Abstract

Background

Few studies have compared gut hormone responses between bariatric procedures. This study compared Roux-en-Y and one-anastomosis gastric bypass (RYGB and OAGB) regarding glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), secretin, and glucose-insulin dynamics.

Methods

This study included 41 participants (RYGB: n = 21, OAGB: n = 20) from the randomized RYSA trial with similar amounts of bypassed intestine between the procedures. Plasma GLP-1, secretin, glucose, insulin, and C-peptide were measured during a 360-min mixed-meal test before, and at 6- and 12-months after surgery. Outcomes included total and early-phase (0–60 min) areas under the curve (AUCs) and peak concentrations. Visual analogue scales were used to measure hunger and satiety.

Results

Both procedures resulted in ~25% weight loss and marked metabolic improvements over 12 months. While fasting GLP-1 remained largely unchanged, postprandial concentrations rose markedly at 6 months (total AUC increase in RYGB: ~330%, OAGB: ~259%; p < 0.001) and remained elevated at 12 months. The increases in early-phase GLP-1 AUC were 31% higher in RYGB than OAGB at 6 months (95% CI: 3 to 68; p = 0.030) and 25% higher at 12 months (95% CI: –2 to 59; p = 0.072). Peak GLP-1 increases were significantly higher ( ~ 32%) after RYGB at both follow-ups (p < 0.05). Postprandial reduction in hunger was greater after RYGB than OAGB from baseline to 12 months. Fasting or postprandial secretin concentrations showed no significant changes. Both operations were associated with decreased fasting glucose, insulin, and C-peptide; increased early glucose but decreased glucose total AUCs; and increased insulin early AUC and C-peptide total and early AUCs. Glucose early-phase AUC and peak concentration increases were greater after RYGB than OAGB.

Conclusions

Both RYGB and OAGB lead to markedly enhanced postprandial GLP-1 responses, with no corresponding change in secretin levels. RYGB produces higher early postprandial increases in GLP-1 and glucose than OAGB, demonstrating that procedural differences can influence gut hormone and glucose responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a global health challenge, strongly associated with metabolic diseases and increased mortality [1]. Bariatric surgery remains the most effective treatment, leading to sustained weight loss, improved glycemic control and remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [2]. The underlying reasons for its metabolic success remain only partially understood. Emerging evidence points to gut hormones, such as GLP-1 and secretin, as central mediators.

Postprandial GLP-1, secreted by L-cells in the distal small intestine, sharply rises after bariatric surgery, triggering insulin release and improving glucose metabolism [3, 4]. This postprandial surge is unique to surgery and does not occur with lifestyle-induced weight loss [5]. Secretin, a less-studied hormone secreted from duodenal S cells, also potentiates insulin secretion [6] and may rise following duodenal bypass [7]. Beyond gut hormones, bariatric surgery alters glucose and insulin dynamics, producing earlier and enhanced postprandial peaks [8]. These changes likely reflect the reconfigured gastrointestinal anatomy, which accelerates nutrient delivery and stimulates GLP-1 [9] and secretin release [10]. Both GLP-1 and secretin may be crucial to the rapid metabolic reset and insulin release observed post-surgery.

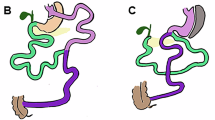

The effect of different bariatric procedures on gut hormones and glucose insulin dynamics remains unclear. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is the gold standard in bariatric surgery, but one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) emerged as a technically simpler and potentially more beneficial for T2DM resolution [11, 12]. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) have achieved comparable weight loss in randomized controlled trials [13,14,15]. However, they have anatomical differences in the site and timing of nutrient-secretion contact that could influence nutrient absorption and hormonal profiles. In RYGB, nutrients bypass proximal small intestine and travel alimentary limb before mixing with biliopancreatic secretions at the jejunojejunostomy but in OAGB, a single gastrojejunostomy is created, where nutrients immediately mix with biliopancreatic secretions. Gut mucosa hyperplasia and expansion of GLP-1–secreting L-cells contribute to the potent glucose-lowering effects in RYGB [9, 16, 17] but mechanistical data for OAGB are limited, although potentially partly similar. Preclinical studies in minipigs suggest that OAGB induces distinct macronutrient absorption patterns and GLP-1 responses compared with RYGB [18]. This raises an intriguing question: do RYGB and OAGB trigger the same metabolic signals, or are we overlooking key hormonal differences that could guide more personalized treatment?

