Abstract

NPM1-mutated (NPM1-mut) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is generally associated with a more favorable outcome, although the presence of additional gene mutations can influence patient prognosis. We analyzed intensively-treated adult NPM1-mut AML patients included in the HARMONY Alliance database. A newly developed risk classification, which included combinations of co-mutations in FLT3-ITD, DNMT3A, IDH1/IDH2, and TET2 genes, was applied to a training cohort of NPM1-mut AML patients included in clinical trials (n = 1001), an internal validation cohort more representative of real-world settings (n = 762), and an external validation cohort enrolled in UK-NCRI trials (n = 585). The HARMONY classification considered 51.8% of the NPM1-mut AML training cohort patients as favorable, 24.8% as intermediate, and 23.4% as adverse risk, with median overall survival (OS) of 14.4, 2.2, and 0.9 years, respectively; p < 0.001), thereby reclassifying 42.7% of NPM1-mut patients into a different European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 risk category. These results were confirmed both in an internal and external validation cohort. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) in first complete remission (CR1) showed the highest benefit in the NPM1-mut adverse-risk subgroup. The HARMONY classification provides the basis for a refined genetic risk stratification for adult NPM1-mut AML with potential clinical impact on allo-HSCT decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clinically heterogeneous disease, where genomic alterations provide crucial prognostic insights that inform clinical decision-making [1]. NPM1 mutations (NPM1-mut) have been described in approximately 30% of adult AML and define the largest disease subtype in younger adults, with distinct biologic and clinical features [2,3,4]. While the prognosis is generally considered favorable, a significant variability in outcomes has been reported. In fact, the vast majority of patients present several co-mutations that could influence the prognosis, such as FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD), which has been recognized as a deleterious mutation. However, for almost two decades FLT3-ITD is the only co-mutation that is considered for risk stratification in NPM1-mut AML in current guidelines [5, 6]. Accordingly, in the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 risk classification, patients with NPM1 mutations are categorized as favorable risk when FLT3-ITD is absent, but as intermediate risk when FLT3-ITD is also present [6]. Nevertheless, there are several other genes frequently co-mutated with NPM1 that might influence the prognosis of this AML subtype. For example, DNMT3A-mut is present in around 50% of NPM1-mut AML, and it has been associated with adverse outcomes in several studies [7,8,9,10,11], although others found contradictory results [12]. In fact, the prognostic impact of DNMT3A-mut seems to be modulated by the frequent co-mutation of FLT3-ITD [13, 14]. This “triple-mutated” AML (NPM1-mut, FLT3-ITD, and DNMT3A-mut) is a significant group as it represents approximately 25% of NPM1-mut AML. On the other hand, the relatively poor outcomes attributed to FLT3-ITD might be influenced by the frequent co-mutation with DNMT3A [15]. Additional gene mutations have been reported in NPM1-mut AML, although their prognostic impact remains unclear [16].

Cytogenetic aberrations are uncommon in this AML subtype, where a normal karyotype has been reported in 80-88% of the patients [17,18,19,20,21]. Most of them do not seem to affect the risk stratification, with the exception of infrequent (<3%) adverse cytogenetic abnormalities according to ELN2022 consensus [6, 22]. Moreover, an aberrant karyotype does not seem to influence the immunophenotype nor gene expression profile in NPM1-mut AML, whereas they could be related to concomitant gene mutations [15, 19, 23, 24].

Hence, this AML subtype is an ideal setting for analyzing complex gene-gene interactions and co-mutational patterns with potential prognostic implications.

In order to address these uncertainties, we analyzed a large cohort of patients with NPM1-mut AML included in the Healthcare Alliance for Resourceful Medicine Offensive against Neoplasms in Hematology (HARMONY) AML international database and validated the findings using both HARMONY real-world data as well as publicly available data.

Methods

Patients

The HARMONY Alliance AML database was used for this study, where only patients fulfilling the following criteria were selected: age >18 years at AML diagnosis, presence of NPM1-mut, treatment with intensive chemotherapy regimens, availability of cytogenetic study, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) myeloid panel data. Patients who received targeted therapies (e.g., FLT3 or IDH1/IDH2 inhibitors, anti-CD33 antibodies) or non-intensive treatment approaches were not included. Patients with class-defining cytogenetic abnormalities concomitant with NPM1-mut were excluded.

A total of 1763 NPM1-mut AML adult patients were selected for this analysis, contributed by eight European centers or cooperative groups. The training cohort comprised 1001 NPM1-mut patients from three prospective multicenter clinical trials of the German–Austrian AML Study Group (AMLHD98A, AML-HD98B, and AMLSG-07-04) and from three prospective multicenter clinical trials of HOVON-SAKK (HO102, HO103, HO132), representing a clinical trial setting [1, 25,26,27]. An internal validation cohort was formed with the remainder of patients, contributed by the Study Alliance Leukemia AML registry (Germany), the Munich Leukemia Laboratory (Germany), the AML Cooperative Group registry (Germany), the Swedish AML registry (Sweden), the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Spain), and the Queen’s University of Belfast (North Ireland), with a total of 762 NPM1-mut patients that were more representative of the “real-world” setting in Europe [28].

Patient data uploaded to the HARMONY Big Data Platform underwent a rigorous double brokerage pseudonymization process, adhering to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Subsequently, the data were harmonized and converted using the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model [29].

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the HARMONY steering committee and AML working group. The HARMONY research project underwent review and approval by the Medicinal Research Ethics Committee of the University of Salamanca (PI 2018 10 128). HARMONY has established an ethical and data-protection framework for the secondary use of data, including de facto anonymization. Prior written informed consent had been obtained from all patients at respective HARMONY partner institutions.

