Abstract

Background

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) regulates over 80 contaminants in community water systems (CWS), including those relevant to infant health outcomes. Multi-cohort analyses of the association between measured prenatal public water contaminant concentrations and infant health outcomes are sparse in the US.

Objective

Our objectives were to (1) develop Zip Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA)-level CWS contaminant concentrations for participants in the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Cohort and (2) evaluate regional, seasonal, and sociodemographic inequities in contaminant concentrations at the ZCTA-level. The ECHO Cohort harmonizes data from over 69 extant pregnancy and pediatric cohorts across the US.

Methods

We used CWS estimates derived from the USEPA’s Six-Year Review 3 (2006–2011) to develop population-weighted, average concentrations for 10 contaminants across 7640 ZCTAs relevant to the ECHO Cohort. We evaluated contaminant distributions, exceedances of regulatory thresholds, and geometric mean ratios (with corresponding percent changes) associated with ZCTA sociodemographic characteristics via spatial lag linear regression models.

Results

We observed significant regional variability in contaminant concentrations across the US. ZCTAs were most likely to exceed the maximum contaminant level for arsenic (n = 100, 1.4%) and the health-protective threshold for total trihalomethanes (n = 3584, 64.0%). A 10% higher proportion of residents who were American Indian/Alaskan Native and Hispanic/Latino was associated with higher arsenic (11%, 95% CI: 7%, 15%; and 2%, 95% CI: 0%, 3%, respectively) and uranium (15%, 95% CI: 10%, 21%; and 9%, 95% CI: 6%, 12%, respectively) concentrations.

Impact

Nationwide epidemiologic analyses evaluating the association between US community water system contaminant concentration estimates and associated adverse birth outcomes in cohort studies are sparse because public water contaminant concentration estimates that can be readily linked to participant addresses are not available. We developed Zip Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA)-level CWS contaminant concentrations that can be linked to participants in the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Cohort and evaluated regional, seasonal, and sociodemographic inequities in contaminant concentrations for these ZCTAs. Future epidemiologic studies can leverage these CWS exposure estimates in the ECHO Cohort to evaluate associations with relevant infant outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Regulated United States (US) public water systems are a significant source of chronic exposure to contaminants associated with adverse birth health outcomes (e.g., arsenic, lead, nitrates, and disinfection byproducts) [1,2,3,4]. More than 94% of US residents receive at least some drinking water from community water systems (CWSs), defined as public water systems that serve the same population year-round [5]. The US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) regulates six classes of contaminants in CWSs, including inorganic contaminants (e.g., arsenic), radionuclides (e.g., uranium), and disinfection byproducts (e.g., total trihalomethanes). Because the USEPA considers cost and technical feasibility, as well as public health benefits when setting maximum contaminant levels (MCLs), US residents are often served by CWSs with contaminant concentrations that exceed health-protective guidelines and regulatory standards set by other nations, states, and agencies [1,2,3, 6, 7].

Substantial evidence supports that significant racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in some CWS contaminant concentrations (e.g., arsenic) and adverse infant health outcomes (e.g., preterm birth) persist across the US [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Extensive scholarship supports that racism produces health inequalities and is a fundamental cause of disease [9, 10, 13]. Structural racism is “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination, through mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, and so on)”, and produces disparities in part through the creation and reinforcement of inequalities in environmental exposures, health care access and quality, and other social and psychosocial determinants of health [12, 14,15,16]. Mechanisms underlying birth outcome disparities include direct discrimination [14, 17, 18], poor medical treatment including pre- and post-natal care [19, 20], and elevated environmental exposures, including toxic metals [21, 22].

Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in some public water exposures may underlie infant health disparities, yet this remains inadequately studied [23]. Nationwide, higher county-level proportions of Hispanic/Latino and American Indian/Alaskan Native residents and lower proportions of non-Hispanic White residents have been associated with higher CWS arsenic and uranium concentrations (independent of region, source water type, system size, and socioeconomic vulnerability); similar associations are observed specifically in California [1, 6,7,8, 24]. Some evidence supports that Black residents are served by CWSs reporting higher lead concentrations [3, 7]. Hispanic/Latino residents are also served by CWSs with higher concentrations of fluoride and nitrates and are more likely served by CWSs exceeding arsenic, uranium, and fluoride MCLs [1, 2, 7, 24, 25]. These inequities are more likely and/or more severe in geographic regions with both a high percentage of marginalized public water users and relatively high concentrations of specific geogenic contaminants (e.g., Hispanic/Latino communities in the Southwest) [7, 8, 26]. Mechanisms underlying and reinforcing these inequities are specific to the contaminant, impacted community, and region, but include linguistic isolation, direct withholding of resources and infrastructure investments, selective enforcement of federal regulations, and bias in targeted tap sampling and monitoring [7, 27,28,29,30]. Inequities specifically impacting Black, Hispanic/Latino, and American Indian communities reflect white supremacy and structural racism embedded in infrastructure, investment, and regulatory decision-making that specifically benefit non-Hispanic White communities to the detriment of other communities [7, 10, 27, 28, 31, 32].

Numerous epidemiologic studies [7] have evaluated the association between these contaminants and relevant infant health outcomes (arsenic [33], nitrates [34], disinfection byproducts [35], and others [36]). However, few studies have evaluated these associations in multi-cohort analyses across the US with participants from diverse regional, socioeconomic, and racial/ethnic groups. Drinking water exposure assessment is challenging in large, multi-cohort consortiums because nationwide areal level estimates of CWS contaminants that can be leveraged for epidemiologic research were previously unavailable, and household sampling is costly. Because distribution boundaries are not available for most US CWSs, nationwide exposure assessments must generate estimates at areal-level administrative boundaries that can be readily linked to participant addresses (similar approaches have been used for air pollution exposure assessment) [37, 38]. We recently developed and validated a method for developing ZIP Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA)-level estimates of CWS contaminants that can be readily assigned to cohort participants by residential ZIP Code [4]. In this study, we generated ZCTA-level water contaminants relevant for observational birth cohorts in the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Cohort. The ECHO Program was established in 2016 to understand the effects of environmental exposures on child health and development and initially included 69 extant pregnancy and pediatric cohorts across the US. The ECHO Cohort harmonizes existing data for over 60,000 participants, which are heterogeneous by geographic location, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, and uses a standardized protocol to collect new data. Although the ECHO Cohort is not nationally representative, it is an excellent resource to evaluate epidemiologic associations between CWS contaminants and infant health outcomes and to identify opportunities to reduce inequities in CWS exposures and birth outcomes.

