Abstract

Nonlinear optics plays an important role in many areas of science and technology. The advance of nonlinear optics is empowered by the discovery and utilization of materials with growing optical nonlinearity. Here we demonstrate an indium gallium phosphide (InGaP) integrated photonics platform for broadband, ultra-efficient second-order nonlinear optics. The InGaP nanophotonic waveguide enables second-harmonic generation with a normalized efficiency of 128, 000%/W/cm2 at 1.55 μm pump wavelength, nearly two orders of magnitude higher than the state of the art in the telecommunication C band. Further, we realize an ultra-bright, broadband time-energy entangled photon source with a pair generation rate of 97 GHz/mW and a bandwidth of 115 nm centered at the telecommunication C band. The InGaP entangled photon source shows high coincidence-to-accidental counts ratio CAR > 104 and two-photon interference visibility > 98%. The InGaP second-order nonlinear photonics platform will have wide-ranging implications for non-classical light generation, optical signal processing, and quantum networking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of nonlinear optics is empowered by the invention of nonlinear materials, from bulk nonlinear crystals and silica fibers to more recent wafer-scale thin-film materials. Over the past decades, the application of materials with increasing nonlinearities, combined with the advance of light-confining nanophotonic structures, has resulted in a remarkable enhancement in nonlinear optical efficiencies. For example, the second-harmonic generation has advanced from the initial demonstration using a quartz crystal with a 10−9%/W efficiency1 to the record of 105 − 106%/W achieved in thin-film nanophotonic resonators nowadays2,3.

Second-order (χ(2)) optical nonlinearity, as the dominant optical nonlinearity, enables a variety of nonlinear optical processes with high efficiencies and low noises, including the generation of entangled photons4 and squeezed light5, parametric optical amplification6, and coherent wavelength conversion7. Figure 1a displays the second-order susceptibility and cutoff wavelength of a selection of χ(2) materials that are available in thin-film platforms. Among them, III-V semiconductors, including GaAs and AlxGa1−xAs, are notable for the very high second-order susceptibility, leading to a long history of study for nonlinear optics8. The versatile III-V photonics platform enables heteroeptaxial integration of pump lasers and photodetectors, which is unique compared to other platforms. However, one drawback of these III-V semiconductors is the optical losses at short wavelengths. For example, GaAs has a narrow bandgap corresponding to a cutoff wavelength of 872 nm. While AlxGa1−xAs exhibits a wider bandgap, its second-order susceptibility decreases drastically with the increasing aluminum composition9. Moreover, arsenic III-V materials suffer from strong optical absorption at wavelengths less than 800 nm, due to the antibonding As-As surface state that is below the bandgap10,11,12. These facts have limited the use of arsenic III-V materials for efficient second-order nonlinear optics in the important telecommunication C band (1530-1565 nm), where long-haul optical communications conducts, due to the absorption of the corresponding second harmonics.

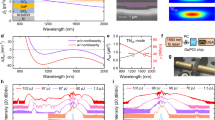

a Second-order susceptibility and cutoff wavelength of several nonlinear optical thin-film materials. The red line indicates the 775 nm wavelength. Shaded region indicates optical absorption at wavelengths longer than 775 nm. AlN:43, LiNbO3:44, GaN:45, SiC:46, GaP:47, AlGaAs:9, GaAs:47, InGaP:22. b SEM images of InGaP photonic integrated circuits. c Intrinsic quality factor of the 1550 nm TE00 and 775 nm TM00 resonances of R = 5μm InGaP microring resonators (inset) with SiO2 and Al2O3 claddings. Inset shows the electric field distribution of the two modes. d Second-harmonic generation in a R = 5μm phase-matched InGaP microring resonator with Al2O3 cladding. On-chip pump power is 40.6 nW and the peak SHG efficiency is 440,000 %/W

Indium gallium phosphide (In0.5Ga0.5P, hereafter referred to as InGaP) is another III-V semiconductor material that is lattice-matched with GaAs and thus can be epitaxially grown on the GaAs substrate at the wafer scale. Because of its high electron mobility, direct bandgap, and thermal stability, InGaP has been used for making heterojunction bipolar transistors13, solar cells14, photodetectors15, and LEDs16. More recently, thin-film InGaP has been explored for third-order nonlinear optics using its substantial Kerr nonlinearity17,18, resulting in demonstrations of frequency combs19, optical parametric oscillators20, and entangled photon pairs via four-wave mixing21.

