Abstract

Background

Targeting intracellular lipolysis represents a therapeutic potential for treating metabolic disorders such as obesity. Interleukin (IL)-33 has been shown to exert anti-obesity effects by reducing inflammation and restricting adipocyte hypertrophy.

Methods

In this study, male mice on a high-fat diet (HFD) were treated with IL-33 once every 2 days for 2 weeks. 3T3-L1 cells were treated with IL-33 to verify the down-stream effect of β1-AR activation on the adipose cells.

Results

IL-33 treatment led to a reduction in adipose tissue mass and a decreased in lipid deposition in male mice with obesity, accompanied by activation of β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) signals. Immunostaining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) revealed an increase of TH within the adipose tissue in male mice. Metabolomic analysis showed that IL-33 induced a distinct metabolic profile in differentiated adipocytes, with significant changes in metabolites related to lipolysis pathways. Supplementation with β1-AR inhibitor significantly inhibited IL-33-induced p-HSL and p-PKA activation. Compared to IL-33 alone, β1-AR inhibitor reduced glycerol release and increased accumulation of lipid droplets. We also illustrated the fatty acids (FAs) process by tracking FA trafficking, and found that the labeled FA localized lipid droplets (LDs) in mature adipocytes but shifted from LDs to mitochondria at 20 ng/mL IL-33.

Conclusion

We summarized that IL-33 regulated mature adipocyte metabolism and enhanced lipolysis in male mice via activation of the β-AR/cAMP/PKA/HSL signaling pathway. However, given that sex is a significant determinant in obesity, future studies should investigate potential sex-specific effects of IL-33 in metabolic regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is the most prevalent chronic disease, representing a major public health problem and economic burden [1]. Obesity causes a disturbance in metabolic homeostasis and inflammatory-immune response, which has been associated with several major chronic illnesses such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, mental illnesses, and inflammatory diseases [2,3,4]. More importantly, growing evidence demonstrates that obesity increases the risk of developing several types of cancer, and complicates their management, contributing to global morbidity and mortality [5].

The white adipose tissues (WAT), as a multifactorial organ, play an essential role for energy storage and hormone-producing under physiological conditions [6]. WAT is largely composed of adipocytes, and many other cell types including immune cells, endothelial cells, and mesenchymal cells in both mice and humans [7, 8]. The dynamic crosstalk between these different cell types is necessary for whole-body metabolic homeostasis [7, 9]. During obesity, WAT expands inappropriately to store the surplus energy by an increase in adipocyte numbers (hyperplasia) and/or an enlargement of adipocyte size (hypertrophy) [10]. Adipocyte hypertrophy results in lipid-engorged dysfunctional cells. These contribute to numerous deleterious consequences, including dysregulated secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and hormones, as well as fibrosis, hypoxia, and impaired mitochondrial function [11]. Adipocyte, approximately dominating one third of the cells within adipose tissue, may represent a promising therapeutic avenue.

Interleukin (IL)-33, a member of the IL-1 family of cytokines, has been associated with preventing the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes. In adipose tissues, IL-33 is primarily produced by specialized mesenchymal cells and exerts its protective effect via inducing a type 2 immune microenvironment [12]. IL-33 promotes expansion of type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) within adipose tissue to limit obesity [13,14,15,16]. ILC2s enhance the expression of UCP-1 in WAT and, promoting WAT browning, thereby ameliorating the obesity state [17]. Moreover, IL-33 contributes to the polarization of macrophages towards an M2 alternatively activated phenotype with reduced adipose mass and fasting glucose [18].

In addition to a role of anti-inflammatory effects by acting on immune cells within adipose tissues, studies also show IL-33 is a direct player in adipocytes, by inhibiting the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells into mature adipocytes [19,20,21]. IL-33 stimulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and fatty acid receptors [22], while decreases the expression of adipogenic factors acetyl- CoA synthetase 1 (AceCS1) and PPARγ [20], and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) [23] in 3T3-L1 cells. These findings highlight the importance of IL-33 in adipocytes. Unlike IL-33 for immune cells, detailed mechanism of IL-33 on adipocytes remains poorly understood, especially in the context of lipid metabolism in mature adipocytes.

Adipocyte lipolysis contributes to the degradation of cellular lipid stores, by converting triacylglycerol (TG) to diacylglycerol (DG), and monoacylglycerol (MG), generating glycerol and fatty acids (FAs) [24]. These processes are catalyzed by adipose triglyceride lipase, hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), and monoglyceride lipase (MGL), respectively [25]. Targeting lipolysis within adipocytes represents a therapeutic opportunity for the treatment of metabolic diseases. In this study, we show that IL-33 has clear effect of initiating triglyceride lipolysis in adipocytes to limit obesity. IL-33 increased distribution of sympathetic neurons, with a dramatic increase expression of β1-adrenergic receptor (AR) in adipose tissues. β1-AR-mediated PKA activity results in HSL phosphorylation at Ser 563, which participates the effect of IL-33 on adipocytes to suppress glycerol release and lipid droplet accumulation. Upon lipolysis, IL-33 promotes FAs transfer from lipid droplet (LD) organelles to mitochondria, which in turn regulates adipose tissue mass and attenuates lipid deposition and prevents obesity in mice.