Our objectives were to (1) develop ZCTA-level contaminant concentrations for ECHO Cohort sites across the US, and (2) evaluate regional, seasonal, and sociodemographic inequities in ZCTA contaminant concentrations. While there are more than 80 federally regulated contaminants, we evaluated 10 inorganic, radionuclide, and disinfection byproduct contaminants that are commonly detected in CWSs nationwide (arsenic, barium, chromium, fluoride, nitrate, nitrite, selenium, uranium, total trihalomethanes (defined and regulated as the sum of bromoform, chloroform, bromodichloromethane, and dibromochloromethane) and haloacetic acids (bromo-, chloro-, dibromo-, dichloro-, trichloro-acetic acids)). These contaminants were also selected because prenatal exposure is either established as or potentially relevant for infant and child health outcomes [39]. We estimated ZCTA-level contaminant concentrations using previously developed CWS-level estimates generated from routine compliance monitoring records compiled by USEPA’s Six Year Review 3 of Contaminant Occurrence Database (2006–2011) required by the Safe Drinking Water Act [2, 6, 40]. We predicted that we would observe substantial regional variability in ZCTA contaminant concentrations across the US and that higher proportions of non-Hispanic White residents and higher measures of socioeconomic advantage would be associated with lower contaminant concentrations, as previously observed at other spatial resolutions [8, 41]. Areal-level concentrations presented here estimate public drinking water exposures across the ECHO Cohort and can facilitate future epidemiologic analyses. Our descriptive analyses of geographic and sociodemographic inequities in ZCTA concentrations can support hypothesis generation for future studies.

Materials and methods

Study population and exclusion criteria

Our objective was to develop areal-level estimates of CWS contaminant concentrations at the ZCTA-level that could be merged to participants in the ECHO Cohort by residential address. Our study population therefore consisted of US ZCTAs (using 2010 boundaries) overlapping counties that contained at least one ECHO Cohort pregnant person. The ECHO Cohort contains over 60,000 participants from 69 pregnancy and pediatric cohort sites. We identified 34 observational birth cohort sites in the ECHO Cohort (recruiting from 32 states) and identified counties relevant to recruitment areas for these cohort sites, as we did not have access to participant ZIP Code information. We excluded ECHO Cohort sites from cohorts that were outcome-enriched (e.g., cohorts that recruited only preterm infants because our interest is in developing water exposure estimates and evaluating associations with birth outcomes), that exclusively enrolled participants reliant on private wells or water hauling, and that exclusively enrolled participants from states that did not have CWS contaminant estimates available (e.g., CO, DE, MS, GA, and Puerto Rico) [42]. We identified a total of 466 potentially relevant counties and proceeded to develop ZCTA-level estimates for all 2010 ZCTAs overlapping with these county boundaries.

Developing CWS contaminant concentration estimates

All data management and analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.3. In order to develop population-weighted, average ZCTA-level contaminant concentrations for all ZCTAs overlapping with the 466 relevant counties, we used a method previously developed and validated by our team for other large, multi-site cohorts in both urban and rural areas [4]. Briefly, CWS-level contaminant concentration estimates were previously generated by our team using routine compliance monitoring records collected for the USEPA’s Six Year Review 3 of Contaminant Occurrence Database, which represents over 95% of all public systems nationwide (further details are available in Supplemental Material Methods and prior publications) [6, 40, 42, 43]. CWS-level concentration estimates reflect average concentrations distributed to consumers (i.e., in finished water) and were aggregated to time periods that correspond to USEPA’s Standard Monitoring Framework to reduce differential missingness and bias by source water type, system size, and prior contaminant violations and detections (2006–2011, 2006–2008, and 2009–2011 for arsenic; 2006–2011 for barium, chromium, and selenium; 2000–2011 for uranium; and seasonally/quarterly from 2006–2011 for disinfection byproducts) [6, 40]. For disinfection byproducts, USEPA defines and regulates total trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids as the sum of four (bromoform, chloroform, bromodichloromethane, and dibromochloromethane) and five (bromo-, chloro-, dibromo-, dichloro-, trichloro-acetic acid) contaminants, respectively, although hundreds of drinking water disinfection byproducts have been identified [44]. In this analysis, we aggregated all contaminant concentrations to the overall 2006-2011 time period, except for uranium, which we aggregated to the 2000-2011 time period to account for differences in monitoring requirements under the Radionuclide Rule [42]. To reflect differences across contaminants in method detection limits and concentration distributions, we rounded arsenic, barium, chromium, nitrite, selenium, and uranium concentrations to two decimal places, disinfection byproduct concentrations to one decimal place, and fluoride and nitrate concentrations to integers [6].

We first assigned all relevant CWSs to ZCTAs (some ZCTAs are served by multiple CWSs, and some CWSs serve multiple ZCTAs) [4]. One major challenge in public water exposure assessment is that only 16 states publish CWS distribution boundaries which can be intersected with ZCTA boundaries. Therefore, we utilized two complementary approaches to assign CWSs to ZCTAs. For each county in DC, FL, IA, KY, MA, MD, MI, MT, ND, NE, NY, OH, RI, SD, TN, VA, and WI, we extracted all CWSs serving that county (reliably reported in the USEPA’s Safe Drinking Water Information System) and assigned each CWS to all relevant ZCTAs by joining reported city-served and/or water system name to ZCTAs via the US Census 2010 ZCTA to Place Relationship File and USPS ZIP to Locale file [45, 46]. We generated weights for each CWS within a ZCTA based on the adjusted total population served as reported by USEPA. For the states of AR, AZ, CA, CT, IL, MN, MO, NC, NJ, NM, OK, PA, TX, UT, and WA, shapefiles of the distribution boundaries of water systems were publicly available and we assigned CWSs to ZCTAs by overlapping CWS distribution boundaries with 2010 Census ZCTA boundaries using the “st_intersection” function in the sf package in R [47]. We generated weights for each CWS within a ZCTA based on overlapping Census block population counts. For all states, we then generated population-weighted average estimates of CWS contaminants at the ZCTA-level.

ZCTAs within ECHO-relevant counties were missing water contaminant estimates when either (a) we did not identify any CWSs that served this ZCTA (residents in these areas may be exclusively served by transient or non-transient non-community water systems, exclusively served by private wells, or served by CWSs that did not submit data to the USEPA’s Six Year Review 3), or (b) the CWSs which were identified as serving these ZCTAs did not report relevant contaminant routine compliance monitoring records to the Six Year Review 3. For example, the CWS TN0000450 (Memphis Light, Gas, & Water) was assigned to 33 ZCTAs. Because TN0000450 did not report routine compliance monitoring records for arsenic to the Six Year Review 3, many of these ZCTAs are missing arsenic concentration estimates. Supplementary Table 1 presents overall and state-specific findings for the percentage of ZCTAs with CWS contaminant estimates, the mean and range of CWSs per ZCTA, and the total population served by all ZCTAs with CWS contaminant estimates. To assess CWS variability within ZCTAs and assess the potential for measurement error, we evaluated arsenic as a case study. We mapped population-weighted standard deviation values and calculated the number of ZCTAs served by multiple CWSs with arsenic concentration differences greater than the overall arsenic standard deviation.

ZCTA-level sociodemographic variables

We followed a previously developed conceptual model when evaluating sociodemographic inequities in water contaminants at the ZCTA-level (Supplementary Fig. 4) [8]. We downloaded ZCTA-level sociodemographic characteristics from the 2010 decennial US Census via the tidycensus package, including: total population, population density, and the proportion of residents who identify as non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaskan Native [48]. We additionally downloaded the following variables from the 2006–2010 US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey 5-year dataset (2006–2010) that were not available in the decennial Census: median household income; proportion of residents living below 150% of the federal poverty line; proportion of adults aged 25–64 without a high school diploma; the proportion of households receiving supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) benefits; proportion of residents who were children; proportion of residents who were foreign-born; and proportion of residents who reported speaking English “less than very well.” We further categorized ZCTAs as rural or urban using the 2010 US Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban (RUCA) continuum codes [49]. Rural ZCTAs were defined as those in non-metropolitan areas and include micropolitan areas, small towns, and rural areas (RUCA codes 4 through 10).

