Abstract

Prehistoric sites are important materials for understanding prehistoric civilization. This study addresses the limitations of current archaeological databases, which often suffer from fragmented data structures, weak spatiotemporal integration and an underutilization of GIS capabilities in spatial analysis and visualization. Therefore, a spatiotemporal data model is designed for the integration of archaeological information. Based on a framework of archaeological reports for prehistoric sites in China, a five-dimensional space-time architecture is introduced through the excavation and laboratory identification of prehistoric sites, namely, site-square unit-layer-feature-cultural periodization. This architecture enables the integration of multidisciplinary data and achieves a unified representation of the spatial, temporal and cultural attributes of prehistoric sites. The experiments demonstrate that the model supports retrievals of spatial relationships among multidisciplinary archaeological entities, statistics of features and remains, and cultural comparisons within spatial contexts, offering a spatial perspective for archaeology and provide a robust data and a technical foundation for comprehensive research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prehistoric archeology offers a critical long-term perspective on the dynamics of human social evolution and the origins of cultural diversity1,2. Prehistoric sites can provide critical insights into prehistoric life and the development of early civilizations3. However, the study of prehistoric sites is complex because of the lack of historical records4 and variations in preservation status5,6. Archeological databases can integrally store and manage multidisciplinary archeological information, which enhances the analysis and utilization of the information of China’s prehistoric sites. Consequently, archeological databases of prehistoric sites play a crucial role.

Existing archeological databases can be divided into two categories according to their approach to handling spatial data: non-spatial databases and spatial databases.

Non-spatial databases mainly employ database management systems (DBMSs) to record structured archeological data. These databases consist of many tables with primary keys and foreign keys, and the tables contain multiple fields that record specific attributes, with defined data types ensuring the accuracy and consistency of the entered information7,8. Despite the shared structure, they vary in the range and nature of the archeological attributes and relational elements that structure the database. Most archeological databases store some common information with a focus on unearthed artifacts, such as the name, material, shape, classification, preservation status, and time of the artifacts9,10,11. Some archeological databases store specific information based on their design targets. For example, for ceramics and potteries, details are recorded of the chemical analysis method and results, clay comment, picture, period, and name of the site where they are unearthed and recorded12,13. However, these types of databases cannot manage spatial information such as location and geometry, making them unsuitable for storing data from archeological sites where spatiotemporal relationships are highly emphasized.

Spatial databases employ spatial DBMS to connect spatial data with non-spatial data and manage the data integrally. In addition to non-spatial information, these databases record spatial information from archeological sites. Some databases only treat archeological sites as points, record their location, and disregard their shape and size14,15,16. Other databases record the spatial location of archeological sites or research areas with vector data such as points, polylines, and polygons17. Moreover, some spatial databases not only consider the coordinates, but also record the shapes, sizes, and topological relationships of the sites and their components to better express the data of archeological sites spatially18,19. The studies cited above have carried out data modeling of archeological information, but they did not document comprehensive information about the archeological sites and did not fully reflect the relationships among different spatial entities.

Unlike archeological databases, the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) has made some contributions to the semantic unification of cultural heritages. Its extensions, CRMarchaeo and CRMgeo, provide semantic specifications for some archeological classes (e.g., “excavation processing unit” and “stratigraphic unit”) and properties (e.g., “investigated” and “distributed”)20,21,22,23. Despite its broad applicability in archeology, it is not a database and cannot support the storage and management of spatial and interdisciplinary information in archaeometry.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to sort and organize archeological information from various types and disciplines and design a data model to integrate the multidisciplinary spatiotemporal data of prehistoric sites from archeological reports. In this study, an approach for the data modeling of prehistoric sites is proposed, with a spatial architecture of square unit-layer-feature-remain-cultural periodization to reflect the core principles of prehistoric site investigation and excavation. In this way, units at different levels of prehistoric sites can be effectively linked together through spatial relationships, and data from different disciplines can be interconnected, which provides a digital infrastructure for the systematic collection, management, analysis, statistics, and visualization of archeological spatial datasets.

In the next section, the content of the archeological reports is analyzed as archeological entities and their relationships. On the basis of the entities and relationships, a conceptual data model is proposed in the section “Methods”. A case database is then constructed with an ESRI Geodatabase in the section “Results” to validate the data model, which achieves the proposed objectives and demonstrates its ability to spatiotemporally integrate multidisciplinary archeological information from prehistoric sites.

Methods

Analysis of archeological report content

Archeological reports are systematic records of the features and remains unearthed and the coexistence relationships between various artifacts and features. As primary outputs of fieldwork, they form the essential foundation for archeological analysis and interpretation24,25. Rich in content, archeological reports encompass multidisciplinary information such as archeological stratigraphy, typology, and archaeometry. These reports play a crucial role in advancing our understanding of prehistoric human behavior, subsistence strategies, and social dynamics, while also providing key insights into spatial organization and environmental transformations26,27,28. Therefore, a comprehensive and effective parsing of the content of archeological reports is the basis for guaranteeing the rationality of data model design.

