Abstract

Few-shot point cloud semantic segmentation (FS-PCSS) is crucial for architectural heritage digitization, as it segments unseen categories with minimal annotations. However, existing methods focus on target features while neglecting background modeling, compromising segmentation performance through artifacts and diminished feature clarity in non-target regions. To address these issues, we propose LUBK-Net, a novel framework that strengthens background feature alignment to mitigate the feature deviation caused by the domain gap. Specifically, a Background Attention Module (BAM) learns a universal background prototype using an adaptive background loss, while removing irrelevant features to suppress background noise. In addition, a Prototype Contrastive Learning (PCL) further enhances foreground-background discriminability. Experiments on the Self-built Ancient Architecture and the publicly accessible Architectural Cultural Heritage datasets demonstrate that our method outperforms state-of-the-art approaches, offering new insights for heritage conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Point clouds have emerged as an indispensable resource due to their ability to capture three-dimensional structures and intricate details accurately. As a core technology in the digital preservation of cultural heritage, point cloud semantic segmentation enables the accurate identification of building components, providing crucial data support for the monitoring, restoration, and inheritance of cultural heritage. However, their inherent disorder and lack of organized structure present significant challenges for semantic segmentation, especially when annotated data is limited. Traditional point cloud semantic segmentation (PCS) methods based on the supervised learning paradigm have achieved remarkable success1,2,3,4,5,6 and been applied to the field of architectural heritage protection7,8,9,10,11. PCS methods are generally categorized into three groups: projection-based methods12,13, voxel-based approaches14,15, and point-based approaches, which aim to balance efficiency and accuracy, leading to numerous studies. Point-wise MLP approaches typically utilize shared MLP layers as their fundamental blocks. A seminal approach, PointNet16, addresses the inherent unordered nature of point clouds by employing symmetric functions and using MLPs to extract features from individual points. Max Pooling is then applied to derive global features across multiple dimensions. Several convolutional networks17,18,19,20 have demonstrated excellent performance in processing point clouds by modeling and extracting features from local neighborhoods—graph-based convolutional methods leverage point clouds’ topological structure and connectivity for feature extraction. For example, DGCNN5 creates edge features to capture interactions between points and their neighbors. Pierdicca15 introduced a network to enhance the processing of the ArCH dataset21 by incorporating essential features such as normal vectors and color information. Despite the success of these methods, they heavily rely on annotated data and face challenges in adapting to diverse architectural styles and building types from various historical periods. Segmenting novel categories in architectural heritage is challenging due to scarce samples and insufficient labeled data. Nevertheless, they still face two non-negligible challenges in the field of point cloud semantic segmentation (PCS) for architectural cultural heritage:

-

(1)

High Dependency on Samples and Annotations: Architectural Cultural Heritage, being unique historical structures, typically provides scarce sample data, making it challenging to assemble extensive annotated datasets. Conventional supervised methods rely on abundant annotations to train models effectively, restricting their segmentation performance under limited data conditions. Moreover, with few annotated samples, these models struggle to learn generalized features and are prone to overfitting, especially on unseen categories.

-

(2)

Weak Adaptability to Different Architectural Styles: Architectural components in cultural heritage buildings often exhibit significant stylistic variations. For instance, as illustrated in Fig. 1, elements such as beams, roofs, and doors vary markedly in shape and ornamental details across different styles. Supervised learning methods usually require many samples for each style to distinguish these differences effectively, making it challenging to adapt to the complex stylistic diversity encountered in segmentation tasks under minor sample conditions.

To address these challenges, few-shot learning has become a solution with great promise. By leveraging only 1–5 annotated samples per category, it extracts the core features of the target class through optimized prototype learning, thereby deriving more generalized feature representations from limited data. Furthermore, it also captures subtle differences and shared traits among categories, handling fine-grained distinctions between similar building elements across styles. This allows accurate inference and segmentation, even for novel classes.

Currently, few-shot point cloud semantic segmentation (FS-PCSS) predominantly follows the paradigm of prototype learning22 and employs a two-stage training strategy. Zhao23 presented the foundational work and introduced an attention-enhanced, multi-prototype propagation segmentation approach. This seminal study paved the way for numerous subsequent contributions. For instance, BFG24 evaluated the relationship between query features and prototypes while merging global context from two directions into local point features. Zhu25 proposed a practical approach based on prototype learning, addressing distribution discrepancies between support and query sets by implementing bias correction. Wei26 developed a method based on prototype alignment and label propagation to enhance FS-PCSS performance further. To address the issue of imprecise decision boundaries caused by limited labeled data, PEFC27 expands and calibrates class prototypes using information from query data in FS-PCSS. Hu28 tackled intra-class differences and incomplete category representation, while Ning29 improved this field through query-guided enhancement. TFDR30 addresses the inter-class and intra-class distribution bias issues in FS-PCSS. Li31 proposed a few-shot semantic segmentation framework for point clouds with decoupled localization and expansion. Through a structural localization module and a self-expansion module, this framework significantly improves the accuracy of cross-instance matching and the integrity of target segmentation. DPA32 proposes dynamically adjusting prototypes through prototype calibration and prototype distillation regularization to address the object variation issue between support prototypes and query features.

