Abstract

Background

The global increase in maternal obesity has raised concerns regarding its potential impact on offspring neurodevelopment. This study investigated the association between maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring using a large-scale national cohort in South Korea.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the Korean National Health Information Database merged with the National Health Screening Program data. Maternal BMI, measured within three years prior to delivery, was categorized based on the Asia-Pacific guidelines. Neurodevelopmental disorders, including epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, were identified using diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) up to five years of age. Multivariable Poisson and Cox regression models were used to estimate the relative risks and hazard ratios, adjusting for neonatal and maternal covariates.

Results

This study analyzed a cohort of 2,285,943 live births in South Korea (January 1, 2014–December 31, 2021) to assess the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring. After excluding neonates lacking complete medical records or follow-up data, 779,091 neonates were included in the study. Maternal obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0) was independently associated with an elevated risk of epilepsy (adjusted hazard ratio 1.13; 95% CI, 1.08–1.18) and intellectual disability (aHR 1.37; 95% CI, 1.12–1.68), following adjustment for neonatal and maternal covariates. Maternal underweight status (BMI < 18.5) was not significantly associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes. Elevated maternal BMI prior to conception was independently associated with an increased risk of epilepsy and intellectual disability in offspring.

Conclusions

The results underscore the importance of preconception weight management and support public health strategies to reduce neurodevelopmental disorders in children of mothers with overweight or obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age has been steadily increasing in the UK, the United States, and across Asia, including Korea, and represents a significant public health concern [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Recent epidemiological studies have shown that the prevalence of maternal obesity is 15–20% in the UK, with the highest rates observed in North America (obesity 18.7%; overweight/obesity 47.0%) [3, 7]. In contrast, Asian countries report substantially lower prevalence, with Japan documenting 7.8% overweight and 3.1% obesity [4], China reporting 21.8% overweight and 6.1% obesity [5], and Taiwan reporting 18.4% overweight and 10.0% obesity in recent decades [6]. In Korea, national data from 2023 demonstrated age-specific increases in obesity prevalence, reaching 22.1% among women aged 19–29 years, 28.4% among those aged 30–39 years, and 24.5% among those aged 40–49 years [8]. This East–West disparity in maternal obesity prevalence has led the World Health Organization (WHO) to propose Asia-Pacific guidelines, which adopt lower BMI thresholds to better reflect obesity-related risks in Asian population [9]. While maternal overweight and obesity remain substantially more prevalent in Western than in Asian populations, increasing trends are evident across all regions. Given this increasing trend, particular attention has been directed toward the impact of maternal obesity on offspring. It is well established that maternal obesity is associated with an increased risk of obesity in offspring [10, 11]. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that maternal obesity may negatively affect neonatal cognitive development, mental health, and brain development [10, 12,13,14]. This study aimed to evaluate the association between maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring, including epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), across BMI categories defined by WHO guidelines.

Methods

Data source and patient selection

This study was conducted using data obtained from the Korean National Health Information Database (NHID), which is maintained by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) of South Korea. The NHID integrates comprehensive healthcare utilization records, including claims and reimbursement data for all insured individuals, and health-screening data aimed at disease prevention and early detection. For the present analysis, we employed information from two key components of the NHID data and the National Health Screening Program (NHSP) for Adults and the NHSP for Infants and Children. Maternal health data were obtained from the NHSP for Adults, whereas neonatal and child health outcomes were derived from the NHSP for Infants and Children. To construct a mother–infant paired cohort, maternal and neonatal records were linked using the NHIS family tree database, which was established by combining health insurance eligibility data with resident registration records and applying a novel family code system to logically define parent–child relationships [15]. This linkage approach ensured accurate identification of mother–offspring pairs, with validation studies demonstrating parent–child matching rates exceeding 95% for births between 2010 and 2017. This approach enabled the longitudinal tracking of neonatal and early childhood developmental outcomes based on maternal pre-pregnancy health status. All the data were retrieved from the NHIS website (http://nhiss.nhis.or.kr). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Konkuk University Medical Center (IRB No. 2023-10-023). As the dataset was de-identified prior to analysis, informed consent from the study participants was waived.