In this study, a comprehensive analysis of numerous archeological reports in China is conducted by examining their structural frameworks, content, and approaches to data organization and processing, and key considerations are outlined for interpreting and managing archeological data. The informational structure of reports on prehistoric sites is summarized in Fig. 1. In this structure, squares primarily represent the key elements in archeological reports, and the relationships between these elements form the foundational components of various archeological disciplines. In addition to the usual text description, the concrete or abstract information of these elements is often visually depicted through accompanying illustrations.

Archeological reports organize materials separately for each type of spatial unit. The structure of an archeological report usually consists of three parts: an overview, a description of the archeological fieldwork, and a conclusion29. The overview section describes mainly the geographic background of the site and information on excavation activities, while the conclusion summarizes the age, spatial pattern, and cultural phasing of the site. The description is the core content of an archeological report, which is usually divided into the stratigraphic layer, features, and remains. The stratigraphic layer, as the basic stratigraphic unit in archeological stratigraphy, is described primarily by its basic information, such as the layer number, accumulation property, geometric attributes, and period, and the relationships between layers and the main excavated objects. Features, which are the evidence of human activity composed of cultural materials within a cultural layer after decay or disappearance, are described predominantly by their geometric attributes and stratigraphic relationships. Compared with square units (also Wheeler box-grids), features are original natural units within the site. Therefore, they are usually separated into different types in archeology, such as ash pits, house foundations, and tombs. Remains are primarily described by the location, type, quantity, preservation status, and scientific testing results through experimental analysis. Archeological reports often adopt a typological approach and summarize the characteristics of excavated artifact types based on attributes such as texture or function, type, and model through categorization and description. The description of each type of artifact is often followed by a list of the typical individual artifacts unearthed and introduces information on the place in which they were unearthed and on their individualized characteristics; it often has an artifact diagram attached.

The study of biological remains includes the identification of unearthed plants, animals, and human bones. Archaeobotany focuses primarily on flotation methods and the statistical analysis of plant remains30. Plant remains are mainly categorized into plant macroremains (crops such as grains and non-crops such as weeds) and plant microremains (phytoliths, spore pollen, starch granules, etc.)31,32,33. Macroremains are further identified by taxonomy and analyzed by factors such as the excavation location, morphology, degree of maturity, and preservation status34. Microremains are also reported with statistical data on their types and numbers. Animal remains are quantified by indicators such as the number of remains, the total number of fragments, the number of identified specimens, and the minimum number of individuals, categorized by taxonomy. Based on these data, further indicators such as abundance, diversity, and ecological niche breadth are determined, which shed light on human survival strategies and the surrounding environment35,36. In addition, the study of human bones includes various aspects such as physical anthropology, paleopathology, ancient DNA research, and dietary research37. Archaeometric identification helps determine a tomb owner’s identity, ethnic background, and customs, and provides scientific data for understanding prehistoric societies38.

Stratigraphic layers, features, and remains are interrelated. The planimetric map of features depicts the spatial topological relationships between features and square units in the horizontal plane by emphasizing their adjacency or separation. In contrast, the profile reflects vertical stratigraphic relationships and indicates the positioning of remains within stratigraphic sequences. These relationships typically involve stratigraphic stacking and disturbance patterns, which are essential for understanding the chronological and depositional context of the site. In addition, the opening layers are typically used to describe the layer in which the mouth of the feature is located. Beyond textual descriptions and sketch maps, “connection diagrams” (or Harris Matrices) are often used in archeological reports to represent the stratigraphic relationship between features and the stratigraphy39.

Design considerations

Archeological data provide rich spatial and temporal information. The core of archeological excavation is to understand past human behaviors through spatial sampling40. Settlement archeology, in particular, includes both the internal structure of sites and their external relationships41, making spatial analysis crucial for comprehensively understanding the dynamics and distribution of a site’s components. Spatialization constitutes the foundation of archeological spatial analysis and allows the processing and interpretation of spatial data. Spatialization not only supports multidisciplinary, quantitative research and the comparative analysis of archeological findings through spatial datasets, but also provides technical support for the management and analysis of archeological activities at various macro and microscales.

With respect to the temporal dimension, the history of sites is inevitably related to the chronological sequences. Time and space, as an ordered system, form the basis for archeological analysis. Only by combining time and space can cultural and social evolution be better understood. Therefore, temporal information such as the rise and fall of settlements has also become important for clarifying the evolution of settlements, which is conducive to the construction of a vertical development pattern of prehistoric sites.

Accordingly, the three objectives of constructing an archeological spatiotemporal data model are as follows.

The first objective is spatialization, aimed at capturing the spatial dimensions of archeological data. It involves reconstructing the ancient environment by integrating both key parameters and their spatial dynamics. Additionally, Geographic Information System (GIS) is employed to represent precise locations and shapes, scaling from the entire site down to its internal units, which enables detailed analysis of the site’s spatial layout and structure.