Statistical analysis

We first mapped population-weighted, average ZCTA-level concentrations for each contaminant across the study area using the tigris package [50]. We next summarized the distribution (range, 75th and 95th percentiles, arithmetic mean, and geometric mean) of population-weighted, average ZCTA-level concentrations for each contaminant. We also determined the frequencies and percentages of ZCTAs with concentrations exceeding the current USEPA MCL value and health-protective thresholds. Because USEPA is mandated to consider cost, technical feasibility, and health benefit when setting MCLs, MCLs often exceed health advisory levels that are based solely on health impact (e.g., USEPA MCL goals) [51]. Therefore, we selected health protective thresholds to represent the most health-protective standard, guideline, or advisory level set by a governing body or agency (e.g., USEPA maximum contaminant level goal, World Health Organization (WHO) Guidance level, regulatory standard) that could be reliably detected during the compliance monitoring period (≥ the minimum reporting level set by USEPA) (Table 1). When the most health-protective threshold was less than the minimum reporting level set by the USEPA (i.e. the MCL goal is zero for arsenic and uranium), we used the next most health-protective threshold. We selected the following values as health protective thresholds: 1 μg/L for arsenic, reflecting the regulatory standard for the Netherlands (1 μg/L) [52], the USEPA MCL goal of zero [51], and the USEPA minimum reporting limit of 1 μg/L [53]; 1300 µg/L for barium, the current WHO Guidance level [54]; 50 µg/L for chromium, the current WHO Guidance level [54]; 700 µg/L for fluoride, the optimal concentration recommended by the US Public Health Service [55]; 40 µg/L for selenium, the current WHO Guidance level [54]; 2 µg/L for uranium, reflecting a previous WHO Guidance level [56] and the USEPA MCL goal of zero [51]; 13 µg/L for trihalomethanes, reflecting the sum of the USEPA MCL goals for the four trihalomethanes [51] (although, several nations including New Zealand, South Africa, and Nigeria set a MCL of 1 µg/L) [57]; 9 µg/L for haloacetic acids, reflecting the sum of the USEPA MCL goals for the five haloacetic acids [51]. We did not establish a health-protective threshold for nitrite and nitrate as we were unable to find a MCL, MCL goal, or WHO Guidance level lower than the current USEPA MCL for both contaminants. We constructed raincloud plots to display the full distribution for each contaminant alongside the current USEPA MCL and the most health protective threshold [58]. To aid cohorts in determining the distribution of contaminants within cohort-specific states and regions, we present these distributions stratified by state (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3) and US region (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3). Because the occurrence of some disinfection byproducts are heavily influenced by temporal changes, we stratified our raincloud plots by season (Fall = October-December; Winter = January-March; Spring = April-June; Summer = July-September) [59]. These season periods align with USEPA’s quarterly compliance monitoring schedule for disinfection byproducts [60].

Spatial lag linear regression

We next evaluated potential sociodemographic inequities in ZCTA contaminant concentrations. For these analyses, we focused on arsenic, uranium, fluoride, total trihalomethanes, and total haloacetic acids because concentrations of these contaminants exceeded the health-protective threshold while nitrate, nitrite, barium, chromium, and selenium did not (effect estimates for these other contaminants are reported in Supplementary Table 5). First, we compared sociodemographic characteristics for all ZCTAs in our analysis to ZCTAs with contaminant concentrations exceeding the most health-protective threshold. We then evaluated the association between ZCTA racial/ethnic composition and socioeconomic disadvantage with contaminant concentrations in spatial lag linear regression models using the spatialreg R package to account for spatial dependence. We selected spatial lag models over spatial error models because the multiplier diagnostics function (lm.LMtest) indicated that model estimates were larger for spatial lag models [61]. We used k-nearest neighbor distance-based weights, with neighbors defined as ZCTAs with boundaries within 20 km of each ZCTA centroid. We evaluated inequities by socioeconomic status independent of racial/ethnic composition, and by racial/ethnic composition independent of socioeconomic status. To assess the association between racial/ethnic composition and contaminants, we assessed the geometric mean ratio (GMR) and corresponding percent difference of CWS contaminant concentrations per 10% higher proportion of residents classified as non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaskan Native. We ran analyses for each racial/ethnic group separately. For each analysis, we excluded ZCTAs with less than 100 residents in the racial/ethnic group of interest to ensure model stability. Because racial/ethnic composition sums to 100%, we used a “leave-one-out” modeling approach and adjusted for the proportion of residents in racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic White to ensure interpretable effect estimates that aligned with our conceptual model (Supplementary Fig. 4). Effect estimates are interpreted as associations for higher proportions of residents in one racial/ethnic group specifically because the proportion of non-Hispanic White residents is lower.

In selecting other covariates, we followed a previously developed conceptual model to estimate associations for racial/ethnic composition adjusting for socioeconomic disadvantage, and vice-versa [8]. Model 1 was adjusted for population density, proportion of adults without a high school diploma, median household income, rural vs. urban location, and racial/ethnic composition of all groups other than non-Hispanic White residents. For models evaluating higher proportions of non-Hispanic White residents, models leave out the proportion of Hispanic/Latino residents because this was the next most populous group. To assess the association between socioeconomic disadvantage and CWS contaminants, we assessed the GMR and corresponding percent difference of CWS contaminant concentrations per higher value corresponding to the interquartile range (IQR). Fully adjusted models (Model 2) were adjusted for population density, rural vs. urban location, and racial/ethnic composition of all groups. Following our conceptual diagrams from prior work, models evaluating median household income further adjust for the proportion of adults without a high school diploma, and models for all other socioeconomic disadvantage metrics adjust for median household income [8]. Following best practice, we considered the direction, magnitude, and precision of the effect estimates rather than relying solely on p-values when interpreting these effect estimates [62, 63].

Sensitivity analyses

To assess potential differences in final CWS contaminant concentrations across states with and without a published distribution boundary shapefile, we selected 19 ZCTAs from states with boundary shapefiles available and re-assigned CWSs to ZCTAs, using the US Census 2010 ZCTA to Place Relationship File and USPS ZIP to Locale file. We found no systematic differences in final population-weighted, ZCTA-level contaminant concentrations by analyzing Bland-Altman/Tukey mean difference plots and Spearman correlation coefficients across these approaches (rho = 0.99 for 2006–2011 arsenic, rho = 0.86 for 2000–2011 uranium, rho = 0.93 for 2006–2011 total trihalomethanes, rho = 0.99 for 2006–2011 haloacetic acids, Supplementary Fig. 5). However, we did observe that some CWSs were not represented in the service area boundary file but could be matched to ZCTAs via system name and city-served (Supplementary Fig. 5). We further re-evaluated spatial lag regression models with neighbors defined as ZCTAs within 40 km of each other to determine how robust findings were to more generous neighbor definitions (given that CWSs vary greatly in distribution area size). For models evaluating the association between racial/ethnic composition and contaminants, we additionally evaluated associations per higher proportion of residents in each racial/ethnic group that corresponded to the standard deviation for each racial/ethnic group (rather than a 10% higher value). Finally, we assessed whether associations between sociodemographic characteristics and contaminant concentrations were robust when considering alternative adjustments for socioeconomic disadvantage.

