Abstract

Optical phase modulators are critical components in integrated photonics, but conventional designs suffer from a trade-off between modulation efficiency and optical loss. Two-dimensional materials like graphene offer strong electro-optic effects, yet their high optical absorption at telecom wavelengths leads to significant insertion losses. Although monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) provide exceptional telecom-band transparency for low-loss electro-refractive response, their practical implementation in phase modulators requires top electrodes to enable vertical electric field tuning, which typically introduces parasitic absorption. Here, we address this challenge by developing hybrid tungsten oxyselenide/graphene (TOS/Gr) electrodes that minimize optical loss while enabling efficient phase modulation in TMD-based devices. The UV-ozone-converted TOS (from WSe2) acts as a heavy p-type dopant for graphene, making the graphene transparent in the NIR region while enhancing its conductivity. Our complete device integrates a hybrid TOS/graphene transparent electrode with a hexagonal boron nitride dielectric spacer and monolayer WS2 electro-optic material on a SiN microring platform. This achieves a high modulation efficiency of 0.202 V·cm while maintaining an exceptionally low extinction ratio change of just 0.08 dB, demonstrating superior performance compared to modulators employing conventional electrodes. Our breakthrough in near-lossless phase modulation opens new possibilities for energy-efficient optical communications, photonic computing, and fault-tolerant quantum networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silicon photonics provides a scalable and efficient platform for integrating optical and electronic functionalities onto a single chip. This addresses the rapidly growing demand for high-speed data communication, advanced information processing, and compact optical systems1,2. As core components of silicon photonics, electro-optic modulators enable dynamic modulation of optical signals through external electric fields3. Traditionally, materials such as doped silicon, germanium, and III–V semiconductors have been employed for this purpose3,4,5,6. However, these conventional materials inherently suffer from significant drawbacks, including high optical losses, substantial power consumption, large device footprints, and limited modulation efficiencies. These limitations severely restrict their scalability and practicality for high-performance, energy-efficient integrated photonic circuits. Consequently, alternative electro-optic materials are being explored to deliver efficient, low-loss, and compact phase modulation7,8,9.

Recently, two-dimensional (2D) materials have emerged as promising candidates for integration into silicon photonic systems, primarily owing to their extraordinary electronic and optical properties, as well as their atomic-scale thickness10,11,12,13. Among various 2D materials, monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are distinguished by their nearly transparent nature and negligible optical absorption in the telecommunication band14,15, making them well-suited for low-loss optical phase modulators. In practical use, electro-optic modulation requires additional transparent electrode materials, including carbon nanotube networks16, metal nanogrids17, and indium tin oxide (ITO)18,19. Compared with these bulky electrodes, graphene is superior in terms of uniform conductivity, low contact resistance, high carrier mobility for high-speed modulation, and its atomic-scale compatibility with other 2D materials, which enable stronger electro-optic coupling and more efficient refractive index control20,21,22,23. However, graphene’s low-energy states near the Fermi level result in considerable optical absorption at telecom wavelengths. This absorption causes insertion losses and compromises modulation efficiency and overall device performance24,25,26,27. Although ionic liquid gating is capable of injecting significantly high charge densities without introducing absorption losses, it suffers from nonlocal charge dispersion, limited chemical stability, and incompatibility with scalable CMOS fabrication processes28,29,30. Therefore, developing electrode materials that simultaneously achieve efficient electrostatic control, optical transparency, and scalability remains a critical challenge for integrated photonic applications.

In this study, we demonstrate optical loss elimination in photonic electrodes through an innovative graphene doping approach using tungsten oxyselenide (TOS), achieved by oxidizing monolayer WSe2. Our hybrid design enables a near-lossless electrode platform with heavily p-doped graphene due to TOS31,32,33, with minimal absorption characteristics at telecommunication wavelengths around 1550 nm. The complete phase modulator integrates a hybrid TOS/graphene transparent electrode with a hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) dielectric spacer and monolayer WS2 electro-optic material on a silicon nitride (SiN) microring platform. The optimized heterostructure (HS) maintains telecom-band transparency while delivering robust electro-optic modulation, overcoming the critical loss-modulation compromise in photonic devices. It provides a promising route for advanced photonic integrated circuits with improved modulation efficiency and reduced power consumption.