Methods and materials

Animals and experimental treatment

Male C57BL/6 mice (3–4 weeks old) were purchased from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Ethical approval for all animal experiments was obtained from the Research and Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of the Experimental Animal Platform, School of Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University (Permit Number: ZZU-LAC20230310[11]). The mice were randomly assigned to one of three groups: the normal diet group (ND), the high-fat diet group (HFD), and the HFD+IL-33 treatment group (IL-33) (n = 6 samples/group). The ND group was fed with a chow diet for 13 weeks. The HFD and IL-33 groups were both fed with a high-fat diet of 60% kcal (Research Diets, USA) for 13 weeks (compared to the control group, HFD group exhibited a ≥20% increase in body weight), and were intraperitoneally treated with sterile PBS or 500 ng IL-33 (BioLegend) once every 2 days for 2 weeks. Experimental mice were kept in the specific pathogen-free barrier facility with 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. The ambient temperature was 22–26 °C and the relative humidity was 50–70%. Body weight was measured once every 2 days during the treatment period.

Cell differentiation and treatment

The 3T3-L1 mouse embryonic fibroblast (preadipocyte) cell line was obtained from QuiCell (QuiCell-T105, QuiCell Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). The cells were maintained and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (G4511, Servicebio, Wuhan, China), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (A6901FBS, Invigentech, Irvine, CA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (G4003, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation was induced by adding a cocktail containing 10 mg/ml insulin (TP1125, tsbiochem, shanghai, China), 5 μM dexamethasone (T1076, tsbiochem, shanghai, China), and 0.5 mM 1-methyl-3-isobutylxanthine (HY-12318, MCE, shanghai, China) for 4 days. Then the cocktail was replaced by a medium containing only 10 mg/ml insulin. After 4 days, differentiated 3T3-L1 cells were cultured exclusively in DMEM with 10% FBS. To analyze the effect of IL-33 on the lipid synthesis, differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with 5, 20, 40, 60 or 80 ng/mL recombinant IL-33 (580504, Biolegend, San Diego, US). Then, the cells and supernatants were collected for further experiments.

To investigate the impact of IL-33 on the release of norepinephrine (NE) in RAW264.7 cells (Purchased from QuiCell Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The cells were treated with recombinant IL-33 at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, or 100 ng/mL (580504, Biolegend, San Diego, USA). Following the treatments, Supernatants were collected for analysis and added to differentiated 3T3-L1 cells to analyze changes in metabolic gene expression.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF)

Epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) was fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and then embedded in paraffin for tissue sectioning. The slides underwent antigen retrieval in 10 mM sodium citrate with 0.05% Tween-20 (pH 6.0) at 95–100 °C, then cooled to room temperature and blocked. The slides were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-Phospho-HSL(Ser563) (hormone-sensitive lipase) (1:200), anti-HSL (hormone-sensitive lipase) (1:200), and anti-beta 1 adrenergic receptor (β1-AR) (1:200) (Affinity, Jiangsu, China); anti-adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) (1:2000) (Abcam, Boston, USA), anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody (1:200) (Affinity, Jiangsu, China). The slides were then washed three times with TBS and 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST). After washing, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies. For IHC, the slides were scanned with panoramic slide scanner (GScan-20, Guangzhou, China). The average optical density was measured using ImageJ. For IF, the cell nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (G1407, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) for 3 min. Fluorescent images were captured using a Pannoramic SCAN (3DHISTECH, Hungary).

Oil red O staining

For morphological determination of cell lipid content, 3T3-L1 cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Then, cells were washed with 60% isopropanol for 20 s and stained with 60% oil red O (G1015, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) solution for 30 min in the dark. Lipid droplet morphology was observed under a microscope after washing these cells three times.