The second objective centers on the comprehensive integration of multidisciplinary archeological information. It brings together traditional archeological data from stratigraphy and typology, synthesizing details from reports on a site’s location, layers, artifacts, and features. Furthermore, it incorporates archaeometric data derived from scientific analyses, including technical reports from archaeobotany, zooarchaeology, anthropology, and chronology.

The third objective is to facilitate spatial statistics and comparative analysis. This includes conducting statistical analysis on data from individual excavation units, incorporating both spatial and non-spatial attributes. The results are visualized through distribution maps of features and remains, aiding in the interpretation of cultural evolution within a settlement. The analysis also extends across multiple sites, comparing spatial distributions to document diverse phenomena and identify broader patterns linked to environmental and historical factors.

Entities and relationships design

A conceptual model is a type of data model that represents an abstraction of real-world entities and their interconnections. Such a model serves as the first and foundational step in database design before the logical and physical stages. Based on an entity-relationship (ER) model, spatiotemporal objects such as sites and square units can be identified from archeological reports, and the attributes and relationships can be designed.

Prehistoric sites exist in certain natural and social environments and include natural elements such as rivers and terrain, and social elements such as roads. Archeologists have carried out many excavation activities at prehistoric sites. Through the deployment of square units by the Wheeler–Kenyon method, many kinds of features, artifacts, and remains of plants, animals, and human bones have been unearthed. The stratigraphic section can be obtained through square units, where the features are excavated. Moreover, the features are buried in stratigraphic layers, which contain the stratigraphic layer information. In the features, various artifacts and biological remains are unearthed. The types and styles of artifacts are representative of the cultural stage, and are used as division evidence for the cultural periodization of the sites.

According to the conceptual understanding of main objects in archeology and the analysis of the content structure of archeological reports, several entities are abstracted. These entities can be directly modeled as geospatial features for GIS analysis, and they provide the foundation for constructing a conceptual data model of prehistoric sites. The attributes and spatial information of the site constitute the core content of conducting archeological research on prehistoric sites, and they are located within a certain spatial scope and time course. The excavation spot is the location where excavation activities are carried out. As the basic working unit of archeological excavation activities, the square unit, with its regular spatial arrangement, is the basic grid in the process of field archeology. It links the sites at the macrolevel and the features and remains at the microlevel. The feature is the basic unit that constitutes the spatial composition of archeological excavation objects. Its geometrical form and spatial distribution are basic elements that make up the structure of sites. Stratigraphic layers are spread throughout the excavation area and are reflected in the profiles of square units. The morphology of stratigraphic accumulations varies across geographic locations and offers the basic information for studying the spatiotemporal structure of the sites. Artifacts and biological remains have specific excavation sites. A spatial statistical analysis of their related attributes can reveal the basic characteristics of human activities in prehistoric societies. The above objects with spatial information are designed as the main spatial entities in the data model and stored as feature classes (including polygons, polylines, and points).

Different types of elements are designed according to the characteristics of each spatial entity. Every archeological excavation activity has a defined geographical scope, therefore the excavation spots are separately modeled as both polygons and points to express their locations. A square unit consists of three parts: the main body, the partition beams, and the key columns, and it mainly includes regular square grids, and each occupies a certain spatial range. Consequently, they are modeled as polygons. Features have specific forms and occupy a relatively small area; thus, they can also be modeled as polygons. Stratigraphic layers are often displayed in the form of profiles. Considering that archeological fieldwork is primarily performed by sampling, and that stratigraphic data in archeological reports are mostly presented as cross-sections, the excavated stratigraphic layers represent only the stratigraphic condition of the line where they are excavated. Additionally, they are not uniformly distributed in space. Instead of adopting 3D modeling to construct them, we chose the line along which the profile was drawn as the spatial location of layer accumulation. Therefore, stratigraphic layers are modeled as polylines. The volume of artifacts and biological remains is relatively small compared with that of the excavation area. Therefore, they are modeled as points.

Because of the differences in the types of features, we also design five main features as subtypes. These include house foundations, ash pits, tombs, trenches, and walls, which inherit the attributes from the entity “feature.” For each subtype, we can design and add specific attributes according to its characteristics and the needs of the research.

Since a trial trench is a special type of square unit, the entity “trial trench” is designed to inherit from the entity “square unit”.

Plant, animal, and human bone remains are the most common biological remains and are collected and identified through archaeometry. They have common information such as excavation location, chronological information, preservation status, and their own specific parameters. Hence, they inherit the attributes from the entity “biological remains” as subtypes. We also add unique attribute fields according to the research needs.

In addition, regarding the geographical background of the prehistoric site, we model the entities “river” and “road” as polylines, the entities “excavation area” as polygons, and the entities “terrain” as raster datasets.

