Abstract

Treatment-free remission (TFR) after discontinuation of ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) is an important therapeutic goal in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Interferon-α (IFN) has been suggested to promote durable TFR. The phase 3 ENDURE trial (NCT03117816; EUDRA-CT 2016-001030-94) prospectively tested this hypothesis in patients with stable deep molecular remission after TKI therapy. A total of 203 patients were randomised 1:1 to receive ropeginterferon alfa-2b (ropeg-IFN; 100 µg subcutaneously every two weeks for 15 months, n = 95) or observation alone (n = 108) after TKI discontinuation. The primary endpoint was molecular relapse-free survival (MRFS), defined as time to loss of major molecular response (MMR) or death. At a median follow-up of 36 months, 25-month MRFS was 56% (95% confidence interval (CI), 45–66) with ropeg-IFN and 59% (95% CI, 49–68) with observation (hazard ratio (HR), 1.02; 95% CI, 0.68–1.55; P = 0.91). Among 83 patients with molecular data after TKI restart, 79 (95%) regained at least MMR, 78 within 12 months (median 3 months, interquartile range: 2-4 months). Ropeg-IFN was well tolerated (median administered dose of 92 µg, range 3–104), and no new safety signals were observed. Ropeg-IFN maintenance did not improve the probability of sustained TFR after TKI discontinuation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy with imatinib has normalized survival expectations for patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [1, 2]. However, TKIs frequently fail to eradicate CML stem cells, necessitating lifelong treatment for the majority of patients [3, 4]. This includes the need for switching of TKI in case of toxicity or the development of TKI resistance [5].

TKI-induced remissions in CML are due to the inhibition of the causative oncogenic kinase, BCR::ABL1. In contrast, the anti-leukemic effects of interferon-alpha (IFN) in CML [6] are pleiotropic. IFN activates the JAK-STAT-signaling pathway in immune cells [7,8,9] and regulates elicitation of anti-leukemic immune responses [10,11,12,13]. Combination strategies involving TKI and IFN have therefore been proposed to harness the complementary anti-leukemic effects of both agents. These approaches have been shown to accelerate the achievement of deep molecular remission [14,15,16,17], which is a key prerequisite for TFR eligibility [5, 18]. Moreover, we have previously postulated that higher rates of treatment-free remission (TFR) might be achievable through maintenance with pegylated IFN after TKI discontinuation [12, 19, 20]. However, this hypothesis had not been tested or confirmed in a controlled clinical trial prior to ENDURE.

While TKI discontinuation in eligible patients has consistently resulted in long-term TFR rates of around 50% [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], the underlying biological mechanisms of TFR remain largely unclear. They are multifactorial [31], but are presumed to involve immunological control of residual CML [32,33,34,35,36]. As TKI treatment has been linked to a normalization of the immune effector cell composition [37], IFN—known for its pleiotropic immune-stimulatory properties [7]—was hypothesized to more effectively engage the immune system after prior TKI exposure, potentially enhancing the likelihood of sustained TFR. This premise was tested in the randomized, phase 3 ENDURE trial (NCT03117816). In this interventional TFR study, patients with CML in deep molecular remission suitable to discontinue TKI therapy were randomly assigned to receive pegylated interferon alfa-2b (ropeg-IFN) for 15 months or undergo surveillance [38, 39].

Subjects and methods

Patients

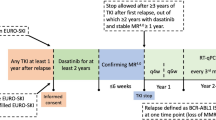

For this open-label, randomized trial, we enrolled adults with CML in France (3 centers) and Germany (24 centers). Eligible patients had BCR::ABL1-positive chronic phase CML and were receiving treatment with any TKI. Patients were required to have a minimum TKI treatment duration at the time of randomization of three years, and a minimum duration of deep molecular remission (DMR) of one year. DMR was defined as detectable BCR::ABL1 ( ≤ 0.01% on the International Scale [40]) or undetectable BCR::ABL1 in samples with 10 000 or more ABL1 transcripts or 24 000 or more GUS transcripts. Patients were required to have three PCR results confirming DMR within 12 months prior to study entry, with no results falling below MR4 during that period. An exposure to IFN prior to study entry was not allowed. Patients with a first or second discontinuation attempt could be included. A prior history of TKI resistance was also not an exclusion criterion (see complete inclusion/exclusion criteria available online in the Data Supplement).