Previous clinical studies have established that postprandial GLP-1 response after RYGB rises more than tenfold [3, 19]. Evidence for OAGB, however, remains sparse and limited to the first few months after surgery. One case series reported a 34% increase in GLP-1 and a 58% increase in secretin at 2 months post-OAGB [20]. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), postprandial GLP-1 levels increased more after OAGB than sleeve gastrectomy at 6 and 12 months [21], in line with studies comparing RYGB and sleeve procedures. Only one pilot study has compared GLP-1 levels between RYGB and OAGB, finding no significant differences; however, the comparison was cross-sectional at 2 years post-operation [22]. There are no data on postprandial secretin levels beyond 3 months for either procedure [7, 20], and postprandial glucose and insulin responses between the operations remain unexplored, with data only from the same current RCT showing no differences in total AUC values between the operations [15].

Gut hormones, insulin and glucose also shape eating behaviors [23]. Differences in their postprandial profiles can influence appetite regulation and long-term weight loss [24]. GLP-1 elevations after RYGB are generally linked to increased satiety on visual analogue scale (VAS) [24] However, comparisons of appetite ratings and their relation to gut hormone responses between RYGB and OAGB during a mixed-meal test (MMT) are lacking.

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a secondary analysis of an RCT comparing changes in fasting and postprandial GLP-1, secretin, and glucose-insulin responses between RYGB and OAGB with standardized length of the bypassed intestine, over a one-year follow-up. By mapping the distinct gut hormone, glucose and insulin profiles of these two procedures, we aim to uncover novel insights into the mechanisms driving their metabolic success and paving way for personalized patient selection for bariatric surgery.

Methods

Study design and participants

The Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass vs. One-anastomosis Gastric Bypass (RYSA, NCT02882685) study is a parallel-group randomized controlled trial with a previously reported design [25], participant flow, and primary results [15]. In short, 121 adults with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 were randomized in 1:1 ratio at the Helsinki and Oulu University Hospitals, Finland, to RYGB or OAGB using sealed envelopes, with stratification for diabetes status and sex. RYGB and OAGB procedures are illustrated in detail in ref. [25].

The RYSA intensive cohort (n = 45 at baseline) was recruited from 80 participants randomized in Helsinki based on their willingness to undergo detailed metabolic measurements at the Obesity Research Unit, University of Helsinki. The cohort measurements were performed 8 weeks before surgery and at 6- and 12-months post-surgery. For the present exploratory study, we included 41 participants (RYGB, n = 21; OAGB, n = 20) who had MMT data available from baseline to at least one follow-up (Fig. 1). One OAGB participant missed the 6-month measurement due to illness, and two OAGB participants did not complete the 12-month follow-up after discontinuing participation in the intensive cohort after 6 months.

A total of 41 participants were included: 21 underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and 20 underwent one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB). After baseline measurements, all participants completed a 4–6 week very-low calorie diet (VLCD) before surgery. Follow-up assessments were performed at 6- and 12-months post-surgery. One OAGB participant missed the 6-month visit due to illness, and two OAGB participants discontinued before the 12-month follow-up.

This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received supportive statements from the Ethical Committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District (HUS/1706/2016). All participants provided informed consent.

Interventions

RYGB and OAGB were performed as described previously [15, 25]. In RYGB, the gastric pouch was created with one horizontal 45 mm and two vertical 60 mm staplers. The length of the biliary limb was 80 cm, and that of the alimentary limb was 130 cm. In OAGB, a tubular gastric pouch was created using 60 mm staplers along a 38Fr bougie starting at the crow’s foot with a horizontal 45 mm stapler and the omega loop being 210 cm long. The length of the bypasses was standardized between the procedures to allow for a more equal comparison.

After baseline measurements, participants followed a 4–6-week very-low-calorie diet (VLCD, 800–1000 kcal/d) until the operation and then transitioned to a nutritionally tailored diet with lifestyle and exercise recommendations.

Mixed-meal test

At each laboratory visit, participants underwent a 360-min MMT. After a fasting blood sample collection, participants ingested a liquid meal of 2 620 kJ (627 kcal) with a balanced distribution of fat (24 g), carbohydrates (76 g) and protein (24 g) (Resource® 2.5 Compact, Nestle Health Science). Post-meal samples were collected at 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240 and 360 min after meal ingestion.

Plasma GLP-1 and secretin measurements

GLP-1 was measured from the MMT samples by Mercodia ELiSA kit (catalog no. 10-1278-01; RRID: AB_2892202) as in manufacturer’s instructions. Secretin was measured by in-house radioimmunoassay (RIA) method developed and published earlier in detail, using C-terminally directed secretin antibody named 5595–3, binding epitope at position 18–27 [7]. Recovery of human secretin added to human pooled plasma was calculated to 71 ± 11% (mean ± SD) and the lowest limit of detection was 1 pmol/L and dynamic range from 2.5 to 80 pmol/L.