In addition to these contributions, several studies have applied these methods in real-world scenarios to demonstrate their practical potential. Li33 highlighted that those dynamic changes in three-dimensional point cloud data pose challenges for construction robots in understanding environmental information. Fayjie34 proposed a railway-specific FS-PCSS method, focusing on creating class prototypes for key infrastructure categories. Zhou35 made a significant advancement in autonomous driving by utilizing the temporal continuity of LiDAR data. Dai36 introduced a novel three-stage multi-prototype network for few-shot airborne laser scanning point cloud semantic segmentation, leveraging knowledge transfer from accurately annotated photogrammetric point clouds. While most of these methods focus on directly segmenting the target object, we are the first to apply an FS-PCSS method incorporating complementary background knowledge to eliminate interference areas, thereby improving segmentation performance. Moreover, we are the first to apply this few-shot learning approach to segment architectural cultural heritage structures. Although existing research has reported promising results, these methods primarily focus on extracting target features from the support set and transferring the learned knowledge to query points for precise segmentation, as shown in Fig. 2.

To overcome these limitations, we bring forward a brand-new framework, LUBK-Net (as shown in Fig. 2), which rethinks the FS-PCSS task from a new perspective. Unlike most previous methods committed to optimizing target prototypes for feature matching, our approach pays more attention to how to learn discriminative universal background knowledge to reduce noise interference on the feature distribution, thus achieving cross-domain target feature alignment, as shown in Fig. 3.

Recognizing that focusing on and understanding background knowledge during few-shot segmentation holds significant value for enabling models to effectively segment target components without interference, we propose a Background Attention Module (BAM). Specifically, we find it challenging to obtain reliable background prototypes in the few-shot setting. We explicitly model a common background prototype between the support set and the query set, which is used to segment background regions in specific architectural heritage scenarios. However, due to the absence of ground truth labels to supervise the background modeling process, we introduce an adaptive background loss function based on known target masks. By dynamically adjusting the computation of the background loss, we constrain the direction of background prototype generation. Building upon the optimized background prototype derived from the previous operations, we remove irrelevant background noise from the query features. This ensures the model concentrates on the foreground and accentuates important architectural details.

Furthermore, considering the inherent challenge of learning a well-structured prototype feature embedding space for distinguishing the target object itself, we introduce a Prototype Contrastive Learning (PCL) algorithm to optimize the prototype feature embedding. The introduction of Contrastive Learning37 emphasized improving feature representations by contrasting positive and negative samples. Tang38 introduced a new framework for point cloud segmentation that improves feature differentiation, particularly for boundary points. More recently, in the field of FS-PCSS, Wang39 made a pioneering contribution by introducing contrastive learning methods, explicitly proposing a self-supervised contrastive framework for few-shot learning pretraining. In contrast to these approaches, our method, Prototype Contrastive Learning, aims to strengthen the discriminative capability of prototypes for target objects, thereby helping the model effectively reduce the impact of interference targets and mitigate confusion between architectural categories. Cross-domain feature alignment is achieved through similarity matching between query points and the constructed prototype sample library. Finally, we apply a non-parametric metric learning paradigm to perform precise feature matching and category prediction.

In summary, LUBK-Net overcomes the limitations of traditional supervised methods in the context of few-shot segmentation of architectural cultural heritage by optimizing the cross-domain background feature distribution and strengthening the discrimination between target objects and the background. Even with extremely little annotated data, our method provides a powerful and efficient solution for accurately segmenting heritage building structures.

To conclude, our main contributions are outlined below:

-

(1)

This represents the initial endeavor to model and eliminate background regions in the few-shot semantic segmentation of architectural heritage point clouds, effectively reducing false optimistic predictions.

-

(2)

Our approach integrates two primary components: the Background Attention Module (BAM) and the Prototype Contrastive Learning (PCL). Our method learns discriminative background prototypes to optimize feature alignment, thereby enhancing the segmentation performance of target objects.

-

(3)

Our proposed framework demonstrates cutting-edge performance through rigorous testing on the SAA and ArCH datasets. It contributes novel perspectives to FS-PCSS and preserves architectural heritage.

Methods

This section provides the necessary preparatory knowledge. We first define the FS-PCSS task, as illustrated in Fig. 4. We follow the approach, adopting a training/testing paradigm for scenarios after the pretraining phase. Specifically, the categories in the dataset are divided into two categories: Cbase and Cnovel (\({C}_{\mathrm{base}}\cap {C}_{\mathrm{novel}}=\varnothing\)). The support set, denoted as \(S={\left\{\left({p}_{s}^{1,k},{y}_{s}^{1,k}\right),\cdots \,,\left({p}_{s}^{N,k},{y}_{s}^{N,k}\right)\right\}}_{k=1}^{K}\), consists of K groups, where K is a positive integer, of support point clouds \({p}_{s}^{n,k}\) for each of the N categories, along with the corresponding masks \({y}_{s}^{n,k}\). The query set, denoted as \(Q={\left\{\left({p}_{q}^{t},{y}_{q}^{t}\right)\right\}}_{t=1}^{T}\) consists of T pairs of query point clouds and their corresponding ground truth masks \({y}_{q}^{t}\), which used only during the few-shot training phase. Typically, each point cloud \(p\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times (3+{f}_{0})}\) consists of m points. Each point is associated with coordinate information in \(\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) and an extra feature in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{{f}_{0}}\), such as color information.