The objects with negligible areas are abstracted as non-spatial entities, since their geographic location information is difficult to directly express or is of secondary importance compared with other information. Their spatial locations are represented by the place where they are excavated. Archeological reports often compile artifacts through the features that are excavated, and these artifacts are often grouped into specific types. The reports then describe the shared characteristics of the artifacts, which are synthesized from the information of artifacts distributed at multiple points without explicit spatial information. Different phases represented culturally by different types of artifacts also do not have a clear geographic scope and are often presented as information tables. Other artifacts from the sites can reflect the environmental background and events that occurred during the site’s survival phase. The exact geospatial area where they impact is not clear, but it can be determined that such events are closely related to the space where the prehistoric site is located.

We also design six entities, namely, stoneware, potteryware, ironware, bronzeware, goldware, and jadeware, according to their material categories. They are designed to inherit the information of excavated artifacts. Under these circumstances, we design both different attributes for different artifacts and common attributes such as the age and cultural characteristics.

The environmental information of prehistoric sites specifically includes the paleoclimatic background, paleoflood events, and paleoseismic processes. These objects can be reflected through specific stratigraphic records and the physical and chemical properties of biological remains. Therefore, we design the entities “climate,” “flood,” and “earthquake” to inherit environmental information to better store the environmental events experienced by the prehistoric site.

Cultural periodization involves the cultural characteristics and temporal information of prehistoric sites revealed by archeological spatial entities. It serves as the basis for dating archeological sites and conducting comparative studies between sites. By considering the similarity and correlation of different cultures within a certain historical stage, we simplify, classify, and organize a large amount of complex data obtained from archeological excavations. Afterward, we divide the sites into different historical stages and cultural types on the basis of stratigraphic relationships. This process focuses on a comprehensive analysis of the types of cultures represented by unearthed features and the measurement results.

Consequently, there is a vertical chain of site-square unit-layer-feature-remain in prehistoric sites that runs through the entire process from field investigation to analysis of remains. Based on the ER, connections between archeological entities can be established, which is conducive to the comprehensive spatial analysis of different archeological objects. The specific ERs are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1.

Rectangles, ellipses, and diamonds represent entities, attributes, and relationships, respectively. Geometric shapes (points, lines, polygons) and grids marked with a "T" denote spatiotemporal entities. The model centers on the Site entity, integrating key entities including Square Unit, Feature, Stratigraphic Layer, Artifacts, Biological Remains, and Cultural Periodization, along with their spatiotemporal associations.

Attribute design

The attributes of entities are designed according to the content structure of archeological reports. They are combined with prehistoric site entities and mutual correlations, following the basic principles of database design. The designed attributes of the site entities are shown in Table 2. We uniquely determine the site entities through identifiers and load the site name information with common names and other names. Additionally, we express the cultural period in which a site is situated through an era and culture type; describe its spatial location concerning the province, city, district (or county); describe the location and coordinates of the center position; reflect its geometric features and morphology through the perimeter, area, average elevation and morphology; and record its preservation status to provide comprehensive and complete site information.

Square units are divided into different specifications and consist of three parts, specifically, the main parts, the partition beams, and the key columns. A square unit has a strict numbering form, which is written in the style “(Site Partition No.)+T+North-South No.+East-West No.” 42. The square unit number at the same site corresponds to its geographic location; thus, it is used as the only identifier for square units. Additionally, the geographic location of the southwest corner of the square unit can be deduced according to the coordinates of the base point of the excavation area and the square unit number. Partition beams are retained to draw the stratigraphic sections of square units, and the key columns combine the longitudinal and transverse partition beams. If the partition beams and key column prevent the overall understanding of the stratigraphic layers, then they can be opened or extended to form an expanded square after the profile is drawn, so it is also necessary to record this information about the square units. Its attribute design is shown in Table 3.

A stratigraphic layer is excavated from the profile of a square unit or a trial trench and demonstrated by stratigraphic sections. Different layers have different depths, thicknesses, and soil properties (composition, color, and texture). Therefore, they are designed as important attribute fields. Moreover, the age attribute for different layers is designed because excavated features from different layers can represent different ages. As an important graphic display of the stratigraphic layer, the profile is also added to it as an attribute. Its attribute design is shown in Table 4.

Features are excavated in square units and sometimes exist across square units. Their numbering is often sequential and is their only representation of information. The first letter of the number represents different types of features: H-ash pit; F-house foundation; M-tomb; G-trench; J-well; L-road; Y-kiln; Z-stove; and Q-wall42. Furthermore, the stratigraphic relationships of features, including the opening layer, upper layer, lower layer, and breaking layer, are important. The archeological report has flat and sectional drawings of some of the features, which can be stored as diagrams in the attributes. Its attribute design is shown in Table 5.

Artifact entities are designed with archeological typology methods to categorize excavated artifact individuals from aspects of their material, category, type, and model. The quantity, preservation status, and age of the indicated artifacts are recorded. The common attributes of the design are shown in Table 6. For individual artifacts, separate entities are designed to store spatial information and other specific information. In addition to the material, category, type, and model, their special forms, excavation locations, artifact diagrams, and other individualized information are designed. These design attributes are shown in Table 7.

