Abstract

The development of advanced magnetoelectric (ME) composites necessitates high-performance materials that are capable of achieving high levels of ME coupling, minimal magnetic loss, and absence or limited reliance on external excitation sources. In this paper, a (2-2) connectivity ME laminate integrates multiple layers of FeSiB alloy (Metglas) and Pb (Mg, Nb) O3-PbTiO3 (PMN-PT) single crystal, achieving a remarkable ME coupling coefficient of 2033.4 V/Oe·cm (sevenfold rise) by laser thermal annealing treatment. Here, the laser-induced nanostructures on Metglas, with an oxidized insulation layer and soft and hard magnetic dipole layer improve the Magneto-electric-mechanical coupling with a mechanical quality factor (Qm) exceeding 350. More importantly, the interaction between amorphous and nanocrystalline dipoles triggers an Exchange Bias (EB) effect, leading to a self-biasing performance of 67.45 V/Oe·cm. Furthermore, the composite exhibits an excellent passive DC magnetic detection limit of 22 nT, and an improved weak AC magnetic detection limit down to 383 fT. These explorations offer the potential to enhance passive current measurement, and underwater communication, extend weak magnetic positioning and brain magnetic detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

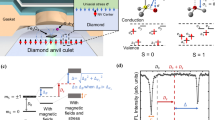

The development of low-frequency weak magnetic detection is driving higher demands for magnetic sensors, including high sensitivity, low power consumption, miniaturization, and high stability. Magnetoresistive sensors offer a wide frequency band and good linearity, but the direction of the magnetic field limits their performance1,2. Fluxgate sensors are known for their pT level sensitivity and simple structures; however, they tend to be large and power-hungry3. Superconducting quantum interference devices provide extremely high sensitivity for biomagnetic detection, but necessitate low temperatures and entail significant costs4. Optically pumped magnetometers exhibit high precision with no zero shift; nevertheless, they are relatively large and environmentally sensitive5. Magnetoelectric (ME) sensors composed of magnetostrictive and piezoelectric materials, offer low power consumption and multifunctionality. Their detection limits are typically in the 1–10 pT range, with some devices achieving sub-pT sensitivity6,7,8. These characteristics make them highly promising for applications in detecting weak magnetic fields at low frequencies9,10. However, the magnetic detection limit remains below the theoretical value (~fT)11,12.

The optimization of ME coupling research has so far focused on material properties13, geometric enhancements14, and coupling methods15. In 2011, Gao et al. successfully developed the Metglas/PMN-PT laminated push-pull ME composites with 1100 V/Oe·cm and a DC detection limit of 1 nT16. In 2022, Xu et al. developed the Metglas/PZT-based compass with a magnetoelectric response of 274 V/Oe·cm and an angle sensitivity within ±0.02° through optimizing geometric dimensions17.

Meanwhile, diverse annealing methods show their potential to alter the magnetic or electrical characteristics of ME materials18,19,20, by improving the mechanical mass factor8,11,21,22,23. In 2013, Li et al. achieved a magnetoelectric coupling coefficient as high as 380 V/Oe·cm in a self-based annealed Metglas/PZT/Metglas laminate with a (2-2) mode multi-push-pull structure24. In 2021, Peddigari et al. engineered a multilayer structure consisting of piezoelectric single crystal macro fiber composites and flash photon annealed (FPA) Metglas, which enhanced the amorphous nature of Metglas and achieved a detection threshold of 0.5 pT25. In 2023, Palneedi et al. employed intense pulsed light(IPL) pulses for annealing PZT piezoelectric thick films on Metglas substrates, which led to non-resonant coupling coefficients reaching 20 V/Oe·cm26. In 2024, Li et al. used laser annealing to control the transformation of sheet-like nanocrystalline FSAC32 alloy from α-Fe to DO3, thereby improving the magnetic permeability of the alloy powder. Notably, due to the differing magnetization difficulties of the various phases, they observed asymmetric hysteresis loops27. In 2017, Dong’s group reported a heightened magnetoelectric response (7000 V/Oe·cm) through the targeted laser treatments on Metglas fibers within (1-1) laminated ME composites15,28. However, these annealing treatments may lead to the fragmentation of magnetic domain structures19,29,30, thereby restricting the improvement of the mechanical mass factor. The optimal annealing treatment is needed to achieve optimal device performance.