Overall framework

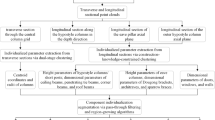

The overall framework of our proposed method is depicted in Fig. 5. In the Prototype generator section, we first elaborate on how to extract support features and query features from the input point clouds by means of an embedding network. Immediately following this, a prototype generator is designed to carry out the tasks of initial clustering and segmentation. The foreground and background features of the support sets are generated through the mask-based average pooling method. Then, the foreground and background prototypes are constructed using adaptive weighted averaging. Based on this, in the Background attention module section, we elaborate on the process of our focus on background knowledge learning in three steps in sequence. Specifically, the background modeling module aims to explicitly model the general background prototype representation to learn the cross-domain background feature distribution. At the same time, we propose an adaptive background loss algorithm that does not need to rely on actual background labels. Subsequently, the background filtering module is applied to filter out background noise from the query features. In the Prototypical contrastive learning section, according to the learned prototype representations, a positive sample library for foreground prototypes and a negative sample library for background prototypes are constructed, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to distinguish the target query area from the non-interested area. Finally, a non-parametric metric-learning method is adopted for feature matching, culminating in generating point-wise prediction labels.

Subsequently, the Prototype Generator (PG) extracts the support features to generate semantic prototype representations. Next, the Background Modeling Module (BMM) initializes background prototypes, learning background knowledge from the support and query features, and optimizes this process using Adaptive Background Loss (ABL). Concurrently, the Background Filtering Module (BFM) eliminates background noise. Finally, Prototype Contrastive Learning (PCL) differentiates between the target and background regions.

Prototype generator

The FS-PCSS tasks typically follow a two-stage training paradigm. During the pre-training phase, we retain the DGCNN as the backbone feature extractor to facilitate comparison with other approaches. Given the input point cloud, we define the support point cloud as \({P}_{s}^{n,k}\), and its corresponding binary mask as \({y}_{s}^{n,k}\). Leveraging the feature extractor, we first acquire the support features \({F}_{s}^{n,k}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times d}\) and the query features \({F}_{q}^{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times d}\). By conducting a softmax operation on the support features based on the mask, we obtain \({{\mathcal{W}}}_{FG}^{n}\) and \({{\mathcal{W}}}_{BG}\) which are then utilized as the adaptive weights for the support foreground features and background features, respectively. This empowers the model to adaptively zero in on the distinctions between the support target objects and the background areas while extracting features of different components. Subsequently, we apply a weighted-average operation to generate the foreground prototype \({P}_{FG}^{n}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) for the n-th class (n ∈ {1, …, N}) and a support background prototype \({P}_{BG}^{0}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\). The prototype set is denoted as P = {P0, P1, …, PN}, and Equations (1), (2), (3) and (4) for this process are presented as follows:

Where Φ(*) represents the backbone network feature extractor, m is the fixed number of points, i is an index variable, and ∣*∣ is the indicator that outputs 1 when * is true.

Background attention module

In this section, we will elaborate in detail on the components encompassed by BAM, namely the background modeling module (BMM), the adaptive background loss function (ABL), and the background filtering module (BFM), as shown in Fig. 5. In the FS-PCSS task, the background regions of architectural heritage may contain feature information like the target categories in terms of shape or texture. Especially in the case of scarce samples, it is difficult for the model to accurately learn the subtle differences between the target categories and the background based on the semantic information provided by a few samples, which undoubtedly negatively impacts the segmentation effect. Therefore, we are committed to designing a method that enables the model to establish a stable knowledge transfer ability between prototypes and query points while avoiding interference from background information irrelevant to the segmentation target.

To prompt the model to focus more on the background information and alleviate the potential significant feature deviation problem between the support set and the query set, we first guide the model aims to learn a robust universal background prototype from the support points and query points during the training process. Specifically, a background prototype \({P}_{BG}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{1\times 1\times d}\) is randomly initialized, where d is the channel dimension. Then, it is expanded to the same dimensional size \({\widehat{P}}_{BG}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times d}\) as the support features \({\widehat{F}}_{s}^{n,k}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times d}\) and query features \({F}_{q}^{f}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times d}\) after tensor reshaping and concatenation operations are performed, respectively. Here, we use the background modeling module (as shown in Fig. 5) to obtain the background prediction results of the support and query sets through segmentation. Equations (5) and (6) are as follows:

Among them, \({\mathcal{M}}(* )\) represents the background modeling module, ⊕ represents the concatenation operation, and \({Y}_{s/q}^{BG}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times 1}\) is the support or query probability result.

In FS-PCSS tasks, only ground-truth labels for target objects \({y}_{s}^{n,k}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times 1}\) and \({y}_{q}^{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m\times 1}\) are typically available, while background labels are absent. Additionally, architectural scenes often exhibit significant foreground-background class imbalance, with background regions usually occupying a larger proportion. This can cause models to overfit the background and neglect foreground objects, leading to biased universal prototypes that poorly represent real background feature distributions. To address this, we design an adaptive background loss to optimize background prediction during training. Let Ns = n × k × m and Nq = t × m denote the total number of points in the support and query sets, respectively. The foreground point ratios are computed as:

where \({\mathbb{I}}(\cdot )\) is the indicator function. The adaptive weights are then defined as:

with ε = 10−6 to avoid division by zero. These weights balance the contribution of foreground and background points based on their relative frequencies.

The adaptive background loss functions for the support and query sets are formulated as:

where \({Y}_{s}^{BG}(i)\) and \({Y}_{q}^{BG}(i)\) denote the predicted background probabilities for point i in the support and query sets, respectively.