Western blot

RIPA buffer (G2002, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) containing 1 mM PMSF (ST2573, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (P-1260, Solarbio, Beijing, China) was used to extract total proteins from the cells and tissues. Isolated total proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (PG212, Epizyme, Shanghai, China) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (IPVH00010-J, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk for 2 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following specific primary antibodies: anti-β1-AR (1:1000), anti-Phospho-HSL(Ser563) (1:1000), anti-HSL (1:2000), anti-PKA (1:5000), anti-fatty acids binding protein-4 (FABP4) (1:1000) (Affinity, Jiangsu, China), anti-β-actin (1:5000) (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and anti-PKA p-T197 (1:5000) (Abcam, Boston, USA). Then these bands were incubated with the secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. The target bands were analyzed with ImageJ software after imaging with Amersham Imager 600. ImageJ software was used to quantify the band intensities.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated with the GeneJET RNA Purification Kit (K0731; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using the TAKARA Reverse Transcription Kit (RR047A; TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was conducted using SYBR-green on a Thermo QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Relative fold induction was determined via the ΔΔCt method, using β-actin as the reference gene. The primer sequences used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Glycerol release assay

Mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes were exposed to IL-33 for 24 h. For pharmacological inhibition experiments, cells were pre-incubated with CGP 20712A for 1 h prior to IL-33 treatment. At the conclusion of each experiment, the media from each well were collected to measure free glycerol levels using the Glycerol Assay Kit (S0223S, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China, or F005-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) following the supplier’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence and BODIPY staining of mature 3T3-L1 adipocyte

Mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes were incubated overnight in complete medium (DMEM with 10% FBS and 4 mM glutamine, CM) containing 1 μM BODIPY 558/568 C12 (Red C12, Life Technologies). The cells were then washed three times with CM and incubated for 1 h to allow fluorescent lipids to incorporate into LDs, followed by a 24-h chase in CM containing IL-33. Mitochondria were stained with 150 nM MitoTracker Green FM (40743ES50, Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for 30 min prior to imaging. To stain LDs, BODIPY 493/503 (C250S, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was added to the cells for 30 min before imaging, and Fluorescence imaging was conducted using an Olympus microscope (Olympus DP74, Tokyo, Japan).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay

Epididymal adipose tissue extracts were centrifuged (MX-200, TOMY Seiko Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 1000 × g for 10 min, and the diluted supernatant was utilized for the assay. Intracellular cAMP levels were determined using a Cyclic AMP ELISA Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentrations of norepinephrine (NE) in the culture supernatants were measured using the mouse NE ELISA Kit (EU2565, Fine Test, Wuhan, China).

Metabolomics

To evaluate metabolite levels in mature adipocytes under IL-33 treatment, differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were exposed to IL-33 for 24 h. Cells were extracted with a methanol:water solution (4:1, V/V) containing an internal standard. The sample underwent vortexing, freeze-thaw cycles, and centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, stored at −20 °C for 30 min, and centrifuged again. A 200 μL aliquot was analyzed by LC-MS under positive ion mode using a T3 column. The mass spectrometer operated in positive and negative ion modes, scanning m/z 75–1000 at 35,000 resolutions. Data were processed using XCMS, and metabolites were identified using a database from Frasergen Bioinformatics Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China).

Prediction of protein–protein docking model

Protein–protein docking was performed with the PyMol. The protein structures of IL-33 and β1-AR were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org). In the protein–protein docking calculation using PyMol, the final model selection for IL-33 and β1-AR involved choosing the model where K265, S119 of IL-33 and H180, W181, R193 of β1-AR were predicted to interact.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

The IP experiment was performed using the Vazyme Co-IP kit(PB201-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, Cell lysates from 1 × 106 cells were prepared using Lysis/Wash buffer. Supernatants were collected after lysis and centrifugation for use. A total of 500 μg of lysate was mixed with 6 μg of IL-33 antibody in 500 μL Lysis/Wash buffer. Samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature on a rotator. A total of 500 μL of antigen-antibody complex was added to magnetic beads and incubated for 30 min at room temperature on a rotator. Proteins were eluted using 5× loading buffer at 95 °C for 5 min. Western Blot will be performed for anti-β1-AR.

Statistical analysis

All study data were analyzed and visualized using GraphPad Prism Version 8.1 (GraphPad Software, CA). Results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. Differences were primarily evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

IL-33 decreases adipose tissue mass and attenuates lipid deposition in mice with obesity

To directly investigate the effect of IL-33 on obesity, mice were fed with a HFD to induce obesity, and then treated with PBS or recombinant IL-33 for 2 weeks. Consistent with previous reports, HFD-fed mice exhibited significantly greater body weight gain compared to those fed a normal chow diet (Supplementary Fig. 1A). There was an apparent decrease in the final body weight of HFD-fed mice after treatment with IL-33 (Fig. 1A). The eWAT weight was reduced in IL-33-treated HFD-fed mice (Fig. 1B). In addition, H&E staining and imaging showed that IL-33 treatment significantly resulted in a smaller WAT adipocyte size than that in HFD-fed mice (Fig.1C, D).