Besides its notable Kerr nonlinearity, InGaP is particularly appealing for second-order nonlinear optics because of the combination of a substantial second-order susceptibility (\({\chi }_{xyz}^{(2)}\approx\) 220 pm/V22) and a sizable bandgap of 1.92 eV (cutoff wavelength 645 nm). For InGaP, the antibonding anion state lies well above the bandgap11, in contrast to AlxGa1−xAs, which avoids light absorption before the bandgap. InGaP also has a large refractive index ( > 3), which facilitates nanophotonic structures with strong light confinement. These properties suggest the potential of InGaP for realizing highly efficient second-order nonlinear optics, in particular, in the crucial telecommunication C band. Recently, several research groups have embarked on studying second-order nonlinear optics using thin-film InGaP3,23,24. Despite demonstrating a record nonlinearity-to-loss ratio in InGaP microring resonators3, most demonstrations thus far are still limited by considerable optical losses and imperfect phase-matching condition. Moreover, InGaP microcavities demonstrated in Ref. 3 are unsuitable for applications that demand broadband operation and high optical powers. As a result, realizing a broadband, low-loss, ultra-efficient second-order nonlinear photonics platform based on InGaP remains elusive.

Here, through the optimization of optical losses and phase-matching condition for InGaP nanophotonic waveguides across an octave wavelength span, we demonstrate a broadband, ultra-efficient InGaP second-order nonlinear photonics platform in the telecommunication band. The demonstrated second-harmonic generation with a normalized efficiency of 128,000%/W/cm2 in the telecommunication C band is nearly two orders of magnitude more efficient than the state of the art25,26. Using the InGaP nanophotonic waveguide, we demonstrate an ultra-bright time-energy entangled photon source with a pair generation rate of 97 GHz/mW and a bandwidth of 115 nm (14.4 THz) centered at the telecommunication C band. The broadband, ultra-efficient InGaP nanophotonics platform will enable a wide range of nonlinear optical processes and applications with unprecedented performances.

Results

In this study, 110 nm thick InGaP is epitaxially grown on the GaAs substrate (0 degree off-cut toward [110]) using metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (T=545 C, V/III=280, with precursors including trimethylindium, trimethylgallium, and PH3). The root-mean-square (RMS) surface roughness of the InGaP thin film is measured to be about 0.3 nm, which is close to the native surface roughness of the GaAs substrate. To fabricate InGaP photonic integrated circuits, bonding of InGaP thin film to low-index substrates have been demonstrated before24,27. Here we adopted a transfer-free approach to fabricate InGaP photonic integrated circuits with low-index oxide top claddings (Methods)3. Figure 1b shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of fabricated InGaP photonic integrated circuits, including microring resonators and waveguides.

We studied the optical loss of InGaP nanophotonic devices in both 1550 nm and 775 nm wavelength bands with two different oxide claddings, SiO2 and Al2O3, deposited via atomic layer deposition. The optical loss is characterized using the intrinsic quality factor (\({Q}_{i}\equiv \frac{\omega }{{\kappa }_{i}}\)) of InGaP microring resonators. The microring resonator couples with both 1550 nm and 775 nm wavelength-band waveguides, which enable measurement of the transmission spectrum of the device3. Qi is then inferred from the fitting of the resonance spectrum. Figure 1c shows the measured Qi of the 1550 nm band fundamental transverse-electric (TE00) resonance and the 775 nm band fundamental transverse-magnetic (TM00) resonance of microring resonators with 5 μm radius and 1 μm width. The average value of Qi,1550 for microring resonators with Al2O3 cladding is about 6 × 105, over three times higher than that with SiO2 cladding. Qi,775 is 1 − 2 × 105 and shows slight improvement with Al2O3 cladding. The increase of the quality factor could be attributed to the surface passivation induced by Al2O328. We also made microrings with different sizes and found Qi,1550 is peaked around 8 × 105 for larger rings, which is limited by the absorption loss (see Section S2 of the Supplementary Information). Leveraging the optimized optical loss, we measured second-harmonic generation (SHG) in a 5-μm-radius ring with phase-matched 1550 nm band TE00 and 775 nm band TM00 resonances and realized a resonant nonlinear conversion efficiency \(\eta \equiv {P}_{{\rm{SHG}}}/{P}_{p}^{2}=440,000 \%\)/W (Fig. 1d). This represents a 6-fold enhancement over the previously reported value using the same InGaP microring resonator but with SiO2 cladding3.