This loss function encourages the model to assign low background probabilities (YBG → 0) to foreground points (where y = 1) and high background probabilities (YBG → 1) to all points, thereby learning a discriminative and generalizable background representation. The adaptive weights as and aq dynamically scale the loss to mitigate class imbalance, improving segmentation robustness.

The universal background prototype representation optimized through modeling aims to excavate the background knowledge contained in the support and sample sets. To filter out the background noise in the query features and enhance the model’s attention to the target objects, we further concatenate the extended universal background prototype \({\widehat{P}}_{BG}\) with the query features \({F}_{q}^{t}\), then use a convolutional block conv(*) to filter out the background noise points in the query set. The calculation formula is shown as Eq. (11):

where \({\widetilde{F}}_{a}^{t}\) represents the query features after filtering out the background noise, and conv(*) represents the 1 × 1 convolutional block.

Prototypical contrastive learning

Previous studies have attempted to address the fundamental problem of prototype deviation by generating multiple prototypes or enhancing semantic information. Nevertheless, these approaches have substantial limitations regarding expanding the feature distance between target objects of diverse categories and the background area. Inspired by the contrastive learning theory, we propose a prototype contrastive learning method to guide the model in learning robust and highly distinguishable prototype representations while optimizing the embedding effect of the query set in the feature space. Specifically, we construct a prototype sample library. The support foreground prototypes \({P}_{FG}^{n}\) are used as the positive-sample library, and the universal background prototypes \({\widehat{P}}_{BG}\) are used as the negative-sample library. Since the prototypes of different foreground categories may be affected by feature fluctuations due to limited sample sizes, we calculate the average value of the foreground prototype features to obtain an average vector \({\overline{P}}_{FG}\) that can represent the foreground-class features. The calculation formula is shown in Equation (12). Subsequently, we compute the cosine similarities between the filtered query features \({\widetilde{F}}_{q}^{t}\) and the dimension-expanded positive-sample library \({\widetilde{P}}_{FG}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) as well as the negative-sample library \({\widetilde{P}}_{BG}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) respectively, to obtain the similarity scores. On this basis, we introduce a temperature parameter τ to scale the scores. The specific calculation processes are shown in Equations (13) and (14). Finally, we introduce a margin threshold \({\mathcal{M}}\) to control the similarity gap between positive and negative samples and obtain the prototype contrastive loss. The specific formulas are shown in Equations (15) and (16).

Among them, n ∈ {1, 2, …, N} represents the category, \(\left\Vert * \right\Vert\) represents the norm of the vector, L2 respectively represent the positive and negative sample scores (whose values range from − 1 to 1), i represents the index factor, and li represents the condition for discriminating the foreground and background of the query. When the query label is greater than 0, li is assigned 1, indicating that the point is in the foreground; otherwise, it is assigned 0, indicating the background. \({\rm{MAX}}(* )\) is the maximum-value operator.

Based on the optimized feature embeddings, we adopt the non-parametric metric learning paradigm to precisely match each query point to the most similar category prototype, thereby achieving the final category prediction (including the background region). During the entire training process, our approach integrates the adaptive background loss, the prototype contrastive loss Lcontra and the main loss function Lmain to supervise the model’s processing of the predicted labels \({\widehat{y}}_{a}^{t}\) and the true labels in the training phase. The calculation formula of the main loss function is presented as Equation (17):

Among them, CE(*) represents the cross-entropy loss function. To make the method more clearly and intuitively understandable, we also present Algorithm 1 to expound the entire technical process concisely and explicitly.

Algorithm 1 Training process LUBK-Net for FS-PCSS

Input: Support set \(s={\left\{\left({p}_{s}^{1,k},{y}_{s}^{1,k},\ldots ,{p}_{s}^{N,k},{y}_{s}^{N,k}\right)\right\}}_{k=1}^{K}\), Query set \(Q={\left\{\left({p}_{q}^{t},{y}_{q}^{t}\right)\right\}}_{t=1}^{T}\), pre-trained model Θ, adaptive background loss weight β and prototype contrastive loss weight γ.

Output: Model parameters Θ for the training phase.

1: while no converge do

2: Sample the current batch of sets S and Q from Cbase and \({C}_{novel}({C}_{base}\cap {C}_{novel}=\varnothing )\);

3: Employ the pre-trained feature extractor to extract \({F}_{s}^{n,k}\) and \({F}_{q}^{t}\) according to Equations (1) and (2);

4: Use the prototype generator to calculate \(P=\left\{{P}^{0},{P}^{1},\ldots ,{P}^{N}\right\}\) according to Equations (3) and (4);

5: Use the background modeling module to get \({Y}_{s/q}^{BG}\) according to Equations (5) and (6);

6: for i in 1, …, N do

7: Use the adaptive background loss to calculate \({L}_{s/q}^{BG}\) according to Equations (7), (8), (9), (10);

8: end for

9: Use the background filter module to get \({\widetilde{F}}_{q}^{t}\) according to Equation (11);

10: for i in 1, …, N do

11: Use the prototypical contrastive learning loss to calculate Lcontra according to Equation (16);

12: Use the cross-entropy loss to calculate Lmain according to Equation (17);

13: end for

14: Compute the total loss \({L}_{total}={L}_{main}+\beta {L}_{s/q}^{BG}+\gamma {L}_{contra}\).