Study design and treatment

ENDURE is an international phase 3 trial (registered with ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03117816 and EUDRA-CT: 2016-001030-94). The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Philipps University Marburg and at each participating center. Ropeg-IFN was provided by AOP Health (Vienna, Austria). All patients gave written informed consent at the time of enrollment. In the consent form, patients could opt for additional participation in translational biomarker studies, which required additional blood sampling at randomization and regular intervals thereafter. The full protocol of this trial is available online (Data Supplement). All investigators had access to all data and have confirmed its accuracy as well as complete adherence to the study protocol.

Eligible patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either ropeg-IFN or no further treatment after TKI discontinuation. Randomization was stratified according to the trial site and prior failure of a discontinuation attempt (yes/no). Patients in the experimental arm received 50 μg ropeg-IFN subcutaneously (s.c.) every 2 weeks for the first month and 100 μg ropeg-IFN s.c. every 2 weeks thereafter up to month 15. In case of a loss of MMR, TKI treatment was resumed without delay.

Study endpoints and assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was molecular relapse-free survival (MRFS) and was analysed as a time-to-event variable. MRFS was defined as the time from randomization to molecular relapse, which is defined as a loss of major molecular remission (MMR), which is any increase of the BCR::ABL1 transcript level to >0.1% according to the international scale (IS) or to death from any cause. Accelerated disease and blast crisis implied a prior loss of MMR and were counted as events. A restart of TKI without a prior loss of MMR was censored at the time of restart. Survivors without an event or restart prior to loss of MMR were censored on the last date they were known to be alive. Secondary endpoints can be found in the protocol and included overall survival, safety and tolerability of ropeg-IFN maintenance, quality of life after TKI stop and assessment of immunological biomarkers associated with TFR (Data Supplement). Safety was assessed in 202 of the 203 patients (safety population), excluding one randomized ropeg-IFN patient, who did not receive at least one ropeg-IFN dose.

Data entry lock for the primary analysis was June 2022.

Sample size calculation

Assuming an exponential distribution, hazard rates for the primary endpoint MRFS were 0.0529 for the control arm and 0.0297 for the experimental arm. With an accrual time of 25 months after randomization, a minimum follow-up time of 7 months, a drop-out rate of 5%, and 1:1 randomization, a sample size of 210 patients would provide 80% power to detect a significant difference between the hazard rates at a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

Statistical analysis

MRFS probabilities over time were described using Kaplan-Meier estimates. The MRFS probabilities between the two treatment arms were compared with the log-rank test. As randomization was stratified by prior failure of a discontinuation attempt, the influence of stratum and a potential interaction between treatment arm and stratum were examined using a stratified log-rank test and multiple Cox regression modelling. MRFS was also analysed at the fixed times 6, 12, and 24 months after TKI discontinuation, corresponding to 7, 13, and 25 months after randomization, due to a one-month overlap of treatment with ropeg-IFN and TKI prior to TKI discontinuation.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause or censoring at the last time the patient was known to be alive. OS was estimated using Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Except for the analysis of the primary endpoint and the potential testing of the hierarchically ordered secondary endpoints MRFS at 7, 13, and 25 months after randomization, all statistical analyses were exploratory. Due to reduced sample sizes over time, in case of the three ordered secondary endpoints, one-sided tests were performed, with the null hypotheses that the results in the experimental arm would be worse. Unless specified otherwise, P values were not adjusted for multiple testing. For all tests, the significance level was set at 0.05. Point estimations are given together with their 95%-CI.

The software for analysis was SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 4.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patients

Between May 2017 and June 2021, 223 patients entered screening. Overall, 203 patients (68 females, 135 males) with a median age of 55 years (range 20-88) were randomly assigned to ropeg-IFN maintenance after TKI stop (n = 95) versus surveillance only after TKI stop (n = 108) (Fig. 1). For 77 patients in the ropeg-IFN arm (81%) and 86 patients in the surveillance arm (80%), it was the first TKI discontinuation attempt (Table 1). The median TKI treatment duration prior to TKI stop was 7.8 years (range, 2.5 –19,7) and the proportion of ELTS-high risk patients [41] was comparable in both arms and 15% for the entire cohort (Table 1). Median duration of latest stable MR4 or better was 3 years (inter quartile range (IQR): 2–5 years). At the time of data cut off in June 2022, the median observation time for all patients was 36 months (IQR: 25–48).