For biological remains, the common attributes are designed, encompassing basic biological information (including the common name, scientific name, and the different parts and morphology of organisms), statistical information (including the weight of the remains, number of remains, and the percentage of the number and density of the excavation) and basic archeological information (including the excavation location, preservation status and era), as shown in Table 8. On this basis, three specific subtypes are further defined with customized attributes that support species and quantitative statistical analysis, namely, plant remains, animal remains, and human bone remains, as shown in Table 9. More in-depth and specific attributes of biological remains can also be designed according to actual research needs. This process should be combined with more biologically specific parameters.

The attributes of the other entities are designed as shown in Table 10.

Results

Construction of the case database

To verify the conceptual data model, it is necessary to go through the logical and physical data model stages. The logical data model transforms the conceptual model into structural components of either an object-oriented or a relational database, while the physical model implements the logical model based on a chosen DBMS.

In this study, Geodatabase is used to design a spatial archeological database of prehistoric sites. Geodatabase, as the physical data model, defines a generic model for geographic information, which supports various user- or application-specific models43. According to the designed conceptual data model of prehistoric sites, the entities and relationships in the conceptual model are converted to Geodatabase according to the definition of basic Geodatabase elements. Entities with geospatial features are converted to feature classes. Entities without geospatial features are converted to object classes. The relationships between entities are converted to relationship classes. The conversion results are shown in the supplementary file.

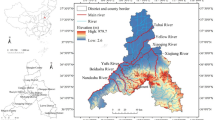

In this case, the archeological reports of the Baodun site are taken as an example. The Baodun site, which is located on the Chengdu Plain, southwest China, belongs to the Baodun culture stage (4.5–3.7 ka BP) of the Ancient Shu civilization44. Based on the conceptual data model and logical data model of prehistoric sites, case validation is combined with the parsing method of the archeological report. For data modeling, we use Geodatabase of ArcGIS Pro 3.0.0 to construct the spatiotemporal data model of the Baodun site. The model comprises 3 feature datasets, 20 feature classes, 12 object classes, 20 relationship classes, and a raster dataset. The structure is shown in Fig. 3.

Query and display of archeological information based on the spatial entity site-square unit-layer-feature

This case demonstrates the capability of the archeological spatial database designed according to the data model proposed in this study. This capability primarily involves the query and display of archeological information to verify the spatialized integration of multidisciplinary archeological information by this data model. The example data are selected to query the information of archeological spatial entities from macroscopic to microscopic inside the Baodun site, as shown in Fig. 4. During the internal study of a single prehistoric site, spatial entities such as sites, square units, layers, and features can be viewed for their attribute information. The associated excavated artifacts and other features can also be viewed for their basic information.

On the one hand, archeological entity information can be queried. After the entities identified in archeological reports are geographically aligned and vectorized, the prehistoric site elements in the case database are loaded into ArcGIS Pro, and the “attribute” tool is used to select the Baodun site on the map and identify the “site” elements, which can display the name of the prehistoric site, the era, the geographic scope and other basic attribute information, as shown in Fig. 4a. For the micro archeological units within the site, such as square units, layers and remains, their basic information described in the archeological report can also be queried through this method, as shown in Fig. 4b–d.

On the other hand, the objects associated with archeological entities can also be queried. According to the entity relations designed in this research, the detailed attributes of square unit elements such as IIIT1486 and IIIT1829 can be retrieved by querying square units within the Baodun site through the association among the entity fields, as shown in Fig. 5a. Querying the artifacts unearthed from the square unit in the attributes of the square unit displays the information and artifact diagrams of artifacts, such as the open-mouth, rounded-foot wine container (Zun) and the Corded Lace Jar (Guan). Through the interrelationships among the square unit, feature, and stratigraphic layer, the detailed attribute information of the related entities can be further queried. An example is shown in Fig. 5b.

Statistical analysis of excavated objects based on archeological units

This case demonstrates the spatial statistics ability of an archeological database and verifies that the data model proposed in this study can effectively support the quantitative analysis of data based on archeological reports and comprehensive research. Example data are selected from archeological units such as square units and probe holes in the excavation area of the Baodun site, and the spatial statistics of the excavation and exploration results are provided.

A statistical analysis of the stratigraphic deposition types is conducted based on probe holes. The vectorized data on the locations of the probe holes and their drilling results for the inner city of the Baodun site are selected as example data. According to the classification of the types of drilling results, we can obtain the distribution of cultural and environmental remains in the investigation area; this provides not only a reference for the formal selection of excavation sites and archeological work, but also basic background information for archeological research. An example is shown in Fig. 6. According to the distribution of the selected fluvial deposits (triangles) in the interface, the direction of an ancient river that no longer exists at the site can be inferred44, as indicated by the blue dashed line in the figure.

Black circles represent layers without unearthed artifacts, half-red and half-black circles represent cultural layers without unearthed artifacts, and red circles represent cultural layers with unearthed artifacts. Blue triangles represent fluvial deposits, black squares represent lacustrine deposits, and half-red and half-black squares represent lacustrine deposits with unearthed artifacts. The blue dashed line represents the ancient river flow direction inferred from the borehole data, which crosses the Baodun Site.