In contrast to cavities, waveguides can be operated in the broadband regime and circumvent the light extraction issue associated with cavities. Similar to the microring resonator, the InGaP waveguide is designed for phase matching between the 1550 nm band TE00 mode a and the 775 nm band TM00 mode b, which satisfy 2ωa = ωb and 2ka = kb. Lacking the birefringence in InGaP, phase matching is achieved by dispersion engineering of the InGaP nanophotonic waveguide. By designing the waveguide width, the effective index of the 1550 nm band TE00 mode and the 775 nm band TM00 mode can be equalized, as shown in Fig. 2a using finite element simulation. For the phase-matched waveguide with length L, the normalized SHG efficiency, \({\eta }_{{\rm{SHG}}}\equiv \frac{{P}_{{\rm{SHG}}}}{{P}_{p}^{2}{L}^{2}}\), can be calculated using29

where na(b) is the effective mode index of the fundamental(second)-harmonic mode and the normalization integrals use electric field components perpendicular to the wavevector of the waveguide mode. The SHG efficiency is optimized when the waveguide is aligned along the (110) direction of InGaP, leading to simulated ηSHG = 130,000%/W/cm2 for the 1550 nm pump wavelength (see Section S3 of the Supplementary Information).

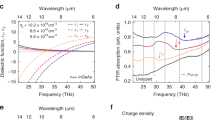

a Simulated effective mode index of 1550 nm TE00 and 775 nm TM00 modes of 108 nm (dashed), 110 nm (solid), and 112 nm (dotted) thick InGaP waveguides with 35 nm Al2O3 cladding. Inset is a cross section of the waveguide along with the electric field distribution of the two modes. b SEM images of a fabricated InGaP waveguide device. c Measured SHG spectrum for a 1.6 mm long waveguide device with a pump power of 1.56 mW. d Quadratic relation between the peak SHG power and the pump power. e Temperature tuning of the phase-matching condition. f Normalized SHG efficiency and 1550 nm wavelength band loss of the telecommunication C band waveguide SHG of several thin-film second-order nonlinear photonics platforms. InGaP: this work, PPLN:25, Al0.27Ga0.73As:48, GaP:49, SiC:50

Figure 2b displays SEM images of a fabricated meander waveguide with a length of 1.6 mm. The waveguide connects to two adiabatically tapered couplers at the end to interface with tapered optical fibers for light transmission. The adiabatic coupler efficiency is approximately 80% and 30% for 1550 nm TE and 775 nm TM polarized light, respectively3. The waveguide width is tapered down before entering the 180° turn to avoid mode interference due to the bending of the multimode waveguide. The SHG nonlinear transfer function of the meander waveguide is given by \({\left(\frac{\sin N(x+\phi )}{N\sin (x+\phi )}\frac{\sin x}{x}\right)}^{2}\) (Methods), where \(x=\frac{\Delta k{L}_{0}}{2}\), Δk = 2kω − k2ω, L0 is the length of the waveguide in one row, N is the number of rows, and 2ϕ is the total phase mismatch between the two modes in a 180° turn. For phase-matched fundamental- and second-harmonic modes in the straight waveguide, they become phase mismatched in the turn because of the change of the waveguide width and waveguide bending. A narrow waveguide section with a tunable length (Fig. 2b inset) is introduced to compensate the phase mismatch due to the bending waveguide such that the total phase mismatch 2ϕ through the 180° turn, including the tapering section, is multiple 2π. As a result, the transfer function can be recovered to the ideal sinc2 function.