Results

We employed SiN as the material for waveguides and microring resonators. Compared with conventional silicon waveguides, SiN waveguides exhibit superior performance due to significantly lower optical losses, broader transparency extending from visible to mid-infrared wavelengths, and excellent compatibility with standard CMOS fabrication processes34,35. Figure 1a presents a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the SiN waveguide (top) alongside its simulated electric field distribution (bottom). The transverse electric (TE) mode is predominantly guided within the waveguide, exhibiting an exponential decay outside the waveguide boundaries. This evanescent field enables strong interaction with the materials deposited on top of the waveguide, allowing modulation of the guided mode via modulation of the refractive index of the deposited materials.

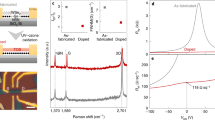

Substantially reduced absorption of TOS/graphene on waveguides. a SEM image (top panel) of the fabricated SiN waveguide on a SiO2/Si substrate, and the simulated electric field distribution (bottom panel) within the waveguide, showing the confined transverse electric (TE) mode. b Schematic of the microring resonator integrated with the TOS/graphene HS. c Energy band diagram of the TOS/graphene interface, highlighting the electron transfer from graphene to TOS. d Simulated transmission spectra of the microring resonator for three different configurations: bare SiN microring resonator, microring integrated with graphene, and microring integrated with the TOS/graphene HS. e Experimental transmission spectra validating the simulation results. Shown are the transmission spectra of a bare microring, a microring integrated with graphene, and a microring integrated with TOS/graphene. Inset: Optical image of the TOS/graphene layer on top of the microring resonator; scale bar: 10 µm

To investigate the near-infrared (NIR) absorption properties of the TOS/graphene HS, we employed the microring resonator, which is designed to be highly sensitive to environmental refractive index changes. TOS/graphene HS was transferred onto the microring by the all-dry transfer method (Fig. 1b). Guided light resonating within the microring interacts with the HS layer on top. TOS (5.6 eV) has a significantly higher work function compared to graphene (4.6 eV)31,32,36, which drives electron migration from graphene into TOS. This charge transfer results in substantial p-doping of the graphene (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Information III). Due to p-doping, graphene’s Fermi level shifts further into the valence band, increasing the energy required for electrons to transition into the conduction band. As a result, incident NIR photons at telecommunication wavelengths cannot meet these energy-momentum matching conditions, significantly eliminating interband optical absorption20.

To investigates the optical behavior of microring resonators, finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations were carried out under three distinct configurations: a bare microring, a microring integrated with pristine graphene, and a microring integrated with a TOS/graphene HS (Fig. 1d). The simulation results reveal that the introduction of pristine graphene leads to both a measurable phase shift and significant optical insertion loss, attributed to its inherent absorption at NIR wavelengths. In contrast, in the heavily p-doped graphene model (TOS/graphene), the microring exhibits a clear phase shift with negligible insertion loss. To verify these predictions, we transferred pristine graphene and TOS/graphene HS (Fig. 1e inset) onto separate microring resonators and measured their transmission spectra (Fig. 1e). In agreement with our calculations, the pristine graphene induces a pronounced reduction in transmission, consistent with increased absorption. In contrast, the TOS/graphene-integrated microring only exhibits a comparable phase shift without any noticeable degradation in transmission intensity. These results clearly confirm that the TOS layer enables optical transparency of graphene at telecom wavelengths, dramatically reducing near-infrared absorption and facilitating near-lossless phase modulation.

To effectively achieve p-doping of graphene, we need to first fully oxidize monolayer WSe2 into TOS using UV-ozone treatment (Supplementary Information II). Following the oxidation process, a noticeable change in the optical contrast of the WSe2 flake was observed, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2a, indicating successful conversion of WSe2 to TOS. The oxidation process can be precisely characterized using Raman and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy (Fig. 2a, b). For WSe2 flakes comprising monolayer and bilayer regions, Raman spectra revealed that the characteristic E2g and A1g peaks completely disappeared after UV-ozone treatment, indicating full oxidation. PL spectroscopy and spatial mapping further supported this finding. The monolayer region initially exhibited strong PL emission, which was completely quenched after oxidation. Conversely, the bilayer region exhibited the opposite behavior, with initially quenched PL becoming enhanced post-oxidation (Fig. 2b inset). These observations confirm the complete oxidation of the top WSe2 layer.