Maternal variables

Maternal BMI was determined using the NHSP for adult health check-up data collected within three years prior to delivery. It was calculated by dividing weight by height squared (kg/m²) and categorized according to the Asia-Pacific guidelines as follows: underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal range (18.5–22.9), overweight at risk (23.0–24.9), obese class I (25.0–29.9), and obese class II (BMI ≥ 30.0; considered severely obese) [9]. Maternal chronic hypertension was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes I10–I15 and O10. Pregnancy-induced hypertension was defined using ICD codes O12–O15. Pregestational diabetes mellitus was identified using codes O24.0–O24.3, E10.0–E10.9, E11.0–E11.9, E12.0–E12.9, E13.0–E13.9, and E14.0–E14.9. Gestational diabetes mellitus was defined using codes O24.4 and O24.9.

Neonatal and perinatal variables

Gestational age at birth was estimated based on responses to the NHSP check-up questionnaire for infants and children. Information regarding gestational age at delivery, preterm birth status, and birth weight was also collected. Preterm birth, defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation, was identified using the expected date of delivery reported by parents for premature infants. Small for gestational age was defined as birth weight below the 10th percentile using the ICD-10 diagnostic codes P05.0, P05.1, and P05.9. The mode of delivery, specifically cesarean section, was identified using the ICD codes O82.0, O82.1, O82.2, O82.8, and O82.9. Major congenital anomalies were identified using the ICD codes Q00–Q98.4. Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions were recorded according to the following procedure codes: AJ101, AJ111, AJ121, AJ131, AJ144, AJ161, AJ201, AJ211, AJ221, AJ231, AJ244, AJ261, AJ301, AJ311, AJ321, AJ331, AJ351, and AJ051–AJ054. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed using the M587 and M158 codes.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes

Neurodevelopmental outcomes were identified based on the ICD-10 codes. Epilepsy was determined using codes G40, G41, and R56.8; however, cases diagnosed with febrile convulsions (R56.0) or convulsions of the newborn (P90) were excluded to enhance the diagnostic specificity. Cerebral palsy and intellectual disability (previously referred to as mental retardation) were identified using ICD-10 codes G80.0, G80.3, G80.4, G80.8, G80.9, and F70–F79, respectively. ASD was defined the code F84, whereas ADHD was identified using the code F90. In this study, neurodevelopmental disorders were defined based on the presence of corresponding diagnostic codes assigned to the infant during the follow-up period, which extended from birth to five years of age. Incidence rates are expressed per 1000 person-years.

Statistical analysis

Baseline maternal and neonatal characteristics were compared across maternal pre-pregnancy BMI categories of <18.5, 18.5–23, 23–25, 25–30, and ≥30 kg/m². Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SDs), and categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Differences in continuous variables across BMI groups were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. We estimated the incidence rates (IRs) per 1000 person-years for each neurodevelopmental disorder, including epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, ASD, and ADHD, across categories of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards models. The BMI group of 18.5–23.0 kg/m² was used as the reference category in all analyses. Both unadjusted and adjusted models were constructed. The adjusted models controlled for potential confounding variables, including neonatal variables (sex, mode of delivery, multiple gestations, major anomalies, small for gestational age, birth weight, NICU admission, neonatal resuscitation, and preterm birth) and maternal variables (maternal age, hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pregestational diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus, and depression). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using appropriate statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