The artifacts and statistics are analyzed based on square units. The example data are selected from 9 square units (T1829-2229 and T1830-2130 in Area III of the 1996 fieldwork of the Baodun site) and the artifacts discussed in the archeological report. The attributes of the artifact entities are connected to square units, whose entities are symbolically displayed according to the total number of excavated artifacts, to obtain a statistical chart of the number of excavated artifacts in each square unit. As shown in Fig. 7a, the quantity of excavated artifacts in each square unit is demonstrated through the length of the bar chart. The excavated artifacts are classified according to the material, and because the excavated objects in the example data are only stoneware and pottery, the two types of artifacts are counted separately to obtain a statistical graph of the number of stoneware and pottery in the square units, which visualizes the comparison between the two. As shown in Fig. 7b, one dot in each square unit represents a piece of pottery, and one triangular dot represents a piece of stoneware.

Statistics of plant remains are analyzed based on features. Example data are selected to present the flotation results of rice seeds within the excavation areas of T1829-2229 and T1830-2130 in area III, on the basis of fieldwork in 2009. The different types of rice and their excavated features are summarized and symbolized to obtain a statistical chart of the flotation results of the rice seeds within the features, as shown in Fig. 8. The heights of the four columns from left to right represent the number of rice, immature rice, rice spikelets, and rice embryos.

Comparative analysis of different prehistoric sites from a spatial perspective

This case demonstrates the role of archeological spatiotemporal databases in the comparison of archeological information from prehistoric sites, and verifies that it can carry out spatial comparative studies. The Baodun site in Xinjin, Chengdu, and the Gaoshan site in Dayi, Chengdu, are used as examples45, and their basic information is compared as shown in Fig. 9. The following is a comparative analysis of the cultural types and periodization of the sites through typical artifact categories within the two sites. In terms of morphological characteristics, the shapes and sizes of the two sites can be visually compared. Additionally, through attribute tables, comparisons can be made between the two sites in terms of three aspects: basic information, geographical location, and archeological features. Therefore, we can conclude that the Baodun site and Gaoshan site are approximately located at the same latitude and elevation and belong to the same cultural stage; the Baodun site has a larger area than that of the Gaoshan site, while the preservation conditions of the Gaoshan site are relatively better.

Through the correlations between the sites and their internal entities, the types of the same artifacts from the two sites can be compared. As shown in Fig. 10, examining the attributes of the two ceramic wine containers (Zun) artifacts excavated from different sites (Baodun T1929⑦:128 and Gaoshan H21③:7), their basic information can be compared with the pictures of the artifacts. Additionally, through archeological typology, it can be determined that the two are close to each other in form with similar patterns, and that they should belong to the same cultural type of artifacts. Through this method, typological comparisons between many artifacts can be performed, combined with comparisons of the relationships between artifacts and layers. It can be inferred from such a comparison that the remains of ash pits such as H21 and H23, which are located under the 4th layer of the 2014 fieldwork at the Gaoshan site, should be similar in age to those of the 7th layer of the Baodun site. Moreover, the 7th layer of the Baodun site belongs to Phase I of the Baodun culture44; thus, the connections between layers can be used to determine the correlations between cultural phases.

After the cultural phasing correlation between the layers of different sites is established, the tomb M3 and other features in the Gaoshan site are found to be superimposed under the 5th layer through the stratigraphic relationship, and that its stratigraphic age may be slightly earlier than Phase I of the Baodun culture, as represented by the 3rd layer of the Baodun site (Fig. 11). These results further support archeologists’ speculation and suggest that the formation age of the Gaoshan site is slightly earlier than Phase I of the Baodun culture represented at the Baodun site45.

Discussions

To enhance the digital representation and analytical capabilities of archeological data, this study proposes a spatiotemporal data model based on a five-dimensional space-time architecture: site-square unit-layer-feature-cultural periodization. By systematically extracting and structuring data from prehistoric sites, this model establishes reliable ERs and attributes within the data architecture and addresses limitations in existing archeological databases. Its development and validation are grounded in the norms and methods of Chinese field archeology. Through an analysis of the reports in China, spatial and descriptive information—such as the geographic locations of square units, stratigraphic layers, and features and details regarding the location, characteristics, and quantity of remains—is extracted and organized. This enables the constructed database to support spatial entity query and visualization, statistical analysis of artifacts, and comparative studies across sites.

A case database developed through this model effectively supports statistical and comparative analyses of sites from the Baodun culture, thereby providing a solid foundation for spatially oriented, multidisciplinary archeological research. The advantages of the data model are reflected in the following aspects.

The first is its technical advantages. Core archeological entities are included in the model to ensure the systematic organization of archeological data. The entity attributes are comprehensively designed and fully consider the spatial, temporal, and cultural dimensions of the archeological entities. Moreover, the ERs are comprehensive and fully reflect the spatial and temporal relationships of archeological entities.