This paper introduces the femtosecond laser annealing technique as an effective means for tuning the magnetic properties of FeSiB in a (2-2) type sandwich-structure magnetoelectric laminates, leveraging its precise control over rapid melting and cooling dynamics. The laser-induced microstructure and its magnetic properties are characterized using Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM), and Magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE). The effects of laser treatment were systematically analyzed in terms of the magnetoelectric coefficient, piezomagnetic coefficient, and mechanical quality factor.

Preparation

Femtosecond laser processing

The surface modification of Metglas foils was achieved using a femtosecond laser pulse scanning technique (model FemtoYL-4) to enhance magnetic properties and mitigate inherent surface oxidation. The parameters were set as follows: line spacing of 0.01 mm, Z-type filling, processing speed of 5000 mm/s, and spot diameter of 0.03 mm. The key factors affecting surface reactions are laser power, scanning times, and pulse line spacing. Generally, once the laser powers are greater than 20 W, it easily results in the formation of pronounced crystalline structures and leads to a significant reduction in the piezomagnetic coefficient. Therefore, a laser power of 7 W was selected to prevent excessive high-temperature crystallization and control the rate of magnetic decline. The annealing power was set to 7 W, with a frequency of 50 kHz. A filling scan was chosen to fill the gaps between laser spots. Scanning was performed 300 and 600 times, respectively, to control the growth of nanocrystalline grains and form various crystalline structures.

Magnetoelectric material fabrication

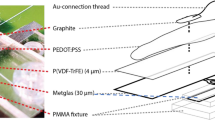

Firstly, 8 layers of Laser-treated Metglas foils, with 100 mm in length and 2.5 mm in width, were laminated using epoxy in a bespoke 3D mold for curing. Secondly, a PMN-PT single crystal (10 mm (L) × 2 mm (W) × 0.2 mm (T)) was pre-polarized in silicone oil at 60 °C. Here, flexible electrodes were positioned at the geometric centers of both piezoelectric and magnetostrictive layers to measure the voltage output induced by magnetoelastic strain. To optimize the amount of epoxy resin and enhance interface bonding, a specially designed T-shaped fixed 3D shell was utilized. This facilitated multi-layer curing under a high pressure of 20 kN for twenty-four hours. This curing process is critical to ensure the maximal removal of excess flow colloids from each layer while maintaining the flexibility of the multi-layer plate structure, and the effective transfer of magnetostrictive strain. The Metglas foils, in conjunction with a PMN-PT single crystal, were utilized as the magnetostrictive and piezoelectric materials laminated in a (2-2) connectivity pattern. This configuration operated in the longitudinal-transverse (L-T) mode, as depicted in Fig. 1a. The magnetoelectric coupling coefficient of ME Laminates, as shown in Fig. 1b, characterized by enhanced interface bonding, exhibits an approximately 1.5-fold increase. Compared to conventional connection processes, the 3D uniform reinforcement process prevents delamination under prolonged operational conditions, thereby extending the service life of the samples.

Magnetic material performance and ME coupling testing

The surface morphologies of Metglas samples were observed by using the high-precision Gemini SEM500 model of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). X-ray diffraction (XRD) was utilized to detect the presence of crystalline structures. The Thermo Fisher Talos-F200X Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) model was utilized to examine the internal structure and material composition. Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) and Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect (MOKE) were employed to assess variations in hysteresis loops and surface magnetic anisotropy. The applied excitation DC magnetic fields were from 0 to 50 Oe. The Lorentz field emission transmission electron microscope (FE-TEM, Fresnel mode LTEM) was also utilized for observing domain flipping and domain wall movement. The magnetic field gradually changes from a zero state to full magnetization, corresponding to a range of ±3% of the objective lens’s magnetic field capacity.

