minimal influence on porosity changes, particularly with negligible effects on pores with diameters below 10 µm.

However, this research also has several limitations. First, the desalination efficiency depends strongly on the substrate lithology. The inherent variability of sandstones complicates the translation of laboratory results to broad real-world practice. Laboratory conditions cannot fully replicate the complex on-site environment. Second, the inhibitor functions by modifying the crystallization process. Its effectiveness is concentration-dependent, and excessively high concentrations can diminish its efficacy. Excessive supersaturation can have the opposite effect, so the concentration of the inhibitor must be kept within proper limits. Third, there is also a lack of long-term durability data. The potential side effects from repeated treatments have not been fully assessed. Therefore, comprehensive testing on authentic heritage materials is recommended before practical application. Future work should focus on long-term field evaluations and compatibility assessments across diverse materials. These steps are critical for advancing tartrate-based strategies into real-world conservation applications.

In summary, this study confirms that Fe(II)-mTA and Fe(III)-mTA can effectively inhibit NaCl crystallization in sandstone and improve desalination efficiency. Their efficacy originates from a multi-scale synergistic mechanism involving specific molecular adsorption, transformation of crystal habits into less destructive dendritic morphologies, and promotion of salt transport. The sandstone samples used in this study are characterized by high quartz content and contain certain amounts of feldspar and cementing minerals. Their lithology is similar to that of many famous Chinese grotto heritage sites primarily composed of high-quartz sandstone, such as the Yungang Grottoes, Dazu Rock Carvings, and Longmen Grottoes32,33. Consequently, the desalination method proposed in this study is primarily applicable to siliciclastic stone heritage objects with similar lithology, offering a new potential approach for mitigating salt damage in high-quartz sandstone.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Lubelli, B., Nijland, T. G., Hees, R. P. J. V. & Hacquebord, A. Effect of mixed in crystallization inhibitor on resistance of lime–cement mortar against NaCl crystallization. Constr. Build. Mater. 24, 2466–2472 (2010).

Charola, A. E. Salts in the deterioration of porous materials: an overview. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 39, 327–343 (2000).

Qazi, M. J. et al. Influence of surfactants on sodium chloride crystallization in confinement. Langmuir 33, 4260–4268 (2017).

Flatt, R. J. et al. Predicting salt damage in practice: a theoretical insight into laboratory tests. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2, 108–118 (2017).

Warscheid, T. & Braams, J. Biodeterioration of stone: a review. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 46, 343–368 (2000).

Lindqvist, J. E. Rilem TC 203-RHM: repair mortars for historic masonry. Testing of hardened mortars, a process of questioning and interpreting. Mater. Struct. 42, 853–865 (2009).

Goudie, A. S., Viles, H. A. & Parker, A. G. Monitoring of rapid salt weathering in the central Namib Desert using limestone blocks. J. Arid. Environ. 37, 581–598 (1997).

Carretero, M. I., Bernabé, J. M. & Galán, E. Application of sepiolite-cellulose pastes for the removal of salts from building stones. Appl. Clay Sci. 33, 43–51 (2006).

Benavente, D., Cura, M. A. G. D., Fort, R. & Ordóñez, S. Durability estimation of porous building stones from pore structure and strength. Eng. Geol. 74, 113–127 (2004).

Rodriguez-Navarro, C. & Doehne, E. Salt weathering: influence of evaporation rate, supersaturation and crystallization pattern. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 24, 191–209 (1999).

Putnis, A., Prieto, M. & Fernandez-Diaz, L. Fluid supersaturation and crystallization in porous media. Geol. Mag. 132, 1–13 (1995).

Benavente, D. et al. Role of pore structure in salt crystallization in unsaturated porous stone. J. Cryst. Growth 260, 532–544 (2004).

Scherer, G. W. Stress from crystallization of salt. Cem. Concr. Res. 34, 1613–1624 (2004).

Scherer, G. W. Crystallization in pores. Cem. Concr. Res. 29, 1347–1358 (1999).

Ren, K. et al. Salt weathering mechanism and climate response in Niujiaozhai Grottoes, Renshou, Sichuan. Geol. Rev. 69, 1368–1386 (2023).

Mustoe, G. E. Origin of honeycomb weathering. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 93, 108–115 (1982).

Randazzo, L., Montana, G., Castiglia, A. & Russa, M. F. L. Salt extraction from lime-based mortars: an experimental study using different poultice formulations. Constr. Build. Mater. 255, 119391 (2020).

Husillos-Rodríguez, N. et al. Sacrificial mortars for surface desalination. Constr. Build. Mater. 173, 452–460 (2018).

Al-Jibbouri, S. & Ulrich, J. The growth and dissolution of sodium chloride in a fluidized bed crystallizer. J. Cryst. Growth 234, 237–246 (2002).

Bode, A. A. C. et al. Growth inhibition of sodium chloride crystals by anticaking agents: in situ observation of step pinning. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 5889–5896 (2012).