NPM1-mut risk stratification

A multi-step analysis of clinically significant gene co-mutations associated to NPM1-mut was performed. At each step, combinations of up to two additional genes (either mutated or wildtype) were explored. The 2-year overall survival (OS) for each combination was estimated using 100-fold bootstrap sampling and compared to the 2-year OS of NPM1 wildtype (-wt) patients in the same dataset (German–Austrian AML Study Group and HOVON-SAKK clinical trials, n = 2473). Gene mutation combinations that allowed patient reclassification into different risk categories were selected. The classification included only genes that were analyzed in both NGS panels of the training cohort (Table S1), provided that each gene mutation was found in at least 10 patients (≥1% of the cohort). While IDH2-R172K mutation has proven to be associated with distinct outcomes when compared to other IDH2-mut and IDH1-mut, it is also mutually exclusive to NPM1-mut and therefore rarely found in this AML subtype (Table S2) [11, 30]. Moreover, exploratory analyses demonstrated similar findings with IDH1-mut and IDH2-mut in NPM1-mut (Figs. S1 and S2), so they were combined as IDH-mut (any mutated) or IDH-wt (both wildtype) in the final risk classification. The HARMONY NPM1-mut classification was tested in the aforementioned internal validation cohort.

External validation dataset

An external validation was also performed, using the publicly available dataset published by Tazi et al., comprising AML adult patients enrolled in UK-NCRI trials (AML17, AML16, AML11, AML12, AML14, and AML15) who were not included in HARMONY at the time of the analysis [31]. Patients with NPM1-mut, treated intensively, with cytogenetic and NGS myeloid panel information, were selected for HARMONY classification validation. Of note, some of these patients received gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) or FLT3 inhibitor lestaurtinib in addition to intensive chemotherapy regimens, as part of AML17 randomizations.

Statistical analysis

Clinical endpoints were defined as recommended by international guidelines [6]. Composite complete remission (CRc) was defined as either complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi). OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between survival distributions were evaluated using the log-rank test. Patients who underwent allo-HSCT in first complete remission (CR1) were censored at transplant date for OS and RFS analyses in both the training and internal validation cohorts. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariable survival analysis, including clinically-significant variables as well as HARMONY NPM1-mut classification. Imputation was not performed for missing values. Co-occurrence and mutual exclusivity were tested for gene mutations present in at least 3% of patients, calculating q-value as previously reported [32]. The relative order in which mutations were acquired was inferred using the Bradley-Terry method, using pairwise comparisons of sex-corrected variant allele frequencies. All reported p-values were two-sided at the conventional 5% significance level. Analyses were performed using R statistical software (v3.6.3).

Results

Patient characteristics of AML training cohort

The training cohort of 1001 adult NPM1-mut AML patients included 54% females. The median age at diagnosis was 53 years, and 73% were younger than 60 years (Table 1). A normal karyotype was observed in 87% of patients, and 39% had FLT3-ITD mutation at diagnosis. CRc after induction treatment was achieved in 87% of patients, while 4% died before response assessment (early-death). Allo-HSCT was performed in 34% patients (24% in CR1). Median follow-up was 6 years, with a median OS of 8.3 years.

Mutational landscape of NPM1-mut AML training cohort

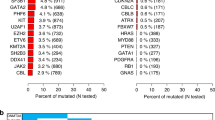

In the training cohort, the most frequently mutated genes were FLT3 in 54% (ITD 39%, TKD 17%), DNMT3A (53%), NRAS (20%), PTPN11 (17%), TET2 (17%), IDH2 (16%), and IDH1 (14%), while other gene mutations were present in less than 10% of patients (Fig. 1). Of note, 59.5% of patients with FLT3-ITD also had DNMT3A-mut, whereas 43.7% of DNMT3A-mut patients also presented with a FLT3-ITD, showing a strong co-occurrence of these two mutations in NPM1-mut AML (odds ratio [OR] 1.5, q = 0.014). Other significant co-occurring gene pairs, exploring all genes mutated in at least 3% of patients, were IDH2 and SRSF2 (OR 7.3, q < 0.001) as well as IDH1 and NRAS (OR 1.8, q = 0.041). FLT3-ITD correlated negatively with NRAS (OR 0.2, q < 0.001), KRAS (OR 0.32, q = 0.008), PTPN11 (OR 0.36, q < 0.001), and SRSF2 (OR 0.1, q < 0.001). DNMT3A showed a negative correlation with STAG2 (OR 0.05, q < 0.001) and SRSF2 (OR 0.22, q < 0.001), while IDH correlated negatively with TET2 (IDH1 OR 0.19, q < 0.001; IDH2 OR 0.16, q < 0.001) and WT1 (IDH1 OR 0.2, q = 0.049; IDH2 OR 0.18, q = 0.028). Based on the relative variant allele frequencies, mutations in DNMT3A, STAG2, TET2, IDH1/2 and SRSF2 appeared to represent early clonal events and generally arose prior to NPM1-mut, while mutations in genes associated with RAS signaling pathway were inferred to be acquired at later stages (Fig. S3).