Of 223 patients screened, 9 (4.0%) did not meet the eligibility criteria. A total of 214 patients (96%) were randomized to either ropeginterferon alfa-2b (AOP2014; n = 101) or surveillance (n = 113). After randomization, 11 patients (4.9%) were excluded from the analysis. The final analysis population comprised 95 patients in the ropeg-IFN arm and 108 patients in the surveillance arm. COVID coronavirus disease, MMR major molecular remission, PegIFN pegylated interferon.

Efficacy

The Kaplan-Meier probabilities MRFS by 6, 12, and 24 months after TKI discontinuation were 73% (95%-CI, 62–81%), 64% (53–73%) and 56% (45–66%) for the ropeg-IFN versus 67% (57–75%), 60% (50–69%) and 59% (49–68%) for no treatment (Fig. 2). The hazard ratio (HR) of molecular relapse for the no treatment cohort versus the ropeg-IFN cohort was 1.024 (95% CI, 0.679–1.546; log-rank P = 0.91). The result of the log-rank test stratified for a prior TKI stopping attempt was P = 0.96.

MRFS probabilities are shown for patients with CML who discontinued TKI therapy after one month and were randomized to receive either ropeginterferon alfa-2b (ropeg-IFN) maintenance for 15 months or surveillance. At months 7, 13, and 25 after randomization (corresponding to 6, 12, and 24 months after TKI discontinuation), MRFS probabilities were 73%, 64%, and 56% in the ropeg-IFN arm and 67%, 60%, and 59% in the surveillance arm, respectively. Numbers below the graph indicate patients at risk at each time point. CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio.

The probability of MRFS at 6, 12, and 24 months after TKI discontinuation (secondary endpoints) were 70% (95%-CI, 60–79%), 64% (95%-CI, 53–73%) and 49% (95%-CI, 38–60%) in 91, 91, and 78 patients of the ropeg-IFN group versus 65% (95-CI, 56–74%; p = 0.23, one-sided), 59% (95-CI, 50–68%, p = 0.27) and 50% (95-CI, 40–60%; p = 0.93) in 107, 106 and 92 patients of the surveillance group. A post hoc subgroup analysis of patients with a first discontinuation attempt (n = 108) and a treatment duration of more than 6 years favored TFR with ropeg-IFN, but the difference between the two arms were not statistically significant (Fig. S1).

Safety

Ninety patients lost MMR after TKI stop and were candidates for restarting TKI. Molecular data on 83 patients were available after TKI restart. Of those, 79 patients re-achieved at least MMR, 78 within 12 months. The median time to re-achievement of MMR was 3 months (Fig. 3, IQR: 2-4 months). Of the 4 patients who did not regain MMR, one patient withdrew consent and others were observed for only 1, 4, and 11 months after treatment restart. Of the evaluable 83 patients, 72 patients re-achieved a first MR [4] after a median time of 4.4 months (Fig. 3). Of 11 patients who did not, 7 patients had a follow-up after TKI restart of less than 7 months and had no MR [4] within this time. The 4 other patients without MR [4] re-achievement had their last evaluations at 11, 15, 24, and 31 months after restart.

Left panel: Median time to reachievement of MMR was 3.1 months in the ropeg-IFN group vs. 3.2 months in the placebo group. Right panel: Median time to MR [4] was 4.2 months in the ropeg-IFN group vs. 4.8. months in the placebo group. MMR, major molecular remission; MR [4], molecular remission BCR::ABL ≤ 0.01% according to international scale; TKI tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

After a median observation time of 36 months (IQR: 25–48 months), none of the patients progressed and three patients died after 9, 15, and 16 months (Fig. 4). One patient died due to a cardiac arrest while in MMR. The cause of death was unknown for the second patient. A third patient died after falling from stairs. There were no CML-specific deaths in the trial.

There were three deaths in the trial. One patient died due to a cardiac arrest while in MMR. The cause of death was unknown for the second patient. A third patient died after falling from stairs. The latter two patients had regained deep molecular response at the level MR4 after re-commencing TKI therapy for MMR-loss. At 48 months, 53 patients were still under observation. CI confidence interval.