A tunable continuous-wave telecom band laser is employed for the measurement of second-harmonic generation (laser output power 15 mW and linewidth <200 kHz (50 ms integration time)). The output light from the waveguide passes through a 1550 nm/775 nm wavelength division multiplexer (WDM) to filter the residual pump before the second-harmonic intensity is measured. Figure 2c shows the SHG intensity of a 1.6 mm long waveguide as the pump wavelength is swept, where a peak on-chip SH power PSHG = 80μW is observed for the pump wavelength 1542.1 nm and an on-chip pump power Pp = 1.56 mW. This corresponds to a normalized SHG efficiency of 128,000%/W/cm2. In comparison, normalized SHG efficiency of 2,500%/W/cm2 was achieved in lossy InGaP waveguides with phase-matched higher-order modes before23. A quadratic relationship between PSHG and Pp is observed in the pump non-depleted region (Fig. 2d). Additionally, we explored the tunability of the waveguide’s phase-matching condition through temperature tuning of the device. In Fig. 2e, we present the measured SHG spectrum at several temperatures up to 95°C, constrained by the thermoelectric cooler element. A tuning range of 12.7 nm and a temperature-induced shift of 0.17 nm/°C in the phase-matching wavelength are measured. The redshift of phase-matching wavelength is consistent with the previously observed thermal-optical effect of the TE00 and TM00 modes of InGaP microrings3. The SHG efficiency is stable and continuous in the entire tuning range. The slight fluctuation seen in Fig. 2e is due to the re-alignment of fiber coupling for different temperature.

The SHG efficiency realized in the InGaP nonlinear nanophotonic waveguide represents a substantial advance, in particular, in the crucial telecommunication band. Figure 2f displays the normalized SHG efficiency and 1550 nm band loss of the best telecommunication C band waveguide SHG, to our knowledge, of several χ(2) nonlinear photonics platforms (a more comprehensive list is provided in Section S7 of the Supplementary Information). The InGaP nanophotonic waveguide surpasses thin-film PPLN waveguides by nearly two orders of magnitude in terms of normalized nonlinear conversion efficiency25,26, while maintaining a low 1550 nm wavelength loss of 0.8 ± 0.4 dB/cm, which is consistent with the measured Qi of microring resonators (equivalent to 0.4 dB/cm). The ratio of the normalized nonlinear efficiency between the InGaP and thin-film PPLN waveguides can be estimated using Eq. (1): \({(4\times 2\times \frac{\pi }{2})}^{2}\approx 160\), where 4 × is from \({\chi }_{xyz}^{(2)}\) of InGaP versus \({\chi }_{zzz}^{(2)}\) of LiNbO3, 2 × is from the swap of indices x and y in \({\chi }_{xyz}^{(2)}\) for the TE00 mode, and \(1/\frac{2}{\pi }\times\) is due to the periodic poling of LiNbO3. On the other hand, the InGaP waveguide is slightly disadvantageous in terms of mode overlap because of the high-aspect-ratio cross section leading to less field confinement. The nonlinear efficiency of \({P}_{{\rm{SHG}}}/{P}_{p}^{2}=3280\)%/W achieved in the 1.6 mm long InGaP waveguide is comparable to the centimeter-long PPLN waveguide made with the adapted poling technique recently26. For longer InGaP waveguides, we find the nonlinear efficiency deviates from the L2 scaling because of the thickness nonuniformity of the thin film (see Section S4 of the Supplementary Information). This can be mitigated using the adapted phase-matching technique26, by varying the waveguide width according to the pre-calibrated InGaP film thickness to keep the phase-matching condition along the entire waveguide.

Utilizing the InGaP nonlinear nanophotonic waveguide, we demonstrate an ultra-bright, broadband time-energy entangled photon source via spontaneous parametric down-conversion (SPDC). For a phase-matched nonlinear waveguide, the internal efficiency of the pair generation via SPDC can be related to the SHG efficiency by30

where \({\rm{GVD}}\,\left(\frac{{\omega }_{p}}{2}\right)\) is the group velocity dispersion at \(\frac{{\omega }_{p}}{2}\), \(\alpha =\frac{1}{\pi }\sqrt{2{{\rm{sinc}}}^{-1}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}\), and ΔfFWHM is the bandwidth of the SPDC photons given by