15: end while

Results

Dataset introduction

(1) The Beiding Niangniang Temple, which is among the five famous “Dings” in the history of Beijing, lies on the northern extension of the city’s central axis and functions as a crucial landmark in this region. The temple occupies an area of approximately 9700 square meters and features a traditional layout with four courtyards and five levels. As a quintessential example of Chinese traditional wooden architecture, the temple primarily comprises a roof, body, and base platform. The roof is adorned with gray tiles and decorative ridge beasts, significantly enhancing its cultural and artistic value. The red walls provide structural support, while the wooden doors and windows are intricately carved with delicate lattice patterns.

In this study, we used a FARO Laser Scanner Focus3D X130 to capture high-precision 3D point clouds of three main halls within the temple complex. The raw scans were registered and merged to form a cohesive dataset. Figure 6 displays front, side, and back views of the dataset, providing a detailed representation of the ancient architectural scene. Statistical information on the architectural style and point cloud count for the three scenes of the SAA dataset is summarized in Table 1. The dataset encompasses nine categories: beam, window, door, column, roof, floor, stylobate, wall, and Step. These categories cover both structural and decorative components typical of traditional Chinese architecture. As shown in Fig. 7, we illustrate each architectural component from the three scenes and provide the total point cloud count for each component.

Regarding annotation details, the data were manually annotated at the point level using CloudCompare software, following a labeling protocol consistent with the S3DIS format (txt files). Approximately 71 million points across the three scenes were annotated. Each point cloud data entry retains six key pieces of information: coordinates (XYZ) and color (RGB). The SAA dataset presents several challenges pertinent to few-shot learning in heritage contexts: (1) significant foreground-background imbalance, as structural elements (beams, columns) occupy a smaller spatial proportion compared to walls and floors; (2) fine-grained inter-class similarities (between doors and windows, or different wooden members); and (3) complex occlusions and clutter typical of real-world scan environments. These characteristics make SAA a suitable benchmark for evaluating the robustness of FS-PCSS methods.

(2) ArCH was developed by the University of Turin in collaboration with various other universities and institutions, focusing on the point cloud data associated with historical architectural heritage. We selected five representative architectural regions, which encompass nine distinct building categories: vault, column, floor, window, wall, moldings, stair, arch, and roof, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The details of this dataset are shown in Table 2.

Dataset setup

The SAA and ArCH datasets were divided into 1790 and 2205 blocks, respectively, from which we randomly sampled 2048 points per block. For each dataset, the semantic categories were partitioned into two disjoint subsets: one for training and the other for testing. This process was conducted with two rounds of cross-validation, as illustrated in Table 3. We generated multiple N-way K-shot sets for training purposes and evaluated the model across 100 sets.

Training details

During the pretraining phase, DGCNN5 was employed as the feature extractor for both support and query features. Pretraining was conducted on the base classes. We set the batch size to 32, the learning rate to 0.001, the weight decay to 0.0001, and the decay rate to 0.5. The model was trained for 150 epochs using the Adam optimizer (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.99). During the meta-training phase, we initialized feature extraction with pre-trained weights and used the Adam optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001, with the learning rate halved every 5000 iterations. In the PCL, the temperature parameter τ was set to 0.1, the margin threshold \({\mathcal{M}}\) to 0.5, and the weight of the prototype contrastive loss γ to 0.05. The adaptive background loss weight β was set to 0.5. The model underwent 40,000 iterations of training. Each episode was constructed by randomly selecting categories of architectural heritage.

Evaluation

During the meta-testing phase, 100 episodes were randomly selected from novel classes (those not learned during training) to evaluate the model. The experiments were executed on an RTX 2080 Ti GPU.

Evaluate metrics

We utilize the averaged Intersection-over-Union (mIoU) as the evaluation metric for subsequent comparative experiments and ablation studies. Unlike prior methods, our experiments are designed to highlight the disparities among various approaches in differentiating between foreground and background regions. To achieve a more comprehensive comparison, we report the foreground-background IoU (FB-IoU) in each split (split = 0/1). Meanwhile, the FB-IoU is calculated by treating all object classes as the foreground and taking the average of the IoU values for both the foreground and the background. Since all metrics are derived from IoU calculations, Eq. (18) is presented:

Here, TP indicates accurately-classified positive samples, FP represents wrongly-identified negative samples as positive, TN denotes correctly-recognized negative samples, and FN refers to misclassified positive samples as negative.

Results on the SAA dataset

Table 4 compares our method with seven leading ones on the SAA dataset. In N-way K-shot (N = 1/2, K = 1/5) scenarios, ours outperforms others. In the 1-way 1-shot setting, our average mIoU is 6.26% higher than DPA’s. Compared to AttProtoNet, it improves by 16.72% (split = 0) and 9.03% (split = 1), averaging 12.86%. In other settings, our method’s overall average accuracy increases by 2.94%, 1.46%, and 6.54% compared to top-performing models. Table 5 shows the performance in distinguishing foreground and background regions. In 1-way settings, our method leads in both splits. In 1-way 1-shot, it is 4.88% and 4.95% better than DPA in split = 0 and 1, respectively, averaging 4.91% improvement; in 1-way 5-shot, our Avg value is 2.1% higher than MPTI. In the 2-way 1-shot, compared to MPTI, ours improves by 1.35% in each split, averaging 1.35%; in the 2-way 5-shot, our average value is 6.35% higher than AttProtoNet. As illustrated in Fig. 9, we intuitively present the results of our method compared with seven classical approaches on the SAA dataset across two metrics (mIoU and FB-IoU), facilitating clear comparison.