Ropeg-IFN dosing, safety and toxicity

Patients randomized to the ropeg-IFN arm were scheduled for a maximum of 32 biweekly administrations during the fifteen months of maintenance treatment. Ninety four of 95 patients who were randomized to ropeg-IFN received at least one ropeg-IFN dose. Of those, 58 patients had a ropeg-IFN treatment observation time of at least 15 months and maintained MMR (MMR cohort). 41 patients in the MMR cohort (71%) actually received at least 30 biweekly ropeg-IFN injections, albeit at a reduced dose in four patients. The remaining 17 patients in the MMR cohort (29%) received less than at least 30 ropeg-IFN injections due to AE (n = 4) or ropeg-IFN-discontinuation for other reasons (n = 13). Of the other 36 ropeg-IFN patients who were not observed for at least 15 months without loss of MMR, 32 patients discontinued ropeg-IFN due to loss of MMR, 1 patient due to an AE and 3 patients because of other reasons. The median ropeg-IFN dose in the 94 patients receiving at least one ropeg-IFN dose was 92 µg (range, 3–104 µg).

174 of 202 patients (86,1%) of the safety population experienced at least one AE. There were 87 patients with any AE in the ropeg-IFN arm (92,6%) and 87 patients with any AE in the surveillance arm (80,6%). Lower grade AEs were frequent in both arms (Supplemental Table 1). Thirty-two higher grade AEs (WHO° 3 or 4) were observed in the ropeg-IFN arm and 26 higher grade AEs (only WHO° 3) in the surveillance group (Table 2). Of the 29 reported SAEs in 21 patients with moderate to severe intensity, 7 SAEs in six patients were evaluated as possibly related to ropeg-IFN (n = 5) or surveillance (n = 2) (Supplemental Table 2). Together, ropeg-IFN maintenance treatment was well tolerated in CML patients in TFR with no new safety signals for ropeg-IFN.

Discussion

In the randomized ENDURE trial, IFN maintenance conferred no additional benefit in sustaining TFR among CML patients who had achieved a deep molecular remission with TKI monotherapy. While this finding is consistent with results from the large randomized German CML-V (TIGER) trial — which likewise failed to demonstrate a significant TFR benefit from IFN maintenance, albeit following first line nilotinib plus IFN induction therapy [20]—it clearly contrasts with a large body of indirect evidence that had implied a potential clinical value for IFN in improving TFR outcomes in the TKI era.

This discrepancy is noteworthy, given that IFN monotherapy induces complete cytogenetic responses in approximately 20% of CML patients [42,43,44,45], a considerable proportion of whom may achieve durable treatment-free remission after IFN discontinuation [6]. In addition, IFN has been shown to intensifying molecular responses when combined with TKI therapy [14,15,16,17], which is clinically relevant because early and deep molecular remission is a well-established prerequisite for achieving successful TFR [23]. Furthermore, in vivo studies have demonstrated IFN-induced expansion of CML-specific cytotoxic T and NK cells [10,11,12,13, 19, 35, 46,47,48]. Collectively, these findings supported the hypothesis that IFN might augment durable disease control in TKI-pretreated patients by enhancing immunological effector mechanisms following TKI cessation.

However, the ENDURE study results do not support this assumption. IFN maintenance failed to improve the probability of sustained TFR in patients who had received standard TKI monotherapy, demonstrating that, in unselected patients, IFN provides no additional benefit beyond what is already achieved through long-term TKI therapy [37, 48]. Poor tolerability is an unlikely explanation for this outcome, as dose reductions were infrequent and severe adverse events rare. In fact, owing to its novel biochemical and pharmacological characteristics, ropeg-IFN has a markedly favorable toxicity profile compared to conventional IFN formulations or pegylated variants [16, 38].

Although the ENDURE trial failed to confirm a benefit in its primary endpoint, it was crucial in objectively testing and contextualizing previous non-randomized or translational evidence that had suggested an interferon-related improvement in TFR rates. In this sense, the ENDURE trial may be regarded as concluding the long-standing exploration of IFN-based strategies in CML, pending a clearer mechanistic distinction between IFN- and TKI-associated pathways to TFR.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Saußele S, Pfirrmann M, Krause S, Kolb HJ, et al. Assessment of imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: 10-year survival results of the randomized CML study IV and impact of non-CML determinants. Leukemia. 2017;31:2398–406.