The magnetoelectric performance testing platform was put up and shown in Fig. 1b. The test was performed at room temperature at a frequency of 0 to 25 kHz, with a DC excitation providing a −40 to 40 Oe magnetic field. Additionally, a LabVIEW-based testing system controlled the signal generator and lock-in amplifier for various tests, including magnetoelectric coupling coefficient measurement, optimal DC bias field testing, and AC/DC detection limit testing.

Results and discussion

Nanostructure analysis

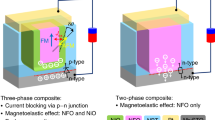

The nanostructure is a crucial factor in determining the performance and functionality of materials. Here, one with laser-treated Metglas foils and the other with untreated counterparts were utilized to observe the surface morphology differences. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, it reveals irregular point-like regions in the surface of the laser-annealed Metglas by SEM, culminating in the formation of stacked stripes in Fig. 2b. In marked contrast, the untreated Metglas surface (Fig. 2c), exhibits a remarkably smooth texture. More importantly, Fig. 2d displays a new nanostructure in treated Metglas, which is bifurcated into two layers, the 40 nm thick of upper Layer 1 and the 61 nm thick of lower Layer 2. Here, Layer 3 is composed of less altered Metglas. Moreover, Fig. 2e demonstrates the heterogeneous nucleation of a nanocrystalline phase within Layer 2, approximately 5 nm in scale, resulting in short-range ordered clusters. The results indicate that nanocrystals are growing during the laser scanning process. The diffraction pattern (Fig. 2f) reveals that the predominant nanocrystalline phase is Fe3O4 corresponding to the (222) and (022) planes of Fe3O4, which contrasts with the formation of α-Fe (Si) nanocrystals observed in high-power laser annealing19,31,32. As shown in Fig. 2g, Layer 1 predominantly features silicon oxide, carbide, and a notable absence of iron, while there is a noticeable decrease in silicon content and an increase in iron content in Layer 2. Notably, in addition to a small amount of uniformly distributed amorphous iron oxide, there are regions with extremely high iron content, characterized by circular areas shown in Fig. 2l. In addition, XRD spectra show a reduced peak around 45° in the laser-treated foils than that of untreated foils in Fig. 2h, suggesting a reduction of ordered clusters within the surface microstructure33,34.

a Surface topography of laser-treated Metglas. b Carbonized fringe observed on the laser-treated Metglas. c Surface topography of Metglas. d Stratified distribution of tripartite layer sections of laser-treated Metglas. e An ordered crystalline structure within the second layer. f Fourier transform of HRTEM image of Fe3O4 crystal. g Cross-sectional eds line scanning analysis. h XRD analytical comparison. i Silicon elemental distribution analysis. j Oxygen elemental distribution analysis. k Carbon elemental distribution analysis. l Iron elemental distribution analysis

Figure 3 shows the surface chemical reconstruction process with a three-layer nano-magnetic structure, consisting of an oxidation isolation layer, a magnetic dipole field layer, and a soft magnetic layer33. Due to the instantaneous temperature effects, silicon (Si) or boron (B) in FeSiB cannot directly form α-FeSi or α-FeB with iron (Fe)35. The bombardment causes boron to be expelled to the surface, while silicon escapes to the surface and reacts with air to form a silicon-rich oxide film36. It provides the Metglas foil with an effective oxidation isolation layer, enhancing its corrosion resistance37. In Layer 2, oxygen thoroughly integrates with iron to form new amorphous iron oxides, carbon oxides, and silicon oxides at the overlap scanning spot. Simultaneously, a small amount of iron forms Fe3O4 crystalline structures embedded within the new amorphous material. This results in long-range magnetic dipole field interactions.