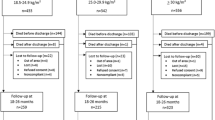

This study analyzed a cohort of 2,285,943 live births in South Korea from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2021. A total of 1616 neonates with chromosomal abnormalities were excluded, resulting in 2,284,327 live births. From this group, 886,641 neonates whose mothers had medical records available for at least three years prior to delivery (including the gestational period and two years before conception) were included in the analysis. After further excluding neonates without general health screenings or lacking follow-up examinations during infancy, the final population of 779,091 neonates was analyzed (Fig. 1). The number of study participants in each group, categorized by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, was as follows: underweight (<18.5 kg/m², n = 90,379), normal range (18.5–23.0 kg/m², n = 461,871), overweight at risk (23.0–25.0 kg/m², n = 106,951), obese class I (25.0–30.0 kg/m², n = 96,516), and obese class II (≥30.0 kg/m², n = 23,374). In the overall population, BMI was measured on average 1.39 ± 0.75 years before delivery.

Maternal and neonatal characteristics according to maternal pre-pregnancy BMI classifications were also examined and are summarized in Table 1. All assessed maternal characteristics, including maternal age, proportion of advanced maternal age (>35 years), chronic hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, and depression, increased significantly with higher pre-pregnancy BMI. Regarding neonatal characteristics, increasing maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with lower gestational age at birth, higher rates of preterm birth, increased cesarean section rates, a higher incidence of congenital anomalies, and more frequent NICU admissions and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (Table 1). A higher maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with increased birth weight and a lower incidence of small for gestational age, whereas sex distribution did not differ significantly between the groups.

Associations of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI with neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring

In the unadjusted model analysis of neurodevelopmental disorder risks in offspring based on maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (Table 2), a maternal pre-pregnancy BMI of ≥30.0 was associated with significantly increased risks of epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and ASD compared to the reference group (BMI 18.5–23 kg/m²) (Table 2). In contrast, no statistically significant association was observed between maternal BMI and ADHD in the adjusted model (P > 0.05).

In adjusted model 1 (Table 2), which was controlled for neonatal variables, maternal overweight and obesity (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m²) were significantly associated with an increased risk of both epilepsy and intellectual disability in the offspring. Additionally, maternal obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0) was associated with an increased risk of ASD (adjusted hazard ratio 1.14; 95% CI, 1.00–1.30) and ADHD (aHR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.02–1.31). Maternal underweight status (BMI < 18.5) was not associated with cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, ASD, or ADHD but was significantly associated with a modestly increased risk of epilepsy (aHR 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00–1.05). In adjusted model 2 (Table 2), which accounted for both neonatal and maternal variables, the association between epilepsy and intellectual disability remained statistically significant. Maternal overweight (BMI 25.0–30.0 kg/m²) was associated with an increased risk of epilepsy (aHR 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05–1.10) and intellectual disability (aHR 1.19; 95% CI, 1.07–1.34). Maternal obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m²) was also significantly associated with an elevated risk of epilepsy (aHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.08–1.18) and intellectual disability (aHR 1.37; 95% CI, 1.12–1.68). However, the previously observed associations between ASD and ADHD were no longer statistically significant after adjustment for both neonatal and maternal variables. Maternal underweight status (BMI < 18.5 kg/m²) was not associated with any of the assessed neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Discussion

This study examined the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring in a large Korean population-based cohort. We found that higher maternal BMI before pregnancy was associated with an increased risks of epilepsy and intellectual disability in children, even after adjusting for relevant neonatal and maternal factors. Additionally, higher pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with increased risks of both maternal and neonatal complications, including hypertension, diabetes, cesarean delivery, and adverse neonatal outcomes, such as NICU admission and preterm birth (Table 1). These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that maternal obesity contributes not only to perinatal complications but also to neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD, ASD, cerebral palsy, and cognitive impairment [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Moreover, our results support previous meta-analyses and cohort studies indicating a dose–response relationship between maternal BMI and offspring neurodevelopmental morbidity [20,21,22].