A The change of bodyweight after IL-33-treatment 2 weeks. B The weight of extracting eWAT in different groups (n = 6 samples/group). C Representative adipocytes of H&E-stained WAT sections (n = 3 samples/group; scale bar: 100 μm). D Adipocyte size was measured using ImageJ software (n = 3 samples/group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

Phosphorylation of HSL in WAT as a lipolysis marker for IL-33 action

To detect the effect of IL-33 on lipid metabolism, we detected the expression of main lipases including ATGL and HSL, the key player in the regulation of lipolysis in WAT. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, although there was a significant decrease in both ATGL and HSL mRNA levels, IL-33 did not alter the expression level of total protein ATGL and HSL (Fig. 2C). However, IL-33 treatment upregulated the phosphorylation of HSL at Ser563 in eWAT, which were confirmed by both IHC and IF method (Fig. 2C, D). These data demonstrated that IL-33 might regulate lipid mobilization by promoting lipolysis in adipose tissues.

A, B RT-qPCR analysis showing ATGL and HSL levels in eWAT (n = 3 samples/group). C Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of ATGL, HSL and phospho-HSL(Ser563), and immunostaining for the phospho-HSL(Ser563) (n = 3 samples/group; scale bar: 200 μm). D Quantification of ATGL, HSL and Phospho-HSL(Ser563) was measured by integrated optical density (IOD) and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) with ImageJ software. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

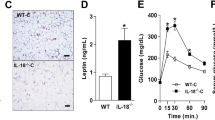

IL-33 activates β1-adrenergic receptor in adipose tissues of mice with obesity

It is well known that the primary regulator of adipose lipolysis is the sympathetic nervous system through the activation of β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs), which results in the production of second messenger cyclic AMP (cAMP) from adenosine triphosphate to activate lipases [26, 27]. To investigate the effects of IL-33 on sympathetic activity in adipose tissue, we first performed TH immunostaining to analyze sympathetic axon bundles in eWAT. IL-33 treatment markedly increased the density of sympathetic nerve fibers in eWAT (Fig. 3A, B), with concurrent upregulation of TH mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 3C–E). Consistently, we found that IL-33 enhanced the mRNA and protein levels of β1-AR (Fig. 3F–H), while showing no significant effect on β2-AR or β3-AR. Further analysis revealed that IL-33 significantly elevated intracellular cAMP levels in adipocytes (Fig. 3I). These findings suggest that IL-33 selectively amplifies β1-AR expression in eWAT and activates the sympathetic-adrenergic signaling axis by increasing sympathetic innervation in adipose tissues.

A Epididymal WAT was subjected to immunostaining for the TH (n = 3 samples/group; scale bar: 100 μm). Compared with the HFD group, IL-33-treated mice show significantly higher sympathetic nerve density. B The numbers of sympathetic neurons were analyzed by ImageJ software. C–E RT-qPCR and western blot analysis showing the TH levels in eWAT after IL-33 treatment. (n = 3 samples/group). F Expression of β1/β2/β3-AR genes, and G representative images of immunohistochemical staining of β1-AR (n = 3 samples/group; scale bar: 200 μm). H β1-AR was measured by integrated optical density (IOD) with ImageJ software. I cAMP concentrations in eWAT were measured by ELISA Kit (n = 3 samples/group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

Metabolomic analysis of mature adipocytes after treated with IL-33

We examined potential changes in the metabolite profiles of mature adipocytes induced by IL-33. Principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and heat map analysis all revealed a clear separation between the IL-33 group and the control group (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B), suggesting that IL-33 induced a distinct metabolic profile in differentiated adipocytes. In the metabolomic analysis, 1976 metabolites were analyzed. Among them, the levels of 44 metabolites were increased and 297 metabolites were decreased in IL-33-treated mature adipocytes, compared with control group (Supplementary Fig. 2C, D). The differences and dynamic changes in biological process were examined using metabolomics pathway analysis based on KEGG. As expected, IL-33 affected the pathways related to lipid metabolism and energy metabolism, including glycerophospholipid metabolism, fat digestion and absorption, regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes, thermogenesis, sphingolipid metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, glycerolipid metabolism, sphingolipid signaling pathway, arachidonic acid metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 2E). With regard to lipolysis pathway, heat map analysis showed that IL-33 affected the amount of TG, DG, MG and FFA (Supplementary Fig. 2F). In particular, most lipid metabolites such as 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), 12-hydroxysteric acid were downregulated by IL-33, whereas FFA (16:1) and DG (20:4) were upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 3).

IL-33 promotes β1-AR-mediated PKA activities and lipolysis in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes

To confirm the role of β1-AR signals in IL-33-induced lipolysis, we treated differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes with IL-33 for 24 h. We find that IL-33 promoted β1-AR expression, and 20 ng/mL IL-33 induced the greatest effect (Fig. 4A, B). Consistent with the in vivo results, 20 ng/mL IL-33 increased the phosphorylation of HSL at Ser563. Since HSL phosphorylation is regulated by p-PKA, we measured p-PKA levels and found that IL-33 increased them (Fig. 4C, D). Consequently, IL-33 treatment inhibited lipid droplet accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, treatment with IL-33 increased the release of glycerol in the medium, an index of lipolysis and HSL activities (Fig. 4F).