Development of the HARMONY risk classification for NPM1-mut AML

In order to summarize clinically significant gene co-mutational patterns, a risk classification was developed using the NPM1-mut AML training cohort. Two-year OS of NPM1-wt intensively-treated patients in the same dataset was used as a reference and was 29.9% (95% CI 26.5–33.3%), 47.8% (42.4–53.3%), and 79% (74.3–83.7%) for European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 adverse, intermediate, and favorable risk, respectively (Table S3). In the first step (all 1,001 NPM1-mut patients), co-mutation of FLT3-ITD and DNMT3A-mut was selected, as patients with both mutations had an estimated 2-year OS of 29.1% (21.6-36.6%), similar to ELN2022 adverse (Figs. S4–S7). Among patients with FLT3-ITD and DNMT3A-wt, those with IDH-mut had a predicted 2-year OS of 72.7% (56.4–89%), similar to the ELN2022 favorable-risk group, while IDH-wt patients showed an estimated 2-year OS of 47.4% (36.1–58.8%), comparable to the ELN2022 intermediate-risk group (Figs. S8 and S9). In accordance, 60% of patients with FLT3-ITD in NPM1-mut AML were classified as adverse, 27% as intermediate, and 13% as favorable risk (median OS 0.9 years, 1.5 years, and not reached, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. S10). In the next step, patients with the absence of FLT3-ITD were analyzed, and the combination of DNMT3A and IDH mutations was selected. Patients with DNMT3A-mut and IDH-mut had an estimated 2-year OS of 55.1% (43.6-66.5%), comparable to ELN2022 intermediate, while patients with DNMT3A-mut and IDH-wt presented a predicted 2-year OS of 77.2% (70.6-83.8%), similar to ELN2022 favorable (Figs. S11–S14). As a result, 44% of patients with DNMT3A-mut in NPM1-mut AML were classified as adverse, 17% as intermediate, and 39% as favorable risk (median OS 0.9, 2.3, and 9.5 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. S15). In the last step (absence of FLT3-ITD and DNMT3A-wt), patients with TET2-mut presented an estimated 2-year OS of 56.9% (41-72.8%), in line with ELN2022 intermediate, while patients with TET2-wt had a predicted 2-year OS of 73.5% (67.7-79.3%), closer to ELN2022 favorable (Figs. S16 and S17). Of note, the OS curve of TET2-mut patients did not present a plateau at the 2-year mark, which resulted in significant differences in OS when compared to TET2-wt patients (p = 0.022, Fig. S18). In the subgroup of patients with FLT3-ITD absence, DNMT3-wt and TET2-wt, further risk reclassification could not be made according to the classification requisites, resulting in those patients being categorized as NPM1-mut favorable (Figs. 2A, S19).

A Classification of patients according to the presence or absence of mutations in FLT3 (ITD), DNMT3A, IDH and TET2. B Overall survival according to HARMONY NPM1-mut risk categories. C Relapse-free survival according to HARMONY NPM1-mut risk categories. D Sankey plot of patient reclassification from ELN2022 to HARMONY NPM1-mut categories. E Overall survival of ELN2022 favorable patients, stratified by HARMONY NPM1-mut classification. F Overall survival of ELN2022 intermediate patients, stratified by HARMONY NPM1-mut classification.

The HARMONY NPM1-mut risk classification stratified 51.8% of NPM1-mut AML patients as favorable, 24.8% as intermediate and 23.4% as adverse risk (median OS 14.4, 2.2 and 0.9 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). CRc rates after induction treatment were 90.7%, 83.5% and 83.7% for favorable, intermediate and adverse risk, respectively (p < 0.001). Median RFS was not reached for favorable risk, while it was 1.2 years for intermediate (95% CI 0.92–1.49) and 0.6 years for adverse (95% CI 0.46–0.74) (Fig. 2C). Of note, gender distribution, median patient age, AML type, hemoglobin and platelet values were similar among these three NPM1-mut risk categories (Table 2). FLT3-ITD was present in 10%, 43% and 100% of favorable, intermediate, and adverse risk patients, respectively, which could explain differences in WBC at diagnosis, bone marrow blasts and allo-HSCT rates in CR1 among the subgroups.

Comparison to ELN 2022 risk classification

OS of NPM1-mut AML patients according to HARMONY categories was similar to reference ELN2022 subgroups in NPM1-wt in the training cohort: median OS 11.2 vs 14.4 years for favorable (p = 0.396), 1.7 vs 2.2 for intermediate (p = 0.386) and 1.1 vs 0.9 for adverse risk categories (p = 0.117) (Fig. S20). The HARMONY classification was able to reassign 42.7% of NPM1-mut patients into a different risk category: 234 shifted from intermediate to adverse, 141 from favorable to intermediate and 52 from intermediate to favorable (Fig. 2D, Table S4). Within the ELN2022 favorable subgroup, HARMONY NPM1-mut favorable patients had significant better outcomes than NPM1-mut intermediate cohort (median OS 14.4 vs 2.4 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2E). Within the ELN2022 intermediate group, the HARMONY classification was able to discriminate three different subgroups with distinct outcomes: NPM1-mut favorable, intermediate an adverse (median OS not reached, 1.5 and 0.9 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2F). The predictive performance of 5-year OS of HARMONY classification, measured by the time-dependent receiver operating curve (AUC(t)) was higher than that of ELN2022 (0.695 vs 0.635 respectively, Table S5).

The HARMONY classification was also able to stratify older patients (i.e.,>60 years at diagnosis) into three subgroups with distinct outcomes, with a median OS of 3.5, 1.1, and 0.6 years for favorable, intermediate, and adverse subgroups, respectively (p < 0.001) (Fig. S21).

Multivariable analysis

A multivariable Cox regression model of OS, censoring at transplant date those patients who underwent allo-HSCT in CR1, identified the following pretreatment independent variables: age >60 years (hazard ratio [HR] 2.32, p < 0.001), hyperleukocytosis (>100 ×109/L) at diagnosis (HR 1.77, p < 0.001), prior hematological malignancy (HR 2.51, p = 0.01) and HARMONY NPM1-mut classification (using favorable category as reference, intermediate HR 1.86 [p < 0.001] and adverse HR 2.98 [p < 0.001]). Remarkably, ELN2022 risk categories were not significant in this model (p = 0.602) (Fig. 3).