Optical characterization of TOS and TOS/graphene. a Raman spectra of WSe2 flakes before and after complete oxidation, illustrating the disappearance of characteristic WSe2 peaks (E2g and A₁g) post-oxidation. Inset: Optical image showing the WSe2 flake composed of monolayer and bilayer regions. b Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the same WSe2 flake before and after oxidation. Inset: Spatially resolved PL mapping, indicating complete oxidation of monolayer WSe2 and partial oxidation of the bilayer. c Comparison of Raman spectra for pristine graphene and the TOS/graphene HS. A significant decrease in the intensity ratio of 2D to G peaks is observed, indicating heavy p-doping of graphene by the TOS layer. d Sheet resistance (Rsh) measurements of pristine graphene and TOS/graphene HS as a function of gate voltage (Vgate). Upon doping, the charge neutrality point (CNP) shifts from −2.7 V to beyond the measurable voltage range, indicating significant p-doping induced by TOS. Inset: Optical image of a graphene strip with patterned four-probe electrodes used for electrical measurements; scale bar: 20 µm

Subsequently, we investigated the doping effect of TOS on graphene using Raman spectroscopy and electrical measurements. Raman analysis of pristine graphene and TOS/graphene reveals a significant reduction in the intensity ratio of the 2D peak to the G peak (I2D/IG) as shown in Fig. 2c, decreasing from approximately 3 to 1. We also observed a clear blueshift of the 2D peaks (16 cm−1) in TOS/graphene relative to the original position in pristine graphene. These results indicate a hole density of ~ 2 × 1013 cm−2 and a Fermi level shift of approximately –500 meV37. This degenerate p-type doping satisfies the Pauli blocking condition (2|EF |~1.0 eV > 0.8 eV for 1550 nm excitation), effectively suppressing interband absorption and enabling the observed low insertion loss. Furthermore, the sheet resistance values for pristine graphene and TOS/graphene HS, as shown in Fig. 2d, reveal a pronounced shift of the charge neutral point (CNP) from approximately −2.7 V to beyond the measurable voltage range presented. This electrical measurement further confirms that the graphene is heavily p-doped through charge transfer from the adjacent TOS layer.

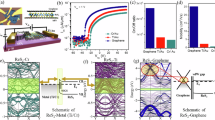

We then investigated the potential of the TOS/graphene HS as a transparent electrode for achieving lossless electro-optic phase modulation. As compared to other TMDs like WSe2, monolayer WS2 was specifically selected as the active electro-optic material owing to its large bandgap (~2 eV) and efficient tunability of carrier density via external electric fields30. The device architecture, as illustrated in Fig. 3a, comprises a capacitor structure with monolayer WS2 at the bottom, a 20 nm-thick hBN dielectric spacer, and the TOS/graphene HS serving as the transparent top electrode. The entire device is fabricated on top of a SiN microring, with a 100 nm-thick SiO2 cladding layer separating the microring from the HS. This cladding serves to improve the quality of the microring and mitigate strain effects potentially induced by the waveguide (See Materials and methods). Figure 3b outlines the electrical bias configuration, highlighting separate electrode contacts made to the bottom WS2 layer and the top TOS/graphene electrode. By applying external bias, we tune the carrier density in WS2, thereby inducing changes in its refractive index and subsequently altering the resonance conditions of the microring resonator. Notably, variations in optical absorption of materials on top of the microring resonator can shift the microring resonance from critical coupling toward either under-coupled or over-coupled conditions, resulting in reduced resonance efficiency and modified transmission characteristics (Fig. 3b top).