A Western blot analysis slowing protein expression of β1-AR in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes (n = 3 samples/group). B β1-AR quantification was statistically analyzed using ImageJ. C, D Protein expression of phospho-PKA substrates, PKA, phospho-HSL(Ser563), and β-actin measured in 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with IL-33 (0, 5, 20, 40, 60, and 80 ng/ml) for 24 h (n = 3 samples/group). E Representative images of Oil Red O staining were collected using an inverted microscope (n = 3 samples/group; scale bar: 100 μm). F Glycerol in the 3T3-L1 adipocyte medium were measured by ELISA Kit (n = 3 samples/group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

β-Adrenergic signal is required for IL-33-stimulated lipolysis

Although of β1-AR was increased in protein level, there was no significant difference in mRNA level after IL-33 treatment (Fig. 5A). The docking results showed that IL-33 has a strong binding affinity to β1-AR via hydrogen bonding (Fig. 5B). Next, we performed IP assays to examine the interaction between IL-33 protein and β1-AR in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells. As shown in Fig. 5C, β1-AR levels were increased compared to control. Next, we examined whether effects of β1-AR signals are required for IL-33-mediated lipolysis by pretreatment with β1-AR inhibitor CGP 20712A for 1 h. IL-33 treatment significantly increased expression of phospho-HSL and phospho-PKA substrate, whereas supplementation with β1-AR inhibitor significantly inhibited IL-33-induced effects (Fig. 5D, E). Compared to IL-33 alone, supplementation of β1-AR inhibitor also altered glycerol release and significantly suppressed accumulation of lipid droplets (Fig. 5F, G).

A mRNA analysis showing β1-AR levels in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes with different dose treatment (n = 3 samples/group). B Model of IL-33 binding to β1-AR. C Co-immunoprecipitation of IL-33 with β1-AR was performed after 24 h of IL-33 treatment. D, E Western blot analysis showing the phosphorylation of PKA substrates, PKA and phospho-HSL(Ser563). F Representative images of Oil Red O staining were collected using an inverted microscope (n = 3 samples/group; scale bar: 100 μm). G Glycerol in the 3T3-L1 adipocyte medium were measured by ELISA Kit (n = 3 samples/group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

IL-33 increases FA transfer from lipid droplet organelles to mitochondria

Under lipolysis, mobilizing FAs stored in LDs transfer into mitochondria for driving FA oxidation or extracellular for use by other organs as energy substrates [24]. To understand how this process was regulated by IL-33, we used a pulse-chase assay to visualize FAs movement between organelles in mature 3T3-L1 adipocyte. In our pulse-chase assay, cells were first labeled overnight with 1 μM of Red C12, a fluorescent fatty acid analog, which initially accumulated in neutral lipids within LDs. Cells were then placed in complete medium in the absence of Red C12 which had 20 ng/ml IL-33 for 24 h and then labeled LDs with BODIPY 493/503 or mitochondria with MitoTracker Green FM, respectively. Fluorescence in the cells was visualized with spinning-disk confocal microscopy.

Cells in control groups showed nearly all Red C12 signals localized within LDs throughout the pulse-chase labeling period. Continued incubation in complete medium with IL-33 resulted in a dramatic loss of Red C12 signal within LDs (Fig. 6A, B). And FABP4, a carrier protein mediating lipid droplet formation, was reduced by IL-33 treatment. Compared to IL-33 alone, supplementation of β1-AR inhibitor increased the expression of FABP4 (Fig. 6E, F). In response to IL-33 treatment, an accumulation of Red C12 intensity within the mitochondrial was observed, suggesting the signal redistributing into mitochondria (Fig. 6C, D).

Cells were pulsed with Red C12 overnight, washed, and incubated with CM for 1 h in order to allow the Red C12 to accumulate in LDs. Cells were pre-incubated with CGP 20712A for 1 h prior to IL-33 treatment. A LDs were labeled using BODIPY 493/503. (n = 3 samples/group; Scale bar: 10 μm). B Relative cellular localization of Red C12 was quantified by ImageJ. C Mitochondria were labeled using MitoTracker Green. (n = 3 samples/group; Scale bar: 10 μm). D Relative cellular localization of Red C12 was quantified by Pearson’s coefficient analysis to analyze the colocalization of mitochondria and free fatty acids. E Western blot analysis showing the expression of FABP4 (n = 3 samples/group). F FABP4 quantification was statistically analyzed using ImageJ (n = 3 samples/group). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

Discussion

Studies have shown that IL-33 can promote preadipocyte proliferation, enhance the WAT browning and thermogenesis [12]. Additionally, IL-33 inhibits adipocyte hypertrophy by suppressing PPARγ and AceCS, thereby reducing lipid synthesis [20]. However, it remains unclear whether IL-33 affects lipolysis in mature adipocytes. In this study, we explored the effects of IL-33 on triglyceride lipolysis in mature adipocytes to provide new insights into the role of IL-33 in ameliorating obesity in mice. Our results revealed that IL-33 treatment resulted in smaller LD with higher release of glycerol in adipocytes, and smaller size of adipocytes in WAT that is resistant to HFD-induced obesity. Specifically, exogenous IL-33 activated HSL by promoting its phosphorylation at the Ser563 site, thereby initiating triglyceride lipolysis.