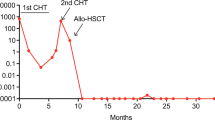

Finally, a multivariable Cox regression model of OS, considering allo-HSCT in CR1 as a time-dependent covariate, in patients aged ≤70 years (i.e., potential transplant candidates) was performed. In the training cohort, allo-HSCT in CR1 improved OS in all HARMONY NPM1-mut subgroups, although the highest benefit was seen in NPM1-mut adverse patients (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.57–0.77, p < 0.001) (Table S6).

Other less frequent genomic abnormalities

The prognostic significance of additional gene mutations — those not included in the HARMONY NPM1-mut risk classification due to their low prevalence in the training cohort — was also investigated. TP53-mut (n = 7) was associated to poor outcomes, with a median OS of 1.2 years (compared to 6.2 for TP53-wt patients, p = 0.002) (Fig. S22). Similarly, RUNX1-mut was associated with shorter OS, especially in patients lacking FLT3-ITD (Fig. S23), while SRSF2-mut patients resembled intermediate prognosis, with a median OS of 2.4 years in that subset (Fig. S24). In contrast, STAG2 or RAD21 mutations were linked to improved OS (median OS not reached, Fig. S25). Notably, the presence of adverse-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (n = 9) did not correlate with distinct OS (Fig. S26).

Internal validation of HARMONY NPM1-mut classification

The internal validation cohort of 762 adult NPM1-mut AML patients had significant differences compared to the training cohort, as patients were older (median 57 vs 53 years, p < 0.001; age ≥60 years 42% vs 27%, p < 0.001), with an increased proportion of patients with history of prior hematological malignancies (7.6% vs 1.5%), higher FLT3-ITD prevalence (45.8% vs 39.3%, p = 0.007) and increased WBC at diagnosis (37 vs 24 × 109/L, p < 0.001) (Table 1). CRc rates after induction treatment were lower (79.5% vs 87.3%, p < 0.001), early-death rates were higher (30-day mortality 8% vs 3.8%, p < 0.001), and fewer patients received allo-HSCT in CR1 (17% vs 24%, p = 0.01). Median follow-up was 7.2 years, with a median OS of 2.8 years (vs 8.3 years in the training cohort, p < 0.001).

The HARMONY NPM1-mut classification stratified 44.8% of the internal validation cohort as favorable, 29.4% as intermediate and 25.8% as adverse risk, with significant differences in OS (median OS 8.2, 2.8 and 0.8 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A) and RFS (median RFS 4.8, 2.1 and 0.5 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). In patients aged >60 years at diagnosis, median OS was 3, 1.6 and 0.6 years, respectively (p < 0.001) (Fig. S21).

In the internal validation cohort, allo-HSCT in CR1 did not enhance OS of HARMONY NPM1-mut favorable patients (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.94–1, p = 0.605), but it showed improved outcomes for the NPM1-mut intermediate subgroup (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.75–0.94, p = 0.003) and again the highest benefit for NPM1-mut adverse patients (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.69–0.88, p < 0.001) in the multivariable Cox regression model of OS, considering allo-HSCT in CR1 as a time-dependent covariate, in patients aged ≤70 years (Table S7).

External validation of HARMONY NPM1-mut classification

The external validation cohort of 585 adult NPM1-mut AML patients also presented significant differences compared to the training cohort (Table S8). In the external validation cohort, patients were also older (median 56 vs 53 years, p < 0.001; age ≥60 years 38% vs 27%, p < 0.001), with an increased proportion of patients with history of prior hematological malignancies (4.8% vs 1.5%, p < 0.001), higher WBC at diagnosis (33 vs 24 ×109/L, p < 0.001), but similar FLT3-ITD prevalence (41.5% vs 39.3%, p = 0.401). Composite complete remission rates after induction treatment were similar (89.6% vs 87.3%), although early death rate was higher (30-day mortality 6% vs 3.8%, p = 0.045). Allo-HSCT rates were higher (41.7% vs 34.1% at any time, p = 0.003), although information regarding the transplant timing was not provided for most of the patients. Therefore, OS and RFS were analyzed without censoring at transplant date in the external validation cohort. Median follow-up was 6.4 years, with a median OS of 4.5 years (vs 8.25 years in the training cohort, p < 0.001). In summary, the external validation cohort exhibited features that, in general, fell between those of the training cohort and the internal validation cohort (Table S9).

The HARMONY NPM1-mut classification stratified 47.7% of the external validation cohort as favorable, 28.5% as intermediate and 23.8% as adverse risk, with significant differences in OS (median OS not reached, 3.8 and 1.2 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4C) and RFS (median RFS 3.5, 1.3 and 0.8 years, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4D). AUC(t) of 5-year OS was 0.6 for HARMONY NPM1-mut classification and 0.558 for ELN2022 (Table S5). In patients aged >60 years at diagnosis, median OS was 3.6, 1.7, and 0.7 years, respectively (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S21).