Phase modulation for device with ITO, graphene, and TOS/graphene electrodes. a Schematic of the fabricated device structure, consisting of a capacitor stack (monolayer WS2/hBN/graphene/TOS) integrated onto a SiN microring resonator. Right top: Side-view schematic of the device, highlighting electrical contacts with the bottom WS2 layer and top graphene electrode, connected independently to gold electrodes for voltage biasing. Right bottom: Optical image of the actual device. b Top: schematic illustrating the on-resonance and off-resonance conditions within the microring-waveguide system. Bottom: Configuration for applying external electrical bias separately to the bottom WS2 and top TOS/graphene electrodes. c–e Top panels: Resonance spectra of microring resonators integrated with c ITO/hBN/WS2, d Gr/hBN/WS2, and e TOS/Gr/hBN/WS2 heterostructures, under varying applied bias voltages. Color intensity represents the amplitude of the transmission peaks, with spectral shifts indicating changes in the optical phase. Bottom panels: Corresponding line plots of the transmission spectra extracted from the top panels, highlighting the resonance wavelength shifts and changes in modulation behavior for each electrode configuration

We systematically compared the electro-optic modulation performance of three different top electrode materials: ITO, graphene, and the TOS/graphene HS. In these three cases, the underlying electro-optic active layer and dielectric insulator were consistently monolayer WS2 and hBN, respectively. Figure 3c–e present the experimentally measured transmission spectra of the microring resonators as a function of applied bias voltage for each electrode configuration. The modulation behaviors vary distinctly among these electrode materials (Supplementary Information VII). The ITO electrode exhibits noticeable transmission amplitude variations accompanying its phase modulation, primarily due to inherent optical absorption losses. For graphene electrodes, a substantial phase shift of up to 30 pm is observed. However, this graphene phase modulation causes significant transmission amplitude changes. These changes result from bias-induced tuning of graphene’s Fermi level and corresponding variations in optical absorption. The TOS/graphene electrode achieves not only comparable but enhanced phase modulation performance while simultaneously eliminating detectable amplitude changes. This combination of benefits was previously unattainable using conventional electrode materials38.

The extinction ratio, defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum transmission levels, is extracted from the transmission spectra presented in Fig. 3c, d. A comparison across the three devices shows distinct trends. The TOS/graphene electrode exhibits minimal variation in the extinction ratio of 0.08 dB over the entire bias range, indicating negligible bias-induced optical loss. In contrast, the extinction ratio for the graphene-based device decreases significantly with increasing bias (extinction ratio variation = 7.4 dB). reflecting substantial absorption losses. The ITO-based device displays a moderate change in the extinction ratio (2.1 dB), suggesting a bias-dependent but less pronounced optical loss. These observations confirm that TOS/graphene electrodes maintain excellent optical transparency under electro-optical modulation, while conventional graphene and ITO electrodes introduce increased insertion losses due to carrier-induced absorption effects.

We then extract the changes in the real and imaginary components of the effective refractive index of the 2D material-SiN waveguide composite system, denoted as Δneff and Δkeff, respectively, which correspond to carrier-induced refractive index modulation and absorption loss. As shown in Fig. 4b, Δneff linearly decreases with applied voltage for all three electrode configurations: ITO, graphene, and TOS/graphene, indicating that the carrier density in the active region is modulated in a linear fashion by the external bias. Notably, the graphene and TOS/graphene devices exhibit a larger Δneff variation over the same voltage range compared to the ITO device. This is attributed to improved interfacial contact and more efficient charge injection at the electrode/WS2 interface.

Electrostatically induced changes in the complex refractive index of monolayer WS2 at NIR wavelengths. a Extinction ratio as a function of applied bias voltage for microring resonators integrated with different top electrodes: TOS/graphene, graphene, and ITO. The extinction ratio is defined as the difference between the maximum transmission and minimum transmission in the spectra, serving as a measure of insertion loss under varying bias conditions. b Changes in the real (Δneff) and imaginary (Δkeff) components of the effective refractive index of the propagating mode measured in devices employing three different top electrodes: graphene, ITO, and TOS/graphene, as a function of applied voltage. c Changes in the intrinsic real (Δn) and imaginary (Δk) parts of the refractive index of monolayer WS2 as functions of the electrostatically induced carrier density, obtained by converting Δneff and Δkeff data from b. d The ratio of electro-refractive response to electro-absorptive response of monolayer WS2 plotted as a function of carrier density (Supplementary Information I), demonstrating the favorable high refractive index modulation relative to absorption changes