Subjective experiences of hunger, satiety and nausea

Subjective appetite ratings (hunger, satiety and nausea) were assessed using a 100-mm VAS [26] during the MMT at every blood-sampling time point. The assessments were not recorded from five participants at baseline, and these participants were excluded from the analyses. Because nausea levels were very low at baseline, we analyzed the outcome as dichotomous (whether participants experienced nausea or not) instead of calculating continuous summary measures.

Mixed meal test missing data imputation and outcome calculations

Across all study visits and MMT time points, item-level missingness ranged from 0% to 15.4%. For molecular outcomes, the proportion of missing data was 1.7% at baseline, 5.4% at 6 months, and 10.1% at 12 months. For hunger and satiety VAS scores, the corresponding percentages were 1.1%, 3.0%, and 2.1%. The highest proportion in any single measurement was six participants (15.4%) at 12 months for GLP-1 240 min, glucose 360 min, and insulin 240 and 360 min. Most losses were attributable to failed venipuncture or to early termination of the 6- and 12-month tests because of nausea or vomiting. We assumed that data were missing at random and addressed this by performing multiple imputation. We generated 50 imputed datasets using 50 iterations of weighted predictive mean matching (mice package in R) [27]. Our imputation model for the baseline variables included key baseline characteristics (age, sex, operation group, T2DM status, height, and body weight); and selected variables measured at the same visit that could contribute to the MMT response (body weight, oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT] fasting and 2‑h glucose and insulin, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and high‑sensitivity CRP); and other MMT variables (hunger, satiety, GLP-1, secretin, glucose, insulin and C-peptide) measured at the same timepoint than the imputation was made (e.g., 30 min). Presence of nausea was not included in the imputation model and was analyzed on a complete-case basis. For 6‑ and 12‑month variables, we also included the corresponding variables from the alternate follow‑up visit (e.g., either 6- or 12-month visit), given the similarity of post‑surgery MMT responses. We confirmed convergence of the imputation algorithm by inspecting trace plots.

In each of the 50 imputed datasets, we calculated the total AUC (0–360 min) to capture the complete postprandial response, as well as the early-phase AUC (0–60 min) and peak concentrations to assess the immediate response. The AUCs were computed using trapezoidal integration (pracma package) [28].

Body composition

Height and weight were measured after an overnight fast. Body composition was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Lunar iDXA, GE Healthcare, Wisconsin, USA).

Analytical blood samples and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

Routine laboratory tests including blood count, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, lipids, and thyroid and liver function were measured from fasting plasma as previously described at the HUSLAB laboratory using standardized methods [29, 30].

A 3-h OGTT was conducted following an overnight fast. A fasting blood sample was collected before ingestion of 75 g glucose, and post-glucose samples were at 30, 60, 120, 180 min for measurements of glucose and insulin with HUSLAB standard methods as described above. Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA) and Matsuda index for insulin sensitivity were calculated from this data [29, 30].

Statistical analyses

We carried out all analyses in R (version 4.3.3). Using the nlme and lme4 packages, we fitted the linear mixed-effects models to the continuous MMT outcomes. Each model treated visit, operation group, and their interaction as fixed effects and included a random intercept for each participant. Because the biomarker distributions were right-skewed, we applied a natural-log transformation, reported geometric means with interquartile ranges, and back-transformed the fixed-effect estimates to show percent change from the reference level. For the binary nausea outcome, we fitted a generalized linear mixed model with a binomial distribution, logit link, and the same fixed- and random-effects structure. We combined the model estimates across imputed datasets using Rubin’s rules. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated all models in complete cases using the same mixed-effects specifications. We regarded two-sided p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

Similar clinical characteristics and blunted glucose and insulin responses to meal in both groups at baseline

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable between RYGB and OAGB groups, including age, BMI, sex distribution, and T2DM status (Table 1). Additionally, neither fasting nor postprandial concentrations (total and early AUCs or peak values) of GLP-1, secretin, glucose, insulin, or C-peptide differed significantly between the groups (Tables 2 and 3). At baseline, both groups showed only a small GLP-1 rise after meal ingestion, with increases of ~11 pmol/L peaking around 30 min, while secretin remained unchanged. Glucose, insulin and C-peptide levels increased postprandially, with glucose peaking around 60 min, insulin at 30 min and C-peptide at 120 min. The levels returned to baseline only after 240–360 min, highlighting impaired postprandial glucose handling and insulin secretion typical of obesity—and a situation where gut hormones do not rise to trigger insulin secretion.