Magnetic analysis

Magnetic properties are closely related to the nanostructures of magnetic materials, Fig. 4 shows the changes in magnetic properties of laser-treated and untreated Metglas samples, respectively. The magnetic permeability exhibits minimal variation as the layer number increases in Fig. 4a, whereas the saturation magnetization demonstrates a progressive increase. Untreated Metglas exhibits a coercivity of roughly 0.02 Oe and a strong soft magnetism. After the laser-treated process (600 scans), it shows a significant decrease in saturation magnetization, due to the amorphous-to-ordered structural transition. The irregularity of the oxide layer and the magnetic dipole layer serving as the pins of magnetic domain walls can induce impurity fields on the tape surface and reduce the initial magnetic permeability. Thus, the new nanostructure results in a noticeable shift and the emergence of self-bias in the initially symmetrical hysteresis loops. Additionally, the coercivity increases to 0.25 Oe after 600 scans, which is 12 times greater than that before annealing in Fig. 4b. Thus, 600 scan cycles, which provide stronger self-bias feedback, are selected as the processing parameter for a single layer of Metglas foil.

a Hysteresis loop of Metglas under a high magnetic field. b Hysteresis loop under a low magnetic field. c Untreated Metglas: Kerr effect-induced magnetic domain flipping process. d Treated Metglas: Backside magnetic domain flipping via Kerr effect. e Untreated Metglas Lorentz lens: Initial magnetic wall state under zero field. f Untreated Metglas Lorentz lens: pre-saturation magnetic wall motion. g Treated-Metglas Lorentz lens: Initial magnetic wall state under zero field. h Treated-Metglas Lorentz lens: pre-saturation magnetic wall motion

Meanwhile, the domain realignment process during magnetization for both untreated and treated samples is depicted by MOKE. For the untreated samples, irregularly shaped magnetic reversal regions are observed as the magnetic field increases, as shown in Fig. 4c. The magnetic domains show a complete and rapid reversal. For the laser-treated, a periodic pattern of white and black striped domains of uniform width is shown in Fig. 4d, and a more rapid domain flipping activity is noted under the same dynamic magnetic field conditions. Nanostructure results in a significant refinement of the magnetic domain structure19. Fig. 4g shows a Bloch-type38 orientation in the vertical plane after laser treated process, while untreated Metglas exhibits magnetic domains with an iconic double-Y configuration39 (Fig. 4e). However, the parallel domain regions migrated towards nanostructure (Fig. 4h), opposing to the bidirectional divergence observed in unprocessed cross-domain walls39,40,41,42,43.

The transition from 45° magnetic domains to parallel domains indicates the enhancement of magnetic anisotropy,38,44 which changes the direction of the effective field. As the laser thermal energy dissipates into the soft magnetic layer, the effective field slowly returns to its original position, and the magnetic moment will damp oscillate towards the direction of the effective field, inducing a gradual shift in the magnetic wall45. Although the laser destroys the paramagnetic properties of the amorphous crystal, its heat energy is injected46. Due to the insulating layer, the spin majority cannot penetrate, resulting in the accumulation of spin majority in the soft magnetic layer (Layer 3), which may strengthen the magnetic moment of FeSiB in Layer 3 and decrease the overall magnetic loss47,48,49.

ME coupling enhancing

For comparative analysis, magnetoelectric (ME) and self-biased magnetoelectric (SME)50 laminates were assembled under the same flow. Under optimal DC biasing, the SME laminate demonstrated a magnetoelectric coupling coefficient of 2033.40 V/Oe·cm at 23.3 kHz in Fig. 5a, which is approximately 7.6 times higher than the ME laminate (266.76 V/Oe·cm at Hbias). Additionally, both the limit of detection (LoD)51 and power spectral density (PSD)52 for the SME laminate were quantified under optimal DC bias at the resonance frequency (Fig. 5b). The SME laminate exhibits exceptional sensitivity in the detection of ultra-weak AC signals, with measured values of 383.98 fT and 1.04 × 10−7 V/Hz1/2, respectively. Notably, the ME laminate shows a pronounced dependency on DC bias at 21.7 kHz in Fig. 5c across a −40 Oe to 40 Oe range. Remarkably, the SME laminate exhibits exceptional linearity and high DC sensitivity at 23.3 kHz. The direct magneto-electric effect (DME) exhibits a distinctive double peak phenomenon, with an initial peak observed at approximately 3.5 Oe, thereby demonstrating remarkable linear DC sensitivity within the ±3.5 Oe range. The second spike (approximately 38 Oe) achieves a peak height that is twice as high as the first one. The double-peak phenomenon was also found in FeSiB/Terfenol-D/PZT and Ni/PZT/Terfenol-D multiferroic composites53,54,55. Meanwhile, in Fig. 5f, the hysteresis behaviors of the SME laminate exhibit an offset of 0.97 V/Oe near the zero point of the DC magnetic field, whereas the ME laminate shows zero at 0 Oe. The observed modification in the hysteresis pattern of laser-treated Metglas can be attributed to the self-biased effects induced by its nanostructure. The SME laminate (Fig. 5d) exhibits a significant magnetoelectric response of 67.45 V/Oe·cm and a DC LoD of 22 nT, with noise levels around 9.42µV (refer to Fig. 5e), all achieved without a DC bias magnetic field.