Discussion

NPM1-mut AML comprises the largest adult AML subtype in younger adults, making accurate risk stratification of paramount importance to inform clinical decisions [11]. Since the initial discovery of this entity, FLT3-ITD has been the only co-mutation consistently associated with inferior OS and remains the only significant co-mutation affecting prognosis in this AML subtype in current guidelines [2, 5, 6, 33,34,35]. In this study, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the largest NPM1-mut AML cohort studied by panel sequencing to date, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the mutational landscape, identifying additional co-mutations with prognostic implications. DNMT3A and FLT3-ITD are the most frequent co-mutations, but they tend to appear together, making it difficult to address the prognostic value of each mutation individually in smaller cohorts. In our study, FLT3-ITD with DNMT3A-wt was present in only 16% of patients, DNMT3A-mut in the absence of FLT3-ITD was found in 30%, while both mutations were present in 23% of the patients, which is in line with recent reports [7]. This “triple-mutated” AML subgroup (NPM1-mut, FLT3-ITD, DNMT3A-mut) was associated with dismal outcomes, with a median RFS of less than 9 months in all datasets included in our study.

The interaction between these three mutations has been reported previously, consistently associated with inferior OS [1, 7, 13, 14, 36]. Moreover, recent studies have found that this triple-mutated AML shows distinct characteristics, such as aberrant leukemia-specific GPR56high and CD34low immunophenotype, high leukemia stem cell frequency, and upregulation of hepatic leukemia factor [15]. While it remains unclear if the NPM1-mut, FLT3-ITD, DNMT3A-mut subgroup will be recognized as a distinct biologic entity in the future, it seems reasonable to consider this subgroup as an adverse risk, at least with conventional chemotherapy approaches.

In addition to this important confirmatory aspect of our study, we also identified a subset of FLT3-ITD positive NPM1-mut patients with favorable outcomes (i.e. NPM1-mut, FLT3-ITD, DNMT3A-wt, and IDH-mut) that has not been reported in previous studies. Remarkably, IDH-mut were associated with a favorable outcome in patients with FLT3-ITD and DNMT3A-wt, while a deleterious effect was shown in the subgroup of patients with DNMT3A-mut and absence of FLT3-ITD, which is consistent with the results reported by Paschka et al. in the latter subgroup [37]. Moreover, this paradoxical prognostic effect has been documented for other gene mutations in adult AML, such as DNMT3A and PTPN11, highlighting the importance of careful evaluation of co-mutational patterns for accurate patient risk stratification [9, 38]. While the biological mechanisms underlying the impact of IDH-mut on treatment outcome in NPM1-mut AML remain to be fully elucidated, it could be related to the epigenetic state in which the transforming events occur, such as NPM1-mut and FLT3-ITD, as these events are generally acquired at a later stage [7, 39]. In contrast, the acquisition of DNMT3A-mut and IDH-mut is are early event, both linked to clonal hematopoiesis [40], and deregulated epigenetic states that are distinct between DNMT3A-mut and IDH-mut [41].

The incorporation of myelodysplasia (MDS)-related gene mutations (i.e., ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, ZRSR2) in the ELN2022 guidelines as adverse risk has raised the question of whether their presence could influence outcome in NPM1-mut AML, with contradictory results to date [42, 43]. We found that only three of these mutations (SRSF2, STAG2, RUNX1) were present in more than 1% of our cohort, which precluded the consideration of most MDS-related gene mutations into the classification. Notably, in our cohort, the presence of a RUNX1-mut was associated with adverse outcome, SRSF2-mut with intermediate prognosis, while STAG2-mut identified a subgroup of patients with favorable outcomes in the absence of FLT3-ITD. These findings suggest that MDS-related gene mutations, which are also early genetic events like clonal hematopoiesis-associated gene mutations, provide a different basis for transforming events, which, in the case of NPM1-mut can impact patient outcome in distinct ways. Moreover, the presence of adverse-risk cytogenetic abnormalities was not associated with inferior outcomes in our training cohort, while TP53-mut patients showed a significantly shorter OS. Both events are uncommon in NPM1-mut AML, so further studies will be required to confirm these clinically relevant findings.

In NPM1-mut AML, a median of up to 13 gene mutations per patient when whole exome analysis is performed has been reported, so hundreds of co-mutational combinations can form in this AML subtype [44]. In our study, we aimed to reduce this complexity in the final classification by taking only five of the most prevalent gene mutations into account: FLT3-ITD, DNMT3A-mut, IDH1/IDH2-mut, and TET2-mut. The HARMONY classification was able to stratify NPM1-mut patients into favorable, intermediate, and adverse risk categories, with comparable outcomes to their NPM1-wt counterparts according to ELN2022 in the same dataset. Remarkably, this risk stratification was able to reclassify more than 40% of NPM1-mut patients into a different risk category when compared to ELN2022 guidelines, underscoring the importance of understanding respective co-mutational patterns that can affect AML subtype-specific outcomes [6].

Importantly, the distribution of NPM1-mut risk categories was similar in all cohorts analyzed, both the training as well as the internal and external validation cohorts, accounting for 45-52% favorable, 25-29% intermediate, and 23-26% adverse risk patients contained within the NPM1-mut AML subtype. Prediction of outcomes in intensively-treated older patients (i.e.,>60 years) is challenging with current stratification systems, so novel approaches are warranted [45, 46]. The HARMONY classification was also applicable to older patients and, similarly to the entire cohort, identified three different outcome subgroups in the training as well as internal validation and external validation cohorts.