Metabolomic data further show that metabolites linked with energy metabolism and lipid metabolism were changed by IL-33 treatment. The intermediates detected in the lipolytic pathway, such as TG, DG, MG and FFA were significantly altered in mature adipocytes after IL-33 treatment. Notably, there are differential regulation of lipid metabolites observed in IL-33-treated adipocytes, characterized by the downregulation of MG (18:1), MG (16:0) and DG (18:3), alongside the upregulation of FFA (16:1), TG (14:1), and DG (20:4). Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-33 inhibits adipogenesis in adipocytes by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin/PPAR-γ signaling pathway [28]. Combined with our results, this may reflect a complex reprogramming of lipid metabolism in adipocytes by IL-33, balancing lipid storage with the activation of lipid mobilization and inhibition of adipogenesis.

We further sought to understand the mechanisms underlying IL-33-induced adipocyte lipolysis. Our vivo results revealed that IL-33 treatment resulted in smaller size of adipocytes in WAT that are resistant to HFD-induced obesity. This process was associated with β1-AR-mediated canonical cAMP-dependent PKA pathway after IL-33 treatment, which was crucial for HSL activity and lipolysis. In WAT, it is known local sympathetic innervation through β-ARs is essential for lipolysis in adipocytes [29,30,31]. Specifically, activated PKA phosphorylates HSL at three serine sites, which are necessary for translocation of HSL to lipid droplet [32]. We detected the sympathetic density in WAT, determined by labeling TH, a rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis. Consistent previous studies, local sympathetic nerve density of WAT was increased by IL-33 treatment in HFD-induced mice with obesity [33]. A study of intra-adipose axonal plasticity showed that IL-33 leads to sympathetic axonal outgrowth upon cold challenge [34]. In this process, IL-33 drives the ILC2s-induced IL-5 production, resulting in eosinophil proliferation [33, 34]. Eosinophils produce nerve growth factor (NGF), which acts locally to sympathetic nerves to promote intra-adipose axonal outgrowth, thus influencing the cold-induced beiging process [34]. In obesity, studies have revealed that IL-33 maintained normal ILC2 responses in WAT by metabolic regulation such as PPARγ and AMPK expression to limit the development of spontaneous obesity [17, 35, 36]. Unlike in cold challenge, how IL-33-induced ILC2s participates in the immune-neuron crosstalk to regulate adipocyte lipid metabolism is not studied in obesity.

In WAT, NE released by sympathetic adrenergic nerves is responsible for β1-AR-mediated cAMP-dependent PKA pathway in adipocytes. It has reported that anti-inflammatory adipose tissue macrophages produce NE to induce lipolysis in WAT [37]. Given that IL-33 could skew macrophages towards anti-inflammatory phenotype [18], we detected the release of NE by IL-33-treated macrophage in vitro. The results showed that IL-33 could stimulate the release of NE in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 4A). However, we observed there was no significant increase in Ucp1 and Pgc-1α expression (Supplementary Fig. 4B, C), when differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were cocultured with IL-33-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages, which was not consistent with the release of NE. Thus, we speculated that the NE released by macrophages is not sufficient to promote lipid metabolism in adipocytes.

Exogenous IL‑33 exerts its cytokine activity by interacting with the IL-1 family receptor ST2 (also known as IL‑1RL1) to activate the MyD88-dependent pathway [38]. However, RNA sequencing of preadipocytes revealed a low but detectable level of Il1rl1 (encoding ST2) [39, 40]. In vivo studies have shown that IL-33-induced thermogenesis in adipocytes does not depend on MyD88 [41]. These data suggested the direct effect of IL-33 on adipocytes might have alternative path, thereby explaining the low levels of Il1rl1 and the lack of dependence on MyD88. Interestingly, we found IL-33 could activate β1-AR-mediated cAMP-dependent PKA signals without NE stimulation in vitro, and blocking this receptor effectively inhibited the action of IL-33. This effect of IL-33 on β1-AR contributed to HSL activation and subsequently lipolysis. FAs released from LDs through lipolysis were subsequently transferred into mitochondria. The data together have revealed a previously unknown mechanism of IL-33 in promoting adipocyte lipolysis by involvement β1-AR-mediated cAMP-dependent PKA activity, although the mechanism by which IL-33 induces high β-AR expression remains unclear in vitro.