We pumped the phase-matched waveguide with a tunable 780 nm band continuous-wave laser to generate telecommunication band SPDC photons. After filtering the residual pump, the SPDC photons were measured using either regular photodetectors or superconducting-nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs). Figure 3a shows the total photon pair generation rate efficiency via a 1.6 mm long waveguide measured with Pp = 135μW. At the phase-matching wavelength of 772.12 nm, a peak pair generation rate of 97 GHz/mW, corresponding to an internal efficiency of 2.5 × 10−5, is observed. To measure the bandwidth of the SPDC photons, we used a dense wavelength division-multiplexer (DWDM) with 40 channels and a 120 GHz channel bandwidth. The measured SPDC photon rate through each channel for Pp = 8.7μW is displayed in Fig. 3b (the fiber coupling is not optimized for this measurement). The data is fitted using a sinc2 function and the SPDC photon bandwidth is inferred to be 14.4 THz (115 nm). The measured bandwidth agrees with the theoretical calculation using Eq. (3) (see Section S5 of the Supplementary Information). This leads to a per-bandwidth pair generation rate of 6.7 GHz/mW/THz (840 MHz/mW/nm). In Table 1, we compare the telecommunication C band SPDC photon pair generation in the InGaP waveguide and thin-film (TF) PPLN waveguides of several recent works. The InGaP waveguide SPDC source shows a rate efficiency at least an order of magnitude higher while retaining a large bandwidth. Since the per-bandwidth pair generation rate is ∝ ηSHGL2, according to Eq. (2), such an enhancement is expected for the InGaP waveguide based on the normalized SHG efficiency. We also noticed a recent work of high-efficiency telecommunication L band SPDC photon generation in AlGaAs waveguides12. A more comprehensive summary of broadband photon pair sources can be found, for example, in Ref. 31.

a Dependence of the total SPDC pair generation rate (PGR) efficiency on the pump wavelength. b SPDC spectrum sampled by a DWDM with Pp = 8.7 μW. The solid line is a sinc2 function fitting, yielding a bandwidth of 115 nm (14.4 THz). c Measured \({g}_{{\rm{si}}}^{(2)}(\tau )\) for PGR = 18 MHz in one DWDM channel. Solid line is Gaussian fitting. d Pair generation rate in one DWDM channel and coincidence-to-accidental counts ratio (CAR) for various pump powers. Solid lines are linear fitting

The second-order cross-correlation, \({g}_{{\rm{si}}}^{(2)}(\tau )\), between the signal and idler photons via two DWDM channels was measured using a pair of SNSPDs. Figure 3c displays the measured \({g}_{{\rm{si}}}^{(2)}(\tau )\) for pair generation rate of 18 MHz in one DWDM channel. In the low gain regime, the zero-delay cross-correlation between the signal and idler is shown to be32

where R and B are the total pair generation rate and bandwidth of the SPDC photons, respectively, and Γs,i is the filter bandwidth of the signal and idler photons. For Γs = Γi, Eq. (4) indicates the inherent coincidence-to-accidental counts ratio (CAR) of the SPDC photon source is given by \({\rm{CAR}}={g}_{{\rm{si}}}^{(2)}(0)-1=B/R\), i.e., the inverse of the photon pair rate per bandwidth. According to Eq. (2) (B ≡ ΔfFWHM and R ≡ PSPDC/ℏωp), CAR ∝ 1/(ηSHGL2Pp), which means for more efficient waveguides, same CAR can be achieved with less pump power. Due to the detector jitter ( ~ 100 ps), which is much larger than the coherence time of the SPDC photons filtered by a DWDM channel (120 GHz), the inherent \({g}_{{\rm{si}}}^{(2)}(0)\) cannot be resolved and the measured CAR will be lower than the inherent value32. The measured CAR and pair generation rate in one DWDM channel for various pump power is shown in Fig. 3d (Methods). Nevertheless, CAR > 104 is observed for relatively low photon pair generation rate.

To demonstrate the time-energy entanglement of the SPDC photons, we measured the two-photon interference using an unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometer (MZI)33, as illustrated in Fig. 4a (Methods). The unbalanced MZI is made from glass-based photonic integrated circuits with a path delay of τd = 1 ns. The SPDC photons used in this measurement have a bandwidth of about 20 nm as they are filtered by a CWDM, leading to a single-photon coherence time much shorter than τd. The coherence time of the correlated signal-idler pair is determined by the continuous-wave pump laser, which is much longer than τd. As a result, the signal-idler photon pair can interfere through the unbalanced MZI while neither can the signal or idler single photon. The signal-idler pair can travel through either the short (s) or long (l) path of the unbalanced MZI together, forming a time-energy entangled state \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert s\right\rangle }_{1}{\left\vert s\right\rangle }_{2}+{e}^{2i\phi }{\left\vert l\right\rangle }_{1}{\left\vert l\right\rangle }_{2})\), where ϕ is the phase difference between the two paths for light with a frequency that is half of the SPDC pump frequency. This entangled state can be post-selected, distinguishing itself from the other two states out of the interferometer, \({\left\vert s\right\rangle }_{1}{\left\vert l\right\rangle }_{2}\) and \({\left\vert l\right\rangle }_{1}{\left\vert s\right\rangle }_{2}\), using time-resolved coincidence detection (Methods).