Hochhaus A, Larson RA, Guilhot F, Radich JP, Branford S, Hughes TP, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:917–27.

Saußele S, Richter J, Hochhaus A, Mahon F-X. The concept of treatment-free remission in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:1638–47.

Lai X, Jiao X, Zhang H, Lei J Mechanism of treatment-free remission in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia revealed by a computational model of CML evolution. bioRxiv 2022, 2022.05.20.492875.

Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Silver RT, Schiffer C, Apperley JF, Cervantes F, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34:966–84.

Bonifazi, Vivo F, de A, Rosti G, Guilhot F, Guilhot J, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia and interferon-α: a study of complete cytogenetic responders. Blood. 2001;98:3074–81.

Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–86.

Diamond MS, Kinder M, Matsushita H, Mashayekhi M, Dunn GP, Archambault JM, et al. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1989–2003.

Marrack P, Kappler J, Mitchell T. Type I Interferons Keep Activated T Cells Alive. J Exp Med. 1999;189:521–30.

Molldrem JJ, Lee PP, Kant S, Wieder E, Jiang W, Lu S, et al. Chronic myelogenous leukemia shapes host immunity by selective deletion of high-avidity leukemia-specific T cells. J Clin Investig. 2003;111:639–47.

Molldrem JJ, Lee PP, Wang C, Felio K, Kantarjian HM, Champlin RE, et al. Evidence that specific T lymphocytes may participate in the elimination of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Nat Med. 2000;6:1018–23.

Burchert A, Müller MC, Kostrewa P, Erben P, Bostel T, Liebler S, et al. Sustained Molecular Response With Interferon Alfa Maintenance After Induction Therapy With Imatinib Plus Interferon Alfa in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1429–35.

Burchert A, Wölfl S, Schmidt M, Brendel C, Denecke B, Cai D, et al. Interferon-α, but not the ABL-kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571), induces expression of myeloblastin and a specific T-cell response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:259–64.

Preudhomme C, Guilhot J, Nicolini FE, Guerci-Bresler A, Rigal-Huguet F, Maloisel F, et al. Imatinib plus Peginterferon Alfa-2a in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2511–21.

Simonsson B, Gedde-Dahl T, Markevärn B, Remes K, Stentoft J, Almqvist A, et al. Combination of pegylated IFN-α2b with imatinib increases molecular response rates in patients with low- or intermediate-risk chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3228–35.

Baccarani M, Martinelli G, Rosti G, Trabacchi E, Testoni N, Bassi S, et al. Imatinib and pegylated human recombinant interferon-α2b in early chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;104:4245–51.

Nicolini FE, Etienne G, Dubruille V, Roy L, Huguet F, Legros L, et al. Nilotinib and peginterferon alfa-2a for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia (NiloPeg): a multicentre, non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Haematology. 2015;2:e37–e46.

Shah NP, Bhatia R, Altman JK, Amaya M, Begna KH, Berman E, et al. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, Version 2.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2024;22:43–69.

Burchert A, Saussele S, Eigendorff E, Müller MC, Sohlbach K, Inselmann S, et al. Interferon alpha 2 maintenance therapy may enable high rates of treatment discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:1331–5.

Hochhaus A, Burchert A, Saussele S, Baerlocher GM, Mayer J, Brümmendorf TH, et al. Treatment Free Remission after Nilotinib Plus Peg-Interferon Alpha Induction and Peg-Interferon Alpha Maintenance Therapy for Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients; The Tiger Trial. Blood. 2023;142:446.

Rousselot P, Charbonnier A, Cony-Makhoul P, Agape P, Nicolini FE, Varet B, et al. Loss of Major Molecular Response As a Trigger for Restarting Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy in Patients With Chronic-Phase Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Who Have Stopped Imatinib After Durable Undetectable Disease. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:424–30.

Mahon F-X. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase therapy in CML. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:187–93.

Saussele S, Richter J, Guilhot J, Gruber FX, Hjorth-Hansen H, Almeida A, et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukaemia (EURO-SKI): a prespecified interim analysis of a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised, trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:747–57.

Ross DM, Branford S, Seymour JF, Schwarer AP, Arthur C, Yeung DT, et al. Safety and efficacy of imatinib cessation for CML patients with stable undetectable minimal residual disease: results from the TWISTER study. Blood. 2013;122:515–22.