Results

We generated contaminant concentrations for 7,640 ZCTAs relevant to 34 observational ECHO cohort sites (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). CWSs serving these ZCTAs served a total of approximately 179 million people. The median number of CWSs assigned to a ZCTA was 2. Among ZCTAs served by more than 1 CWS (n = 4634 out of 7401 ZCTAs total with arsenic), the number with arsenic concentration differences exceeding 2.88 µg/L (the overall ZCTA-level standard deviation) was n = 1141 (~25%) (Supplementary Table 1). Within-ZCTA standard deviations of arsenic were highest in ZCTAs with higher mean arsenic concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 1). For each of the contaminants assessed, the total number of ZCTAs with reported contaminant concentrations ranged from 7401 (96.9%, arsenic) to 2,937 (38.4%, nitrite) (Table 1). Concentrations ranged from undetectable to 62.59 μg/L (arsenic), 35,504.43 μg/L (barium), 244.85 μg/L (chromium), 5729 μg/L (fluoride), 9372 μg/L (nitrate), 1000.00 μg/L (nitrite), 24.21 μg/L (selenium), 151.79 μg/L (uranium), 189.1 μg/L (total trihalomethanes), and 1000.0 μg/L (haloacetic acids). Distributions for arsenic, chromium, selenium, and uranium were right-skewed; distributions for fluoride, nitrate, total trihalomethanes, and haloacetic acids were left-skewed; distributions for nitrite and barium were bimodal (Fig. 1). Contaminants were frequently measured below the limit of detection (Fig. 1). ZCTAs were most likely to exceed the USEPA MCL for arsenic (1.4%), and most likely to exceed the health-protective threshold for total trihalomethanes (64.0%), haloacetic acids (56.4%), and arsenic (36.2%). Nitrate and nitrite levels did not exceed the USEPA MCL (Table 1, Fig. 1).

All concentration estimates are based on average community water system (CWS) contaminant concentrations of finished water distributed to consumers, which were previously published and derived from routine compliance monitoring records compiled by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) for the third Six Year Review period (2006-2011; estimates for uranium are from 2000-2011 to coincide with the Radionuclides Rule compliance monitoring requirements). Filled polygons represent density plots. Box plot upper, middle, and lower hinges correspond to the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, respectively. The average contaminant concentration for each CWS is represented by the outlined white circle; mean (standard deviation) is also listed for each contaminant in Table 1. The contaminant-specific maximum contaminant level is indicated by the red solid line. The most health protective threshold is indicated by the green dashed line. A Inorganics: For nitrate and nitrite, the health-protective threshold is the same as the maximum contaminant level. B Disinfection byproducts: seasonal time periods correspond to the USEPA’s quarterly compliance monitoring schedule for disinfection byproducts: Winter = January-March; Spring = April-June; Summer = July-September; Fall = October-December.

For disinfection byproducts, contaminant concentrations and exceedances of regulatory standards and health-protective thresholds differed by season. The number of ZCTAs exceeding the health-protective threshold for total trihalomethanes (9) was lowest in the winter and the number of ZCTAs exceeding the MCL for haloacetic acids (6) was lowest in the fall. The distribution of total trihalomethanes slightly shifted towards higher concentrations and more exceedances (220) during the summer monitoring period. (Fig. 1). Concentrations were most variable in the summer and least variable in the winter (Supplementary Fig. 6). We did not observe changes in the distribution of either disinfection byproduct by year (Supplementary Fig. 6).

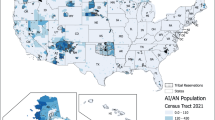

We observed regional variability in contaminant concentrations across the US (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3). Contaminant concentrations were highest in the Central Midwest for nitrate, nitrite, and barium, in the Southwest for arsenic and uranium, in the Eastern Midwest for fluoride, and in New England for chromium and selenium. Very few ZCTAs in the Pacific Northwest reported nitrite concentrations, potentially because CWSs can measure total nitrate and nitrite concentrations to comply with nitrate monitoring requirements (Supplementary Fig. 2). For disinfection byproducts, contaminant concentrations were highest in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast for both total haloacetic acids and total trihalomethanes (Supplementary Fig. 3). By state, mean contaminant concentrations were highest for arsenic in Iowa (8.59 µg/L, above the health protective threshold), for uranium in Utah (9.90 µg/L, above the health protective threshold), for fluoride in Minnesota (1,014 µg/L, above the health protective threshold), for nitrate in New Jersey (2663 µg/L), for nitrite in Utah (112.75 µg/L), for barium in New York (162.08 µg/L), for chromium in Arizona (6.28 µg/L), for selenium in North Dakota (3.73 µg/L), for total trihalomethanes in Kentucky (43.2 µg/L, above the health protective threshold), and for total haloacetic acids in Kentucky (34.6 µg/L, above the health protective threshold) (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3).

A Arsenic 2006–2011; B uranium 2000–2011; C nitrate 2006–2011; D fluoride 2006–2011; E total trihalomethanes 2006–2011, and F total haloacetic acids 2006–2011. All concentration estimates are based on average community water system (CWS) contaminant concentrations of finished water distributed to consumers, which were previously published and derived from routine compliance monitoring records compiled by United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) for the third Six Year Review period (2006–2011; estimates for uranium are from 2000–2011 to coincide with the Radionuclides Rule compliance monitoring requirements). For all contaminants, the highest concentration category corresponds to the current USEPA maximum contaminant level, and the other three categories correspond to cut-points that might be considered for future regulatory decisions.

The number of ZCTAs exceeding the health-protective threshold during the 2006–2011 period was 2678 (arsenic), 1412 (uranium, 2000–2011), 731 (fluoride), 3,584 (total trihalomethanes), and 2788 (haloacetic acids) (Table 2). Compared to all ZCTAs, ZCTAs exceeding the disinfection byproduct health protective threshold had higher population density and were less likely to be rural. For uranium, ZCTAs with contaminant concentrations exceeding the health-protective threshold had a higher percentage of Hispanic/Latino residents, a higher percentage of foreign-born residents, and a lower percentage of non-Hispanic White residents. ZCTAs exceeding the arsenic health protective threshold had higher average contaminant concentrations for uranium and fluoride than all ZCTAs.