Additionally, there are several application advantages. The spatialization of archeological entities makes it more convenient to carry out spatial analysis in archeological research, supporting a GIS-based visualization and analysis of spatial patterns. The comprehensive integration of multidisciplinary archeological information around archeology makes it more efficient to store and manage archeological data, which assists in further advances in archeological research with complex relationships. Furthermore, the data model enables spatial statistical analysis of archeological remains at both intra-site and inter-site levels and facilitates comparative studies of the characteristics of artifacts and remains across multiple sites. Therefore, it provides an effective spatial and quantitative perspective for comprehensive research between different prehistoric sites.

Because of limited research time and insufficient data, there are limitations of this study that need to be further discussed.

First, considering the complexity of the actual relationships between stratigraphic entities and other entities, the treatment of stratigraphic data in this study is presented mainly in two-dimensional form, whose relationships with square units, features, and remains are reasonably abstracted. The discussion of the three-dimensional stratigraphic profile depends on the results of large-scale excavation and exploration, so its realization is more complicated and is a follow-up research direction.

Moreover, the entity design of biological remains in the data model mainly serves the statistical analysis of the remains at the spatial level. For the further study of specific biological remains, it is also necessary to integrate specialized archaeometric information according to the characteristics of specific research objects and design specific relationships with the data model proposed in this paper to connect and improve the application of this model in archaeometric research.

Finally, the data model is intended primarily for the digital and spatial structuring of information in archeological reports, with the goal of enhancing the capacity for a quantitative analysis of archeological excavation. Given the significant demand for the digital integration of archeological reports among research institutions, the model can serve as a guide to digitize and integrate reports and to establish spatial databases. As an infrastructure, it enhances the management and re-analysis of archeological reports. In the future, the model can be further adapted to align with the basic workflow of field archeology by developing business-oriented databases for excavation sites, thereby enabling the timely entry of archeological information, structuring digital information from the beginning, and laying a digital foundation for subsequent research and applications. In addition, the system for automatically generating archeological reports based on a business-oriented database needs to be studied further.

Data availability

All of the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supplementary files.

References

Smith, M. E., Feinman, G. M., Drennan, R. D., Earle, T. & Morris, I. Archaeology as a social science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7617–7621 (2012).

Rick, T. C. & Sandweiss, D. H. Archaeology, climate, and global change in the Age of Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 8250–8253 (2020).

Yang, L., Li, H., Zhang, S., Zhao, Y. & Sheng, Y. Cultural evolution of Neolithic archaeology in the Taihu Lake region of China based on complex network model. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 117 (2025).

Kintigh, K. W. et al. Grand challenges for archaeology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 879–880 (2014).

Mekonnen, H., Bires, Z. & Berhanu, K. Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Herit. Sci. 10, 172 (2022).

Nastou, M. P. P. & Zerefos, S. C. Effects of climate change on open air heritage: a review and the situation in the region of Mediterranean. Herit. Sci. 12, 367 (2024).

Di Angelo, L., Di Stefano, P., Guardiani, E. & Morabito, A. E. A 3D informational database for automatic archiving of archaeological pottery finds. Sensors 21, 978 (2021).

Ossa, A. & Simon, A. Basic Archaeological Database Design (Archaeological Research Institute, Arizona State University, 2010).

McManamon, F. P., Kintigh, K. W., Ellison, L. A. & Brin, A. tDAR: a cultural heritage archive for twenty-first-century public outreach, research, and resource management. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 5, 238–249 (2017).

Sobotkova, A. Sociotechnical obstacles to archaeological data reuse. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 6, 117–124 (2018).

Yu, C. Application of relational database model in zooarchaeology. Archaeology 60, 102–107 (2015). (in Chinese).

Hein, A. & Kilikoglou, V. ceraDAT—prototype of a web-based relational database for archaeological ceramics. Archaeometry 54, 230–243 (2012).

Smith, N. G. et al. The pottery informatics query database: a new method for mathematic and quantitative analyses of large regional ceramic datasets. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 21, 212–250 (2014).

Morrison, A. E., Rieth, T. M., Cochrane, E. E. & DiNapoli, R. J. The Samoa archaeological geospatial database: initial description and application to settlement pattern studies in the Samoan Islands. J. Polyn. Soc. 127, 15–34 (2018).

Savage, S. H. & Levy, T. The Mediterranean archaeological network–a cyberinfrastructure for archaeological heritage management. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 14, 135–135 (2014).

Yang, H. Research on Spatio-Temporal Data Model of Prehistoric Settlement Sites: The Case of Zhengzhou-Luoyang Area Master’s thesis, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology (2015) (in Chinese).

City of York Council. Archaeological monuments around the city of York. https://www.data.gov.uk/dataset/69634554-b596-43d2-9c49-bd8138757f72/archaeological-monuments (2025).