In contrast, the trends observed in Δkeff differ significantly. The Δkeff for the graphene device increases steadily with bias voltage, indicating enhanced optical absorption due to the interaction between the evanescent field of the guided mode and the absorbing graphene layer. Conversely, the ITO and TOS/graphene devices show negligible changes in Δkeff under applied bias, suggesting minimal additional optical absorption. This clear contrast confirms that the graphene electrode directly contributes to insertion loss, whereas the TOS/graphene hybrid electrode remains optically transparent under operation. In the hybrid electrode, the observed phase modulation originates exclusively from the modulated carrier density in the underlying WS2.

The half-wave voltage–length product (Vπ·L) was calculated to be 0.629 V·cm, 0.220 V·cm, and 0.202 V·cm for devices with ITO, graphene, and TOS/graphene electrodes, respectively (Supplementary Information VI). These results clearly demonstrate that graphene-based electrodes offer superior capability for modulating the carrier density in WS2 compared to conventional ITO electrodes. Furthermore, the modulation efficiency achieved with the TOS/graphene configuration represents an extraordinary advancement that substantially surpasses previously reported values (Fig. 5), establishing a new benchmark for 2D-material-based phase modulators30,39,40.

The device with TOS/graphene electrodes in our work exhibits the lowest extinction ratio variation, down to 0.08 dB, surpassing ITO and pristine graphene22,23 and ionic liquids30,39. This indicates minimal electro-absorptive. Monolayer WS2 also shows superior modulation efficiency (Vπ·L = 0.202 V·cm) compared to silicon27, MoS2 (Supplementary Information V) and WSe240, enabling more compact device designs

We further extracted the intrinsic complex refractive index changes—Δn and Δk—of the monolayer WS2 as a function of electrostatically induced carrier density for the device with TOS/graphene electrodes (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Information IV). Specifically, Δn reaches a maximum modulation of −3.4 RIU at a carrier concentration of 4 × 1012 cm−2, while Δk remains negligible across the entire voltage range. This confirms that monolayer WS2 exhibits a strong electro-refractive response coupled with minimal electro-absorptive loss at near-infrared wavelengths. The ratio of electro-refractive to electro-absorptive change, |Δn|/|Δk|, is plotted in Fig. 4d, showing a value of 389, which is significantly higher than previously reported values30,40. It is worth noting that this figure of merit could be further enhanced by employing high-κ dielectric layers such as HfO2 or Al2O341,42, which would improve the gate coupling and overall modulation efficiency.

Lastly, we benchmarked the performance of our device against previously reported electro-optic modulators, as summarized in Fig. 5. One key metric is the variation in the extinction ratio—whose values were presented earlier—which reflects electro-absorption losses introduced by the electro-optic active material and electrode layers. Compared to devices using ITO, graphene22,23, or ionic liquid gating30,39, our TOS/graphene-integrated modulator exhibits the smallest variation in extinction ratio under bias. This indicates minimal optical absorption and highlights its superior optical transparency. The other critical metric (Vπ·L) with monolayer WS2, demonstrates that it outperforms conventional silicon27 and other TMDs such as MoS239 and WSe240 when used as the active electro-optic material. The combination of the strong electro-refractive response and negligible absorption at telecommunication wavelengths of WS2 contributes to superior modulation efficiency and thus enhanced compactness. Together, these advantages establish our platform as a promising candidate for large-scale integration of 2D materials into silicon photonic systems, enabling scalable, low-loss, and high-performance electro-optic modulation for next-generation technologies.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a transformative approach using TOS to achieve heavy p-doping of graphene, significantly altering its optical characteristics to achieve near-complete transparency at telecommunication wavelengths. This approach resolves the critical absorption loss problem that has hindered graphene photonic devices for over a decade. Leveraging this TOS/graphene as a transparent top electrode, we developed a compact, near-lossless electro-optic phase modulator that incorporates monolayer WS2 as the active modulation layer. The device achieves efficient phase modulation of 0.202 V·cm and exhibits minimal extinction ratio variation of 0.08 dB. These unprecedented results establish not just a promising pathway, but a viable and immediately applicable solution for the seamless integration of 2D materials into silicon photonic platforms in a scalable manner (Supplementary Information VIII). Our demonstration of near-lossless phase modulation enables transformative applications in energy-efficient optical communications, high-speed photonic computing, and robust quantum networks.