Table 3 presents fully adjusted GMRs and corresponding percent differences in ZCTA contaminant concentrations per a 10% higher proportion of residents belonging to each racial/ethnic group and per IQR higher value for measures of socioeconomic disadvantage. In fully adjusted models, a 10% higher proportion of American Indian/Alaskan Native residents was associated with higher arsenic (11%, 95% CI 7%, 15%) and uranium (15%, 95% CI 10%, 21%) concentrations. A higher proportion of Hispanic/Latino residents was also associated with higher uranium (9%, 95% CI 6%, 12%) concentrations. Higher proportions of non-Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Hispanic/Latino residents were associated with higher fluoride concentrations (6%, 95% CI 1%, 11%; 35%, 95% CI 20%, 52%; and 21%, 95% CI 13%, 28%, respectively). In contrast, a higher proportion of non-Hispanic White residents was associated with lower concentrations of uranium (−8%, 95% CI −10%, −5%) and fluoride (−22%, 95% CI −26%, −17%), as well as lower arsenic concentrations and higher concentrations of total trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids (although these effect estimates were small in magnitude). A higher proportion of Hispanic/Latino residents was also associated with lower disinfection byproducts concentrations (−5%, 95% CI −8%, −1%; for total trihalomethanes, and −4%, 95% CI −6%, −1% for haloacetic acids). A higher proportion of residents living below 150% of the federal poverty line was associated with higher uranium (7%, 95% CI 0%, 14%), and fluoride (16%, 95% CI −1%, 36%) concentrations. In contrast, a higher proportion of adults without a high school diploma was associated with lower fluoride (−21%, 95% CI −29%, −11%) concentrations. A higher percentage of residents receiving SNAP was associated with lower uranium (−8%, 95% CI −12%, −4%) and fluoride (−10%, 95% CI −19%, 0%) concentrations. Median household income was not associated with contaminant concentrations.

In sensitivity analyses, model results were similar when considering neighbor weight matrices using 40 km distances, further adjustment for the proportion of households receiving supplemental nutrition assistance, further adjustment for the proportion of residents below 150% of the federal poverty line, and for models evaluating a higher proportion of residents in each racial/ethnic group corresponding to the standard deviation (Supplementary Table 4). For additional analyses evaluating barium, chromium, selenium, nitrate, and nitrite, we found positive associations between (a) higher proportions of American Indian/Alaskan Native residents with higher barium, selenium, and nitrate concentrations, (b) higher proportions of Hispanic/Latino residents with higher chromium and nitrite concentrations, (c) higher proportions of non-Hispanic White residents with lower chromium and nitrate concentrations, (d) and higher proportions of non-Hispanic Asian residents with lower barium concentrations (Supplementary Table 5). Effect estimates for higher proportions of American Indian/Alaskan Native residents and barium and nitrate were the largest in magnitude.

Discussion

We present novel estimates of regulated public drinking water contaminants from 2006-2011 in ZCTAs relevant for observational ECHO birth cohort sites. We find substantial regional variability in estimated contaminant concentrations, a high number and percentage of ZCTAs with contaminant concentrations exceeding the most health-protective thresholds, and significant sociodemographic inequities at the ZCTA-level that mirror and expand upon prior findings at the CWS and county-level. These findings indicate that prenatal public drinking water exposure differs meaningfully across the ECHO Cohort, and exposure estimates can be leveraged in future epidemiologic studies to generate individual-level, time-weighted exposure estimates and evaluate associations with relevant pregnancy outcomes, birth outcomes, and other relevant outcomes across the lifespan.

Federally regulated public water contaminants differ greatly in their source profiles and associated health impacts [7]. Contaminants may be geogenic and present in source water (e.g., arsenic, uranium, fluoride), released via anthropogenic activity (e.g., nitrate), added by utilities as a public health measure (e.g., fluoride, disinfectants), generated as a consequence of disinfection (e.g., disinfection byproducts), or released from water system infrastructure (e.g., lead, copper). Epidemiologic evidence for relevant birth outcomes is often limited to cohorts with estimated or measured water contaminants, to studies of relatively high exposure levels that are not common in the US, or to biomarker studies that may introduce reverse causality concerns when exposure influences kidney function and excretion [64, 65]. The ECHO Cohort represents an excellent opportunity to fill in many of these research gaps.

The ZCTAs analyzed in the current study are not representative of all ZCTAs nationwide (for example, only 15% of ECHO Cohort ZCTAs were categorized as rural, compared to 40% nationwide) [66]. Still, our findings largely mirror those of prior analyses at the CWS and county-level identifying nationwide inequities by race and ethnicity [2, 8]. We find that disinfection byproducts measured in drinking water are not associated with sociodemographic characteristics, which is consistent with a study conducted in Spain [67]. Also, higher proportions of Hispanic/Latino and American Indian/Alaskan Native residents are associated with higher inorganic contaminant (arsenic, uranium, fluoride) concentrations, specifically because the proportions of non-Hispanic White residents are lower. We did find, however, that higher proportions of non-Hispanic Black residents are associated with higher fluoride concentrations, which conflicts with a recent nationwide county-level analysis that observed a null association [2]. These conflicting results may be explained by the geographic distribution and urbanicity of ECHO Cohort participants. ECHO Cohort participants are largely from urban areas, and the current study included very few ZCTAs in the Southeastern US where the proportion of non-Hispanic Black residents is high relative to the rest of the US [66]. Prior studies support that racial inequities in public water contaminants are more likely or extreme in areas where there is a higher proportion of marginalized residents and adequate variability in the contaminant of interest [8]. Thus, our current findings support prior evidence that nationwide studies may mask inequities occurring within regions or individual states. Future studies in the ECHO Cohort can evaluate participant-level sociodemographic inequities in estimated exposures (including potential non-linear associations) and determine if well-documented disparities in relevant adverse outcomes are explained by these observed inequities in public water contaminants [3, 8, 68].

Our analysis has several limitations. First, because we did not have access to participant ZIP Codes, it is possible that our current estimates do not include some ECHO Cohort participants. Although ECHO Data Analysis Center analysts (authors AMK, MB) have access to participant ZIP Codes and can merge in ZCTA-level water estimates, they were unable to provide these ZIP Codes to the other study authors to generate estimates for this study. We therefore aimed to generate contaminant estimates for all ZCTAs which could be relevant for observational ECHO Cohort sites with pregnant participants. Because our analysis was focused on generating public water system contaminant concentrations that could be readily assigned to participants based on residential address, we did not generate estimates for ZCTAs reliant on private wells or water hauling, and therefore excluded some cohort sites in rural areas. Epidemiologic analyses utilizing these estimates can restrict to participants who reported a public water system as their tap water source. Participants reliant on a public well at home may still consume public drinking water from secondary and tertiary sources (e.g., school, work). Additionally, we were not able to account for the number of ECHO participants within each ZCTA and, although it is likely that more ECHO participants lived in some ZCTAs than others, each ZCTA was equally weighted in our analyses. We previously validated these population-weighted, average ZCTA-level concentrations of arsenic and uranium in multi-site urban (the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) and multi-site rural (the Strong Heart Family Study) cohorts [4]. Even when water concentrations were below USEPA MCLs, ZCTA-level estimates were statistically associated with urinary arsenic and uranium biomarkers reflecting total internal dose and explained a higher proportion of variability in biomarker concentrations than previously estimated (~31-60% in urban areas). However, for other contaminants, the contribution of public drinking water to total exposures is not yet clear for US communities because (a) regulated public water contaminants differ greatly by source profile and metabolic transformation and elimination, (b) communities differ in their drinking water sources and use of treatment devices, especially by socioeconomic advantage, and (c) contributions from non-drinking water sources differ greatly by contaminant (e.g., dermal and inhalation exposure for disinfection byproducts, dust and paint exposure for lead, food for nitrates) [7, 69, 70].