However, there are also several limitations to our study that should be taken into account. First, it is a retrospective, multicenter analysis, where patients were treated in various European countries with different intensive chemotherapy regimens. Accordingly, the HARMONY NPM1-mut classification was first developed in a cohort of patients included in clinical trials from large cooperative groups (AMLSG and HOVON-SAKK), thereby harboring a potential selection bias. However, findings could be validated in an independent validation cohort comprising real-world data derived from European institutions. Although this cohort did not include patients treated with intensive combination therapies including targeted therapeutic such as FLT3–ITD inhibitors or GO, which have demonstrated to improve outcomes in NPM1-mut AML [47,48,49,50], an additional validation of the HARMONY classification was carried out with a cohort of patients enrolled in UK-NCRI trials, where patients received GO or FLT3 inhibitor lestaurtinib in addition to intensive chemotherapy. In accordance, further studies will be required to re-evaluate the prognostic and predictive impact of the HARMONY NPM1-mut classification to stratify patients treated with midostaurin or non-intensive approaches. Our analyses did not include assessment of measurable residual disease (MRD). While MRD in peripheral blood after two treatment cycles has proven to be a strong prognostic factor in NPM1-mut AML, novel treatment strategies have reduced the MRD positivity rate to less than 20% of patients, limiting the proportion of patients identified as high-risk [51, 52]. Moreover, a 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse of up to 40% has been reported even in MRD-negative patients [7], suggesting that a combination of genotype at diagnosis and MRD assessment after treatment would provide the most accurate estimation of patient outcomes.

In summary, this study provides novel insights regarding co-mutational patterns with prognostic implications in intensively-treated NPM1-mut AML adult patients. The HARMONY classification suggests that more than 40% of NPM1-mut patients might be re-classified into a different ELN2022 risk category, taking additional markers into account. Further evaluation is warranted prior to clinical application, especially in the light of age-dependent differences in co-mutational patterns [53] and novel combinatorial treatments for this AML subtype.

Data availability

After the publication of this article, data collected for this analysis and related documents will be made available to others upon reasonably justified request, which needs to be written and addressed to the attention of the corresponding author, Dr Lars Bullinger at the following e-mail address: lars.bullinger@charite.de. The HARMONY Alliance, via the corresponding author Dr Lars Bullinger, is responsible to evaluate and eventually accept or refuse every request to disclose data and their related documents, in compliance with the ethical approval conditions, in compliance with applicable laws and regulations, and in conformance with the agreements in place with the involved subjects, the participating institutions, and all the other parties directly or indirectly involved in the participation, conduct, development, management, and evaluation of this analysis.

References

Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–21.

Falini B, Nicoletti I, Martelli MF, Mecucci C. Acute myeloid leukemia carrying cytoplasmic/mutated nucleophosmin (NPMc+ AML): Biologic and clinical features. Blood. 2007;109:874–85.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, Borowitz MJ, Calvo KR, Kvasnicka HM, et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022;140:1200–28.

Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1703–19.

Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, Alcalay M, Rosati R, Pasqualucci L, et al. Cytoplasmic Nucleophosmin in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia with a Normal Karyotype. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:254–66.

Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, Craddock C, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022;140:1345–77.

Othman J, Potter N, Ivey A, Tazi Y, Papaemmanuil E, Jovanovic J, et al. Molecular, clinical, and therapeutic determinants of outcome in NPM1-mutated AML. Blood. 2024;144:714–28.

Guryanova OA, Shank K, Spitzer B, Luciani L, Koche RP, Garrett-Bakelman FE, et al. DNMT3A mutations promote anthracycline resistance in acute myeloid leukemia via impaired nucleosome remodeling. Nat Med. 2016;22:1488–95.

Gale RE, Lamb K, Allen C, El-Sharkawi D, Stowe C, Jenkinson S, et al. Simpson’s paradox and the impact of different DNMT3A mutations on outcome in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2072–83.

Ivey A, Hills RK, Simpson MA, Jovanovic JV, Gilkes A, Grech A, et al. Assessment of minimal residual disease in standard-risk AML. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:422–33.

Bullinger L, Döhner K, Dohner H. Genomics of acute myeloid leukemia diagnosis and pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:934–46.

Oñate G, Bataller A, Garrido A, Hoyos M, Arnan M, Vives S, et al. Prognostic impact of DNMT3A mutation in acute myeloid leukemia with mutated NPM1. Blood Adv. 2022;6:882–90.

Ley T, Miller C, Ding L, Raphael B, Mungall A, Robertson A, et al. Genomic and Epigenomic Landscapes of Adult De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2059–74.

Bezerra MF, Lima AS, Piqué-Borràs MR, Silveira DR, Coelho-Silva JL, Pereira-Martins DA, et al. Co-occurrence of DNMT3A, NPM1, FLT3 mutations identifies a subset of acute myeloid leukemia with adverse prognosis. Blood. 2020;135:870–5.

Garg S, Reyes-Palomares A, He L, Bergeron A, Lavallée VP, Lemieux S, et al. Hepatic leukemia factor is a novel leukemic stem cell regulator in DNMT3A, NPM1, and FLT3-ITD triple-mutated AML. Blood. 2019;134:263–76.

Falini B, Brunetti L, Sportoletti P, Paola Martelli M. NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: From bench to bedside. Blood. 2020;136:1707–21.

Balsat M, Renneville A, Thomas X, De Botton S, Caillot D, Marceau A, et al. Postinduction minimal residual disease predicts outcome and benefit from allogeneic stem cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation: A study by the acute leukemia French association group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:185–93.

Angenendt L, Röllig C, Montesinos P, Martínez-Cuadrón D, Barragan E, García R, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities and prognosis in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: A pooled analysis of individual patient data from nine international cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2632–42.

Haferlach C, Mecucci C, Schnittger S, Kohlmann A, Mancini M, Cuneo A, et al. AML with mutated NPM1 carrying a normal or aberrant karyotype show overlapping biologic, pathologic, immunophenotypic, and prognostic features. Blood. 2009;114:3024–32.