Mice in our study were maintained at standard room temperature (22–26 °C), below their thermoneutral zone, potentially forcing reliance on brown adipose tissue metabolism for thermoregulation [42]. This likely impairs adipose tissue sensitivity to IL-33, confounding lipolysis measurements through augmented cold-induced thermogenesis. Consequently, thermoneutral conditions—physiologically appropriate for mice—are essential for unbiased assessment of IL-33’s metabolic role. Further evaluation of IL-33’s impact on mice metabolism under thermoneutral conditions is required, particularly in adipose tissue.

In summary, we find a novel function for IL-33 in obesity by directly acting on adipocytes, a process that link to β1-AR-mediated cAMP-dependent PKA pathway for lipolysis. We first revealed the neuronal control in IL-33-mediated prevention of obesity, although future functional studies of sympathetic nerve to evaluate the role of IL-33 in adipocyte lipid metabolism are warranted. Notably, this study exclusively evaluated IL-33 in male mice. Given established sex differences in metabolic regulation where female mice are inherently more resistant to diet-induced obesity than males [42], further investigation is needed to elucidate potential sex-specific effects of IL-33 in metabolic regulation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Collaborators GUOF. National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990-2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet. 2024;404:2278–98.

Slomski A. Obesity is now the top modifiable dementia risk factor in the US. JAMA. 2022;328:10.

Zhang X, Gao L, Meng H, Zhang A, Liang Y, Lu J. Obesity alters immunopathology in cancers and inflammatory diseases. Obes Rev. 2023;24:e13638.

Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Despres JP, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e984–1010.

Pati S, Irfan W, Jameel A, Ahmed S, Shahid RK. Obesity and cancer: a current overview of epidemiology, pathogenesis, outcomes, and management. Cancers. 2023;15:485.

Kusminski CM, Bickel PE, Scherer PE. Targeting adipose tissue in the treatment of obesity-associated diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:639–60.

Sakers A, De Siqueira MK, Seale P, Villanueva CJ. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell. 2022;185:419–46.

Bradley D, Deng T, Shantaram D, Hsueh WA. Orchestration of the adipose tissue immune landscape by adipocytes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2024;86:199–223.

Jacks RD, Lumeng CN. Macrophage and T cell networks in adipose tissue. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2024;20:50–61.

Hammarstedt A, Gogg S, Hedjazifar S, Nerstedt A, Smith U. Impaired adipogenesis and dysfunctional adipose tissue in human hypertrophic obesity. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:1911–41.

Haczeyni F, Bell-Anderson KS, Farrell GC. Causes and mechanisms of adipocyte enlargement and adipose expansion. Obes Rev. 2018;19:406–20.

Chen Q, Xiang D, Liang Y, Meng H, Zhang X, Lu J. Interleukin-33: Expression, regulation and function in adipose tissues. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143:113285.

Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, et al. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2013;210:535–49.

Wu D, Molofsky AB, Liang HE, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Jouihan HA, Bando JK, et al. Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science. 2011;332:243–7.

Qiu Y, Nguyen KD, Odegaard JI, Cui X, Tian X, Locksley RM, et al. Eosinophils and type 2 cytokine signaling in macrophages orchestrate development of functional beige fat. Cell. 2014;157:1292–308.

Han JM, Wu D, Denroche HC, Yao Y, Verchere CB, Levings MK. IL-33 reverses an obesity-induced deficit in visceral adipose tissue ST2+ T regulatory cells and ameliorates adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. J Immunol. 2015;194:4777–83.

Brestoff JR, Kim BS, Saenz SA, Stine RR, Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells promote beiging of white adipose tissue and limit obesity. Nature. 2015;519:242–6.

Miller AM, Asquith DL, Hueber AJ, Anderson LA, Holmes WM, McKenzie AN, et al. Interleukin-33 induces protective effects in adipose tissue inflammation during obesity in mice. Circ Res. 2010;107:650–8.

Martínez-Martínez E, Cachofeiro V, Rousseau E, Álvarez V, Calvier L, Fernández-Celis A, et al. Interleukin-33/ST2 system attenuates aldosterone-induced adipogenesis and inflammation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;411:20–7.

Kai Y, Gao J, Liu H, Wang Y, Tian C, Guo S, et al. Effects of IL-33 on 3T3-L1 cells and obese mice models induced by a high-fat diet. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;101:108209.

Xu D, Zhuang S, Chen H, Jiang M, Jiang P, Wang Q, et al. IL-33 regulates adipogenesis via Wnt/beta-catenin/PPAR-gamma signaling pathway in preadipocytes. J Transl Med. 2024;22:363.