However, it is not currently clear if assigning residential ZCTA-level estimates (rather than CWS-level or county-level, for example) is the best approach to estimating actual public water contaminant exposures. Assigning CWS-level estimates is only feasible for participants in the 15 ECHO states that publish CWS distribution boundaries. Assigning ZCTA-level estimates assumes that participants consume public water within their residential ZCTAs only, and this may not accurately reflect secondary and tertiary drinking water sources, such as those at places of work, school, worship, and recreation. Due to differences in ZCTA size, and frequent transit between ZCTAs, the accuracy in assignment may be differential by rural-urban status, and power may be limited for analyses across rural-urban locations. A quarter of ZCTAs served by multiple CWSs had CWS arsenic concentration differences greater than the overall standard deviation, highlighting that nearby water systems may distribute water with meaningfully different contaminant concentrations. ZCTA-level estimates will introduce some measurement error relative to assigning individual residential water system estimates, although this remains poorly quantified and is a critical area for further research. These findings further support the critical need for higher resolution public water system distribution area shapefiles to facilitate the assignment of water-system level estimates for the entire US. These assumptions should be evaluated in further high-quality studies to improve exposure estimation and assignment. To our knowledge, no relevant ECHO cohort sites collected address information at places of secondary and tertiary drinking water consumption that could be leveraged to generate more accurate exposure estimates. An advantage of our current approach is that ZCTA-level estimates can be readily assigned based on residential addresses across diverse cohorts. In addition, exposure measurement error may be largest at the extremes of the distribution; some laboratories might have rounded values to the nearest whole numbers, especially when values are at the highest end of the quantifiable range.

Because only 15 states publish high-quality public water system distribution boundaries, we relied on two distinct approaches to assign CWSs to ZCTAs: (a) overlapping boundary shapefiles for 15 states and (b) assignments made via the USPS ZIP to Locale and US Census Place Relationship files. Although we did not observe systematic differences in contaminant concentrations when comparing these two methods, we did observe that many active CWS were missing from service area shapefiles, yet could be matched to ZCTAs via city-served and water system name. This approach could have introduced differential measurement error by state, and thus, by contaminant concentration. Sensitivity analyses could be restricted to participants living in states that do publish boundary shapefiles, where primary residential water systems can be assigned; ZCTA-level averages can still be incorporated to account for secondary and tertiary sources. It is not clear if either approach more accurately estimates actual contaminant concentrations at the ZCTA- or individual-level. Currently, all US public drinking water epidemiology is limited by the lack of high-quality, nationwide shapefiles of public water system distribution boundaries [37]. Moreover, the accuracy of published shapefiles is not clear and likely differs by the entity with enforcement responsibility [37]. To aid in efforts to replace all lead service lines across the US, the USEPA Lead and Copper Rule Revisions now require public water systems to create and maintain an inventory of service line material by October 2024 [71]. Similarly, requiring public water systems to generate, maintain, and publicly publish public water system boundaries would significantly advance public water epidemiology and policy analyses across the US. As more data is collected, future epidemiologic analyses would benefit from accounting for the uncertainty in estimates of ZCTA-level contaminant concentrations.

Although we have developed ZCTA-level lead and copper concentration estimates, we did not include these in the current study, as these estimates may not be reasonable estimates of CWS exposure when assigned at either the CWS or ZCTA-level. Lead is rarely present in source water and instead enters drinking water from distribution system components (e.g., lead solder or plumbing and service lines) [72]. Our lead concentration estimates were derived from compliance monitoring records reported in accordance with the Lead and Copper Rule and represented the 90th percentile value of concentrations sampled at the tap for a small subset of homes. Prior studies have identified inadequacies and biases in the Lead and Copper Rule compliance monitoring and reporting requirements, and there is substantial variability in water lead concentrations throughout water system distribution systems and across seasons [30, 72]. Future studies should specifically evaluate these lead 90th percentile concentration estimates in the ECHO Cohorts and determine whether they are associated with blood lead concentrations (validated measure of internal dose) when assigned at the water system or ZCTA level. Similarly, there is meaningful variability in disinfection byproduct concentrations within water distribution systems, that likely warrant many spatial samples within a CWS or modeling effort to capture continued DBP degradation and formation over time and space [7]. Disinfection byproduct concentrations are influenced by the disinfectant type, residence time, season/temperature, occurrence and type of organic matter [59, 73]. Our water system and ZCTA-level estimates of total trihalomethanes and total haloacetic acids are not able to account for differences in concentrations within distribution systems that are related to residence time. Seasonal estimates of disinfection byproduct concentrations may not sufficiently capture acute changes in contaminant concentrations. In addition, we relied on the most recently published compliance monitoring records published in the Six Year Review 3 (2006–2011), which does not overlap with all prenatal time periods in the ECHO Cohort. Contaminant concentrations can be updated when the USEPA releases the Six Year Review 4 (covering 2012–2019). While most geogenic contaminants are considered to be relatively stable over time, changes in contaminant concentrations are more likely for contaminants subject to temporal variability or a major regulatory change (we are not aware of any major federal regulatory changes that would reduce contaminant concentrations from 2011–2019).

Despite these limitations, this work enables the study of federally regulated public drinking water contaminant exposures within the ECHO Cohort and provides an opportunity to evaluate CWS contaminant exposures with infant and child health outcomes. We propose that public drinking water contaminant estimates should be regularly included as part of a comprehensive assessment of environmental exposures in major National Institute of Health (NIH)-funded cohorts. Modeled estimates of PM2.5 and other air pollutants are routinely estimated for cohort participants, and epidemiologic evidence using these modeled exposures was cited by the USEPA in the Agency’s proposed decision to revise the annual PM2.5 standard from 12.0 µg/m3 to 9.0–10.0 µg/m3 [74, 75]. While the exposure estimates we generate here can be improved with the additional methodological advances proposed above, estimates can support critical epidemiologic assessments, especially for contaminants with a MCL, action level, or trigger level above the maximum contaminant goal level (e.g., arsenic, uranium, lead, and disinfection byproducts). High-quality, nationwide epidemiologic studies of CWS contaminant exposures and adverse birth and infant outcomes are needed in large, diverse US populations. Major maternal and infant health disparities persist, and inequities in public drinking water contaminant exposures might be an under-recognized and immediately modifiable driver of these disparities.

Data availability

All data used in this analysis are publicly available. The CWS concentration data are available at: https://msph.shinyapps.io/drinking-water-dashboard/. Citations for shapefiles used to generate ZCTA-level data are available in Supplementary Table 1. ZCTA-level racial/ethnic composition and ZCTA-level sociodemographic data are available from the 2010 decennial US Census and the 2006-2010 US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (5-year estimates). The 2010 US Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban (RUCA) continuum codes are also publicly available. A full description of all variables used in this analysis is listed in the Methods. ZCTA-level public water contaminant estimate data are available from the authors upon request.

References

Nigra AE, Chen Q, Chillrud SN, Wang L, Harvey D, Mailloux B, et al. Inequalities in public water arsenic concentrations in counties and community water systems across the United States, 2006–2011. Environ Health Perspect. 2020;128:127001 https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP7313.