Obesity among women of childbearing age has risen worldwide, with the prevalence in the U.S. reaching 39.7% among women aged 20–39 years and 43.3% among those aged 40–59 years in 2017–2018 [23]. Similarly, Similarly, NHIS data show that the prevalence of obesity among Korean adult women has increased from 23.4% in 2012 to 27.8% in 2021 [2]. In the present study, 15.4% of mothers were classified as obese I or II (BMI ≥ 25). Because the NHSP for adults is conducted biennially, BMI was measured ~1.39 ± 0.75 years before childbirth, and gestational weight gain data were not available.

In cases of maternal obesity, the fetus may be exposed during critical periods of brain development to altered levels of fatty acids, glucose, hormones such as leptin and insulin, and increased inflammation [24,25,26]. These exposures can disrupt not only brain development but also neuroendocrine maturation and the formation of key neural pathways, potentially contributing to an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring. In addition, alterations in maternal and fetal microbiomes, as well as epigenetic modifications, have also been proposed as mechanisms through which maternal obesity may affect neurodevelopment in offspring [24, 25, 27, 28]. Consequently, maternal obesity has been associated with a spectrum of offspring outcomes, including perinatal complications, neurodevelopmental disorders (ADHD, ASD, cerebral palsy, and cognitive impairment), and other psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia [24, 25].

In the present study, maternal obesity, defined as a BMI ≥ 25, was associated with an increased risk of epilepsy and intellectual disability, and these associations remained robust even after adjustment for a wide range of maternal and neonatal variable (Table 2). These findings are consistent with a Swedish cohort study reporting that epilepsy in offspring of mothers with obesity may result not only from impaired brain development but also from perinatal complications such as nervous system malformations, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, neonatal hypoglycemia, and jaundice [20].

With respect to other neurodevelopmental outcomes, our study did not identify significant associations between maternal obesity and ADHD, ASD, or cerebral palsy within the five-year follow-up period. Similarly, Neuhaus et al. [21] found no significant association between maternal obesity and cerebral palsy (OR 1.1, 95% CI: 0.35–3.45) or ADHD (OR 2.09, 95% CI: 0.77–5.66) in offspring. However, the incidence of ASD was significantly higher in the offspring of mothers with obesity (OR: 8.73, 95% CI: 2.63–28.91) [21], and the cohort was followed up to 18 years of age. Although no significant differences in the incidence of neuropsychiatric disorders were observed between the groups during the early follow-up period, this study demonstrated an increased risk over time among offspring of mothers with obesity. In the present study, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was initially associated with the risk of cerebral palsy in the unadjusted model. However, after adjusting for neonatal factors, including preterm birth, NICU admission, and neonatal resuscitation, which are associated with neonatal brain injury, the association was no longer statistically significant.

A meta-analysis [22] reported a dose–response relationship between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and ASD, indicating that for every 5 kg/m² increase in BMI, the risk of ASD in offspring increased by 16% (HR 1.16, 95% CI: 1.01–1.33). However, it is important to note that not only obesity but also maternal diabetes may independently increase the risk of ASD. In the present study, we adjusted for both pregestational diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes mellitus to account for potential confounding effects. Moreover, Zhang et al. [29] demonstrated that both maternal overweight (OR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.10–1.18) and maternal obesity (OR 1.39, 95% CI: 1.33–1.45) were significantly associated with an increased risk of mental disorders in offspring, based on a meta-analysis examining the relationship between parental overweight and obesity and offspring mental health. Specifically, maternal pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity were linked to a higher risk of cognitive or intellectual delay (OR 1.40 (95% CI: 1.21–1.63)). Consistent with these findings, the present study also demonstrated an association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and intellectual disability in offspring and further identified a dose–response relationship according to BMI classification.