Zaibi MS, Kępczyńska MA, Harikumar P, Alomar SY, Trayhurn P. IL-33 stimulates expression of the GPR84 (EX33) fatty acid receptor gene and of cytokine and chemokine genes in human adipocytes. Cytokine. 2018;110:189–93.

Pereira MJ, Azim A, Hetty S, Nandi Jui B, Kullberg J, Lundqvist MH, et al. Interleukin-33 inhibits glucose uptake in human adipocytes and its expression in adipose tissue is elevated in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Cytokine. 2023;161:156080.

Cho CH, Patel S, Rajbhandari P. Adipose tissue lipid metabolism: lipolysis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2023;83:102114.

Grabner GF, Xie H, Schweiger M, Zechner R. Lipolysis: cellular mechanisms for lipid mobilization from fat stores. Nat Metab. 2021;3:1445–65.

Collins S. beta-Adrenergic receptors and adipose tissue metabolism: evolution of an old story. Annu Rev Physiol. 2022;84:1–16.

Yang A, Mottillo EP. Adipocyte lipolysis: from molecular mechanisms of regulation to disease and therapeutics. Biochem J. 2020;477:985–1008.

Xu D, Zhuang S, Chen H, Jiang M, Jiang P, Wang Q, et al. IL-33 regulates adipogenesis via Wnt/β-catenin/PPAR-γ signaling pathway in preadipocytes. J Transl Med. 2024;22:363.

Münzberg H, Floyd E, Chang JS. Sympathetic innervation of white adipose tissue: to beige or not to beige?. Physiology. 2021;36:246–55.

Schulz TJ, Huang P, Huang TL, Xue R, McDougall LE, Townsend KL, et al. Brown-fat paucity due to impaired BMP signalling induces compensatory browning of white fat. Nature. 2013;495:379–83.

Jiang H, Ding X, Cao Y, Wang H, Zeng W. Dense intra-adipose sympathetic arborizations are essential for cold-induced beiging of mouse white adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2017;26:686–92.e3.

Bartness TJ, Liu Y, Shrestha YB, Ryu V. Neural innervation of white adipose tissue and the control of lipolysis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35:473–93.

Ding X, Luo Y, Zhang X, Zheng H, Yang X, Yang X, et al. IL-33-driven ILC2/eosinophil axis in fat is induced by sympathetic tone and suppressed by obesity. J Endocrinol. 2016;231:35–48.

Meng X, Qian X, Ding X, Wang W, Yin X, Zhuang G, et al. Eosinophils regulate intra-adipose axonal plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119:e2112281119.

Wang L, Luo Y, Luo L, Wu D, Ding X, Zheng H, et al. Adiponectin restrains ILC2 activation by AMPK-mediated feedback inhibition of IL-33 signaling. J Exp Med. 2021;218:e20191054.

Fali T, Aychek T, Ferhat M, Jouzeau JY, Busslinger M, Moulin D, et al. Metabolic regulation by PPARgamma is required for IL-33-mediated activation of ILC2s in lung and adipose tissue. Mucosal Immunol. 2021;14:585–93.

Nguyen KD, Qiu Y, Cui X, Goh YP, Mwangi J, David T, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages produce catecholamines to sustain adaptive thermogenesis. Nature. 2011;480:104–8.

Molofsky AB, Savage AK, Locksley RM. Interleukin-33 in tissue homeostasis, injury, and inflammation. Immunity. 2015;42:1005–19.

Vishvanath L, MacPherson KA, Hepler C, Wang QA, Shao M, Spurgin SB, et al. Pdgfrbeta+ mural preadipocytes contribute to adipocyte hyperplasia induced by high-fat-diet feeding and prolonged cold exposure in adult mice. Cell Metab. 2016;23:350–9.

Mathis D. IL-33, imprimatur of adipocyte thermogenesis. Cell. 2016;166:794–5.

Odegaard JI, Lee MW, Sogawa Y, Bertholet AM, Locksley RM, Weinberg DE, et al. Perinatal licensing of thermogenesis by IL-33 and ST2. Cell. 2016;166:841–54.

de Souza GO, Wasinski F, Donato J Jr. Characterization of the metabolic differences between male and female C57BL/6 mice. Life Sci. 2022;301:120636.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073860, 81603122 to JL), and funding from the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program of Henan Association for Science and Technology (2021HYTP048 to JL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QJC performed the experiments; KD, MFL, RM, JL, and JLG collected mice samples and the basic parameters; JLL conceived, designed, and supervised this study; JLL and QJC wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The mice used in this study were treated in accordance with the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources guidelines under protocols approved by the Research and Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of the Experimental Animal Platform, School of Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University (Permit Number: ZZU-LAC20230310[11]).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Ding, K., Li, M. et al. Interleukin-33 promotes lipolysis of adipocytes and protects male mice against obesity via activation of β-adrenergic receptor signaling. Int J Obes 49, 2254–2264 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01873-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01873-8