Materials and methods

SiN waveguide fabrication

A SiN layer of 350 nm was deposited on a SiO2 substrate by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition. The SiN waveguide and ring resonator were patterned on AR-P 6200 e-beam resist by electron beam lithography (Raith EPBG 100KV). After developing the resist, the inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE) was used to etch the waveguide and resonator, using CHF4 as etching gas and additional Ar to lower the etch rate and maintain the chamber pressure. A plasma asher was used to strip of the remaining resist. The passive sample with SiN waveguide arrays was then cladded with the 1 µm PECVD SiO2 and followed by chemical mechanical polishing (CMP). After the CMP process, a 50 nm to 100 nm SiO2 cladding with a top surface roughness of <1 nm remained to minimize potentially induced strain effect (Supplementary Information IX). Next, the device was again patterned with positive resist (AZ52143E) and patterned using a direct laser writer (DMO ML 3 Pro) to define the metal electrodes. Ti/Au (10 nm/ 40 nm) was then deposited, followed by liftoff in acetone. Finally, to remove any remaining residue and increase adhesion to our 2D HS, the sample was cleaned using oxygen plasma (FEMTO SCIENCE).

Transmission spectra measurement

The tunable laser (Santec TSL-510) was used to excite the light in the SiN waveguide (1510–1600 nm). Polarization was controlled using fiber polarization controllers (Thorlabs FPC526) and followed by a tapered waveguide. The light through the tapered waveguide was edge-coupled to the DUT chip waveguide. The 5-axis alignment stage was used to align the input and output ports of the waveguide. The throughput (output) of the waveguide was collected by the tapered waveguide and measured using a Photodetector (High-Dynamic-Range Logarithmic Power Sensors 2103). A source meter (Keithley 2450B) was used for applying the voltage to modulate the transmission using DC probes connected to the electrode of the phase modulator.

The device fabrication and characterization

TMDs, graphene, and hBN flakes were mechanically exfoliated onto SiO2/Si substrates. The thickness of individual flakes was carefully verified via optical contrast using an optical microscope. The HS stack comprising these exfoliated flakes was fabricated using a dry-transfer technique facilitated by a polycarbonate (PC) stamp. Specifically, flakes were first picked up at 120 °C using the PC polymer and subsequently transferred onto the target substrate at 200 °C. After transfer, the residual PC polymer was completely removed by immersing the samples in chloroform for 12 h. For controlled oxidation of as-exfoliated WSe2 flakes, UV-ozone treatment was performed at 50 °C for 30 min in the UV ozone cleaner (Samco UV-1), maintaining an oxygen flow rate of 1 L/min, ensuring effective conversion of WSe2 into TOS.

PL and Raman spectra were acquired at room temperature using a commercial Raman spectroscopy system (Nanobase XperRam-S567). A 532 nm continuous-wave laser was employed as the excitation source, focused onto the sample through a 100× objective lens. The resulting signals were collected by the same objective lens and analyzed using the built-in spectrometer. The laser power was carefully controlled to avoid sample damage or heating effects during measurements. Spatially resolved PL mapping was performed to characterize the optical quality and homogeneity of the samples before and after oxidation.

The sheet resistance of pristine graphene and TOS-doped graphene samples was characterized using a source-measure unit (SMU, Keithley 2634B). Electrical contacts were fabricated onto the samples using standard lithographic and metal deposition techniques, enabling precise voltage biasing and current measurement. The sheet resistance and corresponding charge neutral point shifts were determined by systematically sweeping the applied gate voltage while measuring the current-voltage characteristics, confirming the doping level and electrical quality of the graphene-based electrodes.