Limitations and considerations

This study has several limitations. First, although BMI values were obtained from the NHSP for Adults conducted within three years prior to delivery, they may not precisely represent the actual pre-pregnancy BMI. Nevertheless, given that the mean interval between BMI measurement and delivery was 1.39 ± 0.75 years, and considering the duration of pregnancy, these values are likely to reasonably reflect pre-pregnancy status. In addition, because the NHSP was conducted biennially, information on gestational weight gain could not be obtained. Second, while obesity in offspring may also contribute to the development of neurodevelopmental disorders later in life [30], the present study is limited by its relatively short follow-up period of up to five years. Neurodevelopmental disorders are conditions that typically manifest early in life due to disruptions in brain development [24] in this study, they were identified based on the presence of relevant diagnostic codes recorded from birth to five years of age. Third, certain factors that may influence neonatal development, such as socioeconomic status, maternal smoking, and maternal diet, were not available in the dataset obtained from the NHID and therefore could not be included in our analysis. Instead, we adjusted for a comprehensive set of neonatal and maternal variables that are relevant to early brain development. The adjusted models incorporated neonatal factors (e.g., preterm delivery, birth weight, and NICU admission) to improve clinical relevance; however, their inclusion may have introduced an overcontrol bias by acting as intermediates, thereby attenuating the observed associations. Nonetheless, the unadjusted model demonstrated crude associations between maternal BMI and neurodevelopmental outcomes, which in this study were significant for epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and ASD, but not for ADHD.

Taken together, these limitations indicate that our findings should be interpreted with caution, as they may represent conservative estimates of the overall effect of maternal BMI on offspring neurodevelopment. Nonetheless, the risk of systematic bias is considered low, and the use of a large-scale nationwide cohort strengthens the validity and generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and the occurrence of various neurodevelopmental disorders in the offspring within a large birth cohort. Increases in pre-pregnancy BMI have been associated not only with adverse neonatal and maternal outcomes, but also with long-term neurodevelopmental consequences in offspring, such as epilepsy and intellectual disability, as demonstrated in this study. These findings emphasize the importance of implementing effective weight management strategies. It is essential to manage pre-pregnancy BMI, because it can influence fetal brain development, and address excessive gestational weight gain, which is more likely to occur in women with obesity during the pre-pregnancy period. In women of reproductive age, it is crucial to regulate both pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain [11], in accordance with established guidelines [31], particularly for those with a high pre-pregnancy BMI, to improve both immediate and long-term health outcomes for both mothers and their children.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available owing to legal and ethical restrictions. However, data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Researchers may also apply for access through the NHIS data request system (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr) following institutional approval and data use agreement procedures.

References

Vahratian A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:268–73.

Jeong SM, Jung JH, Yang YS, Kim W, Cho IY, Lee YB, et al. 2023 Obesity Fact Sheet: Prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity in adults, adolescents, and children in Korea from 2012 to 2021. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2024;33:27–35.

Norman JE, Reynolds RM. The consequences of obesity and excess weight gain in pregnancy. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70:450–6.

Sugimura R, Kohmura-Kobayashi Y, Narumi M, Furuta-Isomura N, Oda T, Tamura N, et al. Comparison of three classification systems of pre-pregnancy body mass index with perinatal outcomes in Japanese obese pregnant women: a retrospective study at a single center. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:2002–12.

Xiao L, Ding G, Vinturache A, Xu J, Ding Y, Guo J, et al. Associations of maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with birth outcomes in Shanghai, China. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41073.

Chuang FC, Huang HY, Chen YH, Huang JP. Optimal gestational weight gain in Taiwan: a retrospective cohort study. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;63:220–4.

Kent L, McGirr M, Eastwood KA. Global trends in prevalence of maternal overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of routinely collected data retrospective cohorts. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2024;9:2401.

Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). The annual birth data in Korea. Obesity: ≥19 years, by sex. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2025. Available from: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=177&tblId=DT_11702_N101&conn_path=I2&language=en.

World Health Organization, International Association for the Study of Obesity, International Obesity Task Force. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia; 2000.

Godfrey KM, Reynolds RM, Prescott SL, Nyirenda M, Jaddoe VW, Eriksson JG, et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:53–64.