Hefferon R, Goin DE, Sarnat JA, Nigra AE Regional and racial/ethnic inequalities in public drinking water fluoride concentrations across the US. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2023:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-023-00570-w.

Danziger J, Mukamal KJ, Weinhandl E. Associations of community water lead concentrations with hemoglobin concentrations and Erythropoietin-stimulating agent use among patients with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:2425–34. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020091281.

Spaur M, Glabonjat RA, Schilling K, Lombard MA, Galvez-Fernandez M, Lieberman-Cribbin W, et al. Contribution of arsenic and uranium in private wells and community water systems to urinary biomarkers in US adults: The Strong Heart Study and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-023-00586-2.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Report on the Environment (ROE). US EPA. 2015. URL: https://cfpub.epa.gov/roe/indicator.cfm?i=45 (Accessed 12 November 2023).

Ravalli F, Yu Y, Bostick BC, Chillrud SN, Schilling K, Basu A, et al. Sociodemographic inequalities in uranium and other metals in community water systems across the USA, 2006-11: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6:e320–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00043-2.

Levin R, Villanueva CM, Beene D, Cradock AL, Donat-Vargas C, Lewis J, et al. US drinking water quality: exposure risk profiles for seven legacy and emerging contaminants. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2023:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-023-00597-z.

Martinez-Morata I, Bostick BC, Conroy-Ben O, Duncan DT, Jones MR, Spaur M, et al. Nationwide geospatial analysis of county racial and ethnic composition and public drinking water arsenic and uranium. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7461. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35185-6.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works — racist policies as a root cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities. N. Engl J Med. 2021;384:768–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2025396.

Scanlon BR, Reedy RC, Fakhreddine S, Yang Q, Pierce G. Drinking water quality and social vulnerability linkages at the system level in the United States. Environ Res Lett. 2023;18:094039. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ace2d9.

Adkins-Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey ZD, Ponce NA. Measuring structural racism: a guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191:539–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab239.

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511.

Nardone AL, Casey JA, Rudolph KE, Karasek D, Mujahid M, Morello-Frosch R. Associations between historical redlining and birth outcomes from 2006 through 2015 in California. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237241.

Kwate NOA, Goodman MS. Cross-sectional and longitudinal effects of racism on mental health among residents of black neighborhoods in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:711–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302243.

Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1370–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370.

Chae DH, Clouston S, Martz CD, Hatzenbuehler ML, Cooper HLF, Turpin R, et al. Area racism and birth outcomes among Blacks in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.019.

Collins JW, David RJ, Symons R, Handler A, Wall SN, Dwyer L. Low-income African-American mothers’ perception of exposure to racial discrimination and infant birth weight. Epidemiology. 2000;11:337–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200005000-00019.

Howell EA, Janevic T, Blum J, Zeitlin J, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, et al. Double disadvantage in delivery hospital for Black and Hispanic women and high-risk infants. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24:687–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-02911-9.

Travers CP, Carlo WA, McDonald SA, Das A, Ambalavanan N, Bell EF, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities among extremely preterm infants in the United States From 2002 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e206757. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6757.

Behrman RE, Butler AS Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; (2007).

Taylor CM, Golding J, Emond AM. Adverse effects of maternal lead levels on birth outcomes in the ALSPAC study: a prospective birth cohort study. BJOG. 2015;122:322–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12756.

Bellavia A, Zota AR, Valeri L, James-Todd T. Multiple mediators approach to study environmental chemicals as determinants of health disparities. Environ Epidemiol. 2018;2:e015. https://doi.org/10.1097/EE9.0000000000000015.

Pace C, Balazs C, Bangia K, Depsky N, Renteria A, Morello-Frosch R, et al. Inequities in drinking water quality among domestic well communities and community water systems, California, 2011‒2019. Am J Public Health. 2022;112:88–97. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306561.

Schaider LA, Swetschinski L, Campbell C, Rudel RA. Environmental justice and drinking water quality: are there socioeconomic disparities in nitrate levels in U.S. drinking water? Environ Health. 2019;18:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0442-6.

Nigra AE, Navas-Acien A. Arsenic in US correctional facility drinking water, 2006-2011. Environ Res. 2020;188:109768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109768.

Balazs CL, Ray I. The drinking water disparities framework: on the origins and persistence of inequities in exposure. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:603–11. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301664.

Cory DC, Rahman T. Environmental justice and enforcement of the Safe Drinking Water Act: The Arizona arsenic experience. Ecol Econ. 2009;68:1825–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.12.010.

Gibson JM, Fisher M, Clonch A, MacDonald JM, Cook PJ. Children drinking private well water have higher blood lead than those with city water. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002729117.

Kaplan RA. Memorandum: Region 5’s experience in implementation of the Lead and Copper Rule. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Updated December 29, 2017. URL: https://www.eenews.net/assets/2020/02/20/document_gw_09.pdf (Accessed 20 July 2020).

Hernández D. Sacrifice along the energy continuum: a call for energy justice. Environ Justice. 2015;8:151–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2015.0015.

Wilson SM. Environmental justice movement: a review of history, research, and public health issues. J Public Manag Soc Policy. 2010;16:19–50.

Milton AH, Hussain S, Akter S, Rahman M, Mouly TA, Mitchell K. A review of the effects of chronic arsenic exposure on adverse pregnancy outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060556.

Lin L, St Clair S, Gamble GD, Crowther CA, Dixon L, Bloomfield FH, et al. Nitrate contamination in drinking water and adverse reproductive and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13:563. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27345-x.

Cao W-C, Zeng Q, Luo Y, Chen H-X, Miao D-Y, Li L, et al. Blood biomarkers of late pregnancy exposure to Trihalomethanes in drinking water and fetal growth measures and gestational age in a Chinese cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:536–41. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1409234.

Choi AL, Sun G, Zhang Y, Grandjean P. Developmental fluoride neurotoxicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1362–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104912.

McDonald YJ, Anderson KM, Caballero MD, Ding KJ, Fisher DH, Morkel CP, et al. A systematic review of geospatial representation of United States community water systems. AWWA Water Sci. 2022;4:e1266. https://doi.org/10.1002/aws2.1266.

Bravo MA, Fuentes M, Zhang Y, Burr MJ, Bell ML. Comparison of exposure estimation methods for air pollutants: Ambient monitoring data and regional air quality simulation. Environ Res. 2012;116:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2012.04.008.

Issah I, Duah MS, Arko-Mensah J, Bawua SA, Agyekum TP, Fobil JN. Exposure to metal mixtures and adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes: A systematic review. Sci Total Environ. 2024;908:168380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168380.

Bannon E, Spriggs R, Adkins-Jackson PB, Van Horne YO, Parks RM, Prins SJ, et al. Disinfection Byproducts and Inorganic Contaminants in Us Correctional Facility Public Water Systems. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4548551 (Accessed 30 November 2023).