FDTD simulation

A microring resonator and its adjacent bus waveguide were modeled in Lumerical FDTD by defining precise geometries and assigning accurate material refractive indices, with the simulation domain bounded by perfectly matched layers (PML) to suppress reflections. A broadband optical source was injected into the bus waveguide to excite resonant modes, while strategically placed field monitors recorded the electromagnetic field distributions. A refined mesh was applied, particularly near the resonator, to capture intricate field variations, and the resulting time-domain data was converted to the frequency domain via Fourier transform to extract the transmission spectrum and key resonator parameters such as resonant wavelengths, Q-factor, and free spectral range (FSR).

Data availability

The materials, datasets, and code supporting the findings of this study remain unavailable for public access at present but can be obtained by contacting the authors with a suitable request.

References

Thomson, D. et al. Roadmap on silicon photonics. J. Opt. 18, 073003 (2016).

Atabaki, A. H. et al. Integrating photonics with silicon nanoelectronics for the next generation of systems on a chip. Nature 556, 349–354 (2018).

Reed, G. T. et al. Silicon optical modulators. Nat. Photonics 4, 518–526 (2010).

Liu, A. S. et al. A high-speed silicon optical modulator based on a metal-oxide-semiconductor capacitor. Nature 427, 615–618 (2004).

Kuo, Y. H. et al. Strong quantum-confined Stark effect in germanium quantum-well structures on silicon. Nature 437, 1334–1336 (2005).

Chaisakul, P. et al. Integrated germanium optical interconnects on silicon substrates. Nat. Photonics 8, 482–488 (2014).

Elbanna, A. et al. 2D material infrared photonics and plasmonics. ACS Nano 17, 4134–4179 (2023).

Sun, Z. P., Martinez, A. & Wang, F. Optical modulators with 2D layered materials. Nat. Photonics 10, 227–238 (2016).

Bogdanov, S. et al. Material platforms for integrated quantum photonics. Opt. Mater. Express 7, 111–132 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Van der Waals heterostructures and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16042 (2016).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Two-dimensional semiconductor optoelectronics based on van der Waals heterostructures. Nanomaterials 6, 193 (2016).

Wang, Q. H. et al. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Xia, F. N. et al. Two-dimensional material nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 899–907 (2014).

Yu, Y. L. et al. Giant gating tunability of optical refractive index in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Nano Lett. 17, 3613–3618 (2017).

Mak, K. F. et al. Tightly bound trions in monolayer MoS2. Nat. Mater. 12, 207–211 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Advancement in carbon nanotubes optoelectronic devices for terahertz and infrared applications. Adv. Electron. Mater. 10, 2400124 (2024).

Hu, L. B., Wu, H. & Cui, Y. Metal nanogrids, nanowires, and nanofibers for transparent electrodes. MRS Bull. 36, 760–765 (2011).

Maniyara, R. A. et al. Highly transparent and conductive ITO substrates for near infrared applications. APL Mater. 9, 021121 (2021).

Ma, Z. Z. et al. Indium-tin-oxide for high-performance electro-optic modulation. Nanophotonics 4, 198–213 (2015).

Mak, K. F. et al. Optical spectroscopy of graphene: from the far infrared to the ultraviolet. Solid State Commun. 152, 1341–1349 (2012).

Li, W. et al. Ultrafast all-optical graphene modulator. Nano Lett. 14, 955–959 (2014).

Mohsin, M. et al. Experimental verification of electro-refractive phase modulation in graphene. Sci. Rep. 5, 10967 (2015).

Phare, C. T. et al. Graphene electro-optic modulator with 30 GHz bandwidth. Nat. Photonics 9, 511–514 (2015).

Forouzmand, A. & Mosallaei, H. Electro-optical amplitude and phase modulators based on tunable guided-mode resonance effect. ACS Photonics 6, 2860–2869 (2019).

Gao, Y. D. et al. High-speed electro-optic modulator integrated with graphene-boron nitride heterostructure and photonic crystal nanocavity. Nano Lett. 15, 2001–2005 (2015).

Yao, B. C. et al. Gate-tunable frequency combs in graphene-nitride microresonators. Nature 558, 410–414 (2018).

Sorianello, V. et al. Graphene–silicon phase modulators with gigahertz bandwidth. Nat. Photonics 12, 40–44 (2018).

Lee, E. J. et al. Active control of all-fibre graphene devices with electrical gating. Nat. Commun. 6, 6851 (2015).