Substantial but similar metabolic improvements between the groups during weight loss

Over 12 months, both RYGB and OAGB resulted in substantial but similar total body weight loss (RYGB: 25%, OAGB: 24%) and similar improvements in body fatness, insulin sensitivity (HbA1c, HOMA-index, Matsuda-index), plasma lipid levels, liver function tests and inflammation (Table 1). The resolution of T2DM and changes in Baecke physical activity index were also comparable between groups.

A substantial increase in postprandial GLP-1 but not secretin response post-surgery, with a more pronounced early AUC and peak in GLP-1 after RYGB than OAGB

Along with the substantial weight loss and metabolic improvements, bariatric surgery induced a dramatic increase in postprandial GLP-1 secretion in both groups. From baseline to 6 and to 12 months, total GLP-1 AUC (0–360 min) increased ~330% after RYGB and ~260% after OAGB (both p < 0.001; Table 2, Fig. 2). Postprandial dynamics shifted towards an earlier response with a striking GLP-1 increase at 15–30 min and a return towards baseline already at 240 min at both 6 and 12 months. Fasting GLP-1 concentrations, however, remained largely unchanged in both groups across all timepoints.

Postprandial dynamics during the 360-min mixed meal test for plasma A glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), B secretin, C glucose, D insulin, and E C-peptide at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB, red) and one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB, blue). Data are shown as pooled medians with interquartile ranges. Units are indicated on the Y-axis; sampling time points (minutes) are shown on the X-axis.

However, early GLP-1 AUC (0–60 min) and GLP-1 peak concentrations around at 15–30 min revealed differences between RYGB and OAGB. From baseline to 6 and 12 months, increases in early AUC were 31% (p = 0.030) and 25% (p = 0.072) greater in RYGB compared with OAGB, respectively, and increases in peak GLP-1 concentrations were ~32% greater after RYGB than OAGB at both time points (both p < 0.05). These findings indicate that RYGB produces a steeper GLP-1 release than OAGB.

Secretin responses remained stable after both surgeries. Fasting values, and postprandial total AUC, early AUC, and peak concentrations showed no significant changes over time or differences in changes between groups (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Improved glycemic control in both groups post-surgery, with a more pronounced early postprandial glucose response after RYGB than OAGB

Because GLP-1 responses are tightly connected to glucose–insulin dynamics, we also assessed glucose, insulin and C-peptide levels post-surgery. Both fasting and postprandial responses (total AUCs) for glucose, and C-peptide decreased substantially and similarly in RYGB and OAGB (Table 3, Fig. 2), indicating improved glycemic control from baseline to 6 and 12 months. From baseline to 12 months RYGB and OAGB led to -9% and -11% decrease in glucose AUC and −19% and −19% decrease in C-peptide AUC, respectively. Changes in insulin AUC were not statistically significant. Additionally, postprandial dynamics shifted towards a more heightened and earlier-peaking profile. Glucose and insulin peaked already at 15–30 min (vs. 30–60 min at baseline), and C-peptide at 60 min (vs. 120 min at baseline), gradually returning to fasting levels already by 180–240 min within both groups at both time points.

The most notable differences between surgeries emerged in the early postprandial phase. Increases in early glucose AUC (0–60 min) were 17% and 19% greater, and peak glucose concentration (at ~30 min) were 18% and 28% greater after RYGB compared with OAGB at 6 and 12 months, respectively (p < 0.05), suggesting faster glucose absorption in the RYGB group. While numerically insulin and C-peptide peak concentrations and early AUCs followed a similar pattern, we could not confirm statistical difference between groups.

Reduced hunger measured by VAS scale in RYGB compared with OAGB during weight loss, but no observable differences in satiety or nausea between operations

To test whether differences in GLP-1 or glucose dynamics translated into subjective appetite sensations, we assessed fasting and postprandial hunger, satiety and nausea during the MMT. Baseline scores did not differ between RYGB and OAGB (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). At 12 months, RYGB showed a greater reduction in postprandial hunger than OAGB (−26% vs. +12%, p = 0.038, respectively), and this difference remained significant after adjusting for baseline values. Changes in satiety did not differ between procedures. The proportion of participants reporting nausea increased from baseline to 6 and 12 months in both groups, with no between-group differences (p > 0.81).

Postprandial visual analogue scale (VAS, 0–100) scores for A hunger and B satiety during the 360-minute mixed meal test at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB, red) and one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB, blue). Data are shown as pooled means with standard deviations. Units are indicated on the Y-axis; sampling time points (minutes) are shown on the X-axis.