a Magnetoelectric coupling coefficients: comparative analysis of self-biased and ME laminates under optimal DC bias conditions. b Sensitivity metrics: limit of detection (LoD) and power spectral density (PSD) for the self-biased laminate. c Hysteresis behavior: DC response curves for both SME and ME laminates. d Unbiased coupling efficiency: Magnetoelectric coupling in SME and ME laminates without DC bias application. e Noise Characterization: Direct current noise levels associated with the SME laminate. f Near-Zero DC Hysteresis: Comparative hysteresis curves of SME and ME laminates in proximity to DC zero

Magnetic-mechanical-electrical coupling

Magnetic-mechanical-electrical coupling model

By establishing an equivalent circuit model of magnetic-mechanical-electrical coupling56,57,58,59,60 as shown in Fig. 6a, the influences of laser processing on the magnetic-mechanical-electrical conversion efficiency of the magnetic sensor were evaluated. The expression for the total mechanical impedance is presented here56,60:

a Simplified magnetic-mechanical-electrical coupling model56,57,58,59,60. b Predicted SME laminate frequency response curves. c Predicted ME laminate frequency response curves. d Predicted DC sensitivity of SME model vs ME model. e Comparative piezomagnetic coefficients. f Equivalent quality factor analysis. g Compliance coefficient comparison. h Young’s modulus (\({{\Delta }}\)E coefficient) comparison

The magnetoelectric coupling coefficient (V/Oe) is expressed as60

Based on the equivalent circuit theory, the frequency response data of the magnetoelectric sensors under various bias magnetic fields were initially fitted in Figs. 6b, c. In the fitting results, a DC bias of 15 Oe yields the optimal magnetoelectric response at 23.0 kHz, which was in good agreement with the experimental findings from the SME laminate. Under a specific amplitude of the AC magnetic field, the perturbation of the DC magnetic field induces a change in the output voltage of the magnetoelectric sensor. Utilizing extracted material property parameters, interpolation calculations are performed to determine the DC magnetic sensitivity under different working conditions (bias magnetic field and driving frequency), defining it as56

The experimental findings reveal a DC sensitivity of 13.6 V/Oe/Oe at 23.0 kHz, achieved with a DC bias magnetic field of 3.5 Oe, which is five times higher than the sensitivity obtained without undergoing the annealing treatment. It is noteworthy that laser treatment not only enhances the AC performance of the ME laminate but also significantly amplifies its sensitivity for DC detection.

Magneto-mechanical characteristics of the ME laminates

By employing an equivalent model, magneto-mechanical characteristics, including the piezomagnetic coefficient (dm), compliance coefficient (sm), and the equivalent mechanical quality factor (Qm) were correlated with the DC bias magnetic field, refining the data through model fitting. The piezomagnetic coefficient of SME laminates decreases obviously under ±20 Oe DC bias, whereas that of ME increases with the strengthening of the excitation magnetic field. The comparative analysis in Fig. 6f reveals that the Qm value in the SME laminate increases to a range of 350–500, approximately 2.5 times higher than that of ME laminates. In addition, Fig. 6g, h demonstrates a reduced compliance factor and an increased coefficient (ΔE) for the SME laminate. The alteration in material structure results in a slight reduction in both the piezomagnetic coefficient and compliance coefficient, consequently affecting the overall magnetic properties which become more rigid. This subsequently impacts the magnetoelectric response of the device at lower frequencies. However, it is worth noting that there is a significant breakthrough enhancement in magnetoelectric response at resonant frequency and LoD of SME laminate at resonant frequency due to its exponentially increasing Qm and ΔE.