Yuan, H. T. et al. Liquid-gated ambipolar transport in ultrathin films of a topological insulator Bi2Te3. Nano Lett. 11, 2601–2605 (2011).

Datta, I. et al. Low-loss composite photonic platform based on 2D semiconductor monolayers. Nat. Photonics 14, 256–262 (2020).

Choi, M. S. et al. High carrier mobility in graphene doped using a monolayer of tungsten oxyselenide. Nat. Electron. 4, 731–739 (2021).

Kim, B. S. Y. et al. Ambipolar charge-transfer graphene plasmonic cavities. Nat. Mater. 22, 838–843 (2023).

Kim, B. S. Y. et al. Advances and applications of oxidized van der Waals transition metal dichalcogenides. Adv. Sci. 11, 2407175 (2024).

Bose, D. et al. Anneal-free ultra-low loss silicon nitride integrated photonics. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 156 (2024).

Puckett, M. W. et al. 422 million intrinsic quality factor planar integrated all-waveguide resonator with sub-MHz linewidth. Nat. Commun. 12, 934 (2021).

Mews, M., Korte, L. & Rech, B. Oxygen vacancies in tungsten oxide and their influence on tungsten oxide/silicon heterojunction solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 158, 77–83 (2016).

Das, A. et al. Monitoring dopants by Raman scattering in an electrochemically top-gated graphene transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 210–215 (2008).

Zhao, Z. X. et al. MoS2 hybrid integrated micro-ring resonator phase shifter based on a silicon nitride platform. Opt. Lett. 47, 949–952 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Heterogeneous integrated phase modulator based on two-dimensional layered materials. Photonics Res. 10, 1401 (2022).

Datta, I. et al. 2D material platform for overcoming the amplitude–phase tradeoff in ring resonators. Optica 11, 48 (2024).

Wang, B. H. et al. High-k gate dielectrics for emerging flexible and stretchable electronics. Chem. Rev. 118, 5690–5754 (2018).

Yim, K. et al. Novel high-κ dielectrics for next-generation electronic devices screened by automated ab initio calculations. NPG Asia Mater. 7, e190 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) Academic Research Fund (AcRF) Tier 1 grants (RG64/22, RT2/23, RG63/23) and Tier 2 (MOE-T2EP50224-0018). This work is also supported by the A*STAR, Singapore, Advanced Manufacturing and Engineering (AME) Individual Research Grant (IRG) under the Project M23M6c0109. S.H.C. acknowledges funding from the MOE AcRF Tier 3 grant (MOE-MOET32023-0003) “Quantum Geometric Advantage”. D.R. acknowledges support by NSF Wisconsin Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (DMR-2309000). M.S.C. acknowledges support by the Basic Science Research Program (RS-2021-NR060128, RS-2022-NR072277), funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF). K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 21H05233 and 23H02052), the CREST (JPMJCR24A5), JST, and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan. The authors acknowledge the support of the Nanyang NanoFabrication Centre (N2FC). Q.W. and L.K.A. acknowledge the support of ASTAR IRG (M23M6c0102). Additionally, the authors thank the use of the Nanobase XperRAM-S Raman spectroscopy system for Raman measurements conducted during this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. R.Y., and Y.Y. fabricated the 2D heterostructures and performed the Raman and PL measurements. L.S., A.S.B.J., and J.L. conducted transmission spectral measurements, performed electro-optic modulation experiments, and analyzed the data. C.L. and H.S. provided MOCVD-grown TMD film. D.R. and Y.H. provided the WSe2 crystal. T.T., and K.W. provided high quality hBN crystal. S.L. did the sheet resistance measurement. Q.W. and L. K. A. did the DFT simulation. X.G. and S.-G.L. did the simulation. M.S.C., W.C., T.B.K., L.R., and J.H. discussed the experimental results. S.G. wrote the manuscript with the help of X.G. and S.-G.L., J.X.B.S., and S.H.C. supervised the whole project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, S., Lee, SG., Gong, X. et al. Hybrid tungsten oxyselenide/graphene electrodes for near-lossless 2D semiconductor phase modulators. Light Sci Appl 15, 42 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02058-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02058-8