Catalano PM, Shankar K. Obesity and pregnancy: mechanisms of short-term and long-term adverse consequences for mother and child. BMJ. 2017;356:j1.

Cirulli F, Musillo C, Berry A. Maternal obesity as a risk factor for brain development and mental health in the offspring. Neuroscience. 2020;447:122–35.

Villamor E, Tedroff K, Peterson M, Johansson S, Neovius M, Petersson G, et al. Association between maternal body mass index in early pregnancy and incidence of cerebral palsy. JAMA. 2017;317:925–36.

Edlow AG. Maternal metabolic disease and offspring neurodevelopment—an evolving public health crisis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2129674.

Kim YY, Hong HY, Cho KD, Park JH. Family tree database of the National Health Information Database in Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019040.

Vats H, Saxena R, Sachdeva MP, Walia GK, Gupta V. Impact of maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index on maternal, fetal and neonatal adverse outcomes in the worldwide populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15:536–45.

Zhang J, Peng L, Chang Q, Xu R, Zhong N, Huang Q, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of cerebral palsy in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61:31–8.

Akinyemi OA, Tanna R, Adetokunbo S, Omokhodion O, Fasokun M, Akingbule AS, et al. Increasing pre-pregnancy body mass index and pregnancy outcomes in the United States. Cureus. 2022;14:e28695.

Kawakita T, Atwani R, Saade G. Neonatal and maternal outcomes in nulliparous individuals according to prepregnancy body mass index. Am J Perinatol. 2025;42:442–51.

Razaz N, Tedroff K, Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Maternal body mass index in early pregnancy and risk of epilepsy in offspring. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:668–76.

Neuhaus ZF, Gutvirtz G, Pariente G, Wainstock T, Landau D, Sheiner E. Maternal obesity and long-term neuropsychiatric morbidity of the offspring. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:143–9.

Wang Y, Tang S, Xu S, Weng S, Liu Z. Maternal body mass index and risk of autism spectrum disorders in offspring: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34248.

Hales CM, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020;360:1–8.

Eleftheriades A, Koulouraki S, Belegrinos A, Eleftheriades M, Pervanidou P. Maternal obesity and neurodevelopment of the offspring. Nutrients. 2025;17:1–13.

Rivera HM, Christiansen KJ, Sullivan EL. The role of maternal obesity in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:194.

Bellver J, Mariani G. Impact of parental over- and underweight on the health of offspring. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:1054–64.

Schmatz M, Madan J, Marino T, Davis J. Maternal obesity: the interplay between inflammation, mother and fetus. J Perinatol. 2010;30:441–6.

Hasebe K, Kendig MD, Morris MJ. Mechanisms underlying the cognitive and behavioural effects of maternal obesity. Nutrients. 2021;13:1–14.

Zhang S, Lin T, Zhang Y, Liu X, Huang H. Effects of parental overweight and obesity on offspring’s mental health: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0276469.

Nigg JT, Johnstone JM, Musser ED, Long HG, Willoughby MT, Shannon J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and being overweight/obesity: new data and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:67–79.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOMPWG. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted using data obtained from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). The authors gratefully acknowledge the NHIS for providing access to the National Health Information Database, which served as a critical resource for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HW Park was responsible for the conceptualization of the study and led the data curation, investigation, project administration, and writing of the original draft. SH Park contributed to data curation and performed formal analysis. YJ Kim contributed to the investigation and development of the study methodology. TE Kim was involved in the development of the methodology and participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. J Shin participated in the investigation, supervised the project, and was involved in project administration as well as the review and editing of the manuscript. No funding was received for this study. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konkuk University Medical Center (IRB No. 2023-10-023). As this study utilized anonymized secondary data from the National Health Insurance Service database, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee. No identifiable images or personal data of participants are included in this publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, H.W., Kim, TE., Park, S. et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring. Int J Obes (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01955-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01955-7