Changes in GLP-1 AUC were not associated with changes in hunger or satiety from baseline to 6 or 12 months (Supplementary Fig. 1). No significant associations were found with appetite ratings and glucose or insulin measures.

Complete-case analysis supports robustness of the results

Because AUCs and peak values are derived from multiple time points, a single missing sample can preclude calculation and unnecessarily exclude otherwise informative participants. We therefore used multiple imputation as the primary approach to retain partially observed cases and improve precision while reducing bias. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated all models in complete cases (Supplementary Tables 2–4). Estimates were directionally and numerically concordant with the results from the multiple-imputation analysis. As expected with fewer observations, confidence intervals were typically wider. For GLP-1, the 12-month peak between-group difference in change remained significant, whereas the 6-month peak and 12-month early AUC differences were similar in magnitude but not statistically significant. For insulin, the complete-case analysis yielded between-group differences of similar magnitude but with smaller p-values than the multiple-imputation analysis. Taken together, these findings support the robustness of our conclusions.

Discussion

This study provides new insights into the GLP-1 and secretin responses as well as glucose and insulin dynamics induced by RYGB and OAGB up to one year after surgery. Both procedures resulted in a marked increase in postprandial GLP-1 concentrations, with RYGB eliciting a higher increase in early-phase response compared to OAGB. Additionally, early glucose response in RYGB was elevated compared to OAGB, and subjective hunger sensations were more reduced. In contrast, secretin levels remained largely unchanged following either procedure. These findings underscore that variations in bariatric surgery techniques can alter gut hormone responses, highlighting the benefits but also the differences of RYGB and OAGB in restoring metabolic health.

Our results reveal a slightly higher peak and early GLP-1 response following RYGB than OAGB, which coincided with a greater early glucose response. The increased GLP-1 levels following RYGB are well established [19], but less investigated after OAGB. Only one cross-sectional pilot study directly compared GLP-1 levels between RYGB and OAGB, finding no significant differences in peak or total AUC values at 2 years [22]. The amplified early GLP-1 and glucose responses after RYGB may have both metabolic and clinical implications. Beyond enhancing insulin and glucagon secretion, GLP-1 plays a central role in satiety regulation, appetite suppression, and even maintenance of mood and cognition [31, 32]. Its receptors are widely distributed across multiple organs. GLP-1-based therapies have transformed the treatment for T2DM and obesity, with expanding use in cardiovascular, renal, and neurodegenerative diseases [32, 33]. Thus, even small variations in GLP-1 responses may influence metabolic outcomes. The sharper glycemic response after RYGB may support more rapid early glucose control and improve satiety but could also increase the risk of post-bariatric hypoglycemia [34]. Additionally, large postprandial glucose peaks have been associated with vascular risk markers such as atherosclerosis [35], arterial pulse pressure and hypertension in non-surgical samples [36]. However, whether the observed differences translate into clinical outcomes remains to be studied. The metabolic benefits of both operations are nevertheless evident.

In contrast to GLP-1, the role of secretin after bariatric surgery remains unclear. Our data showed no significant changes in secretin levels after RYGB or OAGB up to one year, which differs from earlier short-term studies [7, 20]. These discrepancies may reflect methodological differences, shorter follow-up durations, or physiological adaptation over time. While rodent studies suggest that RYGB upregulates intestinal secretin gene expression [37] this has not been confirmed in humans [38]. Interestingly, secretin receptor knockout mice maintain normal food intake and weight, suggesting that chronic absence of secretin signaling may not mirror the acute effects observed with pharmacological stimulation [39]. Despite these uncertainties, secretin remains a promising target for obesity treatment. Experimental studies in mice show that secretin analogues can increase energy expenditure, reduce food intake, and enhance glucose tolerance [37, 40], especially when combined with GLP-1 receptor agonists [41]. Additionally, secretin stimulates brown adipose tissue thermogenesis in rodents and humans [39], and a recent RCT showed that supraphysiological secretin infusion reduced food intake in healthy men [42]. Given its widespread receptor expression across multiple tissues [43], secretin may have broader metabolic effects.

Our study shows a greater and more sustained reduction in postprandial hunger after RYGB compared with OAGB. Notably, only RYGB led to a consistent decrease in postprandial hunger; however, this did not translate into satiety experiences. Previous research has demonstrated that postprandial hunger typically decreases after RYGB and sleeve gastrectomy alongside increased satiety [44, 45]. However, similar data following OAGB are lacking. Importantly, RYGB patients often report not feeling deprived or hungry, even while in steep negative energy balance [46]. In our study, the decreases in hunger co-occurred with increases in early GLP-1 after RYGB; however, we did not observe clear association between them. While GLP-1 elevations are generally linked to greater satiety on VAS scales [24] after RYGB, comparable evidence after OAGB is missing. Concerning the increase in postprandial nausea, our cohort aligns with earlier studies using patient-reported outcomes by questionnaires [47]. The clinical relevance of the relationship between reduced hunger and increased GLP-1 in relation to different bariatric procedures still warrants further investigation. Nevertheless, VAS scores are a subjective rating and should be treated as such.