Results on the ArCH dataset

Compared to SAA, ArCH has different architectural styles and more complex scenarios. Table 6 shows the results of seven methods on ArCH. In the 1-way 1-shot setting, our method’s average mIoU is 4.16% higher than DPA (SOTA). Compared to AttProtoNet, it boosts mIoU by 14.37% (split = 0) and 23.24% (split = 1), averaging 18.81%. In other settings, our overall average accuracy increases by 1.63%, 2.93%, and 1.47%. Our method excels on ArCH, proving its effectiveness. Table 7 shows foreground-background distinguishing performance. In the 1-way settings, our method tops both splits. The 1-way 1-shot outperforms DPA by 6.51% (split = 0) and 3.56% (split = 1), averaging 5.03% improvement; in the 1-way 5-shot, our Avg is 3.01% higher than QGPA. In the 2-way 1-shot, compared to QGPA, ours improves by 2.65% and 1.21% in each split, averaging 1.93%; in the 2-way 5-shot, our average is 2.39% higher. As illustrated in Fig. 10, we intuitively present the results of our method compared with seven classical approaches on the ArCH dataset across two metrics (mIoU and FB-IoU), facilitating clear comparison.

Visualization analysis

Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the qualitative results of the proposed method in the 1-way 1-shot scenario on our datasets, respectively, compared with ground truth and groundbreaking method-AttMPTI. In the SAA dataset, Goddess Hall and Hall of Heavenly Kings were used as support and query sets, with novel classes including roof, wall, beams, and columns. The proposed method accurately identifies these classes, particularly excelling in distinguishing fine-grained components like beams and columns (Fig. 11, rows 5–8). In the ArCH dataset, with 5_SMV_chapel_2to4 and 6_SMV_chapel_24 as support and query sets, our method outperformed AttMPTI. It provided more accurate and refined segmentation for roofs, moldings, walls, and columns and incredibly complete and precise column segmentation. AttMPTI, however, had significant misclassifications and missed detections (Fig. 12, rows 4 and 8). Figure 13 shows the visualization results of the feature dimensionality reduction of our datasets using the t-SNE40 tool. These results demonstrate that our method has excellent object-discrimination ability across various architectural styles and categories and alleviates the domain gap caused by feature differences.

Ablation analysis

This section conducts an ablation study under the 1-way 1-shot setting on the SAA dataset, benchmarking against AttProtoNet to validate the significance of the proposed modules.

Effects of PG

As shown in Table 8, we first evaluate the prototype generator (PG). The second row demonstrates that the proposed method achieves a 1.73% performance improvement (61.28% vs. 59.55%) compared to AttProtoNet. Meanwhile, the seventh row reveals that integrating only BAM and PCL leads to an 11.47% accuracy increase, highlighting the indispensable role of PG in generating initial component prototypes.

These results further indicate that when the support set contains inconsistent or noisy samples, the simple averaging strategy in AttProtoNet may degrade prototype quality. In contrast, our adaptive weighted averaging approach enables more flexible and robust prototype generation by effectively integrating support set features.

Effects of BAM

Table 8 demonstrates that our experiments, using AttProtoNet as the baseline, achieve an average mIoU improvement of 9.11% (third row), validating the effectiveness of the proposed module. Notably, when BAM is removed (fifth row), the performance gain drops to only 4.56%, indicating that this module plays an indispensable role in overall accuracy enhancement.

To further investigate how the three components of BAM individually influence and constrain the segmentation accuracy of structural components, we conduct an ablation study (Table 9). Using only BMM has a negligible impact on model performance. This is because, while it captures common background features in architectural point cloud scenes, it lacks supervised optimization and subsequent processing; Using only BFM leads to a significant 10.89% drop in accuracy, even falling below the original baseline. We argue this is reasonable, as incorrectly leveraging background prototypes to remove noise may adversely affect foreground segmentation; Removing BFM results in a 2.59% decline, suggesting that merely extracting background knowledge without noise suppression introduces ambiguity in target component recognition. Most critically, removing ABL causes a catastrophic 12.22% performance deterioration. We attribute this to the fact that unsupervised background prototype optimization may lead to erroneous prototype generation. When combined with the background filtering mechanism, this severely degrades the model’s discriminative ability, significantly weakening its robustness. This analysis underscores the synergistic necessity of BAM’s components in ensuring precise and reliable segmentation.

Effects of hyper-parameters

Figure 14a–d reports the effects of hyperparameters: temperature parameter τ, margin threshold \({\mathcal{M}}\), prototype contrastive loss weight γ, and adaptive background loss weight β. The τ scales similarity in prototype contrastive learning. Evaluating values [0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2] reveals lower τ enhances sample contrast, while higher τ smooths similarity scores. For \({\mathcal{M}}\), testing values [0.3, 0.5, 0.7] shows higher \({\mathcal{M}}\) improves class discrimination by increasing separation, while lower \({\mathcal{M}}\) risks category confusion and reduces accuracy. Assessing γ values [0.01, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1] finds high dominates contrastive loss, harming task optimization and performance. Evaluating β values [0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0] shows low β leads to inaccurate background predictions, and high β weakens foreground segmentation accuracy.