Moukalled N, Labopin M, Versluis J, Socié G, Blaise D, Salmenniemi U, et al. Complex karyotype but not other cytogenetic abnormalities is associated with worse posttransplant survival of patients with nucleophosmin 1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: A study from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Acute Leukem. Am J Hematol. 2024;99:360–9.

Othman J, Meggendorfer M, Tiacci E, Thiede C, Schlenk R, Dillon R, et al. Overlapping features of therapy-related and de novo NPM1-mutated AML. Blood. 2023;141:8–10.

Angenendt L, Röllig C, Montesinos P, Ravandi F, Juliusson G, Récher C, et al. Revisiting coexisting chromosomal abnormalities in NPM1-mutated AML in light of the revised ELN 2022 classification. Blood. 2023;141:433–5.

Mason EF, Hasserjian RP, Aggarwal N, Seegmiller AC, Pozdnyakova O. Blast phenotype and comutations in acute myeloid leukemia with mutated NPM1 influence disease biology and outcome. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3322–32.

Wang B, Yang B, Wu W, Liu X, Li H. The correlation of next-generation sequencing-based genotypic profiles with clinicopathologic characteristics in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1–11.

Löwenberg B, Pabst T, Maertens J, Van Norden Y, Biemond BJ, Schouten HC, et al. Therapeutic value of clofarabine in younger and middle-aged (18-65 years) adults with newly diagnosed AML. Blood. 2017;129:1636–45.

Ossenkoppele GJ, Breems DA, Stuessi G, van Norden Y, Bargetzi M, Biemond BJ, et al. Lenalidomide added to standard intensive treatment for older patients with AML and high-risk MDS. Leukemia. 2020;34:1751–9.

Löwenberg B, Pabst T, Maertens J, Gradowska P, Biemond BJ, Spertini O, et al. Addition of lenalidomide to intensive treatment in younger and middle-aged adults with newly diagnosed AML: The HOVON-SAKK-132 trial. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1110–21.

Metzeler KH, Herold T, Rothenberg-Thurley M, Amler S, Sauerland MC, Görlich D, et al. Spectrum and prognostic relevance of driver gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016;128:686–98.

Belenkaya R, Gurley MJ, Golozar A, Dymshyts D, Miller RT, Williams AE, et al. Extending the OMOP Common Data Model and Standardized Vocabularies to Support Observational Cancer Research. JCO Clin Cancer Inf. 2021;5:12–20.

Middeke JM, Metzeler KH, Rollig C, Kramer M, Eckardt JN, Stasik S, et al. Differential impact of IDH1/2 mutational subclasses on outcome in adult AML: results from a large multicenter study. Blood Adv. 2022;6:1394–405.

Tazi Y, Arango-Ossa JE, Zhou Y, Bernard E, Thomas I, Gilkes A, et al. Unified classification and risk-stratification in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4622.

Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 2002;64:479–98.

Schnittger S, Schoch C, Kern W, Mecucci C, Tschulik C, Martelli MF, et al. Nucleophosmin gene mutations are predictors of favorable prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. Blood. 2005;106:3733–9.

Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, Burnett AK, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: Recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115:453–74.

Döhner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, Scholl C, Rücker FG, Corbacioglu A, et al. Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: Interaction with other gene mutations. Blood. 2005;106:3740–6.

Straube J, Ling VY, Hill GR, Lane SW. The impact of age, NPM1mut, and FLT3ITD allelic ratio in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2018;131:1148–53.

Paschka P, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, Habdank M, Krönke J, Bullinger L, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia and confer adverse prognosis in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation without FLT3 internal tandem duplication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3636–43.

Alfayez M, Issa GC, Patel KP, Wang F, Wang X, Short NJ, et al. The Clinical impact of PTPN11 mutations in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2021;35:691–700.

Cocciardi S, Dolnik A, Kapp-Schwoerer S, Rücker FG, Lux S, Blätte TJ, et al. Clonal evolution patterns in acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–11.

Chan SM, Majeti R. Role of DNMT3A, TET2, and IDH1/2 mutations in pre-leukemic stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2013;98:648–57.

Glass JL, Hassane D, Wouters BJ, Kunimoto H, Avellino R, Garrett-Bakelman FE, et al. Epigenetic identity in AML depends on disruption of nonpromoter regulatory elements and is affected by antagonistic effects of mutations in epigenetic modifiers. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:868–83.

Eckardt JN, Bill M, Rausch C, Metzeler K, Spiekermann K, Stasik S, et al. Secondary-type mutations do not impact outcome in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia – implications for the European LeukemiaNet risk classification. Leukemia. 2023;37:2282–5.

Chan O, Al Ali N, Tashkandi H, Ellis A, Ball S, Grenet J, et al. Mutations highly specific for secondary AML are associated with poor outcomes in ELN favorable risk NPM1-mutated AML. Blood Adv. 2024;8:1075–83.

Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, Wilmot B, Kurtz SE, Savage SL, et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2018;562:526–31.

Park S, Kim TY, Cho BS, Kwag D, Lee JM, Kim M, et al. Prognostic value of European LeukemiaNet 2022 criteria and genomic clusters using machine learning in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2024;109:1095–106.

Versluis J, Metzner M, Wang A, Gradowska P, Thomas A, Jakobsen NA, et al. Risk Stratification in Older Intensively Treated Patients With AML. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:4084–94.

Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, Laumann K, Geyer S, Bloomfield CD, et al. Midostaurin plus Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia with a FLT3 Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:454–64.