a Schematic of the measurement of the time-energy entanglement of the SPDC photons. VOA: variable optical attenuator. FPC: fiber polarization controller. b Two-photon time difference histogram. The binwidth is 10 ps. The middle peak corresponds to the time-energy entangled state. c Coincidence counts in 800 ps binwidth integrated in 15 s of the SPDC photon pair for various interferometer phases (red) and the interference fringe of a CW laser (blue). Solid lines are sinusoidal function fitting. Error bars represent the shot noise. d Counts in 5 ms of SPDC photons in one SNSPD

Figure 4b shows a measured time difference histogram of the SPDC photons. The coincidence counts around the zero delay, corresponding to the entangled state, depend on the interferometer phase as \(\propto \frac{1}{2}(1+\cos 2\phi )\). Figure 4c shows the measured two-photon interference fringe by varying the temperature of the glass interferometer which changes ϕ. The two-photon fringe has a period of π while the fringe of a continuous-wave laser with a frequency about half of the pump frequency has a period of 2π. The counts of SPDC photons in one detector does not exhibit an interference fringe as expected (Fig. 4d). The measured two-photon interference visibility is 90.8%, which is limited by the imperfect glass photonic circuit MZI with the beam splitter ratio deviating from 50/50. The two-photon interference visibility is ≥98.6% after correction for the interferometer imperfection (see Section S6 of the Supplementary Information). The two-photon interference visibility exceeds the Clauser-Horne limit of \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\approx 70.7 \%\), which proves the photon pair entanglement34.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated a broadband second-order nonlinear photonics platform based on thin-film InGaP. With the optimized optical loss and phase-matching condition, the InGaP nanophotonic waveguide enables second-order nonlinear optical processes, including SHG and SPDC, with normalized efficiencies one to two orders of magnitude higher than the state of the art in the telecommunication C band. The nonlinear efficiency of the InGaP waveguides can be further enhanced using the adapted fabrication technique26 to counter the thickness nonuniformity of thin films. The ultra-bright, broadband entangled photon pair source, covering the telecommunication C band, will be useful for high-rate wavelength-multiplexed entanglement distribution over long distances35 and ultrafast spectroscopy using entangled photons36. Beyond that, the demonstrated InGaP nonlinear photonics platform is expected to enable unprecedented performances in applications ranging from squeezed light generation37,38 and optical parametric amplification39 to few-photon quantum nonlinear optics40, among others. Based on III-V semiconductors, the InGaP platform also enables monolithic integration of pump lasers41 to realize electrically-injected nonlinear photonic sources.

Method

Device fabrication

The device fabrication follows Ref. 3. The device pattern is defined using electron beam lithography and transferred to InGaP layer via inductively coupled plasma reactive-ion etch (ICP-RIE) using a mixture of Cl2/CH4/Ar gas. Then a layer of aluminum oxide is deposited via atomic layer deposition. The InGaP device is released from the GaAs substrate using citric acid-based selective etching. See Section S1 of the Supplementary Information for more details.

Measurement

For the measurement of SPDC photons, we used a 780 nm band continuous-wave tunable diode laser as the pump (output power 25 mW and linewidth < 200 kHz (50 ms integration time)). The light is polarization aligned by a fiber polarization controller, coupled into the device via a tapered fiber to generate the SPDC photons, and coupled back into the optical fiber using another tapered fiber. The residual pump is filtered by a 1550 nm/780 nm WDM. To measure the cross-correlation and CAR of the SPDC photons, the signal and idler photons are separated by a DWDM and detected using SNSPDs (Quantum Opus) and time-correlated single-photon counting module (Swabian). The coincidence and accidental counts are integrated in a time binwidth of 10 ps. To measure the time-energy entanglement of the SPDC photons, both signal and idler photons are filtered by the same CWDM channel and then pass through a glass waveguide unbalanced MZI (Teem Photonics). The two-photon coincidences are detected by two SNSPDs after the 50/50 beam splitter.