Additionally, the performance indices of (2-2) ME laminates, obtained through a comparative analysis of various Metglas annealing studies, are presented in Table 1. The utilization of low-powered laser annealing significantly enhances the magnetoelectric response by approximately sevenfold for both self-biased and non-self-biased configurations. Our sensor achieves AC detection at fT levels and DC detection at nT levels, with a quality factor reaching 380 at the peak magnetoelectric coefficient. This represents a substantial improvement compared to previous findings.

Conclusion

A novel laser-induced nano-structure of FeSiB Metglas efficiently increased the ME coupling coefficient and high sensitivity to weak magnetic detection, which influenced the equilibrium between the piezomagnetic coefficient and magneto-mechanical loss. This approach not only enhances magnetic-mechanical coupling at high frequencies but also introduces the self-biasing in Metglas, promising a pathway for advancing sensor technology in vector detection applications.

References

Zheng, C. et al. Magnetoresistive sensor development roadmap (non-recording applications). IEEE Trans. Magn. 55 (2019).

Jogschies, L. et al. Recent developments of magnetoresistive sensors for industrial applications. Sensors 15, 28665–28689 (2015).

Shen, X. Y., Teng, Y. T. & Hu, X. X. Design of a low-cost small-size fluxgate sensor. Sensors 21 (2021).

Boto, E. et al. A new generation of magnetoencephalography: room temperature measurements using optically-pumped magnetometers. Neuroimage 149, 404–414 (2017).

Aslam, N. et al. Quantum sensors for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 157–169 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. Highly sensitive magneto-mechano-electric magnetic field sensor based on torque effect. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 1409–1416 (2021).

Lu, Y. et al. High sensitivity face shear magneto-electric composite array for weak magnetic field sensing. J. Appl. Phys. 128 (2020)

Zhai, J. et al. Magnetoelectric laminate composites: an overview. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 91, 351–358 (2008).

Lasheras, A., Gutiérrez, J. & Barandiarán, J. M. Size effects in the equivalent magnetic noise of layered Fe64Co17Si7B12/PVDF/Fe64Co17Si7B12 magnetoelectric sensors. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 263, 488–492 (2017).

Li, D. et al. Low-damping resonant magnetoelectric effect in the composite of magnetostrictive alloy and quartz tuning fork. Chin. J. Sens. Actuators 32, 495–500 (2019).

Reis, S. et al. Optimized anisotropic magnetoelectric response of Fe61.6Co16.4Si10.8B11.2/PVDF/Fe61.6Co16.4Si10.8B11.2 laminates for AC/DC magnetic field sensing. Smart Mater. Struct. 25 (2016).

Dong, X. W. et al. Ultra-sensitive detection of magnetic field and its direction using bilayer PVDF/Metglas laminate. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 153, 64–68 (2009).

Li, M. H. et al. Enhanced magnetoelectric effect in self-stressed multi-push-pull mode Metglas/Pb(Zr,Ti)O3/Metglas laminates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 3 (2012).

Cheng, Y. X. et al. Recent development and status of magnetoelectric materials and devices. Phys. Lett. A 382, 3018–3025 (2018).

PourhosseiniAsl, M. et al. Enhanced self-bias magnetoelectric effect in locally heat-treated ME laminated composite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115 (2019).

Gao, J. Q. et al. Enhanced sensitivity to direct current magnetic field changes in Metglas/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3 laminates. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 3 (2011).

Xu, Y. W. et al. An AC magnetic compass based on magnetoelectric effect integrated with a calibration algorithm. Sens. Actuators a-Phys. 347, 9 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Air surface crystallization with quenched-in Fe crystallites and associated magnetomechanical properties in Fe-Si-B amorphous ribbons. AIP Adv. 13 (2023).