Computational complexity

Table 10 categorizes the comparison of computational complexity into two groups. The first group encompasses AttMPTI and QGE, whereas the second group consists of AttProtoNet, QGPA, DPA, and our proposed approach. Despite having more parameters, the methods in the second group demand less computational memory, substantially reduce inference time, and achieve a remarkable boost in accuracy. Compared with DPA and QGPA, our method significantly enhances accuracy while maintaining efficiency, delivering excellent segmentation results while sustaining efficient computational performance.

Discussion

In this study, we propose LUBK-Net, a novel framework designed for few-shot point-cloud semantic segmentation (FS-PCSS) of architectural cultural heritage. Our approach introduces two key components: the Background Attention Module (BAM) and the Prototype Contrastive Learning (PCL) mechanism. BAM explicitly learns a universal background prototype through an adaptive loss, effectively suppressing background noise and reducing feature distribution shifts between support and query sets. PCL enhances the discriminability between foreground objects and the background by enforcing a margin-based separation in the prototype embedding space. Together, these modules enable robust feature alignment and significantly improve segmentation accuracy under few-shot regimes.

Experiments conducted on the self-built SAA dataset and the public ArCH dataset demonstrate that LUBK-Net consistently outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods across various few-shot settings. The improvements are especially notable in challenging scenarios with large foreground-background imbalance and fine-grained architectural details. Ablation studies confirm the individual contribution of each proposed module, and hyper-parameter analysis provides practical guidance for deployment.

Beyond technical contributions, this work has direct implications for real-world heritage conservation. Accurate point-cloud segmentation is a fundamental step in digitizing historic structures. By enabling precise extraction of architectural components (e.g., beams, columns, roofs) with minimal annotated data, LUBK-Net supports several critical conservation workflows: (1) Digital documentation - automatically generating semantically rich 3D models for archival and condition assessment; (2) Virtual restoration and display - creating detailed virtual environments for public education and immersive experiences; (3) Intelligent monitoring - facilitating the detection of structural changes or deteriorations over time through comparative analysis of segmented elements. The efficiency of our few-shot approach makes it particularly suitable for heritage sites with limited available annotations, lowering the barrier to high-quality digital preservation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to systematically address background modeling and prototype contrastive learning in FS-PCSS for architectural heritage. While the method is validated in this domain, its core design—background-aware prototype learning and contrastive feature enhancement—is generic and could be adapted to other few-shot segmentation tasks where class imbalance and background interference are common, such as the few-shot segmentation of point cloud data of buildings with different styles, both ancient and modern, indoors and outdoors.

Nonetheless, the proposed approach has certain limitations. First, LUBK-Net relies on a pre-trained feature extractor, and its performance is thus influenced by the quality and domain relevance of the pre-training data. Second, the introduced background modeling and contrastive learning modules increase computational complexity compared to simpler prototype-based methods, which may affect scalability when processing extremely large-scale point clouds. Future work will focus on developing more efficient network architectures and exploring self-supervised pre-training strategies to reduce dependency on annotated base classes and improve computational efficiency.

LUBK-Net offers an effective and efficient solution for few-shot semantic segmentation of heritage point clouds. By advancing both algorithmic robustness and practical applicability, this study contributes to the growing intersection of computer vision and cultural heritage conservation, providing a scalable tool for the digital safeguarding of architectural heritage.

Data availability

publicly accessible Architectural Cultural Heritage dataset (ARCH): The ARCH dataset is openly available at https://archdataset.polito.it/. Due to heritage conservation protocols, the SAA dataset is currently not publicly available. However, the annotation guidelines, a sample subset, and detailed metadata are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author to facilitate reproducibility and further research.

References

Hu, Q. et al. Randla-net: Efficient semantic segmentation of large-scale point clouds. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 11108–11117 (2020).

Jiang, L. et al. Guided point contrastive learning for semi-supervised point cloud semantic segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 6423–6432 (2021).

Li, H. et al. MVPNet: A multi-scale voxel-point adaptive fusion network for point cloud semantic segmentation in urban scenes. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 122, 103391 (2023).

Li, L., Shum, H.P. & Breckon, T.P. Less is more: Reducing task and model complexity for 3d point cloud semantic segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 9361–9371 (2023b).

Wang, Y. et al. Dynamic graph cnn for learning on point clouds. ACM Trans. Graph. 38, 1–12 (2019).

Xie, Z. et al. Cross modal networks for point cloud semantic segmentation of Chinese ancient buildings. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 131 (2025).

Cao, Y., Teruggi, S., Fassi, F. & Scaioni, M. A comprehensive understanding of machine learning and deep learning methods for 3d architectural cultural heritage point cloud semantic segmentation. Ital. Conf. Geomatics Geospatial Technol. 329–341 (Springer, 2022).

Morbidoni, C., Pierdicca, R., Paolanti, M., Quattrini, R. & Mammoli, R. Learning from synthetic point cloud data for historical buildings semantic segmentation. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 13, 1–16 (2020).

Pellis, E. et al. Assembling an image and point cloud dataset for heritage building semantic segmentation. ISPRS Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 46, 539–546 (2021).

Pierdicca, R. et al. Point cloud semantic segmentation using a deep learning framework for cultural heritage. Remote Sens. 12, 1005 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Integrating colored LiDAR and YOLO semantic segmentation for design feature extraction in Chinese ancient architecture. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 316 (2025).