Nonlinear transfer function

The transfer function of SHG is calculated as

where Δϕ is the phase mismatch between the fundamental- and second-harmonic modes. For a meander waveguide,

where Δk = 2kω − k2ω, L0 is the length of the waveguide in one row, N is the number of rows, and 2ϕ is the total phase mismatch between the two modes for a 180° turn.

Data availability

All data used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Franken, P. A. et al. Generation of optical harmonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 7, 118–119 (1961).

Lu, J. J. et al. Toward 1% single-photon anharmonicity with periodically poled lithium niobate microring resonators. Optica 7, 1654–1659 (2020).

Zhao, M. D. & Fang, K. J. InGaP quantum nanophotonic integrated circuits with 1.5% nonlinearity-to-loss ratio. Optica 9, 258–263 (2022).

Zhao, J. et al. High quality entangled photon pair generation in periodically poled thin-film lithium niobate waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 163603 (2020).

Vahlbruch, H. et al. Detection of 15 dB squeezed states of light and their application for the absolute calibration of photoelectric quantum efficiency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 110801 (2016).

Ledezma, L. et al. Intense optical parametric amplification in dispersion-engineered nanophotonic lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 9, 303–308 (2022).

Guo, X. et al. On-chip strong coupling and efficient frequency conversion between telecom and visible optical modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 123902 (2016).

Vyas, K. et al. Group III-V semiconductors as promising nonlinear integrated photonic platforms. Adv. Phys.: X 7, 2097020 (2022).

Ohashi, M. et al. Determination of quadratic nonlinear optical coefficient of Alx Ga1−x As system by the method of reflected second harmonics. J. Appl. Phys. 74, 596–601 (1993).

Michael, C. et al. Wavelength- and material-dependent absorption in GaAs and AlGaAs microcavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 051108 (2007).

Lin, L. & Robertson, J. Passivation of interfacial defects at III-V oxide interfaces. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 30, 04E101 (2012).

Placke, M. et al. Telecom-Band Spontaneous Parametric Down-Conversion in AlGaAs-on-Insulator Waveguides. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2301293 (2024).

Pan, N. et al. High reliability InGaP/GaAs HBT. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 19, 115–117 (1998).

Takamoto, T. et al. InGaP/GaAs-based multijunction solar cells. Prog. Photovoltaics: Res. Appl. 13, 495–511 (2005).

Jiang, J. et al. High detectivity InGaAs/InGaP quantum-dot infrared photodetectors grown by low pressure metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 2166–2168 (2004).

Svensson, C. P. T. et al. Monolithic GaAs/InGaP nanowire light emitting diodes on silicon. Nanotechnology 19, 305201 (2008).

Eckhouse, V. et al. Highly efficient four wave mixing in GaInP photonic crystal waveguides. Opt. Lett. 35, 1440–1442 (2010).

Colman, P. et al. Temporal solitons and pulse compression in photonic crystal waveguides. Nat. Photonics 4, 862–868 (2010).

Dave, U. D. et al. Dispersive-wave-based octave-spanning supercontinuum generation in InGaP membrane waveguides on a silicon substrate. Opt. Lett. 40, 3584–3587 (2015).

Marty, G. et al. Photonic crystal optical parametric oscillator. Nat. Photonics 15, 53–58 (2021).

Chopin, A. et al. Ultra-efficient generation of time-energy entangled photon pairs in an InGaP photonic crystal cavity. Commun. Phys. 6, 77 (2023).

Ueno, Y., Ricci, V. & Stegeman, G. I. Second-order susceptibility of Ga0.5In0.5P crystals at 1.5 μm and their feasibility for waveguide quasi-phase matching. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14, 1428–1436 (1997).

Poulvellarie, N. et al. Efficient type II second harmonic generation in an indium gallium phosphide on insulator wire waveguide aligned with a crystallographic axis. Opt. Lett. 46, 1490–1493 (2021).

Amores, A. P. & Swillo, M. Low-Temperature Bonding of Nanolayered InGaP/SiO2 Waveguides for Spontaneous-Parametric Down Conversion. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 2550–2557 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Ultrahigh-efficiency wavelength conversion in nanophotonic periodically poled lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 5, 1438–1441 (2018).

Chen, P. K. et al. Adapted poling to break the nonlinear efficiency limit in nanophotonic lithium niobate waveguides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 44–50 (2024).

Dave, U. D. et al. Nonlinear properties of dispersion engineered InGaP photonic wire waveguides in the telecommunication wavelength range. Opt. Express 23, 4650–4657 (2015).