The distinct responses between RYGB and OAGB likely reflect their anatomical differences. Although we standardized lengths of the bypassed intestines, the configurations still differ. In RYGB, nutrients pass ~130 cm alone along the alimentary limb before mixing with secretions that have traveled ~80 cm through the biliopancreatic limb, while in OAGB, nutrients bypass whole of the ~210 cm before meeting secretions directly at the gastrojejunostomy. Thus, RYGB delays nutrient–secretion contact proximally, whereas OAGB provides immediate mixing distally. This can contribute to procedure-specific differences in nutrient absorption and hormone dynamics [18, 25]. RYGB rapidly delivers nutrients to the distal intestine, accelerating glucose absorption and triggering a pronounced insulin and GLP-1 release [9]. This is likely further enhanced by an increase in GLP-1–expressing L-cells in the gut mucosa [9, 16, 17], and gut mucosa hyperplasia that increases intestinal glucose disposal after RYGB [16]. Although similar mechanisms may operate after OAGB, the response appears less exaggerated. While RCTs with standardized limb lengths report similar weight loss and metabolic improvements between RYGB and OAGB up to 1–2 years (14–16), our findings indicate that the two procedures nevertheless elicit distinct postprandial responses.

The strengths of our study include its underlying randomized controlled design, standardized surgical techniques, and well-matched cohorts in terms of sex, age, and T2DM status. Importantly, this is the first study to assess postprandial GLP-1, secretin, glucose, insulin, and C-peptide profiles between RYGB and OAGB over a one-year period. A limitation may be the missing MMT data points in few of the persons, which is typical of this method. However, imputed and complete-case analyses yielded results similar in direction and magnitude, confirming that our approach to handling missingness was suitable for the study. In addition, longer follow-up may be needed to fully understand the long-term metabolic implications of these hormonal differences.

Conclusions

In this study, we show that both RYGB and OAGB led to striking increases in postprandial GLP-1 levels together with improved glycemic control while secretin levels remained unchanged. RYGB elicited a more pronounced early postprandial GLP-1 and glucose responses than OAGB, suggesting differential metabolic responses between the procedures that may influence surgical outcomes and potential patient selection.

Data availability

Data can be available from the authors upon a reasonable request.

References

Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:288–98.

Albaugh VL, He Y, Münzberg H, Morrison CD, Yu S, Berthoud HR. Regulation of body weight: Lessons learned from bariatric surgery. Mol Metab. 2023;68. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MOLMET.2022.101517.

Holst JJ, Madsbad S. Mechanisms of surgical control of type 2 diabetes: GLP-1 is key factor. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1236–42.

Pucci A, Batterham RL. Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: similar, yet different. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;42:117.

Laferrère B, Teixeira J, McGinty J, Tran H, Egger JR, Colarusso A, et al. Effect of weight loss by gastric bypass surgery versus hypocaloric diet on glucose and incretin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2479–85.

Bayliss WM, Starling EH. The mechanism of pancreatic secretion. J Physiol. 1902;28:325–53.

Modvig IM, Andersen DB, Grunddal KV, Kuhre RE, Martinussen C, Christiansen CB, et al. Secretin release after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reveals a population of glucose-sensitive S cells in distal small intestine. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020;44:1859.

Ferrannini E, Mingrone G. Impact of different bariatric surgical procedures on insulin action and β-cell function in type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2009;32:514.

Dirksen C, Bojsen-Møller KN, Jørgensen NB, Jacobsen SH, Kristiansen VB, Naver LS, et al. Exaggerated release and preserved insulinotropic action of glucagon-like peptide-1 underlie insulin hypersecretion in glucose-tolerant individuals after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2679–87.

Zhang X, Young RL, Bound M, Hu S, Jones KL, Horowitz M, et al. Comparative effects of proximal and distal small intestinal glucose exposure on glycemia, incretin hormone secretion, and the incretin effect in health and type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2019;42:520–8.

Lee WJ, Almalki OM, Ser KH, Chen JC, Lee YC. Randomized controlled trial of one anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-En-Y gastric bypass for obesity: comparison of the YOMEGA and Taiwan studies. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3047–53.

Magouliotis DE, Tasiopoulou VS, Tzovaras G. One anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a meta-analysis. Clin Obes. 2018;8:159–69.