Granneman, S. J. C., Lubelli, B. & van Hees, R. P. J. Mitigating salt damage in building materials by the use of crystallization modifiers—a review and outlook. J. Cult. Herit. 40, 183–194 (2019).

Bracciale, M. P. et al. Molecular crystallization inhibitors for salt damage control in porous materials: an overview. Molecules 25, 1873 (2020).

Glasner, A. & Zidon, M. The crystallization of NaCl in the presence of [Fe(CN)6]4− ions. J. Cryst. Growth 21, 294–304 (1974).

Granneman, S. J. C., Lubelli, B. & Hees, R. P. J. V. Effect of mixed in crystallization modifiers on the resistance of lime mortar against NaCl and Na2SO4 crystallization. Constr. Build. Mater. 194, 62–70 (2019).

Ergenç, D., Feijoo, J., Fort, R. & Buergo, M. A. D. Effects of potassium ferrocyanide used for desalination on lime composite performances in different curing regimes. Constr. Build. Mater. 259, 120409 (2020).

Selwitz, C. & Doehne, E. The evaluation of crystallization modifiers for controlling salt damage to limestone. J. Cult. Herit. 3, 205–216 (2002).

Rivas, T. et al. Crystallization modifiers applied in granite desalination: the role of the stone pore structure. Constr. Build. Mater. 24, 766–776 (2010).

Bode, A. A. C. et al. Structure and activity of the anticaking agent iron(III) meso-tartrate. Dalton. Trans. 15, 10.1039 (2016).

Lubelli, B., Bouvrie, E. D., Nijland, T. G. & Kamat, A. Plasters with mixed-in crystallization inhibitors: results of a 4-year monitoring of on-site application. J. Cult. Herit. 59, 10–22 (2023).

Townsend, E. R. et al. Creeping: an efficient way to determine the anticaking ability of additives for sodium chloride. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 18, 6176–6183 (2016).

Tian, L. et al. Ferrous tartrate recognition of sodium chloride {111} and its effect on crystal growth. Crys. Res. Technol. 51, 610–616 (2016).

Liu, S. et al. Differences in the failure process of grottoes sandstone in southern and northern China determined by microstructure. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 191 (2025).

Sun, B. et al. Experimental study on the effects of hydrochemistry and periodic changes in temperature and humidity on sandstone weathering in the Longshan Grottoes. Herit. Sci. 11, 173 (2023).

Chen, D. M., Yuan, K. & Zhan, X. M. Morphology transformation of Na2SO4 from prism into dendrite enhanced desalination efficiency in sandstone by biodegradable polycarboxylate modifiers. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134513 (2024).

Liu, R. Z., Zhang, B. J. & Mao, L. H. Effect of potassium ferrocyanide on sodium chloride crystallization. J. Jinan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Med. Ed.) 36, 448–452 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blijlevens, M. A. R. et al. Effect of the anticaking agent FeCN on the creeping properties of alkali halide crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 22, 6575–6581 (2022).

Rodriguez-Navarro, C., Linares-Fernandez, L., Doehne, E. & Sebastian, E. Effects of ferrocyanide ions on NaCl crystallization in porous stone. J. Cryst. Growth 243, 503–516 (2002).

Bode, A. A. C. et al. Anticaking activity of ferrocyanide on sodium chloride explained by charge mismatch. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 1919–1924 (2012).

Twu, Y. J., Conover, C. W. S., Yang, Y. A. & Bloomfield, L. A. Alkali-halide cluster ions produced by laser vaporization of solids. Phys. Rev. B 42, 5306–5316 (1990).

Sunagawa, I. Characteristics of crystal growth in nature as seen from the morphology of mineral crystals. Bull. Minéral. 104, 81–87 (1981).

Rodrigues, D. & Grossi, A. Indicators and ratings for the compatibility assessment of conservation actions. J. Cult. Herit. 8, 32–43 (2007).

Mizuta, T., Wang, J. & Miyoshi, K. Molecular structures of Fe(II) complexes with mono- and di-protonated ethylenediamine-N, N, N′, N′-tetraacetate (Hedta and H2edta), as determined by X-ray crystal analyses. Inorg. Chim. Acta 230, 119–125 (1995).

Yan, J., Wang, X. L. & Shao, X. The research and the progress of the anticaking technology for salt. J. Salt Chem. Ind. 40, 43–46 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U24A20506), the project of Key Research and Development Project of Shanxi Province (No. 202202130501018), and the project of Gansu Province Science and Technology Program (No. 25JRRE026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chen was responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study. She was also involved in the data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the results. Yuan was responsible for the data visualization. Jiao was responsible for the writing and visualization. Bai and Wu were responsible for the technical aspects of the research. Li was responsible for the investigation. Zhang served as the project supervisor and mentor for the team, providing guidance and support throughout the research process to ensure that the study was conducted ethically and to a high standard.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Yuan, K., Jiao, M. et al. Remedy for NaCl-induced sandstone weathering via crystallization inhibition by environmentally friendly iron tartrate. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 653 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02243-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02243-3