Kusinski, J. et al. Local crystallization in amorphous Fe80Si11B9 ribbon by pulsed laser interference heating. Mater. Charact. 193, 10 (2022).

Palneedi, H. et al. Enhanced self-biased magnetoelectric coupling in laser-annealed Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 Thick Film Deposited on Ni Foil. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 11018–11025 (2018).

Vopsaroiu, M. et al. Multiferroic composite for combined detection of static and alternating magnetic fields. Mater. Lett. 66, 282–284 (2012).

Ma, J., Hu, J., Li, Z. & Nan, C. W. Recent progress in multiferroic magnetoelectric composites: from bulk to thin films. Adv. Mater. 23, 1062–1087 (2011).

Zhang, H. et al. Evaluation of Metglas/polyvinylidene fluoride magnetoelectric bilayer composites for flexible in-plane resonant magnetic sensors. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54 (2020).

Li, M. et al. Giant magnetoelectric effect in self-biased laminates under zero magnetic field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102 (2013).

Peddigari, M. et al. Ultra-magnetic field sensitive magnetoelectric composite with sub-pT detection limit at low frequency enabled by flash photon annealing. Nano Energy 90 (2021).

Palneedi, H. et al. Intense pulsed light thermal treatment of Pb(Zr,Ti)O3/metglas heterostructured films resulting in extreme magnetoelectric coupling of over 20 V cm−1 Oe−1. Adv. Mater. 35 (2023).

Li, Q.F. et al. Improving interfacial magnetoelastic effect and complex permeability of FeSiAl alloy powders for broadband decimeter-wave absorption via Cr doping. J. Alloys Compounds 1002 (2024).

Chu, Z. et al. Enhanced resonance magnetoelectric coupling in (1‐1) connectivity composites. Adv. Mater. 29 (2017).

Katakam, S. et al. Laser-induced thermal and spatial nanocrystallization of amorphous Fe–Si–B alloy,. Scr. Materialia 66, 538–541 (2012).

Zhou, L. et al. Exchange bias behaviour of amorphous CoFeNiSiB ribbons. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 42 (2009).

Czyż, O. et al. Study of structure and properties of Fe-based amorphous ribbons after pulsed laser interference heating. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 29, 6277–6285 (2020).

Zhuang, X. et al. Tailoring the magnetomechanical power efficiency of metallic glasses for magneto-electric devices. J. Appl. Phys. 132 (2022).

Liang, S.-X. et al. A laser-based synthesis route for magnetic metallic glass nanoparticles. Scr. Mater. 203 (2021).

Chen, Q. et al. Highly efficient catalytic performance and self-renewing behavior of Fe-based glass induced by pulsed laser. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 188, 191–201 (2024).

He, A. et al. Magnetic softness, dynamic magnetization, and relaxation behavior of FeSiBC amorphous alloys. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 31, 4261–4270 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Air surface crystallization with quenched-in Fe crystallites and associated magnetomechanical properties in Fe–Si–B amorphous ribbons. AIP Adv. 13 (2023).

Lin, J. et al. Effects of heat treatment in air on soft magnetic properties of FeCoSiBPC amorphous core. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 597 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Optimizing soft magnetic properties by reducing internal defects and residual stress of Fe85-xSi9.6Al5.4Snx soft magnetic composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18, 3872–3883 (2022).

Hiraoka, M. et al. Observation of magnetic domain structure in Fe81B15Si4 amorphous alloy by Lorentz microscopy and electron holography. Mater. Trans. 50, 2839–2843 (2009).

Lee, H. et al. Nano-crystallization behavior and magnetic domain evolution in commercial Fe–Si–B metallic glass. J. Alloys Compounds 857 (2021).

Sypien, A., Kusinski, J., Kusinski, G. J. & Nelson, E. C. TEM studies of the FeSiB amorphous alloy nanocrystallized by means of Nd:YAG-pulsed laser heating. Mater. Chem. Phys. 81, 390–392 (2003).

Životský, O. et al. Surface microstructure and magnetic behavior in FeSiB amorphous ribbons from magneto-optical Kerr effect. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 324, 569–577 (2012).