Disse E, Pasquer A, Espalieu P, Poncet G, Gouillat C, Robert M. Greater weight loss with the omega loop bypass compared to the Roux-en-y gastric bypass: a comparative study. Obes Surg. 2014;24:841–6.

Robert M, Espalieu P, Pelascini E, Caiazzo R, Sterkers A, Khamphommala L, et al. Efficacy and safety of one anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for obesity (YOMEGA): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1299–309.

Heinonen S, Saarinen T, Meriläinen S, Sammalkorpi H, Penttilä AK, Koivikko M, et al. Roux-en-Y versus one-anastomosis gastric bypass (RYSA study): weight loss, metabolic improvements, and nutrition at 1 year after surgery, a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Obesity. 2023;31:2909–23.

Ribeiro-Parenti L, Jarry AC, Cavin JB, Willemetz A, Le Beyec J, Sannier A, et al. Bariatric surgery induces a new gastric mucosa phenotype with increased functional glucagon-like peptide-1 expressing cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–11.

Cavin JB, Couvelard A, Lebtahi R, Ducroc R, Arapis K, Voitellier E, et al. Differences in alimentary glucose absorption and intestinal disposal of blood glucose after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:454–64.e9.

Marciniak C, Chávez-Talavera O, Caiazzo R, Hubert T, Zubiaga L, Baud G, et al. Characterization of one anastomosis gastric bypass and impact of biliary and common limbs on bile acid and postprandial glucose metabolism in a minipig model. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021;320:E772–E783.

Hutch CR, Sandoval D. The role of GLP-1 in the metabolic success of bariatric surgery. Endocrinology. 2017;158:4139.

Elsageer EM, Mahran KM, Mohamed FH, Elsharkawy EA. The impact of bariatric procedures on local gastrointestinal hormones. Minia J Med Res. 2022;33:23–32.

Roushdy A, Abdel-Razik MA, Emile SH, Farid M, Elbanna HG, Khafagy W, et al. Fasting ghrelin and postprandial GLP-1 levels in patients with morbid obesity and medical comorbidities after sleeve gastrectomy and one-anastomosis gastric bypass: a randomized clinical trial. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2021;31:28–35.

De Bandt D, Rives-Lange C, Frigout Y, Bergerot D, Blanchard A, Le Gall M, et al. Similar gut hormone secretions two years after one anastomosis gastric bypass and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a pilot study. Obes Surg. 2022;32:757–62.

Zanchi D, Depoorter A, Egloff L, Haller S, Mählmann L, Lang UE, et al. The impact of gut hormones on the neural circuit of appetite and satiety: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:457–75.

Astrup A. Reflections on the discovery GLP-1 as a satiety hormone: implications for obesity therapy and future directions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2024;78:551–6.

Saarinen T, Meriläinen S, Koivukangas V, Pietiläinen KH, Juuti A. Prospective randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy and safety of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and one-anastomosis gastric bypass (the RYSA trial): trial protocol and interim analysis. Trials. 2019;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3898-y.

Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, Rowley E, Reid C, Elia M, et al. The use of visual analogue scales to assess motivation to eat in human subjects: a review of their reliability and validity with an evaluation of new hand-held computerized systems for temporal tracking of appetite ratings. Br J Nutr. 2000;84:405–15.

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67.

Borchers HW. pracma: Practical Numerical Math Functions, R package version 2.4.6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pracma 2025.

Heinonen S, Buzkova J, Muniandy M, Kaksonen R, Ollikainen M, Ismail K et al. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis in adipose tissue in acquired obesity. Diabetes. 2015; 64. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-1937.

van der Kolk BW, Saari S, Lovric A, Arif M, Alvarez M, Ko A, et al. Molecular pathways behind acquired obesity: adipose tissue and skeletal muscle multiomics in monozygotic twin pairs discordant for BMI. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100226.

Holst JJ. Incretin hormones and the satiation signal. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:1161–8.

Zheng Z, Zong Y, Ma Y, Tian Y, Pang Y, Zhang C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:1–29.

Andreasen CR, Andersen A, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T. How glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists work. Endocr Connect. 2021;10:R200.

Jalleh RJ, Umapathysivam MM, Plummer MP, Deane A, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Postprandial plasma GLP-1 levels are elevated in individuals with postprandial hypoglycaemia following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass—a systematic review. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2023;24:1075–88.

Temelkova-Kurktschiev TS, Koehler C, Henkel E, Leonhardt W, Fuecker K, Hanefeld M. Postchallenge plasma glucose and glycemic spikes are more strongly associated with atherosclerosis than fasting glucose or HbA1c level. Diab Care. 2000;23:1830–4.