Imagawa J, Tanaka H, Okada M, Nakamae H, Hino M, Murai K, et al. Discontinuation of dasatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained deep molecular response for longer than 1 year (DADI trial): a multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e528–e535.

Shah NP, García-Gutiérrez V, Jiménez-Velasco A, Larson SM, Saussele S, Rea D, et al. Treatment-free remission after dasatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia in chronic phase with deep molecular response: Final 5-year analysis of DASFREE. Br J Haematol. 2023;202:942–52.

Hochhaus A, Masszi T, Giles FJ, Radich JP, Ross DM, Casares MTG, et al. Treatment-free remission following frontline nilotinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: results from the ENESTfreedom study. Leukemia. 2017;31:1525–31.

Radich JP, Hochhaus A, Masszi T, Hellmann A, Stentoft J, Casares MTG, et al. Treatment-free remission following frontline nilotinib in patients with chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: 5-year update of the ENESTfreedom trial. Leukemia. 2021;35:1344–55.

Rousselot P, Huguet F, Rea D, Legros L, Cayuela JM, Maarek O, et al. Imatinib mesylate discontinuation in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in complete molecular remission for more than 2 years. Blood. 2007;109:58–60.

Zhang Z, Zhou X, Zhou X, Cheng Z, Hu Y. Exploration of treatment-free remission in CML, based on molecular monitoring. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e6849.

Vetrie D, Helgason GV, Copland M. The leukaemia stem cell: similarities, differences and clinical prospects in CML and AML. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:158–73.

Inselmann S, Wang Y, Saussele S, Fritz L, Schütz C, Huber M et al. Development, function and clinical significance of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res 2018; 78: canres.1477.2018.

Schütz C, Inselmann S, Sausslele S, Dietz CT, Müller MC, Eigendorff E, et al. Expression of the CTLA-4 ligand CD86 on plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) predicts risk of disease recurrence after treatment discontinuation in CML. Leukemia. 2017;31:829–36.

Ilander M, Olsson-Strömberg U, Schlums H, Guilhot J, Brück O, Lähteenmäki H, et al. Increased proportion of mature NK cells is associated with successful imatinib discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31:1108–16.

Huuhtanen J, Adnan-Awad S, Theodoropoulos J, Forstén S, Warfvinge R, Dufva O, et al. Single-cell analysis of immune recognition in chronic myeloid leukemia patients following tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation. Leukemia. 2024;38:109–25.

Rea D, Henry G, Khaznadar Z, Etienne G, Guilhot F, Nicolini F, et al. Natural killer-cell counts are associated with molecular relapse-free survival after imatinib discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukemia: the IMMUNOSTIM study. Haematologica. 2017;102:1368–77.

Hughes A, Clarson J, Tang C, Vidovic L, White DL, Hughes TP, et al. CML patients with deep molecular responses to TKI have restored immune effectors and decreased PD-1 and immune suppressors. Blood. 2017;129:1166–76.

Gisslinger H, Klade C, Georgiev P, Krochmalczyk D, Gercheva-Kyuchukova L, Egyed M, et al. Long-Term Use of Ropeginterferon Alpha-2b in Polycythemia Vera: 5-Year Results from a Randomized Controlled Study and Its Extension. Blood. 2020;136:33.

Gisslinger H, Zagrijtschuk O, Buxhofer-Ausch V, Thaler J, Schloegl E, Gastl GA, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b, a novel IFNα-2b, induces high response rates with low toxicity in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2015;126:1762–9.

Cross NCP, White HE, Colomer D, Ehrencrona H, Foroni L, Gottardi E, et al. Laboratory recommendations for scoring deep molecular responses following treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:999–1003.

Pfirrmann M, Baccarani M, Saussele S, Guilhot J, Cervantes F, Ossenkoppele G, et al. Prognosis of long-term survival considering disease-specific death in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:48–56.

Leukemia ICSG, On CM, Tura S, Baccarani M, Zuffa E, Russo D, et al. Interferon Alfa-2a as Compared with Conventional Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:820–5.

Guilhot F, Chastang C, Michallet M, Guerci A, Harousseau J-L, Maloisel F, et al. Interferon Alfa-2b Combined with Cytarabine versus Interferon Alone in Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:223–9.