Suzuki, T. et al. Direct observation of reverse magnetic domain and magnetic domain wall motion in Nd-Fe-B magnet at high temperature by Lorentz microscope. MRS Adv. 1, 241–246 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Ductile Fe-based amorphous alloy with excellent soft magnetic properties induced by low-temperature stress annealing. Intermetallics 166, 7 (2024).

Hou, L. et al. Tailoring magnetic softness of Fe-based amorphous alloys with superior magnetization by magnetic field annealing. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 200, 27–37 (2024).

Sun, R. et al. Large tunable spin-to-charge conversion induced by hybrid Rashba and Dirac surface states in topological insulator heterostructures (vol 19, pg 4420, 2019). Nano Lett. 19, 6709–6709 (2019).

Battiato, M., Carva, K. & Oppeneer, P. M. Theory of laser-induced ultrafast superdiffusive spin transport in layered heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 86, 16 (2012).

Melnikov, A. et al. Ultrafast transport of laser-excited spin-polarized carriers in Au/Fe/MgO(001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 5 (2011).

He, W. et al. Ultrafast demagnetization enhancement in CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB magnetic tunneling junction driven by spin tunneling current. Sci. Rep. 3, 5 (2013).

Zhou, Y. et al. Self-biased magnetoelectric composites: an overview and future perspectives. Energy Harvesting Syst. 3, 1–42 (2016).

Yarar, E. et al. Inverse bilayer magnetoelectric thin film sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109 (2016).

C. Fermon, M. Pannetier-Lecoeur, Noise in GMR and TMR sensors, Giant Magnetoresistance (GMR) Sensors Vol. 6, pp 47-70 (Springer, 2013).

Chu, Z. et al. Jumping and hysteresis effect in 1–1-typed magnetoelectric resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119 (2021).

Niu, L., Shi, Y. & Gao,Y. Effect of magnetic-field orientation on dual-peak phenomenon of magnetoelectric coupling in Ni/PZT/Terfenol-D composites. AIP Adv. 9 (2019).

Chen, L. & Dai, X. Z. Magnetic sensors based on magnetoelectric laminate multiferroic heterostructures with dual-peak phenomenon. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 12, 2842–2845 (2015).

Du, Y. J. et al. Performance analysis of acoustically actuated magnetoelectric antennas via equivalent circuit method. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 13 (2024).

Du, Y. J. et al. Very-low-frequency magnetoelectric antennas for portable underwater communication: theory and experiment. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 71, 2167–2181 (2023).

Gao, X. Y. et al. Giant piezoelectric coefficients in relaxor piezoelectric ceramic PNN-PZT for vibration energy harvesting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 8 (2018).

Chu, Z. Q., PourhosseiniAsl, M. & Dong, S. X. Review of multi-layered magnetoelectric composite materials and devices applications. J. Phys. D.-Appl. Phys. 51, 21 (2018).

Dong, S. X., Li, J. F. & Viehland, D. Longitudinal and transverse magnetoelectric voltage coefficients of magnetostrictive/piezoelectric laminate composite: Theory. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq Control 50, 1253–1261 (2003).

Fu, S. et al. Bias-free very low frequency magnetoelectric antenna. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2021YFB3201800), the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 62131017, U22A2019), the Key R&D Project of Shaanxi Province-University Joint Project (2023GXLH-020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dan Xian conceived of the presented idea and writing. Yannan Zhao and Jingen Wu contributed to the reviewing and editing process. Yongjun Du worked on developing the simulation model and writing the “3.4.1 Magnetic-Mechanical-Electrical Coupling Model”. Yiwei Xu and Jiacheng Qiao were responsible for software development and validation. Ming Liu, Qijing Ling, and Zhuangde Jiang provided supervision and funding support.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Zhuangde Jiang is an Editor for the journal, no other author has reported any competing interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xian, D., Zhao, Y., Du, Y. et al. Highly magneto-electric-mechanical coupling effect in self-biased magnetoelectric composite induced by laser thermal annealing. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00875-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00875-w

This article is cited by

-

Magnetostrictive mechanical frequency combs

Nature Communications (2025)