Jiao, J., Xie, Y., Ma, Z. & Shi, J. Construction of National Earthen Site Information System Database by GIS. In Proc. Second Workshop on Digital Media and Its Application in Museum & Heritages (DMAMH 2007) 427–431 (IEEE, 2007).

Jin, X. et al. Design and implement of a spatial database based on ArcGIS Geodatabase for archaeological sites in Liangzhu ancient city, Zhejiang Province. J. Nanjing Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 54, 163–175 (2018). (in Chinese).

Gergatsoulis, M., Papaioannou, G., Kalogeros, E. & Carter, R. Representing archeological excavations using the CIDOC CRM based conceptual models. in Metadata and Semantic Research (eds. Garoufallou, E. & Ovalle-Perandones, M.-A.) 355–366 (Springer, 2021).

CIDOC CRM. Conceptual Reference Model. https://cidoc-crm.org (2024).

Meghini, C. et al. ARIADNE: A research infrastructure for archaeology. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 10, 1–27 (2017).

Hiebel, G., Doerr, M. & Eide, Ø CRMgeo: a spatiotemporal extension of CIDOC-CRM. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 18, 271–279 (2017).

Rahtz, S., Carr, L. & Hall, W. New designs for archaeological reports. Sci. Archaeol. 31, 20–34 (1990).

Patrik, L. E. Is there an archaeological record? Adv. Archaeol. Method Theory 8, 27–62 (1985).

Day, J. Botany meets archaeology: people and plants in the past. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 5805–5816 (2013).

de Vareilles, A., Pelling, R., Woodbridge, J. & Fyfe, R. Archaeology and agriculture: plants, people, and past land-use. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 943–954 (2021).

Hamilakis, Y. Archaeological ethnography: a multitemporal meeting ground for archaeology and anthropology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 40, 399–414 (2011).

Huvila, I., Sköld, O. & Börjesson, L. Documenting information making in archaeological field reports. J. Doc. 77, 1107–1127 (2021).

Wright, P. J. Flotation samples and some paleoethnobotanical implications. J. Archaeol. Sci. 32, 19–26 (2005).

Gorham, L. D. & Bryant, V. M. Pollen, phytoliths, and other microscopic plant remains in underwater archaeology. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 30, 282–298 (2001).

Miller, N. F. The Analysis of Archaeological Plant Remains (Simon and Schuster, 1997).

Yao, X., Zhao, F., Hao, J., Wang, Y. & Hu, R. Plant investigation and the impact on earthen site soil properties in the east city wall of the Sanxingdui site. Herit. Sci. 12, 339 (2024).

Zhang, J. & Xu, H. Application of plant microfossil in Quaternary environmental research: a review and perspective. J. Earth Environ. 7, 238–253 (2016). (in Chinese).

Lyman, R. L. Observations on the history of zooarchaeological quantitative units: Why NISP, then MNI, then NISP again? J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 18, 43–50 (2018).

Boyd, B. Archaeology and human-animal relations: thinking through anthropocentrism. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 46, 299–316 (2017).

Ning, C. et al. Ancient genomes from northern China suggest links between subsistence changes and human migration. Nat. Commun. 11, 2700 (2020).

Ambrose, S. H. & Krigbaum, J. Bone chemistry and bioarchaeology. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 22, 193–199 (2003).

Davies, M. The application of the Harris Matrix to the recording of standing structures. in Practices of Archaeological Stratigraphy (eds Harris, E. C., Brown III, M. R. & Brown, G. J.) 167–180 (Academic Press, 1993).

Banning, E. B. Sampled to death? The rise and fall of probability sampling in archaeology. Am. Antiq. 86, 43–60 (2021).

Kowalewski, S. A. Regional settlement pattern studies. J. Archaeol. Res. 16, 225–285 (2008).

National Cultural Heritage Administration. Field Archaeology Work Regulations (Cultural Relics Press, 2009) (in Chinese).

Shi, J. et al. A scene-based spatiotemporal data model of immovable cultural relics. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 1–14 (2025).

Jiang, Z., Wang, Y. & Zhang, Q. An initial study of early urban sites and their archaeological cultures in the Chengdu Plain. Chengdu Archaeol. Res. 1, 63–87 (2009). (in Chinese).

Liu, X., Zhou, Z. & Chen, J. 2014 excavation report of Gaoshan Ancient City, Dayi County, Chengdu. Archaeology 63, 3–13 (2017). (in Chinese).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42271423) and the Open Fund of the Key Laboratory of Virtual Geographic Environment, Ministry of Education, China (2023VGE04 and 2023VGE06). The authors also want to acknowledge Zongxiang Zhang and Fangheng Xie, who contributed their time and knowledge to ensure the success of the described activities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. designed the data model, carried out the experimental verification, and wrote the article. Y.L. helped carry out the experiments and wrote the article. D.H. designed the study and wrote the draft. J.S. and G.L. provided some guidance for the article. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, T., Li, Y., Hu, D. et al. A data model for the spatialized integration of archaeological excavation information from prehistoric sites. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 45 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02316-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02316-x