Talpaz M, Kantarjian HM, McCredie KB, Keating MJ, Trujillo J, Gutterman J. Clinical investigation of human alpha interferon in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1987;69:1280–8.

Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Cortes JE, Shan J, Giles FJ, Rios MB, et al. Complete cytogenetic and molecular responses to interferon-α-based therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia are associated with excellent long-term prognosis. Cancer. 2003;97:1033–41.

Kreutzman A, Rohon P, Faber E, Indrak K, Juvonen V, Kairisto V, et al. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients in Prolonged Remission following Interferon-α Monotherapy Have Distinct Cytokine and Oligoclonal Lymphocyte Profile. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23022.

Kreutzman A, Juvonen V, Kairisto V, Ekblom M, Stenke L, Seggewiss R, et al. Mono/oligoclonal T and NK cells are common in chronic myeloid leukemia patients at diagnosis and expand during dasatinib therapy. Blood. 2010;116:772–82.

Naismith E, Steichen J, Sopper S, Wolf D. NK Cells in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN). Cancers. 2021;13:4400.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank AOP Health for supporting the realization of the trial and providing ropeg-IFN. We especially thank Dr. Christoph Klade and Dr. Kurt Krejcy from AOP Health for their valuable discussions on the trial design, conduct, and data interpretation. We are grateful to Sonja Huehn, Agathe Gruenewald, Gavin Giel and Nicole Loewer for their excellent technical assistance. We thank the members of the German CML Study Group for cooperation.

Funding

The sponsor of the ENDURE trial was the Philipps University Marburg. This work was supported by an academic grant of the Deutsche Krebshilfe (DKH 70112020 und 70112841), by the German Research Society (DFG) Graduate School (GRK2573), by the European Leukemia Network EUTOS for CML and by a scientific grant of the Carreras Leukemia Foundation (16 R/2019 to AB). CM was supported by a clinician scientist program of the Phillipps University of Marburg, Germany. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB raised funding for the study. AB, AH, SS, MP and CSB wrote the study protocol. AB, CM, FEN, PC, SS, AH, SKM, NG, MC, PS, MB, MPR, AGB, TI, MEG, PH, LLT, GNF, FL, SWK, RM, MK, FS, CL, GE, AS, JRG, TW, MAS and HGH recruited and treated patients within the study. MP, AB, CM, BA, MW, PK, KP, HG, MH and KW analyzed thedata. AB, CM, MP and PK wrote the manuscript. All authors read, corrected and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AB: research support: Novartis, AOP Health; honoraria: Novartis, Incite, AOP Health; FN: consultancy : Incyte Biosciences, Novartis, Kumquat biosciences; advisory boards: Novartis, Terns Pharmaceuticals, BMS/Celgene; honoraria: Novartis, GSK, Incyte Biosciences; PlC: honoraria: Novartis, Incyte, Enliven; SS: honoraria: Novartis, Incyte, Zentiva, Roche; research support: Novartis, BMS, Incyte; AH: research support: Novartis, BMS, Pfizer, Incyte, TERNS, Eliven; honoraria: Novartis; GE: consultancy: Incyte Biosciences, Novartis; advisory boards: Novartis, BMS; honoraria: Novartis, Incyte Biosciences; JG: honoraria: Incyte, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals; consultancy: Incyte, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals; SWK: honoraria: Eickeler; Travel support: Jazz, Alexion, Abbvie; MC: advisory Board: Novartis, Incyte; travel support: Novartis, Incyte; PS: consultancy/membership on a board or advisory committee: Novartis, AOP Orphan, Incyte, Pfizer; honoraria: Novartis, Pfizer; congress and travel support: Novartis, AOP Orphan; stock in publicly-traded company: Novartis; MR: Travel support: SOBI, AOP, AbbVie, Johnson & Johnson, BeOne. consultancy fees, honoraria: Pfizer, Novartis, MSD, GSK, BeOne, BMS, AOP; GNF: honoraria: Novartis, Zentiva, advisory board: Novartis, Zentiva; CM: honoraria: Incyte, Novartis. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burchert, A., Nicolini, F.E., le Coutre, P. et al. Randomized phase 3 trial of Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus surveillance after tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukemia (ENDURE/CML-IX). Leukemia 40, 410–417 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02859-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02859-1