Oñate G, Pratcorona M, Garrido A, Artigas-Baleri A, Bataller A, Tormo M, et al. Survival improvement of patients with FLT3 mutated acute myeloid leukemia: results from a prospective 9 years cohort. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:69.

Schlenk RF, Paschka P, Krzykalla J, Weber D, Kapp-Schwoerer S, Gaidzik VI, et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: Early results from the prospective randomized AMLSG 09-09 Phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:623–32.

Kapp-Schwoerer S, Weber D, Corbacioglu A, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Krönke J, et al. Impact of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on MRD and relapse risk in patients with NPM1-mutated AML: Results from the AMLSG 09-09 trial. Blood. 2020;136:3041–50.

Othman J, Potter N, Ivey A, Jovanovic J, Runglall M, Freeman SD, et al. Postinduction molecular MRD identifies patients with NPM1 AML who benefit from allogeneic transplant in first remission. Blood. 2024;143:1931–6.

Russell NH, Wilhelm-Benartzi C, Othman J, Dillon R, Knapper S, Batten LM, et al. Fludarabine, Cytarabine, Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor, and Idarubicin With Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Improves Event-Free Survival in Younger Patients With Newly Diagnosed AML and Overall Survival in Patients With NPM1 and FLT3 Mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1158–68.

Cocciardi S, Saadati M, Weiß N, Späth D, Kapp-Schwoerer S, Schneider I, et al. Impact of myelodysplasia-related and additional gene mutations in intensively treated patients with NPM1-mutated AML. Hemasphere. 2025;9:e70060.

Acknowledgements

This publication has emanated from research conducted with the support of the HARMONY Alliance Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the HARMONY Alliance Foundation. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author-accepted manuscript version arising from this submission. HARMONY and HARMONY PLUS were funded through the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), Europe’s largest public-private initiative aiming to speed up the development of better and safer medicines for patients. Funding was received from the IMI 2 Joint Undertaking and is listed under grant agreement for HARMONY No. 116026 and grant agreement for HARMONY PLUS No. 945406. This Joint Undertaking received support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA). This study presents results from the AML workgroup in HARMONY. AHS was supported by Contrato Río Hortega CM23/00101 (ISCIII). ATT received additional support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grant FU 356/12-1 (ATT). RM was supported by the Mildred-Scheel-Postdoctoral-Program from Deutsche Krebshilfe (Grant no.: 70115737). This work was partially presented as an oral presentation at the ASH 2022 meeting in New Orleans: Hernández Sánchez A, Villaverde Ramiro A, Sträng E, et al. Machine Learning Allows the Identification of New Co-Mutational Patterns with Prognostic Implications in NPM1 Mutated AML - Results of the European Harmony Alliance. Blood. 2022;140 (Supplement 1):739–742.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AHS, JMHR, BH, GO, HD, and LB designed the study. AHS, AVR, ES, ATT, MA, JV, IT, MS, JML, MP, KM, SL, CR, CT, KHM, KD, MH, TH, PJMV, NR, HD, and JMHR performed data collection and assembly of the data. AHS, AVR, ES, GC, AB, RA, JMT, RM, GS, MTV, KD, JMHR, BH, GO, HD, and LB performed data analysis and interpretation. AHS and LB wrote the manuscript. BJPH, GO, and HD critically reviewed the manuscript. LB supervised research and coordinated the HARMONY AML group. All authors had access to the primary data, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ATT: Consultancy for CSL Behring, Maat Pharma, Biomarin, and Onkowissen; travel reimbursements from Neovii Biotech and Novartis. MS: honoraria from Novartis, Celgene, AOP Orphan, and AbbVie. KHM: honoraria from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Otsuka; research funding from AbbVie. RA: honoraria from Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, and Novartis. MP: honoraria from Novartis. GS: honoraria from Takeda and has participated in Ad-Boards from Novartis, Celgene, AbbVie, Helsinn, and Takeda. CR: honoraria from AbbVie, Astellas, Bristol-Meyer-Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Jazz, Janssen, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Servier; institutional research funding from AbbVie, Astellas, Novartis, Pfizer. CT: co-owner and CEO of AgenDix GmbH and has received lecture fees and/or participated in Ad-Boards from Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Janssen, Illumina; research funding from Novartis, Bayer. KD: honoraria from Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie; has participated in Ad-Boards from Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie; research funding from Novartis, Astellas, Agios, Bristol Myers Squibb, Kronos. MH: honoraria from Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen, Miltenyi, Otsuka, Qiagen, Servier, and has participated in Ad-Boards from AbbVie, AvenCell, Ascentage Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, LabDelbert, Novartis, Pfizer, Servier; research funding from AbbVie, Bayer Pharma AG, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Glycostem, Karyopharm, PinotBio, Servier, Toray. TH: current employment at Munich Leukemia Laboratory, with part ownership. JMHR: honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Amgen, Celgene, GSK, Novartis; Advisory role for Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Amgen, Celgene, Novartis, Janssen, Roche, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Lilly, Gilead, Takeda, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Rovi, Incyte; research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Novartis. BH: honoraria from Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis; research funding from AstraZeneca. GO: honoraria from AbbVie, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Gilead, Bristol Myers Squibb, Servier, Roche. HD: Advisory role for AbbVie, Agios, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, BERLIN-CHEMIE, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, GEMoaB, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Syndax; research funding from AbbVie, Agios, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Kronos-Bio, Novartis. LB: honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Hexal, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Menarini, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi; research funding from Bayer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hernández-Sánchez, A., Villaverde Ramiro, Á., Sträng, E. et al. Unravelling co-mutational patterns with prognostic implications in NPM1 mutated adult acute myeloid leukemia – a HARMONY study. Leukemia (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02851-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02851-9