Guha, B. et al. Surface-enhanced gallium arsenide photonic resonator with quality factor of 6 × 106. Optica 4, 218–221 (2017).

Luo, R. et al. Highly tunable efficient second-harmonic generation in a lithium niobate nanophotonic waveguide. Optica 5, 1006–1011 (2018).

Kumar, R. & Ghosh, J. Parametric down-conversion in ppLN ridge waveguide: a quantum analysis for efficient twin photons generation at 1550 nm. J. Opt. 20, 075202 (2018).

Javid, U. A. et al. Ultrabroadband entangled photons on a nanophotonic chip. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 183601 (2021).

Clausen, C. et al. A source of polarization-entangled photon pairs interfacing quantum memories with telecom photons. N. J. Phys. 16, 093058 (2014).

Brendel, J., Mohler, E. & Martienssen, W. Time-resolved dual-beam two-photon interferences with high visibility. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 1142–1145 (1991).

Clauser, J. F. & Horne, M. A. Experimental consequences of objective local theories. Phys. Rev. D. 10, 526–535 (1974).

Wengerowsky, S. et al. An entanglement-based wavelength-multiplexed quantum communication network. Nature 564, 225–228 (2018).

Zhang, Z. D. et al. Entangled photons enabled time-frequency-resolved coherent Raman spectroscopy and applications to electronic coherences at femtosecond scale. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 274 (2022).

Nehra, R. et al. Few-cycle vacuum squeezing in nanophotonics. Science 377, 1333–1337 (2022).

Stokowski, H. S. et al. Integrated quantum optical phase sensor in thin film lithium niobate. Nat. Commun. 14, 3355 (2023).

Riemensberger, J. et al. A photonic integrated continuous-travelling-wave parametric amplifier. Nature 612, 56–61 (2022).

Yanagimoto, R. et al. Temporal trapping: a route to strong coupling and deterministic optical quantum computation. Optica 9, 1289–1296 (2022).

Majid, M. et al. First demonstration of InGaP/InAlGaP based orange laser emitting at 608 nm. Electron. Lett. 51, 1102–1104 (2015).

Jin, H. et al. On-chip generation and manipulation of entangled photons based on reconfigurable lithium-niobate waveguide circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 103601 (2014).

Pernice, W. H. P. et al. Second harmonic generation in phase matched aluminum nitride waveguides and micro-ring resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 223501 (2012).

Wang, C. et al. Second harmonic generation in nano-structured thin-film lithium niobate waveguides. Opt. Express 25, 6963–6973 (2017).

Sanford, N. A. et al. Measurement of second order susceptibilities of GaN and AlGaN. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 053512 (2005).

Sato, H. et al. Accurate measurements of second-order nonlinear optical coefficients of 6H and 4H silicon carbide. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 26, 1892–1896 (2009).

Shoji, I. et al. Absolute scale of second-order nonlinear-optical coefficients. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14, 2268–2294 (1997).

May, S. et al. Second-harmonic generation in AlGaAs-on-insulator waveguides. Opt. Lett. 44, 1339–1342 (2019).

Pantzas, K. et al. Continuous-wave second-harmonic generation in orientation-patterned gallium phosphide waveguides at telecom wavelengths. ACS Photonics 9, 2032–2039 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Efficient second-harmonic generation in silicon carbide nanowaveguides. Proceedings of 2022 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics. San Jose, CA, USA: IEEE 2022, 1–2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by US National Science Foundation (Grant No. ECCS-2223192), NSF Quantum Leap Challenge Institute QLCI-HQAN (Grant No. 2016136), and U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science National Quantum Information Science Research Centers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., J.A. and A.K.M.N.H. performed the simulation. J.A. and Y.M. fabricated the device. J.A., Y.Z., Y.M. and A.K.M.N.H. measured the device and analyzed the data. J.A., Y.Z. and K.F. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akin, J., Zhao, Y., Misra, Y. et al. InGaP χ(2) integrated photonics platform for broadband, ultra-efficient nonlinear conversion and entangled photon generation. Light Sci Appl 13, 290 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01653-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01653-5

This article is cited by

-

Experimental entanglement swapping through single-photon χ(2) nonlinearity

Nature Communications (2025)

-

On-chip quantum states generation by incoherent light

Nature Communications (2025)