Nigra AE, Cazacu-De Luca A, Navas-Acien A. Socioeconomic vulnerability and public water arsenic concentrations across the US. Environ Pollut. 2022;313:120113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120113.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The Analysis of Regulated Contaminant Occurrence Data from Public Water Systems in Support of the Third Six-Year Review of National Primary Drinking Water Regulations: Chemical Phase Rules and Radionuclides Rules. 2016. URL: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-12/documents/810r16014.pdf (Accessed 20 July 2023).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Six-Year Review 3 Compliance Monitoring Data (2006-2011). 2016. URL: https://www.epa.gov/dwsixyearreview/six-year-review-3-compliance-monitoring-data-2006-2011 (Accessed 13 November 2023).

Krasner SW, McGuire MJ, Jacangelo JG, Patania NL, Reagan KM, Aieta EM. The occurrence of disinfection by-products in US drinking water. J AWWA. 1989;81:41–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1551-8833.1989.tb03258.x.

United States Census Bureau. 2010 ZCTA to Place Relationship File. URL: https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/data/rel/zcta_place_rel_10.txt (Accessed 30 November 2023).

United States Postal Service. USPS ZIP Codes by Area and District codes. URL: https://postalpro.usps.com/ZIP_Locale_Detail (Accessed 30 November 2023).

Pebesma E. Simple features for R: Standardized support for spatial vector data. R J. 2018;10:439–46.

Walker K, Herman M, Eberwein K. tidycensus: Load US Census Boundary and Attribute Data as ‘tidyverse’ and ’sf’-Ready Data Frames (2023).

U.S. Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. 2020. URL: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/ (Accessed 13 November 2023).

Walker K. tigris: An R package to access and work with geographic data from the US Census Bureau. R J. 2016;8:231. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2016-043.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. 2015. URL: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations (Accessed 22 February 2024).

Ahmad A, van der Wens P, Baken K, de Waal L, Bhattacharya P, Stuyfzand P. Arsenic reduction to <1µg/L in Dutch drinking water. Environ Int. 2020;134:105253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105253.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The Final Arsenic Rule. URL: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2010-title40-vol22/pdf/CFR-2010-title40-vol22-sec141-23.pdf (Accessed 24 July 2023).

World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: Fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda. (2022).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Panel on Community Water Fluoridation. U.S. Public Health Service recommendation for fluoride concentration in drinking water for the prevention of dental caries. Public Health Rep. 2015;130:318–31.

Frisbie SH, Mitchell EJ, Sarkar B. World Health Organization increases its drinking-water guideline for uranium. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2013;15:1817–23. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3em00381g.

Villanueva CM, Evlampidou I, Ibrahim F, Donat-Vargas C, Valentin A, Tugulea A-M, et al. Global assessment of chemical quality of drinking water: The case of trihalomethanes. Water Res. 2023;230:119568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.119568.

Allen M, Poggiali D, Whitaker K, Marshall TR, van Langen J, Kievit RA. Raincloud plots: A multi-platform tool for robust data visualization. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:63. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15191.2.

Munthali E, Marcé R, Farré MJ. Drivers of variability in disinfection by-product formation potential in a chain of thermally stratified drinking water reservoirs. Environ Sci: Water Res Technol. 2022;8:968–80. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EW00788B.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Occurrence Assessment for the Final Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproducts Rule. 2005. URL: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P1005ED2.txt (Accessed 30 November 2023).

Florax RJGM, Nijkamp P. Misspecification in Linear Spatial Regression Models (2003) https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.459500.

Savitz DA, Wise LA, Bond JC, Hatch EE, Ncube CN, Wesselink AK, et al. Responding to reviewers and editors about statistical significance testing. Ann Intern Med (2024):M23-2430. https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-2430.

Farland LV, Correia KF, Wise LA, Williams PL, Ginsburg ES, Missmer SA. P -values and reproductive health: what can clinical researchers learn from the American Statistical Association? Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2406–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew192.

Jin R, Zhu X, Shrubsole MJ, Yu C, Xia Z, Dai Q. Associations of renal function with urinary excretion of metals: Evidence from NHANES 2003–2012. Environ Int. 2018;121:1355–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.002.

Verner M-A, Loccisano AE, Morken N-H, Yoon M, Wu H, McDougall R, et al. Associations of Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Lower Birth Weight: An Evaluation of Potential Confounding by Glomerular Filtration Rate Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model (PBPK). Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:1317–24. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408837.

Knapp EA, Kress AM, Parker CB, Page GP, McArthur K, Gachigi KK, et al. The Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO)-wide Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2023:kwad071. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwad071.

Castaño-Vinyals G, Cantor KP, Villanueva CM, Tardon A, Garcia-Closas R, Serra C, et al. Socioeconomic status and exposure to disinfection by-products in drinking water in Spain. Environ Health. 2011;10:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-10-18.

Casey JA, Daouda M, Babadi RS, Do V, Flores NM, Berzansky I, et al. Methods in public health environmental justice research: a scoping review from 2018 to 2021. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2023;10:312–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-023-00406-7.

Martinez-Morata I, Sobel M, Tellez-Plaza M, Navas-Acien A, Howe CG, Sanchez TR. A state-of-the-science review on metal biomarkers. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2023;10:215–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-023-00402-x.

Bryan NS, van Grinsven H. Chapter Three - The Role of Nitrate in Human Health. In: Sparks DL, editor. Advances in Agronomy, vol. 119. Academic Press; (2013). 153–82.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Lead and Copper Rule Revisions Service Line Inventory Guidance. 2022. URL: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/revised-lead-and-copper-rule (Accessed 12 December 2023).

Del Toral MA, Porter A, Schock MR. Detection and evaluation of elevated lead release from service lines: a field study. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:9300–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/es4003636.

Doederer K, Gernjak W, Weinberg HS, Farré MJ. Factors affecting the formation of disinfection by-products during chlorination and chloramination of secondary effluent for the production of high quality recycled water. Water Res. 2014;48:218–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.034.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Sacks J Supplement to the 2019 Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter. 2022. URL: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/isa/recordisplay.cfm?deid=354490 (Accessed 14 November 2023).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Proposes to Strengthen Air Quality Standards to Protect the Public from Harmful Effects of Soot. 2023. URL: https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-proposes-strengthen-air-quality-standards-protect-public-harmful-effects-soot (Accessed 14 November 2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the government agencies and all who worked to collect these data and make them available to the public.

Funding

This study was supported by the NIH OD and NIDCR grant DP5OD031849, NICHD grant P2CHD058486, NIEHS grants P30ES009089 and P42ES033719, NIH grant U24OD023382, and NIH HHS grant UG3OD023290. TRB is also supported by NIEHS T32ES007322. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TRB: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing (draft, review, and editing), validation, and visualization. MS: underlying methodology and data, contribution of code, and writing (review and editing). ICT: content knowledge and writing (review and editing). AMK & MB: subject matter expertise on the ECHO Cohort, analytical decisions, and writing (review and editing). AK: content knowledge, and writing (review and editing). JAC: methodology, content knowledge, and writing (review and editing). JBH: subject matter expertise on the ECHO Cohort as a cohort PI, methodology, and writing (review and editing). AEN: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing (draft, review, and editing), validation, visualization, obtained funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study did not use human participants, their data, or biological material and was therefore determined to be exempt from research by Columbia University’s Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bloomquist, T.R., Spaur, M., Cerna-Turoff, I. et al. Public drinking water contaminant estimates for birth cohorts in the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Cohort. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 36, 1–13 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-024-00699-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-024-00699-2