Lawin, F.J. et al. Deep projective 3D semantic segmentation. Comput. Anal. Images Patterns. 95–107 (Springer, 2017).

Tatarchenko, M., Park, J., Koltun, V. & Zhou, Q.-Y. Tangent convolutions for dense prediction in 3d. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 3887–3896 (2018).

Choy, C., Gwak, J. & Savarese, S. 4d spatio-temporal convnets: Minkowski convolutional neural networks. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 3075–3084 (2019).

Poux, F. & Billen, R. Voxel-based 3D point cloud semantic segmentation: Unsupervised geometric and relationship featuring vs deep learning methods. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 8, 213 (2019).

Qi, C.R., Su, H., Mo, K. & Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep learning on point sets for 3d classification and segmentation. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 652–660 (2017).

Engelmann, F., Kontogianni, T. & Leibe, B. Dilated point convolutions: On the receptive field size of point convolutions on 3d point clouds. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 9463–9469 (2020).

Hua, B.-S., Tran, M.-K. & Yeung, S.-K. Pointwise convolutional neural networks. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 984–993 (2018).

Thomas, H. et al. KPConv: Flexible and deformable convolution for point clouds. Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 6411–6420 (2019).

Wang, S., Suo, S., Ma, W.-C., Pokrovsky, A. & Urtasun, R. Deep parametric continuous convolutional neural networks. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2589–2597 (2018).

Matrone, F. et al. A benchmark for large-scale heritage point cloud semantic segmentation. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 43, 1419–1426 (2020).

Biehl, M., Hammer, B. & Villmann, T. Prototype-based models in machine learning. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 7, 92–111 (2016).

Zhao, N., Chua, T.-S. & Lee, G.H. Few-shot 3d point cloud semantic segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 8873–8882 (2021).

Mao, Y., Guo, Z., Xiaonan, L., Yuan, Z. & Guo, H. Bidirectional feature globalization for few-shot semantic segmentation of 3d point cloud scenes. Int. Conf. 3D Vis. 505–514 (IEEE, 2022).

Zhu, G., Zhou, Y., Yao, R. & Zhu, H. Cross-class bias rectification for point cloud few-shot segmentation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 25, 9175–9188 (2023).

Wei, M. Few-shot 3D Point Cloud Semantic Segmentation with Prototype Alignment. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. Technol. 195–200 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Prototype expansion and feature calibration for few-shot point cloud semantic segmentation. Neurocomputing 558, 126732 (2023).

Hu, D., Chen, S., Yang, H. & Wang, G. Query-guided support prototypes for few-shot 3D indoor segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 34, 4202–4213 (2023).

Ning, Z., Tian, Z., Lu, G. & Pei, W. Boosting few-shot 3d point cloud segmentation via query-guided enhancement. Proc. ACM Int. Conf. Multimed. 1895–1904 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Two-stage feature distribution rectification for few-shot point cloud semantic segmentation. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 177, 142–149 (2024).

Li, Z., Wang, Y., Li, W., Sun, R. & Zhang, T. Localization and expansion: A decoupled framework for point cloud few-shot semantic segmentation. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. 18–34 (Springer, 2024).

Liu, J. et al. Dynamic Prototype Adaptation with Distillation for Few-shot Point Cloud Segmentation. Int. Conf. 3D Vis. 810–819 (IEEE, 2024).

Li, X., Feng, L., Li, L. & Wang, C. Few-shot meta-learning on point cloud for semantic segmentation. arXiv:2104.02979 (2021).

Fayjie, A. R. & Vandewalle, P. Few-shot learning on point clouds for railroad segmentation. Electron. Imaging 35, 1–5 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. TeFF: Tracking-enhanced Forgetting-free Few-shot 3D LiDAR Semantic Segmentation. IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. Intell. Robot. Syst. 14103–14110 (2024).

Dai, M. et al. Multiprototype relational network for few-shot ALS point cloud semantic segmentation by transferring knowledge from photogrammetric point clouds. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–17 (2024).

Khosla, P. et al. Supervised contrastive learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 18661–18673 (2020).

Tang, L. et al. Contrastive boundary learning for point cloud segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 8489–8499 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Few-shot point cloud semantic segmentation via contrastive self-supervision and multi-resolution attention. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 2811–2817 (2023).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Snell, J., Swersky, K. & Zemel, R. Prototypical networks for few-shot learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 4077–4087 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following funding sources: National Key R&D Program of China [2018YFC0807806, 2023YFC3807400, 2023YFC3807404, 2023YFC3807404-1]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [42171416]; Additional institutional support was provided by: State Key Laboratory of Mapping and Remote Sensing Information Engineering, Wuhan University [19E01]; State Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Engineering [SKLGIE2019-Z-3-1]; Ministry of Natural Resources (Key Laboratory of Digital Mapping and Land Information Applications) [ZRZYBWD202102]; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (Software Science Research Project) [R2020287]; Beijing Social Science Foundation [21JCA004].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.L. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. J.H.Z. analyzed data. Y.H.Z. performed experiments. Y.P.Y. supervised the project and edited the manuscript. Z.M.C. secured funding. J.F.Z. improved the methods. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Zhao, J., Zhang, Y. et al. Learning discriminative universal background knowledge for few-shot point cloud semantic segmentation of architectural cultural heritage. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 26 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02292-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02292-8