Anan F, Masaki T, Eto T, Fukunaga N, Iwao T, Kaneda K, et al. Postchallenge plasma glucose and glycemic spikes are associated with pulse pressure in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1565–71.

van Witteloostuijn SB, Dalbøge LS, Hansen G, Midtgaard SR, Jensen GV, Jensen KJ, et al. GUB06-046, a novel secretin/glucagon-like peptide 1 co-agonist, decreases food intake, improves glycemic control, and preserves beta cell mass in diabetic mice. J Pept Sci. 2017;23:845–54.

Nergård BJ, Lindqvist A, Gislason HG, Groop L, Ekelund M, Wierup N, et al. Mucosal glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide cell numbers in the super-obese human foregut after gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:1237–46.

Li Y, Schnabl K, Gabler SM, Willershäuser M, Reber J, Karlas A, et al. Secretin-activated brown fat mediates prandial thermogenesis to induce satiation. Cell. 2018;175:1561–74.e12.

Cheng CYY, Chu JYS, Chow BKC. Central and peripheral administration of secretin inhibits food intake in mice through the activation of the melanocortin system. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;36:459–71.

Loeffler M, Klepac K, Baljuls A, Hamilton B, Mayer-Wrangowski S, Haebel P, et al. Effects of a long-acting secretin peptide analog alone and in combination with a GLP-1R agonist in a diet-induced obesity mouse model. Mol Metab. 2023;74:101765.

Heimbürger SMN, Bentzen MJ, Kizilkaya HS, Hartmann B, Holst JJ, Rosenkilde MM, et al. Secretin infusion decreases food intake in healthy men-a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2024;191:545–57.

Afroze S, Meng F, Jensen K, McDaniel K, Rahal K, Onori P, et al. The physiological roles of secretin and its receptor. Ann Transl Med. 2013;1:29–29.

Aukan MI, Skårvold S, Brandsæter IØ, Rehfeld JF, Holst JJ, Nymo S, et al. Gastrointestinal hormones and appetite ratings after weight loss induced by diet or bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2023;31:399–411.

Al-Najim W, Docherty NG, Le Roux CW. Food intake and eating behavior after bariatric surgery. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:1113–41.

Korner J, Bessler M, Cirilo LJ, Conwell IM, Daud A, Restuccia NL, et al. Effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on fasting and postprandial concentrations of plasma ghrelin, peptide YY, and insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:359–65.

Kushner BS, Freeman D, Sparkman J, Salles A, Eagon JC, Eckhouse SR. Assessment of postoperative nausea and vomiting after bariatric surgery using a validated questionnaire. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16:1505–13.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the whole Obesity Research Unit team and especially the following colleagues for their contribution to this work: Elisa Silvennoinen (nutritionist), Tarja Hallaranta (study nurse). We also thank all the participants for their invaluable contributions to the study.

Funding

The study was supported by the Academy of Finland (361956 and 338417 for SH), (266286, 272376, 314383, 335443, KHP) (314457 AJ), Finnish Medical Foundation (SH, KHP, AJ), Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation (SH, KHP), Orion Foundation (SH), Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF10OC1013354, NNF17OC0027232, NNF20OC0060547, KHP, NNF23SA0083953 and NNF25OC0100827 for SH), Paulo Foundation (SH, KHP), Gyllenberg Foundation (KHP), Sigrid Juselius Foundation (KHP), Paavo Nurmi Foundation (SH), Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research (KHP), Helsinki University Hospital Research Funds (SH, KHP, AJ), Government Research Funds (KHP, SH) and the University of Helsinki (KHP). The funders had no role in planning the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJ, TS and KHP designed the study. AJ and TS recruited the patients, performed the bariatric surgeries, coordinated the study and the follow-up of the patients. KHP performed the metabolic studies and ran the meal tests. S.H. participated in the metabolic studies. JJH measured the plasma GLP-1 and Secretin data. P-H.G. provided the DEXA data. JEK performed the statistical analyses, and JEK and SH wrote the tables and the figures. SH and JEK wrote the manuscript. KHP is the guarantor of the work. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript and read and accepted the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved centrally by the Helsinki University Hospital Ethics Committee DNro 1/13/03/02/2016 (RYSA), registered at ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT02882685, and reviewed by the Helsinki University Hospital Research Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heinonen, S., Karppinen, J.E., Saarinen, T. et al. Greater early postprandial GLP-1 increase after Roux-en-Y than one-anastomosis gastric bypass, with unchanged secretin: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-02000-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-02000-3